Abstract

Thalassemia is one of the most prevalent inherited hemolytic diseases. This study aimed to characterize thalassemia mutations and provide an epidemiological basis for prevention and control of the disorder in Putian. A total of 6,380 individuals were enrolled in Putian from March 2017 to February 2025. Common thalassemia mutations were screened by polymerase chain reaction-flow-through hybridization, while rare thalassemia gene variants were detected by gel electrophoresis and DNA sequencing. 2,264 cases (35.49%) were confirmed as thalassemia, including 1,418 cases of α-thalassemia, 807 cases of β-thalassemia, and 39 cases of co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia. Among the 31 α-thalassemia genotypes identified, deletions were predominant, including --SEA/αα (71.93%), -α3.7/αα (14.03%), and --SEA/-α3.7 (2.61%), with --SEA being the most frequent α-thalassemia allele. Of the 21 detected β-thalassemia genotypes, the most common were βIVS−II−654/βN (48.76%), βCD41–42/βN (27.35%), and βCD17/βN (10.40%), with βIVS−II−654 being the most frequent β-thalassemia allele. In addition, 18 distinct genotypes of co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia were identified. Population migration has introduced new thalassemia genotypes to Putian. It was also found that the carrier rate of thalassemia genes in the infertile population of Putian was twice that of the local general population.Compared to other global regions, the thalassemia gene mutation spectrum in Putian exhibits unique genotypic diversity and population heterogeneity; moreover, the prevalence of thalassemia is higher in the local infertile population than that in the general population. These findings will provide valuable insights for thalassemia prevention and genetic counseling in this region.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00277-025-06604-7.

Keywords: Thalassemia, Gene mutation, Genotype, Epidemiology, Infertility

Introduction

Thalassemia is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterized by impaired hemoglobin synthesis, leading to ineffective erythropoiesis and chronic anemia in affected individuals. The most prevalent forms are α- and β-thalassemia. The underlying pathology of thalassemia is driven by an imbalance in globin chain production, resulting in red blood cell damage, chronic hemolytic anemia, and dysregulated iron homeostasis [1–3].

The clinical manifestations of thalassemia exhibit significant heterogeneity, ranging from asymptomatic silent carriers and mild thalassemia minor to severe thalassemia major. While silent carriers typically require no therapeutic intervention, thalassemia major necessitates comprehensive management, including regular blood transfusions and iron chelation therapy to mitigate iron overload [4, 5]. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is currently recommended as a potentially curative treatment. Recently, emerging gene therapy approaches, such as gene addition and gene editing, have shown promising results in preclinical studies and represent a potential paradigm shift in the treatment of thalassemia [6].

Thalassemia is widely recognized as a prevalent hemolytic blood disorder, particularly endemic in regions such as the Mediterranean, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, and Asia [7–11]. Recent epidemiological data have revealed an increasing prevalence of thalassemia in traditionally non-endemic areas, including North America and Western Europe, largely due to global population migration [12]. Globally, it is estimated that 1–5% of the population are thalassemia carriers, underscoring its significance as a public health concern [13]. The prevalence of thalassemia exhibits considerable geographical heterogeneity, varying not only between countries but also within individual nations. In China, thalassemia is predominantly distributed in regions south of the Yangtze River, with the highest incidence reported in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan provinces [14]. Despite its geographical proximity to Guangdong, the Putian region remains understudied, with limited epidemiological data available on the prevalence and genetic characteristics of thalassemia in this area.

In this study, we estimated the regional burden of thalassemia in Putian by synthesizing locally reported incidence rates with large-scale genetic screening data. The findings were further contextualized by comparison with global epidemiological datasets. These results provide critical insights for the development of population-specific preventive strategies.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

This study, approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Putian University(2023068), was conducted from March 2017 to February 2025. The inclusion criteria for this retrospective analysis were as follows: (1) diagnosis of microcytosis (defined as mean corpuscular volume < 80 fL and/or mean corpuscular hemoglobin < 27 pg); (2) a documented family history of thalassemia; (3) couples undergoing assisted reproductive techniques; or (4) being the spouse of a pregnant woman with confirmed thalassemia. Excluding duplicate cases, this study included a total of 6,380 individuals, primarily from the following departments of the Affiliated Hospital of Putian University: Reproductive Medicine (1,272 cases), Premarital Screening (978 cases), Prenatal Diagnosis (962 cases), Pediatrics (861 cases), Obstetrics (733 cases), and Hematology (646 cases). The age distribution of the enrolled patients ranged from 1 to 88 years.

Haematological analysis

Venous EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples (2 mL) were collected for haematological examinations performed using an automatic blood cell counter (Sysmex XN3000, Sysmex Co., Kobe, Japan). Subjects with an MCV < 80 fL and an MCH < 27 pg were considered suspected thalassemia carriers [15].

Genetic analysis

DNA was extracted from 200 µL of the EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples. Thalassemia mutations were analysed by PCR-flow-through hybridisation (Hybri Biological Products Co., Ltd.; Chaozhou, China) and identified the following mutations: three deletion α-thalassemia mutations (--SEA, -α3.7 and -α4.2); three non-deletion α-thalassemia mutations (ααWS, ααCS and ααQS); and 19 β-thalassemia mutations. PCR-gel electrophoresis initially screened six deletion-type α-thalassemia variants (HKαα, --THAI, fusion gene, αααanti4.2, αααanti3.7, -α27.6) [16]. Sanger sequencing was performed to screen for rare and previously unreported thalassemia-associated variants.

Literature review

We searched PubMed for relevant studies published in English, using the keywords ‘thalassemia’ and ‘mutation’, with an update cutoff date of December 31, 2024. The included studies were required to cover Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

Data analysis

Data were digitally recorded and managed using Microsoft Excel 2022 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Descriptive statistical analyses were performed to characterize the distribution patterns, frequencies, and mutational spectra of thalassemia and hemoglobinopathy variants.

