Abstract

Herein, we report an investigation of several synthetic strategies to access the aphidicolin family of natural products. Some unsuccessful approaches include strategies featuring Diels–Alder cycloadditions, Cope rearrangement, divinyl cyclopropane-Cope rearrangement, and C–C cleavage “cut-and-sew” reactions. Separating key bond-forming and bond-breaking steps into a two-step “sew-and-cut” strategy, a penta-carbocycle containing the embedded aphidicolin core was synthesized using an intramolecular [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition reaction—the “sew” step—to obtain a “linear” cycloadduct. Additionally, a constitutional “crossed” isomer of this [2 + 2]-adduct was obtained in a condition-dependent manner, providing insight into factors that can be leveraged to alter [2 + 2]-selectivity for complex substrates. Future application of contemporary C–C cleavage methodologies to facilitate the “cut” step should afford a suitable common intermediate for the synthesis of many members of the aphidicolin family.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Aphidicolin (1, Scheme 1) is a tetracyclic diterpenoid natural product that was first isolated in 1972 by Hesp and co-workers from the fungus Cephalosporium aphidicola—and subsequently isolated from several other fungal species.1–4 Its structure, confirmed unambiguously through a single-crystal X-ray diffraction study, consists of a trans-decalin ring system fused to a bicyclo[3.2.1]octane and features eight stereocenters—two of which are contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenters. Many oxygenated congeners of aphidicolin (e.g., 3–8, Scheme 1) have been isolated, featuring additional oxygenation and unsaturation at many positions on the parent scaffold (see 2). These oxygenated variants include 71 previously unreported congeners recently isolated in 2019 from Botryotinia fuckeliana by Yang and co-workers.4

Scheme 1.

Aphidicolin and Selected Oxygenated Congeners

The parent aphidicolin (1) is a highly selective and moderately potent inhibitor of DNA polymerase α (Pol α) in eukaryotic cells and viruses,5 showing undetectable levels of activity toward Pol β and Pol γ.6 As a result of this inhibition, aphidicolin displays moderate antitumor and antiviral activity without causing mutagenesis to nontumor or uninfected cells.7 In 1991, the C17 glycinate ester of aphidicolin entered Phase I clinical trials as a treatment for leukemia.8 However, issues of low water solubility and significant rates of metabolic deactivation prevented progress to later stages.7–9 Despite the isolation or preparation of over 300 aphidicolin congeners or derivatives, respectively, no improvement in bioactivity has been observed to date10—except for C6 ketone derivative 4 (Scheme 1) isolated by Yang and co-workers, which is slightly more potent than aphidicolin against certain cancer cell lines.4

For many years, there was little rationale to explain the observed structure activity relationships for the aphidicolin family members and derivatives. However, in a 2014 report, Tahirov and co-workers disclosed a cocrystal structure of aphidicolin bound to Pol α as well as an RNA primer and a DNA template (Scheme 2).11 Crucial hydrogen bonding interactions were observed for the binding of the primary and secondary hydroxy groups at C17/18 and C3 of aphidicolin, respectively, with the protein backbone. The role of the tertiary hydroxy group at C16 was observed to be less important for binding. This emerging binding picture provided a structural basis to rationalize the loss of activity observed in the previously attempted derivatizations10 and guide how future structural changes that improve potency and pharmacokinetic properties could be achieved. For example, the space occupied by the triphosphate group of deoxycytidine triphosphate when bound to Pol α is occupied by the solvent when aphidicolin is bound and is proximal to the tertiary hydroxy group at C16. This suggests that a highly polar, solubilizing group could be used to derivatize the aphidicolin scaffold either at the C16 hydroxy group or one of aphidicolin’s recently isolated congeners bearing a hydroxy group—not required for binding—at a position proximal to this space in the crystal structure.

Scheme 2.

Cocrystal Structure of Aphidicolin Bound to the Active Site of DNA Pol αa

a Reprinted from Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, volume 42, issue (22), 14013–14021, by permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright 2014.

Aphidicolin’s interesting biological activity and unique structure have attracted significant interest from the synthetic community, with 11 groups having achieved its total synthesis.12–22 Scheme 3 summarizes the key steps of the previous total syntheses employed in tackling the major synthetic challenges posed by the aphidicolin scaffold. These challenges include construction of the trans-decalin ring system (Scheme 3A), the two contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenters (Scheme 3B), and the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif (Scheme 3C). General approaches to accessing the trans-decalin scaffold include the use of a Wieland–Miescher ketone analogue (Trost,12 McMurry,13 Bettolo and Lupi17), intramolecular Diels–Alder cycloaddition reactions (Fukumoto,20 Toyota22), and bioinspired polyene cyclizations (Corey,14 Van Tamelen,16 Tanis19). The two contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenters have previously been installed using enolate chemistry (Trost,12 Corey,14 Holton,18 Toyota22), a Heck cyclization reaction (Fukumoto20), and pericyclic reactions (McMurry,13 Ireland,15 Van Tamelen,16 Bettolo and Lupi17). Finally, construction of the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif has been achieved using SN2 processes (Trost,12 Corey,14 Iwata21), bioinspired Wagner–Meerwein rearrangements (Van Tamelen,16 Bettolo and Lupi17), Pd-mediated cyclizations (Fukumoto,20 Toyota22), and a [2 + 2] cycloaddition–fragmentation cascade (Ireland15). Each synthesis is described in greater detail in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 3.

(A) Previous Synthetic Approaches to the trans-Decalin Ring System; (B) Previous Synthetic Approaches to the Two Contiguous All-Carbon Quaternary Stereocenters; (C) Previous Synthetic Approaches to the Bicyclo[3.2.1]octane Motif

Although the previous syntheses of aphidicolin demonstrate many creative and efficient methods for the construction of the carbon framework of this natural product, no synthetic routes to any of aphidicolin’s more oxygenated congeners have been reported to date. Given that a structural basis for aphidicolin’s biological mode of action was only elucidated relatively recently in comparison to these synthetic efforts, we proposed that divergent access to aphidicolin and its congeners would enable the rational design of more potent, water-soluble, and pharmacokinetically viable Pol α inhibitors—guided by the cocrystal structure illustrated in Scheme 2.11 In particular, we sought to identify a common synthetic intermediate amenable to late-stage functionalizations to access aphidicolin’s congeners.

We commenced our studies with known bicycle 29 (Scheme 4) reported by Omura and Nagamitsu23 and previously used in our groups’ synthesis of various xiamycin natural products.24 Bicycle 29 mapped well onto the trans-decalin ring system of the aphidicolin scaffold and can be accessed from (R)-carvone (30), which rendered our prospective synthesis enantiospecific. Our overall strategy was therefore to elaborate bicycle 29 to a common synthetic intermediate possessing suitable functionality to enable the synthesis of many of the oxygenated congeners of the aphidicolin family. From here, we envisaged that we could leverage classical methods for oxygenating the activated positions, alongside established directed and emerging undirected C–H oxidation methodologies, in a late-stage functionalization campaign to access congeners featuring oxidation at any position on the aphidicolin scaffold (Scheme 4; see Scheme 1 for some illustrative congeners).25 Tetracycle 31, bearing an electron-withdrawing group (EWG)—such as an ester or nitrile group—on the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif and an alkene in the decalin backbone, was proposed to serve as a suitable common synthetic intermediate. Notably, unsaturation at C6, C7, C8, and C13 (see 1, Scheme 1, for numbering) is observed in many aphidicolin congeners. In our planned studies, the internal alkene of (R)-carvone (30) would serve as the functional handle to access this unsaturation. Therefore, finding strategies that enabled the carvone enone C=C double bond to be carried through the synthesis would be a key requirement of our approach. We therefore turned our initial focus toward: (1) peripheral manipulation of bicycle 29 to access a trans-decalin intermediate bearing functionality resident in the targeted natural products and suitable for introduction of the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane ring system and (2) the construction of the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane framework, including the installation of the two contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenters. The approaches to accomplish these goals are detailed below.

Scheme 4.

Known Bicycle 29 and Proposed Divergent Late-Stage Functionalization of Common Synthetic Intermediate 31 to Access the Aphidicolin Family

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Inverse-Electron-Demand Diels–Alder Cycloaddition Approach.

Our initial retrosynthesis focused on tetracycle 31 as a suitable common synthetic intermediate to access the aphidicolin family (2, Scheme 5). It was anticipated that the alkene and EWG functional handles in 31 would activate positions 6, 7, 8, 13, and 16 toward various late-stage derivatizations, while directed and undirected methodologies could be leveraged to functionalize distal positions on the scaffold. In the forward sense, the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif would be installed through a 5-exo-trig Giese radical cyclization of an allyl halide with the electron-deficient alkene of spirocyclohexene 32. We envisioned the spiro-fused six-membered ring arising from an inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction26 of an electron-deficient 2-substituted diene (33) with the electron-rich exo-methylene alkene of bicycle 34. Importantly, this cycloaddition would set the second of the two contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenters (purple dots, Scheme 5). Bicycle 34 would arise from known trans-decalin 29 through a Narasaka–Prasad reduction to set the requisite C3 stereochemistry and various functional group interconversions. trans-Decalin 29 has been previously synthesized in four steps from (R)-carvone (30)—a renewable, chiral pool feedstock27—by Omura and Nagamitsu using a TiIII-mediated radical cyclization.23

Scheme 5.

