Abstract

Background

Primary immune deficiency (PID) comprises over 400 inborn errors of immunity. Immune globulin replacement therapy (IGRT) is the standard of care for many PID subtypes. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is the historic standard of care, but subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) offers several advantages for IGRT. Further, a novel pre-filled syringe (PFS) drug packaging form of SCIG is expected to facilitate more efficient patient infusions.

Objective

The aim of this study was to quantify the projected budget impact associated with adding the IgPro20 PFS as an SCIG drug packaging option to a health plan formulary for the treatment of PID.

Methods

A budget impact model (BIM) was developed across the United States (US) integrated delivery networks (IDNs)’ perspective over a 3-year time horizon to quantify the projected budget impact of adding the IgPro20 PFS as an SCIG packaging option for the treatment of PID. Model comparators included six IVIGs and seven SCIGs. A one-way sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of model parameters on the budget impact. Scenario analyses of alternative market share shifts and pricing were conducted to test the robustness of the model results.

Results

From the perspective of an IDN with 25 million members, the average annual expected cost per PID patient was US$73,343 for IgPro20 vials w/pump, US$60,892 for IgPro20 PFS w/pump, US$72,179 for IVIG, and US$96,581 for other SCIGs. Assuming market share uptake of 6.0% in the first year for IgPro20 PFS w/pump, rising to 8.4% by year 3, and offset by corresponding proportionate reductions in shares of the non-PFS SCIG IgPro20 vials w/pump only, the expected incremental budget impact over the 3-year horizon was savings of US$10.5 million.

Conclusion

This BIM demonstrates that uptake of subcutaneous IgPro20 PFS is expected to be associated with substantial savings for a US IDN, including drug cost savings if offset by reduced non-PFS SCIG-packaging use.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s41669-025-00594-y.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| This analysis reveals substantial expected economic benefits—a budget impact savings of US$10.5 million over 3 years from a US integrated delivery network (IDN) perspective, with the addition of subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) pre-filled syringe (PFS) as a treatment option for patients with primary immune deficiency (PID). |

| Drug cost savings with SCIG PFS in comparison with vial-based SCIGs is driven largely by published evidence of 17% reduced dose requirements (likely due to avoidance of product waste in drawing from vials to conventional syringes) in PFS administration compared with vials for patients with PID. |

| Healthcare decision makers should consider switching suitable patients with PID from non-PFS-based SCIG to PFS-packaged SCIG products. |

Introduction

Primary immune deficiency (PID) comprises a group of between 350 and 400 genetic immunity disorders [1, 2]. Prevalence of PID varies by region and has been estimated to be in the range of 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 individuals [3]. However, the true prevalence of PID with confirmatory diagnosis is likely closer to 1 in 1200 individuals, or 0.08%, according to a telephonic survey-based analysis of United States households [4]. The primary determining characteristic of PIDs is the inability to mount a sufficient immune response to infection [5]. Therefore, PID treatment and management include prevention of recurrent infection and treatment of active infections. Immune globulin replacement therapy (IGRT) is a mainstay of therapy for a variety of PID subtypes [6]. In addition to infection prevention-related benefits, IGRT is necessary to mitigate the clinical burden associated with chronic immunodeficiency-related complications [7]. IGRT can be administered via the use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG).

While evidence suggests that the two routes of administration exhibit similar efficacy as measured by infection severity and length of infection [8, 9], it is notable that safety may be improved with SCIG administration [10]. It has also been shown in clinical studies that switching from hospital-based IVIG to home-based SCIG significantly improves health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in adult PID patients [11–15]. Furthermore, SCIG has been associated with greater tolerability and easier administration than IVIG [16]. Median time for SCIG infusions, including preparation and cleanup, has been reported to be about 2.5 h [17]. By contrast, a nurse must be present for the entirety of IVIG administration [18], and IVIG infusions may take up to 6 h [19, 20].

Although IVIG infusions in a home setting are less costly than those in office or outpatient hospital settings [21], self-infusion with SCIGs offers additional potential economic benefits over IVIG infusions even when IVIG is infused in the home [21]. Certainly, multiple factors may affect the relative cost of SCIG versus IVIG therapy, such as the specific product and its price, formulation, method of administration (i.e., with or without a pump), site of administration (for IVIGs), frequency of administration, and what dose is ultimately used (per infusion and annually) [6, 18, 22]. Yet, according to economic analyses performed in Sweden [23], Germany [24], the United Kingdom [25], Canada [18], and France [26], home-based SCIG was consistently found to be 25–75% less costly to the healthcare system overall, but especially when compared with hospital-based IVIG [18].

Despite these potential financial benefits, SCIG adoption is limited by several (modifiable and nonmodifiable) factors. Nonmodifiable factors may include the physical inability to conduct self-infusion or a phobia of needles or self-injection [17]. Modifiable patient factors may include level of comfort with conducting self-infusions, and ensuring better patient training and education may enhance self-infusion comfort. Evidence suggests that better trainers, adequate training time, and ensuring patient confidence after training facilitated greater treatment satisfaction on SCIGs and global HRQoL [17].

A pre-filled syringe (PFS) drug packaging form of SCIG may improve immunoglobulin delivery and promote more optimized utilization of self-infused SCIGs [27]. A PFS SCIG requires fewer steps and less tubing and ancillary supplies than a vial-based infusion; it is also potentially easier to train patients on self-infusion and thus enhance the overall patient experience, which follows similar innovations in other conditions [27, 28]. Additionally, PFS administration potentially avoids product waste, which may be accentuated with SCIG self-infusions by patients lacking professional training [29–31]. A budget impact model (BIM) was developed to estimate the expected benefits of adding PFS SCIG as a treatment for PID from a US integrated delivery network (IDN) perspective, representing health plans where healthcare providers and payer work together to provide collaborative and coordinate care. A secondary perspective of the analysis was the traditional private commercial plan perspective. The objective of the study was to quantify the budget impact associated with adding immune globulin subcutaneous (human), 20% liquid (IgPro20; Hizentra) PFS as an SCIG drug packaging option to a health plan formulary for the treatment of PID.

