Abstract

Background

Postpartum depression has a rising global prevalence. Although it receives respectable attention in research, it is not adequately considered in practice. Perceived social support is among the most influential protective factors of PPD; however, the role of sources of social support in the development of PPD is not yet fully discovered. Therefore, this research aims to identify the differential effects of the sources of social support on symptoms of PPD while also investigating the mediating role of resilience.

Methods

The data analysed In this study were collected from 197 women with parturition within six weeks to a year, aged 25 to 41 (M = 30.36, SD = 3.703). Participants were recruited from public and private hospitals and clinics specializing in paediatric and obstetrics/gynaecology care in Cairo, Egypt, and through social media support groups for pregnant and postpartum women. Data were collected using the Arabic multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS), the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ) ‘Resilience’ subscale. Multiple linear regression and mediation analyses by structural equation model (SEM) were performed to test the study’s hypotheses.

Results

Friends’ social support was the only significant source in the regression model (β = -.242, t = -3.297, p < .001). However, the overall model was also significant (F (3, 193) = 11.692, p < .001). Resilience significantly and partially mediated the relationship between support from significant others (SO) and PPD symptoms (β = -.042, 95% CI [-0.080, -0.004], z = -2.159, p < .031). However, resilience did not indirectly influence the relationship between family support and PPD symptoms (β = -.025, 95% CI [-0.058, 0.008], z = -1.494, p < .135) and family support and PPD symptoms (β = -.027, 95% CI [-0.056, -0.002], z = -1.830, p < .067) were not significant.

Conclusions

Perceived social support from friends significantly predicts PPD symptoms. The support from significant others impacts symptoms of postpartum depression directly and indirectly through resilience. These findings emphasize social support as protective against PPD risk and enhancing for resilience.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13010-025-00190-2.

Keywords: Postpartum depression, Social support, Family, Friends, Significant others, Resilience

Background

The postpartum period refers to the time from delivery and lasts until a woman’s body recovers to its pre-pregnancy state. The duration differs among women [48]. It is a critical period where physiological, psychological, and social changes occur in the life of the mother and her family [17]. Adequate postpartum care and management of possible challenges are crucial to prevent physical and psychological disorders [43]. Postpartum depression is among the most prevalent risks that can occur during this period. It is defined as a mental health disorder that affects women after childbirth, characterized by depressed mood, crying episodes, changes in appetite and sleep, anhedonia, loss of energy, irritability, hopelessness, recurrent thoughts of suicide, and less commonly homicidal thoughts toward the baby [1]; it affects around 10 percent of pregnant women worldwide [58] with the highest reported global prevalence of 63.3% [55].

Among the negative consequences of untreated PPD are the financial burden on the healthcare system, poor family functioning, mother-infant bonding, and child development [14, 29] as well as death by suicide [24, 57]. Understanding postpartum depression and its risk factors has been of Interest to researchers since the disorder was first Introduced In the late 80s, one of which is the lack of social support.

Perceived and actual social support received from family, friends, and spouses is among the most identified correlates with postpartum depression. However, a lack of consensus on the most influential type/source of support radiates in the literature [61]. In addition, the underlying mechanism through which social support influences postpartum depression remains unclear and seldom investigated. Uncovering the impact of different sources of social support on postpartum depression can dramatically alter the type of postpartum care provided to result in better psychological outcomes. Moreover, understanding how social support impacts postpartum depression can highlight principles for early intervention that alleviate the effects of the lack of social support by targeting it directly or through these mechanisms.

Resilience is the individual’s ability to accommodate to the demands of adversities and challenges through cognitive and behavioural flexibility. Research has proven that resilience is a skill that can be developed and practiced [47]. This study defines resilience as the positive psychological state adapted from the psychological capital questionnaire [30]. The investigation of resilience as a mechanism through which social support impacts postpartum depression has great potential in the literature. In addition, integrating the possible mediating effect of resilience with the analysis of the influence of social support on postpartum depression might reveal valuable knowledge to clinical practice and prevention of postpartum depression. Therefore, this study aims to identify the differential effect of sources of social support on symptoms of postpartum depression while investigating the mediating role of resilience, attempting to answer the research questions:

What is the relationship between the different sources of perceived social support and symptoms of postpartum depression?

What are the different effects of sources of social support on postpartum depression symptoms?

What is the relationship between resilience and postpartum depression symptoms?

What is the relationship between sources of perceived social support and resilience?

What is the mediating role of resilience in the relationship between the different sources of perceived social support and PPD symptoms?

Social Support and Postpartum Depression

Social support is a multidimensional variable that has long been prevalent in postpartum research. It is identified among the strongest correlates of PPD [18, 39]. The theoretical explanation of social support adopted in this research is the buffering hypothesis which postulates that social support buffers against the effects of stress to prevent adverse effects [53]. This is aligned with Zimet et al.’s [62] multifactorial approach to scale development.

Low perceived social support inflates the risk for postpartum depression, emphasizing the protective role of perceived social support against PPD [6, 13, 21, 26, 44, 51, 52]. The relation between perceived social support and postnatal depression was similarly identified in Egyptian samples [12].

Some studies identified the influence of different sources of support; social support from spouses and family members reduce the incidence of depression after childbirth and are the most commonly mentioned by postpartum women, followed by support from friends and other family members [3, 16, 40]. Support from friends, relatives, and family received contradicting roles in the literature [10, 41, 42]. A more recent mixed-design study revealed that emotional support from the mother and the spouse was the most frequently reported, and that instrumental support was provided by in-laws and parents. The spouse mainly assisted with feelings of sadness and worry [1].

