ABSTRACT

Aim

The purpose of the study is to examine the effectiveness of educational training programs on healthcare professionals' confidence in dealing with workplace violence.

Background

Workplace violence is a global problem with serious consequences in healthcare. While training enhances knowledge, skills, and confidence, the critical factor for translating learning into practice, remains underexplored.

Methods

A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Data were retrieved from four databases searched through September 2024.

Results

Ten studies met the inclusion criteria, and two meta‐analyses were conducted. With the control group design, a pooled analysis indicated a significant improvement in healthcare professionals’ confidence following workplace violence training. With a one‐group pre‐ and post‐design, a significant improvement was also found. Although subgroup analysis based on different confidence measurement tools was conducted, heterogeneity was not substantially reduced.

Discussion

Workplace violence training programs improve confidence, yet the evidence is constrained by heterogeneity and limited randomized trials. Confidence‐building strategies such as simulation and repeated practice may be more effective than lectures, though standardized measures and program designs are needed to strengthen comparability and guide best practices.

Conclusion

Workplace violence prevention training appears effective in enhancing healthcare professionals’ confidence. Future studies should establish optimal models, frequency, and validated instruments to ensure sustainable outcomes.

Implications for Nursing and Nursing Policy

According to the WHO Global Strategic Directions, workplace violence prevention training should be integrated into nursing education and practice. Simulation and team‐based methods enhance confidence more effectively than lectures. Institutions must adopt standardized protocols, refreshers, and debriefings, while nursing leaders and professional bodies establish unified standards. Building confidence is central to care quality and system sustainability.

Keywords: confidence, educational training programs, healthcare professional, meta‐analysis, systematic review, workplace violence

1. Introduction

Workplace violence (WPV) against healthcare professionals, defined by the WHO (2021a) as incidents in which an employee is subjected to, threatened, or assaulted in the workplace, is a long‐standing and prevalent problem. A meta‐analysis by Liu et al. (2019) estimated the global 12‐month prevalence of WPV among healthcare workers at 61.9% (95% CI: 56.1%–67.6%). While the reported rates of events were highest in emergency departments and inpatient hospital settings, the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023) reported that healthcare and social service workers experienced 9.8 incidents of intentional injury per 10,000 full‐time workers, compared with 2.1 incidents across all industries. Moreover, up to 88% of WPV incidents in hospital settings may go unreported, suggesting that the true prevalence is substantially higher (Arnetz et al. 2015). There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that exposure to WPV results in physical and psychological sequelae, compromises healthcare professionals’ safety and well‐being and may contribute to post‐traumatic stress disorder and burnout (Benning et al. 2024; Davids et al. 2021; Munn et al. 2024). Psychological and physical effects of WPV negatively affect nurses’ lifestyle, work, and self‐confidence (Bildik et al. 2022; Lu et al. 2020). Reported symptoms include headache, insomnia, general weakness, helplessness, fear, anger, and depression. These consequences can directly or indirectly contribute to the resignation of valuable healthcare professionals (Baby et al. 2019; David et al. 2021).

According to the World Health Organization (2021b), the Global Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery (SDNM) 2021–2025 update the 2016–2020 framework, emphasize evidence‐based practices, and comprise four policy focus areas: education, jobs, leadership, and service delivery. The fourth strategic focus area, service delivery, underscores the importance of safe and supportive service environments. To achieve such an environment, workplaces should guarantee decent working conditions, enforce zero‐tolerance policies, and ensure adequate protection, training, and resources during public health emergencies or incidents of violence (World Health Organization 2021b).

The paucity of evidence surrounding the contributors to WPV is a barrier to creating educational training programs intended to reduce the incidence. While Geoffrion et al. (2020) reported, in a systematic review, that education and training programs enhance personal knowledge and attitudes, they did not address the role of confidence in managing WPV. Confidence, reflecting both practical and psychological dimensions, is often underexplored in the literature on healthcare professionals’ safety (Liao et al. 2025). Kynoch et al. (2024) reviewed the educational interventions for WPV prevention and found current programs primarily focus on enhancing knowledge and skills, such as theories of aggression (n = 18), communication (n = 16), risk assessment (n = 15), de‐escalation strategies (n = 15), and post‐incident management (n = 10). However, there has been limited attention to healthcare professionals’ confidence in handling WPV events.