Inverse-Electron-Demand Diels–Alder Cycloaddition Retrosynthesis

Known bicycle 29 was prepared in 25% yield over 4 steps according to Omura and Nagamitsu’s procedure.23 We then turned our attention to achieving a diastereoselective Narasaka–Prasad-type reduction of the C3 carbonyl. Inspired by McMurry’s aphidicolin synthesis,13 we treated bicycle 29 with 2 equiv of l-selectride, followed by H2O2 and saturated aqueous Na2CO3 to afford the desired diol (35) as a single diastereomer (Scheme 6A).28 Presumably, one molecule of l-selectride deprotonates the primary hydroxy group of 29 and acts as an internal Lewis acid to activate the C3 carbonyl group selectively over the enone carbonyl (Scheme 6B). Concomitantly, a second molecule of l-selectride then delivers a hydride through equatorial attack (see 41), avoiding developing 1,3-diaxial interactions, which would arise in the transition state for axial hydride delivery (42). This reduction afforded the corresponding s-Bu boronate ester of diol 35 (not shown), which was cleaved to give diol 35 by the addition of H2O2. Notably, the use of 5 M aqueous NaOH instead of Na2CO3 resulted in attendant Weitz–Scheffer epoxidation of the enone, and classical Narasaka–Prasad reduction conditions using NaBH4 and Et3B resulted in the formation of a 1:1 diastereomeric ratio of the C3 alcohol (35, blue dot) after boronate ester cleavage.

Scheme 6.

(A) Synthesis of Diels–Alder Precursor 40; (B) Transition States for Hydride Delivery from l-Selectride

Following precedent from our group’s previous work on the xiamycin natural products,24 diol 35 was protected as an acetonide, and diastereo- and regioselective 1,2-addition of CH3Li to the carbonyl of enone 37 afforded tertiary alcohol 38 (Scheme 6A). A three-step, one-pot procedure then effected the net oxidation of the primary allylic position. First, SeO2-mediated oxidation afforded a mixture of the desired alcohol (39) and the corresponding aldehyde (not shown). Convergence of these species was achieved by the addition of NaBH4, resulting in another Narasaka–Prasad-type reduction, and H2O2 was required to cleave the resultant boronate ester. Treatment of diol 39 with an excess of methanesulfonyl chloride (MsCl) and Et3N accomplished a tandem substitution of the primary hydroxy group and elimination of the tertiary hydroxy group to afford allylic chloride 40—a precursor for the envisaged Diels–Alder cycloaddition.

We began investigations into our proposed inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction (Scheme 7) with allyl chloride 40 as the electron-rich dienophile and various electron-deficient dienes (see 33). It was our anticipation that this cycloaddition would proceed in a manner that matched the partial charges and expected frontier molecular orbital coefficients of the two components and that the diene would approach selectively from the top-face of the exo-methylene alkene of 40, which we proposed would be less sterically hindered and less inductively deactivated than the internal alkene. First, we studied dienes bearing an ester substituent at the 2-position, such as benzyl ester 45. However, these dienes were found to dimerize rapidly at room temperature, presumably through a thermally accessible bis-pericyclic transition state (see 44), and could not be isolated or trapped in situ with allyl chloride 40.29 2-Cyanobutadiene (46) was prepared using a known procedure.30 However, no reactivity was observed between 46 and the exo-methylene group of 40 upon heating or in the presence of various Lewis acids (e.g., TiCl4, SnCl4, ZnBr2, etc.). Instead, we observed only dimerization of the cyanodiene (46) or decomposition of 40. Methyl coumalate (47) was also investigated as the electron-deficient diene component,31 but no reactivity with 40 was observed under any of the conditions that were tested. Attributing this lack of reactivity at the exo-methylene alkene to the steric encumbrance arising from the adjacent quaternary carbon, we moved to an alternative cycloaddition strategy.

Scheme 7.

Investigation of the Inverse-Electron-Demand Diels–Alder Cycloaddition

Normal Demand Diels–Alder Cycloaddition/Cope Rearrangement Approach.

Targeting the same common synthetic intermediate (31) toward the aphidicolin family, we theorized that the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif could be constructed through an analogous cyclization disconnection using a 1,4-difunctionalization of the diene portion of triene 48 (Scheme 8). Inspired by Ireland’s synthesis of aphidicolin,15 we imagined that the spiro-fused six-membered ring bearing the electron-deficient alkene could be constructed through a [3,3]-sigmatropic Cope rearrangement of the 1,5-diene embedded in tricycle 49. This plan would render the formation of the second contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenter intramolecular—potentially overcoming the steric challenges we faced previously in installing this structural motif. The same electron-deficient diene (33)30 that we investigated in our initial Diels–Alder cycloaddition investigations would now serve as the electron-deficient dienophile in a normal-electron-demand Diels–Alder cycloaddition with the bis-exo-methylene portion of dendralene 50 to introduce all the carbons of the aphidicolin scaffold. The lower steric encumbrance of the bis-exo-methylene motif was expected to make dendralene 50 more reactive toward cycloaddition, and, importantly, it could be accessed in one step from allyl chloride 40 (prepared in nine steps from (R)-carvone, 30).

Scheme 8.

Normal-Electron-Demand Diels–Alder Cycloaddition/Cope Rearrangement Retrosynthesis

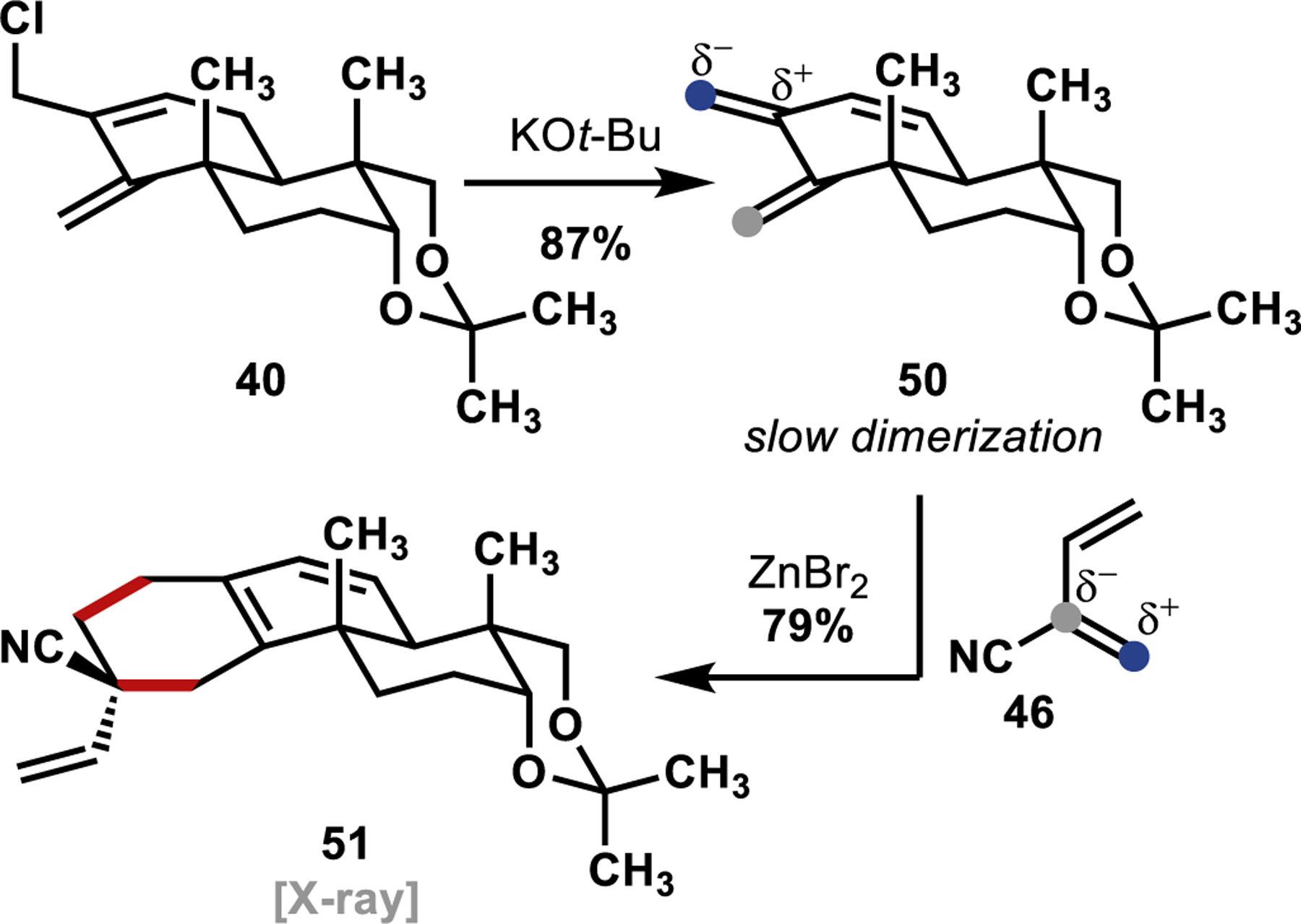

The required bis-exo-methylene dendralene (50) for our normal-electron-demand Diels–Alder cycloaddition was accessed through a KOt-Bu-mediated elimination of HCl from the previously prepared allyl chloride 40 (Scheme 9). Notably, dendralene 50 underwent slow Diels–Alder dimerization at room temperature, reflecting its propensity to participate in cycloaddition reactions. Indeed, upon treatment of dendralene 50 with 2-cyanobutadiene (46), in the presence of ZnBr2 as a Lewis acid catalyst, a facile Diels–Alder cycloaddition was observed. However, instead of forming the desired Diels–Alder adduct (49, Scheme 8), an undesired constitutional isomer (51, Scheme 9) was isolated as the sole product. The structure of this undesired constitutional isomer (51) was confirmed unambiguously through a single-crystal X-ray diffraction study (see Supporting Information for further information).

Scheme 9.

Investigation of the Normal-Electron-Demand Diels–Alder Cycloaddition

We hypothesized that 51 was formed preferentially due to the largest partial negative charge/largest HOMO orbital coefficient residing on the central exo-methylene of dendralene 50 (blue dot, Scheme 9), since placing the largest partial positive charge at the doubly allylic position would be most stabilizing.