Methods

Model Structure

A Microsoft Excel-based BIM was developed in accordance with AMCP [32] and ISPOR best practices [33] over a 3-year time horizon to estimate the budget impact of adding IgPro20 PFS to a health plan formulary for the treatment of PID. As a BIM presents financial streams over time, it was not necessary to discount the costs [33].

Model Inputs

A hypothetical US health plan with 25 million patients was assumed. Prevalence of PID was assumed to be 1 case per 1200 individuals based on an epidemiologic analysis of diagnosed PID in US patients [4], resulting in a projected 20,825 patients with PID. Applying a rate of 88% of patients treated with immunoglobulin at any time [19] resulted in 18,326 treated patients.

The model included six IVIGs and seven SCIGs; full trade and generic names are found in Supplementary Table 1 (see electronic supplementary material [ESM]).

Model interventions were market shares of pump-administered IgPro20 (SCIG) and stratified by IgPro20 PFS and vial as alternative SCIG drug packaging methods. Market shares for each of the immunoglobulin products were based on internal 2023 immunoglobulin market share reports. Table 1 presents assumed IVIG market shares and non-IgPro20 SCIG shares (re-calculated by subtracting overall current IgPro20 share of 52% and re-expressing the rest as a proportion of non-IgPro20 SCIG use). Pharmacy costs included average sales price (ASP), wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), and average wholesale price (AWP) (using ASP pricing files [34] and IBM Micromedex [35]). Payment mix for immunoglobulin products was assumed to be 73% for ASP, 25% for AWP payments, and 2% for WAC pricing [36]; we also simulated implications of ASP-only pricing. Dosing for both SCIG and IVIG is weight-based, and a patient weight of 66.5 kg was assumed based on US averages accounting for age and gender in patients with PID [4, 37].

Table 1.

Model comparator market shares and pricing

| Market share, % | ASPa, US$ | WACb, US$ | AWPb, US$ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hizentra | 12.80b | 214.55 | 240.24 | |

| IVIGs | ||||

| Gamunex-C | 26.3 | 50.64 | 130.12 | 156.14 |

| Gammagard Liquid | 37.8 | 46.03 | 155.24 | 186.29 |

| Privigen | 21.6 | 47.99 | 159.40 | 191.28 |

| Octagam | 8.3 | 44.12 | 179.60 | 215.52 |

| Panzyga | 5.8 | 65.74 | 190.16 | 228.19 |

| Flebogamma | 0.2 | 56.12 | 104.98 | 125.98 |

| IVIG weighted average | 100.0 | 48.67 | 153.48 | 184.17 |

| Non-Hizentra SCIGsc | ||||

| HyQvia | 25.7 | 83.28 | 222.08 | 266.50 |

| Gammagard Liquid | 10.1 | 46.03 | 155.24 | 186.29 |

| Gamunex-C | 8.6 | 50.64 | 130.12 | 156.14 |

| Cuvitru | 43.2 | 81.38 | 201.68 | 242.02 |

| Xembify | 8.0 | 70.00 | 173.60 | 208.32 |

| Cutaquig | 4.4 | 71.93 | 197.28 | 236.74 |

| SCIG weighted average | 100.0 | 71.23 | 183.80 | 220.56 |

ASP average sales price, AWP average wholesale price, CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, SCIG subcutaneous immunoglobulin, WAC wholesale acquisition cost

aASP reported by CMS is ASP + 6%

bHizentra ASP prices are reported per 100-mg units. All other products’ ASP prices are reported per 500-mg units. All WAC and AWP prices (obtained from IBM Micromedex) are reported per gram (1000 mg)

cNon-Hizentra SCIG market shares calculated by subtracting current Hizentra market share of 52% among all SCIGs and expressing the other SCIGs as a percentage of non-Hizentra SCIG use

Model input assumptions are listed in Table 2. A first set of model inputs describes distribution of IVIG site of care across one of four sites: hospital outpatient, office/other setting, patient home self-administration, or patient home assisted by a visiting nurse. The following percentages were assumed for setting of IVIG administration: hospital outpatient, 9%; office/other setting, 53%; patient home self-administration, 3%; and patient home administration by visiting nurse, 35% [19, 20].

Table 2.

Key model inputs

| Inputs | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Setting for IVIG infusions | ||

| IVIG home (self-administered), % | 3 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| IVIG home (nurse-administered), % | 35 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| IVIG hospital outpatient, % | 9 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| IVIG office/other, % | 53 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| Setting for SCIG infusions | ||

| Hizentra home (self-administered), % | 100 | Assumption |

| Other SCIGs home (self-administered), % | 96 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| HyQvia home (self-administered), % | 64 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| Other SCIGs home (nurse-administered), % | 2 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| HyQvia home (nurse-administered), % | 0 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| Other SCIGs office/other, % | 2 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| HyQvia office/other, % | 36 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| Training for SCIG infusions | ||

| Hizentra vials w/pump (self-administered) patient/caregiver training hours | 2 | Mallick 2020 [17]; Mallick 2024 [38] |

| Hizentra PFSs w/pump (self-administered) patient/caregiver training hours | 2 | Mallick 2024 [38] |

| Other SCIG patient/caregiver training hours | 2 | Mallick 2020 [17] |

| HyQvia patient/caregiver training hours | 4 | IDF 2017 [20] |

| Cost per training hour, US$ | 29.48 | CPT 98960 [57] |

| IVIG (nondrug) infusion costs, US$ | ||

| Home (nurse-administered) cost per infusion (commercial) | 389 | Slen 2014 [39]; Luthra 2014 [21] |

