Abstract

The fly glial cell deficient/glial cell missing (glide/gcm) gene codes for a transcription factor that induces gliogenesis. Lack of its product eliminates lateral glial cells in the embryonic nervous system. Here we identify a second gene, glide2, that is homologous to glide/gcm in the binding domain and that is also necessary and sufficient to promote glial differentiation. glide2 codes for a transcription factor that displays a weaker and delayed expression compared with glide/gcm. The two genes, which are located 27 kb apart and share cis-regulatory elements, are able to auto- and cross-regulate, indicating that they form a gene complex. Finally, we show that lack of both products eliminates all lateral glial cells, which means that the two genes contain all the fly lateral glial promoting activity.

Keywords: fly/glial cells/Glide2/Glide/Gcm/transcription factor

Introduction

The glial cell deficient/glial cell missing (glide/gcm) gene codes for a transcription factor that induces gliogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster embryonic and adult nervous system (Hosoya et al., 1995; Jones et al., 1995; Akiyama et al., 1996; Vincent et al., 1996; Bernardoni et al., 1997, 1998, 1999; Schreiber et al., 1997, 1998; Akiyama-Oda et al., 1998, 1999, 2000a,b; Miller et al., 1998; Granderath et al., 2000; Van De Bor et al., 2000; Ragone et al., 2001; Van De Bor and Giangrande, 2001). In the embryonic central nervous system (CNS), it is transiently expressed in all the precursors of lateral glial cells, but not in midline glial cells, for which the promoting factor is still to be determined. Lack of Glide/Gcm results in the absence of lateral glial cells, which are transformed into neurons. Conversely, ectopic expression leads to glial differentiation at expense of other cell types, indicating that glide/gcm is sufficient to induce the glial fate (Hosoya et al., 1995; Jones et al., 1995; Vincent et al., 1996; Akiyama-Oda et al., 1998; Bernardoni et al., 1998).

The observation that glide/gcm does not affect all lateral glial cells, as well as the lack of promoting factors for mid line cells, prompted us to ask whether genes homologous to glide/gcm are required in these processes. Interestingly, a second fragment containing the so-called gcm motif has been identified in the fly genome (Akiyama et al., 1996), suggesting that a glide/gcm-like gene might exist. This is in agreement with the finding that two genes of the gcm family have been so far identified in each species, from rodents to humans (Akiyama et al., 1996; Kammerer et al., 1999). The two genes, also called gcmA and gcmB, display homology only within the gcm motif (Akiyama et al., 1996; Kammerer et al., 1999).

Here we show that a glide/gcm homologue, glide2, is located 27 kb upstream of glide/gcm in the 30B region. glide2 codes for a transcription factor that is able in vitro to activate glide/gcm as well as its own expression. We also show that glide/gcm regulates glide2 expression in vivo and in vitro, and that the two genes share regulatory sequences. Like glide/gcm, glide2 is sufficient to induce gliogenesis within and outside the nervous system. Moreover, like glide/gcm, it is expressed in lateral but not in midline glial cells, and is required for the differentiation of these cells. Finally, lack of both products eliminates all lateral glial cells, indicating that the 30B locus contains all the information that is necessary to induce the lateral glial fate.

Results

Organization of the 30B locus

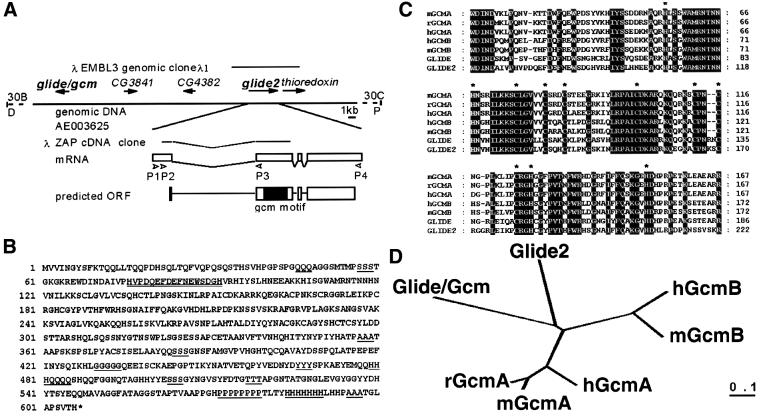

The existence in the fly genome of a 141 bp fragment homolog to the gcm motif (Akiyama et al., 1996) prompted us to analyze the putative role and profile of expression of the gene containing this sequence. At first we used the fragment to generate probes and screen fly libraries. One genomic clone covering 11 kb of what we called the glide2 locus, as well as an 863 bp clone containing a partial cDNA, were obtained and characterized. Sequences were then compared with those provided by the Fly Genome Project (Adams et al., 2000). Locus and gene structure, as well as the predicted amino acid sequence, are shown in Figure 1A and B. The glide2 gene maps at 30B and is located 27 kb 5′ to the glide/gcm gene, the two genes being disposed head to head (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank locus accession number AE003625). Some 480 bp downstream of glide2 is located a gene homologous to thioredoxin (M.Kammerer and A.Giangrande, in preparation) whereas two predicted genes are located between glide/gcm and glide2 (Figure 1A). No expressed sequence tags (ESTs) have been recovered for such genes in embryonic libraries. Their predicted open reading frames (ORFs) have some similarity with esterase-like proteins and are not related to the glide/gcm family. One member of this protein family, Gliotactin, is required for the formation of the blood–brain barrier, but not to promote gliogenesis (Auld et al., 1995).

Fig. 1. Organization of the glide2 locus and comparison amongst glide/gcm genes throughout evolution. (A) The glide2 locus. Line at the top represents the genomic clone (λEMBL3). The 30B locus is shown below. Arrows indicate transcribed sequences. The structure of the glide2 cDNA clone is indicated below the genomic fragment (λZAP). Open rectangles below the cDNA clone indicate the four exons that constitute the glide2 transcribed sequences. Arrowheads indicate oligonucleotides used in RT–PCRs. Open rectangles at the bottom indicate the predicted ORF, the black rectangle shows the gcm motif. (B) Predicted amino acidic sequence for the glide2 gene. Double underlining indicates the putative PEST motif. Single underlining depicts the homopolymeric amino acid stretches. (C) Sequence alignment of fly, human, mouse and rat proteins in the gcm motif. Black boxes indicate conserved amino acids, asterisks indicate the conserved histidine and cysteine residues. (D) Phylogenetic tree of Gcm family. Phylogenetic tree according to multiple sequence alignments was determined using PHYLIP calculations (Joe Felsenstein). Bar represents number of substitutions per site.

