Abstract

Grapes are globally cultivated yet flavor characterization of table cultivars is relatively limited. The present study comprehensively evaluated the physico-chemical indices, the primary metabolites, and the volatile aroma compounds of seven popular table grape cultivars in China over two consecutive years during 2022 and 2023. ‘Huangjinmi’ showed the largest berries in 2022; ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ were the smallest and sweetest in 2023. 61 volatile compounds were identified in these grape berries, with the terpenes and C6 compounds being the most abundant in most cultivars. ‘Ruidu Kemei’ and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ exhibited higher levels of terpenes, while ‘Huangjinmi’, ‘Rubin Muscat’, and ‘Klimbamak’ were dominated by C6 compounds. Sensory analysis revealed that ‘Huangjinmi’ and ‘Ruidu Kemei’ were preferred for their balanced sweet-sour profile and crisp texture, while ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ were notable for their high sweetness and strong aroma. Results guide market-oriented selection of table grapes in China and across East Asia.

Keywords: table grapes, physico-chemical properties, volatile compounds, sensory evaluation, aroma profiles

Highlights

-

•

Two-year profiling of volatiles decoded flavor of seven white table grapes.

-

•

HS-SPME-GC–MS quantified 61 volatiles; OAV-driven aroma wheels created.

-

•

Four Muscat-types (terpene-rich) vs three Neutral-types (C6-dominant) defined.

-

•

Consumer-liked profiles: balanced sweet/acid plus crisp or intense floral softness.

-

•

Ready-to-use aroma fingerprints for breeders and market segmentation.

1. Introduction

Grape (Vitis spp.) is a fruit of significant economic importance. Table grapes refer to grapes that are mainly used for direct consumption, as opposed to those used for winemaking, raisins and jam making or even other processing purposes. According to the 2023 statistics from the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), China's grape cultivation area was approximately 756,000 ha, accounting for 11 % of the global grape planting area (International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV), 2023. China was the world's largest producer of table grapes, with a production volume of about 13.5 million tons in 2023, representing 42 % of the global table grape output (OIV, 2023).

In the evaluation of table grape quality, a comprehensive consideration of various relevant quality indicators was essential. However, the most fundamental sensory attributes, including the appearance, flavor and aroma of the grape berries, were given the highest priority. The appearance quality of grapes was primarily characterized by the fruit color, size, and shape. The sweetness and sourness of grape berries were primarily imparted by soluble sugars and organic acids, respectively. The unique flavor of grapes was not merely a result of sweetness and acidity, while the flavor profile of table grapes was also significantly influenced by secondary metabolites, among which volatile aroma compounds played a crucial role. The aroma compounds in grape berries mainly existed in the free and bound forms, especially the glycosylated forms. Free aroma compounds were volatile, which could be smelled directly, while the bound compounds existed as the odorless precursors (Ferreira & Lopez, 2019). These compounds needed to be hydrolyzed by acid, heat, enzymes, or ultrasonic methods to release the aglycones, which then produced aromas (Martínez et al., 2025; Y. Sun et al., 2021). Therefore, for the table grapes, more attention should be paid to the free aroma compounds. To date, presently, over 500 volatile aroma compounds have been identified in different grape cultivars, including terpenes, C6 compounds, esters, norisoprenoids, alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones (H.-C. Lu et al., 2022). The differences in the types and concentrations of volatile aroma compounds among various grape cultivars, as well as their sensory thresholds and the interactions among them, such as synergistic, additive, and masking effects, determined the aroma sensory quality of grapes (Canturk et al., 2025; Tempere et al., 2012).

This study focused on seven novel and unique white table grape cultivars in China or even the parts of East Asia. ‘Huangjinmi’ was bred by the Institute of Changli Fruit Research, Hebei Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences. This cultivar had the characteristics of easy flower formation, early maturity, natural fruiting, disease resistance, high yield, large berries, thin skin, yellow-green skin color, crispy flesh, and resistance to storage and transportation. ‘Ruidu Kemei’ was a premium, medium-ripening, rose-scented cultivar originating from Hungary which was an important facility cultivar that performed remarkably well in double-cropping cultivation within the Beijing area. ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ was characterized by its loose clusters, yellow-green fruit skin, firm and crisp flesh, rose fragrance, sweet and fragrant taste, and early maturity with high yield. Based on the available research, information regarding the cultivar characteristics and cultivation techniques of ‘Rubin Muscat’ was relatively limited. ‘Bixiang Wuhe (Bixiang Seedless)’ was an extremely early-maturing, strong rose aroma, high-quality seedless grape cultivar, which was bred by Jilin Agricultural Science and Technology University. ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ exhibited early maturity, strong productivity, moderate disease resistance, high adaptability, high total soluble solids content, and a rose-like aroma. Currently, ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ were introduced and cultivated in multiple regions of China. ‘Klimbamak’ originated in Uzbekistan, and it was characterized by its unique fruit shape, with berries in a long oval form and high uniformity in berry size.

From the present reports of these table grape cultivars, various table cultivars showed different properties. However, the cultivation of table grapes in China was characterized by limited cultivar diversity, with a few dominant cultivars such as ‘Kyoho’, ‘Red Globe’, ‘Summer Black’, and ‘Sunshine Muscat’ accounting for the majority of plantings. This limited diversity led to a significant product homogenization, reducing the market competitiveness. The increasing consumer demand for diverse grape cultivars which could not be met by a limited range of cultivars. Considering the global climate change, grape cultivation confronted numerous challenges, including the rising temperatures and the altered precipitation patterns, which had significantly impacted the growth cycle, quality, and yield of the grapes (Khadatkar et al., 2025). The monoculture of a few cultivars weakened the industry's resilience to risks. Therefore, the promotion of diverse cultivars held significant importance.

The present research on the compounds those related to the sensory profiles predominantly were focused on the table grapes, comprehensively and in-depth. In this study, seven cultivars of white table grapes were selected to compare their basic physico-chemical indicators, primary metabolites, and volatile aroma compounds, as well as their sensory analysis. This approach clarified the flavor characteristics of these white table grape cultivars and it was crucial for the further understanding of the quality differences among them, providing a basis for the grape cultivars introduction and the implantation of these popular grapes around the capital of China, Beijing.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Field conditions and plant materials

The study was conducted in the years of 2022 and 2023 at the Zhuozhou Teaching and Experimental Farm of China Agricultural University. The farm is located in Zhuozhou City, Hebei Province (39°46′N, 115°54′E, elevation 40 m), which had a temperate continental monsoon climate, with distinct seasons and pronounced continental characteristics. This study chose seven white table grape cultivars, which grafted onto ‘5BB’ rootstock (Table 1). The rootstocks were planted in the spring of 2018, and the scions of the seven cultivars were grafted by greenwood grafting in the early summer of 2019. In 2023, the climatic conditions for grape growth in the the multi-span greenhouse and glass greenhouse were essentially the same (Supplementary Table 1). The vines were planted in a 4 × 3 m layout with a trellis system at southwest-northeast orientation. The study employed drip irrigation, with pest and disease control and fertilizer application determined according to local standards, while other treatments followed the conventional field management practices.

