Abstract

Terfezia boudieri Chatin and Tirmania nivea (Desf.) Trappe, the desert truffles, are mycorrhizal fungi that are mostly endemic to arid and semi-arid areas of the Mediterranean where they are associated with Helianthemum species. The current study aimed to test the use of the two-culture media, Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and Malt Extract Agar (MEA), on isolation, apical growth rate (APG) and the production of wet weight of mycelial biomass (WWMBP) of two Moroccan species of Terfezia boudieri and Tirmania nivea collected respectively from Walidia and Boujdour. For the both species PDA and MEA were the most effective culture media for isolation, apical growth rate (APG) and wet weight of mycelial biomass production (WWMBP). This study demonstrated that PDA growth medium outperformed the MEA for both fungal species with an apical growth rate (APG) of (0.05 ± 0.01) cm/h for T. boudieri and T. nivea in PDA, against (0.04 ± 0.00) cm/h for T. boudieri and T. nivea in MEA. Additionally, the wet weight of mycelial biomass production (WWMBP) was measured using the same culture media (PDA) and (MEA). The wet weight of mycelial biomass produced by T. boudieri and T. nivea were nearly identical in PDA medium. The same result was exhibited for T. nivea in MEA. In addition, the T. boudieri and T. nivea species sown in solid media showed a considerable apical growth rate and wet weight of mycelial biomass production (WWMBP). The success of the cultivation process of T. boudieri and T. nivea will enable the potential use of them as ectomycorrhizal inoculum in reforestation programs with their host plant and ultimately the production of edible mushrooms in the field.

Keywords: Desert truffles, Terfezia boudieri, Tirmania nivea, Mycelial biomass, Spore suspension

Introduction

Desert truffles are macrofungi belonging to Pezizaceae family that produce ascocarps growing hypogeously [1]. Ascomycete, desert truffles, can be found in the Mediterranean area under the genera Delastria, Mattirolomyces, Picoa, Terfezia and Tirmania [2]. Desert truffles are an excellent source of a variety of essential nutrients including minerals, amino acids, fatty acids, proteins, carbs, fibers, vitamins, terpenoids, and sterols [3, 4]. In addition, they contain a high amount of antimicrobial, anticancer and antioxidant compounds, all shown to have a beneficial impact on human health [5]. In recent years, the anticancer and immunomodulatory properties exhibited by T. boudieri Chatin have been demonstrated [5], along with those of T. claveryi Chatin [6]. The two white truffles, T. boudieri and T. nivea, are edible, mycorrhizal, hypogeous fungi [7]. T. boudieri, in particular, holds social and economic importance in Morocco, where it grows naturally in various arid and semi-arid regions. Its high market value and integration into local cultural practices make it a key resource for rural economies and traditional knowledge preservation [8]. Desert truffles are one of the most expensive culinary fungi, growing in association with various forest trees and shrubs [9, 10]. Numerous desert truffle species are highly prized for their culinary qualities and may play a significant role in the cultural identity of local communities. Some European truffles are among the most expensive foodstuffs in the world, while less aromatic desert truffle species may be used to produce local foods and medication [11]. In the desert regions of Morocco, a number of ecological degradation phenomena have been reported, with profound implications for the plant community. Wind and water erosion represent significant environmental concerns. Wind erosion can result in the removal of topsoil, while water erosion can lead to the formation of gullies and the loss of fertile land [12]. Moreover, the term desertification process by which formerly fertile land becomes deserts is often the result of drought, deforestation, and/or unsustainable agricultural practices, leading to a decline in vegetation cover and soil fertility. Furthermore, the accumulation of salts in the soil, often attributable to improper irrigation practices, can result in soil infertility and unsuitability for agricultural purposes [13]. Livestock grazing beyond the land’s carrying capacity can lead to the degradation of vegetation cover, soil compaction, and erosion. Additionally, deforestation and the removal of trees for fuel, construction, or agriculture can lead to a loss of biodiversity, soil erosion, and reduced water retention in the soil. Finally, climate change, marked by rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns, has been identified as a key driver of desertification and other forms of land degradation, further exacerbating the vulnerability of desert zones. The combined effect of these phenomena leads to the degradation of the environment in Moroccan desert zones, impacting both the ecosystem and the livelihoods of local communities [14]. Thus, the introduction of desert truffle mycorrhizal plants in the arid zones of Morocco could have a considerable potential to promote the spinneret of desert truffle and improve soil fertility. Indeed, desert truffles form symbiotic relationships with local host plants, enhancing their nutrient uptake. The incorporation of these plants can enhance biodiversity and encourage the proliferation of native plant species. Moreover, mycorrhizal associations facilitate the efficient utilization of water by plants, which is a crucial aspect in arid environment. Desert truffles can assist plants in adapting to harsh climatic conditions, thereby enhancing their resilience to drought and extreme temperatures. In the other hand, desert truffles are highly regarded for their culinary applications, representing a potential source of revenue for local communities [15]. These factors underscore the potential benefits of integrating desert truffle mycorrhizal plants into arid zone for agriculture and ecosystem management ends in Morocco, predominantly, creating new crops suitable for arid regions [16]. Thus, there is an increasing interest in implementing desert truffle production in dry regions as a method of utilizing lands formerly deemed unproductive [17]. Terfezia and Tirmania, also known as desert truffles are mycorrhizal fungi that are predominantly endemic to arid and semiarid area of the Mediterranean region where they are associated with Helianthemum species [2]. Other works have reported that Terfezia species are capable of developing many forms of mycorrhizal connections, including endo and, ectomycorrhiza [18–20]. According to [21] T. boudieri is among the desert truffle species part of the Pezizaceae family forming mycorrhizal relationships with its hosts. A study on T. nivea fungal biomass revealed its potential as a natural and renewable resource with medicinal and industrial applications, including antifungal, antibacterial, antiviral, anticancer, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [22]. According to [23], a variety of industrial applications have been identified for desert truffles, including T. nivea. The potential uses encompass various domains, such as food, medicine, and nanotechnology. Desert truffles, such as T. nivea are widely recognized as significant contributors of antioxidant compounds, including phenolics β-carotene and ascorbic acid [24]. The fruiting body of T. nivea possesses a significant number of antimicrobial compounds [25]. Growing desert truffles in auspicious region of Morocco could give several economic, ecological, nutritional, and cultural benefits, as well as additional income for local farmers. Desert truffles are high in nutrients, including proteins, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. Hence, desert truffles are highly valued on the market, both nationally and globally, which might help to improve the standard of living in rural areas. Desert truffles also form symbiotic connections with the roots of host plants, including those in the Cistaceae family and Helianthemum genus [26], which can assist to retain biodiversity and minimize soil erosion. They consequently assist fight desertification. In addition, several Moroccan localities have a cultural practice of picking desert truffles, which is typically associated with hereditary talents and local traditions. In short, cultivating desert truffles can benefit the local economy, the environment, health, and the preservation of cultural legacy. In contrast, due to a lack of efficient cultivation methods, biomass generation under controlled conditions appears to be an environmentally friendly tool for producing fungal inoculum for use in plantation programs and soil restoration in degraded areas. The overall objectives of this study were to isolate two desert truffles, T. boudieri and T. nivea originated from Morocco, using spore suspension, estimate their apical growth rate using submerged and solid-state culture, and produce wet mycelial biomass by culturing them in solid-state culture. The resulting mycelial biomass could be used as source of inoculum to grow ectomycorrhizal host plants seedlings like Helianthemum.

