Abstract

Introduction:

The interaction of amyloid and tau in neurodegenerative diseases is a central feature of AD pathophysiology. While experimental studies point to various interaction mechanisms, their causal direction and mode (local, remote or network-mediated) remain unknown in human subjects. The aim of this study was to compare mathematical reaction-diffusion models encoding distinct cross-species couplings to identify which interactions were key to model success.

Methods:

We tested competing mathematical models of network spread, aggregation, and amyloid-tau interactions on publicly available data from ADNI.

Results:

Although network spread models captured the spatiotemporal evolution of tau and amyloid in human subjects, the model including a one-way amyloid-to-tau aggregation interaction performed best.

Discussion:

This mathematical exposition of the “pas de deux” of co-evolving proteins provides quantitative, whole-brain support to the concept of amyloid-facilitated-tauopathy rather than the classic amyloid-cascade or pure-tau hypotheses, and helps explain certain known but poorly understood aspects of AD.

Keywords: Mathematical modeling, Alzheimer’s disease, Tau, Amyloid-beta, Computational, Neuroscience

1. Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) involves widespread and progressive deposition of amyloid beta () protein in cortical plaques and tau tangles (Braak and Braak, 1991; Thal et al., 2002). usually first appears in frontal regions and subsequently spreads to allocortical, diencephalic, brainstem, striatal and basal forebrain regions (Thal et al., 2002; Jagust and Mormino, 2011). In contrast to , tau tangles appear first in the locus coeruleus, then entorhinal cortex, followed by an orderly spread into hippocampus, amygdala, temporal lobe, basal forebrain, and isocortical association areas (Braak and Braak, 1991). The dominant “amyloid cascade hypothesis” (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002), posits that amyloid is the upstream factor, whose early abnormal accumulation in the brain causes a cascade of downstream events that recruit misfolded tau. However, this hypothesis has encountered several difficulties, including the spectacular failure of many large clinical trials of amyloid-targeting therapies, and the fact that the temporal and regional distribution of is quite dissociated from that of tau as well as of downstream atrophy and cognitive deficits (La Joie et al., 2012; Rabinovici et al., 2010; Jack et al., 2010). This has led to the search for other mechanisms, especially the role of tau, which is increasingly considered more central to AD pathophysiology. However, it is unlikely that tau alone can explain AD pathogenesis, due to overwhelming mechanistic, genetic and demographic evidence of amyloid involvement.

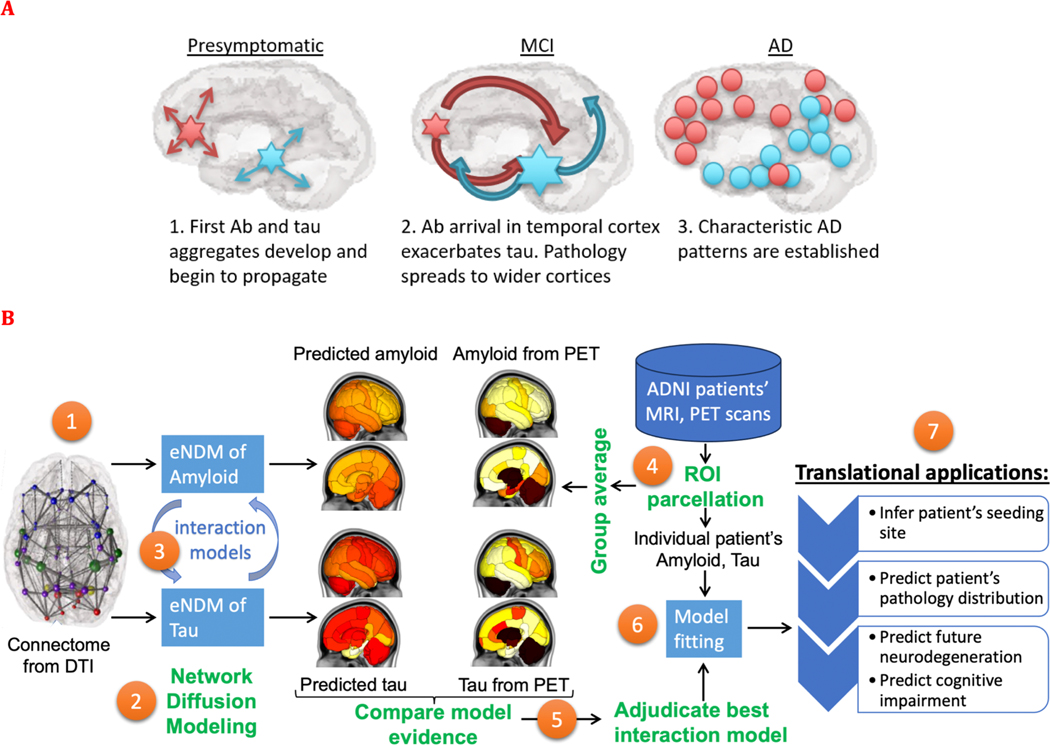

Among potential alternative concepts put forward to reconcile these difficulties, a prominent one is the emerging concept of network-based transmission of both amyloid and tau. Evidence is accumulating in favor of self-assembly and trans-neuronal propagation of amyloid and tau, indeed, of all neurodegenerative pathologies (Jucker and Walker, 2013; Frost and Diamond, 2010; Clavaguera et al., 2009; Iba et al., 2015). Unlike conventional assumptions about spatial spread, this emerging concept implies spread along axonal projections, and the resulting networked spread has repeatedly been substantiated by neuroimaging (Raj et al., 2012a, 2015; Zhou et al., 2012a; Pievani et al., 2011). Network-mediated spread of amyloid and tau offers an attractive means of reconciling above difficulties: the two species may interact locally, but the effects of these interactions do not remain local, and may propagate across neural circuits to distant regions. Given that the two species have unique and different “epicenters” or seeding loci, this would lead to the apparent observation of their deposition in separate non-overlapping regions. This broad hypothesis as schematized in Fig. 1A, posits that the spatiotemporal progression of AD-related amyloid and tau proceeds on the connectivity network after being seeded at different sites. As the progression proceeds, we expect that the two entities will come in contact with each other, interact kinetically by affecting the other species aggregation and spread. Thus, the cross-species interaction, in the background of network-mediated propagation, may present a plausible framework for understanding AD progression.

Fig. 1.

Study goals, design and work flow. A: This study aims to test the broad hypothesis schematized here, such that the spatiotemporal progression of AD-related amyloid and tau proceeds on the connectivity network after being seeded at different sites. As the progression proceeds, we expect that the two entities will come in contact with each other, interact kinetically by affecting the other species aggregation and spread. B: The overall study design to test these processes is illustrated here. Using the structural network connectome (1), we deployed the extended Network Diffusion Model (eNDM) that seeks to recapitulate trans-neuronal spread of amyloid and tau pathology (2). Starting with the base model of independent eNDMs for both amyloid and tau, we successively introduced various models of interaction between the two (3) – these models are listed in Table 1. From the ADNI database we extracted regional distributions of tau and amyloid SUVr from raw PET images (4), whose group average patterns were used to statistically evaluate against each computational model (5). Using model evidence criteria we adjudicated between all possible interaction models and selected the best performing one, yielding a numerical assessment of the most likely mode of interaction between amyloid and tau. This adjudicated model was then fit to individual patients’ regional pathology data using Bayesian inference of model parameters (6). The fitted model was capable of not only predicting the patient’s pathology pattern but also their specific seeding sites – a potential marker of translational interest. The model outcomes may in future translational applications be used to predict future pathology, neurodegeneration and cognitive state of the patient (7).

