Abstract

Caspases are a family of cysteine proteases conserved across all metazoa which play critical functions that range from cell death, inflammation, and cellular differentiation. Caspases cleave a subset of protein substrates after aspartic acid residues, which subsequently defines cellular consequences. Inflammatory caspases are a subfamily of caspases which are activated by signaling platforms known as inflammasomes, which are assembled upon sensing of diverse sterile and microbial stimuli. Upon their activation, inflammatory caspases generate a potent inflammatory response that is critical to control infections and maintain homeostasis but can also drive numerous pathologies. Increasing amount of literature identified inflammatory caspase activity as a promising target for the treatment of these diseases. As such, a robust understanding of inflammatory caspase activation, substrate selectivity, and wider functions is critical to aid the development of therapeutics. In this review, we provide a holistic overview of inflammatory caspase activation, activity, and signaling, highlighting the biochemical features controlling these elements.

Keywords: Caspase, protease signaling, inflammation, inflammasome, cell death

The discovery of caspases

The term “Caspase” (Cysteine ASPartate-specific proteASE) was initially assigned to a family of cysteine proteases that were characterized by their unique ability to specifically cleave cellular substrates after aspartate residues (1). The first human caspase identified (Caspase-1) was initially described in 1992 by two groups, whose work identified a novel cysteine protease which acted as an interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme (ICE) to cleave the proinflammatory cytokine pro-IL-1β into its mature form (2, 3). The following year, CED-3, a paralogous protein of ICE, was found to play key roles in apoptosis within Caenorhabditis elegans (4, 5). This link between ICE and CED-3 initiated a historic search within the scientific community to identify the other mammalian CED-3 homologs, which would later be rebranded as the caspase family (1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). While originally appreciated for their role in programmed cell death, the role of caspases in inflammation, cell differentiation, and innate immunity has since been unveiled (16).

#1- Caspases play central roles in the execution of programmed cell death pathways such as apoptosis (pronounced ‘apo-tosis’). The term ‘Apoptosis’ is derived from a Greek term which means 'falling off (of leaves from a tree)’ (17). Inflammatory caspases specifically drive an inflammatory form of cell death known as pyroptosis, which means ‘fiery falling’ in Greek.

The human caspase family

In humans, there are 12 members of the caspase family which can be divided into three main subfamilies, each grouped based on their physiological roles, similarities in domain structure, and activation mechanisms (Fig. 1). The first subfamily is the initiator caspases, consisting of caspase-2, -8, -9, and -10, which initiate apoptotic signaling pathways, leading to downstream activation of a second subfamily, the executioner caspases (caspase-3, -6, and -7). Upon their activation by initiator caspases, executioner caspases cleave a vast range of substrates which leads to cellular demise via apoptosis (18, 19, 20, 21). In addition to their position in apoptotic signaling cascades, differences between initiator and executioner caspases lie in their activation mechanisms and domain structure. Initiator caspases are activated by proximity-induced dimerization following recruitment to signaling hubs via their N-terminal death effector domain or caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD). Conversely, executioner caspases exist as pre-formed dimers and are activated following interdomain linker (IDL) processing by initiator caspases, and lack an N-terminal recruitment domain (22, 23, 24).

Figure 1.

The human caspase family. A, Domain organisation of the human caspase family. Catalytic cysteine residues are highlighted in red, and the interdomain-linker processing sites are highlighted in black. The amino acid length of each caspase is indicated. B, Phylogenetic analysis of the human caspase family, with each caspase coloured in accordance with its subfamily depicted in panel ‘A’. Evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and JTT matrix-based model (268). The presented tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Phylogenetic tree drawn using MEGA11 (269).

The final subfamily, and the focus of this review, is the inflammatory caspases, composed of caspase-1,-4, and -5 in humans, which together orchestrate an innate immune response by processing inactive pro-inflammatory mediators into their mature form, resulting in cytokine release, and a highly inflammatory form of programmed cell death, known as pyroptosis (25). Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) are two potent pro-inflammatory cytokines that, when secreted, amplify the inflammatory response by inducing the expression of other pro-inflammatory mediators such as IFNγ within immune cells (26, 27). Both IL-1β and IL-18 are expressed within the cytosol as inactive protein precursors (pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18), where they await processing by inflammatory caspases before being secreted from the cell (28, 29, 30). In addition to pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, inflammatory caspases process gasdermin D (GSDMD), releasing its bioactive N-terminal fragment (N-GSDMD), which assembles into pores at the plasma membrane, facilitating the release of IL-1β and IL-18 and onset of pyroptosis via NINJ1-mediated membrane rupture (29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39). Inflammatory caspases share properties of both initiator and executioner caspases in that they both require, and mediate their dimerization and IDL processing to gain full catalytic activity (30, 40, 41).

Other human caspases, which do not fit into the three main subfamilies, include caspase-12 and caspase-14. The CASP12 gene is located proximal to the inflammatory caspase gene cluster and has a similar domain architecture to the inflammatory caspases (42). However, in the majority of the human population, caspase-12 contains a single-nucleotide polymorphism, resulting in a truncated polypeptide that lacks both catalytic subunits (43). In addition, even in full-length caspase-12 variants, the mutation of a conserved glycine (G231S) within the SHG box, which is critical for catalytic activity, predicts that full-length caspase-12 is inactive (44, 45, 46). As there is no supportive evidence that suggests either the full-length or truncated caspase-12 variants are active or play a significant role in humans, caspase-12 is instead classified here as a non-functional pseudogene. Another human caspase which does not fit into these subfamilies is caspase-14, which is also unique due to its atypical activation mechanisms and role in keratinocyte differentiation through filaggrin cleavage (47, 48).

In this review, we consolidate our understanding of the biochemistry, activation, and signaling of the human inflammatory caspases to date, and direct readers to outstanding reviews covering the other human caspases in detail (19, 24, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53). In order to facilitate structural and sequence comparisons between caspases, residue and fold nomenclature will be in accordance with the system used in (52), which uses amino acid numbering from human caspase-1 as reference, unless otherwise stated.

#2- The genomic locus and domain structure of caspase-12 suggest it had primitive roles as an inflammatory caspase. However, due to the acquisition of mutations which eliminate its catalytic activity, caspase-12 has no known functions in humans (44, 54, 55).

Inflammatory caspase biochemistry and structure

Caspase catalysis

Caspases are cysteine proteases members of the C14 peptidase clan CD and use a unique catalytic mechanism to cleave their substrates (56). They utilize a cysteine–histidine catalytic dyad to undergo nucleophilic attack on the C-terminal peptide bond of aspartate (57) (Fig. 2A). Although unclassical, caspases have also been shown to cleave natural and synthetic substrates after glutamate and phosphoserine residues, albeit with reduced efficiency (58). As with other cysteine proteases, the cysteine-histidine catalytic dyad functions by increasing the nucleophilicity of the sulfur within the cysteine by the nearby histidine abstracting the thiol hydrogen (59). Activation of the catalytic sulfur atom within the cysteine permits hydrolysis of the peptide bond by attack on the carbonyl carbon. This nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the peptide bond leads to the formation of an unstable tetrahedral intermediate anion, which is transiently stabilized by an oxyanion hole (60). Within caspases, formation of an oxyanion hole is essential to lower the activation energy for this reaction and is orchestrated by hydrogen bonding between backbone nitrogen’s from the conserved G238, catalytic cysteine (C285), and the carbonyl oxygen of the cleaved aspartate. Upon collapse of the tetrahedral intermediate and deprotonation of the scissile bond by the catalytic histidine (H237), the cleaved peptide is released from the active site.

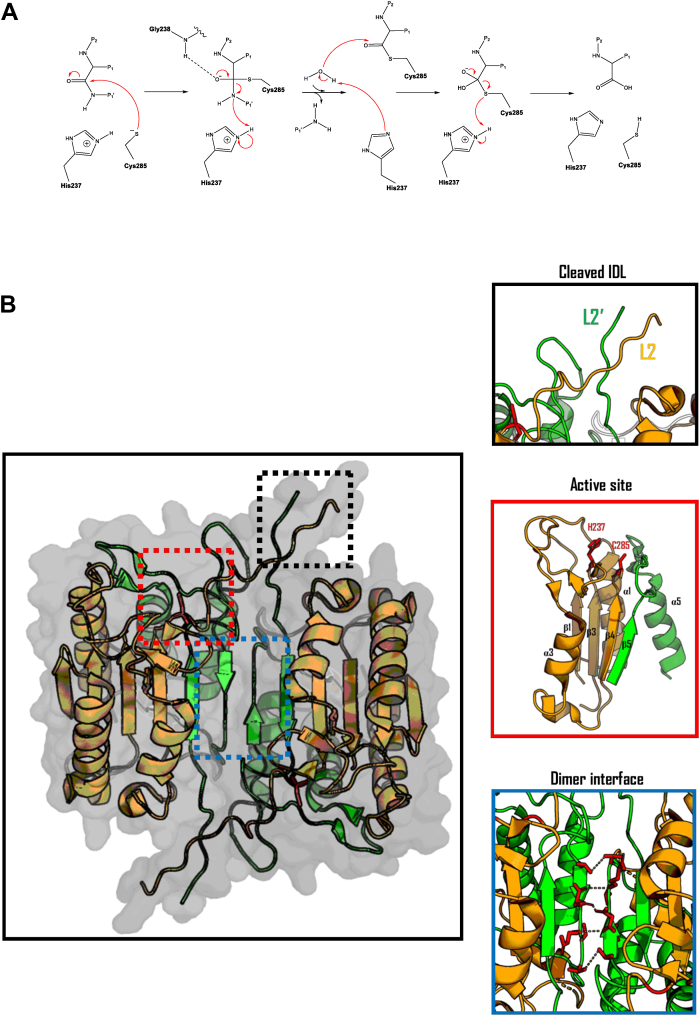

Figure 2.

