Abstract

Transamidation is a post-translational modification of proteins mediated by tissue transglutaminase II (TGase), a GTP-binding protein, participating in signal transduction pathways as a non-conventional G-protein. Retinoic acid (RA), which is known to have a role in cell differentiation, is a potent activator of TGase. The activation of TGase results in increased transamidation of RhoA, which is inhibited by monodansylcadaverine (MDC; an inhibitor of transglutaminase activity) and TGaseM (a TGase mutant lacking transglutaminase activity). Transamidated RhoA functions as a constitutively active G-protein, showing increased binding to its downstream target, RhoA-associated kinase-2 (ROCK-2). Upon binding to RhoA, ROCK-2 becomes autophosphorylated and demonstrates stimulated kinase activity. The RA-stimulated interaction between RhoA and ROCK-2 is blocked by MDC and TGaseM, indicating a role for transglutaminase activity in the interaction. Biochemical effects of TGase activation, coupled with the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesion complexes, are proposed to have a significant role in cell differentiation.

Keywords: retinoic acid/RhoA/RhoA-associated kinase/tissue transglutaminase/transamidation

Introduction

RhoA, a member of the small molecular weight Ras superfamily of G-proteins (Hamm, 1998; Bishop and Hall, 2000), is implicated in mediating reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in response to extracellular signals such as lysophosphatidic acid and certain growth factors (Schmitz et al., 2000). It has been shown to have an important role in the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesion complexes (Ridley and Hall, 1992, 1994), regulation of cell morphology (Paterson et al., 1990), cell aggregation (Tominaga et al., 1993), smooth muscle contraction (Hirata et al., 1992) and differentiation (Mack et al., 2001). RhoA also initiates signaling events that affect gene expression and mediate Ras-induced malignant cell transformation (Symons, 1996). Like all G-proteins (Bourne et al., 1991), RhoA binds GTP in the active state and, following hydrolysis, returns to an inactive GDP-bound state. Two domains, switch 1 and 2, are involved in conformational changes during hydrolysis of GTP to GDP (Wittinghofer and Nassar, 1996). Switch 1 (RhoA amino acids 34–42) is involved in activation of RhoA downstream effectors/targets, and switch 2 (RhoA amino acids 63–79) is implicated in GTP hydrolysis (Wei et al., 1997). The putative target proteins for RhoA include protein kinase N (Amano et al., 1996b), rhophilin (Watanabe et al., 1996), citron (Madaule et al., 1995), rhotekin (Reid et al., 1996), myosin-binding subunit of myosin phosphatase (Kimura et al., 1996), p140mDia (Watanabe et al., 1997) and Rho-associated kinase (Matsui et al., 1996). Although the functions of most RhoA targets remain unknown, p140 mDia and Rho-associated kinase isozymes mediate RhoA affects on the actin cytoskeleton. A mammalian homolog of Drosophila diaphanous, p140mDia, controls actin polymerization by binding and the resultant accumulation of the actin-binding protein profilin (Watanabe et al., 1997). The Rho-associated kinase isozymes, p160 ROCK (Ishizaki et al., 1997) and ROCK-2 (Leung et al., 1996), are coiled-coil serine–threonine kinases sharing 98% identity within the kinase domain and mediate RhoA-induced actin–myosin interaction for the formation of stress fibers (Redowicz, 1999). These kinases have been implicated in regulation of cell contractility, by indirectly increasing phosphorylation of the myosin light chain through the inhibition of myosin phosphatase activity (Kimura et al., 1996) or by directly phosphorylating the myosin light chain, independently of myosin light chain kinase (Amano et al., 1996a).

Cytotoxic necrotizing factor-1 (CNF-1), produced from uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli (Boquet and Fiorentini, 1999), deamidates RhoA Gln63 to glutamic acid (Flatau et al., 1997; Schmidt et al., 1997). Gln63 is a critical residue of the RhoA switch 2 domain for GTP hydrolysis (Rittinger et al., 1997). By deamidating Gln63 of RhoA, CNF-1 inhibits both intrinsic GTP hydrolysis and that stimulated by GTPase-activating protein (GAP), resulting in constitutive activation (Flatau et al., 1997; Schmidt et al., 1997), and in effect leading to increased stress fiber formation (Fiorentini et al., 1997). In addition, CNF-1 has been shown to possess in vitro transglutaminase activity in the presence of primary amines and to transamidate RhoA (Schmidt et al., 1998). The toxin binds to the switch 2 region (amino acids Asp59–Asp78) of RhoA for deamidation/transglutamination (Lerm et al., 1999).

Tissue transglutaminase II (TGase) is known to participate in all-trans-retinoic acid (RA)-mediated signaling events as a G-protein (Singh et al., 1995, 1998) and transamidate targets such as RhoA (Schmidt et al., 1998) and the retinoblastoma gene product (pRB; Oliverio et al., 1997). Ubiquitous TGase is a monomeric globular protein implicated in functions that result in intra- and/or extracellular structural alterations (Greenberg et al., 1991), such as remodeling of extracellular matrix (Aeschlimann et al., 1995), stimulus–secretion coupling (Bungay et al., 1986), receptor-mediated endocytosis (Davies et al., 1980), cell differentiation (Aeschlimann et al., 1993), tumor growth (Johnson et al., 1994) and programmed cell death (Bernassola et al., 1999). However, specific modification of defined intracellular substrate proteins by TGase has not been linked to respective functions.

Here, we report that the in vivo transamidation of RhoA leads to increased binding to ROCK-2, in response to RA treatment of HeLa cells. Binding of transamidated RhoA to ROCK-2 is accompanied by stimulated autophosphorylation of ROCK-2 and phosphorylation of the substrate, vimentin. Monodansylcadaverine (MDC; a specific inhibitor of transglutaminase activity) and TGaseM (a mutant of TGase that lacks transglutaminase activity) block the interaction between RhoA and ROCK-2, demonstrating a specific role for transamidation in the activation process. We also show the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesion complexes, which are hallmarks of RhoA activation, in RA-treated HeLa cells.

Results

RA treatment results in activation of TGase and in vivo transamidation of a 24 kDa protein in HeLa cells

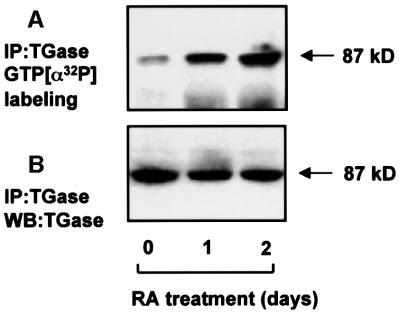

RA treatment of HeLa cells stimulates GTP binding to TGase, as shown by affinity cross-linking of GTP, in immunoprecipitates of TGase (Figure 1A), whereas the amount of TGase protein remains unchanged (Figure 1B). The transamidation activity of TGase also increases in response to RA treatment of HeLa cells, as shown by transglutaminase activity in lysates of RA-treated (80 ± 10 nmol of putrescine incorporated/mg of casein/mg of protein) and untreated cells (20 ± 6 nmol putrescine incorporated/mg of casein/mg of protein).

