Abstract

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare and fatal disease. The Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index is a non-invasive score for distinguishing patients with normal/mild elevation of liver transaminase, but its correlation with adult HLH and 30-day mortality is unclear. The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between admission FIB-4 and 30-day mortality in adult patients with HLH.

Methods

A retrospective investigation of 467 adult patients with HLH was conducted. Logistic regression analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to analyze risk factors.

Result

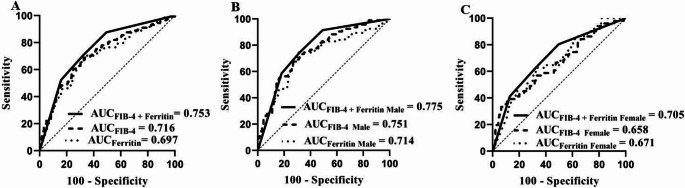

Of the 467 adult patients with HLH, 145 (31.0%) died. Elevated admission FIB-4 is an independent risk index for 30-day mortality in adult HLH patients and subgroups. The areas under the ROC curve (AUC) of admission FIB-4 for forecasting 30-day Mortality were 0.716 for the total HLH group and 0.751 for the male HLH group. Moreover, the combination of admission FIB-4 and ferritin had the best predictive ability (AUC = 0.753 for the total group and AUC = 0.775 for the male group).

Conclusions

Admission FIB-4 is an independent, inexpensive, and universally applicable factor for clinicians to recognize high-risk patients with fair value.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00277-025-06623-4.

Keywords: Adult, Fibrosis‑4, Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, Mortality, Prognosis

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), including inherited and non-inherited forms, is a rare and fatal disease characterized by cytokine storms and multiple organ dysfunction [1]. Hypercytokinemia is a key factor in the development of HLH [2]. Activated cells (T cells and macrophages) can accumulate in organs (such as the liver and spleen) to release overwhelming inflammatory cytokines, leading to fever and dysfunction of the liver, spleen and kidney [3].

Aspartate-aminotransferase, which originates in the liver and other organs, is used as an indicator of liver disease and other organ dysfunction [4]. The De Ritis ratio can be used as a prognosis indicator [5]. The De Ritis ratio has also been identified as a diagnostic and/or prognostic biomarker for HLH [6, 7]. Compared with patients with HLH without hepatic involvement, those with hepatic involvement had worse overall survival [8]. Our previous investigations also confirmed that elevated aspartate transaminase (ALT) levels were an independent risk factor for adult HLH (6-month survival) [9, 10].

The Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index is a non-invasive score for distinguishing patients with normal/mild elevation of liver transaminases [11]. Previous research has suggested that FIB-4 could play a prognostic role in patients with liver diseases [12] and non-liver diseases [13, 14]. However, there has been no investigation of FIB-4 and 30-day mortality in adult patients with HLH. Thus, we conducted this study to evaluate the prognostic value of admission FIB-4 in adult HLH patients and compare it with age and platelet, ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and ferritin levels.

Patients and methods

This retrospective observational investigation was conducted from January 2015 to September 2021 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Patients with an initial diagnosis of HLH (meeting five or more of the eight HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria) were selected [15]. Patients (≥ 18 years) with age, platelet count, ALT level, AST level, and newly diagnosed HLH were included. Patients without follow-up results and admission FIB-4 results were excluded, as were those who refused to participate in this survey. Finally, 467 patients were included in this study. Admission data at the initial time of HLH diagnosis before treatment were gathered, including demographics, underlying disease, clinical signs, and laboratory findings. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (2019-SR-066). The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Non-invasive scores

The admission FIB-4 score was calculated as follows: age (years) × AST (U/L)/Platelet Count (109∕L) × √ALT (U/L).

Mortality

The primary endpoint of the study was all-cause Mortality within 30 days after HLH was first confirmed.

