Abstract

Background

To compare the real-world efficacy and safety of bispecific antibodies (BsAbs, PD-1/CTLA-4) versus PD-1 inhibitors (ICIs), each combined with platinum-based chemotherapy ± bevacizumab, as first-line treatment for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer (p/r/m CC).

Methods

In our single-center retrospective matched cohort study, 121 patients treated between January 2021 and February 2025 were recruited. They were divided into two groups: the bispecific antibody combination group and the PD-1 inhibitor combination group. After propensity score matching (PSM, 1:1, caliper = 0.2), early response to treatment, survival outcomes, and treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were assessed. Subgroup analyses, prognostic analyses, and sensitivity analyses were also conducted.

Results

After PSM, 86 patients were analyzed (43 per group). The median follow-up duration was 20.8 months (interquartile range [IQR], 12.1–27.1 months). Early response assessment after two treatment cycles showed no significant difference between the BsAb-Combo and PD-1i-Combo groups (ORR 60.5% vs. 51.2%, p = 0.385; DCR 95.3% vs. 97.7%, p = 1.000). The mPFS was 20.2 months (95% CI, 18.6–not reached) in the BsAb-Combo group and 27.2 months (95% CI, 12.6–not reached) in the PD-1i-Combo group (HR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.44–1.75; log-rank p = 0.708). Grade 3–5 decreased white blood cell count was more frequent with PD-1i-Combo (37.2% vs. 9.3%, p = 0.002), whereas all-grade diarrhea was more common with BsAb-Combo (46.5% vs. 25.6%, p = 0.043). Subgroup analyses suggested that persistent/recurrent with distant metastases tended to benefit more from BsAb-Combo. In multivariate Cox models, ECOG Performance Status 2, lung metastasis, and ≥ 1-year maintenance therapy were independent prognostic factors for PFS.

Conclusion

BsAbs (PD-1/CTLA-4) combined with platinum-based chemotherapy ± bevacizumab demonstrated comparable efficacy and safety to PD-1 inhibitors and showed a favorable hazard-ratio trend. Hypothesis-generating signals observed in select subgroups, such as those with persistent or recurrent disease with distant metastases, warrant confirmation in prospective studies with extended follow-up.

Keywords: Cadonilimab, QL1706, PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific antibody, Cervical cancer, Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) is one of the most common cancers in women, and its morbidity and mortality rank fourth among female malignancies [1]. Persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer (p/r/m CC) is a refractory and symptomatic condition, and the purpose of current treatment is to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life [2]. Chemotherapy is one of the most commonly used methods for treating advanced or recurrent cervical cancer [3].

Based on the GOG-204 trial, the combination of cisplatin and paclitaxel has been established as the standard first-line chemotherapy regimen for r/m CC [4]. The GOG-240 study further showed that the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy in the first-line setting provides a survival benefit [5]. At present, immunotherapy is gradually being incorporated. Three major phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have reported results on first-line immunotherapy for advanced cervical cancer: KEYNOTE-826 [6], BEATcc [7], and COMPASSION-16 [8]. Accordingly, these three immunotherapy-based combination strategies have been endorsed as Grade I recommendations for first-line treatment of advanced cervical cancer in the guidelines of the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO).

Pembrolizumab and Cadonilimab (AK104) have been approved by the FDA and the National Medical Products Administration (China), respectively, in the treatment of advanced cervical cancer, which demonstrated the fast development and great prospect of immunotherapies in CC [9]. It is worth noting that an increasing number of bispecific antibodies are being applied in clinical practice.

Cadonilimab and QL1706 are both classified as PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific antibodies (BsAbs), designed to simultaneously block two distinct immune checkpoints and enhance antitumor immunity. QL1706 is a dual-functional bispecific antibody constructed by combining iparomlimab (anti-CTLA-4) and tuvonralimab (anti-PD-1) [10]. Unlike conventional PD-1 monoclonal antibodies, these bispecific agents also target CTLA-4, potentially offering enhanced antitumor efficacy through dual checkpoint blockade. In addition to PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecifics, other BsAbs have been developed to target complementary pathways involved in tumor immune evasion. Ivonescimab (AK112), a tetravalent bispecific antibody targeting PD-1 and VEGF-A [11], has been demonstrated to significantly improve progression-free survival (PFS) compared with pembrolizumab in previously untreated patients with advanced PD-L1-positive non-small cell lung cancer in a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study conducted in China [12].

In the published data of the three-phase clinical trials comparing them with standard treatment, the mPFS was 12.7 months for cadonilimab plus platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab and 10.4 months for the pembrolizumab combination group. The results of the phase III study (NCT05446883) investigating QL1706 in combination with chemotherapy±bevacizumab as first-line treatment for advanced cervical cancer have not yet been published. So far, in the absence of head-to-head comparisons, the choice between one of the above recommended combinations has mainly relied on non-objective considerations. Moreover, comparative data on bispecific antibodies versus PD-1 inhibitors in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy±bevacizumab as first-line treatment for p/r/m CC are still insufficient, particularly in real-world settings.

Therefore, our study aims to address this gap by employing a matching method to control for confounding bias, comparing the efficacy and safety of different combination regimens in real-world patients with advanced cervical cancer, and exploring potential subgroups that may derive significant survival benefits.