Structure of the glide2 gene

Computational analysis on the glide2 genomic sequence predicts the existence of a gene containing three exons, however, the 5′ end of our cDNA clone maps upstream of the predicted gene. To determine the structure and the 5′ end of glide2, we performed reverse transcription PCR (RT–PCR) on RNA from wild-type embryos using different oligonucleotide sets (see arrowheads in Figure 1A). This revealed the existence of a glide2 cDNA containing four exons and ∼2.4 kb long. A putative Initiator element (Inr) (Hultmark et al., 1986) is present 58 bp 5′ to oligo nucleotide P1. Such cDNA contains a predicted ORF of 606 amino acids, with a deduced molecular weight of 65 kDa (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession number AF184664). This protein sequence differs from the 613 amino acid protein proposed in the FlyBase Genome Annotation Database of Drosophila (GadFly) (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession number AAF52793) in the first four amino acid residues. The first exon contains an untranslated region of 433 bp (relative to the putative start site in the Inr), as well as the first 11 coding nucleotides. The second exon contains the gcm motif as well as the PEST motif, typical of rapidly degraded proteins (Rogers et al., 1986). Interestingly, the latter motif is conserved throughout evolution in the Gcm family even though the position and the number of PEST vary. Stretches of homopolymeric repeats of glutamine, serine, alanine, glycine, tyrosine, histidine and proline are located in the first 60 and in the last 250 amino acids. Surprisingly, while it has been shown that glide/gcm codes for a transcription factor (Akiyama et al., 1996; Schreiber et al., 1997, 1998; Miller et al., 1998), no clear nuclear localization signal (NLS) could be identified in Glide2. The only other member of the Gcm family devoid of NLS is hGcmA.

The degree of conservation between Glide/Gcm or Glide2 and the different family members is very similar (Figure 1D), which makes it difficult to assign a specific ancestor for gcmA and gcmB. The homology between the two fly genes within the gcm motif, however, is stronger (69%) than that found between any of them and the other members of the family (56–64%). These data suggest that indepedent duplications have taken place in arthropod and vertebrate lineages. Within the motif, Glide2 retains the four cysteines and the seven histidines displaying the same relative spacing H-X11-H-X8-C-X5-C-X3-C-X14-C-X11-C-X2-4-C-X8-9-C-X2-H-X23-H as that found in Glide/Gcm (Akiyama et al., 1996) (Figure 1C). Cysteines within the gcm motif have been shown to be either essential for DNA binding and transactivation or to play a role in the regulation of redox sensitivity to DNA binding (Miller et al., 1998; Schreiber et al., 1998).

glide2 is expressed in lateral glial cells of the embryonic CNS

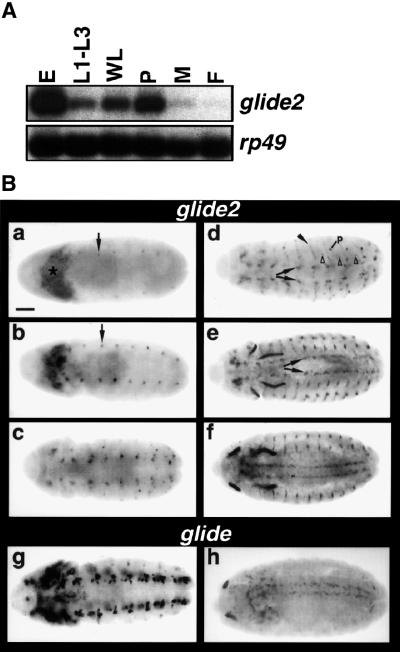

To understand the mode of action of glide2, we analyzed its expression during development. RT–PCRs on total RNA from different stages produced amplification products of the expected size. glide2 expression is first detected in embryos, it decreases during larval stages and peaks again in 1-day pupae (Figure 2A). Almost no RNA is present in adult flies. We also performed in situ hybridization on wild-type embryos using a glide2-specific riboprobe (Figure 2B). Transcripts are first detected at around stage nine in the procephalic mesoderm, the region from which hemocytes take origin, and in one cell per hemisegment, at the position of the neuroglioblast 1–3 lineage (Figure 2B, panel a). The levels of expression, as well as the number of expressing cells in the trunk, increase as development proceeds (Figure 2B, panels b and c). By stage 12, most transcripts are restricted to the nervous system, at the position of glial lineages (Figure 2B, panels c and d). Some expression is also detectable in ectodermal stripes located laterally at the position of apodemal cells (Figure 2B, panel d). No expression was found in midline cells.

Fig. 2. Comparison of glide/gcm and glide2 profile of expression. (A) glide2 expression at different stages. RT–PCR was performed on: embryos (E), first to third instar larvae (L1–L3), wandering larvae (WL), 0–24 h pupae (P), adult males (M) and females (F). rp49 was used to normalize the amount of RNA in each reaction. (B) glide2 expression during embryogenesis and comparison with glide/gcm expression. Ventral views: in this and in following figures anterior is to the left. In situ hybridization on wild-type embryos with a (a–f) glide2- or a (g and h) glide/gcm-specific riboprobe. (a) Expression is first detected at stage 9 in procephalic mesoderm (asterisk) and in one cell of each hemineuromere of the ventral cord (arrow). (b) By stage 10, the levels of expression in the ventral cord have increased. (c) By early stage 12, the expression in the procephalic mesoderm has completely disappeared. The number of glide2 expressing cells in the ventral cord has increased. (d) At mid-stage 12, glide2 starts being expressed in lateral ectodermal stripes along the dorso-ventral axis (arrowhead). Expression is also detectable in cells that correspond, by their position, to longitudinal (arrows) and to other lateral glial cells (open arrow heads). A peripheral cell expressing glide2 is present in each abdominal segment (p). (e) By stage 13, most glial cells have reached their position. glide2 is expressed in the longitudinal glial cells that start to stretch along the longitudinal connectives (arrows). (f) Stage 15. (g) Early stage 12. (h) Stage 15. Bar: 50 µm.

The profiles of glide2 and glide/gcm (Hosoya et al., 1995; Jones et al., 1995; Bernardoni et al., 1997) are very similar, even though glide2 is expressed at much lower level than glide/gcm (Figure 2B, compare panels c and g). Using probes of similar length and the same experimental conditions for the two reactions, we detected glide2 expression after 4 h, whereas glide/gcm expression was detected after a few minutes. This is in agreement with the observation that the glide2-specific signal cannot be detected on northern blots containing 10 µg of poly(A)+ RNA (data not shown). Overall, glide2 expression is delayed compared with that of glide/gcm, which is already detected at the end of the blastoderm stage (Jones et al., 1995; Bernardoni et al., 1997) and fades by stage 15 (Figure 2B, compare f with h).

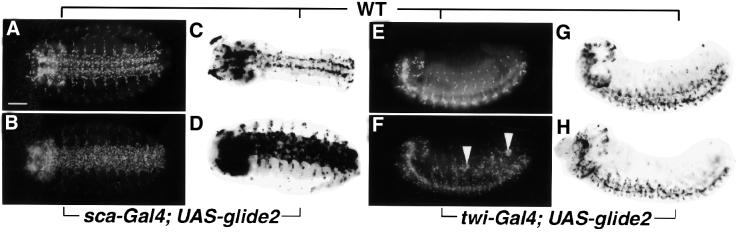

Glide2 is sufficient to induce glial differentiation

glide2 expression profile suggested a role in glial differentiation; we therefore tested whether glide2 is able to induce gliogenesis. Using scabrous (sca–Gal4) and twist (twi–Gal4) drivers, we expressed glide2 throughout the neurogenic region and in the mesoderm, respectively. In both cases, we observed ectopic gliogenesis, as revealed by labeling with anti-Repo, an antibody that recognizes all lateral embryonic glial cells (Campbell et al., 1994; Xiong et al., 1994; Halter et al., 1995) (Figure 3A, B, E and F). Thus, as for Glide/Gcm (Hosoya et al., 1995; Jones et al., 1995; Akiyama-Oda et al., 1998; Bernardoni et al., 1998), Glide2 is sufficient to induce the glial fate, irrespective of the cell type in which it is expressed.