Fig. 1. Increased photolabeling of GTP in RA-treated HeLa cells. HeLa cells were treated with RA or left untreated for different periods of time. Cells were lysed in 25 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.4 containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 100 µM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1% Triton X-100. The lysate was sedimented at 10 000 g for 30 min and immunoprecipitated using TGase antibody. The immunoprecipatates were suspended in labeling buffer (as described in Materials and methods) and photolabeled with [α-32P]GTP (A) or western blotted with TGase antibody (B). The arrows mark the position of a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 87 kDa. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

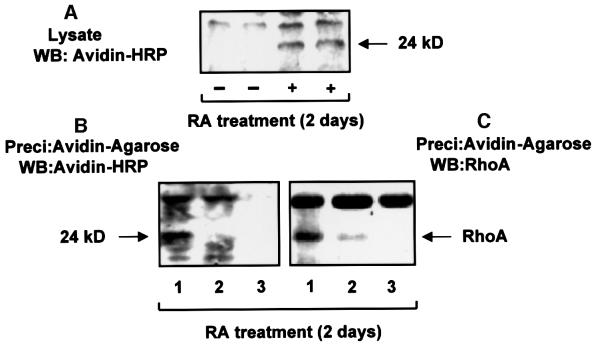

To determine the role of transamidation further, we examined in vivo transamidated proteins which may couple to TGase-mediated (RA) effects. HeLa cells (RA treated and untreated) were used for in vivo transamidation experiments using biotinylated pentylamine in the presence of aminoguanidine (an inhibitor of amine oxidase), as described in Materials and methods. The cells were lysed and western blotted with avidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Figure 2A). We detected a biotinylated band at 24 kDa, in response to RA treatment. To determine whether the 24 kDa protein band is biotinylated, the lysate prepared from RA- and biotinylated pentylamine-treated cells was precipitated with avidin–agarose and western blotted with avidin–HRP. As shown in Figure 2B, lane 1, the presence of a band at 24 kDa demonstrates the cross-linking (or transamidation) of biotinylated pentylamine to the 24 kDa protein in response to RA treatment.

Fig. 2. RA treatment of HeLa cells leads to transamidation of RhoA. RA-treated (+) or untreated (–) HeLa cells were used for in vivo transamidation, with biotinylated pentylamine in the presence of 100 µM aminoguanidine. Separate sets of RA-treated HeLa cells were used for MDC (200 µM for 1 h) treatment and for TGaseM overexpression (using LipofectaminePlus from Life Technologies). Cells were lysed and used for precipitation with avidin–agarose. Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE (12.5% acrylamide) and transferred to a PVDF membrane for western blotting with avidin–HRP and RhoA antibody. (A) Lysate proteins (20 µg) from RA-treated and untreated cells were western blotted with avidin–HRP. (B) Avidin–agarose-precipitated proteins were blotted with avidin–HRP. Lane 1, RA-treated; lane 2, RA- and MDC-treated; and lane 3, RA-treated TGaseM-overexpressing cells. The blot was stripped and reprobed with RhoA antibody (C). The level of TGaseM overexpression is shown in Figure 8C. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Identification of the 24 kDa transamidated protein as RhoA

To determine the role of transglutaminase activity in transamidation of the 24 kDa protein, we used MDC (Katoh et al., 1996) and the TGaseM mutant of TGase (Lee et al., 1993) for inhibition of in vivo transglutaminase activity. Treatment with MDC and overexpression of TGaseM blocked the transamidation of the 24 kDa protein, as shown in Figure 2B, lanes 2 and 3, indicating involvement of the transglutaminase activity of TGase in the transamidation process. After stripping (Figure 2B), western blotting demonstrated that the 24 kDa protein is RhoA. As shown (Figure 2C, lane 1), the precipitation of RhoA by avidin–agarose is blocked by MDC treatment (lane 2) and TGaseM overexpression (lane 3), demonstrating a role for transglutaminase activity in precipitation of RhoA. By using avidin–agarose precipitation experiments, we pulled down ∼5% of RhoA, indicating the amount of endogenous RhoA being modified. The possibility of an indirect association of RhoA with another transamidated protein (pulled down by avidin–agarose) can not be excluded.

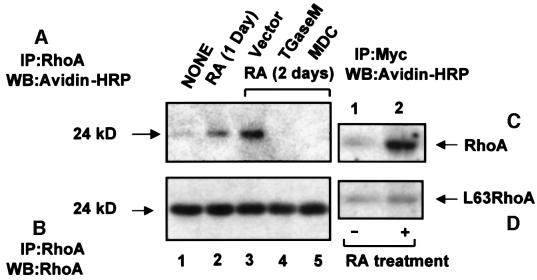

For further confirmation of RhoA transamidation, RA-pre-treated HeLa cells were used for treatment with MDC and overexpression of TGaseM. After performing in vivo transamidation, cells were lysed, immunoprecipitated by RhoA antibody and western blotted with avidin–HRP. As shown in Figure 3A, there is RA-stimulated transamidation of RhoA (lanes 2 and 3), which is blocked by TGaseM overexpression (lane 4) and MDC treatment (lane 5), demonstrating that the transglutaminase activity of TGase is involved in the transamidation process. A parallel set of immunoprecipitates was used for western blotting with RhoA antibody to determine the amount of RhoA present in different samples (Figure 3B, lanes 1–5). We did not observe cross-linking of MDC (an autofluorescent compound) to RhoA. Transamidation of biotinylated pentylamine was also performed using RA-treated and Myc-tagged wild-type and L63RhoA-overexpressing cells. As shown, RA promotes transamidation of wild-type RhoA (Figure 3C, lane 2 compared with lane 1) and not L63RhoA (Figure 3D, lane 2 compared with lane 1).

Fig. 3. Transamidation of RhoA is mediated by the transglutaminase activity of TGase. HeLa cells were grown to subconfluence in 25 mm, 6-well plates and treated with RA for different periods of time. One set was used as a control, a second for overexpression of TGaseM, with a parallel set for transfection with vector (pSG5) alone. The third set was treated with MDC (200 µM) for 1 h, together with a control treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; 0.01%) alone. Transamidation (in vivo) was performed using biotinylated pentylamine in the presence of aminoguanidine. Cells were lysed in 200 µl of lysis buffer and used for immunoprecipitation with RhoA antibody. After washing the immunoprecipitates with PBS, samples were suspended in sample buffer and run on a 12.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and blotted with avidin–HRP (A). Lane 1, untreated cells; lane 2, RA treated for 1 day; lane 3, RA treated for 2 days and vector transfected; lane 4, RA treated (2 days) and TGaseM overexpressing; and lane 5, RA- (2 days) and MDC-treated cells. A duplicate set of immunoprecipitates was blotted with RhoA antibody (B, lanes 1–5, representing treatments similar to those in A), showing the total amount of RhoA immunoprecipitated. Another set of untreated and RA-treated cells (grown to subconfluence in 6-well 25 mm plates) transfected with Myc-tagged wild-type or L63RhoA in pCDNA3 vector was used for in vivo transamidation. After lysing the cells, RhoA was immunoprecipitated by anti-Myc antibody. Samples were run on a 12.5% acrylamide gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane and western blotted with avidin–HRP (C and D). The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

