Abstract

Background

An important challenge in flow cytometry (FCM) data analysis is making comparisons of corresponding cell populations across multiple FCM samples. An interesting solution is creating a statistical mixture model for multiple samples simultaneously, as such a multi-sample model can characterize a heterogeneous set of samples, and facilitates direct comparison of cell populations across the data samples. The multi-sample approach to statistical mixture modeling has been explored in a number of reports, mostly within a Bayesian framework and with high computational complexity. Although these approaches are effective, they are also computationally demanding, and therefore do not relate well to the requirement of scalability, which is essential in the multi-sample setting. This limits their utility in the analysis of large sets of large FCM samples.

Results

We show that basic Gaussian mixture models can be extended to large data sets consisting of multiple samples, using a computationally efficient implementation of the expectation-maximization algorithm. We show that the multi-sample Gaussian mixture model (MSGMM) is competitive with other models, in both rare cell detection and sample classification accuracy. This allows us to further explore the utility of MSGMMs in the analysis of heterogeneous sets of samples. We demonstrate how simple heuristics on MSGMM model output can directly reveal structural patterns in a collection of FCM samples.

Conclusions

We recover the efficiency and utility of the basic MSGMM which underlies more complex and non-parametric Bayesian hierarchical mixture models. The possibility of fitting GMMs to large sets of FCM samples provides opportunities for the discovery of associations between sample composition and sample meta-data such as treatment responses and clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12859-025-06285-z.

Keywords: Gaussian mixture models, EM algorithm, Flow cytometry, Large-scale data, Clustering, Classification

Background

Flow cytometry (FCM) is a single-cell analysis technique that allows high-throughput measurements of multiple biological markers on large numbers of single cells. Due to technological advancements, an increasing number of cells and markers can be assessed, leading to data sets of up-to 50 of parameters on millions of cells per sample [1]. The increasing complexity of FCM presents a challenge to the objectivity and reproducibility of conventional human expert based FCM data analyses. To improve the effectiveness and objectivity of FCM data analysis, a range of automated analysis techniques have been explored in the literature (see [2–4] for overviews).

In the landscape of computational methods, statistical mixture models stand out due to their suitability to the specific problem of analysing FCM data. Statistical mixture models provide a direct probabilistic description of the cell distributions in the observation space and allow graphical interpretation in a manner akin to manual analysis. As a result, statistical mixture models are a popular method of choice in efforts to automate the analysis of FCM data.

Applications of FCM data analysis often involve multiple data of different samples. An important aspect of many applications of FCM data analysis is making comparisons of corresponding cell populations across multiple samples. Cross-sample alignment of cell clusters is a necessary step to classify samples from one cohort in diseased and healthy or to track changes in the composition of cell populations in samples at different time points [5–7]. Several approaches have been taken to the solution of this problem [8]. The analysis of a cohort of samples can be decomposed in two problems. Firstly, a model has to be created for a class of samples, identifying ‘meta-clusters’ that represent underlying commonalities. Secondly, clusters have to be aligned or matched across different samples to measure their proportional presence (or absence). Different methods that have been proposed target either one of those problems, or solve them both at once.

A first proposed solution is to pool data from multiple samples [9, 10]. This solution is model-independent and has been used in combination with a range of clustering methods. In a subsequent step, samples can be characterized by recovering proportional cell contributions for each cluster from individual samples. However, models fitted to pooled data have a limited ability to describe sample-specific features, as they describe an ‘averaged’ version of the data [11]. Moreover, down-sampling before data pooling will further decrease model sensitivity for rare cell populations.

A second approach is to fit models to individual samples and then to match model components across the samples based on a distance measure or matching algorithm [6, 7, 12]. Although this method can be applied to any clustering method, it has been mostly used in the context of statistical mixture models. However, as a model is fit to each sample separately, no information is shared, and rare cell populations do not benefit from occurring in multiple samples. Additionally, this approach involves ad hoc parameter choices regarding the distance metric which distinguishes random variation (e.g. batch effects) from real biological differences.

A third approach consists of fitting statistical mixture models to multiple samples simultaneously, i.e. creating a joint model. This approach commonly consists of keeping model component parameters (e.g. mean and covariance) fixed across samples, while allowing mixing parameters (or proportional weights) to vary [8, 11, 13, 14]. Joint modelling of multiple samples avoids the limitations inherent to the other approaches. First of all, models in this category are able to describe with greater accuracy a heterogeneous set of samples. By letting mixing parameters converge to zero, multi-sample models can capture the absence of cell clusters in specific samples. At the same time, a multi-sample approach benefits from sharing information across multiple samples. Cell populations with low frequencies acquire mass by aggregating cells in multiple samples, facilitating their detection. Together, these two aspects of multi-sample models enhance their ability to identify rare cell populations. In addition, multi-sample models greatly facilitate direct comparison of cell populations across data samples, as cell clusters are consistently labeled.

The advantages of multi-sample models are especially useful for analysing heterogeneous sample sets, where cell populations in individual samples are varying subsets of a larger set of possibilities. Such heterogeneity of phenotypes is only revealed by considering a sufficiently large number of samples. Thus, the utility of a multi-sample model increases with its ability to be applied to larger collections of samples. A multi-sample statistical mixture model approach is well suited to describe a composition of samples containing a negative control group. By associating the prevalence/absence of specific cell clusters with disease/control samples, such a model can be used for downstream sample classification tasks. Multi-sample mixture models are ideal candidates to serve as complete data models, or class ‘templates’, which can summarize a whole class of samples [6, 10]. Complete data models can be used to find associations between the proportional composition of the sample and different treatment responses, time points, and clinical outcomes.

The multi-sample or joint approach to statistical mixture modeling has been explored in a number of reports which have elucidated its benefits. The approach was pioneered in the work by Cron et al. (2013) [11], who introduced hierarchical Gaussian mixture models within a Bayesian optimization framework. Several variations on the multi-sample approach have subsequently been proposed, mostly within a Bayesian framework [8, 13, 15]. The Bayesian approach provides a natural framework for hierarchical modeling [16]. However, the estimation of hierarchical Bayesian mixture models requires sophisticated Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithms which are computationally demanding [15]. This aspect of Bayesian models conflicts with the crucial requirement of scalability, inherent to the multi-sample approach. An important exception to the Bayesian approaches is the work of McLachlan and co-workers (2014; 2016) [7, 14], who have shown that maximum likelihood estimation provides a useful alternative for joint modeling. Maximum likelihood estimation is computationally less expensive, which considerably increases the possibilities for practical application of multi-sample models.