Materials and methods

Collection of the fungal species

In February 2023, mature desert truffle ascocarps of T. boudieri were harvested on limestone soil from Had Hrara (32° 26′ 27″ N, 9° 08′ 00″ W) in the Walidia region in western Morocco, close to their natural host plant, Helianthemum salicifolium, and ascocarps of T. nivea were collected in the region of Boujdour city (26.133° N, 14.500° W) in southern Morocco when it’s naturally associated with Helianthemum sp. The ascocarps were stored in paper bags in the fridge (−4 °C) until use. Figure 1(a) shows the association of T. boudieri with Helianthemum salicifolium.

Fig. 1.

a1a2. ascocarps and longitudinal section of T. boudieri. a3a4. culture of T. boudieri on PDA and MEA solid media. a5. wet mycelial biomass produced by T. boudieri on PDA or MEA solid media. a6a7. ascocarps and longitudinal section of T. nivea. a8a9. culture of T. nivea on PDA and MEA solid media. a10. wet mycelial biomass produced by T. nivea on PDA or MEA solid media

Spore suspension on growing media

Mycelial cultures were isolated from spore suspensions on both solid and liquid media. To prepare the spore suspensions, ascocarps from the two species, T. boudieri and T. nivea were firstly rinsed in sterile distilled water, then wiped with a filter paper, and soaked in 70% ethanol for five minutes [27, 28]. Under a laminar flow hood, gleba fragments were then suspended in 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 ml sterile distilled water, along with a magnet bar. The contents were then shaken for one hour in an attempt to release as many spores as possible. The resultant mixture was then filtered using sterile gauze. The filtrate obtained thusly served as a spore suspension. A 1-ml sample of this suspension was then used as an inoculum of two culture media, namely liquid for MEA and solid for MEA and PDA.

Culture media and isolation process

Potato dextrose agar (PDA) HIMEDIA and malt extract agar (MEA) Difco were chosen to isolate fungus species from ascocarps as they generally provide ideal environment for fungal growth. The volume was adjusted to 500 mL, and the pH was adjusted to 5.62 for PDA and 4.55 for MEA. All of these culture media were autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min. The mixture of the culture media was divided using 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks at a ratio of 50 mL per flask. On the surface of the culture media, 1 mL of the spore suspension of each fungal species, T. boudieri and T. nivea, was aseptically deposited and the Erlenmeyer flasks were incubated in the dark for 7 days at 25 °C. Mycelia development and purity were examined microscopically. For each experiment, twelve replicates were carried out.

