Abstract

Introduction and importance

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for approximately 2 % of adult malignancies, with clear-cell RCC being the most common histological subtype. Metastasis to the breast is extremely rare, particularly in male patients, and may mimic benign breast lesions, creating diagnostic challenges.

Presentation of case

We report the case of a 55-year-old male with a history of left nephrectomy for clear-cell RCC (pT3aN0M0) who presented three years later with a painless nodule in the left breast. Imaging revealed a well-circumscribed hypoechoic mass classified as BI-RADS 3. Wide local excision was performed, and histopathology with immunohistochemistry confirmed breast metastasis from renal clear-cell carcinoma. No adjuvant systemic therapy was administered, and the patient remains disease-free on follow-up.

Clinical discussion

Breast metastases from extramammary malignancies are uncommon and typically occur in women. In men, they are exceptionally rare and often mistaken for benign conditions such as gynecomastia. Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses are crucial to distinguish metastasis from primary breast carcinoma. For selected patients with oligometastatic or oligo-recurrent disease, complete metastasectomy may offer prolonged disease control and defer systemic therapy.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of considering breast metastasis in male patients with a history of extramammary malignancy. Accurate histopathological diagnosis is essential, and in selected cases, surgical excision can be an appropriate management strategy.

Keywords: Renal clear-cell carcinoma, Breast metastasis, Oligo-recurrent renal cell carcinoma (RCC), Case report

Highlights

-

•

Breast metastasis from renal clear-cell carcinoma is rare (0.36% of RCC cases) and exceptional in men.

-

•

The lesion mimicked a benign breast tumor and may easily cause confusion in diagnosis.

-

•

Metachronous oligo-recurrent RCC show indolent progression; metastatic sites and IMDC risk predict prognosis.

-

•

In these patients, active surveillance, metastasectomy, and SBRT are all appropriate options.

1. Introduction

According to GLOBOCAN 2022, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for 5.9 % and 3 % of all cancers in males and females, respectively, ranking 10th and 13th among all malignancies [1]. RCC represents approximately 2 % of all adult malignancies, with renal clear-cell carcinoma accounting for about 75 % of cases [2]. At time of diagnosis, 30 % of patients present with metastases, and an additional 30 % will eventually develop metastatic disease [3]. Common metastatic sites include the lungs (45.2 %), bones (29.5 %), lymph nodes (21.8 %), liver (20.3 %), adrenal glands (8.9 %), and brain (8.1 %) [4]. Metastasis to the breast from RCC is extremely rare, though several cases have been documented globally [[5], [6]]. Most of these reports describe unilateral, solitary breast metastases, primarily in female patients, with the breast sometimes being one among multiple metastatic sites.

Male breast cancer is exceedingly rare, accounting for approximately 0.98 % of all breast cancer cases [7]. Metastasis from extra-mammary malignancy to the breast in men is even rarer, with the most common primary sites including the prostate, lung, stomach, colonrectal, melanoma, and sarcoma. Rare cases of metastatic bladder cancer to the male breast have also been reported [8]. Metastasis of renal clear-cell carcinoma to the male breast is exceptionally uncommon. In previous reports, breast metastases from renal cell carcinoma in female patients often exhibited features resembling benign breast tumors. Whether this characteristic also applies to male patients remains uncertain. Importantly, breast lesions in men with a history of extramammary malignancy should never be underestimated.

Herein, we report a case of isolated recurrent renal clear-cell carcinoma metastasizing to the left breast in a male patient who had undergone left nephrectomy about three years prior. To our knowledge, this is the first such case reported in Vietnam. This report was written in accordance with the Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) criteria [9].

2. Case presentation

A 55-year-old male underwent a routine health check-up more than two years ago, during which an abdominal ultrasound revealed a 4 × 5 cm mass in the left kidney, and he was subsequently diagnosed with kidney cancer. He underwent left nephrectomy at our hospital in November 2022. Histopathological analysis confirmed renal clear-cell carcinoma, stage pT3aN0M0 (tumor invasion into renal sinus fat). The patient did not receive adjuvant immunotherapy due to financial constraints. He had no other comorbidities, and there was no family history of breast or kidney cancer.

