Abstract

Rationale

High attenuation area (HAA) is a computed tomography (CT) tool that correlates with lung inflammation and fibrosis. Systemic molecular correlates of HAA (e.g., plasma proteins) may inform biological process involved in interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Objectives

Identify plasma proteins that associate with HAA and correlate with a higher probability of developing new-onset fibrotic or subpleural interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA).

Methods

Plasma protein levels were measured using a semiquantitative aptamer-based platform in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA, n=5486) and Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study (SPIROMICS, n=1761). Linear regression models identified HAA-associated proteins after adjustment for demographic and socioeconomic factors, CT scanner parameters, study center, and batch. Associations of HAA-related proteins with new-onset fibrotic or subpleural ILA were examined in MESA participants with ILA assessments on full-lung CT 10 years later. Immunohistochemical staining of select proteins was performed in lung tissue from pulmonary fibrosis cases.

Measurements and Main Results

There were 75 proteins detected that were significantly associated with HAA in MESA and SPIROMICS. Gene ontology analysis of these proteins identified processes involved in immune cell chemotaxis and cellular growth and apoptosis. Seven proteins were associated with a higher probability of new-onset fibrotic or subpleural ILA in MESA and two of these, junctional adhesion molecule-like protein and GTP cyclohydrolase 1 feedback regulatory protein, stained in areas of fibrosis in lung tissue from patients with ILD.

Conclusions

Plasma proteins associated with more HAA are involved in immune and cellular processes and associate with new onset fibrotic-subpleural ILA.

Keywords: Proteomics, interstitial lung disease, radiomics

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most well-defined and severest form of interstitial lung disease (ILD) (1). The current approach to IPF clinical trials recruits patients who already have a diagnosis. However, patients often have a significant burden of fibrosis upon enrollment, and this limits the effectiveness of interventions given the irreversible loss of viable lung tissue. Thus, there has been interest in identifying individuals at the earlier stages of IPF in which treatments may have the most impact at preserving lung function (2, 3).

Clinical trials that test therapies to mitigate the risk of disease progression in IPF necessitate cohort enrichment (2). Computed tomography (CT) scans of the lung and detection of features related to pulmonary fibrosis in individuals without known ILD is a promising tool. Interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA), a qualitative assessment of lung parenchymal abnormalities, is the most well-studied CT assessment (4–9). Also, automated CT methods have emerged that can quantify lung inflammation and fibrosis (10). One such method is high attenuation area (HAA), a densiometric-based method that quantifies the proportion of lung with areas of attenuation between −600 to −250 Hounsfield units. More HAA on CT associates with the MUC5B promoter variant (rs35705950), one of the most common genetic risk factors for IPF, and a higher risk of ILD-related death and hospitalization (11–13).

Circulating biomarkers may also help identify individuals at higher risk of developing ILD. This includes blood-based proteins with recent advances in semiquantitative proteomic platforms that can examine thousands of proteins and their associations with clinical phenotypes. Studies have used semiquantitative proteomics to identify proteins that associate with ILA and quantitative interstitial abnormality (QIA) in cigarette smokers and older adults (14, 15). Whether there are overlapping and distinct protein biomarkers that associate with HAA is unknown. Also, these studies have relied on baseline proteomic measurements but there is interest in whether longitudinal changes of proteins correlate with ILD risk which could have implications on assessing treatment responses in trials (16).

We hypothesized proteomic markers related to extracellular matrix maintenance, vascular integrity, and innate immunity would associate with more HAA on CT scan. We leveraged semiquantitative proteomic and radiologic data in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study (SPIROMICS). Secondarily, we investigated whether HAA-associated protein markers and their change over time were associated with future development of radiological phenotypes concerning for ILD. Immunohistochemical (IHC) stains of proteins that associate with HAA were performed in lung tissue.

METHODS

Study participants

MESA is a longitudinal U.S.-based cohort study that recruited 6,814 adults between the ages of 45–84 years without known cardiovascular disease at Exam 1 (2000–2002) from six U.S. communities (17). There have been subsequent study visits including the most recent visit at Exam 6 (2016–2018). MESA served as the discovery cohort to identify proteins that associate with HAA. For replication we used the SPIROMICS cohort, a U.S.-based prospective cohort comprised mostly of adults with a self-reported history of 20 cigarette pack-years or more and between the ages of 40–80 years at baseline (2010–2015) (18). We used data from these cohorts because protein measurements were obtained from the same assay and HAA assessments were performed from CT scan images using the same protocol (see Methods below). Also, since cigarette smoking exposure is highly prevalent in IPF and other ILD types (19), this was another justification to use SPIROMICS as a replication cohort. In each study, institutional review board approval was obtained from the cohort study sites and written informed consent was provided by each study participant.

SomaScan proteomics

Proteins were quantified using SomaScan Assay version 4.1, an aptamer-based affinity platform (SomaLogic, Inc., Boulder, CO, USA). The SomaScan platform uses short single-stranded DNA aptamer reagents for high throughput multiplexing of proteins (20, 21). SomaScan version 4.1 measures 7,596 aptamers that map to 6,401 unique proteins . In MESA, proteins were measured from samples collected in up to three batches. Proteins were measured from a single batch in SPIROMICS. For modeling purposes, protein levels were log2-transformed. The SomaScan platform has shown excellent specificity and precision of measurements with median coefficients of variation ranging from 3.6–7.0% based on prior literature (20–23).

CT scan assessments

In MESA, participants underwent cardiac CT scans at Exam 1 which captures approximately two-thirds of the lower lung fields. At Exam 5 (2010–2012), participants underwent full-lung CT scans. In SPIROMICS, study participants underwent full-lung CT scans at Visit 1 (2010–2015). Full-lung scans in both cohorts used the MESA Lung/SPIROMICS protocol (24).

HAA was defined as the percentage of voxels with a range of attenuation values between −600 and −250 Hounsfield units and measured with the Pulmonary Analysis Software Suite (PASS) by the University of Iowa’s Advanced Pulmonary Physiomic Imaging Laboratory (13). A trained technician semiautomatically segmented and corrected lung images (25).

Based on the 2020 Fleischner Position Statement, ILA was defined as the presence of non-dependent abnormalities that include ground-glass or reticular abnormalities, traction bronchiectasis, non-emphysematous cysts, honeycombing, and lung distortion and involve at least 5% of a lung zone (9). In MESA, ILA was assessed from Exam 1 cardiac scans (26) and Exam 5 full-lung scans (13). Serial ILA assessments were not available in SPIROMICS at the time of this analysis.

Lung tissue immunohistochemical staining

Candidate protein marker distribution in lung tissue of patients with IPF (n=3) was assessed using IHC staining and compared with tissue from patients without known pulmonary fibrosis undergoing surgical resection (n=3) and emphysema cases (n=3). Specimens were obtained from the University of Virginia Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (BTRF, Charlottesville, VA, USA). Full description of methods is in online supplementary appendix. Two lung pathologists reviewed the immunostaining for candidate proteins associated with HAA.

Statistical analysis

The workflow of HAA-associated proteomic biomarker identification is shown in Figure 1. MESA was the discovery cohort and linear regression models were used to identify proteins that cross-sectionally associate with HAA (continuous variable) at Exam 1. Models were adjusted for potential confounders: age, sex, smoking history, cigarette pack-years, height, weight, waist circumference, education attainment, income, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), lung volume imaged, percent emphysema, scanner precision variables (scanner model, radiation dose, and voxels), study center, and the first five principal components of genetic ancestry (PCA). We also adjusted for batch in the model as a categorical variable. To account for false-discovery, we used a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value <0.05. We then determined which of these proteins replicated in the SPIROMICS cohort using a Bonferroni-adjusted p-value to account for the number of significant proteins from the derivation cohort. The same linear regression model from MESA was used for the SPIROMICS cohort except for eGFR which was not measured in SPIROMICS. The R package, “clusterProfiler”, was used to identify canonical pathways related to those proteins that were associated with HAA in the replication cohort by mapping protein IDs to Entrez IDs and performing Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment pathway analysis (27).

Figure 1.

