Abstract

Objective: After arguing that most community-based organizations (CBOs) function as complex adaptive systems, this white paper describes the evaluation goals, questions, indicators, and methods most important at different stages of community-based health information outreach.

Main Points: This paper presents the basic characteristics of complex adaptive systems and argues that the typical CBO can be considered this type of system. It then presents evaluation as a tool for helping outreach teams adapt their outreach efforts to the CBO environment and thus maximize success. Finally, it describes the goals, questions, indicators, and methods most important or helpful at each stage of evaluation (community assessment, needs assessment and planning, process evaluation, and outcomes assessment).

Literature: Literature from complex adaptive systems as applied to health care, business, and evaluation settings is presented. Evaluation models and applications, particularly those based on participatory approaches, are presented as methods for maximizing the effectiveness of evaluation in dynamic CBO environments.

Conclusion: If one accepts that CBOs function as complex adaptive systems—characterized by dynamic relationships among many agents, influences, and forces—then effective evaluation at the stages of community assessment, needs assessment and planning, process evaluation, and outcomes assessment is critical to outreach success.

For several months, an outreach team from a South Texas medical school library carefully planned a community outreach training session and focus group to be held at a community center serving a low-income Hispanic colonia (community) in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. The outreach team developed relationships with community center staff and engaged their assistance in the planning. The team offered preliminary training to residents of the community, generating enthusiasm and engaging some of them as outreach partners. These partners, in turn, personally invited other community members to the training session and focus group. The team purchased gift cards from a local grocery store as incentives to attract participants and hired an experienced focus group facilitator from South Texas to conduct the session in Spanish.

The final session was scheduled for ten o'clock on a weekday morning in mid-March. When the outreach team arrived at the site, community center staff warned that attendance probably would be very low because of bad weather: the temperature had dipped to thirty-seven degrees. Outreach team members, particularly those who had grown up in middle-class neighborhoods in northern climates, could not imagine how plans could fall apart over such weather—a dry day, with temperatures above freezing. However, the community staff predictions were accurate. Perhaps because the families lacked adequate clothing or household heat, this weather was bad enough to keep the children home from school and mothers from attending the training session. It was, in fact, a slow day for outreach.

Most would call this an example of Murphy's Law: what can go wrong, will go wrong. It also demonstrated the unpredictable nature of the environments of community-based organizations (CBOs). Funding sources come and go. The turnover of low-paid and volunteer workers tends to be high. Changing politics lead to changing priorities. The involvement of and relationship between stakeholders can make decisions and progress difficult. For instance, Scherrer outlined the challenges faced in an environmental public health outreach project in Chicago: lack of institutional support of Internet technology, participants unwilling to show lack of knowledge until they knew and developed trust in the outreach coordinator, difficulty in building cooperative relationships among volunteers, and unique culture of each organization [1].

Such challenges make outreach, as well as evaluation, quite difficult. Evaluation methodologies touted as yielding the most credible findings rely on outreach activities that progress in a predictable, linear fashion, with carefully executed interventions (independent variables), explicitly defined outcomes (dependent variables), and tightly controlled extraneous variables. Many consider experimental and quasi-experimental research methodologies, control groups, randomized samples, and standard experience across groups necessary elements of good research design, yet a typical CBO outreach project seldom can meet all or any of the ideal research conditions. Furthermore, the focused nature of such methods often misses some of the unexpected positive outcomes. On the other hand, when positive results are not obtained, such methods seldom help explain why.

The first step in conducting better evaluations of CBO-based information outreach is to understand and accept the nature of the environment in which outreach activities are conducted. This paper presents the basic characteristics of complex adaptive systems, a concept rooted in complexity theory, and argues that most CBOs can be considered complex adaptive systems. It then argues that evaluation is a tool for helping teams adapt their outreach to the system and thus to maximize their success. Finally, it describes the goals, questions, indicators, and methods that may prove most helpful at each stage of evaluation: community assessment, needs assessment and planning, process or formative evaluation, and outcomes evaluation.

BACKGROUND

The impetus for this paper came from the author's experiences as an evaluation specialist with the library outreach staff at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA) Libraries located in San Antonio and Harlingen, Texas, on the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley Health Information Hispanic Outreach (HI HO) Project [2, 3]. In September 2001, the UTHSCSA Library received a contract from the National Library of Medicine (NLM) to develop an outreach program in the medically underserved Lower Rio Grande Valley. NLM was particularly interested in outreach to communities in the valley because it was about to launch a new version of MedlinePlus, featuring Spanish-language consumer health care information. The Lower Rio Grande Valley, with its high proportion of Spanish or bilingual residents, seemed an ideal community of users for MedlinePlus en español [2, 3].

