Abstract

Background

Postoperative head and neck cancer (HNC) patients frequently experience oral microbiome dysbiosis and bad prognosis outcomes due to surgical trauma and reduced oral function, which may exacerbate symptoms and impair recovery. This study investigates how two oral mouthwash interventions—normal saline (N) and Yikou gargle (Y)—influence the oral microbiome at critical postoperative time points and explores their prognostic implications.

Methods

Eighty HNC patients scheduled for surgery (30 requiring tracheostomy) were randomized into Group N or Group Y. Saliva samples were collected at baseline, post-operation, and pre-discharge. Using 16 S rRNA sequencing, we analyzed microbiome composition, compared community diversity, identified intervention-enriched taxa, and evaluated the clinical prognostic effects, such as dental issues.

Results

While both groups initially exhibited comparable microbiome diversity, Group Y demonstrated pronounced clustering distinct from the Group N. Streptococcus dominated both cohorts, but the Group Y exhibited reduced abundance of pathobionts, such as Haemophilus (LDA > 2, p < 0.05 ). Clinically, tracheostomy patients in Group Y reported reduced severity of dental complications (p = 0.019) and higher abundance of Abiotrophia (p = 0.003) compared to Group N counterparts.

Conclusion

Our study provides insights into the impact of oral mouthwash interventions on the oral microbiome dynamics of HNC patients and their potential implications for prognosis. Understanding the role of the oral microbiome in HNC may pave the way for innovative therapeutic strategies that target the oral microbiota to improve treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Oral mouthwash, Oral microbiota, Normal saline, Chlorhexidine.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is a significant global health concern, encompassing a diverse group of malignancies that affect multiple regions of the upper aerodigestive tract, including the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx [1, 2]. The incidence of HNC has been steadily rising, and it is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality [3]. Factors such as tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection contribute to its complex aetiology [4–7]. Despite advances in treatment, HNC prognosis remains challenging due to its aggressive nature and potential for recurrence [8, 9].

Emerging evidence has highlighted the intricate interactions between the host and the oral microbiome, which plays a crucial role in maintaining oral health and influencing systemic health [10–12]. The oral cavity serves as a reservoir for a diverse array of microorganisms, comprising bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea, and alternations in its microbial composition have been linked to the local inflammation, immune responses, and carcinogenic processes [13–16]. The development and treatment of head and neck cancer (HNC), including surgical interventions and chemotherapy, can significantly impact the oral microbiome and compromise oral and dental health [10, 17–19].

Oral healthcare has gained attention as a potential adjunct to HNC management [20]. Mouthwash intervention, a common oral hygiene practice, offer a unique opportunity to modulate oral microbiome and influence the prognosis [21, 22]. The modulation of the oral microbiome through mouthwash intervention could represent a novel approach to improve cancer outcomes by targeting the microbial dysbiosis associated with carcinogenesis [23–25]. However, the specific effects of mouthwash intervention on the oral microbiome and their implications for HNC patients’ prognosis remain to be elucidated.

Current studies have demonstrated that chlorhexidine (CHX), a widely used component in oral mouthwashes, effectively reduces the proliferation of bacterial species associated with periodontal disease [24, 26]. However, few studies investigated the effect of CHX)and other component on oral microbiome and prognosis in HNC patients.

Therefore, we conducted a longitudinal study comparing the impact of normal saline (Group N) and Yikou gargle, containing triclosan and CHX (Group Y) in 80 HNC patients, with saliva sampling at three pivotal stages: (A) baseline when the patients were first recruited, (B) post-operation after surgical intervention, and (C) before-discharge from hospital. Using 16 S rRNA sequencing, we analyzed microbiome dynamics, identified intervention-enriched taxa. Further, we also investigate the effect on clinical outcomes, such as dental complications. Our findings aim to redefine oral care protocols for HNC patients, emphasizing microbiome-driven strategies to enhance recovery and prognostication.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient recruitment

The study was designed as a prospective cohort study to investigate the dynamics of the oral microbiome in HNC patients undergoing oral mouthwash intervention. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, under the reference number 20,201,266. All participants provided written informed consent before their participation.

Consecutive adult patients diagnosed with HNC [27, 28] and scheduled for surgical intervention were recruited from West China Hospital. Inclusion criteria required patients to have histologically confirmed HNC, no prior history of HNC treatment, and the ability to provide informed consent.

Randomization scheme

The randomization protocol employed a numerical table-based method for random assignment [29], which was implemented after patients’ hospital admission and upon meeting pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following the sequence of the numerical table, a researcher determined whether patients were assigned to Group N or Group Y.