Biochemical and structural basis for inflammatory caspase activity.A, Proposed catalytic mechanism of human caspase-1 (270). B, Ribbon representation of the catalytic domain of the human caspase-1 heterotetramer (PDB: 2H51) with the large and small catalytic subunits highlighted in orange and green, respectively.

Domain structure

Under resting state, inflammatory caspases exist in the cell as inactive monomers with a tripartite structure, consisting of an N-terminal CARD domain, followed by the large, and small catalytic subunits. The latter two form a caspase-hemoglobinase fold that comprises the catalytic domain of the enzyme (61, 62). The catalytic domain of all active caspases consists of the large and small catalytic subunits, which are typically compacted into a six-stranded, twisted β-sheet structure, sandwiched between five α-helices (52). The central β-sheet is composed of parallel strands except for the final β strand, which runs antiparallel. The final C-terminal β-strand is involved with stabilization of the caspase dimer interface, by aligning with the corresponding β-strand on the second caspase monomer in an antiparallel fashion. Together, these central β-strands form a 12-stranded β-sheet core within the caspase dimer (Fig. 2B). Each subunit of the caspase is connected by flexible linker regions which are susceptible to proteolysis (52). The interdomain linker (IDL) connects the large and small catalytic subunits, and undergoes autoproteolysis during inflammatory caspase activation, giving rise to a non-covalently associated heterodimeric caspase species. This heterodimeric caspase species exists as part of a homodimer with another IDL-processed caspase monomer, together forming a catalytically active heterotetramer, composed of a homodimer of heterodimers (30, 63). Cleaved IDL loops (known as Loop L2 and L2′) interact with the other dimer unit through hydrophobic interactions to stabilize the active site (64). Conversely to the IDL, autoproteolysis at the CARD-domain linker (CDL), which connects the catalytic domain to the CARD domain, results in the dissociation of the caspase heterotetramer from its cellular activation platform, resulting in loss of its homodimeric status at cellular concentrations, and termination of catalytic activity (63, 65). Despite the CARD domain being essential for inflammatory caspase activation and stability in cells, removal of the CARD domain in vitro does not result in termination of activity, due to the caspase heterotetramer being stabilized in a concentration-dependent manner.

Active site architecture

The conserved caspase fold sees the active site being positioned within the looped regions of the β-strands which are within an open α/β structure (62). This catalytic fold is uniquely embedded to caspases, hemoglobinases, paracaspases, metacaspases, and gingipains (66, 67). Importantly, the location of the catalytic residues within enzymes harboring this caspase fold is at conformational switch points, which, for caspases, are on the connecting loop regions of β-strands that form the central β-core. Specifically, the catalytic residues are situated on loops where flanking β-strands lead to helices at opposite sides of the enzyme (52, 68) (Fig. 2B). The location of the active site at these switch points underpins the mechanisms of caspase activation and the requirement of a prior conformational change in the active site-forming loops, induced by dimerization, to activate the catalytic residues within the protease (69, 70). Dimerization of caspases also induces rearrangement of the IDL, which typically obscures the substrate binding pocket in monomeric caspases (69). Dimerization-induced rearrangement of the IDL permits its autoprocessing and subsequent formation of the substrate binding pocket seen in active caspase heterotetramers (52). Accordingly, the longer IDL in initiator and inflammatory caspases is suggested to underpin their ability to acquire basal activity following dimerization, which is further enhanced by IDL processing (71, 72, 73, 74, 75) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Structurally informed sequence alignment of the human caspase family catalytic domains (271, 272, 273, 274). Alignment was performed using T-COFFEE (274), and structurally informed on ESPRIPT3 with PDB: 1IBC, using the default settings (275). Fully conserved residues are highlighted in red, with partially conserved residues highlighted in yellow.

#3- Inflammatory caspases are thought to have first evolved around 500 million years ago, however, the conserved caspase-hemoglobinase fold, which underpins their proteolytic function, is around one billion years old and can be found in all domains of life (76, 77).

Inflammatory caspase substrate recognition

Inflammatory caspases recognize a substrate tetrapeptide sequence (P4-P1, according to the Schechter-Berger nomenclature (78)) to mediate nucleophilic attack at the C-terminal side of the P1 residue (79). Early work on understanding inflammatory caspase substrate specificity stemmed primarily from work on synthetic peptide libraries, which disclosed the tetrapeptide preferences of each caspase (58, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84). Compiled efforts to decipher the substrate specificity of the inflammatory caspases revealed WEHD as the preferred tetrapeptide substrate for caspase-1, with W/L-E-H/V-D being optimal for caspase-4 and -5 (79, 81, 83, 85). During proteolysis, the tetrapeptide sequence occupies the substrate-binding pocket within the caspase, which is composed of four subsites (S4-S1), positioning the scissile bond within the active site (82). Structural investigations into caspases, which were irreversibly inhibited by tetrapeptide-based inhibitors, revealed the mechanistic basis for inflammatory caspase substrate specificities (59, 86, 87, 88) (Fig. 4A).

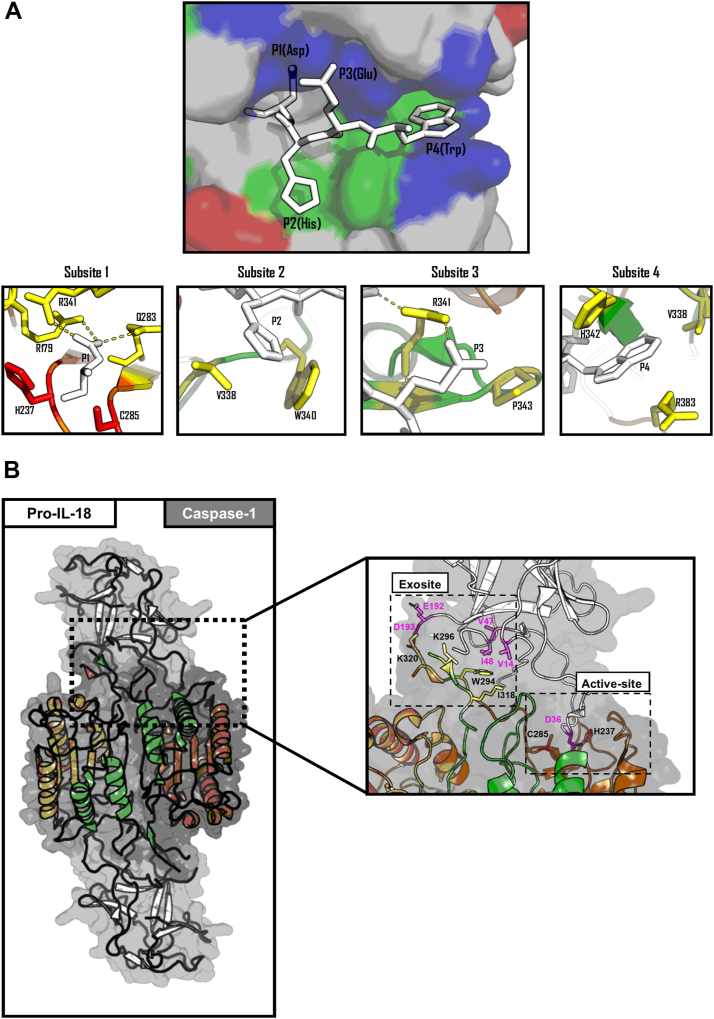

Figure 4.

Biochemical basis of inflammatory caspase specificity. A, top panel, stick representation of a WEHD tetrapeptide (white) engaging the substrate-binding pocket of human caspase-1 (PDB:1IBC). The caspase-1 active site is represented as surface charges with positive regions in blue, negative regions in red, and hydrophobic regions in green, bottom panel, close-up stick representation of each of the caspase-1 subsites engaging the WEHD tetrapeptide (white). Catalytic residues C285 and H237 (in red), with functional residues at each caspase-1 substrate colored in yellow. B, Ribbons and sticks representation of human caspase-1 (orange and green) in complex with pro-IL-18 (white) (PDB: 8SV1). The large and small catalytic subunits of the caspase-1 heterotetramer are colored in green, with the catalytic residues C285 and H237 colored in red, exosites residues in yellow, and caspase-engaging pro-IL-18 residues in pink—figure produced in PyMOL 3 (276).

