Abstract

Twenty symmetrical chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives were designed and synthesized by reflux (RF) and microwave-assisted (MW) methods. The MW method achieved superior yields (88–95%) in less time (15–30 min) compared to RF (78–86%, 12–24 h), particularly for 3-Cl and 3,4-diCl derivatives with piperidine or diethylamine, due to rapid, uniform heating, enhancing nucleophilic substitution and minimizing side reactions. In particular, compounds 2c (IC50 = 4.14 μM for MCF7, 7.87 μM for C26), 3c (IC50 = 4.98 μM for MCF7, 3.05 μM for C26), and 4c (IC50 = 6.85 μM for MCF7, 1.71 μM for C26) exhibited potent cytotoxic activity with 4c (2,4-diCl, pyrrolidine) surpassing paclitaxel (IC50 = 2.30 μM for C26), and 3c (3,4-diCl, pyrrolidine) rivaling global analogs. Compounds 2f (IC50 = 11.02 μM for MCF7, 4.62 μM for C26) and 3f (IC50 = 5.11 μM for MCF7, 7.10 μM for C26) also showed strong cytotoxicity. QSAR analysis revealed that electron-withdrawing groups (chloro, dichloro) and pyrrolidine enhance C26 potency via improved lipophilicity and π–π stacking, outperforming piperazine and morpholine. Pharmacokinetically, 2c, 3c, and 4c matched Bimiralisib's absorption profiles, surpassing Gefitinib, with 4c showing superior metabolic stability. Compounds 2f and 3c emerged as promising multi-targeted kinase inhibitors, with binding affinities (−7.8 to −9.1 kcal mol−1) closely rivaling Gefitinib, Pazopanib, and Bimiralisib for EGFR, VEGFR2, and PI3K, driven by balanced polar and hydrophobic interactions. Therefore, these findings underscore the potential of 2f and 3c as multi-targeted kinase inhibitors, warranting further mechanistic studies and structural optimization to enhance MCF7 efficacy and reduce toxicity for clinical advancement.

Chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives were synthesized and tested for anticancer activity against MCF7 and C26 cells. Promising compounds showed therapeutic potential and favorable drug-like properties via in silico docking and ADMET analyses.

1. Introduction

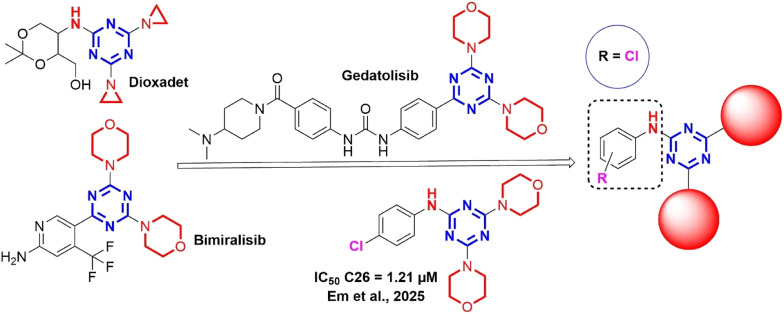

Heterocyclic compounds, particularly those with five- and six-membered rings, demonstrate a broad spectrum of pharmacological potential.1–7 Among these, the s-triazine core stands out as a critical pharmacophore, driving the development of novel therapeutics with diverse biological effects, including antiviral,8 antibacterial,9,10 antifungal,9,10 anti-inflammatory,11,12 antimalarial,13,14 and anticancer activities.15–28 In addition, the diverse anticancer properties of s-triazine derivatives against leukemia, breast cancer, colon cancer, and cervical cancer have attracted considerable research interest.8 Notably, several s-triazine-based drugs with symmetrical structure have emerged as pivotal contributions to global oncology, including Altretamine (anti-ovarian cancer), Tretamine (antineoplastic), Gedatolisib (anti-ovarian cancer, anti-breast cancer, and anti-endometrial cancer), and Bimiralisib (anti-breast cancer).23 These advancements underscore the s-triazine nucleus as a cornerstone in the rational design of targeted cancer therapies (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Anticancer drugs containing s-triazine nucleus with symmetrical structure.

A common approach in the synthesis of symmetrical s-triazine derivatives is the stepwise substitution of 2,4,6-halogenated s-triazines, such as cyanuric chloride, with nucleophiles such as amines, alcohols, or thiols. This method provides precise control over the substitution patterns by exploiting the differential reactivity of chlorine atoms at different temperatures, enabling the sequential introduction of identical substituents to achieve symmetry. In addition, the synthesis from cyanuric chloride stands out due to its operational simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and versatility, especially the possibility of microwave-assisted synthesis to enhance reaction efficiency and yield. Furthermore, this method facilitates the production of high yields of symmetrically substituted s-triazines with excellent reproducibility, making it particularly advantageous for both laboratory-scale experiments and industrial applications.23,29

1.1. Rational drug design

Symmetrical s-triazine derivatives incorporating two saturated cyclic amino groups have emerged as a promising strategy in the development of targeted anticancer therapies, inspired by clinically established s-triazine-based drugs such as Altretamine, Tretamine, Gedatolisib (PI3K/mTOR inhibitor), and Bimiralisib (pan-PI3K inhibitor) (Fig. 2). Our published study revealed that symmetrical phenylamino-s-triazine derivatives bearing electron-withdrawing groups, such as 4-halogeno (e.g., –Cl) or 4-nitro (–NO2), on the benzene ring tend to exhibit the most potent cytotoxic activity.23 For example, 4-chlorophenyl and morpholine substituted triazine analogue not only showed strong activity against C26 (colon carcinoma) with IC50 value of 1.21 μM but also demonstrated significantly lower toxicity on normal BAEC cells compared to standard drugs like paclitaxel and doxorubicin,23 suggesting a better therapeutic index. Therefore, the rational design of new symmetrical chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives focuses on replacing the symmetrical triazine ring with saturated cyclic amines, such as piperidine and its derivatives, piperazine and its derivatives, pyrrolidine, or morpholine, to balance lipophilicity, reduce toxicity, and improve cellular uptake. These groups enhance hydrogen bonding and stereospecific interactions with target enzymes or receptors, as seen in Gedatolisib and Bimiralisib, while maintaining synthetic accessibility through nucleophilic substitution on the cyanuric chloride.23

Fig. 2. Rational design of symmetrical chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives from anticancer drugs and the potent compound.