Many experimental and mechanistic studies are available that point to a complex interaction between amyloid and tau. It is well known that facilitates the aggregation of tau and influences the course and severity of downstream atrophy (Hurtado et al., 2010; Ittner and Götz, 2011; Götz et al., 2001). Mechanistic studies point to various modes of interaction, both direct and indirect (Ittner and Götz, 2011; Walker et al., 2018; Kara et al., 2018; King et al., 2006). Hippocampal injection of AD-derived tau into the brains of transgenic mice expression mutant APP was found to promote tau aggregation in “dystrophic neurites”, which have an core, as well as neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads, suggesting a direct, local interaction (Spires-Jones and Hyman, 2014). These different species were found to accumulate and spread at different rates as function of plaque load (He et al., 2018a). Alternatively, others have proposed that mediates the accumulation and spread of tau by recruiting microglia and inducing a pro-inflammatory immune response (Maphis et al., 2015a; Mancuso et al., 2019; Asai et al., 2015; Perez-Nievas et al., 2013), or by causing hyperexcitability-mediated release of tau (Wu et al., 2016). Tau may also play a role in formation, which may occur in the absence of -mediated tau accumulation (Jackson et al., 2016) or with the two species interacting synergistically (Pooler et al., 2013a).

While these studies provide important mechanistic evidence in model organisms, they may be sensitive to idiosyncratic methodological choices, leading to a diversity of mechanistic possibilities that may not generalize and may not be germane to human disease. Key aspects of brain-wide propagation of tau and amyloid, and the exact mechanistic form of their mutual interactions, therefore remain unsupported empirically in human AD. Since experimental testing of mechanistic hypotheses is difficult in humans, here we took a somewhat unorthodox approach, by relying on a computational rather than experimental interrogation of the mechanistic interaction between tau and amyloid. Our overall study design to test the above processes is illustrated in Fig. 1B.

We first formulated a mathematical model that recapitulates the spatiotemporal evolution of human AD, based on recent advances in the mathematical modeling of reaction-diffusion or network processes that have emerged as a powerful means of evaluating the brain-wide consequences of biophysical mechanisms underlying self-assembly and propagation of neurodegenerative pathologies (Pievani et al., 2011; Raj et al., 2015, 2012b; Zhou et al., 2012b; Weickenmeier et al., 2019; Fornari et al., 2019; Iturria-Medina et al., 2014, 2017). On top of this base network model, we then built various interaction models that allow and tau species to interact in local neural populations. We compared the performance of each interaction model via thorough statistical adjudication, by accumulating model evidence on large neuroimaging (tau and amyloid PET, MRI) datasets of AD spectrum subjects. We devised a fitting procedure to obtain model parameters that best match individual subjects’ regional disease patterns. In this manner we were not only able to determine the most well-supported modes of cross-species interactions, but also their applicable kinetic rates. Although spatial and network spread models of single pathological species have been previously reported (Pievani et al., 2011; Raj et al., 2015, 2012b; Zhou et al., 2012b; Weickenmeier et al., 2019; Fornari et al., 2019; Iturria-Medina et al., 2014, 2017), and data-driven models of multiple biomarkers are also available (Iturria-Medina et al., 2017; Young et al., 2014; Oxtoby et al., 2017), this study is unique in modeling and evaluating directly on empirical data the network-mediated transmission and interaction of tau and amyloid jointly.

We show that both network propagation and amyloid-tau interaction are necessary to recapitulate human AD data. Our data conclusively support that network-mediated spread with a 1-way interaction, whereby amyloid facilitates local tau aggregation, is the most parsimonious and accurate model, yielding correlations above 0.7 against empirical tau topography. We also tested other interactions, including bidirectional ones and those involving enhanced pathology spread instead of aggregation, but these were not well supported on statistical tests. In totality, this “toxic pas de deux” (Ittner and Götz, 2011) of co-evolving tau and amyloid pathologies provides critical numerical support to mechanistic hypotheses not possible to be tested directly in humans. We anticipate that our computational testbed will become an important future tool for the generation and testing of mechanistic hypotheses with the potential to complement studies in model organisms.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental design

Subjects and data.

Data used in this study were obtained from the ADNI (Weiner et al., 2012) database; consisting of 531 ADNI-3 subjects who had at least one exam of all three: MRI, AV1451-PET and AV45-PET, available by 1/1/2021. Demographic information is in Table S1. These data were processed to obtain regional of pathology and atrophy, the latter used in this analysis as a measure of tau-induced neurodegeneration. Anatomic connectomes were computed from healthy diffusion MRI and tractography algorithms. The primary dataset was evaluated on the 86-region Desikan atlas and the Supplementary dataset on 90-region AAL atlas, using similar processing pipelines; see SI: Note 2. To remove AV1451-PET scans’ non-specific binding and the effect of iron in thalamus and striatum, their values were removed from subsequent analysis, leaving 76 regions. Proposed network models were applied to canonical healthy connectomes from human connectome project (HCP) (Glasser et al., 2013) and model patterns compared against the ADNI regional data.

2.2. Network spread model with cross species interactions

Refer to SI: Note 1 for detailed model description. Here we summarize the overall amyloid-tau coupled system:

The first term on the right represents network diffusion, following our prior work (Raj et al., 2012a), whereby pathology spread follows regional concentration gradients restricted along network connections. This involves the connectome’s Laplacian matrix H and the diffusivity rate constant . This model captures trans-neuronal propagation as a connectivity-based process. The second term specifies how pathologic tau and amyloid respectively are initially seeded and produced during the course of progression (Figures S1 and S2). The last term encodes the interaction between the two species, and is the object of specific interest in this study. Accordingly, from the broad system above we have derived several network-interaction models of increasing complexity (Eqns 1–8 in SI) and carefully tested them against each other.

2.3. Statistical analysis and model testing

Both group statistics (t-statistics for each of EMCI, LMCI and AD groups) and individual fitting was performed. Empirical regional AV1451-PET tau was supplemented with MRI-derived regional atrophy to leverage larger sample size; since atrophy is a useful surrogate for tau, with strong regional association (Whitwell et al., 2008). The statistical test of choice is Pearson correlation strength, R, and its two-tailed p. Detailed model fitting to individual subjects is described in SI: Note 6. We used a Bonferroni correction to account for potential false positives. We also performed extensive permutation tests with 500 random permutations and compiled additional measures of significance. We used Fisher’s R-to-z transformation to assess significance between models of comparable complexity, and AIC for models with varying complexity.

Data and code Availability.

Patient data can be directly obtained from the ADNI study (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). To facilitate review, group data herein will be made available publicly and without limitations, along with the entire code repository, at our laboratory’s GitHub site: https://github.com/Raj-Lab-UCSF/Aggregation-Network-Diffusion. There are no restrictions or embargoes, subject to standard BSD3 license.

3. Results

I. Aggregate relationships between tau, amyloid, atrophy and the network

The public ADNI3 data (Weiner et al., 2012) was processed with established software pipelines to obtain regional imaging biomarkers of atrophy, tau and amyloid (demographics in Table S1). First, we ascertained how individual subjects’ biomarker triplets are related to each other at the aggregate level. We find a moderate yet significant (p < 10−3, post-Bonferroni correction) relationship between atrophy and tau, but not between atrophy and amyloid (Fig. 2A). There is a strong relationship between tau and amyloid, providing an empirical justification for modeling local amyloid-tau interactions (Hurtado et al., 2010; Ittner and Götz, 2011; Götz et al., 2001). Accompanying histograms of correlation strengths of disease groups (EMCI, LMCI, AD) demonstrate a prominent stage dependence, whereby atrophy is more tightly related to tau in later rather than earlier stages. The situation is reversed for tau-amyloid associations: earlier stages have a stronger association than later stages. These data point to the well-known finding that amyloid plays a role early in AD pathophysiology, and at later stages it has a plateauing behavior and is no longer predictive. Stage-dependent relationship to network connectivity. To assess the hypothesis that biomarkers are predicted by connectivity to pathology origination site at the aggregate level, we plotted a region’s biomarkers against its network connectivity to bilateral EC (Fig. 2B). We find moderate but significant (p < 10−3, post-Bonferroni) association between EC-connectivity and all three biomarkers; however, the association with amyloid is in fact negative. These results are also stage-dependent; with earlier stages giving a stronger association with connectivity for atrophy and tau, and the reverse for amyloid. Longitudinal relationships. The longitudinal change (difference between baseline and year-1 visit) of biomarkers was plotted against baseline in Fig. 2C. A moderate but significant association (p < 10−3, post-Bonferroni) with change of tau was found for baseline tau, but not baseline amyloid. Next we broadly assess network involvement and potential remote effect, i.e. whether baseline pattern of tau weighted by network connectivity would predict the change of tau. We used a simple model of spread of tau from baseline pattern along the network, given by the well-established network diffusion model (Raj, 2012). The hypothesis appears to have significant support for baseline tau, but not for amyloid, and incurs a stage dependency as with earlier results. Taken together, these results demonstrate significant and stage-dependent cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between tau and amyloid distributions in the Alzheimer brain.