Patients and methods

Patient criteria

This retrospective study included patients with p/r/m CC who received immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) with platinum-based chemotherapy±bevacizumab as first-line therapy in the Gynecology Radiation Oncology Department of Jiangsu Cancer Hospital between January 2021 and February 2025. This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (KY-2025-067). The requirement for informed consent was waived, as this was a retrospective cohort study.

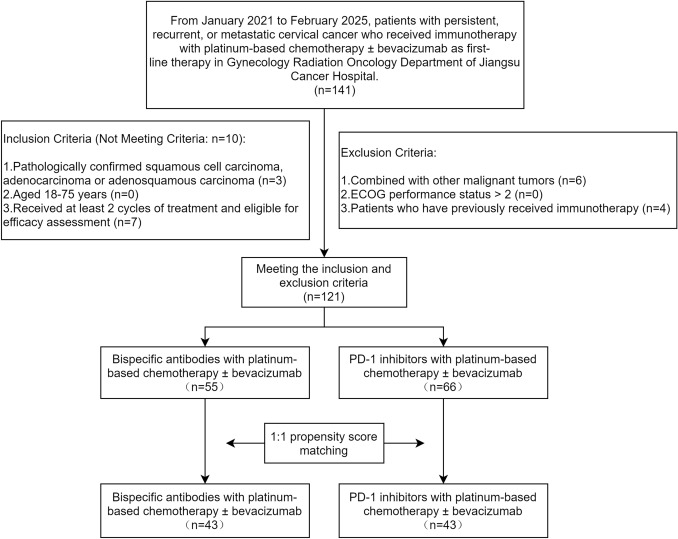

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined as follows: 1) Inclusion Criteria: 1. Pathologically confirmed squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma; 2. Aged 18–75 years; 3. Received at least 2 cycles of treatment and eligible for efficacy assessment. 2) Exclusion Criteria: 1. Combined with other malignant tumors; 2. ECOG performance status (ECOG PS) > 2; 3. Patients who have previously received immunotherapy. The patient flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

Treatment

Patients were stratified into the bispecific antibody combination group (BsAb-Combo group) and the PD-1 Inhibitor combination group (PD-1i-Combo group) according to the type of immunotherapy agents administered.

The standard chemotherapy regimen was the TP regimen, consisting of one of the following taxane-platinum combinations administered every 3 weeks (q3w): paclitaxel (135–175 mg/m2, intravenous infusion), paclitaxel liposome (135–175 mg/m2, intravenous infusion), or albumin-bound paclitaxel (260 mg/m2, intravenous infusion), combined with either cisplatin (70 mg/m2, intravenous infusion), nedaplatin (50 mg/m2, intravenous infusion), or carboplatin (area under the curve [AUC] 4, intravenous infusion). This regimen was administered with or without concurrent bevacizumab (15 mg/kg, intravenous infusion, every 3 weeks [q3w]).

Cadonilimab (Akeso Biopharma Inc., Zhongshan, China) was administered intravenously at 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks (q3w); QL1706 (Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) was administered intravenously at 5 mg/kg every 3 weeks (q3w).

All drug doses could be adjusted according to individual patient tolerance and clinical conditions.

PD-1 inhibitors included camrelizumab (200 mg, every 3 weeks [q3w]), pembrolizumab (200 mg, every 3 weeks [q3w]), sintilimab (200 mg, every 3 weeks [q3w]), penpulimab (AK105, 200 mg, every 3 weeks [q3w]), tislelizumab (200 mg, every 3 weeks [q3w]), zimberelimab (GLS-010, 240 mg, every 3 weeks [q3w]), and serplulimab (HLX10, 4.5mg/kg, every 3 weeks [q3w]), among others.

Radiotherapy was administered at the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist, with treatment parameters individualized according to lesion characteristics (including metastatic/recurrent site, tumor volume, and adjacent organ constraints).

Response evaluation and follow-up

Patients were systematically followed at 3-month intervals for the first 2 years post-treatment completion, with final follow-up data censored in September 2025.

Early response evaluation was systematically performed after completion of two treatment cycles using pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with both non-contrast and contrast-enhanced sequences, together with chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans under identical enhancement protocols. Treatment response was classified as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD) according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1). The objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) were then calculated, defined respectively as (CR+PR) / N and (CR+PR+SD) / N, where N represents the total number of evaluable patients.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was PFS, which was defined as the time from the initiation of treatment to disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurs first. Secondary endpoints included ORR, DCR, safety, and OS, which was defined as the time from the initiation of treatment to death from any cause. Adverse events were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE 5.0) issued by the U.S. National Cancer Institute.

To evaluate the consistency of treatment effects across patient subsets, the following prespecified subgroups were examined: age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), hypertension (yes vs. no), pathological diagnosis (squamous cell carcinoma vs. adenocarcinoma), histologic grade (G1,G2,X vs. G3), ECOG PS (0 vs. 1 vs. 2), disease status (metastatic vs. persistent or recurrent with distant metastases vs. persistent or recurrent without distant metastases), lymph node metastasis (yes vs. no), lung metastasis (yes vs. no), pelvic cavity metastasis (yes vs. no), bone metastasis (yes vs. no), metastatic region count (single vs. multiple), bevacizumab use during the treatment (yes vs. no), radiotherapy for recurrence (yes vs. no) and maintenance therapy (yes vs. no).