In addition, the strategic incorporation of chlorine (Cl) substituents in the rational drug design of symmetrical s-triazine derivatives plays a key role in enhancing anticancer potency. Compared to other halogens, chlorine strikes an optimal balance between reactivity and stability, avoiding the excessive instability of fluorine or the bulkiness of bromine, making it ideal for iterative drug optimization. The electron-withdrawing nature of chlorine enhances the electrophilicity of the benzene ring, thereby facilitating interactions with nucleophilic sites on biological targets, such as DNA or proteins involved in cancer cell proliferation. This modification influences the lipophilicity of the compound, improving bioavailability and cellular uptake, which are important factors for effective anticancer agents. Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated that chlorine substitution at specific positions on the benzene ring, particularly para- or meta-, optimizes cytotoxic activity against various cancer cell lines, including breast and lung carcinomas.30–32 These findings underscore the strategic importance of chlorine in fine-tuning the physicochemical and pharmacological properties of phenylamino-s-triazine derivatives for anticancer applications.

The strategic design of symmetrical s-triazine derivatives, incorporating one chlorophenylamino group and two saturated cyclic amino substituents, represents a robust approach to developing potent anticancer agents, driven by their tailored chemical and pharmacological properties. The chlorophenylamino moiety, characterized by its electron-withdrawing chlorine atom, enhances the lipophilicity of the triazine core and fine-tunes its electronic profile, enabling precise interactions with hydrophobic regions of target proteins, such as receptor tyrosine kinases. The incorporation of saturated cyclic amino groups, such as piperidine, piperazine, or morpholine, optimizes hydrogen-bonding interactions and steric fit, thereby improving binding affinity and target selectivity. Key therapeutic targets for these derivatives include the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway, as exemplified by Gedatolisib, where cyclic amines enhance aqueous solubility and receptor engagement, demonstrating efficacy in ovarian and breast cancers.33,34 Additionally, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) are promising targets, as the chlorophenylamino group may facilitate specific binding to kinase domains, disrupting oncogenic signaling cascades.35–37 The balanced lipophilicity and solubility conferred by the combination of chlorophenylamino and cyclic amino groups enhance the derivatives' ability to circumvent multidrug resistance mechanisms, such as efflux pumps. Leveraging structure–activity relationship (SAR) analyses and computational modeling, these s-triazine derivatives can be optimized for specific oncogenic pathways, providing a versatile platform for the development of next-generation anticancer therapeutics.

This study aimed to synthesize a series of symmetrical chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives incorporating diverse saturated cyclic amino groups and to assess their anticancer efficacy against MCF7 (human breast cancer) and C26 (colon carcinoma) cell lines. The synthesized compounds were evaluated for their cytotoxic potential, with promising candidates selected for further in silico molecular docking and ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) analyses. These investigations seek to elucidate the compounds' interactions with key molecular targets and their pharmacokinetic profiles, providing insights into their therapeutic potential and drug-likeness.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

Mono-substituted s-triazine derivatives (yield: 95–97%) were synthesized via a nucleophilic substitution reaction between 4-substituted aniline derivatives and cyanuric chloride in tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent, catalyzed by solid potassium carbonate (K2CO3) at a controlled low temperature (0–5 °C). This temperature range ensured selective substitution of the first chlorine atom, enhancing reaction specificity. Subsequently, tri-substituted s-triazine derivatives (or chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives) were obtained through nucleophilic substitution of the remaining two chlorine atoms on the mono-substituted s-triazine derivatives with saturated amines. These reactions were conducted in 1,4-dioxane with solid K2CO3 as the base, employing two distinct approaches: conventional reflux (RF) and microwave-assisted (MW) methods (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives (MW – microwave irradiation, RF – reflux, THF – tetrahydrofuran).

