Abstract

Proteus mirabilis is a common uropathogen in patients with long-term catheterization or with structural or functional abnormalities in the urinary tract. The mannose-resistant, Proteus-like (MR/P) fimbriae and flagellum are among virulence factors of P.mirabilis that contribute to its colonization in a murine model of ascending urinary tract infection. mrpJ, the last of nine genes of the mrp operon, encodes a 107 amino acid protein that contains a putative helix–turn–helix domain. Using transcriptional lacZ fusions integrated into the chromosome and mutagenesis studies, we demonstrate that MrpJ represses transcription of the flagellar regulon and thus reduces flagella synthesis when MR/P fimbriae are produced. The repression of flagella synthesis by MrpJ is confirmed by electron microscopy. However, a gel mobility shift assay indicates that MrpJ does not bind directly to the regulatory region of the flhDC operon. The isogenic mrpJ null mutant of wild-type P.mirabilis strain HI4320 is attenuated in the murine model. Our data also indicate that PapX encoded by a pap (pyelonephritis- associated pilus) operon of uropathogenic Escherichia coli is a functional homolog of MrpJ.

Keywords: adherence/coordination/fimbriae/flagella/motility

Introduction

Adhesion and motility represent two dynamic and integral aspects of microbial pathogenesis (Finlay and Falkow, 1997). Bacterial surface structures, fimbriae and flagella, mediate these functions. While flagella are mostly recognized for their fundamental involvement in motility and fimbriae for their adhesiveness (Hultgren et al., 1996; Macnab, 1996), there are also examples of fimbriae-mediated (twitching) motility (Wall and Kaiser, 1999) and flagella-mediated adhesion (Allen-Vercoe and Woodward, 1999). Reciprocal regulation between flagella synthesis and fimbriae production allows bacteria to coordinate these two counterproductive properties, motility and adherence. Regulation could occur at the level of a two-component signal transduction system, as is the case for Bordetella pertussis, in which the two-component BvgAS system activates transcription of adhesin genes and represses flagellar regulon (Akerley et al., 1995). Regulation may also occur through feedback from downstream events as reported in Vibrio cholerae, where mutations altering motility directly feed back to the ToxR regulatory system to alter the expression of the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) (Gardel and Mekalanos, 1996). We report here for the first time that a regulatory protein encoded by a fimbrial gene cluster directly represses flagella synthesis.

Proteus mirabilis, a dimorphic Gram-negative bacterium, commonly causes urinary tract infection in individuals with long-term catheterization or with structural or functional abnormalities in the urinary tract (Warren et al., 1982). The hallmark of urinary tract infection with P.mirabilis is the development of bladder and kidney stones due to urease production (Mobley, 2000). Flagellum and the mannose-resistant, Proteus-like (MR/P) fimbriae have been identified as virulence factors of P.mirabilis that contribute to its colonization of the urinary tract in a murine model (Mobley et al., 1996; Li et al., 1999). Flagella synthesis in P.mirabilis is also an integral part of swarmer cell differentiation during which single vegetative cells with polar flagella develop into multicellular swarm cells expressing thousands of peritrichous flagella, allowing the organism to move rapidly across surfaces in a coordinated manner known as ‘swarming’ (Henrichsen, 1972; Fraser and Hughes, 1999). The MR/P fimbriae belongs to a family of bacterial fimbriae modeled after the P fimbria of Escherichia coli, which is assembled through the chaperone–usher pathway (Soto and Hultgren, 1999). The mrp gene cluster (Figure 2A) contains two divergent transcripts, mrpABCDEFGHJ (designated as the mrp operon) and mrpI (Bahrani and Mobley, 1994; Li et al., 1999). The promoter for the mrp operon resides in a 251-bp invertible element flanked by a pair of 21-bp inverted repeats (Zhao et al., 1997). mrpI encodes a recombinase that switches the invertible element either from ON (an orientation that allows the transcription of the mrp operon) to OFF (an orientation that prevents the transcription of the mrp operon) or from OFF to ON (Zhao et al., 1997). Gene products of the mrp operon (all except MrpJ) have an apparent functional homolog in P fimbria (Bahrani and Mobley, 1994; Li et al., 1999). A BLAST search revealed that MrpJ, a 107-amino acid residue protein, contains a putative helix–turn–helix motif and shares homology with putative transcriptional regulators that belong to the Cro/CI family. In this study, we investigate the function of MrpJ.

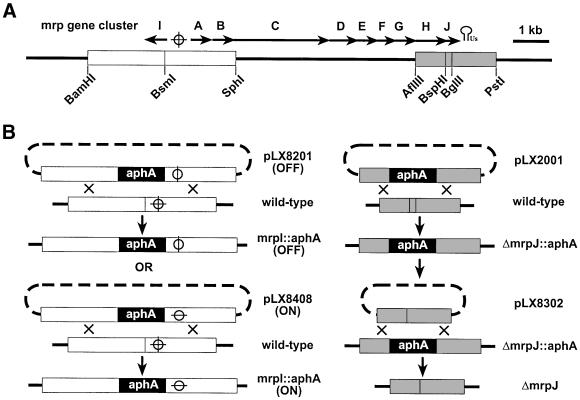

Fig. 2. Construction of isogenic mutants of P.mirabilis HI4320. (A) Schematic drawing of the mrp gene cluster. The 10 open reading frames of the mrp gene cluster, mrpA–J, are represented by 10 arrows labeled as A–J, respectively. The circle and cross symbol represents the invertible element that contains the promoter for the mrp operon. The stem–loop symbol followed by ‘Us’ represents the putative ρ-independent terminator of the mrp operon. The two fragments used to construct mutation in mrpI (white box) and mrpJ (gray box) and related restriction sites are illustrated. (B) Construction of isogenic mutants from P.mirabilis HI4320. The black box represents the 1.3-kb kanamycin-resistance cassette encoded by aphA. Shown on the left side is the process for construction of the phase-locked mrpI null mutation (mrpI::aphA, ON or OFF). On the right side is the process for construction of the mrpJ null mutations (ΔmrpJ::aphA and ΔmrpJ). The circle intersected by a horizontal line represents the invertible element locked in the ON orientation, while the circle intersected by a vertical line represents the invertible element locked in the OFF orientation. See Materials and methods for details of all strain constructions.