Confidence enables learners to better calibrate their understanding, seek help when needed, and maximize the effectiveness of an educational intervention. The incorporation of confidence into healthcare professionals’ education helps ensure that the educational content is translated into practice (Morony et al. 2013). Confidence is regarded as one of the most powerful behavioral motivators in daily life. In clinical settings, particularly in critical care or emergency response situations, confidence plays a pivotal role in enabling healthcare professionals to respond promptly, accurately, and safely (Güllü and Kanadli 2025; Oludare and Kotronoulas 2022). A study by Sharour et al. (2022) during the COVID‐19 pandemic reported a positive correlation between confidence and the quality of nurse–patient interactions (r = 0.81, p < 0.0001). Therefore, although knowledge, skills, and attitudes are fundamental components of WPV prevention training, integrating confidence as a core construct in the design and implementation of educational programs is equally critical for enhancing action readiness in challenging clinical environments.

Previous studies have found improved confidence in dealing with violence following violence prevention training programs (Emmerling et al. 2024; Tölli et al. 2017). While the literature has discussed the importance of training healthcare professionals to manage WPV, there is a lack of in‐depth exploration of how confidence influences their ability to effectively handle violent situations (Geoffrion et al. 2020; Kynoch et al. 2024). Therefore, a systematic review was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of educational training programs in improving healthcare professionals’ confidence in dealing with WPV among healthcare professionals.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

A systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. 2021) and registered on PROSPERO (CRD42251083585).

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted in four databases: PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), covering all records from their inception to September 2024, with no language restrictions. A hand search of reference lists from included articles was also completed. Two independent reviewers (YC and YC) screened the titles and abstracts of articles to assess eligibility for inclusion in the review, with a third reviewer (MT) consulted in cases of disagreement. The same two reviewers (YC and YC) conducted full‐text screening, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with the third reviewer. Keywords included “healthcare professional,” “training program,” “education program,” “intervention,” “workplace violence,” “aggression*,” and “confidence.” Search strategies were developed using a combination of free‐text terms, a controlled vocabulary, and keyword synonyms, including Medical Subject Headings (Mesh), Embase subject headings (Emtree), and CINAHL subject headings, applied via Boolean operators. Gray literature and the reference lists of included articles were also searched. (See Figure 1 and Supporting Information Table S3 for details.)

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included articles were conducted in a healthcare setting if the confidence of healthcare professionals evaluated an intervention related to WPV. WPV was defined as verbal or physical violence or aggression from patients or families directed at healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals were defined as doctors, physician assistants, nurses, midwives, or allied health professionals.

2.4. Quality Appraisal

Study quality was appraised using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi‐Experimental Studies15 and Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Two reviewers (YC and YC) appraised article quality independently, with disagreements resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (MT).

2.5. Data Extraction

Two reviewers (YC and YC) extracted study information independently using a standardized data extraction form, and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (MT). Information included author, year of publication, country, setting, participant characteristics, sample size, research design, intervention (program name, structure, content, and timing), comparison, measurement, follow‐up period, and outcome (confidence) (Supporting Information Table 1).

2.6. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Heterogeneity across studies was evaluated using Cochran's χ2 test (Cochran's Q), Tau2 (τ2) values, and I2 values. Standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI were calculated as the difference using the pooled standard deviation (SD) for continuous outcomes. For studies with a single‐group pretest–posttest design, effect sizes were converted to Cohen's d to represent the SMD before and after the intervention. All conversions and analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4) using the metafor and dmetar packages. The random‐effects model used RevMan5 software to evaluate the effect of preventative education training programs in dealing with WPV. The contents of the intervention program were summarized. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on the confidence measurement instruments.

3. Results

The initial search identified 175 articles for screening. After removing ten duplicates, 165 articles remained for title and abstract screening. Title and abstract screening resulted in the assessment of 42 full‐text papers. A review of reference lists identified ten additional studies for further assessment. Finally, ten studies met the eligibility criteria for synthesis (Figure 1).

3.1. Study Characteristics

Ten studies were published from 2007 to 2023. Sample sizes across the included studies ranged from 9 to 392, with a total of 1210 participants. Three studies were conducted in Australia (Adams et al. 2017; Middleby‐Clements and Grenyer 2007; Young et al. 2022) and two each in Pakistan (Baig et al. 2018; Khan et al. 2021), Taiwan (Chang et al. 2022; Ming et al. 2019), and the United States (Armstrong 2017; Jones et al. 2023). One study was conducted in Egypt (Hamza and Abd Elrahman 2020). One study utilized a quasi‐experimental (pre–post), mixed‐methods design (Khan et al. 2021). Six of nine studies used a one‐group, pre–post design (Adams et al. 2017; Armstrong 2017; Hamza and Abd Elrahman 2020; Jones et al. 2023; Middleby‐Clements &Grenyer 2007; Young et al. 2022), and three studies used an interventional design (nonequivalent control group design) (Baig et al. 2018; Chang et al. 2022; Ming et al. 2019).

