Abstract

Voucher-based reinforcement therapy (VBRT) is an effective drug abuse treatment, but the cost of VBRT rewards has limited its dissemination. Obtaining VBRT incentives through donations may be one way to overcome this barrier. Two direct mail campaigns solicited donations for use in VBRT for pregnant, postpartum, and parenting drug users in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and in Los Angeles, California. In Toronto, 19% of those contacted over 2 months donated $8,000 ($4,000/month) of goods and services. In Los Angeles, nearly 26% of those contacted over 34 months donated $161,000 ($4,472/month) of goods and services. Maintaining voucher programs by soliciting donations is feasible and sustainable. The methods in this article can serve as a guide for successful donation solicitation campaigns. Donations offer an alternative for obtaining VBRT rewards for substance abuse treatment and may increase its dissemination.

An empirically validated contingency management (CM) approach is to create an incentive-based economy in which patients earn vouchers exchangeable for goods and services contingent on engaging in therapeutically appropriate behavior. This approach has been particularly effective in treating a wide range of substance abuse disorders (for reviews, see Higgins & Petry, 1999; Higgins & Silverman, 1999; Petry, 2000). Within a behavioral framework, drug use is viewed as a special case of operant behavior maintained by the reinforcing effects of the drug. These behaviors can be influenced through CM approaches to operant behavior (Bigelow, Stitzer, Griffiths, & Liebson, 1981). The successful implementation of CM programs requires the selection of appropriate and effective reinforcers, which can compete with the reinforcement provided by drugs or by other problem behavior. These reinforcers can then be used to increase the frequency of behaviors that are inconsistent with drug use and reinforce new therapeutically appropriate responses.

A particularly effective means of implementing CM for treating substance abuse is through the use of voucher-based reinforcement therapy (VBRT). In VBRT, patients earn vouchers exchangeable for goods and services contingent on performance of verifiable behaviors such as drug abstinence (e.g., Higgins et al., 1994), counseling attendance (e.g., Svikis, Lee, Haug, & Stitzer, 1997), or engaging in other program-assigned, therapeutically appropriate behaviors (e.g., Iguchi, Belding, Morral, Lamb, & Husband, 1997). Such programs have effectively engendered abstinence from a range of abused substances (cf. Petry, 2000, for review). The efficacy, reliability, and generality of VBRT in improving different treatment outcomes across various substance-abusing populations is remarkable and suggests that its widespread application to substance abuse treatment could be particularly fruitful.

Integrating VBRT into community practice has been challenging, and the integration process has been slow. Although there are likely several factors accounting for difficulties disseminating this treatment strategy (cf. Kirby, Amass, & McLellan, 1999), the front-end cost of supporting voucher program rewards continues to present a significant barrier to their broadscale use by community providers. Assessing the cost benefit or cost effectiveness of drug abuse treatments is difficult and is an area of study in its infancy (cf. Sindelar & Fiellin, 2001). Thus, it remains unclear whether the costs of financing VBRT might be offset by its effectiveness in reducing the negative consequences of drug use, such as crime, hospitalizations, and unemployment, and in increasing positive indices of social functioning, such as employment, family functioning, and mental health. Although patients participating in empirical evaluations of VBRT typically earn about 50% of voucher rewards available, an average cost of $500 to $600 per client over a 12-week program to support the voucher program is not uncommon (cf. Higgins, Alessi, & Dantona, 2002; Petry & Simcic, 2002). Efforts to reduce the cost of voucher program rewards by using lottery-based prize drawings are encouraging and suggest that voucher programs can be implemented at lower cost without sacrificing efficacy of the intervention (Petry & Martin, 2002; Petry, Martin, Cooney, & Kranzler, 2000; Petry, Martin, & Finocche, 2001). However, lower magnitude voucher interventions are not always successful (Jones, Haug, Stitzer, & Svikis, 2000; Silverman, Chutaupe, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 1999; Stitzer & Bigelow, 1983, 1984). Further, most evaluations of voucher therapy have relied on external sources of funding to purchase reinforcers. The long-term sustainability of this treatment approach in community-based clinics not only may require using lower cost interventions but also may require finding alternative sources of funding to acquire the rewards used in VBRT.

One strategy for reducing costs associated with VBRT rewards is to solicit donations of goods and services from the community and use them to reinforce behavior change. In 1997, we reported briefly on our first effort to support a voucher-based treatment program for pregnant women in Toronto, Ontario, Canada with community donations (Amass, 1997). We followed this work with a preliminary report from a larger scale campaign in Los Angeles, California (Rosen, Kamien, Ishisaka, & Amass, 2001). Another group reported successfully conducting a VBRT study for smoking cessation among pregnant women wherein monetary vouchers were “purchased with funds voluntarily donated from healthcare organizations, businesses and foundations” (Donatelle, Prows, Champeau, & Hudson, 2000, p. iii68). Further, the approach of soliciting community donations for voucher programs has been mentioned as being feasible and showing promise for helping reduce the cost of VBRT, although no details regarding donation solicitation methods or success of the campaign were provided (Petry & Martin, 2002; Petry, Petrakis, et al., 2001).