| IVIG administration, hospital outpatient (commercial) | 2884 | Slen 2014 [39]; Luthra 2014 [21] |

| IVIG administration, office (commercial) | 1036 | Slen 2014 [39] |

| Weight-based dosing: IVIGs and SCIGs | ||

| Mean weight of US children and adults, kg | 66.5 | Fryar 2021 [37] |

| IVIG maintenance dose per infusion in PID, g/kg | 0.450 | Haddad 2012 [42]; Gamunex-C US PI [43] |

| IVIG to Hizentra dosing ratio, adjusted for differences in frequency of infusions | 1.05a | Krishnarajah 2016 [44] |

| SCIG dosing (g/week), vial packaging method, median (IQR) | 12 (9–16)b | Mallick 2024 [38] |

| SCIG dosing (g/week), PFS packaging method, median (IQR) | 10 (8–12)b | Mallick 2024 [38] |

| Number of IVIG infusions per year | 15 | Younger 2013 [49] |

| Number of SCIG infusions per year, mean | 40.6 | IDF 2017 [20] |

| Time spent per IVIG infusion | ||

| IVIG administration, infusion time (home nurse-administered), h | 4.30 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| IVIG administration, nurse-administered, caretaker time, h | 4.30 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| IVIG administration, infusion time, hospital outpatient, h | 4.30 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| IVIG administration, caretaker time, hospital outpatient, h | 4.30 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| IVIG administration, office, infusion time, h | 4.30 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| IVIG administration, office caretaker time, h | 4.30 | IDF 2018 [19] |

| Hourly wage for infusion/caretaker time, US$ | 42.80 | US Bureau of Labor Statistics [58] |

CPT Current Procedural Terminology, h hours, IQR interquartile range, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, PFS pre-filled syringe, PID primary immune deficiency, SCIG subcutaneous immunoglobulin

aRatio of 1.05 was applied to IVIG dosing of 0.45 g/kg bodyweight and adjusted by the ratio of SCIG to IVIG infusions (40.6/15) to arrive at per-infusion Hizentra dose of 0.175 g/kg bodyweight (or 12.7 g) for an average 66.5-kg bodyweight of US children and adults (US DHS) for model input

bPFS-to-vial observed dosing ratio for patients of average weight of 72 kg (10/12 = 0.833) was used to adjust PFS dose from 0.175 to 0.145; from APIQ (Association des Patients Immunodeficients du Quebec) adult patient survey

A second set of model inputs provides two options for SCIG administration (patient home self-administration, 96%; nurse-assisted infusion at home, 2%) or within the office/other setting (2%) for SCIGs, apart from HyQvia. Patient home self-administration (64%) and office/other setting (36%) were the sites of care for HyQvia [19]. A third set of model inputs relates to SCIG self-infusion training. The magnitude of training and associated aggregate costs based on nurse time for self-administration of SCIG was expected to vary by SCIG drug packaging method. Recent evidence from a survey suggested, however, that training time was similar for vials and PFS training at a median of 2 h, presumably due to PFS training having occurred virtually during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic [38].

A fourth set of model inputs relates to medical (nondrug) costs per IVIG infusion. Infusion costs (exclusive of pharmacy costs) were derived from two studies comparing costs per infusion across home and hospital outpatient settings from a commercial perspective: nurse-administered home setting, US$389; office setting, US$1036; hospital outpatient setting, US$2884 [21, 39]. These studies were the only identified publications that spelled out US IG administration costs. However, a comparable estimate for nurse-administered home-setting IVIG administration is also available from the CMS Medicare IVIG home administration demonstration program, where the reimbursement amounts are very comparable to the base case of US$389 used in our model [40]. All costs in the analysis were inflated to 2023 US dollars using the consumer price index (CPI) [41].

A fifth set of model inputs provides details on immunoglobulin weight-based dosing. The dosing for IgPro20 was derived from a user-defined maintenance dose of IVIG, which was equal to 0.450 g/kg per infusion [42, 43]. The IVIG maintenance dose was then converted to a total SCIG dose per infusion using an IVIG-to-SCIG conversion ratio equal to 1.05 based on US real-word observations [44], ultimately yielding an IgPro20 base-case dose of 0.175 g/kg body weight. Additional support for this dosing conversion ratio comes from Jolles et al. [6]. Dosing for IgPro20 packaged as a PFS was assumed to be 16.7% lower than for IgPro20 vials based on evidence from a recent patient survey [38], resulting in an input IgPro20 PFS dose of 0.145 g/kg. Base-case doses of other SCIG comparators were calculated with a similar dose conversion methodology with a conversion ratio of 1.30 for Cuvitru, 1.00 for HyQvia, 1.37 for Xembify, and 1.40 for Cutaquig based on respective US labels [45–48]. All doses per kg of patient bodyweight were converted to dose per infusion based on US vital statistics data on average patient weight [4, 37]. Finally, total dose per IVIG and SCIG infusion, per corresponding patient, was converted to annual dose per patient based on evidence on the number of IVIG and SCIG infusions, respectively [19, 49].

Table 3 describes costing of training and infusion times. The cost of SCIG training is only applicable to the IDN perspective, as training costs are typically not paid for directly at the commercial health plan level. Similarly, SCIG infusion supply costs were incorporated based on prices for the infusion pump (amortized over the assumed life of the pump), tubing, syringes, tip-to-tip connectors, needles, and bandages, as suitable based on SCIG drug packaging method. Thus, for example, infusion supply costs for SCIGs packaged as vials were expected to be higher than for SCIGs packaged as PFSs because the former require transfer needles and tubing to transfer product from the vial to the syringe.