The outreach team, consisting of UTHSCSA librarians and an evaluation specialist, conducted an extensive community assessment of the Lower Rio Grande Valley community and settled on four sites for conducting outreach: a health careers high school, the community center mentioned above, and two medical clinics with a patient base of primarily low-income Hispanic families. At the high school, the team developed a peer tutor program in partnership with the school library, with four students as the primary trainers of MedlinePlus. At the clinics, we targeted our outreach efforts toward diabetes educators, assuming that they would use the databases to access health information about diabetes as part of their instructional responsibilities, particularly for their Spanish-speaking clients. Our key partners at the community center were promotoras, residents of the community (all women in this case) who had received training about local health and social services. The promotoras are the point persons in their community for helping residents get assistance and information. The promotoras in this outreach project had been trained through the Texas A&M University Center for Housing and Urban Development (TAMU-CHUD), which coordinates the promotora program as part of a broader colonia development effort along the Texas-Mexico border. The outreach staff used four criteria to evaluate outreach success: (a) members of the community who served at each site spontaneously used MedlinePlus either for work or for personal use; (b) people who participated in CBO activities used MedlinePlus in the absence of members of the library outreach team; (c) CBO participants who became our key contacts, like promotoras and peer tutors, generated ideas for introducing MedlinePlus into their organization or ideas for teaching more members of the community to use the database; and (d) key contacts at the sites reported that they were teaching others to use MedlinePlus. Using these criteria, the outreach team judged two of the sites (the high school and the community center) as highly successful but saw the other two sites as less successful.

We have since received funding to expand our outreach efforts. In 2003, we received NLM contract monies to extend our work with Hispanic communities like Cameron Park in the Texas-Mexico border areas of Harlingen-Brownsville, Laredo, and El Paso. In September 2004, new NLM-funded projects were launched to extend the high school outreach project to other Texas schools in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, San Antonio, and Laredo. We learned fundamental lessons on our first project that have guided our current project evaluations. These lessons helped us improve our community and needs assessment, process and formative evaluation, and outcomes assessment. We have gotten better at outreach, in part because we have learned to adapt to the complex environments of our CBOs using evaluation methods.

COMMUNITY-BASED ORGANIZATIONS (CBOS) AS COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS

The concept of complex adaptive systems—which comes from a body of literature known as complexity science, chaos theory, or network science—is being applied in areas of study as diverse as physics, engineering, terrorist network activity, and the spread of infectious diseases [4]. The concept of complex adaptive systems has become increasingly popular in the organizational literature as a basis for understanding, coping with, and succeeding in the chaos of business environments [5–7]. In health care, complex adaptive system theory has been applied to describe patterns of behavior in clinical practices [8, 9]. The literature generally describes the following key traits of complex adaptive systems.

Complex adaptive systems feature an entangled web of relationships among many agents and forces, both internal and external. These influences cause constant change, adaptation, and evolution of the system in an unpredictable, nonlinear manner. This interconnectedness of the elements in the system can lead to unpredictable reactions systemwide, with small events sometimes having big impacts, while large, planned efforts may have little effect at all.

Complex adaptive systems are self-organizing. Patterns of behavior are not created from top-down policy. They emerge through a complicated system of relationships, influences, and feedback loops inside and outside the system. Thus, change in a system cannot be forced; it must be shaped.

Complex adaptive systems do not move predictably toward an end goal. Timelines for outreach activities must be flexible, because bursts of activity around a given project may be followed by periods of dormancy. Unexpected developments can either enhance or thwart plans. In fact, the evolutionary nature of a complex adaptive system means that there is no end goal. What progress may have been accomplished in a given outreach project may disintegrate rapidly as conditions change.

Communication is heaviest at the boundaries of a system. Boundaries exist between two different parts of a system that must adjust to and with each another. For example, in our community center projects, boundaries existed between community center staff hired by counties, the promotoras, and TAMU-CHUD coordinating staff. Boundaries are not good or bad; they are simply parts of the system that generate communication. For this reason, they often are an excellent source of information about where outreach activities might be effective in the system.

Systemwide patterns of behaviors can be observed. A paradox of complex adaptive systems is that, while they can be dynamic and changeable, they also can demonstrate systemwide patterns of behavior, generated by variables known as attractors, which will be repeated at many levels of the system and can be difficult to alter. Attractors may be written organizational priorities, seasonal events like year-end fiscal budgets, or more erratic variables like the day-to-day needs of the clients served by a CBO. Outreach staff are likely to design effective outreach projects if they can recognize the recurring patterns and work with them.

Feedback loops are the mechanisms for change in a system. Feedback loops carry information, material, and energy among agents in the system. If feedback loops are well designed, they facilitate change and adaptation of the system.

