Abstract

This study presents the optimization of MOCVD growth conditions for InAs/InGaAs quantum dots-in-a-well (DWELL) structures on 4-inch GaAs substrates incorporating an InGaP seed layer. By precisely tuning the arsenic-to-indium (As/In) ratio, growth temperature, and deposition duration, we achieved accurate control over the size and density of quantum dots (QDs), enabling a broad tuning of infrared emission wavelengths from 1200 to 1450 nm. Using photoluminescence spectroscopy and numerical modeling, we investigated the impact of In content of the InₓGa1−ₓAs strain-reducing cap layers on the optical properties of the DWELL structures. A linear correlation was observed between In concentration and the emission peak wavelength, highlighting the significant role of the capping layer composition in tuning QD emission characteristics. This work highlights the critical importance of growth parameter optimization in engineering QD-based heterostructures paving the way for their integration into advanced optoelectronic and quantum technology applications.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-21226-9.

Keywords: InAs/InGaAs DWELL, MOCVD, Infrared emission, Optoelectronics, Photoluminescence

Subject terms: Materials science, Nanoscience and technology, Optics and photonics, Physics

Introduction

InAs quantum dots (QDs) have been considered as a very attractive III-V semiconductor zero-dimensional structures for state-of-the-art infrared based optoelectronics owing to their unique electronic and optical properties1–3. These tiny structures have size-tunable bandgaps, which allows precise control over emission wavelengths, essential for devices like light-emitting diodes4–6, laser diodes7,8, and photodetectors9,10. Their ability to confine charge carriers in three dimensions results in sharp emission lines and improved performance in communication systems11. Moreover, the ability of InAs QDs to confine charge carriers in all three dimensions is particularly advantageous for quantum applications12,13, as this confinement leads to discrete energy levels essential for realizing stable qubits14. Furthermore, InAs QDs exhibit long coherence times, making them strong candidates for quantum information processing tasks such as quantum communication15. Their size-tunable bandgaps allow precise control over emission wavelengths, ensuring compatibility with quantum protocols that depend on specific photon energies16.

Traditionally, the fabrication of InAs QDs relied on molecular beam epitaxy (MBE)17, which offers ultra-high vacuum conditions and atomic-level control over deposition rates and layer composition. This precise control enables the growth of QDs with exceptional uniformity, narrow size distribution, and high crystalline quality, critical for research-grade devices and fundamental studies. However, MBE systems are typically slower, more expensive, and less suitable for large-scale production. In contrast, Metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), has emerged as a promising alternative solution allowing large scale production18,19. MOCVD operates at higher pressures using metal-organic precursors, which allows for significantly higher growth rates and better scalability20. MOCVD is more compatible with industrial manufacturing environments and has proven capable of producing high-density InAs QDs on GaAs substrates with good optical properties, including room-temperature lasing at 1.3 µm18,21, an important wavelength for fiber-optic communications. While MOCVD may offer slightly less precision compared to MBE, recent advancements have closed the performance gap, making it a compelling alternative for commercial applications where throughput and cost-effectiveness are key.

In this context, we aim to explore the potential of MOCVD for InAs/InGaAs quantum dots-in-a-well (DWELL) structures on a GaAs substrate to achieve broadband emission wavelength range in the infrared region. We show that a broad photoluminescence (PL) emission ranging from 1200 nm to 1450 nm could be achieved. By fine-tuning growth parameters like the As/In ratio, growth temperature, and duration, we demonstrate that MOCVD can effectively produce high-density InAs QDs with extended emission ranges. This work provides valuable insights for enhancing the performance of optoelectronic devices through broad band emission wavelengths range.

Effect of growth conditions on the size and density of InAs QDs grown by MOCVD

The initial phase of this study focused on optimizing the growth of InAs QDs on GaAs substrates. A schematic of the structure is presented in Figure S1. A 4-inch GaAs substrate was employed, onto which a 5 nm GaAs buffer layer was first deposited. Subsequently, a 5 nm In0.33Ga0.67P interlayer was introduced between the GaAs and InAs layers to enhance both the quality and the density of the InAs QDs, as previously reported22,23. The InAs QDs were then grown atop the In0.33Ga0.67P interlayer. Further optimization of the growth parameters was conducted using MOCVD, involving systematic variation of the arsenic-to-indium (As/In) ratio, growth temperature, and deposition time to achieve precise control over the QD size and density.

