Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In the ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) clinical trial, low-dose aspirin was not associated with survival free of dementia and persistent physical disability (a measure of healthy lifespan), however there was a small increased risk of death. Given the long pre-clinical phase of many aging conditions, we examined the legacy effect (post-trial) and the longer-term effect of aspirin vs placebo through extended follow-up in the ASPREE-XT observational study.

METHODS:

Between 2010 and 2014, 19,114 community-dwelling persons in Australia and the United States, aged predominantly 70 years and older, were randomized to low-dose aspirin or placebo for a median 4.7 years. Post-trial observational follow-up continued for a median (IQR) of 4ˑ3 (4ˑ1, 4ˑ6) years. All components of the primary endpoint (incident dementia, persistent physical disability, death) were adjudicated by blinded expert panels. Analyses used Cox proportional hazards models with intention-to-treat.

FINDINGS:

15,633 participants (56ˑ5% women and 6ˑ2% non-White) were eligible for and agreed to observational follow-up. There was no legacy effect of randomization to aspirin (34.4 events per 1000-person years) vs. placebo (33.7 per 1000 person-years) on the primary endpoint (hazard ratio [HR] 1ˑ02; 95% CI 0ˑ94 to 1ˑ11). Similarly, no long-term effect of aspirin vs. placebo was observed on healthy lifespan over almost a decade of follow-up (HR 1ˑ01; 95% CI 0ˑ95 to 1ˑ08), including no long-term effect on deaths (HR 1ˑ06; 95% CI 0ˑ99 to1ˑ14). No legacy effect of aspirin on incident major hemorrhagic events as compared to placebo was found; however, aspirin was associated with an increased hazard for incident major hemorrhagic events in follow-up over almost ten years HR 1ˑ24; 95% CI 1.10 to 1ˑ39).

INTERPRETATION:

Low-dose aspirin does not appear to be effective in promoting healthy lifespan in initially relatively healthy, community dwelling older persons

FUNDING:

National Institute on Aging and the National Cancer Institute (US).

INTRODUCTION

Prolonging healthy lifespan is a major goal of global health and aging initiatives. For instance, the World Health Organization (WHO) designated 2021 to 2030 as the Decade of Healthy Ageing.1 Global life expectancy increased by 4ˑ6 years from 2000 to 2021, but healthy life expectancy increased by 3ˑ8 years.2 The deficit represents more time spent with disabilities, especially during a person’s older years.3 Public health avenues to increase healthy lifespan in older adults may include a mix of advances which target the basic biology of aging, multimorbidity, and the structural determinants of health.4–7 Aspirin has established secondary prevention effects on multimorbidity from cardiovascular disease and potentially cancer, mainly in middle-aged people. Because aspirin is relatively well-tolerated with a known side-effect profile, readily accessible, and inexpensive, low-dose daily intake has been consistently hypothesized as a pragmatic intervention for maintaining healthy lifespan.8 Aspirin has shown anti-cellular senescence properties through multiple pathways including upregulation of sirtuin-1 and inhibition of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity; however, these actions may take longer to manifest than its short-term platelet-inhibitory processes. 9–12 In the free radical theory of aging, degenerative senescence is hypothesized to be the result of oxidative end products13 which can result in reduced telomerase activity. In vitro experiments with endothelial cells exposed to aspirin (versus no aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents such as ibuprofen) point to only aspirin reducing intracellular reactive oxygen species during cellular aging which results in up-regulation of telomerase activity and delays onset of cellular senescence.9

Legacy effects refer to sustained rather than transient clinical benefit or harm that persists or emerges after trial treatment ends.14 Determining the existence of a legacy effect may provide more definitive evidence on whether earlier exposure to treatment is likely to be beneficial; however, analysis of individual participant data collected after placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials is required.15 The purpose of this analysis is to determine if daily low-dose aspirin confers a legacy effect through prolonging the primary outcome of healthy lifespan, approximately 4 years after the completion of the ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) clinical trial.16–18

ASPREE was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to investigate whether aspirin 100mg taken daily by healthy, community-dwelling older adults would prolong survival free of dementia and persistent physical disability (a measure of healthy lifespan). This endpoint was chosen to allow an integrated assessment of the overall risk–benefit ratio associated with the use of aspirin in community-dwelling older adult population. The trial was terminated at a median of 4ˑ7 years of intervention after a determination was made that it would be very unlikely that a significant treatment effect for continued aspirin use in the trial on healthy lifespan.19 However, given the long pre-clinical phase of many conditions of aging such as dementia, the aim of this study was to determine whether the effect of aspirin on healthy lifespan would manifest as a legacy effect.

METHODS

Study Design

As previously detailed, ASPREE recruited 19,114 participants between March 2010 and December 2014 from 16 sites in Australia and 34 sites in the United States.18 The institutional review board at each participating institution approved the trial, and all the participants provided written informed consent. The randomized study treatment phase continued for a median of 4ˑ7 years until the termination of intervention in June 2017. Shortly thereafter, participants were asked to volunteer to participate in ASPREE-XT, an observational extension phase to examine long-term outcomes, as recently described.20 The institutional review boards for ASPREE-XT which incorporated the use of data from the ASPREE randomized clinical trial phase were Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee ID Number 593–17 in Australia and the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board ID Number 201904807 in the United States.