The reaction yields of chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives using RF and MW methods showed marked differences between different R and R1 substituents. The MW method consistently outperformed the RF method by 8–13% and achieved higher yields (88–95%) compared to reflux yields (78–86%) across all compounds (2a–4f) (Table 1). The microwave method's efficacy stems from its ability to deliver rapid, uniform heating, which accelerates reaction kinetics, enhances nucleophilic substitution on the s-triazine core, and minimizes side reactions. This results in improved product purity and yield, particularly for compounds with R groups of 3-Cl (e.g., 2a, 95%) and 3,4-diCl (e.g., 3a, 95%) paired with R1 groups of piperidine (Piper) or diethylamine (Dieth). For group R, compounds with 3-Cl (89–95%), 3,4-diCl (88–95%), and 2,4-diCl (88–93%) substitutions showed similar yield trends. However, regarding R1 groups, piperidine (Piper) and diethylamine (Dieth) derivatives (e.g., 2a, 2g, 3a, 3g, 4a) consistently exhibit higher yields in both methods, likely due to their favorable steric and electronic properties, which enhance nucleophilic substitution on the s-triazine core. Conversely, morpholine (Mor) derivatives (e.g., 2d, 3d, 4d) show the lowest yields (78–88%), potentially due to reduced nucleophilicity (Table 1). These findings align closely with those reported by Al-Zaydi et al. (2017), who utilized 4-carboxyaniline as the starting material for tri-substitution reactions with saturated cyclic amines (piperidine and morpholine) in a 1 : 1 mixture of 1,4-dioxane and water, using sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) as the base. Their study achieved yields of 74.5–85.8% over 8–10 h under RF conditions, and 88–93.1% in 10 min using MW irradiation at 400 W.38 In particular, our published research highlights the superior yields of the MW method in synthesizing tri-substituted s-triazine derivatives (R = 4-Cl, 4-F, 4-OCH3, 4-CH3, 4-NO2; R1 = Piper, Mor), achieving excellent yields (91–98%) and rapid reaction times (15–30 min). In contrast, the RF method required significantly longer reaction times (12–24 h) and lower yields (80–88%).23 Therefore, these findings underscore the advantages of the MW method (“green” approach) in terms of efficiency, speed, and environmental protection, offering a scalable, efficient, and environmentally friendly approach for producing potential anticancer agents.

Table 1. Yields and physicochemical parameters of chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives (2a–2g, 3a–3g and 4a–4f).

| Entry | R group | Code | Physicochemical parametersa | Yield (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | R1 | RF | MW | ||||

| 1 | 3-Cl | Piper | 2a | MWt: 372.90 | MR: 113.28 | 84 | 95 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 5.08 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −5.43 | ||||||

| 2 | 3-Cl | 4-MePiper | 2b | MWt: 400.95 | MR: 122.89 | 82 | 91 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 5.95 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −6.13 | ||||||

| 3 | 3-Cl | Pyrro | 2c | MWt: 344.84 | MR: 103.66 | 82 | 94 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 4.37 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −4.84 | ||||||

| 4 | 3-Cl | Mor | 2d | MWt: 376.84 | MR: 105.83 | 84 | 92 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 2.64 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 75.64 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −3.92 | ||||||

| 5 | 3-Cl | 4-MePipera | 2e | MWt: 402.92 | MR: 126.90 | 79 | 89 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 3.01 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 63.66 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −4.29 | ||||||

| 6 | 3-Cl | Pipera | 2f | MWt: 374.87 | MR: 117.10 | 82 | 95 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 2.08 | ||||||

| n HD: 3 | TPSA: 81.24 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −3.55 | ||||||

| 7 | 3-Cl | Dieth | 2g | MWt: 348.87 | MR: 102.02 | 85 | 94 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 4.86 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 8 | Log S: −4.91 | ||||||

| 8 | 3,4-diCl | Piper | 3a | MWt: 407.34 | MR: 118.29 | 82 | 95 |

| n HA: 6 | Log P: 5.71 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −6.03 | ||||||

| 9 | 3,4-diCl | 4-MePiper | 3b | MWt: 435.39 | MR: 127.90 | 79 | 90 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 6.58 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −6.73 | ||||||

| 10 | 3,4-diCl | Pyrro | 3c | MWt: 379.29 | MR: 108.67 | 80 | 90 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 4.99 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −5.43 | ||||||

| 11 | 3,4-diCl | Mor | 3d | MWt: 411.29 | MR: 110.84 | 78 | 88 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 3.27 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 75.64 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −4.51 | ||||||

| 12 | 3,4-diCl | 4-MePipera | 3e | MWt: 437.37 | MR: 131.91 | 86 | 94 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 3.64 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 63.66 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −4.89 | ||||||

| 13 | 3,4-diCl | Pipera | 3f | MWt: 409.32 | MR: 122.11 | 83 | 92 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 2.71 | ||||||

| n HD: 3 | TPSA: 81.24 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −4.15 | ||||||

| 14 | 3,4-diCl | Dieth | 3g | MWt: 383.32 | MR: 107.03 | 83 | 95 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 5.48 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 8 | Log S: −5.50 | ||||||

| 15 | 2,4-diCl | Piper | 4a | MWt: 407.34 | MR: 118.29 | 82 | 90 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 5.71 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −6.03 | ||||||

| 16 | 2,4-diCl | 4-MePiper | 4b | MWt: 435.39 | MR: 127.90 | 83 | 92 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 6.58 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −6.73 | ||||||

| 17 | 2,4-diCl | Pyrro | 4c | MWt: 379.29 | MR: 108.67 | 81 | 90 |

| n HA: 3 | Log P: 4.99 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 57.18 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −5.43 | ||||||

| 18 | 2,4-diCl | Mor | 4d | MWt: 411.29 | MR: 110.84 | 78 | 88 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 3.27 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 75.64 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −4.51 | ||||||

| 19 | 2,4-diCl | 4-MePipera | 4e | MWt: 437.37 | MR: 131.91 | 82 | 93 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 3.64 | ||||||

| n HD: 1 | TPSA: 63.66 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −4.89 | ||||||

| 20 | 2,4-diCl | Pipera | 4f | MWt: 409.32 | MR: 122.11 | 81 | 90 |

| n HA: 5 | Log P: 2.71 | ||||||

| n HD: 3 | TPSA: 81.24 | ||||||

| n Rot: 4 | Log S: −4.15 | ||||||

Calculated using SwissADME, RF – reflux method (/conventional heating), MW – microwave-assisted methods, MWt – molecular weight, nHA – number of hydrogen bond acceptors, nHD – number of hydrogen bond donors, nRot – number rotatable bonds, TPSA – topological polar surface area (Angstroms squared), MR – molar refractivity, log P – log Po/w (XLOGP3), log S – log S (ESOL).