In the current article, we discuss the fund-raising techniques, feasibility, and sustainability of establishing a community-sponsored on-site voucher store for use in a CM program for pregnant, postpartum, and parenting substance abusers. The Method section provides guidelines for replicating these fund-raising techniques.

Method

Setting

The Pregnant and Clean Project (Project PAC) is a randomized, controlled trial of a CM program designed for cigarette-smoking pregnant, postpartum, and parenting drug users that can be integrated into an ongoing care program for this population. Patients receive vouchers contingent on the reductions in smoking. Vouchers are redeemable at an on-site store containing a variety of maternity products, clothing, toys, books, and gift certificates for local grocery stores, restaurants, theaters, and attractions. The on-site store is unique because it is funded and stocked entirely by donations from corporate and private sponsors. The first fund-raising effort took place at a provincially funded, outpatient treatment center located within the Addiction Research Foundation in Toronto. The second fund-raising effort took place at the Friends Research Institute in Los Angeles in affiliation with The Shields for Families Genesis and Exodus treatment programs in Watts and Compton, California, respectively. The current randomized trial in Los Angeles is ongoing, and results will be presented in a subsequent report.

Fund-Raising Procedures

A direct mail campaign was developed to solicit donations. This type of campaign was selected because of constraints on time, staff, and materials. Staff resources in Toronto included 30% effort of a research assistant to solicit donations. Staff resources in Los Angeles included a fund-raiser working half time to solicit and manage donations for the first 27 months, after which one of the project’s research assistants took over the entire donation solicitation campaign and devoted about 1 day per week to its maintenance. A limited materials budget for postage, letterhead, brochures, and envelopes was provided by the institution (in Toronto) and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA-13638 (in Los Angeles) and cost about $50 per month. On the basis of results of similar campaigns conducted with social service agencies, a positive response rate (number donating/number solicited) between 10% and 15% was predicted (Henderson, 1984).

Components of the Fund-Raising Campaigns

We believe several features of our donations campaigns were key to their success. Many of these features were adapted from guides for fund-raising (Henderson, 1984; Wyman, 1993). We offer these features as guidelines for mounting successful donation campaigns for supporting VBRT for substance abuse.

In our opinion, the key components of the fundraising campaign included (a) targeting goods and services to stock in the voucher store, (b) identifying potential sources of community sponsorship, (c) identifying the correct person within an organization to approach for a donation, (d) constructing an effective donation solicitation package, (e) following up all mail sent out with phone calls and other contacts, and (f) sending timely thank-you notes and other communications to donors.

We prepared solicitation packages and tracked all donor contacts, solicitations mailed, responses from potential donors, as well as the timing of follow-up contacts using a bespoke computer database because we needed to carefully track the donations campaign and its results for research purposes. However, a good paper filing system and a calendar could accomplish the same functions.

Targeting Goods and Services

Identifying which products to seek as donations is the first step in focusing the fund-raising effort. Practitioners should survey their clientele to determine the putative capacity of a variety of activities or events occurring within their community, as well as a variety of retail items, to function as reinforcers. Surveying clients, the consumer of treatment services, may help provide clinicians with better insight regarding what nondrug alternatives are likely to function as reinforcers. Several surveys with substance-abusing patients receiving treatment for opioid dependence are illustrative of a positive relationship between those privileges rated as preferred in surveys (Amass, Bickel, Crean, & Higgins, 1996; Chutuape, Silverman, & Stitzer, 1998; Kidorf, Stitzer, & Griffiths, 1995; Schmitz, Rhoades, & Grabowski, 1994; Stitzer & Bigelow, 1978; Yen, 1974) and those that function as effective reinforcers for maintaining behavior change (Iguchi, Stitzer, Bigelow, & Liebson, 1988; Milby, Garrett, English, Fritschi, & Clarke, 1978; Stitzer, Bigelow, & Iguchi, 1993; Stitzer, Bigelow, & Liebson, 1980; Stitzer, Iguchi, & Felch 1992). Surveys, therefore, need to be integrated into fund-raising efforts so the goods targeted for donations represent those likely to function as reinforcers.