Results

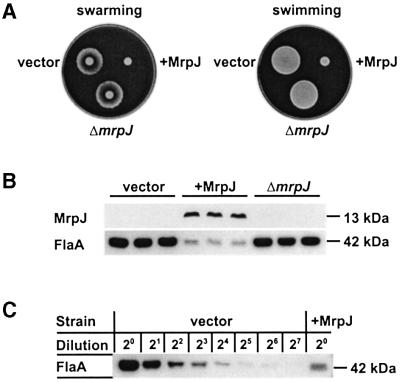

Elevated expression of MrpJ in P.mirabilis inhibits motility by reducing flagella production

The first indication of a potential function of MrpJ came from the observation that P.mirabilis HI4320 transformed with pLX3805 (+MrpJ) displayed impaired motility in swimming as well as swarming when compared with P.mirabilis HI4320 transformed with pLX3607 (vector) or pLX5401 (ΔmrpJ), which carried a deletion of the 5′ end of the mrpJ (Figure 1A; see Materials and methods for plasmid construction). This impairment was attributed to the elevated expression of MrpJ as indicated by the western blot developed with antiserum against MrpJ (Figure 1B). To test whether this impairment in motility resulted from changes in flagella production, western blots were performed with antiserum against P.mirabilis flagella (Mobley et al., 1996). Proteus mirabilis transformed with pLX3805 (+MrpJ) exhibited an 8-fold reduction in flagella synthesis when compared with the controls (Figure 1B and C). These results indicate that elevated expression of MrpJ represses flagella production and impairs motility. This impaired motility describes a phenotype of the population rather than each individual bacterium. When P.mirabilis HI4320 transformed with pLX3805 (+MrpJ) was examined by phase contrast microscopy, the motile bacteria in the population appeared to swim normally.

Fig. 1. Elevated expression of MrpJ in P.mirabilis inhibits motility due to reduced flagella production. The three strains assayed here are P.mirabilis HI4320 transformed with pLX3607 (vector), pLX3805 (+MrpJ) and pLX5401 (ΔmrpJ). (A) The three strains were assayed for swarming on 1.5% Luria agar and for swimming in 0.35% Luria agar. (B) Three overnight Luria broth cultures of each of the three strains were adjusted to the same optical density, and equal volumes processed for SDS–PAGE and subsequent western blot analyses with antiserum against MrpJ or P.mirabilis flagella (FlaA). A Coomassie Blue-stained gel confirmed that equivalent amounts of protein were loaded to each lane (data not shown). (C) Two-fold serial dilutions of protein samples were assayed by western blot analysis to assess the difference in flagella production between the two strains.

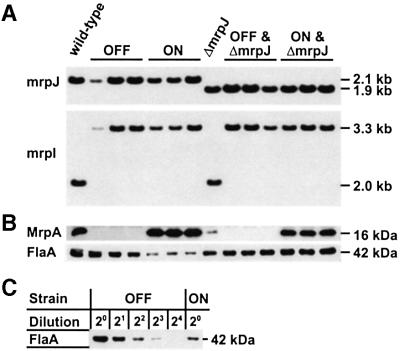

Mutagenesis studies on mrpJ in P.mirabilis demonstrate that MrpJ represses flagella production when MR/P fimbriae are expressed

To determine the significance of the physiological level of MrpJ, two different isogenic mrpJ null mutants were constructed from P.mirabilis strain HI4320. One, designated as ΔmrpJ::aphA, has a 180-bp deletion of the 5′ end of mrpJ and a 1.3-kb insertion of the kanamycin-resistance cassette at the same position. The other, designated as ΔmrpJ, has only the 180-bp deletion (see Materials and methods and Figure 2 for details of strain construction). To avoid complications from the phase-variable transcription of the mrp operon, we constructed phase-locked mutants from either the wild-type HI4320 or its isogenic mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ) by inserting a 1.3-kb kanamycin-resistance cassette into mrpI, the gene encoding the recombinase that mediates the switch of the invertible element. There are two types of phase-locked mutants: one type was designated ON (as their invertible elements are locked in the ON orientation) and the other type was designated as OFF (as their invertible elements are locked in the OFF orientation) (Figure 2). Mutations in mrpJ (ΔmrpJ) and mrpI (mrpI::aphA) were confirmed with Southern blot analysis (Figure 3A). The phase of the invertible element in the ON and the OFF mutants was verified with a previously developed PCR-based assay (Zhao et al., 1997; data not shown). The production of MR/P fimbriae was analyzed by western blot developed with antiserum against MrpA, the major MR/P pilin (Li et al., 1999). Consistent with the phase of their invertible elements, the ON mutants expressed MR/P fimbriae whereas the OFF mutants did not (Figure 3B). The effect of MrpJ on flagella production was examined in the ON and the OFF mutants. In the presence of the wild-type mrpJ, the ON mutants produced significantly less (∼4-fold) flagella than did the OFF mutants (Figure 3B and C). This repression of flagella production was attributed to MrpJ and not to the expression of MR/P fimbriae because there was no significant difference in flagella production between the ON&ΔmrpJ mutants and the OFF&ΔmrpJ mutants (Figure 3B). These data conclusively demonstrate that one intrinsic function of MrpJ is to repress flagella production when MR/P fimbriae are expressed.

Fig. 3. Verification and characterization of the phase-locked mutants of the wild-type HI4320 and the mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ). (A) Southern blot analyses were performed to verify the genotype of all strains. An mrpJ-specific probe confirmed the deletion of a 180-bp fragment (ΔmrpJ) in the ΔmrpJ mutant, the three OFF&ΔmrpJ mutants and the three ON&ΔmrpJ mutants. An mrpI-specific probe verified the 1.3-kb insertions in mrpI (mrpI::aphA) in all the phase-locked mutants. (B) Western blot analyses were performed. Overnight cultures were adjusted to the same optical density, and equal volumes were processed for SDS–PAGE and subsequent western blot analyses with antisera against MrpA or flagella (FlaA). (C) Western blot analysis with antiserum against flagella (FlaA) was performed to assess the difference in flagella synthesis between the OFF mutant and the ON mutant.

