Abstract

The protective role of NO has been widely verified in cerebrovascular diseases. However, the beneficial effects of NO depend on its concentration and reactive oxygen species (ROS) level, which makes current NO donors face great difficulties in treating cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury (CIRI). Here, a tailored MoS2-based NO donor (MSNO) was constructed with defect-rich MoS2, in which the abundant S edge sites in the defects form -SNO, and the Mo sites can also bind NO to form Mo-NO. Combined with MSNO’s own strong ability to eliminate ROS, MSNO could provide pure NO at suitable concentrations like eNOS and avoid the generation of highly toxic ONOO-. After intravenous injection, MSNO with suitable nano-size could penetrate the blood-brain barrier of ischemia-reperfusion injured brain tissue, and effectively treat CIRI through multiple effects: inhibiting calcium overload, alleviating mitochondrial damage and endoplasmic reticulum stress, and inhibiting the inflammatory storm.

Subject terms: Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy, Drug delivery, Nanobiotechnology, Nanoparticles

Nitric oxide in known to have a protective effect in cerebrovascular disease. Here, the authors report on MoS2 an eNOS mimetic which releases NO while avoiding toxic ONOO- production, demonstrating therapeutic effects in inhibiting several damage pathways in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Introduction

Every year, more than 13.7 million new patients with cerebral infarction (CI) are diagnosed, and 5.8 million people die from CI1. Currently, CI is the leading cause of death and disability worldwide2. Recanalization of occluded cerebral vessels with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or endovascular embolectomy is the only intervention approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of CI3. However, vascular recanalization can further induce cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury (CIRI)4. CIRI has a complex pathological mechanism, which mainly involves neuronal apoptosis induced by calcium overload, oxidative stress and inflammatory storm5. Specifically, the massively released glutamate induces Ca2+ influx in neurons through the postsynaptic membrane N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) in CIRI6, which further leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and outbreak of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS)7,8, followed by the release of the pro-apoptotic factor Cytochrome C (Cyt-C) and endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) to lead to neuronal damage and death9. Moreover, mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (mtDNA) from damaged or dead neurons activates the microglial cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adennosine monophosphate synthase-stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) signaling pathway10, inducing microglia to polarizing toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1) and triggering a strong inflammatory storm that aggravates neuronal death11,12. Ultimately, calcium overload, oxidative stress, and inflammatory storm promote each other to eventually form a vicious cycle of neuronal damage and death. In view of the complex pathological mechanism of CIRI, each pathogenic factor may form a dynamic interactive network and eventually produce a buffer system that counteracts the therapeutic effect. Therefore, a single-dimensional regulatory strategy is very likely to lead to limited efficacy and difficulty in sustainability due to systemic compensatory effects. The development of a drug platform that can simultaneously reverse calcium overload, oxidative stress, and inflammatory storm is critical for the treatment of CIRI. However, there is currently no research that can simultaneously reverse these malignant progression due to the complex pathological mechanism of CIRI13.

NO is a super molecule with multiple beneficial biological effects, especially in cerebrovascular diseases14. The loss of steady-state NO holds a fundamental role in CIRI15. NO mainly comes from three enzymes: endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) from vascular endothelial cells, neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) from neurons, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) from glial cells or macrophages. Physiologically, at low reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, NO with suitable concentrations is mainly derived from eNOS and nNOS16. The NO produced by them can inhibit thrombosis, improve ischemic collateral circulation, and inhibit inflammatory response17,18. More importantly, NO can inhibit Ca2+ influx through the redox sites on the nitrosated NMDAR, and relieve intracellular Ca2+ overload by inhibiting related protein kinases and calcium-derived nNOS-mediated neurotoxicity19–21. However, under CIRI pathological conditions, eNOS and nNOS no longer generate NO but superoxide (O2.-) and other ROS because the electrons donated by NADPH are “decoupled” from NOS activity and/or the availability of L-arginine or BH4 is reduced22. Meanwhile, M1 polarized microglia produce a large amount of NO through iNOS, which can easily react with the high level of ROS (such as O2.-) to form highly toxic peroxynitrite (ONOO-) in CIRI, further aggravating neuronal damage and death23,24. Emerging NO-based treatments have also been continuously developed in recent years, including the NO donor S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO)25, direct inhalation of NO gas26, and the NO nanocarriers18. However, NO-based treatments do not achieve the desired therapeutic effect in the treatment of CIRI. On the one hand, gaseous NO is difficult to deliver, and small molecule NO donors often have poor efficacy due to lack of target selectivity25. In addition, inhalation administration of NO requires special instruments for safety monitoring, which greatly increases the difficulty of clinical application26. On the other hand, the release rate of NO is difficult to control, and an excessively high or a low concentration of NO may have a harmful effect on CIRI. More importantly, without eliminating ROS in situ, NO promotes the production of destructive ONOO-, which in turn aggravates neuronal damage and death23,24.

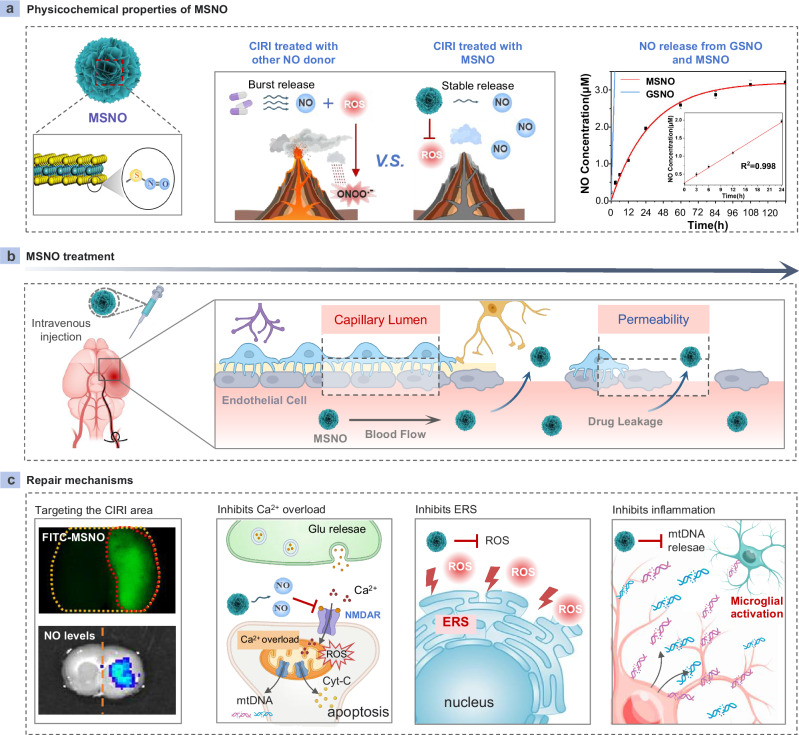

Here, we show an effective strategy to customize a MoS2 based NO nanomedicine (MSNO) by introducing -NO groups into a unique MoS2 nanosheet layer with abundant -SH groups (Scheme a). MSNO not only achieves the stable release of NO, but also eliminates O2.- in situ to avoid the conversion of NO released by MSNO into ONOO-, and ultimately achieves a sustained and stable release of pure NO (Fig. 1a). After intravenous injection, MSNO with appropriate nano-size crosses the ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injured blood-brain barrier (BBB) and targets I/R-damaged brain tissue with high specificity (Fig. 1b), and then inhibits neuronal Ca2+ overload and eliminates ROS burst to relieve mitochondrial damage and inhibit neuronal injury and death through stable and continuous release of NO similar to eNOS. MSNO also inhibits ERS by alleviating oxidative stress. Moreover, MSNO effectively reduces the release of mtDNA from neuronal mitochondria into the extracellular space, inhibits the activation of microglial cGAS-STING signaling, eliminates the pro-inflammatory cytokine storm, and reverses CIRI neuroinflammation. Ultimately, MSNO effectively reduces neuronal damage and death through this triple effect (Fig. 1c). Our evidence shows that MSNO holds a strong efficacy for CIRI treatment. Even at an ultra-low dose (0.5 mg/kg), MSNO can effectively reverse CIRI. In addition, MSNO has excellent biocompatibility and biosafety and does not cause changes in circulatory blood pressure. Therefore, MSNO provides a paradigm for effective target therapy of CIRI and has broad clinical application prospects in CIRI.

Fig. 1. MSNO improving CIRI.

a Physicochemical properties of MSNO. The surface of MSNO was replaced by -SNO, which could efficiently scavenge ROS and achieve stable release of NO. b MSNO was administered through intravenous injection and targeted to the cerebral ischemic area through the capillary gap in the cerebral ischemic area. c MSNO could target the CIRI area of the brain, inhibit mitochondrial damage by inhibiting Ca2+ influx and clearing mtROS, and synergistically inhibit ERS and the inflammatory environment to improve CIRI. Some of the drawing materials for Scheme a–c were downloaded from BioRender.com and are released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs International license.

