Abstract

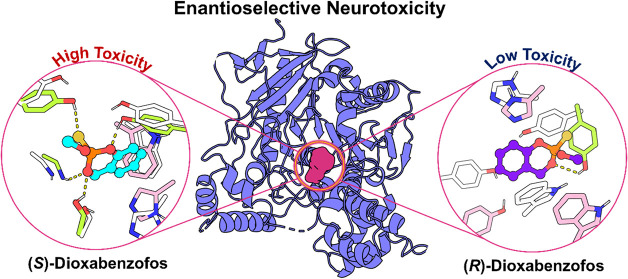

Chiral organophosphorus pollutants are widely distributed in different environmental matrices, but their health risks to humans remain insufficiently explored. This study explored the acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-mediated enantioselective neurotoxicity of dioxabenzofos on SH-SY5Y cells and elucidated the microscopic mechanisms underlying neurotoxicity at the enantiomeric level. Cellular assays exhibited that dioxabenzofos displayed significant enantioselectivity in inhibiting the intracellular AChE activity, with IC50 values of 17.2 μM and 5.28 μM, respectively, reflecting differences in bioaffinity between both enantiomers and intracellular AChE. Modes of neurotoxic action suggest that the different orientations of enantiomers enable them to form conjugated interactions and substantial hydrogen bonds with key residues, while inherent conformational dynamics and flexibility enhance the bioaffinity of (S)-dioxabenzofos toward AChE. Energy decomposition results indicated that the binding free energy (−15.43 kcal mol–1) of (R)-dioxabenzofos to AChE was larger than that of (S)-dioxabenzofos (−23.55 kcal mol–1), and key residues such as Trp-86, Tyr-124, Ser-203, Tyr-337, and His-447 at the active site were found to contribute differently to the enantioselective neurotoxic effects. Clearly, these findings provide mechanistic insights into assessing the neurotoxicity risks associated with human exposure to chiral dioxabenzofos.

Introduction

Organophosphorus chemicals play an important role in national economic construction. As flame retardants, pesticides, pharmaceutical intermediates, and plasticizers, they are extensively used in the modern industry, agriculture, and pharmaceutical industry. − Among these substances, organophosphorus pesticides are a class of chemicals that have attracted much attention. Historically, organophosphorus pesticides, especially insecticides, have been massively applied to control plant diseases and insect pests to ensure stable yields and good harvests in agricultural production. , However, due to their molecular structure, toxicity, and often irrational use, these agrochemicals have become broadly distributed in environmental media and farm produce, posing a great threat to nontarget organisms and human health. − In recent years, reports on organophosphorus poisoning have been documented worldwide. , Significantly, Wang et al. performed a statistical analysis of organophosphorus insecticides available on the market and found that 26 of the 46 commercial formulations contained asymmetric centers, accounting for 57% of the total. Usually, while different enantiomers exhibit identical physicochemical and environmental chemical properties in symmetric environments, their environmental behaviors and bioactive/biotoxic effects in chiral environments can differ markedly or may even be completely opposite, which has been evidenced by many pioneering explorations. − In agricultural production, chiral organophosphorus insecticides are marketed and used in the form of racemates, and once released in the environment, different enantiomers exhibit conspicuous enantioselective discrepancies in their physiological processes and biotoxic effects within environmental media and nontarget organisms. For example, Li et al. investigated the environmental fate of chiral fosthiazate in soil and aquatic ecosystems, and the results showed that the degradation process of fosthiazate exhibited significant enantioselectivity; additionally, (1S,3R)-fosthiazate and (1S,3S)-fosthiazate had shorter degradation half-lives in environmental matrices, while (1R,3S)-fosthiazate and (1R,3R)-fosthiazate had higher toxicity risks to the ecological environment due to their long degradation half-lives. Fang et al. studied the biodegradation of chiral isocarbophos by Cupriavidus nantongensis X1T and the environmental hazards of organophosphorus chemicals. They found that strain X1T preferentially degraded (R)-isocarbophos with a 42-fold difference in rate constant, the crude enzyme degraded the two enantiomers at the molecular level at a rate similar to that of strain X1T, and (R)-isocarbophos had a greater toxic effect on humans than (S)-isocarbophos. Furthermore, the biodegradation of chiral organophosphorus isofenphos-methyl and profenofos by strain X1T exhibited enantioselective characteristics similar to those of chiral isocarbophos. Li et al. explored the potential toxicity of chiral profenofos to humans and observed that chiral profenofos could form relatively stable noncovalent toxic conjugates with a model protein, but the bioaffinity of (R)-profenofos for protein is approximately 1.26 times that of (S)-profenofos, showing obvious enantioselectivity. Also, (R)-profenofos caused larger damage to protein structure than its antipode, indicating that (R)-profenofos poses a greater toxic threat and should be given sufficient attention when conducting toxicological risk assessment of chiral profenofos. Simultaneously, racemate is used without strict enantiomeric discrimination when conducting environmental health risk assessment on chiral organophosphorus insecticides, which would cause a large deviation between the risk evaluation results and the actual environmental hazards, decreasing the reliability of the assessment results and finally posing a huge risk to environmental safety and human health. − For this reason, only by decrypting the toxic actions of chiral organophosphorus insecticides and their corresponding microscopic basis at the enantiomeric level can we accurately evaluate the potential health threats of organophosphorus pollutants to the environment and humans.

Dioxabenzofos, 2-methoxy-4H-1,3,2-benzodioxaphosphorin 2-sulfide (structure shown in Figure ), is a commercial insecticide with a phosphorothioate group developed by Morifusa Eto of Kyushu University for control of agricultural pests and mites. Similar to traditional organophosphorus insecticides, the target receptor of dioxabenzofos is acetylcholinesterase (AChE), a cholinergic enzyme primarily found at postsynaptic neuromuscular junctions. However, interestingly, dioxabenzofos possesses a chiral center (phosphorus atom), giving rise to a pair of enantiomers; both enantiomers exhibit great differences in insecticidal activities against pests such as Musca domestica and Tribolium castaneum, which has been proved by the results of Hirashima et al. − Then, whether the environmental health impacts of the chiral organophosphorus pollutant are enantioselective remains highly ambiguous. In a few relatively recent studies, researchers found that racemic dioxabenzofos posed a large environmental risk to nontarget organisms such as willow shiner, carp, mice, rats, and humans. For example, Tsuda et al. , reported that the average bioconcentration factors of dioxabenzofos were 76 and 7.4 after 24–168 h exposure in the whole body of willow shiner and carp. Mihara and Miyamoto observed that 14C-dioxabenzofos can be rapidly absorbed by rats at 1.5 h after oral administration of 9 mg kg–1, and Matsubara and Horikoshi and Tomimaru et al. substantiated the phenomenon and further noticed that dioxabenzofos absorbed by mice and rats was difficult to be excreted from the body in a short period of time and could fully interact with key receptors such as cholinesterase to produce strong toxicity. Horiuchi et al. noted that long-term chronic exposure to dioxabenzofos can induce dermatitis in humans, and Hernández-Valdez et al. suggested that there was a suspected significant correlation between dioxabenzofos exposure, obesity, and type II diabetes mellitus mediated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Unfortunately, a literature survey indicated that only Zhou et al. studied the environmental threat of chiral dioxabenzofos using Daphnia magna as yet. The results indicated that the toxicity of (S)-dioxabenzofos to D. magna (96 h LC50) was mostly mediated by cholinesterase and was three times that of (R)-dioxabenzofos, and there was an antagonistic action between enantiomers, which explained that enantioselectivity should be fully considered when conducting a health risk assessment of dioxabenzofos. Furthermore, AChE has been verified as the key receptor mediating the neurotoxicity of racemic dioxabenzofos in mammals such as the lamb and the mouse. , However, the risk of AChE-mediated enantioselective neurotoxicity of dioxabenzofos in humans remains vague, and the microscopic mechanism behind its neurotoxicological effects has not been clarified, which is not conducive to uncovering the practical toxicological hazards of chiral dioxabenzofos, threatening human and environmental health.

1.

Molecular structures of (R)-dioxabenzofos (A) and (S)-dioxabenzofos (B).

