Abstract

Nasutitermes aurantiussp. nov., is described from Central Panama. The soldier is unique among Central American Nasutitermes by its small size and orange head capsule coloration. The enteric valve armature is also unique among congeners. The new species constitutes the seventh Nasutitermes species in the region for which the soldier is described. We provide a key to all Central American Nasutitermes soldiers. Our phylogenetic reconstructions indicate that N. aurantiussp. nov. is more closely related to the Afrotropical Nasutitermes lujae than to any other Neotropical Nasutitermes.

Key words: Biodiversity, enteric valve armature, identification key, mitogenome, nasutitermitine, Neotropics, phylogenetic reconstructions, taxonomy, termites

Introduction

The cosmopolitan termite genus Nasutitermes Dudley, 1890 is the most diverse in the World with about 250 species described (Krishna et al. 2013a). While only eight Nasutitermes species are previously known from Panama through Mexico, sixty-five are currently described from the Neotropics (Rocha et al. 2024; Scheffrahn et al. 2024). One invasive species, N. corniger (Motschulsky, 1855), remains established in southeastern Florida after an attempted eradication program (Scheffrahn et al. 2014). It has also been introduced to Abaco Island, The Bahamas (Scheffrahn et al. 2016). Nasutitermes corniger, no doubt, was transported to non-native localities via maritime movement of infested vessels (Scheffrahn et al. 2005).

Currently, Central America includes N. corniger, N. callimorphus Mathews, 1977, N. ephratae (Holmgren, 1910), N. glabritergus Snyder & Emerson, 1949, N. guayanae (Holmgren, 1910), and N. nigriceps (Haldeman, 1854). The taxonomic history of these species is summarized in Krishna et al. (2013b). Herein, we describe Nasutitermes aurantius sp. nov. from Panama and provide a key to the described Nasutitermes soldiers of Central America.

Material and methods

Photomicrographs were taken as multilayer montages using a Leica M205C stereomicroscope controlled by Leica Application Suite v. 3 software. Preserved specimens were taken from 85% ethanol and suspended in a pool of Purell Hand Sanitizer to position the specimens on a transparent Petri dish background. The worker’s enteric valve armature (EVA) was prepared by removing the entire P2 section in ethanol. Food particles were expelled from the P2 tube by pressure manipulation. The tube was quickly submerged in a droplet of PVA medium (BioQuip Products Inc.), which by further manipulation, eased muscle detachment. The remaining EVA cuticle was longitudinally cut, splayed open, and mounted on a microscope slide using the PVA medium. The EVA preparation was photographed with a Leica CTR 5500 compound microscope using the same montage software. Photographs of other Central American Nasutitermes species were obtained from specimens in the University of Florida Termite Collection (UFTC, Scheffrahn 2019). The distribution map (Fig. 1) was produced using ArcGIS Pro Intelligence 3.0 software (Redlands, Calif.). Measurements were made following the parameters of Roonwal (1970).

Figure 1.

Nasutitermes species of Panama, Central America, and the Neotropical extent of their range.

Sequencing of samples

Here, we report the sequencing of 17 new samples. Mitogenomes were sequenced according to two strategies: (1) The whole mitogenomes were amplified in two long-range PCR reactions using the TaKaRa LA Taq polymerase, primer sets and PCR conditions described in Bourguignon et al. (2016). Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq2000 platform; and (2) Alternately, whole genomes were paired-end sequenced at low coverage with the NovaSeq 6000 Illumina platform at a read length of 150 bp. In both cases, whole genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue extraction kit (Qiagen), and libraries were prepared using the NEBNext® UltraTM II FS DNA Library Preparation Kit (New England Biolabs) and the Unique Dual Indexing Kit (New England Biolabs). The library preparation generally followed the manufacturer’s guidelines, but reagents were reduced to one-fifteenth of recommended volumes, and the enzymatic fragmentation step was set to a maximum of five minutes to avoid over-fragmentation. Libraries were pooled in equimolar concentration.