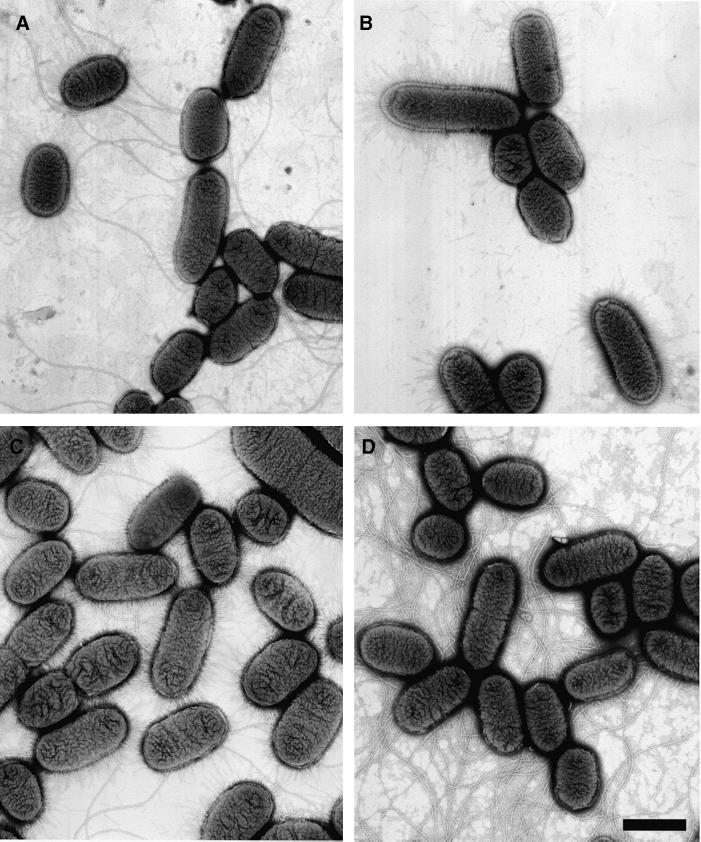

Electron micrographs of P.mirabilis strains expressing different levels of MrpJ demonstrate that MrpJ represses flagella production

Four P.mirabilis strains expressing different levels of MrpJ were examined by electron microscopy (Figure 4). Consistent with western blot analyses, HI4320 transformed with pLX3805 (+MrpJ) produced less flagella than did HI4320 transformed with pLX3607 (vector), and the isogenic ON&ΔmrpJ mutant of HI4320 produced more flagella than did the isogenic ON mutant of HI4320. These data further support the conclusion that MrpJ represses flagella production.

Fig. 4. Electron micrographs of P.mirabilis strains expressing different levels of MrpJ. Electron micrographs of the wild-type P.mirabilis strain HI4320 transformed with pLX3607 (vector; A) or pLX3805 (+MrpJ; B) and the isogenic mutants, ON (C) and ON&ΔmrpJ (D). Bar = 1 µm.

The mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ::aphA) is attenuated in the CBA mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection

When tested in the murine model through a co-challenge with the wild-type strain, the mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ::aphA) showed a significant reduction, as analyzed using a Wilcoxon-signed rank test, in its ability to colonize bladder [median log10 CFU/g tissue: 7.42 (wild type) versus 2.00 (mutant), p = 0.031] and kidneys [median log10 CFU/ g tissue: 5.63 (wild type) versus 3.92 (mutant), p = 0.002] (see Materials and methods). However, the precise interpretation of the attenuation of this mutant is difficult (see Discussion).

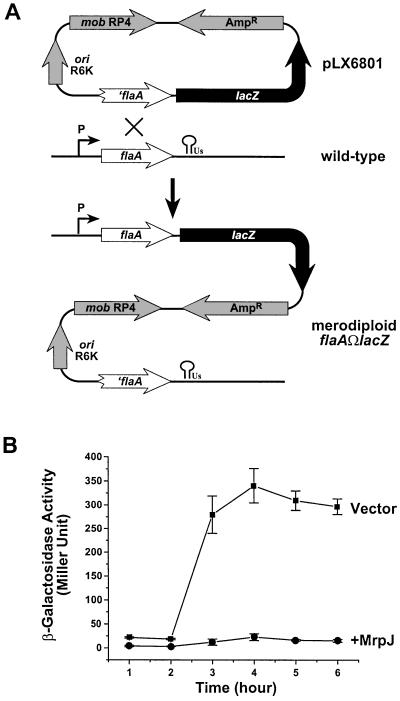

MrpJ represses the transcription of flaA, the flagellin gene

The repression of flagella production by MrpJ could be at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level. Given the fact that MrpJ shares sequence homology with many hypothetical regulatory proteins and contains a putative helix–turn–helix DNA binding domain, we hypothesized that MrpJ functions at the transcriptional level. To test this hypothesis, the merodiploid transcriptional fusion flaAΩlacZ was constructed from P.mirabilis HI4320 (see Materials and methods for details in strain construction). The merodiploid contains two copies of flaA gene, as shown in Figure 5A. However, only one copy is functional; this is transcribed from its native promoter and followed by a lacZ gene. The other copy, designated ′flaA, is not functional because it does not have a start codon. As expected, the merodiploid flaAΩlacZ exhibited no defect in flagella production or motility when compared with the wild-type strain (data not shown). To examine the effect of MrpJ on the transcription of flaA, the merodiploid flaAΩlacZ was transformed with either pLX7102 (vector) or pLX7201 (+MrpJ). Kanamycin-resistance constructs were used here because the merodiploid itself is ampicillin resistant. The transcription of flaA, as measured by β-galactosidase activity, was clearly repressed by elevated expression of MrpJ (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5. Elevated expression of MrpJ in P.mirabilis represses transcription of flaA. (A) Schematic drawing of the construction of the merodiploid transcriptional fusion flaAΩlacZ. Major features of the suicide construct pLX6801 (see Materials and methods for construction) are illustrated. These include ′flaA (the incomplete flaA), lacZ, R6K origin (ori R6K), RP4 mobilization factor (mob RP4), and the ampicillin-resistance marker (AmpR). The promoter and the terminator of the wild-type flaA transcript are also indicated. (B) β-galactosidase assays were performed on the merodiploid flaAΩlacZ containing pLX7102 (Vector, squares) or pLX7201 (+MrpJ, circles). Overnight cultures were standardized to an OD600 of 0.8 and then used 1:50 to inoculate fresh Luria broth. β-galactosidase activities were assayed in triplicate on samples collected every hour after growing at 37°C and 200 r.p.m.

