Abstract

Autoantibodies associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are often present in patients with a variety of autoimmune diseases, affecting the diagnosis and differentiation of the diseases. In this study, the positive rates and diagnostic efficiencies of anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies were analysed in 216 SLE patients, 323 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, 87 Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) patients, 45 patients with other autoimmune diseases (OAD) and 52 healthy controls (HC). In addition to being high in SLE patients, the serum levels of anti-dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies were also significantly higher in SS patients compared with OAD (P = 0.008, < 0.001). The ROC-AUCs for the four SLE-associated autoantibodies in distinguishing SLE patients from SS patients were lower than those in distinguishing SLE patients from HC. Therefore, SLE-associated autoantibody-positive SS patients represent a less studied and heterogeneous population, as these antibodies are also present in approximately 15% of all SS patients. Compared with SLE-associated autoantibody-negative SS patients, SS patients who were positive for SLE-associated autoantibodies were more likely to be positive for anti-nRNP/Sm autoantibodies (30.77% vs. 4.05%, P = 0.001). Oral ulcerations, rampant dental and pulmonary involvement were more frequent in SS patients who were positive for SLE-associated autoantibodies than in those who were negative for these autoantibodies (P = 0.018, 0.004 and < 0.001). In conclusion, SLE-associated autoantibody-positive SS patients represent a heterogeneous population, characterized by unique autoantibody profiles and clinical manifestations. This study may provide new insights for diagnostic refinement between SLE and SS patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-21039-w.

Subject terms: Biomarkers, Autoimmunity

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by immune system activation and the loss of immune tolerance to self-antigens, resulting in the immune system attacking healthy cells and tissues throughout the body. Depending on the amount of antibodies produced, the location of immune complexes and the degree of cytokine and complement activation, the clinical manifestations of patients can range from mild fatigue and arthritis to a wide range of life-threatening organ damage involving the kidneys, skin, blood, and nervous system1.

A variety of autoantibodies, such as anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-Sm, anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies, have been shown to be prevalent in patients with SLE. The detection of autoantibodies is crucial for assisting in the diagnosis and assessment of SLE activity. The presence and levels of these autoantibodies are highly correlated with disease progression. For example, the presence of anti-dsDNA antibodies has high specificity in the diagnosis of SLE, as these autoantibodies are present in 65–70% of SLE patients, whereas they are present in only 0.5% of healthy individuals2. The level of anti-dsDNA antibodies is also a key autoantibody biomarker for disease activity. Anti-dsDNA antibodies and anti-C1q antibodies have been confirmed histologically in renal biopsy samples and are strongly associated with lupus nephritis. Anti-nucleosome antibodies are most closely related to cutaneous lupus and lupus nephritis3. Anti-ribosomal P antibodies are highly specific for SLE, occurring in approximately 15% of SLE patients, and their presence is accompanied by neurological involvement4–6. Although numerous studies have previously demonstrated that all four antibodies are hallmark antibodies for SLE, the comparative diagnostic value of these antibodies and their detection rates and discriminatory ability in patients with other connective tissue diseases have not been addressed.

To determine these enigmatical issues, in this study, we explored the serological levels of four autoantibodies, namely, anti-nucleosome, anti-dsDNA, anti-C1q and anti-ribosomal P antibodies, in patients with different autoimmune diseases and compared the diagnostic value of these autoantibodies in patients with connective tissue diseases. The associations of the serological levels of these autoantibodies with clinical phenotypes were evaluated and compared to obtain a more thorough understanding of the clinical value of lupus-specific autoantibodies.

Materials and methods

Study population

Retrospective data from 216 SLE patients, 323 RA patients, 87 SS patients, 45 patients with other autoimmune diseases (OAD) and 52 healthy controls (HC) were collected from the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology of the Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University between January 2021 and December 2022. Among the 45 OAD patients, 11 subjects were systemic sclerosis and 34 subjects were idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cancer or overlap syndrome were not included in this study. Demographic characteristics and laboratory findings were recorded. A total of 216 SLE patients were in line with 1997 American College of Rheumatology criteria for SLE in 19977–9. A total of 323 RA patients were diagnosed according to the European League Against Rheumatism 2017 criteria10. Eighty-seven patients with SS fulfilled the American-European Consensus Group in 2002 for SS11. The demographic characteristics and autoantibody positivity rates in the study population are presented in Table 1. The Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University approved this study (XJS2024-104-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their families. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and positive rate of autoantibodies of participants.