Patterns of behavior may repeat themselves at different levels of a system and across systems. In a complex adaptive system, different attractors stimulate similar responses and those responses will be observed at different levels and parts of the system. These patterns are known as fractals [10]. While behavior is never exactly the same, similarities will occur across parts of the system, across systems, and across time.

DIFFUSION OF INNOVATION: A USEFUL FRACTAL

While complex adaptive systems are characterized by their uniqueness, dynamism, and changing nature, fractals emphasize similarities in system behaviors that can be observed and used. Because these patterns exist, published reports of outreach projects become crucial to all who are trying to conduct similar outreach projects, because they may provide useful background information for project planning.

While fractals will be somewhat system specific, the well-documented diffusion of innovation theory describes one practical fractal observed when communities adopt new innovations. This fractal can be very useful for health information outreach [11]. (See Burroughs and Wood for a discussion of applying diffusion of innovation and other social theories to outreach planning [12].) Charles and Henner [13] give an example of how a project used this theory as the basis of a training program to enhance health professionals' use of Internet health resources. The project recruited and trained innovators in the use of Internet resources, treating them as potential change agents for how other health professionals in the state would eventually access public health information.

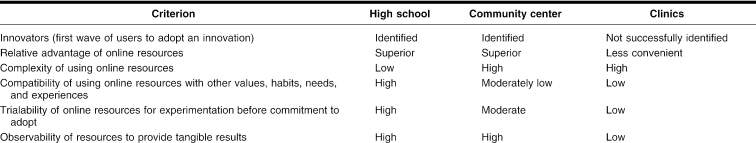

In our four sites, diffusion of innovation did a remarkably good job of describing the patterns of adoption of MedlinePlus or lack thereof. Table 1 compares the key features influencing diffusion of innovation at our four sites. For example, at our high school site, our innovators were school librarians and students, because the relative advantage of MedlinePlus was superior to other search methods, they used to access health information (e.g., Google, print resources). Complexity was low because the stakeholders had Internet experience, and compatibility was high, because they often searched the Internet for information as part of their day-to-day activities. They had good opportunity to work with MedlinePlus (trialability) because of the technology available in the school, and, once they realized teachers would accept MedlinePlus materials for research projects, both librarians and students observed rewards (locating acceptable information quickly either for school clients or for research).

Table 1 A comparison of community-based organization (CBO) sites' readiness for MedlinePlus using diffusion of innovation criteria

Diffusion of innovation also explains the community center promotoras' interest in MedlinePlus. First, they had no other convenient access to health information (relative advantage). Their role was to provide individualized assistance to community residents, so access to such an expansive health database was compatible with their values, needs, and habits. They saw tangible rewards when using MedlinePlus (observability) in that they could quickly provide help for residents' health concerns and sometimes relieve residents' anxiety. However, two barriers made our work with the promotoras more challenging than our work with students. First, the trialability was lower at the community center, because Internet access was unreliable. This problem was resolved later in the project when promotoras secured laptops and Internet wireless cards through a grant. Second, the complexity of Internet usage was higher for promotoras than students because promotoras had less experience with computers.

Analysis of our evaluation data at the end of the project indicated that our clinic sites were at different levels of “readiness” for introduction of MedlinePlus. The diabetes educators, whom we thought would be innovators, actually showed little motivation to learn MedlinePlus or show it to patients. They did not appear to see a relative advantage of MedlinePlus over the educational materials they already possessed. Neither diabetes educator at either clinic seemed comfortable with computers nor used computers or the Internet, so the process of using MedlinePlus was incompatible with their habits and complex for them to understand. While they had access to computers at the clinics to try out the online resources, their lack of comfort with computers made them unlikely to explore the database. They saw no visible rewards for using the Website. In fact, their own lack of computer experience and comfort and their perception that their patients would share their reticence made them believe the online resources had greater cost than benefit. Consequently, MedlinePlus never “diffused” extensively into these particular clinics during the project time frame.

We learned that diffusion of innovation was so descriptive of the patterns of adoption at our sites, we needed to use it to get a better understanding of communities' readiness for innovation before starting other outreach projects. We designed the guide shown in the appendix to help us with community assessment in other projects.

CBOS AND PROGRAM EVALUATION

If one assumes that CBOs often have characteristics of complex adaptive systems, evaluation methods for assessing the complex environments of community-based organizations must be efficient and effective. They must be useful to those implementing the outreach program and flexible enough to adapt to the changing CBO environment. The methods must be participatory so that local stakeholders can help integrate outreach efforts into their organizations. Finally, evaluation must answer the questions and goals specific to each of the four stages of evaluation: community assessment, planning and needs assessment, process evaluation, and outcomes evaluation.

