Abstract

Background/Objective

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited health conditions affecting 7.74 million people worldwide. Regular automated red blood cell exchange (aRBCX) transfusions have been shown to improve control and management of SCD compared with manual RBCX (mRBCX). The aim of this study was to estimate the lifetime clinical and economic impact of aRBCX versus mRBCX in two United Kingdom-based populations with SCD (paediatrics initiated aged 5 years and adults initiated aged 38 years) that were clinically indicated for chronic disease-modifying transfusions (DMTs).

Methods

An individual patient-level simulation model was developed to estimate lifetime quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and healthcare costs. DMT administration programmes aligned with recommended treatment schedules. Monte Carlo methods determined baseline characteristics and clinical event occurrence. Pragmatic review findings and expert opinion informed model parameters and assumptions. Second-order probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed for 1000 individuals’ lifetimes over 500 iterations.

Results

Per individual, aRBCX reduced acute clinical events by 19% in both populations versus mRBCX. The time spent receiving chelation therapy reduced by 63 and 32 months for paediatric-initiated and adult-initiated individuals, respectively. Total lifetime DMT costs were reduced by £71,217 and £30,740 for paediatric-initiated and adult-initiated individuals, respectively. Overall, aRBCX increased QALYs and reduced costs by 0.29 and £112,811 in paediatric-initiated individuals and 0.24 and £61,895 in adult-initiated individuals. aRBCX was cost-effective in 100% of PSA iterations for both populations.

Conclusion

aRBCX shows potential to improve health outcomes and reduce healthcare costs for individuals with SCD initiating a chronic DMT programme.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s41669-025-00605-y.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Increasing access to automated red blood cell exchange (aRBCX) in all clinically eligible sickle cell disease populations in the United Kingdom has substantial potential to improve health outcomes and save costs. |

| For both clinically eligible populations, the key drivers of cost savings for aRBCX compared with manual red blood cell exchange (mRBCX) were fewer months on chelation therapy, a reduced number of disease-modifying transfusions, and a decrease in acute events. |

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited health conditions that affect the red blood cells, with an estimated global prevalence of 7.74 million in 2021 [1]. Since 2012, the estimated prevalence of SCD has increased by 41.4%, which is likely because of increasing birth rates and improvement in therapeutic interventions [1, 2]. The pathophysiology of SCD is complex, affecting every organ and body system, with wide-ranging impacts on general medical comorbidities [3]. Afflicted individuals, who are predominantly descended from people residing in areas with a high malaria prevalence, are prone to painful vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs), caused by sickle-shaped erythrocytes disrupting blood flow in small vessels [4, 5]. Severe VOCs can require hospitalisations or may cause an assortment of acute and chronic clinical events, including strokes and acute chest syndrome.

Individuals with SCD who are at high risk of a clinical event, or are ineligible for, refractory to, or unwilling to take pharmacological treatments can manage their disease with a chronic disease-modifying transfusion (DMT) programme [6–8].

Chronic DMTs can be administered as a top-up transfusion (TUT) or as manual or automated red blood cell exchange (mRBCX and aRBCX, respectively) [9]. Clinical indication is a key factor in determining the appropriate transfusion procedure. TUTs allow for improved transport of oxygen; therefore, a chronic TUT programme is clinically indicated to prevent severe anaemia. However, TUTs are associated with abnormal iron accumulation, which results in hemochromatosis (iron overload) [9–11]. The treatment of iron overload requires relatively expensive chelation therapy, which can lead to hepatic complications [12].

A chronic exchange transfusion programme is clinically indicated to provide a sustained reduction in acute and chronic events of SCD [9, 11]. Exchange transfusions reduce the apparent percentage of erythrocytes containing haemoglobin S (HbS), which have the ability to sickle, by replacing them with transfused erythrocytes containing haemoglobin A. aRBCX can accomplish a larger volume exchange and more efficiently lower HbS versus mRBCX [13].

mRBCX is a simple procedure and does not require specialist equipment. However, the risk of iron overload remains and it is time consuming for medical staff [10, 14, 15]. Typically, an mRBCX procedure takes between 2 and 4 h, but can last 8 h for previously non-transfused individuals [16]. Conversely, an aRBCX procedure is typically 2 h because it uses an apheresis machine that automatically conducts the exchange procedure according to a user-defined software protocol. However, operating an apheresis machine requires more specialist training than an mRBCX procedure [16]. The algorithm in an apheresis machine is used to calculate the HbS targets for the procedure and controls the pumps and valves to remove red blood cells and, thereby, eliminates the risk of iron overload [17]. aRBCX is described as the only reliably iron-neutral transfusion therapy currently available [9].

Multiple studies have shown aRBCX is more effective than mRBCX in reducing HbS when a DMT programme is initiated [18–20]. Individuals can initiate a DMT programme aged 5 if they weigh over 20 kg; however, some individuals reach adulthood before a DMT programme is indicated. aRBCX allows for increased time between DMTs and improved disease control versus mRBCX [10, 17, 21]. In adults, improved control with aRBCX resulted in a 25% reduction in hospitalisations for pain management and a 79% reduction in hospitalisations over 5 years versus mRBCX [17, 21].

In the United Kingdom (UK), the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) appraised whether routine commissioning of aRBCX within the National Health Service (NHS) would allow for optimal healthcare resource allocation in 2015 [9] and was reappraised in 2020. Evidence was synthesised from multiple sources to estimate healthcare costs of different chronic DMT programmes over a short time horizon.

NICE concluded that use of aRBCX for people with SCD who are clinically indicated for a chronic transfusion programme had the potential to save the English NHS £12.9 million each year [9]. Consequently, aRBCX has been introduced into 22 NHS trusts throughout the UK [22].

