Abstract

One of the most significant advancements in basalt fiber (BF) technology is its application in Basalt fiber reinforced polymers (BFRP). The production of BFRP utilizes basalt rock, a naturally abundant resource, resulting in a composite that generates approximately 74% less carbon emissions compared to traditional steel, aligning with global sustainability goals. This study employs previously published experimental datasets on basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC) to statistically predict compressive strength (CS) and splitting tensile strength (STS) using advanced machine learning. The dataset includes 270 CS and 267 STS samples, split into 70% training and 30% testing, enabling accurate, data-driven predictions without the need for new laboratory experiments. In addition to the parametric analysis of Shapley additive explanation (SHAP), machine learning models were used, namely support vector regression (SVR), random forest regression (RFR), decision tree (DT), bagging regressor (BR), and gradient boosting regression (GBR) with grid search hyper-tuning. Additionally, the model generated SHAP interaction plots to show the impact of each characteristic on an individual prediction. The results found that GBR model performance is the most precise prediction of compressive strength compared to other models, achieving an R2 of 0.99 for training phase and R2 of 0.86 for testing phase. But SVR model outperforms the other four models in STS prediction, with the coefficient of determination (R2) value of 0.99 during the training stage and R2 of 0.97 for the testing stage. The Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) method was used to display the effect of each input parameters on model prediction. The cement and silica fume were found to have the highest positive influence on BFRC compressive and tensile strength. The basalt fiber (BF) diameter as an input parameter was found to have the highest effect on STC. Finally, the concrete designers can now easily and affordably predict CS and STS using a graphical user interface, without conducting expensive computations or experiments.

Keywords: Basalt fiber-reinforced concrete, Compressive strength, Splitting tensile strength, Artificial intelligence, SHAP analysis, GUI-based prediction

Subject terms: Engineering, Materials science, Mathematics and computing

Introduction

Globally, concrete is the most commonly utilized man-made building commodity because of its exceptional qualities, including robustness, adaptability, and ease of manufacture1. Every year, almost USD 4 billion is spent on maintenance and repairs for about one in seven bridges in the US that have significant steel corrosion2. In addition to being quite expensive, these repairs also affect the performance of structures and create an annoyance for the general public because roads and buildings must be closed. The cost of these disturbances may be ten times higher than that of fixing corrosion3. The use of fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) materials as alternatives to traditional steel reinforcing is therefore becoming increasingly popular. Additionally, numerous studies are also being carried out on the structural performance of reinforced concrete elements employing several kinds of FRP, including FRP basalt, glass, carbon, and aramid FRP. Accordingly, Basalt fiber (BF) is an environmentally benign, inorganic substance that is frequently added to concrete to enhance its tensile qualities4. Along with its many other physical and chemical characteristics, BF has exceptional resilience to heat, durability, mechanical stability of monofilament, high intensity, creep cracking force, elastic modulus, and chemical sustainability5.

Basalt fiber (BF) is the critical reinforcing fiber used to create Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP). Basalt Fiber Reinforced Polymer (BFRP) is rapidly gaining recognition as a leading sustainable building material in the construction industry. Its production process, which utilizes basalt rock—a naturally abundant resource—results in a composite that boasts exceptional durability, strength, and corrosion resistance. BFRP’s low carbon footprint, generating approximately 74% less carbon emissions compared to traditional steel, positions it as an eco-friendly alternative that aligns with global sustainability goals. The material’s impressive tensile strength and resistance to environmental factors make it ideal for various applications, including structural reinforcements in bridges, buildings, and other infrastructure projects6–8. Figure 1a,b shows the raw BF and BFRP.

Fig. 1.

Raw Basalt fiber and Basalt fiber reinforced polymer.

Basalt fiber (BF) has a mechanical stability index that is almost 30% higher than that of regular glass fiber, and it has superior corrosion resistance. About 1/16 of carbon fiber is used in the process, and the creep fracture ratio is around 1/4 of aramid fiber9. Among its application areas are the military and national defense industries, building reinforcement, marine engineering, civil engineering facilities, extra-high voltage electricity distribution, rail transit vehicles, lightweight automobiles, fire safety, sustainability, and more. BF is a synthetic silicate fiber that provides technical benefits in the areas of concrete reinforcement, cement reinforcement, and asphalt sealing. It also naturally blends well with silicate materials like cement and concrete10.

In comparison to regular concrete, basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC) demonstrates the following three distinct quality performance characteristics:

BFRC’s frost resistance has been significantly enhanced, and its compressive strength has increased by roughly 2.6%.

Flexural capacity was augmented by 15.3%, while the maximum tensile length in bending underwent a substantial improvement of 19.1%. Furthermore, the splitting tensile strength of BFRC witnessed a 9.8% upsurge, significantly delaying the onset of major fissures and mitigating microcrack propagation induced by concrete contraction.

Steel can be efficiently replaced with BF reinforcing materials, which can also solve technical issues like corrosion and maintenance of metal components and increase the sustainability and reliability of concrete building structures11.

At present, numerous studies have demonstrated that mixing BF reinforcement concrete can enhance its mechanical qualities. Wang et al.12 examined the significance of blended fibers (BF) and polypropylene fibers on HPC’s stress–strain curves, STS capacity, FS, and CS. The findings suggested that mixing fiber would increase the CS satisfactory level of reinforced concrete. Zheng et al.4 Carried out a thorough investigation into how the BF concentration affected the fundamental mechanical characteristics of concrete. This research experiment on performing compression testing and splitting tensile strength. The findings illustrated that BF can increase the CS of concrete by a significant portion. By altering the BF concentration, Gao et al.13 were able to demonstrate the splitting tensile behavior, axial compression, and cubic compression of BFRC specimens. It can be confirmed that involving BF in concrete will increase its compressive strength in proportion, as both the simulated results and the test data indicate a similar pattern, and this correlation suggests the reliability of the enhancement on BFRC.

In current decades, a range of ML algorithms has been utilizing to estimate the mechanical characteristics of concrete, offering a way to develop more accurate and general predictive model14. Table 1 displayed a summary of different ML models’ predictions by different studies of BFRC. Mahjoubi et al.15 utilized semi-supervised learning, augmented data to train and compare models developed by four machine learning algorithms. The experimental results found that artificial intelligence can help achieve a UHPC ratio with the lowest cost and carbon footprint. Severcan et.al16 verified that the GEP model effectively captures the STS of concrete. In comparison to alternative methods, research investigation showed that GEP performed better at predicting the STS. A study by Kang et al.17 assessed and compared different traditional learning approaches to forecast the flexural capacity of concrete reinforced with steel fibers. This investigation demonstrated that the evaluation of the CS was typically superior to the flexural-strength prediction. M5P model, Gaussian process, random tree (RT), and random forest (RF) methods were used by Gupta et al.18 to identify the ideal portion of concrete mixtures, several applied models were assessed. Thus, compared to other models, Gaussian process regression with an RBF kernel was found to generate superior results. Utilizing the Random Forest learning models with four different input variables and CS as the outcomes, Hong Li et al. evaluated the findings by utilizing the Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithms and the Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) models. The investigation discovered that Random Forest (R2 = 0.96) performed effectively than both the SVM model (R2 = 0.93) and BPNN (R2 = 0.94) in estimating the CS of BFRC. Parhi et al.19 study showed that incorporating PET fibers significantly enhances the fracture toughness and ductility of concrete, with fiber aspect ratio, volume fraction, length, and W/B ratio being the most critical factors. Optimization via RSM identified ideal parameter values, highlighting PFRC as a sustainable, high-performance alternative to conventional concrete.

Table 1.

Mechanical Strength properties prediction in the previous article.

| Year | Algorithms used | Best performing model | Predicted output(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | BPNN, SVR, GPR, KELM and Hybrid KELM-GA | Hybrid KELM-GA | Compressive Strength | 20 |

| 2022 | LR, SVR, PR | PR | Compressive, Tensile, and Flexural Strengths | 21 |

| 2023 | XGBoost, GB, RF, SVR and GA | GA | Dynamic Mechanical Strength | 5 |

| 2023 | RF, and RT | RF | Split Tensile Strength | 26 |

| 2023 | SVR, KNN, RF, ETR, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost | CatBoost, and RF | Compressive, Tensile, and Flexural Strengths | 28 |

| 2023 | SVM, ADB, DT, and GB | GB | Flexural Capacity | 29 |

| 2023 | XGBoost, RF, GBDT, AdaBoost, and SVR | GA-XGBoost | Compressive Strength | 4 |

| 2024 | AdaBoost, Random Forest. LightGBM, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, and KNN | XGBoost | Flexural, Compressive, and Splitting Tensile Strengths | 39 |

| 2025 | Theoretical and FE models | Theoretical and FE models | Flexural Capacity | 40 |

| 2025 | ELM | ELM | Compressive Strength | 41 |

Along with Li et al.20 predicted the CS of BFRC using five algorithms: Support Vector Regression (SVR), BPNN, KELM, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), and Kernel Extreme Learning Machine-Genetic Algorithm (KELM-GA). According to their investigation, the hybrid KELM-GA algorithms demonstrated excellent performance than the other models. Zheng et al.15 estimated the BFRC Dynamic Increase Factor (DIF) by combining Random Forest with a stacking ensemble algorithm, Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, and SVR models. The research investigation found that the proposed algorithms performed considerably outperformed those that were optimized using GA. Subsequently, Hasanzadeh et al.16 predicted the mechanical characteristics of high-performing concrete reinforced mixing basalt fibers using machine learning algorithms. They developed three machine-learning algorithms: Linear Regression (LR), SVR, and Polynomial Regression (PR), and estimated the CS, STS, and FS22,23. According to the results, the proposed PR models considerably outperformed other standalone machine learning methods tested on independent experimental data using feature selection approaches24,25. To precisely estimate the unconfined CS of marine clay and also use wastage tile blends, Li et al.17 applied four hybrid approaches that use random forests, regulating gradient boosting, the support vector regression with Aquila-optimizer algorithm, and an adaptive neuro-fuzzy learning technique. According to their findings, with the Aquila-optimizer algorithm, the extreme gradient boosting model operated with exceptional accuracy, along with adjusting the scatter index and best level of generalization. Although several studies have concentrated on the bond between concrete proportion and CS, which are very common, there aren’t many studies on BFRC compressive strength prediction utilizing machine learning algorithms that combine basalt characteristic parameters and concrete proportion18.