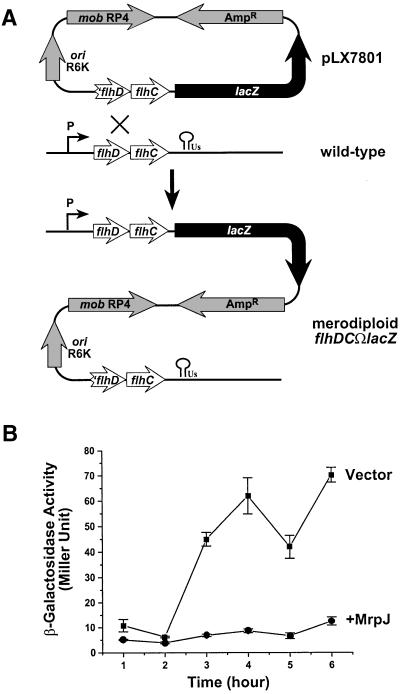

MrpJ represses the transcription of flhDC, the flagellar master operon

Flagella synthesis is regulated by a three-tier flagellar regulon (Macnab, 1996). Although we have demonstrated that the repression of flagella production by MrpJ is at the transcriptional level, it remains unclear at which level of the three-tier flagellar regulon MrpJ exerts its function. To determine whether MrpJ functions upstream or downstream of the flagellar master operon, flhDC, a merodiploid transcriptional fusion flhDCΩlacZ, was constructed from P.mirabilis HI4320 using a similar strategy. This merodiploid contains two copies of flhDC operon (Figure 6A). Again, only one copy is functional. This is transcribed from its native promoter and fused to a lacZ gene. The other copy, designated ′flhDC, is not functional because this operon does not have a promoter and ′flhD does not have a start codon. Likewise, the merodiploid flhDCΩlacZ exhibited no defect in flagella production or motility when compared with the wild-type strain (data not shown). To examine the effect of MrpJ on the transcription of flhDC, the merodiploid flhDCΩlacZ was transformed with either pLX7102 (vector) or pLX7201 (+MrpJ). Transcription of flhDC, measured by β-galactosidase activity, was also repressed by elevated expression of MrpJ (Figure 6B). Our data suggest that MrpJ functions at the transcriptional level directly on or upstream of the flhDC flagellar master operon.

Fig. 6. Elevated expression of MrpJ in P.mirabilis represses transcription of flaA. (A) Schematic drawing of the construction of the merodiploid transcriptional fusion flhDCΩlacZ. Features of the suicide construct pLX7801 (see Materials and methods for construction) are shown. These include ′flhDC (the incomplete flhDC), lacZ, R6K origin (ori R6K), RP4 mobilization factor (mob RP4), and the ampicillin-resistance marker (AmpR). The promoter and the terminator of the wild-type flhDC transcript are also indicated. (B) β-galactosidase assays were performed on the merodiploid flhDCΩlacZ containing pLX7102 (Vector, squares) or pLX7201 (+MrpJ, circles). Overnight cultures were standardized to an OD600 of 0.8 and then used 1:50 to inoculate fresh Luria broth. β-galactosidase activities were assayed in triplicate on samples collected every hour after growing at 37°C and 200 r.p.m.

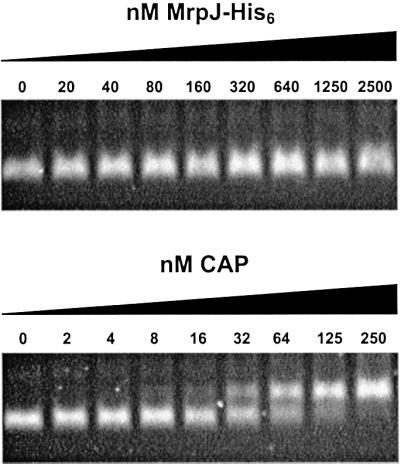

MrpJ does not bind to the flhDC flagellar master operon directly

To test whether MrpJ binds to the regulatory regions of the flhDC operon, gel mobility shift assays were performed on a 400-bp DNA fragment that contains the promoter region of flhDC. This fragment includes 174-bp upstream and 225-bp downstream of the transcription start site of the flhDC operon, which was mapped using primer extension by Furness et al. (1997). MrpJ was overexpressed and purified as a fusion protein tagged with a His6 tail (see Materials and methods for details). As shown in Figure 7, purified MrpJ-His6 protein did not bind to this regulatory region (–174 to +225) of the flhDC operon. Binding of purified catabolite activator protein (CAP) to this DNA fragment was included as a positive control for this experiment. Soutourina et al. (1999) demonstrated direct binding of CAP to the flhDC operon of E.coli. Furness et al. (1997) also revealed a putative CAP binding site in the flhDC operon of P.mirabilis, which was included in the 400-bp DNA fragment assayed here. Escherichia coli CAP (provided by Caiyi Li at University of Maryland) was purified using cAMP-agarose as described by Ghosaini et al. (1988). Figure 7 shows that CAP bound and retarded the 400-bp DNA fragment of the P.mirabilis flhDC operon at a concentration comparable to that described by Soutourina et al. (1999) for CAP binding of the E.coli flhDC operon.

Fig. 7. Gel mobility shift assay. The 400-bp DNA fragment containing the flhDC promoter region (–174 to +225) was incubated with various amounts of purified MrpJ-His6 or CAP, and then resolved on a 2.5% Nusieve agarose gel.

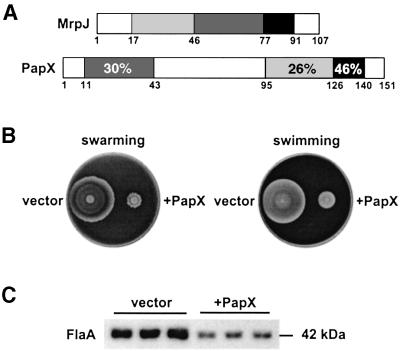

PapX is a functional homolog of MrpJ when expressed in P.mirabilis

Gene products encoded by the mrp operon (except MrpJ) share >29% amino acid sequence identity with those encoded by the pap (pyelonephritis-associated pilus) operon of E.coli P fimbriae (Bahrani and Mobley, 1994; Li et al., 1999). Although BLAST searches did not reveal any Pap homologs of MrpJ, further literature search led us to PapX, a 17-kDa protein encoded by the last gene on the pap operon (Marklund et al., 1992). Mutagenesis studies on papX by Marklund et al. (1992) indicated that PapX was not required for P fimbriae biogenesis. Due to the lack of an apparent phenotype of the papX null mutant, the function of PapX remained unknown. Sequence analysis of PapX and MrpJ revealed that these two proteins share limited homology at three domains (Figure 8A). To test whether papX encodes a functional homolog of MrpJ, we cloned papX downstream of a tac promoter in pLX3607 and then transformed the resulting construct, pDRM001, into P.mirabilis HI4320 (see Materials and methods). Proteus mirabilis containing pDRM001 (+PapX) showed reduced motility and flagella synthesis when compared with P.mirabilis containing pLX3607 (vector) (Figure 8B and C). It was demonstrated that PapX, when expressed in P.mirabilis, acts as a functional homolog of MrpJ, repressing flagella synthesis and motility.