Strain reactivation

Reactivation methods can enhance culture techniques and result in more efficient production of fungal mycelium. A sample of PDA and MEA medium with mycelium was collected and deposited centrally in Petri dishes pre-pulled with MEA and PDA and incubated at 25 °C for 4 to 5 days [29]. Figures 1(d) and 1(e) show cultures of T. boudieri and T. nivea on MEA and PDA respectively. The fungal species exhibit rapid growth, producing, thick, white, cottony mycelium that proliferates swiftly over the agar surface.

Apical growth rate on PDA and MEA

Apical growth rate (APG) corresponds to the elongation of the mycelium grown on a solid surface. This elongation is measured regularly with a graduated ruler. The APG is expressed as centimeters per hour of culture time. Petri dishes containing agar medium were inoculated with a frozen inoculum square, which was placed immediately at the center of the Petri dish and incubated at 25 °C for 7 days. Mycelia proliferation was examined using potato dextrose agar (PDA) and malt extract agar (MEA).

Measurement of wet weight mycelia biomass production in solid-state culture

The wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) was directly estimated using 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks at a ratio of 100 mL per flask that was subsequently filled with 100 mL of the suitable culture medium, either PDA or MEA and autoclaved at 121 °C for a duration of 15 min. A frozen inoculum square of T. boudieri and T. nivea, which contains mycelium was placed at the center of the Erlenmeyer flasks. The Erlenmeyer flasks were subjected to incubation at a temperature of 25 °C for 7 days within the stove. Three replicates were set up for each test. After the incubation, the contents of Erlenmeyer flasks were delicately scraped using a pair of tweezers to evenly distribute the generated biomass, which was subsequently measured using a precise weighing scale.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using the statistical software StatSoft \ STATISTICA 12. and were shown to be statistically significant with a P-value lower than 0.05. The data were represented as the mean and the standard deviation. The present study aims to conduct a statistical analysis of the apical growth rate and mycelial biomass fresh production on agar media through the utilization of ANOVA tests to make comparisons and performed by Tukey HSD Test.

Results

Isolation of mycelial cultures from spore suspensions

For both fungal species, the use of spore filtrate as an inoculum for solid media PDA or MEA as a carbon or nitrogen source with an acidic pH resulted in a successful initiation of truffle growth from spore filtrate in terms of isolation. This situation could be explained by the release of mature spores into the culture medium, which enables direct contact between the spores and nutrients. This facilitates germination and, consequently the growth of these two fungal species.

Figures 2 showed the macroscopic features on the different growth media of T. boudieri and T. nivea on submerged and solid media using spore suspension. This study showed that T. nivea and T. boudieri were able to grow on MEA and PDA solid state culture. And T. nivea displayed a potential to grow on MEA submerged culture (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 2.

(a1a2-c1c2): macroscopic features on the different growth media of T. boudieri and T. nivea on submerged and solid-state culture using spore suspension. Fig.a1a2. macroscopic features of T. boudieri and T. nivea on MEA solid media using spore suspension. Fig.b1b2. macroscopic features of T. boudieri and T. nivea on PDA solid media using spore suspension. Fig.c1c2. macroscopic features of T. boudieri and T. nivea on MEA submerged media using spore suspension. Fig.d1. mixture of spore suspension of T. boudieri. Fig.d2. spore filtrate of T. boudieri

Fig. 3.

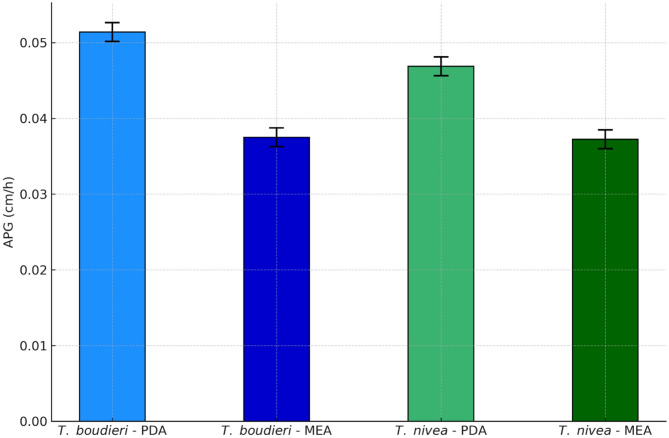

Comparison of apical growth rate (APG) of T. boudieri and T. nivea on PDA and MEA solid media

Fig. 4.