A study by Almohammed et al.19 used the Random Tree (RT) and random forest (RF) to determine the most effective model for estimating the splitting tensile capacity of reinforced concrete using Basalt Fiber (BF). The experimental research found that three accuracy matrices (RMSE = 0.1430, 0.2406, MAE = 0.0886, 0.1842, and CC = 0.9889, 0.9579) showed superior results in their newly developed machine-learning algorithm; random forest outperformed in the training and testing data phase. Specifically, Random Forest and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) were integrated with the Krill Herd (KH) and Leopard Seal Algorithm (LSA), revealing that the XGB-LSA combination achieved the highest accuracy, with R2 values of 0.97 and 0.95 for the training and testing datasets, respectively27 Cakiroglu et al.20 work assembled a thorough experimental database with 16 different input datasets to predict flexural strength, compressive, and tensile strengths. According to their experimental studies, utilizing seven different data-driven ML algorithms and the CatBoost model performed better in estimating compressive and tensile strength. Abushanab et al.5 used the four ML techniques with an ensemble model to predict the FS of RC beams. In contrast, the suggested machine learning combined gradient-boosting algorithm performed most effectively and had the best capacity for generalization, as demonstrated by a maximum coefficient of determination of 97.30% in the testing stage with the minimum MAE values of 2.78 kN m., MAPR values of 13.40%, and RMSE results of 3.56 kN m.

Rahman et al.21 employed eleven data-driven ML approaches with the most comprehensive dataset collection of 507 experimental findings to forecast the shear strength of SFRC beams. Based on their investigation results, the XGBoost was an extremely reliable algorithm (85%), with two parameter matrices the minimum MAE values, and RMSE. Subsequently, Yang et al.22 assessed the potential Acoustic emission (AE) methods that adding the recommended quantity of basalt fiber (6 kg/m) to reinforced concrete can increase its CS while lowering the volume and intensity of AE-specific factors. For deep beams and reinforcement structures, four significant ensemble approaches are used to estimate the shear strength of reinforced concrete utilizing composite basalt fiber. The investigation results showed that using BFRC to reinforce the joints greatly enhanced their seismic performance and increased the bearing capacity and stability of concrete structures30,31.

There are some studies that investigate the superior predictive capability of ensemble learning models when coupled with advanced metaheuristic optimization techniques32. Sapkota et al.33 integrated explainable ML with nature-inspired optimization approaches to optimize high-strength concrete mix design, highlighting cement and superplasticizer as the most influential factors. They demonstrated the effectiveness of machine learning and hybrid metaheuristic algorithms in predicting the compressive strength of various concretes, with models such as XGBoost, Random Forest, and CatBoost consistently achieving high accuracy (R2 > 0.95) across diverse datasets. For a variety of datasets, the hybrid approach performs better than logical selection34. While the model is progressing and the excessive parameters are raised, it consumes quite a little amount of time and system resources35. Implementation is a challenge with the shear strength of RAC. Another literature ensemble that hybrid ML techniques, particularly those integrating metaheuristic optimization with ensemble learners, have achieved superior accuracy in predicting the structural behavior of UHPC elements, while also identifying the dominant mix and design parameters influencing shear performance36. Similarly, Sapkota et al.37 The work investigates the use of a hybridized machine learning method for a more accurate assessment of STS. They found that swarm intelligence–based optimization (PSO) of ensemble models like XGBoost yields superior performance with R2 of 0.9988 and 0.9602 in the training and testing phases in predicting concrete strength parameters. High-accuracy computations and optimum design might be the solution. Additionally, Yu et al.26 distinguished the experimental shear strength of the beam from the obtainable design equations. Parhi et al.38 employed decision tree-based models (DT, RF, and GBM) optimized with Dolphin Echolocation Optimization (DEO) to predict the compressive strength of PET-fiber-reinforced concrete. According to the findings, the DEO-tuned Random Forest showed superior performance, while SHAP and Sobol analyses identified binder content, fiber volume fraction, and W/B ratio as the most critical factors influencing strength prediction.

Unlike prior studies, which mainly emphasized prediction accuracy for conventional concrete or used hybrid/metaheuristic models without addressing interpretability, the present study is novel in three ways. First, it specifically focuses on basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC), a relatively underexplored material. Second, it integrates SHAP analysis to explain variable contributions, bridging the gap between accuracy and transparency. Finally, it develops a GUI tool, translating predictive models into a practical application for engineering design.

Significance of this research

In the current study, very few studies have focused on modelling and predicting the CS and TS of Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (BFRC) employing advanced machine learning (ML) methods. This study bridges this gap by employing seven state-of-the-art ML models: Decision Tree (DT), Bagging Regressor (BR), Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Random Forest Regression (RFR) optimized using grid search hyperparameter tuning for enhanced predictive accuracy. The thorough analysis carried out employing 10 significant input parameters that were found in the literature to be crucial elements influencing CS and STS is a significant innovation of this study. Furthermore, this study introduces a novel approach by integrating SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) analysis to interpret the impact of input features on CS and STS predictions. This study also develops a user-friendly GUI tool for estimating the splitting tensile strength (STS), and compressive strength (CS), enhancing the level of practical applicability of the proposed models. Furthermore, the proposed approach enables significant time savings, labor efficiency, cost reductions, and material waste minimization while achieving target CS and TS with precision. This research contributes to the advancement of sustainable and efficient concrete mix design methodologies, offering valuable guidance for both academic and industrial applications in civil engineering.

Methodology

Support vector regression (SVR)

The SVR machine learning model can perform non-Linear Regression and, by altering the kernel function, may be able to be tailored to datasets with different properties42. This approach also has the benefit of applying the optimal kernel function to improve the accuracy of the forecasted results4. Additionally, some research that used SVR for concrete strength prediction before this one showed that it could be used on tiny and mid-sized complicated datasets.

Considering a data set for training D=

here

here  is represent the input parameter and

is represent the input parameter and  is indicate the output parameter, where Eq. 1 shows that the conventional form of SVR is a linear function f(x).

is indicate the output parameter, where Eq. 1 shows that the conventional form of SVR is a linear function f(x).

| 1 |

In this scenario, b represents the bias value, and w is the function of the weight vector. Along with the SVR enhancement, it aims to reduce the divergence among the true value y and the predicted value (x). This can be done by measuring the function of loss, which is shown in Eq. 2.

| 2 |

where, penalty parameter is denoted by C.  and

and  are loose parameters. In order to effectively deal with the non-linear challenges and the kernel-based features equation K (

are loose parameters. In order to effectively deal with the non-linear challenges and the kernel-based features equation K ( ,

,  ) = ϕ(

) = ϕ( ) ⋅ ϕ(

) ⋅ ϕ( ) is presented in order to change the sample’s low-dimensional data into a high-dimensional space, and generate the appearance of higher-order characteristics without really including additional characteristics.

) is presented in order to change the sample’s low-dimensional data into a high-dimensional space, and generate the appearance of higher-order characteristics without really including additional characteristics.

Gradient boosting regressor

The GBR model works process similarly to the random forest model. Still, the GBR model uses a collection of base learners that can generate superior predictions for multiple types of classification or regression tree issues43. Originally developed primarily for classification problems, the GBM model was later extended to useful regression tree applications. To construct a model that is additive while minimizing the loss function at each stage, it can be viewed as a numerical method of optimization.44. Additionally, in the training phase, several decision tree is consistently constructed for the GBM model in order to connect the existing ensemble and minimize the mean squared error loss45. Along with this, the GBR is specifically one of the most popular algorithms used to estimate high-performance concrete’s compressive strength as well as other very accurate outcome predictions for any type of data handling-related work, particularly in the civil engineering sector. The following mathematical formulas explain how a gradient boosting regressor functions:

| 3 |

where X is the input vector, η is the rate function of learning gap or shrinkage, f is the base learner, and F is the ensemble model.

