Abstract

The proliferation of malaria vectors from irrigated rice crop systems has long been known, though the relationship between rice cultivation and malaria transmission is historically complex. Despite this, contemporary research reveals an association between enhanced malaria vector densities, originating from rice fields, and intensified malaria transmission in rice-associated communities is now occurring. In the wake of the ever-increasing pressures of anthropogenic climate change and a desire to increase rice production across the continent of Africa, alternative rice cultivation practices are being employed. One such alternative practice is the System of Rice Intensification (SRI), which although agronomically contentious is utilised in an attempt to enhance rice yields whilst reducing agricultural inputs, including water. SRI fundamentally alters the rice growing environment and may therefore have significant impacts on the ecology of malaria vector species. As a result, there may be important consequences for local malaria transmission dynamics. The adoption of SRI across Africa is increasing and is likely to do so further in the wake of the pressures of climate change. In this review, we critically discuss the possible impacts of SRI practice on the bionomics of the dominant malaria vector species of Africa.

Graphical Abstract

Created in BioRender. Hardy, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/mo3g1wr

Keywords: System of rice intensification, Malaria, Anopheles, Climate change

Background

The hematophagous behaviour of female mosquitoes presupposes their susceptibility to acquiring pathogens and passing them on to humans, such as in the case of Anopheles mosquitoes and malaria parasites. Despite considerable reductions in malaria cases in the past two decades, malaria continues to cause the highest death toll of any vector-borne disease globally. Africa has historically and presently endured the majority of this burden, and children under five and pregnant women are at the highest risk. Almost half of the global population, across 83 countries, was at risk of malaria in 2023, and an estimated 263 million cases were reported worldwide [1]. Of the 597,000 estimated deaths due to malaria in 2023, the African region accounted for over 95% and, in this region, children under five accounted for 76% of all deaths [1]. Although considerable progress in the control of malaria in the past century has been made, in recent years the effect of such efforts has plateaued and even worsened in the years immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic compared to those before [1].

For a mosquito to be an efficient vector, it must be closely associated with its host, and its longevity sufficient to allow the pathogen or parasite to produce infective stages in adequate quantities for transmission [2]. However, the overall system of malaria transmission is a product of and subject to continuous change through the evolution and development of its components: Anopheles mosquitoes, humans, Plasmodium parasites, and the changing environment.

While suitable habitats for malaria vectors are abundant in nature, human alterations to the landscape can unintentionally create ideal breeding grounds for anopheline mosquitoes. In particular, the proliferation of Anopheles species and rice cultivation are highly associated [3]. The flooding of rice fields provides conducive aquatic habitats that the larvae of Anopheles gambiae sensu lato (s.l.), specifically An. gambiae s.s., An. arabiensis, and An. coluzzii, are well-adapted to exploit [4]. Moreover, irrigation of rice may extend the breeding season of mosquitoes beyond their normal timeframe, depending on local seasonal climatic conditions and the number of cropping cycles [5]. Rice cultivation, therefore, can provide large areas of suitable breeding habitat, leading to higher densities of malaria vectors than would otherwise be the case [6]. However, the relationship between rice cultivation, particularly irrigated rice, and malaria is complex, and increased vector densities have not historically been associated with enhanced malaria transmission in all cases [5], although recent analyses have revealed that communities associated with rice irrigation do indeed experience a higher malaria burden [7]. Despite this, differences in rice cultivation methods, such as flooded and non-flooded irrigation, are associated with significant differences in malaria incidence in associated communities [6], demonstrating a clear need to elucidate how varying cultivation practices may impact this dynamic.

With a rapidly growing population, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have increased the production of rice and between 2008 and 2018; the Coalition for African Rice Development (CARD) policy framework aimed to double rice production in sub-Saharan Africa. The region ultimately achieved a 103% increase in this timeframe and is forecast to continue to rise into 2030 with the goal of self-sufficiency. This increase in production has been attributed largely to enhanced yields rather than the expansion of the total rice cultivation area [8]. Among many other methodologies, the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) is a suite of integrated practices developed to increase rice yields whilst reducing agricultural inputs and, ultimately, altering the rice-growing agroecosystem [9]. Some authors report yield increases from 25 to above 100%, depending on the rice cultivar, with the utilisation of 25–50% less water [10–12], though these claims are not without controversy [13–15]. Nevertheless, SRI continues to be promoted and adopted by resource-poor farmers as a means of increasing yields whilst reducing costs [16], and more generally as a climate change-adapted rice cultivation technique [17, 18].

Through intended environmental modifications, SRI practice may also fundamentally alter the mosquito larval habitat and may, therefore, impact the ecology and biology of malaria vector populations breeding in rice fields. Whilst the impact of SRI on crop pests and insect biodiversity has been addressed [18–20], there has been very little research focusing on how the practice holistically may affect Anopheles mosquitoes, as no peer-reviewed publications could be identified that focus on the subject. However, a single Master’s thesis reported high larval mortalities in SRI fields, relative to conventional rice crop systems [21]. Still, some of the components of SRI have garnered some research attention, particularly alternate wet and dry (AWD) irrigation, which has been demonstrated to reduce Anopheles larval densities [22] and has been suggested as a potential vector control strategy [23, 24]. However, in some cases, farmers have resisted adopting AWD due to concerns that it will increase rodent pest activity, particularly that which results in rice yield losses, despite recent evidence that the practice has no impact on rodent-induced crop damage [25].

With the purported benefits to crop yield with fewer agricultural inputs, reduced water utilisation, and the potential to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions associated with SRI, its adoption will likely continue to rise in the face of the ever-increasing twin challenges presented by anthropogenic climate change and food security [9, 26, 27]. Despite this, the potential for SRI to modify the ecology and biology of Anopheles mosquitoes, and therefore their ability to transmit malaria, remains uncertain. Given the close association between the rice agroecosystem and Anopheles mosquitoes [7], and the dependence of malaria transmission on vector physiology and ecology [28], it is important to study these interrelationships in the context of vector control. Whether SRI leads to the repression or promotion of vector populations and the resultant reduction or exacerbation of malaria transmission, respectively, demands urgent attention.

This review will outline the ecology of the dominant malaria vector species in Africa, within the context of rice cultivation and malaria transmission, give a brief introduction to the broad concepts of SRI, and discuss the potential impacts of SRI on the ecology of malaria vectors.

Dominant vector species of Africa and their larval ecology

Undoubtedly, our advances in the control of Anopheles mosquitoes and malaria manifested from our knowledge of vector species biology and ecology. Understanding how vector mosquitoes behave, where they occur, and how they interact with their environment has allowed us to reduce the transmission of malaria by exploiting key components of their ecology and biology.

Members of the An. gambiae species complex comprise some of the world’s most efficient vectors of malaria. In sub-Saharan Africa, An. gambiae s.s., An. arabiensis, and An. funestus s.l. are considered the dominant vector species (DVS) of the region [29], however, their distribution and relative importance to malaria transmission differ based on local geography and climate. An. gambiae s.s. is prevalent in humid forested zones, whereas An. arabiensis occurs in drier savannah zones due to their adaptation to this climatic niche [30, 31]. Although An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis are more dominant than An. funestus s.l. overall, in some regions the latter species accounts for nearly 90% of all infective bites at relatively lower population densities, suggesting a relatively greater vectorial capacity [32].

Historically, An. gambiae s.s. has been described as the main vector species of Sub-Saharan Africa, owing to its high anthropophily and, hence, vectorial capacity [28, 33]. However, with the mass distribution of LLINs and the use of IRS, marked declines in vector densities have seen a disproportionate reduction in An. gambiae s.s. in comparison to An. arabiensis, leading to a shift in species composition and predominance of An. arabiensis in some regions [34]. The insecticides used to treat LLINs appear to be less effective at killing An. arabiensis than both An. gambiae s.s. and An. funestus s.l. [35, 36], likely due to higher behavioural plasticity and insecticide resistance [37]. Nevertheless, An. gambiae s.s. maintains its status as a DVS, and regional shifts in species composition are likely to continue as insecticide resistance proliferates [38, 39].