Study Cohort

The full eligibility criteria of the randomized controlled trial (RCT) and ASPREE-XT have been reported previously.17,20 In brief, for the trial phase, participants were community-dwelling men and women from Australia and the United States who were 70 years of age or older (or ≥65 years of age among Black and Hispanic older adults in the United States) and free from any chronic illness that would be likely to limit survival to less than 5 years. Key exclusion criteria were a clinical diagnosis of dementia, scoring less than 78 on the Modified Mini–Mental State examination (3MS),21documented cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, severe physical limitations,22 a known high risk of bleeding, or a contraindication to aspirin. To be eligible for ASPREE-XT, participants had to have taken part in the RCT phase and be willing to provide written consent (or proxy-approved consent).20 The analysis cohort for the primary endpoint legacy effect consisted of participants who were alive, consented to ASPREE-XT20 and who did not have an adjudicated endpoint of dementia or persistent physical disability by the end of the ASPREE RCT phase.

Study Procedures

During the trial, participants were randomly assigned, in a 1:1 ratio, to receive a 100-mg tablet of enteric-coated aspirin or matching placebo daily, according to a block randomization procedure with stratification according to trial center (in the United States) or general practice clinic (in Australia) and age (65 to 79 years or ≥80 years).17 Adherence to study treatment was assessed with annual tablet counts on returned bottles, with 63.1% of participants taking their assigned intervention in the final 12 months of the ASPREE RCT (no difference by assigned group).19 Annual in-person visits were supplemented by telephone calls every 3 months to encourage retention in the randomized treatment phase and telephone calls every 6 months throughout both phases to collect additional information. Participants were censored at the last participant contact where the participant’s medical history was updated; this could occur via annual visit, scheduled telephone call, or other unscheduled ingoing/outgoing contact with a participant or medical practice.20 Annual visit retention rates during the ASPREE RCT phase were previously reported to be 98% for both treatment groups with 82% still being in-person visits.19

Study Endpoints

The primary composite endpoint was the first occurrence of dementia, persistent physical disability, or death. Expert event-adjudication committees, blinded to treatment assignment, adjudicated events according to established definitions.17,18 The diagnosis of dementia was adjudicated according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition,23 and persistent physical disability was considered to have occurred when a participant reported having an inability to perform or severe difficulty in performing at least one of six basic activities of daily living that had persisted for at least 6 months.22 Although major hemorrhage was the key known harm associated with aspirin exposure that was monitored as a secondary outcome in the ASPREE RCT phase, there was no anticipated major hemorrhage harm associated with the ASPREE-XT observational phase as participants stopped study treatment. However, the secondary endpoint of major hemorrhage was still kept as an adjudicated outcome in the long-term observational phase and general safety monitoring was performed by an independent observational study monitoring board.

Covariates for Subgroup Analyses

Fifteen variables at ASPREE randomization were pre-specified for sub-group analyses in the ASPREE-XT statistical analysis plan.24 Details for the definitions for each of the variables are provided in the supplementary materials. (see eMethods)

Statistical Analysis

Details of the a priori statistical analysis procedures for the observational follow-up phase of the ASPREE RCT are provided.24 In brief, we defined two main estimands (or the precise description of the treatment effect reflecting the clinical question posed by the trial objective):25,26 a legacy effect, and an overall long-term effect on healthy lifespan.

The legacy effect estimand was maintenance of healthy lifespan as estimated by the annual rate of development of the primary composite outcome in the post-trial observational period. Participants who, upon completion of the RCT phase, were still at risk of experiencing the first occurrence of the primary composite endpoint were included based on their intention-to-treat (ITT) trial randomized group.

The overall long-term estimand was the same as the legacy effect estimand; however, it was over the entire cumulative follow-up period from randomization through RCT phase and then the legacy period described above. This estimand addressed what the effects would be of adopting an intended strategy for multi-year regular aspirin over the long-term (approximately 8 years).

For the primary endpoint and secondary endpoint of death, Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative incidence were plotted for the two randomized groups (aspirin and placebo). For all other outcomes, estimates of cumulative incidence (Aalen-Johansen cause-specific cumulative incidence function) were plotted for the two groups. The estimates were obtained from initial study treatment-stratified models in which death (from causes other than any causes incorporated in the outcome of interest) was considered a competing risk. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used for each endpoint and included randomized treatment group as the only covariate. The follow-up time for these models began from the day after June 12, 2017 (legacy effect models) or from randomization (long-term effect models). Proportional hazards assumptions were visually inspected using Schoenfeld residuals and no violation observed.

Analyses also were undertaken within pre-specified subgroups and interaction terms were used to test for heterogeneity of treatment effect of aspirin between subgroups. There were no multiplicity adjustments when calculating p-values for subgroup analyses. The subgroups were defined using variable values at ASPREE randomization. Analyses were conducted for all subgroups for the primary composite endpoint and the secondary endpoints. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to address potential differences between treatment groups at the start of the post-trial period, and thus minimize selection bias. Inverse probability weighting (IPW) for consent to ASPREE-XT was calculated using baseline characteristics and, separately, characteristics at the end of RCT. Multiple imputation using chained equations was utilized to address missing data at the end of RCT.

RESULTS

Participants

Figure 1 shows the participant flow from the RCT (ASPREE) to the post-trial/observational phase (ASPREE-XT). It then illustrates the number of individuals eligible for the legacy analyses with the primary composite outcome, and secondary outcomes of dementia, persistent physical disability or death. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the original 19,114 participants at randomization have been previously published.18 The characteristics of the legacy analyses’ cohort (n = 15,633) at randomization to low-dose aspirin or placebo are shown in Table 1. Participants in the legacy analyses were younger at the time of ASPREE randomization, more likely to be from Australia, less frail, and non-smokers than those not included in the legacy analyses (see Table e1). However, the overall baseline characteristics of the legacy analyses’ cohort did not differ from the overall ASPREE clinical trial cohort, with 82% overlap between the cohorts. The mean (SD) age of the participants in the legacy analyses at the start of ASPREE-XT was 79ˑ5 (4ˑ4) years, and 8,836 (56ˑ5%) of the participants were women. A total of 9ˑ6% of the participants (6ˑ9% of the participants in Australia and 36ˑ3% of those in the United States) reported that they had been regular daily users of aspirin before participation in the trial. Select characteristics of the legacy analyses’ cohort are shown in Supplemental Table e2 for the milestone visit that marked the start of the ASPREE-XT phase with no statistically significant differences by initial treatment group assignment.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics at randomization of the participants included in analyses of legacy effects of aspirin on the primary composite endpoint, according to randomized treatment group.