Random forest regression

RF is an integrated learning method that develops an ensemble of decision trees to minimize the potential for error in a single decision tree46. Additionally, the random forest regression is widely recognized for its adaptability and efficiency in forecasting the compressive strength of building materials. The following method makes use of bagging, which is defined as the process that generates a forest by combining randomly chosen, related datasets from the training set47. RF has been determined in the following way: from the initial training set N, k bootstrap sample sets are subsequently selected at random employing the bootstrap method, and k regression trees are then constructed from them42. And K out-of-bag data is always composed of all undrawn samples. The second step is to choose a variable with the highest classification ability in  by randomly selecting

by randomly selecting  variables from

variables from  variables at each tree node. By examining every classification point, the variable classification threshold is established. Ultimately, a random forest approach is constructed by joining several decision trees into an ensemble that is capable of accurately predicting current data. To solve this regression problem, the decision tree’s effectiveness can be evaluated employing the out-of-bag (OOB) input datapoints. This assessment score is known as the out-of-bag error. The random forest regression model’s overall performance can be reflected in each of the OOB sections and series of decision trees. In regression situations, the MSE reduction is frequently utilized as the OOB evaluation index, and where the specific evaluation process is followed,

variables at each tree node. By examining every classification point, the variable classification threshold is established. Ultimately, a random forest approach is constructed by joining several decision trees into an ensemble that is capable of accurately predicting current data. To solve this regression problem, the decision tree’s effectiveness can be evaluated employing the out-of-bag (OOB) input datapoints. This assessment score is known as the out-of-bag error. The random forest regression model’s overall performance can be reflected in each of the OOB sections and series of decision trees. In regression situations, the MSE reduction is frequently utilized as the OOB evaluation index, and where the specific evaluation process is followed,

| 4 |

Here, represents the (OOB) score function of the i-th level of the decision tree,

represents the (OOB) score function of the i-th level of the decision tree,  demonstrates the i-th dataset in the input parameter

demonstrates the i-th dataset in the input parameter  , and the desired values provided by the i-th decision tree, depending on the inputs

, and the desired values provided by the i-th decision tree, depending on the inputs  is indicated by

is indicated by  . Similarly, other out-of-bag datapoints for the

. Similarly, other out-of-bag datapoints for the  variable after resampling is represented by

variable after resampling is represented by  .

.

Decision tree algorithm

Decision tree (DT) is the most widely known individual learning algorithm, which is used to identify and classify regression issues, as well as other kinds of challenges48. In the tree structure, there are classes. In the event of the absence of a class, however, the regression method will depend on the independent variables to predict the results49. In addition to forecasting the objective parameters established on the partitions between the input variables, the regression tree aims to construct predictive partitions. The two nodes that jointly constitute DT models are the leaf node and the decision node. Notably, leaf nodes are thought of be the results of the decision and lack branches. Decision nodes, on the other hand, can make any decision because they have multiple decision branches. Finally, the DT algorithm starts at the base and involves many branches, replicating the structure of a real tree50. Furthermore, due primarily to the regression tree’s implicit variable selection, the training regression tree highlights elements from the previous node in the tree that are more important for forecasting target parameters17. The regression tree’s ability to handle both categorical and numerical information is its primary benefit.

Bagging regressor

Bagging Regressor (BR) is an ensemble learning method that enhances the performance and stability of regression models by combining the predictions of multiple base regressors. BR method uses the bagging (bootstrap aggregating) technique. BR is applied by incorporating more data into the forecasting algorithm during the training stage51. Sampling with replacement allows certain observations to be repeated within each newly generated training dataset. In the bagging regression process, each data point has an equal probability of being selected in the newly generated training subsets52. Increasing the maximum size of the function in the training set has minimal impact on the model’s predictive performance, as the primary improvement comes from aggregating diverse models trained on varied subsets. Additionally, variance can be significantly reduced by aligning the predictions with the target outcome. The bootstrap samples are commonly used to train multiple models, each learning different aspects of the data. The predictions from these models are then averaged, and in regression tasks, the final forecast is typically obtained by taking the arithmetic mean of all individual model predictions51,53.

Hyperparameter tuning

Grid Search method is used to determine which hyperparameter combination is optimal for a particular machine learning model. In this current study, the grid search function is employed to optimize the hyperparameter settings, systematically testing many combinations of feature hyperparameters to classify the best-performing configuration for each model. Furthermore, a fivefold cross-validation strategy was applied during the training process to ensure robust performance assessment and minimize overfitting. Hyperparameter tuning using grid search was performed within the cross-validation framework to prevent data leakage. We used Python Version 3.10.8 in all of the model analyses. Table 2 provides the grid search-based hyperparameter tuning results for the developed machine learning models. Table 2 demonstrated that for each model, different hyperparameter values provided the best performance for CS and STS, demonstrating the importance of fine-tuning to improve model accuracy.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter Tuning Using Grid Search Method for the Optimized ML Models.

| Model | Hyperparameter | Range | Optimal value of CS | Optimal value of STS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFR | learning_rate | 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| max_depth | 3,5,9,11, 16, 20 | 16 | 5 | |

| n_estimators | 50,80,100,200,300 | 80 | 80 | |

| max_feature | 2,4,8,12 | 4 | 12 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 1, 2, 4 | 1 | 2 | |

| min_samples_split | 2,5,10 | 2 | 2 | |

| GBR | n_estimators | 50,70,100,200,500 | 70 | 100 |

| learning_rate | 0.01,0.05 0.1, 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.05 | |

| max_depth | 3,5,7,9,11 | 3 | 5 | |

| subsample | 0.1, 0.5,0.8,1,2 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| DTR | min_samples_split | 2,5,11 | 2 | 2 |

| max_depth | 3,7,11,14 | 11 | 11 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 1,2,5,7 | 2 | 5 | |

| max_leaf_nodes | 10,50,100 | 100 | 50 | |

| SVR | degree | 2,3,4,5 | 2 | 2 |

| gamma | scale, auto | scale | scale | |

| C | 100,200,300,500 | 100 | 100 | |

| kernel | rbf, poly, sigmoid | rbf | rbf | |

| BR | n_estimators | 50,100,200,300,500 | 50 | 100 |

| max_samples | 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 0.7,1 | 1 | 1 | |

| max_features | 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8,1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | |

| bootstrap | True, False | True | True | |

| bootstrap_features | True, False | True | True |

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)

SHAP is a technique that explains the output of an ML model by evaluating the contribution of every input characteristic to the model’s predictions. It offers an in-depth description of how specific features affect the model’s results. SHAP is a technique for analyzing ML model output20. Lundberg and Lee were the pioneers in suggesting SHAP, which is based on principles from Shapley game theory. SHAP analysis aims to handle the “black box” problem of ML models by making their internal decision processes more understandable and interpretable. This analysis enhances the interpretability and transparency of ML models, fostering their confident application in real-world scenarios5,21. Subsequently, SHAP is used to calculate their individual contributions. Attributes with greater SHAP values suggest a more significant influence on the result. SHAP is a powerful tool for model interpretability, broadly accepted in various fields to develop the transparency and accountability of ML models20.

|

5 |

In this linear arrangement, the coefficients are represented by the Shapley values ϕi. A extended representation of the real input x is represented by the vector x’, and a description model is represented by g.

| 6 |

where S specifies a function subset and F is the features taking to initial index i into consideration are suspended, and F represents the set of all input variables.

Uncertainty analysis

Using uncertainty analysis is the most effective approach to assess and measure the uncertainty surrounding the reliability of forecasts by models. To calculate output uncertainties, input uncertainty and its propagation across the model must be taken into account. This current research applied the uncertainty range to measure the future variation associated with model prediction outcomes and to evaluate prospective model variations with confidence levels of 95%. This approach provides a precise analysis of the real data and facilitates decision-making based on the level of uncertainty in the ML model.

Here, U95 exhibits the ML approach uncertainty, and RMSE stands for root mean square error, and SD represents the accuracy of the error standard deviation. The critical value for a standard average distribution’s 95% confidence interval is U95; a lower value indicates a better model54.

Model performance indicators

Model assessment indicators are used to assess the dependability of these models, which are becoming increasingly popular and effective at forecasting the mechanical characteristics of basalt fibers. This study compares the empirical findings of the five models using four performance metrics—R2, MAE, RMSE, and MAPE—to assess the models’ quality.

|

7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

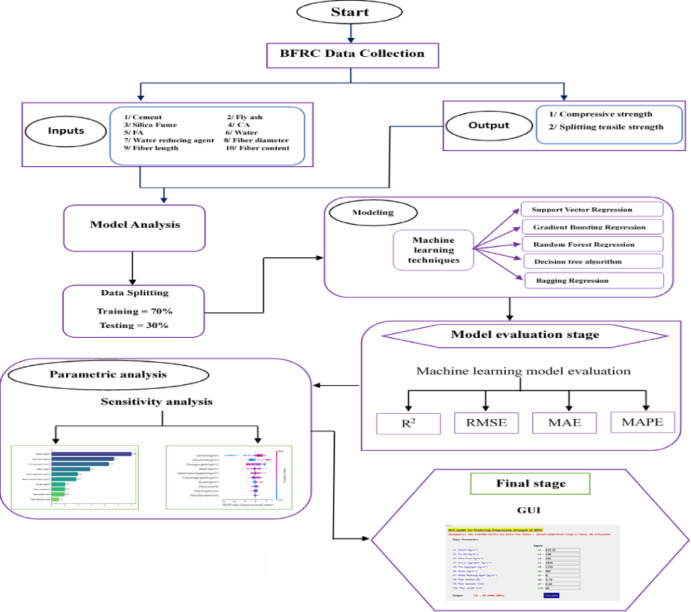

where  and

and  stand for the observed and projected values, and N is the overall amount of test dataset records. Furthermore, the significant relationship between actual and predicted values is demonstrated by the R2 value near (− 1, 1), suggesting that the model better captures the variance of the data55. It should be mentioned that while R2 is a key indicator of model fit, it doesn’t reveal the magnitude of mistakes. To address this issue, the parameter matric RMSE is utilized. Interestingly, the RMSE calculates the average size of errors by taking the square root of the squared variation between expected and observed values. Subsequently, higher measurement precision is achieved as the RMSE approaches 020. Similarly, MAE and MAPE values are regarded as alternative evaluation matrices; the smaller the value (0), the less inaccuracy there is between better measurement and prediction values. Python can be used to build predictive indicators without the need for additional toolboxes or compilers, making model comparisons comparatively simple (Fig. 4). The four initial stages covered in this research are BFRC data collecting, analyzing all ML approaches, calculating model performance, and lastly utilizing parametric analysis.