Following surgery, the patient was monitored regularly—every three months during the first postoperative year, then every six months thereafter. Routine follow-ups revealed chronic kidney disease, which was managed medically, with no evidence of local recurrence or distant metastasis. Notably, the breast region was not examined during these follow-ups, as breast metastasis was not suspected.

In March 2025, the patient presented to my hospital after palpating a painless mass in his left breast during bathing. There was no nipple discharge or pain. Ultrasound of the left breast revealed a well-circumscribed hypoechoic nodule measuring 11 × 17 mm with no abnormal axillary lymph nodes (Fig. 1). The lesion was categorized as BI-RADS 3, indicating a probably benign finding. A contrast-enhanced CT scan showed enhancement of the lesion (Fig. 2) but no other suspicious findings in the chest or abdomen.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound imaging of the patient's left breast lesion revealed a well-defined hypoechoic mass.

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed a nodule with enhancement in the left chest wall.

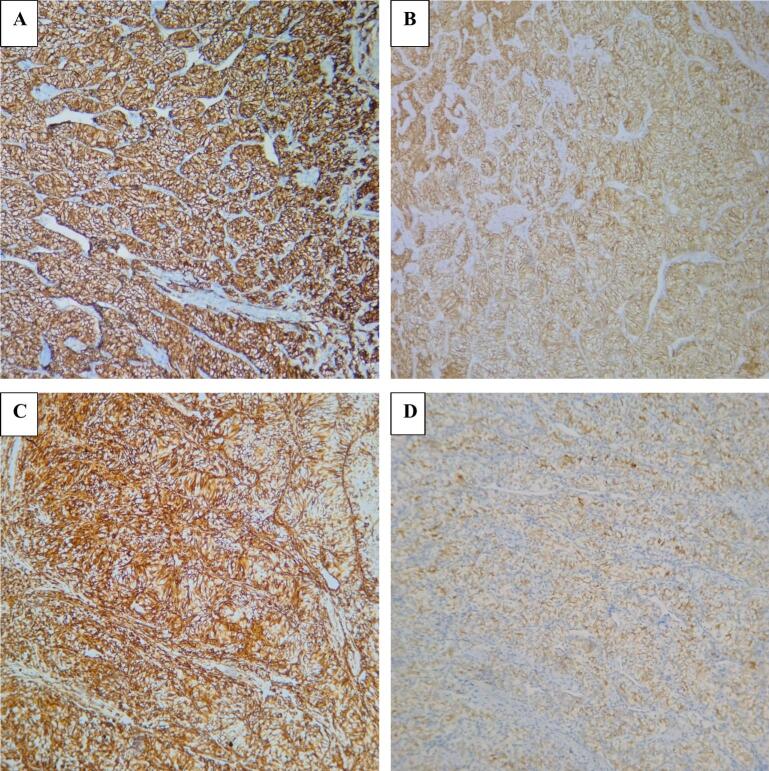

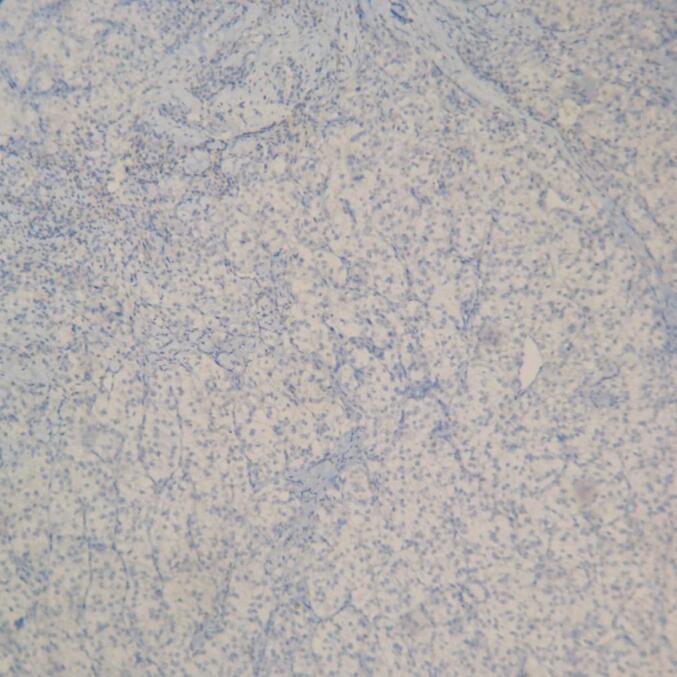

The core needle biopsy was inconclusive. Because clinical and radiological findings suggested a benign process, we performed wide local excision for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. However, intraoperative frozen section examination failed to determine the exact n This highlights the need for cautious interpretation ature of the lesion. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed proliferation of round to polygonal epithelial cells with small nuclei and clear cytoplasm, arranged in clusters or surrounding hyperplastic ductal structures (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD10, Vimentin, CAIX, and RCC marker, PAX8 and negative for GATA3, CK20, CK7 confirming the diagnosis of breast metastasis from renal clear-cell carcinoma (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Microscopically, the tumor was composed of polygonal or round epithelial cells arranged in lobules and nests, surrounded by a high-density vascular network. The tumor cells had clear cytoplasm with small nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli (H&E x100).

Fig. 4.

(A) The tumor cells showed strong and diffuse expression of CD10. (B) Membranous immunopositivity for CAIX was seen. (C) The tumor cells were immunoreactive for vimentin. (D) RCC staining was weakly positive.

Fig. 5.

Staining for GATA3 was not present.

No adjuvant systemic therapy was administered following surgical excision. Follow-up to date has revealed no evidence of disease recurrence.

3. Discussion

Breast metastases from extramammary malignancies are rare and occur mainly in females. The most common primary tumors associated with such metastases are melanoma, lymphoma, and lung cancer [10]. Estrogen may enhance vascularization and stromal components of the breast, potentially promoting the metastatic process [11,12]. Consequently, breast metastases in male patients are even less common, with the most frequent origin being prostate cancer [13]. Most male breast lesions are benign, with gynecomastia being the most common cause [14]. Thus, even in patients with a known history of extramammary malignancy, new breast masses in males are rarely suspected to be