Abstract

M-phase promoting factor is a complex of cdc2 and cyclin B that is regulated positively by cdc25 phosphatase and negatively by wee1 kinase. We isolated the wee1 gene promoter and found that it contains one AP-1 binding motif and is directly activated by the immediate early gene product c-Fos at cellular G1/S phase. In antigen-specific Th1 cells stimulated by antigen, transactivation of the c-fos and wee1 kinase genes occurred sequentially at G1/S, and the substrate of wee1 kinase, cdc2-Tyr15, was subsequently phosphorylated at late G1/S. Under prolonged expression of the c-fos gene, however, the amount of wee1 kinase was increased and its target cdc2 molecule was constitutively phosphorylated on its tyrosine residue, where Th1 cells went into aberrant mitosis. Thus, an immediate early gene product, c-Fos/AP-1, directly transactivates the wee1 kinase gene at G1/S. The transient increase in c-fos and wee1 kinase genes is likely to be responsible for preventing premature mitosis while the cells remain in the G1/S phase of the cell cycle.

Keywords: activator protein-1/c-Fos/G1/S phase/mitotic cell division/wee1 kinase

Introduction

c-fos is an immediate early gene that is expressed transiently in the G1 phase of the cell cycle after antigen stimulation (Shipp and Reinherz, 1987; Ullman et al., 1990). The gene product, c-Fos, interacts with members of the Jun family to form an activator protein-1 (AP-1) heterodimer (Angel and Karin, 1991). This heterodimer transactivates genes containing the consensus AP-1 motif TGA(G/C)TCA in their promoter region (Halazonetis et al., 1988; Nakabeppu et al., 1988), and plays an important role in inducing gene expression required for cell proliferation (Muegge et al., 1989; Kim et al., 1990). However, while progression of the cell cycle is known to be coordinated by a family of cyclin-dependent protein kinases (Morgan, 1995), the molecular target of the immediate early gene c-fos in cell cycle regulation remains unclear.

The role of c-Fos/AP-1 in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine gene expression, including that of several cytokines important in arthritis, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, is better understood (Rhoades et al., 1992; Serkkola and Hurme, 1993; Dendorfer et al., 1994). We have previously examined the role of c-Fos/AP-1 in tumor-like synovial overgrowth and rheumatoid joint destruction, and found that mutation of c-fos causes not only cellular overgrowth, but also a skewed immune response (Shiozawa et al., 1992, 1997; Kawasaki et al., 1999). In the present work, we show that expression of wee1 kinase, a kinase important for mitotic cell division, is increased in cells overexpressing the c-fos gene.

wee1 kinase inhibits mitotic cell division by inactivating the M-phase promoting factor (MPF). MPF is composed of cdc2 kinase and cyclin B, and specifically regulates the cellular G2/M transition (Nurse, 1990). In mammalian cells, cdc2 maintains more or less constant levels throughout the cell cycle (Draetta and Beach, 1988; Dalton, 1992), and gradually increases toward G2/M in T cells (Furukawa et al., 1990; Kim et al., 1992; Lucas et al., 1992). cdc2 forms a complex with cyclin B at the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle (Pines and Hunter, 1989). Following its association with cyclin B, cdc2 undergoes a series of phosphorylation events that modulate its kinase activity (Solomon, 1993). As mammalian cells progress towards mitosis, the concentration of cdc2– cyclin B complexes gradually increases. cdc2–cyclin B complexes can be rapidly activated by dephosphorylation of cdc2 at Thr14 and Tyr15 (Norbury et al., 1991), and negatively regulated by phosphorylation at Tyr15 (Gould and Nurse, 1989). Dephosphorylation of Thr 14 and Tyr 15 is catalyzed by cdc25 (Strausfeld et al., 1991), while phosphorylation of Tyr15 is catalyzed by wee1 kinase (Russell and Nurse, 1987; Parker et al., 1992).

Wee1 kinase activity is controlled by three mechanisms (Watanabe et al., 1995). First, as demonstrated in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, wee1 kinase activity is down-regulated during the M phase as a result of phosphorylation in its catalytic domain by nim1/cdr1 (Coleman et al., 1993; Parker et al., 1993; Wu and Russell, 1993). Secondly, wee1 levels decrease in M phase as a result of both decreased synthesis and increased degradation, the latter of which is mediated by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme cdc34 in Xenopus egg extracts (Michael and Newport, 1998). Finally, the synthesis of wee1 kinase has been shown to increase during S phase (Watanabe et al., 1995), although the mechanisms responsible for this increase have been unclear.

We show that there is one AP-1 binding motif in the wee1 promoter which is directly bound by c-Fos/AP-1 to transactivate the wee1 gene. Following receptor ligation in Th1 cells, upregulation of the c-fos and wee1 kinase genes occurs sequentially during the G1/S phase. When the c-fos gene was expressed for an abnormally prolonged period, Th1 cells shifted to a state with tetraploid DNA content (4C), a state in which wee1 kinase activity increases, leading to increased Tyr15 phosphorylation of its target cdc2 and consequent inhibition of mitosis. This suggests that c-Fos/AP-1 causes increased wee1 synthesis in the G1/S phase of the cell cycle. We discuss this result in the context of checkpoint controls for cellular DNA synthesis and mitosis.

Results

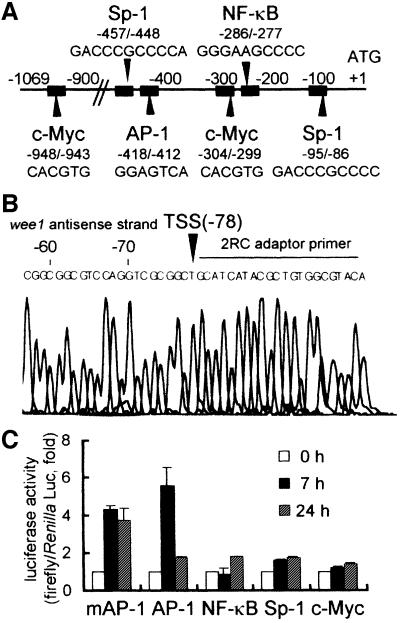

Identification of an AP-1 binding site in the mouse wee1 promoter

We isolated the 5′-flanking region of the mouse wee1 gene from genomic DNA by nested PCR using primers complementary to the sense strand of the published wee1 cDNA sequence (Honda et al., 1995). The resulting 1069 bp fragment was confirmed to be the 5′-flanking region of the murine wee1 gene by PCR with a sense primer that annealed to the newly isolated sequence and an antisense primer that annealed to a known exon of the wee1 gene (Figure 1A). A transcription start site was found 78 bp upstream of the ATG initiation codon (+1) using the oligonucleotide-capping method (Figure 1B). One AP-1 binding motif was found in the promoter region (–418/–412, GGAGTCA; Figure 1A), as well as one NF-κB (–286/–277), two Sp-1 (–457/–448, –95/–86) and two c-Myc (–948/–943, –304/–299) binding motifs. We tested which of these transcription motifs are involved in the transactivation of wee1 kinase gene by monitoring gene activation following anti-CD3 stimulation (Figure 1C). The 28-4 Th1 clone is a T-cell clone that is specifically activated by keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH). This clone was stimulated by anti-CD3 after transfection with one of several reporter constructs: one consisting of 5× AP-1 sites from the mouse wee1 promoter (GGAGTCA) fused to luciferase, 7× consensus AP-1 (TGAGTAA)– luciferase, 5× consensus NF-κB (GGGGACTTTCC)– luciferase, 4× consensus Sp1 (GGGGCGGGGC)–luciferase, or 6× consensus c-Myc (CACGTG)–luciferase. Luciferase reporter assays showed that both the AP-1 motif of mouse wee1 promoter and the consensus AP-1 motif were sufficient to mediate transactivation following anti-CD3 stimulation, with maximum activation observed 7 h after stimulation (Figure 1C). None of the other reporter constructs responded to anti-CD3 stimulation.