Fig. 8. PapX of E.coli P fimbriae represses flagella synthesis in P.mirabilis. (A) Sequence homology between MrpJ and PapX. Domains of MrpJ and PapX that share amino acid sequence identity >25% have the same shading. (B) Proteus mirabilis containing pLX3607 (vector) or pDRM001 (+PapX) were assayed for swarming on 1.5% Luria agar or swimming in 0.35% Luria agar. (C) Three overnight cultures of each of the two strains were adjusted to the same optical density and equal volumes processed for SDS–PAGE and subsequent western blot analyses with antiserum against P.mirabilis flagella (FlaA).

Discussion

MrpJ, encoded by the last gene on the mrp operon, represents a novel fimbrial gene product that represses flagella synthesis, and therefore coordinates bacterial motility and adhesion. The characterization of PapX as a functional homolog of MrpJ in P fimbriae of E.coli, a model system for fimbriae assembled through the chaperone–usher pathway, suggests that such negative regulation of flagella synthesis by a fimbrial gene product may be present in other bacteria as well. However, a search through the E.coli fim operon, which encodes the type 1 fimbriae and resembles both the mrp and the pap operons, failed to identify any mrpJ homologs. We would like to point out again that PapX was not recognized as a homolog of MrpJ, nor MrpJ a homolog of PapX through BLAST searches. This indicates that functional homologs of MrpJ may not be easily identified based on sequence homology. Investigation of MrpJ homologs is also complicated by the phase-variable expression of many bacterial fimbriae and the subtlety of the mutant phenotype. These may be reasons why the function of PapX has eluded detection by conventional mutagenesis studies (Marklund et al., 1992). Furthermore, cloning of mrpJ homologs presents another difficulty since overexpression of MrpJ homologs could be toxic. Proteus mirabilis transformed with pLX2601, an initial plasmid construct of mrpJ that does not contain lacIq, displayed a pleiotropic phenotype including severe growth defect (data not shown).

The growth defect of strains overexpressing MrpJ could be considered as an artifact or an indication of an unknown function of MrpJ. We believe it is an artifact. Western blot analysis indicated that MrpJ was expressed at a low level and degraded quickly over time even in the ON mutant of P.mirabilis (data not shown). This is consistent with the lack of a ribosomal binding site in front of the mrpJ and MrpJ’s function as a transcription regulator. MrpJ shares limited homology (31% amino acid identity over 66 residues) with E.coli DicA protein, a repressor protein of division inhibition gene dicB (Bejar et al., 1986). However, we do not think MrpJ itself is involved in cell division, because its effect on growth only occurs at a concentration that would never be achieved under normal conditions. It is noteworthy that through a BLAST search, MrpJ hits five homologs in the newly sequenced genome of Caulobacter crescentus, a Gram-negative bacterium in which both flagella production and fimbrial biogenesis are regulated in a cell cycle-dependent manner (Laub et al., 2000). All five homologs were annotated as putative transcriptional regulators of the Cro/CI family (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AE005673).

The conclusion that MrpJ coordinates bacterial motility and adhesion is based upon two pieces of evidence. First, MrpJ represses flagella production; this has been demonstrated in this study. Secondly, expression of MrpJ concurs with the expression of MR/P fimbrial production. Previous evidence supporting mrpJ as part of the mrp operon comes exclusively from the sequence analysis. This indicates that mrpJ is only 22-bp downstream of mrpH and that no transcription terminator is found between mrpJ and mrpH. In this report, we present experimental data supporting mrpJ as transcribed from the mrp promoter residing on the invertible element. As shown in Figure 3, no difference in flagella production was observed between the OFF and the OFF&ΔmrpJ mutants. If mrpJ is transcribed from a promoter other than the one residing on the invertible element, both the OFF and the ON mutants should have produced less flagella than their isogenic ΔmrpJ mutants, the OFF&ΔmrpJ and ON&ΔmrpJ mutants, respectively. The absence of MrpJ function in the OFF mutant indicates that the transcription of mrpJ is also turned off when the invertible element is locked in the OFF orientation, suggesting that mrpJ is part of the mrp operon. In some uropathogenic E.coli, papX is not located directly adjacent to the fimbrial gene cluster, but as far as 2 kb downstream (Marklund et al., 1992). In such cases, it is yet to be determined whether or not the transcription of papX concurs with the production of P fimbriae.

We have demonstrated that MrpJ represses the transcription of the flhDC flagellar master operon. Gel mobility shift assay indicated that purified MrpJ-His6 protein did not bind to the 400-bp DNA fragment that contained the promoter region (–174 to +225) of the flhDC operon. However, it is possible that MrpJ may require a partner or a specific cofactor to bind to the promoter region of flhDC or that the binding of MrpJ to the flhDC operon may involve DNA sequences further upstream. Therefore, it remains inconclusive whether flhDC is a direct target of MrpJ. Further investigation of how MrpJ represses the transcription of flhDC may shed some light on the molecular events upstream of the flagellar master operon. Despite the details that we know about the molecular events downstream of the flhDC flagellar master operon, which include a three-tier cascade of regulation, the presence of sigma and anti-sigma factors as well as the comprehensive flagella exporting and assembly processes (Macnab, 1996), the events leading to the activation of the flhDC operon remain elusive. Many global transcriptional regulators including the CAP, the histone-like nucleoid-structuring (H-NS) protein, the histone-like protein HU, and the leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp) have been suggested to affect flagella synthesis (Silverman and Simon, 1974; Bertin et al., 1994; Hay et al., 1997; Nishida et al., 1997). Soutourina et al. (1999) have shown the direct binding of CAP and H-NS to the regulatory region of E.coli flhDC operon.