Community assessment

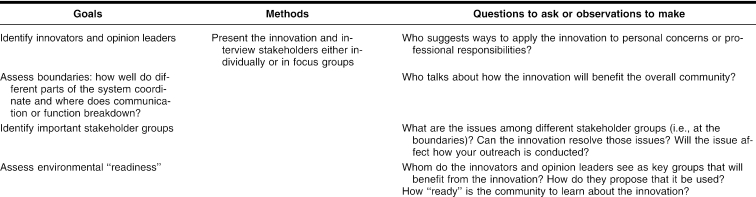

If CBOs often function as complex adaptive systems, then the community assessment stage is critical. Table 2 presents the key questions to be addressed during community assessment and methods for doing so. Participatory methodologies are essential because stakeholders from different parts of the system are brought into the discussion. Rapid rural appraisal (RRA, also known as rapid appraisal) comprises flexible, inexpensive methods that provide a great deal of information about a community (see the USAID's publication Conducting a Participatory Evaluation for descriptions of rapid appraisal methods [14]). RRA has been used effectively in situations where collection of quantitative data leads to missing or unreliable data [15]. While the methods vary, they commonly involve unstructured interviews with key informants representing various stakeholder groups.

Table 2 Evaluation during community assessment

Because of the quick, loosely controlled procedures, rapid appraisals may lack credibility in some research and evaluation circles. However, a study comparing the accuracy of rapid appraisal with conventional surveys in identifying people with disabilities in a South Indian community showed that both approaches were equally accurate in identifying community members with disabilities [16]. RRA, however, provided a more descriptive view of how community members talk and think about disability. RRA also permitted the researchers to educate the respondents throughout the data collection process.

For evaluation projects oriented toward introducing innovations into communities, community assessment must be designed to identify the innovators in the community and their relationship to others. The promotoras, for instance, immediately saw the potential for MedlinePlus to help them meet a need. Before learning how to access MedlinePlus, the promotoras had limited resources for helping residents who came to them with health problems. Their options before MedlinePlus training were to make appointments for community residents at clinics or to contact a local agency in search of printed information. MedlinePlus gave them immediate access to information for community residents with health care concerns.

Evaluation also must be designed to bring stakeholders from different parts of the system together, so that interaction of CBO community members across boundaries can be observed. As mentioned above, boundaries separate different parts of a system, and communication occurs across boundaries to help coordinate the system. Thus, group discussion formats are also likely to identify stresses, tensions, and problems that the innovation can relieve. For instance, a boundary existed between students and teachers at our high school site. Students preferred the convenience of accessing information through the Internet, but teachers did not trust Internet sources and feared that students could more easily plagiarize online materials than printed ones. This tension, though subtle, was observed through teacher and student focus groups. Thus, we knew our training would be most rapidly adopted by students, but we would have to train, and reassure, teachers to realize the potential of MedlinePlus in the school community.

It is also important to assess the readiness of stakeholders and of the CBO itself in terms of the characteristics that facilitate diffusion of innovation into communities. As we planned outreach, we considered MedlinePlus as a tool primarily for CBO staff and their clients to gather information. Given that, we needed to know how they currently get information and if MedlinePlus offers advantages over their usual strategies. With the trialability dimension, we had to be sure that, once we demonstrated MedlinePlus or trained people in its use, they had access to technology that would allow them to use their new skills and knowledge. We struggled with connectivity problems at our community center (both from the HI HO project and subsequent projects), especially after the state eliminated the technology infrastructure funds that had provided computer technology and online access for many CBOs. At the clinics, computers were available but were not on the desk tops of all staff members until later in the project.

Finally, we needed to understand how, and how quickly, people we trained might be able to describe the rewards of using the innovation. In early demonstrations at our sites, the high school and community center groups immediately talked about how MedlinePlus would help their organizations. At the clinics, staff were less able to imagine ways that MedlinePlus would help them with their responsibilities toward patients. They were quite willing to allow us to work directly with patients in their waiting rooms, but they believed their patients would need extensive assistance in using computers and they did not feel they had the staff to provide that support. In other words, the staff did not see immediate observable rewards in adopting the use of MedlinePlus. Consequently, MedlinePlus was never integrated into the clinics as it was at the school and community center sites.

Because our funding for outreach is limited, we must choose our sites wisely. We believe our most cost-effective outreach will occur at sites where we successfully locate community partners (innovators) who will pass along their knowledge to others in the community or help others access online resources. Our standard method now for assessing the community is first to meet the people who run the organizations and then ask them to assemble people they think would be interested in a short MedlinePlus training. We offer demonstrations to different groups, asking questions of participants and carefully observing their reactions and enthusiasm. By developing a community profile using the guide, we can assess the readiness of the CBO to introduce MedlinePlus into the community it serves. We ask those attending the demonstrations to identify the ongoing activities of the organization where training sessions or one-to-one help can be presented. This methodology helps us discern the innovators, who will become our partners in presenting MedlinePlus to the community. If those attending our demonstration show little interest in becoming active partners in outreach, we are reluctant to use that CBO as a site because we believe the community members are not yet ready to learn about and integrate the innovation.