Fig. 1. Nucleotide sequence of the mouse wee1 gene promoter region. (A) Binding motifs for transcription factors are indicated by arrowheads and closed squares. These sequence data have been submitted to the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession No. AB024614. Nucleotide numbering is relative to +1 at the initiating ATG codon. (B) The transcription start site (TSS) of the wee1 kinase gene is indicated by an arrowhead. Nested adaptor primer 2RC is indicated by the horizontal line. (C) Trans-reporting assay. The 28-4 Th1 clone was transfected with the pGL3-Enhancer vector containing binding motifs in a promoter driving expression of the luciferase reporter gene: 5× AP-1 of mouse wee1 promoter (GGAGTCA)–luciferase (mAP-1); 7× consensus AP-1 (TGAGTAA)–luciferase (AP-1); 5× consensus NF-κB (GGGGACTTTCC)–luciferase (NF-κB); 4× consensus Sp1 (GGGGCGGGGC)–luciferase (Sp-1); or 6× consensus c-Myc (CACGTG)–luciferase (c-Myc). The 28-4 Th1 clone was stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb for 0, 7 and 24 h. Cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity (firefly/Renilla Luc) in a dual-luciferase reporter assay in which luciferase activity at 0 h was taken as 1. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three experiments.

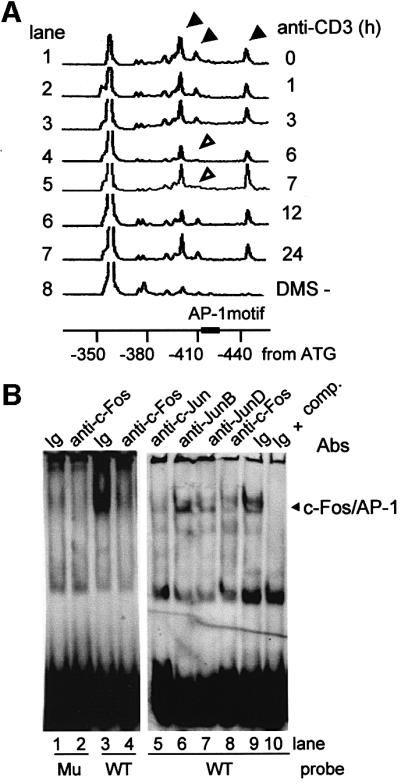

c-Fos/AP-1 binds to the wee1 promoter in vivo and in vitro

To examine protein binding to the AP-1 motif (–418/–412, GGAGTCA) of the mouse wee1 promoter in vivo, we performed an in vivo dimethyl sulfate (DMS) footprinting assay. DMS treatment of T cells caused cleavage of three G residues around the region of the AP-1 motif in the wee1 promoter: –442, –411 and –401 (Figure 2A, lane 1, solid arrowheads). These peaks were absent in the control DMS-untreated T cells (Figure 2A, lane 8). Following anti-CD3 treatment, the peak corresponding to –411 G diminished at 6 and 7 h (Figure 2A, lanes 4 and 5, open arrowheads), suggesting that this region was protected by binding of a protein, possibly AP-1, at the time when the transactivation through the AP-1 binding motif was maximum (Figure 1C). Binding to this motif (GGAGTCA) was examined in vitro by using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Binding to the wild-type AP-1 motif, but not a mutant motif (GGTGTTG), was observed in nuclear extracts from the 28-4 Th1 clone obtained 7 h after anti-CD3 stimulation (Figure 2B, lanes 1 and 3). The band obtained with the wild-type AP-1 motif was supershifted by anti-c-Fos antibody (Ab) (Figure 2B, lanes 4 and 8). It was found that c-Fos bound c-Jun to make an AP-1 heterodimer to bind the AP-1 motif of wee1 promoter (Figure 2B, lanes 5–7).

Fig. 2. c-Fos/AP-1 binding to wee1 promoter in vivo and in vitro. (A) In vivo DMS footprinting assay. The 28-4 Th1 clone stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb was treated with 0.1% DMS. Extracted DNA was cleaved by 1 M piperidine, and processed for linker-mediated PCR. 4,7,2′,7′-tetrachloro-6-carboxyfluorescein (TET)-labeled DNA was electrophoresed with TAMRA-labeled size standards on a 36 cm well-to-read gel (6% polyacrylamide–6 M urea) plate in an ABI377 at 3000 V for 2 h. Three peaks (arrowheads) indicated the G residues methylated by DMS. The open arrowheads indicate the disappearance of the –411 G peak. (B) EMSA for c-Fos/AP-1. The 28-4 Th1 clone was stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb. Nuclear extracts were obtained 7 h after stimulation, and assayed in EMSA using DIG-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides (–434/–400) containing wild-type (WT) or mutated (Mu) AP-1 binding motifs. The competition assay was performed by adding unlabeled oligonucleotides. Abs reactive against c-Fos, c-Jun, JunB or JunD were added for supershift experiments.

