Abstract

Electrophilic selenium catalysis has recently emerged as an attractive synthetic strategy, yet the field of enantioselective electrophilic selenium catalysis remains underdeveloped, primarily due to the scarcity of efficient chiral catalysts and limited reaction types. Herein, we disclose the design and synthesis of a series of planar chiral organoseleniums based on [2.2]paracyclophane. With these chiral organoseleniums as catalysts, we accomplish a highly enantioselective intramolecular oxidative etherification of trisubstituted olefins, providing a diverse array of optically pure chromans bearing a quaternary carbon stereocenter. The stereochemical versatility of this method enables efficient access to both product enantiomers from the same catalyst by adjusting the E/Z configurations of the olefins. Importantly, comprehensive control experiments and kinetic studies elucidate the reaction mechanism, identifying the oxidation of selenenylated cyclic ether as the likely turnover-limiting step. DFT calculations demonstrate that both steric hindrance and weak interactions play a vital role in enantioselectivity.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Asymmetric catalysis

Electrophilic selenium catalysis has recently emerged as an attractive synthetic strategy, yet the field of enantioselective electrophilic selenium catalysis remains underdeveloped, primarily due to the scarcity of efficient chiral catalysts and limited reaction types. Herein, the authors disclose the design and synthesis of a series of novel planar chiral organoseleniums based on [2.2]paracyclophane.

Introduction

Organoseleniums have been widely recognized as effective nucleophilic reagents/catalysts in organic synthesis1–7. The inherently weak electron-binding affinity of selenium atoms renders them susceptible to oxidation, with their oxidized selenium (II) cations demonstrating notable electrophilic-π-acid properties that enable efficient activation of double-bonds (Fig. 1a). Mechanistically, the electrophilic selenium cations undergo π-coordination with alkenes to form seleniranium ion intermediates, thereby enhancing the susceptibility of the alkene moiety to nucleophilic attack. Subsequent oxidation of this adduct with an exogenous oxidant generates selenium (IV) species, followed by β-elimination to restore the double bond. While this well-characterized mechanistic pathway has been extensively employed in achiral electrophilic selenium catalyzed oxidative functionalization of olefins for the construction of carbon-heteroatom bonds8–18, the development of highly efficient asymmetric versions of such processes remains a formidable challenge and thus highly desirable.

Fig. 1. Electrophilic activation of alkene with organoselenium and chiral electrophilic selenium catalysts.

a Organoselenium as electrophilic π acid to activate alkenes; b Development of chiral electrophilic selenium catalysts; c Catalyst design; d Organoselenium-catalyzed asymmetric etherification with trisubstituted olefins (this work); e Representative bioactive products bearing chiral chroman coremoiety, EWG electron-withdrawing group; PMB p-methoxybenzyl, ee enantiomeric excess.

The primary limitation stems from the severe scarcity of chiral selenium catalysts. Analyzing the key steps in electrophilic selenium catalysis reveals that the facial selectivity of selenium cations toward alkenes dictates the stereochemical outcome. However, due to the single-bond connection between the selenium atom and the chiral skeleton, the chiral framework must possess considerable steric hindrance to precisely control the orientation of the approaching alkene during π-coordination. This structural constraint imposes stringent requirements on both the magnitude and spatial arrangement of the chiral substituents to achieve effective enantioselectivity. Notwithstanding the inherent challenges, relatively few elegant examples have emerged over the past decades (Fig. 1b). While installing a chiral substituent adjacent to the selenium atom remains a widely adopted strategy for creating chiral environments through steric interactions that dictate substrate orientation during catalysis, achieving high enantiocontrol in such systems has proven challenging. Although Wirth et al. reported the synthesis of chiral organoselenium compounds, the achieved stereochemical control remains insufficient for practical applications19–26. Significant progress in chiral electrophilic selenium catalysis was marked by Maruoka’s group in 2016, which developed an indenol-based chiral selenium catalyst and achieved the highly enantioselective oxidative lactonization of unsaturated carbonyl acids27,28. Subsequently, Denmark and coworkers made notable progress by developing asymmetric electrophilic selenium-catalyzed 1,2-diamination and 1,2-hydroxyamination of alkenes, employing tetralin-based selenium catalysts29–31. Therefore, there is a critical need for the design of highly efficient and enantioselective chiral electrophilic selenium catalysts32–35.

Additionally, although good enantioselectivity has been achieved for simple alkene substrates with trans-di-substitution characteristics, studies involving cis-alkenes or multi-substituted alkenes as substrates have yielded less satisfactory results or remain unreported29,30. This phenomenon fundamentally stems from the minimal energy barrier difference between the Re and Si faces of these olefins, which makes it difficult to distinguish their chiral planes thermodynamically and kinetically effectively. The current chiral selenium catalytic systems, owing to their high conformational flexibility, exhibit insufficient spatial matching precision between the chiral centers and the substrate activation sites. Consequently, the catalytic transition state cannot sustain the stereochemical environment required for precise stereocontrol.