Wet weight of mycelia biomass produced (WWMBP) by T. boudieri and T. nivea on PDA and MEA solid media Statistical results of wet weight mycelial biomass production (WWBMP), (g/100 mL); P = 0.888

Morphological features of fungal species

After 3 to 5 days, a black color has developed on the aerial part of the mycelium, which testified to conidiogenesis, or spores’ production. The thallus showed a smooth appearance, and a white color distributed homogeneously on the PDA and MEA culture media. Mycelia macroscopic characteristics of T. nivea have shown a white aspect, the ascocarps can occasionally measure more than 10 cm. The ascocarps white hue gradually turns to a dark yellow hue due to air exposure. Figures 1(a1 a2) and 1(a6 a7) show the ascocarps and longitudinal sections of T. boudieri and T. nivea respectively. The ascocarp of T. boudieri was subglobose, turbinate or fusiform, with a diameter of 3 to 8 cm and a weight of 30 to 100 g. This description is in accordance with those offered for T. boudieri [30].

Apical growth rate of fungal species

Descriptive analysis of apical growth rate (cm/h) was conducted for two fungal species T. boudieri and T. nivea cultured on two different media PDA and MEA, with 12 replicates per condition. The results showed that the two species exhibited slightly higher apical growth rates on PDA medium 0.05 cm/h compared to MEA medium 0.04 cm/h, regardless of the species. The standard deviation was either zero or very low across all conditions, indicating low intra-group variability and high consistency in the measurements (Table 1).

Table 1.

Apical growth rate (APG) of T. boudieri and T. nivea on PDA and MEA (P = 0.094631)

| Fungal Species | Culture Medium | Replicates (N) | APG (cm/h) (Mean) | APG (cm/h) (Std.Err.) | APG (cm/h) (-Std.Err) |

APG (cm/h) (+ Std.Err) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. boudieri | PDA | 12 | 0.051389 | 0.001240 | 0.050149 | 0.052629 |

| T. boudieri | MEA | 12 | 0.037500 | 0.001240 | 0.036260 | 0.038740 |

| T. nivea | PDA | 12 | 0.046875 | 0.001240 | 0.045635 | 0.048115 |

| T. nivea | MEA | 12 | 0.037222 | 0.001240 | 0.035982 | 0.038462 |

From a statistical standpoint, the analysis of variance did not reveal a significant difference between the experimental conditions p = 0.0946. However, this p-value, being close to the conventional significance threshold (α = 0.05), suggests a possible trend in growth rate variation depending on the culture medium.

The two-way analysis of variance revealed a highly significant effect of the culture medium on mycelial growth F (1,44) = 90.128; p < 0.0001. In contrast, the effect of the species was not significant F (1,44) = 3.734; p = 0.0598, although a trend toward significance was observed. The interaction between the culture medium and the tested species was not statistically significant F (1,44) = 2.918; p = 0.0946, indicating that the effect of the medium is generally independent of the used species (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate tests of significance for apical growth rate (APG) (cm/h)

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.089773 | 1 | 0.089773 | 4866.383 | 0.000000 |

| Culture Medium | 0.001663 | 1 | 0.001663 | 90.128 | 0.000000 |

| Species | 0.000069 | 1 | 0.000069 | 3.734 | 0.059774 |

| Culture Medium × Species | 0.000054 | 1 | 0.000054 | 2.918 | 0.094631 |

| Error | 0.000812 | 44 | 0.000018 |

Effect of culture medium

The fact that the culture medium has a highly significant effect (p < 0.0001) indicates that it strongly influences APG. This likely means that one of the media provides more favorable physico-chemical conditions (better nutrient availability, optimal pH, aeration, etc.).

Effect of fungal species

The effect of the species is not statistically significant but approaches the threshold (p = 0.059). This suggests that there may be slight genetic variability among the species affecting their growth but the available data do not allow for a firm conclusion. This may reflect a weak genotypic effect or low intraspecific variability under the tested conditions.

Interaction between medium and species

The interaction was not significant; this indicates that the species respond similarly to the tested media. In other words, no species show a particularly better or worse behavior on a specific medium, which reinforces the idea of a dominant overall effect of the culture medium.

The Tukey HSD post hoc test on APG (cm/h) showed no significant difference between T. boudieri and T. nivea when cultivated on the same medium, whether PDA or MEA. However, there was a highly significant increase in APG when either species was grown on PDA compared to MEA (p < 0.001). These results indicate that growth rate is primarily influenced by the solid medium rather than the fungal species (Table 3).

Table 3.

Tukey HSD test Results, apical growth rate (APG) (cm/h)

| Condition | APG (cm/h) |

p - MEA – T. boudieri |

p - MEA – T. nivea |

p - PDA – T. boudieri |

p - PDA – T. nivea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEA - T. boudieri | 0.0375 | - | 0.998626 | 0.000169 | 0.000182 |

| MEA - T. nivea | 0.03722 | 0.998626 | - | 0.000169 | 0.000176 |

| PDA - T. boudieri | 0.05139 | 0.000169 | 0.000169 | - | 0.062539 |

| PDA - T. nivea | 0.04688 | 0.000182 | 0.000176 | 0.062539 | - |

For the two fungal species T. boudieri and T. nivea, the PDA and MEA culture media showed no significant difference on apical growth rate (P = 0.094631). Statistical processing of the results has shown that the apical growth rate of T. boudieri and T. nivea species in PDA culture medium were similar. Thus, the apical growth rate has shown no significant difference for the fungal species T. boudieri and T. nivea in MEA culture medium. The results of the current study have shown that the used culture media PDA and MEA were satisfactorily for the two fungus species T. boudieri and T. nivea, with growth rates of 0.05 ± 0.01 cm/h and 0.04 ± 0.00 cm/h respectively (Table 2; Figs. 5 and 6). The growth of the fungal mycelia took 4 days for PDA solid medium and 5 days for MEA solid medium to invade the total surface of the 9 cm diameter glass petri dish.