Results

Characterization of MSNO

The S in common MoS2 is inert and cannot be used to prepare MSNO. In our previous work, we prepared a defect-rich MoS2 (MS)27, in which the S at the defect edge of MoS2 can be converted to -SH under acidic conditions, which provides us with the possibility of preparing a new type of MSNO. To this end, we designed an elaborate method to prepare MSNO, whereby the edge S (Sedge) was converted to -SH under acidic conditions, and then nitroso groups were further introduced with NO2- on the MS surface to obtain MSNO (Fig. 2a). In order to verify our hypothesis, we first used density functional theory (DFT) to calculate the theoretical feasibility of the MSNO formation reaction. We calculated the adsorption energy of *NO2 on the Sedge and the S sites on the MoS2 plane (Splane). As shown in Fig. 2b, the energy barrier for *NO2 adsorption at the Splane is as high as 1.75 eV, indicating that *NO2 cannot be adsorbed at the Splane. As a strong contrast, the adsorption energy of *NO2 on the Sedge is −1.87 eV, indicating that *NO2 can easily bind to the Sedge. Therefore, the adsorption of *NO2 on the Sedge is a strong chemical adsorption, in which the N atom of the *NO2 and the Sedge form an N-S bond with a bond length of 1.99 Å (Supplementary Fig. 1). In order to further investigate the changes in charge density on *NO2 and Sedge before and after adsorption, we performed differential charge density calculations on the *NO2 adsorption structure on the Sedge. As shown in Fig. 2c, after *NO2 was adsorbed on the Sedge, the charge density near the adsorption site of *NO2 and the Sedge changed significantly compared with the area far away from the adsorption site, indicating that there is a strong interaction between the Sedge and *NO2. In order to further investigate the electron gain and loss and electron transfer direction on the Sedge and *NO2, we quantified the electrons on the Sedge and *NO2 before and after adsorption by bader charge. When *NO2 is adsorbed on the Sedge, the electrons on MoS2 are transferred to the *NO2, and the number of electrons transferred is 0.2 e. We use the partial density of states (PDOS) to analyze the valence bonds and molecular orbitals of *NO2 and *NO2 adsorbed to the Sedge site. As shown in Fig. 2d, the peak at −10.4 eV indicates that O2s, 2p, and N2s orbitals hybridize to form 4σ bonds in free *NO2. The peak at −7.7 eV can be attributed to the π bonds formed by the hybridization of O 2p and N 2p. In particular, the two peaks at −3.2 and −2.8 eV of the partial density of states of O in *NO2 belong to non-bonding orbitals. The highest occupied orbital HOMO at the Fermi level (0 eV) can be attributed to the 3π* antibonding orbital. The peak at 2.4 eV can be attributed to the 5σ* orbital formed by the hybridization of O 2p and N 2p empty orbitals. Notedly, there are unfilled empty orbitals on the 3π* antibonding orbital of *NO2, which is beneficial for the binding of N and Sedge. This is also confirmed by the results of differential charge density (Fig. 2c). When *NO2 is adsorbed to the Sedge site, the energy of the 3π* antibonding orbital decreases to below the Fermi level after gaining electrons, thus confirming that the adsorption of *NO2 on the Sedge site is thermodynamically favorable, which is consistent with the results of the adsorption energy. DFT was further used to calculate the Gibbs free energy of synthesis reaction of MSNO (Fig. 2e). The Gibbs free energy was calculated as ΔG = ΔE + ΔEZPE − TΔS, where the ΔE, ΔEZPE, and ΔS are electronic energy, zero-point energy, and entropy difference between products and reactants. Under acidic conditions, the Sedge forms -SH, which spontaneously combines with NO2- to form *NO2. The adsorption of *NO2 at the Sedge is a spontaneous (exothermic) process with a negative Gibbs free energy change (ΔG = −1.23 eV), indicating the existence of spontaneous binding between *NO2 and the Sedge sites in MoS2. Subsequently, *NO2 is further converted to *NOOH, which has a low energy barrier ΔG value (0.75 eV). Finally, the conversion of Ssite *NOOH to *NO is also a spontaneous process with a fairly negative value (ΔG value of −2.3 eV), indicating that the reaction releases a large amount of heat. Notedly, *NO in the Sedge of MoS2 can transfer to the Mo edge site (Moedge) to form Mo-NO with a low energy barrier (only 0.45 eV), which greatly increases the NO binding sites in MSNO and provides the possibility for the NO controlled release of MSNO. Finally, both NO at the Sedge and Moedge have low energy barriers for releasing NO, with ΔG being 0.53 eV and 0.09 eV, respectively, indicating that the release of NO can be a spontaneous process. Through DFT, we confirmed that the Sedge can form MSNO, and it is possible for the NO at the S site to transfer to the Mo site.

Fig. 2. Synthesis and characterization of MSNO.

a Images of the steps in MSNO synthesis. b Adsorption energy of *NO2 on the Splane and the Sedge of MoS2. c Charge density difference of *NO2 adsorption structure on MoS2 Sedge. d PDOS to analyze the valence bonds and molecular orbitals of *NO2 and *NO2 adsorbed to the Sedge site. e The free energy from the synthesis of MSNO to the release of NO by MSNO was calculated using DFT. f FTIR spectra of MSNO and MS. g Mo3p + N1s XPS spectra of MS and MSNO. h S2p XPS spectra of MS and MSNO. i TEM visualization of MSNO. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 50 nm and 5 nm. j Hydrodynamic diameter of MSNO. k NO release behavior of MSNO and GSNO at the same dose (1 mg/mL). l Scavenging ability of MSNO for O2.-. m ONOO- generation ability of GSNO, GSNO + O2.-, MS + O2.-, MSNO + O2.-, NAC + O2.-. n Scavenging ability of MSNO for ·OH. Data were expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3 independent experiments). Statistical significance was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test (ns: P > 0.05). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Some of the drawing materials for Fig. 1a were downloaded from BioRender.com and are released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs International license.

We further experimentally verified the feasibility of MSNO. MS was prepared according to our previous synthesis method, and then MSNO was synthesized by the method in Fig. 2a, and commercially purchased MoS2 (C-MS) was used as a control. Through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), C-MS is a flake-like structure (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) showed that the valence and composition of Mo and S in C-MS had no changed before and after the reaction (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that MSNO cannot be prepared using C-MS as raw material. This is consistent with our DFT calculations, because conventional MoS2 lacks Sedge, while Splane is inert to *NO2, resulting in the inability of the MSNO formation reaction to proceed. Further high-resolution TEM showed that the plane of C-MS has a flat and flawless crystal structure with almost no defects (Supplementary Fig. 3c). TEM and SEM of MS showed that MS presented a flower-like structure composed of flake-like MoS2 (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). High-resolution TEM revealed that there are a large number of defects on the sheet (Supplementary Fig. 4c), which make MS rich in Sedge sites, providing opportunities for the formation of MSNO. We then characterized the generated MSNO in detail. Subsequently, the generated MSNO was subjected to a series of characterizations to verify the successful preparation of MSNO. Both MSNO and MS contain stretching vibrations of Mo-S at 591 cm-1 and 932 cm-1 through fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Different from MS, MSNO had characteristic peaks at 695 cm-1 and 1576 cm-1, which are attributed to the stretching vibrations of S-N and N= O (Fig. 2f), respectively. By XPS, MSNO has a unique N element relative to MS (Supplementary Fig. 5), and also contains Mo and S consistent with MS. Through the fine XPS of N1s, the N1s of MSNO are mainly attributed to the N-O bond at 401.7 eV and the Mo-N bond at 398.8 eV (Fig. 2g). We verified whether N in -SNO can coordinate with Moedge by DFT, and found that N in -SNO cannot coordinate with Moedge. Therefore, Mo-NO is likely to be the conversion of -SNO to Mo-NO (with a low energy barrier of 0.45 eV) mentioned in the above DFT calculation. The existence of Mo sites provides a large number of bind sites for NO, which holds a guarantee for the controlled release of NO in MSNO. Moreover, the S-H bond of MSNO located at 164.2 eV is significantly reduced compared to that of MS through the S2p fine XPS peak (Fig. 2h), suggesting that -SH was successfully converted to -SNO in the preparation of MSNO and abundant nitroso groups were modified in MSNO. In addition, consistent with MS, the Mo element in MSNO appears as Mo4+ through the Mo3d XPS fine peak, indicating that the introduction of nitroso groups does not affect the valence state of Mo in MSNO (Supplementary fig. 6). The surface potential of MSNO was −16.8 mV through Zeta potential measure, slightly higher than −23.4 mV of MS (Supplementary Fig. 7). Despite this, MSNO still maintains a high negative charge, indicating that MSNO can circulate in the blood circulation system for a long time28. Through TEM and SEM, similar to MS, MSNO is a three-dimensional flower-like structure with an average particle size of about 80 nm formed by the combination of many nanosheets (Fig. 2ileft and Supplementary Fig. 8). Through high-resolution TEM, the nanosheets of MSNO were observed to be derived from the (002) crystal plane of MoS2 with an interlayer spacing of 6.25 Å (Fig. 2iright). Furthermore, X-ray diffraction (XRD) revealed that MSNO and MS had a typical two-dimensional layered structure of MoS2, indicating that the introduction of nitroso groups did not affect the lattice structure of MSNO (Supplementary Fig. 9). The hydrodynamic average particle sizes of MS and MSNO are 83.63 nm (Supplementary Fig. 10) and 84.49 nm (Fig. 2j), respectively, which is similar to the TEM results, indicating that MS and MSNO can remain stable in aqueous solution due to their high negative charge.