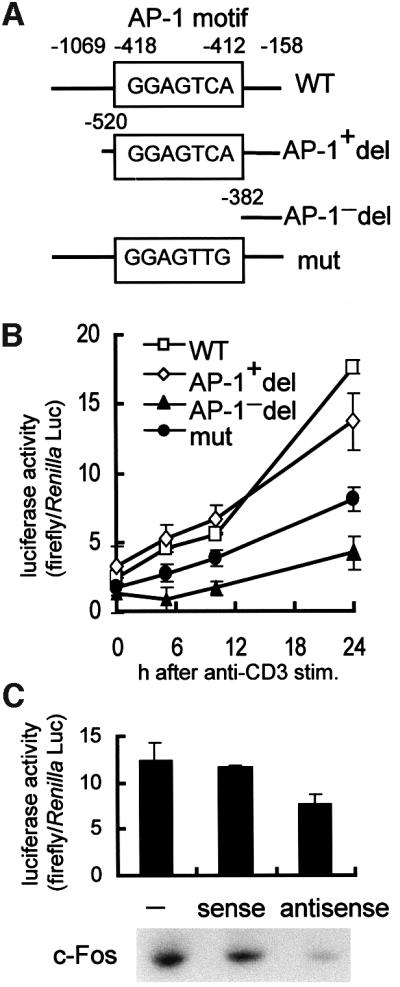

c-Fos/AP-1 directly transactivates wee1 kinase

To test whether or not binding of c-Fos/AP-1 to the promoter region of wee1 gene plays a major role in transactivation of the wee1 gene, we introduced deletion and site-directed mutations into the promoter. We transfected 28-4 Th1 cells with reporter gene constructs driven by the normal mouse wee1 promoter (WT, –1069/–158), a truncated promoter containing the AP-1 motif (AP-1+ del, –520/–158), a truncated promoter lacking the AP-1 motif (AP-1– del, –382/–158) or a promoter containing a mutated AP-1 motif (mut, –1069/–158; –418/–412, GGAGTTG) (Figure 3A). Both the wild-type (WT) and the truncated promoter containing the AP-1 motif (AP-1+ del) were activated in 28-4 Th1 clones after anti-CD3 stimulation. In contrast, activation of the promoter lacking the AP-1 motif (AP-1– del) or the promoter containing the mutated AP-1 motif (mut) was poor (Figure 3B), while activation of AP-1– del was almost completely inhibited, activation of mut was inhibited ∼50%, probably because mut contains binding motifs other than AP-1, especially Sp-1 (Pugh and Tjian, 1991). To study whether or not expression of the wee1 kinase gene required induction of c-Fos expression, c-fos antisense oligonucleotides were co-transfected with the wild-type wee1 promoter– luciferase reporter gene construct (WT) and the transfected cells were stimulated with anti-CD3. We found that transactivation of the wee1 kinase gene was specifically inhibited by c-fos antisense oligonucleotides (Figure 3C, upper panel). Western blot analysis also confirmed that expression of c-Fos protein was significantly decreased in cells transfected with c-fos antisense oligonucleotides (Figure 3C, lower panel). Furthermore, transactivation of 5× AP-1 (GGTGTCA)–luciferase was enhanced when the c-fos and c-jun genes were transiently co-expressed in COS-7 cells (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Luciferase reporter assay for mouse wee1 promoter activity. (A) Plasmid constructs of the wee1 promoter driving the luciferase reporter gene in pGL3-Enhancer vector. (B) Luciferase assay. Reporter plasmids were introduced into the 28-4 Th1 clone. After overnight culture, cells were stimulated by anti-CD3 mAb for 0, 5, 10 and 24 h. Lysates were assayed in a similar way as described in Figure 1. Each symbol represents the mean ± SD of three experiments. (C) Antisense oligonucleotide treatment. Luciferase reporter plasmid containing wild-type wee1 promoter (–1069/–158) was electroporated into the 28-4 Th1 clone with or without c-fos sense or antisense oligonucleotides. After overnight culture, cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb for 24 h in the case of luciferase assay (upper panel) and for 7 h in the case of western blotting (lower panel). Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three experiments.

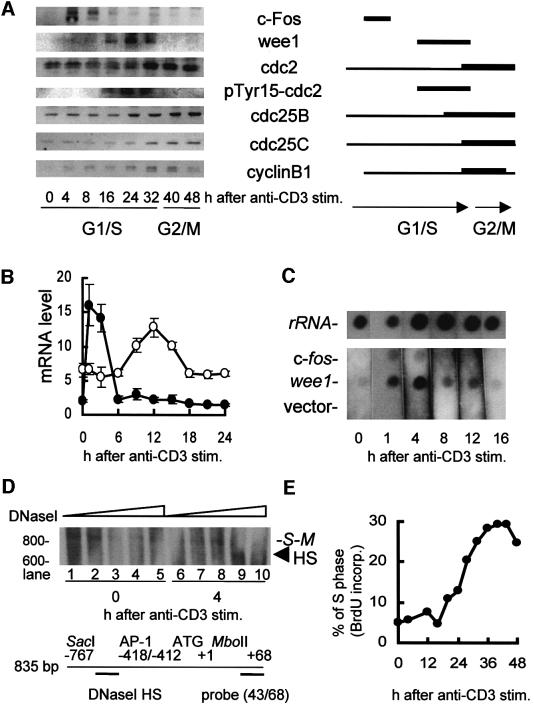

c-Fos transactivates the wee1 gene at G1/S

In rapidly dividing cells, including antigen-specific T cells, c-Fos/AP-1 expression normally increases transiently at early G1 phase of the cell cycle (Shipp and Reinherz, 1987; Ullman et al., 1990). Therefore, we studied the profile of induction of the wee1 kinase gene by c-Fos/AP-1 throughout the cell cycle. Western blotting showed that c-Fos increased at 4–8 h and the wee1 kinase increased at 16–32 h after anti-CD3 stimulation (Figure 4A), which corresponds to the G1/S phase of cell cycle (Figure 4E). The cdc2 existed at low levels until 24 h, and increased at 32–48 h after stimulation (Figure 4A). The Tyr15 phosphorylation of cdc2 was highest 16–32 h after stimulation. Phosphorylation of histone H1 was increased 32 h after stimulation (data not shown). The amount of cdc25B or cdc25C was increased 32 h after stimulation. Cyclin B was increased 32 h after stimulation (Figure 4A). A time course study of mRNA expression in 28-4 Th1 cells using an ABI7700 showed that c-fos mRNA and wee1 mRNA increased in 28-4 Th1 cells between 1–3 and ∼12 h after anti-CD3 stimulation, returning to a basal level within 18 h after stimulation (Figure 4B). In a nuclear run-on assay, c-fos was transcribed 1 h (G1 phase) after anti-CD3 stimulation, and the wee1 kinase gene was also transcribed during the G1 phase at 4 h (Figure 4C and E). These results show that transactivation of the c-fos and wee1 genes is sequential, and occurs within the G1/S phase of the cell cycle.

Fig. 4. Time course of the expression of c-fos and wee1 kinase genes. (A) Western blot analyses. The extracts of 28-4 Th1 clone were obtained after anti-CD3 mAb treatment. SDS–PAGE (7.5–10%) and western blot visualization with Abs reactive against c-Fos, wee1, cdc2, phospho (p) Tyr15-cdc2, cdc25B, cdc25C or cyclin B (left panel). Schematic representation of gene expression (right panel). (B) Quantitative RT–PCR by ABI7700 of 28-4 Th1 clone mRNA after anti-CD3 stimulation. The amount of c-fos and wee1 mRNAs and 18S rRNA was quantified. The levels of c-fos (closed circles) and wee1 (open circles) were divided by that of 18S rRNA for normalization. Each circle represents the mean ± SD of three experiments. (C) Nuclear run-on assay. Nuclei prepared from the 28-4 Th1 clone after anti-CD3 stimulation were incubated with [α-32P]UTP. Run-on transcripts were hybridized to 10 µg of mouse 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), mouse c-fos cDNA (c-fos), mouse wee1 cDNA (wee1) or control vector. (D) DNase I HS assay of the mouse wee1 promoter region. Nuclei of the 28-4 Th1 clones obtained 0 h (lanes 1–5) or 4 h (lanes 6–10) after anti-CD3 stimulation were incubated with DNase I (lanes 1 and 6, 0 U/ml; lanes 2 and 7, 0.01 U/ml; lanes 3 and 8, 0.1 U/ml; lanes 4 and 9, 1 U/ml; lanes 5 and 10, 10 U/ml) for 10 min. Purified genomic DNA was completely digested by SacI and MboII, electrophoresed on 2.5% agarose gel, and transferred to nylon membrane. Filter was hybridized to Fl-end-labeled oligonucleotide probe (43/68) for mouse wee1 DNA, and visualized by alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-Fl Ab and chemiluminescence. (E) Cell cycle progression of the 28-4 Th1 clone. DNA synthesis of the 28-4 Th1 clone after anti-CD3 stimulation was measured by BrdU incorporation.

We next examined the state of the chromatin surrounding the chromosomal AP-1 site in the wee1 promoter during the G1/S phase. Nuclei obtained 4 h (G1 phase) after anti-CD3 stimulation of 28-4 Th1 cells were analyzed by a DNase I hypersensitive site (HS) assay that specifically detects open chromatin structure in expressed genes (Gross and Garrad, 1988; Kornberg and Lorch, 1991). While an expected band of <835 bp was undetectable in unstimulated 28-4 Th1 cells after treatment with 1 U/ml DNase I, an ∼600 bp band gradually emerged in the cells stimulated with anti-CD3 Ab (Figure 4D, compare lanes 4 and 9). Since the probe (43/68) bound to the genomic DNA region spanning the ATG initiation codon up to +68 bp of the wee1 genome, the inducible DNase I HS was assigned to the position ∼530 bp upstream of the ATG, placing it precisely within the region of the AP-1 binding motif. Additionally, constitutive DNase I HS was detected at the position ∼330 bp upstream of the ATG (data not shown).