metastatic. Differentiating metastatic breast lesions from primary breast tumors can be clinically challenging. Metastases to the breast can occur via hematogenous or lymphatic routes. Sonographic features of hematogenous metastases typically include one or more hypoechoic masses that are round to oval in shape, well-circumscribed, non-spiculated, and without calcifications. These lesions are often located in the superficial subcutaneous tissue or adjacent to the relatively vascularized parenchyma. In contrast, lymphatic metastases are characterized by diffuse, heterogeneous hyperechogenicity of subcutaneous fat and glandular tissue, associated with skin thickening, lymphatic edema, and axillary lymphadenopathy [15]. Our patient presented similarly, with a well-circumscribed hypoechoic lesion and a BI-RADS 3 classification. Therefore, we decided to perform surgical excision of the mass along with intraoperative frozen section analysis. At that time, we believed the lesion was most likely benign. However, the frozen section analysis was inconclusive and only revealed an epithelial-like tumor of undetermined type. Consequently, we opted to widen the surgical margins and await the final histopathological results. At our institution, patients can routinely undergo core needle biopsy of breast lesions prior to any surgical intervention. Nevertheless, given our initial impression that the lesion was highly likely benign, we proceeded with wide local excision without prior biopsy. This underscores the importance of carefully evaluating breast lesions that appear benign in patients with a history of extramammary malignancy.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses were critical in determining the tumor's origin. Microscopically, the tumor cells exhibited clear cytoplasm with distinct membrane, surrounded by a network of arborizing small vessels. Ultrastructural examination shows that the clear or pale appearance results from abundant intracytoplasmic glycogen and lipids. Although clear cell RCC have typical morphology, the diagnosis of a metastatic renal tumor should be carefully confirmed using specific immunohistochemical markers. In our case, the tumor cells were positive for CD10, PAX8 and RCC marker,CAIX and negative for GATA3, CK7, and CK20, consistent with a diagnosis of metastasis from renal clear-cell carcinoma. PAX8 is expressed in epithelial cells of all nephron segments, from the proximal tubules to the renal papilla, as well as in the parietal cells of Bowman's capsule in adult kidneys. PAX8 is positive in 98 % of RCCs and 85 % of metastatic renal tumors [16]. Recent studies indicate that PAX8 is a highly specific marker for both primary and metastatic RCC (mRCC) [17]. The RCC marker is a monoclonal antibody targeting antigens specific to normal proximal renal tubules, with relatively high specificity for clear cell RCC. It is not expressed in other types of clear cell carcinoma (e.g., ovarian, endometrial) [18]. GATA3 is expressed in 80–90 % of primary and metastatic breast carcinomas and can also be present in urothelial carcinomas; however, it was negative in our case [19]. CD10, a cell surface metalloproteinase localized to the proximal nephron in adult kidneys, is a useful diagnostic marker for RCC, especially in clear cell and papillary subtypes, but not in chromophobe RCC. CD10 is found in 100 % of clear cell RCC, 63 % of papillary RCC, and the majority of their metastases [20].