Given the above-mentioned backgrounds, this attempt combined cellular, molecular, and computational toxicology to investigate the AChE-mediated neurotoxic effects and modes of toxic action of chiral dioxabenzofos on SH-SY5Y cells at the enantiomeric scale and further deciphered the microscopic mechanism for enantioselective neurotoxicity of dioxabenzofos. Detailed contents may be divided into the following parts: (I) study of the stereoselective toxic response of SH-SY5Y neuronal cells to dioxabenzofos enantiomers, e.g., intracellular AChE activity and half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50); (II) analysis of the profiles of enantiomeric neurotoxic action, including bioaffinity, binding domain, important residues, and key noncovalent bonds, and illumination of the biological significance of intrinsic conformational dynamics and flexibility of AChE; and (III) elaboration of the energetic basis and the conformational changes of AChE and explication of the mechanistic cause of enantioselectivity in the neurotoxicity of chiral dioxabenzofos. Evidently, the current effort aims to cast new light on the assessment of health risks such as enantioselective neurotoxicity of the environmental exposure of humans to dioxabenzofos.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Acetylcholinesterase (C2888, lyophilized powder, type V-S), dioxabenzofos (35352, analytical standard), 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (D8130, ≥98%), acetylcholine iodide (A7000, ≥97%), and dimethyl sulfoxide (D8418, ≥99.9%) were obtained from MilliporeSigma (Burlington, MA) and used without further purification. Deionized water was acquired by a Milli-Q IQ 7003 Ultrapure and Pure Water Purification System (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA). Tris (0.2 M)–HCl (0.1 M) buffer of pH 7.4, with an ionic strength of 0.1 in the presence of NaCl, and the pH was determined with an Orion Versa Star Pro Benchtop pH Meter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Dilutions of AChE stock solution (10 μM) in Tris–HCl buffer were immediately prepared before use, and the concentration of AChE was measured spectrophotometrically by using an extinction coefficient E 1cm 1% of 18.0 at 280 nm. All other chemical reagents used were of analytical grade and were received from MilliporeSigma.

SH-SY5Y Cell Culture

SH-SY5Y (CRL-2266) human neuroblastoma cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, 30-2002, ATCC) containing l-glutamine (4 mM), high glucose (25 mM), and sodium pyruvate (1 mM). This medium was supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, 30-2020, ATCC) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (P/S, 30-2300, ATCC). Cells were cultivated in T175 flasks at 37 °C with 5% CO2 at saturated humidity and maintained below ATCC passage +15 to avoid cellular senescence.

Detection of Intracellular AChE Activity

SH-SY5Y cells were collected in the maximum growth phase. The cell suspension was adjusted and inoculated in a 24-well cell culture plate at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/well, and the cell volume was 1.0 mL in each well. Then the cell culture plate was incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 at saturated humidity to make the cells adherent for 24 h. After the cells were exposed to different amounts of dioxabenzofos enantiomers, they were cultured in an incubator for 24 h. The supernatant was aspirated, and 250 μL of 0.25% trypsin solution was added; the cells were then centrifuged at 4 °C for 20 min (2800 rpm). Next, 500 μL of phosphate-buffered saline was added to the cell pellets, and the cells were suspended and sonicated by using a Q800R3 Sonicator (Qsonica, Newtown, CT) in an ice–water bath; sonicated was performed at an amplitude of 14 μm, with 15 s total treatment applied in 5 s bursts, separated by an interval of 10 s. The supernatant was used for the measurement by the AChE assay kit, and each group was measured three times after being left to stand for 15 min. The optical density (OD) of the sample was determined at a wavelength of 412 nm by using a Varioskan LUX multimode microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with an optical path of 0.5 cm, and the intracellular AChE activity can be calculated using ,

| 1 |

Docking Experiments of Chiral Dioxabenzofos to AChE

In silico testing of the AChE–dioxabenzofos enantiomer conjugations was conducted on the PowerEdge R650 Rack Server (Dell Technologies, Round Rock, TX). The crystal structure of the enzyme (entry codes 4PQE), solved at a resolution of 2.9 Å, were retrieved from the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org). After being imported in the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software package (Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Canada), the enzyme structure was optimized by using the “Structure Preparation” followed by protonation of the protein using the “Protonate 3D” default protocol. Hydrogen atoms and Gasteiger charges were computationally added and energy-minimized with the Amber10 force field with 0.01 kcal mol–1 Å–1 RMS gradient convergence criteria. − The two-dimensional structure of chiral dioxabenzofos was downloaded from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), the initial configurations of dioxabenzofos enantiomers were yielded by “Builder,” and the geometries of both enantiomers were optimized to minimum energy using “Minimize”. The lowest-energy conformer was used for the docking assays, and the semiflexible docking program, which uses the “Triangle Matcher” placement method and the London dG scoring function, was used to analyze the possible conformations of both enantiomers that bind to the enzyme. , The optimal conformations were ascertained by the GBVI/WSA dG (generalized Born volume integral/weighted surface area) scoring function, − and finally, the BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2025 Visualizer (Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France) was used for the visualization of docking results.

Calculation of Free Energies for Enantioselective Neurotoxic Processes

Binding free energies of the enzyme–dioxabenzofos enantiomers reactions were calculated by using the Amber Molecular Dynamics Package, version 23 (University of California, San Francisco, CA) based upon the molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) method, and the corresponding equations for the MM/GBSA computations are defined by

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

In these relationships, the binding free energy, ΔG bind, comprises the classical E products – E reactants (the end points), where E products = ΔG complex and E reactants is composed of G protein and G ligand. The molecular mechanics energy (E MM) comprises the van der Waals’ energy (involving the internal energy) (E vdW) and the electrostatic energy (E ele). The polar solvation component (G pol,sol) is counted by the generalized Born method. The nonpolar solvation element (G nonpol,sol) is reckoned using solvent-accessible area, with the γ parameter set to 0.00542 kcal (mol Å2)−1 and the b parameter set to 0.92 kcal mol–1. The solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) is calculated using the linear combinations of the pairwise overlaps (LCPO) model.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the mean values, standard deviations, and statistical significance were evaluated using the analysis of variance (ANOVA). The mean values were compared using Student’s t-test, and all statistical data were treated using the OriginPro data analysis and graphing software package (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA) and the powerful SPSS Statistics software platform (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results and Discussion

Intracellular AChE Activity Elicited by Chiral Dioxabenzofos in SH-SY5Y Neuronal Cells

It is generally known that organophosphorus agents are neuroactive compounds, and their neurotoxicological activity is the key factor for the decrease in the survival of nerve cells (i.e., cytotoxicity). The activity of enzymes, especially acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which decomposes neurotransmitters in nerve cells, is a crucial indicator for describing neurotoxic effects, which has been demonstrated by environmental and toxicological studies. For this reason, to investigate the neurotoxic risk of human exposure to chiral dioxabenzofos, this assay used the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y to analyze the influence of dioxabenzofos on intracellular AChE activity at the enantiomeric level and then decoded the enantioselective neurotoxic effects of chiral dioxabenzofos. The exposure concentrations of dioxabenzofos enantiomers were plotted against intracellular AChE activity, and the results are displayed in Figure (A). Obviously, compared with the control group, both enantiomers can inhibit the intracellular AChE activity (p < 0.05) of SH-SY5Y cells to varying degrees after 24 h of exposure to different concentrations of dioxabenzofos enantiomers; the AChE activity decreases with the rise of exposure concentration, and the exposure treatment with 144 μM dioxabenzofos enantiomers is the most significant. Meanwhile, the inhibition of intracellular AChE activity in SH-SY5Y showed marked enantioselectivity during the whole exposure experiment, and at the minimum exposure concentration of 1.0 μM, the inhibition of intracellular AChE activity by (R)-dioxabenzofos and (S)-dioxabenzofos reached 14.73% and 25.67%, respectively. In contrast, at the maximum exposure concentration of 144 μM, the inhibition of intracellular AChE activity by (R)-dioxabenzofos and (S)-dioxabenzofos reached 84.78% and 98.74%, respectively, inhibiting most of the activity of AChE. This phenomenon suggested that dioxabenzofos enantiomers inhibited the activity of intracellular AChE in SH-SY5Y in a dose-dependent manner, and the inhibitory capability of (S)-dioxabenzofos was stronger than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos.

2.

(A) Inhibition of intracellular AChE activity in SH-SY5Y nerve cells by exposure to different amounts of dioxabenzofos enantiomers: 0, 3.0, 9.0, 18, 36, 72, and 144 μM, respectively; red histogram, (R)-dioxabenzofos; blue histogram, (S)-dioxabenzofos. (B) Nonlinear relationships between the log(exposure concentrations of dioxabenzofos enantiomers) and the value of intracellular AChE activity in SH-SY5Y cells; (■, black square), (R)-dioxabenzofos; and (●, red circle), (S)-dioxabenzofos. Each data point was the average of three individual measurements ± SD, ranging from 1.05% to 4.35%.

According to the log[dioxabenzofos enantiomers] and the data of intracellular AChE activity, OriginPro was used to plot the correlation between the two parameters, and a nonlinear curve fitting function was used. The results are exhibited in Figure (B). As can be seen from Figure (B), the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of (R)-dioxabenzofos and (S)-dioxabenzofos on intracellular AChE in SH-SY5Y cells were 17.2 μM and 5.28 μM, respectively, indicating that (S)-dioxabenzofos has a greater inhibitory effect compared with its antipode; e.g., it has higher neurotoxicity. Enantioselectivity plays a crucial role in the AChE-mediated neurotoxic effect of chiral dioxabenzofos on SH-SY5Y cells. The conclusions are quite consistent with the enantioselective results of Zhou et al., who used an aquatic bioindicator species (D. magna) to determine the median lethal concentration (LC50) of chiral dioxabenzofos after 96 h of exposure in a relatively recent study. In a previous cellular toxicology report, Zhou et al. found that chiral organophosphorus O,S-dimethyl-N-(2,2,2-trichloro-1-methoxyethyl)phosphoramidothioate presented enantioselectivity in inhibiting the activity of intracellular AChE in SH-SY5Y cells, and the inhibitory effect was concentration-dependent. Similar stereoselective results were reported by Emerick et al. in a more recent essay on the neurotoxicity impact of methamidophos enantiomers on SH-SY5Y cells. Undoubtedly, this study not only supported the conclusions of previous investigations at the cellular level but also authenticated that chiral organophosphorus dioxabenzofos has a strong inhibitory effect on the activity of intracellular AChE in SH-SY5Y cells, with the inhibitory process showing striking enantioselectivity. The following will combine biophysical and computational toxicology under the AOP conceptual framework to in-depth analyze the molecular and atomic basis for AChE-mediated enantioselective neurotoxicity of chiral dioxabenzofos on SH-SY5Y cells.