Here, we build upon the original work by Cron et al. (2013), who proposed the hierarchical Dirichlet process Gaussian mixture model (HDPGMM) [11]. We focus on a similar hierarchical Gaussian mixture model (GMM). However, we depart from both the Bayesian optimization framework and the Dirichlet process formulation. We show how GMMs can be efficiently fitted to multiple samples within the maximum likelihood-based optimization framework. More specifically, we show how a combination of simple tweaks in the implementation of the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm gives a remarkable improvement in runtime, allowing for scaling the application of the multi-sample GMM (MSGMM) to both much larger samples and larger collections of samples. This allows us to further explore the utility of MSGMMs in the analysis of heterogeneous sets of samples. Note that these multi-level models are referred to as ‘hierarchical’ in the Bayesian context [16]. To avoid confusion, we refer to our model as a MSGMM.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. “Methods” we describe the MSGMM, and describe our efficient implementation of the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm for parameter estimation. We propose heuristic methods for the analysis of MSGMM model output, which can directly reveal important variation in the multi-sample structure of the data. Subsequently, we apply MSGMMs to several data sets and we show the computational efficiency in comparison to the HDPGMM. To demonstrate the utility of the MSGMM on larger sample sets, we fit the MSGMM to a previously published FCM data set of 65 acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) samples [12]. Using the likelihood ratio test, we show that the MSGMM produces more accurate models in comparison to regular GMMs fitted to pooled data. We test the performance of the MSGMM in sample classification on the FlowCAP II challenge acute myeloid leukemia (AML) data set [17]. AML is characterized by a multitude of molecular abnormalities, and cell populations may be present in some patients while being absent in others. As a demonstration of the effectiveness of MSGMMs in describing heterogeneous sample sets, we fit models to a large collection of AML bone marrow samples, combined with a healthy control group. We show how the output of the MSGMM reveals essential structure in the sample set, and how this can be used for the classification of samples. Finally, in Sect. “Discussion” we conclude with a discussion of our findings.

Methods

Model

We consider p-dimensional observations (cells)  , with

, with  from

from  independent flow cytometry data samples. The probability density function for the cells in each sample is assumed to be

independent flow cytometry data samples. The probability density function for the cells in each sample is assumed to be

|

1 |

where  is the complete set of parameters in the model, K is the number of components,

is the complete set of parameters in the model, K is the number of components,  are the mixing proportions, and

are the mixing proportions, and  and

and  are the p-dimensional mean and

are the p-dimensional mean and  covariance matrix of the k-th mixture component. Note that the mixing proportions

covariance matrix of the k-th mixture component. Note that the mixing proportions  are double indexed and that the model estimates a sample-specific vector of mixing proportions for each sample s. Thus, the model generates an

are double indexed and that the model estimates a sample-specific vector of mixing proportions for each sample s. Thus, the model generates an  matrix

matrix  of mixing proportions, of which each row sums to one. Note that the average over each column in this matrix is just the mixing proportion

of mixing proportions, of which each row sums to one. Note that the average over each column in this matrix is just the mixing proportion  for the pooled data, i.e.

for the pooled data, i.e.

|

2 |

The matrix of mixing proportions (or ‘ -matrix’) plays a central role in this paper.

-matrix’) plays a central role in this paper.

We estimate the parameters of the Gaussian mixture model (Eq. 1) using the maximum likelihood procedure. The log-likelihood is

|

3 |

In Fig. 1 we provide an overview of the steps in the optimization procedure. The labeled steps are referenced in the corresponding subsections of the Methods section, where they are described in detail.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the steps in the optimization procedure and model output analysis. The labeled steps are referenced in the corresponding subsections of the Methods section, where they are described in detail

EM algorithm

The log-likelihood is maximized using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm across all samples simultaneously. The EM algorithm iterates between two steps [18].

E-step

In the E-step (step b in Fig. 1) we calculate the posterior probabilities (‘responsibilities’ [19]) of the mixture component memberships

|

4 |

Note that the E-step iterates over all  data points (and K multivariates). However, to estimate sample-specific mixing proportions

data points (and K multivariates). However, to estimate sample-specific mixing proportions  we introduce ‘intermediate M-steps’ for

we introduce ‘intermediate M-steps’ for  . As part of the E-step, we update mixing proportions after each sample s, i.e.

. As part of the E-step, we update mixing proportions after each sample s, i.e.

|

5 |

The  are used to evaluate sample-specific posterior probabilities

are used to evaluate sample-specific posterior probabilities  in the next iteration E-step. This tweak preserves the multi-sample structure of the data in the maximum likelihood estimate and defines the multi-sample version of the GMM.

in the next iteration E-step. This tweak preserves the multi-sample structure of the data in the maximum likelihood estimate and defines the multi-sample version of the GMM.

M-step

In the M-step (step c in Fig. 1) we update the estimates for the model model parameters,

|

6 |

|

7 |

|

8 |

where we first obtain the sum  (Eq. 6) used to estimate the mixture component parameters

(Eq. 6) used to estimate the mixture component parameters  and

and  (Eqs. 7 and 8). Note that the M-step allows components to be excluded from the update and to keep them fixed. These components could represent known (or previously estimated) clusters from say, literature, a pilot study, or a healthy reference population. Hereto we partition the cluster index as

(Eqs. 7 and 8). Note that the M-step allows components to be excluded from the update and to keep them fixed. These components could represent known (or previously estimated) clusters from say, literature, a pilot study, or a healthy reference population. Hereto we partition the cluster index as  where the first

where the first  clusters are known. Consequently, the likelihood is not maximized with respect to

clusters are known. Consequently, the likelihood is not maximized with respect to  .

.

Memory efficiency

A memory efficient implementation of the EM algorithm is based on the observation that the formulation of the M-step above (Eqs. 6–8) does not require the storage of all  posterior probabilities in computer memory. The sufficient statistics required for estimating the parameters in the M-step are cumulative values which can be calculated and summed while iterating the data and evaluating the responsibilities

posterior probabilities in computer memory. The sufficient statistics required for estimating the parameters in the M-step are cumulative values which can be calculated and summed while iterating the data and evaluating the responsibilities  in the E-step (Eq. 4). We introduce summary statistics, or accumulators [20], which are initialized as

in the E-step (Eq. 4). We introduce summary statistics, or accumulators [20], which are initialized as  , and updated by iterating all data points (i, s):

, and updated by iterating all data points (i, s):

|

9 |

|

10 |

|

11 |

The final values of the accumulators, after iterating over all data points, are used to update parameter estimates in the M-step (Eqs. 6–8). Avoiding storage of the full data array of posterior probabilities in computer memory allows the algorithm to be applied to arbitrarily large databases, where the only constraint is time.

Regularization

Due to groups of aligned cells with zero variance in one or more dimensions, maximum likelihood estimation of GMMs may converge to solutions in which Gaussian components have singular covariance matrices [21]. To avoid this problem, after each M-step, we apply the regularization (step d in Fig. 1),

|

12 |

where  is the average of the diagonal entries of

is the average of the diagonal entries of  ,

,  , and

, and  is the identity matrix. This method ensures that estimated covariance matrices are well-conditioned and invertible, and avoids overfitting [22]. In our applications we use

is the identity matrix. This method ensures that estimated covariance matrices are well-conditioned and invertible, and avoids overfitting [22]. In our applications we use  .

.

Termination

The stopping criterion for the EM algorithm is based on the relative change in the sequence of log-likelihood values (Eq. 3) [21]. We use

|

13 |

where the convergence tolerance  is a small number.

is a small number.