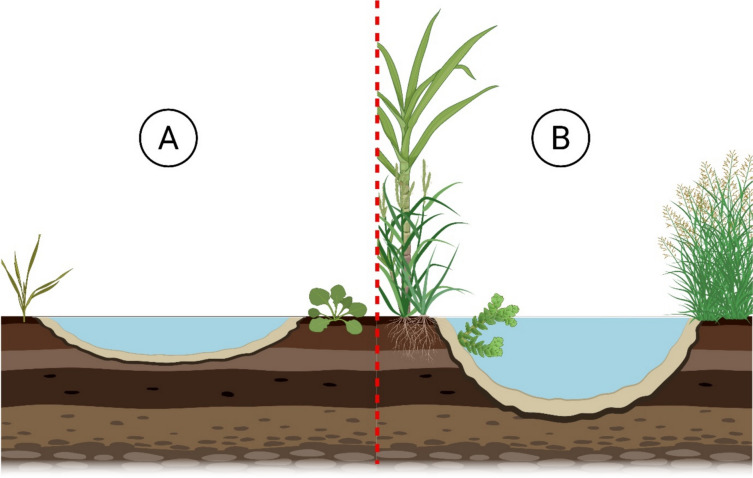

The availability and suitability of larval habitats are key determinants of adult mosquito density, distribution, and fitness [40–44] and, consequently, malaria transmission [28, 45]. Hence, before the discovery and mass use of Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), larval source management was the predominant method of malaria vector control [46]. The larval habitats of An. arabiensis and An. gambiae s.s. are typically shallow, fresh, unpolluted, sunlit water bodies that are small in size with little vegetation [47] (Fig. 1). These breeding sites are usually ephemeral, ranging in size from foot or hoofprints to drainage ditches, cultivated swampland, and irrigated crop systems such as rice fields [48–50]. An. funestsus s.l. is described as breeding in semi-permanent and permanent bodies of water that are shaded by abundant vegetation [51], such as ponds, river edges, savannah, sugar cane plantations, and late-growth rice fields [5, 6, 52].

Fig. 1.

Diagram representing the basic characteristics of An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis (A), and An. funestus s.l. (B) larval habitats. Created in BioRender. Hardy, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/g21k058

Rice cultivation, Anopheles mosquitoes, and malaria

Rice cultivation has long been associated with malaria as the rice agroecosystem provides suitable larval habitats whilst human settlements are often nearby, providing a bloodmeal source for adults [3, 53]. Moreover, rice-associated volatile semiochemicals attract gravid female Anopheles mosquitoes and stimulate them to oviposit [54]. All three of the African DVS can be found inhabiting the rice agroecosystem, among other Culicidae, where a succession of species may be observed in areas in which the three are sympatric. Both An. arabiensis and An. gambiae s.s. may be present in rice fields during the field preparation phase, with their densities typically peaking during the first six weeks of growth post-transplantation. Thereafter, as rice height continues to increase, canopy closure of the vegetation occurs (around weeks 6–8), creating a more shaded environment, in which time An. gambiae s.l. may be completely absent and An. funestus s.l. predominant [55, 56]. After rice harvest, improper field levelling and drainage may result in the formation of shallow sunlit pools, which An. gambiae s.l. readily colonise [57].

In comparison to other common agroecosystems associated with Anopheles mosquitoes, rice cultivation has been found to support the highest abundance of malaria vector species, although the relative abundance can depend on water management practices. In Tanzania, Mboera et al. [6] captured significantly higher numbers (70.7%) of adult An. gambiae s.l. and An. funestus s.l. over eleven months in a flooded field rice agroecosystem, compared to irrigated non-flooding rice (8.6%), sugarcane (7.0%), wet savannah (7.3%), and dry savannah (6.4%) agroecosystems. Similarly, in Kenya, Mwangangi et al. [49] found relatively lower abundances of anopheline larvae in sample sites located in irrigated rice agroecosystems in comparison to those that were primarily flooded fields, rainfed, or supplementarily irrigated by local streams. Consequently, rice agroecosystems support higher biting rates, with up to 46 bites per person per night recorded in communities associated with irrigated rice cultivation in some instances, compared to less than five bites per person per night in association with farmed savannah [58].

Malaria incidence is over six times higher in irrigated rice cultivation communities compared to those associated with pastoral savannah [58]. Similar trends were observed by Rumisha et al. [59], whose cross-sectional malaria screening study in the Mvomero district of Tanzania found 78.1% of those infected were from communities associated with irrigated rice cultivation, 18.7% from Savannah, and only 3.2% from sugarcane agroecosystems. Given the findings of Rumisha et al. [59], it seems clear that of the common agroecosystems associated with Anopheles species in Africa, rice cultivation supports the largest vector populations, human biting rates, and malaria risk, though flooded field systems may pose a relatively greater risk than irrigated systems.

The development of rice irrigation schemes and the risk of malaria transmission is, however, complex and debated in the associated literature. Irrigation channels and the rice fields they supply provide conducive anopheline larval habitats, can prolong breeding seasons, and ultimately lead to the development of increased population densities [60]. An increased population density, holding all other factors constant, would lead to a higher vectorial capacity for a given population [28], and therefore rice irrigation-associated communities would be expected to bear a higher burden of malaria. However, in their landmark study, Ijumba and Lindsay [5] found this is not always the case and communities located close to irrigated rice cultivation may even experience a reduced malaria case incidence compared to those in surrounding areas, despite simultaneously experiencing elevated biting rates. This unexpected phenomenon was termed the “paddies paradox” and several possible explanations may be responsible.

Bed net usage increases in irrigated rice cultivation-associated communities in response to the larger numbers of mosquitoes entering households at night [61], which effectively reduces the biting rate during the hours of sleep and consequently the malaria incidence rate [62]. Moreover, blood feeding is density-dependent, with individuals finding difficulty in attaining a blood meal at high population densities, particularly when bed nets are used, eliciting behavioural changes in feeding such as increased zoophagy [63], thus leading to reduced transmission. Further, Ijumba and Lindsay [5] also posited that in some cases the more competent vector, An. funestus s.l., may be locally displaced by An. arabiensis as the latter species is more suited to the rice field habitat [49]. Lastly, and most prominently, the development of irrigation systems for rice cultivation is associated with socioeconomic benefits in associated communities, where enhanced wealth leads to improved bed net and healthcare access, resulting in reduced malaria case incidence [5]. Though in some cases Ijumba and Lindsay [5] found increased malaria transmission in rice-growing communities, these were attributed to areas of unstable or seasonal transmission, where the human population had little immunity and in some cases had transformed into a stable or perennial transmission system following irrigation development [64, 65].

Since the publication of the “paddies paradox”, considerable reductions in malaria incidence have occurred across Africa with the widespread coverage of modern control strategies [66, 67]. Despite this, we have recently observed a slowdown in malaria case reduction, believed to be brought about by previously effective control measures having reduced efficacy due to behavioural changes and insecticide resistance in vector species [35, 37, 68]. Studies in the past two decades have consistently reported increased malaria transmission risk in association with rice cultivation in areas of stable transmission [6, 58, 59, 69]. Subsequently, a recent meta-analysis of observational studies conducted across 14 different African countries in Sub-Saharan Africa revealed that whilst malaria prevalence was not higher in irrigated rice communities in studies performed before 2003, post-2003 malaria prevalence was 70% higher than in surrounding communities [7]. This may be attributed to the mass rollout of LLINs across sub-Saharan Africa [66], leading to comparable vector protection across communities, revealing the extent to which greater vector proliferation due to rice agriculture enhanced malaria transmission. This demonstrates that irrigated rice cultivation now, contrary to the conclusions of the “paddies paradox”, may increase the risk of malaria in associated communities.

With growing rice production and increased reliance on irrigation, further research is urgently required to improve rice cultivation practices without increasing the malaria burden, especially for new, climate-adapted techniques like SRI, which are being adopted and actively promoted without an understanding of their effect on anopheline ecology and, consequently, malaria transmission.