Raw reads were quality-trimmed using fastp v. 0.20.1 (Chen et al. 2018). Trimmed reads were assembled using metaSPAdes v. 3.13 (Nurk et al. 2017), and mitogenome scaffolds were identified and annotated with MitoFinder v. 1.4 (Allio et al. 2020). Mitogenomes were deposited in GenBank under accessions: PV022512 (BA3003) from Bahamas; PV608493 (BZ186) from Belize; PV078072 (BO352) from Bolivia; PV076159 (MZUSP20115), PV076177 (MZUSP23481), PV078265 (MZUSP25733) from Brazil; PV608494 (EC471), OR684459 (EC1314) from Ecuador; PV656442 (G17-094) from French Guiana; PV656441 (GP17-03) from Guadeloupe; OR607578 (PN183), PV608495 (PN227), OR607546 (PN1315), OR607547 (PN1316) from Panama; OR607564 (PA1206) from Paraguay; and OR607541 (PU257), OR601010 (PU724) from Peru.

Phylogenetic reconstructions

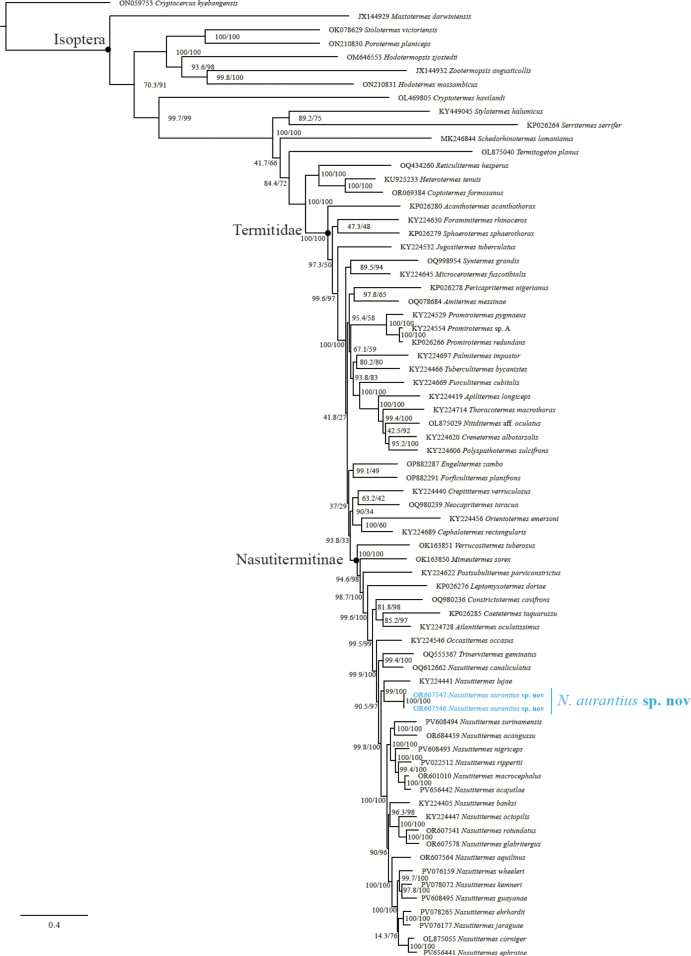

We positioned N. aurantius within a phylogeny reconstructed from the mitogenomes of 69 samples representative of Isoptera and Nasutitermitinae, as evidenced from the near-complete American phylogeny of Hellemans et al. (2025). The 54 samples used to anchor our reconstructions were published elsewhere (Cameron et al. 2012; Bourguignon et al. 2015, 2016, 2017; Wang et al. 2019, 2022, 2023; Hellemans et al. 2022a, b; Arora et al. 2023). The two rRNA and 22 tRNA mitochondrial genes were aligned using MAFFT v. 7.305 (Katoh and Standley 2013). The 13 protein-coding genes were translated into amino acid sequences using the transeq function of EMBOSS v. 6.6.0 (Rice et al. 2000), then aligned with MAFFT and back-translated into codon alignments using PAL2NAL v. 14 (Suyama et al. 2006). Finally, all 37 alignments were concatenated using FASconCAT-G_v. 1.04.pl (Kück and Longo 2014).

The concatenated sequence alignment was partitioned into 41 partitions: one partition with the combined rRNAs; one with the tRNAs; and each of the 13 protein-coding genes was separated into three partitions (i.e., one for each of the three codon positions). The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed with IQ-TREE v. 2.2.2.5 (Minh et al. 2020). The partitions were merged, and the top 10% were investigated using the options “-m MFP+MERGE -rcluster-max 2000 -rcluster 10” (Chernomor et al. 2016). The best-fit nucleotide substitution model was selected with the Bayesian Information Criterion using ModelFinder implemented in IQ-TREE (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. 2017). Branch supports were assessed with 1000 bootstrap replicates, both with the ultrafast algorithm (UFB) (Hoang et al. 2018) and the Shimodaira–Hasegawa approximate likelihood-ratio (SH-aLRT) test (Guindon et al. 2010).

