Abstract

Influenza haemagglutinin (HA) is responsible for fusing viral and endosomal membranes during virus entry. In this process, conformational changes in the HA relocate the HA2 N-terminal ‘fusion peptide’ to interact with the target membrane. The highly conserved HA fusion peptide shares composition and sequence features with functionally analogous regions of other viral fusion proteins, including the presence and distribution of glycines and large side-chain hydrophobic residues. HAs with mutations in the fusion peptide were expressed using vaccinia virus recombinants to examine the requirement for fusion of specific hydrophobic residues and the significance of glycine spacing. Mutant HAs were also incorporated into infectious influenza viruses for analysis of their effects on infectivity and replication. In most cases alanine, but not glycine substitutions for the large hydrophobic residues, yielded fusion-competent HAs and infectious viruses, suggesting that the conserved spacing of glycines may be structurally significant. When viruses containing alanine substitutions for large hydrophobic residues were passaged, pseudoreversion to valine was observed, indicating a preference for large hydrophobic residues at specific positions. Viruses were also obtained with serine, leucine or phenylalanine as the N-terminal residue, but these replicated to significantly lower levels than wild-type virus with glycine at this position.

Keywords: fusion/hemagglutinin/influenza/reverse genetics

Introduction

Infection by enveloped viruses is initiated by binding to components of the host cell surface followed by fusion of the viral and cellular membranes. For influenza virus both of these functions are provided by the haemagglutinin glycoprotein (HA). HA initiates infection by binding to sialic acid containing cell surface glycoconjugates and, following endocytosis, it mediates fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes (Skehel and Wiley, 2000). HA is a homotrimer composed of monomers which are each synthesized as a single polypeptide, HA0, and subsequently cleaved into the disulfide-linked polypeptides, HA1 and HA2. Virus infectivity is dependent on this cleavage process (Klenk et al., 1975; Lazarowitz and Choppin, 1975) as it activates the membrane fusion potential of the glycoprotein. The N-terminus of the HA2 polypeptide generated upon cleavage is highly conserved and hydrophobic (Skehel and Waterfield, 1975) and is a critical component of the fusion process. It is referred to as the fusion peptide, and in the structure of cleaved HA the fusion peptides are buried in the interior of the trimer (Wilson et al., 1981). Following internalization of virus particles, endosomal acidification induces conformational changes in HA that are required for membrane fusion (Skehel et al., 1982; Bullough et al., 1994; Bizebard et al., 1995); prominent among these is extrusion of the fusion peptides from their buried positions.

Three major structural rearrangements occur at the pH of fusion. The membrane-distal receptor binding domains retain their structure but are de-trimerized; a central trimeric coiled-coil is elongated by converting an extended chain, which connects it in the neutral pH conformation to a short α-helix, into α-helix and the recruitment of the short α-helix to form the N-terminal section of the coiled-coil; and at the C-terminus of the coiled-coil, six residues of the native central α-helix refold to form a turn that results in the re-orientation of residues C-terminal to this by 180° (Bullough et al., 1994; Bizebard et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1999). Overall, these changes in HA2 place the C-terminal membrane anchor at the same end of a long rod-shaped molecule as the N-terminal fusion peptide and suggest a mechanism by which the hydrophobic membrane anchor and the hydrophobic fusion peptide bring the viral and endosomal membranes into close proximity to initiate fusion. Similar rod-like α-helical structures with membrane-associated domains at the same end have now been observed for the fusion proteins of several retroviruses (Fass et al., 1996; Weissenhorn et al., 1997; Caffrey et al., 1998), paramyxoviruses (Baker et al., 1999; Calder et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2000), Ebola virus (Weissenhorn et al., 1998; Malashkevich et al., 1999), and for cellular SNARE protein complexes involved in vesicle fusion (Sutton et al., 1998). A number of diverse fusion proteins may, therefore, have evolved a common mechanism for bringing membranes into close apposition in an early stage of the fusion process (Skehel and Wiley, 1998). How fusion proceeds, and the structural requirements of the membrane-associating domains for fusion activity, have not been resolved.

In this study we attempt to ascertain the significance for fusion of particular amino acids at specific positions in the fusion peptide. Amongst the representatives of the 15 antigenic subtypes of HA sequenced to date, the first 11 HA2 N-terminal residues (GLFGAIAGFIE) are completely conserved, as are seven of the next 12 amino acids (Nobusawa et al., 1991). Most of these are also conserved in influenza B virus HAs (Krystal et al., 1983). The most striking features of the fusion peptide are its hydrophobicity, the number of large side-chain, hydrophobic amino acids (10 of 23 in H3 HA) and the presence and distribution of glycine residues (seven of 23), interspersed similarly in the fusion peptide sequences of numerous unrelated virus fusion glycoproteins (reviewed in White, 1990).

Previous studies using site-specific mutagenesis and synthetic fusion peptide analogues have addressed the fusogenic properties of a number of mutants with changes in the fusion peptide (Gething et al., 1986; Wharton et al., 1988; Walker and Kawaoka, 1993; Steinhauer et al., 1995; Qiao et al., 1999). Much of this work focused on the first three glycine residues, and in particular the glycine at the N-terminus. These studies showed that all mutant HAs that could be cleaved into HA1 and HA2 were capable of undergoing the characteristic acid-induced changes in structure required for membrane fusion, but several were unable to cause fusion. This suggests that the structure of the fusion peptide at fusion pH and/or the manner in which it interacts with membranes is critical for its function. Here we attempt to probe the requirements for fusion of specific hydrophobic residues, and examine the significance of the spacing of glycine residues within the first 10 positions of HA2. We have made a series of mutant HAs with alanine or glycine substitutions for large hydrophobic residues at positions 2, 3, 6, 9 and 10, or alternative substitutions for glycine at position 1, and analysed their antigenic, biochemical and functional properties following expression in vaccinia recombinant-infected cells. We have also used reverse genetics to compare the observations made with expressed HAs with the infectivity of viruses containing HAs with the same mutations.

Results

Cell surface expression and cleavage of mutant precursor HAs

The mutations shown in Table I were incorporated into X31 HA (an H3 subtype HA) and recombinant vaccinia viruses were generated for their expression. Cell-surface expression of mutant HAs in recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells was analysed by ELISA using conformation-specific monoclonal antibodies that recognize different antigenic sites on the surface of the molecule. The data from these experiments (Table I) show that the wild-type (WT) and all mutant HAs are antigenically indistinguishable and expressed on the cell surface at similar levels.