Initialization

Before starting the EM algorithm we initialize the means  using the K-means clustering algorithm on a random subsample of data points (step a in Fig. 1). For example, to initialize a model on hundreds of FCM files, we first randomly select a subset of 50 FCM files. We then create a subsample of 500,000 cells by randomly selecting 10,000 cells from each FCM file in the subset and apply the K-means algorithm on this subsample. We initialize the covariance matrices as diagonal matrices

using the K-means clustering algorithm on a random subsample of data points (step a in Fig. 1). For example, to initialize a model on hundreds of FCM files, we first randomly select a subset of 50 FCM files. We then create a subsample of 500,000 cells by randomly selecting 10,000 cells from each FCM file in the subset and apply the K-means algorithm on this subsample. We initialize the covariance matrices as diagonal matrices  where

where  corresponds to a fraction of the feature space domain size (say 1/10). We initialize the mixing proportions as 1/K.

corresponds to a fraction of the feature space domain size (say 1/10). We initialize the mixing proportions as 1/K.

Model selection

When applying finite statistical mixture models, the number of clusters K has to be specified in advance. An effective strategy is to set K higher than the expected number of distinct cell populations (based on background knowledge), and thus perform an over-clustering. This ensures that all cell populations are modeled by separate cluster components. A necessary condition is that modeling cell clusters with multiple components is not detrimental to the performance of the model in downstream cell identification and classification tasks. In this research, we adhere to this approach and consider estimation of the correct number of distinct cell populations of secondary importance. See Sect. “Discussion” for further discussion of this issue.

Matrix of mixing proportions

The MSGMM generates an  matrix, the

matrix, the  -matrix, in which each row is the sample-specific vector of estimated mixing proportions

-matrix, in which each row is the sample-specific vector of estimated mixing proportions  for sample s. Mixing proportions converge to zero for samples in which associated cell types are absent. Any structure in the composition of the samples used to train the GMM should be reflected in the

for sample s. Mixing proportions converge to zero for samples in which associated cell types are absent. Any structure in the composition of the samples used to train the GMM should be reflected in the  -matrix. For example, if the data set consists of samples with leukemic cells and samples without leukemic cells (i.e. a control group), then the

-matrix. For example, if the data set consists of samples with leukemic cells and samples without leukemic cells (i.e. a control group), then the  -matrix should echo this distinction by showing a subset of mixing proportions with higher values only in the leukemia samples, and values converging to zero in the healthy samples. This structure can be visualized in a heat map of a hierarchical clustering of the

-matrix should echo this distinction by showing a subset of mixing proportions with higher values only in the leukemia samples, and values converging to zero in the healthy samples. This structure can be visualized in a heat map of a hierarchical clustering of the  -matrix (step e in Fig. 1).

-matrix (step e in Fig. 1).

To find cell clusters associated with sample labels (e.g. disease/healthy), the  -matrix can be analyzed using simple heuristics. For example, if the model is trained on two groups of samples

-matrix can be analyzed using simple heuristics. For example, if the model is trained on two groups of samples  , where

, where  are samples of patients with leukemia, and

are samples of patients with leukemia, and  are samples of healthy patients, candidate clusters for representing leukemia can be derived directly from the

are samples of healthy patients, candidate clusters for representing leukemia can be derived directly from the  -matrix. We find the subset

-matrix. We find the subset  of mixture components associated with leukemia using

of mixture components associated with leukemia using

|

where  is a threshold parameter. In other words, we find mixture components that are strongly expressed only in

is a threshold parameter. In other words, we find mixture components that are strongly expressed only in  (but not in

(but not in  ). Alternatively, we look for mixture components k for which the ratio between the maximum expression level in the subgroups

). Alternatively, we look for mixture components k for which the ratio between the maximum expression level in the subgroups  and

and  exceeds a threshold value, i.e.

exceeds a threshold value, i.e.

|

14 |

where  is a threshold parameter. The ratio in Eq. 14 produces an ordering of the mixing components according to their likelihood of representing a population associated with

is a threshold parameter. The ratio in Eq. 14 produces an ordering of the mixing components according to their likelihood of representing a population associated with  .

.

The  -matrix can also be used to translate the analysis of new, unseen FCM samples to a supervised classification problem. If we store sample labels (e.g. disease/healthy) in a response vector, we can train a machine learning classifier on vectors of sample-specific mixing proportions (i.e. rows in the

-matrix can also be used to translate the analysis of new, unseen FCM samples to a supervised classification problem. If we store sample labels (e.g. disease/healthy) in a response vector, we can train a machine learning classifier on vectors of sample-specific mixing proportions (i.e. rows in the  -matrix). To classify an unseen FCM sample, we use the fitted MSGMM to ‘soft cluster’ the sample (step f in Fig. 1), which corresponds to running an E-step and generating a matrix of posterior probabilities (responsibilities)

-matrix). To classify an unseen FCM sample, we use the fitted MSGMM to ‘soft cluster’ the sample (step f in Fig. 1), which corresponds to running an E-step and generating a matrix of posterior probabilities (responsibilities)  (see Eq. 4). Note that, to compute the responsibilities we have to replace the sample-specific mixing proportions

(see Eq. 4). Note that, to compute the responsibilities we have to replace the sample-specific mixing proportions  in Eq. 4 by an averaged

in Eq. 4 by an averaged  , using Eq. 2. We assign observations

, using Eq. 2. We assign observations  (cells) to the cluster k which maximizes the posterior probability (i.e. the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate). We derive cluster proportions from the clustered sample, by counting cluster memberships and normalizing by the sample size

(cells) to the cluster k which maximizes the posterior probability (i.e. the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate). We derive cluster proportions from the clustered sample, by counting cluster memberships and normalizing by the sample size  . The normalized cluster proportions can be used as input vector for the trained classifier to predict a new sample label.

. The normalized cluster proportions can be used as input vector for the trained classifier to predict a new sample label.

Comparison with regular GMM

The multi-sample GMM is a generalization of the regular GMM, in the sense that if we would set  for all s in the former, we obtain the latter. This nested relationship facilitates the conduction of a likelihood ratio test to assess whether the multi-sample GMM is a better description of the data than the regular GMM. In particular, we test

for all s in the former, we obtain the latter. This nested relationship facilitates the conduction of a likelihood ratio test to assess whether the multi-sample GMM is a better description of the data than the regular GMM. In particular, we test  for all s vs.

for all s vs.  for at least one s. The evidence against

for at least one s. The evidence against  is summarized in the likelihood ratio test statistic:

is summarized in the likelihood ratio test statistic:

|

the difference between the log-likelihoods of the two models. The likelihood ratio test statistic is known to follow (asymptotically) a  distribution with

distribution with  degrees of freedom. If the likelihood ratio test statistic exceeds the

degrees of freedom. If the likelihood ratio test statistic exceeds the  quantile of this distribution, the null hypothesis is rejected and the multi-sample GMM is to be preferred.

quantile of this distribution, the null hypothesis is rejected and the multi-sample GMM is to be preferred.

Implementation

The MSGMM is implemented in R, with extensions in C++ code using the R package Rcpp [23]. MSGMM also takes advantage of the open-source C++ linear algebra library ‘Armadillo’ via the R package RcppArmadillo [24]. Loading data samples, running the EM algorithm loop, and storing results, are done in standard R scripts. Only the computationally expensive E-step (Eq. 4) is outsourced to C++/Armadillo. For numerical stability and computational efficiency (of the E-step function) we have taken cues from both [20] and [25]. The software is freely available from https://github.com/AUMC-HEMA/MSGMM.