Taxonomy

. Nasutitermes aurantius

Scheffrahn sp. nov.

225650E4-D45B-59A6-B79F-E26B483F0DF4

https://zoobank.org/5D3B658F-57EC-4EC3-BEF4-C3EBB5128D25

Diagnosis.

The soldier of N. aurantius sp. nov. is unique among Central American Nasutitermes spp. by its small size and orange head capsule coloration. Among South American Nasutitermes, the N. aurantius soldier is closest in size and coloration to Nasutitermes jaraguae (Holmgren, 1910), but the former has a proportionally longer and thinner nasus. The worker EVA of N. aurantius is unique among Neotropical Nasutitermes spp. in that the distal cushion sections are sclerotized, ovoid, granulated, and spiny. The imago of N. aurantius is the smallest among Central American Nasutitermes spp. as measured by head width.

Description.

Imago (Fig. 2A). Female unknown. Head capsule dark brown at vertex, gena lighter; clothed in dense setae of varying length. Fontanelle a narrow slit. Eyes nearly circular; projecting nearly half their diameter. Ocellus hyaline; more than one diameter from eye margin. Pronotum concolorous with head capsule; anterior margin straight, posterior margin slightly incised; setation as with head capsule. Antennae with 15 articles, formula 2>3<4=5, third article narrowest. Measurements (mm, N = 2, males): Head length to tip of labrum 1.23,1.28; head maximum width with eyes 1.21, 1.25; eye maximum diameter 0.31, 0.35; ocellus maximum diameter 0.10, 0.11; pronotum maximum length 0.56, 0.59; pronotum maximum width 0.94, 95; right forewing length from suture 9.37, 9.94; total length with wings 11.36, 11.64.

Figure 2.

Alate of Nasutitermes aurantius sp. nov. (PN1317, male). A. Dorsal habitus; B. Dorsal view of head capsule and pronotum; C. Lateral view of head capsule and pronotum.

Soldier (Figs 3, 8B). Monomorphic. Head capsule orange with brown tinge, nasus darker. Head capsule subtriangulate in dorsal view; sides converging rather steeply toward nasus; slight constriction behind antennal sockets. Lateral view of head capsule with slight convexity above and behind antennal sockets. Vertex with four long setae near summit of convexity and two long setae near posterior third of vertex. Nasus narrowly conical with conspicuous setae at tip; nasus nearly parallel with lower margin of gena. Antennae with 13 articles, formula 2<3>4<5. Mandibles with prominent points. Pronotum with shallow lobes angled 120°; margin of dorsal lobe with a few long and numerous very short setae. Tergites with several long setae on posterior margins and many short setae in interior. Postmentum occupies nearly one-fourth of total head height with shallow convexity in lateral view opposite of vertex concavity. Measurements (mm, N = 10, X̄, range): Head length1.53 (1.46–1.58); head length to base of nasus 0.91 (0.86–0.94); nasus length 0.62 (0.57–0.67); maximum head width 0.84 (0.77–0.89); pronotum width 0.44 (0.40–0.49); hind tibia length 0.86 (0.86–0.91).

Figure 3.

Soldier of Nasutitermes aurantius sp. nov. (PN1315). A. Dorsal view of head and pronotum; B. Lateral view; C. Ventral view; D. Lateral habitus.

Figure 8.

Field habitus of Nasutitermes aurantius sp. nov. A. Alate (PN1317); B. Foragers (PN1315; note microsporidial infection in abdomen of worker at bottom right).