NICE noted that there may be further cost-saving implications with aRBCX. This cost-effectiveness analysis built upon the research conducted by NICE to gain further insight into the potential lifetime clinical impact and cost savings of aRBCX versus mRBCX to prophylactically manage SCD from the perspective of the England and Wales NHS and Personal Social Services.

Methods

Model Overview

A patient-level simulation (PLS) fixed-time increment, Monte Carlo micro-simulation model was conceptualised and developed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA). The PLS model structure allowed for the complex relationships and interactions between clinical events to be captured appropriately. This is crucial for heterogenous diseases like SCD, in which every individual has a unique experience.

This model was used to estimate the lifetime clinical impact and cost savings associated with paediatric- and adult-initiated aRBCX versus mRBCX to manage SCD. The population of interest were those with SCD who are at high risk of clinical events and ineligible for, refractory to, or unwilling to take disease-modifying pharmacological treatments and, therefore, are clinically indicated for, and require, a lifelong, chronic DMT programme.

The PLS model structure used is illustrated in Fig. 1. Each individual’s simulation started with their initiation onto a DMT programme of either aRBCX or mRBCX. Once the programme was determined, each month of the individual’s life was modelled until death.

Fig. 1.

Model structure. The model schematic presents the simulation of an individual through their time horizon. Circles represent the beginning of an individual's simulation or the averaging of outcomes following simulation cessation, rectangles with smoothed edges indicate the receipt of treatments or the calculation of an individual's overall simulation outcomes, and rectangles without smoothed edges provide additional background information. Arrows between shapes indicate the sequencing of the simulation, and labels defined as 'yes' or 'no' indicate the possible route of an individual's simulation following a diamond. Schematic developed using draw.io (http://www.diagrams.net). ACS acute chest syndrome, aRBCX automated red blood cell exchange, CKD chronic kidney disease, DMT disease-modifying transfusion, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, HRQoL health-related quality of life, MI myocardial infarction, mRBCX manual red blood cell exchange, PH pulmonary hypertension, SCD sickle cell disease, SMR standardised mortality ratio, VOC vaso-occlusive crisis

In each monthly cycle, the appropriate DMT schedule determined whether an individual received a DMT. Administration of mRBCX could cause iron overload and, therefore, chelation therapy. The occurrence of acute and chronic clinical events, directly related to the pathophysiology of SCD, were also considered.

At the end of each monthly cycle, an individual either died or entered the next cycle. The simulation repeated until death occurred. Once an individual’s simulation was complete, the total lifetime healthcare costs and health outcomes were calculated. The simulation was repeated for 1000 individuals’ lifetimes to allow outcomes to converge.

Health outcomes were presented in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and life years (LYs). Cost outcomes were expressed as 2022/2023 Great British Pounds (GBP, £). Where necessary, costs were adjusted to reflect 2022/2023 values using the annual percentage increase in pay and prices for the NHS [23].

To align with the NICE reference case, outcomes were discounted at 3.5% annually, a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained was applied, and a lifetime time horizon was adopted to reflect all important differences in costs and health outcomes [24]. The decision problem is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Decision problem and UK pharmacoeconomic guidelines

| Element | Decision |

|---|---|

| Populations |

SCD in all populations clinically eligible for, and requiring, chronic DMTs at high risk of clinical events and ineligible for, refractory to, or unwilling to take disease-modifying pharmacological treatments, for example, hydroxycarbamide. Adult population Paediatric population aged at least 5 years old and weighing at least 20 kg |

| Subgroups |

100% adult-initiated individuals with iron overload at baseline 0% adult-initiated individuals with iron overload at baseline 100% paediatric-initiated individuals with iron overload at baseline 0% paediatric-initiated individuals with iron overload at baseline |

| Intervention | aRBCX |

| Comparator | mRBCX |

| Outcomes |

Incremental costs and QALYs ICER NMB NHB |

| Perspective | England and Wales National Health Service and Personal Social Services. |

| Setting | England and Wales |

| Cycle length | 1 month |

| Time horizon | Lifetime |

| Discount rates | 3.5% for both costs and QALYs |

| Cost-effectiveness threshold | £20,000 per QALY gained |

aRBCX automated red blood cell exchange, DMT disease-modifying exchange transfusion, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, mRBCX manual red blood cell exchange, NHB net health benefit, NMB net monetary benefit, QALY quality-adjusted life year, SCD sickle cell disease

Model Parameters

Two medical science liaisons (MSLs) employed by Terumo, with 12 and 18 years of experience in the field of transfusion medicine and haematology, respectively, were consulted throughout the protocol development across several teleconferences. They provided valuable clinical insight and guidance to shape the model's assumptions and recommended key data sources. Meeting minutes summarising the conversations were reviewed and signed off by all meeting attendees.

Where possible, parameter estimates and uncertainty measures were obtained from robust literature sources, national databases, and national SCD treatment guidelines. RL provided estimates for costs and resource use based on data collected within a haematology centre. Data and recommended assumptions (where data were sparse) were compiled in a health economic protocol.

The completed protocol, including all assumptions and inputs (supplemental Tables S1–S21, see the electronic supplementary material), was reviewed for clinical plausibility by the MSLs and a director of global medical affairs at Terumo (12 years of industry experience). Written feedback was provided and addressed within the final protocol. Following this internal review, the assumptions and inputs were validated by an independent panel of three external experts (AdK, ET, MB). Each expert was independently sent the materials and asked to provide written feedback. In response to this feedback, the modelling team provided additional context, where requested, and made minor refinements to the model assumptions. There was no discordance in the final recommendations received from the expert panel.