The chemical structures of chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives were suitably elucidated by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and MS spectroscopy. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives (2a–2g, 3a–3g, 4a–4f) provide critical insights into their structural characteristics, highlighting the influence of varying R and R1 substituents on the s-triazine core. In the 1H NMR spectra, the –NH– proton, linking the chlorophenyl moiety to the triazine ring, consistently appears as a singlet in the range of 8.05–10.76 ppm, with compounds bearing 3,4-dichlorophenyl (9.03–9.41 ppm) and 3-chlorophenyl (9.13–10.76 ppm) groups showing slight downfield shifts compared to 2,4-dichlorophenyl derivatives (8.00–8.31 ppm). This variation reflected the electron-withdrawing effects of additional chlorine atoms, which modulate the electron density around the –NH– group. Aromatic protons (HAr) on the chlorophenyl ring exhibited characteristic splitting patterns, with 3-chlorophenyl derivatives showing a triplet and doublets at δ 6.90–8.16 ppm, while 3,4-dichlorophenyl and 2,4-dichlorophenyl compounds display simplified patterns due to increased substitution, as seen in the doublet at δ 8.35 ppm for 3a. The R1 cyclic amino groups significantly influence aliphatic signals; for instance, pyrrolidine (2a, 3a, 4a) showed distinct –CH2– triplets at δ 3.46–3.49 ppm, whereas morpholine (2d, 3d, 4d), piperazine (2e, 3e, 4e) and its derivatives (2b, 3b, 4b) exhibited additional oxygen/nitrogen-adjacent –CH2– signals at δ 3.59–3.70 ppm, reflecting its heterocyclic nature. Piperidine derivatives (2f, 3f, 4f) display broader –CH2– signals at δ 1.47–3.70 ppm, indicating greater conformational flexibility. In the 13C NMR spectra, the triazine ring carbons resonated at δ 163.1–165.0 ppm, with minor shifts attributed to the electronic effects of R1 substituents. For example, morpholine derivatives (2d, 3d, 4d) showed a characteristic carbon signal at δ 65.9–66.3 ppm for oxygen-linked –CH2–, absent in piperidine or pyrrolidine analogs. The chlorophenyl carbons appear at δ 117.3–142.6 ppm, with 3,4-dichlorophenyl compounds (e.g., 3a) showing a downfield shift (δ 141.0 ppm) compared to 2,4-dichlorophenyl analogs (e.g., 4a, δ 135.4 ppm), reflecting differences in chlorine positioning. Aliphatic carbons of R1 groups, such as pyrrolidine (δ 24.3–24.8 ppm) and piperidine (δ 24.3–25.8 ppm), are consistent across series, while methyl-substituted piperazines (2b, 3b, 4b) introduced additional signals at δ 42.5–54.5 ppm. Moreover, the mass spectrometry analysis revealed the molecular ion peak (M, m/z) for compounds 2–4, corroborating their proposed structures. Notably, all chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives exhibited physicochemical properties, including molecular weights (MWt < 500), consistent with Lipinski's rule of five (Table 1). These characteristics suggest their potential as promising candidates for further drug development.

2.2. In vitro anticancer activity

The cytotoxic activities of a series of compounds (2a–2g, 3a–3g, 4a–4f) were evaluated against MCF7 (human breast cancer) and C26 (murine colon carcinoma) cell lines, with IC50 values indicating the concentration required to inhibit 50% of cell growth (Table 2). These results were benchmarked against paclitaxel (PTX), a standard chemotherapeutic agent. Among the series of 2, compounds 2c and 2f exhibited the highest cytotoxic activities. Compound 2c demonstrated IC50 values of 4.14 ± 1.06 μM (MCF7) and 7.87 ± 0.96 μM (C26), while 2f showed 11.02 ± 0.68 μM (MCF7) and 4.62 ± 0.65 μM (C26). Notably, 2f's activity against C26 approaches that of PTX, suggesting strong potential against colon carcinoma. In contrast, compounds 2a (28.20 ± 1.68 μM for MCF7, 23.05 ± 1.25 μM for C26), 2b (24.37 ± 0.66 μM for MCF7, 20.53 ± 0.65 μM for C26), 2d (38.02 ± 3.85 μM for MCF7, 21.54 ± 0.81 μM for C26), 2e (19.64 ± 1.37 μM for MCF7, 47.53 ± 1.03 μM for C26), and 2g (36.67 ± 1.85 μM for MCF7, 58.17 ± 2.19 μM for C26) displayed significantly higher IC50 values, indicating weaker cytotoxicity. The superior activity of 2c and 2f likely stems from specific structural features enhancing their interaction with cellular targets, such as tubulin, similar to PTX's microtubule-stabilizing mechanism.