Subsite 1 (S1)

The architecture of subsite one is conserved across all caspases and permits recognition of P1 aspartate residues with exquisite specificity. Side chains from three conserved residues (R179, R341, and Q283) form a deep highly basic pocket which accommodates the negatively charged side chain of aspartate residues (89). Some caspases have also been shown to tolerate glutamate and phosphoserine at P1 due to them also harboring acidic side chains, however presence of these residues at P1 dramatically reduces catalytic efficiency (58, 80, 81).

Subsite 2 (S2)

Unlike subsite 1, subsites 2 to 4 demonstrate much more variability across caspases, offering a large diversity of substrate preference between different caspase subfamilies (82, 86, 90). The S2 subsite binding pocket of inflammatory caspases and initiator caspases is composed of small aliphatic residues (V338 in inflammatory caspases) and can accommodate a range of residues, with a particular preference for a P2 histidine. The increase in affinity for P2 histidine arises from a combination of the S2 subsite being larger in inflammatory caspases, which helps to accommodate the histidine side chain, and the formation of electrostatic and hydrophobic contacts between the indole side chain of W340 and the imidazole of the P2 histidine (86). Conversely, in the executioner caspases, the S2 subsite is composed of bulky aromatic residues, which results in these caspases having a preference for smaller aliphatic residues and disfavoring bulky P2 residues (80).

Subsite 3 (S3)

In addition to playing roles in the formation of the highly basic S1 subsite, R341 plays essential roles in tethering the substrate to the substrate-binding pocket mediated by backbone hydrogen bonding with P3 residues. All caspases have a higher affinity for substrates which contain a P3 glutamate residue due to additional interactions resulting between the guanidinium group of the conserved R341 and the carboxylate of a P3 glutamate (79, 80, 81, 82, 91). Other S3 subsite factors that can influence the tetrapeptide specificity of caspases include the presence of proximal basic residues within the S3 subsite pocket. Notably, a substitution from P177 to arginine within caspase-8 and caspase-9, which borders the S3 subsite pocket, allows for increased affinity for substrates containing a P3 glutamate (71, 90, 91). Indeed, while a similar P177R substitution is observed in many inflammatory caspase homologues, the presence of proline in the human inflammatory caspases obscures this increased affinity for a P3 glutamate.

Subsite 4 (S4)

Subsite four contains the most determining factors that distinguish tetrapeptide preferences between the caspase subclasses. S4 of the inflammatory caspases consists of a shallow, hydrophobic cleft constituted by isoleucine or valine residues (V/I348), which allows for optimal recognition of P4 residues harboring large aromatic side chains such as tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine (79, 80). In caspase-1, H342 and R383 also engage the P4 residue; however, amino substitutions for aspartate (H342D) and lysine (R383K) in caspase-4 and -5 possibly alter the nature of this interaction, likely explaining the discrepancy in additional preference for leucine in P4 by caspase-4 and -5. In contrast, the S4 of initiator and executioner caspases harbors a larger tryptophan, which reduces the ability to accommodate bulky P4 residues, resulting in an alternate preference for smaller P4 residues (15, 89, 92, 93).

Subsite 1′

While peptide libraries have offered huge insights into the optimal tetrapeptide sequences for inflammatory caspases, during proteolysis of native protein substrates, the residues following P1, denoted as P1′-4′, can also determine caspase substrate specificities (80, 94). For inflammatory caspases, a preference for small residues such as glycine, serine, and alanine has been shown to be optimal in the P1′, with most other residues also being tolerated, with the exception of proline and certain charged residues, which were found to be unfavorable (79, 80).

Exosites

Structural analyses of inflammatory caspases in complex with their native protein substrates GSDMD and pro-IL-18 have revealed insights into additional mechanisms employed by inflammatory caspases to recognize cellular substrates independent of their tetrapeptide sequence (95, 96, 97, 98, 99). Exosites are interfaces outside of the substrate-binding pocket, which allow caspases to specifically recognize a cellular substrate and serve as an additional determinant of substrate specificity (100). In addition to playing a role in auto-inhibition of the bioactive N-terminal domain (NTD) of GSDMD, the C-terminal domain (CTD) of GSDMD has been found to contain a hydrophobic pocket that is recognized by an inflammatory caspase exosite. The residues that comprise the exosite in caspase-1 are W294, I318, and K320, and are only fully exposed within the active species of inflammatory caspases (97). Similarly, inflammatory caspases engage pro-IL-18 via a pocket located within the pro-domain of pro-IL-18, using the same exosite used for GSDMD recognition with additional electrostatic interactions resulting from K296, or arginine in the case of caspase-4 and -5 (95, 96, 98) (Fig. 4B). Caspase-7 also utilizes an exosite consisting of hydrophobic residues to cleave poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) with greater efficiency than caspase-3, despite caspase-7 being less catalytically active and having a similar tetrapeptide specificity to caspase-3 (100). Interestingly, for GSDMD, the exosite seems to be the sole factor that determines specificity, with the identity of P4-P2 of the tetrapeptide having no effect on GSDMD processing (97, 99). On the contrary, pro-IL-18 appear to also depend on the tetrapeptide for their efficient processing by inflammatory caspases (101). Curiously, the exosite interface appears to be partially dispensable for pro-IL-18 processing by caspase-1, but is indispensable for caspase-4 and -5, indicating that caspase-1 may be slightly less dependent on the exosite for processing certain substrates (98). However, in all cases, perturbation of residues involved at the exosite interface on either the caspase or substrate appears to compromise, or at least, reduce the ability for caspases to recognise and process their substrates. Given the recency of structural insights into substrate cleavage by caspases, which revealed the importance of exosites in substrate recognition, it is highly likely that inflammatory caspases utilize exosites to recognise and enhance proteolysis for a plethora of other substrates. Indeed, exosites have been previously shown to enhance both the substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency of caspase-6 and numerous other proteases (102, 103, 104, 105, 106).

#4- Achieving selectivity with inhibitors that target the caspase active site has been challenging, due to structural conservation across the caspase family (107, 108). However, unlike the active site, the exosite is unique to the inflammatory caspases and has been targeted successfully for the inhibition of numerous other exosite-containing proteases (109, 110).