Table 1.

Information of the seven white table grape cultivars in this study.

| Cultivars | Year of Cultivar Approval | Parental Origins | Species | Seed Presence | Cultivation Facilities | Harvest Date |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | ||||||

| ‘Huangjinmi’ | 2020 | ‘Red Globe’ × ‘Xiangfei’ | V. vinifera L. | seedless | multi-span greenhouse | 08/31 | 09/07 |

| ‘Ruidu Kemei’ | 2016 | ‘Italia’ × ‘Muscat Louis' | V. vinifera L. | seeded | multi-span greenhouse | 08/27 | 08/31 |

| ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ | 2007 | ‘Jingxiu’ × ‘Xiangfei’ | V.vinifera L. | seeded | multi-span greenhouse | 08/16 | 08/17 |

| ‘Rubin Muscat’ | – | – | V. vinifera L. | seeded | multi-span greenhouse | 09/01 | 09/21 |

| ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ | 2004 | ‘1851’ ×’Sabar Pearl’ | V. vinifera L. | seedless | glass greenhouse | 08/07 | 08/17 |

| ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ | 2011 | ‘Guibao’ ×’Wuhe Baijixin’ | V. vinifera L. | remnant seeds | multi-span greenhouse | 08/25 | 08/31 |

| ‘Klimbamak’ | – | – | V. vinifera L. | seeded | multi-span greenhouse | 08/27 | 08/31 |

During the two weeks prior to maturity, total soluble solid was measured daily. Harvesting was conducted when the total soluble solid (TSS) reached and stabilized above 18°Brix. If they did not reach the hoped 18°Brix, harvesting was performed once the total soluble solid stabilized. Specific sampling dates were shown in Table 1. Ten vines with similar growth and normal development were selected as one biological replicate, and each cultivar had three biological replicates. Within each biological replicate, 300 berries without obvious physical damage or pest and disease infestation were randomly selected from the upper, middle, and lower parts. Sampling was conducted around 9 a.m., and the berries were promptly transported to the laboratory in insulated foam boxes with cooling packs. Of these, 100 berries were used for physico-chemical analysis, while the remaining 200 berries were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for other analyses.

2.2. Physico-chemical analysis of the grape berries

One hundred berries were randomly selected from each biological replicate. The stalks were removed, and the weight of the 100 berries was measured using a FA2004 electronic balance (Sunyoon Hengping, Shanghai, China). The width and length of the berries were measured using a 111-101 V-10G electronic digital caliper (Guanglu, Guilin, China). The shape index was the berry length-to-berry width ratio. Sixty berries were crushed to obtain the juice, which was used to measure pH, total soluble solid, and titratable acidity (TA). The TSS was measured by using a PAL-1 digital handheld refractometer (Atago, Tokyo, Japan). The pH value was measured by using a PB-10 pH meter (Sartorius, Gottingen, Germany). TA was measured and expressed as tartaric acid equivalents according to the National Standard of People's Republic of China (GB/T 15038–2006).

2.3. Sugars and organic acids assays of the grape berries

Fifty grape berries were randomly selected from each biological replicate and squeezed to obtain juice, which was centrifuged at 20 °C and 8000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was filtered through 0.22 μm microporous membrane and analyzed for sugars (glucose and fructose) and organic acids (tartaric acid, malic acid, and citric acid) on an Agilent 1200 series HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). An HPX-87H Aminex ion-exchange column (300 × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was employed, with a mobile phase of 5 mmol/L sulfuric acid solution at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 60 °C, and the injection volume was 20 μL. Sugars were detected by using an Agilent G1362A refractive index detector and organic acids were detected by using an Agilent G1315D diode array detector. Qualitative analysis was conducted by comparing the retention times of the compounds with those of the reference standards. Quantitative analysis was performed by constructing a calibration curve using the reference standards.

2.4. Volatile compounds assay of the grape berries

Approximately 60 g of grape berries were taken, removed from the stalks, and weighed. The berries were crushed in liquid nitrogen, during which 0.5 g of D-gluconic acid lactone and 1.0 g of polyvinylpolypyrrolidone were added. The seeds were removed after crushing, and the pulp was weighed. The crushed pulp was further ground thoroughly using a grinder, with liquid nitrogen added to maintain a low temperature. The weight of the ground fruit powder was measured, and the powder was then kept at 4 °C for 8 h. The thawed fruit powder was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and weighed for subsequent calculation of juice yield. 1.00 g of NaCl and 5.00 mL of grape juice were added to a vial, which was then weighed. Subsequently, 10 μL of the internal standard (4-methyl-2-pentanol, 1.0018 mg/mL) was rapidly added, and the vial was immediately capped.

Agilent 6890 GC coupled with Agilent 5975B MS (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for the volatile compounds determination. The capillary column was an Agilent 19,091 N-136 HP-INNOWax Polyethylene Glycol column (60.0 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The carrier gas was helium (purity >99.999 %) with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The system was operated in splitless mode. The ionization energy was set at 70 eV. The ion source temperature was maintained at 230 °C, and the GC–MS interface temperature was set at 280 °C. The mass scan range was from 30 to 350 u.

The qualitative analysis of compounds was performed by matching the retention times, retention indices, and mass spectra of the detected peaks in the samples with those of the reference standards and the retention indices and mass spectra information in the NIST 2014 standard library. Quantitative analysis was conducted using the external standard method. First, standards were dissolved in simulated grape juice to prepare a mixed standard stock solution. Subsequently, this stock solution was diluted to various concentration gradients using simulated grape juice. The detection conditions for the mixed standard solutions were kept consistent with those for the samples. For compounds without available standards, quantification was performed using standards with similar chemical structures or comparable carbon atom numbers.

2.5. Odor activity values (OAVs) and aroma profiles

The OAVs of compounds were defined as the ratio of their concentration in the grape berries to their odor threshold in water. To simulate the aroma characteristics of grapes, volatile compounds were grouped according to similar odor descriptors. Subsequently, the sum of odor activity values (ΣOAV) was calculated. In this study, volatile compounds were classified into nine aroma series, namely floral, fruity, sweet, herbaceous, wood, earthy, fatty, roasty, and sour. Due to the complexity of aroma characteristics, some volatile compounds may be included in several different aroma series.