Workflow of analysis

We then examined whether those HAA-associated proteomic markers that had concordant direction of associations in the discovery and replication cohorts were associated with a higher probability of developing fibrotic or subpleural ILA in MESA on follow-up scan at Exam 5. We chose ILA with fibrotic and/or subpleural features as the outcome because they have the strongest associations with shorter survival, the MUC5B promoter variant, and is the closest to resemble IPF on CT compared with other ILA subtypes (28, 29). We excluded participants who had fibrotic or subpleural ILA detected on their Exam 1 scans for this analysis, because we were interested in identifying proteins that may help identify those individuals at higher risk of developing a radiologic phenotype closest to IPF. Logistic regression models with the presence of fibrotic or subpleural ILA on MESA Exam 5 scans as the outcome were used. Due to differences in clinical outcomes by race and ethnicity in ILD, we performed a sensitivity analysis stratified by self-reported race and ethnicity in MESA (2, 30). Due to the exploratory nature of this analysis, p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for this analysis.

Of those proteins that were significantly associated with new onset fibrotic or subpleural ILA, we examined their change over time in MESA by taking the difference between Exam 1 and Exam 5 measurements. We used logistic regression models to examine the association of changes in these proteins with Exam 5 fibrotic or subpleural ILA. We then used generalized additive models (GAM) to visualize the continuous association between changes in protein measurement and probability of Exam 5 CT fibrotic or subpleural ILA. Age, sex, smoking history, cigarette pack-years, height, weight, waist circumference, glomerular filtration rate, education attainment, income, study center, PCA, batch, and baseline protein level were adjusted for in models. Participants with missing covariate data were excluded from the final analysis. R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for the analysis.

RESULTS

There were 5,486 MESA participants and 1,761 SPIROMICS participants with proteomic data, baseline HAA assessments, and complete covariate data (Figure 1). MESA had lower proportions of males, self-reported non-Hispanic White individuals, and cigarette smokers compared with SPIROMICS (Table 1). The mean percent HAA was higher in MESA (5.00, SD 2.90) than SPIROMICS (4.38, SD 1.84), while percent emphysema was markedly higher in SPIROMICS than MESA. The number of batches in MESA are shown in E-Table 1. Proteins were measured in a single batch for SPIROMICS.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Discovery Cohort MESA (n=5,486) | Validation Cohort SPIROMICS (n=1,781) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62 (10) | 63 (9) |

| Female sex | 2846 (51.9%) | 822 (46.1%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2238 (40.8%) | 1327 (74.5%) |

| Asian | 688 (12.5%) | 15 (0.8%) |

| African American | 1289 (23.5%) | 319 (17.9%) |

| Hispanic | 1271 (23.2%) | 80 (4.5%) |

| Other | 0 | 40 (2.2%) |

| Never smoker | 2480 (45.2%) | 0 |

| Former smoker | 2233 (40.7%) | 1122 (63.0%) |

| Current smoker | 773 (14.1%) | 659 (37.0%) |

| Cigarette pack-years | 12 (22) | 46 (29) |

| Height, cm | 166 (10) | 170 (10) |

| Weight, kg | 79 (17) | 81 (18) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28 (5) | 28 (5) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 98 (14) | 100 (14) |

| Less than high school | 985 (18.0%) | 197 (11.1%) |

| High school | 2552 (46.5%) | 1080 (60.6%) |

| College or beyond | 1949 (35.5%) | 504 (28.3%) |

| Percent high attenuation areas | 5.00 (2.90) | 4.38 (1.84) |

| Lung volume imaged, cm3 | 2787 (806) | 5885(1479) |

| Percent emphysema | 4.17 (4.33) | 7.54 (9.96) |

Abbreviations: MESA=Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; SPIROMICS=Subpopulations of Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study

Percent emphysema defined as percentage of lung voxels below 950 Hounsfield units.

Continuous variables presented as mean (standard deviation).

Categorical variables presented as no. (percentage).

A subset of MESA participants had both HAA and qualitative assessments of interstitial lung abnormalities from Exam 1 scans (E-Table 2). There was a higher proportion of subjects with ground-glass opacities and fibrotic features visualized on CT in the higher HAA group vs. the lower HAA group.

HAA proteomic biomarkers

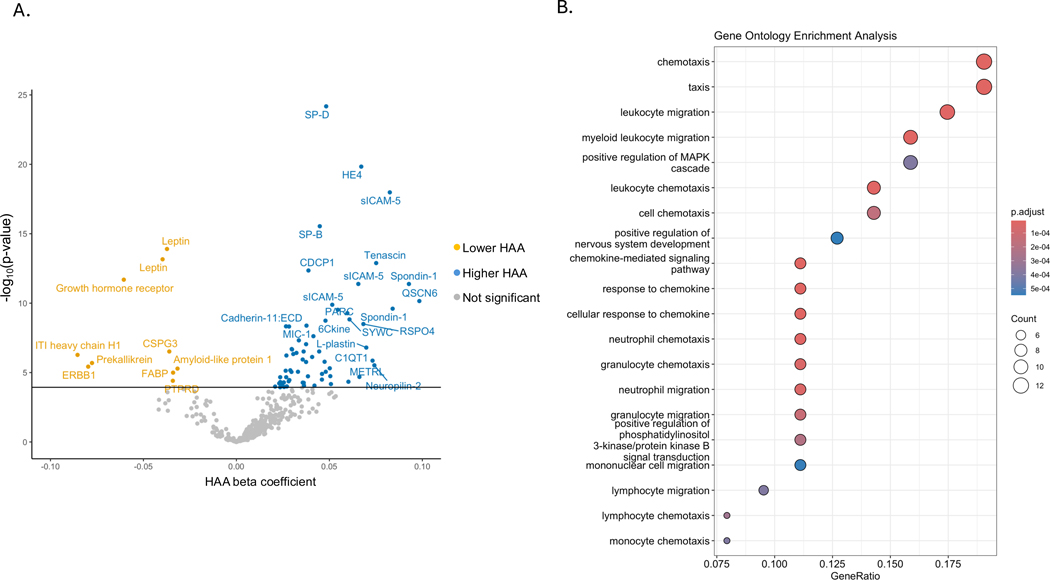

In MESA, 432 proteins were significantly associated with HAA using a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value cutoff <0.05 (online supplementary appendix). From this list of proteins in MESA, 75 were validated in the SPIROMICS cohort using a Bonferroni-corrected p-value cutoff <0.00011574 (0.05/432) (Figure 2A). All the proteins had concordant direction of associations in the two cohorts. Table 2 shows the proteins that were significantly associated with HAA in the discovery and validation cohorts. Several proteins with multiple aptamers were significantly associated with HAA (Table 2). Prior studies from the MESA cohort used ELISA assays to measure MMP-7, IL-6, ITP, and PIINP from stored plasma samples and were associated with HAA (13, 31, 32). Plasma levels of these proteins from SomaScan were positively correlated with levels measured from ELISA assays (E-Figure 1). Although meeting statistical significance, there were weak-to-moderate correlations. Most of the proteins had concordant direction of associations with HAA as the prior studies but were weaker (E-Table 3).

Figure 2.

(A) Volcano plot of proteins associated with high attenuation areas in replication cohort, SPIROMICS. Linear regression model adjusted for age, sex, smoking history, cigarette pack-years, height, weight, waist circumference, education attainment, income, principal components of genetic ancestry, lung volume imaged, percent emphysema, and scanner parameters (scanner manufacturer and radiation dose). Bonferroni-corrected p-value cutoff <0.00011574 used to test for statistical significance. Repeat protein names on volcano plot indicate multiple aptamers. (B) Gene ontology enrichment analysis of validated proteins that associate with high attenuation areas.

Table 2.