Results

Experiment 1: comparison with HDPGMM

The MSGMM implements a similar hierarchical mixture model as HDPGMM but departs from the Bayesian optimization framework. We optimize the model using a computationally efficient implementation of the EM algorithm. Here we demonstrate the gains in computational time, without loss in accuracy. The open-source Python code of HDPGMM is deprecated and complicated to update. Therefore, a direct comparison of the MSGMM implementation and the HDPGMM is out of scope for this paper. Note that the improvement in runtime is overwhelming, which makes a direct comparison not critical. We provide a comparison between runtimes of MSGMM and ASPIRE, which is a related but more complex model [13], in Additional file 1. Here, we apply the MSGMM to the data used in the HDPGMM paper and compare to the reported run times (see [11]). We apply the model to the 6 samples with a specific and rare T-cell subset which are used by Cron et al. to demonstrate the utility of HDPGMM. These 5-dimensional blood samples of each 50,000 events contain spiked-in T cells in extremely low proportions of 0%, 0.013125%, 0.02625%, 0.0525%, 0.105%, and 0.21%. There is a small background contribution already present in the unspiked samples, which is estimated to be 0.0154%. Similar to Cron et al. we fit 10 MSGMMs with  to the 6 samples. In Fig. 2(a) we show a bivariate plot of the maximum spike-in-proportion sample (0.2254%), clustered using one of 10 fitted MSGMMs, and show the estimated frequency. The whole range of spiked-in proportions is well reproduced by our models. In Fig. 2(b) we compare estimated frequencies (blue circles) with true frequencies (red crosses) of antigen-specific cells. These figures are to be compared with Figs. 3 and 7 in Cron et al. (2013) [11]. We see that we achieve comparable results and that there is no loss in accuracy when employing the model in a different statistical optimization framework. However, we note that fitting our models takes

to the 6 samples. In Fig. 2(a) we show a bivariate plot of the maximum spike-in-proportion sample (0.2254%), clustered using one of 10 fitted MSGMMs, and show the estimated frequency. The whole range of spiked-in proportions is well reproduced by our models. In Fig. 2(b) we compare estimated frequencies (blue circles) with true frequencies (red crosses) of antigen-specific cells. These figures are to be compared with Figs. 3 and 7 in Cron et al. (2013) [11]. We see that we achieve comparable results and that there is no loss in accuracy when employing the model in a different statistical optimization framework. However, we note that fitting our models takes  minutes on average (on CPUs) (see Table 1 for runtime specifications). This is a drastic reduction in computation time compared to the nearly 6 h on GPU reported by Cron et al. (2013). We acknowledge that GPU performance has increased over the years, but it is unlikely to significantly diminish the difference in runtimes. Moreover, the estimation of GMMs using the EM algorithm can be made faster using parallelization [20], and can also be implemented on GPUs (e.g. see [26]).

minutes on average (on CPUs) (see Table 1 for runtime specifications). This is a drastic reduction in computation time compared to the nearly 6 h on GPU reported by Cron et al. (2013). We acknowledge that GPU performance has increased over the years, but it is unlikely to significantly diminish the difference in runtimes. Moreover, the estimation of GMMs using the EM algorithm can be made faster using parallelization [20], and can also be implemented on GPUs (e.g. see [26]).

Fig. 2.

(a) Example of a scatter plot showing the result of one of ten MSGMMs fitted to the cell samples taken from [11]. Frequency estimate of antigen-specific cells (large brown squares) is in the bottom right (expressed as a percentage of all events). The expected spike frequency is 0.2254%. (b) Frequency estimates from 10 MSGMM runs (blue circles) together with true values (red crosses), for 6 cell samples. The number in red text above each set of estimates is the difference between the median of the 10 estimates and the ‘true’ value (red crosses), a measure of accuracy

Table 1.

Overview of runtimes

| Experiment | Average time/EM-loop | K | cells | samples | processor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 s | 128 |  |

6 | A |

| 2 | 164 s | 20 |  |

65 | B |

| 3 | 12 s | 16 |  |

359 | A |

| 4 | 639 s | 40 |  |

232 | B |

Processor A is a 2.4 GHz 8-core Intel i9 CPU on a Mac workstation, and processor B is a 2.3 GHz 24-core AMD CPU on a Linux HPC cluster node

Experiment 2: cell classification in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)

The computational efficiency of our approach allows us to scale up multi-sample modeling to larger collections of samples. We show the results of fitting the MSGMM to 65 data samples from the Bue Dura set [12]. These samples represent bone marrow from pediatric patients with B-ALL obtained 15 days after induction therapy and were collected between 2016 and 2017 at the Garrahan Hospital in Buenos Aires. Cells were labeled by experts using manual gating, which provides reliable background information on the location (in observation space) of the leukemic cell populations. To demonstrate how the MGSMM describes a heterogeneous set of samples, we compare it with a regular GMM and fit both models for a range of  components, each time starting from the same initialization. Note that a regular GMM is fit to the pooled data by simply omitting the algorithmic step in Eq. 5, and replacing

components, each time starting from the same initialization. Note that a regular GMM is fit to the pooled data by simply omitting the algorithmic step in Eq. 5, and replacing  with

with  in Eq. 4. In Fig. 3 we show scatter plots of one sample with means and confidence ellipses of the fitted multivariate components of (a) the MSGMM, and (b) the pooled GMM, both with

in Eq. 4. In Fig. 3 we show scatter plots of one sample with means and confidence ellipses of the fitted multivariate components of (a) the MSGMM, and (b) the pooled GMM, both with  . Despite similarities, we see that the two models have converged to different optima. We illustrate the improvement in goodness-of-fit of the MSGMM by selecting in each model one of the components that capture a high percentage of leukemic cells (

. Despite similarities, we see that the two models have converged to different optima. We illustrate the improvement in goodness-of-fit of the MSGMM by selecting in each model one of the components that capture a high percentage of leukemic cells ( in the MSGMM and

in the MSGMM and  in the pooled GMM). For illustrative purposes we select two components with strong visual resemblance in the scatter plots. In Fig. 3c we show a histogram of the logarithm of mixing proportions

in the pooled GMM). For illustrative purposes we select two components with strong visual resemblance in the scatter plots. In Fig. 3c we show a histogram of the logarithm of mixing proportions  of component

of component  over the samples. The red dashed line indicates the value of the logarithm of the mixing proportion

over the samples. The red dashed line indicates the value of the logarithm of the mixing proportion  of component

of component  in the pooled GMM. We see that the distribution of mixing proportions of the MSGMM peaks at a similar (high) value as the pooled GMM, but that there is also heterogeneity, and the distribution decays to very small numbers. Note that mixing proportion values below -13 correspond to less than one cell in the average sample size. This implies that the component is virtually empty in most samples, while in a few samples it captures a large proportion. In Fig. 3d we show the logarithm of sample-specific mixing proportions

