Abstract

A photoactivatable azidophenacyl group has been introduced into seven positions in the backbone of the 11 nucleotide invariant loop of U5 snRNA. By reconstituting depleted splicing extracts with reassembled U5 snRNP particles, molecular neighbors were assessed as a function of splicing. All cross-links to the pre-mRNA mapped to the second nucleotide downstream of the 5′ splice site, and formed most readily when the reactive group was at the phosphate between U5 positions 42 and 43 or 43 and 44. Both their kinetics of appearance and sensitivity to oligonucleotide inhibition suggest that these cross-links capture a late state in spliceosome assembly occurring immediately prior to the first step. A later forming, second cross-linked species is a splicing product of the first cross-link, suggesting that the U5 loop backbone maintains this position through the first step. The proximity of the U5 loop backbone to the intron’s 5′ end provides sufficient restrictions to develop a three-dimensional model for the arrangement of RNA components in the spliceosome during the first step of pre-mRNA splicing.

Keywords: azidophenacyl/cross-linking/reconstitution/snRNP/spliceosome

Introduction

The removal of an intron from mammalian pre-mRNA requires the formation of a spliceosome, a protein–RNA macromolecular machine. Once formed, this complex directs the in-line attack of the 2′-hydroxyl of the intron’s branch point adenosine on the reactive phosphate at the 5′ splice site (Moore and Sharp, 1993). The resulting reaction intermediates are the upstream exon with a free 3′-hydroxyl terminus, and a lariat structure containing the intron and the 3′ exon. In the second step, the free 3′-hydroxyl of the upstream exon makes an in-line attack on the reactive phosphate at the downstream intron–exon junction, generating an excised lariat intron and ligated exons (Moore and Sharp, 1993).

There are two varieties of spliceosome currently known in higher eukaryotes: the U2-type, containing small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) U1, U2, U4, U5 and U6; and the U12-type, containing analogous snRNPs U11, U12, U4atac and U6atac, but sharing the U5 snRNP (Tarn and Steitz, 1997). Each snRNP plays a specific role in the splicing process. The U1 (or U11) snRNP initially recognizes the 5′ splice site, while the U2 (or U12) snRNP recognizes the branch point region. U4 (or U4atac) chaperones the entry of U6 (or U6atac) along with its tri-snRNP partner, U5, into the spliceosome, and then hands it off to replace U1 (U11) at the 5′ splice site. Subsequent rearrangements produce interactions between U6 (U6atac) and U2 (U12) that form part of the spliceosomal active site. U5 is proposed to contact the 5′ exon just upstream of the 5′ splice site prior to the first splicing step and then maintain its hold, later aligning the ends of the exons for ligation in the second step (Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993; Umen and Guthrie, 1995; Chiara et al., 1997; O’Keefe and Newman, 1998; Maroney et al., 2000).

The U5 snRNP is an active central component of both the U2- and U12-type spliceosomes (Grabowski and Sharp, 1986; Frilander and Steitz, 2001), and has the same protein make-up (Will et al., 1999). The extraordinarily highly conserved U5 snRNP protein hPrp8p or p220 (Luo et al., 1999) contacts both the 5′ and 3′ splice sites in the pre-mRNA (Wyatt et al., 1992; Reyes et al., 1996; Chiara et al., 1997; Maroney et al., 2000). Other U5 proteins have been suggested to trigger U4/U6 unwinding (p200) and scan downstream of the branch point to identify the 3′ splice site (p116) (Liu et al., 1997; Laggerbauer et al., 1998; Kuhn et al., 1999; Staley and Guthrie, 1999; Kuhn and Brow, 2000).

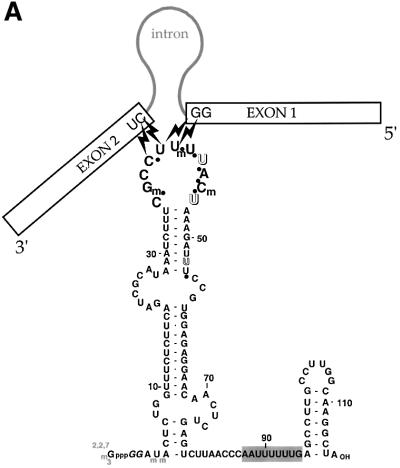

The U5 snRNA contains an 11 nucleotide loop that is conserved in length across all species, with the identity of nine nucleotides being universally conserved and the stem proximal nucleotides being pyrimidines (positions 36 and 46 in Figure 1; Szkukalek et al., 1995). Studies in vivo in HeLa cells and in vitro in yeast argue that the U5 loop sequence affects splice site selection, particularly for introns with non-ideal 5′ splice sites (Newman and Norman, 1991; Cortes et al., 1993). The highly conserved loop of the U5 RNA cross-links to the upstream exon prior to the first step and to both exons during the second step of splicing (Wyatt et al., 1992; Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993). While the same region of U5 surprisingly proved to be dispensable for splicing in HeLa nuclear extract (Ségault et al., 1999), in the yeast in vitro system some loop mutations prohibited the second step of splicing (O’Keefe et al., 1996; O’Keefe and Newman, 1998).

Fig. 1. U5 snRNA and generation of the azidophenacyl cross-linker. (A) The secondary structure of human U5A is shown with previously determined cross-links to the pre-mRNA indicated by lightning bolts (Wyatt et al., 1992; Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993). The highly conserved 11 nucleotide loop is in larger bold type. Black dots indicate phosphates modified to contain the azidophenacyl moiety. The 2′-O-methyl groups at positions 37, 41 and 45 of human U5, but not the pseudouridines (open letters), were present in the modified U5 snRNAs before introduction into the extract. The 5′-cap was not hypermethylated (gray) and two G nucleotides (italics) were added to enable transcription. (B) The azidophenacyl group adds to the single phosphorothioate linkage. The reactive sulfur atom of the resulting stable phosphorothioate triester is shown (bold), as is the photoactive azido group (italics).

Here, we have studied the positioning of the U5 snRNA in the human U2-type spliceosome by identifying molecular neighbors of the backbone of the invariant U5 loop. By site-specifically attaching an azidophenacyl group to a single chemically introduced phosphorothioate, we generated reconstituted U5 snRNPs containing a photoactivatable cross-linker in 7 of the 11 positions of the U5 loop. When added to HeLa nuclear extract depleted of U5 snRNPs, these modified U5 snRNAs surprisingly cross-linked not to the exons, but to the intron near the 5′ splice site of the pre-mRNA substrate. These results provide the basis for modeling the arrangement of RNAs during the first step of splicing in three dimensions.

Results

Construction of functional photoactivatable U5 snRNPs

We created a series of photoactivatable U5 snRNAs that would position the U5 invariant loop with respect to other components in the active spliceosome. We chose the azidophenacyl group as a cross-linking agent because its 10 Å length allows reaction with somewhat more distant molecular neighbors than zero-length agents such as 4-thiouridine (4thioU). The azidophenacyl group prefers nucleophiles and reacts with all four nucleotides (Chen et al., 1998). To place a single azidophenacyl group at the eight different positions indicated by dots on the backbone of U5 snRNA in Figure 1A, a three-piece ligation strategy was employed. We synthesized oligonucleotides possessing the three natural 2′-O-methyl modifications but containing one phosphorothioate linkage to which p-azidophenacyl bromide was coupled, yielding ≥90% stable phosphorothioate triester (Figure 1B and data not shown). Each modified oligonucleotide was then assembled into full-length U5 snRNA by three-piece ligation using a single DNA splint and DNA ligase (Moore and Sharp, 1992).