To further understand the origin of the Diels–Alder cycloaddition selectivity that results in the formation of the undesired constitutional isomer (A, Scheme 10), we studied this transformation using density functional theory calculations.32 These calculations were performed for both the noncatalyzed and ZnBr2-catalyzed cycloadditions at the B3LYP 6–31G* (with implicit solvation) level of theory. Scheme 10 compares the transition state energies for the formation of each constitutional isomer and diastereomer of the cycloadduct, setting the ground state energies of the noncatalyzed and catalyzed systems both to zero. While the potential energies of nonisomeric states cannot be rigorously compared, the noncatalyzed and catalyzed systems only differ in the presence of an explicitly calculated ZnBr2·Et2O unit complexed to the cyano group in the catalyzed system.

Scheme 10.

Computational Studies into the Normal-Electron-Demand Diels–Alder Cycloaddition

Our calculations are in full agreement with our experimental results. The transition states for the formation of the observed product (A, Scheme 10) are lowest in energy for both the noncatalyzed and catalyzed systems. However, the activation barrier for the catalyzed system is ~7 kcal/mol lower than the noncatalyzed system, and the difference in activation energy for the formation of the observed product (A) and the next lowest energy transition state (for the formation of B) is increased from ~1 kcal/mol in the noncatalyzed system to >5 kcal/mol in the catalyzed system. These calculated values align with the experimentally observed formation of constitutional isomer 51 as the only isolable product under the ZnBr2-catalyzed conditions. Notably, a mixture of products was observed in the absence of this catalyst. One possible explanation for this increase in selectivity in the Lewis acid-catalyzed cycloaddition is that the transition states in this case are significantly more asynchronous (but still concerted) compared to the transition states for the noncatalyzed cycloaddition, potentially increasing the dependence of the cycloaddition selectivity on the polarization of the components.

Cycloisomerization/Divinylcyclopropane-Cope Rearrangement Approach.

Unable to access the desired constitutional isomer for our initial Cope rearrangement approach, we considered other strategies that could similarly set the second of the two contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenters in an intramolecular fashion. We imagined highly functionalized tetracycle 52, which would be accessed using a divinylcyclopropane-Cope rearrangement of bicyclo[3.1.0]-hexane 53 (Scheme 11), could serve as a suitable common synthetic intermediate.33 Cyclopropane 53 would be formed in situ through a catalyst controlled diastereoselective cyclopropanation of dendralene 55 with diazo compound 54.34 The five-membered ring would in turn be constructed using a cycloisomerization of alkyne 56,35 synthesized through various functional group interconversions of diol 39, which we had previously accessed in eight steps from (R)-carvone.

Scheme 11.

Cycloisomerization/Divinylcyclopropane-Cope Rearrangement Retrosynthesis

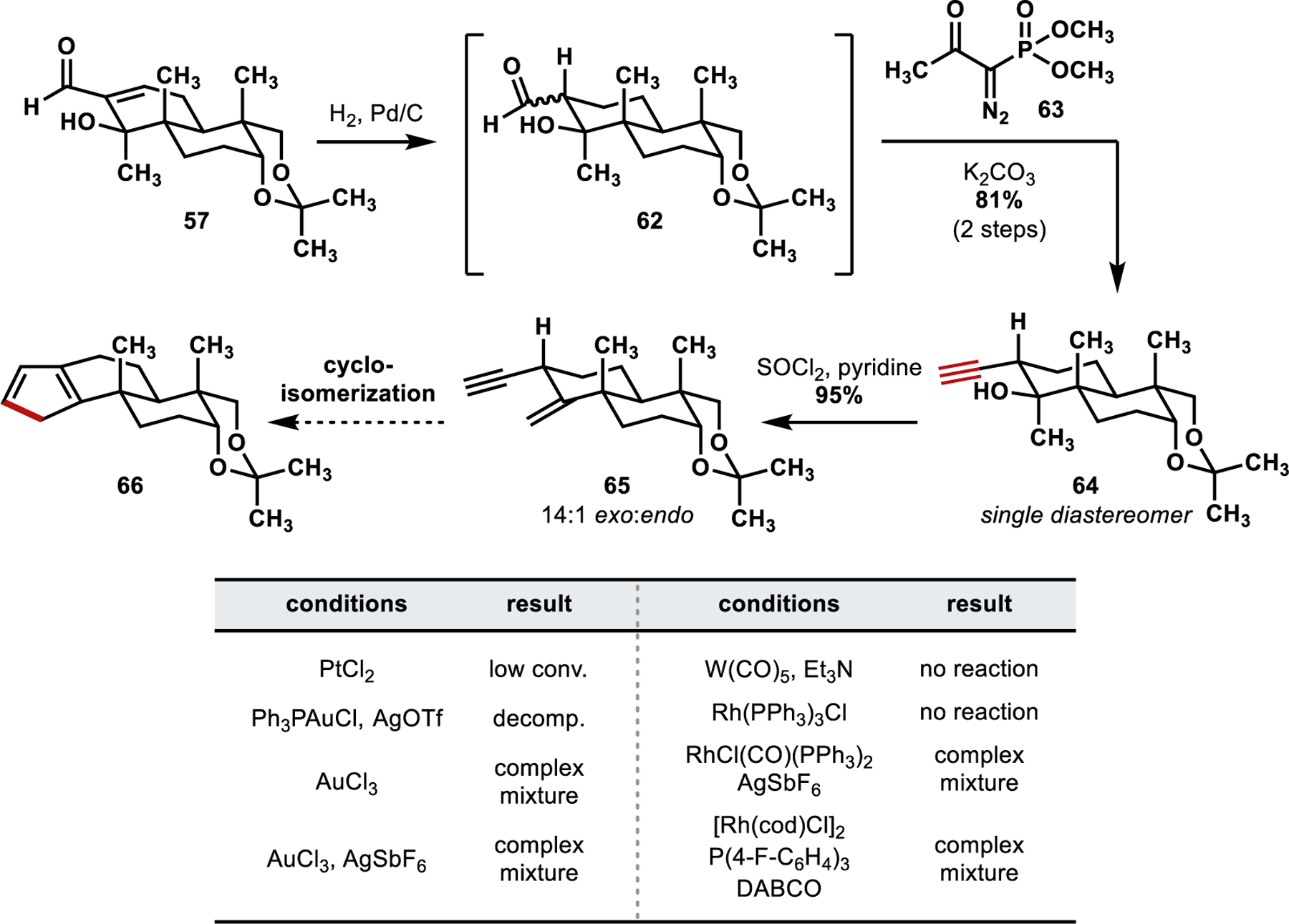

The desired cycloisomerization precursor, dienyne 60 (Scheme 12), was synthesized in three steps from diol 39. Oxidation of the primary allylic hydroxy group to the corresponding aldehyde (57) was followed by a Colvin reaction to install the alkyne (57 → 59),36 and elimination of the tertiary alcohol with MsCl/Et3N afforded the desired dienyne (60). With a suitable precursor in hand, we began investigations into the proposed cycloisomerization reaction.

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of Dienyne 60 and Cycloisomerization Studies

First, we investigated a π-philic Lewis acid activation mode—selected conditions are shown in Scheme 12. Treating dienyne 60 with PtCl2 or Ph3PAuCl/AgBF4 (generating a cationic AuI species in situ) only afforded decomposition (decomp.), whereas no reaction was observed in the presence of AuCl3.35,37 Switching to a metal vinylidene activation mode, the use of various Rh-catalysis conditions, for example, [Rh(C2H4)2Cl]2/P(4-F-C6H4)3/DABCO, similarly resulted in decomposition. In situ generation of W(CO)5 in the presence of Et3N resulted in a monoreduction of the alkyne to the corresponding alkene.38 Likely, the internal alkene of dienyne 60 could be hindering reactivity since the incorporation of additional sp2 hybridized atoms into the forming five-membered ring could introduce additional strain in the cyclization. We therefore sought to study the cyclization without this extraneous functionality.

The alkene of enal 57 was hydrogenated using H2 and catalytic Pd/C to afford a diastereomeric mixture of aldehyde 62, which was subsequently homologated with the Ohira–Bestmann reagent in a stereoconvergent manner to give a single diastereomer of alkyne 64 (Scheme 13).39 This stereochemical outcome likely arises as a result of a Curtin–Hammett scenario where the α-epimers of the aldehyde rapidly interconvert through either deprotonation/reprotonation or retro-aldol/aldol pathways. The somewhat sterically encumbered Ohira–Bestmann reagent may then react more rapidly with the less sterically encumbered epimer, where the aldehyde is equatorially disposed. Treatment of alkyne 64 with SOCl2/pyridine gave the desired skipped enyne (65) through a highly exo-selective elimination of the tertiary hydroxy group. Notably, the use of MsCl or other amine bases gave an increased amount of the endo-elimination product.

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of Skipped Enyne 65 and Cycloisomerization Studies

Analogous to our cycloisomerization studies using dienyne 60, we investigated various conditions for π-activation or vinylidene formation from skipped enyne 65. The absence of the internal alkene led to differences in the reactivity of this system; however, the desired cyclopentadiene product could not be identified or isolated by using any of the attempted reaction conditions. It is possible that the desired cycloisomerization products (cyclopentadienes 61/66) are highly reactive, undergoing isomerization (and ultimately decomposition) through potentially facile 1,5-superfacial hydrogen shifts. With our proposed cycloisomerization proving challenging and concerns about the stability of the desired cyclopentadiene, we reassessed our retrosynthetic analysis more broadly.