The controlled release of NO and the prevention of its conversion into ONOO- are two keys to the treatment of CIRI with NO. As shown in Fig. 2k, NO was completely released from GSNO (1 mg/mL) in just 10 min, indicating that GSNO exhibited burst NO release behavior. In a stark contrast to GSNO, MSNO (1 mg/mL) slowly released NO over a period of 120 h because the coordination bond between NO and Mo in MSNO greatly slow down the self-splitting rate of -SNO in aqueous solution. We noticed that the NO release curve of MSNO showed an approximate linear correlation between NO concentration and time in the first 24 h (Fig. 2kinsert), indicating that MSNO has a controllable NO release behavior and the steady state of NO concentration can be easily maintained by optimizing the dose of MSNO. We analyzed the N1s of MSNO after the NO release was completed. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, the MSNO no longer contained the N1s fine peak after 7 days of NO release, indicating that N-O and Mo-N disappeared after NO was completely released. Moreover, MSNO inherited the potent O2.- scavenging ability of MS, with pseudo-SOD activity as high as 105 U/mg (Fig. 2l and Supplementary fig. 12). The conversion of NO (released from GSNO and MSNO) to ONOO- was further explored in the presence of O2.- to simulate the pathological conditions of ROS burst in CIRI lesions. The GSNO group produced a large amount of ONOO- in the pyrogallol red assay, while the MSNO group produced significantly less ONOO- than the GSNO group, only 1/22 of that of the GSNO group (Fig. 2m and Supplementary Fig. 13). In addition, MSNO inherited the high scavenging ability of MS for ·OH (Fig. 2n and Supplementary Fig. 14) and H2O2 (Figure Supplementary Fig. 15). In addition, we compared the antioxidant activity of MSNO with that of N-Acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), a clinically approved antioxidant drug for the treatment of CIRI. NAC has similar ONOO- (Fig. 2m and Supplementary Fig. 13) and ·OH scavenging abilities (Fig. 2n and Supplementary Fig. 14) to MSNO, but it cannot directly scavenge O2.- (Figure Supplementary Fig. 12) and H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 15), indicating that the antioxidant activity of MSNO is significantly superior to that of NAC. The above evidence fully proved that MSNO was successfully prepared, and MSNO had the characteristics of controlled release of NO and avoiding NO conversion into highly toxic ONOO-.

MSNO targets CIRI lesions and releases NO stably

In CIRI, the BBB is affected by ROS burst, proinflammatory cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), etc., and the tight junctions of capillary endothelial cells and the integrity of the basement membrane are destroyed29 (Fig. 3a), which provides the opportunity for the specific enrichment of MSNO in the CIRI lesions. The rat CIRI model was established by simulating cerebral ischemia via middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), and removing the intraluminal filament that blocked the middle cerebral artery 2 h after ischemia to restore blood supply for 24 h to simulate the reperfusion phase (Fig. 3b). Compared with the Sham group, the vascular endothelial cells were significantly swollen, the tight junctions and basement membrane integrity were lost in the brain tissue of the I/R group through TEM of brain capillaries after 24 h of I/R (Fig. 3c). As a result, the BBB was opened in CIRI lesion, and the average size of the gap was about 120 nm (Fig. 3d), which provided an opportunity for smaller MSNO (about 85 nm) to penetrate the gap in the BBB and target CIRI lesions with high specificity. MSNO was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) to further explore the biodistribution of MSNO in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 16). FITC-MSNO was administered by sublingual intravenous injection before the start of reperfusion, and the distribution of MSNO was analyzed 1 h after administration. As shown in Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 17, for the Sham group, MSNO was mainly distributed in the liver and kidney, almost not distributed in the brain tissue of the Sham group and healthy brain tissue of the I/R group, because the BBB of the healthy brain tissue prevented the entry of MSNO. In contrast, MSNO could specifically target to the CIRI lesions only 1 h after intravenous injection, and the fluorescence intensity of FITC-MSNO in the CIRI lesions of the I/R group was 27 times higher than that of the Sham group. The distribution dynamics of MSNO was further determined by detecting the content of Mo element with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). As shown in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 18, MSNO could achieve targeted distribution in ischemic brain tissue 1 h after intravenous injection and reached a peak at around 6 h (25 times that of the Sham group), and then the content gradually decreased, indicating that MSNO could target ischemic brain tissue and be degraded. These evidences fully confirm that MSNO can specifically target CIRI tissue and is biodegradable.

Fig. 3. MSNO targets I/R brain tissue with high specificity and released NO stably. a) Figures of BBB damage during CIRI.

b MCAO model diagram. c TEM image of brain tissue capillaries. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 500 nm. d Statistical diagram of capillary endothelial gap in I/R brain tissue. e Representative images of bright field and fluorescence imaging of the brain, heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney of rats in the Sham group and I/R group 1 h after FITC-MSNO injection. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 2 mm. f ICP-MS was used to detect the content of Mo in brain tissue of the Sham group and I/R group at different time points after intravenous injection of MSNO. g, h Representative images (g) and quantitative statistics (h) of NO levels in cerebral infarction areas at different time points detected by small animal imaging technology. Scale bar: 3 mm. i, j Representative images (j) and quantitative statistics (i) of brain tissue ONOO- levels. Scale bar: 100 μm. k, l Changes of systolic (k) and diastolic (l) blood pressure over time in SD rats after administration of equal doses of GSNO and MSNO. Data were expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3 animals per group). Statistical significance was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test (ns: P > 0.05). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Some of the drawing materials for Fig. 2a–b were downloaded from BioRender.com and are released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs International license.

The NO level in the MSNO group was further analyzed by NO-specific (DAF-FM DA probe)30, with GSNO and MS as controls. In the MSNO group, NO was only distributed in the I/R brain tissue (right side of the yellow line) and maintained a relatively stable NO concentration after 1 h, but was not distributed in the non-I/R brain tissue (left side of the yellow line) (Fig. 3g, h). Different from the MSNO group, in the GSNO group, the NO concentration in the non-I/R brain tissue was higher than that in the I/R brain tissue at 15 min. This interesting and diametrically opposed phenomenon is rooted in the different physicochemical properties of MSNO and GSNO and the pathological characteristics of the BBB at CIRI. MSNO, as a large-sized nanodrug, tends to be enriched in CIRI lesion through the damaged BBB gap. While the distribution of GSNO is closely related to the amount of blood perfusion because GSNO is a small molecule. The blood supply of healthy brain tissue is better than that of CIRI lesions, and accordingly, the level of NO of the CIRI lesions is lower than that of healthy brain tissue in the GSNO group. In addition, NO disappears quickly in the GSNO group due to the short half-life of GSNO in vivo. Preventing the conversion of NO to ONOO- is important for the treatment of CIRI. As shown in Fig. 3i, j, ONOO- was significantly increased in the I/R and GSNO groups through the 3-nitrotyrosine probe, which were 6.21 times and 6.67 times higher than those in the Sham group, respectively. MS and MSNO could significantly reduce ONOO- levels because of their powerful ROS scavenging abilities. Exogenous NO donors may cause fatal hypotension if the NO concentration in the blood is too high. As shown in Fig. 3k, l, GSNO caused a “cliff-like” drop in blood pressure in the GSNO group within 15 min, with both systolic and diastolic blood pressure reduced to only half of normal blood pressure, indicating that the rapid release of NO after GSNO injection triggered a rapid increase in NO concentration in the blood. On the contrary, MSNO did not have a significant impact on systemic blood pressure due to the strong targeting ability to CIRI lesion and the controllable release of NO. The above evidence fully proved that MSNO can target CIRI lesion with high specificity and can stably release “pure NO” for treating CIRI by eliminating high levels of ROS.

