Abstract

Background

In stem cell biology, a long-held structure–function relationship is the domed colony morphology and naïve pluripotency for mouse or human pluripotent stem cells. This link has provided a convenient way to recognize bona fide naïve pluripotent cells during derivation, passaging and characterization. However, the molecular basis of this link remains poorly understood.

Results

We show that a loss of domed morphology may not impact the overall genetic architecture of naïve pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). We first generated stable mESC lines by knocking out Myh9 that encodes non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA, resulting in colonies deprived of the typical domed morphology, but competent to differentiate into the three germ layers and chimeric mice. Modulating cell morphologies with inhibitors against kinases known to regulate myosin pathway also phenocopy the knockout in wild type mESCs.

Conclusions

These results provide evidence that the domed morphology and potency can be uncoupled and suggest that domed structure is not a pre-requisite for acquiring and maintaining naïve pluripotency.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13578-025-01497-5.

Keywords: Morphology, Mouse embryonic stem cell, Non-muscle myosin IIA, Pluripotency

Background

Embryonic stem cells or ESCs are characterized by the capacity of self-renewal and the generation of all cell lineages in adult organism, which makes ESCs an invaluable model for studying mammalian development and cell fate control in vitro. The naïve mouse embryonic stem cells are derived from inner cell mass (ICM) of preimplantation blastocysts [1, 2], and cultured with serum medium supplementary with leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) [3, 4] or chemical defined ground state medium N2B27 with LIF, CHIR99021 (glycogen synthase kinase-3 selective inhibitor), and PD0325901 (selective MAP kinase/ERK kinase inhibitor) [5]. Under both naïve conditions, mESCs have a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, form dome-shaped colonies of tightly packed cells [6]. Therefore, prevailing dogma in the stem cell field has held that the dome-shaped colony morphology represents an intrinsic feature of naïve pluripotent stem cells and has been widely adopted as a critical morphological criterion for not only quality but also potency [5, 7, 8]. However, the biological significance of this dome-forming capacity in relation to pluripotency and cell fate transition remains poorly understood.

The molecular basis of the unique morphology for ESCs remains little known. While microtubules are uniformly distributed throughout the colony, filamentous actin (F-actin) is enriched at the cell and medium boundary, forming a three-dimensional supracellular actomyosin cortex with non-muscle myosin IIA (NMIIA) and E-cadherin [9]. Inside the cells, the actin cortex consists of a sparse and isotropic network regulated by Arp2/3, formin and capping protein, where MNIIA is largely independent [10]. NMIIA is a motor and crosslinker widely recognized for its pivotal roles in the contractility and pre-stress of the actin cortex, modulating cellular morphology, adhesion, and migration [11]. NMIIA also plays crucial roles throughout early embryonic development. Post-fertilization, as embryonic cells undergo division, the 8-cell embryo acquires multiple morphological configurations, and NMIIA-dependent cortical contractility drives embryo compaction into the lowest surface energy configuration, establishing differential fates between outer and inner cells, ultimately mediating the segregation of the ICM and trophectoderm (TE) [12]. At the blastocyst stage, inhibition of NMIIA disrupts the normal separation of epiblast and primitive endoderm lineages [13]. Later, the embryos exhibit developmental arrest at E6.5 due to the failure to establish proper polarization and visceral endoderm [14]. Despite these advances, it remains unclear how NMIIA regulates morphology and potency of mESCs.

Here we report a broken link between morphology and potency in mESCs. By deleting a gene coding for the heavy chain of NMIIA (Myh9), we demonstrate that the resulting cells lose the typical dome-like colony morphology, but retain their self-renewal capacity and pluripotency to differentiate into the three germ layers, suggesting that the classical domed colony morphology is not required for naïve embryonic stem cell identity.

Methods

Cell culture

Mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) were derived in-house from embryonic day 3.5 and 5.5 embryos, respectively, by crossing male mice carrying an Oct4-GFP transgenic allele (CBA/CaJ × C57BL/6 J) with female 129/Sv mice. Human embryonic kidney 293 T (HEK293T) cells and human embryonic stem cell line H9 were purchased from ATCC.

Mouse ESCs were maintained feeder-free on 1% gelatin (Millipore, ES-006-B) coated plastic plate with N2B27 + 2i/LIF medium unless indicated [1:1 (v/v) mix of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/high glucose (Hyclone, SH30243.01) and knock out DMEM (GIBCO, 10829018) supplemented with 1% (v/v) N2 supplement (GIBCO, A1370701), 2% (v/v) B27 supplement (GIBCO, 17504044), 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate solution (GIBCO, 11360070), 1% (v/v) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO, 11140035), 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX solution (GIBCO, 35050061), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO, 21985023), 1000 U/mL LIF (LOFETECH, L00100G), 3 μM CHIR99021 (Targetmol, USA, T2310), and 1 μM PD0325901 (TargetMol, USA, T6189)]. For cultured on feeders or without feeders, used mES + 2i/LIF medium [DMEM/high glucose (Hyclone) supplemented with 15% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Front Biomedical, OF-1029A), 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX solution (GIBCO), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO), 1000 U/mL LIF (LOFETECH), 3 μM CHIR99021 (TargetMol, USA), and 1 μM PD0325901 (TargetMol, USA)]. Y27632 (TargetMol, USA, T1729), Thiazovivin (TargetMol, USA, T2155) and Blebbistatin (Selleck, S7099) were added to mES + 2i/LIF medium at the concentration of 5 μM.

Mouse EpiSC were maintained feeder-free on fetal bovine serum (Front Biomedical) coated dishes in FAX medium [1:1 (v/v) mix of DMEM/F12 (GIBCO, 10565042) and Neurobasal (GIBCO, 21103049) supplemented with 1% (v/v) N2 supplement (GIBCO), 2% (v/v) B27 supplement (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate solution (GIBCO), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO), 15 ng/mL bFGF (PeproTech, 100-18B), 20 ng/mL Activin A (PeproTech, 12014) and 1 μM XAV939 (Sigma, X3004)]. EpiSCs, dissociated with StemPro™ Accutase Cell Dissociation Reagent (GIBCO, A11105-01), were passaged as single cells in FAX medium with 5 μM Y27632 (Targetmol, USA).

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM/high glucose (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Vazyme, F103-01), 1% (v/v) GlutaMax solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO), and 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate solution (GIBCO).

Human ESCs were maintained in mTeSR1 (STEMCELL Technologies, 85850) on Matrigel (Corning, 354230)-coated plates, and passaged using 0.5 mM EDTA (Thermofisher, 15575020) in mTeSR1 medium supplemented with 5 μM Y27632 (Targetmol, USA).

All cell lines were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2, and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination with Myco-Lumi™ Luminescent Mycoplasma Detection Kit for High Sensitivity Instrument (Beyotime, C0298).

Differentiation assay

For random differentiation, mESCs were dissociated and plated at a density of 2 × 104 cells/cm2 in mES medium without 2i/LIF and analyzed after 24 h incubation.

For neuroectodermal differentiation, mESCs were dissociated and plated onto 0.1% gelatin-coated plastic plate at a density of 2 × 104 cells/cm2 in N2B27 medium [1:1 (v/v) mix of DMEM/F12 (GIBCO) and Neurobasal (GIBCO) supplemented with 1% (v/v) N2 supplement (GIBCO), 2% (v/v) B27 supplement (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate solution (GIBCO) and 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO)] and analyzed after 24 h incubation.