2.6. Sensory analysis of the grape berries

The panelists involved in the experiment were selected from the sensory group of the Grape and Wine Research Center of China Agricultural University. All panelists had undergone systematic sensory evaluation training and were trained in relevant indices of table grapes. A panel of 10 members (5 females and 5 males; age 23–30 years; all master's or Ph.D. candidates in food science) participated in the formal experiment. The study was conducted in a room with uniform and bright illumination, no noise, and a constant temperature of 23–25 °C. The names of cultivars were represented by codes. The grape samples were washed with tap water, air-dried, and placed in the sensory room for 1 h before evaluation. The scoring criteria covered three major categories: appearance, flavor, and taste. Appearance included size and shape; flavor included sweetness, acidity, and aroma intensity; taste included texture, crunchiness, firmness, juiciness, and skin thickness, totaling 10 specific sensory attributes (Supplementary Table 2). During the evaluation, panelists first smelled the aroma of the berries, then thoroughly chewed them, consuming 3–5 berries per cultivar. Subsequently, they rated the 10 sensory attributes on a scale of 0–10. Evaluations were conducted independently by panel members.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2021 software was used for data organization and calculation of standard curves, means, and standard deviations. SPSS 22.0 was used for one-way ANOVA (Duncan's test, p < 0.05). GraphPad Prism 8 and Chiplot were used for graphing. The principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) were conducted by using MetaboAnalyst.

3. Results

3.1. The physico-chemical characteristics of the grape berries

The hundred berries weight, berry width, berry length, shape lndex, pH, total soluble solid, titratable acidity, TSS-to-TA ratio were measured (Fig. 1). There were significant differences in the berry weights among different cultivars. For 100 berries, the weight of ‘Huangjinmi’ in 2022 was 871.53 g, which was the highest among all the cultivars. The 100 berries weight of ‘Rubin Muscat’ and ‘Klimbamak’ also exceeded 700 g, while ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ had the smallest weight, with less than 300 g. The morphological characteristics of grapes were expressed by the berry width, length, and shape index. From the Fig. 1, it was evident that ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ exhibited the smallest dimensions across all the cultivars analyzed. All cultivars had a shape index >1. However, some cultivars were nearly round, such as ‘Rubin Muscat’, some are broad lipsoid, like ‘Ruidu Kemei’. The shape index of ‘Klimbamak’ was greater than 2.5, giving it a cylindric shape, which might be precisely the novel and unique product that consumers were seeking. Solely relying on the TSS and TA did not comprehensively reflect the true taste. It was common to utilize the ratio of these two parameters to evaluate the flavor of the fruit. The TSS/TA ratio was a widely recognized maturity index that could be used to predict the perceived balance of sweetness and acidity for each cultivar (Nelson et al., 1973). So the pH, TSS, and TA of these fruits were measured, and the TSS/TA values were calculated. It was noteworthy that significant variations were also observed among the same cultivar across different years. In these cultivars, pH ranged from 3.52 to 4.72. TSS values were higher than 16°Brix. The TA ranged from 2.35 to 4.21 g/L, and the TSS/TA values were between 3.99 and 9.14 g/L. These results demonstrated that all grape berries had achieved their stages of ripeness. It was observed that the ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ harvested in 2023 exhibited the highest pH, the highest TSS, and nearly the lowest TA, thereby yielding the highest TSS/TA.

Fig. 1.

The physico-chemical characteristics of seven cultivars in 2022 and 2023. All values shown are means ± standard deviations (n = 3). Different lower-case letters in the same column indicate significant differences (Duncan's multiple range test at p < 0.05).

3.2. The sugars and organic acids of the grape berries

The composition of sugars and organic acids played a significant role in the taste of table grapes. The predominant sugars are glucose and fructose, with only trace sucrose concentration in V. vinifera grapes (Liu et al., 2006). Among the several organic acids present in grapes, the most abundant were typically tartaric and malic acids, while citric acid was present in minor proportions (Lima et al., 2022). In this study, the sugars detected in grape berries were glucose and fructose. The ratio of glucose to fructose was generally 1:1 across all grape cultivars, although minor variations existed among different cultivars (Fig. 2). Glucose concentration was slightly higher than that of fructose, accounting for 50.31 % to 55.24 % of the total sugar concentration. In this study, the organic acids detected were tartaric acid, malic acid, and citric acid. Tartaric and malic acids constituted over 95 % of the total organic acid concentration, respectively ranging from 31.94 % to 57.30 % and 41.57 % to 66.74 %, while citric acid accounted for only 0.51 % to 4.06 % of the total. Among the seven cultivars examined, most had higher levels of malic acid than tartaric acid. Exceptions were ‘Wuhe Cuibao’, in which the levels of tartaric acid exceeded those of malic acid. Citric acid levels were significantly lower than the other two organic acids in both years for all tested cultivars. Significant differences were observed in the levels of sugar and organic acid components among the seven table grape cultivars (Table 2). ‘Ruidu Kemei’ in 2022 had the highest total sugar concentration at 350.79 g/kg fresh weight (FW), with the glucose and fructose concentrations of 178.46 and 172.33 g/kg FW, respectively. ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ in 2022 had the lowest sugars at 229.73 g/kg FW. The figure showed that the difference in total sugar concentration between 2022 and 2023 was not significant. ‘Huangjinmi’, and ‘Klimbamak’, had higher total sugar concentration in 2022 than in 2023. Conversely, the total sugar concentration in the remaining five cultivars was lower in 2022 than in 2023. This trend was consistent with the changes in total soluble solid over the two years. ‘Ruidu Kemei’ in 2022 had the highest total organic acid concentration, reaching 11.18 g/kg FW, while ‘Ruidu Kemei’ in 2023 had the lowest total organic acid concentration at 7.90 g/kg FW. The total organic acid concentration in most grape cultivars was lower in 2022 than in 2023, with only ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ being an exception. It might be caused by differences between cultivars as well as differences in climate between the two years.

Fig. 2.

Compositional analysis of sugars (A) and organic acids (B) of seven cultivars in 2022 and 2023. H, ‘Huangjinmi’; RK, ‘Ruidu Kemei’; RX, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’; RM, ‘Rubin Muscat’; BW, Bixiang Wuhe’; WC, ‘Wuhe Cuibao’; K, ‘Klimbamak’.

Table 2.