Worker (Figs 4, 5, 6, 8B). Dimorphic. Head capsule light yellowish or light orangish; clothed with about 80 setae of varying lengths. Vertex with concavity behind postclypeus; postclypeus small, with steep posterior margin in lateral view. Fontanelle hyaline, large, ovoid; brain conspicuously white with incision carved out by fontanelle. Antennae with 14 and 13 articles for major and minor morph, respectively; antennal article formula 2>3<4=5 for both. Mandible dentition (wood feeding type) and gap between third marginal tooth and molar prominence similar for both morphs; left mandible with straight cutting edge; molar plate with ridges. Mesenteron well developed forming a complete ring from crop to P1; P1 long, tubular in dorsal and ventral views; forming an “S” from M to EVA seating visible through cuticle. Enteric valve armature composed of three cushions, each with anterior section consisting of about 80 to 100 rounded scales each with minute points facing posteriorly. Posterior sections of EVA sclerotized and ovoid; each formed with about 10–12 polygons; central 4–5 polygons granulated and each adorned with a spine; a few scattered scales between and anterior to cushions. Head width measurements (mm, N = 10 for each morph): major worker 1.04 X̄ (range 99–1.04); minor worker X̄ 0.87 (range 0.84–0.91).

Figure 4.

Worker of Nasutitermes aurantius sp. nov. (PN1315). A. Dorsal view of major worker; B. Dorsal view of minor worker; C. Ventral view of major worker.

Figure 5.

Worker of Nasutitermes aurantius sp. nov. (PN1315). A. Dorsal view of major worker head capsule; B. Lateral view of same; C. Major worker mandibles (3M = third marginal tooth, MP = molar prominence); D. Minor worker mandibles.

Figure 6.

Enteric valve armature of the major worker of Nasutitermes aurantius sp. nov. (PN1315). Inset shows a close-up of the posterior cushion.

Type material.

Holotype: Panama • Soldier; Coclé, Omar Torrijos Herrera National Park (El Cope); 8.66969°, -80.59302°; 791 m a.s.l.; 4 June 2010; R. Scheffrahn leg.; many soldiers (one labeled holotype) and workers; University of Florida Termite Collection (UFTC) no. PN1315. Paratypes: Same data as holotype; two subsamples from separate colony; two male alates, many soldiers and workers, five nymphs (PN1317); many soldiers and workers, two nymphs (PN1316).

Etymology.

The specific name “aurantius” is from Latin “aurantium” meaning “orange”, referring to the soldier’s head capsule coloration.

Ecological note.

Nasutitermes aurantius sp. nov. foragers and two alates were collected underneath saturated decaying wood (Fig. 8). No above-ground nest structure was observed, so it is assumed that the nest is subterranean. The presence of developed alates suggests that the flight season is in early June. The type locality is classified as tropical rainforest (Köppen-Geiger) with an annual precipitation of > 250 cm.

Taxonomic note.

Light (1933) described two additional Central American Nasutitermes species from the imago caste: N. pictus and N. colimae. Both were collected simultaneously during a single dispersal flight by M. Ceballos from an “old orange tree” in Colima, Mexico. No foragers were collected. Their large size (head width 1.65 and 1.95, respectively) suggests that these two species are not Nasutitermes but either a Cahuallitermes spp. (imago unknown), a Tenuirostritermes spp., or an undescribed apicotermitine. Therefore, we consider N. pictus Light, 1933 and N. colimae Light, 1933 to be nomina dubia.

Key to Central American Nasutitermes soldiers

| 1 | Head capsule yellowish or orangish (Figs 3, 7I) | 2 |

| — | Head capsule brown to almost black (Fig. 7A–D, H) | 3 |

| 2 | Head capsule orangish, triangulate in dorsal view (Fig. 3) | N. aurantius sp. nov. |

| — | Head capsule yellowish, ovoid in dorsal view (Fig. 7I) | N. glabritergus |

| 3 | Head capsule in lateral view with four setae behind nasus and two setae near base (Fig. 7A, C, H) | 4 |

| — | Head capsule in lateral view with ten or more setae on dorsum (Fig. 7B, D). Nests are often very large | 6 |

| 4 | Pronotum in lateral view with no long setae on dorsal lobe, head width 0.72–0.83 mm (Fig. 7A) | N. callimorphus |

| — | Pronotum in lateral view with numerous long setae on dorsal lobe (Fig. 7E), head width variable, > 0.9 mm (Fig. 7C, H) | 5 |

| 5 | Tergite surfaces covered with barely visible microscopic setae (Fig. 7F). Alate wings golden brown; arboreal nest with smooth outer skin reminiscent of an orange peel when removed | N. ephratae |

| — | Tergite surfaces covered with clearly visible microscopic setae (Fig. 7G). Alate wings black; arboreal nest with uneven friable surface | N. corniger |

| 6 | Head capsule clothed with about 100 medium and long setae; setae abundant on nota (Fig. 7B) | N. nigriceps |

| — | Head capsule covered with about 30 mostly long setae; setae very sparse on nota (Fig. 7D) | N. guayanae |

Figure 7.