| SLE(n = 216) | RA(n = 323) | SS(n = 87) | OAD(n = 45) | HC(n = 52) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years), mean (range) | 44(14–79) | 60(24–88) | 57(28–75) | 58(33–83) | 43(21–85) |

| Female, n (%) | 195(90.28%) | 267(82.66%) | 85(97.70%) | 37(82.22%) | 48(92.31%) |

| Auto-Abs, n(%) | |||||

| Anti-dsDNA | 114,(52.78%) | 1,(0.31%) | 8,(9.20%) | 0,(0%) | 2,(3.85%) |

| Anti-Nucl | 97,(44.91%) | 6,(1.86%) | 8,(9.20%) | 1,(2.22%) | 1,(1.92%) |

| Anti-Rib P | 38,(17.59%) | 3,(1.39%) | 2,(2.30%) | 1,(2.22%) | 1,(1.92%) |

| Anti-C1q | 33,(15.28%) | 5,(1.55%) | 1,(1.15%) | 0,(0%) | 1,(1.92%) |

| ANA positivity | - | ||||

| ≤ 1:100 ANA (n, %) | 19,(8.80%) | 151,(46.75%) | 11,(12.64%) | 23,(51.11%) | - |

| 1:320 ANA (n, %) | 38,(17.59%) | 106,(32.82%) | 12,(13.79%) | 6,(13.33%) | - |

| 1:1000 ANA (n, %) | 71,(32.87%) | 53,(16.41%) | 45,(51.72%) | 9,(20.00%) | - |

| ≥ 1:3200 ANA (n, %) | 88,(40.74%) | 13,(4.02%) | 19,(21.84%) | 7,(15.56%) | - |

Abs: antibodies; Anti-dsDNA: anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies; Anti-Nucl: anti-nucleosome antibodies; Anti-Rib P: anti-ribosomal P antibodies; Anti-C1q: anti-c1q antibodies; ANA: antinuclear antibody

The detection of autoantibodies

The determination of positivity for four SLE-associated autoantibodies (anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies) was performed via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (EUROIMMUN Diagnostics). In accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions, the cut-off value for anti-dsDNA antibody positivity was a level of more than 100 IU/ml, and the cut-off values of positivity for the other three autoantibodies were levels of more than 20 RU/ml. The detection of antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer was performed by immunofluorescence assay (EUROIMMUN Diagnostics). The determination of positivity for Anti- Extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) antibodies (anti-SSA, anti-SSB, anti-nRNP/Sm, anti-Sm, anti- Scl-70, anti- Ro52, anti- Jo-1, anti-CENP-B) was performed by immunoblotting (EUROIMMUN Diagnostics). All samples for autoantibodies detection were tested at Dalian Key Laboratory of Autoantibody Detection in a routine clinical setting.

The evaluation of clinical manifestations

Clinical features were defined as follows. Xerostomia is defined as a persistent sensation of dryness in the oral cavity. Xerophthalmia refers to refers to persistent dryness of the ocular surface (cornea and conjunctiva), which is confirmed by Schirmer’s test or corneal staining. Oral ulcers refer to painful ulcerative lesions that occur on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, such as the inner lips, upper palate, tongue, and buccal mucosa. Rampant dental is characterized by the simultaneous development of dental caries on multiple teeth and multiple tooth surfaces within a short period, causing the teeth to turn black, flake off, and leave only residual roots. Raynaud’s phenomenon is characterized by intermittent pallor, cyanosis, and flushing of the skin on the fingers and/or toes, which occurs due to exposure to cold environments or stress-induced stimuli. Myositis is defined as myalgia, muscle weakness, elevated serum levels of creatine kinase (CK) or myogenic pattern assessed by electroneuromyography (ENMG), imaging, muscle biopsy. Articular involvement is defined as polyarticular pain (≥ 3 joints), associated with swelling and/or reduced passive/active mobility, assessed by clinical examination and validated via imaging. Mucocutaneous involvement includes malar rash, discoid rash and photosensitivity. Haematological involvement includes hemolysis, leukopenia (<4,000/mm3), lymphopenia (<1,500/mm3), and thrombocytopenia (<100,000/mm3). Nephrological involvement includes renal tubular acidosis, glomerulonephritis, pulmonary hypertension and chronic interstitial nephritis. Pulmonary involvement includes airway lesions, interstitial lung disease, and pleuritis. Neurological involvement includes cognitive impairment, depression, epilepsy, and peripheral neuropathy.