Table 3.

Input costs of SCIG self-infusion by SCIG drug packaging method and SCIG model of administration—drug costs, training costs, infusion supply costs, and infusion time costs

| SCIG drug packaging and administration method | SCIG self-infusion training, h | Total (annual) SCIG self-infusion training costa, US$ | SCIG costs of infusion supplies per infusion, US$ | Infusion time, h | Indirect costs of infusion timeb, US$ | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hizentra (and other SCIGs) vials w/pump | 2 | 58.96 | 75c | 1.69 | 20.25 | Assumption; BLS 2022 [58] |

| Hizentra PFSd w/pump | 2 | 58.96 | 31.25 | 1.49 | 17.86 | Assumption; BLS 2022 [58] |

h hours, IgPro20 immune globulin subcutaneous (human), 20%, IgrHu10 immune globulin infusion 10% (human) with recombinant human hyaluronidase, PFS pre-filled syringe, PID primary immune deficiency, SCIG subcutaneous immunoglobulin, US United States

aObtained by multiplying training hours by the assumed hourly wages of the training nurse (US$29.48) [57]; training costs were assumed to be annual on the conservative assumption that patients would be re-trained annually

bObtained by multiplying infusion time hours by the assumed hourly wage of all employees (US$42.80) [54] times the percentage of patients requiring a caregiver for infusions (28%)

cHyQvia infusion costs were separately calculated to be US$117.92 based on the fact that 10% of HyQvia infusions were nurse-administered

dHizentra is the only SCIG currently available in PFS drug packaging

For the IDN perspective, the indirect costs of infusion and caretaker time were included on the presumption that IDNs generally incorporate integrated patient care, including case management at some level [50]; for the commercial perspective, these were excluded. Based on literature estimates, 28% of adult patients were in need of a caretaker [51]. These indirect costs included IVIG and SCIG infusion time consisting of travel time, pre-infusion time, infusion time, and post-infusion time for the patient and caretaker. Based on estimates from a recent survey of patients with PID [19], the following infusion times were assumed: for the home (nurse-administered) IVIG administration setting, the default total infusion time was taken to be 5.85 h with 0.93 h for pre-infusion time, 4.30 h for infusion time, and 0.62 h for post-infusion time. In the home setting, caretaker hours are not included, as it is assumed that nurses independently complete the infusion. For non-home IVIG administrations (hospital and infusion center), the default total infusion time for each of the patient and the caretaker was 60 m (1 h) for travel time, 0.93 h for pre-infusion time, 4.30 h for actual infusion time, and 0.62 h for post-infusion time [19]. Total infusion time for IgPro20 vials was 1.69 h and total infusion time for IgPro20 PFS was 1.49 h [38]. As IgPro20 infusion times in all sites of care were substantially less than 8 h in these patients with immunodeficiencies, based on published evidence, we did not account for overnight patient accommodations. Additionally, ambulatory food costs would be expected to be minimal and were not included in the absence of evidence.

Costs of IVIG infusion-related complications and IVIG safety events were included for both commercial and IDN perspectives. IVIG-related infusion complications included those specifically associated with patients requiring infusion ports (assumed 3.3%, based on a recent study [52]) and those more generally associated with IVIGs. Infusion port-related safety events included catheter-related infections (0.93%), catheter-related blood stream infections (1.50%), thrombophlebitis (2.20%), and infiltration and extravasation (0.60%). More general IVIG-related safety events included thromboembolic events (0.38%), aseptic meningitis (0.07%), and acute hemolysis (0.04%).

A one-way sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying the key model parameters one at a time while holding all other inputs constant to determine the sensitivity and robustness of the model. Various scenario analyses were conducted in the model, including alternative market share shift scenarios with an increased market share of IgPro20 PFS by 5% scenario and a 5% IgPro20 PFS market share increase with a reduction only in other SCIG market shares, alternative dose conversion methodology using an IgPro20 dosing switch ratio of 1.37 instead of the real-world evidence based value of 1.05, and alternative drug pricing basis.

Results

Expected Current Costs Per Patient

First, we report expected costs under current market shares (as presented in Table 1). From the IDN perspective, the average annual expected cost per PID patient was US$73,343 for IgPro20 vials w/pump and US$60,892 for IgPro20 PFS w/pump. For IVIGs, overall expected annual cost was US$72,179. For other (non-IgPro20 SCIGs), average expected annual cost was US$96,581 (Fig. 1). Drug costs were the predominant cost per patient followed by non-drug cost which included administration by site of care (varies by site of care) and infusion complication and AE costs for IVIG (US$172.04 per patient).

Fig. 1.

Average and incremental cost per patient in the treatment of PID (IDN perspective). All costs are in 2023 US dollars. IDN integrated delivery network, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, PFS pre-filled syringe, PID primary immune deficiency, SCIG subcutaneous immunoglobulin

From a commercial health plan perspective, as training and infusion costs for SCIGs, as well as patient/caretaker indirect costs for IVIGs, are not borne directly by commercial health plans, expected costs for IgPro20 and other SCIGs and IVIGs were all lower than was the case for an IDN perspective. The cost for IgPro20 vials was US$69,417 and US$57,824 for IgPro20 PFS, US$67,002 for IVIGs, and US$91,936 for non-IgPro20 SCIGs.

Expected Current Budget Spending

Second, we report expected current budget spending for an IDN (or commercial health plan) with a membership of 25 million and an expected immunoglobulin-treated PID population of about 18,300 patients. Our model projects that such an IDN spends approximately US$1.40 billion annually on immunoglobulin treatment; on a per-member per-month basis, this amounts to US$4.72 per month (Fig. 2). In a commercial payer, this is about US$1.33 billion annually (i.e., not accounting for patient and caregiver time and travel costs).