in the pooled GMM. We see that the distribution of mixing proportions of the MSGMM peaks at a similar (high) value as the pooled GMM, but that there is also heterogeneity, and the distribution decays to very small numbers. Note that mixing proportion values below -13 correspond to less than one cell in the average sample size. This implies that the component is virtually empty in most samples, while in a few samples it captures a large proportion. In Fig. 3d we show the logarithm of sample-specific mixing proportions  ordered by size for all the samples (grey), together with the single vector of the logarithm of mixing proportions

ordered by size for all the samples (grey), together with the single vector of the logarithm of mixing proportions  of the pooled GMM (red). We see that the sample-specific mixing proportions collectively deviate from the pooled mixing proportions, which exposes the variability of cell populations in the samples. While most samples have some mixture components with high peak values, all samples have a large number of components which are virtually empty. The MSGMM has greater flexibility to allocate components to cell populations with high variability across samples. Although the total, pooled cell density for these cell populations is low, this lower density (in certain samples) will not necessarily have a negative effect on the likelihood function. Note that both normal and leukemic cell populations may show variability across samples. The ability to model heterogeneous sample sets will especially benefit cell classification accuracy when there is high variability in leukemic cell populations. To use the MSGMM for clustering we first average the sample-specific mixing proportions using Eq. 2, which effectively reduces it to a regular GMM.

of the pooled GMM (red). We see that the sample-specific mixing proportions collectively deviate from the pooled mixing proportions, which exposes the variability of cell populations in the samples. While most samples have some mixture components with high peak values, all samples have a large number of components which are virtually empty. The MSGMM has greater flexibility to allocate components to cell populations with high variability across samples. Although the total, pooled cell density for these cell populations is low, this lower density (in certain samples) will not necessarily have a negative effect on the likelihood function. Note that both normal and leukemic cell populations may show variability across samples. The ability to model heterogeneous sample sets will especially benefit cell classification accuracy when there is high variability in leukemic cell populations. To use the MSGMM for clustering we first average the sample-specific mixing proportions using Eq. 2, which effectively reduces it to a regular GMM.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plots of one sample (40,000 cells) from the Bue Dura set, together with GMM component means and 90% confidence level ellipses, of (a) the MSGMM, and (b) the regular GMM fit to pooled data, both with  . In each model we select one of the components that capture a high percentage of leukemic cells:

. In each model we select one of the components that capture a high percentage of leukemic cells:  in the MSGMM (a) and

in the MSGMM (a) and  in the pooled GMM (b). The two components have strong visual resemblance. In (c) we show the histogram of

in the pooled GMM (b). The two components have strong visual resemblance. In (c) we show the histogram of  of component

of component  over the samples, together with the value of the

over the samples, together with the value of the  of component

of component  in the pooled GMM (red dashed line). In (d) we show sample-specific

in the pooled GMM (red dashed line). In (d) we show sample-specific  ordered by size for all the samples (grey), together with the single vector of

ordered by size for all the samples (grey), together with the single vector of  of the pooled GMM (red)

of the pooled GMM (red)

In Table 1 we show cell classification performance of the two  models according to a range of measures, namely sensitivity (or recall), specificity, accuracy, precision, and F-measure. The choice of these measures follows [14]. The measures are formally defined as

models according to a range of measures, namely sensitivity (or recall), specificity, accuracy, precision, and F-measure. The choice of these measures follows [14]. The measures are formally defined as

|

where TP, TN, FP and FN are true positives, true negatives, false positives and false negatives, respectively. We first determine cell clusters which represent leukemic cell populations as clusters which (together) capture  % of labeled leukemic cells. Then we classify cells as leukemic (i.e. positive) when they are labeled as member of one of these predefined leukemic cell clusters. Each of the measures quantifies a different aspect of the classification performance. For example, when we classify many cells as healthy while they have been labeled as leukemic by manual gating, the sensitivity score decreases. The F-measure averages sensitivity and precision and provides a better overall picture of classification performance. The results in Table 2 show that the MSGMM and regular GMM have a similar performance. The heterogeneity in leukemic cell populations in these data may not be challenging enough for a regular GMM to underperform.

% of labeled leukemic cells. Then we classify cells as leukemic (i.e. positive) when they are labeled as member of one of these predefined leukemic cell clusters. Each of the measures quantifies a different aspect of the classification performance. For example, when we classify many cells as healthy while they have been labeled as leukemic by manual gating, the sensitivity score decreases. The F-measure averages sensitivity and precision and provides a better overall picture of classification performance. The results in Table 2 show that the MSGMM and regular GMM have a similar performance. The heterogeneity in leukemic cell populations in these data may not be challenging enough for a regular GMM to underperform.

Table 2.

Comparison of performance measures of the MSGMM and pooled GMM both with  on Bue Dura data set

on Bue Dura data set

| Sensitivity | Precision | Specificity | Accuracy | F-measure |  |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSGMM | 0.96 | 0.97 | 1.0 | 0.99 | 0.96 | − 58976331 |

| GMM | 1.0 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.93 | − 92541767 |

We also show log-likelihood values, the ratio of which exceeds the  quantile of an

quantile of an  distribution with

distribution with  degrees of freedom (

degrees of freedom ( ). This indicates that the multi-sample model provides a significantly better fit to the data than expected on the basis of its excess in parameters. The comparison of models for other values of K gives similar results. See Additional file 1 for an overview. The MSGMM does not necessarily lead to a better fit. In Additional file 1 we provide an example in which the null hypothesis of the likelihood ratio test is generally not rejected (i.e.

). This indicates that the multi-sample model provides a significantly better fit to the data than expected on the basis of its excess in parameters. The comparison of models for other values of K gives similar results. See Additional file 1 for an overview. The MSGMM does not necessarily lead to a better fit. In Additional file 1 we provide an example in which the null hypothesis of the likelihood ratio test is generally not rejected (i.e.  ).

).

Experiment 3: FlowCAP II sample-classification challenge

We test our implementation of the MSGMM on the FlowCAP II sample-classification challenge AML data set [17]. The FlowCAP challenges were established to benchmark performance of computational methods for identifying cell populations in multidimensional FCM data. Most of the algorithms that participated in the challenge performed well (F-measures near 1.00). The HDPGMM was tested on this challenge, not as part of the original FlowCAP publication, but in performance comparisons in (at least) two later publications. In the first paper, the HDPGMM was compared to ASPIRE, which is an anomaly detection method based on the HDPGMM extended with random effects [13]. In the paper, the AML data were used in a more challenging anomaly detection setting and the HDPGMM performed poorly (AUC values near 0.5). In a second paper, the HDPGMM was compared to JCM, which is a very similar model to ASPIRE, but based on maximum likelihood estimation [14]. In the JCM paper, the AML data were used in the original sample-classification setting. There, the HDPGMM performed better but still not very well (averaged F-measure of 0.62 and AUC value 0.725).