The system of rice intensification

SRI was developed as a means to increase rice yields in Madagascar by Henri de Laulanié [70] as a response to the large investments, expensive equipment, and infrastructure required for irrigated rice production, which are commonly inaccessible to smallholder farmers across Africa [9]. SRI can also provide improved yields over conventional irrigated or rain-fed cultivation, whilst also reducing water usage and other agricultural inputs [71]. With the mounting pressures of increasing populations, impacts of climate change, and reducing landholdings, a resurgence of interest in low external input intensification practices, such as SRI, is occurring in sub-Saharan Africa [72]. SRI is not considered a single technology, but a “set of interdependent agronomic practices that modify current plant, soil, water, and nutrient management” [26] and it is through this that SRI cultivation systems diverge fundamentally from more conventional irrigated systems and flooded field cultivation systems.

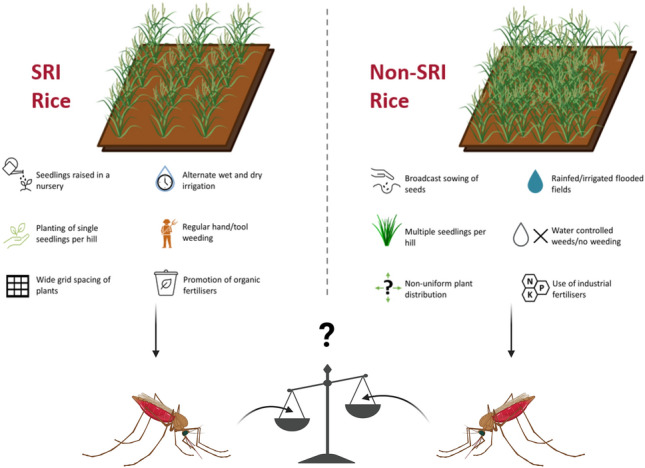

SRI practice consists of three main principles which are applied to field practice, covering the entirety of the rice growth period: (1) planting younger seedlings, (2) planting seedlings at optimal density, and (3) maintaining soils in mostly aerobic conditions [26]. Most publications describe SRI practice as having six core practices [9, 26, 73], although others may combine some principles and reduce the number [18], while some extend these to as many as nine [74]. Regardless, the core ideas of SRI (Fig. 2) remain consistent and can be summarised in terms of six field practices:

Transplant of young seedlings (8–12 days) from a nursery, carefully and quickly (no more than 15–30 min from nursery to field), and at a shallow depth of 1–2 cm.

Transplant of a single rice plant per planting hill, instead of multiple plants.

The wide spacing of individual rice plants (~ 25 cm apart) in a grid fashion.

Carefully controlled water management to create mostly aerobic soil conditions through alternate wetting and drying regimes (AWD).

Addition of organic fertilisers (as opposed to industrially produced fertilisers) such as compost or manure to enhance soil fertility.

Early and regular weeding, either by hand or mechanical weeding tools.

Fig. 2.

Diagram of the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) integrated cultivation practices. Numbers in white circles correspond with field practices used in SRI rice cultivation: (1) transplant of young seedlings; (2) transplant of a single rice plant per hill; (3) wide grid-spacing of individual rice plants; (4) alternate wetting and drying regimes; (5) addition of organic fertilisers; (6) early and regular weeding. Created in BioRender. Hardy, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/a69x034

SRI farming is also divergent from conventional rice cultivation in that it does not typically employ the use of chemical pesticides, herbicides, or fertilisers [74]. However, it has been suggested that SRI would benefit from the addition of chemical fertilisers [75], and with many rice production systems utilising fertilisers already in sub-Saharan Africa [72] it would not be unreasonable to suggest that SRI and chemical fertiliser application are already, or will be, employed together in some cases.

The potential impact of SRI on Anopheles ecology

There has been little published research on the impact of SRI on mosquito ecology and to date, only a single Master’s thesis has formally addressed the subject [21]. However, some of the individual practices of SRI, such as AWD, have been studied somewhat, but the impact of the individual components largely remains unclear. Furthermore, when combined and integrated into SRI cultivation, each of its practices may interact with one another to modify the environment and, therefore, the habitat of juvenile mosquito stages in ways they may not have individually. The consequences for regional malaria burden due to changes in vector ecology demand attention due to SRI’s increasing popularity in sub-Saharan Africa.

Light intensity

One possible outcome of SRI on the environmental characteristics of the rice field is a reduction in the amount of shade within the cropped area. Conventional rice cropping utilises either broadcast sowing, whereby rice seeds are semi-randomly scattered by hand, or the field is populated with rice plants raised in a nursery that are transplanted three or four seedlings to a mound [73]. In contrast, SRI promotes a reduced plant density, whereby single seedlings are transplanted per mound and widely spaced in a grid pattern. SRI fields typically support 16–25 plants/m2, whereas conventional cropping supports up to 150 plants/m2 [9]. SRI’s lower plant density may therefore allow a greater intensity of light to reach the soil and water as reduced rice plant density can increase light penetration [76]. Should wider plant spacing lead to increased light penetration SRI fields may be more attractive to gravid An. gambiae s.l. than An. funestus s.l., and the former may, therefore, predominate over the entirety of the rice growth period.

A study in The Gambia found when vegetation shaded over 25% of the aquatic habitat anopheline larval density significantly decreased by 74% [77]. This effect occurred across multiple habitat types such as rainfed flooded rice fields, man-made puddles, floodwaters and stream fringes where An. gambiae s.s., An. arabiensis and other anopheline mosquitoes were found, indicating that decreased shading may lead to increased abundances of anopheline mosquitoes. Tuno et al. [78] demonstrated the greater survival of An. gambiae s.l. in habitats with higher light exposure, possibly due to increased production of algae, leading to reduced larval mortality [77–80]. This effect may carry over to larval habitats situated in SRI fields as the practice is posited to stimulate algal growth [81].

Mogi and Miyagi [82] found that in irrigated rice fields there was no clear association between the stage of growth, the main source of changing light intensity, and mosquito predator abundance. However, the predator abundance was correlated with larval mosquito mortality, suggesting larval abundance could be a good indicator for predation pressure, but predation pressure is not influenced by the degree of shading. Therefore, reduced shading of aquatic habitats in the SRI environment is unlikely to affect the predation of malaria vector species.

Overall, decreased shading associated with SRI practice may influence both the mosquito population and species composition. Higher light exposure may increase both larval abundance and survival through increased food provisions, leading to an increased juvenile and adult population size. Furthermore, the modified light levels found in SRI systems may favour the oviposition of An. gambiae s.l. over An. funestus s.l., an effect that may extend into the later phases of rice growth, disrupting species succession where An. funestus s.l. can predominate in later rice growth stages, and instead An. gambiae s.l. species dominating over the entire rice growth period.

Water temperatures

Increased light penetration resulting from reduced plant density in SRI practice may also affect the temperature of the surrounding soil substrate, and in turn, the water temperature of the larval habitat. Rice plant spacing in a 25 × 25 cm grid can lead to elevated soil surface temperatures, though these elevated temperatures may only be 1–1.5 °C greater than in higher planting densities, and this relationship is dependent on time of day [83]. Dahiru [73] asserts that AWD also leads to increased soil temperatures as the surface area of standing water is reduced, in comparison to flooded field cultivation, leading to a reduced albedo. Therefore, rice plant spacing, as promoted under SRI management, may result in elevated soil temperatures and consequently, water temperatures.

Increased temperatures reduce larval developmental periods and increase survival, though the trade-off is the production of smaller adults, which have reduced fitness [44, 84–87]. Munga et al. [88] compared the microclimate characteristics between three An. gambiae s.l. habitats and found those with the highest average water temperatures displayed the shortest larvae-to-pupae development time and the highest pupation rates. Comparatively, when studying the impacts of deforestation, Afrane et al. [84] found that water temperatures were 4.8–6.1 °C higher in deforested areas, due to reduced shading, and An. gambiae s.l. larvae experienced both shorter larval to adult development times, by 8–9 days, and increased larval survivorship of 65–82%. Furthermore, a study conducted along the Mara River, which runs through Kenya and Tanzania, found the abundance of Anopheles mosquitoes increased, regardless of habitat type, with increasing water temperature [89]. Lastly, larval development in elevated water temperatures has been demonstrated to enhance insecticide tolerance in both susceptible and resistant populations of An. gambiae s.l. [90]. These field studies indicate that should SRI increase water temperatures, it can be expected that larval survival, development, abundance, and possibly insecticide resistance, will increase.