Table 2. Anticancer activity of chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives (IC50, μM)a.

| Entry | Code | Cancer cell line | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCF7 (IC50, μM) | C26 (IC50, μM) | ||

| 1 | 2a | 28.20 ± 1.68 | 23.05 ± 1.25 |

| 2 | 2b | 24.37 ± 0.66 | 20.53 ± 0.65 |

| 3 | 2c | 4.14 ± 1.06 | 7.87 ± 0.96 |

| 4 | 2d | 38.02 ± 3.85 | 21.54 ± 0.81 |

| 5 | 2e | 19.64 ± 1.37 | 47.53 ± 1.03 |

| 6 | 2f | 11.02 ± 0.68 | 4.62 ± 0.65 |

| 7 | 2g | 36.67 ± 1.85 | 58.17 ± 2.19 |

| 8 | 3a | 36.02 ± 2.26 | 29.14 ± 2.63 |

| 9 | 3b | 36.33 ± 0.76 | 21.77 ± 1.10 |

| 10 | 3c | 4.98 ± 0.58 | 3.05 ± 0.61 |

| 11 | 3d | 28.36 ± 1.88 | 30.71 ± 4.25 |

| 12 | 3e | 37.38 ± 3.47 | 24.25 ± 1.34 |

| 13 | 3f | 5.11 ± 0.31 | 7.10 ± 0.48 |

| 14 | 3g | 55.62 ± 5.30 | 37.58 ± 0.88 |

| 15 | 4a | 40.85 ± 0.41 | 46.55 ± 1.42 |

| 16 | 4b | 25.09 ± 1.39 | 48.55 ± 1.30 |

| 17 | 4c | 6.85 ± 0.34 | 1.71 ± 0.88* |

| 18 | 4d | 43.03 ± 0.96 | 39.15 ± 2.96 |

| 19 | 4e | 10.05 ± 0.36 | 16.38 ± 0.63 |

| 20 | 4f | 17.04 ± 1.00 | 17.15 ± 0.83 |

| 21 | PTX | 2.48 ± 0.51 | 2.30 ± 0.27 |

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), PTX – paclitaxel, MCF7 – human breast cancer cell line, C26 – colon carcinoma cell line, the values in bold highlight the best compounds with the best IC50 values compared to the positive control, * – statistically significant (p < 0.05) compared to reference drug PTX.

In the series 3 compounds, 3c and 3f stood out as the most potent. Compound 3c exhibited IC50 values of 4.98 ± 0.58 μM (MCF7) and 3.05 ± 0.61 μM (C26), with its C26 activity closely rivaling PTX. Compound 3f showed IC50 values of 5.11 ± 0.31 μM (MCF7) and 7.10 ± 0.48 μM (C26), also indicating strong cytotoxicity. Other compounds, including 3a (36.02 ± 2.26 μM for MCF7, 29.14 ± 2.63 μM for C26), 3b (36.33 ± 0.76 μM for MCF7, 21.77 ± 1.10 μM for C26), 3d (28.36 ± 1.88 μM for MCF7, 30.71 ± 4.25 μM for C26), 3e (37.38 ± 3.47 μM for MCF7, 24.25 ± 1.34 μM for C26), and 3g (55.62 ± 5.30 μM for MCF7, 37.58 ± 0.88 μM for C26), showed moderate to low activity, with IC50 values 10- to 20-fold higher than PTX. The potency of 3c and 3f suggests favorable molecular interactions, possibly involving enhanced binding affinity to apoptotic or mitotic pathways.

Series 4 compounds revealed 4c and 4e as the most effective. Compound 4c was particularly notable, with IC50 values of 6.85 ± 0.34 μM (MCF7) and 1.71 ± 0.88 μM (C26), the latter surpassing PTX's potency against C26. Compound 4e showed IC50 values of 10.05 ± 0.36 μM (MCF7) and 16.38 ± 0.63 μM (C26), indicating moderate activity. Other compounds, such as 4a (40.85 ± 0.41 μM for MCF7, 46.55 ± 1.42 μM for C26), 4b (25.09 ± 1.39 μM for MCF7, 48.55 ± 1.30 μM for C26), 4d (43.03 ± 0.96 μM for MCF7, 39.15 ± 2.96 μM for C26), and 4f (17.04 ± 1.00 μM for MCF7, 17.15 ± 0.83 μM for C26), exhibited lower potency. The exceptional activity of 4c, particularly against C26, suggests a highly optimized structure for targeting colon carcinoma cells, potentially through mechanisms akin to PTX's disruption of microtubule dynamics.

PTX remains the gold standard with IC50 values of 2.48 ± 0.51 μM (MCF7) and 2.30 ± 0.27 μM (C26). Among the tested compounds, 4c stands out as the only compound surpassing PTX's potency against C26, while 3c and 2f closely approach it. Against MCF7, compounds 2c, 3c, and 3f showed promising activity but remain less potent than PTX. The weaker performance of most compounds, particularly 2g, 3g, 4a, and 4d, underscores the challenge of achieving PTX's broad-spectrum efficacy. Structural modifications in 2c, 3c, 3f, and 4c likely enhance their cytotoxic potential, possibly by improving solubility, cellular uptake, or target specificity, but further studies are needed to elucidate their mechanisms and optimize their activity to match or exceed PTX.

In conclusion, compounds 2c (3-Cl, pyrrrolidine), 2f (3-Cl, piperazine), 3c (3,4-diCl, pyrrrolidine), 3f (3,4-diCl, piperazine), and 4c (2,4-diCl, pyrrrolidine) exhibited significant cytotoxic potential, with 4c showing superior activity against C26 compared to PTX (Fig. 3). The results also suggested that the R1 substituents such as pyrrolidine and piperazine in these derivatives may be responsible for their potential cytotoxic activity. These compounds warrant further investigation for structural optimization and mechanism studies to enhance their efficacy, especially against MCF7 cells, where PTX still retains a clear advantage.

Fig. 3. The IC50 values (μM) of potential chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives compared to paclitaxel (PTX) (MCF7 – human breast cancer cell line, C26 – colon carcinoma cell line).