Statistical analysis

Variables are shown as number (percentage), mean ± standard deviation, or median (range). Comparisons were conducted using the t-test (mean ± standard deviation) or Mann–Whitney U test (median (range)). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to estimate the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and evaluate the cut-off value of ferritin, admission FIB-4 score, and age; the cut-off values of the other parameters included in this investigation were determined by the diagnostic criteria (neutrophil, hemoglobin, platelet, fibrinogen (FIB), triglyceride (TG)) (HLH-2004) [15] or reference ranges (ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), albumin, urea nitrogen (UREA), and creatinine (CREA)) (Supplementary Table 1). Logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent risk parameters. Subgroup analysis was performed according to sex and underlying diseases. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 21). Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The enrolled patients were predominantly from the following departments: hematology, infectious diseases, ICU, oncology, and rheumatology/immunology, 30-day Mortality was observed in 145 (31.0%). The baseline characteristics of demographics, clinical signs, and laboratory results of the total and subgroups of adult HLH patients are displayed in Table 1. There were 183 males and 139 females with a median age of 52.5 years old in the survivor group and 94 males and 51 females with a median age of 58 years in the nonsurvivor group. Ferritin (median) was 1917.2 and 6057.0 µg/L, platelet (median) was 77.5 and 41.0 × 109/L, ALT (median) was 43.4 and 61.6 U/L, AST (median) was 56.9 and 104.2 U/L, and admission FIB-4 (median) was 6.015 and 17.751 for patients in the survivor and nonsurvivor groups, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in the cohort

| General | Total (n = 467) | Survivor (n = 322) | Nonsurvivor (n = 145) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female),n | 277/190 | 183/139 | 94/51 | 0.104 |

| Age,y | 55 (18, 88) | 52.5 (18, 88) | 58 (18, 80) | 0.001 |

| Clinical features | ||||

| Fever,n | 434 | 302 | 132 | 0.284 |

| Hepatomegaly | 46 | 30 | 16 | 0.565 |

| Splenomegaly | 219 | 157 | 62 | 0.230 |

| Lymph node enlargement | 207 | 145 | 62 | 0.648 |

| Rash | 80 | 54 | 26 | 0.759 |

| Jaundice | 39 | 19 | 20 | 0.004 |

| Edema | 73 | 47 | 26 | 0.360 |

| Neurological symptom | 110 | 58 | 52 | < 0.001 |

| Bone marrow hemophagocytosis | 149 | 103 | 46 | 0.955 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Ferritin (µg/L) | 2671.0 (15.2, 15000) | 1917.2 (5.2, 15000) | 6057.0 (16.9, 15000) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil (×109/L) | 2.28 (0, 62.78) | 2.34 (0.01, 48.29) | 2.04 (0, 62.78) | 0.198 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 95.5 ± 24.0 | 96.8 ± 24.0 | 92.50 ± 23.9 | 0.072 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 65.0 (2.0, 512.0) | 77.5 (3.0, 447.0) | 41.0 (2.0, 512.0) | < 0.001 |

| FIB (g/L) | 2.25 (0.21, 8.41) | 2.50 (0.44, 8.41) | 1.77 (0.21, 7.04) | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 46.9 (0.6, 3249.3) | 43.4 (0.6, 2894.1) | 61.6 (7.8, 3249.3) | 0.031 |

| AST (U/L) | 68.6 (7.6, 4688.1) | 56.9 (7.6, 2078.0) | 104.2 (11.4, 4688.1) | 0.001 |

| ALP (U/L) | 128.2 (19.0, 2421.4) | 111.5 (29.0, 2421.4) | 159.8 (19.0, 1163.0) | < 0.001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 78.5 (7.9, 1464.9) | 70.1 (7.9, 1464.9) | 113.3 (10.3, 1410.4) | < 0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.87 (0.35, 14.92) | 1.77 (0.42, 8.50) | 2.29 (0.35, 14.92) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 28.73 ± 5.55 | 29.31 ± 5.46 | 27.44 ± 5.55 | 0.001 |

| UREA (mmol/L) | 5.60 (1.20, 61.08) | 5.03 (1.20, 49.40) | 7.44 (1.90, 61.08) | < 0.001 |

| CREA (µmol/L) | 61.4 (17.7,561.8) | 58.5 (22.0, 416.0) | 67.5 (17.6, 561.8) | < 0.001 |

| FIB-4 | 7.941 (0.460, 777.735) | 6.015 (0.477, 777.735) | 17.751 (0.460, 533.309) | < 0.001 |

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CREA: creatinine; FIB, fibrinogen; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4; GGT: gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; TG: triglyceride; UREA: Blood urea nitrogen. FIB-4 = age (years) × AST (U/L)/Platelet Count (109∕L) × √ALT (U/L)