Fig. 2.

Net budget impact in the treatment of PID (IDN perspective). All costs are in 2023 US dollars. IDN integrated delivery network, PID primary immune deficiency

Expected Budget Impact (Change in Budget): Base Case, One-Way Sensitivity, and Alternative Scenarios

Third, we report expected budget impact under a base-case scenario for an IDN. In this scenario, we assume that IgPro20 PFS w/pump, recently launched in the US market, will gradually increase its market share to 6.0%, 7.2%, and 8.4% in years 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Table 4). The increased market share with IgPro20 PFS is assumed to be offset by corresponding proportionate reductions in the share of IgPro20 vials w/pump (on the premise that availability of a PFS packaging option facilitates ongoing organic shifts from IgPro20 vials to IgPro20 PFSs; that is, an intra-IgPro20 shift). In other words, we assume market share of other immunoglobulins remains unchanged.

Table 4.

Base case assumptions on market share shifts over 3 years

| Current, % | Year 1, % | Year 2, % | Year 3, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hizentra vials w/pump | 20.0 | 17.9 | 16.7 | 15.5 |

| Hizentra PFS w/pump | 3.8 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 8.4 |

| IVIG | 54.3 | 54.3 | 54.3 | 54.3 |

| Other SCIG | 21.8 | 21.8 | 21.8 | 21.8 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, PFS pre-filled syringe, SCIG subcutaneous immunoglobulin

Based on the above assumptions on intra-IgPro20 organic market-share shifts, the BIM predicted incremental cost savings of US$10.5 million over 3 years for an IDN. This translated to a per-patient incremental decrease of US$12,451 (from the previous US$73,343 to US$60,892). For a commercial plan under the base-case market shift scenarios, the BIM predicted incremental costs savings of US$9.76 million over 3 years. The decrease in expected budget was driven largely by a lower drug cost for IgPro20 PFSs consequent to the 16.7% lower dose for IgPro20 PFSs compared with IgPro20 vials and other SCIG vials, as observed in a recent patient survey [38]. Additionally, lower self-infusion time costs with PFSs compared with vials accounted for further expected cost reductions.

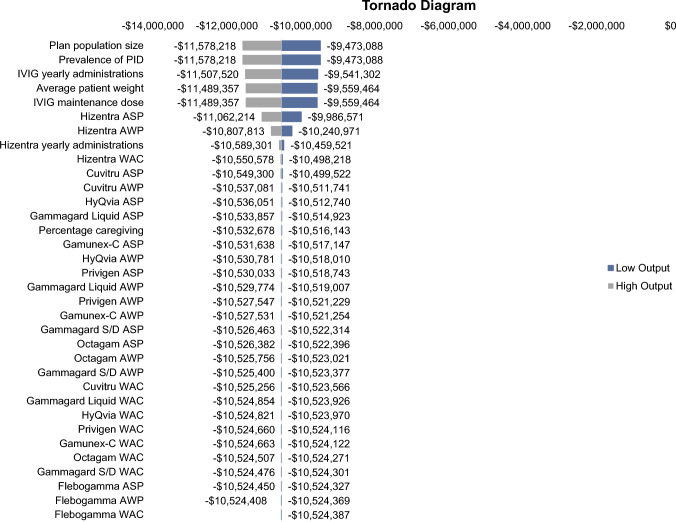

A one-way sensitivity analysis was conducted with the key model inputs all varied by plus or minus 10% to assess which inputs had the largest impact on the model results (budget impact). The inputs with the largest impact on the model results were plan population size, prevalence of PID, the number of IVIG yearly administrations, the average patient weight, and the IVIG maintenance dose (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

One-way sensitivity analysis tornado diagram (IDN perspective). All costs are in 2023 US dollars. ASP average sales price, AWP average wholesale price, IDN integrated delivery network, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, PID primary immune deficiency, WAC wholesale acquisition cost

A primary scenario analysis investigated the base case at ASP-only pricing, as opposed to a weighted basket of ASP, AWP, and WAC pricing. This resulted in expected 3-year cost savings of US$9.3 million for an IDN, which is about US$1.2 million lower than under the blended drug pricing basis; this is because the IgPro20 ASP, in absolute terms, is lower than corresponding WACs and AWPs, resulting in smaller expected absolute savings with a switch to IgPro20 PFS from IgPro20 vials. Other alternative scenarios were evaluated in sensitivity analyses and are described in detail in Supplementary Section 1 of the ESM.

Discussion

While significant progress has been made toward preventing life-threatening infections and complications of PID with IGRT, unmet needs persist in how IGRT is administered and packaged. Several studies have demonstrated the clinical [10, 12–15] and economic benefit [10, 16, 18, 23–26] of immunoglobulin administration with SCIGs. This budget impact analysis focused on recent expansion of SCIG drug packaging options, specifically to the PFS option. Arguably, additional value for patients and payers may yet be gained via identifying not only the optimal immunoglobulin administration method but also the optimal SCIG packaging option for patients with PID [6, 10].

Patient satisfaction with a successful transition from IVIG to SCIG is dependent in part on effective training [17], flexible and greater frequency of shorter infusions [17], and volume of drug infused [16]. Two recent real-world analyses described the relationship between IVIG and SCIG dosing in actual US practice. In one study, it was found that near-equivalent maintenance dosing at 4–8 months was suitable when switching patients with PID from IVIG to SCIG [45] (dosing ratio = 1.05:1 for IVIG to SCIG). In another study, it was similarly found in a population of patients receiving immunoglobulin at home that the average SCIG dose was 10 g weekly (40 g monthly), while the average IVIG dose was 36 g monthly [53]. Utilizing real-world dosing as model input, and given that the purpose of this model is to reflect real-world paradigms (including those related to real-world dosing), we accordingly assumed the ratio of IVIG to SCIG was 1.05. However, in sensitivity analyses, we also modeled the budget impact of the labeled 1.37 dosing ratio found within the IgPro20 prescribing information and label [54].

