Abstract

A 340 nucleotide element within the 3′ untranslated region of Vg1 mRNA determines its localization to the vegetal cortex of Xenopus oocytes. To identify protein factors that bind to this region, we screened a cDNA expression library with an RNA probe containing this sequence. Five independent isolates encoded a protein (designated Prrp for proline-rich RNA binding protein) having two RNP domains followed by multiple polyproline segments. Prrp and Vg1 mRNAs are co-localized to the vegetal cortex of stage IV oocytes, substantiating an interaction between the two in vivo. Prrp also associates with VegT mRNA, which like Vg1 mRNA uses the late localization pathway, but not with Xcat-2 or Xwnt-11 mRNAs, which use the early pathway. The proline-rich domain of Prrp interacts with profilin, a protein that promotes actin polymerization. Prrp can also associate with the EVH1 domain of Mena, another microfilament-associated protein. Since the anchoring of Vg1 mRNA to the vegetal cortex is actin dependent, one function of Prrp may be to facilitate local actin polymerization, representing a novel function for an RNA binding protein.

Keywords: cytoskeleton/proline-rich motif/RNA localization/Vg1 mRNA

Introduction

One of the earliest events in Xenopus development that directly defines the body plan of the organism is the localization of certain mRNAs to discrete regions of the oocyte (Bashirullah et al., 1998; Mowry and Cote, 1999). The animal–vegetal axis determines a developmental polarity along which the primary germ layers are ultimately organized. Vg1 is a maternal mRNA that becomes localized to the vegetal cortex of the mature oocyte (Melton, 1987; Yisraeli and Melton, 1988). This RNA encodes a member of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family (Weeks and Melton, 1987) that is required for generating dorsal mesoderm at the blastula stage of Xenopus embryogenesis (Dale et al., 1993; Thomsen and Melton, 1993).

Initially, Vg1 mRNA is dispersed throughout the oocyte with movement to the vegetal hemisphere commencing at stage III (Melton, 1987); the RNA is eventually deposited in a condensed layer along the entire vegetal cortex. Experiments with cytoskeletal inhibitors indicate that this process occurs in two steps (Yisraeli et al., 1990). Translocation to the vegetal hemisphere depends on microtubules, while anchoring in the vegetal cortex involves microfilaments. The proper temporal and spatial localization of Vg1 mRNA is determined by a 340 nucleotide (nt) localization element situated within the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the mRNA (Mowry and Melton, 1992). Functionally similar cis-acting sequence elements are found in the 3′UTR of other localized mRNAs (Bashirullah et al., 1998).

Identification of the cellular factors that bind to these elements is a necessary prerequisite to delineating the process by which a particular mRNA is delivered to its proper intracellular location. UV-cross-linking experiments in Xenopus oocyte extract indicate that at least six different polypeptides can associate with the localization element of Vg1 mRNA (Mowry, 1996). Genes encoding one of these proteins, alternatively called Vg1 RBP or Vera, have been cloned independently by two groups (Deshler et al., 1998; Havin et al., 1998). Surprisingly, the Xenopus protein is homologous to chicken zipcode binding protein, which binds to and mediates localization of β-actin mRNA in fibroblasts (Ross et al., 1997). This observation suggests that the protein plays a general role in mRNA localization in different cell types. A second protein, a homolog of hnRNP I, binds to and co-localizes with Vg1 mRNA to the vegetal cortex (Cote et al., 1999). The identities of other factors that bind to the localization element of Vg1 mRNA remain to be determined. Presumably, within this group of proteins there are factors that dictate the specific localization pattern of this mRNA and that mediate interactions with components of the cytoskeleton.

We have screened a Xenopus oocyte expression library for proteins that can bind to the localization element of Vg1 and have identified a novel RNA binding protein with a unique bipartite structure consisting of two consensus RNP domains in the N-terminal half of the protein, which are followed by several polyproline sequences similar to those found in microfilament-associated proteins (Haffner et al., 1995; Gertler et al., 1996; Frazier and Field, 1997; Wasserman, 1998). The protein has been named Prrp for proline-rich RNA binding protein. The structural organization of Prrp suggests that it may serve as an adaptor that mediates association of Vg1 mRNA with a target protein. Indeed, we have determined that one of the ligands of the proline-rich domain of Prrp is profilin, a protein involved in actin assembly and organization (Schlüter et al., 1997).

Results

Identification of a novel protein that binds to the localization element of Vg1 mRNA

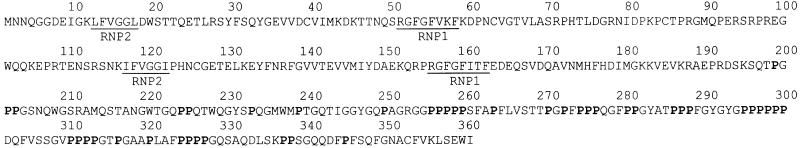

A 340 nt sequence in the 3′UTR of Vg1 mRNA, designated the Vg1 localization element (VLE), is sufficient for proper movement of the RNA to the vegetal cortex of oocytes (Mowry and Melton, 1992). A 453 nt transcript containing the VLE, labeled internally with 32P, was used to screen a Xenopus oocyte expression library for VLE binding proteins. A total of 6 × 105 plaques were screened, resulting in the identification of 21 potential positive clones. After three rounds of plaque purification, 10 clones retained the ability to bind to VLE RNA, but not to 5S rRNA. Five of the clones were independent isolates of a novel RNA binding protein (Figure 1). The open reading frame (ORF) encodes a 360-amino-acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 39 kDa. The 5′ end of the mRNA, determined using a PCR-based method (Maruyama et al., 1995), is positioned 116 nt upstream of the ORF. The predicted amino acid sequence has two RNP domains (Burd and Dreyfuss, 1994) in the N-terminal half of the protein followed by multiple polyproline segments in the second half of the protein. This latter region also has a notable preponderance of glycine and aromatic amino acid residues. The putative protein product is referred to as Prrp.

Fig. 1. The predicted amino acid sequence of Prrp. The RNP1 and RNP2 core sequences that comprise the two RNP motifs are underlined and proline residues in the C-terminal half of the protein are indicated in bold. The entire nucleotide sequence, including flanking UTRs, can be found at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AY028920.

A search of sequence databases using BLAST2 revealed that a human homolog of Prrp was recently identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for proteins that interact with DAZ, an RNA binding protein expressed in germ cells (Tsui et al., 2000a). The Xenopus and human sequences have 83% identity and 88% similarity. The significance of the interaction between the Prrp homolog and DAZ is unknown, since the exact function of the latter or the related protein DAZL (DAZ-like), which also associates with the Prrp homolog, has not been determined. There are some indications that the DAZ proteins may be involved in translational regulation (Maines and Wasserman, 1999; Tsui et al., 2000b). Interestingly, the mRNA encoding Xenopus DAZL is localized to the vegetal cortex of oocytes and remains exclusively in the germ plasm of early embryos (Houston et al., 1998). The only other significant identities to sequences in the databases are limited to the RNA binding domain of Prrp, which has considerable similarity to the A/B-type family of hnRNPs. The similarity of Prrp to this class of hnRNPs is significant because several members function in mRNA export, and shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, an activity expected for a protein involved in mRNA localization (Nakielny and Dreyfuss, 1999; Shyu and Wilkinson, 2000).

The carboxyl half of Prrp exhibits only moderate sequence identity to a variety of unrelated proline-rich proteins. In Prrp, most of the proline residues occur in consecutive repeats, which are usually flanked by a glycine residue. This distinctive sequence element is similar to the polyproline repeats found in the Ena/VASP family of cytoskeletal proteins (Gertler et al., 1996) and the FH1 domains of formin homology (FH) proteins (Frazier and Field, 1997). The polyproline sequences in these proteins bind to profilin, an actin-associated protein that regulates both the distribution and dynamics of microfilament assembly.