Fig. 2.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between tau, amyloid, atrophy and the network. For each comparison, we show the associations as both scatterplots (top subpanels) and histograms (bottom subpanels). 2A: Pairwise associations between biomarkers across cohorts. 2B: Associations between biomarkers and connectivity to the entorhinal cortex. 2C: From left to right, associations between the change in tau over time and tau, amyloid, connectivity-mediated tau spreading, and connectivity-mediated amyloid spreading. For the latter two comparisons, we employed the simple association proposed by the well-known network diffusion model: , where is the network Laplacian matrix (Raj et al., 2012a).

II. Evidence-based development and adjudication of competing hypotheses of protein aggregation,

The above data snapshots provide empirical support to the hypothesis of a cross-species interaction between and tau; however, they do not reveal their exact mechanistic form, nor the mode of brain-wide protein propagation, whether connectome-mediated, proximity- or fiber distance-based. To explore various mechanistic hypotheses, we first developed a base model of network transmission of tau and (Eq (1)), where these two species evolve independently and migrate between regions via the connectome. We then extended this model to account for several different potential interactions and modes of transmission (Table 1). See SI:Note 1 for mathematical details.

Table 1.

Alternative/competing hypotheses of tau-amyloid interaction to be tested in the background of transmission mediated by network connectivity. Brief description of each hypothesis is given, along with the mathematical differential equation corresponding to it, contained in SI:Note 1. References to supporting literature for each hypothesis is provided. Two additional models of spread are given, pertaining to spread via proximity and spread via fiber distance – for these models we use the base case of no interaction between tau and amyloid.

| Hypothesis | Description | Model Equation | Supporting Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) No interaction | Tau and propagate independently on the connectivity network (Base model) | 1a, 1b | (Clavaguera et al., 2009; Iba et al., 2013; Boluda et al., 2015; Kaufman et al., 2016) |

| 2) aggregation | Tau and propagate independently on the network and local presence of facilitates the aggregation of tau | 2a, 2b | (He et al., 2018b; Gratuze et al., 2020) |

| 3) diffusion |

propagates independently on the network and local presence of increases the spread rate of tau | 3a, 3b | (He et al., 2018b; Bolmont et al., 2007) |

| 4) aggregation | Tau and propagate independently on the network and neighboring (via connectome) facilitates the aggregation of tau | 4a, 4b | (Pandya et al., 2016; Sepulcre et al., 2016a) |

| 5) aggregation | Tau and propagate independently on the network and local presence of tau increases the aggregation of | 5a, 5b | (Jackson et al., 2016) |

| 6) | Tau and propagate independently on the network and local presence of each increases the aggregation of the other | 6a, 6b | (Pooler et al., 2013b) |

| 7) Proximity-based transmission | Tau and propagate independently on the spatial proximity network | 7a, 7b | (Sepulcre et al., 2016a; Mezias and Raj, 2017a; Sepulcre et al., 2013) |

| 8) Fiber Distance-based transmission | Tau and propagate independently on the fiber distance network | 8a, 8b | (Fornari et al., 2019; Schäfer et al., 2020) |

3.1. Group level empirical validation and model fitting

We next performed model fitting on empirical group data of each model initiated at the canonical EC-seeding of tau, using a robust maximum a posteriori (MAP) inference procedure we developed (detailed in SI: Note 6). Cross-sectional group ADNI data were correlated against the fitted model’s evolution at every time , and Pearson’s R was recorded. The resulting “R-t curves”, shown in Fig. 3 for the 1-way interaction aggregation model, displayed a characteristic peak as more amyloid and tau pathology diffused into the network and increasingly recapitulated cross-sectional patterns. Subsequently model diverged from empirical pattern, decreasing R. Since our model posits that both amyloid and tau evolution happens on the same time axis, we report the model instant that maximized the posterior, rather than peak R for either tau or amyloid separately. The highest R value, , resulting from this “shared peak time”, called , is recorded for both amyloid and tau and considered as model evidence. Optimal fitted parameters shown in Table S2 indicate substantial differences between groups.

Fig. 3.

Validating evolution of model tau seeded at EC against empirical data. Left column: The top panel shows the behavior of model evidence R against model time for amyloid. The model time at which the model was evaluated against empirical data is denoted by square markers. The “glass brain” renderings show empirical amyloid-PET SUVr patterns from all 3 diagnostic groups. The R statistic between the model and empirical data are shown alongside. Middle column: The top panel shows the R between the model and empirical tau. The cross-sectional empirical tau-PET SUVr patterns from all 3 diagnostic groups are shown. Right column: Results for MRI-derived atrophy.

In total, we evaluated six theoretical interaction models (see SI:Note 1 and Table 1): 1) No-interaction model (Eqs (1)); 2) 1-way interaction model (Eqs (2)), tau affects amyloid aggregation but not vice versa; 3) 1-way interaction, amyloid affects tau aggregation but not vice versa (Eqs 3); 4) Amyloid affects tau diffusion into the network, (Eqs (4)); 5) 1-way (remote) interaction aggregation, connectome-mediated induces tau aggregation at distant sites; and 6) 2-way interaction model (Eq (6)). Each model was evaluated in identical fashion via MAP inference and identification of a single unique operating time that spans both amyloid and tau data. The numerical solutions of these models were evaluated on the canonical healthy connectome under the 86-region Desikan-Killiany parcellation. In order to assess model behavior broadly, in the following set of results we used a canonical model specification, given by the coarsely optimized (default) parameter values (refer to SI: Note 6 and Table S2 for details). Statistical comparison of these fitted models is shown in Table 2. All reported R values that are moderately to highly significant as denoted by * (p < 0.01) and ** (p < 0.001), corrected for multiple comparisons. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is also presented to compare models of different complexity.

Table 2.

Peak Pearson’s R of correlation between model and empirical regional statistics. Six theoretical interaction models’ evaluations are presented: the No-interaction model, without the interaction term ; the 1-way interaction, aggregation, whereby tau affects amyloid but not vice versa; the 1-way interaction, diffusion model, whereby amyloid influences the rate of diffusion of tau but not vice versa; the 1-way interaction, aggregation model, whereby amyloid affects tau but not vice versa; the 1-way interaction, aggregation model, whereby distant amyloid affects tau but not vice versa; and the 2-way interaction aggregation model where both tau and amyloid affect each other via .

| Empirical data | No- interaction Model (1) | 1-way interaction, aggregation (2) | 1-way interaction, diffusion (3) | 1-way interaction, aggregation (4) | 1-way (remote) interaction aggregation (5) | 2-way interaction (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMCI | 0.71 ** (163) | 0.71 ** (163) | 0.71 ** (163) | 0.71 ** (163) | 0.71 ** (163) | 0.71 ** (166) |

| LMCI | 0.49 * (223) | 0.49 * (223) | 0.49 * (223) | 0.49 * (223) | 0.49 * (223) | 0.45 * (229) |

| AD | 0.70 ** (333) | 0.70 ** (333) | 0.70 ** (333) | 0.70 ** (333) | 0.70 ** (333) | 0.70 ** (335) |

| EMCI tau | 0.33 (200) | 0.38 (202) | 0.35 (201) | 0.48 * (190) | 0.48 * (192) | 0.36 (203) |

| LMCI tau | 0.60 ** (232) | 0.60 ** (234) | 0.49 * (247) | 0.75 ** (206) | 0.73 ** (211) | 0.70 ** (219) |

| AD tau | 0.57 ** (322) | 0.51 * (332) | 0.52 * (331) | 0.73 ** (296) | 0.71 ** (301) | 0.65 ** (315) |

| EMCI atrophy | 0.34 (171) | 0.32 (176) | 0.33 (175) | 0.35 (174) | 0.33 (178) | 0.37 (175) |

| LMCI atrophy | 0.60 ** (158) | 0.60 ** (162) | 0.56 * (171) | 0.62** (158) | 0.61 ** (159) | 0.48 * (184) |

| AD atrophy | 0.52 * (316) | 0.38 (331) | 0.39 (330) | 0.66** (299) | 0.62 ** (304) | 0.58 ** (312) |

Highly significant correlations:

(p < 0.001), moderately significant:

(p < 0.01), all reported post Bonferroni correction.