We leveraged literature-based inputs to develop a BIM on the introduction of an IgPro20 PFS as a SCIG packaging option to a health plan formulary to inform corresponding financial implications across IDNs and commercial perspectives. PFS is a drug packaging option known to be associated with several potential advantages over conventional vial-based packaging, including reduced overall infusion preparation time and shorter actual infusion time, more accurate dosing, greater sterility assurance, reduced risk of contamination, and reduced drug wastage [27, 29–31]. Reduced drug wastage is attributable to users typically overdrawing injectable product from vials to allow for potential leakage involved in depressing the plunger to expel air bubbles; in fact, manufacturers typically need to overfill vials to account for this possibility [27, 31].

A recent patient survey in patients with PID confirmed shorter infusion times, especially infusion preparation time, with PFSs. Importantly, PFSs are associated with about 17% less use of immunoglobulin product per infusion than vial-based infusions [38]. The actual median dosage (12 g/infusion for vials) reported by patients (children, adolescents, and adults) for an average 66.5-kg body weight in this patient survey was remarkably similar to what would be projected (12.7 g/infusion) with an IVIG to SCIG dosing ratio of 1.05, which was found in the previously noted real-world evidence study [44] and conducted at a time when only vials were available. In part on account of incorporating this evidence as input into this BIM, the model finds that introduction of the PFS (IgPro20) as a SCIG packaging option is expected to be cost saving from both the IDN and commercial perspectives.

Our conclusion on the overall favorable budget impact of a shift from SCIG vials to SCIG PFSs was projected to be strongest if substitution of SCIG PFSs for SCIG vials is neutral with respect to IVIG shares, given that IVIGs are typically less costly for payers. However, projected cost savings were attenuated compared with this scenario if the substitution of PFSs for vials was also neutral in terms of shares of other non-IgPro20 SCIG shares, since their weighted average cost is higher than that of IgPro20 and thus was not an additional source of expected savings. By implication, a growth in PFSs that is driven disproportionately by a site of care shift from IVIGs to self-infusion with SCIGs was expected to yield smaller, yet positive, cost savings. Similarly, if PFSs enable greater transition to PFS-based manual push administration, on account of its relative ease of use compared with vials, then one may expect additional savings from additionally reduced training costs of PFS self-infusions. Further, one may also expect in this case a more substantial reduction in infusion supplies, beyond elimination of tubing, to encompass elimination of the need for a mechanical pump.

In an additional scenario analysis, we found that expected budget savings with any shift to SCIG PFS infusions involving a reduced share of IVIGs would be somewhat mitigated, yet positive, if the IgPro20 (the only PFS) dosing ratio was as high as 1.37 based on the US label. Finally, we explored the projected impact of drug pricing based on ASPs alone. Projected cost savings were lower as the difference between IgPro20 relative to a less costly market basket of IVIG in terms of ASPs is smaller, and, relative to a more costly market basket of SCIGs, is also smaller than a difference based on incorporating AWP or WAC pricing.

Our budget impact findings on the value of SCIG options overall are supported by those of a 2020 Australian study; this cost-minimization analysis found that IVIGs and SCIGs were associated with cost values of A$297,547 and A$251,713, respectively, a difference that is substantially higher than our expected cost difference of US$12,451, even accounting for currency rates [55]. A BIM from British Columbia, Canada, from 2013 reported expected savings of slightly over $5000 per patient [18]. While cross-national studies cannot be directly compared with each other—especially when considering regional healthcare decision maker and study time period-related differences—the directionality of cost benefit in each suggests that SCIGs are more financially appealing than IVIGs.

The cost savings seen in the IgPro20 PFS model complement humanistic outcomes associated with SCIG treatment. Results from a PRO survey of SCIG-taking patients reported that better infusion efficiency (made possible by adequate training on SCIG administration) leads to greater treatment satisfaction as measured by the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) [17]. Specifically, it was found that more efficient infusions as measured by infusion preparation time < 20 m and actual infusion time < 2 h was a good predictor of TSQM scores falling within the highest tertile of the population among 366 patients with SCIG. Therefore, infusion efficiency can drive greater value even in the context of chronic, well-managed conditions such as PID in the absence of other differentiating factors across IGRT products [17]. A transition to SCIG could be optimally supported by adequate self-infusion training for patients, including training on the manual push option for low-volume infusions [17]. Other necessary training may revolve around alleviating any modifiable patient-level factors that could decrease the chance of successful uptake to SCIG. Patients who are unable to self-infuse for reasons of lack of manual dexterity may not be good candidates for a switch to SCIG.

PFS drug packaging options have been shown to be valuable alternatives to traditional vial-based drug packaging in other therapeutic areas as well. In one study, a PFS formulation of methotrexate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis was met with strong appreciation by patients and attending healthcare professionals due to convenience-related benefits. The results were corroborated by a previous study suggesting that 93% of patients preferred the PFS drug packaging option over the non-PFS alternative [56].

As with any economic model, the validity of the results depends on the inputs and assumptions made within the model, including the size of the target population, pharmacy costs, medical costs, and market shares. While efforts have been made to employ methodologically sound modeling techniques, the inputs and assumptions used in this model may not be appropriate for all healthcare decision makers. Additionally, it was not the intent of this present investigation to measure the uptake of non-PFS IgPro20 formulations. As such, this model may not reflect real-world market dynamics wherein uptake of multiple SCIG formulations and agents may increase simultaneously. The model did not include adverse events for IgPro20 in the treatment of PID, as the IgPro20 adverse events were relatively minor in frequency and intensity. The most common adverse events in the IgPro20 trial in PID were headache, diarrhea, fatigue, back pain, nausea, pain in extremity, and cough [54]. Finally, we assumed that all patients who administered the IgPro20 PFS within the home setting would be subject to self-administration, as is primarily the case in the US. In some real-world settings outside the US, IgPro20 PFS administration may need to be facilitated via an infusion nurse, which may partly dilute the expected economic benefit.