Figure 1 shows AFM observations of InAs QDs for different growth conditions. The primary focus was to adjust the As/In ratio to optimize QD homogeneity (Figure 1(a)). Starting with an As/In ratio of 100, two distinct populations of InAs QDs were observed, with average diameters of approximately 20 nm and 80 nm, respectively. Our first objective was therefore to eliminate the large QD population for achieving a higher uniformity of the size of QDs. Increasing the As/In ratio from 100 to 135 effectively eliminated the large QD population, albeit at the cost of reducing the overall QD density. Further increasing the As/In ratio to 150 led to the reappearance of the dual QD populations, determining the selection of As/In = 135 despite the slightly lower density observed.

Figure 1.

Optimization of InAs QD growth using MOCVD: (a) Effects of As/In Ratio, (b) growth temperature, and (c) growth time.

To address this density issue, the growth temperature was varied between 525 °C and 545 °C as presented in Figure 1(b). The results indicated an increase in QD density from 1.1 to 3.7 x 109 QDs/cm2 as the temperature increased from 525 °C to 535 °C, followed by a decrease to 2.8 x 109 QDs/cm2 at 545 °C can be attributed to increased evaporation or desorption of material from the surface, which reduces the effective amount of material available for QD formation. Based on these findings, the optimal growth temperature of 535 °C was chosen for subsequent experiments. Additionally, the growth time was adjusted to further optimize QD density (see Figure 1(c)). Initially grown for 12 seconds, the fabrication time was extended incrementally up to 60 seconds. It was observed that a fabrication time of 40 seconds yielded the highest QD density of 5.3 x 109 QDs/cm2 and provided stable, reliable and reproducible growth conditions.

Tuning light emission in InAs/InxGa1-xAs DWELL structures through indium composition variation

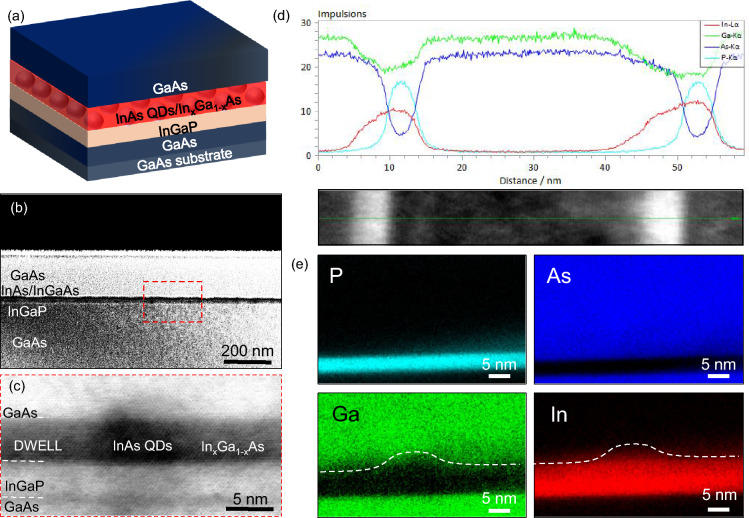

The effect of In concentration in the InxGa1-xAs layer on the emission wavelength was then investigated. Figure 2(a) shows the global grown structure used for the fabrication of InAs/InGaAs DWELL on a GaAs substrate. An InxGa1-xAs layer is deposited over the QDs to fine-tune the wavelength emission by changing Indium-Gallium (In/Ga) ratio. Then, a 200 nm GaAs capping layer is deposited on top of the QDs. XRD was used to control the composition and thickness of the layer, as shown in Figure S2 and Table S1, respectively. Figure 2(b) shows a TEM cross-section of the grown structure, displaying the different layers. The image reveals the GaAs substrate at the bottom, the In0.33Ga0.67P barrier layer above it, the DWELL layer, and the GaAs capping layer at the top. The clear separation between these layers indicates that interdiffusion between the layers is limited. Moreover, Figure 2(c) provides a close-up, HRTEM image of the DWELL structure. The image contrast could be related with the In composition, the dark region corresponding to an enrichment of In which could be attributed to the presence of the InAs QDs. Additionally, Figure 2(d) presents the EDX profile, showing the elemental distribution of phosphorus (P), arsenic (As), gallium (Ga), and In across the layers of the DWELL structure. The profile reveals the uniform distribution of P in the In0.33Ga0.67P barrier layer, while As, Ga, and In are predominantly found in the InAs and InGaAs layers. This confirms the effectiveness of the growth method in achieving well-defined layers with distinct elemental distributions. The EDX data also suggests minimal diffusion of materials across the interfaces, which is crucial for optimizing the electronic and optical properties of the QDs. Finally, Figure 2(e) shows the EDX mapping of the spatial distribution of P, As, Ga, and In across the layers. The mapping provides a detailed visual representation of the distribution of these elements across the entire structure near a QD.