Within the rice agroecosystem, the relationship between water temperature and Anopheles larval abundance seems to vary mainly with water management practices. A study which in part investigated the impact of environmental variables on rice field-inhabiting mosquitoes in Kenya found An. pharoensis larval abundance was positively correlated with water temperature, whereas no such correlation was observed in An. arabiensis [55]. In contrast, another study in Kenyan rice fields found a positive correlation between the abundance of An. arabiensis larvae and temperature [91]. Both of these studies were conducted in the same geographic location, the Mwea irrigation scheme, Kirinyaga district, though there was more than a year difference in the sampling period. Furthermore, both studies conducted sampling in purposefully established rice paddy sub-plots of the same spatial dimensions and hydrologically separated the subplots with unidirectional inflow and outflow gates to prevent water mixing. However, the former study stated water levels were maintained in the experimental plots at 10 cm depth throughout the sampling period (which is more reflective of a flooded field irrigation regime), whilst the latter study did not disclose any details of water management. Mwangangi et al. [89] did imply water depth varied as they stated that “Up to 20 dipper samples, depending on the amount of water in each subplot, were taken at intervals throughout the subplot by using a standard mosquito dipper”.

When considering water temperature, depth is an important factor as it is intimately linked with the temperature gradient in the water column and the degree to which temperature fluctuates with ambient conditions [92]. In line with this, Muturi et al. [55] reported mean water temperatures did not vary by more than 1.5 °C (between 27.36 and 26.25 °C) over a 14-week rice growth period, whereas Mwangangi et al. [91] described variations of almost 5 °C (between 29.30 and 24.56 °C) within the same period. Both studies reported the highest water temperatures in the earlier stages of the rice growth period, and the lowest in the later stages, when canopy closure would increase the shaded area, and the abundance of An. arabiensis larvae were highest in the early rice growth stages, reducing with increased plant growth. This suggests that the temperature range experienced by the larvae in the latter study was varied to a high enough degree that larval development and survival were significantly impacted, whereas in the former study, the temperature variation was negligible and it is likely other environmental factors played a more important role in determining larval abundance. Lyons et al. [86] demonstrated An. arabiensis survival and development rates scaled linearly with increasing temperature up to 30 °C, shedding light on the disparity between the findings of these two studies, as the larval development rate throughout the study conducted by Mwangangi et al. [91] would be affected by a higher degree than that of Muturi et al. [55]. Considering the use of AWD in SRI practice, it is likely that any standing water in such rice fields will experience a greater degree of variability in terms of its depth and temperature fluctuations, compared to a conventional flooded field system. Considering that fluctuating temperatures are detrimental to the survival and development of An. funestus s.s., and possibly An. gambiae s.s., but not An. arabiensis, the latter species may be more tolerant of conditions in SRI fields.

Should SRI practice lead to increased or more variable water temperatures, it seems likely that the life history traits of any Anopheles mosquitoes inhabiting the rice field will be affected. In general, all three DVS show increased developmental rates with increased temperatures, however, only An. arabiensis is unaffected by wide temperature variations and therefore the SRI-managed fields may be more conducive to the latter species. Combined with a more open canopy structure, potentially increased water temperatures, and the more transient nature of surface water under SRI management, a shift in the species composition may occur whereby An. gambiae s.l. predominate over the entire rice growth period and An. funestsus s.l abundance is reduced. Lastly, An. arabiensis may have a further advantage over An. gambiae s.s., owing to its higher temperature threshold for survival [86], should water temperatures exceed 30 °C on average, possibly leading to An. arabiensis dominating the anopheline species composition.

The multiple impacts of alternate wet and dry irrigation (AWD)

The practice of AWD irrigation within SRI may be the most impactful determinant of mosquito ecology in comparison to conventional systems. AWD irrigation reduces the abundance of mosquitoes in some instances [24, 93] and has been suggested as a means of vector control [23]. Due to the complexities of soil drainage and climate, AWD is not always feasible as it requires rapid drying and drainage [24]. In addition, when AWD is employed, its characteristics vary greatly with some farmers adhering to a strictly regular irrigation regime [18], whilst others use visual indicators such as soil cracking to decide when to commence irrigating [72]. Though proponents of SRI claim the practice leads to greater yields, AWD alone has been found to reduce yields in some cases, or to have no effect in others [9, 17, 94]. As early as 1947, AWD was being evaluated as a means to reduce the abundance of disease vector mosquitoes [93]. However, the integration of AWD and its impact on mosquito ecology when combined with the other practices of SRI have yet to be assessed.

A study by Mutero et al. [94], conducted in the Mwea irrigation scheme in Kenya, highlighted the effect of AWD on the survivability of An. arabiensis larvae by analysing the ratio of early and late instars. The abundance of 1st instar larvae in AWD rice fields was significantly higher, in comparison to continuously flooded fields, paired with a much lower abundance of 4th instar larvae. The ratio of 4th instar to 1st instars was 0.08 in the AWD fields, whereas in the continuously flooded fields, this ranged from 0.27 to 0.68, indicating survival was between 3.3 and 8.5 times lower in the AWD plots. Still, the total number of 4th instar larvae found in AWD fields was similar to that of the conventionally irrigated fields, implying a greater number of eggs were laid in AWD fields. The inability to eliminate larval development by AWD was attributed to the formation of residual pools due to poor land management, which has also been alluded to by others [23, 57].

Contrary to these previous findings, Ijumba [57] found AWD increased mosquito production. Again, this was attributed to the formation of small pools, due to improper field levelling. Despite apparent conflicts in these findings, one factor remains consistent: poor soil drainage characteristics and improper land management can lead to the formation of small shallow pools, which can maintain high mosquito productivity regardless of AWD irrigation. Moreover, a recent study found that “fresher ponds”, aquatic habitats that are newer formed and have had less exposure to climatic effects, experience significantly higher An. arabiensis oviposition rates, therefore, the ongoing replenishment of water in SRI cultivation may contribute to increased larval abundances [97].

A study from southern India further exemplifies the importance and complexities associated with pool formation in AWD irrigation. Rajendran et al. [98] found AWD can reduce the abundance of both culicine and anopheline (An. peditaeniatus, An. tessellatus, and An. barbirostris) larvae, but the irrigation schedule is paramount in achieving this. In the study, a single AWD rice field over a two-year course was examined. In year one, re-irrigation occurred immediately when fields were dry, whereas in year two, this coincided with water availability, which occurred sporadically and often led to only partial drying. In year one, mosquito abundance compared to conventional rice cultivation was significantly lower (− 75–88%), as was mosquito predator abundance, whereas year two predator abundances were lower but mosquito abundance was higher than that of conventional cultivation, a result similar to that found by Ijumba [57]. The authors suggested this was due to an increased predator efficiency in year one caused by the crowding and localisation of their prey, whereas in year two predator abundance was decreased along with predation efficiency due to an increased mosquito habitat area facilitated by incomplete field drying [98].

Another study conducted in Japan [93], where a similar sporadic AWD schedule was applied, reflects the findings of Rajendran et al. [98]. Total aquatic insect abundance, including An. sinensis, was reduced but over time the proportion mosquitoes made up of all insects increased, indicating reduced predation pressures [93]. Conversely, another study in India found AWD irrigation led to a 1.9 times increased abundance of mosquitoes, including both Culex and Anopheles mosquitoes (An. subpictus, An. annularis, An. vagus, An. barbirostris, and An. peditaeniatus), when compared to traditional flooded field cultivation [99]. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that Anopheles mosquitoes may benefit from AWD irrigation, as oviposition in newly formed pools after a dry period provides increased nutritional resources and fewer competitors and predators [100].

If pool formation leads to increased larval crowding, then the deleterious effects of inter- and intraspecific competition may reduce abundances, as both An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis experience increased mortality in mixed-species assemblages in small pools [101]. However, each species responds differentially to pool size; An. arabiensis experiences reduced mortality in small pools vs large pools, whereas An. gambiae s.s. experience the opposite [101]. This implies that AWD may lead to overall reduced abundances but favour the survival of An. arabiensis. These studies underscore the complexity of how AWD may affect mosquito ecology, and that irrigation schedule, land management, and drainage characteristics are significant modulating factors of mosquito abundance and survival.