Proteins associated with high attenuation areas in discovery and validation cohorts

| MESA | SPIROMICS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Protein | Aptamer ID | Mean difference in HAA (95% CI) | FDR-adjusted p-value | Mean difference in HAA (95% CI) | Bonferroni-adjusted p-value |

| SP-B | 10672–75 | 2.65 (1.76 to 3.55) | 4.6816e−06 | 4.58 (3.48 to 5.70) | 2.8742e−16 |

| HE4 | 11388–75 | 8.81 (7.14 to 10.51) | 1.3199e−22 | 6.94 (5.46 to 8.45) | 1.462e−20 |

| H6ST2 | 13524–25 | 2.44 (1.29 to 3.60) | 0.00276855 | 3.37 (1.87 to 4.88) | 8.7477e−06 |

| BLC | 13701–2 | 3.07 (2.12 to 4.03) | 1.7825e−07 | 2.38 (1.28 to 3.50) | 2.1525e−05 |

| C7 | 13731–14 | 2.68 (1.26 to 4.12) | 0.01067555 | 4.71 (2.58 to 6.89) | 1.2507e−05 |

| Neuropilin-2 | 15387–44 | 4.44 (1.87 to 7.07) | 0.02099152 | 7.70 (4.41 to 11.10) | 3.002e−06 |

| TIM-4 | 15449–33 | 1.98 (0.80 to 3.17) | 0.02667164 | 2.85 (1.48 to 4.24) | 4.2474e−05 |

| Macrophage scavenger receptor:ECD | 15533–97 | 1.97 (0.90 to 3.06) | 0.01397696 | 2.38 (1.17 to 3.61) | 0.00011387 |

| CSPG3 | 15573–110 | −3.62 (−5.01 to −2.20) | 0.0002415 | −3.55 (−4.86 to −2.21) | 3.041e−07 |

| TREM2 | 16300–4 | 1.90 (0.95 to 2.86) | 0.00570707 | 2.39 (1.23 to 3.56) | 4.8179e−05 |

| Cadherin-11:ECD | 16305–10 | 1.03 (0.45 to 1.62) | 0.01865925 | 2.71 (1.80 to 3.62) | 4.6891e−09 |

| PACAP | 16322–10 | 3.02 (1.94 to 4.10) | 1.747e−05 | 2.58 (1.33 to 3.86) | 5.1186e−05 |

| RSPO1 | 16614–27 | 2.34 (1.03 to 3.67) | 0.0173365 | 3.63 (1.86 to 5.44) | 5.2961e−05 |

| CDCP1 | 16818–200 | 3.02 (2.05 to 3.99) | 6.9506e−07 | 3.95 (2.87 to 5.04) | 4.4534e−13 |

| SEM4A | 16915–153 | 4.67 (2.98 to 6.39) | 1.8868e−05 | 4.92 (2.73 to 7.16) | 8.7763e−06 |

| STCH | 17515–6 | 3.26 (1.51 to 5.05) | 0.01169371 | 5.18 (2.79 to 7.63) | 1.8164e−05 |

| SP-D | 19590–46 | 1.50 (0.78 to 2.22) | 0.00355089 | 4.95 (4.00 to 5.90) | 6.6734e−25 |

| SCRB1 | 20534–6 | 1.71 (0.60 to 2.85) | 0.04660857 | 3.68 (2.26 to 5.12) | 3.0479e−07 |

| GFRP | 21118–48 | 2.43 (1.44 to 3.43) | 0.0003612 | 3.42 (2.18 to 4.66) | 4.7867e−08 |

| METRL | 21705–33 | 4.06 (1.75 to 6.43) | 0.01900421 | 6.84 (3.64 to 10.13) | 2.0547e−05 |

| IGFBP-2 | 22985–160 | 1.70 (0.79 to 2.62) | 0.01169371 | 3.28 (2.01 to 4.57) | 3.8437e−07 |

| TIMP-1 | 23173–3 | 2.62 (1.09 to 4.16) | 0.02260558 | 6.15 (4.18 to 8.15) | 5.2641e−10 |

| CLIC3 | 24693–5 | 2.06 (0.76 to 3.37) | 0.03791474 | 3.69 (1.88 to 5.52) | 5.4582e−05 |

| FUBP2 | 24926–9 | 3.61 (2.06 to 5.17) | 0.00075956 | 5.21 (2.62 to 7.87) | 6.7498e−05 |

| 6Ckine | 2516–57 | 2.24 (1.01 to 3.48) | 0.01449739 | 4.91 (3.29 to 6.55) | 1.8347e−09 |

| IGFBP-2 | 2570–72 | 1.77 (0.89 to 2.66) | 0.00531558 | 3.04 (1.88 to 4.21) | 2.1653e−07 |

| Leptin | 2575–5 | −4.04 (−4.88 to −3.19) | 2.3093e−16 | −3.89 (−4.88 to −2.90) | 6.9264e−14 |

| ERBB1 | 2677–1 | −5.35 (−8.12 to −2.50) | 0.01337982 | −7.66 (−10.72 to −4.50) | 3.7441e−06 |

| MPIF-1 | 2913–1 | 3.27 (1.79 to 4.77) | 0.0015716 | 3.92 (2.11 to 5.77) | 1.8583e−05 |

| Growth hormone receptor | 2948–58 | −3.19 (−4.30 to −2.06) | 1.8868e−05 | −5.87 (−7.44 to −4.28) | 2.0457e−12 |

| MIP-1a | 3040–59 | 2.14 (1.20 to 3.09) | 0.00116352 | 4.23 (2.73 to 5.75) | 2.4e−08 |

| PARC | 3044–3 | 3.46 (2.22 to 4.71) | 1.7919e−05 | 5.60 (3.84 to 7.40) | 3.0099e−10 |

| BAFF | 3059–50 | 2.19 (0.77 to 3.63) | 0.04516731 | 4.29 (2.13 to 6.49) | 8.7223e−05 |

| IGFBP-7 | 3320–49 | 3.65 (1.57 to 5.78) | 0.01999258 | 6.21 (3.18 to 9.32) | 4.5851e−05 |

| TSP2 | 3339–33 | 1.53 (0.59 to 2.49) | 0.03328343 | 2.73 (1.65 to 3.81) | 5.9137e−07 |

| BLC | 3487–32 | 3.75 (2.67 to 4.83) | 9.1218e−09 | 2.89 (1.51 to 4.28) | 3.473e−05 |

| PAPP-A | 4148–49 | 2.38 (1.44 to 3.34) | 0.00021104 | 2.71 (1.46 to 3.99) | 2.1535e−05 |

| Prekallikrein | 4152–58 | −3.43 (−5.13 to −1.70) | 0.00747677 | −7.47 (−10.38 to −4.47) | 2.0524e−06 |

| Spondin-1 | 4297–62 | 3.44 (1.62 to 5.29) | 0.01022454 | 9.72 (6.90 to 12.62) | 4.1589e−12 |

| MIC-1 | 4374–45 | 2.56 (1.42 to 3.72) | 0.00137208 | 3.84 (2.55 to 5.15) | 4.1587e−09 |

| MMP-12 | 4496–60 | 2.24 (1.25 to 3.24) | 0.00132756 | 2.11 (1.04 to 3.18) | 0.0001021 |

| Lysozyme | 4920–10 | 2.34 (1.12 to 3.57) | 0.00902411 | 3.82 (2.24 to 5.42) | 1.7318e−06 |

| CAPG | 4968–50 | 1.87 (0.88 to 2.86) | 0.01030245 | 2.75 (1.36 to 4.16) | 9.9535e−05 |

| sICAM-5 | 5124–62 | 3.18 (1.77 to 4.62) | 0.00132756 | 6.78 (4.83 to 8.76) | 4.1388e−12 |

| sICAM-5 | 5124–69 | 2.79 (1.40 to 4.21) | 0.00569007 | 5.29 (3.66 to 6.95) | 1.303e−10 |

| FABP | 5437–63 | −2.94 (−4.11 to −1.75) | 0.00038657 | −3.35 (−4.79 to −1.88) | 1.0104e−05 |

| Spondin-1 | 5496–49 | 3.88 (1.91 to 5.89) | 0.0065124 | 8.77 (5.99 to 11.62) | 2.5089e−10 |

| TREM2 | 5635–66 | 1.96 (0.96 to 2.96) | 0.00714912 | 3.00 (1.67 to 4.36) | 8.9614e−06 |

| TMX3 | 5654–70 | 3.01 (1.46 to 4.59) | 0.00801151 | 4.86 (2.85 to 6.90) | 1.6714e−06 |

| Tenascin | 5675–6 | 1.79 (0.74 to 2.84) | 0.02441723 | 2.94 (1.65 to 4.25) | 6.854e−06 |

| CECR1 | 6077–63 | 2.12 (1.30 to 2.94) | 0.00011056 | 2.33 (1.19 to 3.49) | 6.0324e−05 |

| ELA1 | 6107–3 | 2.00 (0.75 to 3.26) | 0.0359327 | 2.60 (1.28 to 3.94) | 0.00010839 |