Figure 2.

Structural and compositional characterization of InAs QDs grown by MOCVD (a) Schematic of the growth structure of InAs QDs. (b) TEM Cross section the fabricated structure using MOCVD (c) HRTEM image of InAs/InGaAs DWELL structure (d) EDX profile and (e) mapping showing elemental composition across the layers, highlighting P, As, Ga, and In distribution.

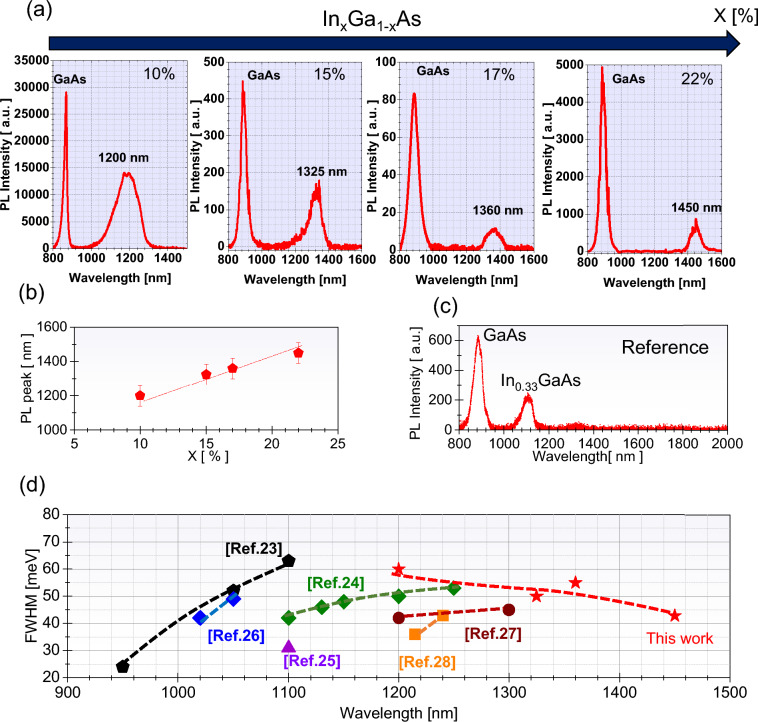

The light emission from InxGa1-xAs DWELL structures was measured at different In/Ga ratios, as presented in Figure 3(a). The spectra clearly show that as the In composition (x) increases from 0.11 to 0.22, the emission peak shifts from 1200 nm to 1450 nm. This shift to longer wavelengths indicates that increasing the In content in the InxGa1-xAs layer allowed to tune the InAs QDs emission. This can be explained by the fact that increasing the In composition reduces the strain. As a result, the band gap decreases, which leads to an increase in the emission wavelength. Moreover, we also plotted the peak position of the emission spectra as a function of the x ratio in Figure 3(b). This plot highlights a linear increase of the emission peak as a function of the In content in the InₓGa1−ₓAs layer. This relationship is important for designing devices that need specific light wavelengths. Besides, we measured the light emission from the In0.22Ga0.67As layer alone without InAs QDs considered as a reference sample (Figure 3(c)). The PL measurements shows a peak at 1180 nm showing that the signal of the DWELL structure comes from InAs QDs. Figure 3(d) compares the tuning range of the PL spectra achieved in this work with those reported recently in other studies23–28. This comparison includes variations in the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the PL peaks and different substrate used for the growth of InAs QDs. It is noteworthy that our approach demonstrates that InAs/InGaAs DWELL can be successfully used on GaAs substrates to bridge the wavelength gap between the GaAs and InP technological routes. Besides, the homogeneity of the QD distribution in the DWELL structure was investigated across a 4-inch wafer, as shown in Figure 4(a). Three representative positions were selected: the center (P1), the middle (P2), and the edge (P3). AFM images were acquired at each position, as illustrated in Figure 4(b), to assess the surface uniformity. The analysis revealed that the average QD size remained consistent from the center to the middle; however, relatively larger QDs appeared at the wafer edge. In addition, the QD density decreased by approximately a factor of two from the center to the edge. Furthermore, PL measurements were performed at the same three positions, as shown in Figure 4(c), to evaluate the impact of these morphological variations on the optical properties. While the emission wavelength remained unchanged, the FWHM increased from 42 meV to 53 meV, accompanied by a reduction in PL peak intensity. These changes may be attributed to the lower QD density and increased defect density at the wafer edge.

Figure 3.