MSNO effectively improves CIRI

The therapeutic effect of MSNO on CIRI was further investigated. Thanks to the controlled release of NO from MSNO, the best therapeutic effect of MSNO can be achieved by optimizing the dose of MSNO. Different doses of MSNO were injected sublingually before reperfusion, and the therapeutic effect of MSNO was evaluated through infarct size assessment and neurological scores 24 h after reperfusion (Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, even at ultra-low therapeutic doses, MSNO could significantly reduce the area of cerebral infarction through triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining, and the efficacy increased in a dose-dependent manner. In particular, at the optimal dose (0.5 mg/kg), the area of cerebral infarction treated with MSNO was reduced to 7.89%, far lower than the 44.58% in the I/R group (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 19). Correspondingly, MSNO at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg could restore the neurological function of rats to the level close to that of the Sham group through the Zealonga neurological function score (Figure Supplementary Fig. 19). Subsequently, the efficacy of MSNO was further compared with that of MS, the clinically approved antioxidant drug NAC, and the traditional NO donor GSNO at the 0.5 mg/kg dosage. As shown in Fig. 4c, d, the infarct area in the MSNO group was the smallest, much smaller than that in the MS group, NAC group, GSNO group, and I/R group. MS also has a certain therapeutic effect on CIRI due to its strong ROS scavenging ability, but the efficacy is significantly lower than that of MSNO. However, as we expected, NAC and GSNO at equal doses could not significantly improve CIRI. The main reason why NAC does not produce an effect is that it not only lacks target to damaged brain tissue, but also has lower antioxidant properties than MSNO. The main reasons why GSNO has no therapeutic effect are due to three aspects. First, it lacks target to damaged brain tissue and is more likely to be distributed in non-damaged brain tissue. Second, it lacks the ability to stably and continuously release NO. Third, it has no ROS scavenging ability, and the released NO is easily oxidized by excessive O2.- into more toxic ONOO-. Neurological scores also confirmed that MSNO had a therapeutic effect far exceeding that of MS, NAC, and GSNO (Fig. 4e). The damage of neurons was evaluated in different groups by specific Nissl staining. As shown in Fig. 4f, the number of Nissl staining spots (Nissl bodies) was significantly reduced, and the shape shrank from regular tiger-striped circles to irregular dots or vacuoles in the CIRI lesions of the I/R group. Treatment with MS and MSNO improved the number and morphology of Nissl bodies, and the therapeutic effect of MSNO was significantly better than that of MS. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining also demonstrated that MSNO treatment could significantly improve brain tissue structure (Fig. 4g). The above evidence fully proves that MSNO has a strong therapeutic effect on CIRI, and the effect is far better than that of MS, GSNO and NAC, suggesting that the efficacy of MSNO comes from its high CIRI lesion targeting, ROS scavenging and controllable and precise release of NO.

Fig. 4. MSNO effectively improves CIRI.

a Flow chart of MSNO efficacy study in CIRI. b Quantitative statistics of TTC staining in CIRI rats with different doses of MSNO. c, d Representative images (c) and quantitative statistics (d) of TTC staining of CIRI rat brain tissues treated with NAC, GSNO, MS, and MSNO at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg. e Neurological scores of CIRI rats treated with NAC, GSNO, MS, and MSNO at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg. f Representative Nissl staining images of rat brain tissues from different treatment groups (Red arrows mark atrophic neurons, and black arrows mark tissue vacuolization). Scale bar: 100 μm and 20 μm. g Representative HE staining images of brain tissues in different treatment groups. Scale bar: 100 μm. h Schematic diagram of long-term neurological deficit test. i) Mean mNSS scores of rats in different treatment groups during the treatment period. Higher scores indicate more severe damage. j, k Adhesive tests evaluate rat behavior, including the first time rats spend in contact with the tape (j) and the time it takes to successfully remove the tape (k). l Cylinder test to assess the asymmetry of forelimb use in rats. m Corner turn test result. n Rotarod test result. o On the 14th day after I/R, the Barnes maze test was performed to detect the time it took the rats in different treatment groups to find the right hole. p Body weight changes of rats in different treatment groups within 14 days. q Survival rate. r Brain water content in the infarcted hemisphere measured by the dry-wet gravimetric method. s Expression of tight junction proteins in damaged brain tissue after 1 day of I/R. Data were expressed as mean ± SE (Fig. 3a–r, n = 6 animals per group; Fig. 3s, n = 3 animals per group). Statistical significance was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test (ns: P > 0.05). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Some of the drawing materials for Fig. 3a were downloaded from BioRender.com and are released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs International license.

Next, we evaluated the restorative effects of MSNO on long-term neurological deficits in I/R rats31,32(Fig. 4h). Firstly, the modified neurological severity score (mNSS) was used to evaluate the neurological recovery after I/R in rats of different treatment groups, mainly including the motor, sensory, reflex and balance neurological functions of rats. As shown in Fig. 4i, the sensorimotor function of rats after I/R was severely impaired, with an average mNSS of approximately 13 points. In a sharp contrast, the neurological deficits of rats in the MS and MSNO treatment groups were significantly reversed over time after surgery, and the mNSS of the MSNO treatment group on the 14th day was close to that of the Sham group, with significantly better efficacy than that of MS. In addition, consistent with the in vivo efficacy results, the NAC and GSNO treatment groups did not significantly improve the mNSS of I/R rats. Subsequently, we further evaluated the neurological function of rats in different treatment groups through behavioral tests reflecting the sensorimotor and cognitive functions of the nervous system, including the adhesive test, cylinder test, corner turn test, rotarod test, and barnes maze test. The adhesive test was used to evaluate the tactile response and sensorimotor function of rats. As shown in Fig. 4j-k, the tactile response and sensorimotor function of rats in the I/R group were severely impaired, and the time to touch/remove the tape was significantly longer than that in the Sham group. Consistent with the expected results, the time to touch/remove the tape in the MS and MSNO treatment groups gradually decreased with the passage of time after surgery, and the efficacy of MSNO was significantly better than that of MS. The cylinder test was used to test and evaluate the asymmetry of forelimb use in rats. As shown in Fig. 4l, the asymmetry rate of forelimb used in rats in the I/R group was significantly higher than that in the Sham group. The asymmetry rate of forelimb used in rats in the MS and MSNO treatment groups gradually improved over time after surgery, and the efficacy of MSNO was significantly better than that of MS. The corner turn can measure the sensorimotor impairment of rats through unilateral dopaminergic system damage. As shown in Fig. 4m, the percentage of right turns in rats in the I/R group was significantly reduced, and this phenomenon was significantly improved after treatment with MS and MSNO, and the therapeutic effect of MSNO was significantly better than that of MS. The rotarod test was used to test the motor function of rats. As shown in Fig. 4n, compared with the I/R group, the time that rats in the MS and MSNO groups stayed on the rotarod increased significantly over time. On the 14th day, the time that rats in the MSNO treatment group stayed on the rotarod was close to that of the Sham group, and the therapeutic effect was significantly better than that of MS. The Barnes maze test was used to test the long-term spatial cognitive function of I/R rats. The results are shown in Fig. 4o and Supplementary Fig. 20. Compared with the MS group, the time taken by the MSNO groups to find the correct hole was significantly reduced, indicating that MSNO treatment is beneficial to improve the long-term cognitive function of I/R rats. The above results showed that MSNO treatment promoted the long-term neurological recovery of I/R rats, and its therapeutic effect was significantly better than that of MS. In addition, it is worth noting that the NAC-treated group and the GSNO-treated group also did not show significant improvement in neurobehavioral tests, because NAC and GSNO at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg could not improve CIRI. Body weight changes can also show the recovery of rats with I/R injury. As shown in Fig. 4p, the body weight of rats dropped sharply after I/R, and the rats in the MS and MSNO groups could gradually recover their body weight 5 days after surgery, and the recovery speed of MSNO was better than that of MS, which once again confirmed the significant therapeutic effect of MSNO. At the same time, MS and MSNO treatment significantly prolonged the survival rate of I/R rats. The survival rate of rats in the MS group was 83% within 14 days, and the survival rate of rats in the MSNO group was 100%, while I/R rats could not survive for more than 8 days, GSNO group rats could not survive for more than 10 days, and NAC group rats could not survive for more than 11 days (Fig. 4q). Subsequently, we evaluated the brain edema of rats in each treatment group. As shown in Fig. 4r, MSNO significantly inhibited I/R-induced brain edema, and the water content of brain tissue was close to that of the Sham group. The above results reveal the potential role of MSNO in the long-term recovery of neurological function and prolonged survival rate after I/R. Since NAC and GSNO did not produce therapeutic effects in the above experiments, they will not be explored in subsequent experiments.

Finally, to further explore the regulatory effect of MSNO on the BBB of I/R-injured brain tissue, we analyzed the damage to the BBB in the lesion brain tissue of rats in each treatment group. We detected the expression level of tight junction proteins (including Claudin-5, Occludin, and ZO-1 proteins) in the brain tissue of rats on the 1st and 7th day after I/R surgery by western blotting (WB) method. As shown in Fig. 4s and Supplementary Fig. 21, on the 1st day after I/R surgery, the expression level of tight junction proteins in the injured brain tissue of rats in the I/R group, MS treatment group, and MSNO treatment group was significantly reduced, which was consistent with our previous results, confirming the BBB damage of ischemic brain tissue after I/R, and providing a way for MS and MSNO to specifically target ischemic brain tissue. However, it is worth noting that with the extension of postoperative time, the levels of tight junction proteins in the brain tissues of rats in the MS group and MSNO group were significantly upregulated compared with those in the I/R group on the 7th day, and the expression level of tight junction proteins in the brain tissues of rats in the MSNO group was significantly higher than that in the MS group (Supplementary Fig. 22). In addition, CD31 staining results also showed that the number of endothelial cells in the brain tissue of rats in the MS group and MSNO group on the 7th day was significantly increased compared with that in the I/R group (Supplementary Fig. 23), indicating that the BBB of I/R-damaged brain tissue can be gradually repaired with the therapeutic effects of MS and MSNO on CIRI, and the effect of MSNO is better than that of MS.