Sugars and organic acids concentrations (g/kg FW) of the seven cultivars in 2022 and 2023.

| Years | Cultivars | Glucose | Fructose | Total Sugars | Tartaric Acid | Malic Acid | Citric Acid | Total Acids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | ‘Huangjinmi’ | 130.16 ± 13.44de | 120.26 ± 8.05def | 250.42 ± 20.43cde | 4.56 ± 0.40a | 5.23 ± 0.23 cd | 0.07 ± 0.00 fg | 9.85 ± 0.64bc |

| ‘Ruidu Kemei’ | 133.13 ± 8.98de | 116.90 ± 7.31ef | 250.03 ± 16.29 cde | 3.23 ± 0.34def | 5.65 ± 0.52bc | 0.06 ± 0.01gh | 8.94 ± 0.44cde | |

| ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ | 178.46 ± 24.25a | 172.33 ± 22.26a | 350.79 ± 46.50a | 4.39 ± 0.40ab | 6.72 ± 0.74a | 0.08 ± 0.01ef | 11.18 ± 1.14a | |

| ‘Rubin Muscat’ | 139.12 ± 10.13 cd | 136.61 ± 4.31 cd | 275.73 ± 10.83bc | 3.54 ± 0.18cde | 4.30 ± 0.36ef | 0.06 ± 0.01gh | 7.90 ± 0.19e | |

| ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ | 121.53 ± 4.53de | 114.79 ± 2.65ef | 236.32 ± 7.17de | 2.83 ± 0.38f | 5.67 ± 0.29bc | 0.36 ± 0.02a | 8.86 ± 0.67cde | |

| ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ | 141.64 ± 13.62 cd | 130.54 ± 13.02cde | 272.18 ± 26.55bcd | 4.82 ± 0.18a | 5.71 ± 0.51bc | 0.12 ± 0.01c | 10.65 ± 0.68ab | |

| ‘Klimbamak’ | 124.14 ± 6.87de | 122.60 ± 6.44cdef | 246.74 ± 11.76cde | 3.14 ± 0.14def | 6.48 ± 0.14a | 0.09 ± 0.00de | 9.72 ± 0.21bc | |

| 2023 | ‘Huangjinmi’ | 142.65 ± 5.03 cd | 128.67 ± 2.80cdef | 271.32 ± 7.36bcd | 3.07 ± 0.33ef | 4.77 ± 0.14de | 0.05 ± 0.01 h | 7.89 ± 0.33e |

| ‘Ruidu Kemei’ | 156.03 ± 6.05bc | 139.90 ± 9.47c | 295.93 ± 15.42b | 3.88 ± 0.09bc | 5.20 ± 0.35 cd | 0.11 ± 0.01 cd | 9.19 ± 0.29 cd | |

| ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ | 174.15 ± 9.66ab | 156.47 ± 5.95b | 330.62 ± 15.54a | 3.66 ± 0.31 cd | 4.65 ± 0.33de | 0.12 ± 0.00c | 8.43 ± 0.31de | |

| ‘Rubin Muscat’ | 116.93 ± 13.36e | 112.80 ± 11.66ef | 229.73 ± 25.01e | 4.29 ± 0.33ab | 3.92 ± 0.41 fg | 0.10 ± 0.01d | 8.31 ± 0.73de | |

| ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ | 125.38 ± 8.84de | 119.07 ± 7.35def | 244.45 ± 15.17cde | 4.59 ± 0.50a | 3.33 ± 0.48 g | 0.09 ± 0.01de | 8.02 ± 0.93e | |

| ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ | 137.28 ± 7.14cde | 111.22 ± 1.19f | 248.51 ± 8.33 cde | 4.54 ± 0.19a | 6.26 ± 0.33ab | 0.19 ± 0.01b | 10.98 ± 0.32a | |

| ‘Klimbamak’ | 126.82 ± 8.95de | 115.82 ± 8.99ef | 242.64 ± 17.81cde | 4.71 ± 0.31a | 5.07 ± 0.33 cd | 0.05 ± 0.00 h | 9.82 ± 0.17bc |

3.3. The volatile compounds of the grape berries

In this study, a total of 61 volatile compounds were detected in 7 table cultivars, including 24 terpenes, 7 C6 compounds, 4 esters, 4 norisoprenoids, 11 aldehydes, 1 ketone, 8 alcohols, and 2 other substances (Supplementary Table 3). The volatile concentration exhibited significant differences between different grape cultivars. In 2022 and 2023, the most abundant volatile compounds in ‘Ruidu Kemei’ were terpenes and C6 compounds, especially the terpenes. In 2023, the same was true for ‘Wuhe Cuibao’. For ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ in 2022, as well as ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ and ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ in 2022 and 2023, terpenes and C6 compounds were both predominant volatiles, but C6 compounds were found mostly. C6 compounds were the dominant volatiles in ‘Huangjinmi’, ‘Rubin Muscat’, and ‘Klimbamak’. All cultivars contained few other volatiles (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Each class of volatile compounds of seven cultivars in 2022 and 2023. H, ‘Huangjinmi’; RK, ‘Ruidu Kemei’; RX, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’; RM, ‘Rubin Muscat’; BW, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’; WC, ‘Wuhe Cuibao’; K, ‘Klimbamak’.

Terpenes, comprising the largest class of secondary aroma metabolites, had application in the pharmaceutical, flavor fragrance, and biofuel industries (Tetali, 2019). Terpenes were the primary compounds in Muscat aroma cultivars, with their concentrations significantly exceeding those in other cultivars (Wu et al., 2019). As primary volatile compounds in ‘Ruidu Kemei’, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’, and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’, terpenes constituted 17.93 %–57.62 % of the volatile concentrations, with the concentration ranging between 1125.31 and 22,214.14 μg/kg FW. Linalool, nerol, and geraniol, were the main terpenes, followed by terpinolene, α-terpilene, d-limonene, β-myrcene, β-ocimene, α-terpineol, consistent with the findings of Wang (W.-N. Wang et al., 2023). Although some terpenes were present in lower amounts, their very low odor thresholds might made them still the major aroma contributors to the Muscat odor.

C6 compounds served as the important volatiles in grape berries and are known to contribute to green leaf, green grassy, and herbaceous odors (C. Yang et al., 2009). Neutral cultivars contain few volatiles other than C6 compounds (Aubert & Chalot, 2018). In this study, C6 compounds constituted more than 92.19 % of the total in ‘Huangjinmi’, ‘Rubin Muscat’, and ‘Klimbamak’. In other cultivars, the percentage of C6 compounds contributing to the total volatiles varied from 41.40 % to 79.31 %. Hexanal and (E)-2-hexenal were the dominant C6 volatile compounds, which was consistent with (Wu et al., 2016). It is noteworthy that (E)-2-hexen-1-ol was identified as a predominant C6 compound exclusively in the ‘Klimbamak’, with concentrations reaching up to 9439.25 μg/kg FW.

Esters were mainly the characteristic aroma substances of strawberry odor (Y. Li et al., 2023). In this study, esters were detected as low volatiles in all cultivars, which ranged from 20.60 to 351.00 μg/kg FW. The main ester was butyl butyrate, which had a pleasant aroma reminiscent of a sweet, fruity pineapple aroma (Xin et al., 2019).