Mouthwash interventions and saliva sample collection

After patients were randomly assigned to two treatment groups: Group N and Group Y. The N group received standard normal saline (0.9% saline solution) mouthwash, while the Y group received Yikou gargle, containing triclosan (trichlorohydroxy diphenyl ether) (1.7 g/L–2.1 g/L) and chlorhexidine acetate (0.9 g/L–1.1 g/L), a commercially available product recognized for its oral health-promoting properties. The designated nurse assumed the responsibility of providing daily instructions to patients regarding the precise timing and methodology of oral care, including mouth rinsing. Mouthwash interventions were administered three times daily more than 2 min each time after patients’ admission to the hospital. It was noteworthy that both oral mouthwash solutions were indistinguishable in their external packaging. Participants refrained from eating for at least 30 min before collection. Saliva,, was collected as it naturally accumulated on the floor of the mouth and then expectorated into a specimen tube.

Oral saliva samples were collected approximately 3 mL in volume at three distinct time points using an established method [30, 31]. These samples were promptly stored at −80 °C until further processing. These timepoints included: baseline (a), signifying the period before the commencement of mouthwash treatment; post-operation (b), corresponding to one to two days after surgery; and before-discharge from hospital (c), representing the collection approximately ten days after surgical intervention. This timeline allowed for a comprehensive assessment of oral microbiome dynamics in response to the mouthwash treatments.

Phenotype assessment

Demographic and clinical information, along with symptom data, were meticulously gathered from the study participants. The assessment of symptoms was conducted using the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory-Head and Neck Module-Chinese version (MDASI-H&N-C) [32, 33]. This instrument has 22 items to assess the patient’s level of symptom distress in the past 24 h, 13 core items assess the severity of generic cancer related symptoms and 9 HNC specific items to rate the severity of symptoms associated with HNC, including dental issues such as swelling and pain in the teeth and gums. An 11-point Likert scale method was used in the scoring, ranging from “none” to “the worst” [34, 35].

DNA extraction and 16 S rRNA sequencing

DNA extraction from the oral saliva samples was performed using a commercial DNA extraction kit with magnetic beads (GenMagBio, Jiangsu, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) [36].

The V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16 S rRNA gene was amplified using primers targeting the conserved regions, 341 F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 805R (5′- GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) [37]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was carried out using the KAPA HiFi HotStart PCR Kit with dNTPs (Kapa Biosystems, Cape Town, South Africa). Following PCR amplification, the PCR products were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and quantified using a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The library quality was meticulously assessed via the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Subsequently, libraries were quantified using real-time PCR and pooled at equal concentrations. To enhance sequencing quality, PhiX (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was incorporated as a sequencing control. The prepared amplicons were then subjected to paired-end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform, utilizing PE250 chemistry. This sequencing process was conducted at Genetalks Biotechnology in Changsha, China.

Microbiome data preprocessing, taxonomic profiling

Raw sequence data were processed using Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME2) software [38]. The DADA2 pipeline was utilized for quality filtering, denoising, and removing chimeric sequences [39]. The resulting amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were taxonomically classified using the SILVA database (Release 132).

Microbiome data analysis

α diversity matrix, such as the Shannon index, was calculated to assess the richness of the oral microbiota within each sample. β diversity analysis was performed using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity to evaluate the overall differences in microbial community composition between samples using the vegan package (version 2.6–4.6) in R. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed on the sample pairwise Bray–Curtis dissimilarity measures derived from the relative abundances of the taxa. The permutational multivariate analysis of variance test was performed in vegan with 100 permutations. To identify microbial taxa that showed differential abundance between the Group N and Group Y group, Linear Discriminant Analysis effect size (LEfSe, Galaxy Version 1.0) analysis was performed with an LDA log score cut-off of 2 [40].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R programming language and appropriate packages. Differences in alpha diversity and relative abundance between groups and time points were evaluated using two-sided unpaired Mann–Whitney U tests or Kruskal–Wallis test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The plots were visualized using the ggplot2 package in R (version 4.2.1) and modified from EasyAmplicon [41, 42].

Results

Characteristics of patients

Between December 2021 and July 2022, a total of 85 patients diagnosed with HNC and scheduled for surgical intervention were included in this study. Upon admission, the study’s objectives were explained to the patients, and informed consent was obtained. Among the initially enrolled patients, three experienced post-operative xerostomia (dry mouth), and two patients did not undergo surgery, opting for early discharge, subsequently withdrawing from the study. Ultimately, a total of 80 patients were included in the analysis. The Group N (normal saline) consisted of 38 participants, while the Group Y (Yikou gargle) included 42 participants. The essential clinical information for both groups was summarized in the Table 1, incorporating 19 distinct types of head and neck cancers. Of these, 30 patients underwent tracheostomy, and their demographic and clinical information was also detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and clinical characteristics

| Demographic Characteristics | All Patients (n = 80) | Patients with Tracheotomy (n = 30) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal Saline (n = 38) |