stand for the observed and projected values, and N is the overall amount of test dataset records. Furthermore, the significant relationship between actual and predicted values is demonstrated by the R2 value near (− 1, 1), suggesting that the model better captures the variance of the data55. It should be mentioned that while R2 is a key indicator of model fit, it doesn’t reveal the magnitude of mistakes. To address this issue, the parameter matric RMSE is utilized. Interestingly, the RMSE calculates the average size of errors by taking the square root of the squared variation between expected and observed values. Subsequently, higher measurement precision is achieved as the RMSE approaches 020. Similarly, MAE and MAPE values are regarded as alternative evaluation matrices; the smaller the value (0), the less inaccuracy there is between better measurement and prediction values. Python can be used to build predictive indicators without the need for additional toolboxes or compilers, making model comparisons comparatively simple (Fig. 4). The four initial stages covered in this research are BFRC data collecting, analyzing all ML approaches, calculating model performance, and lastly utilizing parametric analysis.

Dataset

This study predicted popular ML algorithms using data collected from the literature. The strength values of the mixtures utilized in the BFRC specimens were obtained from the published articles. BFRC concrete data collected for predicting mechanical strength, such as CS and STS. For the prediction of the mechanical strength, in total of 270 data samples were used for compressive strength, and 267 data samples were used for STS collected from a previous study that provided the reference (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/b5s8ywwgwr/1). The data points are divided into two phases: the testing and training phases. 70% of the data points were used at the training stage, and 30% of the data points were used at the testing stage. In the beginning, AI models are usually trained to forecast results with a specific degree of output data accuracy. The purpose of the testing step is to verify that algorithms can project forecast outcomes utilizing a range of data sources21,56–58.

All dataset entries were screened for missing values, duplicates, and inconsistencies. Material quantities were standardized to kg/m3, fiber dimensions to millimeters, and strength values to MPa to ensure consistency across studies. Since the dataset was compiled from diverse experimental conditions, including different curing ages and testing methods, normalization techniques and tenfold cross-validation were applied to mitigate potential biases and enhance the generalization capability of the models.

Table 3 represents the compressive strength of the collected input and output data points. The splitting tensile strength input and output data description is shown in Table 4. However, in Tables 3 and 4, both display 10 input parameters: Silica Fume, Coarse Aggregate, Cement, Fly ash, Fine Aggregate, Water, Water reducing agent, Fiber diameter (mm), Fiber length (mm), and Fiber content (%) for CS and STS of BFRC concrete. On the other hand, the output parameter value is calculated as CS and STS.

Table 3.

Statistical description of the Compressive strength dataset’s input and output variables.

| Cement (Kg/m3) | Fly ash (Kg/m3) | Silica Fune (Kg/m3) | Coarse Aggregate (Kg/m3) | Fine Aggregate (Kg/m3) | Water Kg/m3) | Water reducing agent (Kg/m3) | Fiber diameter (mm) | Fiber length (mm) | Fiber content (%) | CS (Mpa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 |

| mean | 400.67 | 54.83 | 13.61 | 1077.099 | 704.099 | 175.67 | 2.943 | 0.0157 | 16.59 | 0.125 | 49.26 |

| std | 79.128 | 56.69 | 29.522 | 186.43 | 118.03 | 32.87 | 1.92 | 0.009 | 5.99 | 0.122 | 12.05 |

| min | 75.78 | 0 | 0 | 176.57 | 108.67 | 30.84 | 0 | 0.0018 | 5.92 | 0 | 0 |

| 25% | 350 | 0 | 0 | 989.75 | 613 | 160 | 1.08 | 0.015 | 12 | 0.05 | 41.62 |

| 50% | 402 | 0 | 0 | 1125 | 689.6 | 175 | 3.36 | 0.015 | 18 | 0.1 | 48.45 |

| 75% | 450 | 87 | 0 | 1181.3 | 789.25 | 185 | 4.2 | 0.0172 | 20 | 0.16 | 59.2 |

| max | 613.33 | 168 | 126 | 1540 | 1193.66 | 301 | 8 | 0.021 | 30 | 0.73 | 69.9 |

Table 4.

Statistical description of the splitting tensile strength dataset’s input and output variables.

| Cement (Kg/m3) | Fly ash (Kg/m3) | Silica Fume (Kg/m3) | Coarse Aggregate (Kg/m3) | Fine Aggregate (Kg/m3) | Water Kg/m3) | Water reducing agent (Kg/m3) | Fiber diameter (mm) | Fiber length (mm) | Fiber content (%) | STS (Mpa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 267 | 267 | 267 | 267 | 267 | 267 | 267 | 267 | 267 | 267 | 267 |

| mean | 402.54 | 45.71 | 16.42 | 1079.5 | 697.82 | 177.606 | 3.337 | 0.015 | 16.74 | 0.1265 | 4.34 |

| std | 73.92 | 56.69 | 31.28 | 161.98 | 88.452 | 29.87 | 2.242 | 0.0026 | 6.376 | 0.106 | 1.739 |

| min | 217 | 0 | 0 | 512 | 507 | 125 | 0 | 0.013 | 6 | 0 | 2.2 |

| 25% | 353.5 | 0 | 0 | 998 | 633 | 160 | 2.4 | 0.015 | 12 | 0.05 | 3.18 |

| 50% | 402 | 0 | 0 | 1125 | 688 | 179 | 4 | 0.015 | 18 | 0.1 | 3.72 |

| 75% | 450 | 86 | 20 | 1180 | 781 | 188 | 4.81 | 0.015 | 20 | 0.2 | 4.88 |

| max | 613.33 | 168 | 126 | 1540 | 875 | 301 | 8.36 | 0.03 | 30 | 0.5 | 9.8 |

The dataset demonstrates substantial diversity across input parameters. For instance, cement content ranges from 75.78 to 613.33 kg/m3, fiber length from 5.92 to 30 mm, and water content from 30.84 to 301 kg/m3. This wide variation reflects the incorporation of different BFRC mix designs collected from multiple published studies, ensuring that the trained models are generalizable across a broad spectrum of compositions.

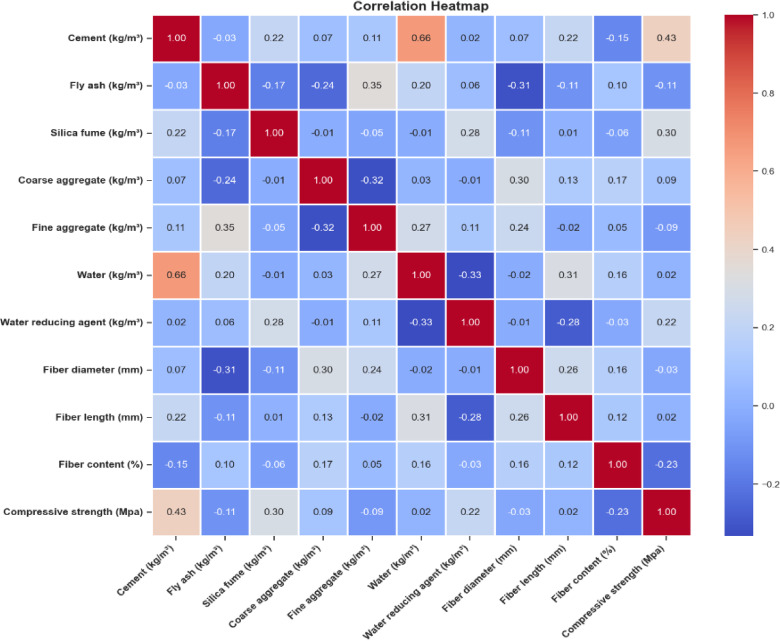

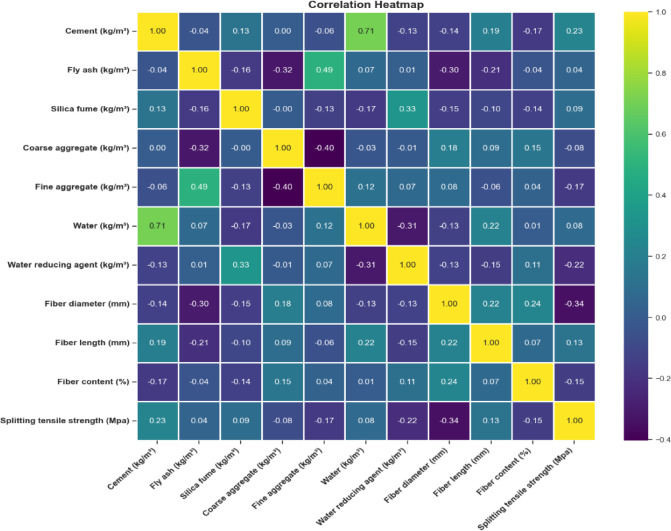

Figure 2 and 3 show how the correlation coefficient value relates to the output and input variables. The effect relationships between inputs and output variables were established by the Seaborn Heatmap technique, which was used to illustrate the correlation coefficient value. The different colours show the relationship coefficient’s negative and positive effects on input and output attributes.