Five studies used the Confidence in Coping with Patient Aggression Instrument (CCPA) (Baig et al. 2018; Jones et al. 2023; Khan et al. 2021; Middleby‐Clements &Grenyer 2007; Ming et al. 2019). One study used a self‐efficacy scale, and four studies applied investigator‐developed scales (Adams et al. 2017; Armstrong 2017; Chang et al. 2022; Hamza and Abd Elrahman 2020; Young et al. 2022). Nine studies provided evidence that healthcare professionals’ confidence following the preventative educational training program improved (Armstrong 2017; Baig et al. 2018; Chang et al. 2022; Hamza and Abd Elrahman 2020; Khan et al. 2021; Middleby‐Clements and Grenyer 2007; Ming et al. 2019; Jones et al. 2023; Young et al. 2022); however, one study reported no change in confidence (Adams et al. 2017) (Supporting Information Table 1).

3.2. Risk of Bias

One study was appraised with the MMAT (Khan et al. 2021) with a moderate risk of bias. Nine studies were evaluated using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool (Tufunaru et al., 2024) with scores ranging from 6 to 9, low to moderate risk bias (Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2).

3.3. Intervention Programs

Synthesis of the ten studies identified various education training programs aimed at enhancing healthcare professionals’ confidence in managing WPV. Participants included a wide range of healthcare workers, such as nurses, doctors, paramedics, support staff, such as psychiatry, allied health, and security, administration, medical students, and nursing assistants. Each program adopted a multifaceted approach, incorporating elements such as risk assessment, planning, communication techniques, and de‐escalation strategies. Instructional methods varied and included lectures (n = 2), video‐based learning (n = 2), and experiential components (n = 9), such as group role‐plays and scenario‐based exercises (n = 7) focusing on communication and de‐escalation skills. Training durations ranged from 30 to 130 minutes per session, delivered as either single‐session workshops (n = 4) or multi‐session programs (n = 6), with frequencies spanning daily sessions over 35 days, two‐day intensives, weekly formats, and periodic training every three to six months. Most studies highlighted the importance of repeated practice to reinforce learning and skill retention.

Although the training content and delivery methods varied, three strategies were identified across the range of interventions: awareness and risk assessment (Adams et al. 2017; Armstrong 2017; Baig et al. 2018; Chang et al. 2022; Hamza and Abd Elrahman 2020; Jones et al. 2023; Ming et al. 2019; Young et al. 2022), communication and de‐escalation (Baig et al. 2018; Chang et al. 2022; Hamza and Abd Elrahman 2020; Jones et al. 2023; Khan et al. 2021; Young et al. 2022), and post‐incident management with institutional policy development (Adams et al. 2017; Middleby‐Clements and Grenyer 2007; Young et al. 2022). The first component focused on the early identification of behavioral cues, environmental triggers, and the motivations behind aggressive behavior. The second centered on strengthening verbal and nonverbal de‐escalation skills through interactive and scenario‐based methods. The third involved post‐incident strategies, including structured debriefings and the implementation of institutional protocols such as zero‐tolerance policies and emergency response procedures such as “Code Black.”

Confidence‐building was a foundational element integrated throughout all components of the programs. Interventions that embedded repeated practice, team‐based feedback, and realistic simulations were found to be more effective in enhancing participants’ psychological readiness and perceived competence. The systematic review indicates that confidence‐enhancing strategies should be intentionally incorporated, prior to or alongside communication and de‐escalation training, to strengthen healthcare professionals’ engagement, motivation, and real‐world application of acquired skills.

3.4. Meta‐Analysis of Confidence

Two meta‐analyses were conducted with or without a control group. Four studies that adopted a nonequivalent control group design were incorporated into the primary meta‐analysis. Six studies employed a single‐group pretest–posttest design. While these lacked control groups, they were synthesized using the method proposed by Baldwin et al. (2023), with effect sizes converted to Cohen's d and analyzed using a random‐effects model.