Baseline Population Characteristics

Monte Carlo methods were used to generate two distinct populations of 1000 individuals that were assumed to initiate a chronic DMT programme at model entry until death. In the adult-initiated population, individuals entered the model with a mean age of 38 years, and each had a specific age, weight, sex, and history of stroke and chronic events simulated at baseline (supplemental Table S2, see the electronic supplementary material).

The paediatric-initiated population were at high risk of stroke and, therefore, clinically eligible for DMTs. Typically, this population would be identified by their transcranial Doppler (TCD) screening, a regular diagnostic test starting at age 2 years [25]. However, there were no data to inform the efficacy of aRBCX in paediatric individuals aged younger than 5 years. Therefore, it was assumed paediatric individuals initiated DMTs at age 5 years and they weighed at least 20 kg (supplemental Table S3). Because of a paucity of robust data, it was assumed that paediatric individuals initiating DMTs had no history of either stroke or chronic events.

Paediatric individuals clinically eligible for DMT programmes are, by definition, high risk [10]. Even with treatment, not all individuals will survive to 38 years, the mean age at which the adult cohort initiated DMTs [26]. Therefore, these populations are clinically different. Model outcomes should not be used to compare outcomes between the population who initiated a DMT programme in adulthood and those who initiated a DMT programme in childhood.

Disease-Modifying Exchange Transfusion Resource Use and Costs

A micro-costing approach was used to estimate the costs per DMT procedure for both populations. aRBCX procedure costs accounted for both capital costs and procedure-specific costs. For each transfusion method, procedure-specific costs were calculated by multiplying resource use per population and procedure by corresponding unit costs. A point estimate was used in the model. DMT-related inputs and the cost per procedure for adults and paediatric individuals are presented in supplemental Tables S4–S8 (see the electronic supplementary material). For paediatric individuals, there was a paucity of data on the frequency of DMT and the units of erythrocytes required. It is anticipated that dosing will change over time; however, this is a key area of uncertainty.

Iron Overload

A percentage of adults and paediatric individuals had iron overload at baseline, representing poor management of their SCD prior to initiation onto the chronic DMT programme (supplemental Table S9, see the electronic supplementary material).

aRBCX procedures are considered iron neutral. After aRBCX initiation, the probability of iron overload is 0% [17]. Conversely, mRBCX procedures are not considered iron neutral. Therefore, individuals receiving mRBCX DMTs were subject to a probability of developing iron overload after each transfusion [10, 14, 15].

If iron overload was present, a simulated individual received chelation therapy monitoring and chelation therapy treatment costs, defined as the weighted average of deferasirox and desferrioxamine costs, with posology based on an individual’s weight and treatment length drawn from a statistical distribution. Once an individual’s chelation therapy treatment length expired, they no longer received chelation therapy. However, individuals receiving mRBCX DMTs returned to being at risk of developing iron overload and requiring further iron chelation treatment (supplemental Table S9).

Clinical Events

In clinical practice, there are many clinical events that occur because of SCD; therefore, it was not feasible to model all clinical events. Arguably the most notable acute event attributed to SCD is VOC. In clinical practice, occurrence of a severe VOC can cause tissue damage and additional clinical events. Real-world evidence showed that people on a chronic aRBCX programme experienced 25% fewer VOCs than those on a chronic mRBCX programme (supplemental Table S10, see the electronic supplementary material) [17].

A highly pragmatic search of literature and review of previous cost-effectiveness models was conducted to identify which clinical events were sensitive to VOC reoccurrence and were frequently experienced amongst individuals with SCD. Ten clinical events (seven acute and four chronic), detailed in supplemental Tables S11 and S12, were selected for the model.

It was assumed clinical event rates (apart from VOCs) were equivalent for both DMTs at baseline. In the month following a VOC, the per-cycle rate of other clinical events was assumed to increase according to published, peer reviewed hazard ratios [27].

Furthermore, the development of an individual’s clinical event history over their lifetime enabled a difference in clinical event outcomes to be modelled [4]. This was a conservative approach, necessary because there is a lack of robust data to inform differences and, if data were available, there is a risk of overestimating the impact of aRBCX given the dependent nature of SCD clinical events.

The corresponding event rates and clinical event interactions are presented in supplemental Tables S11 to S13.

The first stage of treatment for clinical events associated with SCD is an emergency TUT or exchange transfusion [28]. An emergency transfusion incurred a cost in the model, which was calculated as a weighted average of aRBCX, mRBCX, and TUT procedure costs. Specific weightings for each event were informed by national guidelines (supplemental Tables S14 and S15) [28].

Acute events, except for strokes, incurred a one-off hospitalisation cost in the cycle the event occurred (supplemental Table S16). Occurrence of strokes or chronic events incurred an upfront cost, followed by a permanent monthly cost, which was applied until death (supplemental Table S17).

Health-Related Quality of Life

Health outcomes were captured using EQ-5D-3L utilities, which measure both the quality and length of each LY. A score of 0 is equivalent to death and 1 is equivalent to a year of perfect health.

Evidence suggests that uncomplicated SCD does impact utility; however, it was not possible to identify from the literature whether the baseline SCD utility value would encompass clinical events [29]. Therefore, to avoid double counting the impact of clinical events on an individual’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL), it was necessary to assume that an individual’s baseline utility was equivalent to age- and sex-adjusted EQ-5D-3L general population utilities. Utility decrements were applied following the occurrence of clinical events.