Fig. 3. glide2 ectopic expression induces glial differentiation. (A–D) Ventral views of stage 15 embryos (E–H). Lateral views of stage 13 embryos. (A, B, E and F) Anti-Repo labeling. (C, D, G and H) glide/gcm expression. (A, C, E and G) Wild type (WT). (B and D) sca–Gal4; UAS–glide2. (F and H) twi–Gal4; UAS–glide2. (A–D) Repo protein and glide/gcm RNA are ectopically expressed in the ventral cord of sca–Gal4; UAS–glide2 compared with wild-type embryos. (E–H) Note that twi–Gal4; UAS–glide2 induces mesodermal Repo but not glide/gcm expression. Arrowheads in (F) show lateral clusters of Repo-positive cells absent in wild type. Bar: 50 µm.

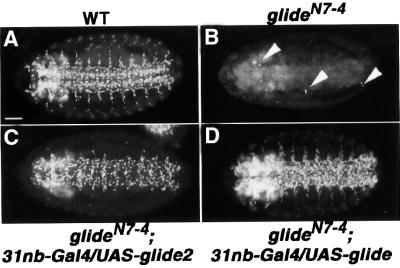

Given the similar phenotype obtained with the two genes, we asked whether the effects shown in Figure 3 were due to ectopic activation of glide/gcm. By using a glide/gcm-specific probe we found that glide2 expression in the neurogenic region does induce glide/gcm (Figure 3C and D) whereas mesodermal glide2 expression does not (Figure 3G and H), indicating that the Glide2 protein is sufficient to promote gliogenesis. To confirm that glide2 does not require glide/gcm, we also induced ectopic expression in a null mutant, glide/gcmN7-4, which misses most lateral glial cells (Figure 4B). Indeed, neuroblast glide2 expression leads to massive ectopic Repo in the CNS of glide/gcmN7-4 embryos (Figure 4C). When glide/gcm is induced in the same background and using the same driver, ectopic gliogenesis was observed, as expected (Figure 4D). Interestingly, Glide/Gcm induces more glial cells than Glide2.

Fig. 4. glide2 ectopic expression induces glial differentiation independently of glide/gcm. Ventral views of stage 15 embryos, anti-Repo labeling. (A) Wild type (WT), (B) glideN7-4, (C) glideN7-4; 31nb-Gal4/UAS–glide2, (D) glideN7-4; 31nb-Gal4/UAS–glide. Arrowheads indicate the few Repo-positives present in glideN7-4. Ectopic expression of glide2 in all neuroblasts induces massive ectopic Repo labeling in a glide/gcm null context (C). Note that ectopic expression of glide/gcm in the same context induces more ectopic Repo labeling than that observed with glide2. Bar: 50 µm.

These results altogether demonstrate that (i) glide2 is sufficient to induce gliogenesis, (ii) glide2 can induce glide/gcm expression, and (iii) glide2 can induce gliogenesis directly, without glide/gcm.

glide2 codes for a transcription factor

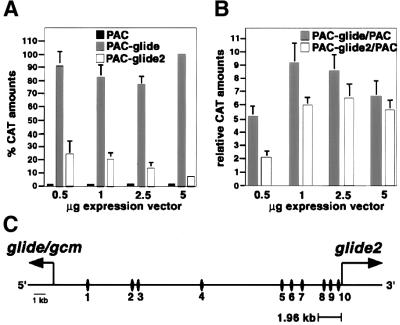

glide/gcm codes for a transcription factor that binds to the Glide/Gcm binding site (GBS) and thereby activates target genes (Akiyama et al., 1996; Schreiber et al., 1997, 1998; Miller et al., 1998; Granderath et al., 2000). Given the structure of Glide2 and its ability to induce glide/gcm, we asked whether it behaves as a transcription factor. To do this, we co-transfected a glide2 expression vector with a chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) reporter containing a GBS (5′-ATGCGGGT-3′) in front of the thymidine kinase (tk) promoter fused to the CAT coding sequence (Figure 5A). Transactivation was quantified by measuring the amounts of CAT protein. The results were compared with those obtained with an expression vector containing glide/gcm coding sequences or with an expression vector that does not contain any insert. Transactivation assays were performed by using different amounts of expression vector. As expected, glide/gcm expression results in the activation of transcription, which was arbitrarily given a 100% value. Glide2 also induces transcription, compared with the results obtained with the ‘empty’ transcription vector. Glide2, however, is weaker compared with Glide/Gcm. Moreover, its transactivation potential decreases as the amount of protein increases: 0.5 µg of glide2 expression vector lead to a congruous activation (25%) whereas 5 µg of the same vector lead to very weak activation (<10%).

Fig. 5. glide2 encodes a transcription factor. (A) The reporter construct pBLCAT5-GBS-C was co-transfected in S2 cells with increasing amount of PAC, PAC–glide/gcm (PAC–glide) or PAC–glide2 (PAC–glide2). GBS contained in pBLCAT5-GBS-C corresponds to site 1 in (C). Results are given in percentage of CAT amounts. The level of activation observed when the reporter is co-transfected with 5 µg of PAC–glide/gcm was arbitrarily assigned the 100% value. (B) The reporter construct pBLCAT6-1.96 containing 1.96 kb of the glide2 promoter was co-transfected in S2 cells with increasing amount of PAC, PAC–glide/gcm or PAC–glide2. Results are given in relative CAT amounts obtained upon comparison with those induced by PAC. (C) Schematic drawing of the 27 kb region contained between glide/gcm and glide2. Vertical ovals indicate the position of the ten sites corresponding to the GBS consensus. GBS numbers 1, 6 and 8 are in 3′→5′ orientation whereas GBS numbers 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9 and 10 are in 5′→3′ orientation. Site 1 on this map corresponds to site C in Miller et al. (1998).

In a second co-transfection assay, we used a fragment containing three GBSs (Figure 5B). In this context, Glide2 and Glide/Gcm showed similar transactivation potentials when >2.5 µg of expression vector were transfected. The 1.96 kb fragment used in this test is located in the glide2 promoter, suggesting that glide2 expression depends on a feedback loop and/or on cross-regulation from Glide/Gcm. Indeed, the 27 kb fragment separating the two genes contains many GBS consensus [5′-AT(G/A)CGGG(T/C)-3′], most of which are located closer to glide2 than glide/gcm transcription start site. The map in Figure 5C shows the position of the predicted GBS consensus sequences as well as the 1.96 kb fragment used for CAT assays. It should be noted that this map only shows the sites that are homologous to either of the four consensus sequences or those that carry a mismatch in the first or in the last position, which have been shown to affect binding very weakly (Akiyama et al., 1996; Schreiber et al., 1998). These are the most effective GBSs. For the sake of simplicity, sites containing mismatches at other positions were omitted, even though previous work from our and others’ laboratories have shown that they induce moderate but consistent gene expression (Miller et al., 1998; Schreiber et al., 1998). The in vitro and in vivo data indicate that Glide2 is a transcription factor and that it activates glide/gcm expression. They also indicate that Glide/Gcm is a more potent transcription factor than Glide2, thus explaining the quantitative differences observed in ectopic expression experiments (Figure 5).