Needs assessment and planning

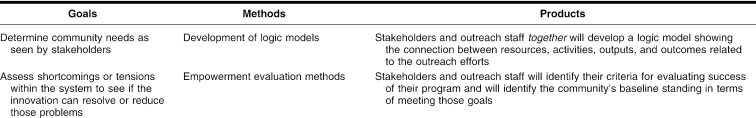

We have learned that our outreach efforts will work much better if the community members tell us how we can meet their needs. Table 3 shows the goals of needs assessment and planning, along with the methods for conducting this stage of evaluation. Ideally, we would use participatory approaches in the needs assessment and planning stages of outreach (see, for instance, the guide presented at the W. K. Kellogg Foundation Website [17] or Fetterman's empowerment evaluation model [18]). For either of these methods, stakeholders as a group set objectives, determine criteria for success, and, in the case of empowerment evaluation, determine how to evaluate it.

Table 3 Evaluation during needs assessment and planning

In real life, participatory methods like this take a lot of organization and are difficult to sustain over time. So we use rudimentary versions of these techniques that take less time from community members. We always try to schedule discussion sessions at our initial demonstrations, asking questions like “How can this product help the residents?” “What classes are you currently teaching that could incorporate this tool?” or “How would you know whether or not the community was benefiting from this product?” We then organize the plan based on their comments. The community assessment guide (Appendix) is useful during the needs assessment and planning phase as well.

We also ask community members how they will know that MedlinePlus has helped the participants in the community or organization. This question is designed to help us identify indicators and methods for outcome evaluation that our stakeholders will find credible.

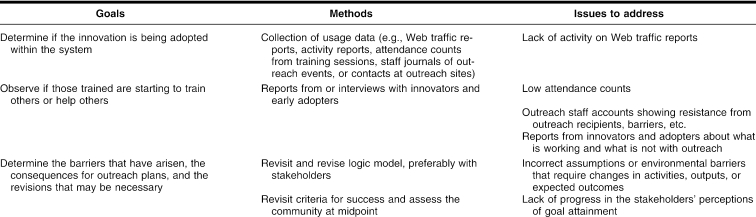

Process evaluation

Stakeholders' initial enthusiasm for MedlinePlus is not sufficient to ensure project success. Outreach teams need to have methods for monitoring the changing environment of CBOs so they can adapt their plan as needed. For instance, just as our outreach staff had developed a functional schedule for one-to-one outreach activities with patients in one of the clinic waiting rooms, the clinic suddenly introduced a new computer system into its previously low-tech environment and shut down for weeks to train staff. We needed to adapt to incorporate this sudden change in plan. Table 4 identifies the goals and methods for process evaluation.

Table 4 Process evaluation

In monitoring our CBO environments, we kept records of contacts and attendance at different sites. Along with recording numbers of interactions that our outreach team had with participants during each visit, our outreach staff also recorded descriptions of participants' reactions to MedlinePlus. This allowed us to assess psychological barriers patients had toward the Internet and computers.

Our other key monitoring methods included site visits and interviewing. The evaluator interviewed members of stakeholder groups as well as members of the outreach team frequently and informally. The monitoring interviews sought to answer two basic questions: “How are you and the community using MedlinePlus?” and “What barriers are you facing when trying to use it or teach it?” This method, for instance, revealed the difficulty the promotoras had in finding the “en español” button on the monitor screen. The outreach librarian also learned that one promotora did not have a concept of portals. Once the promotora left the MedlinePlus Website to go to another site, she did not know how to navigate back to MedlinePlus, so she would turn off the computer and start over again.

The important point here is that the whole outreach staff was instrumental in collecting information to help monitor and document progress and barriers. The key was to give them two simple evaluation questions to monitor the site: “How are the stakeholders using MedlinePlus?” and “What barriers are getting in the way of our outreach efforts?” They then kept journals of their contacts with stakeholders to capture information regarding these two questions. If outreach staff have very simple evaluation goals and ways to record their observations, the collection of formative information can become second nature to them. In turn, they will discover subtle barriers that can be fixed with minimal training or assistance.

In hindsight, we did a much better job of monitoring our high-yield pilot projects (the high school and the community center) than our low-yield ones (the clinics). We naturally were attracted to the sites where we observed enthusiasm for our product. However, on our final interviews at the clinics, we discovered some unexpected innovators who had been present at our demonstrations and had picked up some MedlinePlus search skills. They reported using MedlinePlus to research personal health concerns. If we had identified these innovators earlier, our success at these sites might have been enhanced.