Here we test the MSGMM in the original classification setting. The data set consists of peripheral blood or bone marrow samples from a total of 359 patients; 316 were healthy patients and 43 were diagnosed with AML [17]. Samples collected from each patient are assayed into eight tubes with five markers from each tube and two physical parameters (FS, SS), totaling to 2872 data samples. However, the first and last tube (i.e., tubes 1 and 8) are controls and hence not used. Following [13] and [14], the data are transformed logarithmically for the SS parameters and all fluorescent markers, while the FS measurements remain linear. All channels are scaled to the unit interval. Additionally, we have filtered out all cells aligned on the zero and one axes. For training, half of the data set along with known labels (156 healthy patients and 23 AML patients) are used. The challenge called for the construction of a classifier to label the samples in the test set, which is the other half of the data (160 healthy patients and 20 AML patients).

We prepare the MSGMM for the classification challenge as described in Sect. “Methods”. We fit MSGMMs with  mixture components on the train set, and use the sample-specific mixing proportions as feature vectors to train a support vector machine (SVM). We use the fitted MSGMMs to cluster the samples in the test set (step f in Fig. 1), and derive feature vectors from the predicted cluster sizes. We then let the trained SVM predict sample labels from the derived feature vectors. In Table 3 we show the classification results of the MSGMM with

mixture components on the train set, and use the sample-specific mixing proportions as feature vectors to train a support vector machine (SVM). We use the fitted MSGMMs to cluster the samples in the test set (step f in Fig. 1), and derive feature vectors from the predicted cluster sizes. We then let the trained SVM predict sample labels from the derived feature vectors. In Table 3 we show the classification results of the MSGMM with  . Comparison with the results reported in FlowCAP-II [17] shows that the accuracy of the MSGMM is among the best performing algorithms. The classification results also substantially improve the results reported in [13] and [14]. The models with other values of K give similar results. See Additional file 1 for an overview.

. Comparison with the results reported in FlowCAP-II [17] shows that the accuracy of the MSGMM is among the best performing algorithms. The classification results also substantially improve the results reported in [13] and [14]. The models with other values of K give similar results. See Additional file 1 for an overview.

Table 3.

Classification results of the MSGMM with  on the FlowCap AML dataset

on the FlowCap AML dataset

| AML tubes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.55 |

| Precision | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.85 |

| Specificity | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| F-measure | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.67 |

| AUC | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.90 |

Experiment 4: sample classification in HOVON-SAKK-132 bone marrow samples

Next, we demonstrate the effectiveness of MSGMM modeling using 211 data samples from the HOVON-SAKK-132 trial [27]. These samples represent bone marrow from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients at diagnosis, and contain  to

to  cells per sample. We include 21 normal bone marrow (NBM) samples (healthy donors) as a control group, giving a total of 232 samples (

cells per sample. We include 21 normal bone marrow (NBM) samples (healthy donors) as a control group, giving a total of 232 samples ( cells). We fit a MSGMM with

cells). We fit a MSGMM with  mixture components and apply agglomerative hierarchical clustering (using Ward’s method) to both rows and columns of the matrix of mixing proportions (

mixture components and apply agglomerative hierarchical clustering (using Ward’s method) to both rows and columns of the matrix of mixing proportions ( -matrix). In Fig. 4 we show a heatmap of the clustered

-matrix). In Fig. 4 we show a heatmap of the clustered  -matrix. We see that the 21 NBM samples are clustered in 3 groups (of size 16, 4, and 1) indicated with blue bars. The heatmap of the

-matrix. We see that the 21 NBM samples are clustered in 3 groups (of size 16, 4, and 1) indicated with blue bars. The heatmap of the  -matrix also shows that many ‘spikes’ in value are present in only a few samples. This is as expected, as AML is a heterogeneous disease; leukemic cell populations may be rare and manifested in only a few patients.

-matrix also shows that many ‘spikes’ in value are present in only a few samples. This is as expected, as AML is a heterogeneous disease; leukemic cell populations may be rare and manifested in only a few patients.

Fig. 4.

Heatmap of  -matrix after agglomerative hierarchical clustering of both rows and columns (dendrograms not shown). Each row is a vector of mixing proportions

-matrix after agglomerative hierarchical clustering of both rows and columns (dendrograms not shown). Each row is a vector of mixing proportions  for one sample. Blue bars in the vertical strip on the left side of the heatmap indicate positions of the NBM samples (3 groups of size 16, 4 and 1). Colors are scaled row-wise

for one sample. Blue bars in the vertical strip on the left side of the heatmap indicate positions of the NBM samples (3 groups of size 16, 4 and 1). Colors are scaled row-wise

We analyse the  -matrix using the expression level ratio (Eq. 14), which for each component k in the model calculates the ratio between the maximum value of

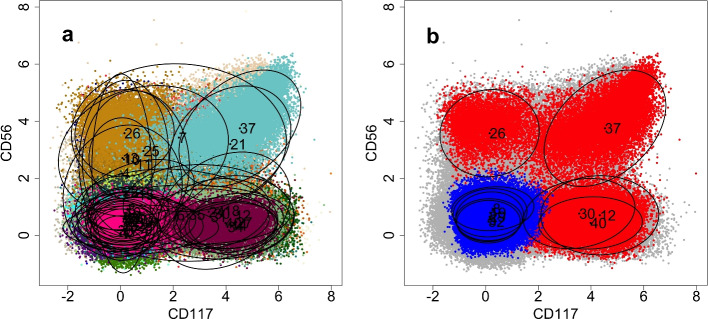

-matrix using the expression level ratio (Eq. 14), which for each component k in the model calculates the ratio between the maximum value of  in the subsets of leukemic samples and NBM samples. The expression level ratio gives an ordering of mixing components according to their likelihood of representing a leukemic cell population. In Fig. 5 we show scatterplots of a subsample of the H132 sample set, clustered using the trained MSGMM. In Fig. 5b we show mixture components (means and confidence ellipses) of the 5 most likely components, according to the ordering by the expression level ratio. We have also colored cells assigned to these components (red). We also show the 5 least likely components, and colored assigned cells (blue). These clusters follow a ‘reverse scenario’, and are more strongly expressed in the NBM samples. We also see that the 5 most likely components (37, 12, 26, 40, 30) are dispersed in the feature space, while the reverse scenario clusters have overlapping locations. In the heatmap (Fig. 4) we see that several of the reverse scenario clusters (29, 8, 5, 19, 32) are grouped, which means their higher expression level is common to the NBM samples.

in the subsets of leukemic samples and NBM samples. The expression level ratio gives an ordering of mixing components according to their likelihood of representing a leukemic cell population. In Fig. 5 we show scatterplots of a subsample of the H132 sample set, clustered using the trained MSGMM. In Fig. 5b we show mixture components (means and confidence ellipses) of the 5 most likely components, according to the ordering by the expression level ratio. We have also colored cells assigned to these components (red). We also show the 5 least likely components, and colored assigned cells (blue). These clusters follow a ‘reverse scenario’, and are more strongly expressed in the NBM samples. We also see that the 5 most likely components (37, 12, 26, 40, 30) are dispersed in the feature space, while the reverse scenario clusters have overlapping locations. In the heatmap (Fig. 4) we see that several of the reverse scenario clusters (29, 8, 5, 19, 32) are grouped, which means their higher expression level is common to the NBM samples.

Fig. 5.