Aikeke information criterion (AIC) is reported for each model, in brackets. The highest R and lowest AIC values are highlighted in boldface.

Amyloid.

Correlations between model and empirical AV45 SUVr are shown in Table 2. We found that all models worked equally well high significance for all three cohorts (, 0.49, and 0.70 for EMCI, LMCI, and AD, respectively), indicating that tau feedback onto amyloid is not required to explain its patterns of deposition at any stage of disease. This might reflect the well-known plateau effect of amyloid – also indicated by R-t curve (Fig. 3, top left) that reaches a peak and then plateaus. Note, model time t has arbitrary units that may not directly correspond to empirical duration in years.

Tau.

The network propagation of modeled tau starting from its seeding in EC was computed and its correspondence to regional group-average empirical AV1451-PET was assessed (Table 2). In contrast to amyloid, we found significant differences between different interaction models. The 1-way interaction ( aggregation) was the most accurate and significant (post-Bonferroni) predictor of empirical tau-PET for all three cohorts: (EMCI: R = 0.51, p < 0.01; LMCI: R = 0.75, p < 0.001; AD: R = 0.73, p < 0.001), and achieved the lowest AIC. Only the 1-way (remote) interaction model exhibited comparable correlation, but at the cost of additional model complexity hence lower AIC. None of the other proposed interaction models consistently outperformed the no interaction model (as assessed by AIC). Also unlike amyloid, the R-t curves of tau for 1-way interaction aggregation model showed a slow and steady rise and a distinct late peak without a plateau effect (Fig. 3, middle column). Correlation with EMCI group is poorer than other groups, likely due to lower PET uptake and inter-subject heterogeneity. These conclusions were further substantiated by performing pairwise t-tests between models following the Fisher’s R-to-z correction (Table S3).

Atrophy.

Since tau is highly co-localized with regional atrophy, we also show a comparison with MRI-derived group atrophy. However, we did not fit the model again to atrophy, instead borrowing the tau-fitted models for each cohort, under the assumption that tau is the primary, and atrophy is a surrogate for tau. Overall, the atrophy results were similar to but slightly weaker than tau-PET results. For the EMCI cohort, associations were similar for all models, indicating that the no interaction model was sufficient for explaining early neurodegeneration patterns (Table 2); this is likely due to the low effect size measurable on MRI in this cohort. Associations with LMCI and AD were highly significant (p < 0.001) for the best model, 1-way interaction , with R = 0.62 for LMCI and R = 0.66 for AD. However, LMCI atrophy was more or less equivalently associated with the no interaction and each of the three 1-way interaction models. These conclusions were further substantiated by pairwise Fisher’s R-to-z t-tests between models (Table S3).

3.1.1. Time of peak:

The of maximum posterior followed the expected order: for AD > LMCI > EMCI (Fig. 3, top). It is challenging to fit an accurate time axis to empirical data, since it does not have a measure of pathology duration – which may never be known. Interestingly, the peak for tau occurs more than a decade (in model “years”) after the plateau seen for amyloid – perhaps recapitulating well-known clinical and pathological examinations that suggest a decade-long delay between the two processes.

3.2. Illustration of base model of and tau with no interactions

To get a qualitative picture, we generated surface renderings of the evolution of theoretical regional amyloid distribution under the no-interaction model as it propagates into the structural network (Fig. 4A, left). Modeled amyloid evolution appeared to recapitulate the classic amyloid progression as proposed by Thal et al (Thal et al., 2002). and amyloid PET patterns (Jagust and Mormino, 2011), proceeding from medial frontal and precuneus (areas with high baseline metabolism) into the wider network, only slowly entering temporal cortices. The middle column shows the evolution of tau on the same network under the no interaction model, starting from seeding event in the bilateral EC. This models largely stays within temporal cortices, with low but non-zero spread into other regions.

Fig. 4.

The evolution of model dynamics of amyloid and EC-seeded tau. A: Spatiotemporal evolution of the model evaluated by numerical integration of Eqs (1a, 2a), on the 86 × 86 healthy Desikan connectome using default model parameters. The first column shows the evolution of amyloid, the second column of tau only, and the third column of amyloid-facilitated tau. Each sphere represents a brain region, its diameter is proportional to pathology burden at the region, and is color coded by lobe (blue = frontal, purple = parietal, red = occipital, green = temporal, cyan = cingulate, black = subcortical). B: Prediction of Braak stages using computational model using a 6-stage “computational Braak” staging system based on the time-of-arrival calculation of each group’s fitted eNDM model, shown for the no interaction model (left) and 1-way interaction aggregation model.

3.3. Network transmission of and tau with cross-species interaction

Of the 6 interaction models encompassing various mechanistic hypotheses, here we detail the best interaction model ( aggregation) (Hurtado et al., 2010; Ittner and Götz, 2011; Götz et al., 2001), illustrated in Fig. 4A right. Model tau remained confined to the medial temporal lobe until sufficient levels of had spread to and accumulated there. There onward, in contrast to the “pure tau” evolution, it took on a more aggressive trajectory, spreading first to nearby limbic, then basal forebrain, then parietal, lateral occipital and other neocortical areas, in close concordance with Braak’s six tau stages (Braak and Braak, 1991) (Fig. 4B). Thus, the facilitation of tau by amyloid does not lead to colocalization of the two until late stages, helping explain why regional patterns do not coincide with tau and atrophy patterns. Conversely, the absence of the interaction term led modeled tau to remain confined to the temporal lobe (Fig. 4A, middle), mirroring primary age-related tauopathy (PART), a new classification for mild neurofibrillary degeneration in the medial temporal lobe, but no plaques (Crary et al., 2014).

Figure S3 shows the global accumulation of theoretical pathology over model time, evaluated at default parameters. All proteins increase over time, but amyloid-facilitated tau diverges dramatically from the non-facilitated tau at around t = 15, mirroring Fig. 4. Figure S3 makes it clear that while the “pure” tau model also captures empirical data, it does so far slower and achieves far less correlation strength than the facilitated version. Additionally, for comparison, the AAL-connectome-based model evolution is shown in Figure S4, with very similar behavior, indicating that the choice of atlas or processing pipeline did not drive results.

3.4. Predicting Braak stages using computational model

Using the time-of-arrival calculation of each group’s fitted eNDM model, we developed a 6-stage “computational Braak” staging system. The predicted Braak stages strongly agree with the original Braak stages, applied to the DK atlas parcellation, achieving R = 0.76, p < 10−6 for the best-adjudicated model (Fig. 4B, right). In comparison, the non-interacting model (Fig. 4B, left), while being significant at R = 0.64, is substantially worse, suggesting that amyloid→ tau interaction is a necessary factor in Braak staging.

3.5. Permutation testing to demonstrate disease specificity

Various permutation tests were deployed to demonstrate that the presented model only recapitulates empirical regional distributions when it is applied in the correct region order and to the correct human connectome, detailed in SI: Note 7. Under 500 random permutations of atrophy and tau (Figure S5-A), and of the connectome itself (Figure S5-B) the above-reported R values remain highly significant compared to these “null” distributions (p < 10−3 for all groups). This was true whether the Pearson or Spearman correlation was used as the performance metric (Figure S6).

3.6. Comparison of different modes of spread

We implemented two alternative modes of spread (Table 1): 1) Pathology spread depends only on the shortest Euclidean distance; and 2) transmission between regions is inversely proportional to the average length of fiber projections between regions. See Methods and quantitative comparison in Table 3. The model in each case was refitted using the MAP estimator as before, hence each fitted model may represent the best-case scenario for that hypothesis. We used paired t-tests following Fisher’s R-to-z transformation to statistically compare different spread models, while accounting for the correlation between dependent variables. We found that: 1) For both tau and amyloid evolution, connectome-mediated spread model gave the closest correspondence to empirical data; and 2) Euclidean spatial spread was slightly but not significantly superior to fiber distance-based spread. For these comparisons we chose the best interaction model identified in Table 1 (1-way aggregation) for all three networks. However, we repeated these comparisons using other interaction terms as well, and did not find significant differences in performance (Fisher’s p-value = N.S.).