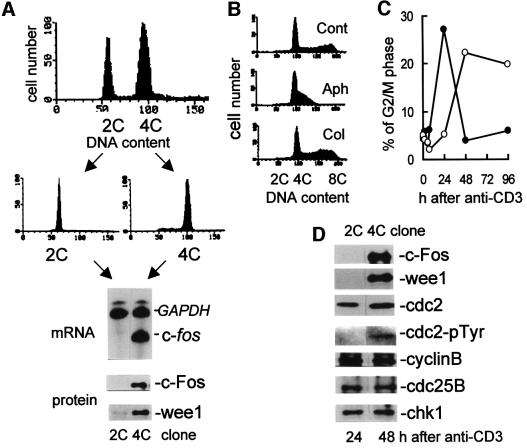

Transient increase in c-fos is a prerequisite for normal cell cycle progression

To study whether or not direct activation of the wee1 gene by an immediate early gene product, c-Fos, at G1/S phase was required for normal cell cycle progression, we transfected 28-4 T cells with c-fos-expressing 75/15pH8 vector, and stable transformants were obtained (Kawasaki et al., 1999). After the transformants had been cultured for 1 month, we noticed an increasing number of the cells with tetraploid DNA content (4C), as determined by propidium iodide staining. Of the cells cultured for longer periods (>4 months), ∼50% shifted to 4C (Figure 5A, upper panel). This shift to the 4C state was reproduced in >10 experiments, and was not observed in cells transfected with the control pH8 vector.

Fig. 5. Profile of c-fos-expressing antigen-specific Th1 cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of the c-fos-expressing 75/15pH8 clone to measure cellular DNA content by propidium iodide staining. The 28-4 Th1 cells were transfected with c-fos-expressing 75/15pH8 vector and cultured for 6 months (upper panel). Clones residing in 2C or 4C were isolated by limiting dilution technique (middle panels). RNase protection assay to detect c-fos mRNA at the quiescent phase (9 days after antigen stimulation) (lower panel). RNA was hybridized to probes protecting 250 nucleotides of the mouse c-fos mRNA or 316 nucleotides of the mouse GAPDH mRNA, followed by electrophoresis on 5% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel. Western blot of cell extracts obtained 9 days after antigen stimulation (lower panel). (B) Cell cycle progression of 4C clone stimulated with anti-CD3 Ab for 48 h in the absence or presence of aphidicolin or colcemid. DNA content measured by flow cytometry. (C) Percentage of G2/M phase cells in the population of 2C (closed circles) or 4C (open circles) clones after anti-CD3 stimulation. (D) Western blot analysis of the cell extracts obtained 24 or 48 h after anti-CD3 treatment. Tyrosine phosphorylation of cdc2 was detected by immunopreciptation with anti-cdc2 Ab and protein A–agarose beads, followed by western blotting using anti-pTyr Ab.

We subcloned each 2C and 4C clone by limiting dilution (Figure 5A, middle panel). Using an RNase protection assay, we quantitated c-fos mRNA expression 9 days following antigen stimulation (quiescent phase) and found that the 4C clones expressed higher amounts of c-fos mRNA than the 2C clones (Figure 5A). Western blot analysis confirmed that the amount of both the c-Fos and wee1 proteins was significantly increased in the 4C clones (Figure 5A, lower panel). Thus, the Th1 cells go into aberrant mitosis when expression of an immediate early c-fos gene was not switched off.

Forty-eight hours after anti-CD3 treatment, the 4C clones shifted to an 8C DNA content (Figure 5B, upper panel). This shift was blocked by aphidicolin, a DNA synthesis inhibitor, suggesting that the shift from 4C to 8C required DNA synthesis (Figure 5B, middle panel). Anti-CD3 stimulation of cells in the presence of colcemid induced a shift from 4C to 8C, and cells remained in this state, indicating that these 8C cells are in the M phase of the cell cycle (Figure 5B, lower panel). We therefore assume that the 4C clones in resting state reside in G1, and are formed when 2C cells undergo S phase DNA replication without intervening mitosis. Entrance into G2/M was also significantly delayed in the 4C clones after anti-CD3 stimulation: whereas the 2C clones entered G2/M normally at 24 h, the 4C clones entered G2/M at 48 h after stimulation and remained there until 96 h (Figure 5C). We therefore compared the 2C and 4C clones for expression of cell cycle regulators known to act primarily in the G2/M phase. Western blot analysis showed that expression of c-Fos and wee1 was higher in the 4C clones, while the peak levels of cyclin B, cdc2, cdc25B and chk1 were similar between the 2C and 4C clones in the G2/M phase (Figure 5D). Since wee1 is a tyrosine-protein kinase that specifically phosphorylates cdc2 at Tyr15, we immunoprecipitated cdc2 and analyzed phosphotyrosine content by western blot analysis with anti-cdc2-pTyr Ab. Tyrosine phosphorylation of cdc2 was detected only in the 4C clones at the G2/M phase (Figure 5D).

Discussion

We cloned and sequenced the promoter region of the mouse wee1 kinase gene up to –1069 relative to the ATG. The promoter did not contain a consensus TATA box similar to that found in the promoters of cyclin A (Henglein et al., 1994), cyclin D1 (Philipp et al., 1994) or other cell cycle regulators (Azizkhan et al., 1993). However, we did identify one AP-1 binding motif in the wee1 promoter region (–418/–412) with the sequence GGAGTCA, which is one base different from the consensus AP-1 binding motif TGAGTCA. We showed that c-Fos, induced by antigen stimulation, bound c-Jun to make an AP-1 heterodimer to bind this putative AP-1 motif in vivo and in vitro. Similar one-base deviations from the consensus AP-1 motif have been shown to be functional, e.g. the motif CGAGTCA in the human α2 (I) collagen promoter (Chung et al., 1996). We also found that consensus motifs other than AP-1 did not contribute significantly to the transactivation of wee1 kinase following anti-CD3 stimulation. Site-directed mutagenesis and antisense experiments showed that both the presence of an intact AP-1 binding motif and the induction of c-Fos were required for transactivation of the mouse wee1 kinase gene. Transactivation of the c-fos and wee1 kinase genes occurred sequentially during the G1/S phase, and the chromatin structure around the AP-1 motif existed in an open conformation at the G1/S phase, as revealed by DNaseI HS analysis. Thus, c-Fos/AP-1 directly transactivates the wee1 kinase gene during the G1/S phase following antigen stimulation.

Under prolonged expression of c-fos gene, however, expression of the wee1 kinase gene was sustained at higher levels in Th1 cells. Such T cells were found to have a 4C DNA content and to be arrested in the cell cycle, but to progress to an 8C state after receptor ligation. This shift to 8C was blocked by the DNA synthesis inhibitor aphidicolin, indicating that DNA synthesis is required for entrance into 8C. In contrast, receptor ligation in the presence of colcemid caused 4C clones to shift to the state with 8C DNA content, and arrest in this state. Thus, the 8C and 4C cells are assumed to represent the cells in the M and G1 phases of the cell cycle, respectively. Normally, c-Fos expression increases transiently in early G1. However, when the expression of c-fos is prolonged, either experimentally or as a result of disease conditions such as tumors (Miller et al., 1984; Wang et al., 1991) or the tumor-like cell growth seen in arthritis (Shiozawa et al., 1992, 1997), the wee1 kinase activity was increased and its substrate cdc2 was inactivated by phosphorylation at Tyr15, and the cells went into aberrant mitosis. This was indeed the case for the Th1 cells overexpressing c-fos in the present study.