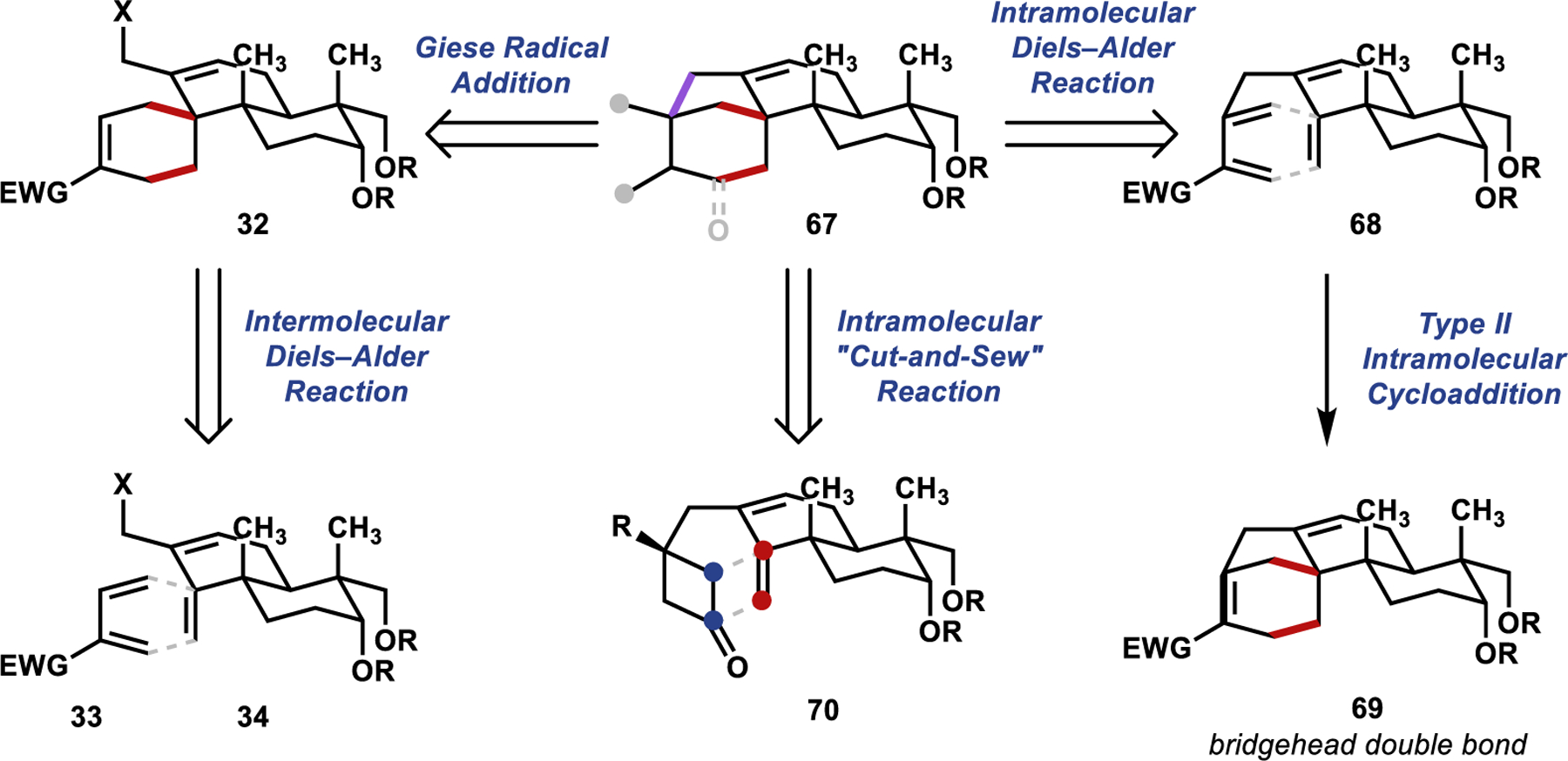

Cyclobutanone “Cut-and-Sew” Approach.

Returning to our original retrosynthetic analysis, we recognized that we had identified a two-bond disconnection (highlighted in red in 67, Scheme 14) and a one-bond disconnection (highlighted in purple) as strategic for construction of the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif. In our initially investigated retrosynthesis (Scheme 14; left), we performed the one-bond disconnection first (67 ⇒ 32), in the form of a Giese radical addition, and the two-bond disconnection second (32 ⇒ 33 + 34), in the form of an inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder cycloaddition. We hypothesized that if, instead, we performed the two-bond disconnection first (67 ⇒ 68, Scheme 14; right), the corresponding Diels–Alder cycloaddition could be more entropically favorable, proceeding in an intramolecular fashion. However, in the forward sense (68 → 69), this corresponds to a type II intramolecular cycloaddition, necessitating the formation of a bridgehead double bond—violating Bredt’s rule. A powerful methodology that has recently emerged for achieving type II intramolecular cycloadditions is the cyclobutanone “cut-and-sew” reaction (Scheme 14; center).40–44 This transformation uses C–C single bond cleavage to perform type II intramolecular cycloaddition reactions without necessarily forming an anti-Bredt alkene. We therefore turned our attention to leveraging this strategy toward the synthesis of the aphidicolin family (70 → 67).

Scheme 14.

Retrosynthetic Analysis for the Construction of the Bicyclo[3.2.1]octane Motif

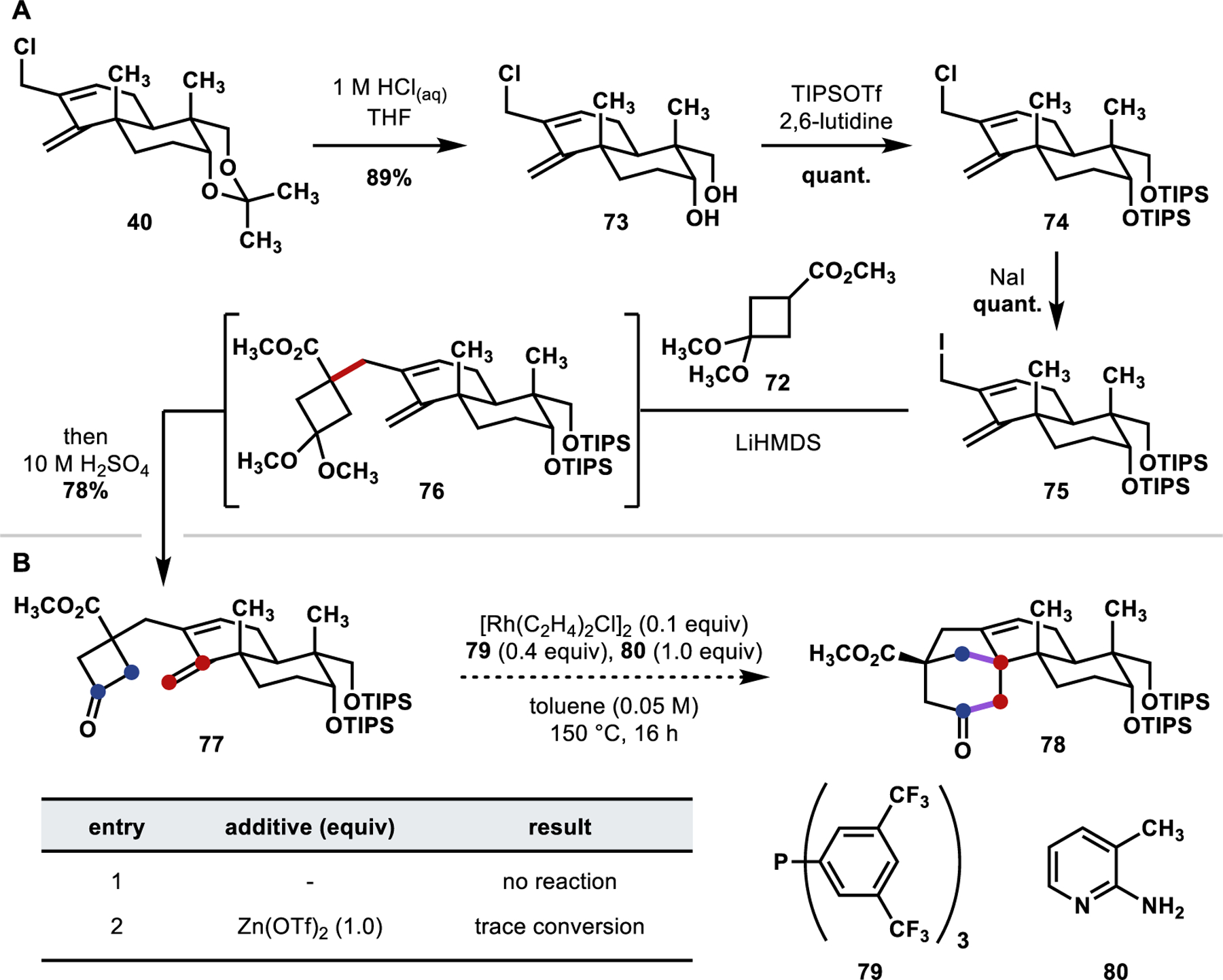

We proposed that tetracycle 71 (Scheme 15), bearing ketone and alkene functional handles, could serve as a suitable common synthetic intermediate for the aphidicolin family. The bicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif would be constructed through an intramolecular “cut-and-sew” cycloaddition between the cyclobutanone and exo-methylene alkene of diene 70. An enolate-type allylation of cyclobutyl pronucleophile 72 with our previously prepared allyl chloride (40) would be used to introduce the tethered cyclobutanone.

Scheme 15.

“Cut-and-Sew” Retrosynthesis

Having identified cyclobutyl pronucleophile 72 (Scheme 15) as suitable for introducing the cyclobutanone group, we realized that an aqueous acidic cleavage of the dimethoxyketal would likely be necessary to unveil the carbonyl group of the cyclobutanone. With this plan in mind, the diol moiety of allylic chloride 40—protected as an acetonide—was deprotected, and diol 73 (Scheme 16A) was reprotected as the bistriisopropylsilyl ether (74). Allyl chloride bearing 74 proved unreactive to attempted allylations of cyclobutyl pronucleophile 72 and was therefore converted to the corresponding allyl iodide (75), which proved to be more reactive. Treatment of 75 with a slight excess of cyclobutyl pronucleophile 72 in the presence of a 2-fold excess of lithium hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS), relative to pronucleophile 72, afforded the desired allylation product in situ (76). Subsequent addition of 10 M aqueous H2SO4 hydrolyzed the dimethoxy ketal to give the desired cyclobutanone (77) in 78% yield over a two-step, one-pot, procedure.