A Cox proportional hazards model was fitted within each subgroup to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) between two groups. An interaction term (treatment×subgroup factor) was added to the multivariable Cox model to calculate the p for interaction; a two-sided p < 0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant interaction.

Statistical analysis

This study is a single-center retrospective matched cohort study. To reduce the interference of confounding factors, propensity score matching (PSM) was used. Based on the logistic regression model, the propensity scores of the two groups of patients were calculated. A 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching method (with a caliper set at 0.2) was applied without replacement. The baseline characteristics of the two groups before and after matching were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. The matching effect was assessed by calculating the standardized mean difference (SMD), with SMD < 0.1 considered as indicating good covariate balance.

Survival outcomes, including PFS and OS, were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between the two groups were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards models to identify independent prognostic factors associated with PFS and OS. Variables entered into the multivariate model were those with p < 0.1 in univariate analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

From January 2021 to February 2025, a total of 121 eligible patients (66 in the PD-1i-Combo group and 55 in the BsAb-Combo group) were included for further analysis. The median follow-up duration was 20.8 months (reverse Kaplan–Meier; IQR, 12.1–27.1 months). PFS events occurred in 39 and 18 patients, respectively, and OS events occurred in 26 and 8 patients, respectively.

A 1:1 PSM was conducted based on age, hypertension, pathological diagnosis, histologic grade, ECOG PS, disease status, lymph node metastasis, lung metastasis, pelvic cavity metastasis, bone metastasis, metastatic region count, bevacizumab use during the treatment, radiotherapy for recurrence, and maintenance therapy. Nearest neighbor matching without replacement was employed, with a caliper width set to 0.2 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score. Therefore, 43 pairs of patients were selected. The propensity score distribution was similar in both groups following the matching process (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the SMD of the matched covariates were all less than 0.1 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

A Mirror histograms displaying patient propensity scores, with matched cases highlighted. B Baseline covariate balance before and after PSM, assessed by standardized mean differences (SMD)

Table 1 summarizes baseline characteristics before and after PSM. After matching, the two groups were well balanced with no significant differences in clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 86)

| Before PSM, No.(%) | After PSM, No.(%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1i-combo group(n = 66) | BsAb-combo group(n = 55) | χ2 | p value | PD-1i-Combo group(n = 43) | BsAb-Combo group(n = 43) | χ2 | p value | |

| Age | 0.872 | 0.350 | 0.104 | 0.747 | ||||

| < 65 | 60(90.9) | 47(85.5) | 38(88.4) | 37(86.0) | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 6(9.1) | 8(14.5) | 5(11.6) | 6(14.0) | ||||

| Hypertension | 2.786 | 0.095 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 17(25.8) | 22(40.0) | 15(34.9) | 15(34.9) | ||||

| No | 49(74.2) | 33(60.0) | 28(65.1) | 28(65.1) | ||||

| Pathological diagnosis | 1.520 | 0.218 | 0.551 | 0.458 | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 61(92.4) | 47(85.5) | 40(93.0) | 38(88.4) | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 5(7.6) | 8(14.5) | 3(7.0) | 5(11.6) | ||||

| Histologic grade | 5.409 | 0.020 | 0.191 | 0.662 | ||||

| G1,G2,x | 45(68.2) | 26(47.3) | 26(60.5) | 24(55.8) | ||||

| G3 | 21(31.8) | 29(52.7) | 17(39.5) | 19(44.2) | ||||

| ECOG PS | 2.824 | 0.244 | 2.413 | 0.299 | ||||

| 0 | 15(22.7) | 12(21.8) | 7(16.3) | 11(25.6) | ||||

| 1 | 42(63.6) | 29(52.7) | 30(69.8) | 23(53.5) | ||||

| 2 | 9(13.6) | 14(25.5) | 6(14.0) | 9(20.9) | ||||

| Disease status | 2.170 | 0.338 | 1.048 | 0.592 | ||||

| Metastatic (FIGO 2018: IVB) | 26(39.4) | 15(27.3) | 17(39.5) | 14(32.6) | ||||

| Persistent or recurrent with distant metastases | 20(30.3) | 18(32.7) | 9(20.9) | 13(30.2) | ||||

| Persistent or recurrent without distant metastases | 20(30.3) | 22(40.0) | 17(39.5) | 16(37.2) | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.999 | 0.318 | 0.534 | 0.465 | ||||

| Yes | 52(78.8) | 39(70.9) | 33(76.7) | 30(69.8) | ||||

| No | 14(21.2) | 16(29.1) | 10(23.3) | 13(30.2) | ||||

| Lung metastasis | 0.993 | 0.319 | 0.081 | 0.776 | ||||

| Yes | 17(25.8) | 10(18.2) | 7(16.3) | 8(18.6) | ||||

| No | 49(74.2) | 45(81.8) | 36(83.7) | 35(81.4) | ||||

| Pelvic cavity metastasis | 0.341 | 0.559 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 43(65.2) | 33(60.0) | 14(32.6) | 14(32.6) | ||||

| No | 23(34.8) | 22(40.0) | 29(67.4) | 29(67.4) | ||||

| Bone metastasis | 1.253 | 0.263 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 12(18.2) | 6(10.9) | 6(14.0) | 6(14.0) | ||||