Transcriptome analysis

To further investigate the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of MS and MSNO on CIRI, transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis was performed on brain tissues from rats in the Sham group, I/R group, MS treatment group, and MSNO treatment group. Firstly, VENN/UpSetR analysis was employed to compare the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among the groups. As shown in Fig. 5a, 8419 DEGs were identified between the I/R group and the Sham group, indicating that I/R induced widespread transcriptomic disturbances. In contrast, the number of DEGs between the MS treatment group and the Sham group was significantly reduced to 4530. Remarkably, the number of DEGs between the MSNO treatment group and the Sham group was further substantially decreased to 477. These results demonstrate that the MS carrier itself effectively alleviates I/R-induced transcriptomic abnormalities, while the nitrosylated derivative MSNO exhibits superior regulatory capability, with a therapeutic efficacy significantly surpassing that of MS. Subsequently, to directly evaluate the ameliorative effects of MS and MSNO on I/R injury, we further analyzed DEGs between the MS group and the I/R group, as well as between the MSNO group and the I/R group, using volcano plots (|log₂FC | ≥ 1, Qvalue ≤ 0.05). As shown in Fig. 5b-c, compared to the I/R group, the MS group exhibited 2924 upregulated and 2351 downregulated genes. In contrast, the MSNO group demonstrated a more pronounced regulatory amplitude, comprising 4034 upregulated and 3937 downregulated genes. This result reconfirmed that MSNO possesses a significantly stronger capacity than MS to reverse I/R induced gene expression dysregulation. Furthermore, to directly investigate the mechanistic differences introduced by the S-nitrosylation modification (-SH to -SNO), we analyzed DEGs between the MSNO group and the MS group. The results revealed 1456 upregulated and 1924 downregulated genes in the MSNO group compared to the MS group (Fig. 5d). This directly demonstrates that MSNO exhibits a significantly distinct mode of action at the molecular level compared to MS, providing molecular level evidence for its enhanced therapeutic efficacy. Subsequently, gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of DEGs between the MS and I/R groups, and between the MSNO and I/R groups, revealed six core processes primarily involved in their improvement of CIRI: calcium channel regulation, inflammatory response, mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS), and apoptosis. Notably, within these key pathological processes, the MSNO group exhibited a more significant reversal effect on gene expression regulation compared to the MS group, with the improvement in calcium channel regulation being the most prominent (Fig. 5eand Supplementary Fig. 24). Visualization of the DEGs associated with these six processes using clustered heatmaps further demonstrated this finding. As shown in Fig. Supplementary Fig. 24, compared to the Sham group, the I/R group exhibited significantly altered gene expression related to calcium channel regulation, inflammatory response, mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS), and apoptosis. Fortunately, both MS and MSNO significantly reversed the aberrant expression of DEGs in these six biological processes induced by I/R. Furthermore, compared to the MS group, the gene expression profile in the MSNO group more closely resembled that of the Sham group. Finally, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was employed to further elucidate the target pathways of MS and MSNO. Compared to the I/R group, the DEGs in both the MS and MSNO groups were significantly enriched in key signaling pathways aberrantly activated in CIRI, including calcium signaling related pathways, mitochondrial damage-related pathways (involving endoplasmic reticulum function, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, and apoptosis), and inflammation-related pathways (such as the cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway, TNF signaling pathway, and NF-κB signaling pathway) (Fig. 5f). Consistent with our expectations, MSNO demonstrated significantly greater efficacy than MS in suppressing the activation of these pathogenic pathways. In summary, the transcriptomic analysis system of this study showed that the MS has a fundamental role in improving CIRI-related transcriptome disorders, and nitrosylation modification gives MSNO (-SNO) significantly enhanced biological functions, making its efficacy in key pathological links such as reversing calcium overload, inhibiting inflammatory storms, and protecting mitochondrial function better than unmodified MS (-SH).

Fig. 5. Transcriptomic analysis.

a VENN/UpSetR graphical analysis showing DEGs among the Sham group, I/R group, MS-treated group, and MSNO-treated group. b Volcano plot depicting DEGs determined between MS group and I/R group brain tissue. c Volcano plot depicting DEGs determined between MSNO group and I/R group brain tissue. d Volcano plot depicting DEGs determined between MSNO group and MS group brain tissue. e GO enrichment analysis of biological processes involved in DEGs between the MSNO-treated group and the I/R group, and the MSNO-treated group. f KEGG pathways enrichment analysis of DEGs in the MS/MSNO-treated group versus the I/R group. Data were expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3 animals per group). Statistical significance was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Source data has been deposited at Sequencing Read Archive (PRJNA1308594).

MSNO inhibits mitochondrial damage in neurons

Glutamate accumulation-induced neuronal Ca2+ overload is the initiation of neuronal apoptosis and the key to mitochondrial damage in CIRI33. NO can reduce Ca2+ influx by nitrosylating the redox sites on the NMDAR in neurons34. In vitro, SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) to simulate the CIRI process, and then the intracellular Ca2+ concentration of different groups was detected by Fluo-4 AM. The optimal drug concentration of MSNO was screened by CCK8 (Supplementary Fig. 25). As shown in Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 26, the intracellular Ca2+ level in the H/R group was 3.45 times that of the Normoxia group, indicating H/R caused severe Ca2+ overload in SH-SY5Y cells. After MSNO treatment, the intracellular Ca2+ level was reduced to a level close to that of the Normoxia group, and the effect was much better than that of MS. Flow cytometry also showed that MSNO could eliminate the Ca2+ overload caused by H/R, and the effect was better than MS (Supplementary Fig. 27). These results suggest that MSNO can more effectively prevent H/R-induced calcium overload than MS that can only scavenge ROS. In addition to Ca2+ overload, ROS burst is a key factor leading to neuronal mitochondrial damage in CIRI. Through flow cytometry, after H/R, the percentage of DCFH-DA-positive cells increased from 4.08% to 64.07%, and decreased to 7.53% and 6.39% with MS and MSNO treatment, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 28), indicating that MSNO and MS can effectively eliminate the ROS burst caused by H/R. The main source of ROS is neuronal mitochondria, and the target of MSNO to mitochondria is critical to for ROS elimination35,36. By co-labeling with Mito-tracker and FITC-MSNO, MSNO was confirmed to be highly efficient in targeting SH-SY5Y cells mitochondria under H/R, with a Pearson’s coefficient as high as 0.84 (Fig. 6b). H/R caused a 3.36-fold increase in mtROS in SH-SY5Y cells with MitoSOX red probe. As expected, MS and MSNO significantly reduced the level of mtROS induced by H/R in SH-SY5Y cells, and the mtROS level was close to that of the Normoxia group (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 29). This was also confirmed with flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 30). Excessive mtROS can lead to a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and cause mitochondrial dysfunction. As shown in Fig. 6dand Supplementary Fig. 31, after H/R treatment, the percentage of normal MMP in SH-SY5Y cells decreased from 100% to 4.39% through JC-1 probe, and the percentage of normal MMP in the MSNO treatment group was significantly recovered (80.26%). Combined with evidence from flow cytometry (Figure Supplementary Fig. 32), MSNO were confirmed to be able to effectively restore the MMP, and the therapeutic effect was significantly better than that in the MS group. Finally, MSNO effectively reversed the decrease in ATP production induced by H/R, and the effect was better than MS (Figure Supplementary Fig. 33), indicating that MSNO can effectively restore mitochondrial function damaged by H/R in SH-SY5Y cells.