Breast metastasis from renal clear-cell carcinoma is exceedingly rare. Gravis et al. (2016) reported breast metastases in only 2 out of 558 metastatic RCC patients (0.36 %) [21]. Our patient was found to have a solitary breast metastasis nearly three years after nephrectomy. Previous reports indicate that the interval from RCC diagnosis to breast metastasis can range from months to years, with some cases occurring up to 18 years later [22]. In addition to renal clear-cell carcinoma, other renal tumors such as renal adenocarcinoma and renal carcinoid tumor have also been reported to metastasize to the breast [22].

As previously discussed, estrogen may contribute to the higher frequency of breast metastases in female patients, as it promotes stromal proliferation and vascularization in breast tissue. This potentially makes the breast a more favorable site for metastatic tumor cells. However, breast metastases are more frequently reported in females during puberty, pregnancy, or lactation, as well as in males with prostate cancer undergoing hormone therapy [23].

Renal clear-cell carcinoma exhibits diverse clinical behavior, ranging from slow-growing localized tumors to aggressive metastatic disease. The International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) has identified six prognostic factors for metastatic RCC: time from diagnosis to systemic therapy <1 year, Karnofsky performance status <80 %, anemia (hemoglobin <120 g/L), neutrophilia, thrombocytosis, and hypercalcemia. Patients are categorized into favorable (0 risk factors), intermediate (1–2 risk factors), and poor (≥3 risk factors) prognostic groups [24]. These criteria are also incorporated into the recommendations of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. Our patient had no risk factors, corresponding to a median overall survival of 43 months per the IMDC model. However, there are no specific data regarding the prognosis of breast metastases. Some authors suggest that breast metastasis from extramammary malignancies reflects advanced disease and portends a poor prognosis [14]. Assalli et al. (2001) reported a median survival of only 10.9 months [25]. In general, patients with metastatic renal clear-cell carcinoma have poor prognoses, with 2-year survival rates between 10 % and 20 % [5].

Currently, there are no specific guidelines for the management of recurrent RCC in general, nor for cases of oligometastatic recurrence. According to the NCCN, treatment for recurrent RCC should follow the same principles as for stage IV disease. Therapeutic options include metastasectomy, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), or other forms of ablative metastasis-directed treatment, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [26]. Guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) further suggest that active surveillance may be considered in carefully selected patients with oligometastasis, particularly those with indolent tumor behavior. Suitable candidates include patients with favorable or intermediate IMDC risk, minimal or no disease-related symptoms, favorable histological features, long disease-free intervals following nephrectomy, and low metastatic burden [27]. However, these patients require close and careful follow-up.

Our patient experienced an oligo-recurrent metastasis after a relatively long disease-free interval (more than one year) following curative nephrectomy. Patients with similar presentations often show indolent progression, for whom several management strategies remain viable, including metastasectomy and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT). In our case, the patient had a small tumor located in the left chest wall, which had not invaded any critical structures and was amenable to complete surgical excision. Therefore, to avoid potential radiation-induced toxicity to the heart, surgery was considered a reasonable treatment option in this patient.

In the management of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), surgery provides clinical benefit even in metastatic settings. Cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) prior to systemic therapy may be considered in selected patients with stage IV disease when the primary tumor is resectable. In cases of oligometastatic disease, the NCCN also recommends managing metastatic lesions with metastasectomy, both in patients presenting with synchronous metastases and in those with metachronous lesions appearing after nephrectomy [26].