| No | 54(81.8) | 49(89.1) | 37(86.0) | 37(86.0) | ||||

| Metastatic region count | 1.993 | 0.158 | 0.419 | 0.518 | ||||

| Single | 24(36.4) | 27(49.1) | 20(46.5) | 23(53.5) | ||||

| Multiple | 42(63.6) | 28(50.9) | 23(53.5) | 20(46.5) | ||||

| Bevacizumab use during the treatment | 1.472 | 0.225 | 0.191 | 0.662 | ||||

| Yes | 24(36.4) | 26(47.3) | 19(44.2) | 17(39.5) | ||||

| No | 42(63.6) | 29(52.7) | 24(55.8) | 26(60.5) | ||||

| Radiotherapy for recurrence | 0.001 | 0.973 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 37(56.1) | 31(56.4) | 25(58.1) | 25(58.1) | ||||

| No | 29(43.9) | 24(43.6) | 18(41.9) | 18(41.9) | ||||

| Maintenance therapy | 3.497 | 0.061 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 49(74.2) | 32(58.2) | 28(65.1) | 28(65.1) | ||||

| No | 17(25.8) | 23(41.8) | 15(34.9) | 15(34.9) | ||||

Early response evaluation after 2 cycles of treatment

We analyzed the response evaluation of measurable relapsed/metastatic lesions between the two groups after 2 cycles of treatment (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in ORR ( 51.2% vs. 60.5%, p = 0.385) and DCR (97.7% vs. 95.3%, p = 1.000) between the PD-1i-Combo and BsAb-Combo groups. The distribution of individual response categories was likewise comparable: CR: 4.7% vs. 14.0%, p = 0.265; PR: 46.5% vs. 46.5%, p = 1.000; SD: 46.5% vs. 34.9%, p = 0.272; PD: 2.3% vs. 4.7%, p = 1.000.

Table 2.

Response evaluation after 2 cycles of treatment (N = 86)

| PD-1i-Combo group(n = 43)No.(%) | BsAb-Combo group(n = 43)No.(%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 2(4.7) | 6(14.0) | 0.265 |

| PR | 20(46.5) | 20(46.5) | 1.000 |

| SD | 20(46.5) | 15(34.9) | 0.272 |

| PD | 1(2.3) | 2(4.7) | 1.000 |

| ORR | 22(51.2) | 26(60.5) | 0.385 |

| DCR | 42(97.7) | 41(95.3) | 1.000 |

Notes: When more than 20% of the cells had an expected count < 5 or when the minimum expected count was < 1, Fisher’s exact test was applied instead of the chi-square test

Overall, the BsAb-Combo regimen showed a non-significant trend toward higher CR and ORR, but the early (2-cycle) tumor-response profiles were broadly similar between the two groups.

Efficacy

Before matching: Kaplan–Meier curves for PFS and OS were nearly superimposable between the two groups, with log-rank p of 0.727 and 0.829, respectively, indicating no significant difference (Fig. 3A; Fig. 3B). After 1:1 PSM, the balanced cohorts still showed overlapping survival patterns; PFS (log-rank p = 0.708) and OS (log-rank p = 0.767) remained statistically indistinguishable (Fig. 3C; Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for progression-free survival and overall survival before A, B and after C, D PSM

In the propensity score-matched cohort, the PD-1i-Combo group achieved an mPFS of 27.2 months (95% CI, 12.6–not reached), whereas the BsAb-Combo group recorded 20.2 months (95% CI, 18.6–not reached). At 12 and 24 months, the PFS rates were 67.5% and 50.1% for the former versus 70.5% and 44.9% for the latter.

For OS, the PD-1i-Combo group reached a median of 43.0 months (95% CI, 36.8–not reached), while the mOS in the BsAb-Combo group had not been reached at the data cut-off (95% CI, 23.2-not reached). The corresponding 12- and 24-month OS rates were 87.3% and 74.3% for PD-1i-Combo, compared with 95.0% and 59.8% for BsAb-Combo. These findings indicate comparable PFS between the two regimens and a numerically longer yet immature OS trend in the BsAb-Combo group, warranting continued follow-up.

Taken together, the absence of significant differences before and after matching suggests that the two combination regimens confer comparable survival benefits, and the findings are robust to adjustment for baseline confounders. However, the relatively short follow-up should also be acknowledged. Cadonilimab was first approved in mainland China on June 29, 2022, and QL1706 on September 30, 2024, leaving insufficient observation time for BsAb-treated patients, as reflected by the immature tail of the BsAb-Combo survival curve.

Safety

The overall safety of the two groups was similar (Table 3, Fig. 4). The most frequent TRAEs were anemia, decreased white blood cell count, decreased neutrophil count, and decreased platelet count, which occurred in more than half of patients, with the majority being grade 1–2. Rates of grade 3–5 toxicities were also generally similar, except for severe white blood cell count decrease, which was significantly more frequent in the PD-1i-Combo group (37.2% vs. 9.3%, p = 0.002). Conversely, all-grade diarrhea was more common in the BsAb-Combo group (46.5% vs. 25.6%, p = 0.043).