Results

SLE-associated autoantibodies in HC, SLE, RA, SS and OAD patients

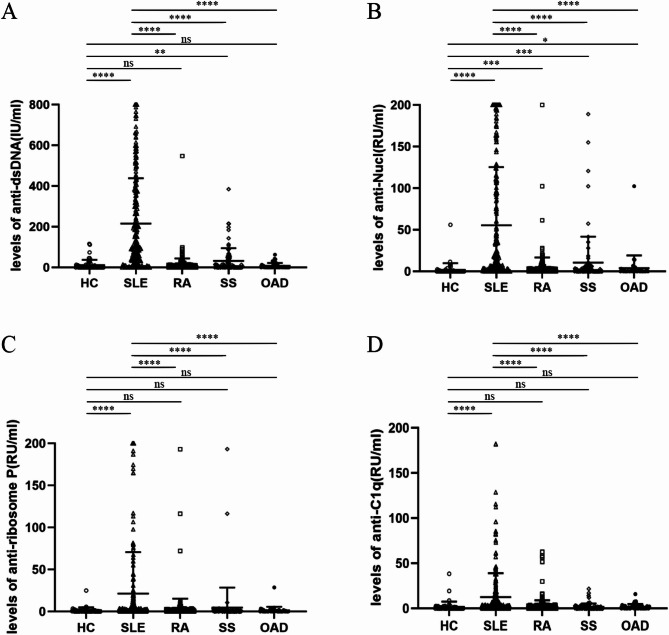

The levels of four SLE-associated autoantibodies in HC, SLE, RA, SS and OAD patients are presented in Fig. 1. Among the cohort of 216 SLE patients, 114 (52.78%) were positive for anti-dsDNA antibodies, 97 (44.91%) were positive for anti-nucleosome antibodies, 38 (17.59%) were positive for anti-ribosomal P antibodies, and 33 (15.28%) were positive for anti-C1q antibodies positive. In the cohort of 323 RA patients, only one patient (0.31%) was positive for anti-dsDNA antibodies, 6 patients (1.86%) were positive for anti-nucleosome antibodies, 3 patients (0.92%) were positive for anti-ribosomal P antibodies, and 5 patients (1.55%) were positive for anti-C1q antibodies. Among the 87 SS patients, 8 (9.20%) were positive for anti-dsDNA antibodies, 8 (9.20%) were positive for anti-nucleosome antibodies, 2 (2.30%) were positive for anti-ribosomal P antibodies, and 1 (1.15%) was positive for anti-C1q antibodies. Among the 45 OAD patients, 0 (0%), 1 (2.22%), 1 (2.22%) and 0 (0%) were positive for anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-ribosomal P antibodies and anti-C1q antibodies, respectively. Among the 52 healthy controls, 2 (3.85%), 1 (1.92%), 1 (1.92%) and 1 (1.92%) were positive for anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies, respectively; these values were similar to the RA group and OAD group.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of serum levels of four autoantibodies in SLE, RA, SS, OAD patients and HC. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; P < 0.0001.

The serum levels of anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies were significantly higher in SLE patients than in healthy controls and patients with other connective tissue diseases. Unexpectedly, higher proportions of SS patients were positive for anti-dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies compared with the HC group (P = 0.008, < 0.001). Additionally, higher proportions of RA patients were positive for anti-nucleosome antibodies, and the difference from the HC group was statistically significant (P < 0.001). In contrast, the levels of these autoantibodies in the OAD group were not significantly different from those in the healthy control group. Serum levels of anti-ribosomal P antibodies and anti-C1q antibodies were not significantly different between healthy controls and patients with connective tissue diseases other than SLE patients.

Evaluation of the diagnostic performance of the four SLE-associated autoantibodies using healthy controls or different connective tissue disease as a control group