Seven basic categories of goods and services were targeted for donations in Toronto: baby accessories, baby clothes, toys, maternity wear/products, diapers, entertainment/recreation, and equipment. In Los Angeles, we expanded the goods and services targeted for donations to 16 categories: baby goods, baby services, children’s goods, children’s services, women’s goods, women’s services, toys, general goods, handcrafted goods, general services, household needs, self-improvement, physical fitness, cinema, videos/books/music, and entertainment/recreation/sports. In both efforts, the categories were selected by identifying the range of goods marketed to pregnant and parenting women in the community and interviewing clinic staff and clients regarding what incentives they thought would be effective. From these categories, we compiled lists of items we wanted to stock in the voucher stores, keeping in mind the size of the store space available. We tried to stock products and gift certificates that would promote positive lifestyle changes (i.e., non-drug-using activities) so that items obtained with voucher points might expose our clients to positive reinforcers available in their local community.

Identifying Potential Donors

Once a list identifying the range and types of goods and services to stock in the voucher store was developed, we identified potential manufacturers and local retailers who make or sell the products we selected to stock. In Toronto, before the widespread use of the World Wide Web, this process was more difficult than it is now, and we used a target marketing guide, a book trade listing, a local children’s activity guide, and the local yellow pages. In Los Angeles, we used Internet search engines extensively to locate corporate Web sites for companies making the product in which we were interested, then plumbed the depths of those Web sites to identify where in the corporate structure to aim our solicitations. We also brainstormed among our staff for targets, then used the World Wide Web to find the appropriate contact for a given target.

Identifying the Correct Person Within an Organization

Before sending any solicitation package, we always called the organization first to discover the process by which the organization makes charitable donations, the person responsible for making donation decisions, the correct mailing address, the spelling of the contact’s name, and any other information we could regarding the organization’s donation philosophy. For example, the end of the year is sometimes the best time to contact some entities because making donations can confer a tax advantage. If we were able to speak directly to the person making donation decisions, we tried to convey our enthusiasm for the project and get him or her involved with what we were doing. When we then sent the solicitation package, we made sure to refer to our conversation so that the potential sponsor would remember us when he or she got the letter. In general, the key was to discover as much as we could about an organization before sending the package, so it could reflect a direct contact of some sort.

Constructing an Effective Donations Request Package

A number of fund-raising techniques are available to solicit community donations to help finance a VBRT program. Among these are direct mail, telephone solicitation, and event fund-raising. We chose to combine direct telephone solicitation, as discussed above, with a direct mail campaign to contact our carefully chosen potential donors because this approach is easy to implement and relatively inexpensive. Our solicitation package included a donation request letter that referenced our initial phone contact to the person identified and a sponsorship brochure. The key aspects of the donation request letter included keeping it simple and limited to a single page, devoid of jargon; spelling out who we are and what our mission is (“to improve the health of pregnant women and their children by reducing cigarette, alcohol and other drug use during pregnancy”); describing what our program was doing, what specifically they could donate to help (e.g., provide grocery gift certificates), and what benefit donating might confer on them (e.g., a tax deduction, publicity describing them in a positive light as a concerned member of the community); and stating that we would contact them to follow up. The sponsorship brochure included further details about the project and listed donors that already had participated. The cover letter was always signed in blue ink to further emphasize to the potential sponsor that this was not a bulk mailing. Materials needed for the solicitation package can be prepared inexpensively using an ink-jet printer and heavy stock paper.

Planning Follow-Up to Donor Solicitations

We believe that our follow-up activities were also important keys to the success of the donation campaigns. Follow-up activities included sending out thank-you notes rapidly (see below), calling the person who actually made the donation to thank him or her personally, responding promptly to any queries posed by potential sponsors, and sending seasonal acknowledgments to remind sponsors of their donation to our project. We believe our follow-up activity served several purposes: It allowed us to directly answer any questions the potential donor might have, gave us an additional opportunity to convey our enthusiasm for the project, gave the potential donor an opportunity to request any additional material they might need (e.g., a 501(c)(3) letter indicating the tax-exempt status of our organization), and helped prevent us from getting lost in the shuffle of their mail.

Sending Prompt Thank-You Notes

We usually sent out thank-you notes to donors within 1 day of a donation arriving or being picked up. It is common for sponsors to remark that they rarely hear from organizations to which they have donated. Receiving prompt thank-you notes reinforces the sponsor’s act of giving and increases the likelihood that they will donate again. We also sent out Christmas cards to donors expressing our gratitude and included pictures of the donations in the on-site stores. Finally, we devised a schedule of contacting donors on a regular basis to re-solicit donations. Even in cases in which we had been denied on the first solicitation, companies sometimes responded positively when approached a second or third time. In some cases, companies had a schedule that defined how frequently they could donate (e.g., four times per year), and we made sure that we contacted them according to their schedule. The key here was to be persistent, organized, and timely in thanking the donors and in asking them to donate again.

