Abstract

Recent advancements in neuroinflammation research have significantly enhanced our understanding of its pivotal role in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, leveraging its unique ability to quantify biological processes in vivo non-invasively, has emerged as a transformative tool for investigating neuroimmune mechanisms. The 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), a biomarker of activated microglia and astrocytes during neuroinflammation, enables PET-based visualization of neuroinflammatory activity, offering novel insights into the neurobiological underpinnings of psychiatric conditions. This review synthesizes recent TSPO PET imaging findings across major psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, and psychosis. We critically evaluate how TSPO PET elucidates neuroinflammatory signatures linked to disease progression, treatment responses, and therapeutic stratification. Furthermore, we explore the translational potential of anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., celecoxib and minocycline) and TSPO-targeted ligands (e.g., etifoxine and XBD173) in modulating neurosteroid synthesis and neuroimmune interactions. By bridging methodological innovations with clinical applications, this review underscores the promise of TSPO PET in advancing diagnostic precision, personalized treatment strategies, and mechanistic insights into neuroinflammation-driven psychiatric pathologies. Challenges such as genetic polymorphisms (e.g., rs6971), partial volume effects (PVEs), and quantification biases are discussed to guide future research directions.

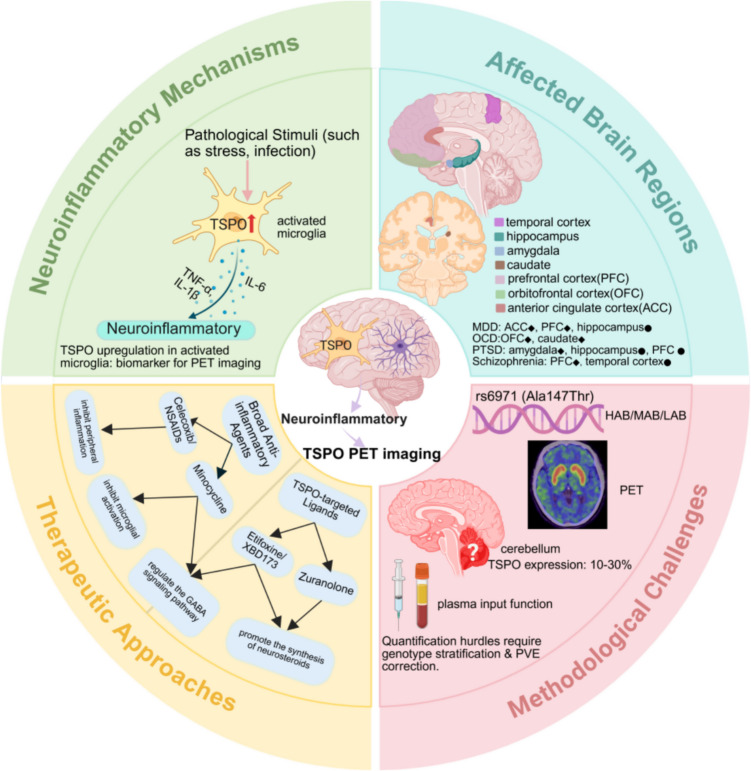

Graphical Abstract

Schematic overview of TSPO PET imaging in psychiatric disorders. (Created with BioRender.com). black diamond, consistent TSPO elevation region; black circle, conflicting findings. Abbreviations: ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; PFC, prefrontal cortex; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; TSPO, translocator protein; PET, positron emission tomography; MDD, major depressive disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; PVE, partial volume effect; HAB, high-affinity binder; MAB, mixed-affinity binder; LAB, low-affinity binder

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12035-025-05177-w.

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, Major depressive disorder, Obsessive–compulsive disorder, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Schizophrenia, Positron emission tomography

Introduction

Neuroinflammation, characterized by the activation of microglia and astrocyte cells and disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), has emerged as a critical pathophysiological mechanism underlying psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, and psychosis [1, 2]. Microglia, which are immune cells that reside in the central nervous system (CNS), undergo a transition from a quiescent “ramified state” to an activated “amoeboid shape” morphology in response to pathological stimuli. This process results in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [3–5] or growth factors and anti-inflammatory mediators. Similarly, astrocytes exhibit dynamic functional changes during neuroinflammation, interacting with microglia to regulate synaptic transmission, BBB integrity, and neurotrophic support [6, 7].

The BBB, composed of endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytic end-feet, serves as a selective barrier protecting the brain from peripheral immune infiltration [8]. Chronic stress and neuroinflammatory mediators, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and TNF-α, compromise BBB integrity, allowing inflammatory factors to infiltrate the CNS and perpetuate neuropsychiatric symptoms [9–11]. For instance, BBB disruption in the prefrontal cortex correlates with depressive-like behaviors in preclinical models and symptom severity in bipolar disorder patients [9, 12]. This bidirectional relationship between BBB dysfunction and neuroinflammation underscores its role in psychiatric pathophysiology [13]. During neuroinflammation, the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO) is upregulated in activated microglia and astrocytes, and it is a critical biomarker for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging [14, 15]. TSPO PET enables in vivo quantification of neuroinflammatory activity, offering insights into disease diagnosis and therapeutic responses [16, 17]. This review synthesizes TSPO PET findings across psychiatric disorders, evaluates the anti-inflammatory therapies of TSPO ligands (e.g., etifoxine) and other drugs, including celecoxib and minocycline in psychiatric disorders mentioned above, and highlights future directions for targeting neuroinflammation in mental health. The link between psychiatric disorders and neuroinflammation is explained in Fig. 1 (taking MDD as an example).

Fig. 1.

The mechanisms of neuroinflammation in MDD (created with BioRender.com). With a focus on the signaling pathways that support and exacerbate the inflammatory processes. When the body is subjected to stimuli such as stress, infection, or illness, there is an elevation of peripheral inflammatory factors, cytokines, and chemokines in the bloodstream, including TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6. This results in astrocyte dysfunction and disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), allowing these factors to infiltrate the brain parenchyma. Resting microglia are activated into a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype; concurrently, interactions between astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and M1 microglia lead to the activation of reactive astrocytes into a pro-inflammatory A1 phenotype. The M1 and A1 phenotypes release distinct cytokines that contribute to neurodegeneration, ultimately resulting in neuronal damage. Damaged neurons and glial cells release high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) closely linked to the onset of central nervous system inflammation. HMGB1 initiates multiple inflammatory response pathways by binding to Toll-like receptors (TLR2, TLR4) and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), culminating in the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and the induction of neuroinflammation, which can lead to the development of depression

PET Imaging in Neuroinflammation

Advantages of PET Imaging

PET is a non-invasive imaging technology capable of quantifying biomolecular metabolism in living organisms. Its unique capacity for absolute quantification without altering target properties makes it ideal for tracer studies. Notably, PET ligands operate at trace concentrations and can detect protein targets below 10⁻⁸ M—a sensitivity unmatched by other techniques [14]. This exceptional precision positions PET as a powerful tool for quantifying neuroinflammation.

Definition and Function of TSPO

TSPO, an 18 kDa protein located on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), was initially referred to as the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR). TSPO is widely distributed across most peripheral organs, with particularly high expression in steroidogenic tissues.

TSPO forms a receptor complex with the surrounding voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) and the adenine nucleotide transporter (ANT), thereby contributing to various physiological functions within the body. This TSPO receptor complex participates in and constitutes the channels through which molecules or ions cross the mitochondrial membrane—the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP). The widespread distribution of TSPO in mitochondria suggests its involvement in regulating mitochondrial functions, including cholesterol transport, the synthesis of steroid hormones, porphyrin transport, heme synthesis, apoptosis, cell proliferation, and transport of ions and metabolites [15, 18]. Its most crucial function, however, appears to be in steroidogenesis, where the rate-limiting step involves TSPO-mediated transport of cholesterol from the cytoplasm to the mitochondrial matrix [15, 19]. Within the mitochondrial matrix, cholesterol is metabolized into the first steroid: pregnenolone [20], which subsequently diffuses into the endoplasmic reticulum and cytoplasm, undergoing various metabolic pathways to be converted into other steroid hormones and neurosteroids (NS) [21]. Although the precise role and function of TSPO in steroidogenesis have been challenged by TSPO knockout (KO) mouse models [22, 23], substantial evidence indicates that TSPO plays a significant role in steroid formation, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. This evidence includes studies utilizing homologous recombination to knock out TSPO, using TSPO antisense vectors [24], oligonucleotides (ODNs) [25], or silencing ribonucleic acids (RNAs) to knock down TSPO [26–28].

Secondly, TSPO is thought to play a significant role in opening the mitochondrial transmembrane potential, which leads to changes in the proton electrochemical gradient and can result in mitochondrial apoptosis. Moreover, TSPO may be involved in the regulation of ROS production and programmed cell death [29], possibly related to NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2), which can modulate ROS levels in mitochondria. Alternatively, TSPO may regulate ROS production through its expression ratio with VDAC1. Subsequently, the production of ROS leads to an accumulation of defective mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction [30]. This dysfunction is potentially associated with several neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [31–33], as well as various psychiatric disorders and stress-related conditions, including bipolar disorder and MDD [34, 35].