These findings are consistent with those of Broek et al. (1991), who showed that S.pombe underwent DNA duplication twice in one cell cycle when cdc2 was physically disrupted. Correa-Bordes and Nurse (1995) showed that expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p25rum1 increases in early G1 and inhibits p34cdc2/p56cdc13, thereby preventing premature mitosis when the cells are in G1/S. Human herpesvirus 7 infection induces significant cell cycle abnormalities in T cells, including the accumulation of polyploid cells in G2/M, which is due to inactivation of cdc2 (Secchiero et al., 1998). Mega karyocytes normally mature to polyploid cells as a result of DNA replication proceeding in the absence of mitosis, a process called endomitosis. This polyploidization of megakaryocytes was shown to be caused by inactivation of cyclin B1-dependent cdc2 kinase (Zhang et al., 1996), further supporting the idea that cells go into aberrant mitosis and remain in the G2/M phase when cdc2 is continuously inactivated. Collectively, these findings suggest that a transient increase in c-Fos and wee1 kinase expression at G1/S is required for normal cell cycle progression, and that aberrant mitosis can result if the expression of these genes is not subsequently down-regulated.

cdc25 has been implicated in the checkpoint control that prevents initiation of mitosis in cells before DNA replication is complete (Enoch and Nurse, 1990). However, O’Connell et al. (1997) have shown that wee1 kinase, which is phosphorylated by chk1, may also be important in the G2 checkpoint. cdc25 appears to function to promote the rapid and efficient cell cycle progression through G2/M, while the wee1 kinase seems more important in the overall control of mitosis. cdc25 has been shown to be up-regulated via a positive feedback mechanism in which cdc25 is phosphorylated by kinases including cdc2/cyclin B, and in turn stimulates cdc2/cyclin B activity (Hoffmann et al., 1993). In the present study, we observed that expression of either cdc25 or chk1 was not increased in the 4C clones, suggesting that the inhibition of mitotic cell division observed in the 4C clones was unlikely to be due to increased expression of cdc25 or chk1.

Previous studies have shown that both the amount and the activity of wee1 kinase are elevated during the S phase, and both decrease rapidly as the cells enter the M phase (Watanabe et al., 1995; Michael and Newport, 1998). Our antigen-specific Th1 cells also behaved as such after receptor ligation. Michael and Newport (1998) showed that proteolytic degradation of wee1 kinase is required for the timely initiation of mitosis. Since degradation of wee1 kinase is inhibited when DNA replication is blocked, these authors speculated that a factor which is unknown may be responsible for maintaining elevated wee1 expression during DNA duplication and prior to entry into the M phase. We propose that this factor is c-Fos/AP-1, a direct transactivator of the wee1 gene, and that c-Fos/AP-1 acts to prevent premature entry of G1/S cells into G2/M.

In summary, c-Fos/AP-1 directly transactivates the wee1 kinase gene during the G1/S phase following antigen stimulation in Th1 cells, and the resulting increase in wee1 kinase activity is likely to be responsible for preventing premature mitosis while antigen-specific Th1 cells are in the G1/S phase of the cell cycle. We have an impression that c-Fos/AP-1 and wee1 kinase act as a brake to halt cellular G2/M transition in the face of G1 progression, and c-Fos/AP-1, on the other hand, acts as an accelerator to drive cellular machines to pass though G1/S efficiently. Cells will arrest at G1 when an immediate early c-fos gene is not transcribed (Nishikura and Murray, 1987; Riabowol et al., 1988).

Materials and methods

Cells

The KLH-specific mouse CD4 Th1 clone 28-4 (Asano and Tada, 1989) and antigen-specific c-fos-expressing T-cell transformant 75/15pH8 were maintained as described (Kawasaki et al., 1999).

Isolation of the mouse wee1 promoter

The promoter of the mouse wee1 gene was isolated by nested PCR (GenomeWalker; Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The walking adaptor was ligated to the genomic DNA fragments digested by EcoRI, ScaI, DraI, PvuII or SspI. Primary PCR was conducted in a 25 µl reaction containing 2.5 mM MgCl2, 400 µM each dNTP, 1× LA Buffer (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), 6% DMSO, 3% glycerol, 1.25 U of LA Taq DNA polymerase (Takara), 200 nM adaptor sense primer (5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′), 200 nM wee1 gene-specific antisense primer (–168/–139; 5′-CTGCGCGGCGGCAACTCCGAGGCCCGTCAA-3′) and 50 ng of adapter-ligated genomic DNA (Clontech) at 94°C for 20 s and 68°C for 5 min for 40 cycles. Secondary PCR used nested adaptor primer (5′-ACTATAGGGCACGCGTGGT-3′) and nested wee1-specific antisense primer Mb2. Subcloned pT7Blue vector was confirmed to contain wee1 gene by sequencing. The transcription start site was determined by the oligonucleotide-capping method (Maruyama and Sugano, 1994). Primary PCR was conducted in a 25 µl reaction containing 400 µM each dNTP, 1× GCII Buffer (Takara), 1.25 U of LA Taq DNA polymerase, 200 nM adaptor sense primer 1RC (5′-CAAGGTACGCCACAGCGTATG-3′), 200 nM wee1 gene-specific antisense primer (265/284; 5′-AGCAGCAAGTCGTCCTCCAG-3′) and 1 µl of cap site cDNA from mouse kidney (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan) at 95°C for 20 s, 50°C for 20 s and 72°C for 5 min for 35 cycles. Secondary PCR used nested adaptor primer 2RC (5′-GTACGCCACAGCGTATGATGC-3′) and nested wee1-specific antisense primer (170/189; 5′-AGAAGGCAGGGGGCGAATCCG-3′). The PCR products were extracted from the gel and directly sequenced.

Plasmids

The wee1 promoter (–1069/–158) was subcloned in the pT7Blue vector (Novagen, Madison, WI), digested by SalI and BamHI, and subcloned into the pGL3-Enhancer vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to generate a firefly luciferase reporter (pwee1WT-luc). The –520 deletion containing the AP-1 motif was constructed using sense primer (–502/–501; 5′-TAAACATAGACTCTGGGTGG-3′) and antisense primer M2b (–187/–158; 5′-AGGCCCGTCAAGCTCACGACGGGGCGACGG-3′). The –382 deletion lacking the AP-1 motif was constructed using sense primer (–382/–356; 5′-TTCCTCCCCCGTGGGCT-3′) and antisense primer M2b. Reference +1 was the initiating ATG codon. For site-directed mutagenesis (Kunkel, 1985), a 50 µl reaction containing 40 µM each dNTP, 1× reaction buffer, 2.5 U of Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), 125 ng of sense primer (5′-GTGGGGCGGAGTTGGCGAGTTCCCGC-3′), 125 ng of antisense primer (5′-GCGGGAACTCGCCAACTCCGCCCCCAC-3′) and 50 ng of pwee1WT-luc was carried out at 95°C for 30 s, followed by amplification at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min and 68°C for 2 min for 18 cycles. Ten units of DpnI were added to each amplification reaction to digest non-mutated DNA. Luciferase reporter genes containing 5× AP-1 motif (GGAGTCA) of the mouse wee1 promoter, 4× consensus Sp1 motif (GGGGCGGGGC) or 6× consensus c-Myc motif (CACGTG) were constructed in pGL3-Enhancer vectors. 7× pAP1-luc plasmid (Stratagene) or 5× pNF-κB-luc plasmid (Stratagene) was used as consensus AP-1 or NF-κB motifs. Mouse pcDNA-c-fos and pcDNA-c-jun expression vectors were constructed from pYN3181 and pJac1 plasmids (Dr Nakabeppu, Kyushu University).

Transient transfection

We transfected the 28-4 Th1 clone (1 × 107) isolated 9 days after antigen stimulation with 40 µg of pGL3-Enhancer vector containing various wee1 promoters using a Bio-Rad electroporator (200 V, 975 µF) in 0.4 ml of RPMI supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS). After overnight culture, cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 monoclonal Ab (mAb). As an internal control for transfection efficiency, 2 µg of pRL-TK (Promega) containing herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter in the upstream of Renilla luciferase were co-transfected.