Four norisoprenoids were detected in this study, including 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-ol, β-damascenone, and cis-geranyl acetone. Norisoprenoids were also present as low compounds in the seven cultivars, with concentrations less than 20 μg/kg FW. However, norisoprenoids usually made a great contribution to the aroma quality of grapes owing to their low odor threshold and pleasant floral fruit characteristics (Teranishi et al., 1992).

In this study, the total amount of aldehydes and ketones accounted for 0.29 %–1.38 % of all volatile compounds. The predominant aldehyde compound detected was benzeneacetaldehyde. Benzeneacetaldehyde had a low odor threshold (4 μg/L in water), and might contribute floral and honey aromas to the grapes (Wu et al., 2016). The only ketone detected during the experiment was acetophenone, which was detected exclusively in the ‘Klimbamak’.

The proportion of alcohols in total volatile concentration was not high, and the concentration of alcohols in all cultivars did not exceed 200 μg/kg FW. In addition to the aforementioned substances, this experiment also detected trace amount of hexanoic acid and (E)-2-hexenoic acid in table grapes.

According to the aromatic compounds, grapes could be divided into Muscat, Strawberry, Nrutral, and Mixed aroma types (C. Yang et al., 2009). Studies showed that terpenes were the most important aromatic compounds in Muscat type grapes, while esters such as methylanthranilate contribute to the strawberry-like odor, and cultivars with both muscat and strawberry aromas were considered Mixed type grapes (J. Wang & Luca, 2005; Y. Yang et al., 2019). In this study, the compounds constituting the strawberry-like aroma, such as esters, were very low in all cultivars, whereas abundant terpenes were observed in ‘Ruidu Kemei’, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’, and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’. Therefore, based on the aromatic compounds, ‘Ruidu Kemei’, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’, and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ could be classified as Muscat aroma type grapes, while the cultivars ‘Huangjinmi’, ‘Rubin Muscat’, and ‘Klimbamak’ could be classified as Neutral aroma type grapes. Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) of the volatile compounds from the seven cultivars over two years further validated this classification (Figs. 6 and Fig. 7). The results showed that principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) explained 49.3 % and 19.9 % of the total variance respectively. A terpene-rich cluster comprising ‘Ruidu Kemei’, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ occupied the negative PC1 axis and was strongly associated with floral/fruit volatiles such as α-terpineol, nerol and β-myrcene, whereas ‘Huangjinmi’, ‘Rubin Muscat’ and ‘Klimbamak’ were positioned on the positive side of PC1 and were characterized by green-note compounds including hexanal and (E)-2-hexenal. The HCA dendrogram (Fig. 6(B)) confirmed this classification, with the cultivars splitting into two main branches at a linkage distance of approximately 20, in full agreement with the PCA results. Thus, the aroma types can be simplified into muscat and neutral categories, offering a straightforward reference for breeders and market segmentation.

Fig. 6.

PCA (A) scores plot and (B) loading plot of 61 volatile compounds of seven cultivars in 2022 and 2023.

Fig. 7.

HCA dendrogram (Ward clustering algorithm, Pearson distance measure) of seven cultivars based on volatile compound concentrations in 2022 and 2023.

3.4. Odor activity values (OAVs) and aroma profiles of the grape berries

OAV was commonly used to assess the contribution of odorant substances to sensory perception (Guth, 1997). Substances with OAVs ≥1 played a role in shaping the overall aroma profile of the sample (Liu et al., 2020). Supplementary Table 4 showed the results of OAV analysis from the seven table grape cultivars for the years 2022 and 2023. The odor thresholds and descriptors were obtained from the previous literatures (Javed et al., 2018; Tura et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2016, Wu et al., 2018, Wu et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2017). In this study, 26 aroma-active compounds (OAVs ≥ 1) were detected, including 14 terpenes, 5 C6 compounds, 1 norisoprenoid, 4 aldehydes, and 2 alcohols. Over the two years, the same cultivars had roughly the same aroma-active compounds detected. ‘Ruidu Kemei’ had the highest number of aroma-active compounds detected. In ‘Huangjinmi’, ‘Rubin Muscat’, and ‘Klimbamak’ very few terpenes threshold aroma components were detected. In the other four cultivars, linalool, as a major terpene, contributed to the floral, fruity, and sweet aromas with its high OAV. In addition, C6 compounds were major contributors to the aroma, as seen in hexanal and (E)-2-hexenal, with extremely high OAV in most cultivars, primarily contributing to the green aroma. β-damascenone, which imparts floral, fruity, and sweet aromas to berries, plays a significant role in shaping the aroma profiles of various cultivars. Its OAV ranged from 31.52 to 192.39 across the seven cultivars. Some aldehydes had distinctive odors, such as nonanal which exhibited a fatty odor, and decanal which showed a sour odor. Due to their low OAV, these aromas were not easily perceived in grapes and and might have been masked by other more intense aromas. The same applied to 1-octen-3-ol for its mushroom odor. (Z)-2-penten-1-ol (among the alcohols), with a almond, fruity, and green odor, was detected only in ‘Rubin Muscat’ and ‘Klimbamak’.