Conclusions

This budget impact analysis demonstrates that uptake of an SC IgPro20 PFS in the management of PID is associated with potential cost savings to a US IDN. As such, there may be value in switching patients from non-PFS SCIG to SCIG PFS; in our analysis, the budget impact of a gradual switch of 5% market share to SCIG PFS was associated with a budget impact savings of US$10.5 million over 3 years for a US IDN.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Lisa Peachey and Kylie Matthews with Cencora (formerly Xcenda) for copyediting and manuscript preparation.

Declarations

Funding

This study was funded by CSL Behring.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr Carlton reports employment with Cencora, which received funding from CSL Behring for this analysis. Dr Mallick reports employment with CSL Behring at the time of the study.

Availability of Data and Material

We did not generate any datasets, because our work proceeded within a mathematical approach. One can obtain the relevant model inputs from the reference list.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Code Availability

The Excel model file is included in online supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Dr Mallick and Dr Carlton made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work and reviewing it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- 1.Tangye SG, Al-herz W, Bousfiha A, et al. Human inborn errors of immunity: 2019 update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies expert committee. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40(1):24–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picard C, Bobby Gaspar H, Al-Herz W, et al. International Union of Immunological Societies: 2017 primary immunodeficiency diseases committee report on inborn errors of immunity. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38(1):96–128. 10.1007/s10875-017-0464-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi AY, Iyer VN, Hagan JB, St Sauver JL, Boyce TG. Incidence and temporal trends of primary immunodeficiency: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle JM, Buckley RH. Population prevalence of diagnosed primary immunodeficiency disease in the United States. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27:497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Primary immunodeficiency (PI). https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/primary_immunodeficiency.htm. Accessed 12 Oct 2023.

- 6.Jolles S, Orange J, Gardulf A, Stein M, et al. Current treatment options with immunoglobulin G for the individualization of care in patients with primary immunodeficiency disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;179(2):146–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gernez Y, Baker MG, Maglione PJ. Humoral immunodeficiencies: conferred risk of infections and benefits of immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Transfusion. 2018;58(Suppl 3):3056–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapel HM, Spickett GP, Ericson D, Engl W, Eibl MM, Bjorkander J. The comparison of the efficacy and safety of intravenous versus subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy. J Clin Immunol. 2000;20(2):94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shehata N, Palda V, Bowen T, et al. The use of immunoglobulin therapy for patients with primary immune deficiency: an evidence-based practice guideline. Transfus Med Rev. 2010;24(Suppl 1):S28-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro RS. Why I use subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG). J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(Suppl 2):S95–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger M. Subcutaneous administration of IgG. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2008;28(4):779–802, viii. 10.1016/j.iac.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardulf A, Nicolay U, Math D, Asensio O, et al. Children and adults with primary antibody deficiencies gain quality of life by subcutaneous IgG self-infusions at home. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(4):936–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kittner JM, Grimbacher B, Wulff W, Jäger B, Schmidt RE. Patients’ attitude to subcutaneous immunoglobulin substitution as home therapy. J Clin Immunol. 2006;26(4):400–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicolay U, Kiessling P, Berger M, et al. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in North American patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases receiving subcutaneous IgG self-infusions at home. J Clin Immunol. 2006;26(1):65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallick R, Jolles S, Kanegane H, Agbor-Tarh D, Rojavin M. Treatment satisfaction with subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in patients with primary immunodeficiency: a pooled analysis of six Hizentra® studies. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38(8):886–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobrynski L. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy: a new option for patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases. Biologics. 2012;6:277–87. 10.2147/BTT.S25188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallick R, Henderson T, Lahue BJ, Kafal A, Bassett P, Scalchunes C. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin in primary immunodeficiency—impact of training and infusion characteristics on patient-reported outcomes. BMC Immunol. 2020;21(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin A, Lavoie L, Goetghebeur M, Schellenberg R. Economic benefits of subcutaneous rapid push versus intravenous immunoglobulin infusion therapy in adult patients with primary immune deficiency. Transfus Med. 2012;23(1):55–60. 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Immune Deficiency Foundation. Patient reported outcomes and treatment survey. 2017. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-03.html. Accessed 12 Oct 2023.

- 20.Immune Deficiency Foundation. 2018 national treatment survey. https://primaryimmune.org/sites/default/files/IDF-2018-Treatment-Survey.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2023.

- 21.Luthra R, Quimbo R, Iyer R, Luo M. An analysis of intravenous immunoglobin site of care: home versus outpatient hospital. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2014;6(2):e41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallick R, Carlton R, Van Stiphout J. A budget impact model of maintenance treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy with IgPro20 (Hizentra) relative to intravenous immunoglobulins in the United States. Pharmacoecon Open. 2023;7(2):243–55. 10.1007/s41669-023-00386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardulf A, Jonsson G. A comparison of the patient-borne costs of therapy with gamma globulin given at the hospital or at home. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1995;11(2):345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Högy B, Keinecke HO, Borte M. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of immunoglobulin treatment in patients with antibody deficiencies from the perspective of the German statutory health insurance [published correction appears in Eur J Health Econ. 2005 Sep;6(3):243] [published correction appears in Eur J Health Econ. 2008 May;9(2):203]. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6(1):24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, Albon E, Hyde C. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of immunoglobulin replacement therapy for primary immunodeficiency and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a systematic review and economic evaluation. University of Birmingham. 2005. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-mds/haps/projects/WMHTAC/REPreports/2005/IgRT.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2023.