To address these challenges, we present a rational catalyst design centered on [2.2]paracyclophane framework. Based on our understanding of the [2.2]paracyclophane36–42, the high steric hindrance of the scaffold makes it a promising candidate for developing electrophilic selenium catalysts. Moreover, the inherent rigidity of this scaffold allows for precise orthogonal functionalization, enabling systematic modulation of both catalytic activity and enantioselectivity (Fig. 1c). To elucidate the distinctive merits of this planar chiral selenium catalytic system, we design an intramolecular reaction featuring phenol and unactivated trisubstituted alkene.

Herein, we report the development of a planar chiral organoseleniums derived from the hindered [2.2]paracyclophane framework. The efficient enantiocontrol of these organoselenium catalysts is demonstrated in the enantioselective oxidative etherification of challenging trisubstituted olefins via an oxa-6-exo-trig cyclization, delivering chiral chromans with a quaternary stereocenter at the 2-position in good enantioselectivity. Remarkably, the stereochemical versatility of this method enables efficient access to both product enantiomers from a same catalyst through olefin E/Z modulation while maintaining excellent yields and stereoselectivity (Fig. 1d). The obtained chiral chromans in a wide range of natural products and biologically active compounds (Fig. 1e)43–49, yet their enantioselective synthesis from simple alkenes is currently quite limited50–58.

Results

Catalyst synthesis

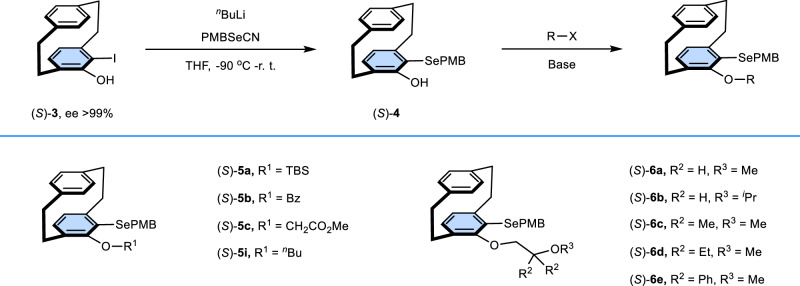

Our research initiated with the strategic development of a chiral selenium catalyst library, employing designed synthetic protocol. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the catalysts were synthesized with high efficiency and good yields from chiral 5-hydroxy-4-iodo[2.2]paracyclophane (S)-3 via a concise synthetic route59. (S)-3 was subjected to a lithium-iodine exchange reaction followed by selenenylation with PMBSeCN to yield (S)-4. After a nucleophilic substitution or acylation reaction, a series of catalysts were obtained.

Fig. 2. Preparation of planar chiral organoseleniums based on [2.2]paracyclophane.

ee enantiomeric excess, PMB p-methoxybenzyl, TBS t-butyldimethylsilyl, Bz benzoyl, THF Tetrahydrofuran, r. t. room temperature.

Reaction optimization

Next, an electrophilic selenium-catalyzed oxidative 6-exo-trig cyclization with unactivated trisubstituted alkenes and phenol nucleophiles was designed to investigate the catalytic performance of these chiral selenium catalysts. The reactions were conducted using alkene (E)-1a, with N-Fluoropyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate (PyFOTf) serving as the oxidant and NaF as the base, in acetonitrile (MeCN) at room temperature. The selected data are presented in Table 1. Initially, four selenium catalysts with different structural characteristics in the side chains were examined (entries 1–4, Table 1), and the studies revealed that the catalyst 5i containing a flexible n-butyl side chain exhibited good enantioselectivity (entry 4, 75% ee). Further research has indicated that the catalyst 6a, featuring a flexible side chain hybridized with an oxygen atom, could achieve higher enantioselectivity (entry 5, 80% ee). When the Me group of the 6a catalyst was replaced with a bulkier iPr group, a slight decrease in enantioselectivity was observed (entry 6, 73% ee). To our delight, a satisfactory enantio-selectivity emerged with catalyst 6c, which has a tertiary butyl ether structure on the catalyst’s side chain (entry 7, 92% ee); Further research indicated that Me groups are the optimal substituents (entry 7 vs. entries 8 and 9).

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditions

| entry | catalyst | derivation from condition | yield (%) | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (S)-5a | none | 44 | 50 |

| 2 | (S)-5b | none | 51 | 26 |

| 3 | (S)-5c | none | 80 | 56 |

| 4 | (S)-5i | none | 89 | 75 |

| 5 | (S)-6a | none | 87 | 80 |

| 6 | (S)-6b | none | 86 | 73 |

| 7 | (S)-6c | none | 83 | 92 |

| 8 | (S)-6d | none | 77 | 91 |

| 9 | (S)-6e | none | 75 | 81 |

| 10 | - | none | n. r. | - |

| 11 | (S)-6c | without PyFOTf | n. r. | - |

| 12 | (S)-6c | without NaF | 59 | 75 |

| 13 | (S)-6c | NaF (2.5 equiv) | 84 | 92 |

| 14 | (S)-6c | MeCN (2.0 mL) | 51 | 91 |

| 15 | (R)-6c | none | 81 | −92 |

The reactions were performed with (E)-1a (0.10 mmol), Se catalyst (0.01 mmol), PyFOTf (0.13 mmol), and NaF (0.15 mmol) in MeCN (0.5 mL) at r. t. for 12 h; Isolated yield; The ee value was determined by chiral HPLC.