Acute events were associated with a 1-month utility decrement, applied in the same cycle as event occurrence (supplemental Table S18, see the electronic supplementary material). Chronic events and strokes were associated with a permanent utility decrement that was applied in each cycle following event occurrence until death (supplemental Table S19).

It was anticipated that individuals would experience several clinical events over their lifetime. Therefore, a multiplicative approach was applied to avoid implausibly low values and align with NICE guidelines [24].

Mortality

At the end of each cycle, the probability of death was calculated by applying a standardised mortality ratio (SMR) associated with clinical events the individual experienced to the appropriate, pre-coronavirus disease 2019 (pre-COVID-19), general population mortality rate, accounting for the age and sex of the individual [30, 31].

Acute events were associated with an SMR being applied to the baseline rate of death in the same cycle as event occurrence. It was assumed that death occurred if an individual experienced four strokes (supplemental Table S20, see the electronic supplementary material). Chronic events were associated with an SMR being applied to the baseline rate of death in the same cycle as event occurrence and all subsequent cycles until an individual died (supplemental Table S21).

Outcomes and Sensitivity Analysis

In the reference case, model outcomes were generated over 500 lifetime simulations of a heterogenous population of 1000 individuals to allow for convergence of results. This approach, known as a second-order probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), addressed uncertainty in the model parameters. In the second-order analysis, parameters considered to be uncertain were varied as per the appropriate statistical distribution (supplemental Table S22, see the electronic supplementary material). Second-order probabilistic analysis outcomes are reported as means (95% credible interval). A key outcome was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The ICER was compared with a pre-defined cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained, which accounts for healthcare spending that would be displaced if aRBCX was adopted.

First-order scenario analyses were also conducted. The scenarios investigated key uncertain parameters and assumptions that influence the cost-saving potential of aRBCX. Scenarios included including time horizon, time between DMTs, units of erythrocytes, clinical event interactions, and the assumption of iron neutrality. Supplemental Table S27 details each scenario.

Results

Results converged at approximately 100 iterations (supplemental Figure S1, see the electronic supplementary material). Overall, aRBCX was cost saving for both adult-initiated and paediatric-initiated individuals. Over a lifetime, paediatric-initiated or adult-initiated aRBCX was estimated to save the NHS a mean (95% credible interval [CrI]) of £112,811 (£110,833–£114,789) or £61,895 (£60,399–£63,392) per person, respectively, with aRBCX cost saving in 100% of the second-order iterations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key second-order probabilistic lifetime outcomes per individual

| Outcome | Mean (95% CrI) outcome for aRBCX | Mean (95% CrI) outcome for mRBCX | Mean (95% CrI) incremental outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult-initiated individuals | |||

| Total costs (discounted) | £495,738 (£493,028 to £498,449) | £557,634 (£555,136 to £560,132) | − £61,895 (− £63,392 to − £60,399) |

| Total QALYs (discounted) | 9.38 (9.34 to 9.42) | 9.15 (9.11 to 9.19) | 0.24 (0.22 to 0.25) |

| ICER | – | – | aRBCX dominates mRBCX |

| Percentage of cost-saving PSA iterations | – | – | 100.0% |

| Percentage of QALY-increasing PSA iterations | – | – | 91% |

| Percentage of cost-effective PSA iterations | – | – | 100.0% |

| Total number of DMTs | 149.28 (148.70 to 149.86) | 293.20 (292.02 to 294.39) | − 143.92 (− 144.58 to − 143.27) |

| Total number of acute clinical events | 58.08 (56.92 to 59.24) | 71.41 (70.43 to 72.40) | − 13.33 (− 14.18 to − 12.49) |

| Total months spent on chelation therapy | 4.76 (4.74 to 4.77) | 36.50 (36.00 to 37.00) | − 31.75 (− 32.24 to − 31.25) |

| Total LYs (undiscounted) | 24.84 (24.74 to 24.93) | 24.43 (24.33 to 24.53) | 0.40 (0.37 to 0.43) |

| Paediatric-initiated individuals | |||

| Total costs (discounted) | £534,091 (£531,017 to £537,165) | £646,902 (£644,283 to £649,521) | − £112,811 (− £114,789 to − £110,833) |

| Total QALYs (discounted) | 16.04 (16.00 to 16.08) | 15.75 (15.71 to 15.80) | 0.29 (0.27 to 0.31) |

| ICER | – | – | aRBCX dominates mRBCX |

| Percentage of cost-saving PSA iterations | – | – | 100.0% |

| Percentage of QALY-increasing PSA iterations | – | – | 91.2% |

| Percentage of cost-effective PSA iterations | – | – | 100.0% |

| Total number of DMTs | 283.26 (282.22 to 284.3) | 557.01 (554.78 to 559.24) | − 273.75 (− 275.02 to − 272.48) |

| Total number of acute clinical events | 105.27 (103.39 to 107.16) | 129.20 (127.82 to 130.58) | − 23.93 (− 25.45 to − 22.40) |

| Total months spent on chelation therapy | 4.79 (4.78 to 4.81) | 67.92 (66.98 to 68.86) | − 63.13 (− 64.07 to − 62.19) |

| Total LYs (undiscounted) | 47.17 (46.99 to 47.34) | 46.42 (46.23 to 46.60) | 0.75 (0.70 to 0.80) |

aRBCX automated red blood cell exchange, CrI credible interval, DMT disease-modifying exchange transfusion, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, LY life year, mRBCX manual red blood cell exchange, PSA probabilistic sensitivity analysis, QALY quality-adjusted life year

Key drivers of cost savings for both populations were the reduction of months spent on chelation therapy, the reduction in the number of DMTs, and a reduction in acute events.