Fig. 2.

Heat map of the CS’s input and output variables.

Fig. 3.

Heat map of the STS input and output variables.

Figure 2 illustrates that cement significantly improves the properties of CS, with a value of approximately 0.43. In addition, the Silica fume and water-reducing agent have a good impact on strength properties. However, compressive strength is negatively impacted by some input parameters, such as Fiber content, Fly ash, and Fine Aggregate. In Fig. 3, the input parameter of cement strongly positively influences STS, which is a value of 0.23. Furthermore, the Fiber length, Water, and Silica Fume input parameters moderately influenced the STS of the BFRC concrete. On the other hand, the Water reducing agent, Fiber diameter, Fiber content, and Fine Aggregate input parameters negatively affect the STS properties (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Diagram of the working process of this research.

Results and discussion

ML models’ prediction performance

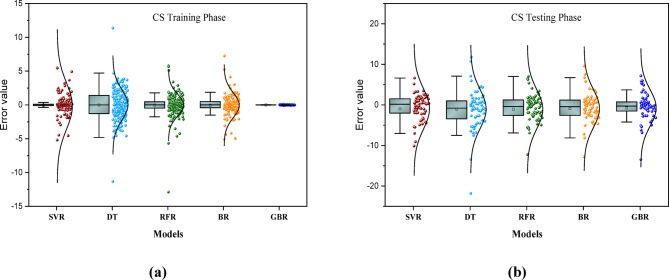

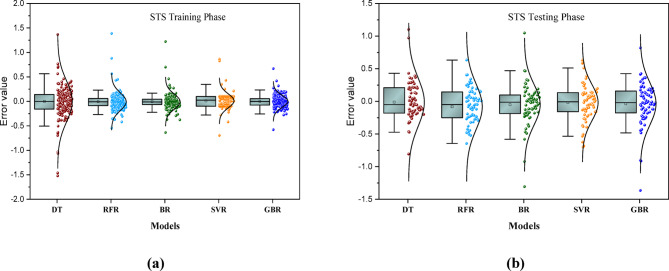

Figure 5 displays the bar normal distribution of errors produced by five machine learning models (SVR, BR, RFR, DT, and GBR) during the test and train phases of predicting the CS value of BFRC. It shows that most of the error ranges from + 5 to − 5 at the training stage and from around + 13 to − 13 at the testing phase. The GBR model demonstrates the lowest error value from around + 0.5 to − 0.5, which indicates good performance. In addition, the SVR, DT, RFR, and BR models displayed in Fig. 5a show the error value from + 5 to − 5 for CS prediction. However, at the testing stage, the machine learning models show error range values almost similar, and the maximum error range for ML models is between + 7 and − 7 for CS prediction. So, it is noticeable that ML models have good performance. Figure 6 demonstrates the bar normal distribution of error ranges during the training and testing phases for predicting the splitting tensile strength (STS) of BFRC. Figure 6a indicates that the majority of errors in predicting STS fall within the range of − 0.5 to + 0.5. At the training stage, the RFR, BR, SVR, and GBR models show the most of number of errors fall between + 0.25 and − 0.25, while the DT model displayed the largest number of errors from + 0.5 to − 0.5. However, at the testing phase, the maximum number of errors was adjusted from + 0.5 to − 0.5 for ML models of predicting STS of BFRC, which exhibited excellent performance.

Fig. 5.

The error value of ML modes for CS prediction.

Fig. 6.

The error value of ML models for STS prediction.

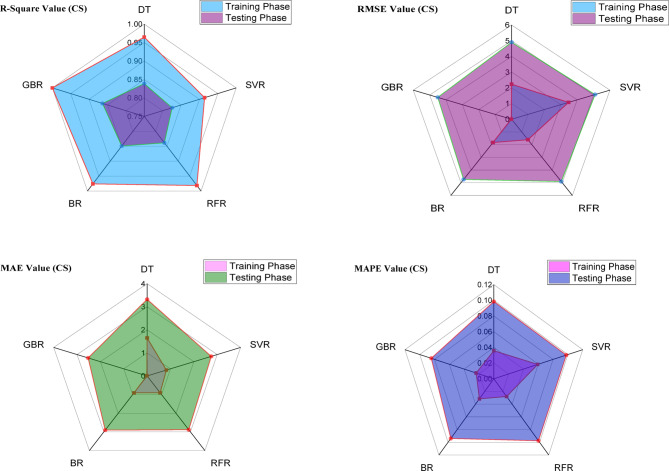

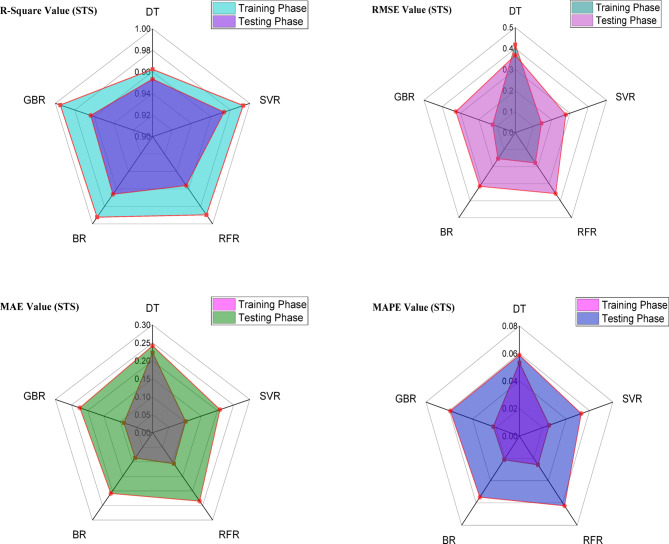

Figure 7 presents the statistical results for compressive strength (CS) based on the model’s performance metrics, including R2, RMSE, MAPE, and MAE. The evaluation of the aforementioned measurement features can effectively determine the performance of ML models tailored for dataset applications. These criteria demonstrate how effectively models are adapted and how accurately they measure performance. In Fig. 7, the R-Square value of the machine learning models is above 0.910 at the train phase and 0.830 at the test phase, indicating good performance. Based on the analysis, the GBR model showed an R-Square value of approximately 0.990 during the training phase and 0.863 during the testing phase. At the training stage, the DT, SVR, RFR, and BR models achieved R-squared values of approximately 0.964, 0.914, 0.981, and 0.976, respectively, for predicting the compressive strength (CS) of the BFRC datasets. In addition, the GBR model showed the lowest RMSE value, about 0.0219 at the train stage and 4.508 at the test stage. The DT, SVR, RFR, and BR models represented RMSE values of 2.230, 3.474, 1.612, and 1.834 at the training stage, respectively. Furthermore, the MAE value of the GBR model was approximately 0.0148 during the training stage and 2.526 during the testing stage for the predicted CS of BFRC. Finally, the variable MAPE value of the GBR model was less than other models. Overall, the results indicate that while the GBR model demonstrates slightly superior performance compared to the other models, all the machine learning models exhibit strong performance based on the evaluation metric values. However, the findings of the model performance evaluation for analytical STS are shown in Fig. 8. Notably, the parameter R-Square value found for all models is above 0.960 at the train stage and 0.950 at the test stage. According to the R-Square value found, all machine learning models perform well in predicting STS of BFRC datasets. At the testing stage, the RMSE value showed 0.124 for the GBR model at the training stage, indicating better performance. The DT, SVR, RFR, and BR models represented RMSE values of 0.418, 0.143, 0.177, and 0.152 at the training phase, respectively. Based on the analysis, the MAE value shows for all models is less than around 0.1064 at the training stage and almost 0.240 at the testing phase. Further, the evaluation parameter MAPE value is less than 0.06 at the testing stage and 0.220 at the test stage for all models. Overall, all ML models have good performance for predicting STS of BFRC datasets.

Fig. 7.

Radar plots of CS prediction performance ML models.

Fig. 8.

Radar plots of STS prediction performance ML models.

Figures 9 and 10 depict the comparison between real and forecast data points for CS and STS during both the test and train stages. They also highlight the linear fit’s error margins, which fall within a range of + 10% to − 10%. In Fig. 9, it shows that more than 95% of the predicted CS data points adjusted for all models within the error range from + 10% to − 10%, and very close to resembling the 1:1 linear fit line. Most importantly, the GBR model performs slightly better than the other models, as fewer data points fall outside the error range. The GBR model almost 98% of data points within the error range and is very close to 1:1 linear fit line. However, Fig. 10 displayed that the STS predicted datasets were around 96% at both phases within the error range between + 10% and − 10%, and very close to 1:1 linear fit line of machine learning models. The DT, BR, and GBR models show slightly better performance compared to other models. All things considered, it can be said that all of the models are appropriate and applicable for use in BFRC mixture-related construction fields.

Fig. 9.

Scatter plots of observed and CS predicted values for ML models.

Fig. 10.

Scatter plots of observed and STS predicted values for ML models.