Antisense oligonucleotides

Sense and antisense phosphorothioate analogs (–6/15) of c-fos mRNA including the ATG (Ivanov and Nikolic-Zugic, 1997) consisted of the sequences 5′-TCGACCATGATGTTCTCGGGT-3′ and 5′-ACCCGAGAACATCATGGTCGA-3′, respectively. They (1 µg) were transfected into the 28-4 Th1 clone by electroporation. Cells were cultured overnight and then stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb (5 µg/ml; 145-2C11; Cedarlane, Ontario, Canada) coated on 24-well plates. Oligonucleotides were also added just prior to anti-CD3 stimulation.

Luciferase assay

Cell lysates (20 µl) were assayed using a dual-luciferase reporter assay (Promega) in Luminoskan (Labsystems, Tokyo, Japan), the activity of firefly luciferase being divided by the activity of Renilla luciferase (Mitsuda et al., 1997).

In vivo DMS footprinting

The 28-4 Th1 clone (1 × 107) stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb was suspended in RPMI medium containing 10% FCS and 0.1% DMS (Pfeifer et al., 1990). Nuclei were isolated, and DNA was purified by reaction with 300 µg/ml proteinase K, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 25 mM EDTA and 0.2% SDS at 37°C for 3 h (Wijnholds et al., 1988), and dissolved in 1 M piperidine. Strand scission reaction was performed at 90°C for 30 min. DNA samples were prepared for linker-mediated PCR (LMPCR) (Garrity and Wold, 1992) with the following modifications. A 30 µl reaction containing 40 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.9, 5 mM MgSO4, 0.01% gelatin, 0.3 pmol wee1 gene-specific primer1 (–354/–337; 5′-GGTTTGAAAAAACAGGGA-3′), 240 µM each dNTP, 1 U of Vent polymerase (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA) and DNA (2 µg) was carried out at 95°C for 5 min, 50°C for 30 min and 76°C for 10 min. This was mixed with 45 µl of ligation solution containing 188 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 14 mM MgCl2, 33 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 0.008% bovine serum albumin, 1.7 mM ATP, 100 pmol unidirectional linker (LMPCR1, 5′-GCGGTGACCCGGGAGATCTGAATTC-3′; LMPCR2, 5′-GAATTCAGATC-3′) and 4.5 U of T4 DNA ligase (Promega), and incubated at 17°C overnight. Purified DNA was amplified in a 100 µl reaction containing 40 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.9, 5 mM MgSO4, 0.01% gelatin, 0.01% Triton X-100, 670 µM each dNTP, 10 pmol wee1-specific primer2 (–360/–344; 5′-GCGCCCTCCCTGTTTTT-3′), 10 pmol linker primer LMPCR1 and 3 U of Vent polymerase at 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min and 76°C for 3 min for 18 cycles. Five microliters of labeling mixture containing 40 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.9, 5 mM MgSO4, 0.01% gelatin, 0.01% Triton X-100, 2 mM each dNTP, 2.3 pmol TET-labeled wee1-specific primer3 (–366/–344; 5′-TACGTCGCGCCCTCCCTGTTTTT-3′) and 1 U of Vent polymerase were added. The labeling reaction was carried out at 95°C for 4 min, 58°C for 2 min and 76°C for 10 min for two cycles. Labeled DNA was electrophoresed at 3000 V for 2 h in an ABI377 (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT). The DNA fragment peaks were identified by GENESCAN (version 2.0.2) software (Perkin Elmer), and were 25 nucleotides longer than the original footprinting products because of the 25 nucleotide linker.

EMSA

Nuclear extract (5 µg), incubated for 30 min with 0.5 pmol of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled oligonucleotide probes, was run on a 4% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane, and visualized by alkaline phosphatase-labeled F(ab)2 anti-DIG Ab and chemiluminescence reaction (Kawasaki et al., 1999). The double-stranded AP-1 motif (–434/–400) of the mouse wee1 promoter was 5′-GCCTAGGCTGTGGGGCGGAGTCAGCGAGTTCCC-3′ and 5′-GCGGGAACTCGCTGACTCCGCCCCACAGCCTAG-3′. Mutated AP-1 motif was 5′-GCC TAGGCTGTGGGGCGGAGTTGGCGAGTTCCC-3′ and 5′-GCGGGA ACTCGCCAACTCCGCCCCACAGCCTAG-3′. Non-labeled oligonucleotides (50 pmol) were added as competitor. Supershift was performed by adding 0.5 µg of anti-c-Fos Ab (sc-52; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-c-Jun Ab (PC-06; Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., La Jolla, CA), JunB (sc-046; Santa Cruz), JunD (sc-047; Santa Cruz) or normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz).

Immunoprecipitation

Two hundred micrograms of protein in 200 µl of lysis buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)] were incubated with anti-cdc2 Ab (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) at 4°C for 3 h, followed by reaction with protein A–agarose beads (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) at 4°C overnight. After heating at 95°C for 5 min, supernatant was separated by 12% SDS–PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane. The membrane was then incubated either with biotin-conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine mAb (4G10; Upstate Biotechnology) or anti-cdc2 Ab (Upstate Biotechnology), followed by reaction with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin (Upstate Biotechnology) or HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit Ig Ab (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and chemiluminescence.

Western blotting

The 28-4 Th1 cells (5 × 106) stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb were suspended in 500 µl of hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 3 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 1 mM PMSF) on ice for 10 min. The nuclear fraction was precipitated by centrifugation at 10 000 g for 1 min, and dissolved in 100 µl of RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Na3VO4). Fifty micrograms of protein were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) as described (Kawasaki et al., 1999). The membrane was incubated with anti-c-Fos Ab (sc-52; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-cyclin B1 Ab (sc-752; Santa Cruz), anti-cdc2 Ab (06-194; Upstate Biotechnology), anti-phospho-Tyr15-cdc2 Ab (C0228; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), anti-wee1 Ab (KAP-CC005E; StressGen Biotechnologies Corp., Victoria, BC, Canada), anti-cdc25B Ab (sc-326; Santa Cruz), anti-cdc25C Ab (sc-327; Santa Cruz) or anti-chk1 Ab (sc-7233; Santa Cluz) for 2 h, followed by reaction with HRP-conjugated Ab and enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

RNase protection assay

Total RNA was prepared from T cells 9 days after antigen stimulation using the RNeasy total RNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Biotinylated antisense probe protecting 250 nucleotides of the mouse c-fos mRNA was transcribed from the pTRI-c-fos/exon4-Mouse plasmid (Ambion, Austin, TX) using SP6 RNA polymerase. Biotinylated antisense probe protecting 316 nucleotides of the mouse GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) mRNA was transcribed from the pTRI-GAPDH-Mouse plasmid (Ambion). Total RNA (10 µg) was hybridized with these probes, followed by digestion with RNase A (5 µg/ml) and RNase T1 (100 U/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. The protected fragments were electrophoresed, transferred to positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer), and visualized by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin and chemiluminescence (Tropix, Bedford, MA).