Prrp binds to the VLE with high affinity and specificity

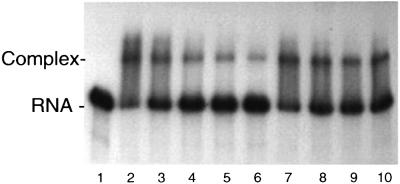

The goal of the library screen was to identify proteins that bind to the localization element of Vg1 mRNA. We have used mobility gel shift assays to measure the affinity and specificity of binding of Prrp to VLE RNA. Attempts to express sufficient amounts of full-length Prrp in Escherichia coli for RNA binding assays were not successful; however, the RNA binding domain (amino acids 1–192) could be expressed as a fusion with mal tose binding protein. The dissociation constant for the Prrp–VLE complex was estimated from the concentration of fusion protein needed to reach half-saturation in binding assays (data not shown). The apparent Kd in optimized buffer conditions is ∼1 nM. The specificity of binding was tested by incubating a constant amount of protein and radiolabeled VLE RNA with increasing concentrations of competing, unlabeled VLE RNA (Figure 2, lanes 2–6) or a similar size (355 nt) non-cognate RNA (lanes 7–10) transcribed from the plasmid pBSIISK. Unlabeled VLE RNA competes effectively for binding to Prrp, whereas >65% of the specific complex remains in the presence of a 100-fold excess of non-cognate RNA (lane 10). These assays establish that the interaction of Prrp with VLE RNA is specific and that the binding affinity is comparable to other hnRNP complexes (see for example Hall and Stump, 1992; Ashley et al., 1993; Wilson et al., 1999).

Fig. 2. Mobility shift assays for binding of Prrp to VLE RNA. Prrp (8 nM) and internally radiolabeled VLE RNA (1 nM) were incu bated with 0, 1, 5, 10 or 25 nM unlabeled VLE RNA (lanes 2–6, respectively) or 5, 25, 50 or 100 nM non-cognate RNA (lanes 7–10, respectively). Lane 1 contains VLE RNA only.

Temporal expression of Prrp during oogenesis

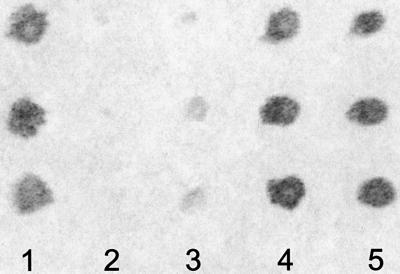

Oocytes were separated into three groups according to the Dumont stages (Dumont, 1972) and the levels of mRNA encoding Prrp were determined by northern hybridization (Figure 3A). The level of Prrp mRNA is essentially undetectable in stage I–II oocytes; however, a marked increase occurs during stage III–IV, which is maintained for the remainder of oogenesis. Thus, there is a correlation between the temporal expression of Prrp and the time at which localization of Vg1 mRNA takes place. The northern blot also allows us to compare the size of the native mRNA with that estimated from sequencing and cRACE determinations. The predicted length of the mRNA (∼2000 nt) is well matched with the size determined from the northern blot (2100 nt).

Fig. 3. Temporal expression of Prrp. (A) Oocytes were separated into three groups according to the designated Dumont stages and total RNA isolated for northern blot analysis. Each lane contains 10 oocyte equivalents of RNA. The positions of RNA size standards (nt) are indicated. (B) Staged oocytes were homogenized and two oocyte equivalents were run per lane in a western blot assay. The primary antibody is against a 22-amino-acid segment between the two RNP domains of Prrp. Lane C is a sample of Prrp expressed in E.coli and has six additional His residues at the C-terminal end of the protein.

Similarly, the levels of Prrp protein were measured in a western blot assay using antibody made against a 22-amino-acid peptide representing a region (amino acids 93–114) between the two RNP domains (Figure 3B). The amount of Prrp appears to increase gradually during oogenesis, in contrast to the sudden increase in transcription seen in the northern blot. However, the results from western blot assays were variable and there were indications that a significant portion of Prrp was being lost in a detergent-insoluble fraction of the oocyte extract. This suggests that Prrp may become associated with the cytoskeleton. Attempts to recover the protein from this fraction were not successful. Notwithstanding this shortcoming, there is no evidence that expression of Prrp is under translational control. The most important information from the western assay is the detection of two forms of Prrp. The higher mobility band in the blot migrates exactly with a sample of Prrp that was expressed in E.coli (lane C). Since only a single transcript is detected in northern blots, we presume that the slower migrating band in the western blot arises from post-translational modification of Prrp, which we are investigating.

Prrp and Vg1 mRNA are co-localized to the vegetal cortex

Despite belonging to a family of hnRNPs that move between the cytoplasm and nucleus, Prrp itself has no identifiable consensus sequences for nuclear localization or export, nor does it have any significant sequence similarity to motifs that mediate bidirectional movement, such as the M9 (Michael et al., 1995), KNS (Michael et al., 1997) or HNS (Fan and Steitz, 1998) shuttling sequences. The M9 domain, however, is not highly conserved in primary sequence; rather, it is characterized by an ∼40-amino-acid region that is rich in glycine, serine, aromatic and, to a lesser extent, glutamine residues (Siomi et al., 1998). The carboxyl half of Prrp has a notable preponderance of these same amino acids in addition to the proline repeats, suggesting that a shuttling sequence for this protein may be embedded in this domain.

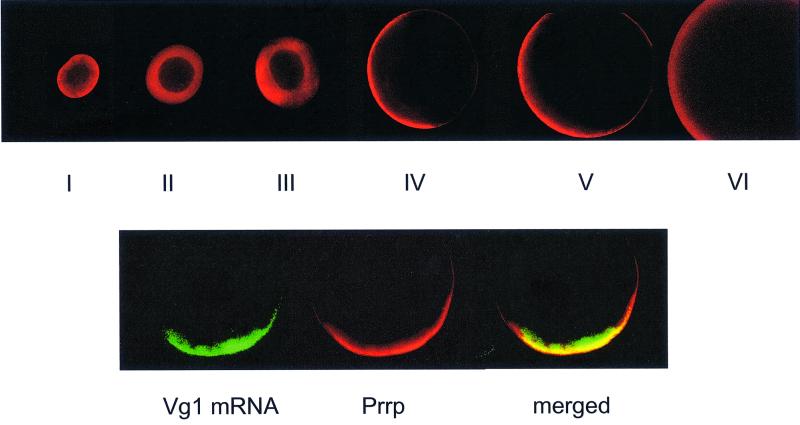

We have used confocal fluorescence microscopy to determine not only the intracellular location of Prrp during oogenesis, but also its position relative to Vg1 mRNA in stage IV oocytes (Figure 4). Prrp is present in the earliest oocytes examined, despite the insignificant amount of transcription of the gene that occurs prior to stage III. This suggests that Prrp in stage I and II oocytes is chiefly derived from the oogonium. The protein is uniformly dispersed in the cytoplasm of stage I and II oocytes with no appreciable amounts detected in the nucleus. At stage III, the protein is accumulating in the vegetal hemisphere with concomitant depletion from the animal hemisphere. By stage IV of oogenesis, the protein is located in a tight cortical band extending from the apex of the vegetal pole towards the marginal zone. It is apparent from these images that Prrp, like some other members of the hnRNP A/B family, can reside primarily in the cytoplasm.

Fig. 4. Localization of Prrp during oogenesis. Top panel: staged oocytes were processed for immunocytochemical analysis using a primary antibody prepared against a peptide derived from Prrp (amino acids 93–114) and visualization using a secondary antibody conjugated with Alex Fluor 568. In each case, the oocyte is oriented with the vegetal pole to the left. Bottom panel: stage IV oocytes were used for whole-mount in situ hybridization with an RNA probe labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-5-UTP. This was followed by immunocytochemical analysis with Prrp antibody. An optical confocal section was viewed in the green channel to detect Vg1 mRNA or in the red channel to detect Prrp. A merge of the two images demonstrates the co-localization of Prrp and Vg1 mRNA.