| Aspirin N = 7,759 | Placebo N = 7,874 | Overall N = 15,633 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, years – mean (SD) | 7483 (4ˑ23) | 7477 (4ˑ18) | 7480 (4ˑ20) |

| Age – n (%) | |||

| 65–73 years | 4062 (52ˑ4) | 4152 (52ˑ7) | 8214 (52ˑ5) |

| ≥74 years | 3697 (47ˑ6) | 3722 (47ˑ3) | 7419 (47ˑ5) |

| Age categorical – n (%) | |||

| 65–69 years | 163 (2ˑ1) | 155 (2ˑ0) | 318 (2ˑ0) |

| 70–74 years | 4569 (58ˑ9) | 4686 (59ˑ5) | 9255 (59ˑ2) |

| 75–79 years | 2042 (26ˑ3) | 2020 (25ˑ7) | 4062 (26ˑ0) |

| ≥80 years | 985 (12ˑ7) | 1013 (12ˑ9) | 1998 (12ˑ8) |

| Gender, woman – n (%) | 4377 (56ˑ4) | 4459 (56ˑ6) | 8836 (56ˑ5) |

| Country – n (%) | |||

| Australia | 7044 (90ˑ8) | 7164 (91ˑ0) | 14208 (90ˑ9) |

| United States | 715 (9ˑ2) | 710 (9ˑ0) | 1425 (9ˑ1) |

| Race/ethnicity – n (%) | |||

| White Aus | 6923 (89ˑ2) | 7002 (88ˑ9) | 13925 (89ˑ1) |

| White US | 352 (4ˑ5) | 375 (4ˑ8) | 727 (4ˑ7) |

| Black | 235 (3ˑ0) | 225 (2ˑ9) | 460 (2ˑ9) |

| Hispanic | 159 (2ˑ0) | 152 (1ˑ9) | 311 (2ˑ0) |

| Additional Groupsa | 90 (1ˑ2) | 120 (1ˑ5) | 210 (1ˑ3) |

| Body Mass Indexb – n (%) | |||

| Underweight (<20 kg/m2) | 125 (1ˑ6) | 132 (1ˑ7) | 257 (1ˑ7) |

| Normal (20–24 kg/m2) | 1860 (24ˑ1) | 1862 (23ˑ8) | 3722 (23ˑ9) |

| Overweight (25–29 kg/m2) | 3479 (45ˑ0) | 3541 (45ˑ2) | 7020 (45ˑ1) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 2268 (29ˑ3) | 2305 (29ˑ4) | 4573 (29ˑ4) |

| Waist circumferencec – n (%) | |||

| Normal | 3493 (45ˑ4) | 3496 (44ˑ8) | 6989 (45ˑ1) |

| High | 4204 (54ˑ6) | 4309 (55ˑ2) | 8513 (54ˑ9) |

| Current smoking, yes – n (%) | 236 (3ˑ0) | 254 (3ˑ2) | 490 (3ˑ1) |

| Diabetes, yesd – n (%) | 781 (10ˑ1) | 781 (9ˑ9) | 1562 (10ˑ0) |

| Hypertension, yese – n (%) | 5702 (73ˑ5) | 5849 (74ˑ3) | 11551 (73ˑ9) |

| Dyslipidemia, yesf – n (%) | 5104 (65ˑ8) | 5245 (66ˑ6) | 10349 (66ˑ2) |

| Cancer history, yesg – n (%) | 1442 (18ˑ6) | 1497 (19ˑ0) | 2939 (18ˑ8) |

| Frailtyh – n (%) | |||

| Not frail | 4859 (62ˑ6) | 4961 (63ˑ0) | 9820 (62ˑ8) |

| Prefrail | 2793 (36ˑ0) | 2797 (35ˑ5) | 5590 (35ˑ8) |

| Frail | 107 (1ˑ4) | 116 (1ˑ5) | 223 (1ˑ4) |

| Previous aspirin use, yes – n (%) | 748 (9ˑ6) | 751 (9ˑ5) | 1499 (9ˑ6) |

| Metformin use, yes – n (%) | 412 (5.3) | 367 (4ˑ7) | 779 (5ˑ0) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease, yesi – n (%) | 1798 (25ˑ1) | 1836 (25ˑ1) | 3634 (25ˑ1) |

| Polypharmacy, yesj – n (%) | 1995 (25ˑ7) | 1929 (24ˑ5) | 3924 (25ˑ1) |

Note: There were no significant (p<0.05) differences between the two randomized treatment groups for any of the characteristics examined.

Ethnicity: Additional Groups encompasses any participant self-reported category with less than 200 participants overall, which included Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, Native American, multiple races or ethnic groups, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and those who indicated that they were not Hispanic but did not state another race or ethnic group.

Body Mass Index (BMI) was determined by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. World Health Organization criteria were used to define underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese. Measures of BMI were missing in 61 (0ˑ4%) of participants.

Waist circumference was dichotomized as normal (≤88 cm for women and ≤102 cm for men) or high (>88 cm for women and >102 cm for men). Measures of waist circumference were missing in 131 (0ˑ8%) of participants.

Diabetes was categorized as self-reported diabetes, elevated fasting blood glucose [≥7mmol/L (Australia) or ≥126 mg/dL (US)] or prescribed medication for diabetes.