In recent decades, TSPO has been utilized as a molecular biomarker for activated microglia in animal models under various neuroinflammatory conditions. With advancements in technology, TSPO has also been applied in human studies. A substantial amount of research has confirmed that in pathological conditions of the CNS, such as persistent peripheral inflammation, epilepsy, cerebral ischemia, and MDD, neuroinflammatory responses are consistently present at the sites of neural injury and surrounding areas [36–38]. During these conditions, microglial activation is particularly associated with a significant increase in TSPO expression. However, it has other sources as well. For instance, Lavisse et al. demonstrated that reactive astrocytes can also exhibit overexpression of TSPO in a selective astrocyte activation model in the rat striatum [39].

Additionally, increased neuronal activity [40] and the migration of endothelial cells [41] or peripheral myeloid cells to the brain can all promote TSPO expression. Thus, TSPO may serve as a potential biomarker for monitoring neuroinflammatory responses in neurological diseases and psychiatric disorders such as MDD [42]. This suggests that TSPO is involved in regulating the activation processes of both microglia and astrocytes and may represent a potential therapeutic target for modulating their functional states. Consequently, TSPO PET imaging can enhance the understanding of neuroinflammation’s role in CNS diseases through selective ligand matching and can evaluate the efficacy of novel anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategies. As demonstrated by Attwell et al., TSPO distribution volume in PET imaging can predict the therapeutic effectiveness of celecoxib, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, in patients with MDD [17].

TSPO PET Imaging

TSPO PET imaging has emerged as the predominant modality for non-invasive quantification of neuroinflammation in vivo (Table 1). This section outlines the evolution of TSPO radioligands and their current applications in preclinical and clinical research.

Table 1.

Characteristics included in the TSPO PET imaging studies

| Illness category | Study | Patient diagnosis | Radioligand | Patients | Healthy controls | %HAB ratio (P/C) | Extracted brain regions | Effect size (Cohens d/η2) | Outcome | Conclusion | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % female | mean age | BMI | % HAB | n | % female HC | mean age | BMI | %HAB | |||||||||

| MDD | Hannestad 2013 | Major depressive disorder | 11C-PBR28 | 10 | 50 | 37 | 25.4 | 66.7 | 10 | 60 | 39 | 26.7 | 70 | 0.95 | GM; thalamus | d = 0.37 (thalamus) ~ 0.72 (caudate) | VT | → |

| Setiawan 2015 | Major depressive disorder | 18F-FEPPA | 20 | 60 | 34 | 23.4 | 75 | 20 | 55 | 33.6 | 24.8 | 70 | 1.07 | GM; thalamus; HIPP; ACC | d* = 1.11 (ACC), 1.17 (thalamus) | VT | ↑ | |

| Su 2016 | Major depressive disorder | 11C-PK11195 | 5 | 60 | 73.2 | / | / | 13 | 61.4 | 68 | / | / | / | ACC; HIPP | d* = 1.71 (ACC), 1.23 (HIPP) | BPND | ↑ | |

| Holmes 2018 | Major depressive disorder | 11C-PK11195 | 14 | 50 | 30 | 23 | / | 13 | 46.2 | 33 | 23 | / | / | ACC; PFC; INS | d = 0.95 (ACC), 0.38 (PFC), 0.29 (INS) | BPND | ↑ | |

| Richards 2018 | Major depressive disorder | 18F-FEPPA | 28 | 39.3 | 39.2 | 27.8 | 67.86 | 20 | 50 | 31.6 | 26.01 | 60 | 1.13 | ACC; sgPFC | d = 0.60 (ACC), 0.64 (sgPFC) | VT | ↑ | |

| Li 2018a | Major depressive disorder | 18F-FEPPA | 50 | 50 | 28.7 | 24.5 | 100 | 30 | 50 | 27.4 | 24.3 | 100 | 1 | GM;PFC; HIPP | η2 = 0.71 | VT | ↑ | |

| Li 2018b | Major depressive disorder | 18F-FEPPA | 40 | 50 | 26.8 | 24.45 | 100 | 20 | 50 | 26.8 | 24.9 | 100 | 1 | GM; WM; HIPP | η2 = 0.19 | VT | ↑ | |

| Setiawan 2018 | Major depressive disorder | 18F-FEPPA | 50 | 0.62 | 34.45 | 24.6 | 74 | 30 | 46.7 | 33.2 | 24.9 | 73 | 1.01 | GM; thalamus; HIPP; ACC; PFC; INS | d* = 0.83 (PFC), 1.03 (ACC), 1.03 (INS) | VT | ↑ | |

| Schubert 2021 | Major depressive disorder | 11C-PK11195 | 51 | 85.2 | 36.2 | 27.2 | / | 25 | 26 | 37.3 | 24.2 | / | / | ACC; PFC; INS | η2 = 0.09, d = 0.49 (ACC) | BPND | ↑ | |

| Joo 2021 | Major depressive disorder | 11C-PK11195 | 30 | 56.7 | 24.6 | 23.6 | / | 23 | 43.5 | 24.5 | 23.6 | / | / | ACC; PFC; INS; PCC; HIPP; TC | d = 0.713 (Lt. ACC), 0.629 (Rt. PCC), 0.494 (Lt. PFC), 0.344 (Lt. INS), 0.373(Rt. HIPP) | BPND | ↑ | |

| OCD | Attwells 2017 | Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 18F-FEPPA | 20 | 55 | 27.4 | 22.8 | 65 | 20 | 40 | 27.6 | 24.4 | 65 | 1 | DC; OC; thalamus; VS; DP; ACC | / | VT | ↑ |

| PTSD | Bhatt 2020 | Posttraumatic stress disorder | 11C-PBR28 | 23 | 43.5 | 38 | 27.8 | 78.3 | 26 | 30.8 | 32 | 28.3 | 65.4 | 1.2 | AMYG; ACC; HIPP; INS; vmPFC | / | VT | ↓ |

| Deri 2021 | Posttraumatic stress disorder | 18F-FEPPA | 20 | 10 | 56 | 30.66 | 45 | ※ | / | GM; HIPP | d = 0.72 (HIPP), 0.64 (FC) | VT | ↑** | |||||

| Watling 2023 | Posttraumatic stress disorder | 18F-FEPPA | 17 | 53 | 44 | 26.5 | 47.1 | 22 | 53 | 34.6 | 24.8 | 54.5 | 0.86 | AMYG; HIPP; INS; PFC; Striatum; ACC | d = 0.46 (AMYG) | VT | ↓ | |

| Bonomi 2024 | Posttraumatic stress disorder | 11C-PBR28 | 15 | 40 | 32.2 | / | 93.3 | 15 | 26.7 | 30.1 | / | 53.3 | 1.75 | AMYG; HIPP; INS; vmPFC | d = 0.89 (prefrontal-limbic circuit), 0.88 (AMYG), 1.04 (HIPP), 0.63 (INS), 0.79 (vmPFC) | VT | ↓ | |

| SZ | Banati 2009 | Schizophrenia | 11C-PK11195 | 16 | 37.5 | 39.4 | / | / | 8 | 37.5 | 37.6 | / | / | / | Whole brain | / | PCA | ↑*** |

| Van Berckel 2008 | Schizophrenia | 11C-PK11195 | 10 | 10 | 24.2 | / | / | 10 | 30 | 23.4 | / | / | / | GM | d* = 0.87 (GM) | BPND | ↑ | |

| Doorduin 2009 | schizophrenia | 11C-PK11195 | 7 | 14.3 | 31.2 | / | / | 8 | 37.5 | 26.88 | / | / | / | GM;thalamus; HIPP | d* = 1.94 (HIPP) | BPND | ↑ | |

| Takano 2010 | Chronic schizophrenia | 11C-DAA1106 | 14 | 42.9 | 43.9 | / | / | 14 | 35.7 | 425 | / | / | / | GM | / | BPND | → | |

| Bloomfield 2016 | Schizophrenia | 11C-PBR28 | 14 | 21.43 | 47 | / | 92.86 | 14 | 21.43 | 46.21 | / | 100 | 0.93 | GM; TC | d > 1.7 (GM) | DVR, VT | ↑, → | |

| Bloomfield 2016 | Ultra-high risk for psychosis | 11C-PBR28 | 14 | 50 | 24.29 | / | 50 | 14 | 28.57 | 28.14 | / | 71.43 | 0.7 | GM; TC | d > 1.2 (GM) | DVR, VT | ↑, → | |

| Kenk 2015 | Schizophrenia | 18F-FEPPA | 16 | 37.5 | 42.5 | / | 62.5 | 27 | 63 | 43.5 | / | 70.4 | 0.89 | GM; HIPP; PFC; ACC | / | VT | → | |

| Coughlin 2016 | Schizophrenia | 11C-DPA713 | 12 | 21 | 24.1 | 27.6 | 66.7 | 14 | 44 | 24.9 | 24.9 | 64.3 | 1.04 | GM;thalamus; HIPP | / | VT | → | |