Enantioselective Neurotoxic Response of AChE to Chiral Dioxabenzofos

As argued, the results of SH-SY5Y nerve cells explained that the enantioselective neurotoxic action of chiral dioxabenzofos is mainly mediated by AChE. For this reason, it is necessary to analyze the stereoselective toxic response of AChE to dioxabenzofos enantiomers in order to understand the intermediary role of the enzyme in the neurotoxic effect. In the current approach, we used photochemical methods to discuss the enantioselective neurotoxic reaction of AChE with chiral dioxabenzofos, and the intrinsic fluorescence intensities of Trp residues within AChE with different concentrations of dioxabenzofos enantiomers are displayed in Figure . Plainly, the maximum fluorescence emission peak of pure AChE was located at ∼344 nm, and the fluorescence intensity of the Trp residues decreased with the continuous increase of the concentrations of dioxabenzofos enantiomers, while the peak shape and peak position did not show a visible change. Under the current conditions, single dioxabenzofos enantiomers showed no fluorescence signal in the emission wavelength range of 300–500 nm and did not interfere with the detection of aromatic Trp residue fluorescence. These experimental findings stated that a strong neurotoxic reaction occurred between AChE and chiral dioxabenzofos, and dioxabenzofos enantiomers acted near the Trp residue because a unique characteristic of intrinsic enzyme fluorescence is the high sensitivity of Trp residue to its local microenvironment; this neurotoxic reaction can perturb the regional environment surrounding the indole ring, causing a significant change in the emission intensity of the fluorophore within AChE. Meanwhile, it is worth noting that the spectral effect of (S)-dioxabenzofos on AChE was remarkably larger than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos. (R)-dioxabenzofos induced a 33% decrease in the fluorescence intensity of the Trp residue at the maximum concentration of 22.5 μM, whereas (S)-dioxabenzofos reduced the fluorescence intensity of the Trp residue by 56.3%, indicating that AChE possesses great enantioselectivity in its neurotoxic response to chiral dioxabenzofos. The biological reactivity of (R)-dioxabenzofos with AChE was weaker than that of (S)-dioxabenzofos; that is, (S)-dioxabenzofos exhibited higher neurotoxic activity than (R)-dioxabenzofos.

3.

Intrinsic fluorescence intensities of AChE (2.0 μM) at pH = 7.4 and T = 298 K, plotted as a decrease of spectral intensity (F/F 0) versus (R)-dioxabenzofos (■, black square) and (S)-dioxabenzofos (●, red circle) concentrations: 0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5, 20, and 22.5 μM. Spectroscopic intensity was recorded at λex = 295 nm, and the λem maximum occurred at 344 nm. All values were corrected for dioxabenzofos enantiomers fluorescence, and each point was the mean of three separate determinations ± SD, ranging from 0.62% to 3.67%.

To further explore the quantitative characteristics of the enantiomeric neurotoxic reaction, this study used the Stern–Volmer equation to process the spectral data between AChE and chiral dioxabenzofos, and the results, exhibited as plots of F 0/F versus [enantiomers], are shown in Figure S1. Intuitively, we could see that the data of bimolecular rate constant k q is 1000-fold larger than the maximum value for the diffusion-controlled fluorescence reaction in aqueous solution (∼1010 M–1 s–1), revealing that the enantioselective toxic conjugation of AChE with chiral dioxabenzofos should be dominated by a static process with the formation of a noncovalent adduct. This conclusion is unanimous in the results of time-resolved fluorescence analysis (Supporting Information) and the emergence of a dark ground-state complex in the enantioselective neurotoxic reaction. Under this premise (τ0/τ ≈ 1), the Stern–Volmer constant could frequently be regarded as the bioaffinity of the enantiomeric toxic conjugation, and the values are 1.947 × 104 M–1 and 5.691 × 104 M–1. The bioaffinity of (S)-dioxabenzofos to AChE is 2.92 times that of (R)-dioxabenzofos, which will inevitably tempt the AChE-mediated neurotoxic effect of chiral dioxabenzofos to display enantioselective differences. Clearly, these molecular-level results illuminate the conclusions of the SH-SY5Y cell-based assay; that is, AChE can conjugate with chiral dioxabenzofos, and the neurotoxic reaction has prominent enantioselectivity, which indicates that the neurotoxicity of (R)-dioxabenzofos is weak, while that of (S)-dioxabenzofos is relatively strong.

Elaboration of Modes of Enantiomeric Neurotoxic Actions of Chiral Dioxabenzofos to AChE

To investigate the modes of enantioselective toxic action mediated by AChE of chiral dioxabenzofos on SH-SY5Y nerve cells, this study probed the residues and noncovalent bonds that play important roles in the neurotoxic reaction. Usually, it is difficult to achieve the goal using conventional experimental methods; however, computational toxicology under the AOP conceptual framework is considered to be one of the most promising alternatives, and the validity of the technique has been demonstrated by some international authoritative organizations such as the European Food Safety Authority and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. , In the present scenario, we used in silico docking embedded in the MOE software package to analyze the enantioselective neurotoxic response of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos, and the results are exhibited in Figure . As can be seen in Figure , the active site is located deep in a narrow gorge with a length of ∼20 Å and a width of ∼5.0 Å in AChE, and the domain is mainly composed of random coils and a small amount of the α-helix and has high conformational dynamics and flexibility. In the meantime, the active site is surrounded by catalytic anionic sites, peripheral anionic sites, and catalytic triads, which are primarily constituted of aromatic residues and polar residues, and they play a vital role in the hydrolysis of acetylcholine by AChE. Dioxabenzofos enantiomers act on this domain in the form of a competitive inhibitor, which will inescapably have an adverse effect on their catalytic activity, damaging the hydrolysis function of AChE. This is in accord with the recent results reported by Célerse et al., suggesting that the active site is the optimal binding domain for dioxabenzofos enantiomers in AChE. Some other organophosphorus pollutants, such as dichlorvos, ethyl paraoxon, methyl paraoxon, monocrotophos, phosphamidon, and trichlorfon, have been confirmed by previous studies to act within the domain. ,

4.

Ribbon model showing the optimal energy conformations of the AChE–dioxabenzofos enantiomer conjugates obtained from in silico docking, with chiral dioxabenzofos positioned at the active site. AChE is expressed as a multicolored surface representation, while the dioxabenzofos enantiomers are shown as ball-and-stick models, colored by atom type and overlaid with a translucent surface representing electron spin density. The aromatic residues and polar residues surrounding the active site are highlighted in green, orange, and pink stick models, respectively. This figure was generated by using PyMOL on the basis of the atomic coordinates available from the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org).

Further, the optimal energy conformations of two enantioselective neurotoxic responses were obtained, and the results are displayed in Figure . The key residues, important noncovalent bonds, and their strengths are gathered in Table . It could be seen that relative to (S)-dioxabenzofos, the conformation of (R)-dioxabenzofos is twisted by ∼180° around the fused C–C bond within the binding domain of AChE due to the presence of the asymmetric center (P atom), which indicates a pronounced difference in the patterns of neurotoxic action, with (S)-dioxabenzofos exhibiting stronger bioaffinity for AChE than (R)-dioxabenzofos, thereby driving chiral dioxabenzofos to show enantioselective neurotoxicity. Concurrently, the bioaffinities of AChE to (R)-dioxabenzofos and (S)-dioxabenzofos are observed to be 1.905 × 104 M–1 and 5.012 × 104 M–1, respectively, which is quite close to the experimental data (1.947 × 104 M–1 and 5.691 × 104 M–1), calculated by the spectrochemical technique. This phenomenon demonstrates that the studies using computational toxicology under the AOP conceptual framework to discuss the enantioselective neurotoxic responses of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos and their modes of enantiomeric toxic actions are considerably reliable. Through a detailed analysis of the neurotoxic action profile between AChE and (R)-dioxabenzofos (Figure (A)), we may see that the O atom connected to the P atom can form a hydrogen bond and a weak carbon–hydrogen bond with the H atom of the hydroxyl group in the Ser-203 residue and the tertiary methyl group of the imidazole ring in the His-447 residue in the catalytic triad, with the bond lengths of 2.84 Å and 2.9 Å, respectively. Since the P atom is near Trp-86 and His-447 residues, the S atom forms sulfur–π interactions with the two acidic residues, with distances between the S atom and the center of the indole ring of 3.64 and between the S atom and the imidazole ring of 3.98 Å. The methoxy group forms a weak alkyl–π interaction with the Trp-86 residue, and the average distance between the methyl group and the indole ring is 3.27 Å. Simultaneously, the benzene ring penetrates deep into the catalytic anionic site of AChE and forms a T-shaped π–π stacking with three acidic residues Tyr-124, Phe-295, and Tyr-337, with distances of 4.95 Å, 3.92 Å, and 4.69 Å, respectively, and the benzene ring forms an amide–π stacking with the peptide bond of polar residues Gly-121 and Gly-122, with a distance of 4.32 Å. Undoubtedly, these phenomena not only attest that the benzene ring is the key functional group that enables (R)-dioxabenzofos to act on the catalytic site of AChE but also underline that the conjugated effects play an important role in the neurotoxic reaction, as it is the crucial noncovalent bond that mediates the enantioselective bioaffinity of AChE with (R)-dioxabenzofos.