Timeline

Toronto

During a 2-month period from July 1, 1995 through August 31, 1995, 198 corporations, manufacturers, and local retailers were solicited by mail. In addition, local volunteers were solicited through posters, word of mouth, and electronic mail advertising. Responses to the campaign were monitored over the following 8 months.

Los Angeles

During a 34-month period from July 17, 2000 through May 7, 2003, 369 unique contacts were made with corporations, local retailers, local attractions, restaurants, theatres, cinemas, and individuals. The campaign is ongoing, and responses are being continuously monitored. However, for the present article, responses are limited to those received earlier than May 7, 2003.

Results

Positive Response Rate

Toronto

Of the 198 potential donors contacted, 38 provided donations, yielding a positive response rate of 19.19%. The following groups comprised our donors: 53% were manufacturers, 34% were local attractions/restaurants, and 13% were local retailers. A list of the Toronto donors is provided in the appendix. The retail value of all donated goods and services, estimated by surveying the prices of these goods in retail stores at the time they were donated, totaled approximately $8,000, representing a return of $4000 per month during the 2 months that the fund-raising campaign was active.

Los Angeles

Of the 369 potential donors contacted, 95 provided donations, yielding a positive response rate for all types of contacts of 25.75%. The following groups comprised our donors: 42% were corporations, 17% were individuals, 12% were charitable groups, 12% were local retailers, 7% were theatres and cinemas, 2% were local attractions, 2% were local restaurants, and the remaining 6% of donors fell into other categories. A list of the Los Angeles donors is provided in the appendix. The retail value of all goods and services donated to the program totaled approximately $161,000, representing a return of $4,472 per month for the 34 months covered in this article.

Types of Donations

Toronto

Goods were donated in the seven categories listed above (on the basis of their dollar value) in the following percentages: 49% in entertainment/recreation, 19% in toys, 13% in baby clothes, 9% in maternity wear/products, 4% in equipment, 3% in baby accessories, and 3% in diapers (see Figure 1, left). Examples of specific donated items in each category include the following: passes to the Royal Ontario Museum and the Famous Players Dinner and Theatre (entertainment/recreation), stuffed animals and puppets (toys), knitted sweaters and hats (baby clothes), pacifiers and bottle liners (maternity wear/products), breast pump kit (equipment), laundry bags and diaper pins (baby accessories), and Pampers Infant and Huggies Pull-Ups (diapers).

Figure 1.

Distribution (according to dollar value) of donations received to the types of donations targeted in Toronto (left) and Los Angeles (right).

Los Angeles

Goods were donated in the 16 categories listed above (on the basis of their dollar value) in the following percentages: 77% in women’s goods, 8% in baby goods, 4% in children’s goods, 4% in general goods, 3% in toys, 2% in videos/books/music, 1% in handcrafted goods, and 1% in household needs. Donations of baby services, children’s services, women’s services, general services, self-improvement services, physical fitness services, cinema goods, and entertainment/recreation/sports goods comprised less than 1% of the total donations value obtained (see Figure 1, right). Examples of specific donated items in each category include the following: sanitary napkins and jewelry (women’s goods), wipes and clothing (baby goods), hats and socks (children’s goods), travel shampoos and restaurant gift certificates (general goods), dolls and games (toys), books and Tower Records gift certificates (videos/books/music), baby blankets and quilts (handcrafted goods), and grocery gift certificates and dishes (household needs).

Sustainability of the Donations

Toronto

Because the donation solicitation campaign in Toronto lasted only 2 months, data regarding sustainability are not available for this campaign.

Los Angeles

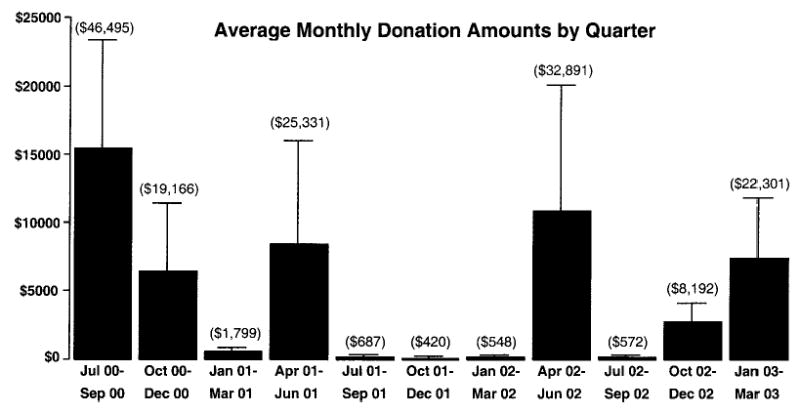

There were 95 unique donors to the program over 34 months, and 24 (25.3%) of them donated to our program more than once. These 24 repeat donors averaged 2.4 ± 0.2 (M ± SEM) donations each and made their donations at an average interval of 27.0 ± 4.0 months. Nine donors increased the value of their donation in subsequent donations, six decreased the value of their donations, and nine donated the same amount on subsequent donations. Figure 2 shows the average monthly dollar amount donated per quarter over 33 months of the donation solicitation campaign. Although our rate of solicitation remained relatively constant throughout the period, the rate of donations was punctuated periodically by larger donation amounts, and there were some months of relatively few donations. These fluctuations were primarily due to periodic large donations by a few of the donors. Overall, the success of the donation solicitation campaign was maintained over a 33-month period.