| QSCN6 | 6217–23 | 3.51 (1.37 to 5.70) | 0.03028889 | 10.34 (7.14 to 13.63) | 7.059e−11 |

| Secretoglobin family 3A member 1 | 6252–62 | 2.65 (1.88 to 3.42) | 1.5644e−08 | 2.87 (1.91 to 3.85) | 4.8217e−09 |

| Tenascin | 6260–14 | 2.37 (0.91 to 3.86) | 0.03257182 | 7.81 (5.70 to 9.95) | 1.2986e−13 |

| C1QT1 | 6304–8 | 4.20 (2.26 to 6.17) | 0.00196403 | 7.60 (4.45 to 10.83) | 1.39e−06 |

| FAIM3 | 6574–11 | 1.65 (0.74 to 2.58) | 0.01571336 | 2.69 (1.51 to 3.88) | 7.3708e−06 |

| F176C:CD | 7008–13 | 2.27 (0.89 to 3.66) | 0.02916174 | 3.63 (2.16 to 5.13) | 1.1517e−06 |

| Tenascin | 7131–207 | 2.16 (0.73 to 3.60) | 0.04965436 | 4.55 (2.79 to 6.34) | 3.038e−07 |

| Amyloid-like protein 1 | 7210–25 | −2.65 (−3.82 to −1.46) | 0.00183128 | −3.12 (−4.42 to −1.79) | 5.1654e−06 |

| ITI heavy chain H1 | 7955–195 | −4.18 (−6.16 to −2.17) | 0.00451628 | −8.19 (−11.19 to −5.08) | 5.3426e−07 |

| EPHB2 | 8225–86 | 2.87 (1.15 to 4.62) | 0.02791634 | 4.71 (2.47 to 6.99) | 3.2058e−05 |

| JAML1 | 8232–90 | 2.74 (1.62 to 3.86) | 0.00034816 | 3.82 (2.41 to 5.25) | 9.0507e−08 |

| sICAM-5 | 8245–27 | 3.19 (1.81 to 4.58) | 0.00090128 | 8.60 (6.65 to 10.58) | 1.046e−18 |

| TNF sR-II | 8368–102 | 2.29 (0.93 to 3.65) | 0.02521438 | 3.70 (1.84 to 5.60) | 8.7753e−05 |

| RSPO4 | 8464–31 | 2.32 (0.93 to 3.73) | 0.02803871 | 7.07 (4.69 to 9.50) | 3.1943e−09 |

| IGFBP-2 | 8469–41 | 1.74 (0.86 to 2.63) | 0.00693943 | 3.11 (1.89 to 4.33) | 4.627e−07 |

| Leptin | 8484–24 | −3.90 (−4.69 to −3.09) | 4.7716e−17 | −3.66 (−4.57 to −2.75) | 1.2512e−14 |

| IGFBP-2 | 8819–3 | 1.70 (0.86 to 2.56) | 0.00531558 | 3.02 (1.87 to 4.18) | 2.0183e−07 |

| sTREM-1 | 9266–1 | 4.58 (3.01 to 6.17) | 5.1876e−06 | 4.16 (2.50 to 5.85) | 7.5401e−07 |

| SDF-1 | 9278–9 | 5.32 (3.47 to 7.21) | 7.3726e−06 | 5.15 (2.92 to 7.43) | 4.9054e−06 |

| PTPRD | 9296–15 | −3.14 (−4.87 to −1.36) | 0.02033881 | −3.36 (−4.92 to −1.78) | 3.9093e−05 |

| MANS4 | 9578–263 | 1.71 (0.83 to 2.60) | 0.00813013 | 2.49 (1.24 to 3.75) | 8.45e−05 |

| L-plastin | 9749–190 | 4.69 (2.58 to 6.84) | 0.00137881 | 7.23 (4.48 to 10.06) | 1.5856e−07 |

| SYWC | 9870–17 | 3.40 (1.94 to 4.88) | 0.0007642 | 6.27 (4.21 to 8.37) | 1.4812e−09 |

Abbreviation: CI=confidence interval; FDR=false discovery rate; HAA=high attenuation area; MESA=Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; SPIROMICS=Subpopulations of Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study

Linear regression model adjusted for age, sex, smoking history, cigarette pack-years, height, weight, waist circumference, education attainment, income, principal components of genetic ancestry, lung volume imaged, percent emphysema, study center, batch, and scanner parameters (scanner model, radiation dose, and voxels). Estimated glomerular filtration rate adjusted for in MESA.

Results reported per 1-unit increment in log2-transformed protein level.

Bonferroni-adjusted p-value cutoff of 0.00011574.

We mapped HAA-associated proteins from Table 2 with their respective encoding gene using the Entrez identifier (E-Table 4). Pathway analysis of the HAA-associated proteins showed enrichment of immune cell and vascular adhesion-related processes (Figure 2B). Regulation of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade was also identified which regulates cellular processes related to apoptosis and proliferation.

Associations of HAA proteomic markers with fibrotic and subpleural ILA

We then examined whether the 75 validated HAA-associated proteins were associated with the probability of developing fibrotic or subpleural ILA in the MESA cohort. After excluding participants who had fibrotic or subpleural ILA at baseline and missing covariate data, there were 1,766 participants with Exam 1 SomaScan protein measurements and serial Exam 1 and Exam 5 ILA assessments (E-Figure 2). There were 102 individuals (5.8%) with new-onset fibrotic or subpleural ILA. Characteristics of this group are shown in E-Table 5. Descriptively, those MESA participants with repeat ILA assessment at Exam 5 were younger, had a higher proportion of women, and lower proportion of current smokers and below high school education than the overall cohort. Participants with new-onset fibrotic or subpleural ILA at Exam 5 were older at baseline, comprised of more smokers, and had a higher cigarette pack-year history than those participants without fibrotic-subpleural ILA. Of the proteins that were associated with HAA at baseline, seven of them were associated with a higher probability of developing fibrotic or subpleural ILA 10 years later at Exam 5 (E-Table 6). These proteins were human epididymis protein 4 (HE4), CUB domain-containing protein 1 (CDCP1), macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1), junctional adhesion molecule-like (JAML), GTP cyclohydrolase 1 feedback regulator (GCHFR), surfactant protein-B (SP-B), and tumor necrosis factor soluble receptor II (TNF sR-II). Stratified analysis by self-reported race and ethnicity showed the proteins had concordant direction of associations with Exam 5 fibrotic or subpleural ILA, except for the Asian subgroup (E-Table 7).

Longitudinal changes in proteomic biomarkers

We then examined whether changes in plasma levels over time of these seven HAA-associated proteins also correlated with the future development of fibrotic or subpleural ILA. In MESA, SomaScan protein measurements were available from Exam 1 (2000–2002) and Exam 5 (2010–2012) plasma samples. After excluding participants with baseline fibrotic or subpleural ILA, there were 1,731 with serial SomaScan measurements and ILA assessments at Exams 1 and 5, of whom 98 (5.7%) had new-onset subpleural or fibrotic ILA. Increased plasma levels in 5 of the 7 proteins were associated with new onset fibrotic or subpleural ILA (HE4, CDCP1, MIC-1, GCHFR, SP-B) (Table 3). Associations were linear for HE4, MIC-1, GCHFR, and SP-B (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Associations of changes in HAA-derived proteins with new-onset subpleural and fibrotic interstitial lung abnormalities

| Protein | Aptamer ID | Odds ratio for new-onset subpleural or fibrotic ILA per 1-unit increase in log-transformed protein level (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HE4 | 11388–75 | 1.31 (1.03–1.67) | 0.03 |

| CDCP1 | 16818–200 | 2.15 (1.16–4.00) | 0.02 |

| GCHFR | 21118–48 | 2.34 (1.38–3.96) | 0.002 |

| MIC-1 | 4374–45 | 1.75 (1.02–3.01) | 0.04 |

| JAML | 8232–90 | 2.11 (1.00–4.42) | 0.049 |

| SP-B | 10672–75 | 2.41 (1.61–3.61) | 1.92e−05 |

| TNF sR-II | 8368–102 | 1.81 (0.87–3.78) | 0.11 |

Logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex, smoking history, cigarette pack-years, height, weight, waist circumference, education attainment, income, estimated glomerular filtration rate, study center, batch, principal components of genetic ancestry, and baseline plasma protein level.