Table I. Analysis of cell surface expression and conformation by ELISA.

| Monoclonal antibody | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | HC 3 (%) | HC 31 (%) | HC 67 (%) | HC 68 (%) | HC 100 (%) | HC 263 (%) |

| WT | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| LLL | 103 | 95 | 89 | 97 | 95 | 88 |

| L2A | 105 | 137 | 116 | 98 | 94 | 89 |

| L2G | 90 | 115 | 111 | 79 | 90 | 87 |

| F3A | 96 | 114 | 115 | 86 | 90 | 83 |

| F3G | 105 | 153 | 120 | 97 | 94 | 90 |

| I6A | 110 | 145 | 124 | 106 | 100 | 106 |

| I6G | 114 | 168 | 119 | 106 | 108 | 106 |

| F9A | 116 | 191 | 137 | 112 | 116 | 120 |

| F9G | 125 | 162 | 126 | 103 | 108 | 111 |

| I10A | 114 | 145 | 122 | 105 | 105 | 106 |

| I10G | 125 | 160 | 136 | 113 | 108 | 107 |

Values represent OD450nm ELISA readings as percentages relative to WT. The antibodies all recognize conformational epitopes on neutral pH HA (Daniels et al., 1983).

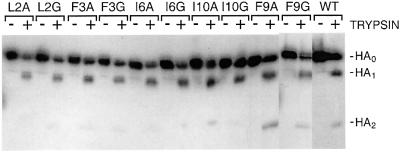

X31 HA contains a single arginine residue at the HA1–HA2 cleavage site, and is expressed at the cell surface as uncleaved HA0. HA-expressing recombinant vaccinia virus-infected CV1 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of trypsin and analysed by western blotting following polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under reducing conditions, to allow HA1 and HA2 dissociation. The results in Figure 1 show that WT and all mutant HAs are cleaved into HA1 and HA2 by trypsin, indicating again that all are expressed at the cell surface and also that all mutations are tolerated in the surface loop structure of the HA precursor cleavage site (Chen et al., 1998).

Fig. 1. Trypsin cleavage of cell surface-expressed precursor HAs. HA-expressing cells were incubated with or without trypsin and cell lysates were analysed by western blotting following separation of proteins by PAGE under reducing conditions.

Acid-induced conformational changes by mutant HAs

We used two monoclonal antibodies, HC3 and HC68, which can discriminate between different HA conformations, to determine whether the mutant HAs are able to undergo the structural changes that are required for fusion (Table II). Antibody HC3 recognizes HA1 146 in a surface loop that does not change structure at fusion pH, whereas HC68 recognizes HA1 193 in an antigenic site at the membrane-distal tip of the molecule that is lost as a result of acid-induced conformational changes (Daniels et al., 1983). ELISA experiments demonstrated that the structures of all the mutants changed at low pH. In addition, the ratio of HC68 to HC3 reactivity at different pH indicated that the structural transitions in all of the mutant HAs occurred at elevated pH, between 0.2 and 0.6 higher than for WT (Table II).

Table II. Determination of the pH of conformational change by ELISA.

| Ratio of HC68 to HC3 reactivity at pH |

ΔpHa | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.8 | ||

| WT | 0.539b | 0.513 | 0.505 | 0.491 | 0.491 | 0.454 | 0.381 | 0.251 | 0.153 | 0.145 | 0.0 |

| LLL | 0.550 | 0.556 | 0.517 | 0.331 | 0.150 | 0.177 | 0.127 | 0.109 | 0.103 | 0.097 | +0.40 |

| L2A | 0.487 | 0.460 | 0.474 | 0.367 | 0.292 | 0.209 | 0.184 | 0.171 | 0.176 | 0.165 | +0.30 |

| L2G | 0.569 | 0.537 | 0.554 | 0.409 | 0.347 | 0.313 | 0.306 | 0.293 | 0.280 | 0.256 | +0.23 |

| F3A | 0.539 | 0.519 | 0.477 | 0.299 | 0.188 | 0.110 | 0.097 | 0.084 | 0.069 | 0.061 | +0.34 |

| F3G | 0.482 | 0.450 | 0.427 | 0.272 | 0.212 | 0.134 | 0.126 | 0.121 | 0.106 | 0.095 | +0.35 |

| I6A | 0.423 | 0.358 | 0.328 | 0.201 | 0.153 | 0.146 | 0.133 | 0.127 | 0.129 | 0.118 | +0.39 |

| I6G | 0.430 | 0.410 | 0.401 | 0.222 | 0.161 | 0.146 | 0.130 | 0.128 | 0.118 | 0.103 | +0.37 |

| F9A | 0.482 | 0.459 | 0.482 | 0.356 | 0.288 | 0.273 | 0.222 | 0.237 | 0.205 | 0.204 | +0.32 |

| F9G | 0.513 | 0.453 | 0.409 | 0.273 | 0.163 | 0.121 | 0.117 | 0.099 | 0.104 | 0.090 | +0.33 |

| I10A | 0.458 | 0.328 | 0.249 | 0.147 | 0.105 | 0.117 | 0.116 | 0.115 | 0.109 | 0.079 | +0.51 |

| I10G | 0.486 | 0.308 | 0.130 | 0.112 | 0.107 | 0.108 | 0.121 | 0.108 | 0.108 | 0.087 | +0.56 |

aThe pH of conformational change is relative to WT HA. This was determined graphically by plotting the ratio of HC68/HC3 against pH and the midpoint of the slope was designated as the pH of conformational change.

bThe values represent the average of two to four separate experiments.

Membrane fusion by mutant HAs

We used three different assays to analyse the fusion properties of the mutant HAs: polykaryon formation by HA-expressing cells; erythrocyte haemolysis by rosettes of purified HA; and fluorescent dye transfer between labelled erythrocytes and HA-expressing cells.

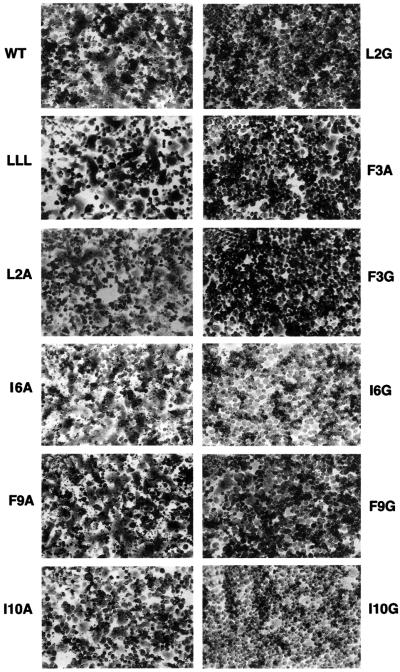

Polykaryon formation. The HAs on the surface of recombinant vaccinia virus-infected BHK cells were treated with trypsin to cleave HA0 and, following acidification, their capacity to form polykaryons was monitored by microscopy. Extensive fusion was induced by the WT HA, the single mutants L2A, I6A, F9A, I10A and a double mutant (G1L, F3L), which has the N-terminal sequence LLL (Figure 2). However, with mutants L2G, F3G, F3A, I6G, F9G and I10G, distinct polykaryon formation was not observed. All mutants that demonstrated fusion activity in these assays did so at higher pH than WT HA and reflected the elevated changes in conformation that were measured using the antibody assays.

Fig. 2. Polykaryon formation by BHK cells expressing WT or mutant HAs following acidification.