Activation of inflammatory caspases by inflammasomes

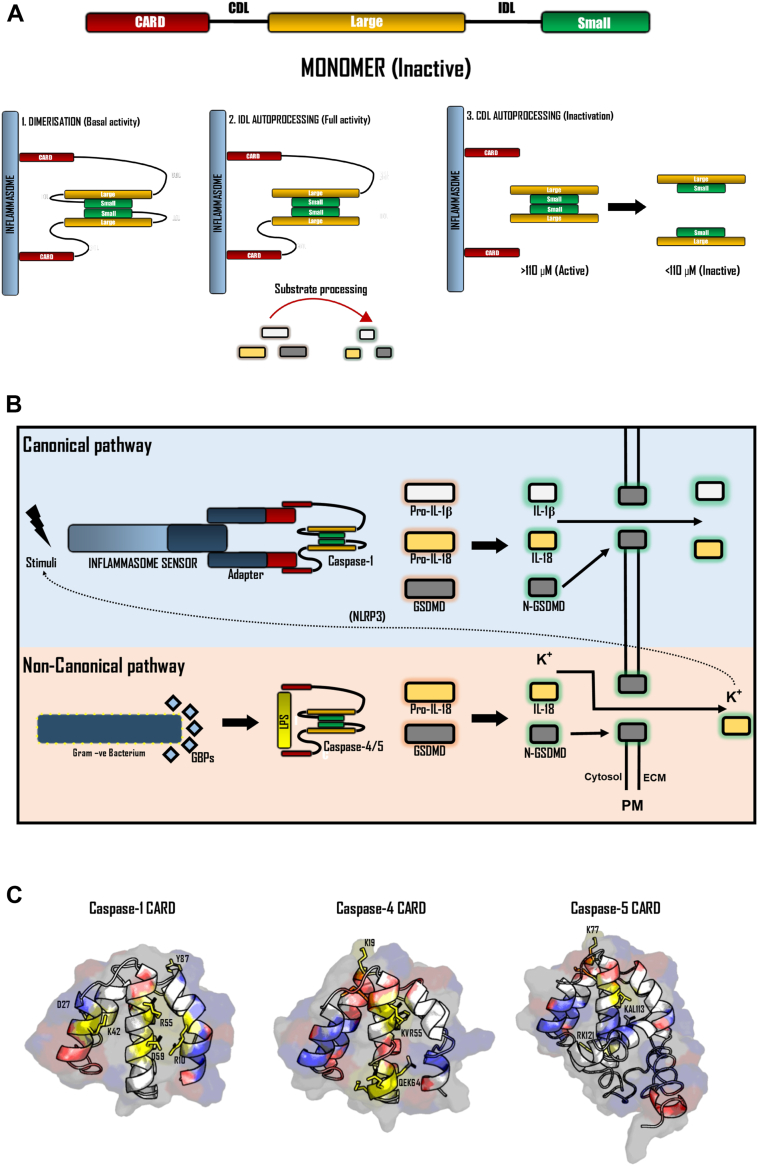

Inflammatory caspase activation occurs via a two-step mechanism (70, 111). The first step is proximity-induced dimerization between two full-length caspase momoners, which is facilitated by their recruitment to signaling hubs known as inflammasomes (63, 111). Caspases are recruited to the inflammasome via homotypic interactions through their N-terminal CARD domain (112, 113). Dimerization confers basal inflammatory caspases activity, enabling the second step of activation, which is IDL autoprocessing. Autoprocessing of the IDL fully exposes the substrate-binding pocket, enabling maximal proteolytic activity and the cleavage of substrates (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Activation of the inflammatory caspases. An overview of the proximity-induced activation model for inflammatory caspases. A, Caspases first undergo dimerization following recruitment to the inflammasome via their CARD domain. Following dimerization, IDL autoprocessing results in complete activity and the ability to cleave cellular substrates. CDL processing results in termination of caspase activity by releasing the heterotetramer from the inflammasome and becoming unstable at cellular concentrations. B, Overview of canonical and NCI pathways. Canonical inflammasome signaling occurs following activation of an inflammasome sensor protein in response to its activation stimulus. Activation of an inflammasome sensor results in the recruitment of an adapter protein via PYD-PTYD interactions, which in turn oligomerises and recruits caspase-1 via CARD-CARD interactions. Peroximity-induced activation of caspase-1 results in substrate processing and the onset of pyroptosis. The NCI results in the activation of caspase-4 and -5 via interactions with LPS, which is facilitated by GBPs forming a coat on cytosolic gram-negative bacteria. Caspase-4 and -5 efficiently process GSDMD and pro-IL-18, resulting in GSDMD pore formation and the release of IL-18, DAMPs, and potassium ions. Potassium ion efflux can then result in engagement of the canonical inflammasome pathway via the NLRP3 axis. C, Ribbon representation of iTASSER predicted structures of the inflammatory caspase CARD domains with the proposed functional residues (ASC-binding), highlighted in yellow and surface charges highlighted in blue (positive) and red (negative) (275, 276). Figure produced in PyMol3. ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD; CARD, caspase activation and recruitment domain; DAMP, danger-associated molecular pattern; GBP, guanylate-binding protein; GSDMD, gasdermin D; NCI, noncanonical inflammasome; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PYD, pyrin domain.

Activation step 1: Dimerization

Dimerization of caspases is only favored when the local concentration of caspase monomers is sufficiently high. At endogenous cellular concentrations (∼10 nM for caspase-1), inflammatory caspases remain monomeric and inactive due to their dimer dissociation constant exceeding their endogenous concentrations (63, 72, 114, 115, 116). However, upon recruitment to inflammasomes via their CARD domain, the local increase in caspase concentration (∼110 μM for caspase-1) favors caspase dimerization and their subsequent activation. Clustering of caspase monomers at inflammasomes results in dimerization of their catalytic domains (52), leading to conformational transitions within each individual catalytic domain. These conformational changes within the protease domain result in the formation of the complete caspase catalytic domain, and activation of the active site (two per dimer). Dimerization is facilitated and stabilized by hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding between conserved residues spanning the β6 strand on the small subunit (41, 59, 61, 68, 88, 117). Mutation of key residues within this dimer interface eliminates caspase activity by preventing formation of the catalytically active protease dimer (59, 72). Accordingly, mutation of the conserved R371 in caspase-4, which participates in key electrostatic interactions at the dimer interface of caspase-4, resulted in the failure to clear an otherwise opportunistic Burkholderia pseudomallei infection without medical intervention (118).

Activation step 2: Autoprocessing

Following dimerization and formation of the full catalytic domain, the caspase acquires basal protease activity and undergoes autoprocessing. Autoprocessing can occur at multiple sites within the IDL and CDL, each with varying consequences. Processing of the IDL occurs after dimerization and leads to full activation of the caspase, by fully exposing the active site and substrate-binding pocket (30, 40, 63). Inflammatory caspases contain multiple cleavage sites within their IDL. For both caspase-1 and caspase-4, autoprocessing can occur at two sites within the IDL (D297 and D316) and are both required to acquire full protease activity (30, 98, 99). Interestingly for caspase-4, processing at both sites is required for efficient cleavage of GSDMD and pyroptotic cell death; however, processing at D289 or D270 individually results in caspase-4 species with differential substrate processing efficiencies (30, 96). For example, autoprocessing at D289 but not D270 results in a caspase-4 species is also able to which process pro-IL-1β (30, 98, 99), albeit less efficiently than caspase-1 (96). This heterogeneity suggests that the site in which caspase IDL autoprocessing occurs may play a role in modulating the substrate repertoire of caspase species. Indeed, while IDL autoprocessing is required to acquire full proteolytic activity and execute pyroptosis via GSDMD cleavage, dimeric unprocessed inflammatory caspases are still catalytic competent, and have been shown to have the capacity to mediate GSDMD-independent cell death by poorly characterized mechanisms (40, 75, 119). In contrast to the IDL, processing at the CDL leads to the termination of caspase activity and signaling (63). Processing of the CDL ejects the catalytically active caspase dimer from the inflammasome and in doing so destabilizing the caspase’s tetrameric structure. In this model, caspase activity is locally and temporally restricted to the inflammasome and serves as a method to minimize promiscuous cleavage of ‘bystander’ caspase substrates, whose cleavage may result in less desirable outcomes for the cell (115). Indeed, it is not yet clear what determines when the CDL cleaved or if other proteases are also able to process the CDL to regulate caspase activity. Current hypotheses suggest that the kinetics of CDL autoprocessing is dependent on numerous factors, including the size and number of inflammasomes, the concentration of full-length caspase monomers within a cell, and the relative availability of substrates (63, 120).

#5-: Inflammatory caspases are technically not “pro-enzymes”. The term “pro-enzyme” is typically used to describe enzymes that require processing to gain proteolytic activity. Although the term “pro-caspase” is often used in the literature to describe the unprocessed enzyme, dimeric inflammatory caspases have been shown to possess basal proteolytic activity without the requirement for autoprocessing, meaning they are not pro-enzyme by definition (40, 63, 75).

The inflammasomes

Inflammasomes are signaling complexes that are assembled in response to danger signals and mediate the recruitment and activation of inflammatory caspases. They can be divided into two subtypes (canonical and non-canonical), which are based on the caspase they recruit and activate. ‘Canonical’ inflammasomes assemble and recruit caspase-1 in response to various danger signals (121, 122). Conversely, the ‘non-canonical’ inflammasome refers to a signaling hub that assembles on the surface of intracellular gram-negative bacteria, which recruits and activates caspase-4 and -5 (123, 124, 125, 126) (Fig. 5B).

Canonical inflammasomes

All canonical inflammasomes are principally composed of a sensor protein which is activated following sensing of specific danger cues (127), an adapter protein, which is recruited to the sensor protein, and caspase-1 (128, 129). Each canonical inflammasome is classified based on the identity of the initial sensor protein which is activated in response to sensing of a danger cues (112). The mechanisms of danger cues sensing are diverse across inflammasomes, and can either be via direct binding to pathogen/danger-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs/DAMPs), sensing of alterations in homeostatic processes (130), or by downstream signal transduction. For example, NAIP/NLRC4, AIM2, and NLRP6 inflammasomes are able to sense PAMPs and DAMPs directly (131, 132, 133, 134), whereas most other canonical inflammasomes are activated downstream of stimulus sensing (128, 129). The NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing (NLRP) family constitutes the majority of inflammasome sensors and are characterized by a central NACHT domain which drives conformational change upon activation (135), leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) which are involved with ligand sensing, and N-terminal CARD domain or pyrin domains (PYD). Among the NLR family inflammasome sensors, NLRP3 is the most well documented due to its biological significance and widespread implication in inflammatory disease (136). NLRP3 activation has been observed in response to a vast range of both microbial and sterile cues (137, 138, 139, 140). Although its exact activation mechanism is subject to debate, most current models support the role of potassium ion efflux from the cell as a crucial upstream event for its activation (141, 142, 143, 144). Interestingly, NLRP1, which was the first inflammasome that was described, was shown to activate both caspase-1 and -5, although the functions played by caspase-5 in canonical inflammasome signaling have not been explored further (113). In addition to the NLR-family inflammasome sensors, there are other notable inflammasome sensors which do not comprise the NLR family including AIM2, PYRIN and CARD8. The AIM2 inflammasome contains a C-terminal hematopoietic interferon-inducible nuclear (HIN) domain which facilitates direct sensing of cytosolic double-stranded DNA and an N-terminal PYD domain to facilitate adaptor protein recruitment (132, 133). The PYRIN inflammasome is activated through indirect sensing of cytoplasmic perturbations as a result of infection (145). Finally, the CARD8 inflammasome, which is somewhat unique due to its ability to recruit caspase-1 directly via CARD-CARD interactions, in response to sensing of viral protease activity (146, 147).