Table 3.

Pearson’s R of correlation between alternative spread models and empirical regional statistics. Fisher’s R-to-z transform was computed between the connectome and the alternative modes of spread, and its p-value is shown alongside. The connectome-mediated model significantly outperforms the two distance-based models (p values denoted in red font).

| Empirical data | interaction, Connectivity | Fiber Distance | Fisher R-to-z, Fiber vs C | Euclidean Distance | Fisher R-to-z, Euclidean vs C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMCI | 0.71 | 0.56 | p < 0.01 | 0.57 | p < 0.01 |

| LMCI | 0.49 | 0.43 | p = 0.10 | 0.42 | p = 0.09 |

| AD | 0.70 | 0.56 | p < 0.01 | 0.57 | p < 0.01 |

| EMCI tau | 0.48 | 0.25 | p < 0.01 | 0.24 | p < 0.01 |

| LMCI tau | 0.75 | 0.31 | p < 0.01 | 0.35 | p < 0.01 |

| AD tau | 0.73 | 0.34 | p < 0.01 | 0.36 | p < 0.01 |

| EMCI atrophy | 0.35 | 0.00 | p < 0.01 | 0.18 | p = 0.03 |

| LMCI atrophy | 0.62 | 0.29 | p < 0.01 | 0.41 | p = 0.025 |

| AD atrophy | 0.66 | 0.17 | p < 0.01 | 0.22 | p < 0.01 |

3.7. Translational aspects

Having established the network model’s validity on group data, and having determined which modes of the tau-amyloid-network interactions are relevant and empirically supported, we showcase two key results related to translational aspects in patients: etiologic heterogeneity and the capacity to predict an individual subject’s spatiotemporal trajectory of AD.

3.7.1. Uncovering etiologic heterogeneity: Repeated seeding to assess alternative seeding sites

The entorhinal cortex (EC) was chosen above as the canonical tau seeding site. To establish other regions’ seeding plausibility, we repeatedly simulated the selected network interaction model seeded from every possible region bilaterally. For each seed region, peak Pearson’s R between model and ADNI tau-PET data is shown in Fig. 5A. EC is among the best overall cortical seeding sites, while hippocampus (HP) is the best subcortical site. Other prominent seeding sites include parahippocampal gyrus (PHP) and fusiform gyrus (Fus), which are adjoining EC and appear frequently similar in tau uptake to EC on PET imaging. Thus the quantification of these structures as likely seeding locations affirms our model’s relevance and plausibility. The evolution of pathology from some of these non-EC sites is illustrated in Figures S7 and S8, for HP-seeding and IT-seeding, respectively. While substantially similar to EC seeding of Fig. 3, a notable difference is that HP seeding leads to higher involvement of medial temporal and subcortical structures. Of these four plausible seeding sites, EC is unique in giving consistently one of the highest seeding likelihood despite having lower levels of empirical tau deposition than others.

Fig. 5.

Translational applications. A: Bar charts of repeated seeding of each region in turn. For each seed region, peak Pearson’s R over model time, corresponding to the correlation between the best interaction model (amyloid-facilitated tau aggregation) and empirical tau PET data, is shown, for each of the 3 diagnostic groups: EMCI (top), LMCI (middle) and AD (bottom). Entorhinal cortex (EC) is amongst the best cortical seeding sites and Hippocampus (HP) the best subcortical site. Other likely seeding sites include Fusiform (Fus) and Parahippocampal gyrus (PHP). B: Histograms of achieved by fitting the model parameters to individual subjects’ baseline regional tau data, after imposing a common seeding site located at the EC (left) or after using the best seeding site for each subject (right). Here the best model combination from Table 2 was used: 1-way interaction on the structural connectivity graph, and the evaluation was performed on tau-PET scans in ADNI3. Average over all subjects within each diagnostic group is shown in red dashed line.

3.7.2. Individual subject fitting and prediction

For translational applications we must necessarily move away from group-wise to individual subjects, while accommodating both etiologic heterogeneity as well as potentially subject-specific model parametrization. In order to achieve this we deployed our robust inference procedure (see SI: Note 6) on individual subjects’ multimodal regional biomarkers from ADNI-3 (demographics in Table S1), under the 1-way interaction aggregation model. Fig. 5B shows the histograms of between observed and model-predicted regional tau distribution in each subject. For comparison we show the results of both canonical (EC) seeding and each individual’s best seeding site. EC seeding was significantly worse (paired t-test after Fisher R-to-z: p < 10−7, corrected), implying that a common seeding site may not be appropriate for all subjects and revealing a potential etiological factor behind observed heterogeneity in AD-spectrum subjects. With individual-specific seeding and model fitting, we were able to achieve excellent prediction of the subjects’ tau distributions, with ranging widely up to a maximum of 0.9 and mean of 0.65 for LMCI and AD, and slightly lower for EMCI subjects. The mean across individuals in Fig. 5B is similar to but slightly lower than the achieved on the group-averaged tau data of Fig. 4 and Table 2, which is expected due to heterogeneity as well as measurement noise in individual subjects. It is also noteworthy that canonical EC seeding fails in approximately half of the subjects in EMCI and LMCI cohorts (i.e.) but only a small minority of diagnosed AD patients: indicating that higher stages have lower etiologic heterogeneity.

Demonstration of longitudinal fitting on individual subjects.

Due to far fewer longitudinal data being available, we did not pursue a thorough investigation of prediction of longitudinal progression. Nonetheless, using the samples available to us at the time of analysis, we provide in Figure S9, a preliminary demonstration of this aspect. Baseline data of each individual was fitted using the procedure shown in Fig. 5, for the case of individually-optimized seeding patterns. Those baseline Rmax values are plotted using the left-most circles in Figure S9. Then, the model was initialized to the baseline tau-PET, and using the same model parameters, it was fitted to subsequent time points available in ADNI3. These data show that using current (baseline) tau regional distributions, and the network model fitted to that baseline, one can confidently predict subsequent time points.

4. Discussion

The protein-protein interaction of amyloid and tau, commonly denoted by the A-T-N rubric (Jack et al., 2016), is a central feature and key to understanding AD pathophysiology (Ittner and Götz, 2011; Walker et al., 2018; Kara et al., 2018; King et al., 2006), but has been difficult to reconcile with the observations of dissociated spatial distribution of tau and amyloid. The exact cause-effect mechanisms by which amyloid and tau regulate each other and cause downstream neurodegeneration and symptomatology remain poorly understood and empirically unsupported in human disease. Prior mechanistic studies in model organisms may not be entirely germane to human disease and empirical evidence for them is difficult if not impossible to acquire in AD patients. Yet, the interrogation of these aspects is critical to achieve disease understanding and future therapeutic options. In this study we took a computational rather than experimental approach to explore these issues directly in human AD. Our objectives were twofold: First, to test whether a mathematical encoding of network spread due to trans-neuronal proteopathic transmission (Jucker and Walker, 2013; Raj et al., 2012a; Seeley et al., 2009), combined with local interaction between amyloid and tau pathologies, is capable of recapitulating observed pathology progression in AD; Second, to infer quantitatively the factors of cross-species interactions, their causal direction, and their associated kinetic rate parameters in patients’ brains.

Our major findings are: First, the joint model successfully recapitulates the spatiotemporal progression of both amyloid and tau. The local production of driven by glucose metabolism followed by subsequent network spread correctly predicts the spatial distribution of empirical . Starting from EC, model tau predicts empirical tau, with prominence in temporal areas, followed by network ramification in limbic and wider cortices. Second, the best interaction model is one where influences tau aggregation, but not tau transmission. This one-way interaction is an essential component of their spatiotemporal propagation predicted by the computational model, without which it does not fully recapitulate empirical amyloid and tau spatial patterns in patients. This model also excels in computationally predicting tau Braak stages. Third, 2-way interaction is worse than 1-way interaction in recapitulating empirical patterns, and the reverse interaction () does no better than the no interaction model. Using our “computational Braak” results, we showed that these alternate interactions are less consistent with Braak staging. These data constitute to our knowledge the first numerically rigorous evidence of the precise mode of amyloid-tau interaction in human AD. Fourth, connectome-mediated spread of tau outperforms other modes of spread, whether by proximity or by fiber length, statistically confirming hitherto descriptive observations that spatial or anisotropic diffusion are insufficient to correctly predict AD pathology. We verified these group-average results on individual subjects, both at baseline and longitudinally, and found essentially equivalent results.