Fig. 5.

Effect of PDA and MEA solid media on apical growth rate (APG) of T. boudieri and T. nivea

Fig. 6.

Effect of PDA and MEA solid media on wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) by T. boudieri and T. nivea

Production of mycelial biomass of terfezia boudieri and tirmania nivea in solid-state culture

Descriptive statistics of wet weight of mycelia biomass production have shown variation depending on the culture medium, regardless of the targeted species. For the T. boudieri, wet weight of mycelia biomass production on MEA medium (M = 22.75 ± 4.23 g/100 mL) was noticeably higher than on PDA medium (M = 16.73 ± 2.24 g/100 mL). A similar trend was observed for the T. nivea species, with a mean production of (24.43 ± 4.15 g/100 mL) on MEA compared to (17.79 ± 3.73 g/100 mL) on PDA. Thus, although the analysis of variance did not reveal a significant interaction between culture medium and species (p = 0.888), the descriptive data suggest that MEA medium generally promotes higher wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) than PDA medium, regardless of the species used (Table 3; Figs. 5 and 6). The two-way analysis of variance revealed a significant effect of the culture medium on the measured variable F (1,8) = 8.88; p = 0.0176. This result indicates that the type of medium notably influences the species’ response, regardless of their identity. In contrast, the effect of the fungal species was not statistically significant F (1,8) = 0.42; p = 0.5373), suggesting a relatively homogeneous response among the different species under the experimental conditions. Furthermore, the interaction between fungal species and culture medium was not significant F (1.8) = 0.021; p = 0.8883, indicating that the species responded similarly to the tested media, with no marked differential response. These results highlight the importance of the environmental factor culture medium over intraspecific variability in this context (Table 4), (Table 5).

Table 4.

Wet weight mycelial biomass produced (WWBMP) by T. boudieri and T. nivea on PDA and MEA

| Fungal Species | Culture Medium | Replicates (N) | (WWBMP) (g/100 mL) | (WWBMP) (g/100mL) (Std.Err.) | (WWBMP) (g/100mL) (-Std.Err) | (WWBMP) (g/100mL) (+ Std.Err) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. boudieri | PDA | 12 | 16.73248 | 2.122413 | 14.61007 | 18.85489 |

| T. boudieri | MEA | 12 | 22.75018 | 2.122413 | 20.62776 | 24.87259 |

| T. nivea | PDA | 12 | 17.79267 | 2.122413 | 15.67026 | 19.91508 |

| T. nivea | MEA | 12 | 24.42600 | 2.122413 | 22.30359 | 26.54841 |

Table 5.

Univariate tests of significance for wet weight mycelial biomass produced (WWBMP) (g/100mL) by T. boudieri and T. nivea

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 5.006330 | 1 | 5.006330 | 370.458 | 0.000000 |

| Fungal Species | 5.614 | 1 | 5.614 | 0.415 | 0.537257 |

| Culture Medium | 120.036 | 1 | 120.036 | 8.882 | 0.017591 |

| Fungal Species × Culture Medium | 0.284 | 1 | 0.284 | 0.021 | 0.888273 |

| Error | 108.111 | 8 | 13.514 |

The Tukey HSD post hoc test for wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) (g/100 mL) indicated no statistically significant differences among the tested conditions. Specifically, neither the fungal species T. boudieri and T. nivea nor the culture medium PDA and MEA had a significant impact on wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) (all p-values > 0.05). These findings suggest that, under the current experimental conditions, wet weight of mycelia biomass production is not significantly influenced by the fungal species or the solid media (Table 6).

Table 6.

Tukey HSD test Results, wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) (g/100 mL)

| Condition | (WWMBP) (g/100 mL) |

p - T. boudieri - PDA |

p - T. boudieri - MEA |

p - T. nivea - PDA |

p - T. nivea - MEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. boudieri - PDA | 16.732 | - | 0.262488 | 0.983860 | 0.123205 |

| T. boudieri - MEA | 22.75 | 0.262488 | - | 0.405376 | 0.941697 |

| T. nivea - PDA | 17.793 | 0.983860 | 0.405376 | - | 0.200170 |

| T. nivea - MEA | 24.426 | 0.123205 | 0.941697 | 0.200170 | - |

The results of the statistical analysis indicated that there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) in wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) when different culture media were used in this direct estimation p = 0.888 (Table 3; Figs. 5 and 6). The wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) of T. boudieri recorded 16.73 ± 2.12 g/100mL and 22.75 ± 2.12 g/100mL in PDA and MEA solid media respectively, whereas, the T. nivea species recorded a wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) of 17.79 ± 2.12 g/100 mL and 24.42 ± 2.12 g/100 mL in PDA and MEA respectively.