Nevertheless, An. gambiae s.l. are well adapted to ephemeral and fragmented habitats. Anopheles gambiae s.s. larvae can traverse up to 10 cm after hatching in moist soil to reach water, and their survival in moist soil ranges from 64 hours in first instars to 113 hours in fourth instars [102]. Furthermore, the eggs of An. gambiae s.l. can remain viable for up to 15 days in damp soil [52]. This illustrates the irrigation schedule for AWD schemes is significant, mosaics of small pools can support larvae that don’t hatch within, and the importance of a long enough dry period to effectively control mosquitoes. However, these factors are all modulated and limited by underlying soil hydrology characteristics.

For mosquitoes, AWD may pose three interlinked ecological challenges. The first being increased transience of the aquatic habitat—i.e., the length of time water is physically available and its replenishment frequency, which is known to modulate mosquito productivity and abundance [103]. Within SRI, AWD aims to maintain aerobic soil conditions [9] wherein soil is kept moist whilst avoiding surface water. What bodies of water that do form are often caused by poor land preparation; improper field levelling and footprints/depressions left by workers and machinery can lead to water pooling post-drainage and remain highly productive for mosquitoes [23, 57]. Though, these small ephemeral pools likely experience greater evaporation rates, due to potentially greater light exposure and surface temperatures, thus posing enhanced risks of desiccation for inhabitant mosquitoes, which is alluded to as the main driver behind reduced mosquito densities in AWD managed systems [24].

Second, whilst increased nutritional resources and fewer antagonists occurring in newly formed pools may benefit An. gambiae s.l. [100], increased predation efficiency [98] and competition may mitigate these potential benefits [98, 100, 101]. As the DVS of Africa have varying degrees of desiccation resistance [104], the first two issues would presumably pose a greater challenge to species with longer pre-imago developmentary periods, such as An. funestus s.s., compared to those with shorter, such as An. gambiae s.l. [86]. The duration after the loss of surface water in rice fields before reirrigation is required depends on the groundwater table, where shallower water tables facilitate longer intervals [105]. Thus, there is a high degree of variability between rice cultivation systems employing AWD in terms of how much freshwater is available, how long it is present, and how long it is before a dry field is reirrigated, all of which are of importance to mosquito ecology. A third potential issue is reduced overall available habitat area as less water would be present in the SRI field relative to a conventional rice system, as up to 50% less water use is commonly reported [72, 74]. Reduced habitat availability may have important ramifications for the mosquito population carrying capacity, density-dependent effects, and increased predation within the limited habitat [98].

AWD by itself can significantly impact the ecology of Anopheles mosquitoes, however, there is no consensus among existing research on how exactly mosquitoes are affected, and even less is known about the species-specific effects. The success of AWD in reducing mosquito productivity seems to hinge strongly on the ability to control water drainage, the formation of pools after drying, and the length of time it is feasible to leave the field dry before reirrigation. AWD is capable of both increasing and decreasing the abundance of Anopheles mosquitoes depending on the specifics of its application and this, therefore, reflects the strong influence AWD has on the mosquito habitat in rice fields. Further still, little is known of how the combined effects of SRI practice and AWD may interact to impact mosquito ecology.

Water physicochemistry and microbiome

Physicochemical and microbial aspects of aquatic habitats influence the physiology and ecology of Anopheles species [106]. SRI is characterised by reduced agricultural inputs in comparison to conventional cultivation, typically referring to chemical fertiliser abstinence [74] and utilisation of organic fertilisers (OF) [73]. The composition of OFs varies, often comprising materials freely available to the farmers, such as manure or compost [9], and is one of the reasons SRI is promoted to resource-poor farmers [71–73]. As a result, the composition of OFs used in SRI is highly heterogeneous and poorly characterised [74]. Furthermore, it is reported that some farmers practising SRI are resistant to relying entirely on OFs, or do not have access to the required biomass recommended for soil enrichment, so may utilise chemical fertilisers wholly or in conjunction with OFs [73].

In addition to the use of OFs, the water quality in SRI cultivation may be influenced by weeding, which can aerate the soil and potentially the water too, whilst AWD additionally aims to maintain aerobic conditions [9]. Increased rice tiller development observed in SRI, which is linked to reduced root hypoxia [9], provides evidence for this. Additionally, SRI reduces populations of methanogenic bacteria, which require anaerobic conditions, whilst also promoting methanotrophic bacteria, which require aerobic conditions [107]. Elevated NO3- concentrations are reported in SRI compared to conventional cultivation, where NH4+ predominates from chemical fertiliser application and a lack of oxidative conversion [108].

The addition of OFs will significantly alter the organic material content of the aquatic habitat and underlying soil. Most Anopheles species are known to avoid ovipositing in water contaminated with organic material such as dung or rotting vegetation [109], however, a growing body of evidence indicates not only can populations of Anopheles species breed in organically polluted aquatic habitats [110–112], they may also experience increased development rates and fitness in such environments [113]. However, in the case of manure-based organic fertilisers, the relative benefits of such seem highly dependent on the type of manure. Recent research demonstrates the presence of cow dung enhances larval performance of malaria vector species, both An. arabiensis and An. gambiae s.s. develop into larger adults whilst experiencing no effect on their survival and adult production, whilst the latter species may also develop at a faster rate. However, exposure to chicken dung in these species induces significant mortality, subsequent reductions in adult production, and reduces development rate [114]. Interestingly, whilst chicken dung induces this negative effect, surviving adults are larger, as with cow dung, suggesting both may act as additional nutritional resources [44, 115]. Despite this, An. arabiensis are less likely to oviposit in such sites in favour of those devoid of cow dung. This was also found chicken dung, though, when limited to sites containing only cow or chicken dung, greater oviposition rates occur in the former [116], suggesting the latter is relatively more deterrent to gravid females, reflecting the underlying toxicity of chicken manure and conforming to the larval-preference performance hypothesis [117, 118].

Similarly, vegetative material as OFs can have deleterious effects. A Kenyan study found reduced abundances of An. gambiae s.l. larvae in natural wetland and forest habitats compared to farmlands [119]. Decomposing organic matter, such as leaf litter, was implicated as it produces toxic breakdown products, such as polyphenols and other secondary compounds, that are harmful to some mosquito species, such as An. stephensi, and may repel gravid females [120, 121]. Application of cut grass has been utilised in India for the control of Anopheles mosquitoes, though found ineffective for Afrotropical species. Success in India was found in conventional flooded fields, where anaerobic bacteria break down the vegetative material, and may not apply to SRI [109]. Munga et. al. [119] also stress the importance of microbial communities, facilitated by decaying organic matter, that can elicit both attractive and repulsive behavioural responses in Anopheles species [122, 123]. Despite the importance of microbially-mediated oviposition behaviour, the only microbially excreted compound yet to be identified is cedrol [124], an oviposition attractant of African Anopheles species produced by two fungi species associated with the rhizomes of Cyprus rotundus. Although not a product of organic material decomposition, this is a clear indication of the complex and important role microbial communities play and that similar compounds associated with decomposing OFs used in SRI may also impact oviposition behaviour. Furthermore, should undiscovered microbial communities exist in the rice rhizosphere, SRI may impact them, and any influence on mosquitoes, via improved oxygen availability and greater root development [9].

Despite the aim of mostly aerobic conditions in SRI, the decomposition of organic materials in aquatic habitats causes dissolved oxygen depletion locally, via microbial metabolism. Under SRI conditions, the addition of OFs causes a significantly lower reduction in dissolved oxygen, compared to flooded field cultivation, due to the higher overall oxygen availability caused by SRI practices [125]. Immature mosquitoes do not rely on dissolved oxygen for respiration, and instead, sequester oxygen from the air through their spiracles [106]. Nevertheless, dissolved oxygen concentrations are important to larvae in general [126] but the exact impact on Anopheles species is uncertain.