Western blot analysis (Figure 3B) indicated that the mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ) expressed less MR/P fimbriae compared with the wild-type strain. This observation was confirmed by repeated experiments, suggesting that MrpJ may also positively regulate the expression of MR/P fimbriae. However, studies on the merodiploid transcriptional fusion mrpΩlacZ in P.mirabilis indicated that MrpJ has no effect on transcription of the mrp operon in vitro (data not shown). It is possible that the deleted sequence of mrpJ, due to its proximity to the end of the mrp transcript, may be involved in formation of secondary structures that contribute to the mRNA stability. Nevertheless, this phenotype of the mrpJ null mutant adds another difficulty in interpreting its attenuated virulence in the murine model.

The mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ::aphA) displayed a significant reduction in its ability to colonize mouse urinary tract, possibly due to loss of the coordination of bacterial motility and adhesion. However, we can not rule out that the derepression of flagella synthesis may cause the attenuation of the mutant. We have previously demonstrated that flagella elicit a host immune response during experimental urinary tract infections in mice (Bahrani et al., 1991). Increased flagella production in the mutant may enhance eradication by host immune system. In addition, the decrease in MR/P fimbriae production, as mentioned above, may also lead to a reduction in attachment and subsequent colonization.

In summary, we have demonstrated that MrpJ, a novel fimbrial gene product, coordinates bacterial motility and adhesion by actively repressing transcription of the flhDC flagellar master operon. This is the first report of a fimbrial gene product that negatively regulates flagella synthesis despite the frequent observation of reciprocal expression of flagella and fimbriae in a variety of Gram-negative organisms. Our data also indicate that PapX of E.coli P fimbriae is a functional homolog of MrpJ, suggesting that such functional homologs may exist in other bacteria as well. This work draws our attention to a common theme in microbial pathogenesis—the temporal and spatial regulation of virulence factors during infection. The coordination of bacterial motility and adherence demands the reciprocal regulation of fimbriae and flagella production. Repression of the flagellar regulon by a fimbrial gene product represents a simple strategy that allows a bacterium to coordinate its movement and attachment.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and media

Proteus mirabilis HI4320 (urease-positive, hemolytic, and positive for MR/P, PMF and ATF fimbriae) was isolated from the urine of an elderly, long-term catheterized woman with significant bacteriuria (>105 CFU/ml) (Mobley and Warren, 1987). Escherichia coli CFT073 was isolated from the blood and urine of a woman diagnosed with pyelonephritis (Mobley et al., 1990). Escherichia coli DH5α was used as the host strain for transformation of plasmids other than the pR6K-derived suicide vector pGP704 (Miller and Mekalanos, 1988) and its derivatives, for which E.coli DH5αλpir was used as the host strain. Unless otherwise stated, Luria broth or agar (1.5%) was routinely used to culture bacteria and ampicillin (100 µg/ml) or kanamycin (50 µg/ml) was added when necessary. Non-swarming agar (Belas et al., 1991) was used to prevent P.mirabilis swarming when cultured on plates.

Plasmid construction

A 330-bp NcoI–HindIII fragment containing mrpJ was PCR-amplified from P.mirabilis HI4320 and cloned into the NcoI–HindIII sites of pQE60 (Qiagen) to construct pLX2601, in which mrpJ was placed under a LacI-repressible, and thus isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter (a tac promoter). Since P.mirabilis is lac– and the overexpression of MrpJ is toxic, a 1.2-kb SalI fragment containing lacIq was excised from pREP4 (Qiagen) and cloned into the XhoI site of pLX2601, resulting in pLX3805 (+MrpJ). This ensured tight regulation of the expression of MrpJ. As a vector control for pLX3805, pLX3607 (vector) was constructed by cloning the 1.2-kb SalI fragment into the XhoI site of pQE60. pLX5401 (ΔmrpJ) was constructed from pLX3805 by deleting the EcoRI–BglII fragment that contains the 5′ end of mrpJ. pLX7102 (vector) and pLX7201 (+MrpJ) were constructed from pLX3607 and pLX3805, respectively, by replacing their ampicillin-resistance markers with kanamycin-resistance cassettes. A 577-bp NcoI–HindIII fragment containing papX was PCR-amplified from E.coli CFT073 and cloned into the NcoI–HindIII sites of pLX3607 to construct pDRM001 (+PapX).

Preparation of rabbit antiserum against MrpJ

The plasmid construct pLX2601 was electroporated into E.coli M15 (Qiagen) containing pREP4, and the expression of MrpJ was induced by 1 mM IPTG. The predicted 12.5-kDa protein was resolved on an SDS-15% polyacrylamide gel and subsequently excised from the gel. To raise antiserum against MrpJ, the SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing MrpJ was emulsified in Freund’s complete adjuvant and subcutaneously injected into New Zealand White rabbits (100 µg protein/rabbit). At 4 and 6 weeks after the primary immunization, each rabbit was given a booster injection of 100 µg protein emulsified in Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. Serum was collected 2 weeks after the final booster.

Construction of isogenic mutants from P.mirabilis HI4320

The AflIII–PstI fragment (gray box in Figure 2) was cloned into a pGP704-based suicide vector, and the 180-bp BspHI–BglII fragment was replaced with the 1.3-kb kanamycin-resistance cassette. The resulting suicide construct, pLX2001, was electroporated into the wild-type HI4320, and kanamycin-resistant transformants were selected and screened for ampicillin resistance. Of the 250 kanamycin-resistant transformants screened, 29 were ampicillin susceptible. Four of these 29 ampicillin-susceptible and kanamycin-resistant transformants were verified by Southern blot analyses to be the mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ::aphA) (data not shown).

Another pGP704-based suicide construct, pLX8302, which contains the AflIII–PstI fragment with a deletion of the 180-bp BspHI–BglII fragment (see Figure 2), was electroporated into the mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ::aphA). One of many ampicillin-resistant and kanamycin-resistant transformants (as a result of a single crossover) was selected and then grown in nonselective medium to allow for a second crossover. After five passages in Luria broth, each time for 10–15 h at 37°C, the bacterial culture was plated on non-swarming agar to obtain single colonies. Five hundred of these single colonies were screened for ampicillin resistance and kanamycin resistance. Only one was both ampicillin susceptible and kanamycin susceptible; this was later confirmed to have the genotype ΔmrpJ by Southern blot analysis (Figure 3).