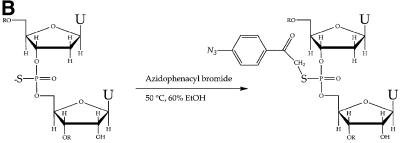

Modified U5 snRNAs were reconstituted with snRNP proteins that had been purified over an H20 anti-trimethyl guanosine cap antibody column and subsequently cleared of RNA on DE53 resin (Ségault et al., 1995). The resulting U5 core particles were introduced into HeLa nuclear extracts depleted of U5 snRNA by affinity chromatography (Lamm et al., 1991), but still containing U5-specific proteins (Ségault et al., 1995). Although some endogenous U5 snRNA remained in the extract (Figure 2, lane 2), measurable increases (4 ± 1-fold) in splicing activity were observed when the extract was supplemented with reconstituted snRNPs containing a full-length U5 transcript (lane 7) or any of the modified U5 snRNAs (lanes 3–10, compared with the mock-depleted extract in lane 1). Attaching the azidophenacyl group to the phosphate backbone at any of the eight positions tested had no measurable affect on the reconstitution of splicing activity.

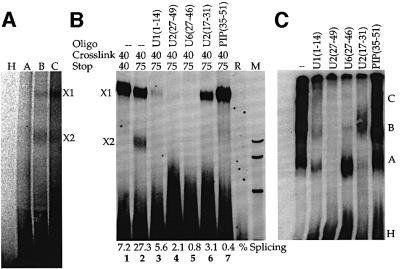

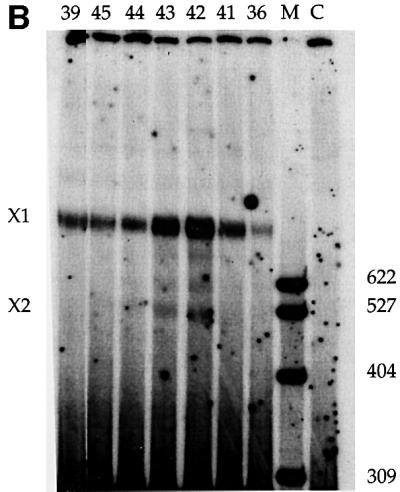

Fig. 2. (A) Photoactivatable U5 snRNAs function in splicing. Splicing activity was restored to a nuclear extract depleted of U5 snRNPs (Δ, lane 2) upon addition of 0.3 µM modified or unmodified (U5, lane 7) U5 snRNA reconstituted with Sm core proteins. Each U5 snRNA is indicated by the number of the nucleotide upstream of the modification (lanes 3–6 and 8–10). C shows a mock-depleted extract (lane 1) and R shows the PIP substrate (lane 11). M is a MspI marker lane. (B) Cross-linking efficiency varies with the position of the photoactivatable group. The reactions were as in (A), with cross-linking performed 60 min after the initiation of splicing.

Modified U5 snRNPs produce cross-links of varying intensity to pre-mRNA during splicing

Cross-links between the modified U5 snRNAs and molecular neighbors were generated after 60 min of splicing by excitation of the azidophenacyl group with 312 nm light. While many of the cross-links were to U5-specific proteins (data not shown), an RNA–RNA cross-link, X1, of variable intensity, was observed with the PIP pre-mRNA substrate (Figure 2B). X1 was strongest when the azidophenacyl group was immediately downstream of position 42 or 43 in the U5 invariant loop (called U5z42 or U5z43; Figure 1). Moving the cross-linker either 5′ or 3′ yielded weaker cross-links. A U5 snRNA with an azidophenacyl group downstream of position 54 reconstituted splicing, but produced no cross-links to the pre-mRNA (data not shown). Likewise, a 10- to 100-fold excess of an oligonucleotide containing positions 35–58 of U5 azidophenacyl modified at position 42 or 43 did not produce a cross-link in either U5-depleted extracts, U5-reconstituted extracts or normal extracts (data not shown). These and other controls argue strongly that the appearance of X1 is not due to a non-specific cross-linking event or a particular binding pocket for the azidophenacyl moiety.

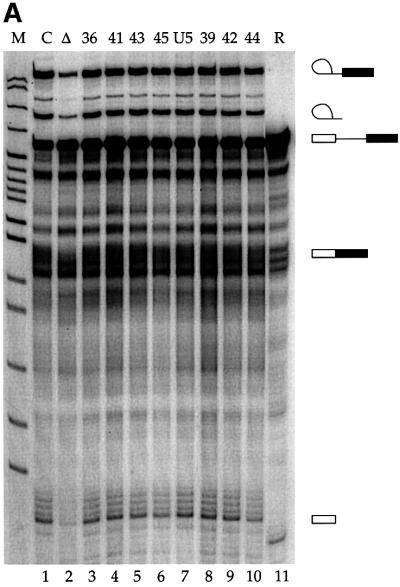

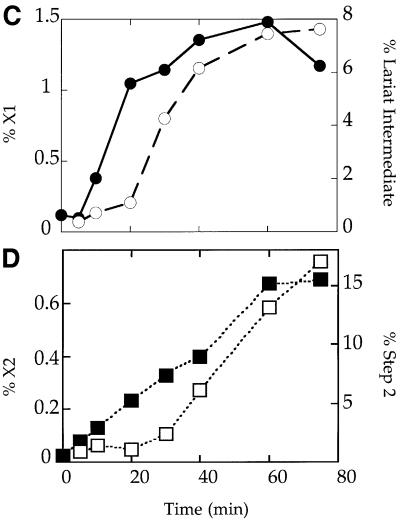

The cross-linked species are produced along the splicing pathway

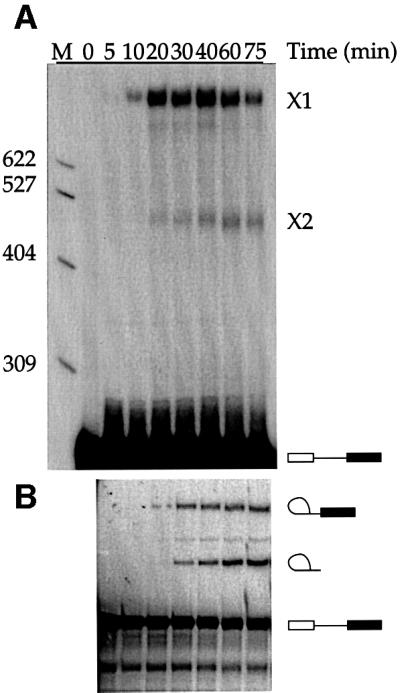

The time course of cross-link formation by U5z43 was examined relative to the progress of the splicing reaction (Figure 3). Cross-link X1 was weakly visible after 10 min and was maximal by 40 min (Figure 3A). Thus, the intensity of X1 correlates with the formation of splicing intermediates (Figure 3B and C). In contrast, the appearance of a weaker second cross-link, X2, immediately preceded the accumulation of second-step products (Figure 3B and D). While cross-link X1 does not form as early as some previously characterized U5-substrate cross-links (Wyatt et al., 1992; Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993; Reyes et al., 1996, 1999; Maroney et al., 2000), its kinetics suggest that it forms prior to the first step of splicing.

Fig. 3. Kinetics of cross-linking versus splicing. (A) Cross-links X1 and X2 were formed at various times (minutes) in reactions reconstituted with U5z43. (B) Splicing intermediates and products formed in the reactions shown in (A). (C and D) Quantitation of cross-link formation relative to the appearance of splicing intermediates and products. In the upper panel, %X1 (filled circles) = {(X1/(X1 + X2 + substrate) × 100} in the cross-linking gel (A) was compared at various times (minutes) to the %Step 1 (open circles) = {lariat intermediate/(lariat intermediate + lariat + substrate) × 100} in the splicing gel (B). In the lower panel, %X2 (filled squares) = {(X2/(X1 + X2 + substrate) × 100} in the cross-linking gel (A) was compared at various times (minutes) to the %Step 2 (open squares) = {lariat/(lariat intermediate + lariat + substrate) × 100} in the splicing gel (B).