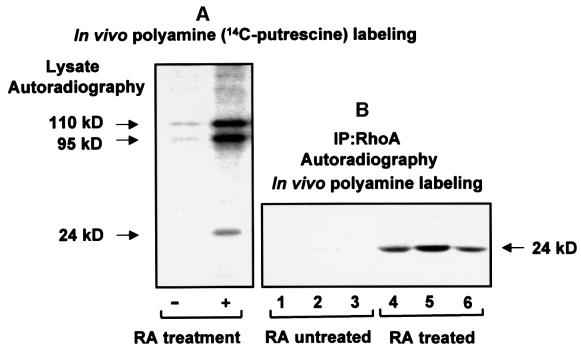

The RA effect on in vivo transamidation of RhoA was also determined using 14C-labeled polyamines. As shown (Figure 4A), RA promotes incorporation of putrescine into 110, 95 and 24 kDa proteins. We have identified the 110 kDa band as pRB, with transamidation resulting in its stabilization and resistance toward caspase-7-mediated proteolysis (Singh et al., 2001). The other major band at 95 kDa, transamidated in response to RA, is unidentified. As demonstrated earlier by using biotinylated pentylamine, the 24 kDa protein band belongs to transamidated RhoA. By immunoprecipitating RhoA from [14C]polyamine-labeled cells, and performing autoradiography, we show that labeling of putrescine, spermine and spermidine with RhoA increases in approximately equal proportions in response to RA treatment (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4. RA treatment promotes in vivo labeling of polyamines. RA treatment of HeLa cells was performed in the presence of 0.5% fetal bovine serum for 2 days. Medium containing serum was replaced with RPMI 1640 medium and the cells used for in vivo transamidation in the presence of 14C-labeled polyamines (Masuda et al., 2000). Cells were lysed and the lysate was used for immunoprecipitation with RhoA antibody. After washing the immunoprecipitates with PBS, samples were run on a 5–15% gradient gel, and autoradiographed using a signal enhancer kit from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. (A) Lysates (50 µg of protein) prepared from [14C]putrescine-labeled cells were used for autoradiography. (B) RhoA immunoprecipitates from lysates of cell samples, which were labeled with different [14C]polyamines, were autoradiographed. Lanes 1 and 4, putrescine; lanes 2 and 5, spermine; lanes 3 and 6, spermidine.

RA stimulates the interaction between RhoA and the downstream binding partner ROCK-2

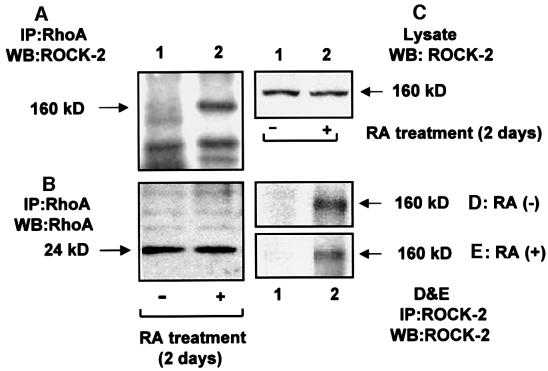

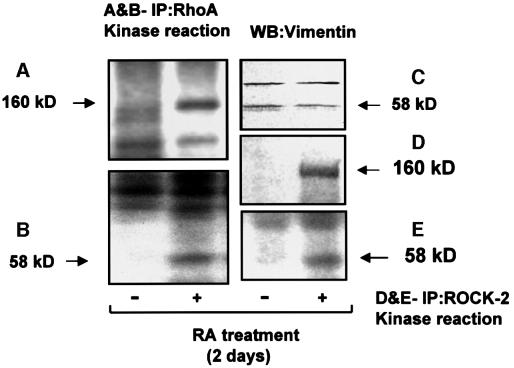

To determine the association of ROCK-2 with RhoA, RA-treated and untreated HeLa cells were lysed and used for immunoprecipitation of RhoA. The immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to SDS–PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. As shown by western blotting for RhoA (Figure 5B), there is no change in the amount of precipitated RhoA after RA treatment. The upper portion of the membrane (Figure 5A), which was blotted with ROCK-2 antibody, shows a band at 160 kDa (Figure 5A, lane 2). The band is not present in RA-untreated samples (lane 1), showing the association of RhoA with ROCK-2 following RA treatment of cells. Specificity of the ROCK-2 antibody for precipitation and identification of the 160 kDa protein band was confirmed by immunoprecipitating and western blotting the lysates for ROCK-2 (Figure 5D and E). The 160 kDa band is absent in lane 1, where goat IgG was used, and present in lane 2, where the ROCK-2 antibody was used. The level of expression of ROCK-2 is not affected by RA treatment, as shown by western blotting the lysates of RA-treated and untreated cells for ROCK-2 (Figure 5C). In a similar set of experiments, a kinase reaction (Figure 6) was performed using vimentin as a ROCK-2 substrate. ROCK-2 is a kinase activated by the GTP-bound form of RhoA. As shown, there is stimulation of a phosphorylated band at 160 kDa belonging to autophosphorylated ROCK-2 (Figure 6A), and a 58 kDa band representing vimentin (Figure 6B), in RA-treated samples, the latter confirmed by western blots using vimentin antibody (Figure 6C). As a positive control, a kinase reaction was performed in a parallel set of ROCK-2 immunoprecipitates (Figure 6D and E), demonstrating that RA promoted ROCK-2 autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of vimentin. We could not detect the presence of protein kinase N and protein kinase C-related kinase-2 (other serine–threonine kinase targets of RhoA) in the immunoprecipitates of RhoA. A western blot of lysates demonstrates that these proteins are expressed in HeLa cells and the expression is not affected by RA treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 5. RhoA binds ROCK-2 in RA-treated HeLa cells. RhoA was immunoprecipitated from untreated (–) and RA-treated (+) HeLa cells. (A) The samples were run on a 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, and proteins transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with ROCK-2 antibody. (B) A duplicate set was run on a 5–15% gradient SDS–polyacrylamide gel, and proteins transferred to a PVDF membrane and blotted with RhoA antibody. (C) To compare the expression level, proteins (20 µg) from untreated (lane 1) and RA-treated (lane 2) cell lysates were blotted with ROCK-2 antibody. (D and E) The specificity of the antibody was determined by immunoprecipitating ROCK-2 from untreated and RA-treated cell lysates and western blotting for ROCK-2. Lane 1 represents precipitation of the lysate in the presence of goat IgG; lane 2 represents precipitation in the presence of ROCK-2 antibody. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Fig. 6. RA treatment of HeLa cells leads to activation of ROCK-2. RhoA was immunoprecipitated from untreated (–) and RA-treated (+) HeLa cells. The immunoprecipitates were suspended in 30 µl of lysis buffer and a kinase reaction performed by adding vimentin (1 µg) and 2 mCi of [γ-32P]ATP. Samples were run on a 5–15% gradient SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane and exposed to X-ray film for 48 h for ROCK-2 (A) and 12 h for vimentin (B). As shown, there is a phosphorylated band at 160 kDa, representing ROCK-2, and a band at 58 kDa, representing vimentin, confirmed by western blotting for ROCK-2 (Figure 5A) and vimentin (C), respectively. In the positive control, a kinase reaction was performed in ROCK-2 immunoprecipitates obtained from untreated and RA-treated cells. The samples were run on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel, and proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and autoradiographed. The upper half of the nitrocellulose membrane was exposed to X-ray film for 4 days (D), and the lower half for 2 days (E). Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