Individuals who received aRBCX from childhood (because of iron overload at baseline) spent 4.79 (4.78–4.81) months on chelation therapy, whereas individuals receiving mRBCX from childhood spend 67.92 (66.98–68.86) months on chelation therapy. The model subsequently predicted a lifetime saving of £12,147 (£11,973–£12,321) per person. Similarly, adults initiating aRBCX spent 4.76 (4.74–4.77) months on chelation therapy, versus 36.50 (36.00–37.00) months for adults initiating mRBCX, saving £9785 (£9633–£9938) per adult.

Per DMT procedure, aRBCX costed £1136 and £1788 for children and adults, respectively, and mRBCX costed £952 and £1073 for children and adults, respectively (supplemental Table S8). In the paediatric population, individuals were subject to age-dependent DMT procedure costs in each model cycle.

Over a lifetime, individuals initiating aRBCX in childhood received 274 (272–275) fewer DMTs versus mRBCX, resulting in an estimated cost saving of £71,217 (£71,036–£71,398). Because of a reduction in 23.93 (22.40–25.45) acute clinical events with aRBCX compared to mRBCX, the model also predicted fewer emergency transfusions, saving £6244 (£5847–£6641). Furthermore, acute event costs were reduced by £26,359 (£24,685–£28,033) with aRBCX versus mRBCX.

Similarly, over a lifetime, adults initiating aRBCX received 144 (143–145) fewer DMTs versus mRBCX, resulting in an estimated cost saving of £30,740 (£30,572–£30,907). Furthermore, a reduction of 13.33 (12.49–14.18) acute clinical events for those on aRBCX versus mRBCX resulted in fewer emergency transfusions, saving £5192 (£4862–£5522). There was also an estimated £20,195 (£18,911–£21,478) reduction in the cost of acute events with aRBCX.

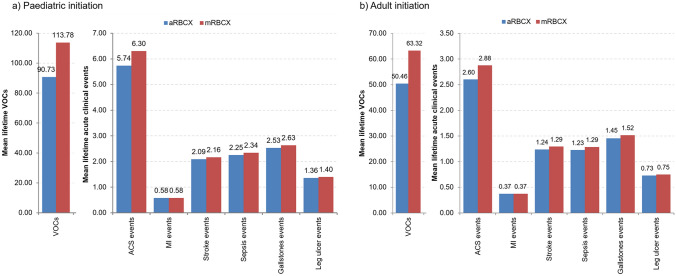

Figure 2 presents the estimated reduction in the incidence of clinical events. For both populations, a detailed, estimated breakdown of all model events and their associated costs is presented in supplemental Tables S23–S26.

Fig. 2.

Lifetime clinical events for paediatric initiation (left) and adult initiation (right) of chronic DMTs. ACS acute chest syndrome, aRBCX automated red blood cell exchange, DMT disease-modifying transfusion, MI myocardial infarction, mRBCX manual red blood cell exchange, VOC vaso-occlusive crisis

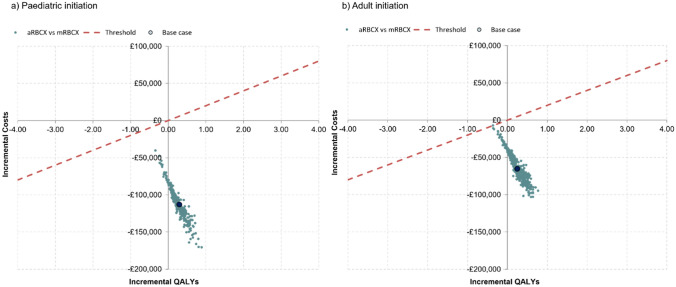

The cost-saving potential is shown in Fig. 3, in which the average cost and QALYs for each of the 500 second-order iterations are plotted. All points lie underneath the x-axis, showing that aRBCX was either cost saving or cost-effective in all iterations. This was consistent across most thresholds of cost-effectiveness (supplemental Figure S2). The first-order cost and QALY estimates sit centrally within the PSA iterations, adding validity to the model estimates.

Fig. 3.

Cost-effectiveness plane for the paediatric initiation (left) and adult initiation (right) of chronic DMTs. The x-axis indicates incremental health outcomes, and the y-axis indicates incremental costs for aRBCX compared with mRBCX. A dashed red line indicates the cost-effectiveness threshold. aRBCX automated red blood cell exchange, DMT disease-modifying transfusion, mRBCX manual red blood cell exchange, QALY quality-adjusted life year

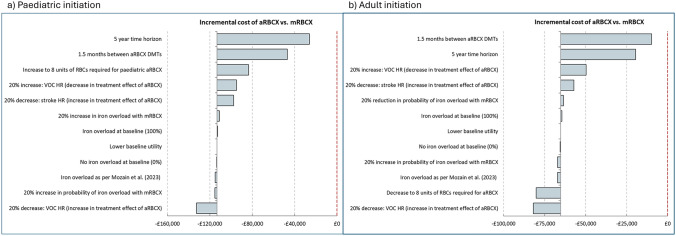

Scenario Analysis

First-order scenario analysis was run for 1000 paediatric-initiated and adult-initiated individuals. aRBCX remained cost saving in all scenarios when versus mRBCX for both populations. Key scenarios determining the cost-saving potential of aRBCX included the total time horizon and those that influenced the total cost of aRBCX administration and the treatment effect of aRBCX versus mRBCX. As per the analysis conducted by NICE, aRBCX was cost saving versus mRBCX at 5 years. A table of results is presented in supplemental Table S27, and a diagram showing the impact on the cost for each scenario is presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Key inner loop scenario analysis lifetime incremental cost outcomes per individual for paediatric initiation (left) and adult initiation (right) of chronic DMTs. aRBCX automated red blood cell exchange, DMT disease-modifying transfusion, HR hazard ratio, mRBCX manual red blood cell exchange, QALY quality-adjusted life year, RBC red blood cell, VOC vaso-occlusive crisis

Discussion

The history of SCD has been marked with controversies over prophylactic treatment, treatments for pain crises, and funding [32]. Despite recent advancements, people continue to struggle to have symptoms recognised and addressed.