A study in Ethiopia found increased levels of dissolved oxygen are positively associated with Anopheles larval abundances, but did not specify the species recorded [127]. Another study conducted along the Mara River found a strong positive correlation between dissolved oxygen concentrations and Anopheles larval abundance but again failed to identify the exact species present [89]. However, both corroborate with an earlier Kenyan study which demonstrated the same in An. arabiensis [128]. Similar results have been observed for An. oswaldoi in Venezuela [129] and An. campestris in Thailand [130]. These studies indicate dissolved oxygen plays an important role in Anopheles mosquito larval ecology, however, the species-specific effects have yet to be fully understood and whether these effects occur directly or indirectly, through modifying nutritional resources, such as algae and bacteria.

From these studies, it remains unclear how, when combined in SRI rice cultivation, the various modifiers of water physicochemistry may interact and impact the aquatic habitat’s biotic assemblage, including Anopheles mosquitoes. However, individually these practices have significant yet often conflicting effects on them.

Physical disturbance

In conventional rice cultivation, flooding is the primary means of weed control, however, the use of AWD in SRI necessitates manual weeding achieved through the use of a mechanical weeding tool or simply by hand [9]. Weeding frequency varies, but is most important in early growth when the younger rice plants are more susceptible to competitors [74]. As weed control in this manner is not typical of conventional cultivation, it is important to consider its potential impacts on mosquito ecology. Areas of consideration which require empirical investigation include the possible effects on eggs buried during weeding, whether the disturbance impacts their successful hatching, whether larvae or pupae can survive the physical action of a weeding tool or field-worker passing through their habitat, their responses to increased soil matter suspension, and how this might impact adult oviposition behaviour.

Little to no research has been dedicated to understanding how mechanical or manual weed removal may impact mosquitoes, though some has been conducted on how physical disturbance affects Anopheles mosquitoes. Although eggs of Anopheles mosquitoes have historically been assumed to hatch immediately after embryogenesis, physical agitation is required [131]. Considering that eggs laid by Anopheles mosquitoes in SRI rice fields would be exposed to wind and precipitation, the impact of weeding, no matter how frequent, would be unlikely to cause a dramatic increase in egg hatching, but in theory, it may have an impact, nonetheless. A study in the Philippines found Anopheles larval abundances were greatest in recently ploughed fields, and speculated it was due to reduced predation pressure [82], though agitation may play a role. A similar effect may be observed from the weed removal used in SRI cultivation.

Conclusions

The cultivation of rice is well known to create favourable habitats for the breeding of Anopheles mosquitoes and is implicated in increased malaria incidences in associated communities. However, differences in cultivation practices and socioeconomic factors make this relationship complex. With the increasing pressures of a growing population, demand for rice, and climate change-induced water scarcity, SRI is promoted to simultaneously address these issues. Modifications to conventional rice cultivation, such as controlled irrigation, can modify the ecology of Anopheles mosquitoes and subsequently the transmission of malaria.

SRI modifies the local environment and, therefore, the mosquito habitat in ways not presently understood. If SRI continues to be promoted where malaria is endemic, we must seek to understand how the biotic and abiotic factors associated with Anopheles mosquitoes are modified, and how this may impact their ecology and biology. As these remain unknown, the potential for increasing mosquito productivity, inducing species composition changes, and the potential impact upon malaria transmission also remains unknown. The impacts of SRI on Anopheles mosquitoes have yet to be investigated and, therefore, research needs to be conducted to characterise the SRI rice cultivation system in terms relevant to the ecology of Anopheles mosquitoes. Foremost, field-based empirical research comparing SRI to conventional systems, in terms of Anopheles proliferation, must be conducted with urgency to inform the relative malaria risk SRI may pose, in the wake of its increasing adoption.

Author contributions

H. H.: conceptualisation, research, writing – original draft; R. J. H.: conceptualisation, writing—review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition; L. M.: conceptualisation, writing—review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition; F. M. H.: conceptualisation, writing—review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Funding

This research was funded by UK Research and Innovation’s Expanding Excellence in England Fund under the Food and Nutrition Security Initiative (FaNSI)—50.18 University of Greenwich, Climate Change area.

Data availability

Data supporting the main conclusions of this study are included in the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. World malaria report: addressing inequity in the global malaria response. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohuet A, Harris C, Robert V, Fontenille D. Evolutionary forces on Anopheles: what makes a malaria vector? Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Service MW. Agricultural development and arthropod-borne diseases: a review. Rev Saúde Pública. 1991;25:165–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarju LB, Fillinger U, Green C, Louca V, Majambere S, Lindsay SW. Agriculture and the promotion of insect pests: rice cultivation in river floodplains and malaria vectors in The Gambia. Malar J. 2009;8:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ijumba JN, Lindsay SW. Impact of irrigation on malaria in Africa: paddies paradox. Med Vet Entomol. 2001;15:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mboera LEG, Senkoro KP, Mayala BK, Rumisha SF, Rwegoshora RT, Mlozi MRS, et al. Spatio-temporal variation in malaria transmission intensity in five agro-ecosystems in Mvomero district, Tanzania. Geospat Health. 2010;4:167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan K, Tusting LS, Bottomley C, Saito K, Djouaka R, Lines J. Malaria transmission and prevalence in rice-growing versus non-rice-growing villages in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6:e257–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arouna A, Fatognon IA, Saito K, Futakuchi K. Moving toward rice self-sufficiency in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030: lessons learned from 10 years of the coalition for African rice development. World Dev Perspect. 2021;21:100291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakur AK, Uphoff NT, Stoop WA. Scientific underpinnings of the system of rice intensification (SRI): what is known so far? Adv Agron. 2016;1:147–79. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mati BM, Nyangau WW, Ndiiri JA, Wanjogu R. Enhancing production while saving water through the system of rice intensification (SRI) in Kenya’s irrigation schemes. J Agric, Sci, Technol. 2021;20:24–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thakur AK, Mandal KG, Mohanty RK, Uphoff N. How agroecological rice intensification can assist in reaching the sustainable development goals. Int J Agric Sustain. 2021;20:216–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyamai M, Mati B, Home P, Odongo B, Wanjogu R, Thuranira E. Improving land and water productivity in basin rice cultivation in Kenya through system of rice intensification (SRI). Agric Eng Int CIGR J. 2012;14:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheehy JE, Peng S, Dobermann A, Mitchell PL, Ferrer A, Yang J, et al. Fantastic yields in the system of rice intensification: fact or fallacy? Field Crops Res. 2004;88:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinclair TR, Cassman KG. Agronomic UFOs. Field Crops Res. 2004;88:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoop WA, Kassam AH. The SRI controversy: a response. Field Crop Res. 2005;91:357–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sindano G. Report of the controller and auditor general on the financial statements of Ministry of Agriculture Expanding Rice Production Project (ERPP) for the financial year ended 30th June, 2020 [Internet]. The United Republic of Tanzania National Audit Office; 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 19]. Available from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/903551612272045505/pdf/EXPANDING-RICE-PRODUCTION-PROJECT-AUDIT-REPORT-2019-2020-pdf.pdf

- 17.Andrea P. Potentials of system of rice intensification (SRI) in climate change adaptation and mitigation. A review. IJAPR. 2018;6:160–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thakur AK, Uphoff NT. How the system of rice intensification can contribute to climate-smart agriculture. Agron J. 2017;109:1163–82. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sulaiman N, Isahak A. Diversity of pest and non-pest insects in an organic paddy field cultivated under the system of rice intensification (SRI): a case study in Lubok China, Melaka, Malaysia. J Food Agric Environ. 2013;11:2861–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poerwanto ME, Padmini OS. Impact of “System of Rice Intensification” on the Abundance of Rice Pests. Proceeding of the 1st International Conference on Tropical Agriculture. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 153–61.