Emission Characteristics of InxGa1-xAs DWELL Structures and Comparison with Literature (a) Photoluminescence spectra of InxGa1-xAs DWELL structures showing a redshift in emission peaks from 1200 nm to 1450 nm as In content x increases from 0.11 to 0.22; (b) Linear relationship between emission peak wavelength and Indium content; (c) Emission peak of the In0.33GaAs layer alone at 1180 nm; (d) Comparison of the tuning range and FWHM with literature23–28 showing that MOCVD-grown structures achieve similar tuning ranges as MBE-grown structures, with added scalability for industrial applications.

Figure 4.

Investigation of the spatial uniformity of QD distribution and optical properties across a 4-inch DWELL wafer (a) Schematic of measurement positions: center (P1), middle (P2), and edge (P3). (b) AFM images at the three positions showing QD size and density variations. (c) PL spectra measured at P1, P2, and P3, illustrating changes in FWHM and peak intensity.

Temperature-dependent PL measurements have been used to explore in more details the optical properties of InAs/InGaAs DWELL structures. For these measurements, the samples have been cooled down with a closed-cycle helium-cooled cryostat and excited with a 33 mW continuous wave laser diode at 532 nm, focused onto the sample with a spot diameter of approximately 80 μm. Figure 5(a) displays temperature-dependent PL spectra from 13 K to 300 K of the sample In0.17Ga0.83As. Figure 5(b) shows the temperature dependence of PL intensity and emission wavelength. A decrease of the PL emission by one order of magnitude is observed from 13 K to 300 K, which can be attributed to the higher likelihood of non-radiative recombination processes (such as carrier scattering and defect-related recombination) at elevated temperatures. An Arrhenius analysis using the integrated PL intensity as a function of the temperature reveals two activation energies (see Figure S3). The first activation energy, 27 ± 4 meV, is attributed to the energy separation between heavy-hole states. This suggests that electron-hole pairs formed with electrons in their first bound state and heavy holes in their second bound state lead to the formation of a dark state, as previously reported by Harbord et al.29. The second activation energy, 512 ± 215 meV, is associated with a strong quenching mechanism, most likely arising from the thermal escape of carriers from the QDs into the wetting layer and/or the surrounding matrix. Moreover, a 17% increase of the PL intensity is observed from 13 K to 50 K which could be explained by the thermally activated detrapping of carriers previously trapped in localized states of the wetting layer or another ternary alloy layer. Additionally, the peak position shifts from 1290 nm to 1360 nm with a sharp acceleration of the redshift observed above 250K. This phenomenon could be attributed to a thermally activated carrier redistribution in favor of larger QDs at higher temperatures which would also explain why the redshift does not follow the Varshni law. For comparison, the expected redshift for bulk InAs, calculated using the Varshni parameters (α = 2.76 × 10−4 eV/K and β = 83 K), is represented by the red line in Figure S4. The deviation from this behavior is explained by a thermally activated carrier redistribution between QDs of different sizes. At higher temperatures, carriers preferentially occupy larger QDs, which results in the strong redshift observed above 250 K.

Figure 5.

Temperature-dependent and power-density-dependent PL spectra of InAs/InGaAs DWELL structures with numerical simulations. (a) Temperature-dependent PL spectra from 50 K to 300 K for DWELL structure of x=17%. (b) Temperature dependence of PL intensity and the position of the PL peak. (c) Deconvolution of the measured PL spectrum of DWELL structure for x=15% showing additional peaks at 1219 nm and 1113 nm under high excitation. (d) Numerical simulations of orbital effects.

This hypothesis is further supported by the behavior of the FWHM of the PL spectra (see Figure S5). Normally, a temperature increase would lead to FWHM broadening due to exciton–phonon coupling at the single-QD level. However, in this study, a decrease in FWHM is observed from 13 K to 300 K. This counterintuitive behavior can only be explained by a carrier redistribution mechanism, where carriers transfer to larger QDs as the temperature rises, reducing the overall spectral broadening.

These results provide a comprehensive understanding of the temperature-dependent optical behavior of InAs/InGaAs DWELL structures. They highlight the critical role of non-radiative recombination, localized state detrapping, and particularly thermally activated carrier redistribution in governing both the emission energy and linewidth evolution with temperature. This redistribution process explains the observed deviation from the Varshni law and the unexpected narrowing of the PL linewidth at higher temperatures, offering valuable insights into carrier dynamics within QD systems.