Scatter plots of a subsample of the H132 sample set (500,000 cells), clustered by a MSGMM with  mixture components. In (a) we show all components and corresponding clustered cells colored arbitrarily. In (b) we show both the 5 most likely components (37, 12, 26, 40, 30) and reverse scenario clusters (29, 8, 5, 19, 32) and corresponding clustered cells (red and blue respectively)

mixture components. In (a) we show all components and corresponding clustered cells colored arbitrarily. In (b) we show both the 5 most likely components (37, 12, 26, 40, 30) and reverse scenario clusters (29, 8, 5, 19, 32) and corresponding clustered cells (red and blue respectively)

In Fig. 6 we show heatmaps of the component means over the marker expressions, which can be used for interpretation of the clusters. In Fig. 6a we show a heatmap with both rows and columns hierarchically clustered. For clustering we use the average link method, with Euclidean distance metric. For the color mapping the expression levels are scaled column-wise using MinMax scaling. In Fig. 6b we show the heatmap with rows (components) ordered according to the expression level ratio, starting from the top with the most likely AML components. We see that both CD34 and CD117 find higher expression levels especially in the most likely (top 13) components, which is in agreement with our expectation based on prior knowledge. On the other hand we see that CD7 and CD56 expressions seem independent from the association to AML. Though the clustering in Fig. 6a shows a block structure, the grouping of components seems independent from the ordering according to expression level ratio (in Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Component means over the marker expressions. In (a) we show a heatmap with both rows and columns hierarchically clustered, and in (b) we show a heatmap with rows (components) ordered according to their expression level ratio, starting at the top with the most likely AML components

To make the sample classification based on the  -matrix more objective, we approach it as a supervised classification problem (see Sect. “Methods”). The estimated sample-specific mixing proportions function as feature vectors while the sample status (AML/healthy) is a class label. We fit a MSGMM with

-matrix more objective, we approach it as a supervised classification problem (see Sect. “Methods”). The estimated sample-specific mixing proportions function as feature vectors while the sample status (AML/healthy) is a class label. We fit a MSGMM with  mixture components on half of the data set (105 AML and 11 normal samples), and train a support vector machine (SVM) on the resulting

mixture components on half of the data set (105 AML and 11 normal samples), and train a support vector machine (SVM) on the resulting  -matrix. We use the fitted MSGMM to cluster the other half of the data set (106 AML and 10 normal samples, step f in Fig. 1), and normalize the predicted cluster sizes to get mixing proportions. We then let the trained SVM predict sample labels from the estimated mixing proportions. In this setup only one sample is mis-classified as a false negative.

-matrix. We use the fitted MSGMM to cluster the other half of the data set (106 AML and 10 normal samples, step f in Fig. 1), and normalize the predicted cluster sizes to get mixing proportions. We then let the trained SVM predict sample labels from the estimated mixing proportions. In this setup only one sample is mis-classified as a false negative.

Discussion

Creating a model for multiple samples simultaneously is a common challenge in FCM data analyses. Here we have shown how GMMs can be extended to model large data sets consisting of multiple samples, using a computational efficient implementation of the EM algorithm. The use of summary statistics in the EM algorithm avoids any limitation set by computer memory size. By introducing intermediate M-steps for estimating sample-specific mixing proportions we capture the multi-sample structure of the data within the set of model parameters. This allows us to model any possible heterogeneity in the distribution of cell populations across the samples. In doing so, we have recovered the efficiency of the basic multi-sample GMM which underlies the sophisticated non-parametric Bayesian optimization framework of the HDPGMM. Non-parametric Bayesian optimization approaches are theoretically interesting but computationally demanding, and therefore do not relate well to the requirement of scalability. This limits their utility in the analysis of large sets of large FCM samples.

We have shown that the MSGMM is competitive in performance with computationally more complex models such as HDPGMM, ASPIRE, and JCM. The MSGMM has a similar accuracy in detection of rare cells as the HDPGMM, while the gain in runtime is from hours to minutes. We have also shown that the MSGMM is among the top performers in the FlowCAP II sample-classification challenge. The reported performance of the HDPGMM on the FlowCAP II challenge was poor, both in comparison to JCM [14] and to ASPIRE [13]. As the MSGMM in fact underlies the HDPGMM we suggest this previous poor performance has been due to other reasons. Possible explanations for the poor performance may hide in sample pre-processing steps in the case of [14]. In the case of [13] there may be a mismatch between model design and the experimental setting of anomaly detection, which deviates from the traditional classification setting of the FlowCAP II contest.

The possibility of fitting models to large sets of FCM samples provides opportunities for the discovery of associations between sample composition and sample meta-data. We have demonstrated how the model output can be analysed using simple heuristics to expose the inherent structure in a collection of FCM samples. The model output can also form the input for more ‘black box’-like approaches using machine learning classifiers. An interesting application we are currently working on is the deployment of MSGMMs in longitudinal studies, where they can be used to track the dynamic presence and absence of cell clusters in samples of patients at different therapeutic time points. The dynamic evolution of cell clusters can then be associated with different treatment responses and clinical outcomes.

A well-known problem of finite mixture models is finding the number of clusters K, which is not known in advance. An elegant property of non-parametric mixture models such as HDPGMM is that K is inferred from the data, as an additional parameter to be estimated in the model fitting procedure. In practice however, this property of non-parametric mixture models is used in an exploratory manner to indicate relevant ranges of K. For example, Cron et al. (2013) [11] upper truncate the HDPGMM at fixed K and evaluate the model at the truncation value. The lower bound of K is approximated in multiple trial runs of the model. Moreover, the HDPGMM allows multiple components to represent a single cell cluster in order to capture more complex, non-Gaussian cluster shapes. Note that the HDPGMM is implemented with an additional cluster merging step, which creates an additional mapping of components to the model.

In this research we adhere to a similar approach and a priori specified the number of clusters such that we create an expected over-clustering, in which multiple Gaussian mixture components can model a single cell population. Such an over-clustering is not detrimental to the analysis of heterogeneous sets of samples and finding meaningful structure for classification purposes. Moreover, the possibility of multiple Gaussian components describing a cell population increases the model’s flexibility to describe more complex shapes.

However, it may be that determining the correct number of cell populations is an important part of the analysis. In that case, the optimal K can be estimated in a fully unsupervised manner by performing a model selection based on the Bayesian Information Criterium (BIC). This approach involves fitting a model repeatedly for a range of values for K, and calculating the BIC score. One then searches a value of K for which the difference in successive BIC scores substantially decreases. Fitting many models to large data sets is computationally expensive, and even more cumbersome in case of large collections of samples. Additionally, it has been shown that BIC optimizes K for the best approximating density distribution, and therefore overestimates the correct size regardless of the separation of the clusters [28]. Although a method has been proposed by Baudry et al. (2010) [29] to solve the issue, we do not pursue it here as estimating the correct number of clusters is not critical. However, we note that making the method proposed in Baudry et al. (2010) [29] compatible with our efficient implementation of the EM algorithm is an interesting opportunity for future research.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Additional file 1: The additional file contains a comparison of runtimes between MSGMM and ASPIRE, experimental results of the MSGMM on the Bue Dura B-ALL data for different values of K, and experimental results of the MSGMM on the FlowCAP II AML data for different values of K.