The interaction between RhoA and ROCK-2 is dependent on the transglutaminase activity of TGase

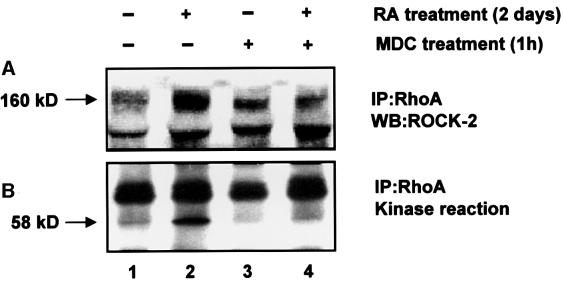

RA-treated and untreated HeLa cells were exposed to MDC, lysed and used for immunoprecipitation with RhoA antibody. Immunoprecipitates were used for western blotting and the kinase reaction to determine the effect of MDC on RA-induced interaction between RhoA and ROCK-2. As shown by western blotting with ROCK-2 antibody (Figure 7A, lane 4 compared with lane 2) and performing a kinase reaction in the presence of vimentin (Figure 7B, lane 4 compared with lane 2), MDC treatment of HeLa cells inhibits RA-induced binding of ROCK-2 (to RhoA) and phosphorylation of vimentin, respectively. There is no significant effect of MDC treatment on ROCK-2 binding (Figure 7A, lane 3 compared with lane 1) and vimentin phosphorylation (Figure 7B, lane 3 compared with lane 1) in untreated cells.

Fig. 7. MDC, a specific inhibitor of TGase, inhibits activation of ROCK-2. Untreated (–) and RA-treated (+) HeLa cells were exposed to MDC (200 µM in DMSO) for 1 h. A similar set was exposed to DMSO (0.001%) as a control. RhoA was immunoprecipitated from both sets and a kinase reaction performed in immunoprecipitates using vimentin as the substrate, as noted in Figure 6. Samples were run on a 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The top portion of the membrane was immunoblotted for ROCK-2 (A) and the bottom portion exposed to X-ray film for 24 h (B). As shown, the increased binding of ROCK-2 to RhoA in the RA-treated sample (A, lane 2), was blocked by MDC treatment (A, lane 4). There is 3- to 4-fold less binding of ROCK-2 to RhoA in the untreated sample (A, lane 1), which is not affected following exposure to MDC (A, lane 3). Similarily, exposure of RA-treated cells to MDC inhibits activation of ROCK-2, as shown by phosphorylation of vimentin (B, lane 4, compared with lane 2). There is no phosphorylation of vimentin in the untreated sample (B, lane 1), which is not affected by MDC treatment (B, lane 3). The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

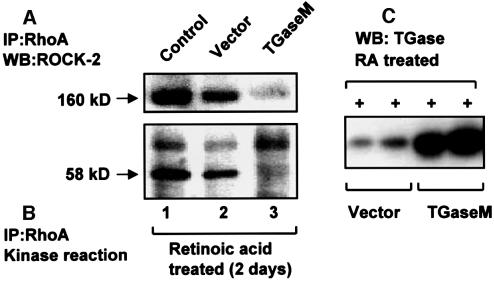

Similarily, binding between RhoA and ROCK-2 obtained in RA-treated and vector-transfected cells (Figure 8A, lane 2) is inhibited by overexpression of TGaseM (Figure 8A, lane 3). Transient overexpression of TGaseM in RA-treated HeLa cells increases the TGase protein level by ∼6-fold (Figure 8C). A kinase reaction performed in RhoA immunoprecipitates obtained from TGaseM-overexpressing cells does not show phosphorylation of vimentin (Figure 8B, lane 3 compared with lane 2), indicating an important role for the transglutaminase activity in enhancing the interaction of RhoA with ROCK-2 in response to RA treatment. The significant reduction in the RhoA–ROCK-2 interaction in response to TGaseM overexpression in RA-treated cells (unlike sham-transfected cells, lane 2 compared with lane 1) may be attributed to a higher level of transfection efficiency of TGaseM (>60%) and the resulting effect on total transglutaminase activity in RA-treated cells.

Fig. 8. Overexpression of TGaseM blocks the interaction between RhoA and ROCK-2. TGaseM was overexpressed in RA-pre-treated HeLa cells using LipofectaminePlus. The lysate prepared from vector (control)- and TGaseM-transfected cells was western blotted with TGase antibody to determine the level of protein expression. As shown, there is an ∼6-fold (determined by densitometric analysis of bands, using ImageQuant software) increase in TGase protein in TGaseM-transfected cells compared with vector (C). RhoA was immunoprecipitated from RA-treated, TGaseM-overexpressing cells and controls of RA-treated cells/and cells transfected with vector (pSG5). A kinase reaction was performed in immunoprecipitates in the presence of vimentin, as noted in Figure 6. Samples were run on a 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and the top portion of the membrane immunoblotted for ROCK-2 and the bottom exposed to X-ray film (24 h). As shown, overexpression of TGaseM blocks the binding of ROCK-2 (A, lane 3), compared with control (A, lane 1) or cells transfected with vector alone (A, lane 2). Similarly, there is little phosphorylation of vimentin in TGaseM-overexpressing cells (B, lane 3) compared with control (B, lane 1) or vector-transfected cells (B, lane 2). The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

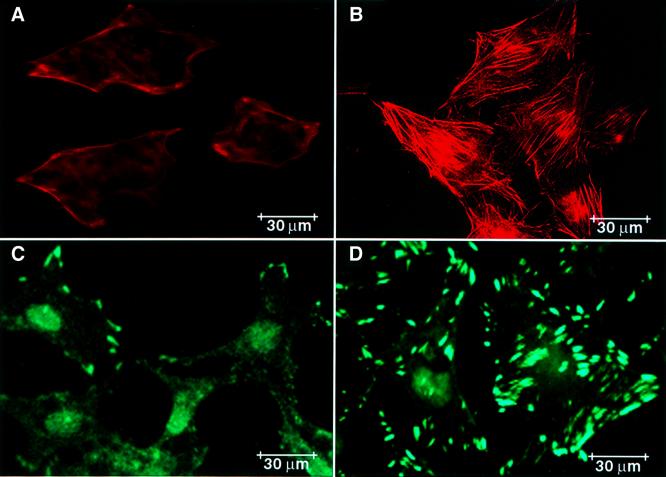

RA treatment of HeLa cells induces cytoskeletal rearrangement and adhesion complex formation

RA treatment of HeLa cells leads to stress fiber formation (Figure 9A and B) and increased cell adhesion (Figure 9C and D). As shown, there is no stress fiber formation in untreated cells (Figure 9A) compared with treated cells (Figure 9B), where RA induces stress fiber formation. Similarly, there is little adhesion complex formation in control cells (Figure 9C) compared with treated cells (Figure 9D), which develop adhesion complexes after RA treatment. Overexpression of TGaseM and treatment with MDC blocked RA-induced stress fiber and focal adhesion complex formation (data not shown), indicating a role for transglutaminase in both processes.