To establish that cross-links X1 and X2 are generated in functional spliceosomes, we isolated cross-linked complexes (with U5z42) from native gels and resolved the RNAs on a 6% denaturing gel (Figure 4A). Cross-links X1 and X2 reproducibly appeared in spliceosomal complex C (with traces in B, perhaps due to the fragility of spliceosomes containing reconstituted U5 snRNPs), but not in A or H. Thus, these cross-links are specifically associated with active spliceosomes.

Fig. 4. Cross-links form in functional spliceosomes. (A) RNAs isolated from complexes A, B, C and H fractionated on a native gel like that shown in (C) were resolved on a denaturing gel. (B) Cross-linking with U5z43 is inhibited by blocking other snRNAs. Chased cross-linking reactions were performed in the presence of 2′-O-methyl oligo nucleotides complementary to U1, U2, U6 or PIP exon 1, as indicated. Below each lane, the percent splicing represents the fraction of substrate converted to intermediates and products. (C) Native gel of oligonucleotide-inhibited splicing reactions.

To define further the relationship of X1 to X2, we challenged the reconstituted extracts with 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides complementary to various snRNAs (Figure 4B and C), and examined the outcome when reactions cross-linked at 40 min were allowed to continue splicing for an additional 35 min. With no oligonucleotide, X2 increased relative to X1 (lanes 1 and 2), supporting the idea that X2 is a product of X1. In contrast, blocking either the U2 region that interacts with the intron branch site [U2(27–49)] or the U6 region that interacts with the 5′ splice site [U6(27–46)] completely inhibited splicing (Figure 4B, values below lanes) and prevented the formation of both X1 and X2 (lanes 4 and 5). While the PIP substrate can be spliced by a U1-independent pathway (Crispino et al., 1996), blocking 5′ splice site recognition by U1 in reconstituted extracts sometimes inhibited splicing (lane 3), but in extracts that spliced, X1 and X2 both appeared (data not shown). Additional 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides, analogous to those used to study the U12-dependent spliceosome (Frilander and Steitz, 2001), inhibited U2-dependent splicing later in the pathway. U2(17–31) targets the region of U2 that pairs with U6 to form helices Ia and Ib before the first step; consistent with the generation of some complex B (Figure 4C), X1 but not X2 appeared (lane 6). PIP(35–51) targets the 5′ exon (positions –5 to –21) and yielded all spliceosomal complexes, but little splicing (lane 7). Again, X1, but little X2, was formed.

We conclude that our cross-links represent distinct states along the normal splicing pathway. Specifically, cross-link X1 occurs subsequent to or concomitant with U6 interactions with the 5′ splice site and prior to the first step of splicing, whereas X2 is a splicing-dependent product of X1. This is consistent with the relative gel mobilities of X1 and X2, since normal splicing intermediates and products run faster than the pre-mRNA substrate on a 6% gel. It is expected that splicing intermediates and products of X1 should also run faster, as X2 does.

Locating the site of cross-linking

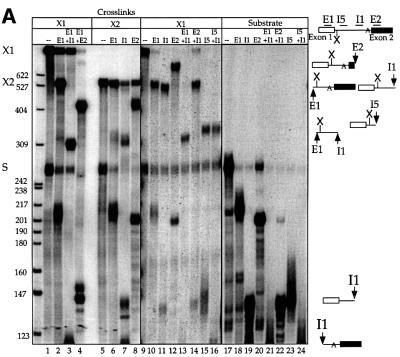

To narrow the region of covalent addition of U5z43 to the PIP splicing substrate, cross-links X1 and X2 were examined by RNase H analysis (Figure 5A). DNA oligonucleotides complementary to exons 1 (E1, lane 10) or 2 (E2, lane 12) or the intron (I1 and I5, lanes 11 and 15) all targeted X1 (lane 9) for cleavage, indicating that X1 contains the pre-mRNA. Mixing oligonucleotides I1 and E2 with X1 produced a cleaved cross-link product (lane 14) identical in size to that when I1 was used alone (lane 11), whereas a mixture of DNA oligonucleotides complementary to the intron (I1) and exon 1 (E1) produced from X1 a cleaved product (lane 13) that was shorter than that produced with I1 (lane 11). The location of the X1 cross-link was further narrowed to the 5′ end of the intron by the observation that a DNA oligonucleotide (I5) targeting an intron region upstream of I1 produced a shorter cross-linked product (lane 15 compared with 11) that was not further shortened when I1 was also present (lane 16). These results suggest that the cross-link is located very close to the 5′ splice site, within the first 22 nucleotides of the intron.

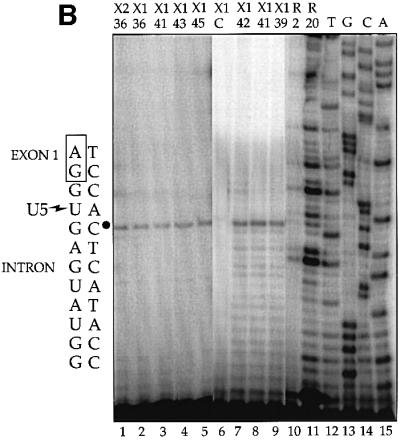

Fig. 5. Characterization and mapping of cross-links X1 and X2. (A) Purified X1 and X2 were subjected to RNase H treatment. The DNA oligonucleotides complementary to the pre-mRNA used individually or in combination were: E1 (positions 36–56); I1 (127–147); I5 (81–112); E2 (193–211); dashes, no oligo added. Reactions were performed on the PIP substrate alone (lanes 17–24) compared with X1 (lanes 1–4 and 9–16) and X2 (lanes 5–8) in two separate experiments (lanes 1–8 and 9–24). (B) Primer extension mapping of cross-links X1 and X2 on the PIP RNA. The number below X1 or X2 indicates the U5 modified position in the ∼2–10 fmol of cross-link analyzed (lanes 1–9); note that larger cross-linking reactions were used to generate signal for weaker cross-links. C is the mock control for X1 (lane 6); R is PIP RNA used as template at 2 and 20 fmol per reaction (lanes 10 and 11). The sequencing lanes (denoted TGCA; lanes 12–15) used 0.01 µg of PIP DNA. To the left is the DNA sequence, with a bullet indicating a stop one base prior to the U5 cross-link shown on the adjacent RNA sequence.

Additionally, the RNase H experiments confirmed previous deductions about the splicing state of the PIP RNA in the two cross-linked species. We deduce that cross-link X2 represents the intron–3′ exon intermediate since X2 was susceptible to cleavage in the presence of I1 and E2 (lanes 7 and 8), but not E1 (lane 6), whereas the uncross-linked substrate (marked S) that co-purified with X2 was targeted by E1 (compare lanes 2, 6 and 18) as well as by I1 (lanes 7 and 19) and E2 (lanes 8 and 20). Also, cleavage of X1 within exon 1 close to the 5′ splice site generated a cleaved product (lane 2) with similar mobility to X2 (lane 5), suggesting that X2 contains the linearized lariat intermediate; our reconstituted extracts do contain considerable debranching activity (data not shown). We conclude that X1 is a cross-link to the pre-mRNA and that X2 is generated from X1 by the first step of splicing.