Figure 2.

Average monthly donation amounts in dollars in the Los Angeles campaign. Data are presented for quarters from July 2000 through March 2003. Amounts were estimated by surveying the prices of these goods in retail stores at the time they were donated. Amounts in parentheses are the total amount collected per quarter. Vertical lines represent + SEM.

Discussion

Main Findings

In this article, we report that soliciting and acquiring donations sufficient and suitable for maintaining community-sponsored voucher programs is feasible and sustainable. In Toronto, the donation solicitation campaign resulted in a positive response rate of 19%, whereas in Los Angeles, this rate climbed to greater than 25%, in both cases exceeding the 10% to 15% usually predicted for direct mail campaigns (Henderson, 1984). Further, the success of the donation solicitation campaign in Toronto was replicated in Los Angeles 5 years later, in different communities, for different populations, with different targeted donors, different targeted donations, and different personnel managing the campaign. As shown in Figure 1, there were large differences in the types of donations obtained between the two campaigns. Several aspects of the campaigns could have contributed to these differences, including cultural and business differences between Toronto and Los Angeles, as well as the expansion of the goods targeted for solicitation and the much longer duration of the campaign in Los Angeles. Despite these substantial differences, each campaign generated about $4,000 per month worth of donated products and services, suggesting the viability of this approach for use by other treatment providers or groups conducting research in this area. This replication of successful donation solicitation campaigns suggests that businesses and individuals in local communities would donate goods and services to CM programs for pregnant and postpartum drug abusers. Moreover, as we found in our Los Angeles campaign, donations can be garnered at a consistent rate and in amounts sufficient to sustain typical voucher programs. The fund-raising approach described may be a viable alternative for obtaining material reinforcers for use in VBRT programs.

Cost and Benefits

The on-site voucher store offers at least three potential advantages over voucher programs that purchase reinforcers as they are needed. First, the exchange of vouchers for goods can closely follow presentation of the target behavior, increasing temporal contiguity between the behavior and reinforcer. Second, patients have an opportunity to preview goods in the on-site store, exposing them to available reinforcers on a regular basis, which may have a priming effect. Third, establishing a community-sponsored voucher program reinforces the role of the local community in substance abuse treatment programming and offers a potentially long-term solution to funding CM for community-based substance abuse treatment.

This article demonstrates that fund-raising for VBRT can be successful using limited materials and, overall, about 2 days per week of one staff person’s effort. At the outset, more personnel time might be helpful in order to rapidly stock an on-site store with sufficient inventory to support the voucher program. Once an inventory is established, however, staff effort to maintain enough donations to continue the program can be reduced. The implementation of any new treatment program requires some reallocation of resources to achieve program goals. The same should be expected for successful VBRT programs, and the need to commit funds or devote personnel resources to its successful implementation should not be seen as an insurmountable barrier to adopting what is otherwise a highly effective treatment for substance abuse.

Nonetheless, many treatment programs may be too small to be able to spare the personnel resources necessary for a successful donations solicitation campaign. Thus, this fund-raising approach may not be feasible for smaller programs. Certainly, allocating expensive counseling staff for soliciting donations rather than for generating clinic revenue through client fees is probably untenable. However, discussions with treatment providers have suggested that larger programs already may have fund-raising development personnel, or nonclinical or support staff who might be able to perform donation solicitation duties that would result in obtaining incentives at lower overall cost than buying the incentives outright (R. Bilangi, personal communication, May 8, 2003; E. Ennis, personal communication, May 8, 2003). Alternatively, harnessing volunteer efforts from community service organizations or individuals may provide a means of soliciting donations with little cost to a program.

Limitations

Financing reward purchases for VBRT through means other than government funding is important to demonstrating sustainability of this treatment approach. The approximately $161,000 in goods and services donated by 95 unique donors over 34 months to our Los Angeles program illustrates the viability and sustainability of our fund-raising approach. However, this approach has some limitations.

Our success securing donations may have been due to the special population (pregnant and parenting substance abusers) and to the fact that our program might help reduce health risks to unborn babies and young children. Unborn babies and children provide compelling reasons to support such programs. However, our experience securing donations for this program suggests that sponsors may be willing to donate for other populations of substance abusers provided the potential health benefits to the user (e.g., decreased drug use) and benefits to the community (e.g., reduction in local crime) are clearly noted in the solicitation materials.