Women with a lower risk of depression had greater access to social support and social networks with family members and friends. Formal support from hospitals and the government was also common among these women [28]. Peer support during pregnancy and postpartum significantly lowers the risk for postpartum depression [23]. Emotional, instrumental, and informational support were all found inversely correlated with postpartum depression in a large sample of Polish women [64]. Close family relationships, as well as perceived support from the family and in-laws, are directly and indirectly related to postpartum depression and other correlates like sleep quality. In addition, marital satisfaction influences postpartum depression through perceived social support [45].

Social support is important for postpartum women regardless of the number of children; however, some researchers highlight its impact in buffering against role-change-related stress for primiparous women. Partner support received frequent attention in this perspective [5]. While all sources of support are protective against postpartum depression, support from significant others had the strongest correlation with reduced risk of PPD [46].

Although several studies identified the significance of different types/sources of social support, many of the studies were qualitative, and few had this comparison as the primary goal of the study. Moreover, most studies focused on identifying the influence of one source of support rather than comparing the influence of the three sources. In addition, researchers used several measures and operational definitions of social support, therefore resulting in inconsistent findings. Consequently, this study hypothesizes that:

H1: Perceived social support from family, friends, and SO and PPD symptoms are significantly correlated.

H2: Sources of social support have different effects on symptoms of PPD.

Resilience and postpartum depression

Psychological resilience is highly relevant to postpartum depression. Postpartum women are faced with debilitating stress that requires flexibility and adjustment for healthy coping. Women with low resilience are at greater risk for postpartum depression. High Maternal resilience is protective against different sources of stress, including birth complications and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions, and therefore preventive of postpartum depression [35, 36]. It is also protective against depression resulting from traumatic experiences such as birth during the COVID-19 pandemic [50]. Resilience is a significant mediator in the relation between stress and PPD and childhood trauma and PPD [19, 22]. It is also among the strongest predictors of postnatal depression [2]. Resilience is correlated with positive outcomes on anxiety and depression in pregnant women and mothers in highly stressful environments [32, 60].

Despite resilience being a strong protective factor against postpartum depression, there is scarce research on the Egyptian population in this area. Considering research that views the correlation between resilience and postpartum depression is a prerequisite to assuming the mediating role of resilience in the relationship between PPD and perceived social support from the three sources. There is indeed limited research that examined the effects of resilience and social support on postnatal depression simultaneously in general and in Egyptian postpartum women. Thus, the third hypothesis is that:

H3: Resilience and symptoms of postpartum depression are significantly correlated.

Possible mediation effect by resilience

Resilience is a positive capacity that influences social support and is also enhanced by support from others [33, 34]. As social support increases, it provides individuals with information and resources that, in turn, increase their resilience and allow them to better utilize their resources for better coping [56]. These findings are also seen in postpartum women where high support enhances resilience and reduces the risk of postpartum depression [49].

Resilience is increased when support is received from others and results in reduced risk for postpartum depression [33, 34]. Resilience fully mediated the relationship between family relationships and postpartum depression and was the strongest among four other mediators [59]. In a recent study, social support and marital satisfaction influenced PPD only through resilience [25]. With resilience having strong grounds in relation to postpartum depression, there still needs to be more research on the possible mediation by resilience in the relationship between perceived social support and postpartum depression in Egyptian postpartum women. Therefore, the study hypothesizes that:

H4: Resilience and sources of perceived social support are significantly correlated.

H5: Resilience is a significant mediator in the relationship between support from family, friends, and SO and postpartum depression symptoms.

Conceptual model

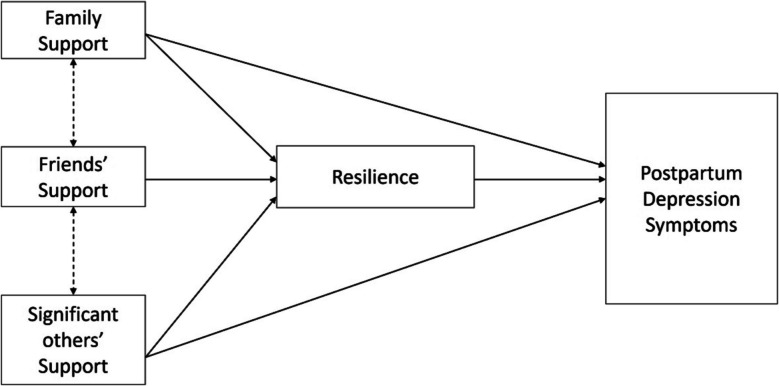

Postpartum depression is a serious mental health condition that Influences 10 percent of pregnant women worldwide [58]. Social support, actual and perceived, is among the strongest correlates of postpartum depression. It is a multidimensional variable with different classifications. The differential effect of the sources of social support, friends, family, and significant others, on postpartum depression deserves to be examined to help in intervention development and family psychoeducation in postpartum care. Psychological and maternal resilience is another significant protective factor of postpartum depression. However, its role as a mediator in the relationship between each of the three sources of perceived social support and postpartum depression is yet to be discovered. To overcome this research gap, the current study aims to examine the differential influence of social support provided by friends, family, and significant others on the risk of postpartum depression while identifying the mediating effect of resilience. This study is the first to examine the hypothesized relationships in the Egyptian population and is expected to provide a culturally specific understanding of the roles of family members, friends, and spouses in the Egyptian population. Figure 1 presents these relationships, where the direct effect of the three different sources of perceived social support on postpartum depression is expected to be indirectly maintained by resilience, as the psychological state adapted from the PCQ. The relationship between resilience and postpartum depression is represented in the conceptual model as well as the relation of resilience to the three sources of perceived social support, not indicating bidirectionality but rather providing information about correlations among variables prior to mediation.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Model

Research methodology

Sample

The study was conducted on a sample of 197 women with parturition within six weeks to a year from January 2024 to March 2024. The sample size was calculated using the power analysis run by G*Power 3.1.9.7 software. The total sample suggested was 182; a sample of 197 was obtained. This sample size is comparable to samples of methodologically robust studies [8, 20, 59].