Fig. 9. RA induces stress fiber and adhesion complex formation in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were grown to subconfluence on chamber slides (tissue culture) and treated with RA for 2 days. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and incubated with phalloidin labeled with Texas Red for visualization of actin stress fibers by immunofluoresence microscopy. (A) Untreated and (B) RA-treated cells. For the detection of adhesion complex formation, cells were first incubated with vinculin antibody, and then with secondary anti-mouse vinculin–fluorescein isothiocyanate for immunofluoresence microscopy. (C) Untreated and (D) RA-treated cells. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

The molecular actions of retinoids are mediated primarily by nuclear retinoid receptors (RARα, β and γ) and the retinoid X receptors (RXRα, β and γ), which function as liganded transcription factors (Greiner et al., 2000; Klaholz et al., 2000). RA, a metabolite of vitamin A, is a potent inducer of tissue transglutaminase (GTPase and transglutaminase activities) and cell differentiation (Aeschlimann et al., 1993; Nagy et al., 1996; Singh and Cerione, 1996). The nucleotide (GTPγS) sensitivity of the transglutaminase activity of TGase, as shown in a rabbit liver nuclear pore complex (Singh et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1998), may have an important role in various signaling events. To determine the role of TGase-associated proteins in signal transduction, we isolated eukaryotic initiation factor-5A (eIF-5A), which binds TGase in a nucleotide-dependent manner and the binding of which is increased in RA-treated HeLa cells (Singh et al., 1998). The interaction of eIF-5A with TGase is an example where binding is coupled to the GTPase cycle of TGase and is responsive to RA treatment, but the significance of this interaction in terms of a role in RA-regulated cellular function(s) is not known. In another study, pRB, which is important for cell survival, was transamidated by TGase in vivo and, following transamidation, pRB became resistant to caspase-7-mediated proteolysis (Singh et al., 2001). Transamidation of pRB by TGase was shown to increase in response to RA treatment, where HL60 cells differentiated into granulocytes. It was hypothesized that transamidated pRB may have an important role in RA-induced cell cycle arrest during differentiation and hence survival of granulocytes.

RA treatment of HeLa cells stimulates GTP binding (and transglutaminase activity) to TGase, without affecting the protein level (Figure 1). The 48 h time phase for RA-mediated TGase activation is probably related to an increase in GTP binding (and transglutaminase activity), secondary to post-translational modification of TGase or association with another protein (Singh and Cerione, 1996). To study the role of TGase in RA-mediated signaling further, we performed in vivo transamidation, using HeLa cells for identification of transamidated proteins. For this purpose, cells were incubated with biotinylated pentylamine, which is imported intracellularly using cellular transporters (Minchin et al., 1991; Poulin et al., 1995) and cross-linked to potential substrates of TGase by a transglutaminase-catalyzed reaction. By precipitating labeled proteins with avidin–agarose, we show RA-induced transamidation of a 24 kDa protein (Figure 2A). MDC treatment and TGaseM overexpression block transamidation (Figure 2B), demonstrating that the transglutaminase activity of TGase is required for labeling of a biotinylated pentylamine. We have identified the 24 kDa protein as RhoA (Figure 2C), and demonstrated that transamidation is sensitive to MDC and TGaseM overexpression.

The sensitivity of RhoA transamidation to MDC and TGaseM may be due to TGase-catalyzed cross-linking of biotinylated polyamine to RhoA in response to RA treatment (Figure 3). MDC, a synthetic autofluorescent amine substrate of TGase, is widely used to inhibit in vivo transglutaminase activity (Hebert et al., 2000; Ou et al., 2000), and has been shown to be cross-linked to the TGase substrates LAV1-2 (Mottahedeh and Marsh, 1998) and vimentin (Clement et al., 1998). We could not detect incorporation of MDC into RhoA using conditions similar to those for in vivo transamidation of a biotinylated pentylamine. Thus, it may compete with biotinylated pentylamine for binding to TGase, preventing incorporation into RhoA. Because of its larger size and hydrophobic characteristics, it may not be transamidated to glutamine residues, and could block in vivo transamidation of RhoA. MDC has also been used to inhibit clathrin-mediated endocytosis and prevent α2A adrenergic receptor- and β2 adrenergic receptor-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1 and 2 (Pierce et al., 2000). TGaseM binds GTP, but does not possess transglutaminase activity and, therefore, overexpression of TGaseM in RA-treated HeLa cells results in decreased transglutaminase activity (30 ± 6 nmol putrescine compared with 80 ± 10 nmol putrescine incorporated/mg of casein/mg of protein in RA-treated cells). It is not known whether TGaseM overexpression suppresses RA-stimulated TGase activity, or competes with TGase for binding to RhoA, blocking its transamidation.

RhoA is transamidated in vitro at positions 52, 63 and 136 (Schmidt et al., 1998). To determine the in vivo site of transamidation, we transfected RA-treated and untreated HeLa cells with Myc-tagged wild-type and L63RhoA. Unlike wild-type, L63RhoA is not transamidated in response to RA (Figure 3C and D), indicating that Gln63 is a critical site and glutamine residues at positions 52 and 163 are not available for in vivo transamidation. In addition to biotinylated pentylamine, we have shown cross-linking of naturally occurring polyamines such as putrescine, spermine and spermidine to RhoA, indicating that they are also in vivo substrates of TGase, and that cross-linking is promoted in response to RA treatment of cells (Figure 4).