Besides, the PL of the InAs/InGaAs DWELL was performed as a function of the excitation power density (see Figure S6), showing the appearance of additional peaks at 1219 nm and 1113 nm under high excitation conditions (Figure 5(c)). This observation can be attributed to the increased carrier density at higher excitation powers, which leads to the observation of QD excited-state transitions, where electrons and holes recombine at different energy levels. As more carriers are injected into the system, new peaks appear as a consequence of the band filling of the lower QD energy states.

To gain deeper insight into the observed PL behavior and accurately estimate the mean dimensions of the buried InAs QDs, numerical modeling combined with PL spectroscopy was employed. Figure 5(c) illustrates the spectral deconvolution of the PL data, isolating contributions from various emission states, while Figure 5(d) shows the orbital configuration of each peak. The modeling involved solving the single-band 3D Schrödinger equation within the effective mass approximation, using the finite element method in Cartesian coordinates to determine the ground and excited state energies of the QDs. The detailed methodology is elaborated elsewhere30. The simulated QDs were considered to have a truncated pyramidal geometry with negligible intermixing at the InGaAs/InAs and InAs/InGaP interfaces. Interband transition energies were numerically adjusted by varying the base and height dimensions of the truncated pyramid, as well as the base-to-top surface ratio. Matching theoretical emission energies with experimental PL emission maxima enabled precise estimation of the buried QD dimensions. A schematic representation of the modeled InAs QD is provided in Figure S7. The truncated pyramidal-shaped QDs were found to have a base width of approximately 28 nm, a height of 4.2 nm, and a top-to-base surface area ratio of 25%.

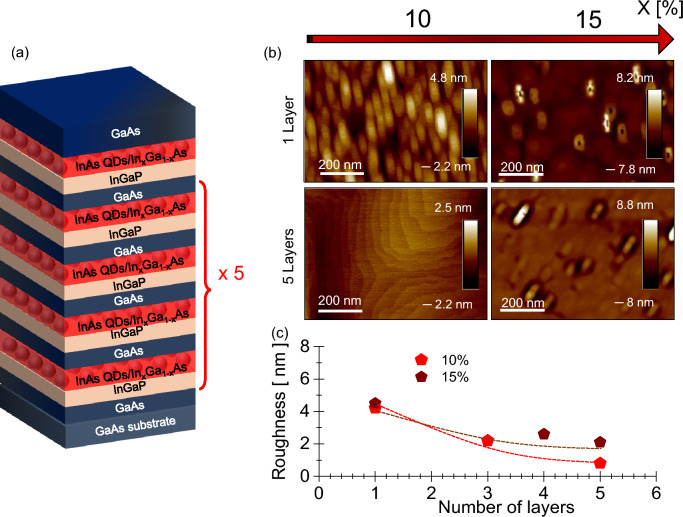

Influence of the number of the DWELL Layers on the improvement of emission properties

Our final investigation examines the influence of the number of DWELL on the emission properties of our structures. We compared the PL emissions of structures containing 1 and 5 DWELL layers, each with In concentrations of 10% and 15% in the InGaAs layers. Figure 6(a) illustrates the overall structure of the five-layer DWELL, while Figure 6(b) presents roughness measurements with a GaAs capping layer for both single-layer and five-layer structures. For structures with a 10% In concentration, increasing the number of layers significantly reduces surface roughness, decreasing it from 4.5 nm to 0.8 nm. However, at a concentration of 15%, the reduction in roughness is less pronounced, decreasing from 4.3 nm to 2.2 nm with additional layers. The variation of roughness as a function of the number of DWELL layers is depicted in Figure 6(c). The slope of this decrease becomes more gradual with the addition of more layers, indicating that the reduction in roughness slows down as In concentration increases, while adding more DWELL layers as reported elsewhere31.

Figure 6.

Influence of the In concentration and the number of the DWELL Layers on surface roughness (a) Surface roughness measurements for structures with one and five DWELL layers, each with a GaAs capping layer, at In concentrations of 0.1 and 0.15. (b) Variation in surface roughness as a function of the number of DWELL layers.