- 21.Omwenga K. Impact of the system of rice intensification on mosquito survival in rice paddies and rice yield at Mwea irrigation scheme, Kenya. Juja: Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Djègbè I, Zinsou M, Dovonou EF, Tchigossou G, Soglo M, Adéoti R, et al. Minimal tillage and intermittent flooding farming systems show a potential reduction in the proliferation of Anopheles mosquito larvae in a rice field in Malanville, Northern Benin. Malar J. 2020;19:333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Hoek W, Sakthivadivel R, Renshaw M, Silver JB, Martin HB, Konradsen F. Alternate wet/dry irrigation in rice cultivation: a practical way to save water and control malaria and Japanese encephalitis? Colombo: International Water Management Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keiser J, Utzinger J, Singer BH. The potential of intermittent irrigation for increasing rice yields, lowering water consumption, reducing methane emissions, and controlling malaria in African rice fields. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2002;18:329–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorica RP, Singleton GR, Stuart AM, Belmain SR. Rodent damage to rice crops is not affected by the water-saving technique, alternate wetting and drying. J Pest Sci. 2020;93:1431–42. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uphoff N. Higher yields with fewer external inputs? The system of rice intensification and potential contributions to agricultural sustainability. Int J Agric Sustain. 2003;1:38–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uphoff N. SRI 2.0 and beyond: sequencing the protean evolution of the system of rice intensification. Agronomy. 2023;13:1253. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brady OJ, Godfray HCJ, Tatem AJ, Gething PW, Cohen JM, McKenzie FE, et al. Vectorial capacity and vector control: reconsidering sensitivity to parameters for malaria elimination. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2016;110:107–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Rubio-Palis Y, Chareonviriyaphap T, Coetzee M, et al. A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mnzava AP, Kilama WL. Observations on the distribution of the Anopheles gambiae complex in Tanzania. Acta Trop. 1986;43:277–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindsay SW, Parson L, Thomas CJ. Mapping the ranges and relative abundance of the two principal African malaria vectors, Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto and An. arabiensis using climate data. Proc Royal Soc London Ser B: Biol Sci. 1998;265:847–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nambunga IH, Okumu F, Ngowo H, Mapua S, Hape E, Msugupakulya B, et al. Aquatic habitats of the malaria vector, Anopheles funestus in rural south-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2020;19:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White GB. Anopheles gambiae complex and disease transmission in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1974;68:278–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derua YA, Alifrangis M, Hosea KM, Meyrowitsch DW, Magesa SM, Pedersen EM, et al. Change in composition of the Anopheles gambiae complex and its possible implications for the transmission of malaria and lymphatic filariasis in north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2012;11:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitau J, Oxborough RM, Tungu PK, Matowo J, Malima RC, Magesa SM, et al. Species shifts in the Anopheles gambiae complex: do LLINs successfully control Anopheles arabiensis? PLoS ONE. 2012;7:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindblade KA, Gimnig JE, Kamau L, Hawley WA, Odhiambo F, Olang G, et al. Impact of sustained use of insecticide-treated bednets on malaria vector species distribution and culicine mosquitoes. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perugini E, Guelbeogo WM, Calzetta M, Manzi S, Virgillito C, Caputo B, et al. Behavioural plasticity of Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles arabiensis undermines LLIN community protective effect in a Sudanese-savannah village in Burkina Faso. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Protopopoff N, Matowo J, Malima R, Kavishe R, Kaaya R, Wright A, et al. High level of resistance in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae to pyrethroid insecticides and reduced susceptibility to bendiocarb in north-western Tanzania. Malar J. 2013;12:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knox TB, Juma EO, Ochomo EO, Pates Jamet H, Ndungo L, Chege P, et al. An online tool for mapping insecticide resistance in major Anopheles vectors of human malaria parasites and review of resistance status for the Afrotropical region. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minakawa N, Seda P, Yan G. Influence of host and larval habitat distribution on the abundance of African malaria vectors in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koenraadt CJM, Githeko AK, Takken W. The effects of rainfall and evapotranspiration on the temporal dynamics of Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Anopheles arabiensis in a Kenyan village. Acta Trop. 2004;90:141–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gimnig JE, Ombok M, Kamau L, Hawley WA. Characteristics of larval Anopheline (Diptera: Culicidae) habitats in western Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2001;38:282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okech BA, Gouagna LC, Yan G, Githure JI, Beier JC. Larval habitats of Anopheles gambiae s.s. (Diptera: Culicidae) influences vector competence to Plasmodium falciparum parasites. Malar J. 2007;6:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takken W, Smallegange RC, Vigneau AJ, Johnston V, Brown M, Mordue-Luntz AJ, et al. Larval nutrition differentially affects adult fitness and Plasmodium development in the malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles stephensi. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moller-Jacobs LL, Murdock CC, Thomas MB. Capacity of mosquitoes to transmit malaria depends on larval environment. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fillinger U, Lindsay SW. Larval source management for malaria control in Africa: myths and reality. Malar J. 2011;10:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gillies MT, De Meillon B. The anophelinae of Africa south of the Sahara (Ethiopian zoogeographical region). Johannesburg: South African Institute for Medical Research; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kweka EJ, Zhou G, Munga S, Lee MC, Atieli HE, Nyindo M, et al. Anopheline larval habitats seasonality and species distribution: a prerequisite for effective targeted larval habitats control programmes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mwangangi JM, Shililu J, Muturi EJ, Muriu S, Jacob B, Kabiru EW, et al. Anopheles larval abundance and diversity in three rice agro-village complexes Mwea irrigation scheme, central Kenya. Malar J. 2010;9:228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanek MJ, Shoo B, Mtasiwa D, Kiama M, Lindsay SW, Fillinger U, et al. Community-based surveillance of malaria vector larval habitats: a baseline study in urban Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lwetoijera DW, Harris C, Kiware SS, Dongus S, Devine GJ, McCall PJ, et al. Increasing role of Anopheles funestus and Anopheles arabiensis in malaria transmission in the Kilombero Valley, Tanzania. Malar J. 2014;13:331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ji S, Grueber WB, Mbogo OCM, Githure JI, Riddiford LM. Development and survival of Anopheles gambiae eggs in drying soil: influence of the rate of drying, egg age, and soil type. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2004;20:243–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.WHO. Mosquito ecology. WHO Chron. 1967;21:525–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wondwosen B, Birgersson G, Seyoum E, Tekie H, Torto B, Fillinger U, et al. Rice volatiles lure gravid malaria mosquitoes, Anopheles arabiensis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muturi EJ, Mwangangi J, Shililu J, Muriu S, Jacob B, Kabiru E, et al. Mosquito species succession and physicochemical factors affecting their abundance in rice fields in Mwea, Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2007;44:336–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klinkenberg E, Takken W, Huibers F, Touré YT. The phenology of malaria mosquitoes in irrigated rice fields in Mali. Acta Trop. 2003;85:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ijumba JN. The impact of rice and sugarcane irrigation on malaria transmission in the lower Moshi area in northern Tanzania. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mboera LEG, Bwana VM, Rumisha SF, Malima RC, Mlozi MRS, Mayala BK, et al. Malaria, anaemia and nutritional status among schoolchildren in relation to ecosystems, livelihoods and health systems in Kilosa District in central Tanzania Global health. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rumisha SF, Shayo EH, Mboera LEG. Spatio-temporal prevalence of malaria and anaemia in relation to agro-ecosystems in Mvomero district, Tanzania. Malar J. 2019;18:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yohannes M, Haile M, Ghebreyesus TA, Witten KH, Getachew A, Byass P, et al. Can source reduction of mosquito larval habitat reduce malaria transmission in Tigray, Ethiopia?: Can source reduction of mosquito larval habitat reduce malaria transmission? Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1274–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aikins MK, Pickering H, Alonso PL, D’Alessandro U, Lindsay SW, Todd J, et al. A malaria control trial using insecticide-treated bed nets and targeted chemoprophylaxis in a rural area of The Gambia, West Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agusto FB, Del Valle SY, Blayneh KW, Ngonghala CN, Goncalves MJ, Li N, et al. The impact of bed-net use on malaria prevalence. J Theor Biol. 2013;320:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindsay SW, Adiamah JH, Armstrong JRM. The effect of permethrin-impregnated bednets on house entry by mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in The Gambia. Bull Entomol Res. 1992;82:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dolo G, Briët OJT, Dao A, Traoré SF, Bouaré M, Sogoba N, et al. Malaria transmission in relation to rice cultivation in the irrigated Sahel of Mali. Acta Trop. 2004;89:147–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sissoko MS, Dicko A, Briët OJT, Sissoko M, Sagara I, Keita HD, et al. Malaria incidence in relation to rice cultivation in the irrigated Sahel of Mali. Acta Trop. 2004;89:161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, Bisanzio D, Mappin B, Dalrymple U, et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015;526:207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.WHO. World malaria report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reddy MR, Overgaard HJ, Abaga S, Reddy VP, Caccone A, Kiszewski AE, et al. Outdoor host seeking behaviour of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes following initiation of malaria vector control on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2011;10:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mboera LEG, Bwana VM, Rumisha SF, Stanley G, Tungu PK, Malima RC. Spatial abundance and human biting rate of Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus in savannah and rice agro-ecosystems of central Tanzania. Geospat Health. 