Hypertension was defined as those who are on treatment for high blood pressure or those with blood pressure recorded above 140/90 mmHg.

Dyslipidemia was present or absent based on self-reported use of statin at baseline or elevated cholesterol (either serum TC ≥212 mg/dL [≥5ˑ5 mmol/L; for participants in Australia] or ≥240 mg/dL [ ≥6ˑ2 mmol/L for participants in the US] or LDL >160 mg/dL [>4ˑ1 mmol/L]).

Personal history of cancer was recorded as presence or absence based on any history of cancer self-reported at baseline other than non-melanoma skin cancer.

Frailty was categorized using an adapted Fried frailty criteria, which included body weight, strength, exhaustion, walking speed, and physical activity; frailty was defined by the number of criteria satisfied from the Fried Criteria: frail (3+) versus pre-frail (1–2) versus not frail (0).

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) was defined as eGFR <60 ml/min/1ˑ73m2 or uACR ≥3 mg/mmol or renal transplant or routine dialysis. Measures of CKD were missing in 1,142 (7ˑ3%) of participants.

Polypharmacy was defined as taking 5 or more medications.

Legacy Effects on Primary Composite and Secondary Endpoints

After a median (IQR) of 4ˑ3 (4ˑ1, 4ˑ6) years of follow-up post-trial, 2,171 of the 15,633 participants (13ˑ9%) reached the primary endpoint. Among participants who had a primary endpoint event, death was the most common first event in 908 participants (42% of the events), persistent physical disability was the next most common in 683 participants (31% of the events), and dementia was the least common in 580 participants (27% of the events) (Table 2). The rate of the composite of dementia, persistent physical disability, or death was 34ˑ4 events per 1000 person-years in the aspirin group and 33ˑ7 per 1000 person-years in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 1ˑ02; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0ˑ94–1ˑ11; P = ˑ63). The results were unchanged after adjusting for baseline covariates (see Supplementary Table e3A). Additionally, in sensitivity analyses with imputation of missing covariates at baseline and at the end of the ASPREE RCT phase, the results were unchanged (see Supplementary Table e4). In Supplementary Figure e1, a forest plot is shown to highlight the effects of aspirin vs. placebo for pre-specified subgroups based on variables measured at ASPREE randomization. No significant interactions of subgroups with intervention effects were observed for all baseline variables, except for age group (P=0ˑ03). For participants aged 80 years and above, aspirin versus placebo was associated with hazard ratio of 1.26 (95% CI, 1ˑ07–1ˑ48) for the composite outcome, but was not significant for the other age groups.

Table 2.

Legacy period (post-trial) rates of endpoint events and hazard ratios comparing randomized aspirin and placebo groups.

| Endpoint | Aspirin | Placebo | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of pts with event | Rate per 1000 py | No. (%) of pts with event | Rate per 1000 py | |||

|

| ||||||

| Primary endpoint* (N = 15,633) | 1088 (14ˑ0) | 34ˑ37 | 1083 (13ˑ8) | 33ˑ68 | 1ˑ02 (0ˑ94, 1ˑ11) | 0ˑ63 |

| Death | 448 (5ˑ8) | 14ˑ94 | 460 (5ˑ8) | 15ˑ07 | -- | -- |

| Dementia | 293 (3ˑ8) | 9ˑ99 | 287 (3ˑ6) | 9ˑ60 | -- | -- |

| Disability | 347 (4ˑ5) | 11ˑ75 | 336 (4ˑ3) | 11ˑ20 | -- | -- |

|

| ||||||

| Secondary endpoints † | ||||||

| Death (N = 16,357) | 822 (10ˑ2) | 23ˑ91 | 820 (9ˑ9) | 23ˑ35 | 1ˑ02 (0ˑ93, 1ˑ13) | 0ˑ62 |

| Dementia (N = 15,783) | 317 (4ˑ1) | 9ˑ96 | 314 (3ˑ9) | 9ˑ69 | 1ˑ03 (0ˑ88, 1ˑ20) | 0ˑ73 |

| Disability (N = 15,676) | 411 (5ˑ3) | 13ˑ11 | 409 (5ˑ2) | 12ˑ89 | 1ˑ02 (0ˑ89, 1ˑ17) | 0ˑ81 |

The first occurrence of any of the three components (death from any cause, dementia, or persistent physical disability). Participants not included if they experienced any of the three components during the RCT.

For the secondary endpoints, in addition to exclusions for non-consent and loss to follow-up, participants were excluded only if they experienced the specific event or death during the RCT.

The rate of death from any cause was 23ˑ9 events per 1000 person-years in the aspirin group and 23ˑ4 events per 1000 person years in the placebo group (HR, 1ˑ02; 95% CI, 0ˑ93–1ˑ13) (Table 2 and Figure 2). The rate of dementia was 10ˑ0 events per 1000 person-years in the aspirin group and 9ˑ7 events per 1000 person-years in the placebo group (HR, 1ˑ03; 95% CI, 0ˑ88–1ˑ20). The rate of persistent physical disability was 13ˑ1 events per 1000 person-years in the aspirin group and 12ˑ9 events per 1000 person-years in the placebo group (HR, 1ˑ02; 95% CI, 0ˑ89–1ˑ17). The forest plots for each outcome separately were examined (see Figures e2A, e2B, and e2C). Among participants over age 80 at ASPREE randomization, aspirin was associated with developing the persistent physical disability (HR, 1ˑ34; 95% CI, 1ˑ04–1ˑ73), as compared to placebo.