Analogously to the GTP-bound form of RhoA, transamidated RhoA may interact with downstream targets such as ROCK-2 (Matsui et al., 1996). Reports have demonstrated that polyamines are cross-linked to the protein-bound glutamine of RhoA (Schmidt et al., 1998; Masuda et al., 2000), although the biological significance of these modifications remains to be determined. In an effort to determine the role of RhoA transamidation in RA-mediated effects, we have shown RA-stimulated binding between RhoA and ROCK-2, which is accompanied by increased autophosphorylation of ROCK-2 and phosphorylation of its substrate, vimentin (Figures 5 and 6). The RA-stimulated binding of RhoA and ROCK-2 (and activation of kinase activity toward vimentin) is blocked by treatment with MDC (Figure 7) and overexpression of TGaseM (Figure 8), indicating that transglutaminase activity is required for the interaction. In an earlier study, it was reported that ROCK-2 co-precipitated with V14 RhoA (Ishizaki et al., 1996), and associated with GTP-bound RhoA on an affinity column (Matsui et al., 1996). After transamidation by dermonecrotizing toxin, RhoA binds to ROCK-2 and activates it ∼2-fold (Masuda et al., 2000). It was suggested that transamidation of RhoA is sufficient to trigger conformational changes in ROCK-2, and that the kinase activity may not be required for signaling purposes. The possibility can not be excluded that in addition to transamidated RhoA, another protein is involved in RA-stimulated autophosphorylation and kinase activity of ROCK-2 in HeLa cells. Unlike ROCK-2, interaction of protein kinase N and protein kinase C-related kinase-2 (other targets of RhoA) with RhoA may not be strong enough for co-precipitation.

RA treatment of HeLa cells promotes stress fiber and focal adhesion complex formation (Figure 9), which is blocked by MDC and TGaseM overexpression, demonstrating involvement of transamidation in inducing stress fiber and focal adhesion complex formation. Similar effects have been shown in SiHa carcinoma cells in response to RA treatment (Matarrese et al., 1998). The finding that RhoA is transamidated, and binds to and activates ROCK-2 in response to RA, may indicate its involvement in inducing cytoskeletal rearrangement and focal adhesion complex formation. However, involvement of another protein in affecting cytoskeletal rearrangement and assembly of focal adhesion complex can not be excluded. These findings are further supported by a recent report (Masuda et al., 2000) where in vitro transamidated RhoA induced stress fiber formation, when microinjected in Swiss 3T3 cells. Recently, TGase was identified as an integrin-binding adhesion co-receptor for fibronectin (Akimov et al., 2000). It is possible that TGase participates directly (in addition to transamidated RhoA) in RA-induced formation of the focal adhesion complex.

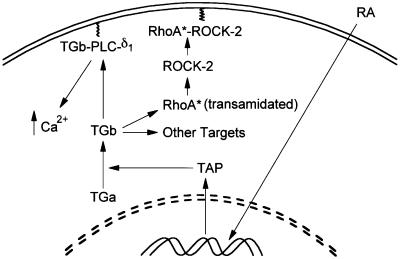

In summary, the RA-stimulated change in TGase activity involves TGase-associated protein (TAP; identity unknown), which converts the inactive form of TGase (TGa) to the active form (TGb; Singh and Cerione, 1996). The mechanism by which TAP modifies/activates TGa is not known. TGb (referred to as TGase above) binds to or modifies the target proteins that are important for cell survival, such as eIF-5A or pRB. We have proposed a model (Figure 10) to depict the role of TGase in coupling RA-mediated effects to cell differentiation. Accordingly, both the GTP-binding and the transglutaminase activity of TGase participate in signaling events leading to phospholipase-δ1 (PLC-δ1) activation (Nakaoka et al., 1994) and RhoA modification (or coupling to other targets), respectively. In the present study, we have demonstrated that RhoA is an in vivo substrate of TGase. After transamidation, RhoA elicits responses similar to GTP-bound RhoA, in promoting stress fiber and focal adhesion complex formation and in activating the downstream binding partner ROCK-2. Recent findings (Mack et al., 2001) indicate that RhoA-dependent regulation of the actin cytoskeleton selectively regulates smooth muscle cell differentiation, and that RhoA may serve as a convergence point for the multiple signaling pathways that regulate muscle cell differentiation. Future directions will include determining the role of transamidated RhoA in inducing transcription of new genes, which are required to promote cell differentiation. In addition to participating in α-1 adrenergic receptor coupling (Nakaoka et al., 1994), TGase may have an important role in RA-mediated cell cycle arrest (Benedetti et al., 1996) and differentiation (Nagy et al., 1996).

Fig. 10. Model depicting the role of TGase-catalyzed/coupled signaling pathways in RA-mediated effects. RA treatment of HeLa cells results in expression of TGase-associated protein (TAP; identity unknown). TAP associates/modifies TGa (inactive form of TGase), resulting in the appearance of TGb (or TGase). TGase causes transamidation of RhoA and formation of the RhoA–ROCK-2 complex. Transamidated RhoA functions as a constitutively active G-protein and, with ROCK-2, translocates to the plasma membrane, resulting in the initiation of downstream effects, and promotes formation of stress fibers and focal adhesion complexes. TGase may also bind other targets such as PLC-δ1, pRB and eIF-5A. Association of TGase with PLC-δ1, resulting in increased levels of calcium, may facilitate the transamidation process.

Materials and methods

Materials

RPMI 1640 and heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum were purchased from Gibco-BRL (Life Technologies). RA, vimentin, reagents in common use, vinculin and vimentin antibodies were from Sigma; 5-biotinamido-pentylamine and HRP-conjugated streptavidin were from Pierce; RhoA, ROCK-2 (C-20) antibodies and protein A/G–agarose were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; TGase monoclonal antibody was from Neomarkers; Texas Red–phalloidin and fluorescein-labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody were from Molecular Probes; and [γ-32P]ATP and [14C]putrescine were from NEN. Other 14C-labeled polyamines (spermine and spermidine) and the signal enhancer kit used for autoradiography of 14C-labeled proteins were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. The expression vectors pCDNA3 Myc-RhoA and pCDNA3 Myc-L63RhoA were provided by Dr Shubha Bagrodia (Sugen Inc.).

Cell culture

HeLa cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2.0 g/l sodium bicarbonate, 10 mM HEPES and 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) in a humidified atmosphere, with 5% (v/v) CO2, at 37°C. RA (5 µM) treatment was performed using HeLa cells grown to subconfluence in medium containing 10% serum, without antibiotics. For in vivo labeling of polyamines, RA treatment was performed in the presence of 0.5% (v/v) heat-inactivated FCS, and the medium was replaced every day.

Photoaffinity labeling of GTP

Photoaffinity labeling of GTP-binding proteins with [α-32P]GTP was performed as previously described (Singh and Cerione, 1996).

Kinase reaction

The kinase reaction was performed in a buffer (lysis buffer) that contained 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 mM MgCl2, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 10 µg/ml leupeptin and aprotinin, and 1 µg of vimentin. Samples (20 µl) were incubated with 1–2 mCi of [γ-32P]ATP in the above buffer (50 µl final volume) for 10 min at 30°C. Samples were then mixed with 5× sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. SDS–PAGE was performed using a 7.5% gel for experiments requiring western blotting for ROCK-2. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and exposed to Kodak X-OMAT XAR-5 film using DuPont image-intensifying screens.

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

Immunoprecipitation and western blotting of samples were performed as previously described (Singh et al., 1998).