Results reported per 1-unit increase in log2-transformed protein level between Exam 1 (2000–2002) and Exam 5 (2010–2012).

Figure 3.

Plots of changes in plasma proteomic biomarkers between Exam 1 (2000–2002) and Exam 5 (2010–2012) and probability of Exam 5 fibrotic or subpleural interstitial lung abnormalities in MESA. Generalized additive models used to plot associations with adjustment for baseline age, sex, smoking history, cigarette pack-years, height, weight, waist circumference, glomerular filtration rate, education attainment, income, study site, principal components of genetic ancestry, and batch, and Exam 1 protein level. X-axis is the difference in log2-transformed protein levels between Exam 1 (2000–2002) and Exam 5 (2010–2012). One participant was removed from analysis due to outlier measurements in all six proteins.

JAML and GCHFR stain in IPF lung tissue

To our knowledge, there is a paucity of data whether JAML and GCHFR stains in fibrotic lung tissue. We obtained lung tissue samples from patients with IPF and performed immunohistochemical stains for JAML and GCHFR (online supplementary appendix). Tissue samples from patients without known pulmonary fibrosis who underwent surgical resection for nodules and emphysematous lungs were also stained for comparison (E-Table 8). Staining of control tissue is shown in E-Figure 3. Isotype antibody control staining of lung tissue for JAML and GCHFR is shown in E-Figure 4A-B. In IPF lung tissue, JAML stained most prominently in areas of fibrosis and particularly in early and late fibroblastic foci (Figure 4A-C). In tissue samples from non-IPF lungs and emphysema cases (E-Figure 4C-D), JAML stained in similar regions of the lung but less so, due to the absence of fibrosis. Compared with non-IPF lung and emphysema cases (E-Figure 4E-F), GCHFR stained more so in lymphocytes and alveolar macrophages in IPF lung tissue (Figure 4D-F). Overall, the staining of JAML and GCHFR was most prominent in areas of fibrosis in IPF and minimal staining in geographically heterogenic non-fibrotic lung tissue.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of JAML in IPF lung tissue at (A) 12x, (B) 40x, and (C) 400x magnification. GCHFR immunostaining of IPF lung tissue at (D) 12x, (E) 40x, and (F) 400x magnification.

DISCUSSION

We identified plasma proteins that were associated with high attenuation areas on CT lung images in two independent cohorts. Pathway analysis revealed biological processes involved in regulation of immune cells, vascular adhesion, cellular apoptosis and proliferation. Several HAA-associated proteins at baseline and their increase over time were associated with a higher probability of developing fibrotic or subpleural interstitial lung abnormalities and stained in IPF lung tissue.

HAA is a CT-based assessment of increased attenuation areas in lungs that can be prone to confounding effects of body habitus, artifacts, and abnormalities unrelated to ILD that can influence HAA. Thus, we aimed to identify plasma proteins that associate with HAA and therefore may reflect systemic biological processes that HAA of the lungs capture. Several of the HAA-associated proteins we identified also associate with ILA, QIA, and IPF survival, which include ICAM5, CDCP1, TREM1, MIC-1 (GDF15), and HE4 (WFDC2) and further supports their potential involvement in subclinical lung injury and fibrosis (14, 15, 33). We also identified other proteins unique to HAA and as we hypothesized, several of them are involved in immune cell and vascular processes and supports prior studies that have implicated these pathways in pulmonary fibrosis (34–39).

Several plasma proteins associated with lower HAA including leptin and growth hormone receptor, both of which are involved in adipogenesis and body habitus development. We expected a positive association with HAA and leptin due to possible confounding effects of adiposity on HAA. Furthermore, leptin binds to receptors in the lung and concentrations of leptin correlate between blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimens with preclinical experiments demonstrating conflicting roles of leptin in fibrogenesis (40–43). Further mechanistic work targeting these proteins will elucidate their therapeutic potential.

Due to interest in identifying individuals at-risk of developing future disease, we examined whether the HAA-associated proteins were associated with a higher probability of future ILD using fibrotic and subpleural ILA subtypes as radiologic surrogates. We were interested in those individuals without fibrosis and subpleural involvement on their baseline CT scans, because this subgroup may help with future trial enrichment to test preventative therapies. We found higher plasma levels of HE4, CDCP1, MIC-1, JAML, GCHFR, TNF sR-II, and SP-B were associated with new onset fibrotic or subpleural ILA. Likewise, associations of the proteins had concordant direction of associations in an analysis stratified by self-reported race and ethnicity, except for the Asian subgroup which may be due to the smaller sample size. Proteins were strongly associated with a higher probability of fibrotic or subpleural ILA in the self-reported African American and Black subgroup. This is notable in light of studies demonstrating key differences in clinical outcomes by self-reported race and ethnicity (30, 44, 45) and lack of identified common genetic variants related to ILD risk in underrepresented minority groups which would hinder enrollment in future precision medicine trials (2, 46). Our study demonstrates blood-based proteins may bypass inherent limitations of genomic studies that are not adequately powered to identify common variants in populations outside of non-Hispanic White of European ancestry. We did not have an independent diverse population of adults to replicate our findings for fibrotic and subpleural ILA. A major next step based on our findings and other work (14, 15) is to derive and validate prediction models that incorporate clinical, genomics, imaging, and proteomic biomarkers to predict the future development of ILD. Doing so will be critical for cohort enrichment for future trials that test preventative therapies, particularly in at-risk individuals like 1st-degree relatives of patients with pulmonary fibrosis (47). Also, this approach may identify at-risk individuals from whom pathobiological inferences can be made and identify molecular mechanisms that are unique to the early development of ILD and lead to therapeutic developments.

A novel component of our study was the availability of serial protein measurements in MESA. We found that increasing levels of several proteins including HE4, SP-B, GCHFR, CDCP1, MIC-1, and JAML were associated with a future probability of developing fibrotic or subpleural ILA. Our finding provides insight on the temporal relationship between these proteins and the spectrum of ILD and that higher levels may reflect disease progression. Furthermore, tools to identify and monitor progression of pulmonary fibrosis stages remains a significant barrier to designing clinical trials that test preventative therapies. Our findings suggest the plausibility of blood-based protein markers to complement other tools like imaging to assess disease progression for staging purposes and treatment responses in clinical trials. It remains uncertain which of the plasma proteins associates with short-term and long-term development of lung fibrosis. This is pertinent in light of recent studies that have shown some individuals will have more rapid radiologic progression of ILA in 3–5 years (48). More frequent blood sampling and serial imaging with progression assessments is a future research area.

We acknowledge that several of the identified proteins may not be specific to the early pathogenesis of ILD but rather systemic inflammatory and fibrosing processes that affect multiple organs. Of the seven HAA-associated proteins that correlated with new onset fibrotic-subpleural ILA, we determined whether JAML and GCHFR were expressed in IPF lung tissue because they had not been well-studied in IPF. JAML has been implicated in mucosal integrity and delays intestinal epithelial repair during acute inflammation and may have a similar role in the lung (49). A recent study demonstrated increased mRNA expression of JAML in fibrotic lung tissue (50). GCHFR stained heavily in alveolar macrophages and lymphocytes, thus suggesting an immunomodulatory function in IPF and has been implicated in IPF risk (51). Importantly, our immunohistochemical stains of IPF lungs show that JAML and GCHFR localize in and around areas of fibrotic lung. Follow-up studies that examine histopathological correlations with HAA and preclinical experiments that explore the function of these proteins in lung fibrosis will be informative.