Because the distribution of Prrp during oogenesis is strikingly similar to that of Vg1 mRNA, we compared the location of Prrp and Vg1 mRNA directly in a double-label experiment using stage IV oocytes (Figure 4). The location of Vg1 mRNA was determined by in situ hybridization using a complementary RNA probe labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-5-UTP. The in situ hybridization was followed by immunocytochemical staining with an affinity-purified antibody prepared against Prrp. The merged confocal images demonstrate the overlapping subcellular distribution of Prrp and Vg1 mRNA at the vegetal cortex, supporting other evidence that they are associated in vivo. The localization of Prrp and Vg1 mRNA is contemporaneous; however, it was not possible, using a double-label experiment, to determine whether they move together in the same complex. The in situ hybridization procedure interferes with the subsequent immunochemical staining of cytoplasmic Prrp, greatly diminishing the fluorescent signal of the protein in early stage (II and III) oocytes. Prrp located in the oocyte cortex, on the other hand, is not affected by this treatment and stains normally.

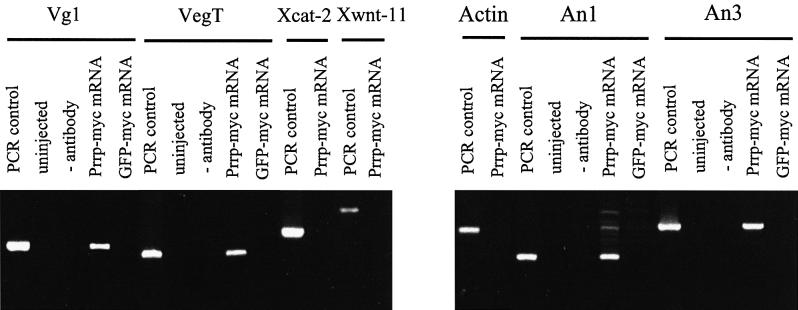

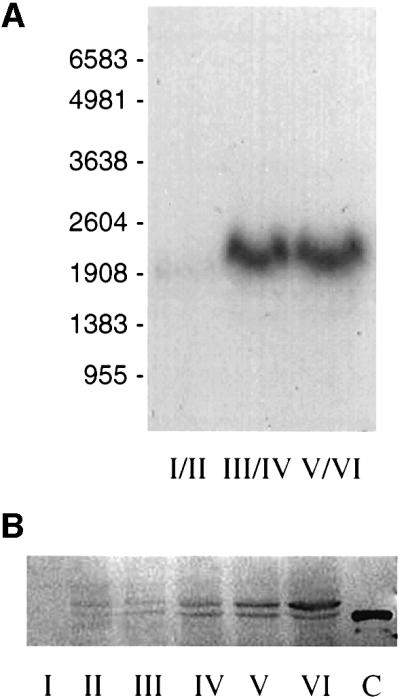

Prrp binds to RNAs localized through the late pathway

We have used an immunoprecipitation assay to examine the in vivo binding of Prrp to Vg1 mRNA and other mRNAs that are localized in Xenopus oocytes. Oocytes were injected with capped mRNA encoding Prrp carrying a myc epitope tag at its C-terminal end. Translation of injected mRNA was verified by western blot assays using anti-myc antibody (results not shown). Oocytes were kept overnight and then manually disrupted. The cell homogenate was incubated with anti-myc antibody immobilized on protein A–Sepharose. RNA specifically retained on these beads was detected by an RT–PCR assay using gene-specific primers (Figure 5). In the case of each RNA tested, a standard was generated by amplifying cDNA prepared from total oocyte RNA (lanes marked PCR control). Several control reactions were performed simultaneously to ensure that this assay was specific and free of artifactual positive results. Oocytes that were not injected with Prrp mRNA were taken through all steps of the procedure and used as a negative control (uninjected). Likewise, protein A–Sepharose beads not coated with antibody were used to control for non-specific association of RNA with the resin (– antibody). Oocytes injected with mRNA encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP), also tagged with the myc epitope, provided an additional negative control for non-specific binding of RNA to immunoprecipitated protein (GFP–myc mRNA). These assays establish that Prrp is associated with Vg1 mRNA in vivo (Figure 5, lane 4). Primers for actin mRNA, which is not localized in oocytes, gave no PCR product from the RNA co-precipitated with Prrp, indicating that the interaction with Vg1 mRNA is specific.

Fig. 5. In vivo RNA binding assays. Oocytes were injected with mRNA encoding myc-tagged Prrp. After an overnight incubation, cells were disrupted and Prrp was immunoprecipitated. Associated RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA and then amplified by PCR using the gene-specific primers denoted by the bar above the relevant lanes in order to test for the presence of the indicated mRNA. For each mRNA tested, a standard was generated using total oocyte mRNA as the template for RT–PCR (PCR control). Control reactions included uninjected oocytes (uninjected), precipitation with protein A–Sepharose resin not coupled with myc antibody (– antibody) and oocytes injected with mRNA encoding myc-tagged GFP (GFP–myc mRNA).

We tested for association of Prrp with three other mRNAs that are localized to the vegetal hemisphere of oocytes. There are at least two temporally distinct pathways for the localization of vegetal RNAs in Xenopus oocytes (Forristall et al., 1995; Kloc and Etkin, 1995). The early pathway operates during stages I and II of oogenesis, whereas the late pathway, utilized by Vg1 mRNA, is active during stages III and IV. VegT mRNA, like Vg1 mRNA, uses the late pathway for localization (Zhang and King, 1996), while Xcat-2 and Xwnt-11 use the early pathway (Kloc and Etkin, 1995). VegT mRNA also binds to Prrp, whereas the other mRNAs are not detected in the immunoprecipitate. This result indicates that Prrp can bind to mRNAs that use the late pathway for localization, but not to those that use the early pathway. Thus, despite being present in early stage oocytes, Prrp appears to function only in the late pathway for localization and may, at least in part, determine which pathway to the vegetal pole will be utilized by a particular mRNA. We also included in these assays two mRNAs, An1 and An3, that become localized to the animal hemisphere. Surprisingly, we found both associated with Prrp. Movement of mRNAs to the animal hemisphere is contemporaneous with the late pathway for vegetal localization (Perry-O’Keefe et al., 1990). The association of Prrp with RNAs that are transported to either the vegetal or animal hemispheres indicates that localization events occurring at this stage of oogenesis may share some trans-acting factors independent of the final intracellular destination of the particular RNA. This result also establishes that Prrp does not determine the direction of RNA movement. It is important to note that these assays can not be used to gauge the binding affinities of Prrp, since nothing is known about the efficiency of immunoprecipitation and it can not be assumed to be quantitative. Recovery of individual RNP complexes is likely to be influenced by several factors, including subcellular location and association with other cellular structures.

Prrp associates with profilin

Proline-rich sequences occur in a considerable number of proteins and, generally, these domains are involved in protein–protein interactions (Kay et al., 2000). The two longest polyproline sequences in Prrp are immediately preceded by a glycine residue, as are many of the shorter ones. A repeated G(P)5 sequence is present in the phosphoprotein VASP, which was the first identified ligand of profilin (Reinhard et al., 1995). Similar sequence motifs are also present in Ena (Ahern-Djamali et al., 1999), Mena (Gertler et al., 1996) and the FH proteins (Frazier and Field, 1997; Wasserman, 1998), which also associate with profilin. Profilin binds actin monomers and appears to regulate microfilament assembly (Schlüter et al., 1997). Of particular importance here is the observation that the attachment of Vg1 mRNA to the vegetal cortex appears to be actin dependent (Yisraeli et al., 1990); indeed, the movement and anchoring of several mRNAs require actin microfilaments (Sundell and Singer, 1991; Erdelyi et al., 1995; Bassell and Singer, 1997; Long et al., 1997).