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy

Immunoflourescence studies on stress fiber and focal adhesion complex formation were performed as previously described (Leung et al., 1996; Fiorentini et al., 1997).

Transglutaminase activity assay

RA-treated and untreated HeLa cells were lysed, and 100 µg of protein from the lysate were used for the assay of transglutaminase activity as previously described (Singh et al., 1995).

Transamidation reaction

HeLa cells (2 × 106) were treated (or untreated) with RA for 2 days and in vivo labeling of biotinylated pentylamine (100 µM; added in the medium) or [14C]polyamines was performed in the presence of aminoguanidine (100 µM), as described previously (Zhang et al., 1998; Masuda et al., 2000). Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), lysed using lysis buffer and precipitated with avidin–agarose or RhoA antibody. Transamidated proteins were detected by a 1:200 000 dilution of the secondary antibody (HRP-conjugated streptavidin from Pierce) or autoradiographed using a signal enhancer kit from Amersham, for the detection of 14C-labeled proteins.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HL60529 and 58439. K.M.B. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

References

- Aeschlimann D., Wetterwald,A., Fleisch,H. and Paulsson,M. (1993) Expression of tissue transglutaminase in skeletal tissues correlates with events of terminal differentiation of chondrocytes. J. Cell Biol., 120, 1461–1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aeschlimann D., Kaupp,O. and Paulsson,M. (1995) Transglutaminase-catalyzed matrix cross-linking in differentiating cartilage: identification of osteonectin as a major glutaminyl substrate. J. Cell Biol., 129, 881–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimov S.S., Krylov,D., Fleischman,L.F. and Belkin,A.M. (2000) Tissue transglutaminase is an integrin-binding adhesion coreceptor for fibronectin. J. Cell Biol., 148, 825–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M., Ito,M., Kimura,K., Fukata,Y., Chihara,K., Nakano,T., Matsuura,Y. and Kaibuchi,K. (1996a) Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase). J. Biol. Chem., 271, 20246–20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M., Mukai,H., Ono,Y., Chihara,K., Matsui,T., Hamajima,Y., Okawa,K., Iwamatsu,A. and Kaibuchi,K. (1996b) Identification of a putative target for Rho as the serine–threonine kinase protein kinase N. Science, 271, 648–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti L. et al. (1996) Retinoid-induced differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukemia involves PML-RARα-mediated increase of type II transglutaminase. Blood, 87, 1939–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernassola F., Rossi,A. and Melino,G. (1999) Regulation of transglutaminases by nitric oxide. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., 887, 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop A.L. and Hall,A. (2000) Rho GTPases and their effector proteins. Biochem. J., 348, 241–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boquet P. and Fiorentini,C. (1999) The cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 from Escherichia coli. In Aktories,K. and Just,I. (eds), Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology: Bacterial Toxins. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- Bourne H.R., Sanders,D.A. and McCormick,F. (1991) The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature, 349, 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungay P.J., Owen,R.A., Coutts,I.C. and Griffin,M. (1986) A role for transglutaminase in glucose-stimulated insulin release from the pancreatic β-cell. Biochem. J., 235, 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S., Velasco,P.T., Murthy,S.N.P., Wilson,J.H., Lukas,T.J., Goldman,R.D. and Lorand,L. (1998) The intermediate filament protein, vimentin, in the lens is a target for cross-linking by transglutaminase. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 7604–7609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P.J., Davies,D.R., Levitzki,A., Maxfield,F.R., Milhaud,P., Willingham,M.C. and Pastan,I.H. (1980) Transglutaminase is essential in receptor-mediated endocytosis of α2-macroglobulin and polypeptide hormones. Nature, 283, 162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini C., Fabbri,A., Flatau,G., Donelli,G., Matarrese,P., Lemichez,E., Falzano,L. and Boquet,P. (1997) Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (CNF1), a toxin that activates the Rho GTPase. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 19532–19537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatau G., Lemichez,E., Gauthier,M., Chardin,P., Paris,S., Fiorentini,C. and Boquet,P. (1997) Toxin-induced activation of the G protein p21 Rho by deamidation of glutamine. Nature, 387, 729–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg C.S., Birckbichler,P.J. and Rice,R.H. (1991) Transglutamin ases: multifunctional cross-linking enzymes that stabilize tissues. FASEB J., 5, 3071–3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner E.F., Kirfel,J., Greschik,H., Huang,D., Becker,P., Kapfhammer,J.P. and Schule,R. (2000) Differential ligand-dependent protein– protein interactions between nuclear receptors and a neuronal-specific cofactor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 7160–7165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm H.E. (1998) The many faces of G protein signaling. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert S.S., Daviau,A., Grondin,G., Latreille,M., Aubin,R.A. and Blouin,R. (2000) The mixed lineage kinase DLK is oligomerized by tissue transglutaminase during apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 32482–32490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata K., Kikuchi,A., Sasaki,T., Kuroda,S., Kaibuchi,K., Matsuura,Y., Seki,H., Saida,K. and Takai,Y. (1992) Involvement of rho p21 in the GTP-enhanced calcium ion sensitivity of smooth muscle contraction. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 8719–8722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki T. et al. (1996) The small GTP-binding protein Rho binds to and activates a 160 kDa Ser/Thr protein kinase homologous to myotonic dystrophy kinase. EMBO J., 15, 1885–1893. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki T., Naito,M., Fujisawa,K., Maekawa,M., Watanabe,M., Saito,Y. and Narumiya,S. (1997) p160ROCK, a Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein kinase, works downstream of Rho and induces focal adhesions. FEBS Lett., 404, 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T.S., Knight,C.R., el-Alaoui,S., Mian,S., Rees,R.C., Gentile,V., Davies,P.J. and Griffin,M. (1994) Transfection of tissue transglutaminase into a highly malignant hamster fibrosarcoma leads to a reduced incidence of primary tumour growth. Oncogene, 9, 2935–2942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh S., Nakagawa,N., Yano,Y., Satoh,K., Kohno,H., Ohkubo,Y., Suzuki,T. and Kitani,K. (1996) Hepatocyte growth factor induces transglutaminase activity that negatively regulates the growth signal in primary cultured hepatocytes. Exp. Cell Res., 222, 255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K. et al. (1996) Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase). Science, 273, 245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaholz B.P., Mitschler,A. and Moras,D. (2000) Structural basis for isotype selectivity of the human retinoic acid nuclear receptor. J. Mol. Biol., 302, 155–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.N., Arnold,S.A., Birckbichler,P.J., Patterson,M.K.,Jr, Fraij,B.M., Takeuchi,Y. and Carter,H.A. (1993) Site-directed mutagenesis of human tissue transglutaminase: Cys-277 is essential for trans glutaminase activity but not for GTPase activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1202, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerm M., Schmidt,G., Goehring,U.-M., Schirmer,J. and Aktories,K. (1999) Identification of the region of Rho involved in substrate recognition by Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (CNF1). J. Biol. Chem., 274, 28999–29004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung T., Chen,X.