Erythrocyte haemolysis. HA micelles (rosettes) formed by interaction of HAs through their transmembrane domains were prepared by removal of detergent from detergent extracts of membranes isolated from HA-expressing cells. These rosettes display pH-dependent erythrocyte haemolysis activity that correlates with the fusion activity of expressed proteins (Wharton et al., 1986). They were prepared from the membranes of cells expressing WT HA, L2G, L2A, I6G and I6A mutants, and the double mutant (G1L, F3L). Rosettes were incubated at pH 5.1 in the presence of human erythrocytes and the levels of haemolysis were determined (Table III). The (G1L, F3L) double mutant rosettes caused erythrocyte haemolysis at levels approximately one-third of that displayed by WT. Rosettes of mutants L2A and I6A were able to mediate haemolysis at levels comparable to WT. The haemolytic activities of rosettes of mutants L2G and I6G were, however, greatly reduced.

Table III. Haemolytic activity of HA rosettes.

| HA | OD at 520 nm, pH 7.4 |

OD at 520 nm, pH 5.1 |

Average % haemolysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + trypsin | – trypsin | + trypsin | – trypsin | ||

| WT | 0.029 | 0.019 | 0.585 | 0.129 | 92.0 |

| LLL | 0.032 | 0.040 | 0.189 | 0.016 | 34.9 |

| L2A | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.510 | 0.070 | 87.7 |

| L2G | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.114 | 0.138 | 13.0 |

| I6A | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.533 | 0.023 | 100.6 |

| I6G | 0.014 | 0.045 | 0.200 | 0.011 | 37.0 |

Haemolysis is expressed as percentages of the total haemolysis caused by incubation of an equivalent aliquot of erythrocytes in 1% Brij 36T. Averages include experiments in which subsets of the collection of mutants were compared with WT.

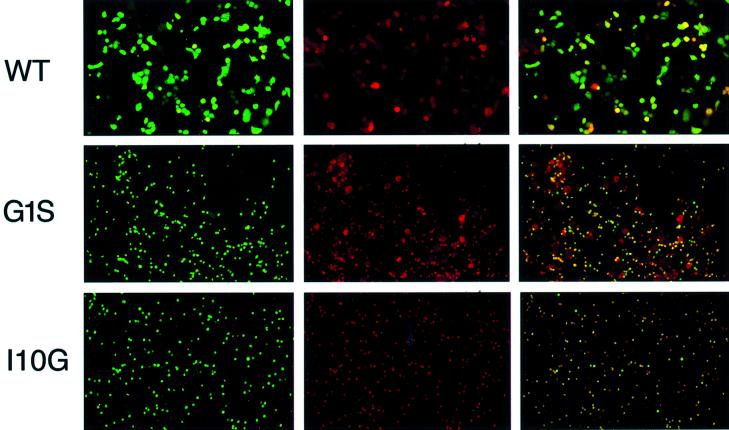

Analysis of fusion using fluorescent dye-loaded erythrocytes. To discriminate between the mixing of lipids in HA-containing membranes and target membranes and the transfer of soluble cellular contents that constitutes full fusion, human erythrocytes labelled with R18, a lipid fluorophore, and loaded with the soluble dye calcein were used in fusion assays. The labelled erythrocytes were attached to recombinant vaccinia-infected, HA-expressing HeLa cells, which had been pre-treated with trypsin to cleave HA0 and with bacterial neuraminidase to remove sialic acid from the cell surface. The pH was then adjusted to 5.0 and fusion between the erythrocytes and the expressing cell monolayers was monitored by fluorescence microscopy using filters for detecting rhodamine, fluorescein or both. The classification of mutant phenotypes divided broadly into three categories and examples of each are shown in Figure 3. In category 1, WT HA and the mutants L2A, I6A, F9A, F9G and I10A clearly mediated the transfer of both dyes, and in category 2, the mutants I10G and ΔG1 demonstrated neither lipid nor content mixing. In the third category, the other mutants, G1L, G1S, L2G, F3A, F3G, I6G and (G1L, F3L), displayed an intermediate phenotype. With these mutants lipid mixing as indicated by significant levels of R18 transfer was observed, but the transfer of calcein to indicate content mixing resulting from complete fusion was severely reduced. In agreement with the fusion results using the polykaryon formation assay, calcein transfer activity for both F3G and F3A was significantly impaired and the mutants L2A, I6A and I10A were found to have more calcein transfer activity than the homologous glycine substitution mutants. The notable difference between the results in dye transfer assay and the polykaryon assay concerned the F9G HA, which was inhibited for polykaryon formation but displayed WT levels of fusion activity in the dye-transfer experiments. The only mutants that were completely negative for both hemifusion and complete fusion were I10G, and ΔG1, which is a well characterized fusion-negative mutant (Garten et al., 1981; Steinhauer et al., 1995).

Fig. 3. Fusion of loaded human erythrocytes showing the soluble dye calcein (column 1), the lipid dye R18 (column 2), or convergent images (column 3). The three images for each mutant represent the same microscopic field. The small round images represent dye-loaded erythrocytes. The larger irregularly shaped images represent HA-expressing cells to which dye has been transferred.

Analysis of fusion peptide mutant viruses generated by reverse genetics

To assess the biological implications of fusion peptide modifications and extend the sensitivity of fusion assays through the amplification of virus replication, the effects of the mutations on virus infectivity and growth properties were assessed by incorporating several of the mutant HAs into infectious viruses by reverse genetics (Neumann et al., 1999). For these experiments the WSN strain of influenza was used, as we were able to rescue the WT HA of this strain with a higher efficiency than X31. The mutants were generated with at least two nucleotide changes per codon in order to ensure low frequencies of reversion to WT HA. Table IV shows the titres of HA mutant viruses rescued from 293T cells in two separate transfections. WT viruses were rescued efficiently, with titres as high as 4 × 107 p.f.u./ml. The mutants L2A, I6A and F9A were generated at titres one to two orders of magnitude lower than WT virus, and we were able to obtain viruses with the G1S mutant HA directly from transfected 293T cell supernatants at titres four to five orders of magnitude lower than WT. We were also able to generate viruses containing the HAs G1L, F9G, I10A, as well as the (G1L, F3L) double mutant. In these cases no plaques were observed using transfected cell supernatants, but subsequent passage in MDCK cells allowed recovery of infectious viruses. In all cases the sequences of the mutant HAs were verified in the viruses produced following one passage in MDCK cells. We did not obtain viruses when control transfections were carried out without an HA RNA transcription plasmid or when the ΔG1, L2G, I6G and I10G mutant HA-containing plasmids were used.