| Holmes 2016 | Schizophrenia (antipsychotic-free) | 11C-PK11195 | 8 | 50 | 27 | 27 | / | 16 | 31.3 | 33 | 24 | / | / | GM; ACC | / | BPND | → | |

| Holmes 2016 | Schizophrenia (medicated) | 11C-PK11195 | 8 | 12.5 | 38 | 30 | / | 16 | 31.3 | 33 | 24 | / | / | GM; ACC | / | BPND | ↑ | |

| van der Doef 2016 | Schizophrenia | 11C-PK11195 | 19 | 18.75 | 26 | / | / | 17 | 21.4 | 26 | / | / | / | GM; thalamus | d* = 0.33 (GM) | BPND | → | |

| Collste 2017 | First episode psychosis | 11C-PBR28 | 16 | 31.25 | 28.5 | 22.9 | 50 | 16 | 56.25 | 26.4 | 21.9 | 56.25 | 0.89 | GM; HIPP | η2 = 0.18 (GM), 0.16 (HIPP) | VT | ↓ | |

| Di Biase 2017 | Ultra-high risk for psychosis | 11C-PK11195 | 10 | 40 | 20.7 | 22 | / | 15 | 13.3 | 21.7 | 24.3 | / | / | GM; thalamus; ACC | d = − 0.23 (temporal) ~ 0.35 (ACC) | BPND | → | |

| Di Biase 2017 | Chronic schizophrenia | 11C-PK11195 | 15 | 33.3 | 35.2 | 27.6 | / | 12 | 25 | 36.3 | 25.5 | / | / | GM; thalamus; ACC | d = − 0.26 (DF) ~ 0.17 (thalamus) | BPND | → | |

| Di Biase 2017 | Recent-onset schizophrenia | 11C-PK11195 | 18 | 11.1 | 20.6 | 27.6 | / | 15 | 13.3 | 21.7 | 24.3 | / | / | GM;thalamus; ACC | d = 0.04 (temporal) ~ 0.33 (ACC) | BPND | → | |

| Hafizi 2017 | First episode psychosis | 18F-FEPPA | 19 | 36.8 | 27.53 | / | 73.7 | 20 | 55 | 27.75 | / | 70 | 1.05 | GM; HIPP | η2 = 0.05 (HIPP), 0.01 (PFC, whole brain) | VT | → | |

| Hafizi 2017b | Ultra-high risk for psychosis | 18F-FEPPA | 24 | 56.17 | 21.21 | / | 75 | 23 | 60.87 | 23.04 | / | 82.61 | 0.91 | GM; HIPP | / | VT | → | |

| Hafizi 2018 | Ultra-high risk for psychosis | 18F-FEPPA | 27 | 48.15 | 20.3 | / | 55.56 | 21 | 52.38 | 22.86 | / | 76.19 | 0.73 | PFC | / | VT | → | |

| Ottoy 2018 | Schizophrenia during acute psychotic episode | 18F-PBR111 | 11 | 0 | 32 | / | 57.14 | 17 | 0 | 28 | / | 41.18 | 1.39 | GM; thalamus; HIPP; ACC | η2 = 0.007 (TC), 0.059 (HIPP), 0.009 (PFC), 0.006 (GM) | VT | ↑ | |

| De Picker 2019 | Schizophrenia during acute psychotic episode | 18F-PBR111 | 14 | 0 | 32.2 | 25.5 | 57.1 | 17 | 0 | 27.2 | 23.3 | 41.2 | 1.39 | GM; thalamus; HIPP; ACC | / | VT | ↑ | |

| Laurikainen 2020 | Schizophrenia | 11C-PBR28 | 13 | 46.15 | 24.8 | 23.5 | 61.54 | 15 | 66.67 | 29.7 | 24 | 60 | 1.03 | GM; thalamus; HIPP; ACC | d = 0.94 | VT | ↓ | |

| Conen 2021 | Recent-onset schizophrenia | 11C-PK11195 | 20 | 30 | 24.2 | 24.7 | / | 10 | 20 | 25.5 | 26.5 | / | / | GM; thalamus; ACC | d = 0.35 (thalamus), 0.51 (ACC), 0.41 (PFC) | BPND | → | |

| Conen 2021 | Chronic schizophrenia | 11C-PK11195 | 21 | 38 | 46.3 | 29.5 | / | 11 | 36 | 46.7 | 26.6 | / | / | GM; thalamus; ACC | d = 0.74 (thalamus), 0.03 (ACC), 0.92 (PFC) | BPND | → | |

MDD: major depressive disorder, OCD: obsessive–compulsive disorder, PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder, SZ: schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, BMI: body mass index, VT: total volume of distribution, BPND: binding potential, PCA: principal component analysis, P: patients, C: controls, Lt: left, Rt: right, GM: gray matter, WM: white matter, HIPP: hippocampus, ACC: anterior cingulate cortex, PFC: pre-frontal cortex, INS: insula, sgPFC: subgenual prefrontal cortex, TC: temporal cortex, PCC: posterior cingulate cortex, FC: frontal cortex, DC: dorsal caudate, OC: orbitofrontal cortex, VS: ventral striatum, DF: dorsal frontal, DP: dorsal putamen, AMYG: amygdala, vmPFC: ventromedial prefrontal cortex, HAB: high-affinity binder, MAB: medium-affinity binder, LAB: low-affinity binder

Effect sizes: Cohen’s d < 0.5 is a small effect, ≥ 0.5 is a medium effect, ≥ 0.8 is a large effect; η2 < 0.01 is a small effect, ≥ 0.06 is a medium effect, ≥ 0.14 is a large effect, d*, not directly mentioned in the original text but calculated from the data provided. →, no difference; ↑, elevate; ↓, decline. (compared to the control group)

Conclusion*: Elevate, decrease, or no difference in outcome indicators in the patient group compared to the control group

↑**: No control group, Higher TSPO VT among World Trade Center responders correlated with PTSD severity

↑***: Conclusions were not drawn in terms of outcome indicators, but rather elevated TSPO BPND in the patient group compared to the control group

※: No control group, /: missing

TSPO PET imaging has evolved through three generations of ligand innovation: the first generation ligands (e.g., [11C]-(R)-PK11195) were validated in neuroinflammatory models but limited by low brain permeability, high non-specific binding, and a short half-life (20 minutes) [43, 44]; the second generation ligands (e.g., [11C]PBR28 and [18F]DPA-714) improved signal-to-noise ratio (2–3–fold higher than PK11195) and prolonged half-life enable multi-center studies [45–47] and are widely used in AD, multiple sclerosis (MS), and psychiatric disorders [17, 48]; third-generation ligands (e.g., [11C]ER176 and [18F]GE180) reduced sensitivity to rs6971 polymorphism and improved binding specificity, achieving ≥ 90% target occupancy in high-affinity binders (HABs), and preclinical studies demonstrate superior detection of subtle neuroinflammation in chronic stress models [49, 50]. Distribution volume (VT), binding potential (BPND), and dose–response modeling can be employed to quantitatively correlate TSPO density with neuroinflammatory markers or clinical symptoms at the quantitative level of analysis. This methodology has demonstrated a variety of applications in neuropsychiatric research: clinical evidence indicates that the duration of untreated depression is positively correlated with elevated prefrontal cortical TSPO VT, indicating that it has the potential to serve as a neuroinflammatory staging marker [51]. Treatment monitoring studies have shown that celecoxib significantly reduces the TSPO binding levels in patients with MDD, and this change is synchronized with clinical symptom improvement [17]. The AD model has confirmed that TSPO PET can detect microglia activation before amyloid plaque formation, providing a critical window for early intervention in neurodegenerative pathologies [50].

Methodological Challenges in TSPO PET Imaging

Despite its potential, TSPO PET imaging faces significant methodological hurdles that complicate data interpretation and cross-study comparisons. Below, we dissect five key challenges.

Genetic Polymorphism (rs6971) and Ligand Affinity Heterogeneity

The rs6971 polymorphism (Ala147Thr) in the TSPO gene critically impacts the binding affinity of early radioligands (e.g., [11C]PBR28), stratifying individuals into HAB, mixed-affinity binders (MAB), or low-affinity binders (LAB). LAB subjects exhibit up to 90% lower BPND compared to HABs, introducing confounding variability in group-level analyses [49, 52]. Although third-generation ligands reduce genotype sensitivity, residual affinity differences persist. For instance, [18F]GE180 shows 20–30% lower VT in LABs [49], necessitating genotype stratification even with advanced tracers. Failure to account for rs6971 status may obscure true neuroinflammatory signals or generate false positives in mixed cohorts.

Partial Volume Effects and Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio

PVEs—caused by PET’s limited spatial resolution (typically 4–6 mm)—artificially reduce observed binding in small structures (e.g., hippocampus) and inflate noise in low-TSPO regions. PVEs are exacerbated in psychiatric disorders where neuroinflammation may be subtle and diffuse. For example, uncorrected PVE can underestimate TSPO VT in the anterior cingulate cortex by 15–25% [53]. While correction algorithms (e.g., Müller-Gärtner method) mitigate these errors, they require high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) co-registration and assumptions about tissue boundaries, which may not hold in atrophic brains.