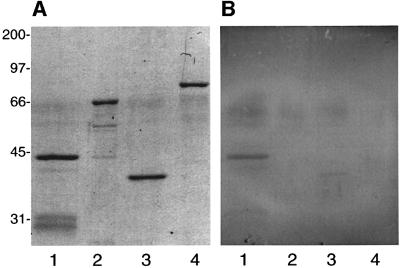

In order to determine whether Prrp associates with profilin, we first set up a blot overlay assay (Figure 6). We have succeeded in expressing small amounts of full-length Prrp with a C-terminal His tag, which was used in this assay. This sample, along with other controls, was run on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to a nitrocellulose filter. The filter was incubated with Xenopus profilin that was expressed in bacteria from a clone prepared by RT–PCR using sequence information (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AW767227) from the Xenopus EST Project (Washington University). Profilin bound to the filter was detected in a colorimetric assay using antibody prepared against the Xenopus protein. A distinct signal is seen for full-length Prrp (Figure 6B, lane 1), but not for a fusion protein containing only the N-terminal RNA binding domain (lane 2). An unrelated fusion protein carrying a His tag (lane 3) exhibits an extremely weak band in the overlay, eliminating the possibility that profilin is binding to Prrp through the His sequence tag. These results establish that profilin can bind to the proline-rich domain of Prrp.

Fig. 6. The proline-rich domain of Prrp interacts with profilin. Protein samples separated on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel (A) were transferred to a nitrocellulose filter that was incubated in a solution containing 1 µM Xenopus profilin. Profilin that remained associated with the filter after washing was detected by a colorimetric immunochemical assay (B). Lane 1, full-length Prrp with a C-terminal His tag; lane 2, RNA binding domain of Prrp fused to maltose binding domain; lane 3, ribosomal protein L5 with a C-terminal His tag; lane 4, L5 fused to maltose binding protein. (C) A colony-lift filter assay was used to measure interactions between the designated bait–prey combinations in a yeast two-hybrid system. Each column represents three independently selected colonies. 1, positive control (p53/T antigen); 2, Prrp/Xenopus profilin; 3, C-terminal (proline-rich) domain of Prrp/Xenopus profilin; 4, negative control (lamC/T antigen); 5, N-terminal (RNA binding) domain of Prrp/Xenopus profilin; 6, Prrp/prey vector; 7, bait vector/Xenopus profilin; 8, Prrp/yeast profilin.

The interaction between Prrp and profilin was verified using a yeast two-hybrid assay (Chien et al., 1991). The complete ORF of Prrp was cloned into the bait vector pGBKT7. The N-terminal (residues 1–251) and C-terminal (residues 242–360) regions of Prrp, containing the RNA binding domain and the proline-rich domain, respectively, were also cloned into the bait vector. Expression of these proteins was confirmed by western blot assays (data not shown). Xenopus profilin and yeast profilin genes were cloned into the prey vector pGADT7. Interactions were measured by a colony-lift filter assay using X-gal as the substrate for β-galactosidase expressed under the control of a GAL4 upstream activating sequence (Figure 6C). A strong signal is observed for the bait–prey combinations of Prrp with either Xenopus (lane 2) or yeast (lane 8) profilins. When just the proline-rich domain of Prrp is expressed as bait, a nearly equally positive response is observed (lane 3), whereas there is no evidence for an interaction between the RNA binding domain of Prrp and profilin (lane 5). These assays are fully consistent with the blot overlay experiment and establish an interaction between the proline-rich domain of Prrp and profilin.

The SH3, WW and EVH1 domains are discrete structures that also bind polyproline sequences (Kay et al., 2000). The family of SH3 proteins is large, and while members bind a core proline-rich sequence, phage display experiments have demonstrated that SH3 domains from different proteins recognize distinct consensus sequences (Rickles et al., 1995; Sparks et al., 1996). At this time, proteins containing WW domains appear to fall into five groups based upon binding specificity for proline-containing sequences. The EVH1 domain was first identified in two murine proteins, Mena and Evl, which are related to VASP (Gertler et al., 1996). The EVH1 domain targets the sequence FPPPP and showed no significant interaction with any of 65 peptides representing different SH3 ligands nor with peptides representing five known WW domain ligands (Niebuhr et al., 1997). Thus, the EVH1 domain is exceptionally specific for the core FPPPP sequence, which apparently is not found in the core sequences targeted by these two other domains.

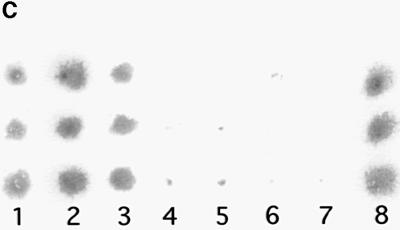

We have tested the interactions between the proline-rich domain of Prrp and representative SH3, WW and EVH1 domains using the yeast two-hybrid assay. Cells harboring bait plasmid and prey plasmids carrying each of the domains survived nutritional selection, indicating some degree of interaction between the respective proteins. It should be noted, however, that in each case the number of transformants was small and they grew slowly, which may reflect the modest affinity that typifies the interaction of these domains with their polyproline ligands. Several colonies for each bait–prey combination were taken for a colony-lift assay to gauge the relative strength of the association of Prrp with the different domains (Figure 7). Of the ligands tested, the combination of profilin with the proline-rich domain of Prrp exhibited the highest levels of β-galactosidase activity (lane 5). However, the EVH1 domain of Mena appears to bind with an affinity comparable to profilin (lane 4). The sequence FPPPP, specifically targeted by EVH1 domains, is found at amino acids 322–326 in Prrp, although the flanking acidic amino acids of the consensus sequence recognized by the EVH1 domain are neutral amino acids (alanine and glutamine) in the Prrp sequence. The SH3 domain of Abl also appears to have some affinity for Prrp, albeit modest (lane 3). Interestingly, Abl binds to the proline-rich sequences found in formin proteins (Ren et al., 1993) and to Ena (Gertler et al., 1995), which also bind to profilin. So the ability of Prrp to interact with profilin as well as the Abl SH3 domain parallels the behavior of other proteins having related proline-rich sequences. The WW domain from YAP65 recognizes the consensus core sequence PPXY (Bedford et al., 1997), which is present at amino acid residues 281–284 (PPGY). This domain does not have any detectable affinity for Prrp (lane 2).

Fig. 7. The interaction of Prrp with other polyproline binding domains. A colony-lift assay was used to measure the interaction between the C-terminal (proline-rich) domain of Prrp and the designated prey. Each column contains three independently selected colonies. 1, positive control (p53/T antigen); 2, WW domain of YAP; 3, SH3 domain of Abl; 4, EVH1 domain of Mena; 5, Xenopus profilin.

Discussion

There is appreciable evidence that mRNAs transported to distinct intracellular locations are associated with multiple protein factors (Ferrandon et al., 1994; Schroeder and Yost, 1996; Long et al., 1997; Hoek et al., 1998; Shen et al., 1998; Wilhelm et al., 2000). In the case of Vg1 mRNA, there are six polypeptides that become cross-linked to the VLE upon UV irradiation (designated according to their molecular masses as p78, p69, p60, p40, p36 and p33) (Mowry, 1996). This probably represents a minimum estimate of the number of trans-acting factors that associate with this element, since some proteins do not cross-link efficiently to nucleic acids, other proteins undoubtedly assemble into the complex through protein–protein interactions, and the composition of a multi-subunit complex on the VLE is likely to be dynamic with certain factors being replaced by others during translocation and anchoring. Two of the cross-linked proteins have been identified. Vera/Vg1 RBP corresponds to p69 (Deshler et al., 1998; Havin et al., 1998); this protein is a homolog of zipcode binding protein, which was first identified in fibroblasts and binds to the localization element of β-actin mRNA (Ross et al., 1997). More recently, the identity of p60 was determined; it is a homolog of human hnRNP I and is referred to as VgRBP60 (Cote et al., 1999). Both of these proteins co-localize with Vg1 mRNA in oocytes (Cote et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 1999) and mutations that specifically disrupt binding of either protein also interfere with proper localization of the RNA (Havin et al., 1998; Cote et al., 1999). Although Vera/Vg1 RBP appears to promote association of Vg1 mRNA with microtubules (Elisha et al., 1995) and is itself associated with a subcompartment of the endoplasmic reticulum (Deshler et al., 1997), the actual role of the protein in Vg1 mRNA localization remains to be determined. Likewise, the function of VgRBP60 is unknown. Before a detailed molecular description of Vg1 mRNA localization is realized, it will be necessary to identify the remaining trans-acting factors that participate in this process and deduce their individual functions.