Table IV. Virus titres of transfected 293T cell supernatants (p.f.u./ml).

| HA | Virus rescued | Transfection 1 | Transfection 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | + | 3.8 × 106 | 4.0 × 107 |

| No HA | – | – | – |

| Δ G1 | – | – | – |

| G1L | + | – | – |

| G1S | + | 2.5 × 102 | 1.8 × 102 |

| LLL | + | – | – |

| L2A | + | 5.2 × 104 | 1.0 × 106 |

| L2G | – | – | – |

| I6A | + | 3.4 × 104 | 1.0 × 106 |

| I6G | – | – | – |

| F9A | + | 7.6 × 104 | 1.5 × 106 |

| F9G | + | – | – |

| I10A | + | – | – |

| I10G | – | – | – |

Mutant virus growth characteristics and reversion

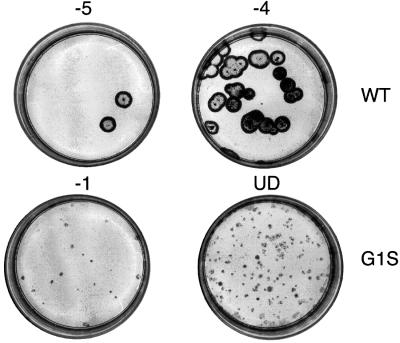

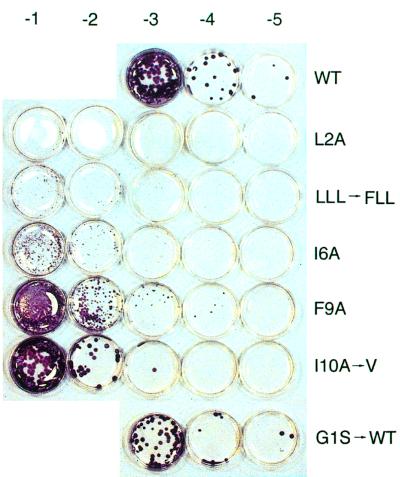

Relative to WT, all mutant viruses displayed reduced replication efficiency in MDCK cells. This is illustrated for the G1S mutant in Figure 4, which shows plaques from 293T cell supernatants following 4 days of incubation in MDCK cells. Whereas the WT virus plaques were large by this stage, the mutant formed only pinpoint plaques that required immunostaining for detection. Strikingly, after two passages of the G1S mutant virus, large plaques and high virus titres were observed. Sequence analysis revealed that the HA gene had acquired the two base changes needed to revert to WT. The plaque sizes and the titres of the other mutant viruses were also significantly reduced compared with WT. Figure 5 shows titrations of the mutant viruses derived from transfection one, following two passages in MDCK cells. Sequence analysis of the HAs of these viruses from MDCK passage two revealed examples of pseudoreversion at the mutated residue. The I10A to valine pseudorevertant, which displayed a large plaque phenotype (Figure 5), had acquired a single nucleotide substitution that changed the alanine to valine. In the other example of pseudoreversion, the N-terminal leucine of the (G1L, F3L) double mutant was found to have changed to phenylalanine. In this case, however, small plaque size and reduced titres were still observed.

Fig. 4. Titration of plaque-forming units from the supernatants of transfected 293T cell supernatants on MDCK cells (dilutions indicated above each plate). The plaques were immunostained at 4 days post-infection as described in Materials and methods. UD indicates that the cells were inoculated with undilute 293T cell supernatants. The other numbers indicate 10-fold dilutions of the supernatants that were used as inocula.

Fig. 5. Titration of WT and mutant viruses from transfection experiment 1 following two passages on MDCK cells.

Viruses from transfection two were also analysed following multiple passage in MDCK cells (Table V). Following six passages, sequence analysis demonstrated once again that pseudoreversion to valine had occurred in the I10A mutant virus. Similarly, pseudoreversion to valine was detected in the I6A virus; residue two of the L2A virus was found to be an approximately equal mixture of alanine and valine and in addition, a pseudoreversion to phenylalanine was observed in the G1L virus. The G1S and (G1L, F3L) double mutant virus, which changed rapidly upon passage of the viruses rescued from transfection one, remained unchanged in the initial passages of viruses from transfection two. On further passage, we found that between passage six and passage nine the G1S mutant had reverted to WT. For the transfection two viruses, only mutants, F9A, F9G, and the (G1L, F3L) double mutant virus remained unchanged on passage at the residues originally mutated. However, these viruses had acquired mutations in other regions of the HA, as had also the G1S and L2A viruses (Table V). In two of the mutants the L200S substitution was detected, which involves a residue in the membrane anchor domain. Despite the mutations acquired, the virus titres of the transfection two mutants following nine passages were still reduced relative to WT (Table V).

Table V. Titres and sequence changes of mutants at 37°C.

| Mutants | Transfection 1 |

Transfection 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passage 3 sequence change | Passage 6 sequence change | Sequence changes at passage 9 |

Plaque titre at passage 9 | ||

| Change in fusion peptide | Other changes in HA | (p.f.u./ml) | |||

| WT | – | –a | – | – | 9.0 × 106 |

| G1L | – | L to F | F | – | 2.4 × 105 |

| LLL | FLL | – | – | HA2 L200 to Sb | 1.2 × 105 |

| G1S | G | – | S to G | HA2 G47 to R | 1.4 × 105 |

| L2A | – | A/Vc | A/V | HA2 T156 to A | 7.8 × 105 |

| I6A | – | A to V | V | – | 1.0 × 104 |

| F9A | – | – | – | HA1 A35 to V | 5.4 × 106 |

| F9G | – | – | – | HA2 L200 to S | 2.4 × 106 |

| I10A | V | A to V | V | – | 3.7 × 105 |

aIndicates no change at the mutated position.

bIndicates H3 numbering.

cIndicates mixed population.

Discussion

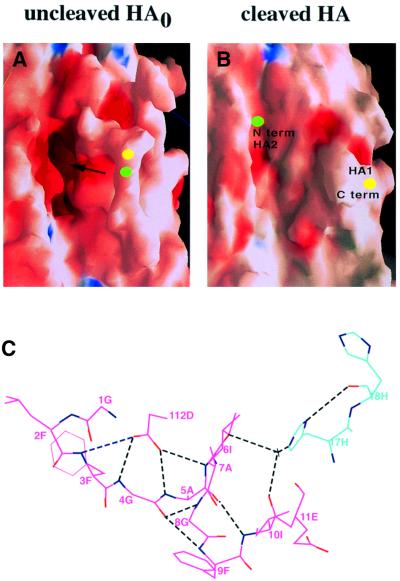

Structural analyses of HA in its different conformations, by X-ray crystallography and electron microscopy, indicate that the fusion peptide occupies three different locations and assumes at least two distinct structures. In combination, these structural requirements place particular constraints on the sequence of the fusion peptide, which is highly conserved. In uncleaved HA0 the 12 residues that constitute the N-terminal region of the fusion peptide upon cleavage form the membrane proximal section of an almost circular surface loop (Figure 6; Chen et al., 1998). Central in the loop, the site of cleavage is made accessible to proteases that cleave specifically at arginine to generate the N-terminus. Upon cleavage the 12 N-terminal residues of the fusion peptide re-fold into a pocket adjacent to the loop, burying a number of charged residues and avoiding aggregation or other non-specific interactions that an exposed hydrophobic region might form.

Fig. 6. Fusion peptide location in the HA precursor structure and in cleaved HA. (A) Space filling model of the HA0 precursor showing the cleavage loop extending toward the reader (Chen et al., 1998). The residue that forms the N-terminus of HA2 following cleavage is indicated in green and the C-terminus of HA1 is in yellow. The arrow indicates the cavity lined with ionizable residues into which the fusion peptide relocates following cleavage (B). Blue indicates positively charged surfaces and dark red indicates negatively charged surfaces. (C) The contacts made by the fusion peptide in the native HA structure following cleavage (Weis et al., 1990). HA1 residues are shown in blue and HA2 residues are shown in pink.