Lack of a Valid Reference Region

The absence of a TSPO-free reference region complicates quantification. Cerebellar gray matter—often used as a pseudo-reference—expresses TSPO at 10–30% of neuroinflammatory levels [16], and its binding varies with aging, neurodegeneration, and systemic inflammation—alternative approaches (e.g., global mean normalization) risk conflating disease-specific signals with global neuroinflammatory shifts. Supervised clustering methods to identify “low-binding” voxels show promise but lack biological validation [50].

Plasma Input Function and Quantification Biases

Accurate quantification of TSPO PET signals relies heavily on precise measurement of the plasma input function. This parameter is critical for calculating VT and non-displaceable BPND. VT reflects total ligand binding (specific + non-specific), whereas non-displaceable BPND specifically quantifies target-specific binding. Errors in plasma input function determination (e.g., incomplete metabolite correction or variability in plasma protein binding) can systematically bias outcome measures. For instance, overestimation of free plasma ligand concentration may lead to underestimation of VT, falsely implying reduced neuroinflammation. These challenges are exacerbated in psychiatric cohorts, where subtle neuroinflammatory changes demand high precision. Recent advances in population-based input functions and image-derived input methods aim to mitigate these issues, though validation in diverse clinical populations remains ongoing [16].

Kinetic Modeling in Low-Binding Tissues

In regions with minimal TSPO expression (e.g., white matter), traditional two-tissue compartment models struggle to separate specific binding from noise due to poor identifiability. Simplified models (e.g., Logan graphical analysis) improve robustness but sacrifice physiological interpretability. Hybrid methods incorporating MRI-derived vascular input functions or spectral analysis may enhance precision, yet their utility in psychiatric populations remains unproven [16, 53].

TSPO PET Imagine and Mental Illness

TSPO PET Imaging and Major Depressive Disorder

MDD is a class of mood disorders characterized by significant and persistent depressed mood, cognitive impairment, reduced motivation, and physical symptoms. It is associated with high prevalence, substantial disease burden, and high disability rates. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 5% of the global population suffers from depression, and it is projected that by the end of 2030, depression will become one of the three leading causes of the global burden of disease [54]. The pathogenesis of depression remains a focal point of research in the medical field, with complex pathophysiological mechanisms including the monoamine hypothesis, alterations in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory hypothesis, the stress hypothesis, plasticity and neurogenesis, changes in brain structure and function, as well as genetic, environmental, and epigenetic factors (gene-environment interactions). Among these, the immune-inflammatory hypothesis has emerged as a significant area of study in the pathophysiology of MDD, with increasing evidence supporting the role of neuroinflammation in MDD.

Animal studies have shown that stressors (chronic stress, etc.) can promote neuroinflammation [55]. PET studies of MDD typically focus on brain regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), prefrontal cortex (PFC), and insula. Notably, most PET studies have reported that, compared to healthy controls, patients with MDD show elevated binding of TSPO and its ligands during a major depressive episode (MDE) [51, 56–59]. Furthermore, untreated patients exhibit a more pronounced increase in TSPO total VT in the ACC compared to those receiving antidepressant treatment [56, 57], and the longer the duration of untreated MDD, the higher the TSPO VT values in the affected brain regions [51]. In addition, another study shows that patients with the first diagnosis of MDD demonstrate a reduction in TSPO VT in these regions during cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [58], suggesting that the improvement in depressive symptoms is associated with the decline in TSPO levels. Most of these studies utilized second-generation TSPO radiotracers, specifically [18F]FEPPA and [11C]PBR28, ranked by frequency of use. Despite four studies using a first-generation radioligand [11C]PK11195 to measure the non-displaceable BPND [60–63], the findings are consistent with those of the aforementioned studies. Furthermore, a meta-analysis found that both autopsy and PET studies have confirmed increased TSPO levels in MDD [64]. Notably, however, a study measuring TSPO VT with [11C]PBR28 found no significant difference in TSPO VT values between the two groups [65], potentially due to a small sample size, the severity of depressive symptoms varies significantly, and ligand polymorphism.

Furthermore, Holmes et al. [60] found no significant correlation between BPND and the severity of depressive symptoms in their patient group. However, Setiawan et al. [57] reported a significant positive correlation between TSPO VT in the ACC and scores on the 17-Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) among patients. That is, greater severity of MDD is associated with higher TSPO density in the ACC. In fact, the discrepancy in findings may arise because the VT parameter reflects the ratio of radioactive ligand concentration in a specific tissue region to that in plasma, encompassing both specific and non-specific binding. Nevertheless, BPND represents the ratio of specifically bound to non-specifically bound radioligands [53]. Despite these differences, a meta-analysis by Benjamin et al. [66] revealed that factors such as HDRS scores, age, body mass index (BMI), percentage of untreated patients, gender distribution, choice of radioligand, and outcome measurement selection showed no significant impact on the PET findings in patients with MDD.

Taken together, the quantitative assessment of MDD using TSPO PET imaging has emerged as a promising neuroimaging technique. The relationship between neuroinflammation and MDD is complex. However, it is not necessarily the case that more severe depression correlates with greater neuroinflammation. Antidepressant treatments have been shown to reduce TSPO VT and alleviate depressive symptoms, suggesting that such treatments may mitigate the neuroinflammatory response in patients. This also indirectly indicates a close association between neuroinflammation and MDD.

However, due to the complex pathophysiological mechanisms of MDD, the efficacy of its treatment ranges only from 30 to 60% [34]. In this case, this necessitates the exploration of new therapeutic approaches to achieve better treatment outcomes. The close relationship between MDD and neuroinflammation suggests that neuroinflammation may serve as a potential therapeutic target for treating MDD. This can be approached in two ways: one involves using anti-inflammatory medications, such as celecoxib, to address neuroinflammation and thereby alleviate depression, while the other involves utilizing TSPO-specific ligands to synthesize NS through interactions with gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABAA), exerting anxiolytic and antidepressant effects.

While anti-inflammatory agents such as celecoxib and minocycline have shown promise as adjunctive treatments for MDD, the strength of evidence varies across studies. A meta-analysis of 44 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated that celecoxib (400 mg/day for 6 weeks) significantly improved depressive symptoms compared to placebo [67]. However, limitations include heterogeneous patient populations, short trial durations (typically ≤ 12 weeks), and potential confounding effects of concurrent antidepressant use. For instance, only 30% of included studies controlled for baseline inflammatory biomarkers, raising questions about whether observed benefits are specific to patients with elevated inflammation. Similarly, trials of minocycline often involve small sample sizes [68] and lack long-term follow-up data, limiting conclusions about sustained efficacy.

Notably, TSPO-targeted therapies differ mechanistically from broad anti-inflammatory agents. TSPO ligands directly modulate neurosteroid synthesis via GABAergic pathways, potentially addressing both neuroinflammation and neurotransmitter imbalances [69, 70]. NS and neuroactive steroids (NAS) represent a promising therapeutic approach that enhances GABAergic signaling by increasing the activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) or modulating GABAA function. This GABAergic signaling exerts anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects by directly inhibiting the function of certain peripheral immune cells, such as macrophages and lymphocytes [71, 72]. Research has found that a decrease in GABA concentration in the brain is associated with the occurrence of certain psychological disorders, such as anxiety and MDD, as well as central neurological disorders like epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease [73]. Moreover, increasing evidence suggests that the GABAergic system’s influence on neuroinflammation is a contributing factor to the etiology of psychiatric disorders [74]. In neuroinflammation, microglia and astrocytes play crucial roles. NS acting as positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of GABAAR, along with GABA itself, can modulate the production of inflammatory mediators through their regulatory effects on GABAergic signaling pathways. The steroid-PAM, allopregnanolone, can suppress the activation of microglia and astrocytes, normalizing their function and exerting anti-inflammatory effects [75]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two forms of allopregnanolone. The first is brexanolone (allopregnanolone), an exogenous NAS that acts as a positive modulator of the GABAA, contributing to its antidepressant and anxiolytic effects [76–78]. Brexanolone has demonstrated anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, and antidepressant-like activities [79], primarily used for treating postpartum depression (PPD). The second is an oral 3α-reductase steroid, zuranolone, which received FDA approval in 2023 for the treatment of PPD. A retrospective study involving seven studies with 1662 MDD patients found that zuranolone exhibited rapid antidepressant effects, which were reproducible and well-tolerated, with no serious adverse reactions reported [80]. Ligands such as XBD173, YLIPA08, and ONO-2952 have demonstrated rapid anxiolytic and antidepressant effects in animal models [81–83]. Currently, etifoxine is the only TSPO ligand approved in France for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Etifoxine exhibits dual mechanisms of action, targeting both TSPO and directly interacting with GABAA [69]. Recent studies suggest that etifoxine may also serve as an adjunctive treatment for MDD, but its efficacy in MDD is supported only by small-scale trials [70], necessitating larger RCTs to confirm translational potential.