Scheme 16.

(A) Synthesis of Cyclobutanone 77; (B) “Cut-and-Sew” Investigations

With cyclobutanone 77 in hand, we began our studies of the “cut-and-sew” cycloaddition toward the synthesis of tetracycle 78—selected conditions are shown in Scheme 16B. Following precedent from the Dong group (Scheme 16B; entry 1), [Rh(C2H4)2Cl]2 was used as a precatalyst in combination with bis-trifluoromethyl aryl phosphine ligand 79 and 2-amino-3-methyl picoline (80) as a transient directing group.43 However, no reaction was observed under these conditions. In a recent report toward the total synthesis of penicibilaene natural products,44 the Dong group employed updated “cut-and-sew” conditions that proved effective when sterically hindered alkenes were used, finding Zn(OTf)2 to be a key additive. However, on our substrate, only trace conversion to unidentified products was observed using this modification of the conditions (entry 2).

The efficacy of “cut-and-sew” cycloadditions can significantly depend on the rigidity of the linker between the cyclobutanone and alkene groups. This effect can be especially pronounced when using a sterically hindered/less reactive alkene, as demonstrated in the aforementioned total synthesis campaign from the Dong group.44 We hypothesized that the conformational flexibility of the sp3-hybridized carbon in the linking carbons of our system (77) could allow for facile bond rotation in the linker, enforcing additional enthalpic and entropic penalties for adopting the required geometry for migratory insertion, and that initial oxidative addition of the RhI species after the condensation of transient directing group 80 onto the carbonyl of the cyclobutanone is likely reversible. Our inability to achieve the “cut” and “sew” steps in the same reaction forced a move to an alternative strategy where we sought to perform these transformations sequentially.

[2 + 2]-Photocycloaddition/C–C Cleavage Approach.

Targeting an analogous common synthetic intermediate (81, Scheme 17) for late-stage functionalization toward the aphidicolin family, we identified the construction of the two contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenters (highlighted in purple in 81) as a key challenge of the synthesis. To overcome this challenge, we proposed a somewhat counterintuitive, stepwise “sew-and-cut” strategy. The bicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif would be formed through a transannular C–C bond cleavage reaction of tricyclo[4.1.1.03,7]octane 82—the “cut” step—providing a complex testing ground for modern C–C cleavage methodologies.45 While this retrosynthetic reconnection constitutes an increase in structural complexity, we proposed that tricyclo[4.1.1.03,7]octane 82 would be more synthetically accessible than tetracycle 81 through the application of an intramolecular [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition of cyclobutene tethered diene 83—the “sew” step.46 The bond forming steps would exploit the lower steric encumbrance (due to an earlier transition state) and higher reactivity of radical intermediates, compared with closed-shell species, to construct the two contiguous quaternary stereocenters. The [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition precursor would be accessed through a desymmetrizing allylation of a cyclobutyl pronucleophile (84) with allyl iodide 85, which could be prepared in 10 steps from (R)-carvone (30).

Scheme 17.

[2 + 2]-Photocycloaddition/C–C Cleavage Retrosynthesis

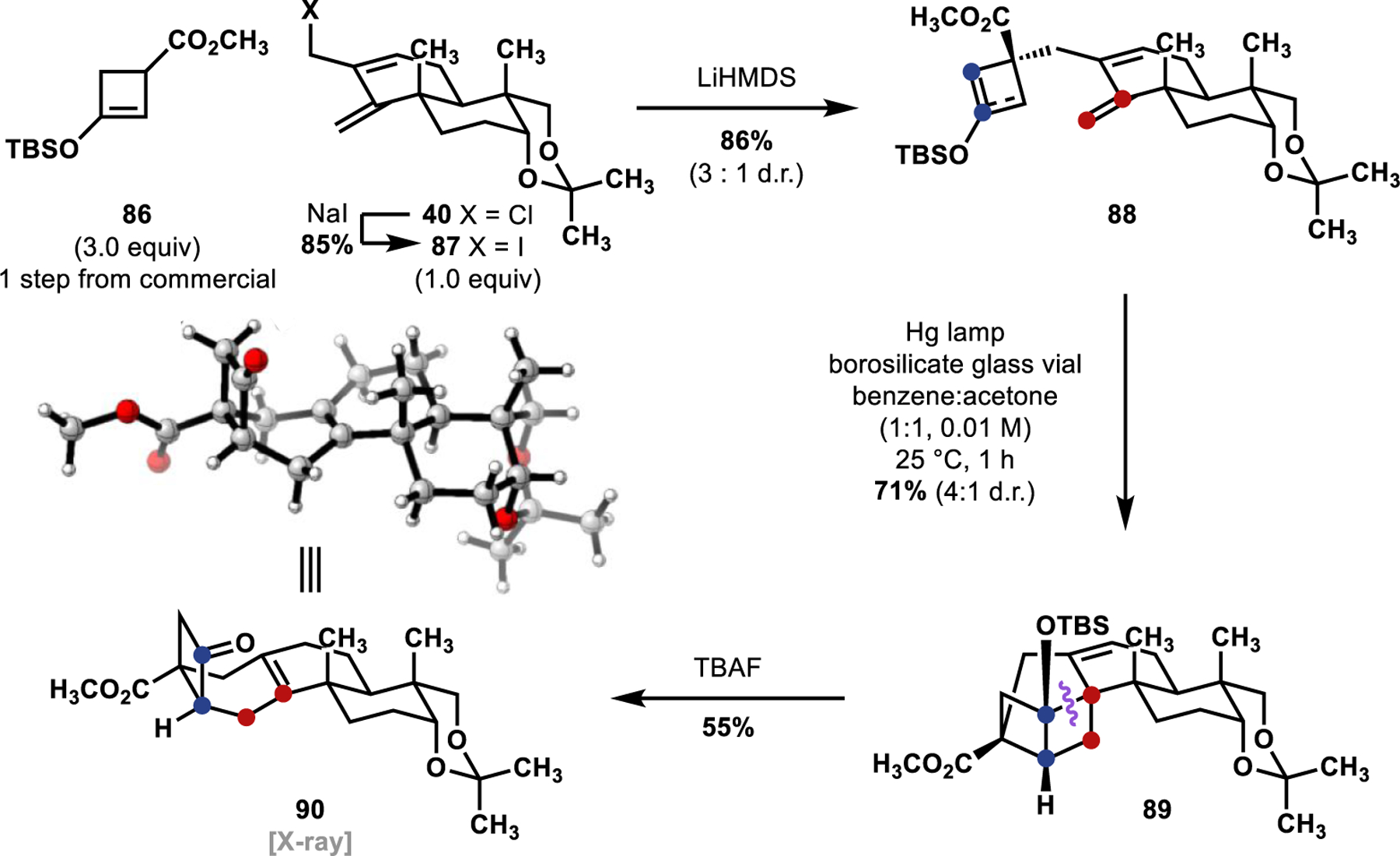

TBS enol ether cyclobutenyl methyl ester pronucleophile 86 (Scheme 18) was prepared in one step from the corresponding commercially available ketone (see Supporting Information for details). Allylation with allyl iodide 87, prepared through a Finkelstein reaction of allyl chloride 40 with NaI, afforded tethered cyclobutenyl enol ether 88 as a 3:1 mixture of diastereomers. At this stage, we could not identify the major double bond isomer or major diastereomer formed in this allylation. Nevertheless, we proceeded to our preliminary investigations of the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition. Subjecting the diastereomeric mixture of [2 + 2]-precursor 88 in a borosilicate glass vial (blocks transmittance of wavelengths below 360 nm) to irradiation from a medium pressure Hg lamp in the presence of cosolvent quantities of acetone as a triplet sensitizer, we were encouraged to observe formation of a [2 + 2]-cycloadduct as a 4:1 mixture of diastereomers (89). Still unable to confirm the major diastereomer of this cycloaddition, the TBS ether was cleaved by treatment with tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF), which to our surprise yielded bicyclo[4.2.0]octane 90 through concomitant C–C bond cleavage (highlighted in purple on structure 89) and alkene transposition. The structure of bicyclo[4.2.0]octane 90 was confirmed unambiguously through a single-crystal X-ray diffraction study (see the Supporting Information for details), which allowed us to retrospectively assign the structures and major diastereomers of [2 + 2]-adduct 89 and tethered cyclobutenyl enol ether 88.

Scheme 18.

Use of Cyclobutenyl Methyl Ester 86 and Preliminary [2 + 2]-Photocycloaddition Investigations

The allylation proceeded with the undesired double bond isomer of tethered cyclobutenyl enol ether 88 as the major diastereomer (blue dots, 88). This indicated that the stereochemical information of allyl iodide 87 influences the allylation selectivity in favor of the undesired isomer, despite being distal from the site of reactivity. The [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition (88 → 89) then proceeded to give crossed [2 + 2]-adduct 89 as the major product, placing the silyl ether group proximal to a somewhat weakened allylic C–C bond of one of the cyclobutene substructures, promoting a strain-assisted C–C bond cleavage, presumably upon unveiling the alkoxide anion, or formation of the “ate” complex from fluoride addition at the Si-atom. While these initial [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition studies were promising in terms of the desired reactivity, we were left with two selectivity challenges: (1) the diastereoselective desymmetrization of the cyclobutenyl pronucleophile with allyl iodide 87 and (2) selective formation of the desired linear [2 + 2]-adduct over the crossed constitutional isomer. We sought to address these challenges stepwise.