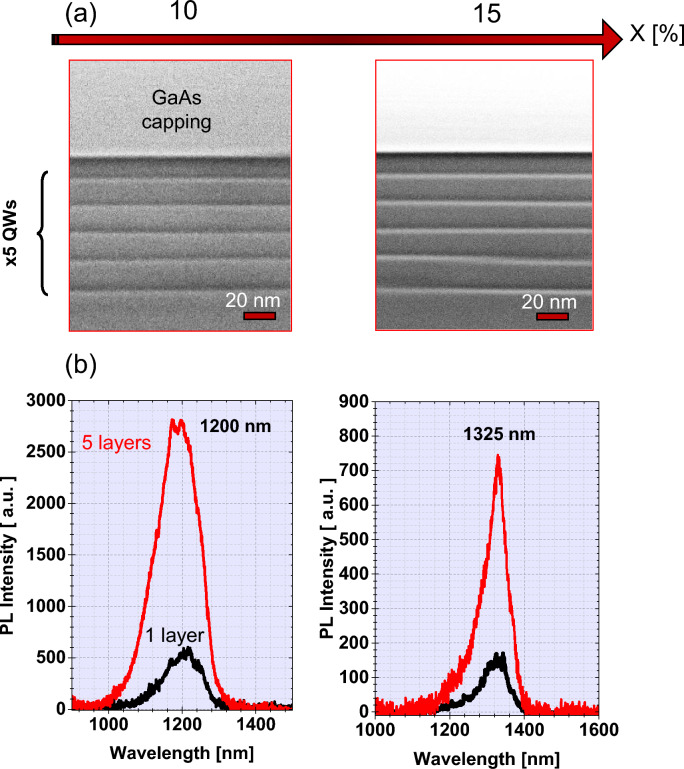

Finally, FIB-STEM were conducted to investigate the crystalline quality of our heterostructures (see Figure 7(a)). Our FIB-STEM analysis demonstrates that higher In concentrations in InGaAs layers correlates with increased defects, indicating strain introduction within the layers. This strain results from lattice mismatches, which generate dislocations and imperfections within the crystal structure, affecting overall material quality and surface morphology. PL measurements further elucidate the influence of layer count and In concentration on emission intensity as shown in Figure 7(b). With five DWELL layers, we observed a significant enhancement in PL intensity compared to single-layer structures, but this enhancement varies with In content. For an In concentration of x = 10%, the PL intensity at an emission wavelength of 1200 nm increased by a factor of 5.2 relative to the single-layer structure. However, at x = 15%, the PL intensity at 1325 nm increased by a factor of 4.1. This trend indicates that while additional DWELL layers enhance PL emission, the degree of enhancement diminishes as In concentration increases, leading to higher dislocation densities. This outcome highlights the compromise in optimizing DWELL structures: higher In content for longer wavelengths may cause strain and dislocations, limiting PL intensity improvements from additional layers. It emphasizes the need to balance layer count and In concentration for optimal emission, intensity, and crystal quality. In this sense, it is important to emphasize that this work represents a significant practical advancement by achieving broadband photoluminescence covering 1.2–1.45 µm on GaAs substrates using MOCVD. This achievement effectively bridges the gap between GaAs- and InP-based QD technologies, offering a scalable and CMOS-compatible route for broadband near-infrared emitters. However, extending the emission wavelength through higher In incorporation and increased stacking of QD layers introduces a trade-off: although broader spectral coverage is attained, PL intensity decreases and crystalline quality degrades due to accumulated strain and defect formation. These findings highlight the necessity of optimizing growth conditions to balance emission performance with structural integrity.

Figure 7.

Impact of In concentration and the number of layers on defects and PL response in InAs/InGaAs DWELL Structures (a) TEM images and (b) PL intensity measurements for one-layer and five-layer DWELL structures at different In concentration.

Methods

Growth behavior of InAs/InxGa1-xAs DWELL structures

InAs/InxGa1-xAs DWELL structures were grown using a MOCVD reactor from Applied Materials (Santa Clara, California, USA) on a 4-inch GaAs substrate. The MOCVD system was equipped with trimethylgallium (TMGa), tertiarybutylarsine (TBAs), and trimethylindium (TMIn) as organometallic precursors for Ga, As, and In, respectively. Initially, a thin GaAs layer was grown at 620 °C and a pressure range of 20 to 100 Torr, prior to the deposition of the InGaP layer at 500 °C. Following this, InAs quantum dots (QDs) were grown under varying As/In ratios, temperatures, and growth durations. The growth rate of the QDs was estimated to be 0.18 Å/s, as there was no in-situ control over the deposited In amount. The QDs were positioned on top of a 5 nm thick InGaP layer with varying In concentrations. A 200 nm GaAs cap layer was added at 520 °C to complete the heterostructure.