The ASCO distinguishes oligometastatic RCC (defined as 1–5 metastatic sites) from oligoprogressive RCC, in which a limited number of sites progress during systemic therapy. Both CN and complete metastasectomy are recommended for appropriately selected patients in these categories [28]. The goal is complete resection of all metastatic disease (potentially curative), and such patients may have a favorable prognosis. More recently, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) has emerged as an alternative metastasis-directed approach to surgery, showing promising clinical outcomes in selected patients.

CN and metastasis-directed therapies can delay the initiation of systemic treatment by an average of one year, with 20–30 % of patients achieving long-term disease control without the need for systemic therapy [29]. The efficacy of perioperative systemic therapy for metastatic clear cell RCC remains unclear. During both the cytokine therapy era and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) era, clinical trials failed to demonstrate a significant benefit from combining systemic therapy with surgery [28]. Over the past decade, immunotherapy has become the standard of care for patients with metastatic RCC, prompting several trials investigating immune checkpoint inhibitors in the adjuvant setting, including IMmotion010, PROSPER, and KEYNOTE-564. Among these, only the KEYNOTE-564 trial has shown positive results to date.

Based on the above data, adjuvant pembrolizumab could be considered for our patient. However, after discussion in a multidisciplinary tumor board including surgeons, medical oncologists, pathologists, and radiologists, we noted several important factors. First, our patient was classified as having a favorable risk according to the IMDC criteria. Second, overall survival (OS) outcomes in this study remain inconclusive. Third, pembrolizumab therapy represents a substantial financial burden for patients in Vietnam. Therefore, we decided to defer systemic treatment and continue with active surveillance: chest–abdominal CT scans and bilateral breast ultrasonography at 6 months, followed by annual evaluations thereafter. To date, no signs of recurrence have been detected in this patient.

4. Conclusion

We report a rare case of solitary breast metastasis from renal clear-cell carcinoma in a male patient, which posed a significant diagnostic challenge. Clinicians should consider metastasis in any new breast lesion in patients with a history of extramammary malignancy, and histopathological confirmation is crucial. In selected cases with oligo-recurrence and indolent progression, metastasectomy may serve as an appropriate treatment strategy.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request. The manuscript is carefully reviewed to avoid patient identification details and/or figures.

Ethical approval

This case report was approved by the Ethics Committee.

Guarantor

Dung Anh Hoang.

Research registration number

This is not an original research project involving human participants in an intervantional or observational study but a case report. This registration was not required.

Methods

Work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contribution

Dung Anh Hoang, Quang Hong Le: Performed surgery and provided treatment for the patient; revised the manuscript.

Dinh Van Vu: Provided treatment and follow-up care for the patient; drafted the manuscript.

Anh Quang Nguyen: Provided patient care and revised the manuscript.

Cuong Manh Thieu: Reviewed the patient's pathology slides and revised the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Bray F., Laversanne M., Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Soerjomataram I., et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024;74:229–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bukavina L., Bensalah K., Bray F., Carlo M., Challacombe B., Karam J.A., et al. Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma: 2022 update. Eur. Urol. 2022;82:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchi M., Sun M., Jeldres C., Shariat S.F., Trinh Q.-D., Briganti A., et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in renal cell carcinoma: a population-based analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23:973–980. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singla A., Sharma U., Makkar A., Masood P.F., Goel H.K., Sood R., et al. Rare metastatic sites of renal cell carcinoma: a case series. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022;42:26. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2022.42.26.33578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mečiarová I., Pohlodek K. Breast metastasis from a renal clear-cell carcinoma: a rare case report and a complex review of literature. Bratisl Med J. 2025 doi: 10.1007/s44411-025-00153-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elouarith I., Bouhtouri Y., Elmajoudi S., Bekarsabein S., Ech-charif S., Khmou M., et al. Breast metastasis 18 years after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjac116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metastasis pattern and prognosis of male breast cancer patients in US: a population-based study from SEER database - PubMed n.d. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31798694/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Bladder cancer metastasis to the breast in a male patient: imaging findings on mammography and ultrasonography. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 2022;83:687–692. doi: 10.3348/jksr.2021.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revised Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guideline: An Update for the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Premier Science n.d. https://premierscience.com/pjs-25-932/ (accessed June 29, 2025).