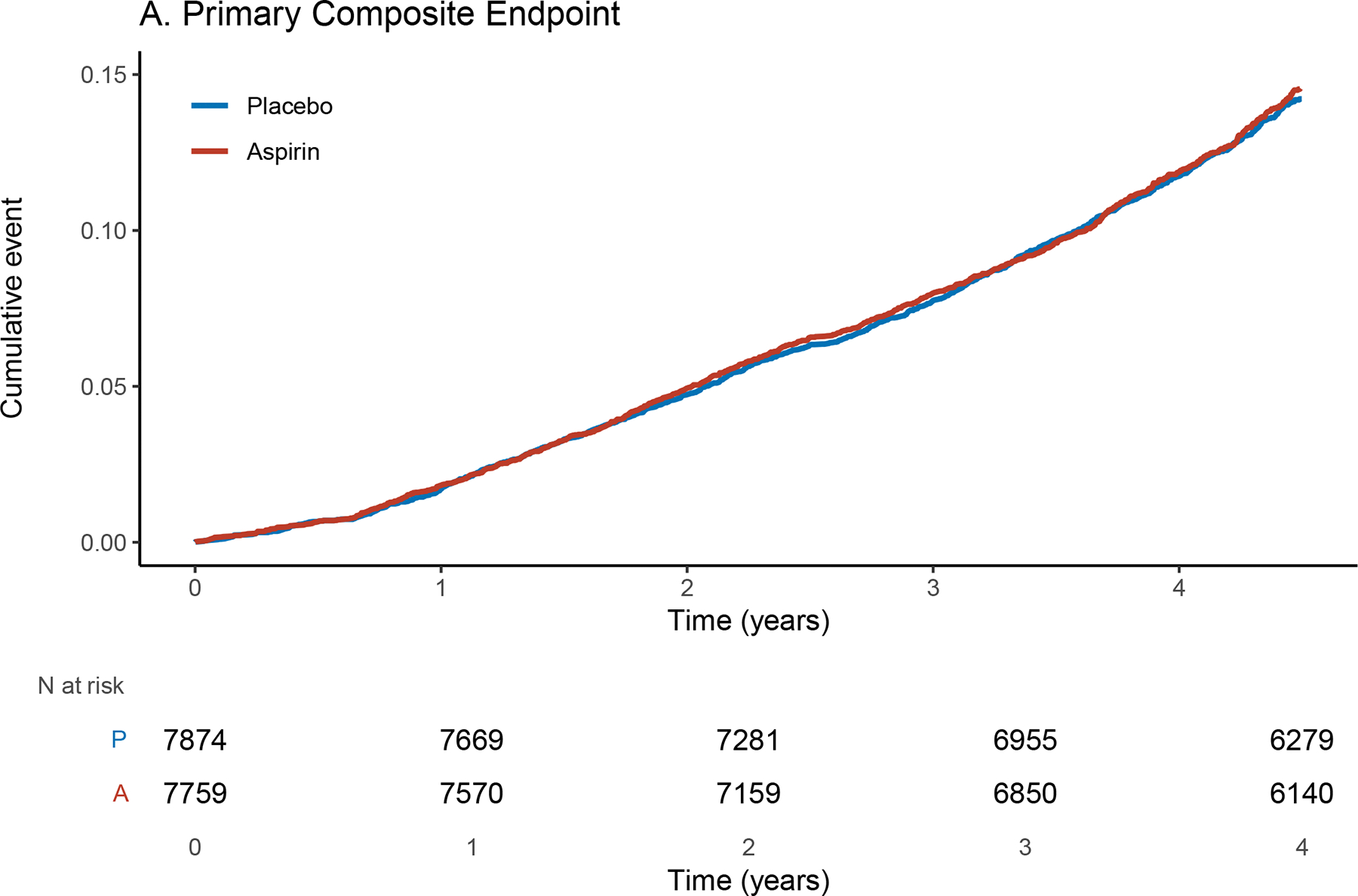

Figure 2.

Cumulative Incidence of the Primary Composite (A) and secondary (B, C, D) endpoints. The x-axis shows time in years from the beginning of the post-trial (ASPREE-XT) period. The y-axis shows the cumulative event rate.

As described in full detail elsewhere,27 the hazard for major adverse cardiovascular events in the legacy phase for aspirin as compared to placebo was 1ˑ18 (95% CI = 1.02–1ˑ37). As expected, given the cessation of study treatment during ASPREE-XT, the hazard for major hemorrhage associated with initial study treatment assignment to aspirin versus placebo was 1ˑ08 (95% CI = 0ˑ91–1ˑ29).

Long-term effects on Primary Composite Endpoint and Individual Components

Figure e3 shows the cumulative incidence of the primary composite endpoint and the individual component outcomes of death, dementia, and persistent physical disability, from ASPREE randomization through the randomized clinical trial phase and the extended follow-up phase. The primary composite endpoint occurred in 2,110 participants in the aspirin group (28ˑ2 events per 1000 person years) and in 2,107 in the placebo group (27ˑ9 events per 1000 person-years). Among participants who experienced the primary composite endpoint event, death was the most common first event in 1,986 participants (47% of the events), dementia was the next most common in 1,140 participants (27%), and persistent physical disability was the least common in 1,091 participants (26%) (Table 3). The between treatment group difference was not significant (HR, 1ˑ01; 95% CI, 0ˑ95–1ˑ08; P= ˑ65) even after adjusting for baseline covariates (see Supplementary Table e3B). Differences between the aspirin group and the placebo group were not substantial for the secondary endpoints (Table e4).

Table 3.