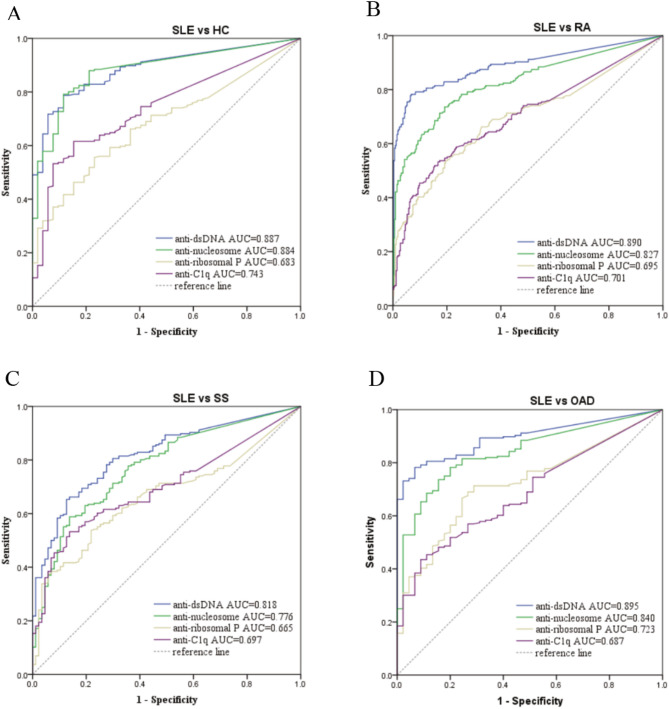

To explore the diagnostic performance of four autoantibodies in differentiating healthy controls or patients with other connective tissue diseases from patients with SLE, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed (Fig. 2). The ROC-AUCs for anti‐dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies in differentiating SLE patients from healthy controls were 0.887 and 0.884, respectively, whereas the ROC‐AUCs for anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies in differentiating these groups were only 0.683 and 0.743, respectively. Although the sensitivities of anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies were significantly lower than the sensitivities of anti‐dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies, the specificities of all four SLE-associated autoantibodies were above 95% (Supplementary Table S1). The AUCs for anti-nucleosome and anti-C1q antibodies in distinguishing SLE from RA were reduce to 0.827 and 0.701, respectively. In addition, there was no significant difference in the AUCs for anti‐dsDNA and anti-ribosomal P antibodies in distinguishing SLE patients from RA patients. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the AUCs for these antibodies in differentiating SLE patients from HC or patients with OAD.

Fig. 2.

ROC analysis of the four autoantibodies for the detection of SLE or other autoimmune disease. (A)ROC for SLE versus HC (B) ROC for SLE versus RA. (C) ROC for SLE versus SS. (D) ROC for SLE versus OAD.

However, the ROC-AUCs of anti‐dsDNA antibodies, anti-nucleosome antibodies, anti-ribosomal P antibodies and anti-C1q antibodies in differentiating SLE patients from SS patients were drastically lower than those in differentiating SLE patients from HC, decreasing to 0.818, 0.776, 0.665, and 0.697, respectively. To further explore the decrease in diagnostic performance when we used patients with SS as a control group, the specificity was set at 95% for each test. The cut-off values for anti‐dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies needed to be doubled, whereas the cut-off values for anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies were close to the manufacturers’ cut-off values (Table 2). At a specificity of 95%, the sensitivity of anti‐dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies decreased significantly (41.20% and 32.87%, respectively). Overall, SLE-associated autoantibodies are present in patients with other rheumatological diseases, especially SS patients, which has a major impact on diagnostic efficiency. If a patient with SS is positive for SLE-associated autoantibodies, the cut-off value needs to be increased appropriately.

Table 2.

Performance of the four autoantibodies in differentiating SLE patients from SS patients when specificity is set to 95%.

| Antibody | Cut Off | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-dsDNA | 100 | 52.78% | 90.80% | ||

| Anti-Nucl | 20 | 44.91% | 90.80% | ||

| Anti-Rib P | 20 | 17.59% | 97.70% | ||

| Anti-C1q | 20 | 15.28% | 98.85% | ||

| Specificity of assays is defined at 95% | |||||

| Anti-dsDNA | 188 | 41.20% | 95.40% | ||

| Anti-Nucl | 58 | 32.87% | 95.40% | ||

| Anti-Rib P | 20 | 17.59% | 97.70% | ||

| Anti-C1q | 20 | 15.28% | 98.85% | ||

Anti-dsDNA: anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies; Anti-Nucl: anti-nucleosome antibodies; Anti-Rib P: anti-ribosomal P antibodies; Anti-C1q: anti-c1q antibodies

Biological characteristics of patients with SS and comparisons between SS patients with and without SLE-associated autoantibodies

SS patients were divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of SLE-associated antibodies. SS patients with positive SLE-associated autoantibodies are defined as those test positive for at least one of the following antibodies: anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-ribosomal P, and anti-C1q antibodies. In our study, SS patients with positive SLE-associated autoantibodies accounted for approximately 15% of all SS patients. The biological characteristics of SS patients who were positive for SLE-associated autoantibodies were further analysed. Thirteen SS patients who were positive for SLE-associated autoantibodies were compared with 74 SS patients who were negative for SLE-associated autoantibodies, and the main characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 3. Most SS patients have high ANA titers. There was 1 (7.69%) patient with 1:100 ANA, 1 (7.69%) with 1:320 ANA, 5(38.46%) with 1:1000 ANA and 6(46.15%) with 1:3200 ANA in the SLE-associated autoantibody-positive group, whereas there were 10 (13.51%), 11 (14.86%), 40 (54.05%) and 13 (17.58%) SS patients with these ANA titers in the SLE-associated autoantibody-negative group, respectively (Table 3). The ANA titer in the SLE-associated autoantibody-positive group was slightly higher than that in the SLE-associated autoantibody-negative group, but the difference was not significant. Similarly, there were no obvious statistically significant differences in the rates of positivity for anti-SSA, anti-SSB, anti-Sm, anti-Scl-70, anti-Ro52, anti-Jo-1 and anti-CENP-B antibodies between the two groups. Interestingly, anti-nRNP/Sm autoantibodies were found more frequently in patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies than in those who were negative for SLE-associated autoantibodies (30.77% vs. 4.05%; P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Biological characteristics of SS patients with or without SLE-associated autoantibodies.