For Naïve to Primed differentiation, mESCs were dissociated and plated at 1 × 104 cells/cm2 in mES + 2i/LIF medium. After 24 h, the medium was replaced by FAX medium for 3 days and passaged onto plastic plate coated with Matrigel (Corning) for another 3 days until Oct4-GFP silenced prior to analysis.

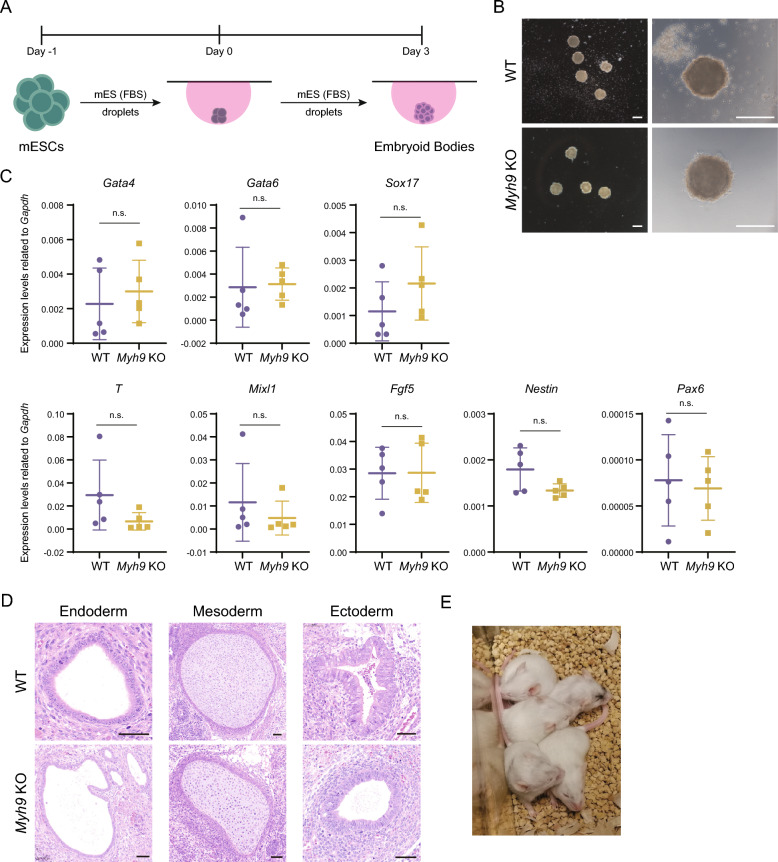

For embryoid bodies formation, mESCs were dissociated and suspended at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL in mES medium without 2i/LIF. The cell suspension was added as droplets onto the lid of a 15-cm culture dish, which was then inverted and suspended for culture, with each droplet 20 μL and each cell line 200 droplets. The embryonic bodies were collected on the third day for analysis.

The protocol for the derivation of neural stem cells from ESCs was described previously [15] with minor modifications. mESCs were passaged onto gelatin (Millipore)-coated 6-well plates in mES medium without 2i/LIF for 2 days. Then the cells were dissociated with Accutase (GIBCO) and seeded into low-adhesive 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in NDEF medium [1:1 (v/v) mix of DMEM/F12 (GIBCO) and Neurobasal (GIBCO) supplemented with 1% (v/v) N2 supplement (GIBCO), 2% (v/v) B27 supplement (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate solution (GIBCO), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO), 50 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, SRE0098), 20 ng/mL bFGF (PeproTech), 20 ng/mL EGF (PeproTech, AF-100-15)] for 3 days to form neurospheres. Then the neurospheres were seeded into gelatin-coated 12-well plate and cultured in NSC medium [DMEM/F12 (GIBCO) supplemented with 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate solution (GIBCO), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) N2 supplement (GIBCO), 10 ng/mL EGF (PeproTech), 10 ng/mL bFGF (PeproTech), 50 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich)] for about 5 days. After the NSCs migrated out from the neurospheres, the spheres were removed, then the remaining cells were collected for analysis.

Human naïve pluripotent stem cell induction

The protocol for the derivation of human 4-cell like naïve pluripotent cells was described previously [16] with minor modifications. Primed human ESCs H9 were dissociated into single cells with 0.5 mM EDTA (Thermofisher) and plated at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2 on feeders in mTeSR1 medium supplemented with 10 μM Y27632 (Targetmol, USA). 24 h later, the medium was switched to 4CL medium [1:1 (v/v) mix of Neurobasal medium (GIBCO) and Advanced DMEM/F12 (GIBCO, 12634028) supplemented with 1% (v/v) N2 supplement (GIBCO) and 2% (v/v) B27 supplement (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO), 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX solution (GIBCO), 10 nM DZNep (Selleck, S7120), 5 nM TSA (Vetec, V900931), 1 μM PD0325901 (TargetMol, USA), 5 μM IWR-1 (Selleck, S7086), 20 ng/mL human LIF (Peprotech, 30005), 20 ng/mL Activin A (Peprotech), 50 μg/mL L-ascorbic acid (Sigma, A8960) and 0.2% (v/v) Matrigel (Corning)]. 4CL medium was refreshed every day, and cells were passaged as single cells (1:4) every 4 days with 5 μM Y27632 (TargetMol, USA) added in the medium for the first 24 h.

Plasmid construction and lentivirus production

For Myh9 knockout, guide RNA (sgRNA) sequences targeted for mouse Myh9 and human MYH9 gene locus were obtained from chopchop.cbu.uib.no, and cloned downstream of the human U6 promoter of LentiCas9-V2 vector (Addgene). sgRNA sequences were listed in Table S1 (see Additional file 2).

For overexpression, mouse Myh9 and its head domain or tail domain, and human MYH9 were cloned from the cDNA of mESCs and HEK293T cells respectively into the pKD-EF1α-IRES-Blast expression vector.

For Myh9 knockdown, short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences targeted for mouse Myh9 mRNA were obtain from www.sigmaaldrich.cn, and cloned downstream of the human U6 promoter of pLKO.1 vector (Addgene). shRNA sequences were listed in Table S1 (see Additional file 2).

For lentivirus generation, HEK293T cells were seeded to reach 85%-90% confluences, and transfected with plasmid, PAPX2, PMD.2G and Polyethylenimine Linear (PEI) (Yeasen, MW40000) solution. Lentivirus were collected 48 h after transfection and concentration with Lenti-X Concentrator (Takara, 631232).

Gene knockout, knockdown and overexpression

MYH9 knockout mouse ESCs lines and human naïve PSCs were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

For Myh9 KO in mouse ESCs, LentiCas9-V2 plasmid with guide RNA targeted the 6th exon of Myh9 was transfected into mESCs with LIPOFECTAMINE 3000 (Invitrogen, L3000015). After 1 μg/mL puromycin (GIBCO, A1113803) selection for 48 h, mESCs were collected and suspended with mES + 2i/LIF medium in low density to pick up single cell into a new well. Mouse ESCs clones carrying mutations in both alleles were identified by cell morphology, genotyping and western blot.