Finally, to pinpoint the cross-linked site(s), reverse transcription analyses were performed on purified X1 and X2 using a 5′-32P-labeled DNA oligonucleotide complementary to nucleotides 76–97 of the PIP intron (Figure 5B). Comparison to a DNA sequencing ladder (lanes 12–15) shows a strong stop three nucleotides downstream of the 5′ splice site. Remarkably, this same reverse transcriptase stop was seen for X1 generated with each of the modified U5 snRNAs (lanes 2–5 and 7–9), indicating that only the +2 intron position is available to an azidophenacyl group attached to any position of the U5 loop backbone. Cross-link X2 for U5z36 mapped to the same position (lane 1), further supporting the conclusion that X2 is a splicing product of X1. Each of these stops was at least five times above background, i.e. the value at the +3 position for gel slices of the same mobility as X1 (lane 6) or X2 (not shown) from mock cross-linking reactions. Neither the primer alone nor any materials used in the analyses produced a stop at this position (data not shown), nor was this a major stop for the pre-mRNA substrate alone (lanes 10 and 11). The surprising finding that the azidophenacyl group in each of positions 36–45 of the conserved U5 loop cross-linked to the same site implies that adjacent pre-mRNA residues are either out of range of the 10 Å cross-linker or occluded from cross-linking by proteins.

Modeling the first step of splicing

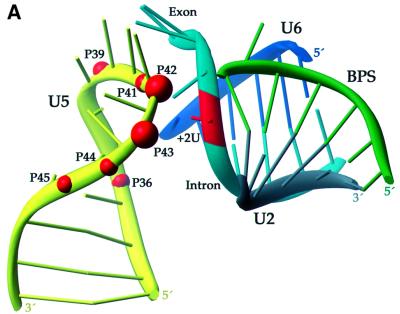

Our results add significantly to current data on the positioning of U5 within the active site of the spliceosome. To explore the implications of these new constraints, we built a three-dimensional model of the active site of the spliceosome during the first step of splicing, using the programs CNS (Brunger et al., 1998) and Ono (Jones et al., 1991). First, we used CNS to create a model of the U5 stem–loop. We modeled the stem as an A form duplex using Watson–Crick pair torsion angles, distance and planar restraints. We also included loose restraints for the loop region to favor C2′-endo sugar pucker torsion angles, and the arbitrary restriction that G37 and C45 (see Figure 1A) should pair. Next, crude models were calculated using the distance geometry algorithm in CNS. Three reasonable starting structures were then refined using the same set of restraints in a simulated annealing protocol in CNS. The most energetically stable structure, which was heated to 5000K for 1000 ps and slow cooled, was selected from ∼100 candidates.

To refine the U5 stem–loop structure, this molecule was annealed again, adding a weak distance constraint: for residues 38–43, the C6 atoms were optimized to be 3.5 Å away from each neighboring base, but were allowed a range of 2.5–7.5 Å. The solutions were biased toward more base stacking in the loop region, as had been seen for other large loop RNA structures (Szewczak et al., 1993; Correll et al., 1997). Eight of ∼50 structures were found to be reasonable when compared with 10 large loops (≥7 nt) from rRNA (Ban et al., 2000). The structure that best accommodated all known cross-linking data was then selected and assembled along with the U2–branch point sequence (BPS) and the U6–5′ splice site helices using the program Ono (Jones et al., 1991).

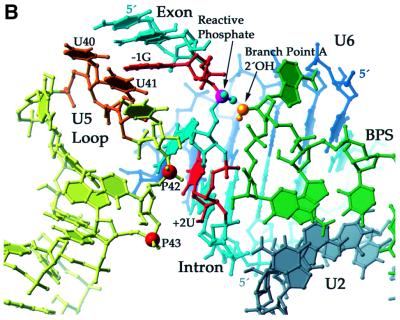

Our model for the first step of splicing (Figure 6) proposes that the bases face out on one side of the U5 stem–loop with the backbone on the other. The 5′ splice site of the substrate is positioned such that the exon approaches the base side of the U5 loop with the –1G in close proximity to the uracil bases 40 and 41. The intron faces the backbone side of the U5 loop with the functional groups of +2U within 10 Å of the non-bridging phosphate oxygens 3′ to residues 42 and 43. Nucleotides 40–45 of U6 interact with the intron, away from the U5 loop: U6 positions 40–42 pair with intron positions +5 to +7 of the PIP substrate in an A form manner, while positions 43 and 44 form non-canonical pairs with intron residues +3 and +4. Thus, A45 is proximal to +2U of the intron, accounting for an observed 4thioU cross-link (Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993). The U2–BPS A form helix (nucleotides 33 to 38 of U2 and +92 to +98 of the PIP intron) is positioned such that the 2′-hydroxyl of A147 is in line for attack on the reactive phosphate at the 5′ splice site. The nucleophilic A is unstacked, consistent with the observation that its functional groups are required for the first step of splicing (Query et al., 1996) and with the crystal structure of a model BPS (Berglund et al., 2001). An additional restriction positions the phosphates of U2 A38 and U6 U40 ∼20 Å apart, allowing these nucleotides to pair to initiate formation of the U2–U6 helix III (Sun and Manley, 1995). Importantly, the four unpaired nucleotides upstream of the U2 sequence shown and downstream of the U6 sequence shown confer flexibility, enabling the formation of U2–U6 helix I (Madhani and Guthrie, 1992) and its positioning near the active site (not shown).

Fig. 6. Three-dimensional model of the first step of splicing. (A) Ribbon diagram of the conserved loop of U5 snRNA (yellow) with the modified phosphates (red balls) 42 and 43 juxtaposed ∼10Å (all other reactive phosphates ≤26Å) from +2U (red) of the intron of the PIP pre-mRNA (cyan or red). Also shown is U6 (dark blue), U2 (gray) and the intron BPS (green). (B) Atomic view of the active site using the same colors as in (A). U5 residues U40 and 41 (orange) cradle the last base of the exon (–1G, red; Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993). The nucleophilic 2′-hydroxyl (gold) of the bulged A is poised for in-line attack on the 5′ splice site’s reactive phosphate (magenta).

Discussion

Site-specific photocross-linking of the backbone of the conserved loop of reconstituted U5 snRNPs to position +2 of the intron has generated physical constraints that allow positioning of the U5 loop region with respect to other spliceosomal components during the first step of splicing. Inhibition of cross-link X1 when U6 is prevented from interacting with the 5′ splice site, but not when U2–U6 interactions are blocked (Figure 4), argues that this state occurs late in the assembly of the spliceosome, just prior to formation of the catalytic core. Our ability to chase the cross-link through the first step into a splicing intermediate that is also captured when cross-linking is performed at later times establishes that the proximity of the U5 loop to the 5′ intron region persists through cleavage at the 5′ splice site. All positions along the U5 loop backbone cross-linked only to intron position +2, albeit with varying intensity, suggesting a relative proximity for each position to this nucleotide. The conserved +2U plays a central role in splicing, as a 5′ splice site determinant (Newman et al., 1985; Newman and Norman, 1991; Cortes et al., 1993), in pairing with U1 (Zhuang and Weiner, 1986), by cross-linking to Prp8 (Reyes et al., 1999), by cross-linking to U6 (Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993), and potentially in pairing with the penultimate intron nucleotide during the second step of splicing (Collins and Guthrie, 1999).

The model has several attractive features: it is compatible with all previous cross-linking data on U5 and the 5′ splice site (Wassarman and Steitz, 1992; Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993; Newman et al., 1995), and it keeps the other snRNAs at some distance from the U5 loop but still allows in-line attack of the 2′-hydroxyl of the branch point A on the phosphodiester bond of the 5′ splice site.