Yikou (n = 42) |

P-value |

Normal Saline (n = 17) |

Yikou (n = 13) |

P-value | |||

|

Age (Years, Mean, SD) Gender [n (%)] Diagnosis [n (%)] Whether to place a gastric tube after surgery [n (%)] BMI (kg/m2, Mean, SD) Smoking history [n (%)] Alcohol history [n (%)] Combined hypertension [n (%)] Combined diabetes [n (%)] Preoperative chemoradiotherapy [n (%)] Pneumonia [n (%)] Wound infection [n (%)] |

Male Female Middle ear cancer External ear cancer Nasal malignancy Sinus malignancy Laryngo-carcinoma Hypopharyngeal cancer Oropharyngeal cancer Nasopharyngeal carcinoma Tongue base cancer Thyroid cancer Tracheal tumors Palate cancer Salivary gland cancer others Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No |

57.87 ± 14.15 5(13.16) 33 (86.84) 1 (2.63) 0 1 (2.63) 1 (2.63) 15 (39.47) 7 (18.42) 0 0 1 (2.63) 6 (15.79) 0 0 2 (5.26) 4 (10.53) 14 (36.84) 24 (63.16) 23.24 ± 3.20 24 (63.16) 14 (36.84) 24 (63.16) 14 (36.84) 9 (23.68) 29 (76.32) 6 (15.79) 32 (84.21) 2 (5.26) 36 (85.71) 3 (7.89) 35 (92.11) 3 (7.89) 35 (92.11) |

57.09 ± 13.19 6 (14.29) 36 (85.71) 0 1 (2.38) 0 1 (2.38) 20 (47.62) 6 (14.29) 1 (2.38) 1 (2.38) 0 6 (14.29) 1 (2.38) 1 (2.38) 1 (2.38) 3 (7.14) 18 (42.86) 24 (57.14) 24.44 ± 3.56 26 (61.90) 16 (38.10) 20 (52.38) 22 (47.62) 11 (26.19) 31 (73.81) 3 (7.14) 39 (92.86) 5 (11.90) 37 (88.10) 3 (7.14) 39 (92.86) 4 (9.52) 38 (90.48) |

0.772 0.084 0.581 0.583 0.137 0.908 0.163 0.796 0.222 0.294 0.899 0.797 |

62.53 ± 12.17 17 0 0 0 0 0 8 (47.0) 7 (41.2) 0 0 2 (11.8) 0 0 0 0 0 17 0 24.18 ± 3.32 12 (70.59) 5 (29.41) 12 (70.59) 5 (29.41) 12 (70.59) 5 (29.41) 16 (94.12) 1 (5.82) 5 (29.41) 12 (70.59) 16 (94.12) 1 (5.82) 3 (17.65) 14 (82.35) |

62.00 ± 10.90 13 0 0 0 0 0 8 (61.5) 4 (30.8) 1 (7.7) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 13 0 23.84 ± 3.44 10 (76.92) 3 (23.08) 8 (61.54) 5 (38.46) 11 (84.62) 2 (15.38) 12 (92.31) 1 (7.69) 2 (15.38) 11 (84.62) 12 (92.31) 1 (7.69) 2 (15.38) 11 (84.62) |

0.292 / 0.561 / 0.414 0.597 0.602 0.369 0.844 0.427 0.773 0.869 |

|

| Length of hospital stay | 10.97 ± 4.32 | 12.21 ± 8.58 | 0.424 | 11.56 ± 4.32 | 16.64 ± 9.92 | 0.073 | ||

|

histological type T N M Antibiotics Antihypertensives |

Squamous cell carcinoma Papillary carcinoma Others T1 T2 T3 T4 N0 N1 N2 N3 M0 M1 Cefmetazole Cefoperazone Cefazolin Ceftriaxone Sodium Piperacillin-tazobactam Calcium channel blockers Angiotensin II receptor Antagonists β1 receptor blockers Diuretics |

28 (73.68) 7 (18.42) 3 (7.89) 6 (15.79) 11 (28.95) 11 (28.95) 10 (26.31) 21 (55.26) 9 (23.68) 5 (13.16) 3 (7.89) 37 (97.37) 1 (2.63) 4 (10.53) 3 (7.89) 2 (5.26) 28 (73.68) 1 (2.63) 6 (15.79) 1 (2.63) 1 (2.63) 1 (2.63) |

32 (76.19) 6 (14.29) 4 (9.52) 14 (33.33) 6 (14.29) 11 (26.19) 11 (26.19) 25 (59.52) 7 (16.67) 9 (21.43) 1 (2.38) 41 (97.62) 1 (2.38) 2 (4.76) 4 (9.52) 6 (14.29) 30 (71.43) 0 7 (16.67) 2 (4.76) 1 (2.38) 1 (2.38) |