For MYH9 KO in human naïve PSCs, after induction in 4CL medium for 4 days, the cells are dissociated into single cells with 0.5 mM EDTA (Thermofisher), and plated on feeders with 4CL medium supplemented with 5 μM Y27632 (TargetMol, USA) and 0.5 mg/mL polybrene (Solarbio, H8761) and infected with concentrated lentivirus for 8 h. 72 h after infection, the cells were selected by 1 μg/mL puromycin (GIBCO) for another 2 days. Then followed by replated into confocal dishes coated with feeder cells for further analysis.

For Myh9 overexpression or knockdown in mESCs, the cells are dissociated into single cells with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (GIBCO, 2764740), and infected with 0.8 mg/mL polybrene (Solarbio) and concentrated lentivirus for 6 h. 48 h after infection, the cells were selected by 1 μg/mL puromycin (GIBCO) or 5 μg/mL blasticidin S HCl (GIBCO, 982553) for another 2 days. Then followed by seeded into appropriate culture dishes for further analysis.

Genomic DNA extraction and genotyping

Genomic DNA of mouse ESCs were extracted with TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (Tiangen, DP304-03). Phanta Max Master Mix (Vazyme, P525-03) was used in all PCR reactions. PCR primers for genotyping were listed in Table S2 (see Additional file 2).

Western blot

Cells were lysed on ice in RIPA buffer (Sigma, V900854) supplemented with 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (EDTA free) (MCE, HY-K0010) and 1% (v/v) phosphatase inhibitor cocktail III (MCE, HY-K0023). The whole cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto the PVDF membrane (Millipore, IPVH00010). After blocked with 5% skimmed milk (PSAITONG, S10191) for 2 h at room temperature, membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1.5 h at room temperature. After washed thrice, membranes were detected using Omni-ECL™ Femto Light Chemiluminescence Kit (Epizyme Biotech, SQ201) by ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad). The antibodies and dilutions used were: Myosin IIA (Cell Signaling Technology, 3403, 1:1000), NANOG (Abcam, ab214549, 1:1000), OCT4 (Santa Cruz, sc-5379, 1:200), SOX2 (Proteintech, 11064-1-AP, 1:1000), KLF4 (Cell Signaling Technology, 12173, 1:1000), HRP-conjugated GAPDH (Proteintech, HRP-60004, 1:5000), HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (Byotime, A0208, 1:2000), HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (Byotime, A0216, 1:2000).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (BBI, E672002-0500) for 30 min at room temperature. After washed thrice, the cell samples were blocked and permeabilized using PBS (GIBCO, C10010500BT) supplemented with 1.5% BSA (Sigma, V900933) and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, X100) for 40 min at room temperature. After washed thrice, cells were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Images were captured with Axio Vert.A1 Microscope (Zeiss) or Confocal Microscope LSM 800 or 980 (Zeiss). The antibodies and dilutions used were: Myosin IIA (Cell Signaling Technology, 3403, 1:50), NANOG (Abcam, ab214549, 1:100), E-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology, 14472, 1:100), H3K27me3 (Abcam, ab6002, 1:200), KLF17 (Atlas antibodies, HPA024629-L, 1:200), Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (Cell Signaling Technology, 8889S, 1:1000), Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (Cell Signaling Technology, 4414S, 1:1000), Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (Cell Signaling Technology, 8890S, 1:1000), Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (Cell Signaling Technology, 4412S, 1:1000), Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (Cell Signaling Technology, 4408S, 1:1000).

For mitochondria staining, mouse ESCs and EpiSCs were plated in gelatin-coated confocal dishes to reach desired confluency. Removed the culture medium and added 37 °C prewarmed staining solution [400 nM MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Invitrogen, A66443) diluted in Opti-MEM I (GIBCO, 31985070)], incubated 20 min under growth conditions. Then the cells were washed with fresh growth medium, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (BBI) for 15 min at 37 °C. Washed the cells again with PBS, stained with DAPI stanning solution (Abcam, ab228549) for 10 min at room temperature. Images were captured with Confocal Microscope LSM 980 (Zeiss).

Cell viability assay

mESC cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well in mES + 2i/LIF medium. After 0, 24, 48, and 72 h, cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Beyotime, C0039) following manufacturer’s instructions. Specifically, 10 μL of the solution was added to each well and incubated for 1 h, and absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer (Thermo, Varioskan LUX).

Cell cycle

Cell cycle was performed using a cell cycle and apoptosis analysis kit (Beyotime, C1052) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, mESCs were dissociated and plated at 2 × 104/cm2 in mES + 2i/LIF medium. After 48 h, the cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (GIBCO), washed with ice-cold PBS, centrifuged at 1,000 rcf for 3 min. Removed the supernatant and fixed the cell pellet with 70% ice cold ethanol at 4 °C for 2 h. Centrifuged to remove the supernatant again, and washed the cell pellet with ice cold PBS again. The cell pellet was stained by propidium at 37 °C for 30 min, and red fluorescence was analyzed via flow cytometry (Beckmen, CytoFLEX LX) using 488 nm excitation with FL2 channel detection (emission filter: 575/26 nm). Data analysis was carried out using FlowJo v.10.8.1.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR

Total RNA was isolated with FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit V2 (Vazyme, RC112-01) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified by Multiskan Sky-High Microplate Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). About 2 μg of total RNA samples were reverse transcribed employing HiScript II QRT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme, R222-01) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then qRT-PCR were performed using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Q711-03) by CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad). qPCR primers are listed in Table S3 (see Additional file 2).

RNA-seq

About 1 μg of total RNA was used for sequencing library construction by the VAHTS Universal V10 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Vazyme, NR606-01) and was sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq PE150 platform. The RNA-seq reads were trimmed using Trim Galore (v0.6.4)38 and then mapped to the mm10 reference genome with HISAT2 (v2.2.1)39. StringTie (v2.2.1)40 was used to quantify the transcription level of each gene in each sample into FPKM (Fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads). GFOLD (v1.1.4)41 was used to perform differential expression analysis between conditions. The differentially expressed genes were identified with g-fold value > 0.5.

Metabolic pathway analysis

Mouse ESCs and EpiSCs are plated into 12-well plate to reach desired confluency. Then treated the cells with 50 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose (Targetmol, USA, T6742) at culture conditions for 24 h. Images were captured with Axio Vert.A1 Microscope (Zeiss). Dissociated the cells with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (GIBCO), and cell counts are counted by Countess 3 (Invitrogen).

Teratoma formation

The experimental use of mice was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Westlake University, Hangzhou, China (AP#23–109–PDQ). Wild type and Myh9−/− mESCs were dissociated by 0.25% Trypsin–EDTA (GIBCO) for 1 min at room temperature and resuspended in mES + 2i/LIF medium with 50% (v/v) Matrigel (Corning), and then injected subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice. The mice used here (male, 5–6 weeks, NCG) were purchased from GemPharmatech. The animal manipulations were performed according to the applicable guidelines and regulations of Westlake University, Hangzhou, China. Teratomas were collected after 17 days and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E). The sizes of tumors were all within 1 cm3.