Characterization

Structural characterization was performed using a suite of advanced imaging and analytical techniques. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) in a Bruker JD-DXM tool analysis was carried out to determine the crystallographic properties and verify the structural integrity of the grown layers. A Helios 450S-FEI dual beam microscope and STEM imaging at 25 kV was used for the observation of the quality of the DWELL layers. Initial steps included depositing a series of Pt protective layers on a 20 × 3 μm2 sample area using an electron beam (3 kV, 3.2 nA) with approximately 100 nm of Pt. Subsequently, a 500 nm thick Pt protective layer was applied under a focused ion beam (30 kV, 0.43 nA). A specimen measuring 20 × 3 μm2 was then etched from the substrate to a depth of about 3 μm, transferred to a grid via an Omniprobe needle for mechanical manipulation, and thinned using a focused ion beam (30 kV, reducing emission current from 2.5 nA to 40 pA) to approximately 80 nm width. Finally, transmission images of the cross-section were acquired in scanning mode at 29 kV and 100 pA using bright field detection on the same equipment. Tapping-mode Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) was conducted using a Bruker ICON™ instrument to analyze surface topography and confirm the QD characteristics. Micro-photoluminescence (µPL) measurements were performed at 300 K using a 633 nm diode-pumped solid-state laser, with excitation power densities varying from 400 W/cm2 to 20 kW/cm2. The emitted PL was dispersed by a spectrometer and detected using a liquid nitrogen-cooled InGaAs (IGA) photodetector. The µPL technique enabled the use of higher power densities for the same nominal laser power, as it focused the laser onto a much smaller spot size (around 4 µm in µPL, compared to about 200 µm in conventional PL measurements).

Numerical modeling

The numerical modeling was performed by solving the single-band 3D Schrödinger equation within the effective mass approximation, using the finite element method in Cartesian coordinates to determine the ground and excited state energies of QDs. The simulated QDs were assumed to have a truncated pyramidal geometry with negligible intermixing at the InGaAs/InAs and InAs/InGaP interfaces. Interband transition energies were numerically tuned by varying the base width, height, and base-to-top surface area ratio of the truncated pyramid.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated the successful fabrication of InAs/InGaAs DWELL structures on GaAs substrates using MOCVD, achieving a broad infrared emission range from 1200 nm to 1450 nm. By optimizing the growth parameters such as the In/As ratio, growth temperature, and growth time, we were able to control the size and density of the InAs QDs. The variation of the InxGa1-xAs composition showed a predictable linear relationship between the In content and the emission wavelength, enabling precise tuning of the emission range. Additionally, the increase in the number of DWELL layers significantly enhanced the photoluminescence intensity, although this was accompanied by a rise in strain and surface roughness, especially at higher In concentrations. Our findings highlight the trade-off between enhancing emission intensity and maintaining material quality, with the increasing strain from higher In content leading to increased dislocation density and potential degradation in crystal quality. The scalability of the MOCVD technique, along with its ability to produce high-density QDs and broadband emission, positions it as a promising method for future optoelectronic and quantum technologies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French National Programme d’Investissements d’Avenir (Investments in the Future), IRT Nanoelec, under Grant ANR-10-AIRT-05 and Grant ANR-15-IDEX-02 through the LabEx MicroElectronics and the French Renatech network.

Author contributions

D.M. and T.B. conceived the study. D.M., M.M., B.I., S.C., N.C., F.B., N.R., J.M., B.S., and T.B. contributed to the development of characterization methodologies and the interpretation of results. B.I. performed the simulation. D.M. drafted the manuscript. T.B. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the French National Programme d’Investissements d’Avenir (Investments in the Future), IRT Nanoelec, under Grant ANR-10-AIRT-05 and Grant ANR-15-IDEX-02 through the LabEx MicroElectronics and the French Renatech network.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Driss Mouloua, Email: driss.mouloua@cea.fr.

Thierry Baron, Email: thierry.baron@cea.fr.

Reference

- 1.Zhou, T. et al. Continuous-wave quantum dot photonic crystal lasers grown on on-axis Si (001). Nat. Commun.11, 1–7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, S. et al. Electrically pumped continuous-wave 1.3 µm InAs/GaAs quantum dot lasers monolithically grown on on-axis Si (001) substrates. Opt. Express25, 4632–4639 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasan, S., Richard, O., Merckling, C. & Vandervorst, W. Encapsulation study of MOVPE grown InAs QDs by InP towards 1550 nm emission. J. Cryst. Growth557, 126010 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roshan, H. et al. Near infrared light-emitting diodes based on colloidal InAs/ZnSe core/thick-shell quantum dots. Adv. Sci.11, 2400734 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijaya, H. et al. Efficient near-infrared light-emitting diodes based on In (Zn) As–In (Zn) P-GaP–ZnS quantum dots. Adv. Funct. Mater.30, 1906483 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mouloua, D. et al. Exploring strategies for performance enhancement in micro-leds: a synoptic review of iii-v semiconductor technology. Adv. Opt. Mater.13, 2402777 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung, D. et al. Highly reliable low-threshold InAs quantum dot lasers on on-axis (001) Si with 87% injection efficiency. ACS Photonics5, 1094–1100 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, Q. et al. Development of modulation p-doped 1310 nm InAs/GaAs quantum dot laser materials and ultrashort cavity Fabry-Perot and distributed-feedback laser diodes. Acs Photonics5, 1084–1093 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun, B. et al. Fast near-infrared photodetection using III–v colloidal quantum dots. Adv. Mater.34, 2203039 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murata, T., Asahi, S., Sanguinetti, S. & Kita, T. Infrared photodetector sensitized by InAs quantum dots embedded near an Al0. 3Ga0. 7As/GaAs heterointerface. Sci. Rep.10, 11628 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portalupi, S. L., Jetter, M. & Michler, P. InAs quantum dots grown on metamorphic buffers as non-classical light sources at telecom C-band: a review. Semicond. Sci. Technol.34, 53001 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senellart, P. Semiconductor single-photon sources: progresses and applications. Photoniques 40–43 (2021).