As mentioned, Fig. 11a–d exhibited how the Taylor diagram was assessed by assembling the values of predicted algorithms in both the training and testing stages. In addition, it represents an accurate measurement of ML algorithms considered in current research and evaluates the performance metrics, including the correlation coefficient and the standard deviation. The initial concepts of this diagram are to show which prediction algorithms have a stronger correlation with the matching actual values on the two-dimensional scale. The evaluation parameter R value close to (0, 1) shows a substantial correlation between observed and predicted values. Based on this criterion, the GBR models outperformed others in predicting CS during both the train and test stages. Similarly, retaining all of the machine learning algorithms, SVR, RFR, DTR, and BR, demonstrated R values around 0.90 to 0.95 during testing stages, which indicated strong performance with a very high accuracy. Conversely, Fig. 11c,d illustrates the best performance to predict the STS. An investigation finding is that apart from the machine learning DTR and GBR model, all of the algorithms exhibit best accuracy in the training stage, around 0.99, compared with the testing phase. According to the testing values, SVR, RFR, and BR models represented the lower RMSE and optimum standard deviations, which indicated excellent performance of this model and addressed overfitting issues.

Fig. 11.

Taylor diagram for prediction performance of ML models.

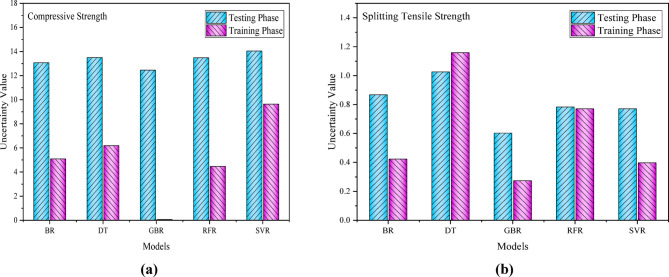

Uncertainty analysis

The main application of uncertainty analysis is in artificial intelligence methods such as machine learning, which may result in overly optimistic predictions due to the large data sets they use, and overfitting projections may be harmful in critical scenarios. However, the current study’s findings, which assessed the uncertainty value of four models utilized for CS and STS, are displayed in Fig. 12. For CS, as shown in Fig. 12a, the GBR model notably outperforms other models such as BR, DT, RFR, and SVR during both the training and testing phases, as it yields lower uncertainty values of approximately 0.0608 and 12.459 at the training and testing stages, respectively. Moreover, for STS, in Fig. 12b, the GBR model also provides a lower uncertainty value during the testing and training phases. Although the GBR model performs better than other models, overall, ML models provided good uncertainty value.

Fig. 12.

Bar chart of uncertainty value ML models.

The superior performance of the proposed models arises from their ability to capture the complex, non-linear behavior of BFRC datasets. Ensemble methods such as RF, GBR, and BR reduce variance and enhance stability by integrating multiple learners, effectively modeling key interactions like fiber dosage and water-to-cement ratio. SVR further contributes by handling high-dimensional feature spaces, capturing subtle patterns missed by simpler algorithms. Grid search with tenfold cross-validation ensured optimal bias-variance tradeoff, as reflected in the close agreement between training and testing R2 values. SHAP analysis further validated variable contributions, confirming the models’ robustness and interpretability.

SHAP analysis

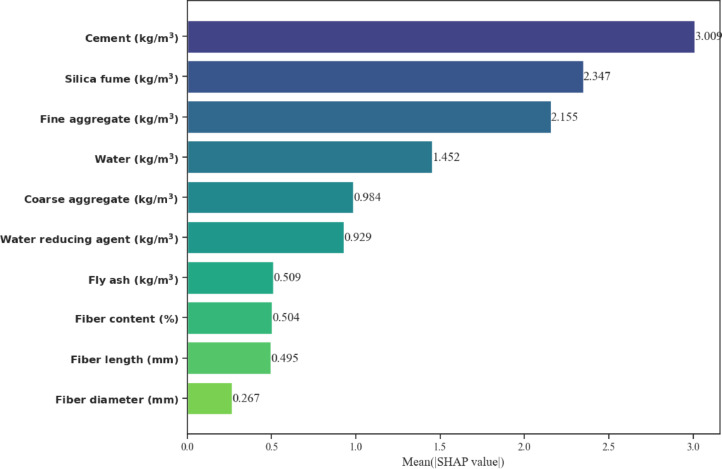

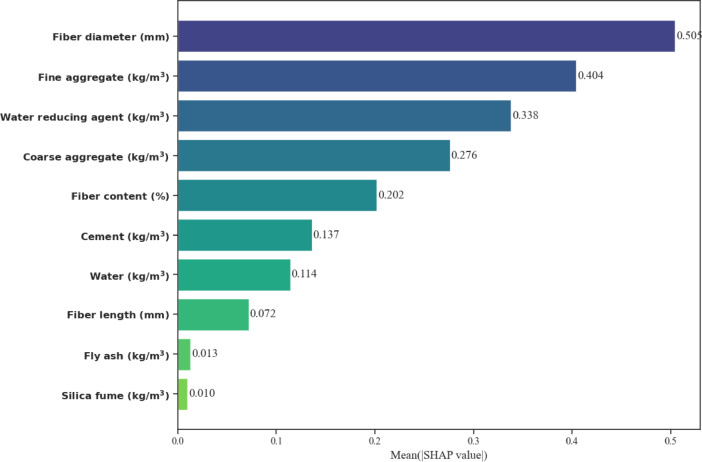

Sensitivity analysis frequently explains how an estimate is produced by comparing a dataset’s inputs and outcomes. Consequently, the SHAP technique has been used in recent studies to clarify important parameters affecting the efficacy of the CS and STS data obtained from BFRC materials. The influence of each input parameter on outputs was also depicted by the SHAP algorithm. In Figs. 13 and 14, the major influential variable can be easily identified by the mean SHAP value. According to the SHAP values, the parameter at the top has the greatest influence on the outcome, whereas the one at the bottom has the least impact. In Fig. 13, it is displayed that the cement input variable has the highest impact on the CS. It is also notable that the Silica fume, Fine aggregate, and Water input variables have a good influence on the CS. In addition, the water-reducing agent and coarse aggregate variables moderately affect the CS. However, other input parameters like Fly ash, Fiber content, Fiber length, and Fiber diameter contribute to the CS. In Fig. 14, it is shown that the highest mean SHAP value of the Fiber Diameter input variable impacts the output of splitting tensile strength. The second most influential parameter of the Fine aggregate among other parameters, with a value of almost 0.41. The Water reducing agent, Course aggregate, and Fiber content parameters moderately contribute the output STS. Most important notably, the silica fume and Fly ash are the lowest contribution parameters of the BFRC concrete.

Fig. 13.

Average absolute SHAP value with CS feature relevance.

Fig. 14.

Average absolute SHAP value with STS feature relevance.

The primary feature importance of the mean SHAP values can be used to characterize them, as indicated in Figs. 15 and 16. It is shown that each feature’s contribution to outcome prediction can be fassessed by the SHAP values. Importantly, Figs. 15 and 16 display the input parameter contributions in a similar sequence to Figs. 13 and 14, with the gradient scale indicating changes from low to high values, represented by blue to red. The model found that the cement content input parameter significantly affects the CS (Fig. 15). Cement feature values that are lower have a negative effect on CS, while those that are higher have a similar beneficial effect. It is notable that the Silica fume higher feature value of positive and a lower feature value of negative, which indicates a good influence on the CS. The Fine aggregate and Water parameters show good feature value and almost equally positive and negative influence on the CS. However, Fiber diameter Fiber length, and the Fiber content display the lowest feature value for the CS of the BFRC concrete. In Fig. 16, it is shown that the SHAP value is more displayed by the fiber diameter and Fiber aggregate variables. From the SHAP analysis, the Fiber content, cement, and Water variables moderately displayed positive and negative values, which influenced the STS. On the other hand, the minor positive and negative impact on STS of the Fly ash and silica fume parameters.

Fig. 15.

SHAP impact values to model outputs of CS.

Fig. 16.

SHAP impact values to model outputs of STS.

Cement shows the highest SHAP value for compressive strength because increased cement content produces more hydration products (C–S–H gel), densifying the concrete matrix and enhancing load-bearing capacity. Silica fume contributes via pozzolanic reactions, refining pores and increasing density. Fine aggregate improves particle packing, reducing voids, while water affects hydration and workability. For splitting tensile strength, fiber diameter and content dominate because larger or more fibers bridge cracks effectively, enhancing tensile resistance. Other inputs like fly ash and water-reducing agents have lower impact as their effects are secondary to matrix cohesion and fiber reinforcement.

Figure 17 demonstrations of the SHAP values for various concrete mix parameters, each plotted against the respective input variables. SHAP value for Cement (kg/m3) versus Cement, with the color bar reflecting the amount of water. An increase in cement content corresponds with rising SHAP values, indicating a positive relationship. Fly ash displays low correlation with SHAP values with the cement color bar, where high values (red color) for SHAP values. Silica fume content displays scattered SHAP values, with no significant trend. Coarse aggregate has a negative correlation with SHAP values, moderated by Silica fume. Fine aggregate (kg/m3) versus Fine aggregate, colored by water content. Higher Fine aggregate values are correlated with more negative SHAP values. Low water content values are more positively related to SHAP values have more positive. Water reducing agent (kg/m3) versus Water reducing agent, colored by Coarse aggregate. This relationship shows scattered SHAP values with unclear. Fiber length (mm) versus Fiber length, colored by Fly ash. As fiber length increases, the SHAP values decrease, suggesting a negative impact. Fiber content (%) versus Fiber content, colored by Fine aggregate. There is no strong correlation between Fiber content and SHAP values.