Independent factors for the 30-day of mortality

Logistic regression analysis was used to select independent factors that were highly related to 30-day mortality. First, we converted laboratory biomarkers and age into categorical variables. Univariate analysis was first conducted to select the variables with P < 0.1, the results exhibited that age > 47y, ferritin > 3687 µg/L, neutrophil < 1.0 × 109/L, hemoglobin < 90 g/L, platelet < 100 × 109/L, FIB < 1.5 g/L, ALT > 40 U/L, AST > 40 U/L, ALP > 120 U/L, GGT > 60 U/L, TG > 3.0 mmol/L, UREA > 8.2 mmol/L, CREA > 133 µmol/L and admission FIB-4 > 9.801 were the selected variables; then we included these selected variables into a model to screen independent biomarkers. The results confirmed that age > 47y (hazard ratio (HR): 2.012 (1.162–3.487), P = 0.013), ferritin > 3687 µg/L (HR: 3.843 (2.409–6.130), P < 0.001), FIB < 1.5 g/L (HR: 2.252 (1.351–3.745), P = 0.002), UREA > 8.2 mmol/L (HR: 2.200 (1.337–3.619), P = 0.002) and admission FIB-4 > 9.801 (HR: 1.995 (1.211–3.287), P = 0.007) were independent factors. Thus, the above results suggest that admission FIB-4 is an independent factor that is highly related to 30-day mortality in adult HLH (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate logistic regression analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis in cohorts

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Gender | 1.400 (0.933–2.101) | 0.127 | 1.027 (0.625–1.687) | 0.918 | |

| Age > 47y | 2.395 (1.519–3.777) | < 0.001 | 2.013 (1.162–3.487) | 0.013 | |

| Ferritin > 3687 µg/L | 5.044 (3.293–7.726) | < 0.001 | 3.843 (2.409–6.130) | < 0.001 | |

| Neutrophil < 1.0 × 109/L | 1.965 (1.253–3.077) | 0.004 | 1.393 (0.797–2.433) | 0.244 | |

| Hemoglobin < 90 g/L | 1.449 (0.976–2.155) | 0.085 | 1.190 (0.721–1.965) | 0.496 | |

| PLT < 100 × 109/L | 2.618 (1.637–4.184) | < 0.001 | 1.339 (0.683–2.625) | 0.369 | |

| FIB < 1.5 g/L | 3.356 (2.179–5.155) | < 0.001 | 2.252 (1.351–3.745) | 0.002 | |

| ALT > 40 U/L | 1.463 (0.980–2.184) | 0.070 | 1.178 (0.665–2.088) | 0.574 | |

| AST > 40 U/L | 1.935 (1.223–3.061) | 0.005 | 1.079 (0.552–2.106) | 0.825 | |

| ALP > 120 U/L | 1.838 (1.231–2.747) | 0.004 | 1.074 (0.585–1.970) | 0.818 | |

| GGT > 60 U/L | 2.104 (1.379–3.212) | 0.001 | 1.302 (0.697–2.435) | 0.408 | |

| TG > 3.0 mmol/L | 2.396 (1.535–3.738) | < 0.001 | 1.170 (0.675–2.029) | 0.575 | |

| Albumin < 40 g/L | 1.517 (0.411–5.587) | 0.763 | 3.343 (0.737–15.164) | 0.118 | |

| UREA > 8.2 mmol/L | 3.777 (2.446–5.835) | < 0.001 | 2.200 (1.337–3.619) | 0.002 | |

| CREA > 133 µmol/L | 3.209 (1.648–6.250) | 0.001 | 1.266 (0.548–2.920) | 0.581 | |

| FIB-4 > 9.8012 | 4.612 (3.021–7.042) | < 0.001 | 1.995 (1.211–3.287) | 0.007 | |

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI: confidence interval; CREA: creatinine; FIB, fibrinogen; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4; HR, hazard ratio; GGT: gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; TG: triglyceride; UREA: Blood urea nitrogen. FIB-4 = age (years) × AST (U/L)/Platelet Count (109∕L) × √ALT (U/L)