Discussion

The desert truffle species T. boudieri and T. nivea have responded positively to different cultural environments. Results show that (PDA) culture medium works better than the culture medium (MEA) for both types of fungi T. boudieri and T. nivea, with APG of 0.05 ± 0.01 cm/h and 0.04 ± 0.00 cm/h for the same solid media respectively. It is clear that these two species use the source of carbohydrates, which is dextrose in the PDA and maltose in the MEA, which serve as growth stimulants for fungal species. They provide an easily available source of energy that supports their metabolic activities, promotes their proliferation, and fosters the wet mycelia biomass production (WWMBP). This is in line with other research that looked at how Tuber maculatum grew on five different solid media. Tuber maculatum had the biggest colonies on malt extract agar (MEA) medium with APG of 0.06 ± 0.06 cm/h, potato glucose agar (PGA) medium with APG of 0.06 ± 0.03 cm/h, potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium with APG of 0.05 ± 0.02 cm/h, M-17 Agar medium with APG of 0.03 cm/h, yeast extract agar (YEA) medium with APG of 0.03 ± 0.01 cm/h and, beef extract agar (BEA) medium with APG of 0.02 ± 0.01 cm/h [31]. Furthermore, it was observed that MEA and PDA were identified as the optimal media for the mycelial growth of T. koreanum when grown under conditions of 6.0 pH and 25 °C for a period of 30 days [32]. Our finding, showed that T. boudieri produces mycelial biomass using PDA and MEA as cultivation media, with wet weight of mycelia biomass production (WWMBP) of 16.73 ± 2.12 g/100 mL and 22.75 ± 2.12 g/100 mL, respectively. In PDA and MEA culture conditions, T. nivea species produces 17.79 ± 2.12 g/100 mL and 24.42 ± 2.12 g/100 mL of wet weight of mycelia biomass production, respectively. In a prior investigation, a total of 10 media were subjected to experimentation to assess their suitability for promoting the growth of Tuber melanosporum. Fungal growth was observed exclusively on two media, malt extract Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) agar and a slightly modified minimal medium. In addition, it was observed that both Malt extract agar and PDA facilitated the development of mycelia at a minimal rhythm. Conversely, malt extract Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) agar demonstrated the highest growth potential, exhibiting a growth rate of 8 mm per week [33]. A recent study has revealed that the growth of truffles was significantly enhanced when citric acid or glucose were utilized as the carbon source [34]. Furthermore, it was observed that Tuber melanosporum exhibited growth only when sucrose was provided as a carbon source [33], whereas Tuber borchii species displayed comparable growth rates in mannose, mannitol and, glucose as demonstrated by another study [35].

Conclusion

The comparative analysis of the apical growth rate (APG) and the wet weight of mycelial biomass production (WWMBP) reveals that the culture medium plays a critical role in influencing growth rate, while mycelial biomass production remains unaffected under the tested conditions. Specifically, the Tukey HSD post hoc test demonstrated a highly significant increase in APG for both T. boudieri and T. nivea when cultivated on PDA compared to MEA (p < 0.001), suggesting that medium composition directly impacts radial mycelial expansion. In contrast, no statistically significant differences in WWMBP were observed across species or media (all p > 0.05), indicating that biomass accumulation is not significantly influenced by either fungal species or the solid growth substrate. These findings highlight the differential sensitivity of growth parameters to environmental conditions and underscore the importance of selecting appropriate culture media depending on the targeted physiological trait.

In solid-state culture, apical growth rate and mycelial biomass wet production were measured for two Moroccan-originated desert truffle species, Terfezia boudieri collected from Walidia and Tirmania nivea collected from Boujdour. The results presented in this paper showed that the apical growth rate measurement can be regarded as a reliable direct method for determining the ability of the tested species to develop on solid media. The Potato Dextrose Agar outperformed the culture medium Malt Extract Agar for both fungal species. The two species used dextrose and maltose as growth stimulants for fungal organisms. They offer a readily accessible energy supply that sustains their metabolic functions and encourages their growth. These results are proven by the exceptional apical growth rates and the relatively high mycelial biomass production. The success of the mycelial biomass production of Terfezia boudieri and Tirmania nivea would be a key factor to produce an inoculum of desert truffle to use with host plants in reforestation program and production of edible mushrooms in arid and semi-arid regions of Morocco. Furthermore, mycelium production represents a valuable source of bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical, agricultural, and industrial applications, such as secondary metabolites like polysaccharides, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, and enzymes. This approach offers a sustainable and scalable alternative to wild harvesting, enabling consistent quality and year-round production. Finally, this is the first time that in vitro mycelium and spore production has been described for T. boudieri and T. nivea in Morocco. Experiments on the inoculation of young plants, particularly from the Cistaceae family and the Helianthemum genus, are currently being carried out, and the results will be published subsequently.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the Biology Department in the Polydisciplinary Faculty Safi, Cadi Ayyad University for kindly providing the facilities to carry out the different tests of fungal strains isolation and culture.