5.

Molecular docking of chiral dioxabenzofos docked to AChE. The enzyme is exhibited as a white ribbon surface, while the cyan and purple ball-and-stick models depict (S)-dioxabenzofos (panel (A)) and (R)-dioxabenzofos (panel (B)), colored by the atom type, respectively. Key residues surrounding dioxabenzofos enantiomers are illustrated as stick models, and green and pink stick models denote hydrogen bonds and conjugated effects between the residues and dioxabenzofos enantiomers, respectively. (For explanation of color references in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.).

1. Selected Noncovalent Bonds Obtained from the Docking Tests for the Enantioselective Neurotoxic Response of AChE to Chiral Dioxabenzofos.

| noncovalent bonds |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| enantioselective toxic actions | atoms of dioxabenzofos | residues | distance (Å) | scores |

| (R)-dioxabenzofos | O | –OH of Ser-203 | 2.84 | –4.28 |

| O | –CH of His-447 | 2.9 | ||

| S | indole ring of Trp-86 | 3.64 | ||

| S | imidazole ring of His-447 | 3.98 | ||

| benzene ring | benzene ring of Tyr-124 | 4.95 | ||

| benzene ring | benzene ring of Phe-295 | 3.92 | ||

| benzene ring | benzene ring of Tyr-337 | 4.69 | ||

| benzene ring | –CO–NH of Gly-121–122 | 4.32 | ||

| –CH3 | indole ring of Trp-86 | 3.27 | ||

| (S)-dioxabenzofos | –OCH3 :O | –OH of Ser-203 | 2.12 | –5.59 |

| S | –OH of Tyr-337 | 2.35 | ||

| S | benzene ring of Phe-295 | 4.87 | ||

| S | benzene ring of Tyr-337 | 5.45 | ||

| S | imidazole ring of His-447 | 5.39 | ||

| benzene ring | indole ring of Trp-86 | 4.25 | ||

| benzene ring | benzene ring of Tyr-337 | 3.73 | ||

| –OCH3:C | –NH of Gly-120 | 3.6 | ||

| –OCH3:C | –NH of Gly-121 | 3.74 | ||

| –OCH3:H | –CO of Gly-122 | 3.34 | ||

Still, discussing the profile of neurotoxic action between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos (Figure (B)), we can find that there is a distinct difference with (R)-dioxabenzofos. The P atom is located near the catalytic triad in AChE, and the groups or atoms connected to the P atom tend to form electrostatic interactions with the surrounding polar residues. For example, the O atom and the S atom of the methoxy group form hydrogen bonds with the H atom of the hydroxyl group in Ser-203 and Tyr-337 residues, with bond lengths of 2.12 and 2.35 Å, respectively. The methyl moiety of the methoxy group penetrates into the oxyanion hole formed by Gly-120, Gly-121, and Gly-122 residues, and the C atom and the H atom of the methyl group produce weak carbon–hydrogen bonds with the amino groups in Gly-121 and Gly-122 residues and the carbonyl group in Gly-122 residue, with the bond lengths of 3.6 Å, 3.74 Å, and 3.34 Å, respectively. The S atom is located near the aromatic residues in the binding domain, and the divalent S atom forms sulfur–π interactions with the benzene ring in Phe-295 and Tyr-337 residues and the imidazole ring in the His-447 residue, with the distances of 4.87, 5.45, and 5.39 Å, respectively. The benzene ring of (S)-dioxabenzofos is located between Trp-86 and Tyr-337 residues, forming a parallel π–π interaction with the two acidic residues at distances of 4.25 and 3.73 Å, respectively. This “sandwich-type” π–π stacking is very propitious for promoting the bioaffinity between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos, which has been evidenced by previous results reported elsewhere. There are strong hydrophobic functional groups such as alkyl, hexa-heterocycle, and benzene ring in dioxabenzofos enantiomers, which generate a hydrophobic effect with the residues, e.g., Gly-82, Thr-83, Ala-204, Phe-297, Phe-338, and Ile-451, in the nonpolar region of the binding domain of AChE. As a result, the chiral center (P atom) can trigger a perceptible difference in the neurotoxic action mode between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos in contrast to (R)-dioxabenzofos; that is, the conjugated effects are dominant in the neurotoxic action profile between AChE and (R)-dioxabenzofos, while the functional group connected to the P atom in (S)-dioxabenzofos makes stable hydrogen bonds with the polar residues in the active site, driving electrostatic interactions to play a major role in the neurotoxic action profile between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos.

Obviously, according to the computational toxicological analysis under the AOP conceptual framework, it could be found that the overall noncovalent bond between (S)-dioxabenzofos and AChE is greater than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos during the neurotoxic action, especially the number and strength of hydrogen bonds, which is paramount to elevate the bioaffinity of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos. Previous results have shown that the Ser-203 residue in the catalytic triad is critical in mediating the hydrolysis of acetylcholine by AChE. Under this premise, we noticed that a strong hydrogen bond was formed between the functional group connected to the P atom in (S)-dioxabenzofos and the Ser-203 residue, which enabled (S)-dioxabenzofos to act stably on the active site in AChE and interfere with the binding of the Ser-203 residue to acetylcholine in the form of a competitive inhibitor, affecting the hydrolysis function of AChE and making (S)-dioxabenzofos display a stronger neurotoxic action. Undoubtedly, the differences in the details of the toxic effects are important reasons for the pronounced disparities in the enantioselective bioaffinity of AChE in response to chiral dioxabenzofos and lead to different degrees of inhibition of intracellular AChE activity (i.e., neurotoxic effect) by dioxabenzofos enantiomers on the SH-SY5Y nerve cells.

Effects of AChE’s Conformational Dynamics and Flexibility on the Stereoselective Neurotoxicity of Chiral Dioxabenzofos

In fact, biochemical processes such as neurotoxic reactions are inherently dynamic in the body, and investigating these physiological and pathological behaviors from a dynamic level can elucidate their intrinsic essence. Concurrently, it is believed that the function of an enzyme is determined by its conformation, and conformational changes decide its biological functions such as catalysis and hydrolysis. Enzyme conformation is not completely rigid, and instead, they have a high degree of inherent flexibility, as demonstrated by several previous reports. , However, the biological significance of enzyme conformational flexibility has not yet been fully clarified. This urges us to consider the conformational dynamics and flexibility of the enzyme when studying biological events to analyze the hidden mysteries of pharmacological and toxicological effects in organisms. As a result, this experiment used atomic-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to examine the enantioselective neurotoxic response of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos and scrutinize the impact of AChE’s inherent conformational dynamics and flexibility on the enantioselective neurotoxic effect of chiral dioxabenzofos. According to the results of in silico analysis, this study selected the dioxabenzofos enantiomer conformations with the highest total score as the initial conformations, and the MD simulation was run for 200,000 ps. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) trend of the Cα skeleton structure of AChE and dioxabenzofos enantiomers is displayed in Figure S2. Generally, when the RMSD of a neurotoxic reaction fluctuates stably within a small amplitude (0.1 nm), it could be considered that the toxic reaction has reached a dynamic equilibrium state. As can be seen from Figure S2, the RMSD of the neurotoxic reaction of AChE with (R)-dioxabenzofos yielded a large fluctuation at the beginning of the reaction and reached equilibrium at the time point of ∼50,000 ps, with an average RMSD of ∼0.23 nm. In contrast, the RMSD of the neurotoxic reaction of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos began to fluctuate less than 0.1 nm at the time point of ∼10,000 ps and finally stabilized at ∼0.19 nm, with the average RMSD being slightly lower than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos, suggesting that the toxic reaction could quickly reach the equilibrium state.