We have identified a protein with a distinctive structure that may reflect a novel function for an RNA binding protein. The N-terminal half of Prrp contains two RNP domains that show an overall organization and sequence similarity to A/B-type hnRNPs. Several members of this family shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm, a property common to the first few RNA localization factors that have been identified (Shyu and Wilkinson, 2000). In the case at hand, Vera/Vg1 RBP contains both nuclear localization and nuclear export sequences (Deshler et al., 1998), and VgRBP60, despite having a putative bipartite nuclear localization element, accumulates in the vegetal cytoplasm with Vg1 mRNA (Cote et al., 1999). Confocal microscopy reveals that Prrp is largely cytoplasmic at all stages of oogenesis. Prrp has no identifiable nuclear localization element, so it will be important to determine whether this protein, in fact, spends any time in the nucleus.

Although the northern blot assay shows that a pronounced increase in transcription of the genes encoding Prrp coincides with the activation of the late pathway for RNA localization at stage III, the immunocytochemical images reveal that the protein is present in the cytoplasm of stage I and II oocytes. It is possible that the observed transcriptional activation is needed because the amount of Prrp in early stage oocytes is not sufficient to support the localization of all the Vg1 mRNA that accumulates by stage IV. Notwithstanding this point, the simple presence or absence of Prrp does not seem to control the temporal localization of Vg1 mRNA. Whether a post-translational modification of Prrp, suggested by the western blot, regulates its activity is an important issue that will be investigated. Otherwise, some other factor(s) must regulate the activation of the late pathway.

We have found that Prrp also binds to mRNAs localized to the animal hemisphere. This was somewhat surprising, since the final distribution of these RNAs, in the few cases that have been examined, is different from the tight cortical location of Vg1 mRNA. In situ hybridization experiments have revealed an increasing gradient of An2 and An3 mRNAs towards the animal pole of stage VI oocytes, but not the cortical localization exhibited by Vg1 mRNA (Perry-O’Keefe et al., 1990). The mRNA encoding poly(A) binding protein, which also accumulates in the animal hemisphere, has a more restricted distribution pattern occupying a region just under, but not including, the cortex of the animal cap (Schroeder and Yost, 1996). Neither of these patterns matches those seen in the confocal images of late stage oocytes stained with Prrp antibody. Some small amount of Prrp may be located in the animal cortex, but any protein in the cytoplasm of the animal hemisphere is not detected by this method. However, the immunocytochemical results must be interpreted with caution. For example, while whole-mount in situ hybridization shows a high concentration of nanos mRNA at the posterior pole of early Drosophila embryos, this localized RNA actually represents only a small percentage (∼4%) of the total (Bergsten and Gavis, 1999). Thus, the presence of Prrp in the animal hemisphere of stage IV oocytes can not be excluded on the basis of the immunocytochemical studies. The ability of Prrp to bind to RNAs that are transported in opposite directions finds a precedent in the Drosophila protein Staufen, which binds to and co-localizes with bicoid mRNA at the anterior pole and oskar mRNA at the posterior pole of early embryos (St Johnston et al., 1991). What the confocal images do establish is that Prrp becomes concentrated in the vegetal cortex of stage IV oocytes and that its distribution clearly overlaps that of Vg1 mRNA. Significantly, movement of mRNAs into the animal hemisphere is contemporaneous with the late pathway for vegetal localization.

The most intriguing feature of Prrp is the ability of the proline-rich domain to interact with profilin and potentially with a member of the Ena/VASP family. Although this region has no extensive sequence similarity to other known proteins, several of the polyproline repeats in Prrp are immediately flanked by a glycine residue, a signature analogous to the polyproline sequences found in VASP (Reinhard et al., 1995), Ena (Ahern-Djamali et al., 1999), Mena (Gertler et al., 1996) and the FH proteins (Frazier and Field, 1997; Wasserman, 1998). These proteins are involved in the local organization of the actin cytoskeleton, and the core GPPPPP sequences in each serve as a ligand for profilin. Profilin, in turn, binds actin monomers through a separate site and appears to accelerate polymerization, perhaps by functioning as a nucleotide exchange factor (Goldschmidt-Clermont et al., 1992; Blanchoin and Pollard, 1998; Wolven et al., 2000) and/or by promoting monomer addition to the growing barbed ends of actin filaments (Pantaloni and Carlier, 1993; Kang et al., 1999).

The Ena/VASP family of proteins and the FH proteins are found at sites of rapid formation of actin filaments, such as focal adhesions, cellular outgrowths, cortical patches, cleavage furrows and sites of membrane ruffling (for reviews see Frazier and Field, 1997; Schlüter et al., 1997; Beckerle, 1998; Wasserman, 1998). Actin filament assembly appears to follow site selection and the Ena/VASP and FH proteins have been implicated in this process, acting as organizers, in part, through their ability to recruit profilin-bound actin. Like Prrp, these proteins have modular structures that contain distinct domains, which bring together several activities that promote the local formation of actin microfilaments (Golsteyn et al., 1997; Beckerle, 1998; Laurent et al., 1999). One of the best-characterized FH proteins is yeast Bni1p, which is required for proper organization of cortical actin patches during cytokinesis and cell polarization (Evangelista et al., 1997). As is the case with Prrp, the proline-rich domain of Bni1p associates with more than one ligand involved in actin assembly. Bni1p is encoded by She5, one of five genes required for localization of Ash1 mRNA to the bud tip of daughter cells during cell division. In yeast cells lacking Bni1p/She5p, Ash1 mRNA is transported to the bud cell, but is not anchored in the cortical cap (Beach et al., 1999). It is possible to speculate, by comparison with these examples, that the localized RNP complex containing Vg1 mRNA promotes local formation of actin structures. The role of Prrp, like the Ena/VASP or FH proteins, would be to assist in the recruitment of profilin–actin for the rapid assembly of the filaments that anchor and move the Vg1 RNP along the vegetal cortex.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and nucleic acids

The plasmid pBSVg1-B, which contains the complete VLE (nt 1440–1816) (Mowry and Melton, 1992), was constructed by inserting the 376 bp MscI–SspI restriction fragment of pGEM3 Vg1.1 into the SmaI site of pBluescript II SK. Recombinant λgt22A phage selected in the screen of the expression library were digested with SalI and NotI, and the released fragments were inserted into the same sites of pGEMEX-1 (Promega). The plasmid pMAL-c-λ21PD was constructed for the expression of a maltose binding protein fusion that contains the first 192 amino acids of Prrp. The coding sequences of Prrp and GFP were cloned into the vector pCS3+MT, which was supplied by Dr D.L.Turner (University of Michigan). The ORFs were cloned such that each contained six repeated myc epitopes at the C-terminal end of the expressed protein. The plasmid vectors used in the yeast two-hybrid assays, pGBKT7 (bait vector) and pGADT7 (prey vector), were obtained from Clontech. Dr P.Leder (Harvard University) provided the plasmids pGST-YAPWW and pGST-AblSH3, which contain the WW domain of YAP and the SH3 domain of Abl, respectively. Dr F.B.Gertler (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) provided a clone of Mena (pBS-KSII-Mena) and Dr S.C.Almo (Albert Einstein College of Medicine) clones of human and yeast profilin.

The 453 nt RNA used to screen the Xenopus oocyte expression library was synthesized in vitro using pBSVg1-B linearized with BamHI as the template for transcription by T7 RNA polymerase (Milligan and Uhlenbeck, 1989). This RNA was also used in mobility shift assays to test binding of purified proteins to the VLE. Non-specific RNA (355 nt) used as competitor in binding assays was synthesized by run-off transcription of pBSIISK(+) digested with PvuII using T7 RNA polymerase. The 32P-labeled probe for the northern blot assay was prepared from the SalI–NotI fragment of the Prrp cDNA clone using the DECAprime II Random Priming DNA Labeling Kit (Ambion). Capped mRNA encoding myc-tagged Prrp for microinjection experiments was prepared by run-off transcription of plasmid linearized with NotI using SP6 RNA polymerase (Turner and Weintraub, 1994).