Participants were recruited from public and private hospitals and clinics specializing in paediatric and obstetrics/gynaecology care in Cairo, Egypt, and through social media support groups for pregnant and postpartum women. The utilized sampling method was a purposive, homogenous method that allowed the researcher to obtain a sample that fits within certain criteria; inclusion criteria: (1) age of the newest born child between 6–12 months and (2) age of the mother between 25 and 41. The researcher controlled for confounding variables: age, educational level, socio-economic level, marital status, number of pregnancies, number of children, and mode of delivery by limiting the inclusion to participants who shared similar characteristics; however, they were not controlled for statistically through the regression model. Therefore, sample homogeneity might impact the generalizability of the results and is considered in the interpretation of the results.

Measures

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)

Perceived social support from the family, friends, and significant other was measured using the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. It is a self-report of 12 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very strongly disagree-7 = very strongly agree) that yields separate scores for each source of support and a total score. Mean scores are considered for Interpretation; therefore, the highest score is 7 for the full scale and for each subscale. High support ranges from 5.1–7, moderate support ranges from 3–5, and low support ranges from 1–2.9 [62]. MSPSS Arabic version has high validity and internal consistency [37]. For the present sample, the scale has high internal consistency (ω = 0.890; α = 0.897) and composite reliability (overall: ω = 0.930, α = 0.897; SO: ω = 0.873, α = 0.865; family: ω = 0.852, α = 0.860; friends: ω = 0.885, α = 0.886).

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

Symptoms of PPD were assessed using EPDS. It is a screening tool for symptoms of postpartum depression. It is a simple self-report scale that consists of 10 items Inquiring about symptoms of depression In the past week for new mothers. Each item is rated from 0–3; the highest obtained score is 30. The scale classifies Individuals as having no depression 0–6, mild depression 9–11, moderate depression 12–13, and severe depression 14–30. A universal cut-off score is 9–10 [4, 7]. It is used independently in this study as scores on the EPDS will represent the risk of PPD, not a diagnosis. The Arabic scale has high sensitivity, specificity, validity, and reliability [15, 27]. Internal consistency (ω = 0.824; α = 0.817) and composite reliability (ω = 0.733, α = 0.817) were high for the present sample.

Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ)

Resilience was measured using the six-item resilience subscale from the psychological capital questionnaire developed by Luthans et al. [30]. The subscale was chosen rather than other established measures of psychological resilience for the following reasons: (1) items on the resilience subscale of the PCQ are adapted from Wagnild and Young’s [54] Resilience scale to assess resilience as a state not a trait, thus allowing for its consideration as a mediator in the proposed conceptual model, (2) the subscale has high validity and reliability as assessed in different populations [31], (3) items on the PCQ are flexibly adapted to different populations and contexts; thus, the version used in this research is an Arabic validated version with high reliability adapted for postpartum women to measure maternal resilience [9], and (4) the six-items resilience subscale has excellent internal consistency (ω = 0.860, α = 0.856) and composite reliability (ω = 0.865, α = 0.856) In the sample of the present study. Scores on this subscale range from 6–36, with higher scores denoting stronger resilience.

Demographic variables questionnaire

Demographic information of participants was obtained using a questionnaire developed by the researcher to assess characteristics necessary for inclusion/exclusion in the study and control of confounding variables. The information collected was participants’ age, educational level, socio-economic level, marital status, number of pregnancies, number of children, and mode of delivery.

Data collection procedures

To collect and analyze data for this study, the researcher approached public and private hospitals and clinics specialized in pediatric and obstetrics/gynecology care in Cairo, Egypt and posted calls for research participants on social media support groups for pregnant and postpartum women. Upon approval received from managers and physicians, the researcher disseminated the study’s questionnaire (demographic data questionnaire, EPDS, MSPSS, and the ‘resilience’ subscale of PCQ) along with the informed consent in a survey link to eligible participants through the physicians. For participants obtained virtually, the researcher posted the survey link and a ‘call for research participants’ message to be accessible to all volunteering participants. All data was reposited in the same platform and analysed simultaneously.

All research procedures were conducted with careful consideration of the APA code of ethics. This entailed that all participants provide their informed consent to participate in the research after being informed of all the procedures, the objectives of the study, their role as participants, fully granted confidentiality, their right to withdraw at any point in time, and their right to ask the researcher to dismiss their responses after submission, and the benefits of participating in the study. In addition, it encompasses that participants can request a report of their results or request a referral to a mental health professional. All research procedures were approved by the Research and Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at the British University in Egypt [2].

Data analysis

Data collected from the 197 participants were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Categorical variables including demographics were described in frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables including age, parity, number of pregnancies, and study variables were represented in means and standard deviations. Confirmatory factor analysis, convergent and discriminant validity, and composite reliability were utilized to confirm the psychometric properties of the data collection tools.