RESULTS

Prevalence of thalassemia

Among the 6,380 individuals enrolled in our study, 2,264 cases were definitively diagnosed with thalassemia, yielding a positive rate of 35.49%. The distribution of thalassemia subtypes among confirmed cases was as follows: α-thalassemia accounted for 62.63% (1,418/2,264), β-thalassemia for 35.64% (807/2,264), and co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia for 1.73% (39/2,264). The highest positivity rates were observed in Obstetrics (73.81%) and Pediatrics (53.77%). The positivity rates in the Departments of Premarital Examination, Prenatal Diagnosis, Hematology, and Gynecology were similar(Table 1). Although the Department of Reproductive Medicine had the highest testing volumes, its positivity rate was very low at 8.65%.

Table 1.

Departmental distribution (> 100 Cases) and positivity rates

| Department | Total cases(n) | Positive Cases(n) | Positivity rates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Medicine | 1272 | 110 | 8.65 |

| Premarital Examination | 978 | 351 | 35.89 |

| Prenatal Diagnosis | 962 | 312 | 32.43 |

| Pediatrics | 861 | 463 | 53.77 |

| Obstetrics | 733 | 541 | 73.81 |

| Hematology | 646 | 253 | 39.16 |

| Gynecology | 134 | 46 | 34.33 |

Genotypes of α-thalassemias

As shown in Table 2, a total of 31 genotypes were identified among the 1,418 cases of α-thalassemia. The most prevalent genotype was --SEA/αα (Fig. 1B), accounting for 71.93% of cases, followed by -α3.7/αα (14.03%) and --SEA/-α3.7 (2.61%) (Fig. 1C). The frequencies of the three non-deletional mutations, ααCS/αα (2.19%), ααWS/αα (1.62%), and ααQS/αα (1.34%), were relatively comparable. In rare forms of α-thalassemias, the three most frequently observed genotypes were αααanti4.2(Fig. 2), --THAI/αα, HBA1:c.223G > C, which collectively accounted for 61.91% of the rare cases.

Table 2.

Genotyping of α-thalassemia in Putian

| Genotype | Number of cases(n) | Constituent ratio (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common α-thalassemia | --SEA/αα | 1020 | 71.93 |

| -α3.7/αα | 199 | 14.03 | |

| --SEA/-α3.7 | 37 | 2.61 | |

| -α4.2/αα | 32 | 2.26 | |

| ααCS/αα | 31 | 2.19 | |

| ααWS/αα | 23 | 1.62 | |

| ααQS/αα | 19 | 1.34 | |

| --SEA/-α4.2 | 12 | 0.85 | |

| -α3.7/-α3.7 | 8 | 0.56 | |

| --SEA/ααQS | 3 | 0.21 | |

| --SEA/ααWS | 2 | 0.14 | |

| --SEA/--SEA | 2 | 0.14 | |

| -α3.7/ααCS | 2 | 0.14 | |

| -α3.7/-α4.2 | 1 | 0.07 | |

| -α3.7/ααQS | 1 | 0.07 | |

| ααQS/ααQS | 1 | 0.07 | |

| -α4.2/-α4.2 | 1 | 0.07 | |

| -α4.2/ααQS | 1 | 0.07 | |

| --SEA/ααCS | 1 | 0.07 | |

| ααWS/ααWS | 1 | 0.07 | |

| Rare α-thalassemia | αααanti4.2 | 6 | 0.42 |

| --THAI/αα | 4 | 0.28 | |

| HBA1:c.223G > C | 3 | 0.21 | |

| Hkαα/--SEA | 1 | 0.07 | |

| -α3.7/--THAI | 1 | 0.07 | |

| -α4.2/--THAI | 1 | 0.07 | |

| αααanti3.7 | 1 | 0.07 | |

| HBA1:c.300 + 55G > T | 1 | 0.07 | |

| HBA1 :c.364G > A | 1 | 0.07 | |

| HBA2:c.49 A > T | 1 | 0.07 | |

| HBA2 :c.34 A > C | 1 | 0.07 | |

| Total | 1418 | 100.00 |

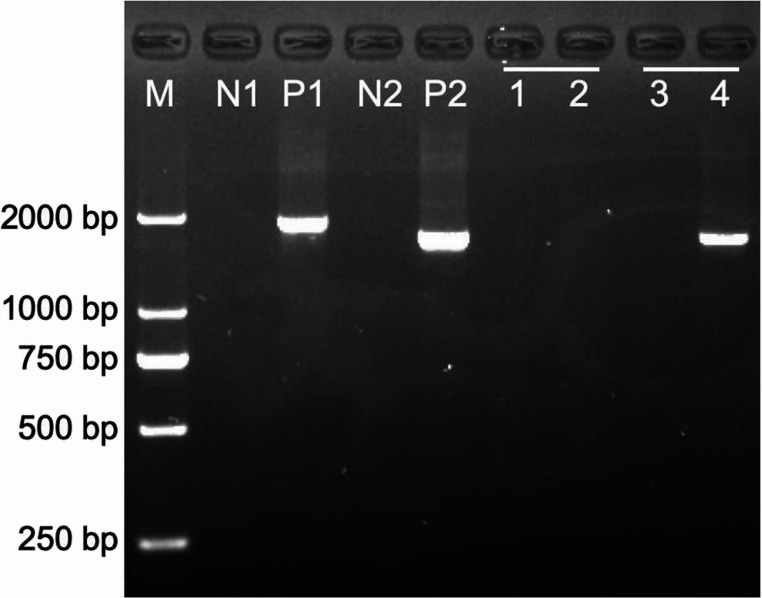

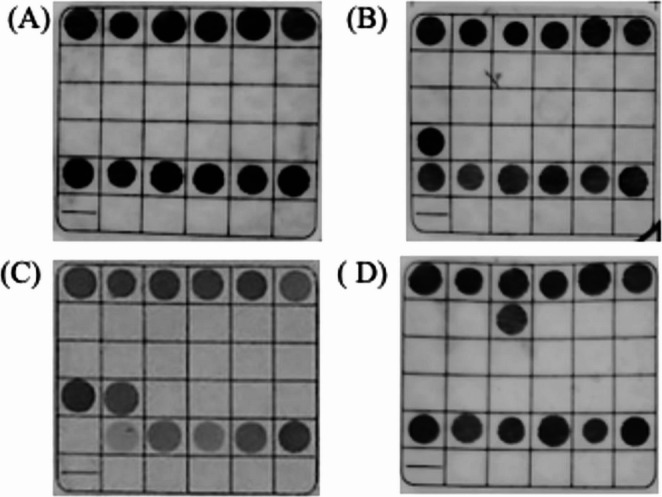

Fig. 1.