PyFOTf N-Fluorpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate, ee enantiomeric excess, n. r. no reaction, r. t. room temperature.

The structure of the chiral selenium catalyst (S)-6c was confirmed unambiguously by X-ray crystallographic analysis. To gain deeper insights into the catalyst’s steric environment, we performed a quantitative analysis of the binding pocket using the SambVca 2.1 tool (Fig. 3)60,61. Structural analysis revealed that the cyclophane framework creates a well-defined steric barrier, effectively shielding the third and fourth quadrants around the selenium atom. This spatial constraint imposes strict control over olefin’s binding orientation relative to the selenium atom. Furthermore, the flexible side chain occupies the first quadrant, where it likely modulates the olefin conformation through favorable dispersion interactions. This unique spatial arrangement of steric and electronic features might contribute to the catalyst’s excellent enantiocontrol.

Fig. 3. Single X-crystal structure and steric map of (S)-6c.

a X-ray structure of (S)-6c; b steric map of (S)-6c (The steric map was generated by the SambVca 2.1 tool (Bondi radii scaled by 1.17, sphere radius 6.0 Å, mesh spacing 0.1 Å, PMB group was removed).

The subsequent investigation focused on optimizing the reaction conditions (see Table 1 and Table S1 in the Supplementary Information). The experiments demonstrated that the catalyst, oxidant, and base were crucial for the reaction (Entries 10–13). According to the ref.62, NaF was presumably used as a base to scavenge the HF generated during the reaction. This may help to ensure both the stability and catalytic performance of the catalyst within the reaction system. Other oxidant sources, such as PyFBF4 and NFSI, led to a decrease in yield and ee. Likewise, slightly decreased yields and ee were obtained when replacing NaF with other inorganic alkalis, and organic bases, such as Pyridine and Et3N, exhibited no activity. Further studies have demonstrated that the solvent exerted a substantial influence on the reaction performance. The reactions proceed smoothly to yield product 2a in dichloromethane (DCM), nitromethane (MeNO2), and acetone, albeit with an enantioselectivity marginally lower than that achieved in MeCN. Conversely, other solvents, such as tetrahydrofuran (THF), ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and aromatic solvents, exhibited no activity. Additionally, the concentration of the reaction is also vital for the reactivity of etherification; lower concentration of the reactants resulted in worse reactivity (entry 14, Table 1). Finally, the product could be obtained smoothly with 81% yield and −92% ee when catalyst (R)-6c was used in the reaction (entry 15).

Substrate scope

With the optimal conditions for electrophilic selenium-catalyzed asymmetric cyclization (Conditions of entry 7 in Table 1), the generality of the developed method was investigated. As summarized in Fig. 4, a series of 4-substituted chromans (2b-2h) was efficiently generated with good yields and enantioselectivities, including those bearing bulky, electron-donating, electron-withdrawing, and halogen substitutions. By X-ray crystallography analysis, chroman product 2 g was determined as (R)-configuration. In addition, 3- and 5-monosubstituted substrates also worked well (2i-2k). 3-methoxy-5-methyl chromans, serving as the core skeletons of many natural products, were also well-tolerated (2 l). In addition, introducing a substituent at the 2-position of the phenol or increasing the steric bulk at the alkene resulted in a decrease in enantioselectivity (2 m and 2n). Lastly, introducing an ester group as an electron-withdrawing group (EWG) did not have a significant effect on yield, but in some cases led to a slight decrease in enantiomeric excess (2o).

Fig. 4. Scope of the reaction.

The reactions were performed with (E)-1 (0.20 mmol), 6c (0.02 mmol), PyFOTf (0.26 mmol), and NaF (0.30 mmol) in MeCN (1.0 mL) at r. t. for 12 h; Isolated yield; The ee value was determined by chiral HPLC. PyFOTf N-Fluorpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate, EWG electron-withdrawing group, ee enantiomeric excess, r. t. room temperature.

Synthetic applications

To demonstrate the synthetic utility of our approach, we conducted a gram-scale reaction and extensive functional group transformations, as summarized in Fig. 5. The gram-scale reaction of 1a under optimal conditions gave almost identical results, giving product 2a in 80% yield and 92% ee. The synthetic potential of 2a was demonstrated through several representative transformations: (a) Reduction with diisobutylaluminum hydride (DIBAL-H) provided α, β-unsaturated aldehyde 7 in 65% yield with 91% ee; (b) A sequential dihydroxylation/oxidative cleavage protocol converted 2a to aldehyde 8 in 77% yield with 91% ee, which serves as a key intermediate for synthesizing chroman-type natural products; (c) The Wittig reaction of aldehyde 8 successfully afforded terminal alkene 9 in 54% yield with 92% ee; (d) Aldehyde 8 could be further reduced by sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) to yield chiral alcohol 10 with excellent yield and enantioselectivity.