Outcomes assessment

Outcomes assessment can be one of the most challenging aspects of outreach. Many evaluation methods are directed toward tracking changes in individual participants. We faced two major problems with this approach. First, we provided very individualized assistance to participants, so outcomes are unique to each person and, therefore, difficult to quantify compared to settings where learning outcomes are standardized across trainees. Second, our contacts with CBO clients or community residents are often transient, such as brief interactions at health fairs or a one-time session during a community center visit. Locating participants for follow-up surveys can be almost impossible. Therefore, monitoring changes in individual outreach clients may not be the best way to document success.

In complex adaptive systems, an analysis of system changes may yield a better understanding of outreach outcomes. A combination of quantitative and qualitative methods will yield the most complete picture of change in the system. The quantitative methods are necessary to see the extent the innovation has affected the system. The open-ended nature of qualitative methods is likely to uncover unexpected outcomes, both positive and negative, that are typical in complex adaptive systems.

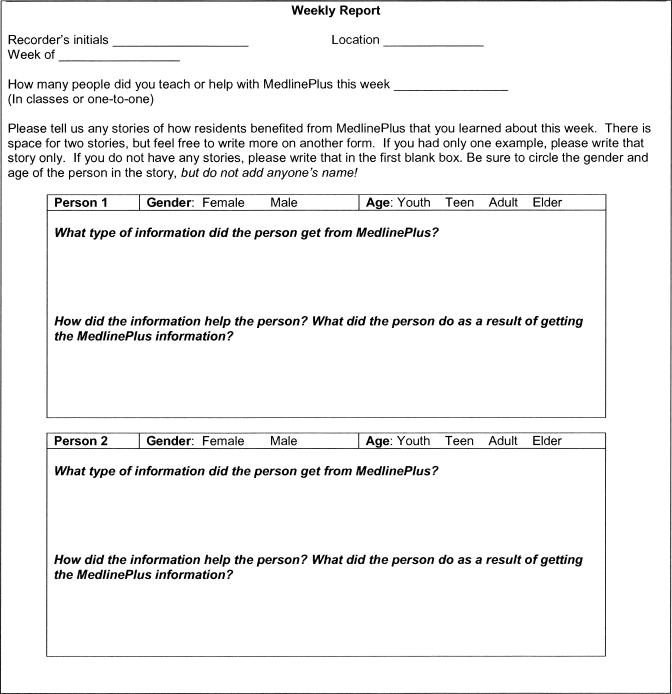

Unfortunately, the detail in qualitative methods can quickly become overwhelming. To simplify analysis, qualitative methods can be semi-structured. An excellent method is the story-based approach, where stakeholders are asked what important changes have come about because of their knowledge and use of the innovation [19]. Figure 1 illustrates a tool we designed to help promotoras at our community centers record how they helped residents and the results of such efforts. However, it is best to supplement the story-based approach with other methods (focus groups, key informant interviews, usage data, surveys) to validate findings. For example, we interviewed the promotoras monthly to get more stories, got updates on the residents they wrote about, and listened to their advice about how to increase usage of MedlinePlus in the community.

Figure 1.

“Story sheet”: a simple method for collecting ongoing stories of how outreach efforts may be affecting the community

Listed below are some broad questions that outcome methods could answer using examples from our story sheets, surveys, and key informant interviews.

Is the library resource being adopted by the CBO? Example: Cameron Park promotoras reported that residents come to their homes day and night to access MedlinePlus health information. Example: A promotora who works with a senior program used MedlinePlus to help seniors develop questions to ask doctors when they go to appointments.

Has introduction of the innovation helped the community empower the community members? In the health promotion literature, empowerment is related to increasing the control of individuals over their own lives. Community-based organizations can empower people by providing means that can help them make better decisions, critically assess their health situations, and strengthen relationships with other individuals and organizations in the community that can benefit them [20]. Example: Promotoras were particularly happy to have access to drug information in Spanish to help residents better understand side effects, safety for use with children, dosage schedules, and other prescription-related issues. Example: One grandmother at a training session researched information about juvenile diabetes so she could care for her granddaughter; she then printed information for the child's parents and her other grandparents, all of whom also cared for the child.

Did usage of the innovation spread beyond the target group? Example: High school students used MedlinePlus to access health information for themselves and their friends and family almost as often as they used it to do research for school projects. Example: Promotoras directed us to other community leaders who often assisted people in the community, such as local church leaders. One of our librarians helped a church leader put together MedlinePlus information for a church-based meeting.