Abbreviations

- PDA

Potato Dextrose Agar

- MEA

Malt Extract Agar

- APG

Apical growth rate

- YEA

Yeast extract agar

- PGA

Potato glucose agar

- BEA

Beef extract agar

- PVP

Polyvinylpyrrolidone

- APG

Apical growth rate

- WWMBP

Wet weight of mycelia biomass production

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: [O L]; Methodology: [K H, T A, O L]; Formal analysis and investigation: [K H, T A, O L]; Writing - original draft preparation: [K H]; Writing - review and editing: [O L, T A]; Supervision: [O L].

Funding

This work has not received any external funding, and was held with the support of the Biology Department, Polydisciplinary Faculty Safi, Cadi Ayyad University.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not involve human participants, human data, or animals, and thus, ethical approval and consent to participate were not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gajos M, Hilszczańska D. Research on truffles: scientific journals analysis. Sci Res Essays. 2013;8:1837–47. http://www.academicjournals.org/SRE. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Díez J, Manjón JL, Martin F. Molecular phylogeny of the mycorrhizal desert truffles (Terfezia and Tirmania), host specificity and edaphic tolerance. J Mycologia. 2002;94:247–59. 10.1080/15572536.2003.11833230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murcia MA, Martínez-Tomé M, Vera A, Morte A, Gutierrez A, Honrubia M, Jiménez AM. Effect of industrial processing on desert truffles Terfezia Claveryi chatin and Picoa juniperi vittadini: proximate composition and fatty acids. J Sci Food Agric. 2003;83:535–41. 10.1002/jsfa.1397. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandeel QA, Al-Laith AAA. Ethnomycological aspects of the desert truffle among native Bahraini and non-Bahraini peoples of the Kingdom of Bahrain. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110:118–29. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Obaydi MF, Hamed WM, Al Kury LT, Talib WH. Terfezia boudieri: a desert truffle with anticancer and Immunomodulatory activities. J Front Nutr. 2020;7:38. 10.3389/fnut.2020.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahham SS, Al-Rawi SS, Ibrahim AH, Majid ASA, Majid AMSA. Antioxidant, anticancer, apoptosis properties and chemical composition of black truffle Terfezia Claveryi. J Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018;25:1524–34. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamza A, Zouari N, Zouari S, Jdir H, Zaidi S, Gtari M, Neffati M. Nutraceutical potential, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Terfezia Boudieri Chatin, a wild edible desert truffle from Tunisia arid zone. J Arab J Chem. 2016;9:383–89. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.06.015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajana M, Outcoumit A, El Kholfy S, Touhami AO, Benkirane R, Douira A. (2015) Inventaire des champignons comestibles du Maroc inventory of edible mushrooms in Morocco. Journal International Journal of Innovation Applied Studies 10: 1103. http://tinyurl.com/2kcxtc9b.

- 9.Bradai L, Bissati S, Chenchouni H. Desert truffles of the North Algerian sahara: diversity and bioecology. J Emirates J Food Agriculture: 425 – 35. 2014. 10.9755/ejfa.v26i5.16520. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shamekh S, Grebenc T, Leisola M, Turunen O. The cultivation of Oak seedlings Inoculated with Tuber aestivum Vittad. In the boreal region of Finland. J Mycological Progress. 2014;13:373–80. 10.1007/s11557-013-0923-5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas PW, Elkhateeb WA, Daba G. Truffle and truffle-like fungi from continental Africa. J Acta Mycologica. 2019;54. 10.5586/am.1132.

- 12.Schilling J, Freier KP, Hertig E, Scheffran J. (2012) Climate change, vulnerability and adaptation in North Africa with focus on Morocco. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, Volume 156, 12–26, ISSN 0167–8809. 10.1016/j.agee.2012.04.021.