Community programs may not have the resources to dedicate personnel to fund-raising. As noted previously, we have found that a well-designed direct mail campaign requires only about 2 days’ effort by one person per week to maintain. Further, it is both reasonable and feasible that the fund-raising efforts could be supported through existing program staff and volunteer resources. Although we have not used volunteers to solicit donations in Los Angeles, a volunteer working about 2 days/week accomplished most of the donation solicitation in Toronto.

In our experience, acquiring product donations has been straightforward. However, securing cash donations to be converted into nonperishable food, along with obtaining repeated donations of gift certificates for other basic needs, has been difficult. Although we have successfully acquired gift certificates to local grocery stores and for other basic needs, these donations tend to be small and occur perhaps only once or twice per year. One way of combating this problem is to inform donors of how enthusiastically their donations were received and to solicit them again. We also have found that donation programs from several grocery stores are locally managed and soliciting donations from several different branches sometimes increases success.

Other Avenues for Generating Reinforcers

Although we offer one solution to offsetting the cost of voucher rewards for VBRT and enhancing the potential transfer of VBRT to real-life settings in the present study, multiple strategies are likely needed to offset costs associated with VBRT programs. Other approaches that rely on state-subsidized programs are also intriguing. For example, redistributing disability income contingent on drug abstinence through representative payees has been investigated in cohorts of schizophrenic patients with comorbid cocaine dependence (cf. Shaner, Tucker, Roberts, & Eckman, 1999), and preliminary data suggest that this is a reasonable and effective strategy for reducing illicit drug use in this special population. Developing reinforcement-based therapeutic workplaces in which access to paid employment is contingent on drug abstinence also has been a successful CM method for treating drug abuse that may offset costs (Silverman, Svikis, Robles, Stitzer, & Bigelow, 2001; Silverman et al., 2002). Further, salary subsidies and medical and other benefits paid for by city or state governments may be available to welfare recipients participating in such VBRT programs (Silverman et al., in press). Finally, other novel approaches include examining existing revenue streams within the clinic (e.g., treatment fees) to determine the availability and feasibility of redistributing portions of this revenue to clients contingent on their performance (Amass, Ennis, Mikulich, & Kamien, 1998). Our group is presently conducting controlled evaluations of contingent fee rebates with cash-paying clients receiving community-based drug treatment in California. The results of this and other ongoing research will provide further information on the feasibility of these alternative strategies for implementing VBRT in community-based treatment programs.

Conclusion

These data demonstrate the feasibility of initiating and sustaining community-financed voucher rewards for CM programs. This demonstration of communities’ willingness to support the reward component of voucher programs is encouraging, and these results support the viability of fund-raising as one strategy for offsetting costs associated with the use of VBRT. The overall significance of the work is important not only because the costs associated with implementing VBRT have been identified as a significant barrier to their widespread adoption (cf. Kirby et al., 1999) but also because voucher programs might positively affect substance abusers in more than one domain. In addition to directly affecting their drug abuse, VBRT programs can provide access to food, clothing, and other basic necessities that these individuals might otherwise lack because of their generally low socioeconomic status. Further research is obviously needed to demonstrate that the fund-raising strategy can be managed by clinics using existing nonclinical personnel or local volunteers. However, our discussions with community treatment providers indicate this is not only possible but is in fact occurring successfully in at least one comprehensive treatment service (E. Ennis, personal communication, May 8, 2000).

Acknowledgments

We thank Jane Collins, Jody Snelgrove, and Patricia Meffe from Toronto, Ontario, Canada; and Beverly Rosen, Tara Samiy, and Sarah DiGregorio from Los Angeles, California, for their assistance with this project. We acknowledge the following clinic directors for a lively e-mail discussion regarding the feasibility of using staff to solicit donations: Al Cohen, Aegis Medical Systems; Richard Bilangi, Connecticut Counseling Centers; Eric Ennis, University of Colorado School of Medicine; Richard Drandoff, ChangePoint, Inc.; Ron Jackson, Evergreen Treatment Services; and Bill Wendt, Signal Behavioral Health Network. We are also grateful for the generous support of the Canadian Pregnant and Clean Project (Project PAC) volunteers, with special thanks to Clair Bondy and Gary Garacino. We thank the Canadian and Los Angeles Project PAC sponsors, who are listed in the appendix, for their support of our program.