- 26.Beauté J, Levy P, Millet V, et al. Economic evaluation of immunoglobulin replacement in patients with primary antibody deficiencies. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160(2):240–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kafal A, Vinh D, Langelier M. Prefilled syringes for immunoglobulin G (IgG) replacement therapy: clinical experience from other disease settings. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2018;15(12):1199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vermeire S, D’Heygere F, Nakad A, et al. Preference for a prefilled syringe or an auto-injection device for delivering golimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized crossover study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1193–202. 10.2147/PPA.S154181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingle RG, Agarwal AS. Pre-filled syringe—a ready-to-use drug delivery system: a review. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11(9):1391–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jezek J, Darton NJ, Derham BK, Royle N, Simpson I. Biopharmaceutical formulations for pre-filled delivery devices. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013. 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makwana S, Basu B, Makasana Y, Dharamsi A. Prefilled syringes: an innovation in parenteral packaging. Int J Pharm Investig. 2011;1(4):200–6. 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. The AMCP Format for Formulary Submissions 5.0. April 2024. https://www.amcp.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/AMCP-Format-5.0-JMCP-web_0.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. Budget impact analysis—principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health. 2014;17(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 2023 ASP Pricing File. July 2023 Pricing File. Effective July 1, 2023 through September 30, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/2023-asp-drug-pricing-files. Accessed 19 Jun 2023.

- 35.Red Book Online. IBM Micromedex. 2022. https://www.ibm.com/products/micromedex-red-book. Accessed 20 Jul 2023.

- 36.AMCP Pharmaceutical Payment Methods, 2013 Update. https://www.amcp.org/guide-pharmaceutical-payment-methods. Accessed 28 Nov 2022.

- 37.Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Gu Q, Afful J, Ogden CL, National Center for Health Statistics. Anthropometric reference data for children and adults: United States, 2015–2018. Vital Health Stat. 2021;36:1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallick R, Solomon G, Bassett P, et al. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in patients with immunodeficiencies—impact of drug packaging and administration method on patient-reported outcomes. BMC Immunol. 2024;25:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slen B. Infused therapies: cost savings benefits through home infusion. Pharm Times. 2014;5(1):24–5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated Interim Report to Congress. Evaluation of the Medicare Patient Intravenous Immunoglobulin Demonstration Project. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/data-and-reports/2022/ivig-updatedintrtc. Accessed 5 Jan 2025.

- 41.United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index (CPI). https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm. Accessed 1 Aug 2023.

- 42.Haddad E, Berger M, Wang E, et al. Higher doses of subcutaneous IgG reduce resource utilization in patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(2):281–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gamunex-C prescribing information. Grifols Therapeutics Inc.; 2017. https://www.gamunex-c.com/documents/648456/5516391/Gamunex-C+Prescribing+Information.pdf/28391fe7-086f-b112-0bd4-9738108cd159?t=1688982731791.

- 44.Krishnarajah G, Lehmann J, Ellman B, et al. Evaluating dose ratio of subcutaneous to intravenous immunoglobulin therapy among patients with primary immunodeficiency disease switching to 20% subcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22:S475–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuvitru prescribing information. Baxalta US Inc.; 2018. https://www.shirecontent.com/PI/PDFS/Cuvitru_USA_ENG.pdf.

- 46.HyQvia prescribing information. Baxalta US Inc.; 2016. https://www.shirecontent.com/PI/PDFs/HYQVIA_USA_ENG.pdf.

- 47.Xembify prescribing information. Grifols Therapeutics LLC; 2020. https://www.xembify.com/documents/648456/5516391/Xembify+Prescribing+Information.pdf/2aadd7f4-7056-226b-ea44-b7abc6a69e9d?t=1728904722502.

- 48.Cutaquig prescribing information. Octapharma; 2021. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=12505.

- 49.Younger ME, Aro L, Blouin W, Duff C, et al. Nursing guidelines for administration of immunoglobulin replacement therapy. J Infus Nurs. 2013;36(1):58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burns L, Pauly M. Integrated delivery networks: a detour on the road to integrated health care? Health Aff. 2002;21(4):128–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Espanol T, Prevot J, Drabwell J, Sondhi S, Olding L. Improving current immunoglobulin therapy for patients with primary immunodeficiency: quality of life and views on treatment. Patient Prefer Adhere. 2014;2014(8):621–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barton JC, Barton JC, Bertoli LF. Implanted ports in adults with primary immunodeficiency. J Vasc Access. 2018;19(4):375–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kearns S, Kristofek L, Bolgar W, Seidu L, Kile S. Clinical profile, dosing, and quality-of-life outcomes in primary immune deficiency patients treated at home with immunoglobulin G: data from the IDEaL patient registry. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(4):400–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hizentra prescribing information. CSL Behring LLC; 2020. https://labeling.cslbehring.com/PI/US/Hizentra/EN/Hizentra-Prescribing-Information.pdf.

- 55.Windegger TM, Nghiem S, Nguyen KH, Fung YL, Scuffham PA. Primary immunodeficiency disease: a cost-utility analysis comparing intravenous vs subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in Australia. Blood Transfus. 2020;18(2):96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Striesow F, Brandt A. Preference, satisfaction and usability of subcutaneously administered methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis: results of a postmarketing surveillance study with a high-concentration formulation. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2012;4(1):3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Physician fee schedule search. https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx. Accessed 18 Jan 2023.

- 58.United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Economic news release. Table B-3: average hourly and weekly earnings of all employees on private nonfarm payrolls by industry sector, seasonally adjusted. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t19.htm. Accessed 2 Oct 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.