2.3. Structure–activity relationships (SAR)

The cytotoxic activities of five s-triazine derivatives (2c, 2f, 3c, 3f, and 4c) against MCF7 and C26 cell lines were compared with structurally analogous s-triazine derivatives reported globally to elucidate their anticancer potential and establish quantitative structure–activity relationships (QSAR). Compound 2c, with 3-chlorophenyl and pyrrolidine (IC50: 4.14 μM for MCF7, 7.87 μM for C26) outperformed 4-bromophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives with pyrazolyl and morpholino groups (IC50: 4.53 μM for MCF7),39 likely due to the pyrrolidine groups enhancing molecular flexibility and hydrophobic interactions with cellular targets like tubulin. Compound 2f, with piperazine substitutions (IC50: 11.02 for MCF7, 4.62 μM for C26) showed superior C26 activity compared to 4,6-dimorpholino-s-triazine with a 4-acylphenylamino group (IC50: 8.71 μM for SW620),20 suggesting that piperazine enhances colon cancer specificity, possibly via increased hydrogen bonding. Compound 3c, with 3,4-dichlorophenyl and pyrrolidine (IC50: 4.98 μM for MCF7, 3.05 μM for C26) rivaled 4-bromo/4-chlorophenylamino-s-triazines with indol-3-ylpyrazolyl groups (IC50: 2–4 μM for MCF7),18 with its dichlorophenyl group likely strengthening π–π stacking and electron-withdrawing effects, enhancing C26 potency. Compound 3f, with piperazine groups (IC50: 5.11 μM for MCF7, 7.10 μM for C26), is less effective against C26 than 3c, aligning with findings that pyrrolidine outperforms piperazine in colon cancer models. Compound 4c, with 2,4-dichlorophenyl and pyrrolidine (IC50: 6.85 μM for MCF7, 1.71 μM for C26), surpassed the 4-bromophenylamino-s-triazine (IC50 : 0.50 μM for HCT-116),39 with the ortho-chlorine likely optimizing steric and electronic interactions for exceptional C26 activity. QSAR analysis reveals that electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., chloro, dichloro) on the phenyl ring enhance cytotoxicity, particularly against C26, as seen in 4-halogeno and 4-nitro substituted triazines.23 Pyrrolidine substitutions consistently improve potency over piperazine, likely due to increased lipophilicity and reduced steric hindrance, while dichlorophenyl groups amplify activity compared to monochlorophenyl, correlating with higher electron-withdrawing capacity. Compared to sulfaguanidine-triazines (IC50: 14.8–33.2 μM for MCF7),21 these compounds exhibited superior potency, though less toxic than doxorubicin (IC50: 0.42 μM),18 suggesting a favorable therapeutic index.

Compared more specifically with our published research, in examining the cytotoxic activities of five chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives (2c, 2f, 3c, 3f, and 4c) against MCF7 and C26 cell lines, these compounds generally exhibited superior potency compared to the three phenylamino-s-triazine analogs (P-2e (4-nitrophenyl and piperidine substituted triazine), P-3a (4-chlorophenyl and morpholine substituted triazine), and P-3e (4-nitrophenyl and morpholine substituted triazine)), as evidenced by their lower IC50 values. For the MCF7 line, the potent chlorophenyl series displayed IC50 ranges from 4.14 ± 1.06 μM (2c) to 11.02 ± 0.68 μM (2f), markedly outperforming the phenyl series, which spans 13.74 ± 1.96 μM (P-3e) to 42.40 ± 4.48 μM (P-3a), suggesting that chlorine substitution on the phenyl ring enhances selectivity and efficacy against this estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer model, potentially through improved lipophilicity or π–π stacking interactions with cellular targets. In contrast, on the C26 line, the chlorophenyl compounds yield IC50 values from 1.71 ± 0.88 μM (4c) to 7.87 ± 0.96 μM (2c), overlapping with but not consistently surpassing the phenyl analogs (1.21 ± 0.47 μM for P-3a to 14.66 ± 1.70 μM for P-3e), indicating a more variable response where certain chlorine positions, such as the 2,4-dichloro motif in 4c, confer exceptional activity possibly via steric hindrance or altered electron withdrawal affecting membrane permeability.

In summary, QSAR analysis of chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives underscores the pivotal role of strategic substitutions in modulating cytotoxic efficacy against MCF7 breast cancer and C26 colon cancer cell lines. Electron-withdrawing chloro groups on the phenyl ring, particularly in di-substituted configurations such as 3,4-dichloro (3c) and 2,4-dichloro (4c), significantly enhance potency against C26. Moreover, pyrrolidine moieties consistently outperform piperazine counterparts and tend to favor lower IC50 on MCF7 compared to piperazine, as seen in the superior activity of 2c and 3c over 2f and 3f, attributable to enhanced molecular flexibility, reduced steric hindrance, and stronger hydrophobic engagements, while piperazine confers selective hydrogen-bonding advantages in colon cancer models. While less potent than doxorubicin, their favorable therapeutic indices position compounds like 4c and 3c as promising scaffolds for lead optimization, warranting deeper mechanistic investigations into tubulin-binding dynamics and in vivo pharmacokinetics to advance anticancer therapeutics.