Fig. 5. Gram-scale experiment and functional group transformation.

a Gram-scale synthesis; b Synthetic transformations. PyFOTf N-Fluorpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate, DIBAL-H Diisobutylaluminum hydride, NMO N-Methylmorpholine N-oxide, DCM Dichloromethane, THF Tetrahydrofuran, ee enantiomeric excess, r. t. room temperature.

Mechanism studies

To elucidate the reaction mechanism in detail, we performed a comprehensive series of control experiments and kinetic studies. Our investigation began by examining the crucial role of the cyano (CN) group in olefin 1a and the influence of the olefin geometry (Fig. 6a). When 2-(3-methylpent-3-en-1-yl)phenol (11) was employed as the substrate, the desired product was obtained in a markedly low yield ( < 10%), with a substantial amount of unreacted starting material remaining. This result strongly suggests that the presence of an electron-withdrawing group (EWG) significantly accelerates the reaction rate. We propose that this acceleration arises from the stabilization of the product through conjugation with the double bond formed after the elimination step1,63. Subsequently, we synthesized (Z)-1a and subjected it to the standard conditions, which afforded (S)-2a with 80% yield and 90% ee. This finding clearly demonstrates that the olefin geometry exerts a profound influence on the configuration of the product under identical catalytic conditions. It is worth mentioning that the reaction allows for the stereodivergent synthesis of both product enantiomers from a single catalyst enantiomer with satisfactory yields and ee by simply switching the E/Z configuration of the substrate64–66.

Fig. 6. Control experiments and mechanism studies.

a Control experiments; b Capture and Identification of Int-C; c Reaction profile; d Deuterium-labeling experiment and kinetic isotope effect studies; e kinetics studies; f Non-linear effect; g Proposed catalytic cycle, Ar* represents chiral [2.2]paracyclophane framework, PyFOTf N-Fluorpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate, Py pyridine, PMB p-methoxybenzyl, ee enantiomeric excess.

To gain deeper insights into the reaction, the kinetic studies have been examined. Based on our hypothesis that the oxidative deselenylation step might be turnover-limiting, we focused on monitoring the accumulation of intermediate selenenylated ether Int-C throughout the reaction process. Supported by the literature, the Int-C was successfully obtained in 74% yield with 0.5 equivalent oxidants, and the structure was confirmed by NMRs. (Fig. 6b). Additionally, the stereochemical properties of Int-C originate from the stereospecific anti-addition manner between selenium electrophiles and alkenes. We performed time-course analysis of substrate 1a (black squares), product 2a (red circles), and the selenium-containing intermediate Int-C (blue triangles) under standard reaction conditions. The concentration profile revealed that product 2a reached a maximum value (~85% yield) within 400 min, followed by steady-state accumulation with only residual amounts of starting material remaining ( < 10%). Notably, the selenoether intermediate exhibited concerted formation (t½ = 85 min) and long-term stability ( > 300 min), which provides critical evidence for the proposed catalytic mechanism. This temporal behavior aligns with Fig. 6c, where the persistent intermediate population facilitates continuous regeneration of the active selenium (IV) species through oxidation. The observed kinetics further underscore the essential role of the selenium oxidation step in maintaining catalytic turnover.

The oxidative deselenylation process comprises two distinct steps: (1) oxidation of Int-C by PyFOTf to generate selenium (IV) species (Int-D), followed by (2) β-elimination from Int-D. To elucidate the β-elimination mechanism, we performed kinetic isotope effect (KIE) studies. As illustrated in Fig. 6d, KIE studies revealed a negligible isotope effect (kH/kD = 1.1), indicating that the C-H bond cleavage is unlikely to be the turnover-limiting step67. These findings led us to propose that the oxidation of Int-C might be the turnover-limiting step. Further mechanistic insights were obtained through extensive kinetic studies (Fig. 6e). Rate analysis demonstrated first-order dependence on both catalyst and oxidant concentrations while showing zeroth-order dependence on olefin substrate and base concentrations. These kinetic profiles suggest that (1) the binding of electrophilic selenium species to olefins and (2) the subsequent nucleophilic attack proceed rapidly, with the oxidation step emerging as the turnover-limiting step. This conclusion is consistent with the KIE study results. Furthermore, we established a direct linear correlation between the enantiomeric purity of the products and that of the chiral catalyst (Fig. 6f), providing strong evidence that a single chiral electrophilic selenium catalyst participates in each enantiodetermining transition state68,69.