HA in this cleaved neutral pH conformation is primed for fusion activation in endosomes in the next round of infection. HA2 residues 1–4 and 5–9 of the fusion peptide form a two-turn structure (Figure 6) and their location in the pocket of charged residues influences the pH of activation and the thermal stability of the HA (Ruigrok et al., 1986), which are limited at least in part, by the pH of endosomes in cells to be infected and by the pH and temperature of the environments normally experienced by virus before endocytosis.

At the pH of fusion the HA structure is extensively rearranged leading to the third molecular location for the fusion peptide at the end of a newly formed 150 Å-long, rod-shaped structure, and apparently near the HA membrane anchor. In this position the fusion peptide is N-terminal to a trimeric α-helical coiled-coil, which forms the centre of the molecule. Its location is deduced from electron microscopy (Ruigrok et al., 1988), but its structure is not known as crystallization required its removal to prevent hydrophobic interactions between fusion peptides (Bullough et al., 1994). Numerous spectroscopic and NMR studies have indicated that synthetic analogues of HA fusion peptides are α-helical when associated with liposomes and estimates of ∼50% α-helix are often cited (see for example, Lear and DeGrado, 1987; Wharton et al., 1988; Gray et al., 1996; Dubovskii et al., 2000). The relevance of these estimates to the structure of the fusion peptide of the activated HA is not clear and the significance for fusion of the observations that the peptide analogues are tilted in relation to the membrane in which they insert is also unknown.

Our observations with the mutant HAs expressed in vaccinia recombinant-infected cells can be considered in relation to these three structures. All of the mutants were expressed at the cell surface as judged by their sensitivity to trypsin, and by their reactivities with monoclonal antibodies. The range of specificities of the antibodies with which they interacted also indicated that their conformations were indistinguishable from WT X31 HA, and this conclusion was supported by the specificity of the trypsin cleavage, C-terminal to arginine 329, to generate HA1 and HA2. These indices of the overall structures of the mutant HA0 precursors and the cleaved HA1–HA2 mutant HAs indicate that the mutations are tolerated by the HA in these two forms.

All of the mutants are also induced to change structure at low pH. However, the different pH at which the structural changes are induced indicates that the mutant fusion peptides are less stably accommodated in the cleaved HAs; all mutant HAs change structure at elevated pH relative to WT. Mutants I10G and I10A are the least stable. They are induced to change structure at pH 0.5–0.6 above that of WT. Amongst the other mutants, I6G, I6A and double mutant (G1L, F3L) change conformation at a pH of ∼0.4 above WT HA, with others being marginally more stable at a pH of 0.2–0.3 above WT. The structural basis for the differences in pH of conformational change for mutations in the fusion peptide has been discussed before (Daniels et al., 1985). For the residues addressed in this study, isoleucine 6 and isoleucine 10 appear to be tightly packed in the WT HA fusion peptide pocket (Figure 6), and their substitution might, therefore, be expected to have larger effects on molecular stability. Despite these characteristic changes in structure at low pH, not all vaccinia recombinant-expressed mutant HAs mediate membrane fusion. Mutants L2G, F3A, F3G, I6G and I10G, and as reported before (Steinhauer et al., 1995) and here, ΔG1, G1L and G1S, displayed little or no activity in assays of complete fusion. As L2A, I6A and I10A mutants all caused membrane fusion, additional glycine residues at any of these three positions rather than removal of the large aliphatic side-chains seems to be responsible for the loss of fusion activity.

Our experiments using rescued influenza viruses address three aspects of the mutant HAs: the influence of the mutations on virus rescue; their effects on infectivity relative to virus containing WT HA; and the nature of the amino acid substitutions in the HAs of mutants selected during virus passage in MDCK cells. With regard to virus rescue, we were unable to isolate viruses containing the mutant HAs ΔG1, L2G, I6G or I10G. These observations confirm the negative results in fusion assays obtained with vaccinia recombinant-expressed mutant HAs reported here and those on the inability of ΔG1 HA to mediate haemolysis presented before. Virus was obtained, however, that contained mutant HAs G1S or G1L, both of which displayed little or no complete fusion activity in the dye transfer or polykaryon formation assays. Virus was also obtained for the mutant F9G, which was weakly active in polykaryon formation but active in labelled erythrocyte fusion. Infectious viruses were also rescued containing the HA mutants L2A, I6A, F9A, I10A and the double mutant (G1L, F3L), which were all active in polykaryon formation and labelled erythrocyte fusion.

These results show that all mutants demonstrating detectable levels of complete fusion activity with expressed HAs could be rescued as infectious viruses (Table VI). Furthermore, they demonstrate that some, such as G1L and G1S, but not all of the HAs that displayed little or no fusion activity using conventional fusion assays were rescued. Combined with the observation that the efficiency of rescue with these viruses was up to a million-fold less efficient than WT, this indicates that the capacity for incorporation into infectious viruses may be the most sensitive and biologically significant assay for complete fusion activity currently available. Analyses of the plaque size and the amounts of virus produced indicated that all mutants produced less virus than the rescued WT, irrespective of whether or not virus was obtained directly from transfected cells. This was particularly the case for the G1S mutant illustrated in Figure 5, but yields of all mutant viruses were at least 1–2 orders of magnitude less than WT. Presumably the rate or the extent of fusion is decreased by the mutations and these properties are being investigated.

Table VI. Fusion activity and rescue of HA fusion peptide mutants.

| HA | 329a | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Full fusionb | Virus rescued | Rescue efficiencyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | R | G | L | F | G | A | I | A | G | F | I | + | + | 2.2 × 107 |

| LLL | – | L | L | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | <1d |

| G1L | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | <1d |

| G1S | – | S | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | 2.2 × 102 |

| L2A | – | – | A | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | 5.3 × 105 |

| L2G | – | – | G | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| F3A | – | – | – | A | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | n.d. | n.d. |

| F3G | – | – | – | G | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | n.d. | n.d. |

| I6A | – | – | – | – | – | – | A | – | – | – | – | + | + | 5.2 × 105 |

| I6G | – | – | – | – | – | – | G | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| F9A | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | A | – | + | + | 7.9 × 105 |

| F9G | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | G | – | + | + | <1d |

| I10A | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | A | + | + | <1d |

| I10G | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | G | – | – | – |

aResidue 329 is the arginine at which HA0 is cleaved. The other numbers denote the position in HA2.

bDenotes full fusion by any fusion assay.

cAverage titre of viruses in transfected 293T cell supernatants.

dIndicates viruses were rescued only after amplification of 293T cell supernatants on MDCK cells.