In the meantime, this study calculated the radius of gyration (Rg) of AChE in the enantioselective neurotoxic response and compared it with that of pure AChE in order to study the impact of dioxabenzofos enantiomers on the conformation of AChE, and the results are exhibited in Figure S3. Evidently, the average Rg value of the neurotoxic reaction of AChE and (R)-dioxabenzofos is 2.33 nm, which is higher than the Rg value of pure AChE (2.304 nm), indicating that the conjugation of (R)-dioxabenzofos can cause the structure of AChE to become looser. In contrast, the average Rg value of the neurotoxic reaction between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos is 2.29 nm, indicating that the conjugation of (S)-dioxabenzofos near the catalytic triad could make the AChE structure more compact, which plays an important role in heightening the bioaffinity of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos. Thus, the results of RMSD and Rg testified that the neurotoxic reactions of AChE with dioxabenzofos enantiomers could generate different degrees of perturbation on enzyme conformation, and the neurotoxic conjugation of (R)-dioxabenzofos at the active site increases the conformational instability of AChE compared with (S)-dioxabenzofos, which is in accordance with the weak neurotoxic activity of (R)-dioxabenzofos on AChE derived from the SH-SY5Y nerve cell-based assays and photochemical conclusions.

The average conformations of AChE and dioxabenzofos enantiomers in the time range of 100,000–200,000 ps in the equilibrium state were selected and superimposed with the initial conformations to facilitate the analysis of the conformational changes of AChE and dioxabenzofos enantiomers during the enantioselective neurotoxic reaction, and the superposition results are shown in Figure . Clearly, the hydrogen bond between the Ser-203 residue and (R)-dioxabenzofos is difficult to exist stably (Figure (A)), triggering the P atom and the connected functional group to produce a large conformational displacement in the active site of AChE relative to the initial conformation. The O atom formed a hydrogen bond with the H atom of the hydroxyl group in Tyr-337 residue, with a bond length of 2.56 Å. The sulfur–π interaction formed between the S atom and Trp-86 residue was changed into a sulfur–π interaction between the S atom and Tyr-337 residue, with a distance of 3.74 Å. The benzene ring of (R)-dioxabenzofos flipped by ∼90°, and the residues at the catalytic anionic site and the oxyanion hole shifted away from the binding location of dioxabenzofos enantiomers, engendering the T-shaped π–π stacking between the benzene ring and three residues (i.e., Tyr-124, Phe-295, and Tyr-337) and the amide–π stacking between the benzene ring and Gly-121 and Gly-122 residues to disappear simultaneously; a π–π stacking interaction formed between the benzene ring and Trp-86 residue, with a distance of 4.98 Å. We conclude that the conformation of (R)-dioxabenzofos undergoes a large displacement, and the toxic conjugation of (R)-dioxabenzofos induces a perturbation of the residues’ conformation at the catalytic site in AChE, which in turn decreases the conjugated effects of AChE in the neurotoxic response to (R)-dioxabenzofos.

6.

Superposition of the average conformations of MD simulations on the initial conformations of molecular docking resulting from the enantioselective neurotoxic conjugations of the AChE–dioxabenzofos enantiomers: panel (A) (S)-dioxabenzofos; and panel (B) (R)-dioxabenzofos). The initial and average conformations of dioxabenzofos enantiomers are represented in white and cyan and purple ball-and-stick models, respectively. The critical residues around dioxabenzofos enantiomers are shown in stick models, and white and green and pink stick models indicate initial and average conformations of the residues in panels (A) and (B), respectively. (For clarification of color references in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.).

Likewise, the conformation of (S)-dioxabenzofos shifted to a certain extent during the neurotoxic reaction of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos (Figure (B)) because the group connected to the P atom is near the catalytic triad, and the residues such as Tyr-124, Ser-203, Glu-202, and His-447 in this domain can displace the polar groups in (S)-dioxabenzofos, enhancing the intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Concretely, the O atom formed hydrogen bonds with the H atom of the secondary amino group in the Gly-121 residue and the H atom of the hydroxyl group in the Ser-203 residue, with the bond lengths of 2.63 and 1.95 Å, respectively. Owing to the conformational change of (S)-dioxabenzofos, the hydrogen bond between the S atom and the Tyr-337 residue was broken in the initial conformation, and the S atom formed a hydrogen bond and sulfur–π interaction with the H atom of the hydroxyl group and the benzene ring in the Tyr-124 residue, with the bond lengths of 2.61 Å and 3.61 Å, respectively. The O atom and the methyl group of the methoxy group formed a hydrogen bond and sigma–π stacking with the H atom of the hydroxyl group and the benzene ring in the Tyr-337 residue, with the bond lengths of 2.03 and 3.47 Å, respectively. Furthermore, the benzene ring of (S)-dioxabenzofos penetrated into the hydrophobic cavity formed by the aromatic residues and made a hydrophobic effect with these residues; in the meantime, the benzene ring formed a T–π stacking with the indole ring in the Trp-86 residue and the benzene ring in the Tyr-337 residue, with the distance decreasing from 4.25 and 3.73 Å to 3.34 and 3.12 Å, respectively. The benzene ring formed a T-shaped π–π stacking with the imidazole ring in the His-447 residue, with a distance of 4.38 Å. Undoubtedly, the changes in these conjugated effects demonstrated that the overall strength of the van der Waals force exhibited an upward trend during the neurotoxic response of AChE to (S)-dioxabenzofos.

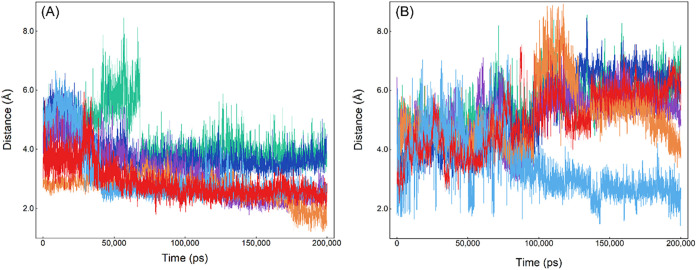

This study analyzed the changes in the distance of the noncovalent bonds between AChE and chiral dioxabenzofos in order to verify the stability of the neurotoxic conjugate and whether the important noncovalent bonds acquired by in silico docking could be stably present in the dynamic neurotoxic reaction, and the results are shown in Figure and Table . As can be seen from Figure , the hydrogen bond between (R)-dioxabenzofos and the Ser-203 residue disappeared and converted into a hydrogen bond with the Tyr-337 residue, with an average bond length of 2.63 Å, due to the conformational flip of (R)-dioxabenzofos and the conformational change of AChE. The conjugated effects between (R)-dioxabenzofos and aromatic residues near the catalytic site were shortened, whereas the noncovalent bonds between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos were relatively stable; the number and strength of hydrogen bonds increased, and the conjugated effects between (S)-dioxabenzofos and acidic residues such as Trp-86, Tyr-337, and His-447 showed a strengthening trend. This not only matches the results of the conformational superposition analysis very well but also underscores the key role of hydrogen bonds in mediating the enantioselective neurotoxic response of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos. Compared with (R)-dioxabenzofos, the number and strength of hydrogen bonds formed between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos were greater, which may cause a compact conformation of the AChE domain and prompt an increase in the conjugated effects. It can be seen that the changes in the noncovalent bonds and strengths between AChE and dioxabenzofos enantiomers are quite different, and AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos produce stronger and stable noncovalent bonds, which makes AChE display a higher bioaffinity for (S)-dioxabenzofos, triggering enantioselective differences in the neurotoxic effects of chiral dioxabenzofos. This issue is reflected in the SH-SY5Y nerve cell-based assay; that is, (S)-dioxabenzofos has a stronger inhibitory effect on the activity of intracellular AChE compared with its antipode, (R)-dioxabenzofos.

7.

Fluctuation of the distance between the residues around the binding location and the atoms or groups of dioxabenzofos enantiomers: (panel A) (S)-dioxabenzofos and (panel B) (R)-dioxabenzofos). Panel (A): red line, Gly-121–H--O; blue line, Tyr-124–H--S; orange line, Ser-203–H--O; purple line, Tyr-337–H--O; dark blue line, Trp-86–indole ring--benzene ring; green line, His-447–imidazole ring--benzene ring; and panel (B): red line, Ser-203–H--O; blue line, Tyr-337–H--O; orange line, Trp-86–indole ring--benzene ring; purple line, Tyr-124–benzene ring--benzene ring; dark blue line, Tyr-337–benzene ring--benzene ring; green line, His-447–imidazole ring--benzene ring.