A restricted view from the U5 loop

While the model in Figure 6 is only one of many possible solutions, it does provide a visual appreciation of how current data restrain the architecture and where flexibility remains in arranging components of the spliceosomal active site. The remarkable finding that cross-linkers placed at 7 of the 11 positions in the U5 conserved loop react with the same +2 position of the intron leads to several conclusions. First, a compact U5 loop structure is necessary. Thus, a base pair between G37 and C45 was introduced during modeling of the U5 loop. Similar interactions are present in the structures of other large RNA loops (Szewczak et al., 1993; Correll et al., 1997), and the highly conserved 2′-O-methylation of both these nucleotides (Szkukalek et al., 1995) could provide the stabilization necessary for pairing. A compact nature of the U5 loop could explain why insertions in this region can be more disruptive than deletions for the second step of splicing in yeast (O’Keefe and Newman, 1998), and why oligonucleotide pairing with the U5 loop requires 2,6-diaminopurine substitution to provide additional hydrogen bonding (Lamm et al., 1991). Despite its compact structure, the loop must undergo dynamic motion with respect to the intron in order to allow the more distant U5 loop phosphates to be within 10 Å of the +2 position some of the time. Since only the +2 position cross-links, while many other intron residues appear to be nearly as close, other positions may be occluded by proteins, such as Prp8 (see below).

Secondly, the relative intensities of cross-linking permit positioning of the phosphates of U5 residues 42 and 43 closest to the nearly invariant U residue at intron position +2. This skew orientation of the backbone of the 5′ splice site to the U5 loop served as a foundation on which to build the remainder of the active site as depicted in Figure 6. Specifically, U5 bases U40 and U41 point towards the exon immediately upstream of the 5′ splice site and cradle the last base of the exon (–1G). Thus, they may help orient the reactive phosphate for the first step of the splicing reaction. This interaction is likely to persist through both steps of the reaction since U5 is known to retain its hold on exon 1 (Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993; Newman et al., 1995; Teigelkamp et al., 1995; O’Keefe et al., 1996; O’Keefe and Newman, 1998).

Thirdly, with U5 in position on one side of the 5′ splice site, there remains sufficient room for U6 to pair with downstream 5′ splice site nucleotides and for the U2–BPS helix to approach from the side opposite U5 (see Figure 6). This positioning would allow known base-pairing interactions (helix I) between U2 and U6 (Madhani and Guthrie, 1992) if modeling of these snRNAs were extended. Moreover, the bulged A is unstacked from the U2–BPS helix; as presented in Figure 6, such an orientation allows room in the active site for proteins and RNA structures proposed to bind catalytic metals and direct the 2′-hydroxyl of the branch point A for cleavage (Sontheimer et al., 1997; Yean et al., 2000). Since functional groups on the nucleophilic A are required for the first step of splicing (Query et al., 1996), a protein may position it for attack. A direct role for spliceosomal proteins in catalysis remains unknown, and many parallels can be drawn between critical RNA elements of autocatalytic group II introns and the proteinaceous spliceosome (Boudvillain et al., 2000). The analog of the U5 loop in group II introns, called EBS1, can be functionally replaced by the U5 loop in a group II trans-splicing reaction (Hetzer et al., 1997). Our model therefore provides a framework to explore further the question of whether RNA is the primary catalyst in the spliceosome (Collins and Guthrie, 2000).

Does U5 base pair with the 5′ splice site?

The highly conserved nucleotides in the U5 snRNA loop have been proposed to pair with the 5′ splice site in several contexts. In yeast, compensatory mutations suggested a role for base pairing between U5 and exon sequences both in 5′ splice site selection and in exon ligation (Newman and Norman, 1991, 1992) when splicing was attenuated by a G to A transition at the 5′ end of the intron. Base pairing with U5 across the 5′ splice site has also been proposed for Leishmania (Xu et al., 2000). In HeLa cells, U5 snRNAs mutated within the conserved loop also affected 5′ splice site selection on attenuated pre-mRNAs, providing evidence for base pairing (Cortes et al., 1993). In HeLa nuclear extract, base pairing of the U5 loop across the 5′ splice site during the first step of splicing was proposed based on the formation of a psoralen cross-link between U41 of U5 and the intron between +6 and +21 (Wassarman and Steitz, 1992). This proposal is not compatible with our azidophenacyl cross-links since the U5 loop phosphates would be pointing away from the intron; moreover, an observed cross-link between a 4thioU at the –1 exon position to U40 and U41 of U5 (Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993) would not be expected since these residues would reside at opposite ends of the base-paired segment. Yet, the intron exits somewhere from the spliceosomal active site (Figure 6), and the reported psoralen cross-link with the U5 loop (Wassarman and Steitz, 1992) could represent an exit channel. Alternatively, it is possible that U5-5′ splice site pairing (Newman and Norman, 1991, 1992; Cortes et al., 1993) occurs transiently, after early U5 interactions with upstream 5′ exon elements and before the skewed position we propose for the U5 loop is assumed. It seems unlikely that base pairing across the 5′ splice site occurs concomitantly with the first step, since a phosphate in a helical conformation has very low reactivity (Soukup and Breaker, 1999), making catalysis difficult.

The required departure of U1

Early in spliceosome assembly, U1 forms a stable helix with the 5′ splice site including the +2 position. We propose that upon release of U1, the +2U intron residue becomes accessible to cross-linking by the azidophenacyl group on the backbone of the U5 snRNA loop. This is consistent with our observation that cross-link X1 forms just prior to the first step of splicing, similar to the kinetics of a cross-link between 4thioU at exon position –1 and U5 loop positions 40 and 41 (Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993).

Several lines of evidence argue that U5 is in the neighborhood of the 5′ splice site significantly earlier in the reaction (Maroney et al., 2000), but then undergoes a conformational transition (Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993). Specifically, cross-links between 4thioU at exon position –2 and U5 positions 40–43 form within 5 min after the initiation of splicing, and diminish by 30–45 min when splicing products begin to appear (Wyatt et al., 1992). Likewise, the U5 protein, p220, cross-links early (5–10 min) to 4thioU at intron position +2, and these cross-links also diminish by 45 min (Reyes et al., 1999). Thus, p220 appears to recognize the +2 intron position when U1 is still paired, and has been suggested to govern the unwinding of U4 and U6 (Kuhn et al., 1999; Kuhn and Brow, 2000), an essential step in the formation of U6–U2 interactions critical for catalysis. Another protein that forms a stable complex with p220, called p200 or Brr2, is a candidate for the U4/U6 helicase (Achsel et al., 1998; Laggerbauer et al., 1998; Raghunathan and Guthrie, 1998).

Evidence that the azidophenacyl U5-intron cross-link occurs only after U1 departs the 5′ splice site is that a 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotide that blocks U6 interaction with the 5′ splice site abolishes this cross-link (Figure 4). Although blocking U6 interaction with the 5′ splice site prevents U1 removal and the appearance of B complex, it has recently been suggested that B complex reflects stable association rather than initial recruitment of the tri-snRNP to the spliceosome (Maroney et al., 2000). Consistent with this idea are numerous U5 snRNA and Prp8 (p220) cross-links to pre-mRNA that have been detected prior to significant B complex formation (Wyatt et al., 1992; Newman et al., 1995; Reyes et al., 1999; Maroney et al., 2000).