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events (N = 86)

| Adverse events | PD-1i-combo group(n = 43)No.(%) | BsAb-combo group(n = 43)No.(%) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | grade 3–5 | All grades | grade 3–5 | All grades | grade 3–5 | |

| Anemia | 34(79.1) | 6(14.0) | 33(76.7) | 6(14.0) | 0.795 | 1 |

| White blood cell count decreased | 29(67.4) | 16(37.2) | 25(58.1) | 4(9.3) | 0.372 | 0.002 |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 25(58.1) | 9(20.9) | 17(39.5) | 4(9.3) | 0.084 | 0.132 |

| Platelet count decreased | 23(53.5) | 2(4.7) | 19(44.2) | 1(2.3) | 0.388 | 1 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 18(41.9) | 0 | 20(46.5) | 0 | 0.664 | NA |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 14(32.6) | 1(2.3) | 14(32.6) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 14(32.6) | 1(2.3) | 13(30.2) | 0 | 0.816 | 1 |

| Hypokalaemia | 10(23.3) | 2(4.7) | 11(25.6) | 1(2.3) | 0.802 | 1 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13(30.2) | 1(2.3) | 13(30.2) | 1(2.3) | 1 | 1 |

| Pyrexia | 7(16.3) | 0 | 14(32.6) | 1(2.3) | 0.079 | 1 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 31(72.1) | 0 | 34(79.1) | 1(2.3) | 0.451 | 1 |

| Decreased appetite | 28(65.1) | 0 | 31(72.1) | 0 | 0.486 | NA |

| Rash and pruritus | 12(27.9) | 0 | 18(41.9) | 1(2.3) | 0.175 | 1 |

| Constipation | 17(39.5) | 0 | 22(51.2) | 0 | 0.279 | NA |

| Diarrhea | 11(25.6) | 0 | 20(46.5) | 0 | 0.043 | NA |

| Fatigue | 21(48.8) | 0 | 28(65.1) | 1(2.3) | 0.127 | 1 |

Notes: 1. NA: p value is not calculated because no events were observed in either group; 2. When more than 20% of the cells had an expected count < 5 or when the minimum expected count was < 1, Fisher’s exact test was applied instead of the chi-square test.

Fig. 4.

Incidence of TRAEs between the PD-1i-Combo and BsAb-Combo groups, with pairwise comparisons of event frequencies

Other events, including increased alanine aminotransferase, increased aspartate aminotransferase, hypothyroidism, hypokalaemia, rash and pruritus, constipation, and fatigue, showed no significant differences, and no treatment-related deaths were recorded.

Overall, both regimens demonstrated manageable and broadly similar safety, and the BsAb-Combo group showed good tolerability with a controllable safety profile.

Subgroup and exploratory analyses

The purpose of subgroup analysis is to explore the heterogeneity of treatment effects and find potential subgroups that may derive significant survival benefits. The results are summarized in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Subgroup analysis of PFS

In all patients, the BsAb-Combo group demonstrated an HR of 0.88 versus the PD-1i-Combo group (95% CI, 0.44–1.1.75; p = 0.709). Although this difference was not statistically significant, an HR < 1 suggests a trend toward improved outcomes with the BsAb-based combination regimen.

Subgroup analyses revealed no significant treatment-by-subgroup interactions, with p for interaction values ranging from 0.139 to 0.776, which indicates that efficacy was broadly consistent across the predefined categories.

In the “Persistent or recurrent with distant metastases” subgroup, the BsAb-Combo group exhibited a lower hazard ratio (HR = 0.22, p = 0.065), suggesting a potential survival benefit in this population; the p-value approached statistical significance. Nevertheless, the confidence interval was wide, and the treatment-subgroup interaction did not reach significance. Accordingly, this finding remains exploratory and requires validation in larger cohorts with longer follow-up.

Prognostic and landmark analyses

Univariate Cox analysis (Table 4) demonstrated that ECOG PS 2, absence of maintenance therapy, and a recurrence-free interval ≤ 1 year were each associated with shorter PFS (p < 0.05). Variables with p < 0.10 in the univariate analysis were subsequently entered into the multivariate model; three independent predictors of PFS emerged: ECOG PS 2 (HR = 2.465, 95% CI 1.159–5.239, p = 0.019) and lung metastasis (HR = 3.151, 95% CI 1.331–7.461, p = 0.009) each conferred a higher risk of progression, whereas completion of ≥ 1 year of maintenance therapy was strongly protective (HR = 0.039, 95% CI 0.005–0.327, p = 0.003).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate Cox analyses of PFS and OS in the total patient cohort (N = 86)

| PFS | OS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| univariate analysis | Multivarite analysis | univariate analysis | Multivarite analysis | |||||

| HR(95%CI) | p | HR(95%CI) | p | HR(95%CI) | p | HR(95%CI) | p | |

| Age (≥ 65 vs. < 65) | 2.038(0.841–4.941) | 0.115 | 1.581(0.506–4.943) | 0.431 | ||||

| Hypertension (Yes vs. No) | 1.116(0.573–2.173) | 0.747 | 0.676(0.261–1.748) | 0.419 | ||||

| ECOG PS (2 vs. ≤ 1) | 3.100(1.540–6.241) | 0.002 | 2.465(1.159–5.239) | 0.019 | 2.885(1.131–7.360) | 0.027 | 2.882(1.098–7.567) | 0.032 |

| Disease status | ||||||||

| Persistent or recurrent with distant metastases vs. metastatic(FIGO 2018: IVB) | 0.737(0.312–1.741) | 0.487 | 0.532(0.163–1.734) | 0.295 | ||||