First, we addressed the diastereoselective desymmetrization of allylation of a cyclobutenyl pronucleophile. The number of methods for asymmetric/catalyst-controlled alkylations and allylations of enolate esters remain somewhat limited, either relying on the use of chiral amine bases or enantioenriched counterion pairs under phase-transfer conditions.47 Neither of these strategies were amenable to cyclobutenyl methyl ester 86 (Scheme 18), so we synthesized a variety of cyclobutenyl pronucleophiles bearing chiral Evans auxiliaries.48 In our investigation of the allylation of cyclobutenyl methyl ester 86, we previously found that using the acetonide allyl iodide (87) as the electrophile resulted in preferential formation of the undesired double bond isomer of the tethered cyclobutenyl enol ether as a mixture of diastereomers (88). This subsequently allowed us to assign the diastereoselectivity of the allylation reactions for the chiral cyclobutenyl pronucleophiles, as we observed a matched/mismatched effect when using either enantiomer of the pronucleophile.

Reacting (R)-i-Pr Evans’ oxazolidinone derived pronucleophile 91 (Scheme 19; see the Supporting Information for details) with allyl iodide 87 in the presence of lithium hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS) afforded the desired double bond isomer (92) in 86% yield and as a single diastereomer. Application of the previously investigated [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition conditions once again afforded the crossed constitutional isomer (93) as the major product. This product was confirmed unambiguously by cleavage of the TBS ether with tris(dimethylamino)sulfonium difluorotrimethylsilicate (TASF), which proceeded with concomitant cleavage of the proximal allylic C–C bond (highlighted in purple on structure 93) followed by a single-crystal X-ray diffraction study of the resulting bicyclo[4.2.0]octane (94).

Scheme 19.

Preliminary [2 + 2]-Photocycloaddition Investigations with (R)-i-Pr Oxazolidinone Derived Precursor 91

These studies validate our assignment of the double bond isomer formed in the allylation (87 + 91 → 92) and indicate that the linear versus crossed selectivity of the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition does not have a significant dependence on the identity of the double bond isomer used as the starting material. With the first of the challenges outlined above addressed, we turned our attention to controlling the linear versus crossed selectivity of the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition through exploration of the reaction conditions.

Re-examining the conditions for the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition, we found that small amounts of the desired linear constitutional isomer of the [2 + 2]-adduct (95) were formed—as indicated by a 1:3 ratio of the linear [2 + 2]-adduct (95; L) to the crossed [2 + 2]-adduct (93; C) in the 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture of a small-scale reaction using our previously established conditions (Scheme 20). We hypothesized that in the presence of acetone and irradiation with >360 nm light, reaction from the triplet excited state of [2 + 2]-precursor 92 dominated the L/C selectivity. To corroborate this hypothesis, (Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbpy))PF6 was used as a triplet energy transfer photosensitizer under blue LED irradiation (~400 nm) in the absence of acetone (entry 2). This resulted in a 1:3.1 (L/C) ratio of products, supporting our hypothesis that our current conditions lead to reactivity through the triplet excited state of [2 + 2]-precursor 92. Seeking to access the singlet excited state, we switched to quartz glassware—allowing the transmittance of wavelengths <360 nm—and omitted any triplet sensitizer (entry 3). Encouragingly, this higher energy irradiation afforded an increased proportion of the desired L product (1:1.6, L/C); however, the major component was still the crossed product. To investigate the wavelength dependence of the reaction proceeding through the singlet excited state, we repeated our previous experiment in borosilicate glassware (entry 4), observing significantly reduced reactivity. Returning to quartz glassware, we hypothesized that the conformation of the oxazolidinone auxiliary, potentially controlled through varying the solvent polarity, could influence the L/C selectivity. Indeed, the use of polar (protic) solvents such as methanol gave an improved 1:1 ratio of L/C (entry 5). However, upon attempting to reproduce this result on a larger scale, the addition of benzene as a cosolvent was necessary for solubility of [2 + 2]-precursor 92, which led to an undesirable 1:2 product ratio (L/C, entry 6). To address this loss in desired selectivity, we identified iso-propanol as suitably solubilizing while retaining the polar protic hydroxy group, which reinstated the ~1:1 ratio (L/C, entry 7). Finally, we investigated the wavelength dependence in finer detail (entries 8 and 9), finding 254 nm-centered irradiation to be optimal. Upon scaling up the reaction (entry 10), we isolated 35% of the desired linear [2 + 2]-adduct (95) in ~75% purity and 33% of the crossed [2 + 2]-adduct (93). Having established condition-dependent access to either the linear or crossed products of the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition, we sought to understand the origin of this selectivity.

Scheme 20.

Investigation of the Factors Controlling Linear vs Crossed Selectivity of the [2 + 2]-Photocycloadditiona

a Reaction time was 4.5 h instead of 1 h.

While we did not perform extensive mechanistic studies for the previously described [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition, our mechanistic framework for understanding the observed selectivity under different reaction conditions is outlined in Scheme 21. When accessing the singlet excited state of [2 + 2]-precursor 92, the cycloaddition could be conceptualized as proceeding in a mostly concerted manner (Scheme 21A). This could explain why product ratios closer to a statistical 1:1 mixture of constitutional isomers, arising from the top (96) or bottom (97) face approach of the cyclobutene to the exo-methylene alkene, were often observed for conditions presumably proceeding via a singlet excited state.

Scheme 21.

(A) Concerted [2 + 2]-Photocycloaddition Transition States. (B) Stepwise [2 + 2]-Photocycloaddition Mechanism. (C) Solvent Polarity Effects

We hypothesize that in the triplet excited state manifold, the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition proceeds through a stepwise mechanism in which the initial radical cyclization is reversible (Scheme 21B). Selective formation of the crossed [2 + 2]-adduct (93) would arise from biradical 101 through a triplet-to-singlet intersystem crossing (ISC), followed by radical recombination, which we propose occurs more frequently from biradical 101 than from biradical 99. We propose that biradical 101 is more thermodynamically stable and persistent to undergo this unimolecular process. Reactivity in the singlet manifold can also be analyzed in this framework, with the kinetically favored 5-exo-trig radical cyclizations (① and ③) to form biradical 99 being less reversible, due to biradical 99 being rapidly trapped by recombination—occurring without the necessity of ISC.49

As discussed above, solvent polarity likely also influences the selectivity of the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition (Scheme 21C). In nonpolar solvents, the carbonyl groups of the Evans auxiliaries likely adopt a conformation that minimizes the alignment of their dipoles, while in polar solvents, these dipoles are likely more aligned or participate in hydrogen-bonding with polar protic solvents (102). The dipole moment of the reactive alkenes should also change upon excitation, due to the rearrangement of the electrons in the polarized π-bond to a biradical state with more spin density localized on each carbon atom (103).50 These effects could conformationally or electronically influence the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition and be modulated through solvent polarity.

With synthetically useful quantities of linear [2 + 2]-adduct TBS ether 95 in hand, we turned our attention toward the synthesis of aphidicolin. While we sought to access a common synthetic intermediate with suitable functionality to synthesize many of aphidicolin’s more oxygenated congeners, our initial focus was on intercepting formal synthesis intermediate 104, which has been used by many groups as an intermediate toward the synthesis of aphidicolin (Scheme 22A). To our surprise, all conditions attempted to effect cleavage of the TBS ether of the linear [2 + 2]-adduct (95 → 105), including various sources of F−, HO−, and H+, resulted in either no reaction or decomposition (Scheme 22B). We also attempted the oxidation of the TBS ether to the corresponding O-centered radical cation (not shown) to mediate the C–C cleavage directly from TBS ether 95; however, productive reactivity was not observed. Furthermore, preliminary investigation of TBS ether or transannular C–C bond cleavage on substrates lacking the oxazolidinone or alkene functionalities proved similarly unsuccessful. In the face of these challenges, we investigated the identity of the cyclobutenyl fragment further, hoping to identify a substrate that could both further improve the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition selectivity and be easily converted to a suitable substrate for cleavage of the transannular C–C bond. However, we were unable to prepare any other tethered cyclobutenes suitable to further investigate the [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition.51

Scheme 22.

(A) The Aphidicolin Family and Previously Reported Formal Synthesis Intermediate 104; (B) Progress toward Aphidicolin from TBS Ether 95

CONCLUSION

We have made significant progress toward the synthesis of aphidicolin and its more oxygenated congeners using a [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition approach. In doing so, we addressed several key challenges, including (1) diastereoselective pseudo-desymmetrizing allylation of a cyclobutenyl pronucleophile, (2) controlling the linear versus crossed selectivity of our key [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition, developing conditions to access synthetically useful quantities of either constitutional isomer, and (3) construction of a pentacycle containing the embedded aphidicolin scaffold—including the two contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereocenters. These studies provided fundamental insight into these transformations and yielded a promising late-stage intermediate (95) that, after cleavage of the transannular C–C bond, would constitute the tetracyclic aphidicolin scaffold.

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.5c01047.

Background information on aphidicolin’s biosynthesis and previous syntheses, experimental section and computational methods, copies of NMR spectra, structure factor tables, and Cartesian coordinates of computed structures (PDF)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support for this research was provided to R.S. by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (MIRA R35 GM130345). We thank Hasan Celik and Raynald Giovine and the Pines Magnetic Resonance Center (PMRC) at UC Berkeley for assistance with NMR experiments. Instruments in the PMRC are supported in part by NIH S10OD024998. We thank Ulla Andersen and Zongrui Zhou at the UC Berkeley QB3Mass Spectrometry Facility for mass spectrometry analysis. We thank Nicholas Settineri (UC Berkeley) for single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies. We thank Pierre Gilbert (UC Berkeley) for additional studies toward aphidicolin not included in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Accession Codes

Deposition Numbers 2426015–2426017 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.joc.5c01047

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Jack Hayward Cooke, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, United States.

Safaa Jamshed, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, United States.