Does the system incorporate the innovation as the organization changes and evolves? Example: When Texas A&M staff was able to secure laptops and wireless Internet cards for promotoras, our Cameron Park promotoras began helping people get MedlinePlus materials right at home. Example: The peer tutor program at the high school is self-sustaining. The high school librarians run the program and, in its third year, increased the number of peer tutors.

Has any part of the system changed because of the innovation? Example: Introduction of MedlinePlus into the high school changed the way teachers taught. Students started doing research their freshman year, rather than in their junior year. Also, the librarians' role at the school changed: rather than providing mostly technical support to student and staff, they became active members of curriculum teams, sometimes providing leadership in curriculum matters. Example: The promotoras have found that MedlinePlus not only provides immediate access to health information, but can be used as a triage tool. It helps them figure out who needs more immediate help in getting a doctor's appointment and who might be able to resolve his or her health complaint with an over-the-counter treatment.

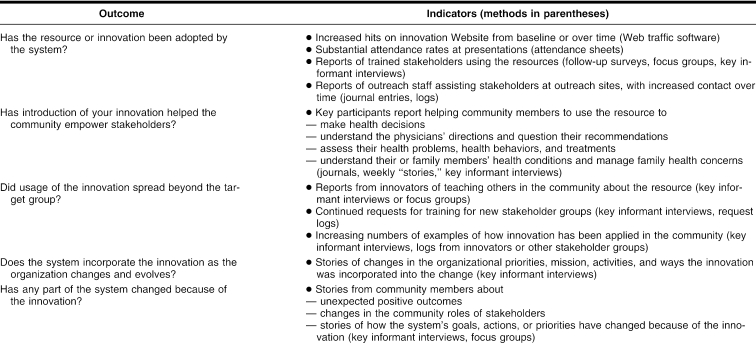

Table 5 lists the outcomes presented above, indicators that would relate to these outcomes, and methods for collecting outcome data.

Table 5 Evaluation of system-based outcomes

CONCLUSION

If one accepts that CBOs are complex adaptive systems, evaluation becomes an important guidance device. Methods that combine the efficiency of quantitative methods with the sensitivity of qualitative approaches are necessary to track unexpected changes and outcomes.

The evaluation approaches described in this paper are based on principles described in Eoyang and Berkas [7] for conducting evaluations in a complex adaptive system. They wrote that evaluation must (a) identify cause-and-effect relationships but track changes over time in such causal relationships; (b) evaluate and redesign the activities frequently (with stakeholder participation); (c) design simple evaluation procedures to inform action, communicate findings that people care about, and focus on “differences that make a difference”; and (d) monitor and use feedback loops to funnel evaluation findings to those in the system. The approaches discussed here also follow some of the principles of Patton's utilization-focused evaluation approach, which emphasizes data that is of immediate value to those implementing a program, generates feedback and discussion between implementers and consumers of the outreach project, and allows for constant refinement and revision of plans to meet the needs of those in the system [21].

When resources permit, evaluators are invaluable as team members. They can keep the evaluation methods on track and help outreach team members and CBO stakeholders understand and apply the evaluation findings. Their involvement throughout the project can integrate evaluation methods into the outreach project, increasing the team's ability to collect meaningful data and analyze it for program improvement.

Finally, if the focus is only on changes in individual participants without looking at system-level changes, dramatic effects may be missed. Any given individual may not show dramatic change, but, looking more broadly, dramatic results may be seen. Very sophisticated quantitative analyses (based on time series analysis) can be employed to show patterns of change. However, these methods can be expensive and technologically sophisticated, so they may not be feasible for typical health information outreach budgets. However, if the general goal is to understand the patterns of behavior in a system and adapt outreach activities to the system, the less precise measures presented here are likely to be adequate.

In fact, such methods are essential for success in the CBO environment. As portrayed here, evaluation is no longer just a requirement by external funding agencies to gauge the effectiveness of an information outreach project. Rather, evaluation is a necessary tool for providing effective outreach in the dynamic environments of community-based organizations.

Acknowledgments

The author recognizes and thanks the entire outreach team from the libraries at the Harlingen and San Antonio campuses of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio: Debra Warner, Virginia Bowden, FMLA, Evelyn Olivier, Jonquil Feldman, Graciela Reyna, and Mary Jo Dwyer. Thanks also to all our community partners at all four outreach sites who participated in these outreach activities. Special thanks to Elliot Siegel and Frederick Wood of NLM's Health Information Programs Development and to Catherine Burroughs of the Outreach Evaluation Resource Center, Pacific Northwest Regional Medical Library, University of Washington, for the guidance and management support they provided for our outreach projects.

APPENDIX

Community assessment question guide

The following guide presents the type of information the outreach team should gather when doing community assessment of potential outreach sites. This information can be gathered through a variety of methods, including surveys, interviews, focus groups, tours of community-based organization (CBO) sites, surveys, and review of organizational records.