Correlations between MSPSS, EPDS, and ‘Resilience’ subscale scores were primarily assessed. Multiple linear regression was performed to identify the relative importance of the different sources of support on PPD symptoms. Mediation analyses with structural equation model were run to test for mediation by resilience in the relationship between each source of support and postpartum depression.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample consisted of 197 women with parturition within six weeks to a year during the study. Participants were recruited from public and private hospitals and clinics specialized in paediatric and obstetrics/gynaecology care In Cairo, Egypt and through social media support groups for pregnant and postpartum women. All participants aged between 25 and 41 (M = 30.264, SD = 3.70). Most of the sample had a college education (73.604%) while the rest had a postgraduate degree (26.396%). Almost half of the sample were employed (55.33%) and the other half were housewives (44.67%). All participants were Married, and 90.355% belonged to the middle and high socioeconomic class while 9.645% belonged to the low socioeconomic class. Participants had between 1 and 4 pregnancies in their lifespan (M = 1.53, SD = 0.8), between 1 and 4 living children (M = 1.39, SD = 0.65), and 73.096% had a c-section delivery compared to 26.904% undergoing natural birth. The demographic data displayed in Table 1 confirm that the sample is homogeneous.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Sample Characteristics | n | % | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30.26 | 3.703 | ||

| Parity (number of children) | 1.39 | .658 | ||

| Number of Pregnancies | 1.53 | .805 | ||

| Educational level | ||||

| College | 145 | 73.604 | ||

| Postgraduate | 52 | 26.396 | ||

| Employment Status | ||||

| Employed | 109 | 55.33 | ||

| Unemployed | 88 | 44.67 | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 197 | 100 | ||

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | ||

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||

| Middle-High | 178 | 90.355 | ||

| Low | 19 | 9.645 | ||

| Delivery Mode | ||||

| Natural Birth | 53 | 26.904 | ||

| C-section | 144 | 73.096 |

N = 197

Descriptive analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to provide a representation of the distribution of the study variables, depression symptoms, support from SO, support from family, support from friends, and resilience; the data was presented as means and standard deviations (Table 2). The 197 participants had an average score of 16.94 on EPDS (SD = 5.59); the Majority of the sample had elevated symptoms of postpartum depression. The average score on support from significant others was 5.70 (SD = 1.28), on support from family was 5.21 (SD = 1.44), and on support from friends was 4.23 (SD = 1.61). All participants had low to moderate support with support from friends being the lowest. The average score on the ‘Resilience’ subscale was 24.32 (SD = 5.95). Higher scores on the ‘Resilience’ subscale reflect better resilience. Most of the sample had moderate levels of resilience.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EPDS | 16.94 | 5.59 | 1.00 | .817 | ||||

| 2. SO | 5.70 | 1.28 | -.29*** | 1.00 | .865 | |||

| 3. Family | 5.21 | 1.44 | -.30*** | .67*** | 1.00 | .860 | ||

| 4. Friends | 4.23 | 1.61 | -.34*** | .38*** | .41*** | 1.00 | .888 | |

| 5. Resilience | 24.32 | 5.95 | -.36*** | .17* | .111 | .139 | 1.00 | .856 |

The last column of the table includes Cronbach’s alpha for each variable

N = 197

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Correlations

All variables were assessed for correlations together prior to conducting the mediation analysis. Table 2 displays fair correlations between EPDS (postpartum depression symptoms), support from SO, support from family, support from friends, and resilience. All variables were significantly correlated at least at a p-value of 0.05 except for resilience with support from family and support from friends.

Regression and mediation analyses

Multiple linear regression was performed to compare the different effects of the three sources of social support on PPD symptoms. The model was significant F (3, 193) = 11.692, p < 0.001 and accounted for 14.1% of the variance in PPD. Support from friends was the only significant predictor of PPD in this model (β = −0.242, t = −3.297, p < 0.001). Support from family (β = −0.121, t = −1.321, p = 0.188) and significant others (β = −0.120, t = −1.319, p = 1.89) did not significantly contribute to the model. Therefore, support from friends was the most Influential In postpartum depression symptoms compared to support from family and support from spouses as evident by the values of the standardized coefficients; for every one unit Increase in SO support, EPDS score is reduced by 0.838 (Table 3). Despite the multicollinearity between the three sources of social support, which resulted from the homogeneity of the MSPSS, the regression model is not biased and could be interpreted with accuracy because the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for the three predictors are between 1.2 and 1.9, which signal moderate multicollinearity. According to Zuur et al. [63]. VIF of 3 or above is concerning, while between 1–3 indicates no collinearity; this is an even more robust threshold than the VIF-10 threshold suggested by Montgomery & Peck [38].

Table 3.

Regression Analysis

| Effect | B | SE | Beta (β) | t | VIF | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||

| Intercept | 25.926*** | 0.398 | 42.554 | 16.164 | 17.735 | ||

| SO Support | −0.523 | 0.397 | −0.120 | −1.319 | 1.882 | −1.305 | 0.259 |

| Family Support | −0.469 | 0.355 | −0.121 | −1.321 | 1.921 | −1.169 | 0.231 |

| Friends Support | −0.838*** | 0.254 | −0.242 | −3.297 | 1.233 | −1.339 | −0.336 |

N = 197

* p <.05, ** p <.01, *** p <.001

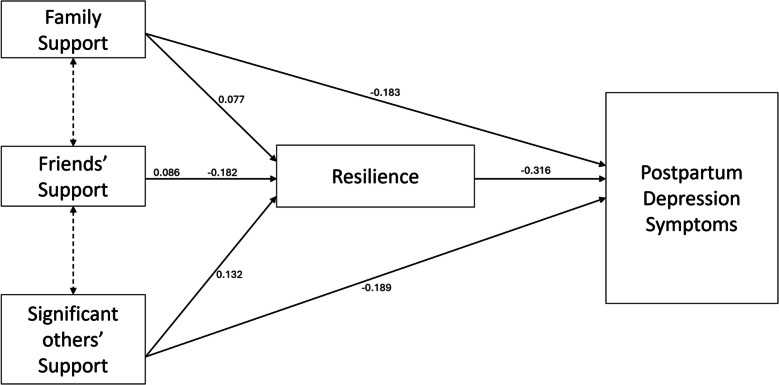

Three separate mediation analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between each source of social support on symptoms of postpartum depression and assess the mediating effect of resilience on these relationships (Fig. 2). The total effect of support from SO on PPD symptoms was significant (β = −0.231, 95% CI [−0.335, −0.126], z = −4.335, p < 0.001). The direct effect of support from SO on PPD symptoms was significant (β = −0.189, 95% CI [−0.289, −0.089], z = −3.700, p < 0.001). In addition, the indirect effect of support from SO on PPD symptoms through resilience was significant (β = −0.042, 95% CI [−0.080, −0.004], z = −2.159, p < 0.031). Therefore, resilience significantly and partially mediates the relation between support from significant others and symptoms of postpartum depression and accounts for 2.9 percent of the variance explained by the effect of support from significant others on PPD symptoms.