0.866 0.210 0.467 0.943 0.450 0.976 |

14 (82.35) 1 (5.88) 2 (11.76) 0 6 (35.29) 9 (52.94) 2 (11.76) 8 (47.06) 5 (29.41) 3 (17.65) 1 (5.88) 17 0 2 (11.76) 0 1 (5.88) 14 (82.35) 0 3 (17.65) 1 (5.88) 1 (5.88) 1 (5.88) |

13 0 0 0 4 (30.77) 7 (53.85) 2 (15.38) 8 (61.54) 1 (7.69) 4 (30.77) 0 13 0 0 0 0 12 (92.31) 1 (7.69) 2 (15.38) 0 0 0 |

0.279 0.942 0.343 / 0.297 0.659 |

|

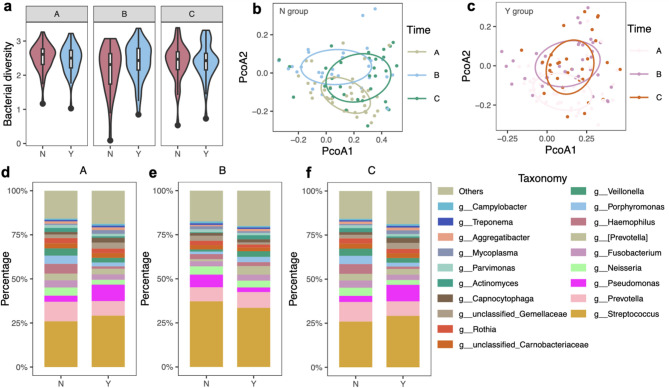

Our primary focus was to assess the impact of mouthwash intervention on oral microbiome diversity. We compared the α diversity (Shannon index) between Group N and Group Y, at different time points (Fig. 1a). Initially, both treatment groups exhibited similar oral microbiome diversity. However, after surgical resection of tumor, the Y group presented greater species diversity than the N group, albeit without reaching a statistical significance (B, post-operation after surgical intervention: Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p = 0.220, Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Oral microbiome diversity with mouthwash intervention. a Shannon index of the oral microbiome in two different mouthwash intervention groups at different time points. The horizontal bars within boxes represent medians. The tops and bottoms of boxes represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The upper and lower whiskers extend to data no more than 1.5× the interquartile range from the upper edge and lower edge of the box, respectively (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: A, baseline when the patients were first recruited: p = 0.468; B, post-operation after surgical intervention: p = 0.220; C, before-discharge from hospital: p = 0.832).b - c Unconstrained PCoA (for principal coordinates PCoA1 and PCoA2) with Bray–Curtis distance showing clustering according to timepoints (A, baseline when the patients were first recruited; B, post-operation after surgical intervention; C, before-discharge from hospital) in Group N (b) and Group Y (c). Ellipses covered 50% of the data for each intervention group (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: b: PCoA1: p = 0.067, PCoA2: p = 4.31e-06; c: PCoA1: p = 0.55, PCoA2: p = 2.88e-06).d - f Genus-level taxonomic distribution of the gut microbiome among intervention groups on average at different time points. N: normal saline, Y: yikou gargle; A: baseline, B: post-operation, C: before-discharge from hospital

In addition to α diversity, we used Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distance matrix to visualize the clustering patterns at different time points within the Group N and Group Y (permanova: p = 0.001, Fig. 1b-c). These patterns revealed shifts in oral microbiome composition throughout treatment, with the Group Y exhibiting more pronounced variation, especially after surgery. Detailed illustrations of the alternations in the oral microbiome composition during treatment provided significant insights into the dynamics of oral microbial communities (Figure S1a-d).

Oral mouthwash intervention influences oral microbiome dynamics

The investigation at the microbial composition revealed intriguing patterns when we examined genus-level taxonomic distributions (Fig. 1d-f). Both intervention groups shared common genera, including Streptococcus, Prevotella, Pseudomonas, Neisseria, Fusobacterium, [Prevotella], Haemophilus, Porphyromonas, and Veillonella emerging as principal constituents. Streptococcus, in particular, emerged as the dominant genus, representing the most abundant oral taxon in both groups. Additionally, we zoomed in on individual level genus distribution, providing a more detailed view of the oral microbiome taxonomic landscape (Figure S1e-g).

Further, to identify the different taxa in the two groups, we performed LEfSe analysis and identified several different bacteria in each group at different time points (Figure S2a-c). At the baseline, Group N and Group Y displayed only one significantly differential taxa Corynebacterium (Figure S2a). Corynebacterium was significantly more abundant in Group Y (LDA = 2.06, p = 0.03). The landscape underwent a profound transformation after the mouthwash treatments, where Group Y exhibited a heightened abundance of taxa including Carnobacteriaceae, Capnocytophaga, Desulfobulbus, Sphaerochaeta, Endomicrobia, Ralstonia and Dethiosulfovibrionaceae in comparison to Group N, immediately after surgery (Figure S2b and Fig. 2a). Following surgical recovery, Abiotrophia and other six genera were significantly enriched in Group N, while Group Y experienced a surge in Haemophilus and other six genera (Figure S2c and Fig. 2b). These findings highlighted the dynamic interplay between mouthwash interventions and specific microbial taxa.