| Biological characteristics | All SS patients (n = 87) |

SS patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies (n = 13) |

SS patients without SLE-associated autoantibodies (n = 74) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANA positivity | 0.340 | |||

| ≤ 1:100 ANA (n, %) | 11,(12.64%) | 1,(7.69%) | 10,(13.51%) | |

| 1:320 ANA (n, %) | 12,(13.79%) | 1,(7.69%) | 11,(14.86%) | |

| 1:1000 ANA (n, %) | 45,(51.72%) | 5,(38.46%) | 40,(54.05%) | |

| ≥ 1:3200 ANA (n, %) | 19,(21.84%) | 6,(46.15%) | 13,(17.58%) | |

| Anti-ENA Abs positivity | ||||

| anti-SSA (n, %) | 64,(73.56%) | 11,(84.62%) | 53,(71.62%) | 0.330 |

| anti-SSB (n, %) | 29,(33.33%) | 4,(30.77%) | 25,(33.78%) | 0.833 |

| anti-nRNP/Sm (n, %) | 7,(8.05%) | 4,(30.77%) | 3,(4.05%) | 0.001*** |

| anti-Sm (n, %) | 1,(1.15%) | 0,(0%) | 1,(1.35%) | 0.675 |

| anti- Scl-70 (n, %) | 0,(0%) | 0,(0%) | 0,(0%) | 1.000 |

| anti- Ro52 (n, %) | 67,(77.01%) | 11,(84.62%) | 56,(75.68%) | 0.482 |

| anti- Jo-1 (n, %) | 3,(3.45%) | 1,(7.69%) | 2,(2.70%) | 0.366 |

| anti-CENP-B (n, %) | 7,(8.05%) | 0,(0%) | 7,(9.46%) | 0.250 |

Abs: antibodies; ENA: Extractable nuclear antigen; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Clinical characteristics of patients with SS and comparisons between patients with and without SLE-associated autoantibodies

We next explored the clinical characteristics of the two groups, and the results are shown in Table 4. With regard to xerostomia, xerophthalmia, Raynaud’s phenomenon and myositis, the two groups were not significantly different; however, oral ulcerations and rampant dental procedures were more common in the SS patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies group (P = 0.018, 0.004). The differences in the articular, mucocutaneous, haematological, nephrological and neurological involvement were not statistically significant. A higher rate of SLE-associated autoantibodies was observed in SS patients with pulmonary involvement than patients without SLE-associated autoantibodies (76.92% versus 17.57%, P < 0.001).

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of SS patients with or without SLE-associated autoantibodies.

| Clinical characteristics n(%) |

All SS patients (n = 87) |

SS patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies (n = 13) |

SS patients without SLE-associated autoantibodies (n = 74) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xerostomia | 82,(94.25%) | 13,(100%) | 69,(93.24%) | 0.337 |

| Xerophthalmia | 78,(89.66%) | 12,(92.31%) | 66,(89.19%) | 0.735 |

| Oral ulcerations | 14,(16.09%) | 5,(38.46%) | 9,(12.16%) | 0.018* |

| Rampant dental | 20,(22.99%) | 7,(53.85%) | 13,(17.57%) | 0.004** |

| Reynold’s phenomenon | 3,(3.45%) | 1,(7.69%) | 2,(2.70%) | 0.366 |

| Myositis | 2,(2.30%) | 0(0%) | 2,(2.70%) | 0.551 |

| Clinical manifestations | ||||

| Articular | 49,(56.32%) | 9,(69.23%) | 39,(52.70%) | 0.272 |

| Mucocutaneous | 6,(6.90%) | 1,(7.69%) | 5,(6.76%) | 0.903 |

| Haematological | 19,(21.84%) | 5,(38.46%) | 14,(18.92%) | 0.118 |

| Nephrological | 10,(11.49%) | 2,(15.38%) | 8,(10.81%) | 0.635 |

| Pulmonary | 23,(26.44%) | 10,(76.92%) | 13,(17.57%) | 0.000*** |

| Neurological | 1,(1.15%) | 0(0%) | 1,(1.35%) | 0.675 |

* P <0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001

Discussion

Anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-ribosomal P antibodies and anti-C1q antibodies are highly specific for SLE5. These autoantibodies are often detected in the serum of SLE patients, and some of them are strongly associated with cutaneous lupus, central nervous system dysfunctions or renal involvement6,7. These four antibodies are crucial for assisting in the diagnosis of SLE, and the level of anti-dsDNA is routinely utilized in clinical settings to assess SLE activity. However, previous studies of anti-dsDNA, anti‐nucleosome, anti-C1q, and anti-ribosome P antibodies have revealed that the levels of these antibodies are also high in other systemic autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome and systemic sclerosis/scleroderma8–12. In this study, we confirmed previous reports that the rates of positivity for the four SLE-associated antibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases were higher than those in healthy controls. Furthermore, we discovered that the four SLE-associated antibodies were present mainly in SS patients, and a small number of these antibodies were present in RA patients.