Author contributions

JC, CB and WW organised the research project. PR and WW conceived and wrote the paper, CB and TM edited and gave advice. PR wrote the code and conducted the experiments. CB and TM collected and preprocessed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work has been funded by Stichting Cancer Center Amsterdam (grant ID CCA2020-9-68).

Data availability

The blood samples with predefined number of T cells are available as Supporting Information in Cron et al. (2013) and can be accessed at: https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003130. The FlowCAP II AML data set from Aghaeepour et al. (2013) are available from http://flowrepository.org/id/FR-FCM-ZZYA. The Bue Dura B-ALL data and HOVON-SAKK-132 AML data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Involvement of human participants was approved by the institutional review boards of Amsterdam UMC (#METC 2023.0883) for in-house participants and Erasmus MC (#MEC-2013-539) for patients in the HOVON-SAKK-132 trial. This research adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. All individuals provided written consent, and approval was obtained from the ethics committees of the participating institutions.

2023.0883) for in-house participants and Erasmus MC (#MEC-2013-539) for patients in the HOVON-SAKK-132 trial. This research adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. All individuals provided written consent, and approval was obtained from the ethics committees of the participating institutions.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Philip Rutten, Email: p.rutten@amsterdamumc.nl.

Costa Bachas, Email: c.bachas@amsterdamumc.nl.

References

- 1.Liechti T, Weber LM, Ashhurst TM, Stanley N, Prlic M, Gassen SV, et al. An updated guide for the perplexed: cytometry in the high-dimensional era. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:1190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aghaeepour N, Nikolic R, Hoos HH, Brinkman RR. Rapid cell population identification in flow cytometry data. Cytometry Part A. 2011;79(A):6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saeys Y, Gassen SV, Lambrecht BN. Computational flow cytometry: helping to make sense of high-dimensional immunology data. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:449–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber LM, Robinson MD. Comparison of clustering methods for high-dimensional single-cell flow and mass cytometry data. Cytometry A. 2016;89A:1084–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azad A, Langguth J, Fang Y, Qi A, Pothen A. Identifying rare cell populations in comparative flow cytometry. In: Vincent Moulton, M.S. (ed.) Algorithms in Bioinformatics. Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics, 2010; pp. 162–175. Springer.

- 6.Azad A, Pyne S, Pothen A. Matching phosphorylation response patterns of antigen-receptor-stimulated t cells via flow cytometry. BMC Bioinform. 2012;13(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Pyne S, Hua X, Wang K, Rossin E, Lin T-I, Maier LM, et al. Automated high-dimensional flow cytometric data analysis. PNAS. 2009;106(21):8519–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnsson K, Wallin J, Fontes M. Bayesflow. Latent modeling of flow cytometry cell populations. BMC Bioinform. 2016;17(25). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Naim I, Datta S, Rebhahn J, Cavenaugh JS, Mosmann TR, Sharma G. Swift-scalable clustering for automated identification of rare cell populations in large, high-dimensional flow cytometry datasets, part 1: Algorithm design. Cytometry Part A. 2014;85(A):408–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebhahn JA, Roumanes DR, Qi Y, Khan A, Thakar J, Rosenberg A, et al. Competitive swift cluster templates enhance detection of aging changes. Cytometry Part A. 2016;89(A):59–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cron A, Gouttefangeas C, Frelinger J, Lin L, Singh SK, Britten CM, et al. Hierarchical modeling for rare event detection and cell subset alignment across flow cytometry samples. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(7):1003130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiter M, Diem M, Schumich A, Maurer-Granofszky M, Karawajew L, Rossi JG, et al. International berlin-frankfurt-münster (ibfm)-flow-network, autoflow consortium: automated flow cytometric mrd assessment in childhood acute b- lymphoblastic leukemia using supervised machine learning. Cytometry A. 2019;95(9):966–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dundar M, Akova F, Yerebakan HZ, Rajwa B. A non-parametric bayesian model for joint cell clustering and cluster matching: identification of anomalous sample phenotypes with random effects. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(314). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Lee SX, McLachlan GJ, Pyne S. Modeling of inter-sample variation in flow cytometric data with the joint clustering and matching procedure. Cytometry Part A. 2016;89(A):30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin L, Hejblum BP. Bayesian mixture models for cytometry data analysis. WIREs Comput Stat. 2021;13(4):1535. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB. Bayesian Data Analysis. 3rd ed. CRC Press. 2014.

- 17.Aghaeepour N, Finak G, Consortium TF, Consortium TD, Hoos H, Mosmann TR, Brinkman R, Gottardo R, Scheuermann RH. Critical assessment of automated flow cytometry data analysis techniques. Nat Methods. 2013;10(3):228–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the em algorithm. J Roy Stat Soc B. 1977;39(1):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy KP. Machine learning: a probabilistic perspective. MIT Press. 2012.

- 20.Sanderson C, Curtin R. An open source c++ implementation of multi-threaded gaussian mixture models, k-means and expectation maximisation. International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication Systems 2017. Associated C++ source code: http://arma.sourceforge.net.

- 21.McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite mixture models. Wiley-Interscience. 2000.

- 22.Ledoit O, Wolf M. A well-conditioned estimator for large-dimensional covariance matrices. J Multivar Anal. 2004;88:365–411. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eddelbuettel D, Francois R. Rcpp: seamless r and c++ integration. J Stat Softw. 2011;40(8):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eddelbuettel D, Sanderson C. Rcpparmadillo: accelerating r with high-performance c++ linear algebra. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2014;71:1054–63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hejblum BP, Alkhassim C, Gottardo R, Caron F, Thiebaut R. Sequential dirichlet process mixtures of multivariate skew t-distributions for model-based clustering of flow cytometry data. The Annals of Applied Statistics 2019;13(1) . R package NPflow available at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=NPflow.

- 26.Machlica L, Vanek J, Zajic Z. Fast estimation of gaussian mixture model parameters on gpu using cuda. In: 12th IEEE International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Computing, Applications and Technologies 2011.

- 27.Lowenberg B, et al. Addition of lenalidomide to intensive treatment in younger and middle-aged adults with newly diagnosed aml: the hovon-sakk-132 trial. Blood Adv. 2021;5(4):1110–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biernacki C, Celeux G, Govaert G. Assessing a mixture model for clustering with the integrated completed likelihood. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2000;22(7):719–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baudry JP, Raftery AE, Celeux G, Lo K, Gottardo R. Combining mixture components for clustering. J Comput Graph Stat. 2010;19(2):332–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Additional file 1: The additional file contains a comparison of runtimes between MSGMM and ASPIRE, experimental results of the MSGMM on the Bue Dura B-ALL data for different values of K, and experimental results of the MSGMM on the FlowCAP II AML data for different values of K.

Data Availability Statement

The blood samples with predefined number of T cells are available as Supporting Information in Cron et al. (2013) and can be accessed at: https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003130. The FlowCAP II AML data set from Aghaeepour et al. (2013) are available from http://flowrepository.org/id/FR-FCM-ZZYA. The Bue Dura B-ALL data and HOVON-SAKK-132 AML data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.