Quantitative RT–PCR

mRNA was quantified by RT–PCR using TaqMan Gold RT–PCR reagents in an ABI PRISM 7700 (Perkin Elmer) (Gibson et al., 1996; Heid et al., 1996). The primers and TaqMan probes were: 5′-ACTGAGATTGCCAATCTGCT-3′ (forward), 5′-GGCAGACCTCCAGTCAAAT-3′ (reverse) and 5′-CTGCAAGATCCCCGATGACCTT-3′ (TaqMan probe) for c-fos; 5′-GAAAGAACTCAAGAAAGCCC-3′ (forward), 5′-ATATAGTAAGGCTGACAGAGCG-3′ (reverse) and 5′-AGTGCCCGTTCCTCAGCTGCAA-3′ (TaqMan) for wee1; and 5′-GGTTGATCCTGCCAGTAGCAT-3′ (forward), 5′-ATCCAAGTAGGAGAGGAGCGAG-3′ (reverse) and 5′-TAAGTACGCACGGCCGGTACAGTGAA-3′ (TaqMan) for 18S rRNA. A 100 µl reaction containing 5.5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM each dNTP, 1× TaqMan RT Buffer, 2.5 µM random hexamer, 0.4 U/µl RNase inhibitor, 1.25 U/µl MultiScribe reverse transcriptase and 100 ng of total RNA was carried out at 25°C for 2 min, 48°C for 30 min and 95°C for 5 min. Fifty microliters of the RT solution were mixed with 5.5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM dATP, 200 µM dCTP, 200 µM dGTP, 400 µM dUTP, 0.01 U/µl AmpErase uracil N-glycosylase, 1× TaqMan Buffer A, 0.025 U/µl AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase and 200 nM each forward and reverse primers. The mixture was amplified at 95°C for 20 s and at 60°C for 1 min for 50 cycles.

Nuclear run-on assay

Nuclei of 28-4 Th1 cells (1 × 107) stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb were collected and stored in nuclei freezing buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 5 mM MgCl2, 40% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA) at –70°C. Nuclei were incubated with [α-32P]UTP (>3000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) (Greenberg and Ziff, 1984), and run-on transcripts were hybridized to 10 µg of denatured plasmids pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), mouse c-fos cDNA (pcDNA-c-fos), mouse wee1 cDNA (pcDNA-wee1) or mouse 18S rRNA (pcDNA-ribosomal RNA). Plasmids were denatured in 0.1 M NaCl for 30 min at room temperature, neutralized with 6× SSC and dot-blotted onto nylon membrane. After incubation for 48 h, membrane was washed and reacted with 10 µg/ml RNaseA at 37°C for 30 min. Dried filters were subjected to autoradiography.

DNaseI HS analysis

Nuclei of the 28-4 Th1 clone (1 × 107) stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb were collected and resuspended in 200 µl of DNase I digestion buffer (60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 15 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM CaCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT), followed by incubation with DNase I (Nippon Gene) on ice for 10 min (Matsukawa et al., 1997). After adding 10 mM EDTA, nuclei were lysed at 37°C overnight and 10 µg of genomic DNA were completely digested with SacI and MboII. The DNA was electrophoresed and transferred to nylon membrane. Filter was hybridized to fluorescein (Fl)-end-labeled mouse wee1 probe (43/68; 5′-GTAGGAGCCGCTTACAGTCTGCGGCA-3′) and visualized by applying alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-Fl Ab and chemiluminescence reaction.

Cell cycle assay

Cellular DNA content was measured by Cycle TEST PLUS (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) using FACStarPLUS and FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). Cells (1 × 106) were incubated with trypsin at room temperature for 10 min, and with trypsin inhibitor and RNase A at room temperature for 10 min, followed by staining with propidium iodide and spermine tetrahydrochloride (Vindelov et al., 1983). Fluorescence intensity was measured in a FACSterPLUS (Becton Dikinson). To measure DNA synthesis, bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; 10 µM) was added and incubated for 30 min. Cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and reacted with 1.5 M HCl, followed by neutralization with 0.1 M Na2B4O7. Specimens were incubated with anti-BrdU Ab (PharMingen, San Diego, CA), followed by the reaction with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse Ig Ab (PharMingen). After RNase treatment, cells were stained with propidium iodide (5 µg/ml) and analyzed by FACSCalibur.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Y.Nakabeppu, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, for pYN3181 (c-fos) and pJac1 (c-jun) plasmids, and Dr H.Yasuda, Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Science, Tokyo, Japan, for mouse wee1 kinase cDNA. We also thank Dr M.Lamphier for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by grant-in-aid for scientific research to S.S. (B) 07557228, (B) 08457153, (B) 09470127 and (B) 11557026 of the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture.