Previously, G1S HA has been reported to cause hemifusion (Qiao et al., 1999). Hemifusion has been defined as fusion of the outer, but not inner leaflets of the viral and cellular membranes, and it has been proposed as an intermediate in the fusion process which precedes the opening of fusion pores (White, 1995). Hemifusion by HA was first described for a mutant with a glycosylphosphatidyl inositol (GPI) membrane anchor, instead of its transmembrane domain (Kemble et al., 1994). Subsequent studies on GPI-anchored HA suggest that it can mediate the opening of fusion pores, which can be measured by electrophysiological methods, but these are incapable of further dilation (Markosyan et al., 2000). Our studies showing that G1S can be incorporated into infectious viruses indicate that this HA can mediate biologically functional fusion activity, albeit at significantly reduced efficiency. In addition to G1S, there are a number of mutants in our current study that would classify as fusion negative, but hemifusion positive, using the assays on expressed HAs. Among these, G1L was rescued in an infectious virus, whereas others such as L2G, F3A, F3G and I6G were not. The molecular basis for the varying degrees of hemifusion or the variation in achieving complete fusion is currently not clear.

The low yielding small plaque viruses included the double mutant (G1L, F3L). A fusion peptide with this sequence was initially detected in the HA of an H7 subtype virus selected for growth in MDCK cells in the presence of thermolysin as the fusion-activating cleavage enzyme (Orlich and Rott, 1994). Thermolysin cleaves C-terminal to G1 (Garten et al., 1981), but, in addition to a leucine N-terminus, the selection resulted in the insertion of leucine to give the N-terminal sequence LLL instead of the WT GLF. In the fusion assays reported here, the vaccinia recombinant-expressed double mutant HA (G1L, F3L), which also has LLL as the N-terminal sequence, was more active in polykaryon formation and haemolysis than previously observed for mutant G1L HA, which has the N-terminal sequence LLF (Steinhauer et al., 1995). The fact that viruses containing G1L and (G1L, F3L) mutant HAs were rescued confirms the original observation that leucine can serve as the N-terminal residue of the fusion peptide in infectious influenza viruses (Orlich and Rott, 1994). However, the lower efficiency at which both viruses were rescued, as well as their replication properties, also confirm the importance of the N-terminal glycine deduced from the negative results obtained with the ΔG1 mutant, and indicate that the contribution of the N-terminal glycine is not simply to conserve the length of the fusion peptide.

Passage of transfected cell supernatants in MDCK cells led to the appearance of a number of additional mutations that highlight preferred features of the fusion peptide. These mutations were of three types: reversion of the mutant to the WT residue; substitution of the mutant residue by a different residue than the WT, pseudoreversion; and additional mutations outside the fusion peptide. Reversion was only observed for the G1S mutant, emphasizing again the importance of N-terminal glycine. However, the pseudorevertant L1F was also isolated following passage of both the G1L mutant and the double mutant (G1L, F3L). The structural significance of this pseudoreversion is not clear but it is notable that the N-terminal residue of paramyxovirus fusion peptides is phenylalanine (Scheid and Choppin, 1977; Gething et al., 1978). Pseudoreversion was observed for the mutants L2A, I6A and I10A, in each case through the substitution of alanine by valine, indicating the preference for an amino acid with a larger side-chain in each of these positions. Again the structural significance of these selected changes is unknown as the conformation of the fusion-active fusion peptide has not been determined. Modelled as an α-helix, the 10 N-terminal residues of the fusion peptide cluster on opposite faces, one formed by glycines 1, 4 and 8, the other by the large side-chain hydrophobic residues L2, F3, I6, F9 and I10. A preference for valine over alanine in the pseudorevertants at positions 2, 6 and 10 is compatible with this α-helical model, as is the exclusion of glycine from these positions in fusogenic HAs. Whether the fusion-active fusion peptide forms oligomeric contacts is also unknown, but it is possible that it is trimeric and that the relatively polar glycine residues of different subunits may interact in the trimer interface (Popot and Engelman, 2000). Substitutions of the N-terminal glycine may also decrease fusion efficiency by destabilizing a putative trimer. In such a structure the large hydrophobic side-chains of residues L2, F3, I6, F9 and I10 would form the surface of the fusion peptide, buried in the target membrane.

Finally, four amino acid substitutions occur on passage in MDCK cells that involve residues outside the fusion peptide: A35V in HA1, and G47R, T156A and L200S in HA2. Amino acid substitutions in residue 47 in the short α-helix of neutral pH HA2, which becomes part of the new coiled-coil at fusion pH, have been detected before in high pH mutants of X31 and fowl plague influenza viruses, and were discussed in terms of their de-stabilizing effects on the location of the N-terminus of the fusion peptide at neutral pH (Daniels et al., 1985). The G47R mutant HA may have similar properties. It is also possible that the A35V substitution located in a loop near the fusion peptide at neutral pH that is known to change structure and location at fusion pH (Chen et al., 1999), and the substitution T156A, which causes the loss of a glycosylation site near the membrane anchor region of neutral pH HA2, may destabilize the neutral pH structure of HA. Such mutations, by increasing the pH of fusion, may facilitate the isolation in MDCK cells of the viruses in which they occur, as has been described for other rescued influenza mutants (Lin et al., 1997).

Particularly striking was the observation that two poorly fusogenic mutants that were rescued as infectious viruses independently gave rise to the same second site mutation, L200S. This position is the sixteenth residue of the 25–26 residue HA membrane anchor domain. There have been previous studies showing that chimeric HAs with alternative transmembrane domains can retain fusion function (Roth et al., 1986; Dong et al., 1992; Wilk et al., 1996; Odell et al., 1997; Melikyan et al., 1999; Kozerski et al., 2000), but there are examples with HA and other viral fusion proteins in which point mutations negatively affect fusion phenotype (Owens et al., 1994; Cleverley and Lenard, 1998; Melikyan et al., 1999; Taylor and Sanders, 1999). However, in the case of the L200S mutation, it appears that serine was selected at position 200 during passage of viruses with poor fusion activity, possibly to improve the fusogenicity of the viruses. Membrane fusion and virus rescue experiments involving mutants such as L200S, alone or in combination with other mutations, may define further such possibilities.

Materials and methods

Mutagenesis and expression

Mutant DNAs were generated using a QuickChange mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. Full-length HA genes were sequenced to verify the presence of the desired mutation and the absence of other changes. DNA sequencing was carried out with an ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit and run on ABI Prism 377 machines. Recombinant vaccinia viruses were generated by the method developed by Blasco and Moss (1995). HeLa, CV1, BHK-21, MDCK and 293T cells were all cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum.