To explore the influence of SLE-related antibody positivity on systemic autoimmune disease patients, ROC curve analyses were used to compare the diagnostic performance of the four autoantibodies in differentiating healthy controls (HC) and patients with other connective tissue diseases from SLE patients (Fig. 2). With respect to the differentiation of SLE patients from healthy controls, anti-dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies had a significantly larger AUCs than did anti-C1q and anti-ribosomal P antibodies. The main reason for this phenomenon was that the sensitivity of anti-C1q and anti-ribosomal P antibodies was low, which diminished the detection of SLE. The AUCs of anti-nucleosome and anti-C1q antibodies in differentiating SLE patients from RA patients were relatively decreased. In addition, there was no significant difference in the AUCs for anti-dsDNA and anti-ribosomal P antibodies in differentiating SLE patients from RA patients (Supplementary Table S2). Similarly, there were no significant differences in the AUCs for these antibodies in differentiating SLE patients from HC or OADs (Supplementary Table S4).

However, the ROC-AUCs for the four SLE-associated autoantibodies in differentiating patients with SLE from those with SS were drastically lower than those in differentiating patients with SLE from HC. The specificities and positive predictive values of the four SLE-associated autoantibodies, especially anti‐dsDNA and anti‐nucleosome antibodies, were dramatically decreased (Supplementary Table S3). These findings suggest a strong association between SLE and SS, indicating that these two autoimmune diseases may be closely interconnected. This connection can be explained by the fact that the two diseases are known to share the same immunogenetic background and clinical manifestations13. With respect to genetic factors, some genome-wide association studies have revealed that SLE and SS patients had the same alleles, including those encoding HLA molecules, interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), Ikaros family zinc finger protein 1 and PR domain zinc finger protein 1014. Moreover, similar transcriptional profiles and common gene expression signatures are associated with nucleosome assembly and haemostasis in RA, SLE and SS patients15. In terms of serological features, the two diseases both have the high prevalence of autoantibodies when their serum was viewed on HEp-2 cells by immunofluorescence microscopy16,17. On the other hand, anti-SSA antibodies are present in approximately two-thirds of SS patients, while anti-SSB antibodies are present in nearly half of SS patients18,19. Meanwhile, anti-SSA and anti-SSB autoantibodies, which are common in primary SS patients, are found in 30%–40% and 10%–15% of SLE patients, respectively18,20. Another study confirmed that RA, SLE, and SS patients exhibit megakaryocyte amplification in peripheral blood21,22. Like other connective tissue diseases, SLE and SS have similar clinical features and organic involvements, such as fatigue, arthralgia, and Raynaud’s phenomenon, as well as haematological, nephrological or other organ involvement23. Thus, the numerous biological characteristics and clinical phenotype similarities between SLE patients and SS patients often hamper the distinction of both disorders.

To determine the best cut-off value for differentiating SLE patients from SS patients, we set the specificity to 95% for each autoantibody test, close to that for differentiating SLE patients and HC. Our data show that the cut-off values for anti-dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies need to be nearly doubled, whereas the cut-off values for anti-ribosomal P and anti-C1q antibodies are similar to the manufacturer’s cut-off values. Although the four antibodies are relatively specific indicators of SLE, clinicians still must be cautious in differentiating SLE patients from those with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases. If a patient with SS is positive for SLE-associated autoantibodies, the cut-off value needs to be increased appropriately. The reason for this is that clinicians need a test with good specificity to assess patients in whom SLE or another rheumatic disease is suspected, although the sensitivity will decrease.