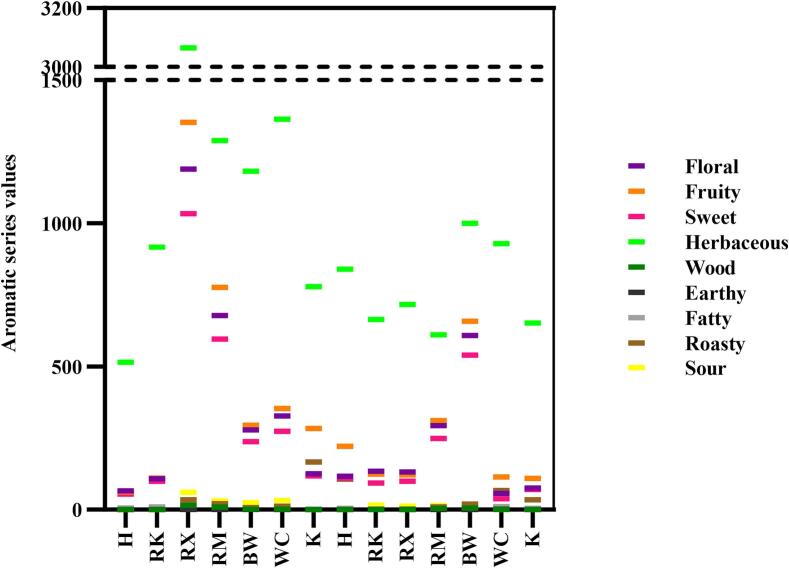

In this study, aromatic compounds were categorized into nine aroma series: floral, fruity, sweet, herbaceous, woody, earthy, fatty, roasty, and sour. To quantify the contribution of specific aroma compounds to overall olfactory perception, the OAVs for each aroma series were calculated (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 5). The analysis of the aroma series indicated that the most dominant aroma profiles of seven table grape cultivars were herbaceous aroma (∑OAV > 500). The herbaceous aroma in all grape cultivars primarily originated from hexanal. It was worth noting that certain substances, such as linalool and β-damascenone, which played a decisive role in the aroma profile of grapes, could simultaneously exhibit floral, fruity, and sweet aroma. This led to the aroma series values of these three aroma series being relatively close to each other. In 2022, the floral, fruity, sweet and herbaceous aroma series values of ‘Ruidu Kemei’ were higher than those in other cultivars. Sour and roasty aroma series have relatively low values. β-myrcene and (Z)-2-penten-1-ol imparted a roasty aroma series to grapes, with ‘Rubin Muscat’ having the highest roasty aroma series value among all cultivars. The wood, earthy, and fatty series had a low contribution to the overall aroma in all cultivars (∑OAV < 20).

Fig. 4.

Aroma series values for seven cultivars in 2022 and 2023. H, ‘Huangjinmi’; RK, ‘Ruidu Kemei’; RX, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’; RM, ‘Rubin Muscat’; BW, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’; WC, ‘Wuhe Cuibao’; K, ‘Klimbamak’.

3.5. Sensory analysis of the grape berries

The results of the sensory evaluation of the seven table grape cultivars in 2023 were summarized in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 6. The appearance parameters were scored according to the degree of size and shape of berries. The flavor parameters were scored according to the sweetness, acidity, and aroma intensity of berries. The taste parameters were scored according to the degree of texture, crunchiness, firmness, juiciness of berries, and thickness of skins. As indicated, regarding appearance, the score of ‘Huangjinmi’ was higher than that of other cultivars. In contrast, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ with its small berries, was markedly lower than other cultivars. The linkage analysis of their hundred berry weight, berry width, and length indicated that the public prefers large grapes. ‘Klimbamak’, with its finger-like shape, achieved a notable appearance score attributed to its distinctive form. In terms of flavor, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ had high sweetness, low acidity, and strong aroma. ‘Huangjinmi’ and ‘Ruidu Kemei’ had a relatively balanced sweet-sour profile. ‘Rubin Muscat’, with low sweetness and inconspicuous aroma, had the lowest flavor score. In taste, ‘Huangjinmi’ and ‘Ruidu Kemei’ had high scores in texture, crunchiness, firmness, and possessed moderate juiciness. They may be more suitable for consumers who prefer crisp berries. ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ and ‘Rubin Muscat’ had relatively low scores in texture, crunchiness, and juiciness, with moderate firmness, and their skins were significantly thinner than those of other cultivars. These characteristics may make them more suitable for consumers who prefer soft fruits. Of all the cultivars, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ were the softest and had the most juice. ‘Klimbamak’ had the highest crunchiness and abundant juice, which contributed to its good taste quality. Overall, each cultivar had its unique sensory qualities.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of sensory attributes among seven cultivars in 2023. H, ‘Huangjinmi’; RK, ‘Ruidu Kemei’; RX, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’; RM, ‘Rubin Muscat’; BW, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’; WC, ‘Wuhe Cuibao’; K, ‘Klimbamak’.

4. Discussion

Wild grape germplasm resources are generally round in shape. However, with the acceleration of breeding programs and the increase in cultivar diversity, an expanding array of novel berry shapes emerged (C. Zhang et al., 2022). For instance, ‘Klimbamak’ with its distinctive fruit shape, exemplifies the contribution of modern breeding to fruit shape diversification. In this study, ‘Huangjinmi’ and ‘Klimbamak’ achieved higher sensory scores for appearance due to their larger berry size, suggesting that they were likely the most visually appealing cultivars. The size and shape index of all cultivars remained relatively stable over the two-year period, indicating a high degree of consistency in shape among these cultivars, which is advantageous for grape processing and marketing.

Pewvious research indicated that higher sugar concentration and moderate acidity were important indicators of concentrated flavor and superior quality in grapes (C. Yang et al., 2024). The TSS/TA was significantly positively correlated with consumer preference (Nelson et al., 1973). Except for the ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’, the TSS-to-TA ratios for other cultivars increased in 2023 compared to 2022, while the TA and total organic acid levels decreased. It was possible that due to the relatively late harvest in 2023 compared to 2022, there might be more time for photosynthesis, sugar accumulation and acid decline, as well as experiencing natural dehydration, which further concentrates the sugars and resulted in higher sweetness and lower acidity in the berries (Bondada et al., 2017; Plantevin et al., 2024; Zang et al., 2025). Sensory evaluation provided subjective assessments, and when combined with objectivity assessments based on primary metabolites, it helped to comprehensively evaluate the flavor quality of fruits. ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ received the highest sweetness ratings, and the lowest acidity ratings in sensory analysis, which correspond to their higher TSS-to-TA ratios, suggesting they might be the most favored cultivars. ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ had almost the lowest sweetness rating in sensory analysis, yet its total sugar concentration was not low, which might be related to its highest titratable acidity and total organic acid concentration. ‘Klimbamak’ exhibited a higher acidity rating in sensory analysis, and also had a higher total organic acid concentration. ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ and ‘Klimbamak’ might appeal to consumers who preferred a more acidic flavor. ‘Huangjinmi’ and ‘Ruidu Kemei’, with their higher sweetness ratings, also had the highest acidity ratings in sensory analysis, potentially making them suitable for consumers who enjoyed a full-bodied structure. Despite having a relatively high TSS-to-TA ratio, the sensory profile of ‘Rubin Muscat’ was characterized by a mild sweetness ratings and moderate acidity ratings in sensory analysis. This was likely due to the significant balance of acidity and sweetness perception. As a result, its flavor profile might appeal to consumers who prefer a lighter flavor.