Although the presence of binding sites cannot be taken as an evidence for direct regulation, it is interesting to note that the two predicted genes are located between sites 3 and 5 and are separated by site 4. Further analyses will be required to define the profile of expression of such genes and to determine whether they are targets of Glide-like molecules.

Regulation of glide2 by glide/gcm

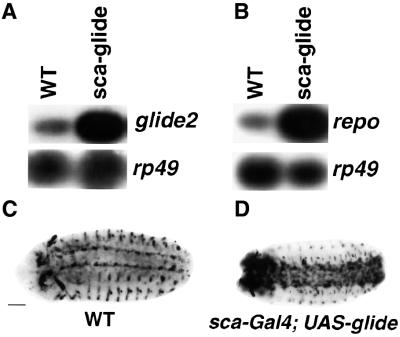

The observation that glide2 regulates glide/gcm expression, as well as the localization of the two genes in the same region, prompted us to ask whether glide/gcm regulates glide2 in vivo. In order to answer this question, we analyzed the effects of loss- and gain-of-function glide/gcm mutations on the expression of glide2. By performing RT–PCR, we found an increase of glide2 expression in embryos that express glide/gcm throughout the neurogenic region (Figure 6A). The increase of glide2 expression is comparable with that observed with repo (Figure 6B). The activation of glide2 by glide/gcm was further confirmed by in situ experiments with glide2-specific probes on wild-type and sca-glide/gcm embryos (Figure 6C and D). Massive ectopic glide2 expression is present in sca-glide/gcm embryos, the labeling being limited to the neurogenic region, in which glide/gcm has been induced. These results, together with the transfection assays, strongly suggest that glide/gcm directly induces glide2 expression. They also explain why glide2 expression is slightly delayed compared with that of glide/gcm.

Fig. 6. glide/gcm ectopic expression induces ectopic glide2 expression. (A) glide2 and (B) repo expression in a glide/gcm gain-of-function context. RT–PCRs were performed on wild-type (WT) or sca–Gal4; UAS–glide (sca–glide) overnight embryos. rp49 was used as above. (C and D) Stage 13, ventral views: glide2 expression detected by in situ hybridization. (C) Wild type (WT), (D) sca–Gal4; UAS–glide. glide2 RNA is ectopically expressed in the ventral cord of sca–Gal4; UAS–glide embryo. Bar: 50 µm.

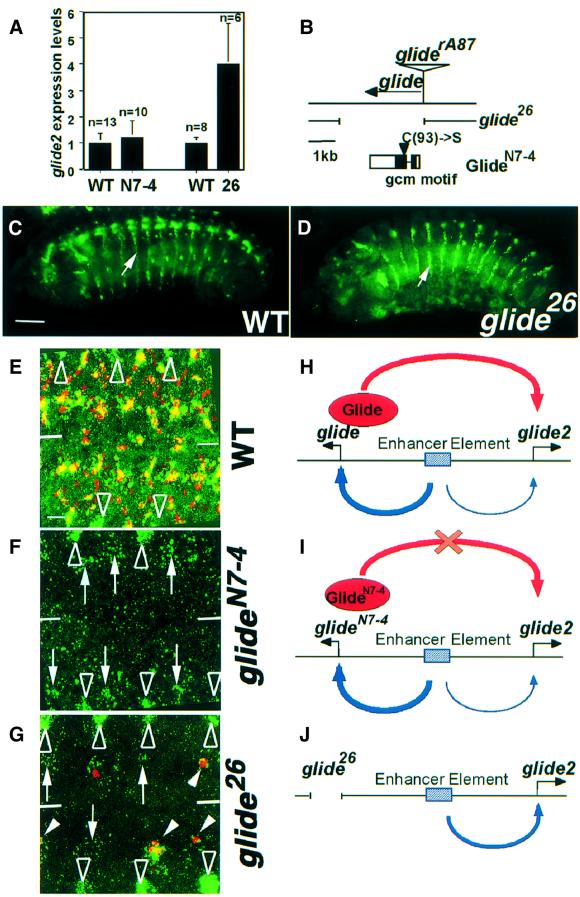

We also analyzed glide2 expression in two glide/gcm null mutations, glide/gcmN7-4 and glide/gcm26, which were generated by DEB (Lane and Kalderon, 1993) and P element excision, respectively (Vincent et al., 1996) (Figure 7A and B). The insertion in the line used for P mutagenesis, glide/gcmrA87, was defined by genomic DNA sequencing as being at –82 bp from the transcription start site, which was identified by S1 mapping (A.A.Miller and A.Giangrande, unpublished data). glide/gcmN7-4 is a point mutation that eliminates DNA binding, whereas glide/gcm26 contains a deletion covering all transcribed sequences as well as the first 82 bp in the 5′ promoter and 1020 bp 3′ to the gene. Individual embryos were selected by using blue balancers and submitted to RT–PCR. Interestingly, we found that glide2 expression is not severely affected in glide/gcmN7-4 embryos, while it is increased (4-fold induction) in glide/gcm26. These intriguing results prompted us to analyze the spatial distribution of glide/gcm transcripts by in situ hybridization. Much to our surprise, we found that most of the glide2-specific signal is absent in the ventral cord of glide/gcmN7-4 embryos, whereas it is less affected in glide/gcm26. In glide/gcmN7-4, very few cells still express glide2, the level being much lower than in the wild type (Figure 7E and F). In glide/gcm26 embryos, more cells express it; in addition, the level of glide2 expression is rather high, as confirmed by the fact that some of them enter the glial pathway and also express repo (Figure 7G). Our in situ results also indicate that glide2 regulation is tissue-specific, since the expression in the lateral stripes is not induced by glide/gcm (Figure 7C and D). Indeed, lateral stripes show stronger labeling in glide/gcm26 than in wild-type embryos, which explains why glide2 RNA levels are increased in RT–PCR experiments. Thus, glide/gcm at least partially controls glide2 expression.

Fig. 7. glide2 expression is impaired in glide/gcm null mutants. (A) glide2 expression in glide/gcm loss-of-function mutations. RT–PCRs were performed on RNA from single wild-type (WT) or glide/gcm stage 12 embryos. Two null alleles were analyzed, glide26 (26) or glideN7-4 (N7-4). The levels of expression in mutant embryos were compared with those observed in WT embryos, which were arbitrarily assigned the value of one. n indicates the number of embryos analyzed for each genotype. (B) Schematic drawing showing the mutations at the glide/gcm locus. Horizontal arrow indicates the transcribed sequences. gliderA87 P element insertion site is shown by the inverted triangle. Deletion in glide26 is indicated by the interrupted line. Open rectangles indicate the predicted ORF and black boxes show the gcm motif. Vertical arrowhead indicates the substitution occurring in GlideN7-4. (C and D) Lateral views of late stage 12 embryos, in situ hybridization with a glide2-specific riboprobe. (C) Wild-type (WT), (D) glide26. Note the increased expression of glide2 in lateral stripes in glide26 compared with wild type (see arrows). (E–G) Ventral views of abdominal segments, confocal images. In red, anti-Repo labeling, in green, glide2 riboprobe. (E) Wild type (WT), (F) glideN7-4, (G) glide26. Lines indicate the position of the midline. Empty arrowheads indicate the position of lateral stripes. Arrows indicate cells expressing glide2 in the ventral cord. White arrowheads indicate cells co-expressing glide2 and Repo. (H) Model of glide2 regulation in a wild-type background. In (I and J), models of glide2 regulation in glideN7-4 and glide26, respectively. Horizontal line represents the genomic region containing glide/gcm and glide2. Black arrows indicate transcribed sequences. Blue box represents the enhancer element common to glide/gcm and glide2. Blue arrows indicate relative contribution of this element to glide/gcm and glide2 expression. Red oval represents the Glide/Gcm protein, red arrow the contribution of Glide/Gcm to glide2 transcription. Interrupted line in (J) represents the deleted sequences in glide26. The red cross in (I) indicates that the GlideN7-4 protein is unable to activate glide2 expression. Bars: (C and D) 50 µm, (E–G) 10 µm.