On the basis of our findings, SS patients who are positive for SLE-related autoantibodies account for approximately 15% of all SS patients, and a diagnosis of SLE was excluded in these patients. Thus, we evaluated samples and concomitant clinical data from SS patients with or without SLE-associated autoantibodies to determine whether positivity/negativity for these autoantibodies were related to biological characteristics and clinical phenotypes. Consistent with previous studies, more than 70% of SS patients had high ANA titers24,25. Moreover, SS patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies had higher ANA titers than did those without SLE-associated autoantibodies, although the difference was not statistically significant. Interestingly, we observed that anti-nRNP/Sm autoantibodies appeared significantly more frequently in patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies than in SLE-associated autoantibody-negative patients, suggesting that anti-nRNP/Sm autoantibodies may represent a useful serological marker for differentiating the two groups. The differences in the phenotypes of the two groups were subsequently compared. SS patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies demonstrated higher incidence of oral ulcerations and rampant dental manifestations. A higher rate of SLE-associated autoantibody positivity was observed in SS patients with pulmonary involvement than in patients who were negative for SLE-associated autoantibodies. Taken together, these data suggest that the emergence of SLE-associated autoantibodies indicates a severe clinical profile. Thus, in addition to being helpful for diagnosis, these four autoantibodies may serve as prognostic markers. On the other hand, SLE-associated autoantibody positivity may also indicate the possibility of SLE. In recent years, the number of patients with overlap between SS and SLE has gradually increased. The incidence of Sjogren’s syndrome in SLE patients has been reported to be approximately 8.3–19.0%. Unlike patients with a single disease, this population has unique clinical characteristics, such as a decline in renal function, anti-dsDNA positivity, and anti-SM positivity26,27. Multiple studies in which cluster analyses of autoantibodies in patients with SLE were performed have revealed that SLE patients can be divided into multiple subtypes according to differences in genetic background, age of onset, cytokine characteristics, clinical manifestations, disease activity and organ damage characteristics28–30. Previous studies have also identified subgroups of SLE patients characterized by anti-dsDNA antibody positivity, and those SLE patients positive for anti-dsDNA antibodies have a higher possibility of developing nephritis. In contrast, the subgroup of SLE patients characterized by anti-SSA/SSB positivity has many similarities with those with primary Sjogren’s syndrome, in which discoid skin lesions, photosensitivity and leukopenia are more common30,31. Research has indicated that SS and SLE patients share the same or similar genetic backgrounds and clinical phenotypes32,33. Approximately 30% of SLE patients were found to have dry eye symptoms, surprisingly, the degree of ocular involvement was correlated with serum anti-dsDNA antibody levels14. These overlapping features hamper disease diagnosis, prognosis estimations, and personalized treatment. Meanwhile, the association between the two diseases often predicts a more proximate pathogenesis. Further in-depth studies are needed to confirm the mechanisms underlying these associations.

Despite these important findings, the present study has several limitations. Owing to the retrospective nature of the analysis, we were unable to control the sample size for each disease. In addition, test values for autoantibodies, particularly for anti-dsDNA, are known to vary significantly depending on the assay used, thereby causing certain errors in the experimental results. Therefore, a larger cohort is necessary to draw clear conclusions on the basis of the statistical results for some of the investigated disease characteristics. Finally, this study only had a cross-sectional design for four autoantibodies, but longitudinal data tracking will be important in the future.

In summary, SLE-associated autoantibodies are present in patients with other immunological diseases, especially SS patients, and have a major impact on diagnostic efficiency. If a patient with SS is positive for SLE-associated autoantibodies, the cut-off value needs to be increased appropriately. SS patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies have a higher rate of positivity for anti-nRNP/Sm autoantibodies. Oral ulcerations and rampant dental and pulmonary involvement were more common in SS patients with SLE-associated autoantibodies. In conclusion, SLE-associated autoantibody-positive SS patients represent a heterogeneous population, characterized by unique autoantibody profiles and clinical manifestations. This study may provide new insights for diagnostic refinement between SLE and SS patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Jing Yang: Conceptualization; Resources; Software; Formal analysis; Writing - original draft.Lin Zhao: Conceptualization; Investigation; Validation.Shuiqing He: Data curation. XM: Data curation. Liu Yu: Data curation; Methodology; Resources. Xiaodan Kong: Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author would like to thank The Second Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University for their support. This work was supported by 1 + x Program of Youth Medical clinical Technical Ability Improvement project (2024LCJSYL05).

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jing Yang and Lin Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yu Liu, Email: liuyu296545352@163.com.

Xiaodan Kong, Email: xiaodankong2008@sina.com.