The overall picture that emerges resembles the broad hypothesis posed at the beginning of the paper (Fig. 1A), but with a distinct inclination toward amyloid-facilitation rather than the classic amyloid-cascade hypothesis: Following diffuse production of amyloid in proportion to metabolism, and focal production of tau at the EC, aggregation into plaques and tangles occur at networked sites following graph topology. Tau pathology is further aggravated by amyloid, but not vice versa. Finally, classic, spatially divergent amyloid and tau patterns are established – frontal-dominant for amyloid and temporal dominant for tau. As discussed below, these results point to an underlying parsimony and universality, with the potential to explain several poorly understood aspects of AD progression.

4.1. Network transmission drives divergent spatiotemporal progression of and tau

That the spatiotemporal patterning of , tau and atrophy are distinct is well-known but not fully understood (La Joie et al., 2012) and appears at odds with the prevailing amyloid cascade hypothesis (Jagust and Mormino, 2011; Fjell and Walhovd, 2012). Soluble is sometimes invoked to help explain the discrepancy, but this has been questioned (Jagust and Mormino, 2011). Our first finding, that divergent evolution of theoretical amyloid and tau on the same network successfully recapitulates empirical progression, suggest that the governing mechanism behind these long-observed discrepancies may be related to network spread combined with metabolic drivers. Importantly, this spatial divergence holds even in the presence of amyloid-facilitation.

Indeed, we find that production driven by glucose metabolism and local APP pool, followed by a certain amount of network dissemination, significantly recapitulates regional amyloid deposition (Fig. 3): R = 0.71 (EMCI), R = 0.70 (AD). Neural activity is known to regulate the production and secretion of (Jagust and Mormino, 2011). In transgenic mice, neural activity affects secretion (Kamenetz et al., 2003) through synaptic exocytosis (Cirrito et al., 2005) and later deposition of plaques (Bero et al., 2011), by modulating the release of cleavage products of APP (Nitsch et al., 1993). In humans, release parallels fluctuations in synaptic activity in human sleep/wake cycles (Gilestro et al., 2009). AV45 uptake is higher in hubs, multimodal cortices (Buckner et al., 2009) and default mode network, all characterized by higher baseline metabolism (Buckner et al., 2005). In contrast to , tau in our models proceeded outward from EC, to lateroinferior temporal cortices, thence to parietal, lateral occipital and medial frontal areas, in close concordance with Braak’s six tau stages (Braak and Braak, 1996) (Fig. 4B). The best model yielded highly significant correlations against AV1451-PET data (Fig. 3): R = 0.75 (LMCI), R = 0.73 (AD). We found that the EC was the consensus best seeding site at both a group and individual level (Fig. 5), although substantial heterogeneity was apparent within each cohort. Further, the model correlated with MRI-derived regional atrophy, an excellent surrogate for underlying tau (Whitwell et al., 2008; Vemuri et al., 2008), with high significance. The presented correlations are significantly stronger than 500 random permutations (Figure S5), suggesting that the model is specific to the human connectome and brain topography.

4.2. -facilitated tau aggregation plays a critical role in progression

Our second major result is that -tau interaction (see e.g (He et al., 2018b; Gratuze et al., 2020).) played an important role in forcing the extra-temporal spread of tau. influences the course and severity of tau and atrophy (Hurtado et al., 2010; Ittner and Götz, 2011; Götz et al., 2001). In our mathematical exposition, modeled tau seeded at EC remained confined to the temporal lobe until sufficient levels of had spread to and accumulated in temporal cortices (Fig. 4). The amyloid-facilitated model tau then started diverging from pure tau, taking on a more aggressive trajectory, spreading first to nearby limbic, then basal forebrain, then other neocortical areas. Thus, the facilitation of tau by amyloid does not lead to colocalization of the two until late stages, further helping to explain why regional patterns do not coincide with tau and atrophy patterns (Vemuri et al., 2009; Jack and Holtzman, 2013). Conversely, the absence of the interaction term led modeled tau to remain confined to the temporal lobe (Fig. 4), mirroring primary age-related tauopathy (PART), a new classification for mild neurofibrillary degeneration in the medial temporal lobe, but no plaques (Crary et al., 2014). Thus, medial temporal NFTs may be involved in two divergent processes: AD and PART. Purely tau-specific abnormalities (e. g., the MAPT gene H1 haplotype) would predispose the subject to PART, whereas additional abnormalities (e.g., the dysregulation of presenilin, APP or APOE ε4 allele) would cause AD predisposition (Crary et al., 2014). In the present work, the non-facilitated tau model evolved less rapidly and was less successful than amyloid-facilitated tau model (Table 2, Fig. 3). These results provide model-based support to prior neuroimaging observations: Sepulcre et al. found several convergence zones in temporal and entorhinal cortex where amyloid and tau might interact (Sepulcre et al., 2016b), (Marquié et al., 2015). Franzmeier et al. showed that tau uptake in -controls was restricted to IT, but was observed in extra-temporal areas in + subjects (Franzmeier et al., 2019). Remarkably, our theoretical modeling also gives the same regions (IT and EC – see Fig. 4) as key areas of convergence between amyloid and tau, where the “arrival” of the former is accompanied by prominent deposition of the latter.

Ittner and Götz (Ittner and Götz, 2011) have suggested three modes of interaction: (1) drives tau pathology; (2) synergistic toxic effects of and tau; and (3) tau mediates toxicity. and pathological tau co-localize in synapses (Fein et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2010), and tau is essential for -induced neurotoxicity (Amadoro et al., 2011). seeded exogenously in tau transgenic mice elicited aggressive tau pathology in retrogradely connected regions (Götz et al., 2001). Amyloid pathology accelerated tau deposition in double transgenic mice, but the reverse effect was not observed (Hurtado et al., 2010). A “seminal cell biological event” in AD pathogenesis was suggested, whereby acute, tau-dependent loss of microtubule integrity is caused by exposure of neurons to readily diffusible (King et al., 2006). However, the question remains controversial and other studies have suggested that tau propagation across connected regions is unlikely to be a gain of function mediated by the presence of (Franzmeier et al., 2020). Nonetheless, there are other mechanistic routes to enact this interaction, such as -related microglial activation promoting local tau-hyperphosphorylation (Heurtaux et al., 2010), enhancing tau spread across connected neurons (Maphis et al., 2015b), PET imaging confirms early microglial activation in inferior temporal sites of tau accumulation (Hamelin et al., 2016). Hence, an indirect mediation of may occur via microglial activation; see review (Busche et al., 2019).

4.3. Alternative models of spread and interaction are less plausible

None of the other five theoretical interaction models (Table 1) compared favorably to . This included amyloid effect on tau diffusion; and its (remote) interaction with tau aggregation – two popular hypotheses in recent literature: We find little support for the role of amyloid in exacerbating tau spread, potentially mediated by microglia (He et al., 2018b; Bolmont et al., 2007). Remote effect of amyloid on tau was posited as a potential explanation of the dissociation between the two (La Joie et al., 2012; Pandya et al., 2016; Sepulcre et al., 2016a). Sepulcre et al. find that tau accumulation in temporal areas relates to “massive elsewhere in the brain”, linking both pathologies at the large-scale level (Sepulcre et al., 2016b) (Marquié et al., 2015). However our analysis does not support this view. Surprisingly, the 2-way model (e.g (Pooler et al., 2013b).) was insignificantly different from the 1-way model for both amyloid and tau, while they are identical for amyloid (Table 2). The tau→amyloid interaction (e.g (Jackson et al., 2016).) performed relatively worse on tau data as well, suggesting that tau driving amyloid is not a clinically relevant factor in pathology ramification, and its addition gives poorer AIC scores. That amyloid results are identical for both modes was somewhat surprising, but this may be due to amyloid evolution peaking before a significant tau-influence was observed. Hence, by the time tau can begin to influence amyloid, the pear R against empirical amyloid distribution has already been reached.