A plausible catalytic cycle was proposed (Fig. 6g). The process initiates with the oxidation of the precatalyst ArSePMB to generate electrophilic aryl-selenium species (A), which subsequently attack the olefin 1a. The formed seleniranium ion intermediate (B) was then followed by a nucleophilic attack from the phenolic hydroxyl group to afford the selenenylated ether (C). Subsequent oxidation of the selenium center yields an aryl-selenium (IV) species (D), with kinetic studies identifying this step as the turnover-limiting step. The observed steric hindrance around the selenium atom likely accounts for the elevated activation energy associated with this transformation. Finally, catalyst regeneration occurs through β-elimination of the arylselenium (IV) intermediate, releasing the active species (A) into the catalytic cycle.

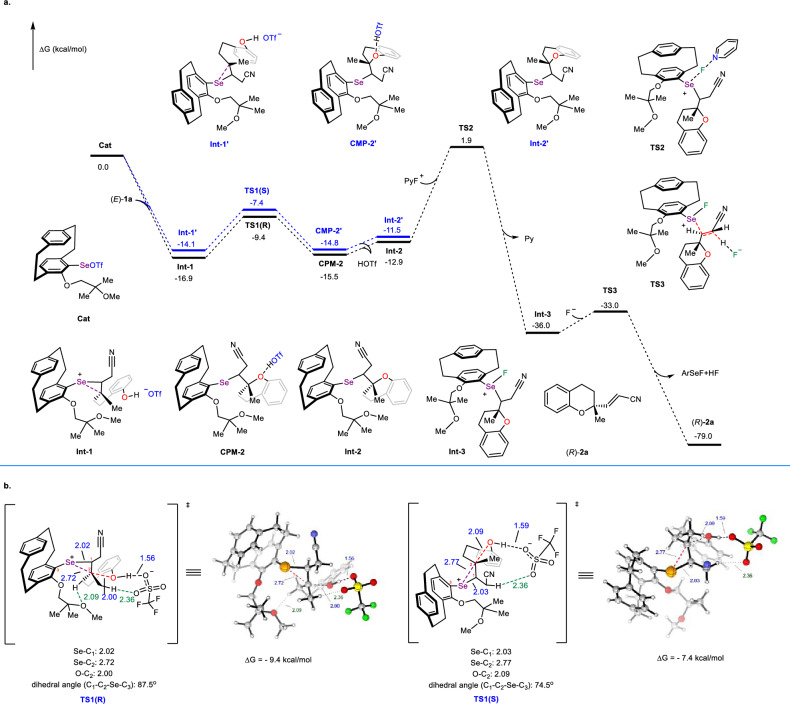

DFT calculations

To gain a better understanding of the origin of enantioselectivity and validate the turnover-limiting step of the reaction, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed (for details, see Supplementary Information; the Cartesian coordinates are provided in Supplementary Data). As shown in Fig. 7a, the reaction commenced with the activation and electrophilic addition of a selenium species, Cat, to the olefin 1a, giving rise to a pair of interconvertible seleniranium ion intermediates, Int-1 and Int-1’11,35,70. Both reaction pathways were exergonic, and no transition state was located for this step71. Notably, Int-1 exhibits a 2.8 kcal/mol energetic preference over Int-1’, underscoring its thermodynamic dominance in the reaction mechanism. Subsequently, intramolecular nucleophilic attack via transition states TS1 (R) and TS1 (S) yields selenenylated cyclic ether/trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (HOTf) complexes CMP-2 and CMP-2’. The hydrogen bonding interactions present in these HOTf complexes serve to stabilize the products. Calculations revealed that the R-configured product was favored, with a 2.0 kcal/mol lower energy barrier than its S-configured counterpart (−9.4 vs. −7.4 kcal/mol). This is highly consistent with the experimental results, which show the R-configured product as the major enantiomer. Structural analysis of transition states TS1(R) and TS1(S) revealed that: (1) the C–Se bond lengths in TS1(R) are significantly shorter than those in TS1(S) (2.02 Å vs. 2.03 Å; 2.72 Å vs. 2.77 Å) and the orbital overlap between the Se p-orbital and the olefin π-orbital is more effective (87.5° vs. 74.5°); this difference is likely attributed to the steric effects of the flexible catalyst side chains, which force TS1(S) to adopt an elongated C–Se bond and a distorted dihedral angle between the olefin and arylselenium moiety, leading to higher energy compared to TS1(R); (2) Steric repulsion further leads to a 0.09 Å elongation in the C–O bond formation distance within TS1(S) (2.09 Å vs. 2.00 Å), thereby impeding bond formation. Notably, a stabilizing C–H···O (2.09 Å) noncovalent interaction between the catalyst side chain and substrate was identified in TS1(R), further lowering its energy. These structural features collectively explain the origin of enantioselectivity in this reaction (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7. Computational studies.

a Gibbs free energies profiles; b Structures analysis of transition states. PyF+ N-fluoropyridinium cation, Py pyridine; The green and blue numbers indicate the bond lengths of the corresponding bonds, with the unit of angstrom (Å); All energies discussed relative values of Gibbs free energy under the conditions of 298.15 K and 1 atm, with the unit of kcal/mol.