Fig. 2.

Oral microbiome difference of two treatment groups. a - b Cladograms, generated from LEfSe, represent taxa enriched in oral microbiome between Group N (red) and Group Y (green) of post-operation(a) and before discharge from hospital (b). The central point represents the root of the tree (Bacteria), and each ring represents the next lower taxonomic level (phylum to species). Differences among classes were obtained by the Kruskal-Wallis test (p = 0.05)

Implications of oral healthcare on oral prognosis

To unravel the implications of mouthwash interventions after surgery, we assessed postoperative wound healing, pneumonia infection, pharyngeal leak, recurrence of cancer, gauged the quality of life, and dental issues via MDASI-H&N for head and neck cancer. A salient finding was the notably diminished severity of dental issues among patients Group Y compared to Group N (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p = 0.019, Fig. 3a) among tracheostomy patients at C time point (before-discharge from hospital).

Fig. 3.

The association between oral microbiota and oral healthcare. a Oral prognosis score after tracheotomy between two mouthwash intervention groups.b Shannon index of the oral microbiome from two intervention groups before discharge from hospital. The top and bottoms of boxes represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The upper and lower whiskers extend to data no more than 1.5x the interquartile range from the upper edge and lower edge of the box, respectively. c Beta-diversity analysis was presented as a two-dimensional plot based on PCoA. Ellipses covered 50% of the data for each intervention group. d LDA scores of the differentially abundant taxa in oral microbiome from two intervention groups (taxa with LDA score >2 and a significance of p < 0.05 are shown).e Boxplot with notch shows the relative abundance of Abiotrophia. Box represent the IQRs between the first and third quartiles, and the line inside the box represents the median. *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Wilcoxon rank-sum test

We also compared the α diversity between two groups. The Group N showed a higher median α diversity compared to the Group Y (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p = 0.25, Fig. 3b). The PCoA analysis unveiled distinctive clustering patterns (permanova, p = 0.009, Fig. 3c). The differences at A and B time points (A: baseline when the patients were first recruited, B: post-operation after surgical intervention) were subtle (Figure S3a-b). Additional insights were obtained through the identification of specific taxa exhibiting differential abundance between two groups at C time point (before discharge from hospital, Fig. 3d). As a result, Haemophilus emerged as the dominant genus in Group N, while Streptococcus, Capnocytophaga, Scardovia, Abiotrophia and TG5 exerted their prominence in Group Y. Of particular interest was the genus Abiotrophia, which manifested as significantly different between the Group N and Group Y before discharge from hospital (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: p = 0.003, Fig. 3e), despite parity at the first two time points (Figure S3). These results further underlined the role of mouthwash intervention in shaping the oral microbiome dynamics and prognosis.

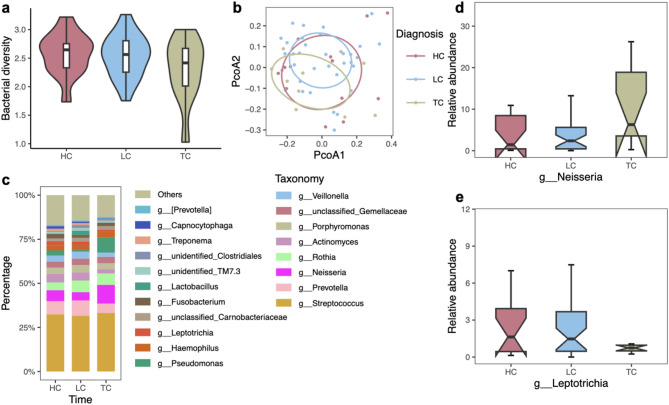

Oral microbiome signatures across distinct head and neck cancer types

Our study also explored the oral microbiome signatures associated with different types of HNC. Hypopharyngeal cancer (HC) displayed the highest median α diversity among the groups (Fig. 4a). Clear separations were observed among the HC, laryngeal cancer (LC), and thyroid cancer (TC) patients (Fig. 4b). Further, we examined the genus-level taxonomic distribution of the oral microbiome (Fig. 4c and Figure S4). Notably, our focus on the relative abundance of the genera Neisseria and Leptotrichia, as highlighted in the boxplots (Fig. 4d-e). The relative abundance of the genus Neisseria was found to be higher in TC patients, while Leptotrichia exhibited a decrease in abundance in TC patients.

Fig. 4.