Fig. 2.

Mediation Model

The total effect of support from family on PPD symptoms was significant (β = −0.208, 95% CI [−0.300, −0.116], z = −4.427, p < 0.001). The direct effect of support from family on PPD symptoms was also significant (β = −0.183, 95% CI [−0.270, −0.096], z = −4.117, p < 0.001). However, the indirect effect of support from family on symptoms of PPD through resilience was not significant (β = −0.025, 95% CI [−0.058, 0.008], z = −1.494, p < 0.135). This indicates that the relation between support by family and PPD symptoms is not mediated by resilience.

The total effect of support by friends on PPD symptoms was significant (β = −0.209, 95% CI [−0.290, −0.128], z = −5.043, p < 0.001). In addition, the direct effect of support by friends on symptoms of PPD was significant (β = −0.182, 95% CI [−0.259, −0.104], z = −4.607, p < 0.001). However, the indirect effect of support by friends on PPD symptoms was not significant (β = −0.027, 95% CI [−0.056, −0.002], z = −1.830, p < 0.067). Support by friends does not affect PPD symptoms through resilience.

The indirect effect of resilience was significant with only one source of support; therefore, there was no need to compare the regression coefficients of the three models to identify the different effects of the sources of support on postpartum depression while considering the mediating effect of resilience (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Mediation effect by resilience

| Model | Estimate | R2 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||

| Model 1 (SO) | ||||

| Total Effect | −0.231*** | 0.029 | −0.335 | −0.128 |

| Direct Effect | −0.198*** | - | −0.289 | −0.089 |

| Indirect Effect | −0.042* | - | −0.080 | −0.004 |

| Model 2 (Family) | ||||

| Total Effect | −0.208*** | 0.012 | −0.300 | −0.116 |

| Direct Effect | −0.183*** | - | −0.270 | −0.096 |

| Indirect Effect | −0.025 | - | −0.058 | .008 |

| Model 3 (Friends) | ||||

| Total Effect | −0.209*** | 0.019 | −0.290 | −0.128 |

| Direct Effect | −0.182*** | - | −0.259 | −0.104 |

| Indirect Effect | −0.027 | - | −0.056 | 0.002 |

N = 197

* p <.05, ** p <.01, *** p <.001

Discussion

Social support is a significant mental health booster. Its role in protecting against psychiatric disorders is amplified during stressful times [53]. Therefore, it has long been warranted that perceived and actual social support significantly impact the risk of PPD [18, 39]. However, the impact of different types or sources of social support on postnatal depression remains debatable. Therefore, the current study aimed to identify the differential effects of the three sources of perceived social support (family friends, significant other), as assessed by Zimet et al. [62] on the MSPSS, on symptoms of postpartum depression while also assessing the mediating effect of resilience, as assessed on the resilience subscale of the PCQ, in these relationships. The findings of this study revealed that friends' social support had the greatest impact on symptoms of postpartum depression compared to family social support and significant others' social support when analysed simultaneously in a multiple regression model. In addition, resilience only partially mediated the relationship between support from significant others and symptoms of postpartum depression. A detailed discussion of the main findings is presented below.

Family social support is significantly and negatively correlated with postpartum depression symptoms as evident by the significant total effect (β = −0.208, 95% CI [−0.300, −0.116], z = −4.427, p < 0.001). This finding aligns with previous research highlighting the importance of support from family members, mothers, siblings, and in-laws in the antenatal and postpartum periods. Instrumental and emotional support from family members significantly lowers the risk of postpartum depression [1, 3, 16, 28, 40–42].

Perceived friends’ support significantly and negatively predicts symptoms of postpartum depression. This finding was inferred from the significant total effect (β = −0.209, 95% CI [−0.290, −0.128], z = −5.043, p < 0.001). Previous literature supports the notion that friends’ and peers’ support is an important buffer against stress during pregnancy and postpartum [10, 23, 40, 41]. However, some findings go against this idea, postulating that friends’ social support is positively correlated with symptoms of PPD and others stating that friends’ support might have different impacts on mental health depending on how it is perceived [16, 41]. Support from friends is perceived as useful by the present sample due to cultural norms, the collectivist nature of the Egyptian population, and the significance of peer-networks in the Egyptian society, especially for individuals with poor familial ties. Contradictory findings in the literature can be attributed to culture-specific factors of the rural Iranian population, in addition to the growing elderly population, which contributes to fewer social networks among new mothers, resulting in fewer supports from friends. Moreover, the variability in tools used to assess social support, for example, the standard Hopkins Social Support Questionnaire compared to the MSPSS, is expected to yield different results.

Perceived significant others’ support was further significantly and negatively correlated with PPD symptoms (β = −0.231, 95% CI [−0.335, −0.126], z = −4.335, p < 0.001). The first hypothesis of the study was supported by the current study and from the literature. Several studies revealed that support from spouses, even in the form of emotional support, is correlated with the incidence of postpartum depression [1, 5, 16, 40, 45, 46].