Thalassemia mutations detected by PCR-flow-through hybridisation. (A) negative; (B) --SEA/αα; (C) --SEA/-α3.7; (D) βIVS-II-654/βN

Fig. 2.

PCR-gel electrophoresis of rare thalassemia. αααanti4.2 fragment detected with specific primers. M: marker, N1: αααanti3.7 negative control, P1: αααanti3.7 positive control, N2: αααanti4.2 negative control, P2: αααanti4.2 positive control, 1: Sample 1 (αααanti3.7 del-negative), 2: Sample 1 (αααanti4.2 del-negative), 3: Sample 2 (αααanti3.7 del-negative), 4: Sample 2 (αααanti4.2 del-positive)

Genotypes of β-thalassemias

A comprehensive genotypic analysis of 807 β-thalassemia cases revealed 21 distinct genotypes, with the heterozygous βIVS-ll-654/βN (Fig. 1D) genotype demonstrating the highest prevalence at 48.76%. This was followed by βCD41–42/βN (27.35%) and βCD17/βN (10.40%) (Table 3). Three cases of double heterozygosity were identified, presenting the following genotypic combinations: βIVS-II-654/βCD17, βCD41–42/βCD17, and βCD41–42/β−28. The study population did not yield any β-thalassemia homozygotes. Additionally, molecular characterization uncovered five rare β-thalassemia mutations: HBB: c.92G > T(Fig. 3A), HBB: c.91 A > G(Fig. 3B), HBB: c.170G > A, HBB: c.113T > A and HBB: c.341T > A (Fig. 3C).

Table 3.

Genotyping of β-thalassemia in Putian

| Genotype | Number of cases(n) | Constituent ratio (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common β-thalassemia | βIVS−II−654/βN | 394 | 48.76 |

| βCD41–42/βN | 221 | 27.35 | |

| βCD17/βN | 84 | 10.40 | |

| β−28/βN | 41 | 5.07 | |

| βCD26/βN | 36 | 4.46 | |

| βCD27–28/βN | 7 | 0.87 | |

| βCD71–72/βN | 4 | 0.50 | |

| βInt/βN | 3 | 0.37 | |

| βCD43/βN | 3 | 0.37 | |

| βCap+40–43/βN | 2 | 0.25 | |

| βCD17/βIVS−II−654 | 1 | 0.12 | |

| β−29/βN | 1 | 0.12 | |

| βCD41–42/βCD17 | 1 | 0.12 | |

| βCD41–42/β−28 | 1 | 0.12 | |

| βIVS−I−5/βN | 1 | 0.12 | |

| βCD14–15/βN | 1 | 0.12 | |

| Rare β-thalassemia | HBB: c.92G > T | 2 | 0.25 |

| HBB: c.91 A > G | 1 | 0.12 | |

| HBB: c.170G > A | 1 | 0.12 | |

| HBB: c.113T > A | 1 | 0.12 | |

| HBB: c.341T > A | 1 | 0.12 | |

| Total | 807 | 100.00 |

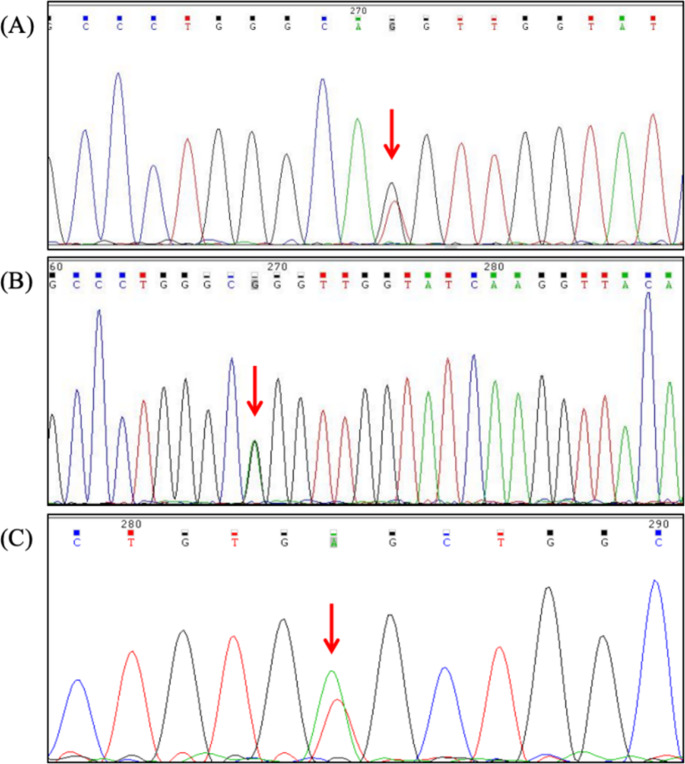

Fig. 3.

DNA sequencing of 3 rare β-thalassemia mutations. (A) HBB: c.92G > T mutation sequencing results. (B) HBB: c.91 A > G mutation sequencing results. (C) HBB: c.341T > A mutation sequencing results. The arrow shows the location of the mutation

Genotypes of co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia

In our study, a total of 39 cases were diagnosed with co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia. Among these, 18 distinct gene mutation combinations were identified, with their corresponding phenotypic characteristics and frequencies detailed in Table 4. Genotypic analysis revealed that the most prevalent mutation patterns were --SEA/αα;βIVS-Il-654/βN (23.08%) and --SEA/αα; βCD17/βN (12.82%). Furthermore, three cases exhibiting triple thalassemia gene mutations were identified in the present study. The genotypic profiles of these cases were characterized as follows: --SEA/-α3.7;βIVS-II-654/βN, --SEA/-α3.7;βCD26/βN and ααWS/αα;βIVS-II-654/βCD41–42.

Table 4.