Fig. 6. MSNO inhibits mitochondrial damage in neurons.

a Representative graphs of Ca2+ concentration in SH-SY5Y cells of different treatment groups. Scale bar: 200 μm. b Representative images and co-localization analysis of FITC-MSNO and mitochondria. Scale bar: 100 μm. c Representative images of mtROS (MitoSOX) in SH-SY5Y cells in each group. Scale bar: 100 μm. d Representative images of the integrity of MMP in each group of cells evaluated by JC-1 staining. scale bar: 100 μm. e–g TEM images of mitochondria in brain tissue neurons of the Sham group (e), I/R group (f), and MSNO group (g). Yellow arrows indicate mitochondria. Scale bar: 500 nm. Data were expressed as mean ± SE (In vitro: n = 3 independent experiments; In vivo: n = 3 animals per group). Statistical significance was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In vivo, the ROS level in the brain tissue of the I/R group increased to about 3.4 times that of the Sham group through dihydroethidium (DHE) probe, while the ROS levels in the CIRI lesions of the MS and MSNO groups were reduced to close to the level of the Sham group (Supplementary Fig. 34). ROS damages the lipids of the mitochondrial membrane to release malondialdehyde (MDA), and MDA reflects the degree of mitochondrial damage to a certain extent in CIRI37. As shown in Figure Supplementary Fig. 35, MSNO significantly reduced the CIRI-induced high level of MDA. TEM imaging of brain tissue was further adopted to visually demonstrate the protective effect of MSNO on neuronal mitochondria. As shown in Fig. 6e–g, the mitochondria of brain tissue neurons in the I/R group were severely damaged, showing swelling, dissolution, unclear ridges and even vacuolization, while the mitochondrial structure was significantly restored after MSNO treatment, providing direct evidence for the protection of mitochondria by MSNO. The above experimental evidences fully demonstrated that MSNO could effectively protect mitochondria from damage caused by overloaded Ca2+ and mtROS, and significantly restore mitochondrial function in CIRI.

MSNO reverses neuroinflammation

The inflammatory storm forms a vicious cycle with mtROS to aggravate neuronal damage and serve as an exogenous pathway for neuronal apoptosis in CIRI38,39. Transcriptome results indicated that inflammatory response played a key role in MSNO treatment of CIRI, and the mtDNA sensing pathway was considered to be a key target of MSNO in reversing neuroinflammation (Fig. 5e, f). In vivo, we adopted the DAPI/dsDNA/Tom20 co-staining to analyze the distribution of mtDNA in ischemic brain tissues of different groups. As shown in Fig. 7a, large amount of mtDNA was released from the damaged mitochondria in the CIRI lesions of the I/R group, while MSNO significantly reduced the release of mtDNA, and its therapeutic effect was significantly better than MS. Following neuronal death, mtDNA was released into the extraneuronal space and induced M1 polarization of glial cells40,41. Subsequently, the CIRI lesions of different groups were analyzed by M1 glial cell marker protein (iNOS) and M2 glial cell marker protein (CD206) co-staining immunofluorescence. Most of the microglia in the CIRI lesions were activated as M1 type. Surprisingly, the M1 phenotype of microglia decreased and the M2 phenotype increased in the MSNO group, indicating that MSNO can promote the transformation of microglia from the MI phenotype to the M2 phenotype (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Fig. 36). Subsequently, the positively stained cells of cGAS and STING in CIRI lesions of the I/R group increased significantly through immunohistochemical staining42, while MSNO significantly inhibited the activation of cGAS-STING (Fig. 7c, d), indicating that MSNO regulated microglial phenotypic transformation by inhibiting the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway. Finally, we analyzed the expression levels of key proteins of the cGAS-STING pathway in the CIRI lesions of each group by WB. The expression levels of cGAS, STING, and downstream molecules P-IRF3/IRF3 and P-P65/P65 in brain tissue of the I/R group were more than twice that of the Sham group, confirming that the cGAS-STING signaling pathway was significantly activated in CIRI. MSNO treatment significantly reduced I/R-induced high expression of cGAS and STING and phosphorylation of IRF3 and P65(Fig. 7e–g and Supplementary Fig. 37). Moreover, MSNO could significantly reduce the release of I/R-induced pro-inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) and increase the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors (IL-4 and IL-10) (Supplementary Fig. 38).

Fig. 7. MSNO reverses neuroinflammation.

a dsDNA/Tom20/DAPI immunofluorescence staining of the cerebral infarction area in each treatment group. White arrows indicate mtDNA. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 10 μm. b Immunofluorescence staining of iNOS (M1) and CD206 (M2) to detect the phenotype of microglia in the infarcted area. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 10 μm. c Immunohistochemical analysis of cGAS expression in cerebral infarction in each treatment group. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 50 μm. d Immunohistochemical analysis of STING expression in cerebral infarction in each treatment group. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 50 μm. e–g The expression levels of inflammation-related proteins in brain tissue homogenate were detected by WB and representative figures. Data were expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3 animals per group). Statistical significance was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In vitro, SH-SY5Y cells and microglia (BV2) were co-cultured to simulate the I/R brain tissue microenvironment in CIRI (Supplementary Fig. 39). Subsequently, the key protein levels of the cGAS-STING pathway were also verified in BV2 cells by WB. H/R-induced neuronal mtDNA release led to high expression of cGAS and STING and phosphorylation of IRF3 and P65 in in BV2 cells, while MSNO could reduce the expression of cGAS and STING and the phosphorylation of IRF3 and P65 in microglia (Supplementary Fig. 40), inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory factors, and promote the expression of anti-inflammatory factors (Supplementary Fig. 41). In summary, the mtDNA released by neurons can be quickly recognized by the dsDNA receptor cGAS in the microglial cell membrane, activating the downstream STING signaling pathway to cause a strong inflammatory response. MSNO inhibited the release of mtDNA by protecting mitochondria in neurons, significantly reduced the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in microglia to eliminate neuroinflammation, and ultimately decreased neuronal external apoptosis in CIRI (Supplementary Fig. 42).

MSNO improves ERS and inhibits neuronal apoptosis

The mtROS burst were often accompanied by ERS in CIRI because there is direct synapse-like contact between the ER and mitochondria43. Along with the destruction of neuronal mitochondria, the ER in neurons in the I/R group was significantly swollen through TEM (Fig. 8a, b), confirming that severe ERS was caused in neurons of CIRI. As a strong control, the edema of neuronal ER in the MSNO group was significantly improved, and its structure was similar to that in the Sham group (Fig. 8c), indicating that MSNO can effectively improve neuronal ERS in CIRI. Neurons are sensitive to the rate of protein synthesis, and mtROS leads to misfolding of neuronal proteins in CIRI44. Subsequently, the misfolded proteins bind to Bip on the ER and activate three ERS transmembrane molecules: inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inducing ERS and further promoting cell apoptosis45 (Fig. 8d). Specifically, PERK can phosphorylate eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF-2α) and increase the expression of transcription factors such as activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). ATF6 is transported to the Golgi apparatus, where it is cleaved by endopeptidases S1P and S2P to release cytoplasmic ATF6 fragments. ATF4 and ATF6 initiate the transcription of chop to promote neurons apoptosis. IRE1 activates the transcription factor X-box binding protein (XBP1) and catalyzes the apoptotic signaling pathway mediated by JNK and Caspase 12. To this end, we further verified the regulatory mechanism of MSNO on ERS by q-PCR. The expression of Bip was significantly increased in I/R brain tissues and H/R SH-SY5Y cells, indicating that ERS was triggered in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 8e and Supplementary Fig. 43). Subsequently, PERK, ATF6, IRE-1α were significantly activated (Fig. 8f and Supplementary Figs. 43, 44), and further stimulated the expression of downstream factors, including eIF-2α, ATF-4, Chop, XBP-1s, JNK, and Caspase 12 (Supplementary Fig. 43, 44). Thanks to the efficient mtROS elimination of MSNO, MSNO could inhibit ERS and almost completely reverse the activation of these pathways.

Fig. 8. MSNO improves ERS and inhibits neuronal apoptosis.

a–c TEM images of ER in brain neurons of rats in the Sham group (a) I/R group (b), and MSNO group (c). Yellow arrows indicate ER. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 250 nm. d Schematic diagram of the ERS and mitochondrial damage cascade. e, f q-PCR was used to detect the expression levels of ERS-related factors in the brain tissue, including Bip (e), PERK (f). g TUNEL staining of brain tissue. (n = 3, biological replicates). Scale bar: 50 μm. h The expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins in brain tissue homogenate were detected by WB. (n = 3, biological replicates). i Flow cytometry analysis of SH-SY5Y cells apoptosis in different treatment groups. Data were expressed as mean ± SE (In vitro: n = 3 independent experiments; In vivo: n = 3 animals per group). Statistical significance was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Some of the drawing materials for Fig. 7d were downloaded from BioRender.com and are released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs International license.