TSPO PET Imaging and Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

OCD is a psychiatric disorder characterized by intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviors. The World Health Organization has listed it as one of the top 10 most disabling diseases. OCD commonly co-occurs with various somatic symptom disorders, impulse control disorders, anxiety disorders, MDD, anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, and substance use disorders [84]. The etiology of OCD is multifaceted, with current contributing factors including genetics, autoimmune responses, inflammation, neurobiology, familial-environmental influences, and psychosocial elements. Due to the intricate nature of both its causes and symptoms, diagnosing and treating the disorder pose significant challenges. However, TSPO imaging may assist in elucidating the neuroinflammation present in OCD patients [85], thereby offering potential methods for both diagnosis and treatment.

Most animal models of OCD are based on serotonergic and dopaminergic systems [86, 87]. In clinical research, OCD was initially proposed to be associated with inflammation, evolving from autoimmune processes, and an increasing number of OCD patients are being diagnosed with comorbid rheumatic diseases [88]. A subset of cases of OCD occurs in children following an infection, which is referred to as pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (PANDAS) (GABHS) or pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS). Sydenham’s chorea is a manifestation of GABHS, where the primary mechanism involves cross-reactivity between gangliosides in the basal ganglia neurons and the GABHS cell wall components. Additionally, a subset of OCD cases occurs in individuals with autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and multiple sclerosis. Previous autoimmune theories related to OCD were limited to the basal ganglia and thalamus. However, increasing research supports the presence of neuroinflammatory alterations in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuit in OCD patients. In studies examining the neurochemical abnormalities associated with OCD, the most significant regions for the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A(5-HT2 A),5-hydroxytryptamine transporter (5-HTT), 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1B(5-HT1B), and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) receptor binding, as well as fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake [89–94], are located in the dorsal caudate and orbitofrontal cortex, indicating a relationship between OCD and the CSTC circuit. A study demonstrated that untreated OCD patients exhibited significantly higher IL-6 and TNF-α levels compared to controls [95]. However, a meta-analysis involving 538 OCD patients and 463 healthy controls reported no significant differences in IL-6 or TNF-α levels, though IL-1β was elevated in OCD patients [96]. These mixed findings highlight the complexity of the relationship between OCD and inflammation. While certain subgroups, such as those with comorbid autoimmune conditions (e.g., PANDAS/PANS), demonstrate clear inflammatory involvement [97, 98], population-level studies suggest that systemic inflammation is not a universal feature of OCD. Further research is needed to clarify whether inflammatory mechanisms are relevant to specific OCD phenotypes or treatment-resistant cases.

Kumar et al. [97] reported elevated TSPO binding in the basal ganglia of PANDAS patients compared to healthy controls. While this observation offers insights into pediatric autoimmune disorders, its direct relevance to OCD remains uncertain, given the distinct diagnostic criteria and pathophysiology between PANDAS and OCD. However, this finding cannot be generalized to OCD. To our knowledge, the most compelling preliminary evidence linking OCD with neuroinflammation comes from a recent TSPO PET imaging study using the second-generation tracer[18F]FEPPA [98]. In this exploratory investigation involving OCD patients, researchers observed 30–36% increases in TSPO VT within key CSTC circuit regions—including the dorsal caudate, orbitofrontal cortex, thalamus, ventral striatum, and dorsal putamen—compared to healthy controls. Notably, these findings were regionally specific, with other gray matter areas showing less pronounced elevation. Although this single-study evidence tentatively associates CSTC circuit dysfunction with neuroimmune mechanisms in OCD, several critical limitations warrant emphasis. The modest sample size, lack of longitudinal data, and absence of mechanistic validation preclude definitive conclusions regarding the causality or directionality of observed associations. Further replication studies incorporating multi-modal imaging, larger cohorts, and clinical correlation analyses are essential to substantiate these initial observations and explore their therapeutic implications.

Current evidence supporting anti-inflammatory interventions in OCD remains preliminary. For example, a meta-analysis of five RCTs found that adjunctive celecoxib (200–400 mg/day) significantly reduced Yale-Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) scores compared to placebo [99]. However, these trials were limited by small sample sizes, short follow-up periods (8–12 weeks), and inconsistent inclusion criteria (e.g., treatment-resistant vs. newly diagnosed patients). Similarly, trials of minocycline (100–200 mg/day) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC, 2400 mg/day) demonstrated moderate effect sizes [100, 101], but high dropout rates (15–20%) and placebo responses (30–40%) complicate interpretation.

TSPO-targeted approaches have yet to be rigorously tested in OCD. While preclinical models suggest TSPO ligands reduce compulsive behaviors via GABAergic modulation [81], translational studies in humans are absent. This contrasts with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which may act broadly on peripheral and central inflammation without targeting neurosteroid pathways. Future trials should prioritize biomarker-driven designs (e.g., PET-confirmed neuroinflammation) and direct comparisons between TSPO ligands and conventional anti-inflammatories.

TSPO PET Imaging and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD is a psychiatric disorder characterized by complex psychological symptoms following exposure to traumatic events. The prevalence is notably high among high-risk occupations (e.g., veterans and healthcare workers), contributing to significant social dysfunction and economic burden [102, 103]. While the immune-inflammatory hypothesis of PTSD is supported by peripheral biomarker studies (e.g., elevated IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in blood) [104–106], TSPO PET imaging reveals distinct neuroimmune dynamics.

Several studies have identified the importance of the prefrontal cortex-hippocampus-amygdala network in PTSD [107–109]. An initial study measuring the TSPO VT values in PTSD patients and healthy controls using [[11]C]PBR28 reported lower TSPO VT values in the prefrontal cortex of the PTSD group, with a negative correlation between TSPO VT values and the severity of PTSD symptoms [110]. Recent research has revealed that, compared to the control group, the PTSD group exhibited lower TSPO VT values in the prefrontal-limbic circuitry. Furthermore, following LPS (acute stressor) induction, there was a lower elevation in TSPO VT within this circuitry [111]; all of this suggests that the neuroimmune response is suppressed in PTSD. However, Deri et al. reported a positive correlation between TSPO binding and the severity of PTSD symptoms in World Trade Center responders, regardless of PTSD diagnosis [112]. Similarly, Seo and colleagues demonstrated comparable findings in fibromyalgia patients, indicating that higher levels of TSPO binding correlate with increased PTSD symptoms [113]. A study using [18F]FEPPA found that TSPO VT values in 20 PTSD patients were 6.5%–30% higher compared to 23 healthy controls [114]. These conflicting TSPO PET findings may reflect temporal and phenotypic heterogeneity. Acute PTSD (< 6 months post-trauma) is associated with microglial exhaustion due to excessive stress-induced glucocorticoid release, leading to suppressed TSPO signals [110, 111]. In contrast, chronic PTSD (> 2 years) may exhibit compensatory neuroinflammation, particularly in cohorts with comorbid depression or chronic pain [112, 114]. For example, Deri et al. observed elevated [18F]FEPPA binding in World Trade Center responders, potentially linked to sustained peripheral inflammation from environmental toxin exposure [112]. Additionally, tracer affinity differences complicate comparisons: high-affinity ligands (e.g., [18F]FEPPA) detect subtle changes missed by [11C]PK11195 [17, 110].

The role of anti-inflammatory therapies in PTSD is contentious. A meta-analysis of 12 RCTs found that NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen) showed modest reductions in Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) scores [115], but effects were inconsistent across studies. For instance, trials in veterans with comorbid chronic pain reported stronger benefits, whereas studies in civilian populations showed negligible effects [115]. This heterogeneity may reflect differences in baseline inflammation or trauma chronicity. Despite the promising preclinical data [116], minocycline has only been tested in tiny pilot studies, and there are no large-scale RCTs that have confirmed its efficacy.

Recent preclinical studies suggest that TSPO ligands such as AC-5216 (XBD173) and YL-IPA08 may modulate PTSD-related neurobehavioral phenotypes. For instance, XBD173 has demonstrated efficacy in reducing fear and trauma-associated behaviors in animal models of stress-induced hyperarousal, independent of generalized anxiety pathways [117]. Similarly, YL-IPA08 exhibits anti-PTSD-like effects in preclinical paradigms, potentially mediated through TSPO-dependent neurosteroid biosynthesis and normalization of prefrontal-amygdala circuitry hyperactivity [118]. These findings align with clinical observations that neurosteroid-targeted therapies (e.g., zuranolone) may ameliorate PTSD symptoms by restoring GABAergic inhibition in stress-responsive networks [119]. While TSPO ligands historically referred to as “anxiolytic” agents demonstrate anti-trauma effects in preclinical models, their mechanisms extend beyond generalized anxiety modulation to include the resolution of fear extinction deficits and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation [120]. Further research is required to disentangle the specific neuroimmune and neuroendocrine pathways through which TSPO ligands exert therapeutic effects in PTSD pathophysiology.