| Persistent or recurrent without distant metastases vs. metastatic(FIGO 2018: IVB) | 0.772(0.370–1.608) | 0.489 | 0.698(0.258–1.884) | 0.478 | ||||

| Pathological diagnosis (adenocarcinoma vs. squamous cell carcinoma) | 0.685(0.164–2.863) | 0.604 | 0.830(0.109–6.307) | 0.857 | ||||

| Histologic grade (G1,G2,x vs. G3) | 1.300(0.679–2.489) | 0.429 | 0.844(0.347–2.052) | 0.709 | ||||

| Metastatic region count (Multiple vs. Single) | 1.723(0.892–3.327) | 0.105 | 1.596(0.631–4.039) | 0.324 | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 1.106(0.519–2.358) | 0.794 | 1.615(0.538–4.848) | 0.393 | ||||

| Lung metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 2.025(0.911–4.501) | 0.083 | 3.151(1.331–7.461) | 0.009 | 2.592(1.025–6.555) | 0.044 | 2.572(0.931–7.102) | 0.068 |

| Pelvic cavity metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 1.884(0.902–3.936) | 0.092 | 1.993(0.892–4.453) | 0.093 | 1.708(0.649–4.496) | 0.278 | ||

| Bone metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 0.661(0.256–1.705) | 0.392 | 0.032(0.000–3.248) | 0.145 | ||||

| Radiotherapy for recurrence (Yes vs. No) | 1.033(0.531–2.012) | 0.923 | 1.513(0.584–3.919) | 0.394 | ||||

| Bevacizumab use during the treatment (Yes vs. No) | 0.889(0.446–1.775) | 0.739 | 0.843(0.320–2.222) | 0.730 | ||||

| Maintenance therapy (Yes vs. No) | 0.483(0.251–0.928) | 0.029 | 1.144(0.557–2.352) | 0.714 | 0.574(0.240–1.374) | 0.213 | ||

| 1 year of maintenance therapy (Yes vs. No) | 0.046(0.006–0.350) | 0.003 | 0.039(0.005–0.327) | 0.003 | 0.024(0.000–1.255) | 0.065 | 0.000(0.000–1.761E + 259) | 0.965 |

| Recurrence-free interval (> 1year vs. ≤ 1year) | 0.430(0.188–0.982) | 0.045 | 0.539(0.217–1.340) | 0.184 | 0.766(0.295–1.988) | 0.584 | ||

| Response evaluation after 2 cycles of treatment (SD vs. CR + PR) | 1.166(0.594–2.289) | 0.655 | 0.823(0.313–2.168) | 0.694 | ||||

| Number of treatment cycles (≥ 6 cycles vs. < 6 cycles) | 0.826(0.430–1.587) | 0.566 | 1.392(0.567–3.416) | 0.470 | ||||

| Treatment regimen (BsAb-Combo vs. PD-1i-Combo) | 0.876(0.439–1.751) | 0.709 | 1.163(0.428–3.159) | 0.767 | ||||

For OS, univariate Cox analysis likewise implicated ECOG PS 2 and lung metastasis as adverse factors (p < 0.05). In the multivariate model, ECOG PS 2 retained its detrimental impact on OS (HR = 2.882, 95% CI 1.098–7.567, p = 0.032), while lung metastasis showed only a borderline association (HR = 2.572, 95% CI 0.931–7.102, p = 0.068).

Collectively, these findings highlight baseline functional status as the dominant determinant of long-term outcome, while sustained maintenance therapy appears critical for delaying disease progression.

To mitigate the potential immortal-time bias introduced by the ≥ 1-year maintenance variable, a 12-month landmark analysis was undertaken (Fig. 6). Among the 44 patients who were alive and progression-free at 12 months (≥ 1-year maintenance, n = 13; < 1-year maintenance, n = 31), continued maintenance therapy conferred a clear advantage: mPFS-LM was not reached in the ≥ 1-year group versus 15.2 months in the < 1-year group (log-rank p = 0.001), and mOS-LM (patients who were alive at 12 months) was likewise not reached versus 24.8 months, respectively (log-rank p = 0.003).

Fig. 6.

Landmark analysis of progression-free and overall survival according to maintenance duration

In the 12-month landmark multivariable Cox model, adjusted for ECOG performance status, lung metastasis, pelvic cavity metastasis, recurrence-free interval, and maintenance therapy, ≥ 1-year maintenance therapy remained a powerful independent predictor of prolonged PFS-LM (adjusted HR = 0.016, 95% CI 0.001–0.225, p = 0.002). For OS-LM, ≥ 1-year maintenance remained independently associated with improved OS (adjusted HR = 0.072, 95% CI 0.001–0.553, p = 0.006) after adjusting for ECOG PS and lung metastasis.

The direction and magnitude of benefit were consistent with the primary analysis, supporting the robustness of our findings.

Sensitivity analyses

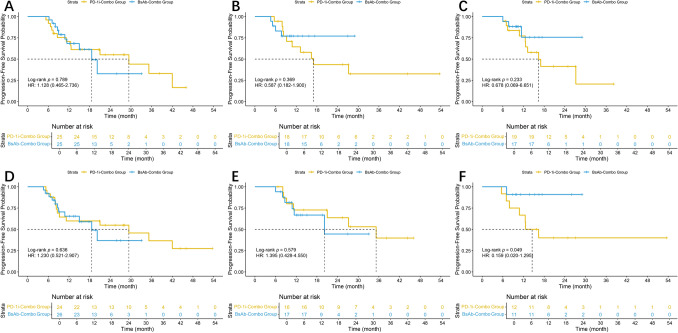

To evaluate the robustness of the primary PFS and OS comparisons after PSM, sensitivity analyses were performed according to three clinically relevant sources of heterogeneity (Fig. 7A–F; Fig. 8A–F).