Glide2 is required for glial differentiation

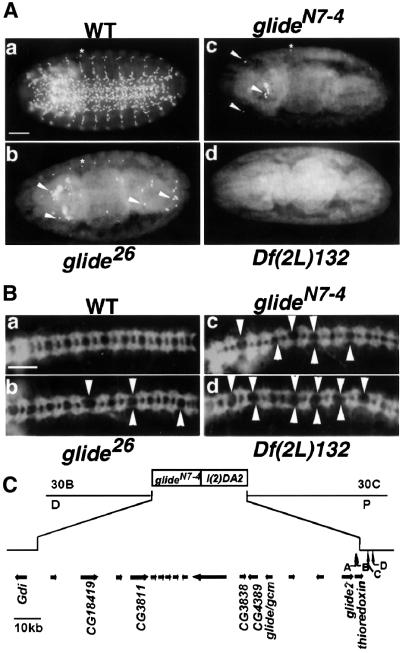

By performing PCR on genomic DNA, we established that glide2 resides within the Df(2L)132 (Lane and Kalderon, 1993). We found that this deficiency spans ∼115 kb and covers two lethal complementation groups, glide/gcmN7-4 and, more proximally, l(2)DA2. No known genes affecting glial differentiation are contained within the deficiency. Df(2L)132 completely lacks Repo labeling in embryonic PNS and CNS (Figure 8A, panel d) whereas glide/gcm null mutants, which partially affect glide2 expression, still retain some Repo labeling (see panels b and c in Figure 8A). In particular, 36 and 40 repo-positive cells were found, respectively, in the cord and in the head of glide/gcm26 embryos (n = 10) whereas three and seven were found in glide/gcmN7-4 embryos (n = 10). This further confirms that glide2 is required for gliogenesis. Interestingly, the amount of Repo-positive cells directly correlates with the levels of glide2 expression previously observed in the mutants, the lowest value being in the deficiency, the highest in glide/gcm26. Moreover, glide/gcm26 and glide/gcmN7-4 embryos also display weaker axonal defects compared with those observed in the deficiency, as shown by labeling with several axon-specific antibodies. Indeed, breaks in the longitudinal commissures, as well as abnormal fasciculation in the intersegmental and segemental nerves, were more often seen in the deficiency than in glide/gcm mutants (Figure 8B and data not shown). This substantiates the role of glide2 in the differentiation of glial cells, which are necessary to maintain the axon scaffold (Hosoya et al., 1995; Vincent et al., 1996). Although we cannot formally exclude the possibility that genes contained in the deficiency might somehow act in glial differentiation and axonal navigation, the results obtained with this mutant are in agreement with all the other in vivo and in vitro data and support the hypothesis that glide2 and glide/gcm act in concert to promote glial differentiation.

Fig. 8. glide2 is required for glial differentiation. (A) Stage 15 embryos from the following genotypes labeled with an anti-Repo antibody: (a) wild type (WT), (b) glide26, (c) glideN7-4, (d) Df(2L)132. Note that in (b) the number of Repo-positive nuclei is dramatically decreased, but glial cells are still present in the head and in the ventral cord (arrowheads). (c) A few glial cells are detectable in the head (arrowheads). (d) No Repo-positive cells are detectable in the CNS of this embryo. The lateral bipolar dendritic cell normally present in all segments, see asterisk in (a–c), is also missing in the double mutant. (B) Stage 15 embryos from the following genotypes labeled with an anti-BP102 antibody: (a) wild type (WT), (b) glide26, (c) glideN7-4, (d) Df(2L)132. Arrowheads indicate longitudinal connective breaks. (C) Mutations in the region containing glide/gcm and glide2. Breakpoints for Df(2L)132 were determined by PCR. Boxes show lethal complementation groups. Interrupted line shows the deletion in Df(2L)132. Arrows show predicted genes. Names show ESTs or transcripts found in the embryo. Vertical arrows show P element insertion close to glide2, EP(2)2252 (A), EP(2)2018 (B), EP(2)2433 (C) and EP(2)0361 (D). Bar: 50 µm.

Since glide2 is located proximal to glide/gcm, we asked whether l(2)DA2 corresponds to the glide2 allele. By labeling with the anti-Repo antibody, however, we did not find any mutant phenotype (data not shown). Since Df(2L)132 also lacks thioredoxin, the gene that is proximal to glide2 (see Figure 1A), as verified by PCR with specific primers (data not shown), this means that either the glide2 mutation is not lethal or that previous mutagenesis screens have not saturated the region. Finally, two EP lines (EP(2)2252 and EP(2)2018), three bases apart, are located downstream of glide2. The elements reside in the 5′ untranslated region of thioredoxin, 227 and 224 bp from the coding region. It has previously been shown that antisense transcripts can be generated if an EP element inserts into the transcribed sequence of a gene in an antisense orientation (Rorth et al., 1998). Since the two lines display opposite orientation of the P element, we asked whether any of them had a mutant glial phenotype due to expression of an antisense glide2 RNA. However, no defects were observed in the two lines.

Discussion

Glide2 is a glial promoting factor

Previous studies demonstrated that glide/gcm plays a major role in fly glial differentiation (Hosoya et al., 1995; Jones et al., 1995; Vincent et al., 1996; Akiyama-Oda et al., 1998, 1999, 2000a,b; Bernardoni et al., 1998, 1999; Miller et al., 1998; Granderath et al., 2000; Van De Bor et al., 2000; Ragone et al., 2001; Van De Bor and Giangrande, 2001), however, the presence of some glial cells in the CNS of null mutants suggested that additional gene(s) contribute(s) to gliogenesis. The present study shows that a second fly gene, glide2, codes for a glial promoting factor. Several lines of evidence indicate that Glide/Gcm and Glide2 work together to promote gliogenesis: (i) their similar profile of expression; (ii) the ability of Glide2 to promote gliogenesis when ectopically expressed in vivo; (iii) Glide2 requirement for glial differentiation and its ability to activate transcription through GBSs; and (iv) glide/gcm and glide2 auto- and cross-regulation in vivo and in vitro. When both genes are eliminated, all lateral glial cells are missing, suggesting that the glide/gcm cluster accounts for all lateral glial promoting activity in the fly. The present study also clearly demonstrates that Glide-like activity is not necessary to trigger gliogenesis in the midline.