Specific oral microbiota signatures of different head and neck cancer types. a Shannon index of the oral microbiome from three different cancer types. The top and bottoms of boxes represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The upper and lower whiskers extend to data no more than 1.5x the interquartile range from the upper edge and lower edge of the box, respectively. Kruskal–Wallis test, among three groups, p = 0.399. Mann–Whitney U test, HC vs TC, p = 0.186; LC vs TC, p = 0.298.b Beta-diversity of oral microbiota in three head and neck cancer types measured by unconstrained PCoA (for principal coordinates PCo1 and PCo2) with Bray–Curtis distance. Ellipses covered 50% of the data for each cancer group. Permanova, p = 0.723.c Genus-level taxonomic distribution of the oral microbiome among three head and neck cancer types on average.d – e Relative abundance ofNeisseria (d) and Leptotrichia (e) in three head and neck cancer types showed by boxplot. Boxes represent the IQRs between the first and third quartiles, and the line inside the box represents the median. Genus Neisseria: Kruskal–Wallis test, among three groups, p = 0.155. Mann–Whitney U test, HC vs TC, p = 0.208; LC vs TC, p = 0.050. Genus Leptotrichia: Kruskal–Wallis test, among three groups, p = 0.2621. Mann–Whitney U test, HC vs TC, p = 0.186; LC vs TC, p = 0.120. HC: n = 13; LC: n=35; TC: n = 11.

Discussion

Our study investigated the effects of mouthwash intervention on oral microbiome dynamics and its potential for dental protection. Specifically, Yikou gargle reduced the abundance of pathogenic Haemophilus and alleviated severity of dental issues. Our findings underscore the beneficial effect of Yikou gargle in promoting oral health.

Although α-diversity of microbiomes were comparable and did not change significantly between groups (p >0.05), β-diversity analyses revealed distinct clustering patterns in Group Y post-surgery, likely reflecting the rapid antimicrobial activity of the gargle [43, 44]. Over time, the abundance of pathogenic Haemophilus in Group Y was lower compared to Group N. These results further underlined the positive impact of Yikou mouthwash intervention in shaping the oral microbiome dynamics. Importantly, antibiotic regimens (e.g., cephalosporins) were consistent across groups, ruling out confounding effects and reinforcing direct role of Yikou gargle in microbiome modulation.

Critically, Group Y patients with tracheotomy demonstrated a reduction in the severity of postoperative dental complications, including swelling and pain in the teeth and gums. This improvement may be linked to an increase in the abundance of Abiotrophia, a genus of bacteria associated with oral health. While the role of Abiotrophia in oral health is not fully understood, current literature presents conflicting findings: some studies identify it as a potential risk factor for periodontal disease [45, 46], while others suggest it may serve as a biomarker for low caries risk [47]. The influence of Abiotrophia on oral health outcomes, particularly in the context of mouthwash use, warrants further investigation. Specifically, the interaction between mouthwash components, which can alter the oral microbiome, and the clinical symptoms experienced by patients, is complex and still not well-characterized. Understanding how mouthwash-induced changes in microbial composition influence the pathophysiology of dental complications in patients with tracheotomy could lead to more targeted treatments and improve patient outcomes.

Beyond intervention effects, we identified unique microbial signatures across HNC subtypes. In TC, lower α diversity, higher abundance of Neisseria and lower abundance of Leptotrichia have been observed. These findings suggest that microbiome profiling could refine diagnostic tools [48], consistent with existing literatures [49, 50]. Despite the constraint of a limited sample size, it was noteworthy that while the observed differences did not attain statistical significance, these findings underscored the potential implications of an association between the modified composition of these microbial genera and the presence of TC. As such, they provided a strong rationale for conducting further investigations into the roles of these genera in the etiology of TC. These analyses also underscored disparities in the relative abundance of these genera across HNC types, thereby suggesting plausible connections between specific oral microbiota and distinct malignancies.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, the small sample size and the single-center design may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, the use of antimicrobial agents in postoperative patients could influence the oral microbiota composition, introducing potential bias, even though there was no significant difference between two groups. These factors should be considered when interpreting our findings.

Conclusions

This study highlights the interplay between oral healthcare, the oral microbiome, and patient outcomes in HNC. We observed that mouthwash treatments transiently influence oral microbiome dynamics with potential associations with improved oral health post-surgery. Furthermore, distinct oral microbiota signatures across HNC types suggest a potential role in early screen strategies. Further studies with larger cohorts and multi-center validation are needed to further explore these dynamics and their implications for precision medicine in HNC.

Acknowledgements

We thank the all the participants of this study. We thank Chengdu Runxing Disinfectant for providing us with packaging for Yikou and Yikou products. We also thank DeepSeek for language editing.