Afterwards, CMP-2 dissociated to form Int-2, Int-2 underwent oxidation by PyFOTf via transition state TS2, which required overcoming a Gibbs free energy barrier of 14.8 kcal/mol to generate the active tetravalent selenium species Int-3. Finally, in the presence of a base, the reaction proceeded through transition state TS3 with a barrier of 3.0 kcal/mol, resulting in a β-elimination reaction that produced (R)-2a. Energy calculations indicated that the oxidation step had the highest energy barrier and was the turnover-limiting step of the reaction. This theoretical calculation aligns with the conclusions drawn from kinetic experiments.

Discussion

In summary, we have successfully designed and synthesized a class of planar chiral electrophilic organoseleniums. With those chiral organoseleniums as catalysts, a highly enantioselective electrophilic selenium-catalyzed intramolecular oxidative etherification of trisubstituted olefins has been developed, providing a series of chiral chromans bearing a quaternary stereocenter under mild conditions. A particularly noteworthy aspect of this approach is its stereochemical versatility, where simple modulation of the E/Z configuration of the olefin substrate enables access to both enantiomers of the product with consistently good yields and enantioselectivities. Mechanistic investigations through kinetic studies and isotope effect have unequivocally identified the selenium species oxidation step as the turnover-limiting step. DFT calculations theoretically explained the origin of enantioselectivity and verified the results of kinetic studies. Furthermore, the synthetic utility of this methodology has been demonstrated through gram-scale synthesis and versatile functional group transformations, yielding various chiral chroman derivatives. Further applications of our catalyst in other challenging transformations are underway in our lab.

Methods

General procedure for the synthesis of chiral chromans

To an oven dried tube were added with the corresponding olefin (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), Se catalyst (10.2 mg, 0.02 mmol, 10 mol%), N-Fluorpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate (PyFOTf) (64.3 mg, 0.26 mmol, 1.3 equiv.), NaF (12.6 mg, 0.30 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), dry MeCN (1.0 mL) and a stir bar. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. Then the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel with petroleum ether and ethyl acetate as eluent to provide chiral chroman products.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

Generous financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22271145) and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20242020) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

W.-H.Z. and W.Z. conceived the research. W.Z., F.-Y.F. and K.-Y.X. performed the experiments and collected the data. W.Z. performed the DFT calculations. W.-H.Z. and W.Z. wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the final editing and revision of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ren-Fei Cao and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Crystallographic data for the structures generated in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2408218 and 2418435. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All other data that support the findings of this study, which include experimental procedures, compound characterizations, and DFT calculations, are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-64327-9.

References

- 1.Wirth, T. Organoselenium Chemistry: Synthesis and Reactions (Wiley-VCH, 2011).