Library screen

The λgt22A cDNA expression library, prepared from Xenopus laevis immature ovary tissue, was kindly provided by Dr W.L.Taylor (University of Tennessee). The library was screened for binding to a 453 nt RNA fragment that contains the VLE following the strategy developed by Singh et al. (1988) for the identification of DNA binding proteins, with some modifications. After renaturation of immobilized protein by the stepwise removal of guanidine–HCl, the nitrocellulose filters were kept in Denhardt’s solution made in RNA binding buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)] for 1 h at room temperature. The filters were rinsed with RNA binding buffer and then incubated with the radiolabeled VLE probe (2 × 105 c.p.m./ml) in binding buffer containing 0.1 mg/ml renatured tRNA and 10 U/ml RNasin (Promega) for 1 h at room temperature. The filters were washed four times with binding buffer, air dried, and then exposed to X-ray film at –75°C. Preparation of phage stocks (Sambrook et al., 1989) and purification of phage DNA (Bothwell et al., 1990) followed published procedures.

DNA sequence analysis

Phage DNA was purified (Bothwell et al., 1990) and the 5′ sequence (∼150 bp) of each positive clone determined using the fmol DNA Sequencing System (Promega). The complete inserts of selected phage were subcloned into pGEMEX-1 (using SalI and NotI restriction sites) for automated sequence determination at the DNA Sequencing and Synthesis Facility (Iowa State University). DNA and protein sequences were compared to available sequence databases using BLAST programs available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The complete 5′ end sequence of Prrp mRNA was determined using the cRACE method described by Maruyama et al. (1995).

Cloning and expression of Xenopus profilin

The sequence of Xenopus profilin (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AW767227) was obtained from the Xenopus EST project (Washington University). Oligonucleotide primers were designed for RT–PCR in order to amplify the coding region starting from a sample of total RNA prepared from oocytes. The appropriate DNA fragment generated by this procedure was digested with NdeI and EcoRI, and cloned into pET-23b (Novagen). Profilin was expressed in E.coli strain BL21(DE3) and purified according to the procedure described for human profilin (Fedorov et al., 1994).

Antibody

Antiserum was prepared against a peptide derived from a region between the RNP domains (residues 93–114) of Prrp using a protocol described by Sheibani and Frazier (1998). The peptide had six His residues at its N-terminal end, which were used to attach the peptide to Ni-NTA–agarose (Qiagen). Approximately 200 µg of peptide were incubated with 100 µl of Ni-NTA–agarose in phosphate-buffered saline, mixed with adjuvant, and injected at multiple sites following standard protocols. Antiserum prepared against the peptide from the RNP region of Prrp was purified by affinity chromatography. A fusion protein containing the first 192 amino acids of Prrp (10 mg) was coupled to an NHS-activated HiTrap column (1 ml) (Amersham Pharmacia) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum (12 ml) was applied to the column and bound antibody was eluted as described (Harlow and Lane, 1988). Xenopus profilin expressed in bacteria was used to prepare polyclonal antiserum from rabbit using a standard regime of injections of the purified protein.

In situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry

Combined in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry was performed as described by Cote et al. (1999). An antisense Vg1 RNA probe labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-5-UTP (Molecular Probes) was synthesized by run-off transcription of pSP70Vg1 (provided by G.H.Thomsen, SUNY Stony Brook) linearized with HindIII using T7 RNA polymerase. The RNA was partially hydrolyzed by incubation in bicarbonate buffer prior to use (Kloc and Etkin, 1999). Affinity-purified antibody prepared against amino acid residues 93–114 of Prrp was used for immunocytochemistry. The secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes). A Bio-Rad MRC 1024 scanning confocal system attached to a Nikon Diaphot 200 inverted microscope was used to collect images of stained oocytes.

VLE binding assay

Binding reactions (10 µl) contained the indicated amount of fusion protein, 1 nM of 32P-labeled VLE RNA and the indicated amount of unlabeled competitor RNA. The binding buffer, optimized empirically for Prrp, contained 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.2 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 0.2 mg/ml heparin and 4 U RNasin (Promega). The reactions were incubated for 90 min on ice and then loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel (5% acrylamide/0.125% bisacrylamide, 50 mM Tris borate pH 8.3, 1 mM EDTA). Gels were run at 250 V for 30 min prior to loading the samples and electrophoresis proceeded at the same voltage at room temperature.

RNA isolation and northern blot analysis

Oocytes were manually dissected from ovary tissue and staged according to Dumont (1972). RNA was isolated (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987) and treated with 0.1 U/µl RQ1 RNase-free DNase I (Promega) at 37°C for 30 min, followed by 200 ng/µl proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim) and incubated for an additional 30 min. The RNA samples (10 oocyte equivalents each) were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde and transferred to a GeneScreen membrane (NEN). Pre-hybridization was carried out at 65°C for 4 h in hybridization buffer (10% w/v dextran sulfate, 7% SDS, 1.5× SSPE). Radiolabeled probe DNA (106 c.p.m./ml hybridization solution) was incubated with the filter overnight at 65°C. The filter was then washed with 1× SSC containing 0.1% SDS at room temperature for 10 min, followed by a second wash at 65°C for 30 min. The dried filter was exposed to X-ray film at –80°C.

In vivo RNA binding assays

Stage V oocytes were isolated from Xenopus ovaries and placed in OR2 buffer (5 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 82.5 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM Na2HPO4). Oocytes were injected with 5 nl of capped mRNA (0.36 ng/nl) encoding Prrp with six myc epitopes at the C-terminal end (Turner and Weintraub, 1994) and kept in OR2 buffer overnight at 19°C. Ten oocytes were homogenized in 100 µl of NET-2 buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% NP-40) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 µg/ml pepstatin and 0.2 U/µl RNasin (Promega). The homogenate was cleared by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge for 3 min. Protein A–Sepharose (7.5 mg) was incubated with (3 µg) myc monoclonal antibody (c-myc oncoprotein Ab-2/clone 9E10.3; Lab Vision Corp.) in NET-2 buffer for 2 h at 4°C. The resin was collected by low speed centrifugation and washed twice with buffer to remove unbound antibody. The homogenate was mixed with antibody-coated Sepharose resin and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. The resin was washed six times with NET-2 buffer by low speed centrifugation and suspended in a final volume of 50 µl. SDS was added to a final concentration of 2%. The sample was then vortexed, extracted sequentially with phenol:chloroform and chloroform, and nucleic acid in the aqueous phase precipitated with ethanol. The pellet was dissolved in water and used as a template for synthesis of cDNA in a reaction that contained 200 U of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) and 250 ng of random hexamer primers (Promega). A 2 µl aliquot of this reaction was taken for PCR amplification using 20 pmol of primers specific for the gene being tested and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Fisher). The products of the PCR amplification were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel alongside standards generated by amplification of cDNA prepared from total oocyte RNA.

Blot overlay assay

Proteins displayed on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel were transferred to nitrocellulose (0.45 µm; Osmonics). The filter was blocked by incubation overnight at 4°C in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The filter was then incubated with 1 µM Xenopus profilin in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl containing 0.5% BSA for 12 h at 4°C. The filter was washed in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) three times for 5 min. Profilin that remained bound to the nitrocellulose filter was detected using rabbit anti-profilin antiserum and standard western blotting reagents.