Fig. 17.

SHAP dependence plots of all input features for CS.

The SHAP analysis highlights fiber diameter as the most influential factor in STS prediction. Mechanistically, larger fiber diameters enhance stress transfer between the concrete matrix and fibers, improve crack-bridging efficiency, and increase fiber pull-out resistance, collectively contributing to higher splitting tensile strength. While fiber length affects anchorage, diameter predominantly governs the fiber’s load-bearing capacity. This insight provides practical guidance for BFRC mix design, emphasizing optimal fiber diameter selection to maximize tensile performance and structural durability.

Figure 18 shows SHAP dependence plots for each input feature in the STS. SHAP value for Cement increases positively as the cement content increases, indicating a positive effect on the model’s prediction. Higher values of Fiber length (shown in red) indicate the positive impact. Fly ash has a mixed effect on SHAP values, with no clear trend. SHAP values are scattered and show a positive relationship with Silica fume content. Coarse aggregate increases, SHAP values generally decrease, suggesting a negative correlation with the model prediction. Lower Fine aggregate with SHAP values relationship a positive impact. Higher Water content (red) appears to have a slight positive effect on the SHAP values. The water reducing agent and SHAP value are unclear. Fiber diameter shows a negative correlation, with larger fiber diameters leading to lower SHAP values. Increasing Fiber length has a slightly negative impact on the SHAP values. Fiber content increases, SHAP values also increase, indicating a positive correlation.

Fig. 18.

SHAP dependence plots of all input features for STS.

Interactive graphical user interface (GUI)

The graphical user interface plays a crucial role in enhancing the ease of use and reliability of different machine learning methods. The current research, a GUI algorithm has employed to predict the STS and CS of BFRC, as demonstrated in Fig. 19. For compressive strength (CS) prediction, GBR approaches showed superior and split tensile strength (STS) calculating SVR method was best, that were utilized to develop the graphical user interface (GUI). A Python web application was developed that integrates a machine learning model with optimized hyperparameters via a user-friendly graphical user interface (GUI). The GUI is designed to predict the CS and STS of BFRC and streamline the design process, as shown in Fig. 19. By simply clicking the “Calculate” button, users can directly obtain the predicted value. The results provided offer a significant impact on the evaluated parameters of the assessed BFRC mix design. It’s intuitively associated with streamlining intricate computational procedures, facilitating decision-making in the design of concrete mixtures and building projects.

Fig. 19.

Graphical user interface for (a) CS and (b) STS.

Practical significance

The developed models, integrated with a user-friendly GUI, provide practical benefits for building and infrastructure projects by enabling rapid estimation of BFRC compressive and splitting tensile strength without extensive laboratory testing. This accelerates mix design and quality control, allowing engineers to make timely and informed decisions. Economically, the approach reduces costs by minimizing reliance on trial-and-error experiments and optimizing fiber dosage and mix proportions, thereby preventing waste and avoiding overdesign. Environmentally, the data-driven predictions support sustainable practices through efficient material use, reducing unnecessary cement and fiber consumption and contributing to a lower carbon footprint. In terms of structural performance, accurate prediction of strength properties ensures that BFRC components can be designed with adequate safety margins and durability, enhancing the long-term reliability of infrastructure. Overall, the proposed framework demonstrates strong real-world applicability by combining accuracy, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and structural reliability.

Conclusion

This study applies machine learning (ML) algorithms to predict the compressive and splitting tensile strength of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC). The ML techniques used include Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest Regression (RFR), Decision Tree (DT), Bagging Regressor (BR), and Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR), with hyperparameter optimization carried out using grid search. A total of ten input variables were considered, with 270 data samples for compressive strength and 267 for splitting tensile strength, all sourced from previous studies. Of these, 70% were allocated for training and 30% for testing. The findings highlight the outstanding performance of the GBR model, underscoring the value of data-driven methods in enhancing the reliability and consistency of BFRC predictions. Statistical evaluation metrics were used to assess and compare the accuracy and effectiveness of the models. Based on this study, the following conclusions were drawn:

The Seaborn heatmap technique illustrates the positive and negative correlations among dataset features, revealing that the cement input parameter has a strong positive influence on both compressive strength (CS) and splitting tensile strength (STS).

From the bar normal distribution of error, it is noticeable that for CS, all machine learning models provide the error range from + 5 to − 5 at the training stage and from around + 13 to − 13 at the testing stage. From + 0.5 to − 0.5, the error ranges are found for STS at both the train and test stages. The GBR model shows the lowest error value from around + 0.5 to − 0.5, which indicates good performance for CS prediction.

Among the developed models, although the GBR model showed slightly better performance in comparison to other models, all models provided a good value of R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE for the prediction of CS and STS of the BFRC. The DT, SVR, RFR, BR, and GBR have R2 values of 0.964, 0.914, 0.981, 0.976, and 0.999 at the training stage, respectively, for CS. For STS, the R2 value is 0.962, 0.993, 0.989, 0.992, and 0.994 at the training phase of the DT, SVR, RFR, BR, and GBR, respectively.

The results indicate that over 95% of the predicted compressive strength (CS) data points for all models fall within the error margin of + 10% to − 10% and closely align with the 1:1 linear fit line. Notably, the GBR model demonstrates slightly superior performance compared to the others, as only a small number of its data points fall outside the error range.

According to the SHAP analysis, the cement input variable has the greatest impact on CS. The silica and fine aggregate input also have a good impact on CS. However, the fiber diameter input parameter has the highest effect on STS.

According to the uncertainty analysis, the GBR model displays the lowest value compared to other models, which indicates good performance.

This study introduces an innovative method that connects complex computational predictions with practical design applications by creating an intuitive GUI.

Limitations and future work

This study uses machine learning models to compare and assess the comparative performance of ML models in predicting the compressive strength (CS) and splitting tensile strength (STS) of BFRC. However, it is subject to certain limitations. The ML model’s performance depends on the quality and range of the input data and may not generalize well to datasets not represented in the training data. Additionally, future studies recommend that experimental investigations on new types of high-strength concrete should focus on compressive strength, flexural strength, tensile strength, shear strength, and other relevant properties. A comparative analysis with advanced deep learning (DL) and hybrid machine learning (ML) methods, including PDP analysis, should also be considered. Even with its acknowledged drawbacks, the results emphasize the feasibility of BFRC as a strong substitute for traditional reinforcement materials in civil engineering fields, opening the door for further studies and real-world implementations in the concrete technology and construction industry.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant No. KFU25014Y).

Abbreviations

- FRP

Fiber-reinforced polymer

- CS

Compressive strength

- UHPC

Ultra high-performance concrete

- AE

Acoustic emission

- GEP

Gene expression program

- RT

Random tree

- DT

Decision tree

- BPNN

Backpropagation neural network

- GPR

Gaussian process regression

- XGBoost

Gradient boosting

- LR

Linear regression

- RBFNN

Radial basis function neural networks

- FFNN

Feedforward neural networks

- PR

Polynomial regression

- BFRC

Basalt fiber-reinforced concrete

- FS

Flexural strength

- DIF

Dynamic increase factor

- ML

Machine learning

- RF

Random forest

- SVM

Support vector machine

- GBR

Gradient boosting regressor

- ANFIS

Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system

- KELM-GA

Kernel extreme learning machine-genetic algorithm

- SHAP

Shapely additive explanatory analysis

- RMSE

Root mean squared error

- R2

Coefficient of determination

- MAE

Mean absolute error

- MAPE

Mean absolute percentage error

Author contributions

Data curation, Abul Kashem; Formal analysis, Md Arifuzzaman and Abul Kashem; Funding acquisition, Md Arifuzzaman and Md Haque; Methodology, Abul Kashem; Project administration, Md Arifuzzaman, Md Haque, Kaffayatullah Khan and Ayed Alluqmani; Resources, Ayed Alluqmani and AKM Azad; Software, Md Haque and AKM Azad; Validation, Abul Kashem; Writing – original draft, Md Arifuzzaman and Abul Kashem; Writing – review & editing, Md Haque, Kaffayatullah Khan and Ayed Alluqmani.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant No. KFU251255).