Richmond Sarpong, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, United States.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Brundret KM; Dalziel W; Hesp B; Jarvis JAJ; Neidle S X-Ray crystallographic determination of the structure of the antibiotic aphidicolin: a tetracyclic diterpenoid containing a new ring system. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1972, 1027–1028. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dalziel W; Hesp B; Stevenson KM; Jarvis JAJ The structure and absolute configuration of the antibiotic aphidicolin: a tetracyclic diterpenoid containing a new ring system. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1973, 2841–2851. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Quin MB; Flynn CM; Schmidt-Dannert C Traversing the fungal terpenome. Nat. Prod. Rep 2014, 31, 1449–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Starratt AN; Loschiavo SR The production of aphidicolin by Nigrospora sphaerica. Can. J. Microbiol 1974, 20, 416–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kawada K; Kimura Y; Katagiri K; Suzuki A; Tamura S Isolation of Aphidicolin as a Root Growth Inhibitor from Harziella entomophilla. Agric. Biol. Chem 1978, 42, 1611–1612. [Google Scholar]; (c) Oikawa H; Ohashi S; Ichihara A; Sakamura S Biosynthesis of diterpenoid aphidicolin: Isolation of intermediates from P-450 inhibitor treated mycelia of Phoma betae. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 7541–7554. [Google Scholar]; (d) Toyomasu T; Niida R; Kenmoku H; Kanno Y; Miura S; Nakano C; Shiono Y; Mitsuhashi W; Toshima H; Oikawa H; Hoshino T; Dairi T; Kato N; Sassa T Identification of Diterpene Biosynthetic Gene Clusters and Functional Analysis of Labdane-Related Diterpene Cyclases in Phomopsis amygdali. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem 2008, 72, 1038–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lin J; Chen X; Cai X; Yu X; Liu X; Cao Y; Che Y Isolation and Characterization of Aphidicolin and Chlamydosporol Derivatives from Tolypocladium inflatum. J. Nat. Prod 2011, 74, 1798–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Niu S; Xia J-M; Li Z; Yang L-H; Yi Z-W; Xie C-L; Peng G; Luo Z-H; Shao Z; Yang X-W Aphidicolin Chemistry of the Deep-Sea-Derived Fungus Botryotinia fuckeliana MCCC 3A00494. J. Nat. Prod 2019, 82, 2307–2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Ikegami S; Taguchi T; Ohashi M; Oguro M; Nagano H; Mano Y Aphidicolin prevents mitotic cell division by interfering with the activity of DNA polymerase-α. Nature 1978, 275, 458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hanaoka F; Kato H; Ikegami S; Ohashi M; Yamada M Aphidicolin does inhibit repair replication in Hela cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1979, 87, 575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Wist E; Prydz H The effect of aphidicolin on DNA synthesis in isolated HeLa cell nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979, 6, 1583–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Krokan H; Schaffer P; DePamphilis ML Involvement of eucaryotic deoxyribonucleic acid polymerases alpha and gamma in the replication of cellular and viral deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochem. 1979, 18, 4431–4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pedrali-Noy G; Spadari S Effect of aphidicolin on viral and human DNA polymerases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1979, 88, 1194–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Huberman JA New views of the biochemistry of eucaryotic DNA replication revealed by aphidicolin, an unusual inhibitor of DNA polymerase alpha. Cell 1981, 23, 647–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Spadari S; Sala F; Pedrali-Noy G Aphidicolin: a specific inhibitor of nuclear DNA replication in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci 1982, 7, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Pedrali-Noy G; Mazza G; Focher F; Spadari S Lack of mutagenicity and metabolic inactivation of aphidicolin by rat liver microsomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1980, 93, 1094–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sessa C; Zucchetti M; Davoli E; Califano R; Cavalli F; Frustaci S; Gumbrell L; Sulkes A; Winograd B; D’incalci M Phase I and Clinical Pharmacological Evaluation of Aphidicolin Glycinate. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 1991, 83, 1160–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Edelson RE; Gorycki PD; MacDonald TL The mechanism of aphidicolin bioinactivation by rat liver in vitro systems. Xenobiotica 1990, 20, 273–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Bucknall RA; Moores H; Simms R; Hesp B Antiviral effects of aphidicolin, a new antibiotic produced by Cephalosporium aphidicola. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 1973, 4, 294–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McMurry JE; Webb TR Synthesis of a tricyclic aphidicolin analog which inhibits DNA synthesis in vitro. J. Med. Chem 1984, 27, 1367–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Prasad G; Edelson RA; Gorycki PD; Macdonald TL Structure-activity relationships for the inhibition of DNA polymerase α by aphidicolln derivatives. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 6339–6348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Selwood DL; Challand SR; Champness JN; Gillam J; Hibberd DK; Jandu KS; Lowe D; Pether M; Selway J; Trantor GE Isosteres of the DNA polymerase inhibitor aphidicolin as potential antiviral agents against human herpes viruses. J. Med. Chem 1993, 36, 3503–3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Michaelis M; Vogel JU; Cinatl J; Langer K; Kreuter J; Schwabe D; Driever PH; Cinatl J Cytotoxicity of aphidicolin and its derivatives against neuroblastoma cells in vitro: synergism with doxorubicin and vincristine. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2000, 11, 479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Baranovskiy AG; Babayeva ND; Suwa Y; Gu J; Pavlov YI; Tahirov TH Structural basis for inhibition of DNA replication by aphidicolin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 14013–14021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Trost BM; Nishimura Y; Yamamoto K A total synthesis of aphidicolin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 1328–1330. [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) McMurry JE; Andrus A; Ksander GM; Musser JH; Johnson MA Stereospecific total synthesis of aphidicolin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 1330–1332. [Google Scholar]; (b) McMurry JE; Andrus A; Ksander GM; Musser JH; Johnson MA Total synthesis of aphidicolin. Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Corey EJ; Tius MA; Das J Total synthesis of (. +-.)-aphidicolin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 1742–1744. [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Ireland RE; Godfrey JD; Thaisrivongs S Efficient, stereoselective total synthesis of (.+-.)-aphidicolin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1981, 103, 2446–2448. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ireland RE; Dow WC; Godfrey JD; Thaisrivongs S Total synthesis of (.+-.)-aphidicolin and (. +-.)-.beta.-chamigrene. J. Org. Chem 1984, 49, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar]

- (16).van Tamelen EE; Zawacky SR; Russell RK; Carlson JG Biogenetic-type total synthesis of (.+-.)-aphidicolin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1983, 105, 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bettolo RM; Tagliatesta P; Lupi A; Bravetti D A Total Synthesis of Aphidicolin: Stereospecific Synthesis of (±)-3α, 18-Dihydoxy-17-Noraphidicolan-16-one. Helv. Chim. Acta 1983, 66, 1922–1928. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Holton RA; Kennedy RM; Kim HB; Krafft ME Enantioselective total synthesis of aphidicolin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 1597–1600. [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Tanis SP; Chuang YH; Head DB A formal total synthesis of (±)-aphidicolin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 6147–6150. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanis SP; Chuang YH; Head DB Furans in synthesis. 8. Formal total syntheses of (.+-.)- and (+)-aphidicolin. J. Org. Chem 1988, 53, 4929–4938. [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Toyota M; Nishikawa Y; Fukumoto K An expeditious and efficient formal synthesis of (±)-aphidicolin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 6495–6498. [Google Scholar]; (b) Toyota M; Nishikawa Y; Seishi T; Fukumoto K Aphidicolin synthesis (I)—formal synthesis of (±)-aphidicolin by the successive intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 10183–10192. [Google Scholar]; (c) Toyota M; Nishikawa Y; Fukumoto K Aphidicolin synthesis (II)—an expeditious and efficient formal synthesis of (±)-aphidicolin. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 11153–11166. [Google Scholar]; (d) Toyota M; Nishikawa Y; Fukumoto K Enantioselective total synthetic route to (+)-aphidicolin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 5379–5382. [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Tanaka T; Okuda O; Murakami K; Yoshino H; Mikamiyama H; Kanda A; Iwata C; Kim SW Synthetic Studies on Aphidicolane and Stemodane Diterpenes. V. A Facile Formal Total Synthesis of (±)-Aphidicolin via a Lewis Acid-Mediated Stereoselective Spiroannelation. Chem. Pharm. Bull 1995, 43, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar]; (b) Iwata C; Morie T; Tanaka T Synthetic Studies on Aphidicolane and Stemodane Diterpenes. I. Synthesis of (2′R*, 4a′S*, 8a′R*)-2′, 8a′-Dimethyl-4a′, 5′, 8′, 8a′-tetrahydrospiro [2, 5-cyclohexadiene-1, 1′(2H)-naphthalene]-3′(4′H), 4, 6′ (7′H)-trione. Chem. Pharm. Bull 1985, 33, 944–949. [Google Scholar]; (c) Iwata C; Murakami K; Okuda O; Morie T; Maezaki N; Yamashita H; Kuroda T; Imanishi T; Tanaka T Synthetic Studies on Aphidicolane and Stemodane Diterpenes. II. Neighboring Hydroxyl Group Participation in Stereoselective Syntheses of Tricyclo[6.3.1.01, 6]dodecanes Corresponding to the B/C/D-Ring Systems. Chem. Pharm. Bull 1993, 41, 1900–1905. [Google Scholar]; (d) Tanaka T; Murakami K; Okuda O; Kuroda T; Inoue T; Kamei K; Murata T; Yoshino H; Imanishi T; Iwata C Synthetic Studies on Aphidicolane and Stemodane Diterpenes. III.An Alternative Stereoselective Access to Aphidicolane-Type B/C/D-Ring System. Chem. Pharm. Bull 1994, 42, 1756–1759. [Google Scholar]; (e) Tanaka T; Murakami K; Okuda O; Inoue T; Kuroda T; Kamei K; Murata T; Yoshino H; Imanishi T; Kim S-W; Iwata C Synthetic Studies on Aphidicolane and Stemodane Diterpenes. IV.A Stereoselective Formal Total Synthesis of (±)-Aphidicolin. Chem. Pharm. Bull 1995, 43, 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Toyota M; Sasaki M; Ihara M Diastereoselective Formal Total Synthesis of the DNA Polymerase α Inhibitor, Aphidicolin, Using Palladium-Catalyzed Cycloalkenylation and Intramolecular Diels–Alder Reactions. Org. Lett 2003, 5, 1193–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Odani A; Ishihara K; Ohtawa M; Tomoda H; Omura S; Nagamitsu T Total synthesis of pyripyropene A. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 8195–8203. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Pfaffenbach M; Bakanas I; O’Connor NR; Herrick JK; Sarpong R Total Syntheses of Xiamycins A, C, F, H and Oridamycin A and Preliminary Evaluation of their Anti-Fungal Properties. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 15304–15308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) Gutekunst WR; Baran PS C–H functionalization logic in total synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 1976–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen DY-K; Youn SW C–H Activation: A Complementary Tool in the Total Synthesis of Complex Natural Products. Chem.—Eur. J 2012, 18, 9452–9474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Abrams DJ; Provencher PA; Sorensen EJ Recent applications of C–H functionalization in complex natural product synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 8925–8967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Santana VCS; Fernandes MCV; Cappuccelli I; Richieri ACG; de Lucca EC Jr Metal-Catalyzed C–H Bond Oxidation in the Total Synthesis of Natural and Unnatural Products. Synthesis 2022, 54, 5337–5359. [Google Scholar]