2. Selected Noncovalent Bonds Formed during the Dynamic Enantiomeric Neurotoxic Reaction of AChE with Chiral Dioxabenzofos.

| noncovalent bonds |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| enantioselective toxic actions | atoms of dioxabenzofos | residues | distance (Å) | binding free energy (kcal mol–1) |

| (R)-dioxabenzofos | O | –OH of Tyr-337 | 2.56 | –15.43 |

| S | benzene ring of Tyr-337 | 3.74 | ||

| benzene ring | indole ring of Trp-86 | 4.98 | ||

| –CH3 | indole ring of Trp-86 | 3.27 | ||

| –CH3 | benzene ring of Tyr-337 | 4.31 | ||

| (S)-dioxabenzofos | O | –OH of Tyr-337 | 2.03 | –23.55 |

| O | –NH of Gly-121 | 2.63 | ||

| O | –OH of Ser-203 | 1.95 | ||

| S | –OH of Tyr-124 | 2.61 | ||

| S | benzene ring of Tyr-124 | 3.61 | ||

| benzene ring | indole ring of Trp-86 | 3.34 | ||

| benzene ring | benzene ring of Tyr-337 | 3.12 | ||

| benzene ring | imidazole ring of His-447 | 4.38 | ||

| –CH3 | benzene ring of Tyr-337 | 3.47 | ||

Yet, to investigate the changing characteristics of the enzyme’s intrinsic conformational flexibility, this study used root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) and secondary structure components to comparatively analyze the conformational differences and stability changes of the same residues in pure AChE and the neurotoxic conjugates formed between AChE and dioxabenzofos enantiomers at equilibrium because RMSF could depict the difference in atomic positions matching the equilibrium conformation and the initial conformation of the enzyme, revealing the dynamic changes in flexibility. , According to the MD simulation data, the RMSF values of two enantioselective neurotoxic responses were obtained and compared with the RMSF value of pure AChE, and the results are shown in Figure . Evidently, the neurotoxic conjugation of dioxabenzofos enantiomers reduced the α-helix from 36.9% to 33.1% and 36%, while the random coil increased from 22.6% to 27.3% and 23.5% (Table S1), respectively. Because α-helix is one of the main forms of enzyme secondary structure generated by hydrogen bonds between amino acid residues, the magnitude of its content can reflect the overall conformational stability of the neurotoxic conjugate. The conjugation of (R)-dioxabenzofos in the active site broke the hydrogen bonds between the residues that form the α-helix, transforming it into a flexible random coil. Compared with (S)-dioxabenzofos, (R)-dioxabenzofos produced a perturbation to the conformation of AChE, and this result is in line with the subsequent circular dichroism assay that the conformation of AChE was disturbed by (R)-dioxabenzofos.

8.

Panel (A) Secondary structure constituents of AChE, and blue, red, and green histograms indicate the AChE–(S)-dioxabenzofos conjugates, AChE–(R)-dioxabenzofos adducts, and pure AChE, respectively. Panel (B) RMSF of the backbone of each residue atomic position for the unbound and bound AChE as a function of the atom location along the polypeptide chain; the color of each dashed-dotted line corresponds to panel (A).

At the same time, it may be seen from Figure (B) that the overall RMSF value of the neurotoxic conjugation of AChE with dioxabenzofos enantiomers is stronger than that of pure AChE, suggesting that the enantioselective neurotoxic action could cause different degrees of perturbation to the enzyme’s conformation, and we can observe that the overall RMSF value of the neurotoxic response of AChE to (R)-dioxabenzofos is larger. Combined with the results of Rg and secondary structure components, it is considered that the conjugation of (R)-dioxabenzofos induced the conformation of AChE to be more loose. Residues such as Trp-86, Tyr-124, and Tyr-337 at the active site underwent a large displacement, and the RMSF values were 3.23, 3.77, and 2.64 Å, respectively, which are much higher than those of the same residues in the neurotoxic reaction of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos, with RMSF values of 2.24, 2.32, and 1.93 Å, respectively. This proves from the conformational level that it is difficult for the aromatic residues at the active site to form stable π–π stacking or T–π stacking with the benzene ring in (R)-dioxabenzofos, decreasing the strength of the conjugated effects between AChE and (R)-dioxabenzofos. However, during the neurotoxic response of AChE to (S)-dioxabenzofos, residues Gly-121 and Ser-203 at the active site exhibited lower RMSF values of 2.17 and 2.1 Å, respectively. In conjunction with the results of the conformational superposition analysis, it was found that the secondary amino group and hydroxyl group in the two polar residues displayed a trend of displacement toward (S)-dioxabenzofos, confirming that the two residues could form stable hydrogen bonds with (S)-dioxabenzofos. Further, the functional group that is connected to the P atom and has large electronegativity in (S)-dioxabenzofos produced hydrogen bonds with the surrounding aromatic residues such as Tyr-124 and Tyr-337, which can stabilize the conformation of AChE to a certain extent, enhancing the conjugated effects and elevating the bioaffinity of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos. These phenomena stated that the discrepancies in noncovalent bonds between chiral dioxabenzofos and the residues near the active site were crucial factors that trigger enantioselectivity in neurotoxic responses and were largely affected by the inherent conformational flexibility of the enzyme. (S)-dioxabenzofos formed stable hydrogen bonds with residues such as Tyr-124, Ser-203, and Tyr-337 at the active site, enhancing the overall stability of the conformation of AChE; in the meantime, strong hydrogen bonds could induce the increase of π–π stacking or T–π stacking, boosting the bioaffinity of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos relative to (R)-dioxabenzofos.

Plainly, from the results of the dynamic enantioselective neurotoxic response of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos, it can be found that the intrinsic conformational flexibility of the enzyme has a great impact on the enantiomeric neurotoxic action, particularly reflected in the important residues and their noncovalent bonds around the binding patch of dioxabenzofos enantiomers, causing the overall instability of the conformation of the residues in the neurotoxic reaction of AChE with (R)-dioxabenzofos to be higher than that in the neurotoxic reaction of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos. Or, more exactly, the impact of enzyme’s conformational dynamics and flexibility on the neurotoxic action of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos was weaker than that on the neurotoxic action of AChE with (R)-dioxabenzofos; however, interestingly, significant changes in the conformations of AChE and (R)-dioxabenzofos did not lead to a rise in the bioaffinity between them, and instead made the neurotoxic conjugation of AChE with (R)-dioxabenzofos to present a weakening trend, which in turn enable chiral dioxabenzofos to exhibit an enantioselective difference in the inhibition of AChE activity in the SH-SY5Y nerve cells. Undoubtedly, these conclusions not only substantiate that the results of the modes of enantioselective neurotoxic action are quite reasonable but also interpret the fundamental cause of enantioselectivity in the AChE-mediated neurotoxic effect of chiral dioxabenzofos on SH-SY5Y nerve cells at the dynamic scale.

Understanding the Energetic Basis for the Enantiomeric Neurotoxic Processes between Chiral Dioxabenzofos and AChE

According to the RMSD data, this study used the MM/GBSA method to perform energy decomposition (time interval: 2.0 ps) on the MD trajectory in the initial time range of 0–10,000 ps and the last 40,000 ps of the equilibrium state to obtain the specific energy components of enantioselective neurotoxic response of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos, and the results are collected in Table . It is obvious from Table that there is no remarkable difference in the binding free energy of AChE with (R)-dioxabenzofos and (S)-dioxabenzofos in the initial stage of the neurotoxic action, and the values were −19.01 ± 0.04 and −20.20 ± 0.06 kcal mol–1, respectively, suggesting that the toxic response of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos has not yet shown enantioselectivity. The benzene ring in (R)-dioxabenzofos penetrated into the catalytic anionic site of AChE, resulting in the van der Waals force of the neurotoxic reaction being slightly stronger than that of its antipode. As the toxic reaction proceeded, we observed that the binding free energy between (S)-dioxabenzofos and AChE (−23.55 ± 0.17 kcal mol–1) was weaker than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos (−15.43 ± 0.12 kcal mol–1) at equilibrium, with an energy difference of ΔE = 8.12 kcal mol–1, indicating that the bioaffinity of (S)-dioxabenzofos with intracellular AChE is larger than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos and induces enantioselective differences in the neurotoxic effect of chiral dioxabenzofos, which agrees with the results from photochemical assays and molecular docking studies.

3. Decomposition of Free Energies (kcal mol–1) of the Enantioselective Neurotoxic Response of AChE to Chiral Dioxabenzofos via the MM/GBSA Approach.

| enantioselective toxic actions | ΔG vdW | ΔG ele | ΔG MM | ΔG pol,sol | ΔG nonpol,sol | ΔG sol | ΔG bind |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (R)-dioxabenzofos (0∼10,000 ps) | –32.98 ± 0.15 | –22.69 ± 0.1 | –55.67 ± 0.09 | 39.71 ± 0.06 | –3.05 ± 0.01 | 36.66 ± 0.06 | –19.01 ± 0.04 |

| (S)-dioxabenzofos (0∼10,000 ps) | –30.08 ± 0.14 | –24.61 ± 0.07 | –54.69 ± 0.07 | 37.86 ± 0.11 | –3.37 ± 0.01 | 34.49 ± 0.06 | –20.20 ± 0.06 |

| (R)-dioxabenzofos (last 40,000 ps) | –28.58 ± 0.19 | –20.44 ± 0.55 | –49.02 ± 0.54 | 37.02 ± 0.41 | –3.43 ± 0.02 | 33.59 ± 0.27 | –15.43 ± 0.12 |

| (S)-dioxabenzofos (last 40,000 ps) | –32.02 ± 0.16 | –27.01 ± 0.41 | –59.03 ± 0.38 | 38.75 ± 0.24 | –3.27 ± 0.01 | 35.38 ± 0.37 | –23.55 ± 0.17 |