Subgroup analysis

Patients were divided into two groups according to sex. Before adjusted, admission FIB-4 > 9.801 was a significant variable (Male: HR: 5.604 (3.203–9.804), P < 0.001; Female: HR: 3.299 (1.697–6.415), P = 0.001). When the confounding parameters were adjusted, admission FIB-4 > 9.801 remained an independent risk parameter (male: adjusted HR:1.947 (1.010–3.845), P = 0.045; female: adjusted HR:2.415 (1.190–4.904), P = 0.015) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Gender stratification analysis for the relationship between FIB-4 and 30-day mortality

| HR | (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude model | |||

| Male | 5.604 | (3.203–9.804) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 3.299 | (1.697–6.415) | 0.001 |

| Fully adjusted model | |||

| Male | 1.947 | (1.010–3.845) | 0.045 |

| Female | 2.415 | (1.190–4.904) | 0.015 |

CI: confidence interval; HR, hazard ration

In addition, we also divided the patients into two groups according to the underlying disease (malignancy/infection) (M-HLH (underlying disease including malignancy) and Non-M-HLH or I-HLH (underlying disease including infection) and Non-I-HLH). The results also suggested that admission FIB-4 was an independent predictor of 30-day mortality for subgroups according to underlying disease (malignancy/infection) (Supplementary Table 2).

Performance evaluation

ROC was used to evaluate the performance of age, platelet count, ALT, AST, admission FIB-4, and ferritin levels. Among these parameters, admission FIB-4 exhibited the best predictive ability, with an AUC of 0.716 (sensitivity: 69.7%; specificity: 66.8%) for the total HLH group (age: AUC = 0.594; platelet: AUC = 0.670; ALT: AUC = 0.570; AST: AUC = 0.634; ferritin: AUC = 0.697 (sensitivity: 70.3%; specificity: 68.0%) and 0.751 (sensitivity: 68.1%; specificity: 72.7%)) for the male HLH group (age: AUC = 0.584, platelet: AUC = 0.716, ALT: AUC = 0.551, AST: AUC = 0.626, ferritin: AUC = 0.714 (sensitivity: 74.5%; specificity: 69.4%)) (Fig. 1). The AUCs for admission FIB-4 in other groups (M-HLH (AUC = 0.710) and non-M-HLH (AUC = 0.722), I-HLH (AUC = 0.708), and Non-I-HLH (AUC = 0.743)) were also evaluated (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results showed that admission FIB-4 had a fair predictive value in predicting 30-day mortality for adult HLH and its subgroups.

Fig. 1.

Performance of FIB-4, ferritin and the combination of FIB-4 and ferritin in the total and subgroup adult HLH patients. (A) ROC of FIB-4, ferritin and the combination of FIB-4 and ferritin in total adult HLH patients. (B) ROC of FIB-4, ferritin and the combination of FIB-4 and ferritin in adult male HLH patients. (C) ROC of FIB-4, ferritin and the combination of FIB-4 and ferritin in adult female HLH patients

In addition, ROC analysis showed that the combination of admission FIB-4 > 9.801 µg/L and ferritin > 3687 µg/L had the best predictive ability than them alone (AUC = 0.753 (sensitivity: 70.3%; specificity: 68.0%) for the total group and AUC = 0.775 (sensitivity: 74.5%; specificity: 68.3%) for the male group).

Hence, based on the above results, admission FIB-4 was an independent factor with a fair predictive value that was highly related to 30-day mortality in adult HLH, especially in adult male HLH patients.

Discussion

The current research supports the importance of elevated admission FIB-4 as an independent biomarker, which is related to a higher risk of 30-day mortality in the total and subgroups of adult HLH patients. In addition, our results revealed that admission FIB-4 was superior to age, platelet count, transaminases (ALT and AST), and ferritin alone in predicting 30-day mortality in adult patients with HLH.

Age is the basic information of patients. Platelet, ALT, and AST levels are inexpensive and freely available routine blood examinations that effectively reflect the outcomes and survival rates of patients with diverse diseases, including HLH [11, 16, 17]. The 5-year survival rate of HLH patients (≤ 2y) with hepatic involvement or without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation was poor [18]. Elevated AST levels were also found in non-survivors of HLH patients [19]. Compared with these indices alone, a combination of the above four indices, commonly termed FIB-4, displays higher prognostic accuracy and precision.

Studies have suggested that age is closely associated with poor prognosis [8]. Liver dysfunction (severe cholestasis and/or transaminase) was confirmed as a risk factor for short-term survival [8]. Zhang et al. also reported that patients with liver involvement (hepatomegaly/elevated liver enzymes) had a poor outcome (five years survival rate) in HLH [18]. Our previous investigations also suggested that advanced age, platelet count, ALT, and AST were associated with in-hospital Mortality and 6-month mortality [9, 10, 20]. However, individual test results are easily affected by various factors.