The functional significance of gene duplication is in many cases still unclear. It is likely that duplicated, dispensable genes are in the process of acquiring novel functions. Interestingly, engrailed mutations are lethal whereas invected mutations are not (Gustavson et al., 1996). Moreover, Engrailed and Invected have distinguishable functions in anterior–posterior patterning of the wing (Simmonds et al., 1995). It is unlikely that glide2 is specifically required in a subtype of glial cells of the embryonic ventral cord, since the glial cells still present in glide/gcm mutants do not show a stereotyped arrangement. This favors the hypothesis that glide2 expression guarantees sufficient levels of Glide-like activity. glide2 could also play a role at later stages in glial proliferation, migration and/or other processes. However, these phenotypes cannot be scored in the absence of glial cells produced by the glide/gcm mutation. For this reason, it will be useful to generate conditional glide/gcm mutants that make it possible to bypass the early requirement for this product during glial differentiation. Finally, glide2 might play a role in the differentiation of the adult central nervous system, where it is also expressed (V.Van De Bor and A.Giangrande, unpublished data).

The observation that glide2 is sufficient to induce gliogenesis raises the question of why this gene is not able to rescue the glide/gcm phenotype. This situation has also been observed in other pairs of genes. For example, the segmentation genes engrailed and invected code for very similar homeobox-containing proteins and show similar profiles of expression (Gustavson et al., 1996). Even though both proteins display comparable repressor activities in transfection assays, Invected is not able to compensate for the lack of Engrailed, most likely due to the fact that its expression is delayed compared with that of engrailed (Gustavson et al., 1996). The expression of glide2 is induced later than that of glide/gcm and therefore it may not be able to compensate for the defect. Moreover, in vitro and in vivo results indicate that glide2 is a less potent activator and a less potent glial promoting factor. Finally, glide2 is expressed at lower levels than glide. This quantitative and qualitative regulation of expression may account for the different behavior.

While it is likely that glide2 does not code for the major glial promoting factor, the present study shows that this gene plays an important role in gliogenesis. Moreover, glide2 contribution to glial differentiation is certainly underestimated, due to the fact that glide/gcm controls at least in part the expression of glide2. Indeed, we have demonstrated that mutants so far considered as being null for glide are in fact also affecting glide2. It will be important to produce mutants that specifically affect glide2. In an effort to generate such mutants we tried to induce local hops using the EP line EP(2)2252 inserted downstream of glide2. Unfortunately, no mutations could be recovered at the glide2 locus, as verified by PCR.

The glide/gcm gene complex

Gene duplication is of central interest to evolutionary developmental biology since it has been implicated in evolutionary increase in complexity (Holland, 1999). A number of duplicated genes in Drosophila are characterized by features that are also shared by glide2 and glide/gcm [engrailed and invected (en/inv; Gustavson et al., 1996), knirps and knirps-related (Rothe et al., 1989; Chen et al., 1998), zerknüllt 1 and 2 (Rushlow et al., 1987), sloppy-paired 1 and 2 (slp1/2; Grossniklaus et al., 1992), gooseberry-distal and gooseberry-proximal (Baumgartner et al., 1987)].

First, duplicated genes display similar or overlapping expression profiles, indicating a functional redundancy in the gene complex (Rushlow et al., 1987; Rothe et al., 1989; Grossniklaus et al., 1992; Gustavson et al., 1996). This is confirmed by the fact that double mutants are stronger than single mutants and that ectopic expression of any of the two genes display similar phenotypes (Grossniklaus et al., 1992; Gustavson et al., 1996; Chen et al., 1998). Secondly, in most cases one gene is expressed earlier than the other (Rothe et al., 1989; Grossniklaus et al., 1992; Gustavson et al., 1996). It has been proposed that, because the embryo develops rapidly, genes required at specific stages must be compact and small. For example, invected is expressed later than engrailed, most likely due to the length of its transcript and to the presence of a 19 kb intron (Gustavson et al., 1996). Similarly, glide/gcm, the expression of which precedes that of glide2, shows a more compact organization and a shorter intron than glide2.

Thirdly, pairs of genes constitute a complex in the sense that expression depends on shared regulatory sequences, as shown for the slp1/2 and the en/inv pairs (Grossniklaus et al., 1992; Gustavson et al., 1996). In the nervous system, the patterning of sensory organs depends on the pattern of proneural genes, achaete and scute, which are simultaneously expressed by groups of cells (the proneural clusters). The complex profile of expression is acquired through shared enhancer-like elements distributed along the gene complex (∼90 kb) (Gomez-Skarmeta et al., 1995). The expression profile, the organization of the two genes and the mutant phenotypes do suggest that shared regulatory sequences are present in the 27 kb that separate glide2 from glide/gcm. Both genes at 30B are able to activate their own transcription and to cross-activate. We previously showed that Glide/Gcm autoregulates in vitro and in vivo (Miller et al., 1998). In the present study we have found that Glide/Gcm also activates glide2 expression and vice versa. Moreover, Glide2 also activates its own expression. Sharing of regulatory sequences takes place no matter how the genes are arranged and how far they are located from one another. glide/gcm and glide2 are organized head to head, engrailed and invected tail to tail, achaete and scute or slp1 and 2 show the same orientation. The achaete/scute and the en/inv genes are separated by several dozen kilobases (Gomez-Skarmeta et al., 1995; Gustavson et al., 1996).

Promoter competition at the glide locus

The characterization of two null mutations, glide/gcm26 and glide/gcmN7-4, has allowed us to clarify the nature of promoter interactions at 30B and also to explain the different behavior of the two alleles. The glide/gcmN7-4 mutation produces an inactive protein, as a consequence, glide2 transcription is severely impaired. On the other hand, deletion of glide/gcm promoter and transcribed sequences (as seen in glide/gcm26) has a milder effect on glide2. The most likely interpretation for these results is that glide2 expression is activated by glide/gcm via the glide binding sites and through a regulatory element that is common to glide/gcm and glide2 (see model in Figure 7). In a wild-type embryo, this element preferentially activates glide/gcm by interacting with its proximal promoter. In glide/gcm26 embryos, however, the proximal promoter of glide/gcm is not available. In its absence, the common regulatory element can only work on the glide2 promoter and activates it more efficiently. This is why glide2 transcription is less affected in glide/gcm26 than in glide/gcmN7-4. Such promoter competition is even more evident outside the nervous system. In the lateral stripes of cells, glide2 expression is higher in glide/gcm26 than in wild-type embryos. Promoter competition also explains why glide2 expression increases as glide/gcm expression declines.

In gene complexes, promoter competition seems to control the spatio–temporal shift of expression, thereby allowing different gene members to acquire specific roles. It can be generated at least in two ways (Ohtsuki et al., 1998). An insulator DNA can specifically block the interaction of a shared enhancer with one gene and not the other. Alternatively, the shared enhancer is equally accessible for the two genes, but prefers the promoter region associated with one of them (Ohtsuki et al., 1998). To understand how promoter competition works in the case of glide/gcm and glide2, we are currently defining the shared enhancer sequences using transgenic lines. It is interesting to notice that, while promoter competition has so far been described for promoters that harbor different core elements, no striking difference as observed between glide/gcm and glide2 promoters, in that they are both devoid of TATA box and downstream promoter element (Dpe) and they both contain an Inr.