To construct the phase-locked mutant, we inserted the 1.3-kb kanamycin-resistance cassette into the BsmI site within mrpI (Figure 2). After the disruption of mrpI, the invertible element carried on the suicide construct is no longer able to switch. Two suicide constructs were selected: one with the invertible element locked in the OFF orientation (pLX8201) and the other in the ON orientation (pLX8408). Similarly, after electroporating pLX8201 or pLX8408 into the wild-type HI4320 or the mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ), kanamycin-resistant transformants were selected and screened for ampicillin resistance. The genotype of these ampicillin-susceptible and kanamycin-resistant transformants was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (Figure 3).

Electron microscopy

Overnight cultures of P.mirabilis strains expressing different levels of MrpJ were examined by electron microscopy. One drop of culture was placed on a Formvar-coated grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 5 min. Excess liquid was wiped off and the grid was washed three times with distilled water and stained with 1% sodium phosphotungstic acid (PTA) pH 6.8. All specimens were examined with a JEM-1200EX II electron microscope (JEOL, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

CBA mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection

The CBA mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection was originally developed by Hagberg et al. (1983) and then modified by Johnson et al. (1987). The assessment of virulence of a mutant strain through co-challenge with the wild-type strain has been described previously (Li et al., 1999). A group of 10 female CBA mice were transurethrally challenged with an ∼1:1 mixture of the wild-type strain and the mrpJ null mutant (ΔmrpJ::aphA). After 7 days, the mice were killed and quantitative bacterial counts in bladder and kidneys were determined on both non-swarming agar, which detects both the mutant and the wild type, and non-swarming agar containing kanamycin, which detects the mutant only. Values below 100 CFU/g tissue were set to 100 (limits of detection). A Wilcoxon-signed rank test was used to obtain p values.

Construction of merodiploid transcriptional lacZ fusions in P.mirabilis HI4320

First, a promoter-less lacZ was PCR-amplified from pRS415 (Simons et al., 1987) and cloned into the EcoRI–KpnI site of the suicide vector pGP704 (Miller and Mekalanos, 1988). Then, a 1.1-kb DNA fragment containing all except the first codon of flaA was PCR-amplified from P.mirabilis HI4320 and cloned in front of the promoter-less lacZ. This suicide construct, pLX6801, was then electroporated into P.mirabilis HI4320 to select for the ampicillin-resistant merodiploid transcriptional fusion, flaAΩlacZ, which resulted from a single crossover event at the flaA locus (Figure 5A). Similarly, for the flhDCΩlacZ fusion, a 930-bp DNA fragment starting from the second codon of flhD and extending to the stop codon of flhC was used for integration through homologous recombination (Figure 6A). Both merodiploid fusions, flaAΩlacZ and flhDCΩlacZ, were verified by Southern blot analysis (data not shown).

Overexpression and purification of MrpJ-His6 fusion protein

A 328-bp NcoI–BamHI fragment containing mrpJ but excluding its stop codon was PCR-amplified from P.mirabilis HI4320 and cloned into the NcoI–BglII sites of pQE60 (Qiagen) to construct pLX2501. MrpJ was expressed as a fusion protein tagged with a His6 tail from pLX2501 upon induction with IPTG (1 mM). The overexpressed MrpJ-His6 fusion protein was purified using Ni2+-NTA resin (Qiagen) under the native condition according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Purified MrpJ-His6 fusion protein was desalted on a PD-10 column (Pharmacia) buffered with 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0.

Gel mobility shift assay

A 400-bp DNA fragment containing the flhDC promoter region, from –174 to +225 (numbers in relative to the transcription start site, +1), was PCR-amplified and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) for sequencing. For gel mobility shift assay, this fragment was incubated with purified MrpJ-His6 or CAP for 15 min at room temperature in a binding buffer described by Goyard and Bertin (1997). Protein–DNA complexes were then resolved on a 2.5% Nusieve agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer and visualized with ultraviolet illumination after staining with ethidium bromide. For CAP binding, cyclic AMP (200 µM) was added to the binding reaction and the running buffer. For MrpJ-His6 binding, no difference was observed with or without cyclic AMP.

Primers for PCR

Primers for amplifying mrpJ from HI4320 were designed according to the sequence of the MR/P fimbrial gene cluster isolated from HI4320 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. Z32686). Sequencing of the mrpJ fragments confirmed that no unwanted mutations occurred. Primers for amplifying lacZ from pRS415 (Simons et al., 1987) were designed according to the sequence of E.coli lac operon (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. J01636). The amplified lacZ fragment was not verified by sequencing, but a β-galactosidase assay indicated that the lacZ gene was intact and functional. Primers for amplifying flaA from HI4320 were designed according to the sequence of the flaA gene isolated from P.mirabilis strain BB2000 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AF221596; Belas and Flaherty, 1994). Sequencing of this flaA fragment indicated that differences existed in the flaA gene between the two P.mirabilis strains, HI4320 and BB2000. Antigenic variation of flagellins from different strains is not uncommon. Because the merodiploid fusion generated using this flaA fragment did not exhibit any defect in flagella production or motility, we do not believe that any unwanted mutations occurred in the PCR-amplified fragment. Primers for amplifying flhDC fragments from HI4320 were designed according to the sequence of flhDC isolated from P.mirabilis strain U6450 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. U96964; Furness et al., 1997). Sequencing of the flhDC fragments, including both the fragment used for constructing the merodiploid fusion and the fragment used in the gel mobility shift assay, revealed a 1-bp deletion in the flhDC operon of strain HI4320 when compared with that of strain U6450. The deletion occurred at 175-bp downstream of the transcription start site mapped by Furness et al. (1997).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Public Health Service grant DK47920 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Caiyi Li for providing us with purified E.coli CAP for the gel mobility shift assay.