FIB-4 is a stable combination index that can distinguish patients with normal or mild elevation of liver transaminases. FIB-4 is a useful liver marker for predicting liver outcomes (chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis) in the general population [21, 22]. In addition, FIB-4 has been reported to be associated with perioperative mortality in patients without evident liver disease [23]. Besides liver diseases, the value of FIB-4 has also been investigated in other diseases such as COVID-19 and acute heart failure [24, 25]. Hence, we speculated that FIB-4 may be a promising prognostic index for adult HLH. However, no relevant research has yet been conducted. In addition, Yao reported that the distribution of HLH etiology differs by sex (male: lymphoma-associated HLH patients; female: rheumatic and immune-associated HLH) [26]. In patients with fatty liver disease, the FIB-4 index in men rather than in women is an independent risk factor [27]. Thus, we conducted this study to evaluate the prognostic value of FIB-4 in adult HLH patients as a total and subgroups (male HLH and female HLH, M-HLH and Non-M-HLH, or I-HLH and Non-I-HLH).

The included patients were divided into survivor and non-survivor groups. The results showed that the survivor group had a lower FIB-4 index. Logistic regression analysis confirmed that there was an inverse correlation (not interfered with by other confounding factors) between FIB-4 and 30-day mortality in the total cohort and subgroups (male HLH and female HLH, M-HLH and Non-M-HLH, or I-HLH and Non-I-HLH). ROC analysis indicated that admission FIB-4 is a prognostic factor in predicting 30-day mortality with fair value, and the AUC of the male HLH group was higher than that of the total cohort and subgroups. Taken together, admission FIB-4 was an independent factor with a fair predictive value that was highly related to 30-day mortality in adult HLH, especially in adult male HLH patients.

This study had some limitations. First, as this was a retrospective investigation, the cause-and-effect relationship between admission FIB-4 and 30-day mortality was not confirmed. Second, selection bias may have been present in the included cohort. Third, some important factors and inflammatory markers, such as TNF-α, genetic testing results, CRP, PCT, and IL-6, CD25 may not be taken into account, as these markers were not routinely measured at admission. Fourth, the performance of admission FIB-4 was not confirmed in the internal and external cohorts. Thus, prospective and multicenter research is needed in the future.

Conclusion

This is the first study to assess admission FIB-4 is a stable, inexpensive, and universally applicable factor for 30-day mortality in the total and subgroups of adult HLH patients. Admission FIB-4 alone or admission FIB-4 combined with ferritin is helpful for clinicians to recognize high-risk patients with fair value, especially adult male HLH patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Hua-Guo Xu, Jun Zhou, Mengxiao Xie, Zhi-Qi Wu and Mingjun Xie. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jun Zhou and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82101902), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (SBK2020042441), Jiangsu women and children health hospital (FYRC202017), Jiangsu Provincial Research Hospital (YJXYY202201) and Jiangsu Provincial Medical Key Discipline (Laboratory) (ZDXK202239), Jiangsu Province Association of Maternal and Child Health (FYX202303).

Data availability

The data and materials can be found from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, China) (2019-SR-066). Informed content from each patient was waived.

Consent for publication

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jun Zhou, Mengxiao Xie and Mingjun Xie contributed equally.