A major limitation of our study and other semiquantitative proteomic work is the lack of full quantification using validated assays. Therefore, we could not confirm the direction of associations between the proteins and HAA nor concentration cutoff levels that demonstrate adequate performance characteristics at predicting future development of ILD. We did not have more frequent paired plasma samples with proteomic measurements and could not determine the incremental rate of change in the proteins that strongly associates with developing subsequent ILD. Also, while an advantage of aptamer-based proteomic platforms is the breadth of proteins in their panels which facilitates discovery, their specificity to the actual protein target is lower compared to other approaches (52). We performed a sensitivity analysis and found that 4 proteins measured by ELISA assays and previously associated with HAA in MESA correlated with the aptamer-based protein measurements in our study. None of the proteins were associated with HAA or replicated in SPIROMICS and may be due to differences in sample sizes and the fact that our study used semiquantitative plasma levels. Applying other semiquantitative proteomic platforms and full quantification with ELISA or mass spectrometry will be important for validation of our findings. Selection bias may have influenced our findings, particularly related to subsequent development of ILD on CT scan, which required serial blood samples and CT scans over a span of 10 years. Indeed, the prevalence of fibrotic or subpleural ILA of 5.8% on repeat CT scans in MESA may be higher than expected given prevalence estimates of ILDs are much lower (53). It is possible that some ILA cases may regress while others progress to other fibrotic ILD subtypes besides IPF and this is pertinent given recent studies that suggest shared genomic and histopathologic features across different ILD subtypes (54). Additionally, the MESA cohort was comprised of older adults at recruitment with a minimum age cutoff of 45 years, which may have influenced the prevalence estimates. Conversely, given that ILD remains underrecognized and contributes to significant morbidity and mortality (55, 56), we cannot completely rule out there were MESA participants who developed ILD but did not participate in follow-up visits or had died without ILD adjudication. Thus, this may have biased our results towards the null. More prospective cohorts with serial imaging and omics data and ILD event adjudication will be informative. We acknowledge the SPIROMICS cohort was comprised of individuals with a much stronger smoking history than MESA and may have affected our findings. However, we still detected 75 proteins that replicated across the two cohorts and suggest generalizability of our findings in both older adults and those with a significant smoking history. Similar to prior studies, our findings support the notion that there are molecular markers that correlate with early lung inflammation and scarring that is not entirely explained by smoking exposure. Another future research area is to derive and validate blood-based protein biomarkers that predict development of clinically diagnosed ILD. This requires independent cohorts with many years of follow-up data and adjudication of an ILD diagnosis that is harmonized to proteomic and clinical data. Imaging and lung physiologic surrogates for ILD that complement physician-adjudicated and coded diagnoses is an ongoing area of investigation that could be helpful. Moreso, our study supports the possibility of generating integrative multi-omics prediction models for new-onset lung fibrosis which may help with cohort enrichment for trials that test therapies aimed at preventing lung fibrosis. We did not replicate our longitudinal analyses in independent cohorts and this highlights ongoing needs for collaboration and data harmonization.

In closing, plasma proteins involved in immune and cellular processes were associated with HAA on lung CT and new-onset lung fibrosis on CT scan. Further validation and full quantification are needed of these proteins for future implementation to identify individuals at risk for lung fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

This article has an online data supplement, which is accessible at the Supplements tab.

At a Glance Commentary.

Current Scientific Knowledge on the Subject:

More high attenuation areas (HAA) on lung scans may indicate inflammation and fibrosis but their systemic molecular correlates are unknown.

What This Study Adds to the Field:

Several plasma proteins correlated with more HAA on lung scans and a subset of them were associated with new-onset fibrotic or subpleural interstitial lung abnormalities on subsequent scans. Integration of imaging and omics may help identify adults at risk of developing pulmonary fibrosis.

Funding:

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Lung Study was supported by grants R01-HL077612, R01-HL093081, and RC1-HL100543 from the National Heart Lung Blood Institute (NHLBI). MESA Lung Fibrosis was supported by R01-HL103676 from NHLBI. The MESA projects are conducted and supported by the NHLBI in collaboration with MESA investigators. Work supported by R01-HL159081 from NHLBI. The MESA projects are conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with MESA investigators. Support for the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) projects are conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with MESA investigators. Support for MESA is provided by contracts 75N92020D00001, HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, 75N92020D00005, N01-HC-95160, 75N92020D00002, N01-HC-95161, 75N92020D00003, N01-HC-95162, 75N92020D00006, N01-HC-95163, 75N92020D00004, N01-HC-95164, 75N92020D00007, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, N01-HC-95169, UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, UL1-TR-001420, UL1-TR001881, DK063491, and R01-HL105756. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutes can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org. SPIROMICS (Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study) was supported by NHLBI grants R01-HL137880 and NHLBI contracts HHSN268200900013C, HHSN268200900014C, HHSN268200900015C, HHSN268200900016C, HHSN268200900017C, HHSN268200900018C, HHSN268200900019C, and HSN268200900020C, which were supplemented by contributions made through the Foundation for the NIH from AstraZeneca; Bellerophon Therapeutics; Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Chiesi Farmaceutici SpA; Forest Research Institute, Inc; GSK; Grifols Therapeutics, Inc; Ikaria, Inc; Nycomed GmbH; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; and Sanofi. JSK was supported by the grant K23-HL-150301 from the NHLBI. JMW was supported by the grants F32HL175973 and T32HL007749 from the NHLBI. RTH was supported by the grant F32HL170760 from the NHLBI.

This work was supported by the Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (BTRF) and the Leica THUNDER TIRF in the Advanced Microscopy Facility which are supported by the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Research Resource Identifiers (RRIDs): SCR_022971, SCR_018736. We gratefully acknowledge the studies and participants who provided biological samples and data for MESA and SPIROMICS.