Dorsal and lateral views of soldier head capsules of Panamanian Nasutitermes to scale. A. N. callimorphus; B. N. nigriceps; C. N. ephratae; D. N. guayanae; E. Lateral view of the N. ephratae pronotum; F. Tergites of N. corniger; G. Tergites of N. ephratae; H. N.corniger; I. N. glabritergus.

Results and discussion

Our phylogenetic analyses revealed that the Panamanian N. aurantius sp. nov. is more closely related to the Afrotropical N. lujae (90.61% identity) than to any other Neotropical Nasutitermes included herein (Fig. 9, Table 1). The sequence of N. lujae (KY224441) was previously published by Bourguignon et al. (2017). The taxa chosen herein for the phylogenetic tree was subset from the megaphylogeny of Hellemans et al. (2025). This paper notably included more Operational Taxonomic Units than the number of species currently described from the Neotropics. Therefore, data handling error is highly unlikely given that no other neotropical “N. lujae” clustered to KY224441 in the megaphylogeny by Hellemans et al (2025).

Figure 9.

A phylogenetic tree of N. aurantius and other related taxa inferred from the mitogenomes. Branch supports values are the Shimodaira–Hasegawa approximate likelihood-ratio and ultrafast bootstrap (SH-aLRT/UFB).

Table 1.

Pairwise mitogenome similarities between species of Nasutitermes closely related to N. aurantius. Similarities were obtained with megaBLASTn.

| SAMPLE | BA3003 | BO352 | BZ186 | EC1314 | EC471 | G13-117 | G17-094 | G718 | GP17-03 | MZUSP-20115 | MZUSP-23481 | MZUSP-25733 | NI275 | PA1206 | PN1315 | PN1316 | PN183 | PN227 | PU257 | PU724 | RDCT106 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA3003 Nasutitermes rippertii | 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| BO352 Nasutitermes kemneri | 90.345 | 100 | |||||||||||||||||||

| BZ186 Nasutitermes nigriceps | 92.768 | 90.639 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||||

| EC1314 Nasutitermes acangussu | 90.513 | 89.7 | 90.043 | 100 | |||||||||||||||||

| EC471 Nasutitermes surinamensis | 90.818 | 89.761 | 90.233 | 90.56 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| G13 117 Nasutitermes banksi | 91.025 | 91.261 | 90.318 | 89.908 | 90.372 | 100 | |||||||||||||||

| G17 094 Nasutitermes acajutlae | 92.86 | 90.525 | 93.134 | 90.383 | 90.942 | 91.204 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| G718 Nasutitermes octopilis | 90.93 | 90.486 | 89.494 | 90.605 | 89.813 | 90.98 | 90.902 | 100 | |||||||||||||

| GP17 03 Nasutitermes ephratae | 90.112 | 92.128 | 89.842 | 89.544 | 89.646 | 90.796 | 90.567 | 90.645 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| MZUSP20115 Nasutitermes wheeleri | 90.419 | 92.766 | 90.31 | 89.835 | 89.777 | 90.811 | 90.744 | 90.19 | 91.928 | 100 | |||||||||||

| MZUSP23481 Nasutitermes jaraguae | 90.548 | 92.896 | 90.44 | 90.095 | 89.884 | 91.116 | 90.612 | 90.636 | 92.491 | 92.813 | 100 | ||||||||||

| MZUSP25733 Nasutitermes ehrhardti | 90.481 | 92.983 | 90.101 | 89.68 | 89.771 | 91.07 | 90.642 | 90.588 | 92.376 | 92.687 | 95.164 | 100 | |||||||||

| NI275 Nasutitermes corniger | 90.632 | 92.652 | 90.132 | 89.845 | 89.834 | 91.225 | 91.168 | 90.104 | 95.419 | 92.477 | 93.008 | 92.887 | 100 | ||||||||