TSPO PET Imaging and Schizophrenia and Psychosis Disorders

Schizophrenia is a serious psychiatric disorder of unknown etiology, typically manifesting in late adolescence to early adulthood. While its pathological mechanisms remain incompletely understood, emerging evidence implicates neuroinflammation as a key contributor. As detailed in the “Introduction” section, neuroinflammation involves microglial/astrocytic activation and cytokine dysregulation [1, 2]. In schizophrenia, alterations in peripheral and CSF inflammatory markers—such as elevated IL-1β, IL-12, TNF-α (microglia-associated), and IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β (astrocyte-associated)—have been consistently observed [121]. Critically, recent evidence directly links IL-6 levels to reduced gray matter volume in cortical regions implicated in schizophrenia pathogenesis [122]. Preclinical models further indicate divergent TSPO expression patterns: upregulation in neuroinflammatory injury versus downregulation in infection-induced neurodevelopmental models [123].

Recent studies on animal models of schizophrenia indicate that while TSPO is upregulated following severe neuroinflammatory damage, it is downregulated in infection-induced neurodevelopmental mouse models of schizophrenia [123]. In TSPO PET research involving schizophrenia spectrum and psychosis disorders patients, most studies assess BPND and VT as outcome measures, with a few studies measuring the distribution volume ratio (DVR)—the ratio of TSPO VT in regions of interest to overall brain TSPO VT. The most frequently selected brain regions include the frontal cortex (FC), temporal cortex (TC), and hippocampus (HIPP). Regions of interest (ROIs) are chosen based on previously reported TSPO-related changes in the literature and their established significance in schizophrenia spectrum disorders [124]. To date, there have been ten studies in TSPO PET research that utilized TSPO VT as an outcome measure. Compared to the healthy control group, the patient group exhibited a reduction [125, 126], elevation [127, 128], or no difference [129–134] in TSPO VT. Furthermore, one study indicated that the uptake of TSPO radioligands may vary with patient age during follow-up from psychotic episodes to antipsychotic treatment [127]. In studies using BPND as an outcome measure, three studies reported a significant increase in TSPO binding among patients [135–137], while four studies found no difference in BPND between the patient and control groups [138–141]. Additionally, one study revealed that untreated schizophrenia patients showed no difference in TSPO BPND compared to controls, whereas the BPND of medicated patients was higher than that of the control group [142]. Another study [129] found that medicated schizophrenia patients and individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis exhibited increased cortical gray matter [[11]C]PBR28 DVR compared to healthy controls, with [11C]PBR28 binding rates correlating with the severity of symptoms in ultra-high-risk individuals. However, there was no distinction in TSPO VT between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. The notably low levels of VT may be associated with elevated plasma proteins and cytokines in the acute phase of schizophrenia, thereby exaggerating the plasma input function.

The contradictory findings in TSPO PET studies of schizophrenia (e.g., reduced, elevated, or unchanged VT) may stem from methodological and biological heterogeneity. First, tracer generation critically impacts results: second-generation ligands (e.g., [11C]PBR28) are confounded by rs6971 polymorphism, whereas third-generation tracers (e.g., [18F]GE180) show reduced genotype sensitivity [49, 123]. For instance, Collste et al. reported lower TSPO binding in drug-naïve patients using [11C]PBR28, but this may reflect LAB subgroup inclusion rather than true neuroinflammation suppression [125]. Second, disease stage modulates TSPO signals: acute-phase patients exhibit elevated plasma cytokines (e.g., IL-6), which may interfere with plasma input function and underestimate VT [127], whereas chronic patients show microglial phenotype shifts linked to TSPO downregulation [123]. Finally, antipsychotic effects cannot be ignored. Holmes et al. found higher BPND in medicated patients, suggesting that drugs may paradoxically enhance neuroinflammatory signals [142].

A meta-analysis found that patients with schizophrenia and psychosis disorders exhibited lower TSPO VT compared to the control group across all study regions [143], with no observed effects from medication status, duration of illness, or severity of symptoms. The reduced TSPO binding in these patients may reflect alterations in mitochondrial parameters, such as mitochondrial density or TSPO binding site availability [144–146]. However, it is critical to note that TSPO PET imaging alone cannot conclusively diagnose mitochondrial dysfunction, as TSPO expression is influenced by multiple factors, including microglial activation states, genetic polymorphisms (e.g., rs6971), and ligand-specific binding properties. While preclinical studies suggest that TSPO downregulation correlates with mitochondrial impairment in certain models [123], direct evidence linking TSPO PET findings to mitochondrial bioenergetic deficits (e.g., ATP production and oxidative phosphorylation efficiency) in schizophrenia remains limited. Future studies integrating TSPO imaging with complementary mitochondrial biomarkers (e.g., mitochondrial DNA copy number and respiratory chain enzyme activity) are essential to validate these associations.

Currently, schizophrenia is primarily treated with medication. However, up to 40% of patients exhibit suboptimal responses to antipsychotic medications, highlighting the need for the development of novel therapeutic agents. Adjunctive anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., aspirin and NAC) have yielded mixed results in schizophrenia. A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs found modest improvements in positive symptoms with NSAIDs [147], but effects diminished in studies controlling for antipsychotic adherence. Minocycline trials demonstrated greater promise for cognitive symptoms [100], yet long-term safety concerns (e.g., microbiome disruption and hepatotoxicity) and non-specific anti-inflammatory actions limit their utility. Although preclinical studies indicate that TSPO ligands may provide a higher degree of specificity for CNS inflammation, clinical evidence is still in its infancy. A phase II trial of the TSPO ligand ONO-2952 failed to separate from placebo on PANSS scores [148], underscoring the need for biomarker-driven stratification (e.g., PET-defined neuroinflammation and genetic rs6971 polymorphism) in future trials. Therefore, further research is needed in the future to explore the potential therapeutic direction of anti-inflammatory for patients with schizophrenia.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The rising prevalence of chronic stress-related disorders (e.g., anxiety, MDD, and PTSD) may be influenced by complex societal factors. TSPO PET imaging has emerged as a transformative tool for investigating neuroinflammation in psychiatric disorders, yet its full clinical potential remains unrealized due to persistent methodological and translational challenges. A primary limitation lies in the inconsistent application of TSPO PET for patient stratification. Current studies often fail to leverage quantitative metrics such as regional binding affinity or distribution volume to define neuroinflammatory subtypes, resulting in heterogeneous treatment responses. Furthermore, variability in radioligand protocols (e.g., differing affinities of [18F]GE180 and [11C]PBR28) and the rs6971 genetic polymorphism complicate cross-study comparisons. To resolve these concerns, future research must prioritize the integration of TSPO PET with multi-modal biomarkers—including peripheral cytokine profiles, advanced neuroimaging, and CSF proteomics—to establish standardized, pathophysiologically defined cohorts. Such efforts could unify disparate findings and enhance the precision of neuroinflammatory subtyping in psychiatric disorders like MDD and schizophrenia.

Mechanistic ambiguities similarly constrain the therapeutic implications of TSPO PET findings. While broad anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., NSAIDs) non-specifically suppress systemic inflammation, TSPO-targeted ligands modulate neurosteroid synthesis and microglial activation, offering a theoretically more precise approach. However, the lack of head-to-head trials comparing these strategies in PET-stratified populations obscures their relative efficacy and safety. Compounding this issue, off-target TSPO binding in astrocytes and endothelial cells challenges the interpretation of PET signals, blurring the distinction between pathological neuroinflammation and compensatory glial responses. Genetic screening for rs6971 polymorphisms and preclinical PET-histopathology correlation studies are critical to resolving these uncertainties, ensuring that therapeutic mechanisms are accurately linked to cellular and molecular targets.

In order to transition TSPO PET from a research instrument to a clinical asset, it is imperative to implement longitudinal frameworks and safety-focused designs. Existing trials predominantly focus on short-term outcomes (≤ 12 weeks), neglecting the dynamic interplay between neuroinflammation and chronic disease progression. Serial PET imaging, coupled with long-term clinical monitoring, could elucidate how neuroinflammatory trajectories predict treatment resistance or cognitive decline. Concurrently, rigorous safety assessments—particularly for TSPO ligands in comorbid populations—are needed to evaluate risks such as hormonal dysregulation or mitochondrial toxicity. By embedding these principles into multi-center collaborations and mechanism-driven trials, TSPO PET can bridge the gap between neuroimmune discovery and individualized therapeutic strategies, ultimately reshaping the management of psychiatric disorders.