Since 2021, three therapeutic interventions and one gene therapy have undergone technical appraisal by NICE [33–36]. Although voxelotor was initially recommended for routine commissioning within the NHS, it was withdrawn from markets worldwide by its manufacturer in 2024 [37]. As such, exchange transfusions remain the gold standard treatment to prophylactically manage SCD in adults and paediatric individuals who are at high risk of clinical events and ineligible for, refractory to, or unwilling to take hydroxycarbamide [14, 15].

aRBCX was appraised by NICE in 2016 for use in the aforementioned populations, in which it was estimated that aRBCX would save £18,000 per person per year [9]. Our analysis built upon NICE’s research to include health outcomes and extended the time horizon to a lifetime given the chronic nature of the disease. We built a PLS model to conduct a second-order probabilistic analysis that allowed us to control for observed heterogeneity in the populations, interaction between clinical events, and uncertainty in the literature. Our model estimates aligned with NICE’s conclusion: aRBCX has the potential to be substantially cost saving in both populations. Furthermore, aRBCX was cost-effective versus mRBCX at thresholds commonly used in UK decision making for 100% of the second-order probabilistic iterations. The second-order probabilistic analysis accounted for uncertainty in parameters.

In both populations, the key driver of the observed cost savings was the reduction in DMT costs. Despite aRBCX costing £184 and £715 more per paediatric and adult procedure, respectively, the increased length of time between procedures generated an overall lifetime reduction in costs of £30,740 (£30,572–£30,907) and £71,217 (£71,036–£71,398) for adults and paediatric individuals, respectively. Furthermore, in clinical practice, it was observed that, following 1 year of regular aRBCX, the time between procedures increased and units of blood decreased [14]. However, the reported effect of time was not considered in the model.

Another substantial driver of cost savings, and the key driver in improvement in QALYs, was the reduction in acute events requiring hospitalisations. Of the acute events, reduction in severe VOCs requiring hospitalisation amounted to most of the lifetime clinical event costs for adult-initiated and paediatric-initiated individuals. As per the units of blood, hospitalisations were found to progressively decrease with repeated aRBCX versus mRBCX [17]. This level of granularity was not captured in the model, and therefore, there is the potential for additional aRBCX-related clinical and cost benefits that are not captured in the model.

An increase in the months spent receiving chelation therapy for mRBCX versus aRBCX was the third largest source of cost savings for aRBCX. The impact of chelation therapy may increase with time, given that a review of literature for aRBCX, by NICE from 2020, observed that the cost of chelation had increased, while the cost of red blood cells remained stable [38].

Limitations

The model development process involved a scoping period in which paucity of robust SCD literature and large, head-to-head studies comparing aRBCX with mRBCX was observed. This is a historic problem with SCD, arising because of the ‘sad and shameful’ historic neglect of SCD, as recognised by President Nixon 61 years after the identification of the disease by Western cultures in 1910 [4, 32]. Yet, funding and research for SCD lagged behind similar genetic diseases [39]. Therefore, several assumptions were required to inform model parameterisation and structure. Assumptions were validated by clinical experts. Uncertainty in parameters was explored in the second-order probabilistic analysis and the first-order scenario analysis. Results of the first- and second-order analyses were consistent. Both estimated that aRBCX was cost-saving and cost-effective versus mRBCX.

The reduction VOC rate for aRBCX versus mRBCX was fundamental to the model outcomes, favouring aRBCX; however, there was a lack of robust data to inform this parameter. This parameter was informed by a small, London-based single-centre study of 43 participants [17]. Although the sample size was relatively small, individuals were followed for over 10 years and over 3000 transfusions were recorded. This study observed that aRBCX administered over several years was associated with continuous decreases in inpatient days, hospital admissions, and emergency department visits [17].

There was a substantial dearth of published evidence estimating the impact of a chronic DMT programme on QALYs and LYs in the modelled populations. Consequently, the model estimated only a marginal increase in QALYs and LYs for people on aRBCX versus mRBCX. Evidence suggests that individuals experiencing fewer VOCs accrue more LYs and HRQoL compared with those with recurrent VOCs [40, 41]. The model may not have fully captured the indirect effect of aRBCX on HRQoL and LYs. These outcomes were mediated through the change in VOC rate, and it was conservatively assumed that the VOC rate was fixed over time. However, studies show aRBCX was associated with a continuous decrease in VOC rate over time [17].

Treatment standards in developed countries like England and Wales are high, and the average life expectancy for people with SCD is estimated to be between 58 and 67 years, which adds validation to model estimates of 62.4 and 62.0 years for adults receiving aRBCX and mRBCX, respectively (estimated by adding LYs to the average age at model entry) [42]. It is important to highlight that the increased LYs caused a minor uplift in the costs of chronic clinical events because people were living with chronic conditions longer.

For the purpose of this analysis, the probability of iron overload in aRBCX was considered negligible (0%). This was supported by expert opinion, anecdotal evidence from specialist centres, and published, UK-based, peer-reviewed literature [17]. Clinicians advised that aRBCX settings can be adjusted to reduce post-transfusion fatigue events leading to iron overload [17]. To account for this, it was investigated in a scenario analysis, in which the probability of iron overload for aRBCX and mRBCX was informed using published, comparative literature from Saudi-Arabia [14, 15]. The conclusion did not change.