Upon activation of most inflammasomes, conformational changes within the inflammasome sensor lead to the formation of higher-order helical structures (128, 145, 148, 149). This activation of inflammasome sensors results in the recruitment and filamentation of the adapter protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), through PYD-PYD interactions (133, 149, 150, 151, 152). These filamentous ASC oligomers which are bound to activated inflammasome sensors, can be visualized by microscopy as puncta known as ‘ASC specks’, and are often used as a hallmark of inflammasome activation (151, 152, 153, 154). In addition to harboring a PYD domain to facilitate its own recruitment to the inflammasome, ASC also contains a CARD domain, which is then used to cluster caspase-1 monomers on the inflammasome via CARD-CARD interactions (155, 156, 157). NLRC4 is another adapter protein that can nucleate on NAIP inflammasome sensors to recruit caspase-1 either indirectly through ASC or independently via its own CARD domain (158, 159, 160). Conversely, some inflammasomes, such as CARD8, are able to recruit caspase-1 directly via CARD-CARD interactions, without the need for any adapter proteins (146, 147). Nonetheless, in each case, clustering of caspase-1 monomers on an inflammasome enables proximity-induced dimerization and subsequent activation of caspase-1 (111, 152).

#6- Humans encode 22 different NLR-family sensor proteins, with only eight being shown to activate caspase-1 to date (112). The exact function of many of the remaining NLR-family proteins has yet to be established.

The non-canonical inflammasome

Whereas canonical inflammasomes govern the activation of caspase-1, the non-canonical inflammasome (NCI) refers to a signaling platform that mediates the recruitment and activation of caspase-4 and caspase-5. The NCI is a protein-lipid assembly which is directly formed on the surface of intracellular gram-negative bacteria or outer membrane vesicles derived from these bacteria (123, 161, 162, 163). Once the bacterium enters the cytosol of a host cell, the CARD domain of caspase-4, and presumably caspase-5, mediates their recruitment to the bacterial surface, through interaction with the lipid A portion of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (123, 125, 164). This ability for caspase-4 to recognize intracellular LPS depends on the prior recruitment of interferon-inducible GTPases, known as guanylate-binding proteins (GBPs) which assemble on the surface of cytosolic bacteria to facilitate recruitment and activation of caspase−4 (124, 126, 165, 166, 167, 168). Immediately following release of bacteria into the cytosol, GBP1 is recruited to the bacterial surface and forms a coat of GBP1 dimers on the bacterial outer membrane, mediated by electrostatic interactions with LPS (169). Docking of GBP1 onto LPS initiates the recruitment of additional factors to the NCI, such as GBP2-4, and caspase-4. The mechanistic details of how GBP1 facilitates the recruitment of additional factors to the bacterial membrane are unclear, however is likely to occur by disruption of the O-antigen of LPS to improve accessibility of the lipid A antigen, which is typically buried at the basal layer of the bacterial outer membrane (166, 170). Whilst caspase-5 has been shown to be activated by outer membrane vesicles, whether caspase-5 is directly recruited to these platforms has yet to be demonstrated (171, 172).

#7- Unlike caspase-1 and -4 which are constitutively expressed in most cells, caspase-5 expression is limited to certain cell-types and is the only inflammatory caspase whose expression is LPS- or interferon-inducible (173).

Inflammatory caspase CARD domains

The inflammatory caspase CARD domains share a conserved globular death-domain fold found in the death-domain superfamily but mostly lack sequence identity (19% sequence identity) (152, 156, 174, 175). The canonical death-domain fold consists of 5 to 7 alpha helices which together form a globular ‘Greek key motif’, which contains a hydrophobic core and a high percentage of surface charged residues (176, 177) (Fig. 5C). These charged residues drive the striking phenotypic differences across the inflammatory caspase CARD domains. In the case for the caspase-1 CARD domain, multiple surface charged and hydrophobic residues (R10, D27, K42, R55, D59, and Y82) drive recruitment of caspase-1 monomers to ASC-dependent inflammasomes (156, 178). In vitro analysis of the caspase-1 CARD domain suggests that these residues drive hetero-oligomerization of the caspase-1 CARD domain with ASC/NLRC4 into helical filaments, mediating proximity induced-dimerization and activation (157). Additionally, the presence of CARD-only proteins (COPs) within the human genome, which mimic the inflammatory caspase CARD domain can exert inhibitory effects on inflammatory caspase activation (156, 179, 180). CARD16, CARD17, and CARD18 are COPs which are exclusively expressed in higher mammals, and have been suggested to compete with the caspase-1 CARD domain for recruitment to the inflammasome by disrupting caspase oligomerization (156, 179, 181, 182). Unlike caspase-1, the CARD domains of caspase-4, and presumably -5, mediate recruitment to the surface of gram-negative bacteria via direct interaction with LPS, a large glycolipid found on the outer membrane of all gram-negative bacteria (123, 125, 164). This unique property of the caspase-4 CARD domain suggests caspase-4 can act as both a sensor and effector in the NCI pathway (125). The surface charged residues which mediate this distinct interaction in caspase-11, the murine homologue of caspase-4 and -5, have been proposed to involve three patches on the CARD domain (K19, KRW54, and KKK64 in caspase-11). Intriguingly, although activation of caspase-4 and -5 via transfection of LPS is well documented (125, 164, 183, 184), only three of the seven positions identified as critical for caspase-11 LPS binding are conserved in caspase-4 and -5, suggesting that caspase-4 and -5 may employ alternative mechanisms of LPS binding (Fig. 3). More recently, the CARD domain of caspase-4 and -5 homologues were shown to specifically bind phosphate groups and long acyl chains, both of which are present in the lipid A portion of LPS (185). Although no structure has been published to decipher the exact mechanism of this interaction, molecular simulations identified a hydrophobic groove orchestrated by a phenylalanine residue (F76 in caspase-4), which was suggested to mediate this interaction (185). Interestingly, the most abundant caspase-5 splice variant contains a 52 amino acid extension onto its CARD domain, which is predicted to have partial helical secondary structure (Fig. 5C). Whether this N-terminal extension permits any differential ability in LPS binding between caspase-4 and -5 remains elusive. Indeed, studies have suggested that caspase-5 may have some functions independent of caspase-4 (172, 186).

#8- The most abundant caspase-5 splice variant contains a 52 amino acid extension onto its CARD domain, which is absent in caspase-1 and -4, likely affecting caspase-5 activation.

Proteolytic signaling by inflammatory caspases

The functions carried out by inflammatory caspases are inextricably linked to their substrate repertoire, which varies across cell types, and disease states. Inflammatory caspases process specific protein substrates which subsequently define the nature of the response generated. In this section, we highlight both notable and putative substrates of the inflammatory caspases and detail the downstream consequences of their processing.

GSDMD

GSDMD is part of a family with five other pore-forming gasdermins (GSDMA, GSDMB, GSDMC, GSDME, and PJVK), each of which consisting of an N- and C- terminal domain (NTD and CTD, respectively), separated by a flexible linker region susceptible to proteolysis (187, 188). GSDMD is recognized and cleaved at D275 by all members of the inflammatory caspases using an exosite-dependent mechanism (189, 190). Following caspase processing, the GSDMD NTD is liberated from the autoinhibitory CTD and undergoes conformational transitions, exposing basic residues, which permits interaction with acidic phospholipids present on the plasma and mitochondrial membranes (34, 35). Upon membrane binding, the GSDMD-NTD undergoes a second conformational change which permits insertion into the inner leaflet and oligomerization into pores (39, 191). Despite not contributing to its bioactivity, the CTD of GSDMD functions as an auto-inhibitor of the NTD and contains the exosite which mediates its recognition by inflammatory caspases (97, 99). Upon pore formation, electrostatic interactions within the GSDMD pore enhance the export of mature cytokines, DAMPs and potassium ions (39, 192, 193). Efflux of potassium ions through NCI-dependent GSDMD pore formation enables secondary downstream activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and caspase-1 (186, 194). In neutrophils, GSDMD pores formed by NCI signaling results in the secretion of antimicrobial neutrophil extracellular traps, enhancing the clearance of bacterial infections (195). In addition to the inflammatory caspases, caspase-8 has been shown to cleave GSDMD at D275 under certain conditions to induce pyroptosis, albeit with reduced efficiency (196, 197, 198). Although GSDMD pores result in significant cell swelling, these pores are typically not sufficient to cause plasma membrane rupture and cell death. Instead, the transmembrane protein NINJ1 facilitates membrane lysis, and completion of pyroptotic cell death (199).