Who are the primary contacts at the community center?

Describe the environment, i.e., anything that may affect the project. Anything that captures your attention should be noted.

-

Innovators and early adopters

Who in the community has the most interest in computers?

Who seems to be responsible for getting health care information to community members?

-

Relative advantage:

How are the innovators and early adopters getting health information now? Will MedlinePlus be easier or harder to use than their current approaches?

How are other community members getting health information?

-

Complexity:

What groups in the community have experience using the Internet?

What groups will have a difficult time using the computer or the Internet

-

Compatibility:

What groups in the community are now learning to use the computer?

Who in the community is involved in getting health information for family and other community members?

How do people feel about the health care information available to them?

-

Trialability:

Where can residents get computer access?

Describe the community's public technology resources: number of stations, hours of access, reliability of Internet service.

Is any type of training or assistance available to residents who want to learn to use the computers?

Are there any activities or classes in which outreach librarians can demonstrate or teach health information databases?

-

Observability:

What frustrates community members about getting health care information for themselves, family, or community?

After examining the health information databases we demonstrated, how do staff at the CBO or members of the community think they could use them?

Footnotes

* The outreach projects discussed in this paper were carried out in 2001–2003 and were funded by the National Library of Medicine under contract (#NO-1-LM-1-3515) with the Houston Academy of Medicine-Texas Medical Center Library.

† This paper is based on a presentation at the “Symposium on Community-based Health Information Outreach”; National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland; December 3, 2004.

REFERENCES

- Scherrer CS. Outreach to community organizations: the next consumer health frontier. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jul; 90(3):S285–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner DG, Olney CA, Wood FB, Hansen L, and Bowden VM. High school peer tutors teach MedlinePlus: a model for Hispanic outreach. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005 Apr; 93(2):S243–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Libraries. Final report: Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley Health Information Hispanic Outreach Project. [Web document]. Report prepared for the Office of Health Information Programs Development of the National Library of Medicine, 2004 Feb. [cited 8 Feb 2005]. <http://www.library.uthscsa.edu/rahc/outreach/pdf/FinalReport.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Watts DJ. Six degrees: the science of a connected age. New York, NY: Norton, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley MJ. Leadership and the new science: discovering order in a chaotic world. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Eoyang GH. Coping with chaos: seven simple rules. Cheyenne, WY: Lagumo, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Eoyang GH, Berkas TH. Evaluation in a complex adaptive system. [Web document]. 1998. [cited 8 Feb 2005]. <http://www.winternet.com/∼eoyang/EvalinCAS.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, and Stange KC. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998 May; 46(5):S369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Crabtree BF, and Stange KC. Practice jazz: understanding variation in family practices using complexity science. J Fam Pract. 2001 Oct; 50(10):S872–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WJ. Heaven's fractal net: retrieving lost visions in the humanities. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4th ed. New York, NY: Free Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs CM, Wood FB. Measuring the difference: guide to planning and evaluation health information outreach. Seattle, WA: National Network of Libraries of Medicine, Pacific Northwest Region; Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Charles P, Henner T. Evaluation from start to finish: incorporating comprehensive assessment into a training program for public health professionals. Health Prom Prac. 2004 Oct; 5(4):S362–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Agency for International Development, Center for Development Information and Evaluation. Conducting a participatory evaluation. [Web document]. Performance Monitoring and Evaluation (TIPS 1996 #1), The Agency. [cited 8 Feb 2005]. <http://www.dec.org/pdf_docs/pnabs539.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Sobo EJ, Simmes DR, Landsverk JA, and Kurtin PS. Rapid assessment with qualitative telephone interviews: lessons from an evaluation of California's Healthy Families programs & Medi-Cal for Children. Am J Eval. 2003 Sep; 24(3):S399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruvilla S, Joseph A. Identifying disability: comparing house-to-house survey and rapid rural appraisal. Health Policy Plan. 1999 Jun; 14(2):S182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WK Kellogg Foundation. Logic model development guide: using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation, and action (item #1209). [Web document]. Battle Creek, MI, 1 Dec 2001. [rev. Jan 2004; cited 8 Feb 2005]. <http://www.wkkf.org/Programming/ResourceOverview.aspx?CID=281&ID=3669>. [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman DM. Foundations of empowerment evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dart J, Davies RA. Dialogical story-based evaluation tool: the most significant change technique. Am J Eval. 2003 Jun; 24(2):S137–55. [Google Scholar]

- Laverack G, Labonte R. A planning framework for community empowerment goals within health promotion. Health Policy and Plan. 2000 Sep; 15(3):S255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Utilization-focused evaluation: the new century text. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]