-Q., Manser,E. and Lim,L. (1996) The p160 RhoA-binding kinase ROKα is a member of a kinase family and is involved in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 5313–5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack C.P., Somlyo,A.V., Hautmann,M., Somlyo,A.P. and Owens,G.K. (2001) Smooth muscle differentiation marker gene expression is regulated by RhoA-mediated actin polymerization. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madaule P., Furuyashiki,T., Reid,T., Ishizaki,T., Watanabe,G., Morii,N. and Narumiya,S. (1995) A novel partner for the GTP-bound forms of rho and rac. FEBS Lett., 377, 243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M., Betancourt,L., Matsuzawa,T., Kashimoto,T., Takao,T., Shimonishi,Y. and Horiguchi,Y. (2000) Activation of Rho through a cross-link with polyamines catalyzed by Bordetella dermonecrotizing toxin. EMBO J., 19, 521–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarrese P., Giandomenico,V., Fiorucci,G., Rivabene,R., Straface,E., Romeo,G., Affabris,E. and Malorni,W. (1998) Antiproliferative activity of interferon α and retinoic acid in SiHa carcinoma cells: the role of cell adhesion. Int. J. Cancer, 76, 531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T. et al. (1996) Rho-associated kinase, a novel serine/threonine kinase, as a putative target for small GTP binding protein Rho. EMBO J., 15, 2208–2216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin R.F., Raso,A., Martin,R.L. and Ilett,K.F. (1991) Evidence for the existence of distinct transporters for the polyamines putrescine and spermidine in B16 melanoma cells. Eur. J. Biochem., 200, 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottahedeh J. and Marsh,R. (1998) Characterization of 101-kDa transglutaminase from Physarum polycephalum and identification of LAV1-2 as substrate. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 29888–29895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy L. et al. (1996) Identification and characterization of a versatile retinoid response element (retinoic acid receptor response element–retinoid X receptor response element) in the mouse tissue transglutaminase gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 4355–4365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaoka H., Perez,D.M., Baek,K.J., Das,T., Husain,A.M., Misono,K., Im,M.J. and Graham,R.M. (1994) Gh: a GTP-binding protein with transglutaminase activity and receptor signaling function. Science, 264, 1593–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliverio S., Amendola,A., Di Sano,F., Farrace,M.G., Fesus,L., Nemes,Z., Piredda,L., Spinedi,A. and Piacentini,M. (1997) Tissue transglutaminase-dependent posttranslational modification of the retinoblastoma gene product in promonocytic cells undergoing apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 6040–6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou H. et al. (2000) Retinoic acid-induced tissue transglutaminase and apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res., 87, 881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson H.F., Self,A.J., Garrett,M.D., Just,I., Aktories,K. and Hall,A. (1990) Microinjection of recombinant p21rho induces rapid changes in cell morphology. J. Cell Biol., 111, 1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K.L., Maudsley,S., Daaka,Y., Luttrell,L.M. and Lefkowitz,R.J. (2000) Role of endocytosis in the activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade by sequestering and nonsequestering G protein-coupled receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 1489–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin R., Lessard,M. and Zhao,C. (1995) Inorganic cation dependence of putrescine and spermidine transport in human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 1695–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redowicz M.J. (1999) Rho-associated kinase: involvement in the cytoskeleton regulation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 364, 122–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid T., Furuyashiki,T., Ishizaki,T., Watanabe,G., Watanabe,N., Fujisawa,K., Morii,N., Madaule,P. and Narumiya,S. (1996) Rhotekin, a new putative target for Rho bearing homology to a serine/threonine kinase, PKN, and rhophilin in the rho-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 13556–13560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley A.J. and Hall,A. (1992) The small GTP-binding protein rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell, 70, 389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley A.J. and Hall,A. (1994) Signal transduction pathways regulating Rho-mediated stress fibre formation: requirement for a tyrosine kinase. EMBO J., 13, 2600–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittinger K., Walker,P.A., Eccleston,J.F., Smerdon,S.J. and Gamblin,S.J. (1997) Structure at 1.65 Å of RhoA and its GTPase-activating protein in complex with a transition-state analogue. Nature, 389, 758–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt G., Sehr,P., Wilm,M., Selzer,J., Mann,M. and Aktories,K. (1997) Gln63 of RhoA is deamidated by Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor-1. Nature, 387, 725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt G., Selzer,J., Lerm,M. and Aktories,K. (1998) The Rho-deamidating cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 from Escherichia coli possesses transglutaminase activity. Cysteine 866 and histidine 881 are essential for enzyme activity. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 13669–13674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A.A.P., Govek,E.-E., Bottner,B. and Van Aelst,L. (2000) Rho GTPases: signaling, migration, and invasion. Exp. Cell Res., 261, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh U.S. and Cerione,R.A. (1996) Biochemical effects of retinoic acid on GTP-binding protein/transglutaminases in HeLa cells. Stimulation of GTP-binding and transglutaminase activity, membrane association, and phosphatidylinositol lipid turnover. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 27292–27298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh U.S., Erickson,J.W. and Cerione,R. (1995) Identification and biochemical characterization of an 80 kilodalton GTP-binding/transglutaminase from rabbit liver nuclei. Biochemistry, 34, 15863–15871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh U.S., Li,Q. and Cerione,R. (1998) Identification of the eukaryotic initiation factor 5A as a retinoic acid-stimulated cellular binding partner for tissue transglutaminase II. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 1946–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh U.So., Combs,C. and Cerione,R.A. (2001) Effects of tissue transglutaminase on retinoic acid induced cellular differentiation and protection against apoptosis in HL60 cells. J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons M. (1996) Rho family GTPases: the cytoskeleton and beyond. Trends Biochem. Sci., 21, 178–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga T., Sugie,K., Hirata,M., Morii,N., Fukata,J., Uchida,A., Imura,H. and Narumiya,S. (1993) Inhibition of PMA-induced, LFA-1-dependent lymphocyte aggregation by ADP ribosylation of the small molecular weight GTP binding protein, rho. J. Cell Biol., 120, 1529–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe G. et al. (1996) Protein kinase N (PKN) and PKN-related protein rhophilin as targets of small GTPase Rho. Science, 271, 645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N. et al. (1997) p140mDia, a mammalian homolog of Drosophila diaphanous, is a target protein for Rho small GTPase and is a ligand for profilin. EMBO J., 16, 3044–3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Zhang,Y., Derewenda,U., Liu,X., Minor,W., Nakamoto,R.K., Somlyo,A.V., Somlyo,A.P. and Derewenda,Z.S. (1997) Crystal structure of RhoA-GDP and its functional implications. Nature Struct. Biol., 4, 699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittinghofer A. and Nassar,N. (1996) How Ras-related proteins talk to their effectors. Trends Biochem. Sci., 21, 488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Lesort,M., Guttmann,R.P. and Johnson,G.V.W. (1998) Modulation of the in situ activity of tissue transglutaminase by calcium and GTP. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 2288–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]