Thus, the glide-gcm/glide2 pair constitutes a very interesting model system to study complex interactions of cis-regulatory sequences during the differentiation of the nervous system.

Materials and methods

Isolation and analysis of glide2

Two degenerate oligonucleotides [TGGGCCATGCGCAA(T/C)ACCAA as forward primer and TC(T/G)G(G/T)C(T/C)TTGTCACAGATGGC as reverse primer] in the conserved region were used to amplify a 141 bp fragment specific for glide2 from genomic DNA. This fragment was used to screen a genomic library of an isogenized strain of D.melanogaster (iso1), which is cloned into a λEMBL3 vector (provided by J.Tamkun), as well as a 0–24 h embryonic cDNA λZAPII library (provided by C.S.Thummel). A genomic clone covering 11 kb of the glide2 locus and a single cDNA clone of 863 bp were obtained. Computational analysis on the glide2 locus was realized using the GENE-FINDER program from the CGG at the Sanger Center. Finally, RT–PCRs using oligonucleotides P1 (TCTGCTGCTGCCGCTGCTGCTCTT), P2 (GCCCAGTGGATACAAGTGTCGCCT), P3 (CGTCTTGAAGCTGTAGCCATT) and P4 (GGTGTCCGGATTGGTTAAGTACTA) were performed to characterize glide2 cDNA organization. Homology searches were carried out using the BLAST program (Altschul et al., 1997). Searches for transcription factor binding sites were carried out using the MatInspector program against the TRANSFAC database (Heinemeyer et al., 1999). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the PHYLIP package (Joe Felsenstein, University of Washington).

RNA preparation and quantitative RT–PCR

RNA was prepared using TRIzol Reagent, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RT–PCR was performed as described in Huang et al. (1996).

glide2-specific oligonucleotides were GCGTGCGCAATTCAGTTCAATCCA as forward primer and GATCCGTTGGCTGACTTTCCAGCC as reverse primer.

LacZ-specific oligonucleotides were GGCGTTACCCAACTTAATCG as forward primer and TCGCGGAAACCGACATGGC as reverse primer.

repo-specific oligonucleotides were CGGTGGTTAATGGCACCACCA as forward primer and GTTCCGCCGTCTGATAGCTGC as reverse primer.

rp49-specific oligonucleotides were TCCTACCAGCTTCAAGATGAC as forward primer and GTGTATTCCGACCACGTTACA as reverse primer.

Specific conditions for quantitative RT–PCR included an initial denaturing step of 1 min at 95°C followed by incubation at 94°C for 10 s, at 65°C for 15 s and at 72°C for 30 s. After 23 cycles, extension was at 72°C for 10 min followed by a 4°C soak. Primer concentration in the multiplex PCR was 1 µM for glide2 or repo and 0.2 µM for rp49. RT–PCR products were separated on 1.2% agarose gel and transferred on nylon membranes. Blots were hybridized with randomly primed 32P-labeled probes. Signal quantitation was performed on a Fujix Bas 2000.

Cell transfection and CAT ELISA assay

A 1958 bp HindIII–PstI fragment from the λ1 recombinant phage was subcloned in pBLCAT6 (pBLCAT6-1.96), a CAT reporter devoid of tk promoter sequences. This fragment contains both glide2 proximal promoter sequences and a transcription start site. Reporter vector pBLCAT5-GBS-C as well as expression vectors pPAC5C (gift from C.Thummel, which we refer to as pPAC) and pPAC-glide/gcm are described in Miller et al. (1998).

Transient transfection of the Drosophila cell line S2 (Schneider, 1972) was performed according to Di Nocera and Dawid (1983) with 15 µg DNA containing the following: 1 µg pCMV-lacZ, 500 ng pBLCAT6-1.96 or 1 µg pBLCAT5-GBS-C, 0–5 µg pPAC, pPAC-glide/gcm or pPAC-glide2 and SK as carrier DNA. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and normalized for β-Gal activity. CAT levels were determined using the CAT ELISA kit (Boehringer).

Stocks

Wild-type stock was Sevelen. glide/gcm26 and glide/gcmN7-4 were described in Vincent et al. (1996). Df(2L)132 was provided by D.Kalderon. l(2)DA2 was described in Lane and Kalderon (1993). The UAS–glide/gcm transgenic line M24A/CyO twi-lacZ; M21G/M21G is described in Bernardoni et al. (1998). The UAS–glide2 plasmid was obtained by inserting a 4.1 kb fragment of the glide2 locus into pCasper UAST. Transgenic flies were obtained by injecting the plasmid into w1118 animals. UAS–glide/gcm or UAS–glide2 were crossed with twi–Gal4 (Baylies and Bate, 1996), sca–Gal4 (M.Mlodzik’s gift) or the neuroblast specific driver 31nb-Gal4 (L.Seugnet’s gift). Genotypes were recognized by using blue balancers.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

In situ hybridization was performed as in Bernardoni et al. (1999). Digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes were prepared using a 1.6 kb fragment in the 5′ region of the glide2 cDNA and the full-length glide/gcm cDNA (Bernardoni et al., 1999). Signal was detected using an anti-DIG antibody conjugated to the Alcaline Phosphatase and revealed with BCIP/NBT (Boehringer) or the TSA Fluorescein system (NEN).

Embryos were immunolabeled as described in Vincent et al. (1996). Antibodies against Repo (A.Travers’s gift) and β-Gal (Sigma) were used at 1:1000 and BP1O2 (DSHB) at 1:100. Secondaries conjugated with Cy3 or FITC (Jackson) were used at 1:400.

Preparations were analyzed using conventional (Axiophot2, Zeiss) or confocal (DMRE, Leica) microscopes.

Molecular characterization of gliderA87, glide26 and Df(2L)132

glide26 was obtained by imprecise excision from the gliderA87 line (Vincent et al., 1996), which contains an insertion at –82 bp from the transcription start site, which was defined by S1 mapping. Deletion extent in glide26 and Df(2L)132, as well as the position of the P element, were assessed by PCR, as in Miller et al. (1998).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank A.Travers, J.Tamkun, C.S.Thummel, D.Kalderon, M.Bates, M.Mlodzik, L.Seugnet and the Bloomington Center for antibody, genomic and cDNA libraries and flies. We thank R.Walther for the molecular characterization of glide26 and for excellent technical assistance and A.Miller for mapping the glide/gcm start site. Thanks to J.L.Vonesh and D.Hentsch for help with confocal microscope and imaging. Confocal microscopy was developed with the aid of a subvention from the French MESR (95.V.0015). We thank all the members of the group for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg, the Human Frontier Science Program and the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer. M.K. was supported by BDI (CNRS) and European Leucodystrophies Association fellowships.