Through a detailed analysis of the energy components in the enantioselective toxic reactions, we found that the electrostatic contribution (ΔG ele), van der Waals contribution (ΔG vdW), and nonpolar solvation contribution (ΔG nonpol,sol) promote the stereoselective neurotoxic reactions, whereas the electrostatic solvation free energy (ΔG pol,sol) is believed to be disadvantageous to the enantioselective toxic action. Meantime, the energy values of the electrostatic contribution (ΔG ele) between AChE and (R)-dioxabenzofos and between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos were −20.44 ± 0.55 kcal mol–1 and −27.01 ± 0.41 kcal mol–1, respectively, and there was a large difference between the two values (ΔE = 6.57 kcal mol–1), denoting that hydrogen bonds have different energy contributions to the two enantiomeric neurotoxic reactions. Strictly speaking, the formation of hydrogen bonds primarily arises from attractive electrostatic interactions between a hydrogen atom and an electron-rich atom; accordingly, electrostatic energy can be employed to elucidate the enantioselective toxic interactions of AChE with chiral dioxabenzofos. By comparing the energy component data of the neurotoxic reaction at the initial stage and after equilibrium, it could be found that the hydrogen bonds and conjugated effects underwent notable changes between the two toxic reactions; in particular, the average conformation after dynamic equilibrium exhibited that the hydrogen bonds formed between the active-site residues and dioxabenzofos enantiomers differed significantly from those in the initial conformation, which is in line with the previously described modes of enantioselective neurotoxic action. This event originated from the conformational change of AChE during the toxic reaction. On the basis of the analyses of Rg, RMSF, and secondary structure components, we can see that the conjugation of (R)-dioxabenzofos in the active site evokes complete conformational change in AChE compared with its antipode, the electrostatic contribution (ΔG ele) is weaker, and they are negatively correlated, testifying that the inherent conformational flexibility of the enzyme plays an important role in the stereoselective toxic response.

Further, the energy values of van der Waals contribution (ΔG vdW) between AChE and (R)-dioxabenzofos and (S)-dioxabenzofos were −28.58 ± 0.19 kcal mol–1 and −32.02 ± 0.16 kcal mol–1, respectively, and the energy difference was ΔE = 3.44 kcal mol–1, implying that van der Waals contribution (ΔG vdW) is critical and has a large energy contribution in the enantioselective neurotoxic reactions; the difference in binding free energy mainly comes from the van der Waals contribution (ΔG vdW) and the electrostatic contribution (ΔG ele). This energy feature is reflected in the strong conjugated effects in the toxic reaction of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos, especially the quite stable “sandwich-type” π–π stacking. However, the key conjugated effects are unstable in the neurotoxic response of AChE to (R)-dioxabenzofos, which is consistent with the total change trend of the conjugated effects obtained from the dynamic experiment; namely, the conjugated effects presented a weakening trend in the toxic reaction of AChE with (R)-dioxabenzofos, whereas the conjugated effects displayed an increasing trend in the neurotoxic reaction of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos. For solvation free energies, they have almost a parallel influence on the binding free energy of the stereoselective toxic response. Obviously, these energy-scale results revealed the important reason why the enantioselective neurotoxic reactions of AChE with chiral dioxabenzofos show different bioaffinities; that is, (S)-dioxabenzofos has a stronger toxic reactivity to AChE compared with (R)-dioxabenzofos. In other words, the bioaffinity of (S)-dioxabenzofos with AChE is higher than that of its antipode; simultaneously, as a competitive inhibitor, the patterns of stereoselective toxic action suggest that (S)-dioxabenzofos has a greater inhibitory effect on intracellular AChE activity, which is coincident with the conclusions of the SH-SY5Y nerve cell-based assay.

Still, through the analyses of the enantioselective neurotoxic response at both static and dynamic scales, we conducted an in-depth discussion on the conformational changes and stability of the crucial residues around the binding domain of dioxabenzofos enantiomers in AChE. In the meantime, this experiment explored the interaction energies of important residues within 6.0 Å of the exact binding position in the narrow gorge of AChE to obtain energy contribution characteristics, clarifying the differences in the profiles of stereoselective toxic action at the amino acid energy level. Figure displays the interaction energies between the residues that can form noncovalent bonds with dioxabenzofos enantiomers, and the red and blue histograms represent the interaction energy data of (R)-dioxabenzofos and (S)-dioxabenzofos, respectively. Clearly, the residues that form hydrogen bonds and conjugated effects with dioxabenzofos enantiomers showed smaller interaction energies, and the overall energy of the residues in the toxic reaction of (S)-dioxabenzofos with AChE was weaker than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos, indicating that (S)-dioxabenzofos could form stronger noncovalent bonds with the residues at the active site. This verifies that the conclusions with respect to the residues that form hydrogen bonds and conjugated effects play a key role in the stereoselective neurotoxic reaction are reasonable. As shown in Figure , the Tyr-337 residue exhibited the lowest interaction energies in both enantiomeric toxic reactions, and the values were −3.27 kcal mol–1 and −4.55 kcal mol–1, respectively, which is reflected in the changes in hydrogen bonds and conjugated effects during enantioselective neurotoxic reactions; that is, a hydrogen bond (2.56 Å) and sulfur–π interaction (3.74 Å) were newly formed between the Tyr-337 residue and (R)-dioxabenzofos, while a hydrogen bond (2.03 Å) and sigma–π stacking (3.47 Å) were newly generated between the aromatic residue and (S)-dioxabenzofos, with the strength of T–π stacking increasing, proving that the Tyr-337 residue is important in the stereoselective toxic response of AChE to dioxabenzofos enantiomers.

9.

Per-residue free energy decompositions of enantioselective neurotoxic responses of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos. The residues contributing principally to (S)-dioxabenzofos and (R)-dioxabenzofos are represented by blue and red histograms, respectively.

Furthermore, we observed that the interaction energies of Gly-120, Gly-121, and especially Ser-203 residues in the catalytic triad differed during the enantioselective neurotoxic reaction; for example, the interaction energy between the Ser-203 residue and (R)-dioxabenzofos was −4.3 kcal mol–1, which was higher than the interaction energy (−1.38 kcal mol–1) between the polar residue and (S)-dioxabenzofos. The phenomenon is mainly due to the difference in noncovalent bonds triggered by the different conformational changes of both enantiomers in the active site of AChE. Or, more exactly, owing to the displacement in the conformation of (R)-dioxabenzofos, the hydrogen bond between the Ser-203 residue and (R)-dioxabenzofos became weakened or even disappeared; however, because the polar group in (S)-dioxabenzofos shifted toward the catalytic triad, the hydrogen bond between the Ser-203 residue and (S)-dioxabenzofos became strengthened, and the bond length shortened from 2.12 Å to 1.95 Å. Previous studies have shown that the Ser-203 residue is critical in the physiological process of acetylcholine hydrolysis by AChE. Combined with the current results, we could see that (S)-dioxabenzofos produces a stable hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl group in the Ser-203 residue, which acts as a competitive inhibitor to hinder the binding of acetylcholine to the polar residue, interfering with the normal hydrolysis function of AChE and making the enantiomer present a significant neurotoxic effect than (R)-dioxabenzofos.

Moreover, this study analyzed the interaction energies of important residues at the catalytic anionic site (Table S2), and the results showed that the average interaction energy of Trp-86, Tyr-124, Phe-295, Phe-297, Phe-338, His-447, and Tyr-449 residues in the toxic respose of AChE to (R)-dioxabenzofos was −1.24 kcal mol–1, which was higher than their average interaction energy (−2.02 kcal mol–1) in the neurotoxic reaction of AChE with (S)-dioxabenzofos. This confirms that the overall strength of the conjugated effects in the toxic reaction of (S)-dioxabenzofos with AChE is stronger than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos, which is in accordance with the results of the enantioselective neurotoxic action modes. Undoubtedly, the conclusions of the study on amino acid energy decomposition not only matched the results of the binding free energy but also explained the different significance of specific residues such as Trp-86, Gly-121, Tyr-124, Ser-203, and His-447 adjacent to the active site to the enantioselective neurotoxic response of AChE to chiral dioxabenzofos. As a whole, these microscopic-scale subtle differences will inevitably trigger different bioaffinities (i.e., intracellular AChE inhibitory activity) of AChE in the toxic response to dioxabenzofos enantiomers, resulting in different levels of AChE-mediated enantioselective neurotoxicity of chiral dioxabenzofos to the SH-SY5Y nerve cells.

Conclusions

In summary, this study evaluated the AChE-mediated enantioselective toxic effects of chiral dioxabenzofos on the SH-SY5Y nerve cells from multiple dimensions and elucidated the microscopic mechanism of neurotoxicity at the enantiomeric scale. Cell experiments showed that dioxabenzofos enantiomers inhibited the intracellular AChE activity of SH-SY5Y in a dose-dependent manner, and (S)-dioxabenzofos had a stronger intracellular AChE inhibitory effect than (R)-dioxabenzofos, with IC50 values of 17.2 μM and 5.28 μM, respectively, displaying significant enantioselectivity. Molecular-level investigations interpreted the SH-SY5Y cells-based assay; namely, the enantioselective neurotoxic response of SH-SY5Y cells to chiral dioxabenzofos was mainly due to the difference in bioaffinity between both enantiomers and intracellular AChE. The toxic action modes indicated that the chiral P atom can trigger the differences in the orientation of dioxabenzofos enantiomers, resulting in conjugated effects between (R)-dioxabenzofos and important residues at the catalytic anionic site, while (S)-dioxabenzofos formed stable hydrogen bonds with these residues, which is propitious to increasing the bioaffinity between AChE and (S)-dioxabenzofos.