Neuronal apoptosis induced by mitochondrial damage and ERS together constitutes the intrinsic pathway of neuronal apoptosis46. Overloaded Ca2+ and mtROS induce mitochondrial damage, releasing the pro-apoptotic factor Cyt-C to induce neuronal apoptosis47. The apoptosis of CIRI lesions of different groups was analyzed by TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining. As shown in Fig. 8g and Supplementary Fig. 45, the apoptosis rate of brain tissue cells in the I/R group was as high as 74.75%, and the apoptosis rate (9.05%) in the MSNO treatment group was significantly reduced. The MS group had a certain effect (30.94%) but was worse than the MSNO group. Through WB, the expression levels of pro-apoptotic proteins Bax, cleaved-caspase3/caspase3 (C-Cas/Cas), and Cytosolic-Cytochrome C (C-Cyt C) in the I/R group were significantly increased to 3.89, 3.57, and 2.4 times that of the Sham group, and the expression of anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 was significantly reduced to 0.51 times that of the Sham group. MS and MSNO treatments could significantly reverse the expression of these proteins, and the therapeutic effect of MSNO was significantly better than that of MS (Fig. 8h and Supplementary Fig. 46). In vitro, the expression levels of pro-apoptotic protein Bax, C-Cas/Cas, and C-Cyt C in the H/R group were significantly increased, and the expression of anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 was significantly reduced. MSNO treatment could also significantly reverse the expression of these proteins caused by H/R in SH-SY5Y cells (Supplementary Fig. 47). Flow cytometry was further adopted to detect the effect of MSNO on improving H/R-induced SH-SY5Y cells apoptosis. After H/R induction, the apoptosis rate of SH-SY5Y cells was high to 39.81%, the apoptosis rate in the MS treatment group was reduced to 24.25%, and the apoptosis rate of cells in the MSNO treatment group was reduced to 12.30% (Fig. 8i and Supplementary Fig. 48), suggesting that MSNO could also effectively inhibit H/R-induced neuronal apoptosis in vitro. In summary, the above evidence fully demonstrates that MSNO can effectively alleviate ERS and significantly reduce neuronal apoptosis, and its effect is far better than MS which can only eliminate ROS. This further highlights MSNO’s ability to simultaneously eliminate ROS and provide pure and stable NO in the treatment of CIRI.

Biocompatibility of MSNO therapy

Currently, nanomedicine based on MoS2 has been widely used in biomedical research, and its biocompatibility has been fully verified48,49. In addition, Mo itself is an element necessary for the human body, and enzymes based on Mo are widely present in the body50. First, in vitro, the effect of MSNO on the viability of SH-SY5Y cells and BV2 cells was detected by CCK8. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 49, 50, even high concentrations of MSNO (64 μg/mL, 32 times the effective dose) had no effect on the viability of SH-SY5Y cells and BV2 cells. Subsequently, MSNO at a 10-fold therapeutic dose was injected into SD rats via the sublingual vein to further evaluate the safety of MSNO in vivo. As expected, MSNO did not cause significant changes in the morphology and structure of the major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and brain) of rats, whether 1 or 28 days after MSNO injection (Supplementary Figs. 51, 52). Moreover, the indicators related to liver and kidney function (Supplementary Figs. 53, 54) and blood routine examination (Supplementary Figs. 55, 56) were also within the normal range. The above results fully demonstrate that MSNO exhibits excellent biocompatibility and safety both in vivo and in vitro.

Discussion

Our work established not only a NO sustained-release system, but also a sophisticated and multifunctional collaborative system for CIRI treatment. We adopted a unique and portable synthetic procedure to covalently and coordinately bind the nitroso groups to MoS2 nanoplanes, ensuring a near-linear and smooth release of NO from MSNO within the critical initial 24 h that affected the CIRI process. Crucially, our MSNO holds the unique ability to coordinately drastically reduce ROS levels, providing pure NO at appropriate concentrations similar to the eNOS. Our innovation, with its elegant design, opens up a promising avenue to address the decades-long bottleneck of NO donors in the treatment of CIRI. Through the multiple beneficial effects of NO, MSNO can intervene in a variety of complex and mutually interfering pathologies that determine the progression of CIRI, achieving highly efficient and specific treatment of CIRI.

NO is an electrically neutral small gas molecule that can easily pass through biological membranes and even the BBB51. Moreover, NO does not rely on common receptor-ligand binding, but exerts its effects through nitrosation and coordination21. Therefore, NO has a wide range of definite beneficial protective effects in the field of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases14. Given the abundant evidences for NO-mediated neuroprotection after CI, a variety of NO-based therapeutic strategies have been developed for the treatment of CIRI, mainly involving two aspects. The first strategy is to increase eNOS activity or regulate the bioavailability of endogenous NO52, such as statins53, Rho kinase inhibitors54, and phosphodiesterase inhibitors55. However, their application in the treatment of CIRI is greatly limited because these drugs are usually difficult to accurately target CIRI lesions. For example, statins are usually recommended for primary and secondary prevention of stroke53. The second strategy is to provide additional NO donors, such as L-arginine56, transdermal nitroglycerin51, GSNO25, and sodium nitroprusside51. However, many NO donors cannot provide steady-state NO at the CIRI lesions and are prone to cause systemic hypotension. What’s worse, NO can be quickly oxidized and inactivated. Especially under high ROS levels, NO is easily converted into more toxic ONOO-. In fact, M1-polarized microglia usually produce high concentrations of NO through iNOS, which then combines with O2.- to generate ONOO-, causing severe oxidative damage to CIRI lesions. MSNO of specific nano-size is selectively enriched in CIRI lesions, and the concentration of NO is precisely manipulated to an appropriate concentration and to avoid the formation of ONOO-, which not only eliminates harmful effects such as systemic hypotension, but also produces multiple beneficial effects on the CIRI lesions.

CI is one of the most common diseases with great unmet medical needs in medicine, and developing effective treatments is a major medical challenge. Treatment of CI usually involves multiple aspects such as reducing neuronal death, stabilizing the BBB, restoring collateral circulation and protecting neuromotor function. In the future, NO will play a more important therapeutic role in CI based on its versatile characteristics. The next generation of NO-based therapeutics will enable seamless targeting of disease lesions and intricate resolution of the complex pathological responses of CIRI with unparalleled precision and efficiency. Based on the fundamental findings of this study, we propose that “eNOS-like” nanomedicines may rekindle the research enthusiasm for “NO therapy” and may resolve the problem of using NO as a target to treat ischemic diseases that has long plagued the medical community.

In addition, MSNO has good biosafety and biodegradability, so it has good prospects for clinical transformation. Our results showed that MSNO was mainly distributed in the liver and kidneys of Sham-operated rats, and its content began to gradually decrease after reaching a peak about 6 hours after injection, indicating that MSNO can be metabolized and excreted from the body through the liver and kidneys (Fig. 3e, fand Supplementary Fig. 17, 18). However, MSNO can target damaged brain tissue with high specificity in I/R rats. It is worth noting that the accumulation of MSNO in the injured brain tissue also gradually decreased after reaching a peak (Fig. 3e, fand Supplementary Figs. 17, 18), indicating that MSNO in the brain tissue can also be effectively cleared or degraded. Organic nanomaterials can be cleared from rat brain tissue via the paravascular lymphatic pathway (a system for removing solute waste from the brain)57. MSNO is modified by the organic substance sodium nitroprusside, so it may be cleared from the rat brain via the paravascular lymphatic pathway and ultimately excreted through the peripheral clearance system. In addition, the degradation pathways of MoS2 nanomaterials have been reported50,58. On the one hand, MoS2 can be gradually oxidized and degraded (especially in the acidic microenvironment of the cerebral infarction lesion) into molybdates, such as molybdate (MoO42-) and thiosulfate (S2O32-) ions. Next, cells can use molybdate ions to synthesize molybdenum cofactors (MOCO), such as molybdenum pterin and iron-molybdenum cofactors. At the same time, molybdate ions can also be excreted from the body through the kidneys. On the other hand, MoS2 can be oxidized by myeloperoxidase in the body or degraded by intracellular glutathione (GSH) through sulfur exchange reactions. Therefore, MSNO prepared based on the MoS2 carrier has good prospects for clinical transformation. In addition, it is worth noting that NO not only has great potential for improving CIRI. In fact, NO’s unique physical and chemical characteristics and biological functions give NO multiple application scenarios and play an important role in various diseases such as tumors, antibacterial, cardiovascular diseases, etc. In conclusion, MSNO is an emerging biomaterial, and research on many aspects of its interaction with biological systems is still ongoing. Based on the research results to date, this paper introduces the current role and mechanism of MSNO in improving CIRI. There is still a lot of room for research on the fate of MSNO in vivo, and future efforts will focus on this direction to evaluate the actual translational potential of MSNO in biomedical applications. Additionally, future studies are needed to evaluate and identify additional molecular mechanisms that are modulated by exposure to MSNO and to determine the role of individual nanoscale properties in regulating cellular behavior. Overall, MSNO provides a promising approach to the treatment of CIRI and opens up avenues for the treatment of other diseases.

Methods

Materials

A list of reagents used in this study is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Synthesis of MSNO

Small-particle MoS2 nanoflowers (MS) were prepared by hydrothermal method using ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate ((NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O) and thiourea (CN2H4S). Subsequently, S-nitroso (-SNO) groups were further introduced on the surface of MS to obtain NO-embedded MoS2 nanoflowers, named MSNO.

Synthesis of MS: (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O (18.5375 g) and CN2H4S (7.9925 g) were fully dissolved in 500 mL of deionized water and then transferred to an autoclave for reaction at 180 °C for 24 h. The reaction product was washed repeatedly with ultrapure water for 3 times to remove other impurities, and then centrifuged at 1000 g /4 min to obtain small particles of MS.

