Abstract

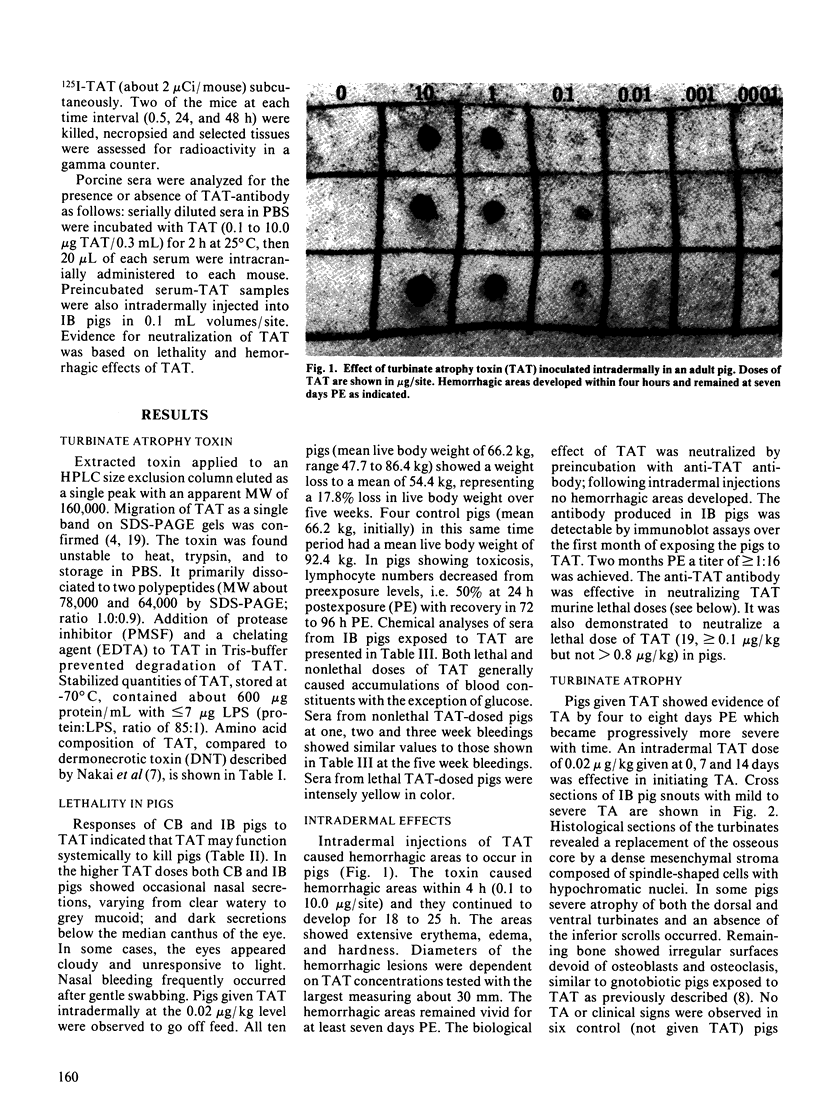

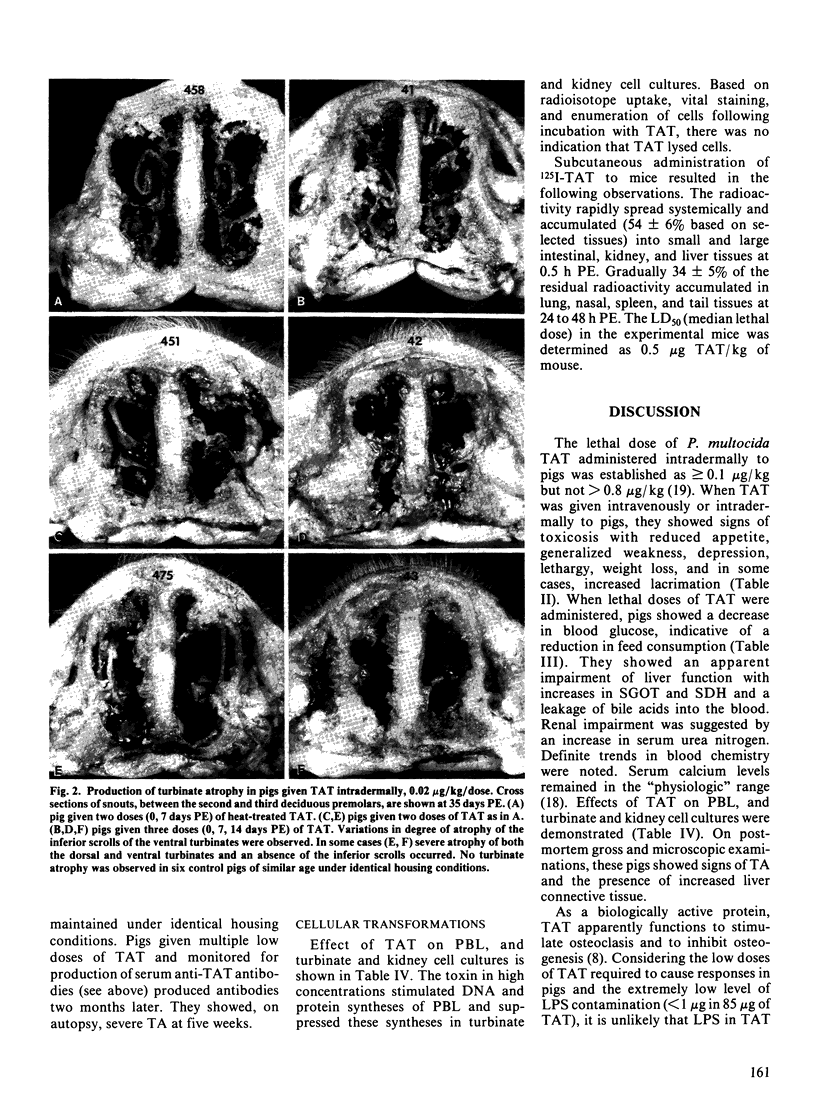

A porcine strain of Pasteurella multocida (serotype D:3) produced a toxin causing turbinate atrophy (TA) in pigs. The toxin (TAT), processed on a high performance liquid chromatography size exclusion column, eluted as a single peak (molecular weight of about 160,000) containing trace amounts of endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS; protein:LPS, 85:1). The eluted fraction migrated on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels as a single band. It could be prevented from dissociating into two prominent polypeptides by addition of a protease inhibitor. A single dose (2.0 to 79.0 micrograms/kg) of TAT given to pigs intravenously was lethal. Doses from 0.02 to 1.0 microgram/kg caused transient clinical signs of porcine systemic toxicosis with reduced appetite, generalized weakness, depression, lethargy, weight loss, and in some instances, death. Intradermal doses of TAT (greater than or equal to 0.1 microgram/site) produced hemorrhagic areas within four hours. Systemically, TAT causes bilateral TA, lymphopenia, liver dysfunctions, and possible renal impairment. Affinity of TAT for cells of epithelial origin was demonstrated in mice given 125I-TAT. In vitro, TAT stimulated DNA and protein syntheses of peripheral blood lymphocytes and suppressed syntheses in turbinate and kidney cell cultures without being cytolytic. Biological effects of TAT were eliminated by exposure to either heat, trypsin or anti-TAT antibody.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bennett F. C., Yeoman L. C. An improved procedure for the 'dot immunobinding' analysis of hybridoma supernatants. J Immunol Methods. 1983 Jul 15;61(2):201–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuyan B. K., Loughman B. E., Fraser T. J., Day K. J. Comparison of different methods of determining cell viability after exposure to cytotoxic compounds. Exp Cell Res. 1976 Feb;97(2):275–280. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominick M. A., Rimler R. B. Turbinate atrophy in gnotobiotic pigs intranasally inoculated with protein toxin isolated from type D Pasteurella multocida. Am J Vet Res. 1986 Jul;47(7):1532–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraker P. J., Speck J. C., Jr Protein and cell membrane iodinations with a sparingly soluble chloroamide, 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3a,6a-diphrenylglycoluril. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978 Feb 28;80(4):849–857. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gois M., Barnes H. J., Ross R. F. Potentiation of turbinate atrophy in pigs by long-term nasal colonization with Pasteurella multocida. Am J Vet Res. 1983 Mar;44(3):372–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin R., Dzenis L., Byrne J. L. Rhinitis of Swine. VII. Production of Lesions in Pigs and Rabbits with a Pure Culture of Pasteurella Multocida. Can J Comp Med Vet Sci. 1953 May;17(5):215–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartree E. F. Determination of protein: a modification of the Lowry method that gives a linear photometric response. Anal Biochem. 1972 Aug;48(2):422–427. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume K., Nakai T. Dissociation of Pasteurella multocida dermonecrotic toxin into three polypeptide fragments. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. 1985 Oct;47(5):829–833. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.47.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai T., Sawata A., Tsuji M., Samejima Y., Kume K. Purification of dermonecrotic toxin from a sonic extract of Pasteurella multocida SP-72 serotype D. Infect Immun. 1984 Nov;46(2):429–434. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.429-434.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K. B., Barfod K. Effect on the incidence of atrophic rhinitis of vaccination of sows with a vaccine containing Pasteurella multocida toxin. Nord Vet Med. 1982 Jul-Sep;34(7-9):293–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimler R. B., Brogden K. A. Pasteurella multocida isolated from rabbits and swine: serologic types and toxin production. Am J Vet Res. 1986 Apr;47(4):730–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimler R. B. Comparisons of serologic responses of white Leghorn and New Hampshire red chickens to purified lipopolysaccharides of Pasteurella multocida. Avian Dis. 1984 Oct-Dec;28(4):984–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimler R. B., Rebers P. A., Phillips M. Lipopolysaccharides of the Heddleston serotypes of Pasteurella multocida. Am J Vet Res. 1984 Apr;45(4):759–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter J. M., Mackenzie A. Pathogenesis of atrophic rhinitis in pigs: a new perspective. Vet Rec. 1984 Jan 28;114(4):89–90. doi: 10.1136/vr.114.4.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter J. M. Virulence of Pasteurella multocida in atrophic rhinitis of gnotobiotic pigs infected with Bordetella bronchiseptica. Res Vet Sci. 1983 May;34(3):287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawata A., Nakai T., Tuji M., Kume K. Dermonecrotic activity of Pasteurella multocida strains isolated from pigs in Japanese field. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. 1984 Apr;46(2):141–148. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.46.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]