Although climate affects aroma synthesis, it does not change the types of compounds, confirming the cultivars' stable aroma profiles. Based on the composition and concentration of grape volatiles, ‘Ruidu Kemei’, ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’, and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ were classified as Muscat types, while ‘Huangjinmi’, ‘Rubin Muscat’, and ‘Klimbamak’ were classified as Neutral types (C. Yang et al., 2009). Abundant terpenes were observed in muscat-types grapes, while neutral-type grapes had few volatiles other than C6 compounds. This study demonstrated that the aroma profiles of both neutral-type and muscat-type cultivars were predominantly influenced by two key compounds: hexanal and (E)-2-hexenal, which exhibited the highest OAVs. Furthermore, the aroma of the muscat-type cultivars received a significant contribution from linalool. These findings revealed that the differential contributions of aroma components across different grape aroma types and provided insights into the mechanisms by which these compounds shaped the distinctive olfactory characteristics. In certain styles of wine, such as a moderate earthiness or toasty aromas were not only tolerated but are often perceived as contributing to the wine's flavor complexity (Rabitti et al., 2022). However, for table grapes, the quality criteria differ from those used for wine grapes. Therefore, the evaluation of the aroma quality of table grapes should focus on their purity, richness, and pleasantness to ensure that consumers could enjoy the most natural and essential flavors of the grapes. In this study, volatile compounds were grouped into nine aroma series based on their odor descriptors, and the sum of odor activity values was calculated to establish preliminary aroma fingerprints for the seven white table grape cultivars. The aroma characteristics of the seven cultivars in this study were predominantly herbaceous, fruity, floral and sweet, which were in accordance with the quality assessment criteria for table grapes. Although the absolute ∑OAVs fluctuated markedly between seasons, the year-specific datasets revealed repeatable, cultivar-specific ranking patterns: the herbaceous series of ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ ranked first in both 2022 and 2023, the floral-fruity-sweet clusters of ‘Rubin Muscat’ consistently held the second position, and ‘Klimbamak’ remained the lowest for all series while exhibiting the highest roasty value in each year (Fig. 4). These “rank-conserved” traits are proposed as supplementary cultivar-level aroma fingerprints, provided that their stability is further confirmed across additional seasons. The perception of aroma was a complex process that involves two pathways: orthonasal and retronasal olfaction (Ni et al., 2015). Orthonasal olfaction refered to the detection of environmental aromas through the nostrils, while retronasal olfaction emphasized the perception of food aromas during mastication (Hannum et al., 2018). Retronasal olfaction was closely associated with interactions between olfactory, gustatory, and oral tactile sensations (Spence, 2013). Therefore, certain volatile compounds might not be significant in terms of olfactory perception alone but could significantly influence the overall aroma perception when combined with sweetness or sourness (Cho & Peterson, 2025). The complexity of aroma perception and its interaction with taste highlighted the importance of multisensory integration in flavor perception. This research indicates that, the aroma intensity ratings of ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ and ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ in sensory analysis were significantly higher than those of other cultivars, potentially making them more suitable for consumers seeking a strong olfactory experience.

In the fields of horticulture and pomology, widely grown and well-known cultivars could be categorized by their texture into “crunchy and firm” types (e.g., ‘Red Globe’) and “soft and juicy” types (e.g., ‘Kyoho’ and ‘Muscat Hamburg’) (Sato et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2015). This classification reflected the differences in fruit structure and eating quality among different cultivars, which held significant implications for the selection of grape cultivation, market positioning, and the study of consumer preferences. In, this study ‘Huangjinmi’, ‘Ruidu Kemei’ and ‘Klimbamak’ were closer to the characteristics of “crunchy and firm” cultivars. In contrast, ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ and ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ were more inclined towards the traits of “soft and juicy” grape cultivars.

5. Conclusions

The study highlighted the diverse characteristics of the seven table grape cultivars popular in China in terms of appearance, flavor, aroma, and texture, and each cultivar had its own unique attributes. The findings emphasized the importance of integrating sensory evaluation with physico-chemical, primary metabolite, and volatile compounds to comprehensively assess the quality of table grapes. ‘Huangjinmi’ featured larger berries and a full flavor structure, aligning with the neutral aroma type and offering a firm and juicy mouthfeel. ‘Ruidu Kemei’ was characterized by its rich and full flavor profile, falling into the muscat aroma type with a crisp and juicy texture. ‘Ruidu Xiangyu’ was noted for its relatively high acidity and low sugar concentration, with a thin skin and moderate hardness and crispness, belonging to the Muscat aroma type. ‘Rubin Muscat’ had a mild sweetness and balanced acidity, categorized as a neutral aroma grape with a thin skin and moderate hardness and crunchiness. ‘Bixiang Wuhe’ had the smallest berry size among the group, with high sweetness, muscat aroma type, and a soft, juicy texture. ‘Wuhe Cuibao’ had heart-shaped berries, high sweetness, and belonging to the Muscat aroma type, also presenting a soft and juicy texture. ‘Klimbamak’ was distinguished by its unique fruit shape and larger berry size, and it was categorized as a neutral aroma grape with relatively high acidity and a firm, crisp texture. Investigating the fruit flavor profile, particularly the differences and genetic patterns of aroma compounds, holds significant theoretical and practical importance. Additionally, researches on the cultivar characteristics could precisely match market demands, offering support for the promotion of grape cultivars and satisfying consumer's needs for high-quality and diverse grapes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shang-Lin Wang: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Hai-Bei Yan: Investigation, Data curation. Lin Wang: Investigation. Xing-Chi Chen: Investigation. Jun Wang: Writing – review & editing. Fei He: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Ethical statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Agricultural University Research Ethics Committee, (reference number CAUHR-20220711). Participants gave informed consent via the statement “I am aware that my responses are confidential, and I agree to participate in this survey” where an affirmative reply was required to enter the survey. They were able to withdraw from the survey at any time without giving a reason. The products tested were safe for consumption.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the earmarked fund for China Agriculture Research System, CARS-29.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2025.103157.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aubert C., Chalot G. Chemical composition, bioactive compounds, and volatiles of six table grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L.) Food Chemistry. 2018;240:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.07.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondada B., Harbertson E., Shrestha P.M., Keller M. Temporal extension of ripening beyond its physiological limits imposes physical and osmotic challenges perturbing metabolism in grape (Vitis vinifera L.) berries. Scientia Horticulturae. 2017;219:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Canturk S., Tangolar S., Tangolar S., Ada M. Volatile composition of seven new hybrid table grape cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.). Applied fruit. Science. 2025;67(1):12. doi: 10.1007/s10341-024-01229-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I.H., Peterson D.G. Analytical approaches to flavor research and discovery: From sensory-guided techniques to flavoromics methods. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2025;34(1):19–29. doi: 10.1007/s10068-024-01765-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira V., Lopez R. The actual and potential aroma of winemaking grapes. Biomolecules. 2019;9(12):818. doi: 10.3390/biom9120818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth H. Quantitation and sensory studies of character impact odorants of different white wine varieties. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1997;45(8):3027–3032. [Google Scholar]

- Hannum M., Stegman M.A., Fryer J.A., Simons C.T. Different olfactory percepts evoked by orthonasal and retronasal odorant delivery. Chemical Senses. 2018;43(7):515–521. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjy043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV). (2023). Annual assessment of the world vine and wine sector in 2023. Retrieved from https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/documents/Annual_Assessment_2023.pdf. Accessed May 6 2025.