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analyses for PFS: A–B with versus without radiotherapy; C–D with versus without concomitant bevacizumab; and E–F single-agent versus dual/other maintenance therapy

Fig. 8.

Sensitivity analyses for OS: A–B with versus without radiotherapy; C–D with versus without concomitant bevacizumab; and E–F single-agent versus dual/other maintenance therapy

In pre-specified sensitivity analyses that stratified the matched cohort by key sources of clinical heterogeneity, PFS remained broadly comparable between the BsAb-Combo and PD-1-Combo regimens. Specifically, neither radiotherapy status nor concomitant bevacizumab use modified the treatment effect, and no interaction terms reached significance. When maintenance therapy was examined, dual-agent maintenance showed a borderline reduction in progression risk with BsAb-Combo (HR = 0.159, p = 0.049); however, the wide confidence interval underscores the limited precision of this finding. Collectively, these analyses support the robustness of the main PFS comparison.

In the corresponding OS sensitivity analyses, no statistically significant treatment-effect difference was detected in any subgroup. Overall survival curves overlapped regardless of radiotherapy, bevacizumab use, or maintenance strategy. Taken together, the OS findings mirror the PFS results and further substantiate the robustness of the matched comparisons.

Discussion

One of the most actively explored areas in tumor immunotherapy research is dual immunotherapy. The main approaches include combinations of two ICIs, BsAbs targeting dual immune checkpoints, BsAbs combining an immune checkpoint with a non-immune target, and dual-antibody regimens administered as antibody mixtures. By the end of 2023, a total of 11 BsAbs had been approved for the treatment of cancer [13]. Notably, we identified that five additional BsAbs received regulatory approval across different countries during 2024 alone, highlighting the accelerating global progress in this field. Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the potential of combining immunotherapy, including BsAbs, with radiotherapy or concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer (NCT05687851) [14].

In China, bispecific antibodies used in the treatment of advanced cervical cancer mainly include cadonilimab and QL1706, which target PD-1 and CTLA-4. Moreover, cadonilimab plus platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab has been upgraded to a category I recommendation for first-line treatment of advanced CC in the 2025 CSCO guidelines, while the QL1706-based regimen has been designated as a category II recommendation. However, neither cadonilimab nor QL1706 has been included in the current NCCN guidelines (2025).

There is currently no established standard for clinical decision-making regarding the use of bispecific antibodies versus PD-1 inhibitors in p/r/m CC. In practice, the choice is often based on economic factors or other non-objective considerations.

In our real-world study, the mPFS of BsAb-Combo group was 20.2 months, which is longer than 12.7 months reported in the cadonilimab group of the COMPASSION-16 clinical trial [8]. Similarly, the PD-1i-Combo group achieved an mPFS of 27.2 months, exceeding the 10.4 months reported in the KEYNOTE-826 trial [6]. Several factors may account for these differences: (1) Some patients in our study received radiotherapy targeting recurrent or metastatic lesions for local control, which may have contributed to improved survival outcomes; (2) during the maintenance phase, some patients received dual-agent maintenance therapy, such as a combination of immunotherapy and targeted agents (e.g., anlotinib), which differed from the maintenance regimens used in clinical trials and may have contributed to prolonged PFS [15, 16]. Wang’s study reported that cadonilimab combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as first-line systemic therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) showed no significant difference in PFS compared to PD-1 inhibitor plus TKI (p = 0.233) [17]. Our current findings in p/r/m CC are consistent with this conclusion (p = 0.708).

Although there were also no statistically significant differences in ORR and CR between the two groups (p > 0.05), after PSM, the BsAb-Combo group showed higher numbers of ORR and CR, which suggests that BsAb-Combo group may have better short-term efficacy.

Regarding safety outcomes, it is worth noting that during cadonilimab treatment, patients appeared to be more prone to developing high-grade fever, particularly after the second infusion. Although this trend did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.079), it has been a consistent empirical observation in our clinical practice. In addition, cases of hyperthyroidism have also been observed following bispecific antibody therapy.

We specifically observed that bispecific antibody therapy appeared to offer a potential advantage in patients with persistent or recurrent disease with distant metastases (HR = 0.22, p = 0.065). In another study [18], it was reported that in the setting of first-line cadonilimab plus chemotherapy for HER2-negative advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, HR for OS favored cadonilimab over placebo across all subgroups. The therapeutic efficacy of cadonilimab and other bispecific antibodies is being actively investigated across various tumor types, and the beneficial subgroups may gradually be revealed in the future [19–21].

Finally, we conducted a prognostic analysis of the overall p/r/m CC population. We specifically found that 1 year of maintenance therapy was associated with a significant PFS benefit. Peng's study has already demonstrated that maintenance therapy can significantly prolong both PFS and OS in patients with r/m CC. Given the ongoing controversy regarding the optimal duration of maintenance therapy in CC, this represents an important finding.