Yeast two-hybrid assays

Matchmaker Two-Hybrid System 3 was purchased from Clontech Laboratories. Several of the plasmids used in these assays were constructed from DNA fragments generated by PCR amplification. The host strain for these assays was AH109, which has three reporter genes under the control of GAL4-responsive elements (HIS3, ADE2, lacZ). The recombinant bait plasmid carrying Prrp exhibited no autonomous activation of the reporter genes on its own. Because the bait plasmid carrying Prrp slows the growth rate of the host cells, the bait and prey vectors were used together to transform cells. The transformation mixtures were spread on plates containing synthetic drop-out (SD) medium lacking adenine, histidine, leucine and tryptophan, and kept at 30°C for 4–5 days. Individual colonies that arose were spotted onto a second SD plate and, after sufficient growth, β-galactosidase activity was measured using a colony-lift filter assay (Breeden and Nasmyth, 1985).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are especially indebted to Drs K.L.Mowry and D.L.Weeks for advice, instruction in techniques, and many helpful discussions that were essential to the completion of this work. We thank Dr W.L.Taylor for providing the cDNA library; Drs D.L.Weeks, G.H.Thomsen, D.L.Turner, P.Leder, F.B.Gertler and S.C.Almo for supplying plasmids; K.Stewart and V.Schroeder for assistance with the animals and W.Archer of the Optical Facility (UND). D.L.Weeks, K.L.Mowry, I.G.Wool and D.J.Fishkind provided helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ahern-Djamali S.M., Bachmann,C., Hua,P., Reddy,S.K., Kastenmeier, A.S., Walter,U. and Hoffmann,F.M. (1999) Identification of profilin and src homology 3 domains as binding partners for Drosophila enabled. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 4977–4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley C.T. Jr, Wilkinson,K.D., Reines,D. and Warren,S.T. (1993) FMR1 protein: conserved RNP family domains and selective RNA binding. Science, 262, 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashirullah A., Cooperstock,R.L. and Lipshitz,H.D. (1998) RNA localization in development. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 67, 335–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell G. and Singer,R.H. (1997) mRNA and cytoskeletal filaments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 9, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach D.L., Salmon,E.D. and Bloom,K. (1999) Localization and anchoring of mRNA in budding yeast. Curr. Biol., 9, 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckerle M.C. (1998) Spatial control of actin filament assembly: lessons from Listeria. Cell, 95, 741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford M.T., Chan,D.C. and Leder,P. (1997) FBP WW domains and the Abl SH3 domain bind to a specific class of proline-rich ligands. EMBO J., 16, 2376–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten S.E. and Gavis,E.R. (1999) Role for mRNA localization in translational activation but not spatial restriction of nanos RNA. Development, 126, 659–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchoin L. and Pollard,T.D. (1998) Interaction of actin monomers with Acanthamoeba actophorin (ADF/cofilin) and profilin. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 25106–25111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothwell A., Yancopoulos,G.D. and Alt,F.W. (1990) Methods for Cloning and Analysis of Eukaryotic Genes. Jones and Bartlett, Boston, MA, pp. 82–83.

- Breeden L. and Nasmyth,K. (1985) Regulation of the yeast HO gene. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 50, 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd C.G. and Dreyfuss,G. (1994) Conserved structures and diversity of functions of RNA-binding proteins. Science, 265, 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien C.T., Bartel,P.L., Sternglanz,R. and Fields,S. (1991) The two-hybrid system: a method to identify and clone genes for proteins that interact with a protein of interest. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 9578–9582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P. and Sacchi,N. (1987) Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem., 162, 156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote C.A., Gautreau,D., Denegre,J.M., Kress,T.L., Terry,N.A. and Mowry,K.L. (1999) A Xenopus protein related to hnRNP I has a role in cytoplasmic RNA localization. Mol. Cell, 4, 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale L., Matthews,G. and Colman,A. (1993) Secretion and mesoderm-inducing activity of the TGF-β-related domain of Xenopus Vg1. EMBO J., 12, 4471–4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshler J.O., Highett,M.I. and Schnapp,B.J. (1997) Localization of Xenopus Vg1 mRNA by Vera protein and the endoplasmic reticulum. Science, 276, 1128–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshler J.O., Highett,M.I., Abramson,T. and Schnapp,B.J. (1998) A highly conserved RNA-binding protein for cytoplasmic mRNA localization in vertebrates. Curr. Biol., 8, 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont J.N. (1972) Oogenesis in Xenopus laevis (Daudin) I. Stages of oocyte development in laboratory maintained animals. J. Morph., 136, 153–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisha Z., Havin,L., Ringel,I. and Yisraeli,J.K. (1995) Vg1 RNA binding protein mediates the association of Vg1 RNA with microtubules in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 14, 5109–5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdelyi M., Michon,A.M., Guichet,A., Glotzer,J.B. and Ephrussi,A. (1995) Requirement for Drosophila cytoplasmic tropomyosin in oskar mRNA localization. Nature, 377, 524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista M., Blundell,K., Longtine,M.S., Chow,C.J., Adames,N., Pringle,J.R., Peter,M. and Boone,C. (1997) Bni1p, a yeast formin linking cdc42p and the actin cytoskeleton during polarized morphogenesis. Science, 276, 118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X.C. and Steitz,J.A. (1998) HNS, a nuclear–cytoplasmic shuttling sequence in HuR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 15293–15298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov A.A., Pollard,T.D. and Almo,S.C. (1994) Purification, characterization and crystallization of human platelet profilin expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 241, 480–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon D., Elphick,L., Nusslein-Volhard,C. and St Johnston,D. (1994) Staufen protein associates with the 3′UTR of bicoid mRNA to form particles that move in a microtubule-dependent manner. Cell, 79, 1221–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forristall C., Pondel,M., Chen,L. and King,M.L. (1995) Patterns of localization and cytoskeletal association of two vegetally localized RNAs, Vg1 and Xcat-2. Development, 121, 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier J.A. and Field,C.M. (1997) Actin cytoskeleton: are FH proteins local organizers? Curr. Biol., 7, R414–R417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertler F.B., Comer,A.R., Juang,J.L., Ahern,S.M., Clark,M.J., Liebl,E.C. and Hoffmann,F.M. (1995) enabled, a dosage-sensitive suppressor of mutations in the Drosophila Abl tyrosine kinase, encodes an Abl substrate with SH3 domain-binding properties. Genes Dev., 9, 521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertler F.B., Niebuhr,K., Reinhard,M., Wehland,J. and Soriano,P. (1996) Mena, a relative of VASP and Drosophila Enabled, is implicated in the control of microfilament dynamics. Cell, 87, 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt-Clermont P.J., Furman,M.I., Wachsstock,D., Safer,D., Nachmias,V.T. and Pollard,T.D. (1992) The control of actin nucleotide exchange by thymosin β4 and profilin. A potential regulatory mechanism for actin polymerization in cells. Mol. Biol. Cell, 3, 1015–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golsteyn R.M., Beckerle,M.C., Koay,T. and Friederich,E. (1997) Structural and functional similarities between the human cytoskeletal protein zyxin and the ActA protein of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Cell Sci., 110, 1893–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner C., Jarchau,T., Reinhard,M., Hoppe,J., Lohmann,S.M. and Walter,U. (1995) Molecular cloning, structural analysis and functional expression of the proline-rich focal adhesion and micro filament-associated protein VASP. EMBO J., 14, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall K.B. and Stump,W.T. (1992) Interaction of N-terminal domain of U1A protein with an RNA stem/loop. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 4283–4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E. and Lane,D. (1988) Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Havin L., Git,A., Elisha,Z., Oberman,F., Yaniv,K., Schwartz,S.P., Standart,N. and Yisraeli,J.K. (1998) RNA-binding protein conserved in both microtubule- and microfilament-based RNA localization. Genes Dev., 12, 1593–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek K.S., Kidd,G.J., Carson,J.H. and Smith,R. (1998) hnRNP A2 selectively binds the cytoplasmic transport sequence of myelin basic protein mRNA. Biochemistry, 37, 7021–7029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston D.W., Zhang,J., Maines,J.Z., Wasserman,S.A. and King,M.L. (1998) A Xenopus DAZ-like gene encodes an RNA component of germ plasm and is a functional homologue of Drosophila boule. Development, 125, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang F., Purich,D.L. and Southwick,F.S. (1999) Profilin promotes barbed-end actin filament assembly without lowering the critical concentration. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 36963–36972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay B.K., Williamson,M.P. and Sudol,M. (2000) The importance of being proline: the interaction of proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins with their cognate domains. FASEB J., 14, 231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc M. and Etkin,L.D. (1995) Two distinct pathways for the localization of RNAs at the vegetal cortex in Xenopus oocytes. Development, 121, 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc M. and Etkin,L.D. (1999) Analysis of localized RNAs in Xenopus oocytes. In Richter,J.D. (ed.), A Comparative Methods Approach to the Study of Oocytes and Embryos. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 256–278.