- 10.Ali H.O.E., Ghorab T., Cameron I.R., Marzouk A.M.S.M. Renal cell carcinoma metastasis to the breast: a rare presentation. Case Rep. Radiol. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6625689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S.H., Park J.M., Kook S.H., Han B.K., Moon W.K. Metastatic tumors to the breast: mammographic and ultrasonographic findings. J. Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:257–262. doi: 10.7863/jum.2000.19.4.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergier B., Trojani M., de Mascarel I., Coindre J.M., Le Treut A. Metastases to the breast: differential diagnosis from primary breast carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 1991;48:112–116. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930480208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berge T. Metastases to the male breast. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. A Pathol. 1971;79A:491–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1971.tb01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Önder Ö., Azizova A., Durhan G., Elibol F.D., Akpınar M.G., Demirkazık F. Imaging findings and classification of the common and uncommon male breast diseases. Insights Imaging. 2020;11:27. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0834-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mun S.H., Ko E.Y., Han B.-K., Shin J.H., Kim S.J., Cho E.Y. Breast metastases from extramammary malignancies: typical and atypical ultrasound features. Korean J. Radiol. 2014;15:20–28. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2014.15.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong G.-X., Yu W.M., Beaubier N.T., Weeden E.M., Hamele-Bena D., Mansukhani M.M., et al. Expression of PAX8 in normal and neoplastic renal tissues: an immunohistochemical study. Mod. Pathol. 2009;22:1218–1227. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barr M.L., Jilaveanu L.B., Camp R.L., Adeniran A.J., Kluger H.M., Shuch B. PAX-8 expression in renal tumours and distant sites: a useful marker of primary and metastatic renal cell carcinoma? J. Clin. Pathol. 2015;68:12–17. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perna A.G., Ostler D.A., Ivan D., Lazar A.J.F., Diwan A.H., Prieto V.G., et al. Renal cell carcinoma marker (RCC-ma) is specific for cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2007;34:381–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cimino-Mathews A., Subhawong A.P., Illei P.B., Sharma R., Halushka M.K., Vang R., et al. GATA3 expression in breast carcinoma: utility in triple-negative, sarcomatoid, and metastatic carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 2013;44:1341–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martignoni G., Pea M., Brunelli M., Chilosi M., Zamó A., Bertaso M., et al. CD10 is expressed in a subset of chromophobe renal cell carcinomas. Mod. Pathol. 2004;17:1455–1463. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gravis G., Chanez B., Derosa L., Beuselinck B., Barthelemy P., Laguerre B., et al. Effect of glandular metastases on overall survival of patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma in the antiangiogenic therapy era. Urol. Oncol. 2016;34(167) doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.10.015. e17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y., Hou R., Lu Q., Deng Y., Hu B. Renal clear cell carcinoma metastasis to the breast ten years after nephrectomy: a case report and literature review. Diagn. Pathol. 2017;12:76. doi: 10.1186/s13000-017-0666-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toombs B., Kalisher L. Metastatic disease to the breast: clinical, pathologic, and radiographic features. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1977;129:673–676. doi: 10.2214/ajr.129.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.IMDC | International mRCC Database Consortium. IMDC | International mRCC Database Consortium 2022. https://www.imdconline.com (accessed May 19, 2025).

- 25.Vassalli L., Ferrari V.D., Simoncini E., Rangoni G., Montini E., Marpicati P., et al. Solitary breast metastases from a renal cell carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2001;68:29–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1017990625298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . 2025. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Kidney Cancer. Version 3.2025. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Management of Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: ASCO Guideline | Journal of Clinical Oncology n.d. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.22.00868 (accessed June 22, 2025).

- 28.Dason S., Lacuna K., Hannan R., Singer E.A., Runcie K. State of the art: multidisciplinary management of oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2023 doi: 10.1200/EDBK_390038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews J.R., Lohse C.M., Boorjian S.A., Leibovich B.C., Thompson H., Costello B.A., et al. Outcomes following cytoreductive nephrectomy without immediate postoperative systemic therapy for patients with synchronous metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. 2022;40:166.e1–166.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2022.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]