- (26).(a) Brocksom TJ; Nakamura J; Ferreira ML; Brocksom U The Diels-Alder Reaction: an Update. J. Braz. Chem. Soc 2001, 12, 597–622. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gallier F Metal Promoted Diels-Alder Reactions. Curr. Org. Chem 2016, 20, 2222–2253. [Google Scholar]

- (27).(a) Brill ZG; Condakes ML; Ting CP; Maimone TJ Navigating the Chiral Pool in the Total Synthesis of Complex Terpene Natural Products. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 11753–11795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Masarwa A; Weber M; Sarpong R Selective C–CC–H Bond and Activation/Cleavage of Pinene Derivatives: Synthesis of Enantiopure Cyclohexenone Scaffolds and Mechanistic Insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6327–6334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lusi RF; Perea MA; Sarpong R C–C Bond Cleavage of α-Pinene Derivatives Prepared from Carvone as a General Strategy for Complex Molecule Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res 2022, 55, 746–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).For an example of a H2O2-mediated boronate ester cleavage using Na2CO3 as the base, see:; Kusama H; Hara R; Kawahara S; Nishimori T; Kashima H; Nakamura N; Morihira K; Kuwajima I Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (–)-Taxol. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 3811–3820. [Google Scholar]

- (29).(a) Hoffmann HMR; Rabe J Preparation of 2-(1-Hydroxyalkyl)acrylic Esters; Simple Three-Step Synthesis of Mikanecic Acid. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1983, 22, 795–796. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang T; Hoye TR Diels–Alderase-free, bis-pericyclic, [4 + 2] dimerization in the biosynthesis of (±)-paracaseolide A. Nat. Chem 2015, 7, 641–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kougias SM; Knezz SN; Owen AN; Sanchez RA; Hyland GE; Lee DJ; Patel AR; Esselman BJ; Woods RC; McMahon RJ Synthesis and Characterization of Cyanobutadiene Isomers-Molecules of Astrochemical Significance. J. Org. Chem 2020, 85, 5787–5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Dobler D; Leitner M; Moor N; Reiser O 2-Pyrone – A Privileged Heterocycle and Widespread Motif in Nature. Eur. J. Org Chem 2021, 2021 (46), 6180–6205. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; Li X; Caricato M; Marenich AV; Bloino J; Janesko BG; Gomperts R; Mennucci B; Hratchian HP; Ortiz JV; Izmaylov AF; Sonnenberg JL; Williams-Young D; Ding F; Lipparini F; Egidi F; Goings J; Peng B; Petrone A; Henderson T; Ranasinghe D; Zakrzewski VG; Gao J; Rega N; Zheng G; Liang W; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Throssell K; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark MJ; Heyd JJ; Brothers EN; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Keith TA; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell AP; Burant JC; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Millam JM; Klene M; Adamo C; Cammi R; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Farkas O; Foresman JB; Fox DJ Gaussian 16. Rev. C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Krüger S; Gaich T Recent applications of the divinylcyclopropane–cycloheptadiene rearrangement in organic synthesis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2014, 10, 163–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).(a) Bartoli G; Bencivenni G; Dalpozzo R Asymmetric Cyclopropanation Reactions. Synthesis 2014, 46, 979–1029. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML; Hedley SJ Intermolecular reactions of electron-rich heterocycles with copper and rhodium carbenoids. Chem. Soc. Rev 2007, 36, 1109–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).(a) Belmont P; Parker E Silver and Gold Catalysis for Cycloisomerization Reactions. Eur. J. Org Chem 2009, 2009 (35), 6075–6089. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiménez-Núñez E; Echavarren AM Gold-Catalyzed Cycloisomerizations of Enynes: A Mechanistic Perspective. Chem. Rev 2008, 108, 3326–3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chintawar CC; Yadav AK; Kumar A; Sancheti SP; Patil NP Divergent Gold Catalysis: Unlocking Molecular Diversity through Catalyst Control. Chem. Rev 2021, 121, 8478–8558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).(a) Colvin EW; Hamill BJ One-step conversion of carbonyl compounds into acetylenes. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1973, 151–152. [Google Scholar]; (b) Colvin EW; Hamill BJ A simple procedure for the elaboration of carbonyl compounds into homologous alkynes. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1977, 869–874. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Yao T; Zhang X; Larock RC AuCl3-Catalyzed Synthesis of Highly Substituted Furans from 2-(1-Alkynyl)-2-alken-1-ones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 11164–11165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).(a) Kim H; Lee C Rhodium-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of N-Propargyl Enamine Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 6336–6337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fisher EL; Wilkerson-Hill SM; Sarpong R Tungsten-Catalyzed Heterocycloisomerization Approach to 4,5-Dihydro-benzo[b]furans and -indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 9946–9949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).(a) Müller S; Liepold B; Roth GJ; Bestmann HJ An Improved One-pot Procedure for the Synthesis of Alkynes from Aldehydes. Synlett 1996, 1996 (6), 521–522. [Google Scholar]; (b) Roth GJ; Liepold B; Müller SG; Bestmann HJ Further Improvements of the Synthesis of Alkynes from Aldehydes. Synthesis 2004, 2004 (1), 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- (40).(a) Murakami M; Itahashi T; Ito Y Catalyzed intramolecular olefin insertion into a carbon-carbon single bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 13976–13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xue Y; Dong G Deconstructive Synthesis of Bridged and Fused Rings via Transition-Metal-Catalyzed “Cut-and-Sew” Reactions of Benzocyclobutenones and Cyclobutanones. Acc. Chem. Res 2022, 55, 2341–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).For the original example of using a 2-amino picoline transient directing group in Rh-catalysed C–C bond cleavage, see:; Jun C-H; Lee H Catalytic Carbon–Carbon Bond Activation of Unstrained Ketone by Soluble Transition-Metal Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 880–881. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Souillart L; Parker E; Cramer N Highly enantioselective rhodium(I)-catalyzed activation of enantiotopic cyclobutanone C-C bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 3001–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ko H; Dong G Cooperative activation of cyclobutanones and olefins leads to bridged ring systems by a catalytic [4 + 2] coupling. Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 739–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Xue Y; Dong G Total Synthesis of Penicibilaenes via C–C Activation-Enabled Skeleton Deconstruction and Desaturation Relay-Mediated C–H Functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 8272–8277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).(a) Ota E; Wang H; Frye NL; Knowles RR A Redox Strategy for Light-Driven, Out-of-Equilibrium Isomerizations and Application to Catalytic C–C Bond Cleavage Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 1457–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Landwehr EM; Baker MA; Oguma T; Burdge HE; Kawajiri T; Shenvi R Concise syntheses of GB22, GB13, and himgaline by cross-coupling and complete reduction. Science 2022, 375, 1270–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang B; Perea MA; Sarpong R Transition Metal-Mediated C-C Single Bond Cleavage: Making the Cut in Total Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59 (43), 18898–18919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).(a) Poplata S; Tröster A; Zou Y-Q; Bach T Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Cyclobutanes by Olefin [2 + 2] Photocycloaddition Reactions. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 9748–9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li J; Gao K; Bian M; Ding H Recent advances in the total synthesis of cyclobutane-containing natural products. Org. Chem. Front 2020, 7, 136–154. [Google Scholar]

- (47).(a) Koga K; Odashima K Asymmetric synthesis using chiral bases. Yakugaku Zasshi 1997, 117, 800–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wright TB; Evans PA Catalytic Enantioselective Alkylation of Prochiral Enolates. Chem. Rev 2021, 121, 9196–9242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Chen L-Y; Huang P-Q Evans’ Chiral Auxiliary-Based Asymmetric Synthetic Methodology and Its Modern Extensions. Eur. J. Org Chem 2024, 27 (4), No. e202301131. [Google Scholar]

- (49).For an analogous thermal scenario on a similar scaffold see:; Kim DE; Zhu Y; Harada S; Aguilar I; Cuomo AE; Wang M; Newhouse TR Total Synthesis of (+)-Shearilicine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 4394–4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Anslyn EV, Dougherty DA Modern Physical Organic Chemistry, 1st ed.; University Science Books: Sausalito, 2006. p 944. [Google Scholar]

- (51).The work described in this manuscript and further details are reported in Hayward Cooke, J. Synthetic Studies Toward the Aphidicolin Family and Total Synthesis of Pupukeanane Natural Products Using a “Contra-biosynthetic” Strategy. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 2024. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3zr510zq.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.