Conformational change and membrane fusion assays

Conformational change assays by ELISA were performed on vaccinia virus-infected, HA-expressing HeLa cells (Steinhauer et al., 1991a), and heterokaryon formation was carried out using recombinant vaccinia-infected BHK cells Steinhauer et al. (1991b) as described previously. Trypsin cleavage experiments were carried out as described in Steinhauer et al. (1995) except that western blots were developed using ECL (Amersham Pharmacia) rather than using 125I-labelled second antibody. Preparation of HA rosettes from vaccinia-infected HA-expressing CV1 cell membranes and erythrocyte haemolysis assays were carried out as detailed previously (Godley et al., 1992). For the erythrocyte fusion/hemifusion assays erythrocytes were loaded with calcein, then octadecylrhodamine (R18). Briefly, a 5 mM calcein solution in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0 was loaded into human erythrocytes as described (Ellens et al., 1989). The R18 was then incorporated into the erythrocyte membranes as described by Morris et al. (1989). HeLa cells grown in chamber slides were infected with vaccinia recombinants overnight. They were washed twice with cell buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 2 mM CaCl2) and treated with 30 mU/ml (in cell buffer) of Clostridium perfingens neuraminidase (Boehringer) at 37°C for 60 min. Cells were washed and treated with 2.5 µg/ml TPCK trypsin (Sigma) for 5 min at 37°C to cleave HA, then washed with cell buffer containing 2.5 µg/ml trypsin inhibitor and washed again. Erythrocytes were added (0.4 ml, 0.01% haematocrit) and incubated for 15 min, then washed three times with cell buffer. Cells were washed once with cell buffer at pH 5.0, incubated for 1 min with cell buffer pH 5.0 and washed with pH 7.4 cell buffer. Cells were then incubated in complete medium for 30 min in a 37°C CO2 incubator before analysis by fluorescence microscopy.

Reverse genetics and analysis of mutants

The HA gene mutations were introduced into the RNA expression plasmid pPOL I WSN HA and the gene segment sequences were verified in entirety. Infectious influenza viruses were then generated from plasmid cDNAs essentially as described by Neumann et al. (1999). Human 293T cells were transfected with the 17 protein and RNA expression plasmids using either Mirus (Panvera) or Superfect (Qiagen) transfection reagents following the supplier’s guidelines. At 2 and 3 days post-transfection cell supernatants were passaged and also titrated on MDCK cells. Due to the small plaque size of the mutants, they were immunostained before counting. The immunostaining technique (all at room temperature) was carried out as follows on 35 mm dishes with 2 ml agar overlays. The cells were fixed by adding 1 ml of 0.25% glutaraldehyde to the overlay for 1 h. Following removal of the agar overlay, monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubated with PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h, and then incubated for 1 h with PBS/BSA containing HA-specific antibody. Cells were washed three times with PBS/BSA and then incubated for 1 h with a Staphylococcus aureus protein A–horseradish peroxidase conjugate in PBS/BSA. The monolayers were then washed five times with PBS and stained using a standard peroxidase substrate such as 4-chloro-1-naphthol. PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide was used to stop the reaction when the staining reached the desired intensity.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Y.Kawaoka and G.Hobon for kindly providing plasmids, and Dave Stevens, Lesley Calder, Kevin Booth and Carol Newman for technical assistance. We also thank Drs M.Knossow and Y.Gaudin for critical comments on the manuscript.