In the meantime, owing to the intervention of AChE’s intrinsic conformational dynamics and flexibility, the hydrogen bonds and conjugated effects between (S)-dioxabenzofos and AChE presented a strengthening trend, which elevated the conformational stability of AChE and augmented the bioaffinity relative to its antipode. This phenomenon was reflected in the differences in Rg, RMSF, and secondary structure components. Energy decomposition explained that the binding free energy (−23.55 ± 0.17 kcal mol–1) of (S)-dioxabenzofos to AChE was weaker than that of (R)-dioxabenzofos (−15.43 ± 0.12 kcal mol–1), which is consistent with the results of wet experiments; also, the electrostatic contribution (ΔG ele) was the main energy contribution to enantioselectivity. Yet, key residues, e.g., Trp-86, Tyr-124, Ser-203, Tyr-337, and His-447, around the active site have been shown to hold different importance in the enantioselective toxic reaction. It could be seen that the subtle differences in bioaffinity, noncovalent bonds, conformational dynamics and flexibility, energy, and molecular conformation, as well as the high selectivity of certain important residues in enantiomeric neurotoxic response, may describe the more potent intracellular AChE-mediated toxic effect (i.e., neurotoxic risk) of (S)-dioxabenzofos on the SH-SY5Y nerve cells. Obviously, this attempt can provide a useful theoretical framework for assessing the neurotoxicity hazard of environmental exposure to chiral organophosphorus pollutants such as dioxabenzofos to human health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Krishna N. Ganesh of the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research for his kind support during the manuscript processing. We also thank the reviewers of this manuscript for their insightful and valuable suggestions. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 22403094 and 22577066 to W.P.), the Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province (no. tsqn202507079 to W.P.), the project ZR2025QB36 supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (W.P.), the “Qilu Youth Scholar Research Grant” of Shandong University (W.P.), the Young Talent Development Program of the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology (no. M2025YB02 to W.P.), the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (no. 2023-JC-YB-124 to F.D.), the Innovative Research Team for Science and Technology of Shaanxi Province (no. 2022TD-04 to F.D.), the “Chang’an Scholars Construction Project” (no. 201806CT016 to F.D.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 300102291301 to F.D. and no. 300102295734 to Z.-C.He).

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c06614.

Protocols for the determination of tryptophan fluorescence, time-resolved fluorescence decay, molecular dynamics simulations, circular dichroism spectroscopy, and their corresponding data and analyses (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Chen X. J., Nian M., Zhao F., Ma Y., Yao J. Z., Wang S. Y., Chen X., Li D., Fang M. L.. Artificial intelligence for the discovery of safe and effective flame retardants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025;59:7187–7199. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.4c14787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z. T., Zhu Y. N., Che R. J., Chen T., Liang J., Xia M. Z., Wang F. H.. Unraveling the complexity of organophosphorus pesticides: Ecological risks, biochemical pathways and the promise of machine learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2025;974:179206. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönleben A. M., den Ouden F., Yin S. S., Fransen E., Bosschaerts S., Andjelkovic M., Rehman N., van Nuijs A. L. N., Covaci A., Poma G.. Organophosphorus flame retardant, phthalate, and alternative plasticizer contamination in novel plant-based food: A food safety investigation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025;59:9209–9220. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.4c11805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. X., Li S. Y., Ma Y. T., Li C. Q., Lu H., Xiong J. R., He G. Z., Li R. Y., Ren X. M., Huang B., Pan X. J.. Role of organophosphorus pesticides in facilitating plasmid-mediated conjugative transfer: Efficiency and mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025;487:137318. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.137318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takarada W. H., Nazareno M. H., de Freitas R. A., Orth E. S.. Cellulose-derived biocatalysts and neutralizing gels for pesticides: How to eliminate and avoid intoxication? J. Hazard. Mater. 2025;489:137576. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.137576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi Y., Nagasawa S., Iwase H., Ogra Y.. Evaluation of organophosphorus pesticide tyrosine adducts for postmortem change by human serum albumin with liquid chromatography quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Toxicol. Sci. 2024;199:40–48. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfae023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y., Zhou W. S., Zhang W. X., Lu L. Z., Gao Y., Yu Y. Y., Shan C. H., Tong D. F., Zhang X. Y., Shi W., Liu G. X.. Exposure to malathion impairs learning and memory of zebrafish by disrupting cholinergic signal transmission, undermining synaptic plasticity, and aggravating neuronal apoptosis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025;488:137391. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.137391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. A., He Y. R., Allen S. K., McElroy C. A., Callam C. S., Hadad C. M.. Unprecedented alkylation of the catalytic histidine in the aging of cholinesterases after inhibition by organophosphorus pesticides. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2025;38:503–518. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5c00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy S., Webb K., Riordan G., Stephen C.. Extrapyramidal effects in a young child with acute organophosphorus insecticide poisoning. Clin. Toxicol. 2025;63:151–152. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2025.2453057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owobu A. C., Ogbonnaya C. J., Alli J., Ekusunmi A. A.. A case report of severe organophosphate poisoning and aspiration pneumonitis treated with exchange blood transfusion. Oxford Med. Case Rep. 2025;2025:omaf031. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omaf031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. ; Liu, D. H. ; Zhou, Z. Q. . Shou Xing Nong Yao Shou Ce, 1st ed.; Chemical Industry Press Co., Ltd.: Beijing, 2021; pp 14–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tombo G. M. R., Belluš D.. Chirality and crop protection. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1991;30:1193–1215. doi: 10.1002/anie.199111933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilschnack K., Cartmell E., Sundström V. J., Yates K., Petrie B.. Enantiomeric fraction evaluation for assessing septic tanks as a pathway for chiral pharmaceuticals entering rivers. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts. 2025;27:779–793. doi: 10.1039/D4EM00715H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. H., Liu Y., Zhang Y., Huang P., Bartlam M., Wang Y. Y.. Stereoselective behavior of naproxen chiral enantiomers in promoting horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025;489:137692. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.137692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. S., Sun X. F., Lv B., Xu J. Y., Zhang J., Gao Y. Y., Gao B. B., Shi H. Y., Wang M. H.. Stereoselective environmental fate of fosthiazate in soil and water-sediment microcosms. Environ. Res. 2021;194:110696. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L. C., Xu L. Y., Zhang N., Shi Q. Y., Shi T. Z., Ma X., Wu X. W., Li Q. X., Hua R. M.. Enantioselective degradation of the organophosphorus insecticide isocarbophos in Cupriavidus nantongensis X1T: Characteristics, enantioselective regulation, degradation pathways, and toxicity assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;417:126024. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. Z., Sun L., Yang X. F., Peng C. S., Hua R. M., Zhu M. Q.. Enantioselective effects of chiral profenofos on the conformation for human serum albumin. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024;205:106159. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2024.106159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. J., Teng M. M., Chen L.. A review on the enantioselective distribution and toxicity of chiral pesticides in aquatic environment. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2024;46:317. doi: 10.1007/s10653-024-02102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhou R. D., Xie H. Y., Li G., Xu Z. G., Liu M. J., Gao W. T.. Chiral separation and determination of multiple organophosphorus pesticide enantiomers in soil based on cellulose-based chiral column by LC-MS/MS. J. Sep. Sci. 2025;48:e70100. doi: 10.1002/jssc.70100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke P.. The continuing significance of chiral agrochemicals. Pest Manage. Sci. 2025;81:1697–1716. doi: 10.1002/ps.8655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrochemical Division award goes to Eto. Awards. Agrochemical Division award goes to Eto. Chem. Eng. News. 1994;72(10):54–55. doi: 10.1021/cen-v072n010.p054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorke D. E., Oz M.. A review on oxidative stress in organophosphate-induced neurotoxicity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2025;180:106735. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2025.106735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashima A., Eto M.. Synthesis of optically active cyclic phosphorothionates and phosphoramidothionates with insecticidal activity by using a chiral phosphorylating agent. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983;47:2831–2839. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.47.2831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashima A., Ishaaya I., Ueno R., Ichiyama Y., Wu S.-Y., Eto M.. Biological activity of optically active salithion and salioxon. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1989;53:175–178. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1989.10869279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashima A., Ishaaya I., Ueno R., Oyama K., Eto M.. Effect of salithion enantiomers on the trehalase system and on the digestive protease, amylase, and invertase of Tribolium castaneum . Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1989;34:205–210. doi: 10.1016/0048-3575(89)90159-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashima A., Ueno R., Oyama K., Koga H., Eto M.. Effect of salithion enantiomers on larval growth, carbohydrases, acetylcholinesterase, adenylate cyclase activities and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate level of Musca domestica and Tribolium castaneum . Agric. Biol. Chem. 1990;54:1013–1022. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1990.10870084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]