Genotyping of co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia in Putian

| Genotype | Number of cases(n) | Constituent ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|

| --SEA/αα;βIVS-II-654/βN | 9 | 23.08 |

| --SEA/αα;βCD17/βN | 5 | 12.82 |

| --SEA/αα;βCD41–42/βN | 4 | 10.26 |

| -α3.7/αα;βIVS-II-654/βN | 4 | 10.26 |

| -α3.7/αα;βCD41–42/βN | 4 | 10.26 |

| --SEA/-α3.7;βIVS-II-654/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| -α3.7/αα;βCD17/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| -α3.7/αα;β−28/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| ααCS/αα;βCD17/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| -α4.2/αα;β−28/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| -α4.2/αα;βCD41–42/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| ααWS/αα;βIVS-II-654/βCD41–42 | 1 | 2.56 |

| ααWS/αα;βCD41–42/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| ααCS/αα;βCD41–42/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| --SEA/-α3.7;βCD26/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| -α4.2/αα;βIVS-II-654/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| --SEA/αα;βCD26/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| --SEA/αα;βCD71–72/βN | 1 | 2.56 |

| Total | 39 | 100 |

Frequency of thalassemia gene mutations

The thalassemia allele frequency distribution was systematically analyzed in a cohort of 2,264 patients. Genetic characterization revealed 15 distinct α-thalassemia mutations among 1,418 mutant chromosomes. The predominant variants were --SEA (71.79%), α3.7 (17.52%), and α4.2 (3.39%)(Table 5). Concurrently, molecular analysis of 807 β-thalassemia mutant chromosomes identified 18 β-thalassemia mutations, with the following frequency distribution: IVS-II-654 (C > T) (48.47%), followed by CD 41–42 (-CTTT) (27.71%), CD 17 (AAG > TAG) (10.97%), and − 28 (A > G) (5.07%) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Allele frequencies of α-thalassemia in Putian

| α genotype | HGVS Nomenclature | Allele | frequency(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| --SEA | NC_000016.10:g.165401_184701del | 1102 | 71.79 |

| -α3.7 | NC_000016.10:g.173384_177187del | 269 | 17.52 |

| α4.2 | NC_000016.10:g.169818_174075del | 52 | 3.39 |

| ααCS | HBA2:c.427T > C | 36 | 2.35 |

| ααWS | HBA2:c.369 C > G | 29 | 1.89 |

| ααQS | HBA2:c.377T > C | 26 | 1.69 |

| αααanti4.2 | NC_000016.10:g.169818_174075dup | 6 | 0.39 |

| --THAI | NC_000016.10:g.149863_183312del | 6 | 0.39 |

| CD 74 (GAC > CAC) | HBA1:c.223 (G > C) | 3 | 0.20 |

| IVS II-55 G > T | HBA1:c.300 + 55 (G > T) | 1 | 0.07 |

| CD 121 GTG > ATG | HBA1 :c.364 (G > A) | 1 | 0.07 |

| CD 16 (AAG > TAG) | HBA2:c.49 (A > T) | 1 | 0.07 |

| CD 11 AAG > CAG | HBA2 :c.34 (A > C) | 1 | 0.07 |

| αααanti3.7 | NC_000016.10:g.173384_177187dup | 1 | 0.07 |

| Hkαα | N/A | 1 | 0.07 |

| Total | 1535 | 100.00 |

Table 6.

Allele frequencies of β-thalassemia in Putian

| β genotype | HGVS Nomenclature | Allele | frequency(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVS-II-654 (C > T) | HBB: c.316–197 C > T | 411 | 48.47 |

| CD 41–42 (-CTTT) | HBB: c.123_124insT | 235 | 27.71 |

| CD 17 (AAG > TAG) | HBB: c.52 A > T | 93 | 10.97 |

| −28 (A > G) | HBB: c.−78 A > G-HBB: c.52 A > T | 43 | 5.07 |

| CD 26 (GAG > AAG) | HBB: c.79G > A | 37 | 4.36 |

| CD 27–28 (+ C) | HBB: c.84_85insC | 7 | 0.83 |

| CD 71–72 (+ A) | HBB: c.216_217insA | 5 | 0.59 |

| Init CD (ATG > AGG) | HBB: c.2T > G | 3 | 0.35 |

| CD 43 (GAG > TAG) | HBB: c.130G > T | 3 | 0.35 |

| Cap + 40–43 (-AAAC) | HBB: c.−10_−7delAACA | 2 | 0.24 |

| CD 30 (AGG > ATG) | HBB: c.92G > T | 2 | 0.24 |

| −29 (A > G) | HBB: c.−79 A > G | 1 | 0.12 |

| IVS-I-5 (G > C) | HBB: c.92 + 5G > C | 1 | 0.12 |

| CD 14–15 (+ G) | HBB: c.45_46insG | 1 | 0.12 |

| CD 30 (AGG > GGG) | HBB: c.91 A > G | 1 | 0.12 |

| CD 56 GGC > GAC | HBB: c.170 (G > A) | 1 | 0.12 |

| CD 37 TGG > AGG | HBB: c.113 (T > A) | 1 | 0.12 |

| CD 113 GTG > GAG | HBB: c.341 (T > A) | 1 | 0.12 |

| Total | 848 | 100 |

Migration-related thalassemia

Demographic analysis of 2,264 thalassemia cases identified 186 imported cases, with the highest proportion originating from Guizhou, Guangxi, and Guangdong. A subset of these cases was traced to northern China, a region historically characterized by a low prevalence of thalassemia, such as Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shanxi, Xinjiang(Table 7). Within the nine thalassemia cases of foreign origin, eight were from Southeast Asia. The most common imported genotypes were --SEA/αα, βIVS-II-654/βN, and βCD41–42/βN. Significantly, the identified thalassemia mutations included βIVS-I-5 and βCD14–15, both of non-local origin and potentially introduced through population migration.

Table 7.