References

- 1.Kiriakidou, M. & Ching, C. L. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Intern. Med. 172(11), Itc81-Itc96 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Rahman, A. & Isenberg, D. A. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl. J. Med.358 (9), 929–939 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodsaward, P. et al. The clinical significance of antinuclear antibodies and specific autoantibodies in juvenile and adult systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol.39 (4), 279–286 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leng, Q. et al. Anti-ribosomal P protein antibodies and insomnia correlate with depression and anxiety in patients suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus. Heliyon9 (5), e15463 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shang, X. et al. Anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-C1q, and anti-histone antibodies as markers of active lupus nephritis and systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity. Immun. Inflamm. Dis.9 (2), 407–418 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai, Y. H. et al. Brief report on the relation between complement C3a and anti DsDNA antibody in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci. Rep.12 (1), 7098 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieiro Santos, C., Morales, M. & Castro, C. Polyautoimmunity in systemic lupus erythematosus: secondary Sjogren syndrome. Rheumatologie82(1), 68–73 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saigal, R. et al. Anti-nucleosome antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: potential utility as a diagnostic tool and disease activity marker and its comparison with anti-dsDNA antibody. J. Assoc. Physicians India. 61 (6), 372–377 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Infantino, M. et al. Comparison of current methods for anti-dsDNA antibody detection and reshaping diagnostic strategies. Scand. J. Immunol.96(6), e13220 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghirardello, A. et al. Anti-ribosomal P protein antibodies detected by Immunoblotting in patients with connective tissue diseases: their specificity for SLE and association with IgG anticardiolipin antibodies. Ann. Rheum. Dis.59 (12), 975–981 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallo, C. A. et al. Anti-ribosomal P (anti-P) antibodies in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Einstein (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 21, eAO0375 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kleer, J. S. et al. Epitope-Specific Anti-C1q autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front. Immunol.12, 761395 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldini, C. et al. Sjogren syndrome and other rare and complex connective tissue diseases: an intriguing liaison. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol.40 (5), 103–112 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasoto, S. G., Adriano de Oliveira Martins, V. & Bonfa, E. Sjogren syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus: links and risks. Open access rheumatol. Res. Rev.11, 33–45 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortíz-Fernández, L., Martín, J. & Alarcón-Riquelme, M. E. A summary on the genetics of systemic lupus Erythematosus, rheumatoid Arthritis, systemic Sclerosis, and Sjogren syndrome. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 64 (3), 392–411 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andraos, R. et al. Autoantibodies associated with systemic sclerosis in three autoimmune diseases imprinted by type I interferon gene dysregulation: a comparison across SLE, primary Sjogren syndrome and systemic sclerosis lupus. Sci. Med.9 (1), e000732 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad, A. et al. Autoantibodies associated with primary biliary cholangitis are common among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus even in the absence of elevated liver enzymes. Clin. Exp. Immunol.203 (1), 22–31 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Psianou, K. et al. Clinical and immunological parameters of sjogren’s syndrome. Autoimmun. Rev.17 (10), 1053–1064 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ming, B. et al. How to focus on autoantigen-specific lymphocytes: a review on diagnosis and treatment of sjogren’s syndrome. J. Leukoc. Biol.117 (2), 247 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novak, G. V. et al. Anti-RO/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies: association with mild lupus manifestations in 645 childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun. Rev.16 (2), 132–135 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, Y. et al. Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and primary Sjögren’s syndrome shared megakaryocyte expansion in peripheral blood. Ann. Rheum. Dis.81 (3), 379–385 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonia Szanto, P. S., Kiss, E. & Kapitany, A. Gyula Szegedi & Margit Zeher. Clinical, Serologic, and genetic profiles of patients with associated Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum. Immunol.67, 924–930 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sammaritano, L. R. et al. 2020 American college of rheumatology guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. (Hoboken NJ). 72 (4), 529–556 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broeren, M. G. A. et al. Proteogenomic analysis of the autoreactive B cell repertoire in blood and tissues of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann. Rheum. Dis.81 (5), 644–652 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peene, I., Meheus, L., Veys, E. M. & De Keyser, F. Diagnostic associations in a large and consecutively identified population positive for anti-SSA and/or anti-SSB: the range of associated diseases differs according to the detailed serotype. Ann. Rheum. Dis.61 (12), 1090–1094 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han, Y. et al. Development of clinical decision models for the prediction of systemic lupus erythematosus and sjogren’s syndrome overlap. J. Clin. Med.12 (2), 535 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arbuckle, M. R. et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl. J. Med.349 (16), 1526–1533 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.To, C. H. & Petri, M. Is antibody clustering predictive of clinical subsets and damage in systemic lupus erythematosus? Arthritis Rheum.52 (12), 4003–4010 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Artim-Esen, B. et al. Cluster analysis of autoantibodies in 852 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus from a single center. J. Rheumatol.41 (7), 1304–1310 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diaz-Gallo, L-M. et al. Four systemic lupus erythematosus Subgroups, defined by autoantibodies Status, differ regarding HLA-DRB1 genotype associations and immunological and clinical manifestations. ACR Open. Rheumatol.4 (1), 27–39 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pérez Jiménez, P., Tío Barrera, L., Andréu Sánchez, J. L., Salman-Monte, T. C. & Carrión-Barberà, I. Role of the anti-RO/SSA antibody in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Reumatol Clin. (Engl Ed). 21 (3), 501816 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chau, K. et al. Harley I.T.W. Pervasive sharing of causal genetic risk factors contributes to clinical and molecular overlap between Sjögren’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (19), 14449 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui, Y. et al. Shared and distinct peripheral blood immune cell landscape in MCTD, SLE, and pSS. Cell. Biosci.15, 42 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.