U5 positioning and the first step of splicing

Since the azidophenacyl cross-link between the U5 loop and the pre-mRNA (X1) can be chased into a splicing intermediate containing the intron and the second exon (X2), the geometry fixed by the cross-link must be compatible with the first step of splicing. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that the cross-linked U5 is in position for the first trans-esterification reaction. We have modeled U5 bases U40 and U41 to comprise part of the pocket that orients the 5′ exon for the first step of splicing. The remarkable observation that the highly conserved U5 loop region is dispensable for the splicing of certain pre-mRNA substrates in HeLa nuclear extract (Ségault et al., 1999) suggests additional complexity. Perhaps other components of the U5 snRNP (e.g. p220) can substitute for this binding pocket in the absence of the conserved loop (Ségault et al., 1999). Alternatively, the removal of the conserved loop may slow a step in the splicing pathway, such as a chemical step, that is not rate limiting. In yeast, one U5 snRNA loop mutant allows both steps of splicing in vitro, but is lethal in vivo (O’Keefe et al., 1996). Other yeast U5 snRNA loop mutations inhibit the second step, suggesting that they render the 5′ exon binding pocket deficient in holding its ligand (Newman and Norman, 1992). We conclude that the U5 loop, though not absolutely essential, normally contributes to the first step of splicing.

The second step

We have not observed azidophenacyl cross-links between the U5 loop and the lariat product of splicing, perhaps because this species does not resolve away from substrate or degradation products on our gels. Alternatively, the positioning of the U5 loop during the second step of splicing may be incompatible with cross-linking. The active site for the first spliceosome reaction has been demonstrated to be stereochemically distinct from the second (Moore and Sharp, 1993). Collins and Guthrie (1999) have suggested that Prp8 (p220) mediates specific interactions between U6, the 5′ and the 3′ splice sites, an arrangement that might occlude the +2 position from reacting with an azidophenacyl group attached to the U5 loop backbone. The U5 snRNA, as well as Prp8, make numerous interactions with the 3′ splice site during the second step of splicing, probably requiring some reorganization relative to the 5′ splice site after the first step (Newman and Norman, 1992; Sontheimer and Steitz, 1993; Newman et al., 1995; Chiara et al., 1997; O’Keefe and Newman, 1998; Siatecka et al., 1999). In addition, another U5 protein, p116, has been proposed to scan from the branch point to the correct 3′ splice site (Liu et al., 1997). Thus, the positioning of the invariant U5 loop, as captured by cross-linking during the first step of the reaction, seems likely to change to accommodate the reactants of the second step of pre-mRNA splicing.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and transcriptions

Splicing substrate was generated from the PIP7.A w/ globin enhancer (PIP) plasmid (a gift from M.Garcia-Blanco) by inserting a 30 nucleotide enhancer from the mouse IgG sequence into the PstI site in exon 2 (sequence available upon request), cut with HindIII and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase as described (Jamison et al., 1995). The template for transcription of full-length U5 contained a T7 promoter with two G residues inserted to initiate transcription, followed by the complete human U5A sequence terminating with a BglII site. It was created by inserting the PCR product using oligonucleotides (sequences available upon request) from a previously constructed plasmid (Cortes et al., 1993) into a SmaI-cut pSp64 plasmid. To generate the 5′ fragment of U5A snRNA for ligation, a construct (pU51–34HH) was built containing a T7 promoter, two G residues, the first 34 nucleotides of U5 followed by a hammerhead ribozyme sequence that self-cleaves after the 34th nucleotide (Grosshans and Cech, 1991), and an EcoRI site. To generate the 3′ fragment of U5, a second construct (pU558–116) was built containing a T7 promoter, the U5 sequence starting from G58 to the 3′ end, and a BglII site. All three U5 constructs (1 µg/10 µl) were transcribed using T7 polymerase (1 U/µl; gifts from J.Doudna and S.Strobel) in 40 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM ATP, CTP, UTP and 0.3–0.6 mM GTP, 10 mM spermidine, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 1.5–2.5 h. Transcription of the full-length U5 plasmid and pU51–34HH was performed with or without a 6- to 20-fold excess over GTP of diguanosine triphosphate (Amersham) to yield RNA with the desired 5′ end, while that with pU558–116 contained a 10- to 20-fold excess of guanosine 5′-monophosphate to initiate transcription. For pU51–34HH, the Mg2+ concentration was increased to 15 mM after 2.5 h and the temperature increased to 50°C for 30 min to ensure efficient self-cleavage at the 3′ end of the RNA. RNA products were purified on a 10% denaturing gel.

Site-specifically modified U5 snRNAs

A series of oligonucleotides representing U5A positions 35–58 was synthesized (Keck facility, Yale University) with a single phosphorothioate linkage downstream of position 36, 39, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 or 54 and a deoxyribose immediately upstream of the phosphorothioate (unless a 2′-O-methyl group was present; Figure 1) to prevent the phosphorothioate triester from undergoing rapid hydrolysis (Gish and Eckstein, 1988). The p-azidophenacyl group was incorporated in the dark or in dim light using amber tubes (USA Scientific) by incubating 1 nmol of each oligonucleotide with 5 µmol of p-azidophenacyl bromide in 60% ethanol, 50 mM Na phosphate pH 6.6 at 50°C for 4 h (Musier-Forsyth and Schimmel, 1994). The reactions were quenched with 1 vol. of 10 mM Tris pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA and 250 mM NaCl, extracted with 2 vols of PCA (phenol:CHCl3:isoamyl alcohol, 50:49:1), and precipitated with 3 vols of ethanol and 20 µg of glycogen. The resulting modified oligonucleotide was then phosphorylated at its 5′ end with 50 U of polynucleotide kinase (USB) in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 38 nmol ATP and 15 µCi of [γ-32P]ATP. U51–34 RNA (1.4 nmol) was treated with 50 U of polynucleotide kinase in 50 mM MES pH 6.0, 0.07% mercaptoethanol, 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.4 mM ATP to remove the 3′ cyclic phosphate (Cameron and Uhlenbeck, 1977). These reactions were heated to 95°C for 1 min, combined with 1.4 nmol of U558–116 RNA and 1 nmol of a single-stranded DNA splint (sequence available upon request) and allowed to cool in the heat block from ∼70 to 30°C over 20 min. The RNAs were then ligated using 3–600 U of DNA ligase (gifts from T.Griffin and S.Strobel) in 20 mM Tris, 10 mM MES pH 7.0, 1 mM DTT, 0.015% mercaptoethanol, 1.4 mM ATP, 7.5 mM MgCl2 and 80 U of RNase inhibitor (Roche) for 4 h at room temperature (Moore and Sharp, 1992). After proteinase K treatment, extraction with PCA and ethanol precipitation, the ligated RNAs were resolved on an 8% denaturing gel, yielding 20–30% full-length modified U5 snRNA (data not shown).

Preparation of snRNP core proteins and depleted extracts

Core proteins were obtained essentially as described using the H20 antibody (generous gift of R.Lührmann) bound to protein A–Sepharose, followed by purification over DE53 resin (Ségault et al., 1995). HeLa nuclear extracts depleted of U5 snRNAs were also prepared as described (Lamm et al., 1991; Ségault et al., 1995) using a biotinylated oligo nucleotide complementary to the U5 conserved loop [5′-BBBBUZ GUZZZZGGCGBBBBdT-3′, where B is Bioteg (Glen Research), Z is 2,6-diaminopurine, and all nucleotides are 2′-O-methylribose, except for dT].