Overall long-term rates of endpoint events and hazard ratios comparing randomized aspirin and placebo groups.

| Endpoint | Aspirin (N = 9,525) | Placebo (N = 9,589) | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of pts with event | Rate per 1000 py | No. (%) of pts with event | Rate per 1000 py | |||

|

| ||||||

| Primary endpoint * | 2110 (22ˑ2) | 28ˑ20 | 2107 (22ˑ0) | 27ˑ89 | 1ˑ01 (0ˑ95, 1ˑ08) | 0ˑ65 |

| Death | 1011 (10ˑ6) | 14ˑ73 | 975 (10ˑ2) | 14ˑ07 | -- | -- |

| Dementia | 569 (6ˑ0) | 8ˑ72 | 571 (6ˑ0) | 8ˑ63 | -- | -- |

| Disability | 530 (5ˑ6) | 8ˑ11 | 561 (5ˑ9) | 8ˑ46 | -- | -- |

|

| ||||||

| Secondary endpoints † | ||||||

| Death | 1547 (16ˑ2) | 19ˑ31 | 1481 (15ˑ4) | 18ˑ25 | 1ˑ06 (0ˑ99, 1ˑ14) | 0ˑ10 |

| Dementia | 601 (6ˑ3) | 8ˑ06 | 616 (6ˑ4) | 8ˑ16 | 0ˑ99 (0ˑ89, 1ˑ11) | 0ˑ87 |

| Disability | 622 (6ˑ5) | 8ˑ53 | 657 (ˑ9) | 8ˑ92 | 0ˑ96 (0ˑ86, 1ˑ07) | 0ˑ45 |

Note: Overall long-term represents the entire period from randomization in ASPREE until Year 4 follow-up in ASPREE-XT (median of 88 years including a median of 47 years in the randomized treatment phase)

The first occurrence of any of the three components (death from any cause, dementia, or persistent physical disability) during the treatment phase and legacy follow-up.

For the secondary endpoints, all the participants who had an event at any time during the trial and legacy followup period are counted.

When analyses stratified by covariates at randomization were conducted (see Figure e4), the aspirin vs. placebo for the composite endpoint had a higher hazard ratio for only the group with age 80 years and over at baseline (HR, 1ˑ14, 95% CI, 1ˑ02–1ˑ27). As shown for the forest plots for the long-term effect of aspirin vs. placebo randomization for each individual outcome (Figures e5A, e5B, and e5C), aspirin in this group was associated with a greater hazard point estimate.

DISCUSSION

In this post-trial 4-year follow-up of ASPREE-XT participants, we did not observe a legacy effect of randomization to aspirin on the primary composite endpoint, nor a legacy effect on the individual secondary components of dementia, persistent physical disability, or death. Similarly, no long-term effect of randomization to aspirin vs. placebo was observed, over a cumulative, almost decade-long period, including no long-term effect on deaths (HR, 1ˑ06, 95% CI, 0ˑ99–1ˑ14). The rigor of these legacy effect analyses for aspirin on healthy lifespan was strengthened by the retention of participants and the moderately strong adherence to assigned study treatment during the ASPREE RCT phase.

The ASPREE RCT of low-dose aspirin over a median 4.7 years in community-dwelling older adults reported no significant effect of aspirin on the primary composite endpoint representing healthy lifespan (HR, 1ˑ01; 95% CI, 0ˑ92–1ˑ11).18 However, among the secondary outcomes, there was an increased risk of death overall (HR, 1ˑ14, 95% CI, 1ˑ01–1ˑ29), a non-significant decrease in incident physical disability (HR, 0ˑ85, 95% CI, 0ˑ70–1ˑ03), and no effect on dementia (HR, 0ˑ98, 95% CI, 0ˑ83–1ˑ15).19 The increased hazard of death and decreased hazard of persistent physical disability extinguished over time after the randomized exposure to aspirin or placebo officially ended.

To the best of our knowledge, legacy effects for aspirin on healthy lifespan have not been previously investigated in a large-scale clinical research study of older adults. The hypothesis for a legacy effect is that intervention exposure results in underlying pathology changes during asymptomatic disease stages or periods before underlying pathology develops.15 Over an extended period, these pathology changes delay the onset of symptomatic emergence of disease.14 The reasons for not finding a legacy or long-term effect of aspirin exposure in a well-powered study of healthy older adults compared to placebo could be many. First, it may be due to aspirin failing to delay the early pathologies related to the diseases impacting healthy lifespan (dementia, persistent physical disability and death). Second, the additional follow-up time frame could still be too short or too late – for example, the pathophysiology of dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease pathology) may begin over two decades before the condition becomes clinically manifest.28 Third, the dose and exposure to aspirin in influencing biological pathways such as inflammation may be too limited to effectively slow the progression of changes accelerating dementia, persistent physical disability, or death.

In addition, there was no evidence of long-term effects of aspirin across predefined subgroups, except for those over age 80, for whom exposure to aspirin vs. placebo was associated with a greater hazard of developing the primary composite endpoint of death, dementia, or persistent physical disability. When the individual components of the primary composite endpoint were examined, aspirin exposure in persons over age 80 was associated with a greater hazard point estimate. However, as the analyses were not powered to address differences of aspirin response on secondary outcomes in specific subgroups defined at ASPREE randomization, the findings must be interpreted with caution. Further work will be needed to examine whether a long-term effect of aspirin is causally associated with increased persistent physical disability and dementia in persons over age 80, especially during the period after exposure is stopped.