Intriguingly, alternative spread models based on proximity (Sepulcre et al., 2016a, 2013; Mezias and Raj, 2017a) or fiber distance (Fornari et al., 2019; Schäfer et al., 2020) did not give good correspondence with empirical tau, and were essentially identical for amyloid (Table 3). The amyloid result mirrors our previous exploration in mouse data (Mezias and Raj, 2017b), where too connectivity was not better than spatial spread. Taken together, our findings serve to rule out or deprioritize many alternative hypotheses and mechanisms of AD progression.

4.4. Relation to other modeling efforts

Franzmeier et al. reported that functionally connected regions show correlated tau accumulation rates in AD patients. Their approach relied on statistical rather than mathematical modeling of network processes (Franzmeier et al., 2020, 2019). As noted earlier, other network spread models of single pathological species have been previously reported (Pievani et al., 2011; Raj et al., 2015, 2012b; Zhou et al., 2012b; Weickenmeier et al., 2019; Fornari et al., 2019; Iturria-Medina et al., 2014, 2017). The anisotropic diffusion model (Weickenmeier et al., 2019), the Fisher-Kolmogorov model (Fornari et al., 2019; Schäfer et al., 2020), epidemic spread model (Iturria-Medina et al., 2014), etc are all attempts to encode the process of network-based transmission of pathology. Relatively fewer accounts are available of the joint modeling of both amyloid and tau as they evolve on the same network and interact locally – the unique contribution of the present work. A recent study revealed amyloid interaction with tau, yet again using statistical rather than mathematical modeling (Binette et al., 2022). While this study suggests potential interaction, here we are able to interrogate the actual mechanistic modes by which those interactions may be achieved. Gradients of functional and structural connectomes were also shown to correlate to tau deposition (Ottoy et al., 2024), yet this would be entirely expected based on the notion of “persistent eigenmodes” resulting from the process of network spread (Raj et al., 2012b). Therefore the key contribution of this study in comparison with these other approaches is that we set up mathematical and statistical tests to characterize the extent and model of interaction between tau and amyloid, and gather rigorous evidence to determine the most likely mode of interaction.

4.5. Broader implications and future work

The most important implication is that the best-adjudicated model ( interaction accompanied by network spread) gives a clear mechanistic target for future drug design. Scientifically, this study bolsters the hypothesis of trans-neuronal transmission by demonstrating its role in humans, an aspect that cannot be studied directly. Clinically, the new model could provide a unique opportunity for computational tracking and prediction of individual patients, especially after integrating multimodal imaging biomarkers (e.g., MRI, tau- and amyloid-PET); we have provided proof-of-concept in Fig. 5. Subject-specific seeding sites gave much higher accuracy than uniform common seeding of EC – revealing important inter-subject heterogeneity of etiology and ramification. We also provided in in Figure S9 preliminary data show that using the network model fitted to current (baseline) tau regional distribution, one can confidently predict subsequent time points. Since trans-neuronal spread is a common feature of neurodegeneration, the best-adjudicated model may be equally applicable to co-morbid pathologies seen in other disorders like Parkinson’s, Lewy Body, frontotemporal and other dementias.

Future model extensions are planned to incorporate machine learning and data-driven multifactorial (Iturria-Medina et al., 2017) and event-based models (Young et al., 2014; Oxtoby et al., 2017), which give disease duration, not available here. Applications of the model as outcome measures in clinical drug trials are planned.

4.6. Limitations

Neuroimaging software pipelines have several limitations in image resolution, noise and artifacts (Raj et al., 2012a). DTI suffers from susceptibility artifacts and poor resolution. PET has poor resolution compared to MRI, and AV45 and AV1451 tracers show significant non-specific binding. Tractography can under-estimate crossing fibers and long tracts. Small subcortical structures can present challenges in inferring connectivity. This study was cross sectional hence longitudinal information was not utilized. Our model does not make a distinction between aggregate or oligomeric amyloid/tau. It may be more likely that raised intracellular β-amyloid monomers or oligomers, instead of aggregates thereof, are the toxic agent that triggers further intracellular tau aggregation and then spread. This would explain why clearance of extracellular β-amyloid aggregates by immunotherapy has been largely ineffective as an AD treatment. At the moment we are unable to separate these two possibilities without additional empirical data on oligomeric species that is currently not widely available in humans.

Further, although we found that seeding of tau in the EC gives the best results, we were unable to explore the likelihood that it turn, tau in EC originated from the locus ceruleus (LC) (Braak and Braak, 1991). This is owing to the limitations of PET/MRI spatial coverage, co-registration and atlas-based parcellation, due to which our data do not have any atlas regions in the brainstem or in the LC. Note, this is not a limitation of our mathematical model but of empirical neuroimaging data required to support this aspect.

Finally, the joint model must be interpreted in light of a small temporal window available to the modeler. Our co-evolving amyloid and tau model may be the most pertinent for the LMCI group, whose cortical β-amyloid may still be rising along with tau aggregates. It is possible that this phase of the disease may not properly capture EMCI (due to miniscule levels of both pathologies) or mature AD (due to the plateau effect). Fig. 3 suggests that all 3 groups showed a similar plateauing behavior with respect to β-amyloid. Nonetheless, a short observation window precludes us from fully exploring this aspect.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2025.102750.