Geographic distribution and genetic variants of migration-related thalassemia

| Geographic Origin | Number of cases(n) | Constituent ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Guizhou | 43 | 23.12 |

| Guangxi | 23 | 12.37 |

| Guangdong | 18 | 9.68 |

| Jiangxi | 17 | 9.14 |

| Sichuan | 16 | 8.60 |

| Yunnan | 14 | 7.53 |

| Hubei | 12 | 6.45 |

| Hunan | 11 | 5.91 |

| Foreign regions | 9 | 4.84 |

| Chongqing | 7 | 3.76 |

| Hainan | 5 | 2.69 |

| Zhejiang | 3 | 1.61 |

| Henan | 2 | 1.08 |

| Heilongjiang | 1 | 0.54 |

| Jilin | 1 | 0.54 |

| Jiangsu | 1 | 0.54 |

| Shanxi | 1 | 0.54 |

| Shaanxi | 1 | 0.54 |

| Xinjiang | 1 | 0.54 |

| Total | 186 | 100 |

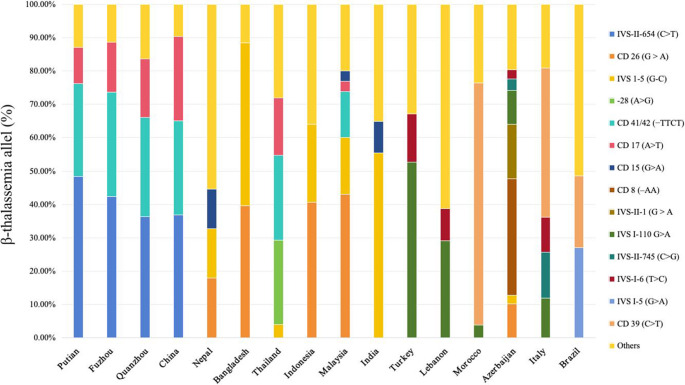

Comparison of thalassemia mutation spectrum between Putian and other global populations countries

We collected data from the literature on α- and β-thalassemia gene distributions across global regions, ultimately selecting studies from Asia, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, Africa and South America based on predefined inclusion criteria [9, 17–35]. α-Thalassemia data were primarily derived from Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Mediterranean coastal regions. Within the surveyed areas, α-thalassemia genotypes were predominantly deletion types. -α3.7 deletion was the only genotype universally present, with its prevalence decreasing progressively from the Mediterranean coast to Asia. While --SEA, -α3.7, and -α4.2 dominate in Putian (similar to Fuzhou/Quanzhou), this pattern is consistent across China and Vietnam, with Vietnam exhibiting higher --SEA prevalence. Significantly, --SEA demonstrates strict endemicity to East/Southeast Asia, with no documentation in European or Caucasian-inhabited West Asian regions (Iran, Azerbaijan) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the α-thalassemia mutation spectrum between Putian and other global populations

The β-thalassemia mutation profile in Putian resembles those of other coastal cities in Fujian Province (e.g., Fuzhou and Quanzhou) but diverges from the national pattern of China. Notably, the Chinese profile is distinct from those found in South Asia (e.g., Nepal and Bangladesh) but shows similarities to profiles in certain Southeast Asian countries (e.g., Indonesia and Malaysia). Globally, β-thalassemia demonstrates greater mutational diversity than α-thalassemia. Distinct, region-specific spectra of β-globin mutations characterize high-prevalence areas, including the Mediterranean, Middle East, Southeast Asia, Americas, and southern China. (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the β-thalassemia mutation spectrum between Putian and other global populations

DISCUSSION

Thalassemia represents the most common inherited hemoglobinopathy in southern China, posing a substantial public health burden. Affected individuals require lifelong therapeutic regimens involving regular blood transfusions and iron chelation therapy, generating considerable healthcare expenditures and socioeconomic impacts. These challenges underscore the imperative for effective preventive strategies. Cyprus has achieved a remarkable decline in the birth rate of severe thalassemia cases requiring lifelong transfusions by implementing systematic population screening combined with prenatal diagnostic interventions [33]. This paradigm highlights the efficacy of genotype-informed prevention strategies adapted to regional epidemiological profiles.

Epidemiological data reveal significant regional variations in thalassemia prevalence: the prevalence in Putian City (3.85%) is comparable to that in Fuzhou (4.10%) and Quanzhou (3.06%) within Fujian Province but is markedly lower than in the Hainan (5.11%) and Guangxi (6.66%) regions [34–36]. Crucially, the absence of systematic molecular characterization in Putian has impeded the development of optimized, population-specific screening algorithms. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted the first comprehensive molecular profiling of thalassemia variants in Putian using advanced genotyping platforms. This study, for the first time, employs genetic testing techniques to delineate the thalassemia mutation spectrum in Putian, aiming to identify all genotype variants associated with thalassemia in the region. The findings will provide a scientific basis for developing precision prevention and control strategies tailored to the local molecular characteristics.

In our study, among 6,380 participants, 2,264 (35.49%) carriers were identified. This marked discrepancy between 35.49% and 3.85% can be attributed to the inclusion of highly suspected cases from departments such as prenatal diagnosis and hematology, which do not accurately represent the overall carrier rate in the general population. Participants from the reproductive medicine department, comprising couples undergoing assisted reproductive treatment, exhibited a significantly lower carrier rate of only 8.65%. Notably, the thalassemia carrier rate among infertile couples in Putian is twice that of the general population. Thalassemia impacts fertility through multifaceted mechanisms, with iron overload being a predominant factor. Iron overload may inflict damage on the pituitary gland, a pivotal regulator of endocrine homeostasis and reproductive function [37, 38]. Such damage can impair the secretion of gonadotropins, including luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) [39]. These hormones play indispensable roles in ovulation in females and spermatogenesis in males. In female patients, this dysregulation may manifest as anovulation or menstrual irregularities, whereas in male patients, it can lead to defective spermatogenesis and diminished sperm quality. Collectively, these endocrine disturbances significantly contribute to the fertility challenges observed in individuals with thalassemia.