- 2.Mukgerjee, A. J., Zade, S. S., Singh, H. B. & Sunoj, R. B. Organoselenium chemistry: role of intramolecular interactions. Chem. Rev.110, 4357–4416 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonego, J. M., De Diego, S. I., Szajnman, S. H., Gallo-Rodriguez, C. & Rodriguez, J. B. Organoselenium compounds: chemistry and applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Eur. J.29, e202300030 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiefel, A. F. et al. Unimolecular net heterolysis of symmetric and homopolar σ-bonds. Nature632, 550–556 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.See, J. Y. et al. Desymmetrizing enantio- and diastereoselective selenoetherification through supramolecular catalysis. ACS Catal.8, 850–858 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao, R.-F. et al. Chiral sulfide and achiral sulfonic acid cocatalyzed enantioselective electrophilic tandem selenylation semipinacol rearrangement of allenols. Nat. Commun.16, 2147 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo, H.-Y. et al. Chiral selenide/achiral sulfonic acid cocatalyzed atroposelective sulfenylation of biaryl phenols via a desymmetrization/kinetic resolution sequence. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 2943–2952 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freudendahl, D. M., Santoro, S., Shahzad, S. A., Santi, C. & Wirth, T. Green chemistry with selenium reagents: development of efficient catalytic reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.48, 8409–8411 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breder, A. & Ortgies, S. Recent developments in sulfur- and selenium-catalyzed oxidative and isohypsic functionalization reactions of alkenes. Tetrahedron Lett.56, 2843–2852 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo, R., Liao, L. & Zhao, X. Electrophilic selenium catalysis with electrophilic N-F reagents as the oxidants. Molecules22, 835 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortgies, S. & Breder, A. Oxidative alkene functionalizations via selenium-π-acid catalysis. ACS Catal.7, 5828–5840 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao, L., Li, Y., Lu, J. & Jiang, X. Recent progress in selenium-catalyzed organic reactions. Org. Chem. Front.6, 2999–3041 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao, L. & Zhao, X. Modern organoselenium catalysis: opportunities and challenges. Synlett32, 1262–1268 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qu, P. & Liu, G.-Q. Recent progress in the organoselenium-catalyzed difunctionalization of alkenes. Org. Biomol. Chem.23, 1552–1568 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei, W. & Zhao, X. Organoselenium-catalyzed cross-dehydrogenative coupling of alkenes and azlactones. Org. Lett.24, 1780–1785 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan, Z., Xiang, F., Xu, K. & Zeng, C. Electrochemical organoselenium-catalyzed intermolecular hydroazolylation of alkenes with low catalyst loadings. Org. Lett.24, 5345–5350 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei, T., Appleson, T. & Breder, A. Intermolecular Aza-Wacker coupling of alkenes with azoles by photo-aerobic selenium-π-acid multicatalysis. ACS Catal.14, 9586–9593 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu, W., Liao, L., Xu, X., Huang, H. & Zhao, X. Catalytic 1,1-diazidation of alkenes. Nat. Commun.15, 3632 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita, K., Iwaoka, M. & Tomoda, S. Synthesis of diaryl diselenides having chiral pyrrolidine rings with C2 symmetry. Their application to the asymmetric methoxyselenenylation of trans-β-methylstyrenes. Chem. Lett.23, 923–926 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuzawa, S. I., Takahashi, K., Kato, H. & Yamazaki, H. Asymmetric methoxyseleneny-lation of alkenes with chiral ferrocenylselenium reagents. J. Org. Chem.62, 7711–7716 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wirth, T., Häuptli, S. & Leuenberger, M. Catalytic asymmetric oxyselenenylation-elimination reactions using chiral selenium compounds. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry9, 547–550 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiecco, M. et al. Asymmetric oxyselenenylation-deselenenylation reactions of alkenes induced by camphor diselenide and ammonium persulfate. A convenient one-pot synthesis of enantiomerically enriched allylic alcohols and ethers. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry10, 747–757 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiecco, M. et al. New nitrogen containing chiral diselenides: synthesis and asymmetric addition reactions to olefins. Tetrahedron Asymmetry11, 4645–4650 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiecco, M. et al. Preparation of a new chiral non-racemic sulfur-containing diselenide and applications in asymmetric synthesis. Chem. Eur. J.8, 1118–1124 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niyomura, O., Cox, M. & Wirth, T. Electrochemical generation and catalytic use of selenium electrophiles. Synlett2, 251–254 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Browne, D. & Wirth, T. New developments with chiral electrophilic selenium reagents. Curr. Org. Chem.10, 1893–1903 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawamata, Y., Hashimoto, T. & Maruoka, K. A chiral electrophilic selenium catalyst for highly enantioselective oxidative cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 5206–5209 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otsuka, Y., Shimazaki, Y., Nagaoka, H. & Maruoka, K. Scalable Synthesis of a Chiral Selenium π-Acid Catalyst and Its Use in Enantioselective Iminolactonization of β,γ-unsaturated amides. Synlett30, 1679–1682 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao, Z., Gilbert, B. B. & Denmark, S. E. Catalytic, enantioselective syn-diamination of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 19161–19170 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mumford, E. M., Hemric, B. N. & Denmark, S. E. Catalytic, enantioselective syn-oxyamination of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.143, 13408–13417 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham, C. C., Panger, J. L., Lupi, M. & Denmark, S. E. Organoselenium-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of 2-oxazolidinones from alkenes. Org. Lett.26, 6703–6708 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krätzschmar, F., Ortgies, S., Willing, R. Y. N. & Breder, A. Rational design of chiral selenium-π-acid catalysts. Catalysts9, 153 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi, Z.-C. et al. Electrophilic selenium-catalyzed desymme-trizing cyclization to access P-stereogenic heterocycles. ACS Catal.13, 13301–13309 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lei, T. et al. Asymmetric photoaerobic lactonization and Aza-Wacker cyclization of alkenes enabled by ternary selenium–sulfur multicatalysis. ACS Catal.13, 16240–16248 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank, E. et al. Asymmetric migratory Tsuji–Wacker oxidation enables the enantioselective synthesis of hetero- and isosteric diarylmethanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 34383–34393 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown, C. J. & Farthing, A. C. Preparation and structure of Di-p-xylylene. Nature164, 915–916 (1949).15407665 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cram, D. J. & Steinberg, H. Macro rings. I. Preparation and spectra of the paracyclophanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.73, 5691–5704 (1951). [Google Scholar]

- 38.David, O. R. P. Syntheses and applications of disubstituted [2.2]paracyclo-phanes. Tetrahedron68, 8977–8993 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hassan, Z., Spuling, E., Knoll, D. M., Lahann, J. & Bräse, S. Planar chiral [2.2]paracyclophanes: from synthetic curiosity to applications in asymmetric synthesis and materials. Chem. Soc. Rev.47, 6947–6963 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassan, Z., Spuling, E., Knoll, D. M. & Bräse, S. Regioselective functionalization of [2.2]paracyclo-phanes: recent synthetic progress and perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 2156–2170 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Felder, S., Wu, S., Brom, J., Micouin, L. & Benedetti, E. Enantiopure planar chiral [2.2]paracyclophanes: synthesis and applications in asymmetric organocatalysis. Chirality33, 506–527 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu, D. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of planar-chiral sulfur-containing cyclophanes by chiral sulfide catalyzed electrophilic sulfenylation of arenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.63, e202318625 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farrell, P. M. In Vitamin E. A Comprehensive Treatise (ed. Machlin, L. J.) (Marcel Dekker, 1980).