References

- Adams M.D. et al. (2000) The genome of Drosophila melanogaster.Science, 287, 2185–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y., Hosoya,T., Poole,A.M. and Hotta,Y. (1996) The gcm-motif: A novel DNA-binding motif conserved in Drosophila and mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 14912–14916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama-Oda Y., Hosoya,T. and Hotta,Y. (1998) Alteration of cell fate by ectopic expression of Drosophila glial cell missing in non-neural cells. Dev. Genes Evol., 208, 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama-Oda Y., Hosoya,T. and Hotta,Y. (1999) Asymmetric cell division of thoracic neuroblast 6-4 to bifurcate glial and neuronal lineage in Drosophila.Development, 126, 1967–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama-Oda Y., Hotta,Y., Tsukita,S. and Oda,H. (2000a) Mechanism of glia-neuron cell-fate switch in the Drosophila thoracic neuroblast 6-4 lineage. Development, 127, 3513–3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama-Oda Y., Hotta,Y., Tsukita,S. and Oda,H. (2000b) Distinct mechanisms triggering glial differentiation in Drosophila thoracic and abdominal neuroblast 6-4. Dev. Biol., 222, 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schaffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld V.J., Fetter,R.D., Broadie,K. and Goodman,C.S. (1995) Gliotactin, a novel transmembrane protein on peripheral glia, is required to form the blood-nerve barrier in Drosophila. Cell, 81, 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner S., Bopp,D., Burri,M. and Noll,M. (1987) Structure of two genes at the gooseberry locus related to the paired gene and their spatial expression during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes Dev., 1, 1247–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylies M.K. and Bate,M. (1996) twist: a myogenic switch in Drosophila.Science, 272, 1481–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardoni R., Vivancos,V. and Giangrande,A. (1997) glide/gcm is expressed and required in the scavenger cell lineage. Dev. Biol., 191, 118–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardoni R., Miller,A.A. and Giangrande,A. (1998) Glial differ entiation does not require a neural ground state. Development, 125, 3189–3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardoni R., Kammerer,M., Vonesch,J.L. and Giangrande,A. (1999) Gliogenesis depends on glide/gcm through asymmetric division of neuroglioblasts. Dev. Biol., 216, 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G., Göring,H., Lin,T., Spana,E., Andersson,S. and Doe,C.Q. (1994) RK2, a glial-specific homeodomain protein required for embryonic nerve cord condensation and viablity in Drosophila. Development, 120, 2957–2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.-K., Kühnlein,R.P., Eulenberg,K.G., Vincent,S., Affolter,M. and Schuh,R. (1998) The transcription factors KNIRPS and KNIRPS RELATED control cell migration and branch morphogenesis during Drosophila tracheal development. Development, 125, 4959–4968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nocera P.P. and Dawid,I.B. (1983) Transient expression of genes introduced in cultured cells of Drosophila.Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 7095–7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Rodriguez,I., Martinez,C., Culi,J., Ferres-Marco,D., Beamonte,D. and Modolell,J. (1995) Cis-regulation of achaete and scute: shared enhancer-like elements drive their coexpression in proneural clusters of the imaginal discs. Genes Dev., 9, 1869–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granderath S., Bunse,I. and Klämbt,C. (2000) gcm and pointed synergistically control glial transcription of the Drosophila gene loco.Mech. Dev., 91, 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus U., Kurth Pearson,R. and Gehring,W.J. (1992) The Drosophila sloppy paired locus encodes two proteins involved in segmentation that show homology to mammalian transcription factors. Genes Dev., 6, 1030–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavson E., Goldsborough,A.S., Ali,Z. and Kornberg,T.B. (1996) The Drosophila engrailed and invected genes: partners in regulation, expression and function. Genetics, 142, 893–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halter D.A., Urban,J., Rickert,C., Ner,S.S., Ito,K., Travers,A.A. and Technau,G.M. (1995) The homeobox gene repo is required for the differentiation and maintenance of glia function in the embryonic nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. Development, 121, 317–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer T. et al. (1999) Expanding the TRANSFAC database towards an expert system of regulatory molecular mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P.W.H. (1999) Gene duplication: past, present and future. Semin.Cell Dev. Biol., 10, 541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya T., Takizawa,K., Nitta,K. and Hotta,Y. (1995) glial cell missing: a binary switch between neuronal and glial determination in Drosophila.Cell, 82, 1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Fasco,M.J. and Kaminsky,L.S. (1996) Optimization of DNaseI removal of contaminating DNA from RNA for use in quantitative RNA-PCR. Biotechniques, 20, 1012–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultmark D., Klemenz,R. and Gehring,W.J. (1986) Translational and transcriptional control elements in the untranslated leader of the heat-shock gene hsp22.Cell, 44, 429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.W., Fetter,R.D., Tear,G. and Goodman,C.S. (1995) glial cell missing: a genetic switch that controls glial versus neuronal fate. Cell, 82, 1013–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer M., Pirola,B., Giglio,S. and Giangrande,A. (1999) GCMB, a second human homolog of the fly glide/gcm gene. Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 84, 43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M.E. and Kalderon,D. (1993) Genetic investigation of cAMP-dependant protein kinase function in Drosophila development. Genes Dev., 7, 1229–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.A., Bernardoni,R. and Giangrande,A. (1998) Positive autoregulation of the glial promoting factor glide/gcm. EMBO J., 17, 6316–6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki S., Levine,M. and Cai,H.N. (1998) Different core promoters possess distinct regulatory activities in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev., 12, 547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragone G., Bernardoni,R. and Giangrande,A. (2001) A novel mode of asymetric division identifies the fly neuroglioblast 6-4T. Dev. Biol., 235, 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P. et al. (1998) Systematic gain-of-function genetics in Drosophila.Development, 125, 1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S., Wells,R. and Rechsteiner,M. (1986) Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: the PEST hypothesis. Science, 234, 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe M., Nauber,U. and Jäckle,H. (1989) Three hormone receptor-like Drosophila genes encode an identical DNA-binding finger. EMBO J., 8, 3087–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushlow C., Doyle,H., Hoey,T. and Levine,M. (1987) Molecular characterization of the zernüllt region of Antennapedia gene complex in Drosophila.Genes Dev., 1, 1268–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider I. (1972) Cell lines derived from late embryonic stages of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol., 27, 353–365. [PubMed]

- Schreiber J., Sock E. and Wegner,M. (1997) The regulator of early gliogenesis glial cells missing is a transcription factor with a novel type of DNA-binding domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 4739–4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber J., Enderich,J. and Wegner,M. (1998) Structural requirements for DNA binding of GCM proteins. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 2337–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds A.J., Brook,W.J., Cohen,S.M. and Bell,J.B. (1995) Distinguishable functions for engrailed and invected in anterio-posterior patterning in the Drosophila wing. Nature, 376, 424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van De Bor V., Walther,R. and Giangrande,A. (2000) Some fly sensory organs are gliogenic and require glide/gcm in a precursor that divides symmetrically and produces glial cells. Development, 127, 3735–3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van De Bor V. and Giangrande,A. (2001) Notch signaling represses the glial fate in fly PNS. Development, 128, 1381–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent S., Vonesch,J.L. and Giangrande,A. (1996) glide directs glial fate commitment and cell fate switch between neurones and glia. Development, 122, 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W.C., Okano,H., Patel,N.H., Blendy,J.A. and Montell,C. (1994) repo codes a glial-specific homeodomain protein required in the Drosophila nervous system. Genes Dev., 8, 981–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]