Model outcomes may have underestimated clinical event reduction for aRBCX versus mRBCX. Firstly, improvement in the treatment effect of aRBCX with chronic use was not considered. Secondly, the model included a select subgroup of clinical events for which data was readily available. Many clinical events (including cardiomegaly, avascular necrosis, osteomyelitis, and priapism) were omitted. Finally, potential clinical practicalities of administering aRBCX in individuals weighing between 20 kg and 25 kg (personal priming processes) were not considered in the model. However, the aforementioned omissions are anticipated to have negligible impact on model outcomes.

In clinical practice, paediatric individuals aged less than 5 years can experience a stroke, a chronic clinical event, or a transfusion [43]. However, because of a paucity of data, it was necessary to assume that all paediatric individuals entered the model at 5 years of age, and weighing of 20 kg or over (in line with the population clinically indicated for aRBCX) and without a history of strokes or chronic events. For certain clinical events, it was assumed that early paediatric and adolescent clinical event rates were equivalent (supplemental Tables S10 and S11, see the electronic supplementary material), which may have caused clinical events to be overestimated.

There is a lack of economic evidence against which the results of this analysis can be validated. Published evidence (supplemental Table S28) generally considered different populations on a variety of treatments, and different healthcare settings, time horizons, and cost categories, which limited the possibility of externally validating model outcomes.

This research did not evaluate societal and environmental impacts of improved disease control, and therefore the potential benefits of aRBCX on the patient experience are likely underestimated. Indeed, the societal impacts of SCD have been previously noted to impose a substantial burden on individuals living with SCD [27, 44, 45].

This is particularly evident when considering clinical events. The model estimated a reduction in acute event-related hospitalisations for paediatric-initiated and adult-initiated individuals. It is reasonable to assume that this will improve productivity and reduce absenteeism from school and/or work. Furthermore, individuals on a chronic aRBCX programme may be able to manage pain crises at home with more ease and experience fewer pain crises with repeated use of aRBCX over time [17]. Therefore, the QALY gain for aRBCX versus mRBCX may be underestimated, particularly when considering the wider potential societal impact, which was not considered in the analysis, including improved productivity, reduced absenteeism, and reduced caregiver burden.

The consequence of developing iron overload was only considered in terms of its impact to direct healthcare costs. Treatment-related adverse events associated with iron overload that may impact HRQoL and survival were excluded from the model because of a paucity of robust data. Therefore, the analysis has likely underestimated benefits of aRBCX versus mRBCX.

Conclusion

For individuals initiating a lifetime DMT programme as a child or an adult (namely, those at high risk of clinical events and ineligible for, refractory to, or unwilling to take disease-modifying pharmacological treatments and, therefore, clinically eligible for a chronic DMT programme), current evidence predicts that aRBCX will allow for increased success in achieving clinical targets versus mRBCX, leading to improved control of SCD, fewer DMTs, fewer clinical events, and less time on chelation therapy versus mRBCX. There is potential for large cost savings in the UK NHS, allowing funds, hospital beds, and staff time to be redistributed.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Rob Lewis, General Manager for Haematology and Pathology at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, who was instrumental in informing resource use and costs.

Funding

This research was funded by Terumo BCT Europe.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

AY and MC are employees of Terumo BCT Europe. AdK reports speaker fees and honoraria for Pfizer. MB reports advisory boards for Agios, Forma, Octapharma, and GBT Novartis; honoraria for lecturing for Terumo, Sanofi, and Pfizer; support to attend meetings for Novartis, Pfizer, and GBT; and support for patient activities for Agios, Terumo, and Novartis. SMM, JB, SJM, IE, and ET declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Code availability

The model developed for this research is not publicly available.

Author contributions

MC and AY conceptualised the research problem. SMM, JB, and SJM conceptualised the model and design. All authors contributed to and approved the final model design. SMM and JB collected data, built the model, and ran and interpreted the cost-effectiveness analysis with assistance from SJM and IE. SMM and JB wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript content and review.

References

- 1.GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000–2021: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(8):e585–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oteng-Ntim E, et al. Prophylactic exchange transfusion in sickle cell disease pregnancy: a TAPS2 feasibility randomized controlled trial. Blood Adv. 2024;8(16):4359–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez RM, et al. Complications of sickle cell disease and current management approaches, in addressing sickle cell disease: a strategic plan and blueprint for action. National Academies Press (US); 2020. [PubMed]

- 4.Williams TN, Thein SL. Sickle cell anemia and its phenotypes. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2018;19(1):113–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware RE, et al. Sickle cell disease. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):311–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Styles LA, Vichinsky E. Effects of a long-term transfusion regimen on sickle cell-related illnesses. J Pediatr. 1994;125(6):909–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pegelow CH, et al. Risk of recurrent stroke in patients with sickle cell disease treated with erythrocyte transfusions. J Pediatr. 1995;126(6):896–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell MO, et al. Effect of transfusion therapy on arteriographic abnormalities and on recurrence of stroke in sickle cell disease. Blood. 1984;63(1):162–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Spectra Optia for automatic red blood cell exchange in people with sickle cell disease. Medical technologies guidance [MTG28]. 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg28.