Despite its transformative potential, the clinical implementation of TSPO PET imaging faces significant barriers. Key methodological challenges include the confounding effects of rs6971 genetic polymorphism on tracer affinity, PVEs limiting resolution in small brain structures, the absence of a true TSPO-free reference region for quantification, and technical complexities in plasma input function modeling [16, 52, 53]. These factors necessitate specialized protocols and complicate data standardization across centers, hindering routine clinical adoption. Furthermore, high operational costs and limited accessibility of advanced PET ligands restrict widespread use. To realize TSPO PET’s promise for patient stratification, future biomarker-driven trials should prioritize multi-modal designs: (1) pre-screen participants for rs6971 status to homogenize binding affinity groups; (2) integrate quantitative TSPO metrics (e.g., regional VT) with peripheral inflammatory markers (e.g., cytokines) and clinical phenotypes to define neuroinflammatory subtypes; and (3) employ serial PET imaging to track neuroinflammatory trajectories alongside therapeutic responses, particularly for TSPO-targeted ligands (e.g., etifoxine) or anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., celecoxib) [16, 49, 70]. Such trials could elucidate whether TSPO PET can identify patients most likely to benefit from immunomodulatory therapies, ultimately advancing precision psychiatry.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The graphical abstract and Fig. 1 were created with BioRender.com.

Author Contribution

XUT, WXY, and MHY were responsible for literature collection and analysis; LYD wrote the first draft; CYH revised the text; LMC and ZHM supervised the project and served as corresponding authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mei-chen Liu, Email: meichenliu9019@163.com.