Synthesis of MSNO: MoS2 (0.5 g) and 0.1 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid were reacted at room temperature for 24 h. Subsequently, the system was transferred to an ice bath, 1 mL of NaNO2 (0.1 g/mL) was added, and the reaction was carried out in the dark for 7 h. The reaction product was repeatedly washed with ultrapure water for 3 times to obtain the final product, MSNO.

DFT computational detail

All DFT computations in this work were carried out using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP), employing the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method. The exchange–correlation effects were treated within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional. A Monkhorst Pack k-point grid of 2×2×1 was adopted for sampling the Brillouin zone in surface calculations. The plane-wave basis set cutoff was fixed at 500 eV. Geometry optimizations were conducted until the forces on all atoms were below 0.02 eV/Å and the total energy difference between successive steps was less than 1×10⁻⁵ eV. To suppress artificial interactions between periodic images, a vacuum spacing of 15 Å was introduced along the surface-normal direction. van der Waals interactions were incorporated via Grimme’s DFT-D3 method with zero damping.

The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) was evaluated as:ΔG = ΔE + ΔEZPE – TΔS, where ΔE represents the change in electronic energy, ΔEZPE is the difference in zero-point energy, and ΔS denotes the change in entropy.

Characterization of MSNO

TECNAI G2 high-resolution transmission electron microscope was used to photograph the morphologies of MS and MSNO. A laser particle size analyzer was used to measure the hydrodynamic diameters of MS and MSNO. XRD was measured using a Shimadzu X-ray diffractometer. XPS was measured using a MKII spectrometer. A Bruker Vertex 70 spectrometer (2 cm-1) was used for FT-IR determination of MS and MSNO.

In vitro NO release assay

NO detection kit (Biyuntian) was used to measure NO release in vitro. The NO released by MSNO and GSNO will be rapidly oxidized to generate NO2- in aqueous solution, which will undergo a diazo reaction with diazonium salt sulfonamide and then couple with naphthyl-vinyldiamine to generate a color product with a maximum absorption peak at 540 nm. 1 mg/mL MSNO solution (or GSNO solution) was placed in a 37 °Cwater bath, and 1 mL of sample was taken out at 0 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 2 d, 3 d, 4 d, and 5 d. The sample was filtered through a water filter to remove the effect of the drug’s own color on the absorbance determination. Griess I and Griess II were then added, and the absorbance at 540 nm was measured using an enzyme reader.

In vitro pseudo-SOD activity assay

The superoxide anion detection kit is used to simulate the xanthine and xanthine oxidase reaction system in the body to produce superoxide anions, and the reaction product shows a characteristic absorption peak at around 540 nm. When MS/MSNO/NAC was added to the reaction system, the characteristic absorption peak at 540 nm gradually decreased as superoxide anions were removed.

In vitro ONOO- production assay

The pyrogallol red method was used to detect the ability to generate ONOO-. Pyrogallol red has a characteristic absorption peak at 540 nm, while O2.- and ONOO- can reduce its absorption peak. Briefly, 0.1 M methionine (390 μL), 20 μM riboflavin (6 μL), 0.1 M (pH7.4) PBS (1.5 mL), and 1.1 mL ultrapure water were added to the cuvette in turn, mixed and exposed to ultraviolet light for 5 min to generate O2.-. Then, the solution in the cuvette was transferred to a centrifuge tube, and 24 μL (1mg/mL) of ultrapure water/GSNO/MS/MSNO/NAC were added, respectively. After being placed at 37 °C for 12 h, 10 uL of pyrogallol red solution was added, and the characteristic absorption peak of pyrogallol red at 540 nm was measured after reacting at room temperature for 20 min. The control sample was a solution of pyrogallol red without UV irradiation and without drug. The GSNO group was a solution containing GSNO and pyrogallol red without UV irradiation.

In vitro hydroxyl radical scavenging assay

Terephthalic acid fluorescence spectrophotometry was used to detect the scavenging ability of MS and MSNO on hydroxyl radicals. Specifically, the system containing different concentrations of MS/MSNO/NAC (0 μg/mL, 0.5 μg/mL, 1 μg/mL, 2 μg/mL, 4 μg/mL), 0.5 mM terephthalic acid, 0.5 mM ferrous sulfate, and 1 mM H2O2 was placed at room temperature for 10 min, and then the characteristic absorption peak of fluorescent 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid (·OH generated by ferrous sulfate and hydrogen peroxide through Fenton reaction can convert non-fluorescent terephthalic acid into fluorescent 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid) at 430 nm was detected.

In vitro hydrogen peroxide clearance assay

Hydrogen peroxide detection kit (Beyotime) was used to detect the hydrogen peroxide scavenging ability of MS/MSNO/NAC. Hydrogen peroxide solutions containing different concentrations of MS/MSNO were prepared, and the hydrogen peroxide concentration was detected using the kit after 30 min of reaction.

Establishment of CIRI model and behavioral testing

SD rats were purchased from Slake Jingda Experimental Animal Co., Ltd. All animal treatment procedures were performed in accordance with the treatment protocols approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University (Ethics approval number: XMSB-2023-0188). Rats were housed in a pathogen-free environment that met national standards, with a temperature of 26 °C, a relative humidity of 55%, a 12-h day-night cycle, and free access to food and water.

Rat CIRI model: The MCAO was used to simulate the ischemic period. After 2 h of ischemia, the sutures blocking the cerebral blood vessels were removed to simulate the reperfusion period (24 h). Specifically, SD rats were fasted for 12 h before surgery. Rats were weighed and anesthetized and fixed on a mouse board. The neck hair was shaved and the surface skin was disinfected with 75% ethanol. The surface skin was cut longitudinally to the left of the midline of the neck, and the common carotid artery, internal carotid artery and external carotid artery were exposed by blunt separation. Subsequently, the proximal end of the common carotid artery and the external carotid artery were ligated with 5-0 sutures, and the internal carotid artery was clamped with an artery clamp. A “V-shaped” incision was made between the proximal end of the common carotid artery and the artery clamp with ophthalmic scissors, the artery clamp was released, and the ligation line was gently inserted along the internal carotid artery until resistance was found and stopped. The suture was tied, and the ischemic stage began. After 2 h of ischemia, drugs were injected into the sublingual vein, the sutures blocking the blood vessels were removed, the wounds were sutured and disinfected with iodine, and the reperfusion period (24 h) began.

ZeaLonga Neurological Score: 0 points: no neurological deficit symptoms; 1 point: unable to fully extend the contralateral forelimb; 2 points: Turning in circles toward the paralyzed side while walking; 3 points: Leaning toward the paralyzed side when walking; 4 points: unable to walk independently and impaired consciousness; 5 points: death.

Transmission electron microscopy of brain tissue

After 2 h of cerebral ischemia and 24 h of reperfusion, fresh brain tissues from the Sham group, I/R group, and MSNO group were immediately placed in a transmission electron microscopy fixative and fixed overnight at 4 °C. Then, the brain tissues were washed three times in a PBS solution for 15 min each time. After fixation with osmium tetroxide (OsO4) at room temperature for 2 h, they were washed three times in a PBS solution. After gradient dehydration, the tissues were infiltrated and embedded in resin. The samples were cut into 60-80 nm thick sections with a microtome and double-stained with 3% uranyl acetate-lead citrate. The capillaries, neuronal mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum structures of brain tissues in different groups were observed using a Jeol 1200 EX transmission electron microscope.

Synthesis of FITC-MSNO

10 mg MSNO and 10 mg methoxypolyethylene glycol thiol (mPEG-SH) were placed in 8 mL deionized water and stirred for 12 h, and 2 mL FITC (dissolved in DMSO, 1 mg/mL) was added and reacted for 5 h in the dark. The product was repeatedly washed with ultrapure water for 3 times (4000 g/15 min) and dialyzed for 24 h (MWCO = 3500) to obtain FITC-labeled MSNO.

Biodistribution of MSNO

In vivo fluorescence tracking of drug distribution: The brain, heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney of the rats in the Sham group and the MSNO group were collected 1 h after reperfusion (MSNO injection), washed with PBS, and then placed under a stereo fluorescence microscope (Leica, M205FCA) for observation and image acquisition.

ICP-MS detection of drug content in tissues: Rats in the Sham group and the MSNO group were injected with MSNO, and the brain, heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were collected 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h after MSNO injection. The Mo content in each organ was determined by ICP-MS.

Detection of NO in brain tissue

Fresh brain tissues were collected from rats in the Sham, I/R, GSNO, MS, and MSNO groups at 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, and 6 h after drug injection, respectively. The brain tissues were washed three times with PBS to remove the blood on the surface, and then the brain tissues were cut into 5 slices vertically on the coronal plane. The brain tissue slices were immersed in DAF-FM DA dye solution and incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 15 min. The residual dye was washed with PBS, and then the images were collected using the small animal in vivo optical imaging system.

Monitoring of systemic blood pressure