- 13.Hirich A, Choukr-Allah R, Ezzaiar R, Shabbir SA, Lyamani A. Introduction of alternative crops as a solution to groundwater and soil salinization in the Laayoune area, South Morocco. Euro-Mediterranean J Environ Integr. 2021;6:52. 10.1007/s41207-021-00262-7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Mouttaqi A, Mnaouer I, Nilahyane A, Ashilenje DS, Amombo E, Belcaid M, Ibourk M, Lazaar K, Soulaimani A, Devkota KP, Kouisni L, Hirich A. Influence of cutting time interval and season on productivity, nutrient partitioning, and forage quality of blue panic grass (Panicum Antidotale Retz.) under saline irrigation in Southern region of Morocco. Front Plant Sci. 2023. 10.3389/fpls.2023.1186036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Chen YL. Recent advances in cultivation of edible mycorrhizal mushrooms. J Mycorrhizal Fungi: 375 – 97. 2014. 10.1007/978-3-662-45370-4_23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morte A, Kagan-Zur V, Navarro-Ródenas A, Sitrit Y. Cultivation of desert truffles a crop suitable for arid and semi-arid zones. J Agron. 2021;11:1462. 10.3390/agronomy11081462. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navarro-Ródenas A, Pérez-Gilabert M, Torrente P, Morte A. The role of phosphorus in the ectendomycorrhiza continuum of desert truffle mycorrhizal plants. J Mycorrhiza. 2012;22:565–75. 10.1007/s00572-012-0434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaretsky M, Kagan-Zur V, Mills D, Roth-Bejerano N. Analysis of mycorrhizal associations formed by Cistus incanus transformed root clones with Terfezia Boudieri isolates. J Plant Cell Rep. 2006;25:62–70. 10.1007/s00299-005-0035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shavit E, Shavit E. The medicinal value of desert truffles in desert truffles: Phylogeny, Physiology, distribution and domestication. pp. 323 – 40: Springer; 2014. 10.1007/978-3-642-40096-4_20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murat C, Payen T, Noel B, Kuo A, Morin E, Chen J, … Da Silva C (2018) Pezizomycetes genomes reveal the molecular basis of ectomycorrhizal truffle lifestyle. Journal Nature ecology 2: 1956-65. 10.1038/s41559-018-0710-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Giovannetti G, Roth-Bejerano N, Zanini E, Kagan‐Zur V. Truffles and their cultivation. J Hortic Reviews. 1994;16:71–107. 10.1002/9780470650561. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khaled JM, Alharbi NS, Mothana RA, Kadaikunnan S, Alobaidi AS. Biochemical profile by GC–MS of fungal biomass produced from the ascospores of Tirmania Nivea as a natural renewable resource. J Fungi. 2021;7:1083. 10.3390/jof7121083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas P, Elkhateeb W, Daba G. Industrial applications of truffles and truffle-like fungi. Advances in macrofungi. CRC; 2021. pp. 82–8. https://tinyurl.com/5dbfkuvt.

- 24.Yousif PA, Jalal AF, Faraj KA. Essential constituents of truffle in Kurdistan region. J Pure Appl Sci. 2020;32:158–66. 10.21271/ZJPAS.32.5.15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veeraraghavan VP, Hussain S, Papayya Balakrishna J, Dhawale L, Kullappan M, Mallavarapu Ambrose J, Krishna Mohan S. (2022) A comprehensive and critical review on ethnopharmacological importance of desert truffles: Terfezia claveryi, Terfezia boudieri, and Tirmania nivea. Journal Food Reviews International 38: 846 – 65. 10.1080/87559129.2021.1889581

- 26.Percudani R, Trevisi A, Zambonelli A, Ottonello S. Molecular phylogeny of truffles (Pezizales: Terfeziaceae, Tuberaceae) derived from nuclear rDNA sequence analysis. J Mol Phylogenetics Evol 13: 169 – 80. 1999. 10.1006/mpev.1999.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Awameh MS, Alsheikh A. Features and analysis of spore germination in the brown Kame Terfezia Claveryi. J Mycologia. 1980a;72:494–99. 10.1080/00275514.1980.12021210. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slama A, Fortas Z, Boudabous A, Neffati M. (2014) Study on ascospores germination of a Tunisian desert truffle, Terfezia boudieri Chatin. Journal of Materials and Environmental Science. 2014. 5(6); 1902–1905.

- 29.Botton B, Breton A, Fèvre M. (1990). Moisissures utiles et nuisibles: Importance industrielle. Masson Paris. http://tinyurl.com/4efw5vpa

- 30.Awameh MS, Alsheikh A. (1980) Ascospore Germination of Black Kamé (Terfezia Boudieri). Mycologia, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 50–54. JSTOR. 10.2307/3759418

- 31.Nadim M, Saidi N, Hasani I, El Banna Y, Samir O, Assad MEH, Shamekh S. Effects of some environmental parameters on mycelia growth of Finnish truffle Tuber maculatum. Int J Eng. 2016;3:2394–3661. http://tinyurl.com/msns6cmc. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gwon J-H, Park H, Eom A-H. Effect of Temperature, pH, and media on the mycelial growth of Tuber Koreanum. J Mycobiology. 2022;50:238–43. 10.1080/12298093.2022.2112586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamal S. (2011) Published. Proceedings of the 7th International conference on mushroom biology and mushroom products (ICMBMP7): 509 – 15. http://tinyurl.com/38cpbh62.

- 34.Hu SQ, Yang X, Wei W, Guo X. Study on the ecological environmental conditions of truffle with analysis of biomaterials. J Adv Mater Res. 2013;648:389–93. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.648.389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ceccaroli P, Saltarelli R, Cesari P, Zambonelli A, Stocchi V. Effects of different carbohydrate sources on the growth of Tuber borchii Vittad. Mycelium strains in pure culture. J Mol. 2001;218:65–70. 10.1023/A:1007265423786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.