- 10.Howard J. Sickle cell disease: when and how to transfuse. Hematology 2014, the American Society of Hematology Education Program Book. 2016;2016(1):625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Davis BA, et al. Guidelines on red cell transfusion in sickle cell disease. Part I: principles and laboratory aspects. Br J Haematol. 2017. 10.1111/bjh.14346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter J, Garbowski M. Consequences and management of iron overload in sickle cell disease. Hematology. 2013;2013(1):447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly S. Logistics, risks, and benefits of automated red blood cell exchange for patients with sickle cell disease. Hematology. 2023;2023(1):646–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dedeken L, et al. Automated RBC exchange compared to manual exchange transfusion for children with sickle cell disease is cost-effective and reduces iron overload. Transfusion. 2018;58(6):1356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Mozain N, et al. Comparative study between chronic automated red blood cell exchange and manual exchange transfusion in patients with sickle cell disease: a single center experience from Saudi Arabia. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2023;17(1):91–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sickle Cell Society. Standards for clinical care of adults with sickle cell disease in the UK. 2018.

- 17.Tsitsikas DA, et al. Automated red cell exchange in the management of sickle cell disease. J Clin Med. 2021;10(4):767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihalca D, et al. Emergency red cell exchange for the management of acute complications in sickle cell disease: automated versus manual. Transfus Med. 2023;33(4):287–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escobar C, et al. Partial red blood cell exchange in children and young patients with sickle cell disease: manual versus automated procedure. Acta Med Port. 2017;30:727–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ait Abdallah N, et al. Automated RBC exchange has a greater effect on whole blood viscosity than manual whole blood exchange in adult patients with sickle cell disease. Vox Sang. 2020;115(8):722–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsitsikas DA, et al. A 5-year cost analysis of automated red cell exchange transfusion for the management of recurrent painful crises in adult patients with sickle cell disease. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017. 10.1016/j.transci.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS England. Sickle cell patients in North East to benefit from national £1.5m technology investment. 2024. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/north-east-yorkshire/2024/02/14/sickle-cell-patients-in-north-east-to-benefit-from-national-1-5m-technology-investment/.

- 23.Jones KWH, Birch S, Castelli A, Chalkley M, Dargan A, Forder JE, Gao M, Hinde S, Markham S, Premji S, Findlay D, Teo H. Unit costs of Health and Social Care 2023 manual, P.S.S.R.U.U.o.K.C.f.H.E.U.o. York), editor. 2024.

- 24.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE health technology evaluations: the manual. 2023. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36/chapter/introduction-to-health-technology-evaluation.

- 25.Sickle Cell Society. A parent's guide to managing sickle cell disease, 4th edn. Sickle Cell Society and Brent Sickle Cell & Thalassaemia Centre (London); 2021.

- 26.Quinn CT, et al. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;115(17):3447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Sick cell disease. An assessment of two gene therapies: exagamglogene autotemcel and lovotibeglogene autotemcel. 2023. Available from: https://icer.org/assessment/sickle-cell-disease-2023/.

- 28.Davis BA, et al. Guidelines on red cell transfusion in sickle cell disease part II: indications for transfusion. Br J Haematol. 2017;176(2):192–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anie KA, et al. Patient self-assessment of hospital pain, mood and health-related quality of life in adults with sickle cell disease. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e001274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wailoo A. A guide to calculating burden of illness for NICE evaluations: Technical Support Document 23. 2024. Available from: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/nice-dsu.

- 31.Office for National Statistics. National Life Tables UK 2017 to 2019. 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/datasets/nationallifetablesunitedkingdomreferencetables.

- 32.Wailoo K. Sickle cell disease—a history of progress and peril. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):805–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Voxelotor for treating haemolytic anaemia caused by sickle cell disease. Technology appraisal guidance [TA981]. 2024. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta981/chapter/2-Information-about-voxelotor.

- 34.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. l-glutamine for preventing painful crises in sickle cell disease in people aged 5 years and over [ID1523]. Discontinued [GID-TA10452]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/discontinued/gid-ta10452.

- 35.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Crizanlizumab for preventing sickle cell crises in sickle cell disease. Technology appraisal guidance [TA743]. 2021. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta743.

- 36.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Exagamglogene autotemcel for treating sickle cell disease [ID4016]. In development [GID-TA11249]. 2024. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta11249. [PubMed]

- 37.Pfizer. Pfizer voluntarily withdraws all lots of sickle cell disease treatment OXBRYTA® (voxelotor) From Worldwide Markets. 2024. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-voluntarily-withdraws-all-lots-sickle-cell-disease.

- 38.Willits I, Cole H. Review report of MTG28 Spectra Optia for automatic red blood cell exchange in patients with sickle cell disease. 2020. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg28/evidence/review-report-august-2020-pdf-8831615294.

- 39.Farooq F, et al. Comparison of US federal and foundation funding of research for sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis and factors associated with research productivity. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e201737–e201737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arlet JB, et al. Impact of hospitalized vaso-occlusive crises in the previous calendar year on mortality and complications in adults with sickle cell disease: a French population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;40:100901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drahos J, et al. Health-related quality of life and economic impacts in adults with sickle cell disease with recurrent vaso-occlusive crises: findings from a prospective longitudinal real-world survey. Qual Life Res. 2025;34(7):2019–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sickle cell disease: what is the prognosis? 2021. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/sickle-cell-disease/background-information/prognosis/.

- 43.Strouse JJ, et al. The excess burden of stroke in hospitalized adults with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2009. 10.1002/ajh.21476. (1096-8652 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Sickle cell disease. An assessment of crizanlizumab, voxelotor, and l-glutamine for the treatment of sickle cell disease. 2020. Available from: https://icer.org/assessment/sickle-cell-disease-2020/.

- 45.Khan HA-O, et al. Sickle cell disease and social determinants of health: a scoping review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023. 10.1002/pbc.30089. (1545–5017 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.