Footnotes

Artificial Intelligence Disclaimer: No artificial intelligence tools were used in writing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lederer DJ, Martinez FJ. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1811–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JS, Montesi SB, Adegunsoye A, Humphries SM, Salisbury ML, Hariri LP, Kropski JA, Richeldi L, Wells AU, Walsh S, Jenkins RG, Rosas I, Noth I, Hunninghake GM, Martinez FJ, Podolanczuk AJ. Approach to Clinical Trials for the Prevention of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2023; 20: 1683–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunninghake GM. Interstitial lung abnormalities: erecting fences in the path towards advanced pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 2019; 74: 506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose JA, Planchart Ferretto MA, Maeda AH, Perez Garcia MF, Carmichael NE, Gulati S, Rice MB, Goldberg HJ, Putman RK, Hatabu H, Raby BA, Rosas IO, Hunninghake GM. Progressive Interstitial Lung Disease in Relatives of Patients with Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023; 207: 211–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunninghake GM, Goldin JG, Kadoch MA, Kropski JA, Rosas IO, Wells AU, Yadav R, Lazarus HM, Abtin FG, Corte TJ, de Andrade JA, Johannson KA, Kolb MR, Lynch DA, Oldham JM, Spagnolo P, Strek ME, Tomassetti S, Washko GR, White ES, Group ILAS. Detection and Early Referral of Patients With Interstitial Lung Abnormalities: An Expert Survey Initiative. Chest 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunninghake GM, Hatabu H, Okajima Y, Gao W, Dupuis J, Latourelle JC, Nishino M, Araki T, Zazueta OE, Kurugol S, Ross JC, San Jose Estepar R, Murphy E, Steele MP, Loyd JE, Schwarz MI, Fingerlin TE, Rosas IO, Washko GR, O’Connor GT, Schwartz DA. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2192–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Putman RK, Hatabu H, Araki T, Gudmundsson G, Gao W, Nishino M, Okajima Y, Dupuis J, Latourelle JC, Cho MH, El-Chemaly S, Coxson HO, Celli BR, Fernandez IE, Zazueta OE, Ross JC, Harmouche R, Estepar RS, Diaz AA, Sigurdsson S, Gudmundsson EF, Eiriksdottir G, Aspelund T, Budoff MJ, Kinney GL, Hokanson JE, Williams MC, Murchison JT, MacNee W, Hoffmann U, O’Donnell CJ, Launer LJ, Harrris TB, Gudnason V, Silverman EK, O’Connor GT, Washko GR, Rosas IO, Hunninghake GM, Evaluation of CLtIPSEI, Investigators CO. Association Between Interstitial Lung Abnormalities and All-Cause Mortality. JAMA 2016; 315: 672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salisbury ML, Hewlett JC, Ding G, Markin CR, Douglas K, Mason W, Guttentag A, Phillips JA 3rd, Cogan JD, Reiss S, Mitchell DB, Wu P, Young LR, Lancaster LH, Loyd JE, Humphries SM, Lynch DA, Kropski JA, Blackwell TS. Development and Progression of Radiologic Abnormalities in Individuals at Risk for Familial Interstitial Lung Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: 1230–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatabu H, Hunninghake GM, Richeldi L, Brown KK, Wells AU, Remy-Jardin M, Verschakelen J, Nicholson AG, Beasley MB, Christiani DC, San Jose Estepar R, Seo JB, Johkoh T, Sverzellati N, Ryerson CJ, Graham Barr R, Goo JM, Austin JHM, Powell CA, Lee KS, Inoue Y, Lynch DA. Interstitial lung abnormalities detected incidentally on CT: a Position Paper from the Fleischner Society. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 726–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X, Kim GH, Salisbury ML, Barber D, Bartholmai BJ, Brown KK, Conoscenti CS, De Backer J, Flaherty KR, Gruden JF, Hoffman EA, Humphries SM, Jacob J, Maher TM, Raghu G, Richeldi L, Ross BD, Schlenker-Herceg R, Sverzellati N, Wells AU, Martinez FJ, Lynch DA, Goldin J, Walsh SLF. Computed Tomographic Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. The Future of Quantitative Analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JS, Manichaikul AW, Hoffman EA, Balte P, Anderson MR, Bernstein EJ, Madahar P, Oelsner EC, Kawut SM, Wysoczanski A, Laine AF, Adegunsoye A, Ma JZ, Taub MA, Mathias RA, Rich SS, Rotter JI, Noth I, Garcia CK, Barr RG, Podolanczuk AJ. MUC5B, telomere length and longitudinal quantitative interstitial lung changes: the MESA Lung Study. Thorax 2023; 78: 566–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Podolanczuk AJ, Oelsner EC, Barr RG, Bernstein EJ, Hoffman EA, Easthausen IJ, Stukovsky KH, RoyChoudhury A, Michos ED, Raghu G, Kawut SM, Lederer DJ. High-Attenuation Areas on Chest Computed Tomography and Clinical Respiratory Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196: 1434–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Podolanczuk AJ, Oelsner EC, Barr RG, Hoffman EA, Armstrong HF, Austin JH, Basner RC, Bartels MN, Christie JD, Enright PL, Gochuico BR, Hinckley Stukovsky K, Kaufman JD, Hrudaya Nath P, Newell JD Jr., Palmer SM, Rabinowitz D, Raghu G, Sell JL, Sieren J, Sonavane SK, Tracy RP, Watts JR, Williams K, Kawut SM, Lederer DJ. High attenuation areas on chest computed tomography in community-dwelling adults: the MESA study. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 1442–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Axelsson GT, Gudmundsson G, Pratte KA, Aspelund T, Putman RK, Sanders JL, Gudmundsson EF, Hatabu H, Gudmundsdottir V, Gudjonsson A, Hino T, Hida T, Hobbs BD, Cho MH, Silverman EK, Bowler RP, Launer LJ, Jennings LL, Hunninghake GM, Emilsson V, Gudnason V. The Proteomic Profile of Interstitial Lung Abnormalities. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi B, Liu GY, Sheng Q, Amancherla K, Perry A, Huang X, San Jose Estepar R, Ash SY, Guan W, Jacobs DR Jr., Martinez FJ, Rosas IO, Bowler RP, Kropski JA, Banovich NE, Khan SS, San Jose Estepar R, Shah R, Thyagarajan B, Kalhan R, Washko GR. Proteomic Biomarkers of Quantitative Interstitial Abnormalities in COPDGene and CARDIA Lung Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024; 209: 1091–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maddali MV, Kim JS, Oldham JM. Mapping the Proteomic Landscape of Radiological Lung Abnormalities. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024; 209: 1052–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR Jr., Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Couper D, LaVange LM, Han M, Barr RG, Bleecker E, Hoffman EA, Kanner R, Kleerup E, Martinez FJ, Woodruff PG, Rennard S, Group SR. Design of the Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcomes in COPD Study (SPIROMICS). Thorax 2014; 69: 491–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Stidley CA, Colby TV, Waldron JA. Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155: 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold L, Walker JJ, Wilcox SK, Williams S. Advances in human proteomics at high scale with the SOMAscan proteomics platform. N Biotechnol 2012; 29: 543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gold L, Ayers D, Bertino J, Bock C, Bock A, Brody EN, Carter J, Dalby AB, Eaton BE, Fitzwater T, Flather D, Forbes A, Foreman T, Fowler C, Gawande B, Goss M, Gunn M, Gupta S, Halladay D, Heil J, Heilig J, Hicke B, Husar G, Janjic N, Jarvis T, Jennings S, Katilius E, Keeney TR, Kim N, Koch TH, Kraemer S, Kroiss L, Le N, Levine D, Lindsey W, Lollo B, Mayfield W, Mehan M, Mehler R, Nelson SK, Nelson M, Nieuwlandt D, Nikrad M, Ochsner U, Ostroff RM, Otis M, Parker T, Pietrasiewicz S, Resnicow DI, Rohloff J, Sanders G, Sattin S, Schneider D, Singer B, Stanton M, Sterkel A, Stewart A, Stratford S, Vaught JD, Vrkljan M, Walker JJ, Watrobka M, Waugh S, Weiss A, Wilcox SK, Wolfson A, Wolk SK, Zhang C, Zichi D. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS One 2010; 5: e15004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Candia J, Daya GN, Tanaka T, Ferrucci L, Walker KA. Assessment of variability in the plasma 7k SomaScan proteomics assay. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 17147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubin RF, Deo R, Ren Y, Lee H, Shou H, Feldman H, Kimmel P, Waikar SS, Rhee EP, Tin A, Chen J, Coresh J, Go AS, Kelly T, Rao PS, Chen TK, Segal MR, Ganz P. Analytical and Biological Variability of a Commercial Modified Aptamer Assay in Plasma Samples of Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. J Appl Lab Med 2023; 8: 491–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sieren JP, Newell JD Jr., Barr RG, Bleecker ER, Burnette N, Carretta EE, Couper D, Goldin J, Guo J, Han MK, Hansel NN, Kanner RE, Kazerooni EA, Martinez FJ, Rennard S, Woodruff PG, Hoffman EA, Group SR. SPIROMICS Protocol for Multicenter Quantitative Computed Tomography to Phenotype the Lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 794–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman EA, Reinhardt JM, Sonka M, Simon BA, Guo J, Saba O, Chon D, Samrah S, Shikata H, Tschirren J, Palagyi K, Beck KC, McLennan G. Characterization of the interstitial lung diseases via density-based and texture-based analysis of computed tomography images of lung structure and function. Acad Radiol 2003; 10: 1104–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGroder CF, Hansen S, Hinckley Stukovsky K, Zhang D, Nath PH, Salvatore MM, Sonavane SK, Terry N, Stowell JT, D’Souza BM, Leb JS, Dumeer S, Aziz MU, Batra K, Hoffman EA, Bernstein EJ, Kim JS, Podolanczuk AJ, Rotter JI, Manichaikul AW, Rich SS, Lederer DJ, Barr RG, McClelland RL, Garcia CK. Incidence of Interstitial Lung Abnormalities: The MESA Lung Study. Eur Respir J 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012; 16: 284–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Putman RK, Gudmundsson G, Axelsson GT, Hida T, Honda O, Araki T, Yanagawa M, Nishino M, Miller ER, Eiriksdottir G, Gudmundsson EF, Tomiyama N, Honda H, Rosas IO, Washko GR, Cho MH, Schwartz DA, Gudnason V, Hatabu H, Hunninghake GM. Imaging Patterns Are Associated with Interstitial Lung Abnormality Progression and Mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200: 175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Putman RK, Gudmundsson G, Araki T, Nishino M, Sigurdsson S, Gudmundsson EF, Eiriksdottir G, Aspelund T, Ross JC, San Jose Estepar R, Miller ER, Yamada Y, Yanagawa M, Tomiyama N, Launer LJ, Harris TB, El-Chemaly S, Raby BA, Cho MH, Rosas IO, Washko GR, Schwartz DA, Silverman EK, Gudnason V, Hatabu H, Hunninghake GM. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism is associated with specific interstitial lung abnormality subtypes. Eur Respir J 2017; 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adegunsoye A, Freiheit E, White EN, Kaul B, Newton CA, Oldham JM, Lee CT, Chung J, Garcia N, Ghodrati S, Vij R, Jablonski R, Flaherty KR, Wolters PJ, Garcia CK, Strek ME. Evaluation of Pulmonary Fibrosis Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity in US Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6: e232427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong HF, Podolanczuk AJ, Barr RG, Oelsner EC, Kawut SM, Hoffman EA, Tracy R, Kaminski N, McClelland RL, Lederer DJ. Serum Matrix Metalloproteinase-7, Respiratory Symptoms, and Mortality in Community-Dwelling Adults. MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196: 1311–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madahar P, Duprez DA, Podolanczuk AJ, Bernstein EJ, Kawut SM, Raghu G, Barr RG, Gross MD, Jacobs DR Jr., Lederer DJ. Collagen biomarkers and subclinical interstitial lung disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Respir Med 2018; 140: 108114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oldham JM, Huang Y, Bose S, Ma SF, Kim JS, Schwab A, Ting C, Mou K, Lee CT, Adegunsoye A, Ghodrati S, Pugashetti JV, Nazemi N, Strek ME, Linderholm AL, Chen CH, Murray S, Zemans RL, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, Noth I. Proteomic Biomarkers of Survival in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024; 209: 1111–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JS, Anderson MR, Bernstein EJ, Oelsner EC, Raghu G, Noth I, Tsai MY, Salvatore M, Austin JHM, Hoffman EA, Barr RG, Podolanczuk AJ. Associations of D-Dimer with Computed Tomographic Lung Abnormalities, Serum Biomarkers of Lung Injury, and Forced Vital Capacity: MESA Lung Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18: 1839–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGroder CF, Aaron CP, Bielinski SJ, Kawut SM, Tracy RP, Raghu G, Barr RG, Lederer DJ, Podolanczuk AJ. Circulating adhesion molecules and subclinical interstitial lung disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Respir J 2019; 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JS, Axelsson GT, Moll M, Anderson MR, Bernstein EJ, Putman RK, Hida T, Hatabu H, Hoffman EA, Raghu G, Kawut SM, Doyle MF, Tracy R, Launer LJ, Manichaikul A, Rich SS, Lederer DJ, Gudnason V, Hobbs BD, Cho MH, Hunninghake GM, Garcia CK, Gudmundsson G, Barr RG, Podolanczuk AJ. Associations of Monocyte Count and Other Immune Cell Types with Interstitial Lung Abnormalities. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205: 795–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Probst CK, Montesi SB, Medoff BD, Shea BS, Knipe RS. Vascular permeability in the fibrotic lung. Eur Respir J 2020; 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Misharin AV, Morales-Nebreda L, Reyfman PA, Cuda CM, Walter JM, McQuattie-Pimentel AC, Chen CI, Anekalla KR, Joshi N, Williams KJN, Abdala-Valencia H, Yacoub TJ, Chi M, Chiu S, Gonzalez-Gonzalez FJ, Gates K, Lam AP, Nicholson TT, Homan PJ, Soberanes S, Dominguez S, Morgan VK, Saber R, Shaffer A, Hinchcliff M, Marshall SA, Bharat A, Berdnikovs S, Bhorade SM, Bartom ET, Morimoto RI, Balch WE, Sznajder JI, Chandel NS, Mutlu GM, Jain M, Gottardi CJ, Singer BD, Ridge KM, Bagheri N, Shilatifard A, Budinger GRS, Perlman H. Monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages drive lung fibrosis and persist in the lung over the life span. J Exp Med 2017; 214: 2387–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott MKD, Quinn K, Li Q, Carroll R, Warsinske H, Vallania F, Chen S, Carns MA, Aren K, Sun J, Koloms K, Lee J, Baral J, Kropski J, Zhao H, Herzog E, Martinez FJ, Moore BB, Hinchcliff M, Denny J, Kaminski N, Herazo-Maya JD, Shah NH, Khatri P. Increased monocyte count as a cellular biomarker for poor outcomes in fibrotic diseases: a retrospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7: 497–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Li Y, Liang J, Sun Z, Wu Q, Liu Y, Sun C. Leptin: an entry point for the treatment of peripheral tissue fibrosis and related diseases. Int Immunopharmacol 2022; 106: 108608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enomoto N, Oyama Y, Yasui H, Karayama M, Hozumi H, Suzuki Y, Kono M, Furuhashi K, Fujisawa T, Inui N, Nakamura Y, Suda T. Analysis of serum adiponectin and leptin in patients with acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 10484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gui X, Chen H, Cai H, Sun L, Gu L. Leptin promotes pulmonary fibrosis development by inhibiting autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018; 498: 660–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao M, Swigris JJ, Wang X, Cao M, Qiu Y, Huang M, Xiao Y, Cai H. Plasma Leptin Is Elevated in Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Mediators Inflamm 2016; 2016: 6940480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lederer DJ, Arcasoy SM, Barr RG, Wilt JS, Bagiella E, D’Ovidio F, Sonett JR, Kawut SM. Racial and ethnic disparities in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A UNOS/OPTN database analysis. Am J Transplant 2006; 6: 2436–2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Bellam SK, Chung JH, Chung PA, Biblowitz KM, Montner S, Lee C, Hsu S, Husain AN, Vij R, Mutlu G, Noth I, Churpek MM, Strek ME. African-American race and mortality in interstitial lung disease: a multicentre propensity-matched analysis. Eur Respir J 2018; 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Podolanczuk AJ, Kim JS, Cooper CB, Lasky JA, Murray S, Oldham JM, Raghu G, Flaherty KR, Spino C, Noth I, Martinez FJ, Team PS. Design and rationale for the prospective treatment efficacy in IPF using genotype for NAC selection (PRECISIONS) clinical trial. BMC Pulm Med 2022; 22: 475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose JA, Steele MP, Kosak Lopez EJ, Axelsson GT, Galecio Chao AG, Waich A, Regan K, Gulati S, Maeda AH, Sultana S, Cutting C, Tukpah AC, Synn AJ, Rice MB, Goldberg HJ, Lee JS, Lynch DA, Putman RK, Hatabu H, Raby BA, Schwartz DA, Rosas IO, Hunninghake GM. Protein biomarkers of interstitial lung abnormalities in relatives of patients with pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2025; 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park S, Choe J, Hwang HJ, Noh HN, Jung YJ, Lee JB, Do KH, Chae EJ, Seo JB. Long-Term Follow-Up of Interstitial Lung Abnormality: Implication in Follow-Up Strategy and Risk Thresholds. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023; 208: 858–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weber DA, Sumagin R, McCall IC, Leoni G, Neumann PA, Andargachew R, Brazil JC, Medina-Contreras O, Denning TL, Nusrat A, Parkos CA. Neutrophil-derived JAML inhibits repair of intestinal epithelial injury during acute inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 2014; 7: 1221–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Natri HM, Del Azodi CB, Peter L, Taylor CJ, Chugh S, Kendle R, Chung MI, Flaherty DK, Matlock BK, Calvi CL, Blackwell TS, Ware LB, Bacchetta M, Walia R, Shaver CM, Kropski JA, McCarthy DJ, Banovich NE. Cell-type-specific and disease-associated expression quantitative trait loci in the human lung. Nat Genet 2024; 56: 595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gong W, Guo P, Liu L, Guan Q, Yuan Z. Integrative Analysis of Transcriptome-Wide Association Study and mRNA Expression Profiles Identifies Candidate Genes Associated With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front Genet 2020; 11: 604324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katz DH, Robbins JM, Deng S, Tahir UA, Bick AG, Pampana A, Yu Z, Ngo D, Benson MD, Chen ZZ, Cruz DE, Shen D, Gao Y, Bouchard C, Sarzynski MA, Correa A, Natarajan P, Wilson JG, Gerszten RE. Proteomic profiling platforms head to head: Leveraging genetics and clinical traits to compare aptamer- and antibody-based methods. Sci Adv 2022; 8: eabm5164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeganathan N, Sathananthan M. The prevalence and burden of interstitial lung diseases in the USA. ERJ Open Res 2022; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ley B, Newton CA, Arnould I, Elicker BM, Henry TS, Vittinghoff E, Golden JA, Jones KD, Batra K, Torrealba J, Garcia CK, Wolters PJ. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism and telomere length in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an observational cohort-control study. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 639–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, Morozoff C, Shirude S, Naghavi M, Mokdad AH, Murray CJL. Trends and Patterns of Differences in Chronic Respiratory Disease Mortality Among US Counties, 1980–2014. JAMA 2017; 318: 1136–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392: 1789–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.