Data availability

https:/github.com/Kashem23/Machine-learning-models-for-mechanical-properties-OF-BFRC-prediction-incorporating-GUI.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chin, S. C. et al. Predictive models for mechanical properties of hybrid fibres reinforced concrete containing bamboo and basalt fibres. Structures10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106093 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abood, E. A. et al. Machine learning-based prediction models for punching shear strength of fiber-reinforced polymer reinforced concrete slabs using a gradient-boosted regression tree. Materials10.3390/ma17163964 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basaran, B. Effect of steel–FRP ratio and FRP wrapping layers on tensile properties of glass FRP-wrapped ribbed steel reinforcing bars. Mater. Struct. Materiaux et Constr.10.1617/s11527-021-01775-x (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng, J., Yao, T., Yue, J., Wang, M. & Xia, S. Compressive strength prediction of BFRC based on a novel hybrid machine learning model. Buildings10.3390/buildings13081934 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng, J., Wang, M., Yao, T., Tang, Y. & Liu, H. Dynamic mechanical strength prediction of BFRC based on stacking ensemble learning and genetic algorithm optimization. Buildings10.3390/buildings13051155 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abed, M. A. et al. Structural performance of lightweight aggregate concrete reinforced by glass or basalt fiber reinforced polymer bars. Polymers (Basel)14, 2142. 10.3390/polym14112142 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan, Y. et al. Study on the effect of salt solution on durability of basalt-fiber-reinforced polymer joints in high-temperature environment. Polymers (Basel)14, 2250. 10.3390/polym14112250 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogrodowska, K., Łuszcz, K. & Garbacz, A. Nanomodification, hybridization and temperature impact on shear strength of basalt fiber-reinforced polymer bars. Polymers (Basel)13, 2585. 10.3390/polym13162585 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu, M. et al. Prediction of constitutive model for basalt fiber reinforced concrete based on PSO-KNN. Heliyon10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32240 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czigány, T., Vad, J. & Pölöskei, K. Basalt fiber as a reinforcement of polymer composites. Period. Polytech. Mech. Eng.49(1), 3–14 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou, H., Jia, B., Huang, H. & Mou, Y. Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of basalt fiber reinforced concrete. Materials13, 1362. 10.3390/ma13061362 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, D., Ju, Y., Shen, H. & Xu, L. Mechanical properties of high performance concrete reinforced with basalt fiber and polypropylene fiber. Constr. Build. Mater.197, 464–473. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.181 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao, C. & Wu, W. Using ESEM to analyze the microscopic property of basalt fiber reinforced asphalt concrete. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol.11, 374–380. 10.1016/j.ijprt.2017.09.010 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Askari, D. F. A. et al. Assessing the impact of pozzolanic materials on the mechanical characteristics of UHPC: Analysis, and modeling study. Discov. Civ. Eng.2, 96. 10.1007/s44290-025-00231-x (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahjoubi, S., Barhemat, R., Meng, W. & Bao, Y. AI-guided auto-discovery of low-carbon cost-effective ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) (2022).

- 16.Severcan, M. H. Prediction of splitting tensile strength from the compressive strength of concrete using GEP. Neural Comput. Appl.21, 1937–1945. 10.1007/s00521-011-0597-3 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang, M. C., Yoo, D. Y. & Gupta, R. Machine learning-based prediction for compressive and flexural strengths of steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121117 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta, S. & Sihag, P. Prediction of the compressive strength of concrete using various predictive modeling techniques. Neural Comput. Appl.34, 6535–6545. 10.1007/s00521-021-06820-y (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parhi, S. K. & Patro, S. K. Application of R-curve, ANCOVA, and RSM techniques on fracture toughness enhancement in PET fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater.411, 134644. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134644 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, H., Lin, J., Zhao, D., Shi, G., Wu, H., Wei, T., Li, D. & Zhang, J. A BFRC compressive strength prediction method via kernel extreme learning machine-genetic algorithm (2022). https://www.elsevier.com/open-access/userlicense/1.0/

- 21.Hasanzadeh, A., Vatin, N. I., Hematibahar, M., Kharun, M. & Shooshpasha, I. Prediction of the mechanical properties of basalt fiber reinforced high-performance concrete using machine learning techniques. Materials10.3390/ma15207165 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Askari, D. F. A., Shkur, S. S., Rafiq, S. K., Hilmi, H. D. M. & Ahmad, S. A. Prediction model of compressive strength for eco-friendly palm oil clinker light weight concrete: A review and data analysis. Discov. Civ. Eng.10.1007/s44290-024-00119-2 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parhi, S. K., Dwibedy, S. & Patro, S. K. Managing waste for production of low-carbon concrete mix using uncertainty-aware machine learning model. Environ. Res.10.1016/j.envres.2025.121918 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad, D. A., AlGoody, A. Y., Askari, D. F. A., Ahmad, M. R. J. & Ahmad, S. A. Evaluating the effect of using waste concrete as partial replacement of coarse aggregate in concrete, experimental and modeling. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil.10.1007/s41024-024-00521-4 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad, S. A., Ahmed, H. U., Rafiq, S. K., Jafer, F. S. & Fqi, K. O. A comparative analysis of simulation approaches for predicting permeability and compressive strength in pervious concrete. Low-Carbon Mater. Green Constr.10.1007/s44242-024-00041-x (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almohammed, F. & Soni, J. Using random forest and random tree model to predict the splitting tensile strength for the concrete with basalt fiber reinforced concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci.10.1088/1755-1315/1110/1/012072 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sapkota, S. C., Yadav, A., Khatri, A., Singh, T. & Dahal, D. Explainable hybridized ensemble machine learning for the prognosis of the compressive strength of recycled plastic-based sustainable concrete with experimental validation. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des.7, 6073–6096. 10.1007/s41939-024-00567-4 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cakiroglu, C. et al. Explainable ensemble learning data-driven modeling of mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced rubberized recycled aggregate concrete. J. Build. Eng.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107279 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abushanab, A., Wakjira, T. G. & Alnahhal, W. Machine learning-based flexural capacity prediction of corroded RC beams with an efficient and user-friendly tool. Sustainability (Switzerland)10.3390/su15064824 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng, D. C., Wang, W. J., Mangalathu, S., Hu, G. & Wu, T. Implementing ensemble learning methods to predict the shear strength of RC deep beams with/without web reinforcements. Eng. Struct.10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.111979 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen, D., Li, M., Kang, J., Liu, C. & Li, C. Experimental studies on the seismic behavior of reinforced concrete beam-column joints strengthened with basalt fiber-reinforced polymer sheets. Constr. Build Mater.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122901 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoque, M. A., Shrestha, A., Sapkota, S. C., Ahmed, A. & Paudel, S. Prediction of autogenous shrinkage in ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) using hybridized machine learning. Asian J. Civ. Eng.26, 649–665. 10.1007/s42107-024-01212-8 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sapkota, S. C. et al. Optimizing high-strength concrete compressive strength with explainable machine learning, multiscale and multidisciplinary modeling. Exp. Des.10.1007/s41939-025-00737-y (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng, Y. & Unluer, C. Modeling the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete using hybrid machine learning algorithms. Resour. Conserv. Recycl.10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106812 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang, X., Dai, C., Li, W. & Chen, Y. Prediction of compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete using machine learning and Bayesian optimization methods. Front. Earth Sci. (Lausanne)10.3389/feart.2023.1112105 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sapkota, S. C. et al. Enhancing shear strength predictions of UHPC beams through hybrid machine learning approaches. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-025-13444-y (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sapkota, S.C., Sapkota, S. & Saini, G. Prediction of split tensile strength of recycled aggregate concrete leveraging explainable hybrid XGB with optimization algorithm (2024). 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4019630/v1

- 38.Parhi, S. K. & Patro, S. K. Compressive strength prediction of PET fiber-reinforced concrete using Dolphin echolocation optimized decision tree-based machine learning algorithms. Asian J. Civ. Eng.25, 977–996. 10.1007/s42107-023-00826-8 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Najmoddin, A., Etemadfard, H., Hosseini, A. & Ghalehnovi, S. M. Multi-output machine learning for predicting the mechanical properties of BFRC. Case Stud. Constr. Mater.10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02818 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei, Z. W. et al. Study of the flexural behavior of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete beams with basalt fiber-reinforced polymer bars and steel bars. Case Stud. Constr. Mater.10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04433 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duranay, Z. B., Aslan Topçuoğlu, Y. & Gürocak, Z. Estimation of compressive strength of basalt fiber-reinforced kaolin clay mixture using extreme learning machine. Materials10.3390/ma18020245 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, X., Ke, Z., Liu, W., Zhang, P., Cui, S. & Zhao, N. Compressive strength prediction of basalt fiber reinforced concrete based on interpretive machine learning (2024). 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4493851/v1

- 43.Ikeagwuani, C. C. Estimation of modified expansive soil CBR with multivariate adaptive regression splines, random forest and gradient boosting machine. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut.10.1007/s41062-021-00568-z (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben Jabeur, S., Gharib, C., Mefteh-Wali, S. & Ben Arfi, W. CatBoost model and artificial intelligence techniques for corporate failure prediction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120658 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoang, N. D. Machine learning-based estimation of the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete: A multi-dataset study. Mathematics10.3390/math10203771 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fawagreh, K., Gaber, M. M. & Elyan, E. Random forests: From early developments to recent advancements. Syst. Sci. Control Eng.2, 602–609. 10.1080/21642583.2014.956265 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bbeiman, L. Bagging predictors (1996).

- 48.Nasir Amin, M. et al. Prediction model for rice husk ash concrete using AI approach: Boosting and bagging algorithms. Structures50, 745–757. 10.1016/j.istruc.2023.02.080 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Erdal, H. I. Two-level and hybrid ensembles of decision trees for high performance concrete compressive strength prediction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell.26, 1689–1697. 10.1016/j.engappai.2013.03.014 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ben Chaabene, W., Flah, M. & Nehdi, M. L. Machine learning prediction of mechanical properties of concrete: Critical review. Constr. Build. Mater.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119889 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang, J., Sun, Y. & Zhang, J. Reduction of computational error by optimizing SVR kernel coefficients to simulate concrete compressive strength through the use of a human learning optimization algorithm. Eng. Comput.38, 3151–3168. 10.1007/s00366-021-01305-x (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alabduljabbar, H. et al. Modeling the capacity of engineered cementitious composites for self-healing using AI-based ensemble techniques. Case Stud. Constr. Mater.18, e01805. 10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01805 (2023). [Google Scholar]