2015;10:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laulanié H. Le système de riziculture intensive malgache. Tropicultura. 1993;11:110–4. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stoop WA, Uphoff N, Kassam A. A review of agricultural research issues raised by the system of rice intensification (SRI) from Madagascar: opportunities for improving farming systems for resource-poor farmers. Agric Syst. 2002;71:249–74. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tumusiime E. Suitable for whom? The case of system of rice intensification in Tanzania. J Agric Educ Extens. 2017;23:335–50. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dahiru M. System of rice intensification: a review. Int J Innov Agric Biol Res. 2018;6:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Katambara Z, Kahimba FC, Mahoo HF, Mbungu WB, Mhenga F, Reuben P, et al. Adopting the system of rice intensification (SRI) in Tanzania: a review. AS. 2013;4:369–75. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krupnik TJ, Shennan C, Rodenburg J. Yield, water productivity and nutrient balances under the system of rice intensification and recommended management practices in the Sahel. Field Crop Res. 2012;130:155–67. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nguu NV, De Datta SK. Increasing efficiency of fertilizer nitrogen in wetland rice by manipulation of plant density and plant geometry. Field Crops Res. 1979;2:19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fillinger U, Sombroek H, Majambere S, van Loon E, Takken W, Lindsay SW. Identifying the most productive breeding sites for malaria mosquitoes in The Gambia. Malar J. 2009;8:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tuno N, Okeka W, Minakawa N, Takagi M, Yan G. Survivorship of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae in western Kenya highland forest. J Med Entomol. 2005;42:270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Merritt RW, Dadd RH, Walker ED. Feeding behavior, natural food, and nutritional relationships of larval mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1992;37:349–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Minakawa N, Sonye G, Mogi M, Yan G. Habitat characteristics of Anopheles gambiae s.s. larvae in a Kenyan highland. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:301–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Toriyama K, Ando H. Towards an understanding of the high productivity of rice with system of rice intensification (SRI) management from the perspectives of soil and plant physiological processes. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2011;57:636–49. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mogi M, Miyagi I. Colonization of rice fields by mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) and larvivorous predators in asynchronous rice cultivation areas in the Philippines. J Med Entomol. 1990;27:530–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kumar SM, Thavaprakaash N. Relationship of surface soil temperature on rice (Oryza sativa L.) yield under high density planting in tropics of India. Mausam. 2020;71:709–16. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Afrane YA, Lawson BW, Yan G, Zhou G, Githeko AK. Life-table analysis of Anopheles arabiensis in Western Kenya highlands: effects of land covers on larval and adult survivorship. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:660–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Christiansen-Jucht CD, Parham PE, Saddler A, Koella JC, Basáñez M-G. Larval and adult environmental temperatures influence the adult reproductive traits of Anopheles gambiae s.s.. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lyons CL, Coetzee M, Chown SL. Stable and fluctuating temperature effects on the development rate and survival of two malaria vectors, Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kirby MJ, Lindsay SW. Effect of temperature and inter-specific competition on the development and survival of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto and An. arabiensis larvae. Acta Trop. 2009;109:118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Munga S, Minakawa N, Zhou G, Githeko AK, Yan G. Survivorship of immature stages of Anopheles gambiae s.l. (Diptera: Culicidae) in natural habitats in Western Kenya Highlands. J Med Entomol. 2007;44:758–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dida GO, Gelder FB, Anyona DN, Abuom PO, Onyuka JO, Matano A-S, et al. Presence and distribution of mosquito larvae predators and factors influencing their abundance along the Mara River, Kenya and Tanzania. Springerplus. 2015;4:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oliver SV, Brooke BD. The effect of elevated temperatures on the life history and insecticide resistance phenotype of the major malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar J. 2017;16:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mwangangi JM, Muturi EJ, Shililu JI, Muriu S, Jacob B, Kabiru EW, et al. Environmental covariates of Anopheles arabiensis in a rice agroecosystem in Mwea, Central Kenya. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2007;23:371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Paaijmans KP, Jacobs AFG, Takken W, Heusinkveld BG, Githeko AK, Dicke M, et al. Observations and model estimates of diurnal water temperature dynamics in mosquito breeding sites in western Kenya. Hydrol Process. 2008;22:4789–801. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mogi M. Effect of intermittent irrigation on mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) and larvivorous predators in rice fields. J Med Entomol. 1993;30:309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carrijo DR, Lundy ME, Linquist BA. Rice yields and water use under alternate wetting and drying irrigation: a meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2017;203:173–80. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grainger WE. The experimental control of mosquito breeding in rice fields in Nyanza Province, Kenya, by intermittent irrigation and other methods. East Afr Med J. 1947;24:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mutero CM, Blank H, Konradsen F, van der Hoek W. Water management for controlling the breeding of Anopheles mosquitoes in rice irrigation schemes in Kenya. Acta Trop. 2000;76:253–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Eneh LK, Fillinger U, Borg Karlson AK, Kuttuva Rajarao G, Lindh J. Anopheles arabiensis oviposition site selection in response to habitat persistence and associated physicochemical parameters, bacteria and volatile profiles. Med Vet Entomol. 2019;33:56–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rajendran R, Reuben R, Purushothaman S, Veerapatran R. Prospects and problems of intermittent irrigation for control of vector breeding in rice fields in southern India. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;89:541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Krishnasamy S, Amerasinghe FP, Sakthivadivel R, Ravi G, Tewari S, Van Der Hoek W. Strategies for conserving water and effecting mosquito vector control in rice ecosystems: a case study from Tamil Nadu. India: Iwmi; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Duchet C, Mukherjee S, Stein M, Spencer M, Blaustein L. Effect of desiccation on mosquito oviposition site selection in Mediterranean temporary habitats. Ecol Entomol. 2019;45:498–513. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Paaijmans KP, Huijben S, Githeko AK, Takken W. Competitive interactions between larvae of the malaria mosquitoes Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles gambiae under semi-field conditions in western Kenya. Acta Trop. 2009;109:124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Koenraadt CJ, Paaijmans KP, Githeko AK, Knols G, Takken W. Egg hatching, larval movement and larval survival of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae in desiccating habitats. Malar J. 2003;2:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fillinger U, Sonye G, Killeen GF, Knols BGJ, Becker N. The practical importance of permanent and semipermanent habitats for controlling aquatic stages of Anopheles gambiae sensu lato mosquitoes: operational observations from a rural town in western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:1274–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gray EM, Bradley TJ. Physiology of desiccation resistance in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:553–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mishra HS, Rathore TR, Pant RC. Effect of intermittent irrigation on groundwater table contribution, irrigation requirement and yield of rice in Mollisols of the Tarai region. Agric Water Manage. 1990;18:231–41. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Clements AN. The biology of mosquitoes, vol. 1. London: Chapman & Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rajkishore SK, Doraisamy P, Subramanian KS, Maheswari M. Methane emission patterns and their associated soil microflora with SRI and conventional systems of rice cultivation in Tamil Nadu, India. Taiwan Water Conserv. 2013;61:126–34. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jain N, Dubey R, Dubey DS, Singh J, Khanna M, Pathak H, et al. Mitigation of greenhouse gas emission with system of rice intensification in the Indo-Gangetic Plains. Paddy Water Environ. 2014;12:355–63. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gilles HM, Warrell DA. Essential malariology. 4th ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gunathilaka N, Fernando T, Hapugoda M, Wickremasinghe R, Wijeyerathne P, Abeyewickreme W. Anopheles culicifacies breeding in polluted water bodies in Trincomalee District of Sri Lanka. Malar J. 2013;12:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]