- 44.Grisar, J. M. et al. A cardioselective, hydrophilic N, N, N-trimethylethanaminium. alpha.-tocopherol analog that reduces myocardial infarct size. J. Med. Chem.34, 257–260 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seeram, N. P., Jacobs, H., McLean, S. & Reynolds, W. F. A prenylated benzopyran derivative from Peperomia Clusiifolia. Phytochemistry49, 1389–1391 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trost, B. M., Shen, H. C. & Surivet, J.-P. An enantioselective biomimetic total synthesis of (-) Siccanin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.42, 3943–3947 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koyama, H. et al. 2R)-2-ethylchromane-2-carboxylic acids: discovery of novel PPARα/γ dual agonists as antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic agents. J. Med. Chem.47, 3255–3263 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sekimoto, M., Hattori, Y., Morimura, K., Hirota, M. & Makabe, H. Asymmetric syntheses of daedalin A and quercinol and their tyrosinase inhibitory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.20, 1063–1064 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao, Z., Li, Y. & Gao, S. Total synthesis and structural determination of the dimeric tetrahydroxanthone ascherxanthone A. Org. Lett.19, 1834–1837 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen, H. C. Asymmetric synthesis of chiral chromans. Tetrahedron65, 3931–3952 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nibbs, A. E. & Scheidt, K. A. Asymmetric methods for the synthesis of flavanones, chromanones, and azaflavanones. Eur. J. Org. Chem.3, 449–462 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kundu, S., Bishi, S. & Sarkar, D. Introducing C2 asymmetry in chromans—a brief story. New. J. Chem.46, 12446–12455 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trost, B. M., Shen, H. C., Dong, L., Surivet, J.-P. & Sylvain, C. Synthesis of chiral chromans by the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation (AAA): scope, mechanism, and applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc.126, 11966–11983 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka, S., Seki, T. & Kitamura, M. Asymmetric dehydrative cyclization of ω-hydroxy allyl alcohols catalyzed by ruthenium complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.48, 8948–8951 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uyanik, M., Hayashi, H. & Ishihara, K. High-turnover hypoiodite catalysis for asymmetric synthesis of tocopherols. Science345, 291–294 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, P.-S. et al. Asymmetric allylic C-H oxidation for the synthesis of chromans. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 12732–12735 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayama, N. et al. Mechanistic insight into asymmetric hetero-Michael addition of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids catalyzed by multifunctional thioureas. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 12216–12225 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeon, H. et al. On the erosion of enantipurity of rhodonoids via their asymmetric total synthesis. Org. Lett.24, 2181–2185 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, Y., Yuan, H., Lu, H. & Zheng, W.-H. Development of planar chiral iodoarenes based on [2.2]paracyclophane and their application in catalytic enantioselective fluorination of β-ketoesters. Org. Lett.20, 2555–2558 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falivene, L. et al. Towards the online computer-aided design of catalytic pockets. Nat. Chem.11, 872–879 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.The geometric structures were visualized by CYLview20, Legault, C. Y., Université de Sherbrooke, 2020 (http://www.cylview.org).

- 62.Guo, R., Huang, J., Huang, H. & Zhao, X. Organoselenium-catalyzed synthesis of oxygen- and nitrogen-containing heterocycles. Org. Lett.18, 504–507 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tunge, J. A. & Mellegaard, S. R. Selective selenocatalytic allylic chlorination. Org. Lett.6, 1205–1207 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beletskaya, I. P., Nájera, C. & Yus, M. Stereodivergent catalysis. Chem. Rev.118, 5080–5200 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Massaro, L., Zheng, J., Margarita, C. & Andersson, P. G. Enantioconvergent and enantiodivergent catalytic hydrogenation of isomeric olefins. Chem. Soc. Rev.49, 2504–2522 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumari, A., Jain, A. & Rana, N. K. A review on solvent-controlled stereodivergent catalysis. Tetrahedron150, 133754 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simmons, E. M. & Hartwig, J. F. On the interpretation of deuterium kinetic isotope effects in C-H bond functionalizations by transition-metal complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.51, 3066–3072 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guillaneux, D., Zhao, S.-H., Samuel, O. & Kagan, H. B. Nonlinear effects in asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.116, 9430–9439 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Satyanarayana, T., Abraham, S. & Kagan, H. B. Nonlinear effects in asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.48, 456–494 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Denmark, S. E., Kalyami, D. & Collins, W. R. Preparative and mechanistic studies toward the rational development of catalytic, enantioselective selenoetherification reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 15752–15765 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang, X., Houk, K. N., Spichty, M. & Wirth, T. Origin of stereoselectivities in asymmetric alkoxyselenenylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc.121, 8567–8576 (1999). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Crystallographic data for the structures generated in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2408218 and 2418435. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All other data that support the findings of this study, which include experimental procedures, compound characterizations, and DFT calculations, are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request.