Abbreviations

- HNC

Head and neck cancer

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- MDASI-H&N-C

MD Anderson Symptom Inventory-Head and Neck Module-Chinese version

- PCoA

Principal coordinate analysis

- LDA

Linear Discriminant Analysis

- HC

Hypopharyngeal cancer

- LC

laryngeal cancer

- TC

Thyroid cancer

Authors’ contributions

The authors (HZ, JW, WK, HY) designed the study and wrote the manuscript. The authors (YQ, XJ, XY, XD, RY) performed the study and collected the data.The authors (HZ, WK) analysis the data. All authors (XJ, YQ, JW, WK, RY, XY, XD, HY, HZ) read and approved the final version for submission.Xiaoqin Ji and Yixin Qiao contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This study is supported by Key Research and Development Projects of Sichuan Science and Technology Department (2021YFS0156) and China Scholarship Council (CSC 202108510037). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive under BioProject ID PRJNA1078109, sample accession SRR28035896-SRR28036043. The publicly available link for the data is listed below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1078109.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, under the reference number 20201266. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as with all currently applicable laws and regulations of the country where the study was conducted. Written informed consent document was obtained from all subjects during the screening period.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaoqin Ji and Yixin Qiao contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Chow LQ. Head and neck cancer. New Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):60–72. 10.1097/00001622-199206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui VWY, Bauman JE, Grandis JR. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):92. 10.1038/s41572-020-00224-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gormley M, Creaney G, Schache A, Ingarfield K, Conway DI. Reviewing the epidemiology of head and neck cancer: definitions, trends and risk factors. Br Dent J. 2022;233(9):780–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, Saginala K, Barsouk A. Epidemiology. Risk factors, and prevention of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Med Sci. 2023;11(2):42. 10.3390/medsci11020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang F, Yin Y, Li P, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus type-18 in head and neck cancer among the Chinese population. Medicine. 2019. 10.1097/MD.0000000000014551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferraguti G, Terracina S, Petrella C, et al. Alcohol and head and neck cancer: updates on the role of oxidative stress, genetic, epigenetics, oral microbiota, antioxidants, and alkylating agents. Antioxidants. 2022;11(1):145. 10.3390/antiox11010145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batistella EÂ, Gondak R, Rivero ERC, et al. Comparison of tobacco and alcohol consumption in young and older patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(12):6855–69. 10.1007/s00784-022-04719-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaidar-Person O, Gil Z, Billan S. Precision medicine in head and neck cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2018;40:13–6. 10.1016/j.drup.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melariri H, Els T, Oyedele O, et al. Prevalence of locoregional recurrence and survival post-treatment of head and neck cancers in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;59:101964. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes RB, Ahn J, Fan X, et al. Association of oral microbiome with risk for incident head and neck squamous cell cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):358–65. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng X, Cheng L, You Y, et al. Oral microbiota in human systematic diseases. Int J Oral Sci. 2022;14(1):1–11. 10.1038/s41368-022-00163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Börnigen D, Ren B, Pickard R, et al. Alterations in oral bacterial communities are associated with risk factors for oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–13. 10.1038/s41598-017-17795-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuominen H, Rautava J. Oral microbiota and cancer development. Pathobiology. 2021;88(2):116–26. 10.1159/000510979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atarashi K, Suda W, Luo C, et al. Ectopic colonization of oral bacteria in the intestine drives TH1 cell induction and inflammation. Science. 2017;358(6361):359–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun J, Tang Q, Yu S, et al. Role of the oral microbiota in cancer evolution and progression. Cancer Med. 2020;9(17):6306–21. 10.1002/cam4.3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuganbaev T, Yoshida K, Honda K. The effects of oral microbiota on health. Sci (80-). 2022;376(6596):934–6. 10.1126/science.abn1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samim F, Epstein JB, Zumsteg ZS, Ho AS, Barasch A. Oral and dental health in head and neck cancer survivors. Cancers Head Neck. 2016;1(1):1–7. 10.1186/s41199-016-0015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kageyama S, Nagao Y, Ma J, et al. Compositional shift of oral microbiota following surgical resection of tongue cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10(November):1–7. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.600884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong J, Li W, Wang Q, et al. Relationships between oral microecosystem and respiratory diseases. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;8(January):1–17. 10.3389/fmolb.2021.718222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sio TT, Le-Rademacher JG, Leenstra JL, et al. Effect of doxepin mouthwash or diphenhydramine-lidocaine-antacid mouthwash vs placebo on radiotherapy-related oral mucositis pain: the alliance A221304 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(15):1481–90. 10.1001/jama.2019.3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Wang X, Li H, Ni C, Du Z, Yan F. Human oral microbiota and its modulation for oral health. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;99(September 2017):883–93. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel A, Patel S, Patel P, Tanavde V. Saliva based liquid biopsies in head and neck cancer: how Far are we from the clinic? Front Oncol. 2022;12(March):1–13. 10.3389/fonc.2022.828434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shitozawa Y, Haro K, Ogawa M, Miyawaki A, Saito M, Fukuda K. Differences in the microbiota of oral rinse, lesion, and normal site samples from patients with mucosal abnormalities on the tongue. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1–10. 10.1038/s41598-022-21031-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bescos R, Ashworth A, Cutler C, et al. Effects of chlorhexidine mouthwash on the oral Microbiome. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–8. 10.1038/s41598-020-61912-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khurshid Z, Zafar MS, Khan RS, Najeeb S, Slowey PD, Rehman IU. Role of salivary biomarkers in oral cancer detection. Volume 86. Elsevier Ltd; 2018. 10.1016/bs.acc.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.James P, Worthington HV, Parnell C, et al. Chlorhexidine mouthrinse as an adjunctive treatment for gingival health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017. 10.1002/14651858.CD008676.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, et al. Head and neck cancers—major changes in the American joint committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):122–37. 10.3322/caac.21389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfister DG, Spencer S, Adelstein D, et al. Head and neck cancers, version 2.2020. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2020;18(7):873–98. 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suresh K. An overview of randomization techniques: an unbiased assessment of outcome in clinical research. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2011;4(1):8–11. 10.4103/0974-1208.82352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.Navazesh M. Methods for collecting saliva. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan X, Peters BA, Min D, Ahn J, Hayes RB. Comparison of the oral Microbiome in mouthwash and whole saliva samples. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):1–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Chambers MS, et al. The M. D. Anderson symptom inventory-head and neck module, a patient-reported outcome instrument, accurately predicts the severity of radiation-induced mucositis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(5):1355–61. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ou M, Wang G, Yan Y, Chen H, Xu X. Perioperative symptom burden and its influencing factors in patients with oral cancer: a longitudinal study. Asia-Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2022;9(8):100073. 10.1016/j.apjon.2022.100073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Zyi, Feng X, qiong, Fu MR, Yu R, Zhao H. ling. Symptom patterns, physical function and quality of life among head and neck cancer patients prior to and after surgical treatment: A prospective study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;46:101770. 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101770. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Wen L, Cui Y, Chen X, Han C, Bai X. Psychosocial adjustment and its influencing factors among head and neck cancer survivors after radiotherapy: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;63(210):102274. 10.1016/j.ejon.2023.102274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao Y, Peng K, Bai D, et al. The microbiome protocols ebook initiative: building a bridge to microbiome research. iMeta. 2024;e182. 10.1002/imt2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herlemann DPR, Labrenz M, Jürgens K, Bertilsson S, Waniek JJ, Andersson AF. Transitions in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. ISME J. 2011;5(10):1571–9. 10.1038/ismej.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):852–7. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13(7):581–3. 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu YX, Chen L, Ma T, Li X, Chen L, Lu H. EasyAmplicon: an easy - to ‐ use, open ‐ source, reproducible, and community ‐ based pipeline for amplicon data analysis in microbiome research. iMeta. 2023;2(1):e83. 10.1002/imt2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yousuf S. Unveiling microbial communities with easyamplicon: a user-centric guide to perform amplicon sequencing data analysis. iMetaOmics. 2024;e42. 10.1002/imo2.42. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang CC, Lee WT, Hsiao JR, et al. Oral hygiene and the overall survival of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2019;8(4):1854–64. 10.1002/cam4.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sedghi L, DiMassa V, Harrington A, Lynch SV, Kapila YL. The oral microbiome: role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 2021;87(1):107–31. 10.1111/prd.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X, Yu C, Zhang B, et al. The recovery of the microbial community after plaque removal depends on periodontal health status. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2023;9(1):75. 10.1038/s41522-023-00441-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mikkelsen L, Theilade E, Poulsen K. Abiotrophia species in early dental plaque. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2000;15(4):263–8. 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2000.150409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin X, Wang Y, Ma Z, et al. Correlation between caries activity and salivary microbiota in preschool children. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13(April):1–16. 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1141474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zuo HJ, Fu MR, Zhao HL, et al. Study on the salivary microbial alteration of men with head and neck cancer and its relationship with symptoms in Southwest China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:1–12. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.514943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim YK, Kwon EJ, Yu Y, et al. Microbial and molecular differences according to the location of head and neck cancers. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):1–11. 10.1186/s12935-022-02554-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mougeot JLC, Beckman MF, Langdon HC, Lalla RV, Brennan MT, Bahrani Mougeot FK. Haemophilus pittmaniae and leptotrichia spp. Constitute a Multi-Marker signature in a cohort of human Papillomavirus-Positive head and neck cancer patients. Front Microbiol. 2022;12(January):1–15. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.794546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive under BioProject ID PRJNA1078109, sample accession SRR28035896-SRR28036043. The publicly available link for the data is listed below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1078109.