This study has several limitations. It was a single-center retrospective analysis with a limited sample size and follow-up duration. Although PSM was used to reduce baseline differences, residual confounding and treatment heterogeneity may still exist. In addition, the lack of PD-L1 data precluded subgroup analysis. Future multicenter, prospective phase III trials are warranted to confirm the efficacy of bispecific antibodies and to identify patients most likely to benefit from this approach.

Conclusion

In this real-world, propensity-score-matched cohort, a bispecific PD-1/CTLA-4 antibody plus platinum-based chemotherapy ± bevacizumab delivered efficacy and safety comparable to PD-1 inhibitor-based combinations, with a numerically favorable hazard-ratio trend. Exploratory subgroup analyses showed that patients with persistent or recurrent disease accompanied by distant metastases may gain additional benefit from the bispecific regimen. Completion of ≥ 12 months of maintenance therapy emerged as a key independent predictor of prolonged progression-free survival.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Xin Wang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Xin Wang and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [No.82172804], Key Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission [No.K2019028], Nanjing Science and Technology Plan Project [No.2022SX00001663].

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Nanjing Medical University with an approval number of KY-2025–067.

Consent to publication

All authors approved the final version and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fan H, He Y, Xiang J et al (2022) ROS generation attenuates the anti-cancer effect of CPX on cervical cancer cells by inducing autophagy and inhibiting glycophagy. Redox Biol 53:102339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chuai Y, Wang A, Li Y, Dai G, Zhang X (2019) Anti-angiogenic therapy for persistent, recurrent and metastatic cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019:CD013348

- 3.Hu Y, Li G, Ma Y, Luo G, Wang Q, Zhang S (2023) Effect of exosomal lncRNA MALAT1/miR-370-3p/STAT3 positive feedback loop on PI3K/Akt pathway mediating cisplatin resistance in cervical cancer cells. J Oncol 2023:1–16 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monk BJ, Sill MW, McMeekin DS, Cohn DE, Ramondetta LM, Boardman CH, Benda J, Cella D (2009) Phase III trial of four cisplatin-containing doublet combinations in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent cervical carcinoma: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 27:4649–4655 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tewari KS, Sill MW, Penson RT et al (2017) Bevacizumab for advanced cervical cancer: final overall survival and adverse event analysis of a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial (gynecologic oncology group 240). Lancet 390:1654–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D et al (2021) Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 385:1856–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oaknin A, Gladieff L, Martínez-García J et al (2024) Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy for metastatic, persistent, or recurrent cervical cancer (BEATcc): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet (lond Engl) 403:31–43 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X, Sun Y, Yang H et al (2024) Cadonilimab plus platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab as first-line treatment for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer (COMPASSION-16): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial in China. Lancet 404:1668–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xing Y, Yasinjan F, Du Y et al (2023) Immunotherapy in cervical cancer: from the view of scientometric analysis and clinical trials. Front Immunol 14:1094437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Huang Y, Yang Y et al (2025) Iparomlimab and tuvonralimab (QL1706) plus chemotherapy and bevacizumab for EGFR-mutant patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer after failure of EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors: updated results from cohort 5 in the DUBHE-L-201 study. J Hematol Oncol 18:75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shan KS, Musleh Ud Din S, Dalal S, Gonzalez T, Dalal M, Ferraro P, Hussein A, Vulfovich M (2025) Bispecific antibodies in solid tumors: advances and challenges. Int J Mol Sci 26:5838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong A, Wang L, Chen J et al (2025) Ivonescimab versus pembrolizumab for PD-L1-positive non-small cell lung cancer (HARMONi-2): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study in China. Lancet 405:839–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein C, Brinkmann U, Reichert JM, Kontermann RE (2024) The present and future of bispecific antibodies for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 23:301–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Z, Yang L, Liu Q, Yu H, Chen L (2022) Machine learning of dose-volume histogram parameters predicting overall survival in patients with cervical cancer treated with definitive radiotherapy. J Oncol 2022:1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng C, Li X, Tang W et al (2024) Real-world outcomes of first-line maintenance therapy for recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer: a multi-center retrospective study. Int Immunopharmacol 129:111578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng Y, Wu D, Tang J, Li X (2025) Efficacy and safety of anlotinib and PD-1/L1 inhibitors as maintenance therapy for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer patients who have achieved stable-disease after first-line treatment with chemotherapy and immunotherapy: a retrospective study. Cancer Control 32:10732748251318383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Pan S, Tian J et al (2025) Cadonilimab, a PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific antibody in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world study. Cancer Immunol Immunother 74:186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen L, Zhang Y, Li Z et al (2025) First-line cadonilimab plus chemotherapy in HER2-negative advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Nat Med 31:1163–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H, Li L, Li X, et al (2024) Second-line treatment of PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade combined with liposomal irinotecan plus leucovorin and fluorouracil for advanced cholangiocarcinoma: study protocol of a single-arm, prospective phase II trial. Ther Adv Med Oncol 16:1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang Y, Bei W, Wang L et al (2025) Efficacy and safety of cadonilimab (PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific) in combination with chemotherapy in anti-PD-1-resistant recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. BMC Med 23:152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Zhao W, Li C et al (2024) The efficacy and safety of a novel PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific antibody cadonilimab (AK104) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter retrospective observational study. Thorac Cancer 15:2327–2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.