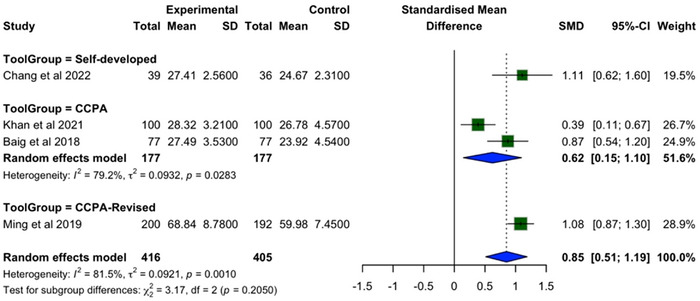

The meta‐analysis conducted using data from four studies that included control groups (Chang et al. 2022; Baig et al. 2018; Khan et al. 2021; Ming et al. 2019) provided the requisite data with a sample size of 821 healthcare professionals ranging in age from 27 to 34 years. The results showed that implementing a WPV preventative education program significantly increased participants’ confidence (SMD = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.51–1.19). However, considerable heterogeneity was noted (Cochran's Q = 16.21, p = 0.001, I2 = 81.5%, Tau2 = 0.092) (Figure 2). To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, a subgroup analysis was performed based on the type of confidence measurement instrument used, including an investigator‐developed scale. The analysis showed that studies using the CCPA scale exhibited substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 79.2%, SMD = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.15–1.10, τ2 = 0.0932, p = 0.0283). The overall test for subgroup differences was not significant (χ2 = 3.17, p = 0.2050) (Figure 4) (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Confidence in control group design.

FIGURE 4.

Confidence in control groups design subgroup by instrument.

TABLE 1.

Data extraction.

| First author (publication year), country | Study design | Setting | Sample size and characteristics | Comparison group | Intervention | Instrument | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Middleby‐Clements and Grenyer 2007 Australia |

Quasi‐experimental study (one group, pre–post study) |

NSW Health Service |

|

Yes |

|

|

Confidence: Pre vs. Post: 62.62 vs. 69.89, df = 1, F = 16.48, p = 0.00 |

|

Adams et al. 2017 Australia |

Quasi‐experimental study (one group, pre–post study) |

Two medical wards |

|

Yes |

|

|

Confidence: F (1, 55): 0.239 p: 0.627 (95% CI: −0.073‐0.119) |

|

Armstrong 2017 United States |

Quasi‐experimental study (one group, pre–post study) |

Medical–surgical unit |

|

N/A |

|

|

Confidence: Item 1: Means ± SD: −14.444 ± 15.09 t = −2.871; p = 0.021 Item 2: Means ± SD: −0.23.333 ± 15.00 t = −4.667; p = 0.002 Item 3: Means ± SD: −0.24.44 ± 16.667 t = −4.400; p = 0.002 Overall: ΔMean: 20.41 Pooled SD (total): 19.08 |

|

Baig et al. 2018 Pakistan |

Quasi‐experimental study (intervention study) |

Emergency, gynecology and obstetrics, medicine and allied and surgery |

|

Yes |

|

|

Confidence: (Means ± SD: 27.49 ± 3.53) as compared with control (means ± SD: 23.92 ± 4.52) p < 0.001 |

|

Ming et al. 2019 Taiwan |

Quasi‐experimental study (intervention study) |

|

|

Yes |

|

|

Self‐confidence: p < 0.001 (Means ± SD: 59.78 ± 8.06) as compared with control (means ± SD: 68.84 ± 8.78) After GEE analysis (B = 8.054, Wald χ2 = 115.520, p < 0.001) |

|

Hamza and Abd Elrahman 2020 Egypt |

Quasi‐experimental study (one group, pre–post study) |

Psychiatric wards |

|

N/A |

|

|

Confidence Item 1: Means ± SD: 1.4 ± 1.5t = 6.24** Item 2: Means ± SD: 0.3 ± 1.4 t = 1.26 Item 3: Means ± SD: 1.5 ± 1.4 t = 7.26** Item 4: Means ± SD: 1.1 ± 1.5 t = 4.93** Item 5: Means ± SD: 1.2 ± 1.5 t = 5.42** Item 6: Means ± SD: 0.8 ± 1.0 5.36** Item 7: Means ± SD: 0.3 ± 1.6 1.37 **p < 0.0001 Overall: ΔMean: 0.943 Pooled SD (total): 1.427 |

|

Khan et al. 2021 Pakistan |

Mixed‐method design (intervention study) |

Emergency department of two tertiary care hospitals |

|

Yes |

|

|

Confidence: p = 0.006 (Means ± SD: 28.32 ± 3.21) as compared with control (Means ± SD: 26.78 ± 4.57) |

|

Young et al. 2022 Australia |

Quasi‐experimental study (one group, pre–post study) |

Psychiatric wards |

|

N/A |

|

|

Confidence: Two domains:

Overall: ΔMean: 16.125 pooled SD (total): 22.951 |

|

Chang et al. 2022 Taiwan |

Experimental study (cluster‐randomized assigned, intervention study) |

Emergency department |

|

N/A |

|

||

|

|

Confidence:

|

|||||

|

Jones et al. 2023 United States |

Quasi‐experimental study (one group, pre–post study) |

|

|

N/A |

|

|

Confidence:

Overall: ΔMean: 0.21 pooled SD (total): 0.177 |

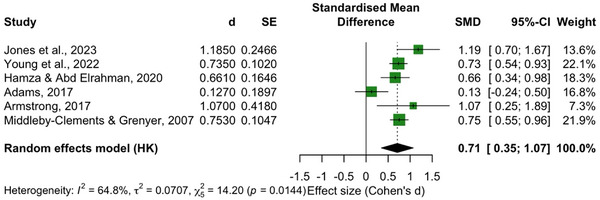

A separate meta‐analysis was conducted for the remaining six studies that used a single‐group, pretest–posttest design (Jones et al. 2023; Young et al. 2022; Hamza and Abd Elrahman 2020; Adams et al. 2017; Armstrong 2017; Middleby‐Clements and Grenyer 2007). The studies provided data from 234 participants, with reported mean ages ranging from 26 to 39 years. Although these studies lacked a control group, they were synthesized using the method proposed by Baldwin et al. (2023), with effect sizes converted to Cohen's d and analyzed using a random‐effects model. The results indicated a significant improvement in participants’ confidence following the intervention (Cohen's d = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.35–1.07), with moderate heterogeneity (Cochran's Q = 14.20, p = 0.0141, I2 = 64.8%, Tau2 = 0.0707) (Figure 3). A subgroup analysis was conducted for the six studies that adopted a single‐group pretest–posttest design, using the type of confidence measurement instrument as the classification criterion. Studies that employed the CCPA scale demonstrated a larger effect size, with moderate heterogeneity that was lower than the overall estimate (Cohen's d = 0.91, I2 = 61.5%, 95% CI = ‐1.73–3.56, τ2 = 0.0574, p = 0.1068). In contrast, studies using investigator‐developed tools reported a smaller effect size, with higher heterogeneity exceeding the overall estimate (Cohen's d = 0.54, I2 = 70%, 95% CI = −0.56–1.64, τ2 = 0.1246, p = 0.0357). Although the test for subgroup differences did not reach significance (χ2 = 1.30, p = 0.52) (Figure 5), these findings suggest that variation in measurement tools may be one of the potential contributors to differences in effect size estimates and study heterogeneity.

FIGURE 3.

Confidence in single‐group pretest–posttest design.

FIGURE 5.

Confidence in single‐group pretest–posttest design subgroup by instrument.

4. Discussion

A review of ten studies published between 2007 and 2023 examined the ability of WPV prevention training for healthcare professionals across various countries and professional roles to impact confidence. The study designs comprised four quasi‐experiments with control groups and six single‐group pretest–posttest designs, using six different instruments to assess confidence. Notably, only five studies used the CCPA scale, which has demonstrated good validity and reliability in evaluating healthcare professionals’ confidence (Thackrey 1987). Overall, nine studies reported improvements in confidence following the intervention. These findings align with earlier work by Tölli et al. (2017), which showed that training interventions were more effective in enhancing confidence than in improving knowledge or attitudes. Consistent with Liao et al. (2025), our results also suggest that simulation‐based and repeated training may further strengthen confidence and psychological resilience in high‐risk situations. Confidence is considered a broad and consciously accessible belief system and has been identified as the strongest predictor of achievement outcomes (Morony et al. 2013). Confidence may improve the ability of healthcare professionals to speak out and intervene appropriately when faced with WPV (Fathy Abd Elmoteleb Ali Hamza and Abd Elhamed Abd Elrahman 2020). Taken together, the evidence highlights the practical effectiveness of confidence‐building strategies embedded within WPV prevention programs. The results indicated that, compared with improving attitudes or knowledge, training significantly enhanced nurses’ confidence.

The quality of the studies was good, though only four studies included control groups. The lack of randomized control trials reduces the strength of the body of evidence. The curriculum and content of the educational training programs identified in this systematic review demonstrated marked heterogeneity in the confidence measurement instrument, intervention content, frequency, and duration. Some studies used validated instruments (e.g., CCPA), while others relied on researcher‐developed measures with limited psychometric information. This variation in measurement tools may have reduced the comparability of outcomes across studies and contributed to heterogeneity. The various interventions likely contributed to heterogeneity, making any recommendation difficult. The persistence of moderate to high heterogeneity indicates that additional factors contribute to the observed variation across studies. Factors may include differences in intervention content, training frequency and duration, instructional approaches, curriculum structure, and sample characteristics. Future research should prioritize the use of standardized, psychometrically validated instruments and investigate potential moderating variables to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the sources of heterogeneity in intervention effectiveness.

Therefore, although knowledge, skills, and attitudes are fundamental components of WPV prevention training, incorporating “confidence” as a core construct in the design and implementation of educational programs is equally critical to enhancing action readiness in challenging clinical environments.