References

- Baker K.A., Dutch,R.E., Lamb,R.A. and Jardetzky,T.S. (1999) Structural basis for paramyxovirus-mediated membrane fusion. Mol. Cell, 3, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizebard T., Gigant,B., Rigolet,P., Rasmussen,B., Diat,O., Bosecke,P., Wharton,S.A., Skehel,J.J. and Knossow,M. (1995) Structure of influenza virus haemagglutinin complexed with a neutralizing antibody. Nature, 376, 92–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco R. and Moss,B. (1995) Selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses on the basis of plaque formation. Gene, 158, 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullough P.A., Hughson,F.M., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1994) Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature, 371, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey M., Cai,M., Kaufman,J., Stahl,S.J., Wingfield,P.T., Covell,D.G., Gronenborn,A.M. and Clore,G.M. (1998) Three-dimensional solution structure of the 44 kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41. EMBO J., 17, 4572–4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder L.J., Gonzalez-Reyes,L., Garcia-Barreno,B., Wharton,S.A., Skehel,J.J., Wiley,D.C. and Melero,J.A. (2000) Electron microscopy of the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein and complexes that it forms with monoclonal antibodies. Virology, 271, 122–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Lee,K.H., Steinhauer,D.A., Stevens,D.J., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1998) Structure of the hemagglutinin precursor cleavage site, a determinant of influenza pathogenicity and the origin of the labile conformation. Cell, 95, 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1999) N- and C-terminal residues combine in the fusion-pH influenza hemagglutinin HA2 subunit to form an N cap that terminates the triple-stranded coiled-coil. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 8967–8972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleverley D.Z. and Lenard,J. (1998) The transmembrane domain in viral fusion: essential role for a conserved glycine residue in vesicular stomatitis virus G protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 3425–3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R.S., Douglas,A.R., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1983) Analyses of the antigenicity of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH optimum for virus-mediated membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol., 64, 1657–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R.S., Downie,J.C., Hay,A.J., Knossow,M., Skehel,J.J., Wang,M.L. and Wiley,D.C. (1985) Fusion mutants of the influenza virus hemagglutinin glycoprotein. Cell, 40, 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J., Roth,M.G. and Hunter,E. (1992) A chimeric avian retrovirus containing the influenza virus hemagglutinin gene has an expanded host range. J. Virol., 66, 7374–7382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubovskii P.V., Li,H., Takahashi,S., Arseniev,A.S. and Akasaka,K. (2000) Structure of an analog of fusion peptide from hemagglutinin. Protein Sci., 9, 786–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellens H., Doxsey,S., Glenn,J.S. and White,J.M. (1989) Delivery of macromolecules into cells expressing a viral membrane fusion protein. Methods Cell. Biol., 31, 155–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fass D., Harrison,S.C. and Kim,P.S. (1996) Retrovirus envelope domain at 1.7 angstrom resolution. Nature Struct. Biol., 3, 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garten W., Bosch,F.X., Linder,D., Rott,R. and Klenk,H.D. (1981) Proteolytic activation of the influenza virus hemagglutinin: the structure of the cleavage site and the enzymes involved in cleavage. Virology, 115, 361–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething M.J., White,J.M. and Waterfield,M.D. (1978) Purification of the fusion protein of Sendai virus: analysis of the NH2-terminal sequence generated during precursor activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 75, 2737–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething M.J., Doms,R.W., York,D. and White,J. (1986) Studies on the mechanism of membrane fusion: site-specific mutagenesis of the hemagglutinin of influenza virus. J. Cell Biol., 102, 11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley L. et al. (1992) Introduction of intersubunit disulfide bonds in the membrane-distal region of the influenza hemagglutinin abolishes membrane fusion activity. Cell, 68, 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C., Tatulian,S.A., Wharton,S.A. and Tamm,L.K. (1996) Effect of the N-terminal glycine on the secondary structure, orientation and interaction of the influenza hemagglutinin fusion peptide with lipid bilayers. Biophys. J., 70, 2275–2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemble G.W., Danieli,T. and White,J.M. (1994) Lipid-anchored influenza hemagglutinin promotes hemifusion, not complete fusion. Cell, 76, 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenk H.D., Rott,R., Orlich,M. and Blodorn,J. (1975) Activation of influenza A viruses by trypsin treatment. Virology, 68, 426–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozerski C., Ponimaskin,E., Schroth-Diez,B., Schmidt,M.F. and Herrmann,A. (2000) Modification of the cytoplasmic domain of influenza virus hemagglutinin affects enlargement of the fusion pore. J. Virol., 74, 7529–7537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal M., Young,J.F., Palese,P., Wilson,I.A., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1983) Sequential mutations in hemagglutinins of influenza B virus isolates: definition of antigenic domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 4527–4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowitz S.G. and Choppin,P.W. (1975) Enhancement of the infectivity of influenza A and B viruses by proteolytic cleavage of the hemagglutinin polypeptide. Virology, 68, 440–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lear J.D. and DeGrado,W.F. (1987) Membrane binding and conformational properties of peptides representing the NH2 terminus of influenza HA-2. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 6500–6505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.P., Wharton,S.A., Martin,J., Skehel,J.J., Wiley,D.C. and Steinhauer,D.A. (1997) Adaptation of egg-grown and transfectant influenza viruses for growth in mammalian cells: selection of hemagglutinin mutants with elevated pH of membrane fusion. Virology, 233, 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malashkevich V.N., Schneider,B.J., McNally,M.L., Milhollen,M.A., Pang,J.X. and Kim,P.S. (1999) Core structure of the envelope glycoprotein GP2 from Ebola virus at 1.9-Å resolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 2662–2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markosyan R.M., Cohen,F.S. and Melikyan,G.B. (2000) The lipid-anchored ectodomain of influenza virus hemagglutinin (GPI-HA) is capable of inducing nonenlarging fusion pores. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikyan G.B., Lin,S., Roth,M.G. and Cohen,F.S. (1999) Amino acid sequence requirements of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of influenza virus hemagglutinin for viable membrane fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 1821–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris S.J., Sarkar,D.P., White,J.M. and Blumenthal,R. (1989) Kinetics of pH-dependent fusion between 3T3 fibroblasts expressing influenza hemagglutinin and red blood cells. Measurement by dequenching of fluorescence. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 3972–3978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G. et al. (1999) Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 9345–9350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobusawa E., Aoyama,T., Kato,H., Suzuki,Y., Tateno,Y. and Nakajima,K. (1991) Comparison of complete amino acid sequences and receptor-binding properties among 13 serotypes of hemagglutinins of influenza A viruses. Virology, 182, 475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odell D., Wanas,E., Yan,J. and Ghosh,H.P. (1997) Influence of membrane anchoring and cytoplasmic domains on the fusogenic activity of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. J. Virol., 71, 7996–8000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlich M. and Rott,R. (1994) Thermolysin activation mutants with changes in the fusogenic region of an influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol., 68, 7537–7539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens R.J., Burke,C. and Rose,J.K. (1994) Mutations in the membrane-spanning domain of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein that affect fusion activity. J. Virol., 68, 570–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot J.L. and Engelman,D.M. (2000) Helical membrane protein folding, stability and evolution. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 881–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H., Armstrong,R.T., Melikyan,G.B., Cohen,F.S. and White,J.M. (1999) A specific point mutant at position 1 of the influenza hemagglutinin fusion peptide displays a hemifusion phenotype. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 2759–2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth M.G., Doyle,C., Sambrook,J. and Gething,M.J. (1986) Heterolo gous transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains direct functional chimeric influenza virus hemagglutinins into the endocytic pathway. J. Cell Biol., 102, 1271–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruigrok R.W., Martin,S.R., Wharton,S.A., Skehel,J.J., Bayley,P.M. and Wiley,D.C. (1986) Conformational changes in the hemagglutinin of influenza virus which accompany heat-induced fusion of virus with liposomes. Virology, 155, 484–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruigrok R.W., Aitken,A., Calder,L.J., Martin,S.R., Skehel,J.J., Wharton,S.A., Weis,W. and Wiley,D.C. (1988) Studies on the structure of the influenza virus haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol., 69, 2785–2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid A. and Choppin,P.W. (1977) Two disulfide-linked polypeptide chains constitute the active F protein of paramyxoviruses. Virology, 80, 54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel J.J. and Waterfield,M.D. (1975) Studies on the primary structure of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 72, 93–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1998) Coiled-coils in both intracellular vesicle and viral membrane fusion. Cell, 95, 871–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (2000) Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 531–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel J.J., Bayley,P.M., Brown,E.B., Martin,S.R., Waterfield,M.D., White,J.M., Wilson,I.A. and Wiley,D.C. (1982) Changes in the conformation of influenza virus hemagglutinin at the pH optimum of virus-mediated membrane fusion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 79, 968–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer D.A., Wharton,S.A., Skehel,J.J., Wiley,D.C. and Hay,A.J. (1991a) Amantadine selection of a mutant influenza virus containing an acid-stable hemagglutinin glycoprotein: evidence for virus-specific regulation of the pH of glycoprotein transport vesicles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 11525–11529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer D.A., Wharton,S.A., Wiley,D.C. and Skehel,J.J. (1991b) Deacylation of the hemagglutinin of influenza A/Aichi/2/68 has no effect on membrane fusion properties. Virology, 184, 445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer D.A., Wharton,S.A., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1995) Studies of the membrane fusion activities of fusion peptide mutants of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol., 69, 6643–6651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton R.B., Fasshauer,D., Jahn,R. and Brunger,A.T. (1998) Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature, 395, 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G.M. and Sanders,D.A. (1999) The role of the membrane-spanning domain sequence in glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 2803–2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J.A. and Kawaoka,Y. (1993) Importance of conserved amino acids at the cleavage site of the haemagglutinin of a virulent avian influenza A virus. J. Gen. Virol., 74, 311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis W.I., Cusack,S.C., Brown,J.H., Daniels,R.S., Skehel,J.J., Wiley,D.C. (1990) The structure of a membrane fusion mutant of the influenza virus haemagglutinin. EMBO J., 9, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenhorn W., Dessen,A., Harrison,S.C., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1997) Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature, 387, 426–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenhorn W., Calder,L.J., Wharton,S.A., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1998) The central structural feature of the membrane fusion protein subunit from the Ebola virus glycoprotein is a long triple-stranded coiled-coil. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 6032–6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton S.A., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1986) Studies of influenza haemagglutinin-mediated membrane fusion. Virology, 149, 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton S.A., Martin,S.R., Ruigrok,R.W., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1988) Membrane fusion by peptide analogues of influenza virus haemagglutinin. J. Gen. Virol., 69, 1847–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J.M. (1990) Viral and cellular membrane fusion proteins. Annu. Rev. Physiol., 52, 675–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J.M. (1995) Membrane fusion: the influenza paradigm. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 60, 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk T., Pfeiffer,T., Bukovsky,A., Moldenhauer,G. and Bosch,V. (1996) Glycoprotein incorporation and HIV-1 infectivity despite exchange of the gp160 membrane-spanning domain. Virology, 218, 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson I.A., Skehel,J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (1981) Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 Å resolution. Nature, 289, 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Singh,M., Malashkevich,V.N. and Kim,P.S. (2000) Structural characterization of the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein core. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 14172–14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]