Among the 1,418 α-thalassemia cases identified, the predominant mutations were --SEA/αα and -α3.7/αα. The molecular profile of α-thalassemia mutations in Putian aligns closely with data reported from neighboring regions such as Guangdong and Hubei provinces, yet exhibits significant divergence from that observed in Hainan [40, 41]. It is noteworthy that the --SEA/-α3.7 genotype ranks third in terms of α-thalassemia genotype frequency. While the --SEA/αα and -α3.7/αα genotypes are generally associated with mild clinical manifestations, with some individuals even remaining asymptomatic, the --SEA/α3.7 genotype can lead to hemoglobin H disease (HbH disease), a form of intermediate thalassemia. Patients with HbH disease typically exhibit no obvious symptoms at birth; however, as they age, they may gradually develop anemia, jaundice, and even hemolytic crises. Consequently, routine blood tests alone are insufficient to determine whether a newborn carries the --SEA/-α3.7 genotype. Given the relatively high prevalence of --SEA/-α3.7 carriers in the Putian region, genetic testing is recommended as a screening tool for neonates in high-risk populations. This approach facilitates early diagnosis and timely intervention for thalassemia-affected children, thereby preventing missed diagnoses.

The predominant α-thalassemia gene mutations are deletion types, specifically --SEA, -α3.7, and -α4.2. These three mutations constitute 92.7% of all α-thalassemia mutations, with the --SEA type being the most prevalent, accounting for 71.79% of cases. If one parent carries the --SEA mutation while the other possesses either the α+-thalassemia deletion or --SEA, there is a 25% probability that the fetus may develop Hb H disease or Hb Bart’s hydrops fetalis. This finding indicates a relatively higher risk of Hb H disease and Hb Bart’s hydrops fetalis in the Putian region, underscoring the need for close monitoring. Furthermore, our study identified several rare α-thalassemia mutations that are infrequently reported in China. The most common allele frequencies of non-deletion α-thalassemia are observed in ααCS (2.35%), while ααWS and ααQS exhibit similar frequencies at 1.89% and 1.69%, respectively. A total of nine rare α-thalassemia mutations were identified. Among these, αααanti4.2 was the most prevalent, detected in six cases. In addition, a single case of the αααanti3.7 triplet mutation was identified. The --THAI mutation, which is more commonly observed in Thailand [42], was detected in six cases, including two instances of compound heterozygosity involving other mutations.

In contrast to the Middle East and Mediterranean regions [33], the incidence of β-thalassemia in Putian is lower than that of α-thalassemia, with a ratio of 1:1.76. This study identified a total of 807 cases of β-thalassemia, encompassing 18 mutation types. The predominant genotypes were βIVS-II-654/βN, βCD 41–42/βN, and βCD 17/βN, with βIVS-II-654 and βCD 41–42 being the most frequent mutations. Despite its proximity to Southern China [43], the mutational spectrum of β-thalassemia in Putian demonstrates greater similarity to that of Hubei, a geographically more distant region, characterized by a higher frequency of IVS-II-654 (C > T) compared to CD 41–42 (-CTTT) [44]. Of note, although the number of β-thalassemia genotypes in Putian is fewer than those of α-thalassemia, the mutation types are more diverse, demonstrating significant genetic heterogeneity. This suggests a potential higher occurrence of intermediate β-thalassemia, which could impose a greater burden on local public health.

Co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia represents a complex form of thalassemia, typically characterized by microcytic and hypochromic anemia [40, 45]. Although clinical manifestations are generally mild, ranging from mild anemia to normal hemoglobin levels, hemoglobin electrophoresis results closely resemble those of β-thalassemia, which may lead to misdiagnosis if only hematological screening is performed [46–48]. According to Mendel’s law, while matings between α-thalassemia heterozygotes and β-thalassemia heterozygotes do not carry a risk of severe thalassemia, matings between individuals with co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia and heterozygotes of either α- or β-thalassemia may result in severe cases. Similar to observations in Malaysia, our study identified the --SEA deletion as the most frequent mutation in co-inheritance of α- and β-thalassemia, highlighting a significant risk of underdiagnosis of Hb Bart’s hydrops fetalis syndrome [49].

In recent years, rapid economic development has driven increasingly frequent population migration, significantly altering the local thalassemia gene mutation spectrum due to immigration. Our study revealed that the majority of local foreign patients with thalassemia are from Southeast Asia. Additionally, imported thalassemia cases primarily originate from Guizhou, Guangxi, Guangdong, Jiangxi, and Sichuan. A large proportion of migrants in Putian come from Guizhou, Jiangxi, and Sichuan. Although these regions are not high-prevalence areas for thalassemia, their significant proportion among the local migrant population necessitates targeted prevention and control measures to mitigate the risk of thalassemia transmission. Two novel mutation types introduced by migrant populations were identified.

This study demonstrates that β-thalassemia exhibits a significantly wider geographic distribution compared to α-thalassemia. Specifically, α-thalassemia displays a pronounced regional clustering pattern, being predominantly prevalent in Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean basin, whereas β-thalassemia extends its distribution to additional continents, including the Americas. Notably, the mutational spectra of both disorders present distinct region-specific signatures, with the degree of genetic divergence showing a positive correlation with geographic distance. In Putian, the α-thalassemia genotype profile closely resembles that of neighboring Vietnam but differs substantially from the European mutational landscape [18]. Azerbaijan, geographically positioned at the Eurasian crossroads, harbors thalassemia variants prevalent in both European and Asian populations [24]. Furthermore, characteristic genotypes were identified in most surveyed regions, including αConstant Spring in Malaysia, α20.5 in Azerbaijan, and the 619-bp deletion in India [19, 24, 27].

PCR-flow-through hybridization is limited to detecting a small number of common genotypes. It may fail to identify new mutations, thereby inadequately meeting the demands of thalassemia gene screening. Apart from the triple mutation, all other rare variants detected in this study were identified through sequencing. Despite its accuracy, the high cost of sequencing remains a significant barrier, limiting its accessibility for many individuals. There is an urgent need to develop a rapid, cost-effective, and comprehensive detection method capable of covering a wider range of gene mutations for thalassemia diagnosis. Such a method would greatly support thalassemia prevention and control programs and help reduce the incidence of thalassemia.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we confirmed that the thalassemia gene mutation spectrum in Putian differs from that of other regions worldwide, demonstrating significant genotypic diversity and population heterogeneity. Meanwhile, we found that the prevalence of thalassemia is higher in the local infertile population compared to the general population. These findings provide valuable data to support thalassemia prevention and control efforts, as well as genetic counseling in this region.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to EditSprings (https://www.editsprings.cn) for the expert linguistic services provided.