Different sources of social support have different effects on postpartum depression. In the current study, friends’ social support was the only source that significantly correlated with postpartum depression, deeming family and spouse social support unimportant in the development of PPD, especially when the effect of the three sources is analysed collectively. The second hypothesis of the study was supported. This finding is also comparable to those of previous studies that revealed that not all sources and forms of social support have similar effects on postpartum depression. For example, a qualitative thematic analysis by Negron et al [40]. identified family and spousal support as the primarily mentioned sources of support followed by friends’ support. Another study identified that spousal and parental support negatively correlate with PPD while support by friends and relatives positively predicts PPD [16]. Disagreement on the contribution of each source of support is evident as another research highlighted the significant correlations between support by friends and relatives and PPD [42].

In support of the third hypothesis of the study and in line with the literature, women with low resilience were more susceptible to higher symptoms of PPD. Resilience is among the strongest protective factors against postpartum depression as it buffers the effects of highly stressful experiences like infants’ admission to the NICU, childhood traumatic experiences, and birth during the pandemic [2, 32, 35, 36, 50, 60]. Additionally, resilience was significantly correlated with perceived social support by SO, supporting part of the fourth hypothesis because resilience did not significantly correlate with support from friends and support from family. There is a reciprocal positive relation between resilience and social support exhibited in postpartum research whereby support enhances resilience and resilience improves the ability to recognize and utilize support [33, 34, 49, 56].

Resilience partially mediates the relationship between perceived social support from SO and postpartum depression. However, it does not mediate the relationship between support from family and PPD nor the relationship between support from friends and PPD. Therefore, hypothesis five was partially supported. The mediation effect of resilience was found in the literature where perceived social support enhances resilience, resulting in a lower incidence of postpartum depression [33, 34]. Resilience was specifically proven to mediate the relation between familial relations, marital satisfaction, and postpartum depression in two separate studies [25, 59]. It is likely that resilience does not matter in the case of high family support and friends’ support but in the case of spouse support in the present sample because of context-specific perceptions. During postpartum, mothers feel more connected to their immediate family, spouse, and child(ren); they perceive support from their husbands as meaningful, therefore their resilience is heightened, and they are more capable of overcoming challenging stressors. Additionally, the collectivistic nature of the Egyptian culture and the strong marital ties, especially in the event of having a newborn, contributes to the mothers’ perception of spousal support as significant. For example, partner support, which is both emotional and material, communicates to the new mother that any challenges can be overcome, therefore bolstering the ability to bounce back from postpartum stress (resilience) and protecting the mother from depression. In accordance with the literature, partners provide emotional support and are most active and useful during times of heightened negative emotions such as sadness or worry [1].

Limitations

Despite its significant findings, this study has a number of limitations that could influence the utilization of its findings. Therefore, the results should be carefully interpreted in light of these limitations. To begin with, the study utilized a cross-sectional design that, while fulfilling the author’s purpose, prevents the development of causal relationships. Future research should employ a longitudinal design to compensate for this drawback. Furthermore, the data was collected using anonymous self-report questionnaires. Physical interviews might provide a better opportunity for probing from the researcher and participants and guarantee a more inclusive conceptualization of participants’ struggles. The sample was recruited using a non-probability, convenience sampling approach; a probability sampling method like random sampling might result in a sample representative of the larger population of Egyptian postpartum women, including women from lower socioeconomic levels and rural areas, and enhance the generalizability of the results. However, the researcher aimed for a homogenous sample that met the designated inclusion criteria. Some characteristics of postpartum women were unintentionally neglected in the data collection process, including delivery complications, infants’ health conditions, and mothers’ previous physical and mental health conditions which limits the generalizability of the study’s findings to postpartum women who share similar characteristics with the study’s sample. Had these characteristics been controlled for and considered, the possibility of drawing causal conclusions would have been facilitated. Moreover, all participants were married; this could be attributed to cultural norms as the sample constituted of women within one year of childbirth, when divorce is unlikely in the Egyptian population. Additionally, the three sources of social support were obtained from the same scale which yields total and sub scores which might have led to multicollinearity, causing insignificant coefficients of the two other sources of support, friends and family. Future research is advised to collect data about these factors and attempt to control them in the sample while aiming for a more diversified and representative sample including diverse SES, geographical locations, and marital conditions.

Practical implications and future direction for research

This study is the first to examine the differential effect of the three sources of perceived social support on PPD while considering the mediating effect of resilience in the Egyptian population of postpartum women; therefore, it has both strong theoretical and significance. The findings of this study can be practically applied in different areas. Firstly, physicians and mental health professionals working with pregnant and postpartum women, including gynaecologists, paediatricians, nutritionists, paediatric nurses, midwives, and psychologists and psychiatrists must be educated about the signs of depression that occur during pregnancy and after birth and be able to assess them and intervene or refer properly. All responsible personnel must emphasize the importance of social support and its impact on physical and mental health to the family and the husband of the pregnant woman. Moreover, psychologists and psychiatrists need to tailor interventions targeted at reducing the risk of PPD by addressing the known risk and protective factors; for instance, enhancing resilience and efficacy which will in turn enhance the utilization of support and resources. Public health policies need to be implemented by responsible governmental entities like the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population to facilitate the devising of these interventions and make them accessible at all levels of healthcare. For example, the EPDS, MSPSS, and other assessments of the known risk factors need to be integrated into the regular check-up regime and be part of the patient’s file at every hospital or facility. Moreover, policies should necessitate training of the responsible physicians and provide a clear referral guide for cases with symptoms of PPD. Despite the large number of known risk and protective factors of PPD, there still needs to be more research to discover these complex relationships with more robust methodologies and representative samples to increase generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