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to acknowledge assistance in gathering ADNI data by Dr Duygu Tosun, Daren Ma and Areez Malik. This research was supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: R01NS092802, R01EB022717, RF1AG062196, R56AG064873, R01AG072753, R01AG087302.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statistical and computational modeling demonstrates how amyloid and tau interact with each other and the connectome to produce Alzheimer progression observable on human neuroimaging.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Amadoro G, et al. , 2011. Endogenous causes cell death via early tau hyperphosphorylation. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 969–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai H, et al. , 2015. Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nat. Neurosci 18, 1584–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero AW, et al. , 2011. Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-β deposition. Nat. Neurosci 14, 750–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binette A, Franzmeier N, Spotorno N, Ewers M, et al. , 2022. Amyloid-associated increases in soluble tau relate to tau aggregation rates and cognitive decline in early Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun 13, 6635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolmont T, et al. , 2007. Induction of tau pathology by intracerebral infusion of amyloid-beta -containing brain extract and by amyloid-beta deposition in APP x Tau transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol 171, 2012–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boluda S, et al. , 2015. Differential induction and spread of tau pathology in young PS19 tau transgenic mice following intracerebral injections of pathological tau from Alzheimer’s disease or corticobasal degeneration brains. Acta Neuropathol. 129, 221–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, 1991. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, 1996. Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl 165, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, et al. , 2005. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J. Neurosci 25, 7709–7717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, et al. , 2009. Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci 29, 1860–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche MA, et al. , 2019. Tau impairs neural circuits, dominating amyloid-β effects, in Alzheimer models in vivo. Nat. Neurosci 22, 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, et al. , 2005. Synaptic activity regulates interstitial fluid amyloid-beta levels in vivo. Neuron 48, 913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavaguera F, et al. , 2009. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat. Cell Biol 11, 909–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crary JF, et al. , 2014. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 128, 755–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein JA, et al. , 2008. Co-localization of amyloid beta and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease synaptosomes. Am. J. Pathol 172, 1683–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, 2012. Neuroimaging results impose new views on Alzheimer’s disease–the role of amyloid revised. Mol. Neurobiol 45, 153–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornari S, Schäfer A, Jucker M, Goriely A, Kuhl E, 2019. Prion-like spreading of Alzheimer’s disease within the brain’s connectome. J. R. Soc. Interface 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeier N, et al. , 2019. Functional connectivity associated with tau levels in ageing, Alzheimer’s, and small vessel disease. Brain 142, 1093–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeier N, et al. , 2020. Functional brain architecture is associated with the rate of tau accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun 11, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost B, Diamond MI, 2010. Prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 11, 155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilestro GF, Tononi G, Cirelli C, 2009. Widespread changes in synaptic markers as a function of sleep and wakefulness in drosophila. Sci. (80-. ) 324, 109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser MF, et al. , 2013. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 80, 105–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM, 2001. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science 293, 1491–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratuze M, et al. , 2020. Impact of TREM2R47H variant on tau pathology–induced gliosis and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest 130, 4954–4968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelin L, et al. , 2016. Early and protective microglial activation in Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective study using 18 F-DPA-714 PET imaging. Brain 139, 1252–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ, 2002. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, et al. , 2018a. Amyloid-β plaques enhance Alzheimer’s brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat. Med 24, 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, et al. , 2018b. Amyloid-β plaques enhance Alzheimer’s brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat. Med 24, 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurtaux T, et al. , 2010. Microglial activation depends on beta-amyloid conformation: role of the formylpeptide receptor 2. J. Neurochem 114, 576–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado DE, et al. , 2010. A{beta} accelerates the spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology and augments tau amyloidosis in an Alzheimer mouse model. Am. J. Pathol 177, 1977–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iba M, et al. , 2013. Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy. J. Neurosci 33, 1024–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iba M, et al. , 2015. Tau pathology spread in PS19 tau transgenic mice following locus coeruleus (LC) injections of synthetic tau fibrils is determined by the LC’s afferent and efferent connections. Acta Neuropathol. 130, 349–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittner LM, Götz J, 2011. Amyloid-β and tau–a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 12, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturria-Medina Y, Carbonell FM, Sotero RC, Chouinard-Decorte F, Evans AC, 2017. Multifactorial causal model of brain (dis)organization and therapeutic intervention: application to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 152, 60–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturria-Medina Y, Sotero RC, Toussaint PJ, Evans AC, 2014. Epidemic spreading model to characterize misfolded proteins propagation in aging and associated neurodegenerative disorders. PLoS Comput. Biol 10, e1003956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr, et al. , 2010. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 9, 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, et al. , 2016. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Holtzman DM, 2013. Biomarker modeling of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 80, 1347–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RJ, et al. , 2016. Human tau increases amyloid β plaque size but not amyloid β-mediated synapse loss in a novel mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci 44, 3056–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Mormino EC, 2011. Lifespan brain activity, β-amyloid, and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Cogn. Sci 15, 520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker M, Walker LC, 2013. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 501, 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz F, et al. , 2003. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron 37, 925–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara E, Marks JD, Aguzzi A, 2018. Toxic protein spread in neurodegeneration: reality versus fantasy. Trends Mol. Med 24, 1007–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman SK, et al. , 2016. Tau prion strains dictate patterns of cell pathology, progression rate, and regional vulnerability in vivo. Neuron 92, 796–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King ME, et al. , 2006. Tau-dependent microtubule disassembly initiated by prefibrillar β-amyloid. J. Cell Biol 10.1083/jcb.200605187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Joie R, et al. , 2012. Region-specific hierarchy between atrophy, hypometabolism, and β-amyloid () load in Alzheimer’s disease dementia. J. Neurosci 32, 16265–16273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso R, et al. , 2019. CSF1R inhibitor JNJ-40346527 attenuates microglial proliferation and neurodegeneration in P301S mice. Brain 142, 3243–3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maphis N, et al. , 2015b. Reactive microglia drive tau pathology and contribute to the spreading of pathological tau in the brain. Brain 138, 1738–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maphis N, et al. , 2015a. Reactive microglia drive tau pathology and contribute to the spreading of pathological tau in the brain. Brain 138, 1738–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquié M, et al. , 2015. Validating novel tau positron emission tomography tracer [F-18]-AV-1451 (T807) on postmortem brain tissue. Ann. Neurol 78, 787–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezias C, Raj A, 2017b. Analysis of amyloid-β pathology spread in mouse models suggests spread is driven by spatial proximity, not connectivity. Front. Neurol 8, 653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezias C, Raj A, 2017a. Analysis of Amyloid-β pathology spread in mouse models suggests spread is driven by spatial proximity, not connectivity. Front. Neurol 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch RM, Farber SA, Growdon JH, Wurtman RJ, 1993. Release of amyloid beta-protein precursor derivatives by electrical depolarization of rat hippocampal slices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 90, 5191–5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottoy J, Kang MS, Tan JXM, et al. , 2024. Tau follows principal axes of functional and structural brain organization in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun 15, 5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxtoby NP, et al. , 2017. Data-driven sequence of changes to anatomical brain connectivity in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurol 8, 580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya S, Kuceyeski A, Raj A. & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. The Brain’s Structural Connectome Mediates the Relationship between Regional Neuroimaging Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 55, 1639–1657 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Nievas BG, et al. , 2013. Dissecting phenotypic traits linked to human resilience to Alzheimer’s pathology. Brain 136, 2510–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pievani M, de Haan W, Wu T, Seeley WW, Frisoni GB, 2011. Functional network disruption in the degenerative dementias. Lancet Neurol. 10, 829–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooler AM, et al. , 2013b. Tau - amyloid interactions in the rTgTauEC model of early Alzheimer’s disease suggest amyloid induced disruption of axonal projections and exacerbated axonal pathology. J. Comp. Neurol 521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooler AM, Phillips EC, Lau DHW, Noble W, Hanger DP, 2013a. Physiological release of endogenous tau is stimulated by neuronal activity. EMBO Rep. 14, 389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovici GD, et al. , 2010. Increased metabolic vulnerability in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease is not related to amyloid burden. Brain 133, 512–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, et al. , 2015. Network diffusion model of progression predicts longitudinal patterns of atrophy and metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep. Print 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Kuceyeski A, Weiner M, 2012a. A network diffusion model of disease progression in dementia. Neuron 73, 1204–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Kuceyeski A, Weiner M, 2012b. A network diffusion model of disease progression in dementia. Neuron 73, 1204–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer A, Mormino EC, Kuhl E, 2020. Network diffusion modeling explains longitudinal tau PET data. Front. Neurosci 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Crawford RK, Zhou J, Miller BL, Greicius MD, 2009. Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron 62, 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulcre J, et al. , 2016b. In vivo tau, amyloid, and gray matter profiles in the aging brain. J. Neurosci 36, 7364–7374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulcre J, et al. , 2016a. In vivo tau, amyloid, and gray matter profiles in the aging brain. J. Neurosci 36, 7364–7374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Becker A, Sperling R, Johnson KA, 2013. In vivo characterization of the early states of the amyloid-beta network. Brain 136, 2239–2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT, 2014. The intersection of amyloid beta and tau at synapses in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 82, 756–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi RH, Capetillo-Zarate E, Lin MT, Milner TA, Gouras GK, 2010. Co-occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease ß-amyloid and τ pathologies at synapses. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 1145–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H, 2002. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 58, 1791–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuri P, et al. , 2008. Antemortem MRI based STructural Abnormality iNDex (STAND)-scores correlate with postmortem Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage. Neuroimage 42, 559–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuri P, et al. , 2009. MRI and CSF biomarkers in normal, MCI, and AD subjects: predicting future clinical change. Neurology 73, 294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LC, Lynn DG, Chernoff YO, 2018. A standard model of Alzheimer’s disease? Prion 12, 261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickenmeier J, Jucker M, Goriely A, Kuhl E, 2019. A physics-based model explains the prion-like features of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 124, 264–281. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner MW, et al. , 2012. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: a review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimers Dement. 8, S1–S68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, et al. , 2008. MRI correlates of neurofibrillary tangle pathology at autopsy: a voxel-based morphometry study. Neurology 71, 743–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JW, et al. , 2016. Neuronal activity enhances tau propagation and tau pathology in vivo. Nat. Neurosci 19, 1085–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AL, et al. , 2014. A data-driven model of biomarker changes in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 137, 2564–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Gennatas ED, Kramer JH, Miller BL, Seeley WW, 2012b. Predicting regional neurodegeneration from the healthy brain functional connectome. Neuron 73, 1216–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Gennatas ED, Kramer JH, Miller BL, Seeley WW, 2012a. Predicting regional neurodegeneration from the healthy brain functional connectome. Neuron 73, 1216–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Patient data can be directly obtained from the ADNI study (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). To facilitate review, group data herein will be made available publicly and without limitations, along with the entire code repository, at our laboratory’s GitHub site: https://github.com/Raj-Lab-UCSF/Aggregation-Network-Diffusion. There are no restrictions or embargoes, subject to standard BSD3 license.

Data will be made available on request.