2.4. In silico ADMET profile

The in silico ADMET profile of the five potent compounds and reference drugs Gedatolisib (Ged) and Bimiralisib (Bim) is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. ADMET profile of the active compounds and reference drugsa.

| Parameter | 2c | 2f | 3c | 3f | 4c | Ged | Bim | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Druglikeness | ||||||||||||||

| Lipinski | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |||||||

| Ghose | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||||

| Veber | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Egan | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Muegge | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |||||||

| Pfizer | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Bioavailability score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.17 | 0.55 | |||||||

| SAscore | <6 | E | <6 | E | <6 | E | <6 | E | <6 | E | <6 | E | <6 | E |

| Absorption | ||||||||||||||

| Caco-2 permeability | −4.883 | E | −5.283 | P | −5.105 | E | −5.569 | P | −4.942 | E | −5.322 | P | −4.546 | E |

| MDCK permeability | 0 | E | 0 | E | 0 | E | 0 | E | 0 | E | 0.0 | E | 0 | E |

| PAMPA | −−− | E | −− | E | −−− | E | − | M | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E |

| Pgp-inhibitor | +++ | P | −−− | E | +++ | P | −−− | E | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P |

| Pgp-substrate | −−− | E | +++ | P | −−− | E | +++ | P | −−− | E | +++ | P | −−− | E |

| HIA | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E |

| F 20% | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E |

| F 30% | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E | −−− | E |

| F 50% | +++ | P | ++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | −− | E | +++ | P | −−− | E |

| Distribution | ||||||||||||||

| PPB (%) | 99.60 | P | 78.00 | E | 99.60 | P | 79.50 | E | 99.50 | P | 76.5 | E | 94.20 | P |

| VDss (L kg−1) | 3.546 | E | 6.224 | E | 4.144 | E | 5.6750 | E | 3.3880 | E | 2.6600 | E | 2.576 | E |

| BBB penetration | −−− | E | − | M | − | M | ++ | P | + | M | −−− | E | ++ | P |

| Fu (%) | 0.30 | P | 20.50 | E | 0.30 | P | 16.40 | E | 0.40 | P | 18.0 | E | 6.30 | E |

| OATP1B1 inhibitor | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | ++ | P |

| OATP1B3 inhibitor | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P |

| BCRP inhibitor | +++ | P | −−− | P | ++ | P | −−− | P | + | M | −−− | P | −−− | P |

| MRP1 inhibitor | ++ | P | ++ | P | − | M | − | M | +++ | P | − | M | +++ | P |

| BSEP inhibitor | +++ | P | + | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | +++ | P | − | P |

| Metabolism | ||||||||||||||

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||

| CYP1A2 substrate | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | −−− | −−− | |||||||

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | −− | −−− | ++ | − | − | −−− | −−− | |||||||

| CYP2C19 substrate | −−− | +++ | −− | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | −−− | ++ | |||||||

| CYP2C9 substrate | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | +++ | |||||||

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | ++ | −−− | +++ | −− | − | −−− | −−− | |||||||

| CYP2D6 substrate | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | |||||||

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | −− | +++ | + | +++ | − | −−− | −−− | |||||||

| CYP3A4 substrate | −−− | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | −−− | |||||||

| CYP2B6 inhibitor | +++ | −−− | +++ | −−− | +++ | +++ | −−− | |||||||

| CYP2B6 substrate | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | −−− | |||||||

| CYP2C8 inhibitor | +++ | ++ | +++ | −− | −−− | −− | −−− | |||||||

| HLM stability | − | M | −− | P | + | M | −−− | P | ++ | E | −−− | P | −−− | P |

| Excretion | ||||||||||||||

| CLplasma (mL min−1 kg−1) | 4.52 | E | 4.222 | E | 4.72 | E | 4.293 | E | 5.437 | M | 5.329 | M | 5.41 | M |

| T 1/2 | 0.609 | 0.47 | 0.82 | 0.65 | 0.682 | 0.297 | 0.926 | |||||||

| Toxicity | ||||||||||||||

| hERG blockers | 0.663 | M | 0.953 | P | 0.728 | P | 0.965 | P | 0.639 | M | 0.949 | P | 0.272 | E |

| hERG blockers (10 μm) | 0.846 | P | 0.868 | P | 0.872 | P | 0.890 | P | 0.856 | P | 0.337 | M | 0.359 | M |

| DILI | 0.772 | P | 0.990 | P | 0.845 | P | 0.994 | P | 0.832 | P | 0.998 | P | 0.985 | P |

| AMES toxicity | 0.167 | E | 0.264 | E | 0.145 | E | 0.234 | E | 0.125 | E | 0.545 | M | 0.503 | M |

| Rat oral acute toxicity | 0.202 | E | 0.720 | P | 0.237 | E | 0.756 | P | 0.263 | E | 0.289 | E | 0.428 | M |

| FDAMDD | 0.521 | M | 0.330 | P | 0.541 | M | 0.350 | M | 0.473 | M | 0.457 | M | 0.212 | E |

| Skin sensitization | 0.420 | M | 0.922 | P | 0.462 | M | 0.932 | P | 0.275 | E | 0.635 | M | 0.286 | E |

| Carcinogenicity | 0.652 | M | 0.149 | E | 0.670 | M | 0.162 | E | 0.709 | P | 0.947 | P | 0.955 | P |

| Eye corrosion | 0 | E | 0.088 | E | 0.001 | E | 0.124 | E | 0.001 | E | 0.0 | E | 0 | E |

| Eye irritation | 0.57 | M | 0.743 | P | 0.416 | M | 0.608 | M | 0.343 | M | 0.0 | E | 0.423 | M |

| Respiratory toxicity | 0.484 | M | 0.998 | P | 0.463 | M | 0.998 | P | 0.487 | M | 0.791 | P | 0.733 | P |

| Human hepatotoxicity | 0.782 | P | 0.987 | P | 0.766 | P | 0.986 | P | 0.805 | P | 0.986 | P | 0.967 | P |

| Drug-induced nephrotoxicity | 0.738 | P | 0.999 | P | 0.815 | P | 1 | P | 0.769 | P | 0.997 | P | 0.982 | P |