- Laurent V., Loisel,T.P., Harbeck,B., Wehman,A., Grobe,L., Jockusch, B.M., Wehland,J., Gertler,F.B. and Carlier,M.F. (1999) Role of proteins of the Ena/VASP family in actin-based motility of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Cell Biol., 144, 1245–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long R.M., Singer,R.H., Meng,X., Gonzalez,I., Nasmyth,K. and Jansen,R.-P. (1997) Mating type switching in yeast controlled by asymmetric localization of ASH1 mRNA. Science, 277, 383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines J.Z. and Wasserman,S.A. (1999) Post-transcriptional regulation of the meiotic Cdc25 protein Twine by the Dazl orthologue Boule. Nature Cell Biol., 1, 171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama I.N., Rakow,T.L. and Maruyama,H.I. (1995) cRACE: a simple method for identification of the 5′ end of mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 3796–3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton D.A. (1987) Translocation of a localized maternal mRNA to the vegetal pole of Xenopus oocytes. Nature, 328, 80–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael W.M., Choi,M. and Dreyfuss,G. (1995) A nuclear export signal in hnRNP A1: a signal-mediated, temperature-dependent nuclear protein export pathway. Cell, 83, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael W.M., Eder,P.S. and Dreyfuss,G. (1997) The K nuclear shuttling domain: a novel signal for nuclear import and nuclear export in the hnRNP K protein. EMBO J., 16, 3587–3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan J.F. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (1989) Synthesis of small RNAs using T7 RNA polymerase. Methods Enzymol., 180, 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowry K.L. (1996) Complex formation between stage-specific oocyte factors and a Xenopus mRNA localization element. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 14608–14613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowry K.L. and Cote,C.A. (1999) RNA sorting in Xenopus oocytes and embryos. FASEB J., 13, 435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowry K.L. and Melton,D.A. (1992) Vegetal messenger RNA localization directed by a 340-nt RNA sequence element in Xenopus oocytes. Science, 255, 991–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakielny S. and Dreyfuss,G. (1999) Transport of proteins and RNAs in and out of the nucleus. Cell, 99, 677–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr K. et al. (1997) A novel proline-rich motif present in ActA of Listeria monocytogenes and cytoskeletal proteins is the ligand for the EVH1 domain, a protein module present in the Ena/VASP family. EMBO J., 16, 5433–5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaloni D. and Carlier,M.F. (1993) How profilin promotes actin filament assembly in the presence of thymosin β4. Cell, 75, 1007–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry-O’Keefe H., Kinter,C.R., Yisraeli,J. and Melton,D.A. (1990) The use of in situ hybridisation to study the localisation of maternal mRNAs during Xenopus oogenesis. In Harris,N. and Wilkinson,D.G. (eds), In Situ Hybridisation: Application to Developmental Biology and Medicine, Vol. 40. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 115–130.

- Reinhard M., Giehl,K., Abel,K., Haffner,C., Jarchau,T., Hoppe,V., Jockusch,B.M. and Walter,U. (1995) The proline-rich focal adhesion and microfilament protein VASP is a ligand for profilins. EMBO J., 14, 1583–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren R., Mayer,B.J., Cicchetti,P. and Baltimore,D. (1993) Identification of a ten-amino acid proline-rich SH3 binding site. Science, 259, 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickles R.J., Botfield,M.C., Zhou,X.M., Henry,P.A., Brugge,J.S. and Zoller,M.J. (1995) Phage display selection of ligand residues important for Src homology 3 domain binding specificity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 10909–10913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A.F., Oleynikov,Y., Kislauskis,E.H., Taneja,K.L. and Singer,R.H. (1997) Characterization of a β-actin mRNA zipcode-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 2158–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Schlüter K., Jockusch,B.M. and Rothkegel,M. (1997) Profilins as regulators of actin dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1359, 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder K.E. and Yost,H.J. (1996) Xenopus poly (A) binding protein maternal RNA is localized during oogenesis and associated with large complexes in blastula. Dev. Genet., 19, 268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N. and Frazier,W.A. (1998) Direct use of synthetic peptides for antiserum production. Biotechniques, 25, 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C.P., Knoblich,J.A., Chan,Y.M., Jiang,M.M., Jan,L.Y. and Jan,Y.N. (1998) Miranda as a multidomain adapter linking apically localized Inscuteable and basally localized Staufen and Prospero during asymmetric cell division in Drosophila. Genes Dev., 12, 1837–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu A.-B. and Wilkinson,M.F. (2000) The double lives of shuttling mRNA binding proteins. Cell, 102, 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H., LeBowitz,J.H., Baldwin,A.S.,Jr and Sharp,P.A. (1988) Molecular cloning of an enhancer binding protein: isolation by screening of an expression library with a recognition site DNA. Cell, 52, 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi M.C., Fromont,M., Rain,J.C., Wan,L., Wang,F., Legrain,P. and Dreyfuss,G. (1998) Functional conservation of the transportin nuclear import pathway in divergent organisms. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 4141–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks A.B., Rider,J.E., Hoffman,N.G., Fowlkes,D.M., Quillam,L.A. and Kay,B.K. (1996) Distinct ligand preferences of Src homology 3 domains from Src, Yes, Abl, Cortactin, p53bp2, PLCγ, Crk and Grb2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 1540–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D., Beuchle,D. and Nüsslein-Volhard,C. (1991) Staufen, a gene required to localize maternal RNAs in the Drosophila egg. Cell, 66, 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell C.L. and Singer,R.H. (1991) Requirement of microfilaments in sorting of actin messenger RNA. Science, 253, 1275–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen G.H. and Melton,D.A. (1993) Processed Vg1 protein is an axial mesoderm inducer in Xenopus. Cell, 74, 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui S., Dai,T., Roettger,S., Schempp,W., Salido,E.C. and Yen,P.H. (2000a) Identification of two novel proteins that interact with germ-cell-specific RNA-binding proteins DAZ and DAZL1. Genomics, 65, 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui S., Dai,T., Warren,S.T., Salido,E.C. and Yen,P.H. (2000b) Association of the mouse infertility factor DAZL1 with actively translating polyribosomes. Biol. Reprod., 62, 1655–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D.L. and Weintraub,H. (1994) Expression of achaete-scute homolog 3 in Xenopus embryos converts ectodermal cells to a neural fate. Genes Dev., 8, 1434–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman S. (1998) FH proteins as cytoskeletal organizers. Trends Cell Biol., 8, 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks D.L. and Melton,D.A. (1987) A maternal mRNA localized to the vegetal hemisphere in Xenopus eggs codes for a growth factor related to TGF-β. Cell, 51, 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm J.E., Mansfield,J., Hom-Booher,N., Wang,S., Turck,C.W., Hazelrigg,T. and Vale,R.D. (2000) Isolation of a ribonucleoprotein complex involved in mRNA localization in Drosophila oocytes. J. Cell Biol., 148, 427–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson G.M., Sun,Y., Lu,H. and Brewer,G. (1999) Assembly of AUF1 oligomers on U-rich RNA targets by sequential dimer association. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 33374–33381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolven A.K., Belmont,L.D., Mahoney,N.M., Almo,S.C. and Drubin,D.G. (2000) In vivo importance of actin nucleotide exchange catalyzed by profilin. J. Cell Biol., 150, 895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yisraeli J.K. and Melton,D.A. (1988) The maternal mRNA Vg1 is correctly localized following injection into Xenopus oocytes. Nature, 336, 592–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yisraeli J.K., Sokol,S. and Melton,D.A. (1990) A two-step model for the localization of maternal mRNA in Xenopus oocytes: involvement of microtubules and microfilaments in the translocation and anchoring of Vg1 mRNA. Development, 108, 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. and King,M.L. (1996) Xenopus VegT RNA is localized to the vegetal cortex during oogenesis and encodes a novel T-box transcription factor involved in mesodermal patterning. Development, 122, 4119–4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. et al. (1999) Vg1 RBP intracellular distribution and evolutionarily conserved expression at multiple stages during development. Mech. Dev., 88, 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]