| PA1206 Nasutitermes aquilinus | 90.667 | 91.647 | 91.327 | 90.048 | 90.744 | 91.124 | 90.905 | 90.06 | 91.191 | 91.064 | 91.186 | 91.341 | 91.024 | 100 | |||||||

| PN1315 Nasutitermes aurantiussp. nov. | 90.347 | 89.886 | 89.927 | 89.441 | 89.78 | 90.4 | 89.986 | 90.269 | 89.465 | 89.771 | 89.993 | 89.964 | 89.977 | 89.954 | 100 | ||||||

| PN1316 Nasutitermes aurantiussp. nov. | 90.427 | 89.965 | 89.916 | 89.515 | 89.912 | 90.473 | 90.087 | 90.416 | 89.536 | 89.848 | 90.066 | 90.042 | 90.051 | 90.125 | 99.908 | 100 | |||||

| PN183 Nasutitermes glabritergus | 89.759 | 89.763 | 89.517 | 89.234 | 89.676 | 90.213 | 90.245 | 91.575 | 89.243 | 89.82 | 89.715 | 90.044 | 89.849 | 89.967 | 89.33 | 89.402 | 100 | ||||

| PN227 Nasutitermes guayanae | 91.266 | 93.732 | 91.686 | 90.312 | 90.303 | 91.786 | 91.373 | 90.849 | 92.738 | 93.258 | 92.839 | 93.19 | 92.899 | 91.104 | 89.623 | 89.775 | 90.266 | 100 | |||

| PU257 Nasutitermes rotundatus | 90.138 | 90.149 | 89.898 | 89.45 | 89.757 | 90.349 | 90.152 | 92.173 | 89.823 | 90.102 | 90.247 | 90.354 | 89.983 | 90.034 | 89.901 | 89.991 | 93.479 | 90.909 | 100 | ||

| PU724 Nasutitermes macrocephalus | 93.278 | 90.84 | 92.84 | 90.493 | 90.983 | 91.236 | 96.45 | 91.167 | 90.344 | 90.602 | 90.941 | 90.961 | 91.055 | 91.075 | 89.992 | 90.071 | 90.075 | 91.453 | 90.262 | 100 | |

| RDCT106 Nasutitermes lujae | 89.636 | 89.574 | 89.63 | 89.098 | 89.631 | 89.921 | 89.672 | 90.056 | 89.475 | 89.38 | 89.671 | 89.627 | 89.674 | 90.02 | 90.539 | 90.612 | 89.18 | 90.251 | 89.3 | 89.841 | 100 |

Our sampling includes representatives from all closely-related lineages of Nasutitermes according to the megaphylogeny of Hellemans et al. (2025). Furthermore, it is our “signature” to provide phylogenetic relationships within a more global framework to help non-specialists to quickly position the focal taxa in the global termite tree of life (Hellemans et al. 2022b).

The Neotropical species of the genus Nasutitermes are in dire need of revision. The synonymy of Nasutitermes dasyopsis Thorne, 1989 into Nasutitermes nigriceps (Haldeman, 1854) by Scheffrahn et al. (2024) leaves sixty-five valid Nasutitermes species in the Neotropics (Constantino 2020). Of these, thirty species may be on the precipice of taxonomic correction by scoring 4 or less out of a possible 10 on the confidence scale of Rocha et al. (2024). A low confidence score can result from lost types, descriptions of a single caste, or descriptions that are generic only, lacking detailed illustrations, biology, distribution, or genetic sequencing (Rocha et al. 2024). These species with the lowest confidence (≤ 4), originally described between 1839–1933, were plagued by poor descriptions, nomina dubia, or synonyms. Another twenty species with an intermediate confidence score (5–6) also suffered, but to a lesser extent, from mediocre descriptions, leaving only fifteen species in the upper range of confidence (≥7) (Rocha et al. 2024; Scheffrahn et al. 2024). Add to those Nasutitermes species that may be undescribed (UFTC database in Scheffrahn 2019), and the revised tally of Neotropical Nasutitermes may become profoundly amended. The recent global phylogeny of Hellemans et al. (2025) provides a good start for a systematic revision of Neotropical Nasutitermes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Scientific Computing & Data Analysis Section (SCDA) for providing access to the OIST computing cluster. This work was supported by subsidiary funding from OIST to TB. EMC thanks the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for the grant (Proc. 311067/2023-9. EMC thanks the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for the grant (Proc. 311067/2023-9).