Reconstitution of U5-depleted extracts for splicing and cross-linking

After the modified U5 snRNA was heated at 95°C for 30 s in amber tubes in 2 µl of 5 mM MES pH 6.0, 0.5 mM EDTA, 6.5 µl of cold solution containing 6.5 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1.2 mM ATP, 5.9 mM MgCl2, 12 mM KCl, 2.3 mM DTT, 1.2% glycerol, 1 µg of tRNA and 20 U of RNase inhibitor (Roche) were added and the tubes immediately placed on ice. Purified core proteins (0.5–1.5 µg/5–10 pmol U5 in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA) were added and the samples incubated at 30°C for 10 min. Nuclear extract (30–40% final volume), creatine phosphate and KCl were then added (11 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 0.5 mM ATP, 2.6 mM MgCl2, 37 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 8.5% glycerol, 1 µg of tRNA and 20 U of RNase inhibitor/15 µl final reaction volume) and incubated on ice for 20 min. For inhibited reactions, 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotides (10–20 µM) were added and incubated at 30°C for 10 min. Splicing was initiated by the addition of substrate and 3′-dATP (USB) (0.1 mM; to minimize polyadenylation activity) at 30°C. Samples for cross-linking were placed in a microtiter plate on ice, covered with a gel glass plate, placed in a Stratalinker (Stratagene) ∼5 cm from the 312 nm light source, and irradiated for 2 min (∼400 mJ). Samples were treated with 20 µl of 5 mg/ml proteinase K in 50 mM EDTA, 1% SDS for 30 min at 37°C, extracted with PCA, 170 µl of TEN (10 mM Tris pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25 M NaCl) and 20 µg glycogen, and then precipitated with 600 µl of ethanol. Splicing reactions were resolved on a 12% denaturing gel or a 4% native gel, and cross-linked samples on a 6% denaturing gel.

RNase H analysis

Cross-linked bands were excised from a wet gel and either extracted in 400 µl of TEN or electro-eluted using an Elutrap system (Schleicher & Schuell) into 400 µl of 1× TBE twice for 2 h each, and then ethanol precipitated in the presence of 20 µg of glycogen. The dried pellets were dissolved in 6 µl of 2× RNase H buffer (40 mM Tris pH 7.5, 20 mM MgCl2, 200 mM KCl, 0.2 mM DTT, 10% sucrose) and 10–100 pmol of DNA oligonucleotides complementary to different regions of the PIP substrate. The samples were heated to 95°C and allowed to cool at room temperature for 20 min. One unit of RNase H (Pharmacia) in 5 µl of 50 mM DTT, 20 U of RNase inhibitor and 0.5 µg of tRNA were then added, incubated at 37°C for 1 h, treated with proteinase K, extracted with PCA and precipitated with ethanol as described above. Samples were resolved on a 6% denaturing gel.