Appendix

Canadian and Los Angeles Pregnant and Clean Project (Project PAC) Sponsors

Canadian sponsors

Annick Press; Art Gallery of Ontario; Blockbuster Video; C.N. Tower; Casa Loma; Chatelaine; Condom Sense—A Safe Investment; Cozy Cuddles Baby Products; Elfe Juvenile Products; Famous People Players; Famous Players; Fisher Price; Flare; Gage Distribution Company; Gerber (Canada), Inc.; Irwin Toy, Limited; Johnson & Johnson, Inc.; Keg Restaurants, Ltd.; Kelsey’s Restaurants; Kidstuff Toy Store; Loblaws, McClelland & Stewart, Inc.; Modern Woman, Morgan & Ives; Ontario Science Centre; Parentbooks; Penguin Books; Pizza Pizza; Playtex, Limited; Royal Ontario Museum; S. R. Kertzer, Limited; Sandylion Sticker Designs, Scholastic Canada, Ltd.; Seams Small; Senitt Dolls and Puppets, Ltd.; Stoddart Publishing Co., Limited; The Canadian Stage Company; the children’s bookstore; The Second City; Today’s Parent Group; TOYS “R” US (Canada), Ltd.; and Zellers (Rexdale Plaza).

Los Angeles sponsors

Individual and anonymous donors; 99 Cents Only Stores; AMC Theatres; American Red Cross of Santa Monica; Applause; Aquarium of the Pacific; Bally Total Fitness; Bed Bath & Beyond; Ben & Jerry’s of California; Bethany House Publishers; Big Idea Productions; Carl’s Jr.; Coco’s Restaurants; Crabtree & Evelyn; Dupar’s Restaurant; El Pollo Loco, Inc.; Food 4 Less; Gap, Inc.; Gelson’s; General Cinema; HarperCollins Publishers; Health Tex; i Maternity; Imperial Toys; Johnson and Johnson; KCMG L.A. 92.3; Laemmle Theatres; Loews Theaters; Los Angeles Dodgers; m. fredric kids; Mann Theatres; March of Dimes; Mark Taper Forum/Ahmanson Theatre; Marshall’s; Mattel, Inc./Toy Donation Program; Motherwear; Munchkin, Inc.; Naissance; NANO Products; Natural History Museum of LA County Foundation; Old Navy; Paramount Pictures; Pizza Hut; Ralphs Groceries; Random House, Inc.; Rhino Entertainment; Road Champs; Ross Dress for Less; Sebastian International; See’s Candy; Shelter Partnerships; St. Mel Catholic Church; Starbucks; Stitches from the Heart; Taco Bell Corp.; The C. Everett Koop Institute at Dartmouth; Tommy’s Famous Hamburgers; Tower Records; Trader Joe’s; Universal Studios—Hollywood; Valley Beth Shalom; Von’s; West Valley Jewish Community Center; Whispering Lakes Golf Course; Will Rogers Foundation; and Woodland Hills Community Church.

Footnotes

Portions of these data were presented to the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, San Juan, Puerto Rico, June 1996, and Scottsdale, Arizona, June 2001. Preparation of this article was supported by Grant 1 R01 DA13638 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- Amass, L. (1997). Financing voucher programs for pregnant substance abusers through community donations. In L. S. Harris (Ed.), Problems of drug dependence 1996: Proceedings of the 58th annual scientific meeting (NIDA Research Monograph 174, p. 60). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [PubMed]

- Amass L, Bickel WK, Crean J, Higgins ST. Preferences for clinic privileges, retail items, and social activities in an outpatient buprenorphine treatment program. Journal on Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;13:49–55. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)02060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amass, L., Ennis, E., Mikulich, S. K., & Kamien, J. B. (1998). Using fee rebates to reinforce abstinence and counseling attendance in cocaine abusers. In L. S. Harris (Ed.), Problems of drug dependence 1997: Proceedings of the 59th annual scientific meeting (NIDA Research Monograph 178, p. 99). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [PubMed]

- Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML, Griffiths RR, Liebson IA. Contingency management approaches to drug self-administration and drug abuse: Efficacy and limitations. Addictive Behaviors. 1981;6:241–252. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(81)90022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape MA, Silverman K, Stitzer ML. Survey assessment of methadone treatment services as reinforcers. American Journal of Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1998;24:1–16. doi: 10.3109/00952999809001695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donatelle RJ, Prows SL, Champeau D, Hudson D. Randomised controlled trial using social support, financial incentives for high risk pregnant smokers: Significant Other Supported (SOS) program. Tobacco Control. 2000;9(Suppl 3):iii67–iii69. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, L. (1984). The ten lost commandments of fundraising: Davis and Henderson’s bicentennial [Booklet]. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Council for Business and the Arts in Canada.