Author contributions

Guanghui Xu and Kun Lin collected the data. Liumin Yu, Zhanfei Chen, Jinqiu Li and Hua Lin wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Project Plan of Putian City (2023S3F0010), the Research Foundation of Putian University (2021038,2024112), and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2023J011700, 2022J011443).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures were performed according to the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Putian University(2023068).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Taher AT, Musallam KM, Cappellini MD (2021) β-Thalassemias. N Engl J Med 384(8):727–743. 10.1056/NEJMra2021838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baird DC, Batten SH, Sparks SK (2022) Alpha- and Beta-thalassemia: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician 105(3):272–280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taher AT, Weatherall DJ, Cappellini MD (2018) Thalassaemia. Lancet 391(10116):155–167. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rachmilewitz EA, Giardina PJ, How I, Treat Thalassemia (2011) Blood 118(13):3479–3488. 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrari G, Thrasher AJ, Aiuti A (2021) Gene therapy using haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat Rev Genet 22(4):216–234. 10.1038/s41576-020-00298-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.: For the Management of Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia (TDT), 4th ed.; Cappellini MD, Farmakis D, Porter J, Taher A (eds) (2021) ; Thalassaemia International Federation: Nicosia (Cyprus), 2023 [PubMed]

- 7.Khaliq S (2022) Thalassemia in Pakistan. Hemoglobin 46(1):12–14. 10.1080/03630269.2022.2059670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bach KQ, Nguyen HTT, Nguyen TH, Nguyen MB, Nguyen TA (2022) Thalassemia Viet Nam Hemoglobin 46(1):62–65. 10.1080/03630269.2022.2069032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paiboonsukwong K, Jopang Y, Winichagoon P, Fucharoen S (2022) Thalassemia in Thailand. Hemoglobin 46(1):53–57. 10.1080/03630269.2022.2025824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canatan D (2014) Thalassemias and hemoglobinopathies in Turkey. Hemoglobin 38(5):305–307. 10.3109/03630269.2014.938163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piel FB, Weatherall DJ (2014) The α-Thalassemias. N Engl J Med 371(20):1908–1916. 10.1056/NEJMra1404415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuo Y, Li Y, Li Y, Global Regional, and National burden of thalassemia, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021, 2024. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102619. PubMed PMID: 38745964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Motta I, Bou-Fakhredin R, Taher AT, Cappellini MD (2020) Beta thalassemia: new therapeutic options beyond transfusion and iron chelation. Drugs 80(11):1053–1063. 10.1007/s40265-020-01341-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kattamis A, Kwiatkowski JL, Aydinok Y (2022) Thalassaemia. Lancet 399(10343):2310–2324. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00536-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad R, Saleem M, Aloysious NS, Yelumalai P, Mohamed N, Hassan S (2013) Distribution of alpha thalassaemia gene variants in diverse ethnic populations in Malaysia: data from the Institute for Medical Research. Int J Mol Sci 14(9):18599–18614. 10.3390/ijms140918599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou C, Du Y, Zhang H, Wei X, Li R, Wang J (2024) Third-generation sequencing identified a novel complex variant in a patient with rare Alpha-Thalassemia. BMC Pediatr 24(1):330. 10.1186/s12887-024-04811-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alibakhshi R, Moradi K, Aznab M, Dastafkan Z, Tahmasebi S, Ahmadi M, Omidniakan L (2020) The spectrum of α-Thalassemia mutations in Kurdistan province, West Iran. Hemoglobin 44(3):156–161. 10.1080/03630269.2020.1768863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim BT, Phu Chi L, Hoang Thanh D (2016) Spectrum of common α-globin deletion mutations in the Southern region of Vietnam. Hemoglobin 40(3):206–207. 10.3109/03630269.2016.1166126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yatim N, Rahim M, Menon K, Al-Hassan F, Ahmad R, Manocha A, Saleem M, Yahaya B (2014) Molecular characterization of α- and β-thalassaemia among Malay patients. Int J Mol Sci 15(5):8835–8845. 10.3390/ijms15058835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhuthali HM, Ataya EF, Alsalmi A, Elmissbah TE, Alsharif KF, Alzahrani HA, Alsaiari AA, Allahyani M, Gharib AF, Qanash H, Elmasry HM, Hassanein DE (2023) Molecular patterns of Alpha-Thalassemia in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: identification of prevalent genotypes and regions with high incidence. Thromb J 21(1):115. 10.1186/s12959-023-00560-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamoon RP (2020) Molecular spectrum of α-thalassemia mutations in Erbil Province of Iraqi Kurdistan. Mol Biol Rep 47(8):6067–6071. 10.1007/s11033-020-05681-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murad H, Moassas F, Ali B, Katranji E, Mukhalalaty Y (2023) The spectrum of α-thalassemia mutations in Syrian patients. Hemoglobin 47(6):245–248. 10.1080/03630269.2023.2296927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorello P, Arcioni F, Palmieri A, Barbanera Y, Ceccuzzi L, Adami C, Marchesi M, Angius A, Minelli O, Onorato M, Piga A, Caniglia M, Mecucci C, Roetto A (2016) The molecular spectrum of β- and α-thalassemia mutations in non-endemic Umbria, central Italy. Hemoglobin 40(6):371–376. 10.1080/03630269.2017.1289101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aliyeva G, Asadov C, Mammadova T, Gafarova S, Guliyeva Y, Abdulalimov E (2020) Molecular and geographical heterogeneity of hemoglobinopathy mutations in Azerbaijanian populations. Ann Hum Genet 84(3):249–258. 10.1111/ahg.12367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtoğlu A, Karakuş V, Erkal Ö, Kurtoğlu E (2016) β-Thalassemia gene mutations in antalya, turkey: results from a single centre study. Hemoglobin 40(6):392–395. 10.1080/03630269.2016.1256818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silva ANLM, Cardoso GL, Cunha DA, Diniz IG, Santos SEB, Andrade GB, Trindade SMS, Cardoso MDSO, Francês LTVM, Guerreiro JF (2016) The spectrum of β -thalassemia mutations in a population from the Brazilian Amazon. Hemoglobin 40(1):20–24. 