Mapping of cross-linked sites

Cross-linked RNAs were purified and precipitated as described above. Pellets were taken up in 6 µl of hybridization buffer (2 mM MES pH 6.0, 667 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA) containing 105–106 c.p.m. of 5′-32P-labeled, gel-purified DNA primer complementary to intron positions 76–97 of the PIP splicing substrate, heated to 95°C for 1 min and allowed to cool on the bench for 20 min. After addition of 14 µl of reverse transcription mix [12 U of AMV reverse transcriptase (Roche), 3.75 mM DTT, 0.5 mM each dNTP, 10 mM MgCl2], the reactions were incubated at 50°C for 45 min, treated with proteinase K, extracted with PCA and precipitated as above.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Therese Yario for assistance; Reinhard Lührmann for his gift of the H20 antibody and the hospitality of his laboratory; Cindy Will and Irene Öcher for help in preparing core proteins; Scott Strobel, Tom Griffin and Jennifer Doudna for gifts of DNA ligase and T7 RNA polymerase; Mariano Garcia-Blanco for the gift of the PIP construct; Alex Szewczak and Joe Ippolito for help in modeling the active site; and Lara Weinstein, Leo Otake, Mikko Frilander and Alex Szewczak for critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM26154 to J.A.S. and by National Research Service Award GM17991 to T.S.M. J.A.S. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Achsel T., Ahrens,K., Brahms,H., Teigelkamp,S. and Lührmann,R. (1998) The human U5-220kD protein (hPrp8) forms a stable RNA-free complex with several U5-specific proteins, including an RNA unwindase, a homologue of ribosomal elongation factor EF-2, and a novel WD-40 protein. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 6756–6766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban N., Nissen,P., Hansen,J., Moore,P.B. and Steitz,T.A. (2000) The complete atomic structure of the large ribosomal subunit at 2.4 Å resolution. Science, 289, 905–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund J.A., Rosbash,M. and Schultz,S.C. (2001) Crystal structure of a model branchpoint–U2 snRNA duplex containing bulged adenosines. RNA, 7, 682–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudvillain M., de Lencastre,A. and Pyle,A.M. (2000) A tertiary interaction that links active-site domains to the 5′ splice site of a group II intron. Nature, 406, 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron V. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (1977) 3′-phosphatase activity in T4 polynucleotide kinase. Biochemistry, 16, 5120–5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.L., Nolan,J.M., Harris,M.E. and Pace,N.R. (1998) Comparative photocrosslinking analysis of the tertiary structures of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis RNase P RNAs. EMBO J., 17, 1515–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara M.D., Palandjian,L., Kramer,R.F. and Reed,R. (1997) Evidence that U5 snRNP recognizes the 3′ splice site for catalytic step II in mammals. EMBO J., 16, 4746–4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C.A. and Guthrie,C. (1999) Allele-specific genetic interactions between Prp8 and RNA active site residues suggest a function for Prp8 at the catalytic core of the spliceosome. Genes Dev., 13, 1970–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C.A. and Guthrie,C. (2000) The question remains: is the spliceosome a ribozyme? Nature Struct. Biol., 7, 850–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll C.C., Freeborn,B., Moore,P.B. and Steitz,T.A. (1997) Metals, motifs, and recognition in the crystal structure of a 5S rRNA domain. Cell, 91, 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes J.J., Sontheimer,E.J., Seiwert,S.D. and Steitz,J.A. (1993) Mutations in the conserved loop of human U5 snRNA generate use of novel cryptic 5′ splice sites in vivo. EMBO J., 12, 5181–5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispino J.D., Mermoud,J.E., Lamond,A.I. and Sharp,P.A. (1996) Cis-acting elements distinct from the 5′ splice site promote U1-independent pre-mRNA splicing. RNA, 2, 664–673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frilander M.J. and Steitz,J.A. (2001) Dynamic exchanges of RNA interactions leading to catalytic core formation in the U12-dependent spliceosome. Mol. Cell, 7, 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gish G. and Eckstein,F. (1988) DNA and RNA sequence determination based on phosphorothioate chemistry. Science, 240, 1520–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski P.J. and Sharp,P.A. (1986) Affinity chromatography of splicing complexes: U2, U5, and U4 + U6 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles in the spliceosome. Science, 233, 1294–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans C.A. and Cech,T.R. (1991) A hammerhead ribozyme allows synthesis of a new form of the Tetrahymena ribozyme homogeneous in length with a 3′ end blocked for transesterification. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 3875–3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer M., Wurzer,G., Schweyen,R.J. and Mueller,M.W. (1997) Trans-activation of group II intron splicing by nuclear U5 snRNA. Nature, 386, 417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison S.F., Pasman,Z., Wang,J., Will,C., Lührmann,R., Manley,J.L. and Garcia-Blanco,M.A. (1995) U1 snRNP–ASF/SF2 interaction and 5′ splice site recognition: characterization of required elements. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 3260–3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zao,J.-Y., Cowan,S.W. and Kjeldgaard,M. (1991) Improved methods for the building of protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A, 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn A.N. and Brow,D.A. (2000) Suppressors of a cold-sensitive mutation in yeast U4 RNA define five domains in the splicing factor prp8 that influence spliceosome activation. Genetics, 155, 1667–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn A.N., Li,Z. and Brow,D.A. (1999) Splicing factor Prp8 governs U4/U6 RNA unwinding during activation of the spliceosome. Mol. Cell, 3, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laggerbauer B., Achsel,T. and Lührmann,R. (1998) The human U5-200kD DEXH-box protein unwinds U4/U6 RNA duplexes in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 4188–4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm G.M., Blencowe,B.J., Sproat,B.S., Iribarren,A.M., Ryder,U. and Lamond,A.I. (1991) Antisense probes containing 2-aminoadenosine allow efficient depletion of U5 snRNP from HeLa splicing extracts. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 3193–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.R., Laggerbauer,B., Lührmann,R. and Smith,C.W. (1997) Crosslinking of the U5 snRNP-specific 116-kDa protein to RNA hairpins that block step 2 of splicing. RNA, 3, 1207–1219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H.R., Moreau,G.A., Levin,N. and Moore,M.J. (1999) The human Prp8 protein is a component of both U2- and U12-dependent spliceosomes. RNA, 5, 893–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani H.D. and Guthrie,C. (1992) A novel base-pairing interaction between U2 and U6 snRNAs suggests a mechanism for the catalytic activation of the spliceosome. Cell, 71, 803–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroney P.A., Romfo,C.M. and Nilsen,T.W. (2000) Functional recognition of the 5′ splice site by U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP defines a novel ATP-dependent step in early spliceosome assembly. Mol. Cell, 6, 317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M.J. and Sharp,P.A. (1992) Site-specific modification of pre-mRNA: the 2′-hydroxyl groups at the splice sites. Science, 256, 992–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M.J. and Sharp,P.A. (1993) Evidence for two active sites in the spliceosome provided by stereochemistry of pre-mRNA splicing. Nature, 365, 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musier-Forsyth K. and Schimmel,P. (1994) Acceptor interactions in a class II tRNA synthetase: photoaffinity cross-linking of an RNA miniduplex substrate. Biochemistry, 33, 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman A. and Norman,C. (1991) Mutations in yeast U5 snRNA alter the specificity of 5′ splice-site cleavage. Cell, 65, 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman A.J. and Norman,C. (1992) U5 snRNA interacts with the exon sequences at 5′ and 3′ splice sites. Cell, 68, 743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman A.J., Lin,R.J., Cheng,S.C. and Abelson,J. (1985) Molecular consequences of specific intron mutations on yeast mRNA splicing in vivo and in vitro. Cell, 42, 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman A.J., Teigelkamp,S. and Beggs,J.D. (1995) snRNA interactions at 5′ and 3′ splice sites monitored by photoactivated crosslinking in yeast spliceosomes. RNA, 1, 968–980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe R.T. and Newman,A.J. (1998) Functional analysis of the U5 snRNA loop 1 in the second catalytic step of yeast pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J., 17, 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe R.T., Norman,C. and Newman,A.J. (1996) The invariant U5 snRNA loop 1 sequence is dispensable for the first catalytic step of pre-mRNA splicing in yeast. Cell, 86, 679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Query C.C., Strobel,S.A. and Sharp,P.A. (1996) Three recognition events at the branch-site adenine. EMBO J., 15, 1392–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan P.L. and Guthrie,C. (1998) RNA unwinding in U4/U6 snRNPs requires ATP hydrolysis and the DEIH-box splicing factor Brr2. Curr. Biol., 8, 847–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J.L., Kois,P., Konforti,B.B. and Konarska,M.M. (1996) The canonical GU dinucleotide at the 5′ splice site is recognized by p220 of the U5 snRNP within the spliceosome. RNA, 2, 213–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J.L., Gustafson,E.H., Luo,H.R., Moore,M.J. and Konarska,M.M. (1999) The C-terminal region of hPrp8 interacts with the conserved GU dinucleotide at the 5′ splice site. RNA, 5, 167–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ségault V., Will,C.L., Sproat,B.S. and Lührmann,R. (1995) In vitro reconstitution of mammalian U2 and U5 snRNPs active in splicing: Sm proteins are functionally interchangeable and are essential for the formation of functional U2 and U5 snRNPs. EMBO J., 14, 4010–4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ségault V., Will,C.L., Polycarpou-Schwarz,M., Mattaj,I.W., Branlant,C. and Lührmann,R. (1999) Conserved loop I of U5 small nuclear RNA is dispensable for both catalytic steps of pre-mRNA splicing in HeLa nuclear extracts. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 2782–2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siatecka M., Reyes,J.L. and Konarska,M.M. (1999) Functional interactions of Prp8 with both splice sites at the spliceosomal catalytic center. Genes Dev., 13, 1983–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer E.J. and Steitz,J.A. (1993) The U5 and U6 small nuclear RNAs as active site components of the spliceosome. Science, 262, 1989–1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer E.J., Sun,S. and Piccirilli,J.A. (1997) Metal ion catalysis during splicing of premessenger RNA. Nature, 388, 801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup G.A. and Breaker,R.R. (1999) Relationship between internucleotide linkage geometry and the stability of RNA. RNA, 5, 1308–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley J.P. and Guthrie,C. (1999) An RNA switch at the 5′ splice site requires ATP and the DEAD box protein Prp28p. Mol. Cell, 3, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.S. and Manley,J.L. (1995) A novel U2–U6 snRNA structure is necessary for mammalian mRNA splicing. Genes Dev., 9, 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczak A.A., Moore,P.B., Chang,Y.L. and Wool,I.G. (1993) The conformation of the sarcin/ricin loop from 28S ribosomal RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 9581–9585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkukalek A., Myslinski,E., Mougin,A., Lührmann,R. and Branlant,C. (1995) Phylogenetic conservation of modified nucleotides in the terminal loop 1 of the spliceosomal U5 snRNA. Biochimie, 77, 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarn W.Y. and Steitz,J.A. (1997) Pre-mRNA splicing: the discovery of a new spliceosome doubles the challenge. Trends Biochem. Sci., 22, 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teigelkamp S., Newman,A.J. and Beggs,J.D. (1995) Extensive interactions of PRP8 protein with the 5′ and 3′ splice sites during splicing suggest a role in stabilization of exon alignment by U5 snRNA. EMBO J., 14, 2602–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umen J.G. and Guthrie,C. (1995) A novel role for a U5 snRNP protein in 3′ splice site selection. Genes Dev., 9, 855–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman D.A. and Steitz,J.A. (1992) Interactions of small nuclear RNAs with precursor messenger RNA during in vitro splicing. Science, 257, 1918–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will C.L., Schneider,C., Reed,R. and Lührmann,R. (1999) Identification of both shared and distinct proteins in the major and minor spliceosomes. Science, 284, 2003–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt J.R., Sontheimer,E.J. and Steitz,J.A. (1992) Site-specific cross-linking of mammalian U5 snRNP to the 5′ splice site before the first step of pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev., 6, 2542–2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Liu,L. and Michaeli,S. (2000) Functional analyses of positions across the 5′ splice site of the trypanosomatid spliced leader RNA: implications for base-pair interaction with U5 and U6 snRNAs. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 27883–27892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yean S.-L., Wuenschell,G., Termini,J. and Lin,R.-J. (2000) Metal ion coordination by U6 snRNA contributes to catalysis in the spliceosome. Nature, 408, 881–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y. and Weiner,A.M. (1986) A compensatory base change in U1 snRNA suppresses a 5′ splice site mutation. Cell, 46, 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]