- Higgins ST, Alessi SM, Dantona RL. Voucher-based incentives. A substance abuse treatment innovation. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:887–910. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg F, Donham R, Badger G. Incentives improve outcome in out-patient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Petry NM. Contingency management, incentives for sobriety. Alcohol Research Health. 1999;23:122–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, S. T., & Silverman, K. (1999). Motivating behavior change among illicit-drug abusers. Research on contingency management interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Iguchi MY, Belding MA, Morral AR, Lamb RJ, Husband SD. Reinforcing operants other than abstinence in drug abuse treatment: An effective alternative for reducing drug use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:421– 428. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi MY, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Contingency management in methadone maintenance: Effects of reinforcing and aversive consequences on illicit poly-drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1988;22:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(88)90030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, Haug NA, Stitzer ML, Svikis DS. Improving treatment outcomes for pregnant drug-dependent women using low-magnitude voucher incentives. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, Stitzer MS, Griffiths RR. Evaluating the reinforcement value of clinic-based privileges through a multiple choice procedure. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, K. C., Amass, L., & McLellan, A. T. (1999). Disseminating contingency-management research to drug abuse treatment practitioners. In S. T. Higgins & K. Silverman (Eds.), Motivating behavior change among illicit-drug abusers: Research on contingency management interventions (pp. 327–344). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Milby JB, Garrett C, English C, Fritschi O, Clarke C. Take-home methadone: Contingency effects on drug-seeking and productivity of narcotic addicts. Addictive Behaviors. 1978;3(Suppl 4):215–220. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B. Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine- and opioid-abusing methadone patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:398– 405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes and they will come: Contingency management for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Finocche C. Contingency management in group treatment: A demonstration project in an HIV drop-in center. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;21:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Petrakis I, Trevisan L, Wiredu L, Boutros N, Martin B, et al. Contingency management interventions: From research to practice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;20:33– 44. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Simcic F. Recent advances in the dissemination of contingency management techniques: Clinical and research perspectives. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:81– 86. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B, Kamien JB, Ishisaka A, Amass L. A tale of two cities: Financing another voucher program for substance abusers through community donations [Abstract] Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63:S133. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Rhoades H, Grabowski J. A menu of potential reinforcers in a methadone maintenance program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1994;11:425– 431. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner, A., Tucker, D. E., Roberts, L. J., & Eckman, T. A. (1999). Disability income, cocaine use, and contingency management among patients with cocaine dependence and schizophrenia. In S. T. Higgins & K. Silverman (Eds.), Motivating behavior change among illicit-drug abusers: Research on contingency management interventions (pp. 95–121). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Silverman K, Chutaupe MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: Effects of reinforcer magnitude. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s002130051098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Svikis D, Robles E, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A reinforcement-based Therapeutic Workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: Six-month abstinence outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:14–23. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.9.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Svikis D, Wong CJ, Hampton J, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A reinforcement-based Therapeutic Workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: Three-year abstinence outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;10:228–240. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, K., Wong, C. J., Grabinski, M. J., Hampton, J., Sylvest, C. E., Dillon, E. M., et al. (in press). A web-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug addiction and chronic unemployment. Behavioral Modification. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sindelar JL, Fiellin DA. Innovations in treatment for drug abuse: Solutions to a public health problem. Annual Review in Public Health. 2001;22:249–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. Contingency management in a methadone maintenance program: Availability of reinforcers. International Journal of Addiction. 1978;13:737–746. doi: 10.3109/10826087809039299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. Contingent payment for carbon monoxide reduction: Effects of pay amount. Behavioral Therapy. 1983;14:647– 656. [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. Contingent payment for carbon monoxide reduction: Within-subject effects of pay amount. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis. 1984;17:477– 483. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1984.17-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer, M. L., Bigelow, G. E., & Iguchi, M. Y. (1993). Behavioral interventions in the methadone clinic: Contingent methadone take-home incentives. In L. S. Harris (Ed.), Problems of drug dependence 1992: Proceedings of the 54th annual scientific meeting (NIDA Research Monograph 132, NIH Publication No. 93-3505, p. 66) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Reducing drug use among methadone maintenance clients: Contingent reinforcement for morphine-free urines. Addictive Behaviors. 1980;5:333–340. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(80)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Iguchi MY, Felch LJ. Contingent take-home incentive: Effects on drug use of methadone maintenance patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:927–934. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svikis DS, Lee J, Haug N, Stitzer M. Attendance incentives for outpatient treatment: Effects in methadone- and non-methadone-maintained pregnant drug dependent women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;48:33– 41. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman, K. (1993). Face to face. How to get BIGGER donations from very generous people. Voluntary Action Directorate, Multiculturalism and Citizenship, Department of Canadian Heritage, Ottawa, Canada.

- Yen S. Availability of activity reinforcers in a drug abuse clinic: A preliminary report. Psychology Report. 1974;34:1021–1022. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1974.34.3.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]