4.1. Implications for Nursing and Nursing Policy

According to the World Health Organization (2021b), the SDNM 2026–2030 outline four key pillars—education, employment, leadership, and service delivery—that can guide nursing policy responses. Based on the findings of this systematic review and meta‐analysis, we propose the following recommendations for stakeholders. “Education,” WPV prevention should be integrated across the entire nursing continuum. Simulation‐based training, scenario‐based learning, and team drills are more effective than traditional didactic approaches in fostering confidence and real‐time response. Regarding workforce considerations, or “jobs,” institutions must implement standardized WPV training protocols that are tailored to clinical realities. Modular formats, regular refreshers, and post‐incident debriefings can strengthen psychological readiness, while embedding these practices into hospital accreditation processes helps ensure sustainability and institutional accountability. “Leadership and service delivery” also play pivotal roles. Nursing leaders must prioritize WPV prevention within organizational policy and culture by advocating for resources, staff empowerment, and ongoing institutional support. Simultaneously, national nursing associations and regulatory bodies should collaborate to establish unified training standards that define core content, recommend validated confidence measures, and offer benchmarks for evaluating effectiveness. These strategies reflect the WHO framework and provide a comprehensive policy road map. Ultimately, our review highlights that building confidence is critical to service delivery in WPV contexts. At the same time, embedding WPV prevention training into broader strategies across education, employment, and leadership may further strengthen the sustainability and system‐level impact of such programs, though this requires confirmation in future research.

4.2. Limitations

A comprehensive search included quasi‐experimental designs with methodological quality. However, limitations include the lack of control groups in many studies, limiting the strength of the evidence. Study heterogeneity reduced the precision and statistical power of the meta‐analysis. Although subgroup analyses were conducted to enhance the robustness of the findings, the results must be interpreted with caution. Considerable variation in the content of the preventative education programs limited the interpretability and comparability of the findings. Moreover, due to the small number of studies with the same design, it was not possible to formally assess publication bias, which further constitutes a limitation of this review. High‐quality controlled trials are recommended to validate these results.

5. Conclusion

WPV preventive education training programs can increase healthcare professionals' confidence in managing patient behaviors in healthcare workplace settings. Although the effectiveness of these programs varies across different study designs and definitive conclusions remain limited, the findings contribute to consolidating existing evidence and strengthening the empirical foundation for the role of such programs in supporting professional competence. While an increase in confidence does not directly indicate an improvement in performance or ability, confidence may reflect a heightened sense of preparedness and willingness to respond to violent incidents. Establishing a standardized training protocol that incorporates core components and integrating it into hospital‐level education planning may help ensure a consistent level of readiness among healthcare professionals in the face of WPV. Although some studies suggest that training should be provided every 3 to 6 months to reinforce and sustain acquired knowledge and skills, the optimal frequency and timing of training sessions require further investigation. Future research is needed to explore the most effective implementation models for educational training programs to affect worker confidence in fostering a safe, supportive, and empowering work environment.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Yi‐Fei Chung and Susan Jane Fetzer. Data collection, data analys and interpretation: Yi‐Fei Chung, Yu‐Chun Chang, and Meng‐Hsuan Tsai. Drafting of the article: Yi‐Fei Chung. Critical revision of the article: Yu‐Chun Chang, Susan Jane Fetzer, Lindsay Tessmer, and Jui‐Ying Feng.

6.

Supporting information

Supporting Information File 1: inr70107‐sup‐0001‐tableS1.pdf.

Supporting Information File 2: inr70107‐sup‐0001‐tableS2.pdf.

Supporting Information File 3: inr70107‐sup‐0001‐tableS3.pdf.

Chung, Y.‐F. , Chang Y.‐C., Fetzer S. J., Tessmer L., Tsai M.‐H., and Feng J.‐Y.. 2025. “The Effectiveness of Workplace Violence Prevention Education Training Programs on Healthcare Professionals’ Confidence: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” International Nursing Review 72, no. 4: e70107. 10.1111/inr.70107

Funding: This study was funded by Tungs' Taichung Metrohabor Hospital Grant No. TTMHH‐R1130098.

[Correction added on 22 October 2025, after first online publication: The copyright line was changed.]

Data Availability Statement

Access to the primary data underpinning the study's findings can be facilitated by referring to the search strategy outlined in Supporting Information. Any data that may not be accessible are due to specific constraints or limitations, which will be clearly explained.