References

- Angel P. and Karin,M. (1991) The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1072, 129–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano T. and Tada,T. (1989) Generation of T cell repertoire. Two distinct mechanisms for generation of T suppressor cells, T helper cells and T augmenting cells. J. Immunol., 142, 365–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizkhan J.C., Jensen,D.E., Pierce,A.J. and Wade,M. (1993) Transcription from TATA-less promoters: dihydrofolate reductase as a model. Crit. Rev. Euka r yot. Gene Expr., 3, 229–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broek D., Bartlett,R., Crawford,K. and Nurse,P. (1991) Involvement of p34cdc2 in establishing the dependency of S phase on mitosis. Nature, 349, 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K.Y., Agawal,A., Uitto,J. and Mauviel,A. (1996) An AP-1 binding sequence is essential for regulation of the human α(I) collagen (COL1A2) promoter activity by transforming growth factor-β. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 3272–3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman T.R., Tang,Z. and Dunphy,W.G. (1993) Negative regulation of the wee1 protein kinase by direct action of the nim1/cdr1 mitotic inducer. Cell, 72, 919–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Bordes J. and Nurse,P. (1995) p25Rum1 orders S phase and mitosis by acting as an inhibitor of the p34cdc2 mitotic kinase. Cell, 83, 1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton S. (1992) Cell cycle regulation of the human cdc2 gene. EMBO J., 11, 1797–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dendorfer U., Oettgen,P. and Libermann,T.A. (1994) Multiple regulatory elements in the interleukin-6 gene mediate induction by prostaglandins, cyclic AMP and lipopolysaccharide. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 4443–4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draetta G. and Beach,D. (1988) Activation of cdc2 protein kinase during mitosis in human cells: cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation and subunit rearrangement. Cell, 54, 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch T. and Nurse,P. (1990) Mutation of fission yeast cell cycle control genes abolishes dependence of mitosis on DNA replication. Cell, 60, 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa Y., Piwnica-Worms,H., Ernst,T.J., Kanakura,Y. and Griffin,J.D. (1990) cdc2 gene expression at the G1 to S transition in human T lymphocytes. Science, 250, 805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity P.A. and Wold,B.J. (1992) Effects of different DNA polymerases in ligation-mediated PCR: enhanced genomic sequencing and in vivo footprinting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 1021–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson U.E., Heid,C.A. and Williams,P.M. (1996) A novel method for real time quantitative RT–PCR. Genome Res., 6, 995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould K.L. and Nurse,P. (1989) Tyrosine phosphorylation of the fission yeast cdc2+ protein kinase regulates entry into mitosis. Nature, 342, 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M.E. and Ziff,E.B. (1984) Stimulation of 3T3 cells induces transcription of the c-fos proto-oncogene. Nature, 311, 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D.S. and Garrard,W.T. (1988) Nuclease hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 57, 159–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halazonetis T.D., Georgopoulos,K., Greenberg,M.E. and Lender,P. (1988) The c-fos dimerizes with itself and with c-Fos, forming complexes of different DNA binding affinities. Cell, 55, 917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heid C.A., Stevens,J., Livak,K.J. and Wiliams,P.M. (1996) Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res., 6, 986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henglein B., Chenivesse,X., Wang,J., Eick,D. and Brechot,C. (1994) Structure and cell cycle-regulated transcription of the human cyclin A gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5490–5494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann I., Clarke,P.R., Marcote,M.J., Karsenti,E. and Draetta,G. (1993) Phosphorylation and activation of human cdc25-C by cdc2-cyclin B and its involvement in the self-amplification of MPF at mitosis. EMBO J., 12, 53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R., Tanaka,H., Ohba,Y. and Yasuda,H. (1995) Mouse p87wee1 kinase is regulated by M-phase specific phosphorylation. Chromosome Res., 3, 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov V.N. and Nikolic-Zugic,J. (1997) Transcription factor activation during signal-induced apoptosis of immature CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. A protective role of c-Fos. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 8558–8566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., Nakata,Y., Suzuki,G., Chihara,K., Tokuhisa,T. and Shiozawa,S. (1999) Increased c-Fos/activator protein-1 confers resistance against anergy induction on antigen-specific T cell. Int. Immunol., 11, 1873–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.J., Angel,P., Lafyatis,R., Hattori,K., Kim,K.Y., Sporn,M.B., Karin,M. and Roberts,A.B. (1990) Autoinduction of transforming growth factor β1 is mediated by the AP-1 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol., 10, 1492–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.H., Proust,J.J., Buchholz,M.J., Chrest,F.J. and Nordin,A.A. (1992) Expression of the murine homologue of the cell cycle control protein p34cdc2 in T lymphocytes. J. Immunol., 149, 17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg R.D. and Lorch,Y. (1991) Irresistible force meets immovable object: transcription and the nucleosome. Cell, 67, 833–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T.A. (1985) Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotype selection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 488–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas J.J., Terada,N., Szepesi,A. and Gelfand,E.W. (1992) Regulation of synthesis of p34cdc2 and its homologues and their relationship to p110Rb phosphorylation during cell cycle progression of normal human T cells. J. Immunol., 148, 1804–1811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama K. and Sugano,S. (1994) Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides. Gene, 138, 171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa T., Kawasaki,H., Tanaka,M. and Ohba,Y. (1997) Analysis of chromatin structure of rat α1-acid glycoprotein gene; changes in DNase I hypersensitive sites after thyroid hormone, glucocorticoid hormone and turpentine oil treatment. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2635–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael W.M. and Newport,J. (1998) Coupling of mitosis to the completion of S phase through cdc34-mediated degradation of wee1. Science, 282, 1886–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.D., Curran,T. and Verma,I.M. (1984) c-fos protein can induce cellular transformation: a novel mechanism of activation of a cellular oncogene. Cell, 36, 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda N., Roses,A.D. and Vitek,M.P. (1997) Transcriptional regulation of the mouse presenilin-1 gene. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 23489–23497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D.O. (1995) Principles of CDK regulation. Nature, 374, 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muegge K., Williams,T.M., Kant,J., Karin,M., Chiu,R., Schmidt,A., Siebenlist,U., Young,H.A. and Durum,S.K. (1989) Interleukin-1 costimulatory activity on the interleukin-2 promoter via AP-1. Science, 246, 249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabeppu Y., Ryder,Y. and Nathans,D. (1988) DNA binding activities of three murine Jun proteins: stimulation by Fos. Cell, 55, 907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikura K. and Murray,J.M. (1987) Antisense RNA of proto-oncogene c-fos blocks renewed growth of quiescent 3T3 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 7, 639–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbury C., Blow,J. and Nurse,P. (1991) Regulatory phosphorylation of the p34cdc2 protein kinase in vertebrates. EMBO J., 10, 3321–3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse P. (1990) Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature, 344, 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell M.J., Raleigh,J.M., Verkade,H.M. and Nurse,P. (1997) Chk1 is a wee1 kinase in the G2 DNA damage checkpoint inhibiting cdc2 by Y15 phosphorylation. EMBO J., 16, 545–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker L.L., Atherton-Fessler,S. and Piwnica-Worms,H. (1992) p107wee1 is a dual-specificity kinase that phosphorylates p34cdc2 on tyrosine 15. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 2917–2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker L.L., Walter,S.A., Young,P.G. and Piwnica-Worms,H. (1993) Phosphorylation and inactivation of the mitotic inhibitor wee1 by the nim1/cdr1 kinase. Nature, 363, 736–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer G.P., Tanguay,R.L., Steigerwald,S.D. and Riggs,A.D. (1990) In vivo footprint and methylation analysis by PCR-aided genomic sequencing: comparison of active and inactive X chromosomal DNA at the CpG island and promoter of human PGK-1. Genes Dev., 4, 1277–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp A., Schneider,A., Vasrik,I., Finke,K., Xiong,Y., Beach,D., Alitalo,K. and Eilers,M. (1994) Repression of cyclin D1: a novel function of MYC. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 4032–4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines J. and Hunter,T. (1989) Isolation of a human cyclin cDNA: evidence for cyclin mRNA and protein regulation in the cell cycle and for interaction with p34cdc2. Cell, 58, 833–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh B.F. and Tjian,R. (1991) Transcription from a TATA-less promoter requires a multisubunit TFIID complex. Genes Dev., 5, 1935–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades K.L., Golub,S.H. and Economou,J.S. (1992) The regulation of the human tumor necrosis factor α promoter region in macrophage, T cell and B cell lines. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 22102–22107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riabowol K.T., Vosatka,R.J., Ziff,E.B., Lamb,N.J. and Feramisco,J.R. (1988) Microinjection of fos-specific antibodies blocks DNA synthesis in fibroblast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 1670–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell P. and Nurse,P. (1987) Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein kinase homolog. Cell, 49, 559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secchiero P. et al. (1998) Human herpesvirus 7 infection induces profound cell cycle perturbations coupled to disregulation of cdc2 and cyclin B and polyploidization of CD4+ T cells. Blood, 92, 1685–1696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serkkola E. and Hurme,M. (1993) Synergism between protein-kinase C and cAMP-dependent pathways in the expression of the interleukin-1β gene is mediated via the activator-protein-1 (AP-1) enhancer activity. Eur. J. Biochem., 213, 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa S., Tanaka,Y., Fujita,T. and Tokuhisa,T. (1992) Destructive arthritis without lymphocyte infiltration in H2-c-fos transgenic mice. J. Immunol., 148, 3100–3104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa S., Shimizu,K., Tanaka,K. and Hino,K. (1997) Studies on the contribution of c-fos/AP-1 to arthritic joint destruction. J. Clin. Invest., 99, 1210–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipp M.A. and Reinherz,E.L. (1987) Differential expression of nuclear proto-oncogenes in T cells triggered with mitogenic and nonmitogenic T3 and T11 activation signals. J. Immunol., 139, 2143–2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M.J. (1993) Activation of the various cyclin/cdc2 protein kinases. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 5, 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld U., Labbe,J.C., Fesquet,D., Cavadore,J.C., Picard,A., Sadhu,K., Russell,P. and Doree,M. (1991) Dephosphorylation and activation of a p34cdc2/cyclinB complex in vitro by human CDC25 protein. Nature, 351, 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman K.S., Northrop,J.P., Verweij,C.L. and Crabtree,G.R. (1990) Transmission of signals from the T lymphocyte antigen receptor to the genes responsible for cell proliferation and immune function: the missing link. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 8, 421–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindelov L.L., Christensen,I.J. and Nissen,N.I. (1983) A detergent-trypsin method for the preparation of nuclei for flow cytometric DNA analysis. Cytometry, 3, 323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.Q., Grigoriadis,A.E., Mohle-Steinlein,U. and Wagner,E.F. (1991) A novel target cell for c-fos-induced oncogenesis: development of chondrogenic tumours in embryonic stem cell chimeras. EMBO J., 10, 2437–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N., Broome,M. and Hunter,T. (1995) Regulation of the human WEE1Hu CDK tyrosine 15-kinase during the cell cycle. EMBO J., 14, 1878–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnholds J., Philipsen,J.N. and Ab,G. (1988) Tissue-specific and steroid-dependent interaction of transcription factors with the oestrogen-inducible apoVLDL II promoter in vivo. EMBO J., 7, 2757–2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. and Russell,P. (1993) Nim1 kinase promotes mitosis by inactivating Wee1 tyrosine kinase. Nature, 363, 738–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Wang,Z. and Ravid,K. (1996) The cell cycle in polyploid megakaryocytes is associated with reduced activity of cyclin B1-dependent cdc2 kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 4266–4271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]