10.3109/03630269.2015.1083443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colah RB (2022) T. Seth Thalassemia in India. Hemoglobin 46 1 20–26 10.1080/03630269.2021.2008958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernaningsih Y, Syafitri Y, Indrasari YN, Rahmawan PA, Andarsini MR, Lesmana I, Moses EJ, Abdul Rahim NA, Yusoff NM (2022) Analysis of common Beta-Thalassemia (β-Thalassemia) mutations in East Java, Indonesia. Front Pediatr 10:925599. 10.3389/fped.2022.925599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farra C, Abdouni L, Souaid M, Awwad J, Yazbeck N, Abboud M (2021) The spectrum of β-Thalassemia mutations in the population migration in lebanon: a 6-year retrospective study. Hemoglobin 45(6):365–370. 10.1080/03630269.2021.1920975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lama R, Yusof W, Shrestha TR, Hanafi S, Bhattarai M, Hassan R, Zilfalil BA (2022) Prevalence and distribution of major β-thalassemia mutations and HbE/β-thalassemia variant in Nepalese ethnic groups. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 15(1):14–20. 10.1016/j.hemonc.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aziz MA, Khan WA, Banu B, Das SA, Sadiya S, Begum S (2020) Prenatal diagnosis and screening of thalassemia mutations in Bangladesh: presence of rare mutations. Hemoglobin 44(6):397–401. 10.1080/03630269.2020.1830797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belmokhtar I, Lhousni S, Elidrissi Errahhali M, Ghanam A, Elidrissi Errahhali M, Sidqi Z, Ouarzane M, Charif M, Bellaoui M, Boulouiz R, Benajiba N (2022) Molecular heterogeneity of Β-thalassemia variants in the Eastern region of Morocco. Mol Genet Genomic Med 10(8):e1970. 10.1002/mgg3.1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musallam KM, Lombard L, Kistler KD Epidemiology of clinically significant forms of alpha- and beta‐thalassemia: a global map of evidence and gaps. Am J Hematol. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/ajh.27006 (accessed 2025-03-01) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Shang X, Zhang X, Yang (2020) [Clinical practice guidelines for Alpha-Thalassemia]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi Zhonghua Yixue Yichuanxue Zazhi chin. J Med Genet 37(3):235–242. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2020.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Writing Group For Practice Guidelines For Diagnosis And Treatment Of Genetic Diseases Medical Genetics Branch Of Chinese Medical Association, Shang N, Wu X, Zhang X, Feng X, Xu X (2020) [clinical practice guidelines for beta-thalassemia]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi Zhonghua Yixue Yichuanxue Zazhi Chin J Med Genet 37(3):243–251. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.XU L, Huang H, Wang Y Molecular epidemiological analysis of α-and β-Thalassemia in Fujian province, 2013. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Lin J (2022) Fang cong; Liao jiayun; Zeng haitao. A case of fertility preservation in a prepubertal patient with thalassemia major and review of relevant literature. Chin J Reprod Contracep 42(2):183–187. 10.3760/cma.j.cn101441-20200709-00388 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castaldi MA, Cobellis L, Thalassemia, Infertility (2016) Hum Fertil 19(2):90–96. 10.1080/14647273.2016.1190869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uysal A, Alkan G, Kurtoğlu A, Erol O, Kurtoğlu E (2017) Diminished ovarian reserve in women with Transfusion-Dependent Beta-Thalassemia major: is iron gonadotoxic?? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 216:69–73. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xian J, Wang Y, He J, Li S, He W, Ma X, Li Q (2022) Molecular epidemiology and hematologic characterization of thalassemia in Guangdong province, Southern China. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis 28:107602962211198. 10.1177/10760296221119807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Lu Z, Xiao M (2022) Prevalence and genetic analysis of thalassemia in childbearing age population of Hainan, the free trade Island in Southern China. J Clin Lab Anal. 10.1002/jcla.24260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jomoui W, Panyasai S, Sripornsawan P, Tepakhan W (2023) Revisiting and updating molecular epidemiology of α-thalassemia mutations in Thailand using MLPA and new multiplex Gap-PCR for nine α-thalassemia deletion. Sci Rep 13(1):9850. 10.1038/s41598-023-36840-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng Q, Zhang Z, Li S, Cheng C, Li W, Rao C, Zhong B, Lu X (2021) Molecular epidemiological and hematological profile of thalassemia in the Dongguan region of Guangdong province, Southern China. J Clin Lab Anal. 10.1002/jcla.23596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu Y, Shen N, Wang X, Xiao J, Lu Y (2020) Alpha and beta-thalassemia mutations in Hubei area of China. BMC Med Genet 21(1):6. 10.1186/s12881-019-0925-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu Y, Wang W, Liu A Clinical characteristics analysis of 10 children with Αβ-Thalassemia in Wuhan area, 2022. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5323.2022.03.008

- 46.Xiong F, Lou J, Wei X Analysis of hematological characteristics on the 79 Co-Inheritance of α-Thalassemia and β-Thalassemia carriers in guangxi, 2012. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2012.10.017 [PubMed]

- 47.Li W, Chen LT, Yu Y, Wang J, Li CY, Cai TE, Lu CJ, Li DX, Tian XJ (2023) [Molecular genetic characteristics of a family which coinheritance of Rare-88 C > G (HBB:C.-138 C > G) β-Thalassemia mutation with α-Thalassemia and review of the literature]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 57(2):253–258. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220818-00823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panyasai S, Jaiping K, Pornprasert S (2015) Elevated hb A₂ levels in a patient with a compound heterozygosity for the (Β+) -31 (a > G) and (Β0) codon 17 (a > T) mutations together with a single α-Globin gene. Hemoglobin 39(4):292–295. 10.3109/03630269.2015.1047513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wee YC, Tan KL, Kuldip K, Tai KS, George E, Tan PC, Chia P, Subramaniam R, Yap SF, Tan J (2008) a. M. A. Alpha-Thalassaemia in association with Beta-Thalassaemia patients in malaysia: A study on the Co-Inheritance of both disorders. Community Genet 11(3):129–134. 10.1159/000113874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.