References

- Abu Sharour, L. , Bani Salameh A., Suleiman K., et al. 2022. “Nurses' Self‐Efficacy, Confidence and Interaction with Patients with COVID‐19: A Cross‐Sectional Study.” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 16, no. 4: 1393–1397. 10.1017/dmp.2021.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J. , Knowles A., Irons G., Roddy A., and Ashworth J.. 2017. “Assessing the Effectiveness of Clinical Education to Reduce the Frequency and Recurrence of Workplace Violence.” Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 34, no. 3: 6–15. 10.37464/2017.343.1520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, N. E. 2017. “A Quality Improvement Project Measuring the Effect of an Evidence‐Based Civility Training Program on Nursing Workplace Incivility in a Rural Hospital Using Quantitative Methods.” Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care 17, no. 1: 100–137. 10.14574/ojrnhc.v17i1.438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz, J. E. , Hamblin L., Ager J., et al. 2015. “Underreporting of Workplace Violence.” Workplace Health & Safety 63, no. 5: 200–210. 10.1177/2165079915574684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baby, M. , Gale C., and Swain N.. 2019. “A Communication Skills Intervention to Minimise Patient Perpetrated Aggression for Healthcare Support Workers in New Zealand: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial.” Health & Social Care in the Community 27, no. 1: 170–181. 10.1111/hsc.12636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig, L. A. , Tanzil S., Shaikh S., Hashmi I., Khan M. A., and Polkowski M.. 2018. “Effectiveness of Training on De‐Escalation of Violence and Management of Aggressive Behavior Faced by Health Care Providers in a Public Sector Hospital of Karachi.” Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 34, no. 2: 294–299. 10.12669/pjms.342.14432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J. R. , Wang B., Karwatowska L., et al. 2023. “Childhood Maltreatment and Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of Quasi‐Experimental Studies.” The American Journal of Psychiatry 180, no. 2: 117–126. 10.1176/appi.ajp.20220174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning, L. , Teepe G. W., Kleinekort J., et al. 2024. “Workplace Violence Against Healthcare Workers in the Emergency Department: A 10‐year Retrospective Single‐Center Cohort Study.” Scandinavian Journal of Trauma Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 32, no. 1: 88. 10.1186/s13049-024-01250-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bildik, B. , Atis S. E., Cekmen B., and Dorter M.. 2022. “Do We Feel Safe and Confident About Workplace Violence in the Emergency Departments?” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 59: 9–14. 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.‐C. , Hsu M.‐C., and Ouyang W.‐C.. 2022. “Effects of Integrated Workplace Violence Management Intervention on Occupational Coping Self‐Efficacy, Goal Commitment, Attitudes, and Confidence in Emergency Department Nurses: A Cluster‐Randomized Controlled Trial.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2835. 10.3390/ijerph19052835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davids, J. , Murphy M., Moore N., Wand T., and Brown M.. 2021. “Exploring Staff Experiences: A Case for Redesigning the Response to Aggression and Violence in the Emergency Department.” International Emergency Nursing 57: 101017. 10.1016/j.ienj.2021.101017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerling, S. A. , McGarvey J. S., and Burdette K. S.. 2024. “Evaluating a Workplace Violence Management Program and Nurses' Confidence in Coping with Patient Aggression.” JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration 54, no. 3: 160–166. 10.1097/nna.0000000000001402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathy Abd Elmoteleb Ali Hamza, M. , and Abd Elhamed Abd Elrahman A.. 2020. “Impact of Workplace Violence Educational Program on Self‐Confidence for Nursing Staff Working in Psychiatric Hospital.” Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development 11, no. 1: 1097. 10.37506/v11/i1/2020/ijphrd/193985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffrion, S. , Hills D. J., Ross H. M., et al. 2020. “Education and Training for Preventing and Minimizing Workplace Aggression Directed Toward Healthcare Workers.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9, no. 9: CD011860. 10.1002/14651858.cd011860.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güllü, A. , and Kanadli K. A.. 2025. “The Correlation Between Attitudes towards Health Technologies and Professional Self‐Efficacy in Intensive Care Nurses: A Cross‐Sectional Study.” International Nursing Review 72, no. 3: Articlee70066. 10.1111/inr.70066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, M. F. A. E. A. , and Abd Elrahman A. A. E.. 2020. “Impact of Workplace Violence Educational Program on Self‐Confidence for Nursing Staff Working in Psychiatric Hospital.” Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development 11, no. 1: 1097–1101. 10.37506/v11/i1/2020/ijphrd/193985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N. , Decker V. B., and Houston A.. 2023. “De‐Escalation Training for Managing Patient Aggression in High‐Incidence Care Areas.” Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 61, no. 8: 1–8. 10.3928/02793695-20230221-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. N. , Khan I., Ul‐Haq Z., et al. 2021. “Managing Violence Against Healthcare Personnel in the Emergency Settings of Pakistan: A Mixed Methods Study.” BMJ Open 11, no. 6: e044213. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kynoch, K. , Liu X. L., Cabilan C. J., and Ramis M. A.. 2024. “Educational Programs and Interventions for Health Care Staff to Prevent and Manage Aggressive Behaviors in Acute Hospitals: A Systematic Review.” JBI Evidence Synthesis 22, no. 4: 560–606. 10.11124/JBIES-22-00409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L. , Guo N., Han Q., Qian Y., Xi H., and Wang L.. 2025. “Long‐Term Effect of a Comprehensive Active Resilience Education (CARE) Program for Increasing Resilience in Emergency Nurses Exposed to Workplace Violence: A Secondary Analysis of a 12‐Week Follow‐up Study.” International Nursing Review 72, no. 2: e70037. 10.1111/inr.70037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Gan Y., Jiang H., et al. 2019. “Prevalence of Workplace Violence Against Healthcare Workers: a Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 76, no. 12: 927–937. 10.1136/oemed-2019-105849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L. , Dong M., Wang S. B., et al. 2020. “Prevalence of Workplace Violence against Health‐Care Professionals in China: A Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis of Observational Surveys.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 21, no. 3: 498–509. 10.1177/1524838018774429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallette, C. , Duff M., McPhee C., Pollex H., and Wood A.. 2011. “Workbooks to Virtual Worlds: A Pilot Study Comparing Educational Tools to Foster a Culture of Safety and Respect in Ontario.” Nursing leadership (Toronto, Ont.) 24, no. 4: 44–64. 10.12927/cjnl.2012.22714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleby‐Clements, J. L. , and Grenyer B. F. S.. 2007. “Zero Tolerance Approach to Aggression and Its Impact Upon Mental Health Staff Attitudes.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 41, no. 2: 187–191. 10.1080/00048670601109972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming, J. L. , Tseng L. H., Huang H. M., Hong S. P., Chang C. I., and Tung C. Y.. 2019. “Clinical Simulation Teaching Program to Promote the Effectiveness of Nurses in Coping with Workplace Violence.” Hu Li Za Zhi The Journal of Nursing 66, no. 3: 59–71. 10.6224/JN.201906_66(3).08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morony, S. , Kleitman S., Lee Y. P., and Stankov L.. 2013. “Predicting Achievement: Confidence vs Self‐efficacy, Anxiety, and Self‐concept in Confucian and European Countries.” International Journal of Educational Research 58: 79–96. 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munn, L. T. , O'Connell N., Huffman C., et al. 2024. “Job‐Related Factors Associated With Burnout and Work Engagement in Emergency Nurses: Evidence to Inform Systems‐Focused Interventions.” Journal of Emergency Nursing 51, no. 2: 249–260. 10.1016/j.jen.2024.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oludare, T. R. , and Kotronoulas G.. 2022. “Determinants and Consequences of Workplace Violence Against Hospital‐Based Nurses: A Rapid Review and Synthesis of International Evidence.” Nursing Management 29, no. 6: 18–25. 10.7748/nm.2022.e2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., et al. 2021. “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews.” British Medical Journal 372, no. 71: n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thackrey, M. 1987. “Clinician Confidence in Coping With Patient Aggression: Assessment and Enhancement.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 18, no. 1: 57–60. 10.1037//0735-7028.18.1.57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tölli, S. , Partanen P., Kontio R., and Häggman‐Laitila A.. 2017. “A Quantitative Systematic Review of the Effects of Training Interventions on Enhancing the Competence of Nursing Staff in Managing Challenging Patient Behaviour.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 73, no. 12: 2817–2831. 10.1111/jan.13351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufunaru, C. , Munn Z., Aromataris E., Campbell J., and Hopp L.. 2024. “ Systematic Reviews of Effectiveness .” JBI EBooks. 10.46658/jbimes-24-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2023. Table 1. Incidence Rates of Nonfatal Occupational Injuries and Illnesses by Industry and Case Types, 2021. Www.bls.gov. https://www.bls.gov/web/osh/table‐1‐industry‐rates‐national.htm#soii_n17_as_t1.f.1. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2021a. Preventing Violence Against Health Workers. http://www.who.int/activities/preventing‐violence‐against‐health‐workers. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2021b. Global Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery 2021–2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033863. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J. , Fawcett K., and Gillman L.. 2022. “Evaluation of an Immersive Simulation Programme for Mental Health Clinicians to Address Aggression, Violence, and Clinical Deterioration.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 31, no. 6: 1417–1426. 10.1111/inm.13040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information File 1: inr70107‐sup‐0001‐tableS1.pdf.

Supporting Information File 2: inr70107‐sup‐0001‐tableS2.pdf.

Supporting Information File 3: inr70107‐sup‐0001‐tableS3.pdf.

Data Availability Statement

Access to the primary data underpinning the study's findings can be facilitated by referring to the search strategy outlined in Supporting Information. Any data that may not be accessible are due to specific constraints or limitations, which will be clearly explained.