References

- 1.Setiadi A, Zoref-Lorenz A, Lee CY, Jordan MB, Chen LYC (2022) Malignancy-associated haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Lancet Haematol 9(3):e217–e227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu M, Xie Y, Guan X, Wang M, Zhu L, Zhang S et al (2021) Clinical analysis and a novel risk predictive nomogram for 155 adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Ann Hematol 100(9):2181–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffin G, Shenoi S, Hughes GC (2020) Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 34(4):101515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao D, Zhang Y, Yin Z, Zhao J, Yang D, Zhou Q (2017) Clinical predictors of multiple organ dysfunction syndromes in pediatric patients with scrub typhus. J Trop Pediatr 63(3):167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mo Q, Liu Y, Zhou Z, Li R, Gong W, Xiang B et al (2022) Prognostic value of aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase ratio in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatectomy. Front Oncol 12:876900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filipovich AH (2009) Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program :127–131 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Yin G, Man C, Liao S, Qiu H (2020) The prognosis role of AST/ALT (De Ritis) ratio in patients with adult secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Mediators Inflamm 2020:5719751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koh KN, Im HJ, Chung NG, Cho B, Kang HJ, Shin HY et al (2015) Clinical features, genetics, and outcome of pediatric patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Korea: report of a nationwide survey from Korea histiocytosis working party. Eur J Haematol 94(1):51–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou J, Zhou J, Wu ZQ, Goyal H, Xu HG (2020) A novel prognostic model for adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 15(1):215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Zhou J, Shen DT, Goyal H, Wu ZQ, Xu HG (2020) Development and validation of the prognostic value of ferritin in adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 15(1):71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucci T, Galardo G, Gandini O, Vicario T, Paganelli C, Cerretti S et al (2022) Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index and mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med 17(6):1777–1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Luo Y, Li C, Liu J, Xiang H, Wen T (2019) The combination of the preoperative albumin-bilirubin grade and the fibrosis-4 index predicts the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection. Biosci Trends 13(4):351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu K, Shi M, Zhang W, Shi Y, Dong Q, Shen X et al (2021) Preoperative Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) evaluation may be helpful to evaluate prognosis of gastric cancer patients undergoing operation: a retrospective study. Front Oncol 11:655343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu X, Hu X, Qin X, Pan J, Zhou W (2020) An elevated Fibrosis-4 score is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis: an observational cohort study. Pol Arch Intern Med 130(12):1064–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S et al (2007) HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48(2):124–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Y, Liu H, Mao K, Zhang M, Zhou Q, Yu W et al (2019) Novel nomograms to predict lymph node metastasis and liver metastasis in patients with early colon carcinoma. J Transl Med 17(1):193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu LH, Yu WL, Zhao T, Wu MC, Fu XH, Zhang YJ (2018) Post-operative delayed elevation of ALT correlates with early death in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma and post-hepatectomy liver failure. HPB (Oxford) 20(4):321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beken B, Aytac S, Balta G, Kuskonmaz B, Uckan D, Unal S et al (2018) The clinical and laboratory evaluation of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and the importance of hepatic and spinal cord involvement: a single center experience. Haematologica 103(2):231–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arca M, Fardet L, Galicier L, Riviere S, Marzac C, Aumont C et al (2015) Prognostic factors of early death in a cohort of 162 adult haemophagocytic syndrome: impact of triggering disease and early treatment with etoposide. Br J Haematol 168(1):63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J, Wu ZQ, Qiao T, Xu HG (2022) Development of laboratory parameters-based formulas in predicting short outcomes for adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis patients with different underlying diseases. J Clin Immunol 42(5):1000–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamichi N, Shimamoto T, Okushin K, Nishikawa T, Matsuzaki H, Yakabi S et al (2022) Fibrosis-4 index efficiently predicts chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis development based on a large-scale data of general population in Japan. Sci Rep 12(1):20357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiner AD, Moran WP, Zhang J, Livingston S, Marsden J, Mauldin PD et al (2022) The association of Fibrosis-4 index scores with severe liver outcomes in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 37(13):3266–3274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zelber-Sagi S, O’Reilly-Shah VN, Fong C, Ivancovsky-Wajcman D, Reed MJ, Bentov I (2022) Liver fibrosis marker and postoperative mortality in patients without overt liver disease. Anesth Analg 135(5):957–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang K, Wang L, Shen L, He L, Wu X (2022) Quantitative assessment of fibrosis-4 score and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Sci China Life Sci 65(12):2560–2563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tseng CH, Huang WM, Yu WC, Cheng HM, Chang HC, Hsu PF et al (2022) The fibrosis‐4 score is associated with long‐term mortality in different phenotypes of acute heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 52(12):e13856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao S, Wang Y, Sun Y, Liu L, Zhang R, Fang J et al (2021) Epidemiological investigation of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in China. Orphanet J Rare Dis 16(1):342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todo Y, Miyake T, Furukawa S, Matsuura B, Ishihara T, Miyazaki M et al (2022) Combined evaluation of Fibrosis‐4 index and fatty liver for stratifying the risk for diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 13(9):1577–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials can be found from the corresponding author.