This study analysed the differential effects of the three sources of social support, family, friends, and SO, on postpartum depression. It also considered the mediating effect of resilience in the three relationships. The unique findings of this study provide valuable theoretical and practical knowledge to the Egyptian population of postpartum women. The significance of social support provided by friends is aligned with the Egyptian collectivistic culture that impacts the individuals’ expectations of the roles and responsibilities of extrafamilial members of social networks. Egyptian postpartum women’s resilience is greatly affected by the presence and support of their spouses and influences their mental health during this stressful life period; this could be attributed in great part to the women’s desire for shared responsibility among partners and the cultural tendency to social cohesion. Despite its limitations, the study yielded significant and novel results that have the potential for practical and research implications, specifically tailored for the Egyptian population. Postpartum mental health needs to be prioritized by health professionals as well as family members, husbands, and friends. These parties need to be educated on the most useful type of support to provide to these women.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

I want to thank my esteemed professor- Prof. Mohamed Saad, vice dean of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at The British University in Egypt, for his ongoing support, supervision, and guidance throughout the process of this research. I would also like to express my thanks to Dr. Ahmed Gamal, paediatrician and Dr. Sherif Soliman, obstetric and gynaecologist, and Ms. Mayada Mahmoud, midwife and lactation consultant, for their assistance in the process of obtaining the research sample.

Abbreviations

- EPDS

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale

- PPD

Postpartum depression

- MSPSS

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

- SO

Significant other

- PCQ

Psychological capital questionnaire

- SEM

Structural equation model

Author's contributions

H.K.A is the single author of this research.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). NA.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data for this study are available and included as a supplementary information file.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research is approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at The British University in Egypt. Participants provided informed consent before participation in the study.

Consent for publication

Participants consented to the publication of their anonymous test results.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Archana M, et al. Social support during the postpartum period: mothers’ experiences and expectations – a mixed methods study in a rural area of South Karnataka. Natl J Res Community Med. 2018;7(2(30)):113–8. 10.26727/njrcm.2018.7.2.113-118. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baattaiah BA, et al. The relationship between fatigue, sleep quality, resilience, and the risk of postpartum depression: an emphasis on maternal mental health. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):10. 10.1186/s40359-023-01043-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banovcinova, Lubica, and Karolina Klabnikova. “The impact of social support on the risk of postpartum depression.” SWS International Scientific Conferences on SOCIAL SCIENCES - ISCSS, 20 Dec. 2022, 10.35603/sws.iscss.2022/s06.062.

- 4.BC Reproductive Mental Health Program and Perinatal Services BC. (2014) 'Best Practice Guidelines for Mental Health Disorders in the Perinatal Period.' Available at: http://tiny.cc/MHGuidelines

- 5.Bintaş Zörer P, et al. Doğum Sonrası Depresyonda bağlanma örüntüleri ve partner Desteğinin Rolü. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar. 2019;11(2):154–66. 10.18863/pgy.387288. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho H, et al. Association between social support and postpartum depression. Sci Rep. 2022. 10.1038/s41598-022-07248-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JL, et al. Detection of postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–6. 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delale EA, et al. Stress, locus of control, hope and depression as determinants of quality of life of pregnant women: Croatian Islands’ birth cohort study (cribs). Health Care Women Int. 2021;42(12):1358–78. 10.1080/07399332.2021.1882464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebeid Inas, et al. Psychological capital and prevailing menopausal symptoms among middle-aged women. Egypt J Health Care. 2022;13(4):1474–1487. 10.21608/ejhc.2022.272203.

- 10.Ekpenyong MS, Munshitha M. The impact of social support on postpartum depression in Asia: A systematic literature review. Mental Health Prev. 2023;30:200262. 10.1016/j.mhp.2023.200262.

- 11.El Saied H, et al. A cross-sectional study of risk factors for postpartum depression. Egypt J Psychiatry. 2021;42(2):108. 10.4103/ejpsy.ejpsy_10_17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Hadidy M, et al. Predictors of postpartum depression in a sample of Egyptian women. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012:15. 10.2147/ndt.s37156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Gan Y, et al. The effect of perceived social support during early pregnancy on depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum: A prospective study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1). 10.1186/s12888-019-2188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Gelaye B, et al. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(10):973–82. 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30284-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghubash R, et al. The validity of the Arabic Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32(8):474–6. 10.1007/bf00789142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajipoor S, et al. The relationship between social support and postpartum depression. Journal of Holistic Nursing and Midwifery. 2021;31(2(1)):93–103. 10.32598/jhnm.31.2.1099. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haran C, et al. Clinical guidelines for postpartum women and infants in primary care–a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell EA, et al. Reducing postpartum depressive symptoms among black and latina mothers. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):942–9. 10.1097/aog.0b013e318250ba48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell KH, et al. Relational resilience as a potential mediator between adverse childhood experiences and prenatal depression. J Health Psychol. 2017;25(4):545–57. 10.1177/1359105317723450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.In J, et al. Tips for troublesome sample-size calculation. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2020;73(2):114–20. 10.4097/kja.19497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inekwe JN, Lee E. Perceived social support on postpartum mental health: an instrumental variable analysis. PLoS ONE. 2022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0265941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Julian M, et al. Resilience Resources, life stressors, and postpartum depressive symptoms in a community sample of low and middle‐income black, Latina, and white mothers. Stress Health. 2023;40(1). 10.1002/smi.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kamalifard M, et al. The Effect of Peers Support on Postpartum Depression: A Single-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. J Caring Sci. 2013;2(3):237–44. 10.5681/jcs.2013.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kamperman AM, et al. Phenotypical characteristics of postpartum psychosis: a clinical cohort study. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(6):450–7. 10.1111/bdi.12523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honarmandnezhad K, et al. Structural model of postpartum depression based on social support and marital satisfaction by Mediating Resilience. J Adv Biomed Sci. 2023. 10.18502/jabs.v13i4.13901.