Mouse blastocyst collection, cell injection, and embryo transfer

The experimental use of mice was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Westlake University, Hangzhou, China (AP#24033–PDQ). Female ICR mice (4–6 weeks old) were super ovulated by intraperitoneal administration of 5 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin. After 48 h, they were injected with 5 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and then mated with male ICR mice. The female mice were checked for the vaginal plug the following morning. Plugged females were sacrificed at E3.5 after hCG injection for the collection of blastocysts, which were cultured in KSOM (Millipore, MR-106-D) medium until cell injection. Myh9 KO mESCs were dissociated into single cell suspension, and 10 to 12 cells were injected into mouse blastocysts. After injection, mouse blastocysts were cultured in micro drops of KSOM medium at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in air for 1 to 2 h. 14 to 16 blastocysts were transplanted into the uterus of 2.5 dpc pseudo pregnant ICR mice (10 to 16 weeks old). The chimeric mice were checked after birth by the coat color.

Statistical information

Statistical analysis was done using Prism v8.3.0 and R software v4.0.5. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance between two groups. P < 0.05 is considered to indicate a statistically significant value, * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No specific randomization or blinding protocols were used.

Results

Myh9 is required for maintaining the compact morphology of mESCs

Ever since its derivation in the early 1980s, mESCs are readily recognized under the microscope as rounded and compacted colonies (Fig. 1A). This quintessential morphology has also served as a defining feature of mESCs and by extension denoting pluripotency. The link between morphology and function of mESCs is well known, but not well understood molecularly. To probe this link, we hypothesize that members of cytoskeleton network are critical in maintaining mESC morphology.

Fig. 1.

Myh9 is required for maintaining the compact morphology of mESCs. A Typical morphology of wildtype mESCs colonies. Scale bar, 50 μm. B Myh9 knockout strategy and genotype sequencing results. The mouse Myh9 gene is located on chromosome 15 and contains 41 exons. A single guide RNA (sgMyh9) was designed targeting exon 6. Following Cas9-mediated cleavage and subsequent screening, several cell clones were obtained by single-cell picking. Sanger sequencing identified two distinct mutations: one exhibited a single-base deletion near the cleavage (Myh9KO1), while the other exhibited a single-base insertion (Myh9KO2). These mutations are predicted to generate truncated mutant proteins of 217 and 229 amino acids, respectively, which correspond to only a portion of the head domain of the wildtype NMIIA. C Western blot analysis of MYH9 protein expression levels in 2 WT mESCs cell lines and 3 Myh9 knockout mESCs cell lines. GAPDH was used as loading control. D Representative morphology of Myh9−/− mESCs. Right panel shows the enlarged images. Scale bar, 50 μm. E Representative morphology of Myh9−/− mESCs overexpressed the control vector, full-length mouse MYH9 (mMYH9), human MYH9 (hMYH9), the N-terminal head domain of mouse MYH9 (mMYH9N) or the C-terminal tail domain of mouse MYH9 (mMYH9C). Scale bar, 250 μm.

To test this hypothesis, we have profiled the expression of these components during early embryonic development and identified Myh9 which encodes the heavy chain of non-muscle myosin IIA or NMIIA as a candidate, as it accumulates and reaches a relatively high level at blastocyst stage and its role in regulating cytoskeleton function (Additional file 1: Fig. S1A)[17]. We proceeded to design a knockout strategy for Myh9 in mESCs by CRISPR-Cas9 and a guide RNA targeting its 6th exon to produce a frameshift mutation, resulting in an approximately 220 amino acids truncated protein (Fig. 1B).

We performed the gene editing experiments as previously described [18] and identified multiple cell lines that carry the intended mutation (Fig. 1B). We further confirmed the knockout cell lines with an antibody specifically binds to C-terminus of NMIIA heavy chain by western blot (Fig. 1C), and further confirmed by immunofluorescence (Additional file 1: Fig. S2A).

Mice carrying Myh9 knockout are embryonic lethal around E6.5, primarily due to defects in cell–cell adhesion [14]. Consistent with this phenotype in vivo, we show that Myh9 KO mESCs flatten into an EpiSC type of morphology (Fig. 1D), which was no longer in round dome-like shape with clear border, instead, the cells became flat, and could grow in monolayer or clusters with more protrusions. This morphology represents the primed pluripotency, suggesting that Myh9 is responsible for maintaining the naïve morphology for mESCs. On the other hand, Myh9 KO mESCs had similar proliferation rate (Additional file 1: Fig. S2B) and cell cycles (Fig. S2C) as wild type mESCs, suggesting a similar cellular character as naïve mESCs.

Moreover, this flattened morphology remained when cultured in serum medium with 2i/LIF (Additional file 1: Fig. S3A) or on feeder cells (Additional file 1: Fig. S3B), and kept stable for over 30 passages (Additional file 1: Fig. S3C). This morphological shift seems to be independent of genetic backgrounds as both 129/Sv and C57BL/6 J mESCs lines behave similarly (Additional file 1: Fig. S3D).

Phenotype rescue of Myh9 KO by mouse and human genes

To rule out any additional unintended alteration due to CRISPR editing, we re-introduced Myh9 genes from both mouse and human into Myh9 KO mESCs. We show that both genes rescued the phenotype efficiently (Fig. 1E). In contrast, neither the head domain (N-terminus, Fig. 1A) nor tail domain (C-terminus, Fig. 1A) alone rescued the phenotype under identical conditions (Fig. 1E). These data suggest that Myh9 KO mESCs reflect the function of NMIIA protein.

Inhibition of ROCKs phenocopies Myh9 KO in WT mESCs

The Myh9 encoded protein, NMIIA heavy chain, is 1960 amino acids residue long, organized into head (N) and tail (C) domains. The monomeric form of NMIIA is folded as an inactive form 10S and must be phosphorylated by more than a dozen kinases, including Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK), before it self-assembles into filaments [11, 19]. Meanwhile, the NMIIA bipolar filaments bind to actin and the ATPase activity of its head domain enables a conformational change that moves actin filaments [11]. We hypothesized that modulating NMIIA activity dynamics pharmacologically can recapitulate Myh9 KO in wild type mESCs. To this end, we selected three such inhibitors for testing, including Y27632 (ROCKi), Thiazovivin (ROCKi), or selective inhibitor of ATPase activity of myosin II, Blebbistatin. As shown in Fig. S4A (see Additional file 1), wild type mESCs underwent similar changes on colony morphology as Myh9 KO ones, consistent with previously described [13, 20]. And these phenotypes could be recovered by withdraw the inhibitors (Additional file 1: Fig. S4B).