- 13.Ramesh, P. R. et al. The impact of hole $ g $-factor anisotropy on spin-photon entanglement generation with InGaAs quantum dots. arXiv Prepr. arXiv2502.07627 (2025).

- 14.Jennings, C. et al. Self-assembled InAs/GaAs coupled quantum dots for photonic quantum technologies. Adv. Quantum Technol.3, 1900085 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heindel, T., Kim, J.-H., Gregersen, N., Rastelli, A. & Reitzenstein, S. Quantum dots for photonic quantum information technology. Adv. Opt. Photonics15, 613–738 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, Y. R., Han, I. S., Jin, C.-Y. & Hopkinson, M. Precise arrays of epitaxial quantum dots nucleated by in situ laser interference for quantum information technology applications. ACS Appl. nano Mater.3, 4739–4746 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seravalli, L. Metamorphic InAs/InGaAs quantum dots for optoelectronic devices: a review. Microelectron. Eng.276, 111996 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma, J. et al. Room-temperature continuous-wave topological Dirac-vortex microcavity lasers on silicon. Light Sci. Appl.12, 255 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, B. et al. Principles of Selective area epitaxy and applications in III–V semiconductor lasers using MOCVD: a review. Crystals12, 1011 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hijazi, H. et al. 940 nm micro-light-emitting diode fabricated on industry-compatible 300 mm Si (100) substrate by metal–organic chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Photonics Res.10.1002/adpr.202400226 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tournié, E. et al. Mid-infrared III–V semiconductor lasers epitaxially grown on Si substrates. Light Sci. Appl.11, 273–290 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forbes, D. V., Podell, A. M., Slocum, M. A., Polly, S. J. & Hubbard, S. M. OMVPE of InAs quantum dots on an InGaP surface. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process.16(1148), 1153 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugaya, T., Oshima, R., Matsubara, K. & Niki, S. In (Ga) As quantum dots on InGaP layers grown by solid-source molecular beam epitaxy. J. Cryst. Growth378, 430–434 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyborski, P. et al. Electronic and optical properties of InAs QDs grown by MBE on InGaAs metamorphic buffer. Materials (Basel).15, 1071 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.González, D. et al. Evaluation of different capping strategies in the InAs/GaAs QD system: composition, size and QD density features. Appl. Surf. Sci.537, 148062 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugaya, T., Oshima, R., Matsubara, K. & Niki, S. InGaAs quantum dot superlattice with vertically coupled states in InGaP matrix. J. Appl. Phys.114 (2013).

- 27.Alharbi, Z. M. & Al-Ghamdi, M. S. Influence of variation in indium concentration and temperature on the threshold current density in InxGa1-xAs/GaAs QD laser diodes. Heliyon11, (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Al Huwayz, M. et al. Optical properties of self-assembled InAs quantum dots based P-I–N structures grown on GaAs and Si substrates by molecular beam epitaxy. J. Lumin.251, 119155 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harbord, E., Spencer, P., Clarke, E. & Murray, R. Radiative lifetimes in undoped and p-doped InAs/GaAs quantum dots. Phys Rev. B-Condensed Matter Mater. Phys.80, 195312 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abouzaid, O. et al. O-band emitting InAs quantum dots grown by MOCVD on a 300 mm Ge-buffered Si (001) substrate. Nanomaterials10, 2450 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zribi, J., Ilahi, B., Morris, D., Aimez, V. & Arès, R. Chemical beam epitaxy growth and optimization of InAs/GaAs quantum dot multilayers. J. Cryst. Growth384, 21–26 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.