- 26.Khalajinia Z, et al. Investigation of the relationship of perceived social support and spiritual well-being with postpartum depression. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9(1):174. 10.4103/jehp.jehp_56_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khattab, M. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale ‘Theoretical foundations, competence, and psychometric properties.’ J Psychol Counsel. 2023;77(22):93–203. 10.21608/cpc.2024.332558.

- 28.Kim SJ, et al. Social support for postpartum women and associated factors including online support to reduce stress and depression amidst COVID-19: Results of an online survey in Thailand. PLOS ONE. 2023;18(7). 10.1371/journal.pone.0289250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Letourneau NL, et al. Postpartum depression is a family affair: Addressing the impact on mothers, fathers, and children. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2012;33(7):445–457. 10.3109/01612840.2012.673054. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Luthans F, Youssef CM, Avolio BJ. Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. Oxford University Press. 2007.

- 31.Luthans F, Youssef-Morgan CM . Psychological Capital: An Evidence-Based Positive Approach. DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. digitalcommons.unl.edu/managementfacpub/165. Accessed 29 July 2024.

- 32.Ma X, et al. The impact of resilience on prenatal anxiety and depression among pregnant women in Shanghai. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:57–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masten AS, Reed M-GJ. Resilience in development. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press; 2002. p. 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masten SA, Cutuli JJ, Herbers EJ, Reed JM. Resilience in development. In Snyder RS, Lopez SJ. (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University press. 2009 p. 117–131.

- 35.Mautner E, Stern C, Avian A, et al. Maternal resilience and postpartum depression at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Front Pediatr. 2022. 10.3389/fped.2022.864373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mautner E, Stern C, Deutsch M, et al. The impact of resilience on psychological outcomes in women after preeclampsia: an observational cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):194. 10.1186/1477-7525-11-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merhi R, Kazarian S. Validation of the Arabic translation of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (Arabic-MSPSS) in a Lebanese community sample. Arab J Psychiatr. 2012;23(2):159–68. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montgomery DC, Peck EA. Introduction to linear regression analysis. New York: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morikawa M, et al. Relationship between social support during pregnancy and postpartum depressive state: A prospective Cohort Study. Scientific Reports 2015;5(1). 10.1038/srep10520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Negron R, et al. Social support during the postpartum period: Mothers’ views on needs, expectations, and mobilization of support. Matern Child Health J. 2012;17(4):616–623. 10.1007/s10995-012-1037-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Ni PK, Lin SKS. The role of family and friends in providing social support towards enhancing the wellbeing of postpartum women: a comprehensive systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2011;9(10):313–70. 10.11124/jbisrir-2011-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noury R, et al. Relationship between prenatal depression with social support and marital satisfaction. Sarem Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2016;1(4(1)):153–7. 10.29252/sjrm.1.4.153. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nurbaeti I, et al. Association between psychosocial factors and postpartum depression in South Jakarta, Indonesia. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2019;20:72–76. 10.1016/j.srhc.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Pao C, et al. Postpartum depression and social support in a racially and ethnically diverse population of women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;22(1):105–14. 10.1007/s00737-018-0882-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi W, et al. Effects of family relationship and social support on the mental health of Chinese postpartum women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022. 10.1186/s12884-022-04392-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reid KM, Taylor MG. Social support, stress, and maternal postpartum depression: a comparison of supportive relationships. Soc Sci Res. 2015;54:246–62. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. “Resilience.” Apa Dictionary of Psychology.

- 48.Romano M et al. Postpartum period: three distinct but continuous phases. J Prenat Med. 2010;4(2):22–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Shang X, et al. Relationship between social support and parenting sense of competence in puerperal women: multiple mediators of resilience and postpartum depression. Front Psychiatry. 2022. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.986797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Studniczek A, Kossakowska K. Experiencing pregnancy during the covid-19 lockdown in Poland: a cross-sectional study of the mediating effect of resiliency on prenatal depression symptoms. Behav Sci. 2022;12(10):371. 10.3390/bs12100371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor BL, et al. The relationship between social support in pregnancy and postnatal depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(7):1435–44. 10.1007/s00127-022-02269-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terada S, et al. The relationship between postpartum depression and social support during the covid-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47(10):3524–31. 10.1111/jog.14929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ugarriza DN, et al. Anglo-American mothers and the prevention of postpartum depression. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2007;28(7):781–98. 10.1080/01612840701413624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993;1(2):165–78. [PubMed]

- 55.Wang Z, et al. Mapping global prevalence of depression among postpartum women. Transl Psychiatry. 2021. 10.1038/s41398-021-01663-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, Yanchi et al. The multiple mediation model of social support and postpartum anxiety symptomatology: the role of resilience, postpartum stress, and sleep problems. BMC psychiatry. 2024;24(1):630. 10.1186/s12888-024-06087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Weng SC, et al. Factors influencing attempted and completed suicide in postnatal women: A population-based study in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1). 10.1038/srep25770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Woody CA, et al. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:86–92. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng K, et al. The mediation role of psychological capital between family relationship and antenatal depressive symptoms among women with advanced maternal age: A Cross Sectional Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022:22(1). 10.1186/s12884-022-04811-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Zhang L, et al. Prevalence of prenatal depression among pregnant women and the importance of resilience: a multi-site questionnaire-based survey in mainland China. Front Psychiatry. 2020. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou ES. Social Support. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. 2014 p. 6161–6164. 10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2789.

- 62.Zimet GD, et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zuur Alain F., et al. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol Evol. 2009;1(1):3–14. 10.1111/j.2041-210x.2009.00001.x.

- 64.Żyrek J, et al. Social support during pregnancy and the risk of postpartum depression in Polish women: A prospective study. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1). 10.1038/s41598-024-57477-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The author confirms that all data for this study are available and included as a supplementary information file.