Despite the challenges of maintaining participation by older persons in a long-term clinical trial, we successfully extended follow-up of the cohort to enable the examination of legacy and long-term effects. Importantly, we maintained a consistent process of endpoint-adjudication and data collection for adjudication in ASPREE and ASPREE-XT. While the COVID pandemic did result in more telephone engagement, the impact on endpoint-adjudication processes were lessened through modelling alternatives with data from prior, multi-year, in-person testing in ASPREE. Finally, we followed international guidelines for using an estimand-based process for assessing legacy and longer-term effects of aspirin versus placebo exposure on disability-free survival.26 The target population, the variable measured, the handling of intercurrent events, and the population level summary were well-defined prior to analyses being conducted.26

Limitations of the analyses included loss of participants at the end of the ASPREE clinical trial that would have qualified for follow-up in the legacy analyses but chose not to consent to participation in ASPREE-XT (18%). The ASPREE-XT consenting rate amongst the two countries were different (15% not consenting in Australia vs. 41% not consenting in the United States), and individuals enrolled in ASPREE-XT appeared healthier compared to those who were excluded. In addition, the cohort used for analyses of legacy effects is not a randomized sub-set and selection bias could impact interpretation.29 Next, about 9% participants continued to take daily aspirin at the first visit in the ASPREE-XT study;20 the majority on treatment for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease where aspirin has an evidence-base. However, the use of aspirin during ASPREE-XT was evenly distributed between the two groups. In addition, the observed incident rates of the primary composite outcome and the individual components was lower than originally estimated30 This was likely driven by the relatively healthy status of participants at recruitment, including no prior CVD event, together with a rigorous process for adjudication of dementia and disability (persistent over six months), with increased specificity compared to population estimates based on administrative health records. Finally, we examined the heterogeneity of treatment effect via stratification by one variable at a time. Based on PATH criteria,31 we could have utilized other methods for examining heterogeneity of treatment effect such as outcome risk prediction equations. However, these analyses were not selected a priori in the statistical analysis plan for the ASPREE-XT data regarding legacy and long-term effects.

In conclusion, these results from the additional 4 years of longitudinal follow-up after the end of the ASPREE randomized trial indicate that the use of low-dose aspirin older persons who did not have cardiovascular disease was not associated with a legacy or long-term effect on healthy lifespan. These results bolster the current recommendation to not utilize aspirin for maintenance of healthy lifespan based on the original ASPREE randomized, clinical trial. Further research may be needed for determining if harm from aspirin exposure could continue in persons aged 80 years and older.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

On February 11, 2024, we searched MEDLINE and Embase from inception until the end of 2009, for studies investigating the effect of aspirin on dementia, persistent physical disability and death. We used search terms “aspirin” or “NSAIDs” AND “dementia”, “Alzheimer’s Disease”, “Physical Disability”, “Activity limitations”, “mortality” or “death”. Whether daily low-dose aspirin could extend survival free of dementia and persistent physical disability was the primary aim of the ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) clinical trial, which commenced recruitment in 2010. Among 19,114 persons with a median age of 74 years at recruitment, we previously found that a median 4.7 years of aspirin treatment versus placebo, did not prolong dementia- and disability-free survival. In regards to the secondary individual endpoints, we found a slightly higher rate of deaths in the participants randomized to aspirin, but no significant difference for dementia or persistent physical disability. Although the trial ended in 2017 with participants asked to stop treatment, observational follow-up of participants continued.

On February 11, 2024, we searched MEDLINE from inception for studies investigating the effect of aspirin on healthspan. We used search terms “aspirin” AND “healthspan”, “longevity”, “disability-free survival” or “healthy aging”. Aspirin has shown cellular senescence properties through multiple pathways, however there was limited information on the use of aspirin to increase healthy lifespan in older human individuals. Given the long pre-clinical phase of many conditions of aging such as dementia, the effect of aspirin on healthy lifespan could only be evident after a longer period.

Added value of this study

This analysis involved 15,633 participants in the United States and Australia who were originally recruited as part of the ASPREE clinical trial and randomized to aspirin or placebo over a median 4.7 years. Major health events, including dementia (DSM-IV criteria), persistent activities of daily living disability and fact and cause of death, were adjudicated by an international expert panel. We found no significant effect on survival free of dementia and persistent physical disability (a measure of healthy lifespan) over a median 4ˑ3 years of post-trial follow-up, nor on the individual components of the composite endpoint (death, dementia, and persistent physical disability). The longer-term effect of aspirin over a cumulative almost ten years was also null.

Implications of all the available evidence

Despite some suggestion from animal experimental work and observational studies in humans, these findings provide robust evidence to indicate that low-dose aspirin is not effectively in prolonging healthspan in community-dwelling older individuals when used in primary prevention.

Funding/Support:

Data collection and management for the ASPREE (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial and ASPREE-XT were funded by the National Institute on Aging and the National Cancer Institute (US) (U01AG029824 and U19AG062682). The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) also funded the ASPREE randomized clinical trial phase (334047 and 1127060). Bayer AG provided aspirin and matching placebo for ASPREE. Ryan is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Leadership 1 Investigator Grant (2016438). Chan reported receiving grants from the NIH to his institution in support of this manuscript. Dr. Woods reported receiving salary support from the National Institute on Aging and National Health and Medical Research Council in support of this manuscript.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions:

The authors acknowledge the dedicated and skilled staff in Australia and the US for the conduct of the trial and post-trial research study phases. The authors also are grateful to the ASPREE participants, who willingly volunteered for this study, and the general practitioners and medical clinics who supported participants in the ASPREE and ASPREE-XT studies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Shah reported grant funding for work as clinical trial sub-investigator from Athira Pharma, Inc, Edgewater NEXT, Eisai, Inc, Eli Lilly & Co, Inc, and Genentech, Inc, paid to his institution outside the submitted work. Dr. Ryan reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging outside of the submitted work. Dr. Chan reported consulting for Pfizer Inc., and Boehringer Ingelheim and grant funding paid to his institution from Freenome outside the submitted work. Dr. Chong reports receiving honoraria for lectures from Roche outside the submitted work. Dr. Espinoza reports receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging and speaking honoraria from Yale University and the University of Rochester outside the submitted work. Dr. Nelson reports receiving speaking fees from Medtronics outside of the submitted work. Dr. Sheets reports receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging along with the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality and writing honoraria from the International Antiviral Society USA outside of the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Data Sharing Statement