IL-1 cytokines

Pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 were the first inflammatory caspase substrates to be characterized and provided the initial link between inflammatory caspase functions and the innate immune response (2, 3, 200). All human inflammatory caspases have been observed to cleave both pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, however there are clear differences in the efficiencies of processing. Each of the inflammatory caspases process pro-IL-18 at D36 to a similar efficiency, however caspase-1 appears to be markedly more efficient at maturing pro-IL-1β compared to caspase-4 and -5 (95)). Inflammatory caspases sequentially cleave pro-IL-1β at two distinct sites, D27 which is not predicted to yield an active cytokine, and D116 which liberates the mature cytokine (30, 101, 201, 202). When compared in vitro, caspase-1 is able to cleave both sites efficiently within the nanomolar range, whereas caspase-4 and -5 efficiently cleave D27 but have a limited capacity to cleave the activating D116 site (95). The structural basis for pro-IL-18 processing by inflammatory caspases has provided mechanistic insight into how these cytokines are targeted and activated by inflammatory caspases. Processing of pro-IL-18 by inflammatory caspases has been shown to utilize both the exosite, which is located within the pro-domain of pro-IL-18, and the tetrapeptide (95, 96, 98, 101). In addition to harboring the exosite, the pro-domain of pro-IL-18 has also been shown to play autoinhibitory roles, which prevent unprocessed IL-18 signaling to the IL-18 receptor. Structural superpositions of pro-IL-18 and mature IL-18 reveal key conformational transformations which occur following caspase processing, which result in formation of the receptor binding domain of mature IL-18. Currently, there are no structures of inflammatory caspases in complex with pro-IL-1β, but it is likely that similar mechanisms are employed which regulate its activation by inflammatory caspases (203). Structural insights into pro-IL-1β processing will be paramount for understanding the molecular determinants which underpin its activation and the discrepancies in substrate processing between the inflammatory caspases. Following caspase processing, the release of matured IL-1 cytokines is promoted through the GSDMD pore. Interestingly, the pro-domains of pro-IL-18 and pro-IL-1β possess conflicting electrostatic charges which restrict the export of unprocessed cytokines (29, 39, 204, 205). Once the matured cytokines are released, they drive a plethora of pro-inflammatory signaling cascades following docking to their cognate type 1 interleukin receptors, namely IL-18R1 for IL-18, and IL-1R1 for IL-1β. Following receptor docking, pro-inflammatory responses are then primarily driven by the MyD88 axis, which activates several downstream pro-inflammatory signaling pathways via the activation of NF-κB and IL-1 receptor-associated kinases (206). For IL-18, the downstream inflammatory mediators which are activated potently induce IFNγ production within natural killer cells and CD4+ T helper one cells, exacerbating the type 1 inflammatory response (207). In the case for IL-1β, the inflammatory response is amplified by the induction of accessory pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and endothelial recruitment factors, resulting in the recruitment of immune cells to the site of inflammation (26, 207). Additionally, IL-1β functions as potent pyrogen, and its signaling triggers fevers and other physiological consequences in vivo (208, 209, 210).

Inflammatory caspase crosstalk with alternative cell-death pathways

Since their discovery, inflammatory caspase functions have been primarily associated with pro-inflammatory pyroptotic cell death. However, holistic studies on cell death mechanisms has identified extensive and complex bidirectional crosstalk between these pathways (211). One reason for this is there being significant overlap in the activation stimuli and substrate repertoire between each member of the caspase family. For example, in addition to the processing of pro-inflammatory pyroptotic mediators, direct processing of components of the apoptotic pathway by inflammatory caspases, including Bid, PARP1, BAP31, and the executioner caspases −3 and −7, have been reported (33, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218, 219). Whilst the direct processing of these substrates in vitro has been observed, the cellular contexts in which crosstalk with the apoptotic pathway occurs indicates the presence of complex back-up mechanisms, in which alternative cell-death pathways can be activated in the event pyroptosis fails to ensue (211). For example, in the absence of GSDMD, caspase-1 directly cleaves and activates Bid, caspase-3 and, -7, all of which result in engagement of the apoptotic pathway (33, 213, 217, 220). This crosstalk also extends to the NCI, with the activation of caspase-3 and -7 being linked to caspase-4 activation. However, whether there is a direct interaction between these caspases and the physiological relevance of these interactions in vivo remains elusive (101, 221). Interestingly, upon engagement of apoptotic machinery by inflammatory caspases, caspase-3 and -7 participate in a negative feedback mechanism to actively shutdown pyroptotic signaling, via cleavage of GSDMD at a distinct site D87 resulting in its inactivation (217). In support of this, caspase-7-dependent negative regulation of the pyroptotic pathway has also been reported through numerous independent mechanisms, including the cleavage of the acid sphingomyelinase ASM, mediating the repair of GSDMD pores (222, 223, 224, 225). The biological function of this negative feedback to the pyroptotic pathway is unclear, however it likely serves as an additional mechanism to protect cells in contexts where inflammatory caspases are activated, but excessive inflammation could be detrimental. Activation of back-up cell death mechanisms upon inhibition of pyroptosis is likely to be particularly important for either inflammasome-activated cells which do not express sufficient amounts of pyroptopic machinery or during the response to certain pathogens which encode effectors which target pyroptotic machinery, such as Enterovirus 71 which inactivates GSDMD during viral infection (226). In these situations, pyroptosis will be the primary mode of cell death catalyzed by inflammatory caspases, but overtime begins to trigger alternative death-pathways in the event the cell fails to die via pyroptosis.

To add to this complexity, although caspase-3 inactivates GSDMD, caspase-3 can drive pyroptosis by cleaving and activating GSDME (220, 227, 228, 229). In addition, caspase-3 can process pro-IL-18 at D76 into an alternative species which augments anti-tumor immunity by promoting the mobilization of NK cells to tumors (230). This alternative species of IL-18 both complements the function of mature IL-18 produced by the inflammatory caspases and acts as a secondary pro-inflammatory mechanism for enhancing NK cell activity. These findings enhance our understanding of the intricate roles played by each caspase in cell-death pathways, as the mode of cell-death triggered by a caspase appears to be dependent on the substrate repertoire within a cell. For example, although activation of caspase-3 typically leads to death by apoptosis, expression of GSDME may convert this phenotype to pyroptosis (213, 227, 231). Indeed, the biological relevance of caspase-3 crosstalk with the pyroptotic pathway is strengthened by its conservation in other species. For example, in birds, GSDME is also cleaved by caspase-3, however it inactivates GSDMA, which is cleaved by inflammatory caspases in the non-mammals (232).

In addition to cross-talk to the apoptotic executioner caspases −3 and −7, caspase-8 appears to have multiple overlapping roles with the inflammatory caspases, as well as playing key roles in other forms of cell death, such as necroptosis and apoptosis (233). Like the inflammatory caspases, under certain conditions, caspase-8 is able to process GSDMD, pro-IL-1β, and pro-IL-18 to mediate inflammatory cell death and cytokines secretion (234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239). Additionally, in the absence of caspase-1, caspase-8 is recruited to inflammasomes and activated in an ASC-dependent manner, resulting in the execution of apoptosis via activation caspase-3 and -7 (240, 241, 242). The inflammatory caspases have been shown to complement some of the roles played by caspase-8 in necroptosis, suggesting that they have largely overlapping substrate specificities (243). These findings suggest that caspase-8 can serve as a central caspase which can participate as back-up for the inflammatory caspases, as well as a central axis for the execution of several other cell death pathways. The key to understanding this complex crosstalk between the inflammatory caspases and alternative cell-death pathways may lie within the kinetics in which each substrate is processed by inflammatory caspases, which is ultimately dependent on the affinities for each substrate and their relative abundance in each cell type. Understanding the rate of which substrates are processed by each caspase will be essential to decipher these complexities.

#9- Although caspase-8 is classified as an apoptotic initiator, its unique substrate specificity means that it has multiple overlapping roles with the inflammatory caspases.

Other substrates of inflammatory caspases

Despite GSDMD, pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 being the best characterized substrates for inflammatory caspases, mounting evidence demonstrates the presence of other substrates, whose processing also has functional consequences in certain contexts. Notable substrates include cGAS, the p62 sequestosome, and multiple RNA-binding proteins, whose cleavage undoubtable participates in downstream cellular reprogramming events (84, 216, 244, 245, 246). For example, inactivation of cGAS by inflammatory caspases has been suggested to regulate type I interferon responses and anti-viral immunity (244). In contrast, inactivation of p62, has been proposed to fine-tune caspase-induced inflammation at the level of autophagy (245, 247), whereas inactivation of certain RNA-binding proteins could regulate cellular responses at the transcriptional level. Studies have indicated that the repertoire of cytokines processed by inflammatory caspases extend beyond IL-1β and IL-18, with IL-33, IL-37, IL-36γ, and IL-1α also being validated as caspase substrates. However, the rate in which these are processed in vitro raises questions on their physiological relevance (28, 95, 248, 249, 250, 251, 252).