Myh9 KO mESCs have similar transcriptomic profile as WT mESCs

Despite the morphological changes associated with Myh9 knockout or inhibitor treatments, we noticed that OCT4 level as indicated by GFP signals in Fig. 1D, E and S4 remained unchanged, suggesting that naïve pluripotent gene regulatory network remains intact. Indeed, the expression levels of the core transcription factor OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, and KLF4 of pluripotent state were comparable between Myh9 KO and WT mESCs as tested by western blot (Fig. 2A) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 2B). Monolayer-grown ESCs maintained an epithelial-like state, as confirmed by the expression of E-cadherin at the cell–cell boundaries (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Myh9 KO mESCs have similar transcriptomic profile as WT mESCs. A Western blot analysis of MYH9, NANOG, OCT4, SOX2 and KLF4 protein expression levels in 2 WT cell lines and 2 Myh9−/− cell lines. GAPDH was used as loading control. B Immunostaining of pluripotent marker NANOG and epithelial marker E-cadherin in WT and Myh9−/− cell lines. Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. C Gene expression profiles of WT and Myh9−/− mESCs as determined by RNA sequencing. Myh9 knockout has minimal impact on the expression of most naïve pluripotent markers, whereas Myh9 mRNA levels are significantly reduced

Besides, we used nuclear foci of H3K27me3 as inactive X chromosome marker to test if female Myh9 KO mESCs still maintain naïve identity [21–24]. We show that both X chromosomes in female Myh9 KO mESCs were active as WT ones, which were different with EpiSCs (Additional file 1: Fig. S5A). Meanwhile, when treated with 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), a glucose analog which competes with glucose for hexokinase in the first step of glycolysis and thereby inhibits glycolysis, naïve mouse embryonic stem cells can generate energy through oxidative phosphorylation and survive, whereas EpiSCs cannot, leading to extensive cell death [25]. Myh9 KO mESCs also survived from 2-DG treatment (Additional file 1: Fig. S6A, B), suggesting more alike with naïve ESCs. Also, the mitochondria in Myh9 KO mESCs were larger, round to oval, and spread-out in cytoplasm, which was the same as WT mESCs. In contrast, mitochondria in EpiSCs were smaller, more developed and elongated, and gathered around nucleus (Additional file 1: Fig. S6C).

These data indicate that Myh9 knockout do not change cell identity of mESCs, which are consistent with previous studies [20, 26, 27]. Furthermore, transcriptome RNA sequencing analysis revealed minimal gene expression changes following Myh9 deficiency (Fig. 2C). Along with western blot and immunofluorescence results, the markers of pluripotency, such as Pou5f1, Nanog, Esrrb, Klf2, Sall4, Sox2, Dppa4, Dppa2, Klf4, and Nr5a2, did not show significant differences between WT and Myh9 KO mESCs (Fig. 2C).

To rule out off-target effect of CRISPR-Cas9 system, we knocked down Myh9 with two short hairpin RNAs, and observed similar cellular morphology changes in mESCs (Additional file 1: Fig. S7A). qRT-PCR results showed that pluripotent markers, Nanog, Esrrb and Rex1, as well as epithelial marker, Cdh1, did not show significant differences between control group (Scramble) and Myh9 knockdown mESCs (Additional file 1: Fig. S7B), further confirmed our results in knockout cell lines.

In addition, we tested our hypothesis in human cells by inverting primed human ESC line H9 into naïve pluripotent state [16]. We used three different guide RNAs targeting exons 2, 5, and 6 of the human MYH9 gene, and implemented a knockout strategy analogous to that used in mouse ESCs. Knockout of MYH9 under naïve state resulted in a primed-like colony morphology (Additional file 1: Fig. S8A), yet these colonies continued to express human naïve pluripotent marker KLF17 (Additional file 1: Fig. S8B). These results indicate that naïve pluripotency of ESCs can be decoupled from the domed colony morphology is conserved between mice and human.

Myh9 KO mESCs have similar differentiation potential as WT mESCs

The apparent preservation of gene regulatory network, especially the expression of the core transcription factors for naïve pluripotency suggests that Myh9 KO cells should be capable of differentiating into all three germ layers as WT cells.

To test this, we further compared the differentiation properties between WT and KO cells by simply dropping out 2i/LIF in serum medium and N2B27 medium or by naïve to primed induction (Additional file 1: Fig. S9A). Although cell morphology changes differed during the three differentiation processes (Additional file 1: Fig. S9B), naïve pluripotency markers Nanog and Esrrb, endoderm marker Gata6, ectoderm markers Sox1 and Foxg1, primed pluripotency markers Fgf5 and Otx2, and germline marker Vasa, did not exhibit significant differences between WT cells and Myh9 deficiency ones (Additional file 1: Fig. S9C, D, E). To examine the trilineage potential of these non-domed cells, we performed the embryoid body differentiation experiment. It showed that both WT and Myh9 KO ESCs differentiated into similar spheres (Fig. 3A, B), and the markers of all three germ layers did not differ significantly between the two groups (Fig. 3C). Especially, the visceral endoderm markers, Gata4 and Apoe, were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 3C, Additional file 1: Fig. S9F), so as to other secreted factors from visceral endoderm (Additional file 1: Fig. S9F), which were previously reported as aberrant [14].

Fig. 3.

Myh9 KO mESCs have similar differentiation potential as WT mESCs. A Schematic diagram illustrating the generation of embryoid bodies. WT and Myh9−/− mESCs were cultured separately in about 200 hanging droplets without 2i/LIF for 3 days. All embryoid bodies were then collected for total RNA extraction and subsequent qRT-PCR analysis. B Representative morphologies of embryoid bodies derived from WT and Myh9−/− mESCs. Images in the left and right panels were acquired using different objective lenses. Scale bar, 250 μm. C Relative mRNA expression levels of endoderm markers (Gata4, Gata6, and Sox17), mesoderm markers (T and Mixl1), and ectoderm markers (Fgf5, Nestin, and Pax6) in WT and Myh9−/− embryoid bodies were assessed by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis was performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. D H&E staining of teratomas formed by WT and Myh9−/− mESCs. The images are representative of 5 independent teratomas. Scale bar, 50 μm. E Chimeric mice were generated by injecting Myh9−/− mESCs carrying an Oct4-GFP reporter into ICM of ICR blastocysts. Black coat color originated from the Oct4-GFP transgenic ESCs, whereas white coat color was derived from the ICM of the host ICR mice.

We also conducted neural stem cell differentiation (Additional file 1: Fig. S10A), and observed that Myh9 KO mESCs exhibited morphological changes similar to wildtype cells, albeit with significantly slower spreading kinetics. (Additional file 1: Fig. S10B). Consistently, expression of ectoderm and neuronal markers, Sox1, Nestin, Pax6, Tubb3, and Vmat2, were similar between the two groups at Day5 (in neurospheres), but lower in Myh9 deficiency group at Day10 (in NSCs) (Additional file 1: Fig. S10C). These results indicate that the non-domed ESCs retain neural ectodermal differentiation potential, although NMIIA deficiency causes a moderate delay during neuronal maturation.

Moreover, we injected mESCs of WT and Myh9−/− into NCG mice separately to test if both could form teratomas. 17 days after injection, teratomas were collected and weighed before fixation. The weight of the teratomas showed little difference between WT and KO groups (Additional file 1: Fig. S11A). And the structure of three germ layers could be readily identified in both groups after hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, we successfully generated chimeric mice by injected Oct4-GFP Myh9−/− mESCs into ICR mouse blastocysts (Fig. 3E). These results show that the flattened mESCs keep its potency to differentiate into multiple cell types.