Citation

Scheffrahn RH, Wang M, Bourguignon T, Rocha MM, Cancello EM, Roisin Y, Hellemans S (2025) Nasutitermes aurantius (Isoptera, Termitidae, Nasutitermitinae), a new nasutiform termite species from Panama and a key to soldiers of Central American Nasutitermes Dudley, 1890. ZooKeys 1256: 163–177. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1256.158192

Funding Statement

1Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Ethical statement

No ethical statement was reported.

Use of AI

No use of AI was reported.

Funding

This study was supported by a travel grant from Terminix International L.P.

Author contributions

Scheffrahn wrote the first draft, with inputs from SH. Specimen collection and curation: MMR, EMC, YR, SH. Genetic sequencing and analysis: MW, TB, SH. All authors reviewed the final draft.

Author ORCIDs

Rudolf H. Scheffrahn https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6191-5963

Menglin Wang https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2206-9503

Thomas Bourguignon https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4035-8977

Mauricio M. Rocha https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6568-068X

Eliana M. Cancello https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3125-6335

Yves Roisin https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6635-3552

Simon Hellemans https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1266-9134

Data availability

All of the data that support the findings of this study are available in the main text.

References

- Allio R, Schomaker-Bastos A, Romiguier J, Prosdocimi F, Nabholz B, Delsuc F. (2020) MitoFinder: Efficient automated large-scale extraction of mitogenomic data in target enrichment phylogenomics. Molecular Ecology Resources 20(4): 892–905. 10.1111/1755-0998.13160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora J, Buček A, Hellemans S, Beránková T, Romero Arias J, Fisher BL, Clitheroe C, Brune A, Kinjo Y, Šobotník J, Bourguignon T. (2023) Evidence of cospeciation between termites and their gut bacteria on a geological time scale. Proceedings. Biological Sciences 290(2001): 20230619. 10.1098/rspb.2023.0619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon T, Lo N, Cameron SL, Šobotník J, Hayashi Y, Shigenobu S, Watanabe D, Roisin Y, Miura T, Evans TA. (2015) The evolutionary history of termites as inferred from 66 mitochondrial genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32(2): 406–421. 10.1093/molbev/msu308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon T, Lo N, Šobotník J, Sillam-Dussès D, Roisin Y, Evans TA. (2016) Oceanic dispersal, vicariance and human introduction shaped the modern distribution of the termites Reticulitermes, Heterotermes, and Coptotermes. Proceedings. Biological Sciences 283(1827): 20160179. 10.1098/rspb.2016.0179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon T, Lo N, Šobotník J, Ho SYW, Iqbal N, Coissac É, Lee M, Jendryka MM, Sillam-Dussès D, Křížková B, Roisin Y, Evans TA. (2017) Mitochondrial phylogenomics resolves the global spread of higher termites ecosystem engineers of the tropics. Molecular Biology and Evolution 34: 589–597. 10.1093/molbev/msw253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SL, Lo N, Bourguignon T, Svenson GJ, Evans TA. (2012) A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of termites (Blattodea: Termitoidae): robust support for interfamilial relationships and molecular synapomorphies define major clades. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 65(1): 163–173. 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. (2018) Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34(17): i884–i890. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chernomor O, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. (2016) Terrace aware data structure for phylogenomic inference from supermatrices. Systematic Biology 65(6): 997–1008. 10.1093/sysbio/syw037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino R. (2020) Termite Database. Brasília, University of Brasília. http://termitologia.net [Accessed 9 April 2025]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic Biology 59(3): 307–321. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans S, Šobotník J, Lepoint G, Mihaljevič M, Roisin Y, Bourguignon T. (2022a) Termite dispersal is influenced by their diet. Proceedings. Biological Sciences 289(1975): 20220246. 10.1098/rspb.2022.0246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans S, Wang M, Hasegawa N, Šobotník J, Scheffrahn RH, Bourguignon T. (2022b) Using ultraconserved elements to reconstruct the termite tree of life. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 173: 107520. 10.1016/j.ympev.2022.107520 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hellemans S, Wang M, Jouault C, Rocha MM, Battilana J, Carrijo TF, Legendre F, Condamine FL, Roisin Y, Cancello EM, Scheffrahn RH, Bourguignon T. (2025) Termites became the dominant decomposers of the tropics after two diversification pulses. bioRxiv, 1–46 [2025.03.25.645184]. 10.1101/2025.03.25.645184 [DOI]

- Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. (2018) UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35(2): 518–522. 10.1093/molbev/msx281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, Von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. (2017) ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature Methods 14(6): 587–589. 10.1038/nmeth.4285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30(4): 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna K, Grimaldi DA, Krishna V, Engel MS. (2013a) Treatise on the Isoptera of the world: Volume 1 Introduction. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 377(7): 1–200. 10.1206/377.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna K, Grimaldi DA, Krishna V, Engel MS. (2013b) Treatise on the Isoptera of the world: Volume 5 Termitidae (Part Two). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 377(7): 1499–1987. 10.1206/377.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kück P, Longo GC. (2014) FASconCAT-G: Extensive functions for multiple sequence alignment preparations concerning phylogenetic studies. Frontiers in Zoology 11(1): 81. 10.1186/s12983-014-0081-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light SF. (1933) Termites of western Mexico. University of California Publications in Entomology 6: 79–164. [Google Scholar]

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, Von Haeseler A, Lanfear R, Teeling E. (2020) IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Molecular Biology and Evolution 37(5): 1530–1534. 10.1093/molbev/msaa015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickle DA, Collins MS. (1990) The termite fauna (Isoptera) in the vicinity of Chamela, State of Jalisco, Mexico. Folia Entomologica Mexicana 77: 85–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nurk S, Meleshko D, Korobeynikov A, Pevzner PA. (2017) metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Research 27(5): 824–834. 10.1101/gr.213959.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P, Longden L, Bleasby A. (2000) EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends in Genetics 16(6): 276–277. 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha MM, Lima KS, Cancello EM. (2024) A protocol to evaluate the taxonomic health of Neotropical species of Nasutitermes (Termitidae, Nasutitermitinae). ZooKeys 1210: 143–172. 10.3897/zookeys.1210.116666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roonwal ML. (1970) Measurements of termites (Isoptera) for taxonomic purposes. Journal of the Zoological Society of India 21: 9–66. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffrahn RH. (2019) UF termite database. University of Florida termite collection. https://www.termitediversity.org/ [Accessed 9 April 2025]

- Scheffrahn RH, Křeček J, Szalanski AL, Austin JW, Roisin Y. (2005) Synonymy of two arboreal termites (Isoptera: Termitidae: Nasutitermitinae): Nasutitermes corniger from the Neotropics and N. polygynus from New Guinea. The Florida Entomologist 88(1): 28–33. 10.1653/0015-4040(2005)088[0028:SOTATI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI]

- Scheffrahn RH, Hochmair HH, Kern Jr WH, Warner J, Křeček J, Maharajh B, Cabrera BJ, Hickman RB. (2014) Targeted elimination of the exotic termite, Nasutitermes corniger (Isoptera: Termitidae: Nasutitermitinae), from infested tracts in southeastern Florida. International Journal of Pest Management 60(1): 9–21. 10.1080/09670874.2014.882528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffrahn RH, Austin JW, Chase JA, Gillenwaters B, Mangold JR, Szalanski AL. (2016) Establishment of Nasutitermes corniger (Isoptera: Termitidae: Nasutitermitinae) on Abaco Island, The Bahamas. The Florida Entomologist 99(3): 544–546. 10.1653/024.099.0331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffrahn RH, Roisin Y, Szalanski AL, Austin JW, Duquesne E. (2024) Expanded range of Nasutitermes callimorphus Mathews, 1977 (Isoptera: Termitidae: Nasutitermitinae), comparison with N. corniger (Motschulsky, 1855) and N. ephratae (Holmgren, 1910), and synonymy of N. dasyopsis Thorne, 1989 into N. nigriceps (Haldeman, 1854). Zootaxa 5507(1): 57–78. 10.11646/zootaxa.5507.1.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P. (2006) PAL2NAL: Robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Research 34(Web Server): W609–W612. 10.1093/nar/gkl315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang M, Buček A, Šobotník J, Sillam-Dussès D, Evans TA, Roisin Y, Lo N, Bourguignon T. (2019) Historical biogeography of the termite clade Rhinotermitinae (Blattodea: Isoptera). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 132: 100–104. 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All of the data that support the findings of this study are available in the main text.