Substrate profiling of inflammatory caspases using reverse proteomics has led to the identification of multiple putative caspase substrates which have uncharacterized roles during the inflammatory response (84, 216, 245, 246). However, the physiological relevance of these substrates remains to be defined as multiple putative substrates are likely to be bystander substrates whose cleavage has little to no phenotypic consequence (16). In addition, in many cases, the in vitro processing of a caspase substrate will not translate into physiologically relevant interactions in cells. The primary reason behind this is the spatial and temporal restriction of inflammatory caspase activity to the inflammasomes, limiting their access to many substrates (63, 111, 115). Thus, multi-pronged approaches which utilize both proteomics and cell biology are essential moving forward when uncovering both novel and physiologically relevant substrates downstream of the inflammatory caspases.

#10- Dysregulation of caspase-1 signaling due to gain-of-function mutations within inflammasome sensor proteins is linked to a diverse plethora of diseases, each with a broad range of symptoms (136, 253). This diversity in disease symptoms emphasizes the physiological relevance of inflammatory caspase functions beyond their roles in pyroptosis and cytokine secretion.

10 things we wish we knew about inflammatory caspases

Here, we reviewed over 30 years of research to summarize our current understanding of the human inflammatory caspases, with a focus on their biochemistry, activation, and signaling. However, when looking forward to the next 30 years, there remain numerous exciting questions requiring investigation to guide future efforts to fine-tune inflammatory caspase activity for the treatment of disease. Below, we have summarized the ten things that we wish we knew about inflammatory caspases and hope this can be used to guide future research endeavors.

#1- Caspase-5: Caspase-5 remains the most understudied inflammatory caspase, largely due to its unique species and tissular expression pattern (54). However, its tightly regulated gene expression suggests that its activity may have drastic consequences upon its dysregulation. In addition, its unique elongated CARD domain raises questions as to whether it possesses distinct activation mechanisms from caspase-4. Investigations into caspase-5 activation and its substrate repertoire are essential to understanding the exact functions of caspase-5 during disease.

#2 Structural basis for IL-1β maturation: Structural insights into IL-1β maturation by inflammatory caspases will shed light on how caspase-1 has superior processing abilities compared with other caspases, and whether this interaction is also mediated by the exosite used for GSDMD and pro-IL-18 processing.

#3- Inflammatory caspase substrate repertoire: Most of our understanding of the inflammatory caspase substrate repertoire has been conducted on caspase-1. However, our understanding of substrates which are specifically targeted by caspase-4 and -5 is limited. Recent work using photo cross-linking proteomics has begun to shed light on this and has revealed novel substrates with previously unestablished links to NCI activation (254). However, additional approaches will be required to identify novel and physiologically relevant substrates of the NCI.

#4- Mechanistic basis for NCI formation: Many questions are still unanswered regarding inflammatory caspase activation via the NCI. Currently, only biochemical data underpins the observation that the CARD domain of caspase-4 and -5 directly binds to LPS. Thus, structural insights into the nature of this interaction and the involvement of the GBPs will answer key questions regarding the structural basis for NCI formation. Additionally, whether there are other factors which facilitate caspase activation by the NCI remains unknown.

#5- Pathogen regulation of inflammatory caspase activation and signaling:

Despite much effort being made to understand host-defense mechanisms against invading pathogens, limited efforts have been made to investigate the mechanisms employed by pathogens to increase their survival. Indeed, it has been shown that some Shigella species express effector proteins which degrade GBPs to limit the recruitment and activation of caspase-4 and -5 (255, 256, 257, 258, 259). Whether other pathogens employ analogous mechanisms to prevent inflammatory caspase activation is subject to investigations.

#6- Cell-type specific inflammatory caspase functions: Ultimately, the function performed by inflammatory caspases depends on the substrates available for cleavage within a cell. Investigation into how the substrate repertoire varies between cell types, and how this drives phenotypic variation upon caspase activation is crucial to understanding the role played by inflammatory caspases in different cellular contexts.

#7- Evolution of inflammatory caspase signaling: Recent studies highlighted the functions in inflammatory caspases beyond humans and mice. Understanding converging signaling mechanisms across evolution will highlight conserved and divergent functions of these proteases (54, 232, 260, 261, 262, 263). Additionally, these insights will help clarify the evolutionary history of the human inflammatory caspase family, and help explain observations such as the truncation of caspase-12, which appear to have undergone positive selection (42).

#8 Pharmacological inhibition of the exosite interface: The exosite interface represents a novel target for selective inhibition of inflammatory caspases by pharmacological compounds. How therapeutics which target this interface will compare to the current caspase inhibitors available is an exciting question which will undoubtedly be answered in current caspase drug-discovery efforts.

#9 Endogenous regulators of caspase activity: The presence of regulatory CARD domain-only proteins within the human genome have been of significant interest in understanding the endogenous mechanisms in place to prevent dysregulation of caspase activity (156, 264). However, more recently, other mechanisms which regulate inflammatory caspase activity downstream of the inflammasomes have been shown (222, 223, 265, 266). Understanding the underpinning mechanisms of each of these endogenous regulatory mechanisms, how they vary between cell populations, and whether there is the crosstalk between these mechanisms will be critical to develop novel caspase-centric therapies.

#10 Inflammatory caspase polymorphisms: Mutations within inflammatory caspase promoter regions and coding sequences leading to dysregulation of caspase activity have been previously linked to disease (118, 267). Whilst some of these mutations have been characterized, the prominence and biological implications of other polymorphisms within the human population that have the capacity to drive disease have not been explored.

Data availability

All data presented are contained within the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowlegments

We wish to thank members of the Boucher lab for helpful discussions. The work performed in the Boucher lab is supported by a New Investigator Award Grant from the Medical Research Council (MR/Z504221/1), and a project grant the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Council (BB/Y0097034/1) from UKRI. Sebastian Grant is supported by a York Graduate School Scholarship and YCEDE.

Author contributions

S. G. and D. B. writing–review & editing; S. G. and D. B. writing–original draft; S. G. conceptualization. D. B. supervision; D. B. conceptualization.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Clare E. Bryant