Discussion

Cells adapt and optimize their morphology to suit their specific functions, and in turn, their morphology also influences and determines those functions. The mechanism underlying the maintenance of dome-like colony morphology with tightly packed cells in naïve pluripotent stem cells remains unclear. In this study, we generated monolayer-cultured pluripotent stem cells with naïve pluripotency through inhibit the function of NMIIA in mouse ESCs. The three-dimensional colonies of mouse ESCs is considered to result from the adhesive force for ESC-ESC binding being stronger than that for ESC-feeder binding [28]. The cadherin-catenin complexes present in adherens junctions and desmosomes contribute predominantly to the formation of compact colonies in mouse ESCs [27–30]. We observed that E-cadherin remains strongly localized at the cell–cell junctions in our flattened stem cell lines, suggesting these monolayer cells maintain an epithelial state with robust intercellular adhesion. Additionally, the contractile force generated by the three-dimensional supracellular actomyosin cortex beneath the cell membrane is also required for mESC colony integrity, and NMIIA-mediated contractility is essential for organization of this cortex [9]. Suppression of NMIIA leads to actin depolymerization and increase in cell spreading area [31–34]. Therefore, colony morphology in cultured cells is determined by at least three mechanical forces: cell–cell adhesion, cellsubstrate adhesion, and cortical membrane tension regulated by the contractile cortex. In our work, the most pronounced effect of Myh9 deletion was a substantial reduction in cortical tension in mESCs, which we attribute to the disruption of the actomyosin cortex. This loss of tension caused a morphological shift from domed colonies to a confluent, monolayer state where cell–cell junctions are maintained.

The differentiation of naïve ESCs is consistently accompanied by morphological changes in both individual cells and colonies. During early differentiation, a reduction in membrane tension activates ERK signaling, which subsequently induces exit from the naïve pluripotency [35]. And this decreased membrane tension is due to the release of plasma membrane from the underlying actin cortex, inhibiting this detachment enables ESCs to maintain their naïve pluripotent identity [36]. Moreover, by preventing cell spreading, ESCs can be maintained in an undifferentiated state [37]. Consequently, current quality assessment criteria for naïve pluripotent stem cells include compact, dome-shaped colony morphology as a key indicator. However, these investigations are based on differentiation systems, which cannot directly elucidate the role of colony morphology in naïve pluripotency maintenance during routine in vitro culture. Previous studies have demonstrated that disruption of colony morphology by cadherin-catenin complexes triggers exit from the naïve pluripotent states [9, 27]. Notably, these studies employed a restricted set of pluripotency markers rather than conducting a comprehensive assessment of differentiation potential. By comparing NMIIA-deficient mESCs with naïve and primed pluripotent stem cells in terms of cell proliferation rate, cell cycle, gene expression profiles, active X chromosome status, metabolism pathway, and mitochondrial morphology, we found that the deficient cells resemble naïve pluripotent stem cells in all these aspects, indicating that the morphological changes caused by the loss of NMIIA do not alter the fundamental cellular characteristics. This suggests that various molecules influencing the colony morphology of mESCs vary in their significance for maintaining naïve pluripotency. Screening for additional proteins that produce phenotypes similar to the loss of NMIIA may further reveal that dome-like colony morphology is not essential for maintenance of naïve pluripotency.

The differences between naïve and primed pluripotency are not limited to the embryonic developmental days, colony morphology, the enhancer of Pou5f1, gene expression profiles, X chromosome activation state, metabolism pathway, and mitochondria morphology [24, 25, 38]. It is frequently addressed that although both of them have the potential to differentiate into all of the germ layers, primed pluripotent stem cells could not colonize the pre-implantation embryos to form adult chimeras and transmit to the germline [24]. However, this is not attributed to the colony morphology per se, because inhibiting apoptosis in primed pluripotent stem cells is sufficient to enable their contribution to chimeric embryos [39, 40]. We therefore propose that relying solely on colony morphology is an inadequate and incomplete criterion for assessing the differentiation status or pluripotency of stem cells. Although the NMIIA plays essential roles in cell morphology, migration, adhesion, and mechanotransduction during embryo development and physiological activities, and completely depletion of Myh9 is embryonic lethality [14, 41], these specific functions are not the primary focus of this investigation.

Conclusions

In a word, the compact and domed morphology and naïve pluripotency of ESCs could be independent of one another. This underscores that morphological evaluation alone is inadequate for evaluating stem cell pluripotency, and molecular characterization and functional validation remain indispensable for rigorous pluripotency assessment in vitro. Future works are supposed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which colony morphology regulates cell fate transition to facilitate the optimization of in vitro stem cells culture, and provide deeper insights into cell fate plasticity during early embryonic development and the general principles of lineage commitment.

Supplementary Information

Additional file1: Figure S1 Expression of Myh9 during preimplantation development of mouse embryos. A Analysis of Myh9 mRNA levels in mouse preimplantation embryos using published single-cell RNA sequencing data [17]. Each dot represents an individual cell. Figure S2 Knockout of Myh9 does not affect growth performance of mESCs. A Immunostaining of MYH9 in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Cell viability analysis of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs was assessed by CCK-8 assay. Absorbance at 450 nm is positively correlated with cell number. The data represent mean ± SD from 20 independent replicates. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test for each time point. n.s., no significance. **, P < 0.01. ***, P < 0.001. C Cell cycle analysis of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs. The data represent mean ± SD from 3 independent replicates. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. Figure S3 Colony morphology of mESCs under different conditions A Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs in mES + 2i/LIF medium. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs on feeders. Scale bar, 250 μm. C Representative morphology of Myh9-/- mESCs after 15 and 30 passages. Scale bar, 250 μm. D Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs in 129/Sv (129) and C57BL/6J (C57) strains. Scale bar, 250 μm. Figure S4 Inhibition of ROCKs phenocopies Myh9 KO in WT mESCs. A Representative morphology of WT mESCs in mES + 2i/LIF medium with DMSO (1:2000), Y27632 (5 μM), Thiazovivin (5 μM) and Blebbistain (5 μM) for 48 h. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Representative morphology of WT mESCs in (A) after drop out the inhibitors. Scale bar, 250 μm. Figure S5 Both X chromosomes are active in Myh9 KO ESCs. A Immunostaining of H3K27me3 in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs, as well as in WT EpiSCs. Red arrows indicate H3K27me3 foci. Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm. Figure S6 Metabolic pathway of Myh9 KO ESCs. A Representative image of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs, as well as WT EpiSCs after 24 h treatment with 50 mM 2-DG. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Relative cell counts after 24 h treatment with 50 mM 2-DG. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. ***, P < 0.001. C Mitochondria morphology stained by MitoTracker in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs, as well as WT EpiSCs. Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. Figure S7 Knockdown of Myh9 does not affect naïve pluripotent gene regulatory network. A Representative morphology of control group (Scramble) and Myh9 Knockdown groups (shMyh9-1 and shMyh9-2). Scale bar, 250 μm. B Relative mRNA expression levels of Myh9, Nanog, Esrrb, Rex1, and Cdh1 were assessed by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. *, P < 0.05. Figure S8 Knockout of MYH9 in human naïve pluripotent stem cells. A Representative morphology of human induced naïve pluripotent stem cells in control group (NT) and MYH9 KO groups (sgMYH9-1, sgMYH9-2, and sgMYH9-3). MYH9 knockout was conducted by Cas9 protein and three different guide RNAs separately to introduce frame shift mutations. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Immunostaining of MYH9 and KLF17 in control group (NT), MYH9 KO group (sgMYH9), and primed human ESCs (H9). Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm. Figure S9 Knockout of Myh9 does not affect differentiation potency of mESCs. A Schematic diagram illustrating the 3 differentiation methods: withdrawal of 2i/LIF in mES medium containing fetal bovine serum (FBS) and in N2B27 medium (N2B27), as well as differentiation from naïve to primed state using bFGF, Activin A, and XAV939 (FAX). B Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs during the differentiation processes in (A). Scale bar, 250 μm. C Relative mRNA expression levels of Nanog, Gata6, Fgf5, Otx2 and Vasa in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs following differentiation with FBS for 24 h, as determined by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. D Relative mRNA expression levels of Nanog, Otx2, Sox1 and Foxg1 in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs following differentiation with N2B27 for 24 h, as determined by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. E Relative mRNA expression levels of Nanog, Esrrb, Fgf5, and Otx2 in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs after naïve to primed differentiation, as well as in EpiSCs, as determined by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. F Relative mRNA expression levels of Apoe, Afp, Apoa1, Ttr and Rbp1 in WT and Myh9-/- embryoid bodies were assessed by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. Figure S10 Knockout of Myh9 affects neural stem cells differentiation. A Schematic diagram illustrating the neural stem cells (NSCs) differentiation methods. WT and Myh9-/- mESCs were differentiated by first withdrawing 2i/LIF for two days, then culturing in low-adhesive 96-well plates with NDEF medium for three days to form neurospheres. The resulting neurospheres were subsequently transferred to gelatin-coated plates and maintained in NSC medium to facilitate NSCs expansion and spreading. B Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs during differentiation, at days 2, 5, and 9. Scale bar, 250 μm. C. Relative mRNA expression levels of Sox1, Nestin, Pax6, Tubb3, Vmat2, Nanog, and Rex1 in WT and Myh9-/- cells at days 0, 5, and 10, as well as in mouse brain tissue by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. *, P < 0.05. **, P < 0.01. Figure S11 Myh9 knockout does not impair teratoma formation by mESCs. A Weight of the teratomas formed by WT and Myh9-/- mESCs. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents a teratoma. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the members of Pei Lab for their helpful discussion and valuable feedback. We also thank faculty members at the Biomedical Research Core Facilities and Laboratory Animal Resource Center of Westlake University for assistance. This study was also supported in part by the InnoHK initiative of the Innovation and Technology Commission of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government.