- Javed H.U., Wang D., Shi Y., Wu G.-F., Xie H., Pan Y.-Q., Duan C.-Q. Changes of free-form volatile compounds in pre-treated raisins with different packaging materials during storage. Food Research International. 2018;107:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadatkar A., Sawant C.P., Thorat D., Gupta A., Jadhav S., Gawande D., Magar A.P. A comprehensive review on grapes (Vitis spp.) cultivation and its crop management. Discover. Agriculture. 2025;3(1):9. doi: 10.1007/s44279-025-00162-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., He L., Song Y., Zhang P., Chen D., Guan L., Liu S. Comprehensive study of volatile compounds and transcriptome data providing genes for grape aroma. BMC Plant Biology. 2023;23(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s12870-023-04191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima M.M., Choy Y.Y., Tran J., Lydon M., Runnebaum R.C. Organic acids characterization: Wines of pinot noir and juices of ‘Bordeaux grape varieties’. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2022;114 [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., An K., Su S., Yu Y., Wu J., Xiao G., Xu Y. Aromatic characterization of mangoes (Mangifera indica L.) using solid phase extraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and olfactometry and sensory analyses. Foods. 2020;9(1):75. doi: 10.3390/foods9010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Wu B., Fan P., Li S., Li L. Sugar and acid concentrations in 98 grape cultivars analyzed by principal component analysis. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2006;86(10):1526–1536. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Chen W., Wang Y., Bai X., Cheng G., Duan C.…He F. Effect of the seasonal climatic variations on the accumulation of fruit volatiles in four grape varieties under the double cropping system. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.809558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez L., da Costa B.S., Vilanova M. Comparative study of different commercial enzymes on release of glycosylated volatile compounds in white grapes using SPE/GC–MS. Food Chemistry. 2025;464 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K.E., Schutz H.G., Ahmedullah M., McPherson J. Flavor preferences of supermarket customers for ‘Thompson seedless’ grapes. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1973;24(1):31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ni R., Michalski M.H., Brown E., Doan N., Zinter J., Ouellette N.T., Shepherd G.M. Optimal directional volatile transport in retronasal olfaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(47):14700–14704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511495112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantevin M., Merpault Y., Lecourt J., Destrac-Irvine A., Dijsktra L., van Leeuwen C. Characterization of varietal effects on the acidity and pH of grape berries for selection of varieties better adapted to climate change. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2024;15:1439114. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1439114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabitti N.S., Cattaneo C., Appiani M., Proserpio C., Laureati M. Describing the sensory complexity of Italian wines: Application of the rate-all-that-apply (RATA) method. Foods. 2022;11(16):2417. doi: 10.3390/foods11162417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A., Yamada M., Iwanami H. Estimation of the proportion of offspring having genetically crispy flesh in grape breeding. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 2006;131(1):46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Spence C. Multisensory flavour perception. Current Biology. 2013;23(9):R365–R369. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Peng W., Zeng L., Xue Y., Lin W., Ye X., Guan R., Sun P. Using power ultrasound to release glycosidically bound volatiles from orange juice: A new method. Food Chemistry. 2021;344 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempere S., Cuzange E., Bougeant J.C., De Revel G., Sicard G. Explicit sensory training improves the olfactory sensitivity of wine experts. Chemosensory Perception. 2012;5(2):205–213. doi: 10.1007/s12078-012-9120-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teranishi R., Takeoka G.R., Guntert M. Flavor precursors: Thermal and enzymatic conversions. Journal of Food Biochemistry. 1992;16(2):131–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.1992.tb00440.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tetali S.D. Terpenes and isoprenoids: A wealth of compounds for global use. Planta. 2019;249(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-3056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tura D., Failla O., Bassi D., Pedo S., Serraiocco A. Cultivar influence on virgin olive (Olea europea L.) oil flavor based on aromatic compounds and sensorial profile. Scientia Horticulturae. 2008;118(2):139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Luca V.D. The biosynthesis and regulation of biosynthesis of Concord grape fruit esters, including ‘foxy’ methylanthranilate. The Plant Journal. 2005;44(4):606–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.-N., Qian Y.-H., Liu R.-H., Liang T., Ding Y.-T., Xu X.-L., Huang S., Fang Y.-L., Ju Y.-L. Effects of table grape cultivars on fruit quality and aroma components. Foods. 2023;12(18):3371. doi: 10.3390/foods12183371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Duan S., Zhao L., Gao Z., Luo M., Song S., Xu W., Zhang C., Ma C., Wang S. Aroma characterization based on aromatic series analysis in table grapes. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1):31116. doi: 10.1038/srep31116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Zhang W., Duan S., Song S., Xu W., Zhang C., Bondada B., Ma C., Wang S. In-depth aroma and sensory profiling of unfamiliar table-grape cultivars. Molecules. 2018;23(7):1703. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Zhang W., Yu W., Zhao L., Song S., Xu W., Zhang C., Ma C., Wang L., Wang S. Study on the volatile composition of table grapes of three aroma types. Lwt. 2019;115 [Google Scholar]

- Xin F., Zhang W., Jiang M. Bioprocessing butanol into more valuable butyl butyrate. Trends in Biotechnology. 2019;37(9):923–926. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Fan X., Lao F., Huang J., Giusti M.M., Wu J., Lu H. A comparative study of physicochemical, aroma, and color profiles affecting the sensory properties of grape juice from four Chinese Vitis vinifera×Vitis labrusca and Vitis vinifera grapes. Foods. 2024;13(23):3889. doi: 10.3390/foods13233889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Wang Y., Liang Z., Fan P., Wu B., Yang L., Wang Y., Li S. Volatiles of grape berries evaluated at the germplasm level by headspace-SPME with GC–MS. Food Chemistry. 2009;114(3):1106–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Jin G.-J., Wang X.-J., Kong C.-L., Liu J., Tao Y.-S. Chemical profiles and aroma contribution of terpene compounds in Meili (Vitis vinifera L.) grape and wine. Food Chemistry. 2019;284:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang X., Du Q., Jiang J., Liang Y., Ye D., Liu Y. Impact of combined grape maturity and selected Saccharomyces cerevisiae on flavor profiles of young ‘cabernet sauvignon’ wines. Food Chemistry: X. 2025;25 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Cui L., Fang J. Genome-wide association study of the candidate genes for grape berry shape-related traits. BMC Plant Biology. 2022;22(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03434-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Cao L., Chen S., Perl A., Ma H. Consumer-assisted selection: The preference for new tablegrape cultivars in China: Consumer-assisted tablegrape selection in China. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2015;21(3):351–360. doi: 10.1111/ajgw.12156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Chen F., Wang L., Niu Y., Xiao Z. Evaluation of the synergism among volatile compounds in oolong tea infusion by odour threshold with sensory analysis and E-nose. Food Chemistry. 2017;221:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.