References

- 1.Alnemri E.S., Livingston D.J., Nicholson D.W., Salvesen G., Thornberry N.A., Wong W.W., et al. Human ICE/CED-3 protease nomenclature. Cell. 1996;87:171. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornberry N.A., Bull H.G., Calaycay J.R., Chapman K.T., Howard A.D., Kostura M.J., et al. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1 beta processing in monocytes. Nature. 1992;356:768–774. doi: 10.1038/356768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerretti D.P., Kozlosky C.J., Mosley B., Nelson N., Van Ness K., Greenstreet T.A., et al. Molecular cloning of the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science. 1992;256:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1373520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan J., Shaham S., Ledoux S., Ellis H.M., Horvitz H.R. The C. elegans cell death gene ced-3 encodes a protein similar to mammalian interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme. Cell. 1993;75:641–652. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horvitz H.R. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1701s–1706s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamens J., Paskind M., Hugunin M., Talanian R.V., Allen H., Banach D., et al. Identification and characterization of ICH-2, a novel member of the Interleukin-1β-converting enzyme family of cysteine proteases (∗) J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:15250–15256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faucheu C., Blanchet A.M., Collard-Dutilleul V., Lalanne J.L., Diu-Hercend A. Identification of a cysteine protease closely related to interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;236:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.t01-1-00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faucheu C., Diu A., Chan A.W., Blanchet A.M., Miossec C., Hervé F., et al. A novel human protease similar to the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme induces apoptosis in transfected cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:1914–1922. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orth K., Chinnaiyan A.M., Garg M., Froelich C.J., Dixit V.M. The CED-3/ICE-like protease Mch2 is activated during apoptosis and cleaves the death substrate lamin A. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16443–16446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes-Alnemri T., Armstrong R.C., Krebs J., Srinivasula S.M., Wang L., Bullrich F., et al. In vitro activation of CPP32 and Mch3 by Mch4, a novel human apoptotic cysteine protease containing two FADD-like domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:7464–7469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandes-Alnemri T., Takahashi A., Armstrong R., Krebs J., Fritz L., Tomaselli K.J., et al. Mch3, a novel human apoptotic cysteine protease highly related to CPP32. Cancer Res. 1995;55:6045–6052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholson D.W., Ali A., Thornberry N.A., Vaillancourt J.P., Ding C.K., Gallant M., et al. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature. 1995;376:37–43. doi: 10.1038/376037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chinnaiyan A.M., O’Rourke K., Tewari M., Dixit V.M. FADD, a novel death domain-containing protein, interacts with the death domain of Fas and initiates apoptosis. Cell. 1995;81:505–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lippke J.A., Gu Y., Sarnecki C., Caron P.R., Su M.S. Identification and characterization of CPP32/Mch2 homolog 1, a novel cysteine protease similar to CPP32. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:1825–1828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotonda J., Nicholson D.W., Fazil K.M., Gallant M., Gareau Y., Labelle M., et al. The three-dimensional structure of apopain/CPP32, a key mediator of apoptosis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:619–625. doi: 10.1038/nsb0796-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Julien O., Wells J.A. Caspases and their substrates. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1380–1389. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr J.F., Wyllie A.H., Currie A.R. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hengartner M.O. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen G.M. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem. J. 1997;326:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boatright K.M., Salvesen G.S. Mechanisms of caspase activation. Curr Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford E.D., Seaman J.E., Agard N., Hsu G.W., Julien O., Mahrus S., et al. The DegraBase: a database of proteolysis in healthy and apoptotic human cells. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:813–824. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.024372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boatright K.M., Renatus M., Scott F.L., Sperandio S., Shin H., Pedersen I.M., et al. A unified model for apical caspase activation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:529–541. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riedl S.J., Salvesen G.S. The apoptosome: signalling platform of cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:405–413. doi: 10.1038/nrm2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashkenazi A., Dixit V.M. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinon F., Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes: master switches of inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:10–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sims J., Smith D.E. The IL-1 family: regulators of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nri2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantovani A., Dinarello C.A., Molgora M., Garlanda C. Interleukin-1 and related cytokines in the regulation of inflammation and immunity. Immunity. 2019;50:778–795. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan A.H., Schroder K. Inflammasome signaling and regulation of interleukin-1 family cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217 doi: 10.1084/jem.20190314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monteleone M., Stanley A.C., Chen K.W., Brown D.L., Bezbradica J.S., von Pein J.B., et al. Interleukin-1β maturation triggers its relocation to the plasma membrane for Gasdermin-D-Dependent and -Independent secretion. Cell Rep. 2018;24:1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan A.H., Burgener S.S., Vezyrgiannis K., Wang X., Acklam J., Von Pein J.B., et al. Caspase-4 dimerisation and D289 auto-processing elicit an interleukin-1β-converting enzyme. Life Sci. Alliance. 2023;6 doi: 10.26508/lsa.202301908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cookson B.T., Brennan M.A. Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:113–114. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01936-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi J., Zhao Y., Wang K., Shi X., Wang Y., Huang H., et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660–665. doi: 10.1038/nature15514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He W.-T., Wan H., Hu L., Chen P., Wang X., Huang Z., et al. Gasdermin D is an executor of pyroptosis and required for interleukin-1β secretion. Cell Res. 2015;25:1285–1298. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding J., Wang K., Liu W., She Y., Sun Q., Shi J., et al. Erratum: Pore-forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature. 2016;540:150. doi: 10.1038/nature20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X., Zhang Z., Ruan J., Pan Y., Magupalli V.G., Wu H., et al. Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature. 2016;535:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature18629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X., He W.-T., Hu L., Li J., Fang Y., Wang X., et al. Pyroptosis is driven by non-selective gasdermin-D pore and its morphology is different from MLKL channel-mediated necroptosis. Cell Res. 2016;26:1007–1020. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russo H.M., Rathkey J., Boyd-Tressler A., Katsnelson M.A., Abbott D.W., Dubyak G.R. Active Caspase-1 induces plasma membrane pores that precede pyroptotic lysis and are blocked by lanthanides. J. Immunol. 2016;197:1353–1367. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Degen M., Santos J.C., Pluhackova K., Cebrero G., Ramos S., Jankevicius G., et al. Structural basis of NINJ1-mediated plasma membrane rupture in cell death. Nature. 2023;618:1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05991-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia S., Zhang Z., Magupalli V.G., Pablo J.L., Dong Y., Vora S.M., et al. Gasdermin D pore structure reveals preferential release of mature interleukin-1. Nature. 2021;593:607–611. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03478-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ball D.P., Taabazuing C.Y., Griswold A.R., Orth E.L., Rao S.D., Kotliar I.B., et al. Caspase-1 interdomain linker cleavage is required for pyroptosis. Life Sci Alliance. 2020;3 doi: 10.26508/lsa.202000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott J.M., Rouge L., Wiesmann C., Scheer J.M. Crystal structure of procaspase-1 zymogen domain reveals insight into inflammatory caspase autoactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6546–6553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806121200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rocher C., Faucheu C., Blanchet A.M., Claudon M., Hervé F., Durand L., et al. Identification of five new genes, closely related to the interleukin-1beta converting enzyme gene, that do not encode functional proteases. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;246:394–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xue Y., Daly A., Yngvadottir B., Liu M., Coop G., Kim Y., et al. Spread of an inactive form of caspase-12 in humans is due to recent positive selection. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;78:659–670. doi: 10.1086/503116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vande W.L., Jiménez Fernández D., Demon D., Van Laethem N., Van Hauwermeiren F., Van Gorp H., et al. Does caspase-12 suppress inflammasome activation? Nature. 2016;534:E1–E4. doi: 10.1038/nature17649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischer H., Koenig U., Eckhart L., Tschachler E. Human caspase 12 has acquired deleterious mutations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;293:722–726. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Identification of Five New Genes, Closely Related to the Interleukin-1β Converting Enzyme Gene, that do not Encode Functional Proteases. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Mikolajczyk J., Scott F.L., Krajewski S., Sutherlin D.P., Salvesen G.S. Activation and substrate specificity of caspase-14. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10560–10569. doi: 10.1021/bi0498048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Denecker G., Ovaere P., Vandenabeele P., Declercq W. Caspase-14 reveals its secrets. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:451–458. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Markiewicz A., Sigorski D., Markiewicz M., Owczarczyk-Saczonek A., Placek W. Caspase-14-from biomolecular basics to clinical approach. A review of available data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:5575. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lamkanfi M., Kalai M., Vandenabeele P. Caspase-12: an overview. Cell Death Differ. 2004 Apr;11:365–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bouchier-Hayes L., Green D.R. Caspase-2: the orphan caspase. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:51–57. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fuentes-Prior P., Salvesen G.S. The protein structures that shape caspase activity, specificity, activation and inhibition. Biochem. J. 2004;384:201–232. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glover H.L., Schreiner A., Dewson G., Tait S.W.G. Mitochondria and cell death. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024;26:1434–1446. doi: 10.1038/s41556-024-01429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holland M., Rutkowski R., C Levin T. Evolutionary dynamics of proinflammatory caspases in primates and rodents. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024;41 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msae220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saleh M., Vaillancourt J.P., Graham R.K., Huyck M., Srinivasula S.M., Alnemri E.S., et al. Differential modulation of endotoxin responsiveness by human caspase-12 polymorphisms. Nature. 2004;429:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nature02451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rawlings N.D., Barrett A.J. Evolutionary families of peptidases. Biochem. J. 1993;290:205–218. doi: 10.1042/bj2900205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thornberry N.A. The caspase family of cysteine proteases. Br. Med. Bull. 1997;53:478–490. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seaman J.E., Julien O., Lee P.S., Rettenmaier T.J., Thomsen N.D., Wells J.A. Cacidases: caspases can cleave after aspartate, glutamate and phosphoserine residues. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1717–1726. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson K.P., Black J.A., Thomson J.A., Kim E.E., Griffith J.P., Navia M.A., et al. Structure and mechanism of interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Nature. 1994;370:270–275. doi: 10.1038/370270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilmouth R.C., Edman K., Neutze R., Wright P.A., Clifton I.J., Schneider T.R., et al. X-ray snapshots of serine protease catalysis reveal a tetrahedral intermediate. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:689–694. doi: 10.1038/90401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clark A.C. Caspase allostery and conformational selection. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:6666–6706. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aravind L., Koonin E.V. Classification of the caspase-hemoglobinase fold: detection of new families and implications for the origin of the eukaryotic separins. Proteins. 2002;46:355–367. doi: 10.1002/prot.10060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boucher D., Monteleone M., Coll R.C., Chen K.W., Ross C.M., Teo J.L., et al. Caspase-1 self-cleavage is an intrinsic mechanism to terminate inflammasome activity. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:827–840. doi: 10.1084/jem.20172222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riedl S.J., Fuentes-Prior P., Renatus M., Kairies N., Krapp S., Huber R., et al. Structural basis for the activation of human procaspase-7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:14790–14795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221580098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Datta D., McClendon C.L., Jacobson M.P., Wells J.A. Substrate and inhibitor-induced dimerization and cooperativity in caspase-1 but not caspase-3. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:9971–9981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.426460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Uren A.G., O’Rourke K., Aravind L.A., Pisabarro M.T., Seshagiri S., Koonin E.V., et al. Identification of paracaspases and metacaspases: two ancient families of caspase-like proteins, one of which plays a key role in MALT lymphoma. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:961–967. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen J.M., Rawlings N.D., Stevens R.A., Barrett A.J. Identification of the active site of legumain links it to caspases, clostripain and gingipains in a new clan of cysteine endopeptidases. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:361–365. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walker N.P., Talanian R.V., Brady K.D., Dang L.C., Bump N.J., Ferenz C.R., et al. Crystal structure of the cysteine protease interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme: a (p20/p10)2 homodimer. Cell. 1994;78:343–352. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keller N., Mares J., Zerbe O., Grütter M.G. Structural and biochemical studies on procaspase-8: new insights on initiator caspase activation. Structure. 2009;17:438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salvesen G.S., Dixit V.M. Caspase activation: the induced-proximity model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:10964–10967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]