Abbreviations

- mESCs

Mouse embryonic stem cells

- LIF

Leukemia inhibitory factor

- ESCs

Embryonic stem cells

- NM IIA

Non-muscle myosin IIA

- ICM

Inner cell mass

- TE

Trophectoderm

- WT

Wild type

- KO

Knock out

- ROCK

Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase

- PSCs

Pluripotent stem cells

Author contributions

D.P., J.K. and Y.Fan conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. J.K. and Y.Fan designed the project. Y.Fan performed most of the experiments and result analyses. J.K. performed the bioinformatic analysis. Y.Fan, X.W., Z.Z., and T.H. performed the animal experiments. W.L., Z.L., Z.M., Y.Fu, P.L. assisted in cell culture and differentiation assays. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92068201, 32300639), the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang (2024SSYS0034).

Data availability

RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession number GSE294784.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Pengli Li, Email: pengli.li@hkisi.org.hk.

Junqi Kuang, Email: kuangjunqi@weatlake.edu.cn.

Duanqing Pei, Email: peiduanqing@westlake.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292(5819):154–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(12):7634–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gough NM, Williams RL, Hilton DJ, Pease S, Willson TA, Stahl J, et al. LIF: a molecule with divergent actions on myeloid leukaemic cells and embryonic stem cells. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1989;1(4):281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koopman P, Cotton RGH. A factor produced by feeder cells which inhibits embryonal carcinoma cell differentiation - characterization and partial purification. Exp Cell Res. 1984;154(1):233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ying QL, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453(7194):519–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hackett JA, Surani MA. Regulatory principles of pluripotency: from the ground state up. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(4):416–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gafni O, Weinberger L, Mansour AA, Manor YS, Chomsky E, Ben-Yosef D, et al. Derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2013;504(7479):282–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware CB, Nelson AM, Mecham B, Hesson J, Zhou W, Jonlin EC, et al. Derivation of naive human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(12):4484–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du J, Fan Y, Guo Z, Wang Y, Zheng X, Huang C, et al. Compression generated by a 3D supracellular actomyosin cortex promotes embryonic stem cell colony growth and expression of nanog and Oct4. Cell Syst. 2019;9(2):214-20 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia S, Lim YB, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang S, Lim CT, et al. Nanoscale architecture of the cortical actin cytoskeleton in embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep. 2019;28(5):1251-67 e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Horwitz AR. Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(11):778–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabreges D, Corominas-Murtra B, Moghe P, Kickuth A, Ichikawa T, Iwatani C, et al. Temporal variability and cell mechanics control robustness in mammalian embryogenesis. Science. 2024;386(6718):eadh1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laeno AM, Tamashiro DA, Alarcon VB. Rho-associated kinase activity is required for proper morphogenesis of the inner cell mass in the mouse blastocyst. Biol Reprod. 2013;89(5):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conti MA, Even-Ram S, Liu C, Yamada KM, Adelstein RS. Defects in cell adhesion and the visceral endoderm following ablation of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain II-A in mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(40):41263–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong H, Lin B, Liu J, Lu R, Lin Z, Hang C, et al. SALL2 regulates neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells through Tuba1a. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(9):710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazid MA, Ward C, Luo Z, Liu C, Li Y, Lai Y, et al. Rolling back human pluripotent stem cells to an eight-cell embryo-like stage. Nature. 2022;605(7909):315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng Q, Ramsköld D, Reinius B, Sandberg R. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science. 2014;343(6167):193–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelson T, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343(6166):84–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung HS, Komatsu S, Ikebe M, Craig R. Head-head and head-tail interaction: a general mechanism for switching off myosin II activity in cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(8):3234–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harb N, Archer TK, Sato N. The rho-rock-myosin signaling axis determines cell-cell integrity of self-renewing pluripotent stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyon MF. Sex chromatin and gene action in the mammalian X-chromosome. Am J Hum Genet. 1962;14(2):135–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva J, Mak W, Zvetkova I, Appanah R, Nesterova TB, Webster Z, et al. Establishment of histone H3 methylation on the inactive X chromosome requires transient recruitment of Eed-Enx1 polycomb group complexes. Dev Cell. 2003;4(4):481–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Żylicz JJ, Bousard A, Žumer K, Dossin F, Mohammad E, da Rocha ST, et al. The implication of early chromatin changes in X chromosome inactivation. Cell. 2019;176(1–2):182-97.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou W, Choi M, Margineantu D, Margaretha L, Hesson J, Cavanaugh C, et al. HIF1α induced switch from bivalent to exclusively glycolytic metabolism during ESC-to-EpiSC/hESC transition. EMBO J. 2012;31(9):2103–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.David BG, Fujita H, Yasuda K, Okamoto K, Panina Y, Ichinose J, et al. Linking substrate and nucleus via actin cytoskeleton in pluripotency maintenance of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2019;41:101614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.del Valle I, Rudloff S, Carles A, Li Y, Liszewska E, Vogt R, et al. E-cadherin is required for the proper activation of the Lifr/Gp130 signaling pathway in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development. 2013;140(8):1684–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blancas AA, Chen CS, Stolberg S, McCloskey KE. Adhesive forces in embryonic stem cell cultures. Cell Adhes Migr. 2011;5(6):472–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pieters T, van Roy F. Role of cell-cell adhesion complexes in embryonic stem cell biology. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 12):2603–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soncin F, Mohamet L, Eckardt D, Ritson S, Eastham AM, Bobola N, et al. Abrogation of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact in mouse embryonic stem cells results in reversible LIF-independent self-renewal. Stem Cells. 2009;27(9):2069–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wylie SR, Chantler PD. Separate but linked functions of conventional myosins modulate adhesion and neurite outgrowth. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(1):88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao L, Mori Y, Sun SX, Li Y. On the role of myosin-induced actin depolymerization during cell migration. Mol Biol Cell. 2023;34(6):ar62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai Y, Biais N, Giannone G, Tanase M, Jiang G, Hofman JM, et al. Nonmuscle myosin IIA-dependent force inhibits cell spreading and drives F-actin flow. Biophys J. 2006;91(10):3907–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Even-Ram S, Doyle AD, Conti MA, Matsumoto K, Adelstein RS, Yamada KM. Myosin IIA regulates cell motility and actomyosin-microtubule crosstalk. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(3):299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Belly H, Stubb A, Yanagida A, Labouesse C, Jones PH, Paluch EK, et al. Membrane tension gates ERK-mediated regulation of pluripotent cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(2):273-84 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergert M, Lembo S, Sharma S, Russo L, Milovanovic D, Gretarsson KH, et al. Cell surface mechanics gate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(2):209-16 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray P, Prewitz M, Hopp I, Wells N, Zhang H, Cooper A, et al. The self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells is regulated by cell-substratum adhesion and cell spreading. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(11):2698–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Disteche CM, Berletch JB. X-chromosome inactivation and escape. J Genet. 2015;94(4):591–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Li T, Cui T, Yu D, Liu C, Jiang L, et al. Human embryonic stem cells contribute to embryonic and extraembryonic lineages in mouse embryos upon inhibition of apoptosis. Cell Res. 2018;28(1):126–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang K, Zhu Y, Ma Y, Zhao B, Fan N, Li Y, et al. BMI1 enables interspecies chimerism with human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mhatre AN, Li Y, Bhatia N, Wang KH, Atkin G, Lalwani AK. Generation and characterization of mice with Myh9 deficiency. Neuromol Med. 2007;9(3):205–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file1: Figure S1 Expression of Myh9 during preimplantation development of mouse embryos. A Analysis of Myh9 mRNA levels in mouse preimplantation embryos using published single-cell RNA sequencing data [17]. Each dot represents an individual cell. Figure S2 Knockout of Myh9 does not affect growth performance of mESCs. A Immunostaining of MYH9 in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Cell viability analysis of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs was assessed by CCK-8 assay. Absorbance at 450 nm is positively correlated with cell number. The data represent mean ± SD from 20 independent replicates. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test for each time point. n.s., no significance. **, P < 0.01. ***, P < 0.001. C Cell cycle analysis of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs. The data represent mean ± SD from 3 independent replicates. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. Figure S3 Colony morphology of mESCs under different conditions A Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs in mES + 2i/LIF medium. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs on feeders. Scale bar, 250 μm. C Representative morphology of Myh9-/- mESCs after 15 and 30 passages. Scale bar, 250 μm. D Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs in 129/Sv (129) and C57BL/6J (C57) strains. Scale bar, 250 μm. Figure S4 Inhibition of ROCKs phenocopies Myh9 KO in WT mESCs. A Representative morphology of WT mESCs in mES + 2i/LIF medium with DMSO (1:2000), Y27632 (5 μM), Thiazovivin (5 μM) and Blebbistain (5 μM) for 48 h. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Representative morphology of WT mESCs in (A) after drop out the inhibitors. Scale bar, 250 μm. Figure S5 Both X chromosomes are active in Myh9 KO ESCs. A Immunostaining of H3K27me3 in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs, as well as in WT EpiSCs. Red arrows indicate H3K27me3 foci. Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm. Figure S6 Metabolic pathway of Myh9 KO ESCs. A Representative image of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs, as well as WT EpiSCs after 24 h treatment with 50 mM 2-DG. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Relative cell counts after 24 h treatment with 50 mM 2-DG. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. ***, P < 0.001. C Mitochondria morphology stained by MitoTracker in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs, as well as WT EpiSCs. Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. Figure S7 Knockdown of Myh9 does not affect naïve pluripotent gene regulatory network. A Representative morphology of control group (Scramble) and Myh9 Knockdown groups (shMyh9-1 and shMyh9-2). Scale bar, 250 μm. B Relative mRNA expression levels of Myh9, Nanog, Esrrb, Rex1, and Cdh1 were assessed by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. *, P < 0.05. Figure S8 Knockout of MYH9 in human naïve pluripotent stem cells. A Representative morphology of human induced naïve pluripotent stem cells in control group (NT) and MYH9 KO groups (sgMYH9-1, sgMYH9-2, and sgMYH9-3). MYH9 knockout was conducted by Cas9 protein and three different guide RNAs separately to introduce frame shift mutations. Scale bar, 250 μm. B Immunostaining of MYH9 and KLF17 in control group (NT), MYH9 KO group (sgMYH9), and primed human ESCs (H9). Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm. Figure S9 Knockout of Myh9 does not affect differentiation potency of mESCs. A Schematic diagram illustrating the 3 differentiation methods: withdrawal of 2i/LIF in mES medium containing fetal bovine serum (FBS) and in N2B27 medium (N2B27), as well as differentiation from naïve to primed state using bFGF, Activin A, and XAV939 (FAX). B Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs during the differentiation processes in (A). Scale bar, 250 μm. C Relative mRNA expression levels of Nanog, Gata6, Fgf5, Otx2 and Vasa in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs following differentiation with FBS for 24 h, as determined by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. D Relative mRNA expression levels of Nanog, Otx2, Sox1 and Foxg1 in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs following differentiation with N2B27 for 24 h, as determined by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. E Relative mRNA expression levels of Nanog, Esrrb, Fgf5, and Otx2 in WT and Myh9-/- mESCs after naïve to primed differentiation, as well as in EpiSCs, as determined by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. F Relative mRNA expression levels of Apoe, Afp, Apoa1, Ttr and Rbp1 in WT and Myh9-/- embryoid bodies were assessed by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. Figure S10 Knockout of Myh9 affects neural stem cells differentiation. A Schematic diagram illustrating the neural stem cells (NSCs) differentiation methods. WT and Myh9-/- mESCs were differentiated by first withdrawing 2i/LIF for two days, then culturing in low-adhesive 96-well plates with NDEF medium for three days to form neurospheres. The resulting neurospheres were subsequently transferred to gelatin-coated plates and maintained in NSC medium to facilitate NSCs expansion and spreading. B Representative morphology of WT and Myh9-/- mESCs during differentiation, at days 2, 5, and 9. Scale bar, 250 μm. C. Relative mRNA expression levels of Sox1, Nestin, Pax6, Tubb3, Vmat2, Nanog, and Rex1 in WT and Myh9-/- cells at days 0, 5, and 10, as well as in mouse brain tissue by qRT-PCR. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents an independent experiment. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance. *, P < 0.05. **, P < 0.01. Figure S11 Myh9 knockout does not impair teratoma formation by mESCs. A Weight of the teratomas formed by WT and Myh9-/- mESCs. The data represent mean ± SD, each dot represents a teratoma. Statistical analysis is performed with two-tailed, unpaired t test. n.s., no significance.

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession number GSE294784.