Hui-min Zhang, Email: zhm@dmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zhang L, Hu K, Shao T, Hou L, Zhang S, Ye W et al (2021) Recent developments on PET radiotracers for TSPO and their applications in neuroimaging. Acta Pharm Sin B 11:373–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beurel E, Toups M, Nemeroff CB (2020) The bidirectional relationship of depression and inflammation: double trouble. Neuron 107:234–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ransohoff RM, Perry VH (2009) Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol 27:119–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boche D, Perry VH, Nicoll JAR (2013) Review: Activation patterns of microglia and their identification in the human brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 39:3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, Wang H, Leak RK, Chen S et al (2012) Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 43:3063–3070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sofroniew MV (2015) Astrocyte barriers to neurotoxic inflammation. Nat Rev Neurosci 16:249–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haim LB, Rowitch DH (2016) Functional diversity of astrocytes in neural circuit regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci 18:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galea I (2021) The blood–brain barrier in systemic infection and inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol 18:2489–2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dion-Albert L, Cadoret A, Doney E, Kaufmann FN, Dudek KA, Daigle B et al (2020) Vascular and blood-brain barrier-related changes underlie stress responses and resilience in female mice and depression in human tissue. Nat Commun; 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Menard C, Pfau ML, Hodes GE, Kana V, Wang VX, Bouchard S et al (2017) Social stress induces neurovascular pathology promoting depression. Nat Neurosci 20:1752–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng Y, Desse S, Martinez A, Worthen RJ, Jope RS, Beurel E (2018) TNFα disrupts blood brain barrier integrity to maintain prolonged depressive-like behavior in mice. Brain Behav Immun 69:556–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamintsky L, Cairns KA, Veksler R, Bowen C, Beyea SD, Friedman A et al (2020) Blood-brain barrier imaging as a potential biomarker for bipolar disorder progression. Neuroimage Clin; 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Medina-Rodriguez EM, Beurel E (2022) Blood brain barrier and inflammation in depression. Neurobiol Dis; 175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Meyer JH, Cervenka S, Kim M-J, Kreisl WC, Henter ID, Innis RB (2020) Neuroinflammation in psychiatric disorders: PET imaging and promising new targets. Lancet Psychiatry 7:1064–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papadopoulos V, Baraldi M, Guilarte TR, Knudsen TB, Lacapère J-J, Lindemann P et al (2006) Translocator protein (18kDa): new nomenclature for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor based on its structure and molecular function. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27:402–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turkheimer Federico E, Rizzo G, Bloomfield Peter S, Howes O, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Bertoldo A et al (2015) The methodology of TSPO imaging with positron emission tomography. Biochem Soc Trans 43:586–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Attwells S, Setiawan E, Rusjan PM, Xu C, Hutton C, Rafiei D et al (2020) Translocator protein distribution volume predicts reduction of symptoms during open-label trial of celecoxib in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 88:649–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rupprecht R, Papadopoulos V, Rammes G, Baghai TC, Fan J, Akula N et al (2010) Translocator protein (18 kDa) (TSPO) as a therapeutic target for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9:971–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papadopoulos V, Liu J, Culty M (2007) Is there a mitochondrial signaling complex facilitating cholesterol import? Mol Cell Endocrinol 265–266:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papadopoulos V (2014) On the role of the translocator protein (18-kDa) TSPO in steroid hormone biosynthesis. Endocrinology 155:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller WL (2013) Steroid hormone synthesis in mitochondria. Mol Cell Endocrinol 379:62–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morohaku K, Pelton SH, Daugherty DJ, Butler WR, Deng W, Selvaraj V (2014) Translocator protein/peripheral benzodiazepine receptor is not required for steroid hormone biosynthesis. Endocrinology 155:89–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banati RB, Middleton RJ, Chan R, Hatty CR, Kam WW, Quin C et al (2014) Positron emission tomography and functional characterization of a complete PBR/TSPO knockout. Nat Commun 5:5452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin E, Premkumar A, Veenman L, Kugler W, Leschiner S, Spanier I et al (2005) The peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor and tumorigenicity: isoquinoline binding protein (IBP) antisense knockdown in the C6 glioma cell line. Biochemistry 44:9924–9935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hauet T, Yao Z-X, Bose HS, Wall CT, Han Z, Li W et al (2005) Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor-mediated action of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein on cholesterol entry into Leydig cell mitochondria. Mol Endocrinol 19:540–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kletsas D, Li W, Han Z, Papadopoulos V (2004) Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) and PBR drug ligands in fibroblast and fibrosarcoma cell proliferation: role of ERK, c-Jun and ligand-activated PBR-independent pathways. Biochem Pharmacol 67:1927–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W, Hardwick MJ, Rosenthal D, Culty M, Papadopoulos V (2007) Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor overexpression and knockdown in human breast cancer cells indicate its prominent role in tumor cell proliferation. Biochem Pharmacol 73:491–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeno S, Zaaroor M, Leschiner S, Veenman L, Gavish M (2009) CoCl(2) induces apoptosis via the 18 kDa translocator protein in U118MG human glioblastoma cells. Biochemistry 48:4652–4661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gavish M, Veenman L (2018) Regulation of mitochondrial, cellular, and organismal functions by TSPO. In: Apprentices to genius: a tribute to Solomon H. Snyder p103–36 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Gatliff J, Campanella M (2015) TSPO is a REDOX regulator of cell mitophagy. Biochem Soc Trans 43:543–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan BJ, Hoek S, Fon EA, Wade-Martins R (2015) Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in Parkinson’s: from familial to sporadic disease. Trends Biochem Sci 40:200–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khalil B, El Fissi N, Aouane A, Cabirol-Pol MJ, Rival T, Liévens JC (2015) PINK1-induced mitophagy promotes neuroprotection in Huntington’s disease. Cell Death Dis 6:e1617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye X, Sun X, Starovoytov V, Cai Q (2015) Parkin-mediated mitophagy in mutant hAPP neurons and Alzheimer’s disease patient brains. Hum Mol Genet 24:2938–2951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klinedinst NJ, Regenold WT (2014) A mitochondrial bioenergetic basis of depression. J Bioenerg Biomembr 47:155–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuffner K, Triebelhorn J, Meindl K, Benner C, Manook A, Sudria-Lopez D et al (2018) Major depressive disorder is associated with impaired mitochondrial function in skin fibroblasts. Cells 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ransohoff RM, Schafer D, Vincent A, Blachère NE, Bar-Or A (2015) Neuroinflammation: ways in which the immune system affects the brain. Neurotherapeutics 12:896–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin L, Xiao L, Zhu H, Du Y, Tang Y, Feng L (2024) Translocator protein (18 kDa) positron emission tomography imaging as a biomarker of neuroinflammation in epilepsy. Neurol Sci 45:5201–5211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maeng SH, Hong H (2019) Inflammation as the potential basis in depression. Int Neurourol J 23:S63-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavisse S, Guillermier M, Hérard A-S, Petit F, Delahaye M, Van Camp N et al (2012) Reactive astrocytes overexpress TSPO and are detected by TSPO positron emission tomography imaging. J Neurosci 32:10809–10818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Notter T, Schalbetter SM, Clifton NE, Mattei D, Richetto J, Thomas K et al (2021) Neuronal activity increases translocator protein (TSPO) levels. Mol Psychiatry 26:2025–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nutma E, Stephenson JA, Gorter RP, de Bruin J, Boucherie DM, Donat CK et al (2019) A quantitative neuropathological assessment of translocator protein expression in multiple sclerosis. Brain 142:3440–3455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rupprecht R, Wetzel CH, Dorostkar M, Herms J, Albert NL, Schwarzbach J et al (2022) Translocator protein (18kDa) TSPO: a new diagnostic or therapeutic target for stress-related disorders? Mol Psychiatry 27:2918–2926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chauveau F, Boutin H, Van Camp N, Dollé F, Tavitian B (2008) Nuclear imaging of neuroinflammation: a comprehensive review of [11C]PK11195 challengers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 35:2304–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dollé F, Luus C, Reynolds A, Kassiou M (2009) Radiolabelled molecules for imaging the translocator protein (18 kDa) using positron emission tomography. Curr Med Chem 16:2899–2923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang D, McKinley ET, Hight MR, Uddin MI, Harp JM, Fu A et al (2013) Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 5,6,7-substituted pyrazolopyrimidines: discovery of a novel TSPO PET ligand for cancer imaging. J Med Chem 56:3429–3433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scarf AM, Ittner LM, Kassiou M (2009) The translocator protein (18 kDa): central nervous system disease and drug design. J Med Chem 52:581–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imaizumi M, Kim HJ, Zoghbi SS, Briard E, Hong J, Musachio JL et al (2007) PET imaging with [11C]PBR28 can localize and quantify upregulated peripheral benzodiazepine receptors associated with cerebral ischemia in rat. Neurosci Lett 411:200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang MR, Kida T, Noguchi J, Furutsuka K, Maeda J, Suhara T et al (2003) [(11)C]DAA1106: radiosynthesis and in vivo binding to peripheral benzodiazepine receptors in mouse brain. Nucl Med Biol 30:513–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikawa M, Lohith TG, Shrestha S, Telu S, Zoghbi SS, Castellano S et al (2017) 11C-ER176, a radioligand for 18-kDa translocator protein, has adequate sensitivity to robustly image all three affinity genotypes in human brain. J Nucl Med 58:320–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan Z, Calsolaro V, Atkinson RA, Femminella GD, Waldman A, Buckley C et al (2016) Flutriciclamide (18F-GE180) PET: first-in-human PET study of novel third-generation in vivo marker of human translocator protein. J Nucl Med 57:1753–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Setiawan E, Attwells S, Wilson AA, Mizrahi R, Rusjan PM, Miler L et al (2018) Association of translocator protein total distribution volume with duration of untreated major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiatry 5:339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.James ML, Selleri S, Kassiou M (2006) Development of ligands for the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor. Curr Med Chem 13:1991–2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, Fujita M, Gjedde A, Gunn RN et al (2007) Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27:1533–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mathers CD, Loncar D (2006) Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 3:e442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Afridi R, Suk K (2021) Neuroinflammatory basis of depression: learning from experimental models. Front Cell Neurosci 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Richards EM, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Fujita M, Newman L, Farmer C, Ballard ED et al (2018) PET radioligand binding to translocator protein (TSPO) is increased in unmedicated depressed subjects. EJNMMI Res 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Setiawan E, Wilson AA, Mizrahi R, Rusjan PM, Miler L, Rajkowska G et al (2015) Role of translocator protein density, a marker of neuroinflammation, in the brain during major depressive episodes. JAMA Psychiatry 72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Li H, Sagar AP, Kéri S (2018) Translocator protein (18 kDa TSPO) binding, a marker of microglia, is reduced in major depression during cognitive-behavioral therapy. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 83:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li H, Sagar AP, Kéri S (2018) Microglial markers in the frontal cortex are related to cognitive dysfunctions in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 241:305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holmes SE, Hinz R, Conen S, Gregory CJ, Matthews JC, Anton-Rodriguez JM et al (2018) Elevated translocator protein in anterior cingulate in major depression and a role for inflammation in suicidal thinking: a positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry 83:61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Su L, Faluyi YO, Hong YT, Fryer TD, Mak E, Gabel S et al (2016) Neuroinflammatory and morphological changes in late-life depression: the NIMROD study. Br J Psychiatry 209:525–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joo Y-H, Lee M-W, Son Y-D, Chang K-A, Yaqub M, Kim H-K et al (2021) In vivo cerebral translocator protein (TSPO) binding and its relationship with blood adiponectin levels in treatment-naïve young adults with major depression: a [11C]PK11195 PET study. Bio 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Schubert JJ, Veronese M, Fryer TD, Manavaki R, Kitzbichler MG, Nettis MA et al (2021) A modest increase in 11C-PK11195-positron emission tomography TSPO binding in depression is not associated with serum C-reactive protein or body mass index. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 6:716–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Enache D, Pariante CM, Mondelli V (2019) Markers of central inflammation in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining cerebrospinal fluid, positron emission tomography and post-mortem brain tissue. Brain Behav Immun 81:24–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hannestad J, DellaGioia N, Gallezot J-D, Lim K, Nabulsi N, Esterlis I et al (2013) The neuroinflammation marker translocator protein is not elevated in individuals with mild-to-moderate depression: a [11C]PBR28 PET study. Brain Behav Immun 33:131–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eggerstorfer B, Kim J-H, Cumming P, Lanzenberger R, Gryglewski G (2022) Meta-analysis of molecular imaging of translocator protein in major depression. Front Mol Neurosci 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Gędek A, Szular Z, Antosik AZ, Mierzejewski P, Dominiak M (2023) Celecoxib for mood disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Med 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Zazula R, Husain MI, Mohebbi M, Walker AJ, Chaudhry IB, Khoso AB et al (2020) Minocycline as adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder: pooled data from two randomized controlled trials. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 55:784–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mattei C, Taly A, Soualah Z, Saulais O, Henrion D, Guérineau NC et al (2019) Involvement of the GABA(A) receptor α subunit in the mode of action of etifoxine. Pharmacol Res 145:104250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riebel M, Brunner L-M, Nothdurfter C, Wein S, Schwarzbach J, Liere P et al (2024) Neurosteroids and translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) ligands as novel treatment options in depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Bhandage AK, Jin Z, Korol SV, Shen Q, Pei Y, Deng Q et al (2018) GABA regulates release of inflammatory cytokines from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and CD4+ T cells and is immunosuppressive in type 1 diabetes. EBioMedicine 30:283–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim JK, Kim YS, Lee H-M, Jin HS, Neupane C, Kim S et al (2018) GABAergic signaling linked to autophagy enhances host protection against intracellular bacterial infections. Nat Commun 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Tovar-Gudiño E, Guevara-Salazar JA, Bahena-Herrera JR, Trujillo-Ferrara JG, Martínez-Campos Z, Razo-Hernández RS et al (2018) Novel-substituted heterocyclic GABA analogues. Enzymatic activity against the GABA-AT enzyme from Pseudomonas fluorescens and in silico molecular modeling. Molecules 23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Bannister E (2019) There is increasing evidence to suggest that brain inflammation could play a key role in the aetiology of psychiatric illness. Could inflammation be a cause of the premenstrual syndromes PMS and PMDD? Post Reprod Health 25:157–61 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Bäckström T, Doverskog M, Blackburn TP, Scharschmidt BF, Felipo V (2024) Allopregnanolone and its antagonist modulate neuroinflammation and neurological impairment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 161 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Coirini H, Rey M (2015) Synthetic neurosteroids on brain protection. Neural Regen Res 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Eser D, Romeo E, Baghai TC, Schüle C, Zwanzger P, Rupprecht R (2006) Neuroactive steroids as modulators of depression and anxiety. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 1:517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zorumski CF, Paul SM, Izumi Y, Covey DF, Mennerick S (2013) Neurosteroids, stress and depression: potential therapeutic opportunities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37:109–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Melón L, Hammond R, Lewis M, Maguire J (2018) A novel, synthetic, neuroactive steroid is effective at decreasing depression-like behaviors and improving maternal care in preclinical models of postpartum depression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Meshkat S, Teopiz KM, Di Vincenzo JD, Bailey JB, Rosenblat JD, Ho RC et al (2023) Clinical efficacy and safety of Zuranolone (SAGE-217) in individuals with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 340:893–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barron AM, Higuchi M, Hattori S, Kito S, Suhara T, Ji B (2020) Regulation of anxiety and depression by mitochondrial translocator protein-mediated steroidogenesis: the role of neurons. Mol Neurobiol 58:550–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ren P, Ma L, Wang J-Y, Guo H, Sun L, Gao M-L et al (2020) Anxiolytic and anti-depressive like effects of translocator protein (18 kDa) ligand YL-IPA08 in a rat model of postpartum depression. Neurochem Res 45:1746–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nozaki K, Ito H, Ohgidani M, Yamawaki Y, Sahin EH, Kitajima T et al (2020) Antidepressant effect of the translocator protein antagonist ONO-2952 on mouse behaviors under chronic social defeat stress. Neuropharmacology 162 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Dean SL, Singer HS (2017) Treatment of Sydenham’s chorea: a review of the current evidence. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 7:456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meyer J (2021) Inflammation, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and related disorders. In: The neurobiology and treatment of OCD: accelerating progress. Chap 210:p31–53

- 86.Alonso P, López-Solà C, Real E, Segalàs C, Menchón JM (2015) Animal models of obsessive-compulsive disorder: utility and limitations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11:1939–1955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Grados M, Prazak M, Saif A, Halls A (2015) A review of animal models of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a focus on developmental, immune, endocrine and behavioral models. Expert Opin Drug Discov 11:27–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leone D, Gilardi D, Corrò BE, Menichetti J, Vegni E, Correale C et al (2019) Psychological characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease patients: a comparison between active and nonactive patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 25:1399–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]