All individual participant data collected during the trial and post-trial, after de-identification, as well as the surveys and data dictionaries, are available via the ASPREE Safehaven immediately following publication and with no end date. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan have been published. Applicants are required to submit a request, with full access details available at www.aspree.org, in order to achieve the aims of a specific project or replicate the results provided here.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report: summary. 2021. Accessed January 27, 2025. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341488/9789240023307-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Health Observatory. World Health Organization. Updated May 2024. Accessed January 27, 2025. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy

- 3.Garmany A, Yamada S, Terzic A. Longevity leap: mind the healthspan gap. NPJ Regen Med. 2021;6:57. doi: 10.1038/s41536-021-00169-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox LS, Faraghar RGA. Linking interdisciplinary and multiscale approaches to improve healthspan—a new UK model for collaborative research networks in ageing biology and clinical translation. Lancet Healthy Longev; 2024;3(5):e318–e320. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00095-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kivimäki M, Frank P, Pentti J, et al. Obesity and risk of diseases associated with hallmarks of cellular ageing: a multicohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024;5(7):e454–e463. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(24)00087–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crane PA, Wilkinson G, Teare H. Healthspan versus lifespan: new medicines to close the gap. Nat Aging. 2022;2(11):984–988. doi: 10.1038/s43587-022-00318-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pool U Towards equitable healthspan extension: balancing innovations with the social determinants of health. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education. 2023;61(5): 213. doi: 10.1080/14635240.2023.2239082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng W, Huang X, Wang X, et al. Impact of multimorbidity patterns on outcomes and treatment in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J Open. 2024;4(2):oeae009. doi: 10.1093/ehjopen/oeae009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bode-Böger SM, Martens-Lobenhoffer J, Täger M, Schröder H, Scalera F. Aspirin reduces endothelial cell senescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334(4):1226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Z, Zhang F, Yang Z, et al. Low-dose aspirin promotes endothelial progenitor cell migration and adhesion and prevents senescence. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32(7):761–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung YR, Kim EJ, Choi HJ, et al. Aspirin Targets SIRT1 and AMPK to Induce Senescence of Colorectal Carcinoma Cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;88(4):708–719. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.098616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Lu J, Hou Y, Huang S, Pei G. Alzheimer’s Amyloid-β Accelerates Human Neuronal Cell Senescence Which Could Be Rescued by Sirtuin-1 and Aspirin. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022;16:906270. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.906270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408(6809):239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nayak A, Hayen A, Zhu L, et al. Legacy effects of statins on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020584. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu L, Bell KJL, Hayen A. Methods to address selection bias in post-trial studies of legacy effects were evaluated. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023;160:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson MR, Reid CM, Ames DA, et al. Feasibility of conducting a primary prevention trial of low-dose aspirin for major adverse cardiovascular events in older people in Australia: results from the ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) pilot study. Med J Aust. 2008;189:105–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ASPREE Investigator Group. Study design of ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE): a randomized, controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36: 555–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. ; ASPREE Investigator Group. Baseline characteristics of participants in the ASPREE (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:1586–93. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. ; ASPREE Investigator Group. Effect of aspirin on disability-free survival in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 379(16):1499–1508;2018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ernst ME, Broder JC, Wolfe R, et al. ; ASPREE Investigator Group. Health characteristics and aspirin use in participants at the baseline of the ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly – eXTension (ASPREE-XT) observational study. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2023;130:107231. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2023.107231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified MiniMental State (3M) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz S Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:721–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan J, Storey E, Murray AM, et al. ; ASPREE Investigator Group. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of the effects of aspirin on dementia and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2020;95(3):e320–e331. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfe R, Broder J, Chan A, et al. Expanded statistical analysis plan for legacy and long-term effects of aspirin in the ASPREE-XT observational follow-up study of participants in the ASPREE randomized trial. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023. Sep 14:2023.09.13.23295514. doi: 10.1101/2023.09.13.23295514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little RJ, Lewis RJ. Estimands, Estimators, and Estimates. JAMA. 2021;326(10):967–968. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. European Medicines Agency. ICH Harmonised Guideline e9(r1): Addendum on Estimand and Sensitivity Analysis in Clinical Trials. Updated July 30, 2020. Accessed January 27, 2025. E9 (R1) Step 5 addendum on estimands and Sensitivity Analysis in Clinical Trials to the guideline on statistical principles for clinical trials [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfe R, Broder JC, Murray AM, et al. Aspirin, cardiovascular events, and major bleeding in older adults: extended follow-up of the ASPREE trial. European Heart Journal. Accepted 7th July 2025. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia J, Ning Y, Chen M, et al. Biomarker Changes during 20 Years Preceding Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(8):712–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2310168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu L, Bell KJL, Nayak A, Hayen A. A methods review of posttrial follow-up studies of cardiovascular prevention finds potential biases in estimating legacy effects. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;131:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ASPREE Investigators. ASPREE Protocol Version 9 Date November 2014. Accessed on 06/29/2025 at https://aspree.org/usa/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2021/07/ASPREE-Protocol-Version-9_-Nov2014_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kent DM, Paulus JK, van Klaveren D, et al. The Predictive Approaches to Treatment effect Heterogeneity (PATH) Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(1):35 45. doi: 10.7326/M18-3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All individual participant data collected during the trial and post-trial, after de-identification, as well as the surveys and data dictionaries, are available via the ASPREE Safehaven immediately following publication and with no end date. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan have been published. Applicants are required to submit a request, with full access details available at www.aspree.org, in order to achieve the aims of a specific project or replicate the results provided here.