References

- Akerley B.J., Cotter,P.A. and Miller,J.F. (1995) Ectopic expression of the flagellar regulon alters development of the Bordetella–host interaction. Cell, 80, 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen-Vercoe E. and Woodward,M.J. (1999) The role of flagella, but not fimbriae, in the adherence of Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis to chick gut explant. J. Med. Microbiol., 48, 771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrani F.K., Johnson,D.E., Robbins,D. and Mobley,H.L.T. (1991) Proteus mirabilis flagella and MR/P fimbriae: isolation, purification, N-terminal analysis, and serum antibody response following experimental urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun., 59, 3574–3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrani F.K. and Mobley,H.L.T. (1994) Proteus mirabilis MR/P fimbrial operon: genetic organization, nucleotide sequence, and conditions for expression. J. Bacteriol., 176, 3412–3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar S., Cam,K. and Bouche,J.P. (1986) Control of cell division in Escherichia coli. DNA sequence of dicA and of a second gene complementing mutation dicA1, dicC. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 6821–6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belas R. and Flaherty,D. (1994) Sequence and genetic analysis of multiple flagellin-encoding genes from Proteus mirabilis. Gene, 148, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belas R., Erskine,D. and Flaherty,D. (1991) Transposon mutagenesis in Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol., 173, 6289–6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin P., Terao,E., Lee,E.H., Lejeune,P., Colson,C., Danchin,A. and Collatz,E. (1994) The H-NS protein is involved in the biogenesis of flagella in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 176, 5537–5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B.B. and Falkow,S. (1997) Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 61, 136–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser G.M. and Hughes,C. (1999) Swarming motility. Curr. Opin. Microbiol., 2, 630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness R.B., Fraser,G.M., Hay,N.A. and Hughes,C. (1997) Negative feedback from a Proteus class II flagellum export defect to the flhDC master operon controlling cell division and flagellum assembly. J. Bacteriol., 179, 5585–5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardel C.L. and Mekalanos,J.J. (1996) Alterations in Vibrio cholerae motility phenotypes correlate with changes in virulence factor expression. Infect. Immun., 64, 2246–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosaini L.R., Brown,A.M. and Sturtevant,J.M. (1988) Scanning calorimetric study of the thermal unfolding of catabolite activator protein from Escherichia coli in the absence and presence of cyclic mononucleotides. Biochemistry, 27, 5257–5261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyard D. and Bertin,P. (1997) Characterization of BpH3, an H-NS-like protein in Bordetella pertussis. Mol. Microbiol., 24, 815–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg L., Engberg,I., Freter,R., Lam,J., Olling,S. and Svanborg-Eden,C. (1983) Ascending, unobstructed urinary tract infection in mice caused by pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli of human origin. Infect. Immun., 40, 273–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N.A., Tipper,D.J., Gygi,D. and Hughes,C. (1997) A non-swarming mutant of Proteus mirabilis lacks the Lrp global transcriptional regulator. J. Bacteriol., 179, 4741–4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrichsen J. (1972) Bacterial surface translocation: a survey and a classification. Bacteriol. Rev., 36, 478–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultgren S.J., Jones,C.H. and Normark,S. (1996) Bacterial adhesin and their assembly. In Neidhardt,F. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp. 2730–2757.

- Johnson D.E., Lockatell,C.V., Hall-Craigs,M., Mobley,H.L.T. and Warren,J.W. (1987) Uropathogenicity in rats and mice of Providencia stuartii from long-term catheterized patients. J. Urol., 138, 632–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub M.T., McAdams,H.H., Feldblyum,T., Fraser,C.M. and Shapiro,L. (2000) Global analysis of the genetic network controlling a bacterial cell cycle. Science, 290, 2144–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Johnson,D.E. and Mobley,H.L.T. (1999) Requirement of MrpH for mannose-resistant Proteus-like fimbriae-mediated hemagglutina tion by Proteus mirabilis. Infect. Immun., 67, 2822–2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnab, R.M. (1996) Flagella and motility. In Neidhardt,F. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp. 123–145.

- Marklund B.I., Tennent,J.M., Garcia,E., Hamers,A., Baga,M., Lindberg,F., Gaastra,W. and Normark,S. (1992) Horizontal gene transfer of the Escherichia coli pap and prs pili operons as a mechanism for the development of tissue-specific adhesive properties. Mol. Microbiol., 6, 2225–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller V.L. and Mekalanos,J.J. (1988) A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol., 170, 2575–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley H.L.T. (2000) Virulence of the two primary uropathogens. ASM News, 66, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley H.L.T. and Warren,J.W. (1987) Urease-positive bacteriuria and obstruction of long-term urinary catheters. J. Clin. Microbiol., 25, 2216–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley H.L.T., Green,D.M., Trifillis,A.L., Johnson,D.E., Chippendale, G.R., Lockatell,C.V., Jones,B.D. and Warren,J.W. (1990) Pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli and killing of cultured human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells: role of hemolysin in some strains. Infect. Immun., 58, 1281–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley H.L.T., Belas,R., Lockatell,C.V., Chippendale,G., Trifillis,A.T., Johnson,D.E. and Warren,J.W. (1996) Construction of a flagellum-negative mutant of Proteus mirabilis: effect on internalization by human renal epithelial cells and virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun., 64, 5332–5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida S., Mizushima,T., Miki,T. and Sekimizu,K. (1997) Immotile phenotype of an Escherichia coli mutant lacking the histone-like protein HU. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 150, 297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman M. and Simon,M. (1974) Characterization of Escherichia coli flagellar mutants that are insensitive to catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol., 120, 1196–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons R.W., Houman,F. and Kleckner,N. (1987) Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene, 53, 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto G.E. and Hultgren,S.J. (1999) Bacterial adhesins: common themes and variations in architecture and assembly. J. Bacteriol., 181, 1059–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutourina O., Kolb,A., Krin,E., Laurent-Winter,C., Rimsky,S., Danchin,A. and Bertin,P. (1999) Multiple control of flagellum biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: role of H-NS protein and the cyclic AMP-catabolite activator protein complex in transcription of the flhDC master operon. J. Bacteriol., 181, 7500–7508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall D. and Kaiser,D. (1999) Type IV pili and cell motility. Mol. Microbiol., 32, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren J.W., Tenney,J.H., Hoopes,J.M., Muncie,H.L. and Anthony, W.C. (1982) A prospective microbiologic study of bacteriuria in patients with chronic indwelling urethral catheters. J. Infect. Dis., 146, 719–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Li,X., Johnson,D.E., Blomfield,I. and Mobley,H.L.T. (1997) In vivo phase variation of MR/P fimbrial gene expression in Proteus mirabilis infecting the urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol., 23, 1009–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]