| Drug-induced neurotoxicity | 0.774 | P | 0.993 | P | 0.844 | P | 0.995 | P | 0.856 | P | 0.991 | P | 0.994 | P |

| Ototoxicity | 0.395 | M | 0.842 | P | 0.479 | M | 0.883 | P | 0.507 | M | 0.864 | P | 0.85 | P |

| Hematotoxicity | 0.238 | E | 0.546 | M | 0.319 | M | 0.642 | M | 0.305 | M | 0.475 | M | 0.323 | M |

| Genotoxicity | 0.925 | P | 0.999 | P | 0.828 | P | 0.999 | P | 0.741 | P | 1.0 | P | 1 | P |

| RPMI-8226 immunotoxicity | 0.073 | E | 0.070 | E | 0.080 | E | 0.076 | E | 0.066 | E | 0.624 | M | 0.36 | M |

| A549 cytotoxicity | 0.617 | M | 0.639 | M | 0.722 | P | 0.738 | P | 0.67 | M | 0.051 | E | 0.074 | E |

| Hek293 cytotoxicity | 0.874 | P | 0.391 | M | 0.9 | P | 0.457 | M | 0.864 | P | 0.749 | P | 0.424 | M |

| BCF | 1.490 | 0.789 | 1.817 | 1.266 | 1.889 | 0.755 | 0.632 | |||||||

| IGC50 | 3.841 | 3.287 | 4.119 | 3.696 | 4.005 | 3.379 | 3.241 | |||||||

| LC50DM | 5.113 | 4.651 | 5.232 | 4.810 | 5.413 | 5.31 | 4.997 | |||||||

| LC50FM | 4.722 | 4.030 | 5.012 | 4.473 | 5.046 | 4.206 | 3.899 | |||||||

Ged – Gedatolisib, Bim – Bimiralisib, Caco-2 permeability (optimal: higher than −5.15 log unit), MDCK permeability (low permeability: <2 × 10−6 cm s−1, medium permeability: 2–20 × 10−6 cm s−1, high passive permeability: >20 × 10−6 cm s−1), PAMPA – the experimental data for Peff was logarithmically transformed (log Peff < 2: low-permeability, log Peff > 2.5: high-permeability), Pgp – P-glycoprotein, HIA – human intestinal absorption (−: ≥30%, +: < 30%), F: bioavailability (+: < percent value, −: ≥ percent value), PPB: plasma protein binding (optimal: < 90%), VD: volume distribution (optimal: 0.04–20 L kg−1), BBB: blood–brain barrier penetration, Fu: the fraction unbound in plasms (low: <5%, middle: 5–20%, high: > 20%), CL : Clearance (low: < 5 mLmin−1kg, moderate: 5–15 mL min−1 kg−1, high: > 15 mL min−1 kg−1), T1/2 (ultra-short half-life drugs: 0.5 – < 1 h; short half-life drugs: 1–4 h; intermediate short half-life drugs: 4–8 h; long half-life drugs: >8 h), hERG blockers (IC50 ≤ 10 μM or ≥ 50% inhibition at 10 μM were classified as hERG +, IC50 > 10 μM or <50% inhibition at 10 μM were classified as hERG −–), DILI: drug-induced liver injury, rat oral acute toxicity (0: low-toxicity > 500 mg kg−1, 1: high-toxicity < 500 mg kg−1), FDAMDD – maximum recommended daily dose, BCF – bioconcentration factors, IGC50 – tetrahymena pyriformis 50 percent growth inhibition Concentration, LC50FM – 96 h fathead minnow 50 percent lethal concentration, LC50DM – 48 h daphnia magna 50 percent lethal concentration. The output value is the probability of being inhibitor/substrate/active/positive/high-toxicity/sensitizer/carcinogens/corrosives/irritants (category 1) or non-inhibitor/non-substrate/inactive/negative/low-toxicity/non-sensitizer/non-carcinogens/noncorrosives/nonirritants (category 0). For the classification endpoints, the prediction probability values are transformed into six symbols: 0–0.1(−−−), 0.1–0.3(−−), 0.3–0.5(−), 0.5–0.7(+), 0.7–0.9(++), and 0.9–1.0(+++). Additionally, the corresponding relationships of the three labels are as follows: E − excellent, M – medium, P – poor.

2.4.1. Druglikeness

The druglikeness of five s-triazine derivatives (2c, 2f, 3c, 3f, and 4c) was evaluated against reference drugs Gedatolisib (Ged) and Bimiralisib (Bim) using established physicochemical and pharmacokinetic filters, including Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan, Muegge, Pfizer, bioavailability score, and synthetic accessibility (SA) score. Compounds 2c, 3c, and 4c, bearing pyrrolidine or dichlorophenyl substitutions, satisfy Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge rules, indicating favorable molecular weight (<500 Da), lipophilicity (log P < 5), hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and topological polar surface area (TPSA < 140 Å2), aligning with characteristics of orally bioavailable drugs. However, these compounds fail the Pfizer rule, suggesting potential toxicity risks due to high lipophilicity or reactive groups, unlike Ged and Bim, which pass the Pfizer rule, indicating lower toxicity potential. Compounds 2f and 3f, with piperazine substitutions, also meet Lipinski, Veber, Egan, and Muegge criteria but fail the Ghose rule, which may limit their pharmacokinetic profiles compared to 2c, 3c, and 4c. All five compounds achieve a bioavailability score of 0.55, matching Bim but surpassing Ged (0.17), suggesting comparable oral absorption potential to Bim, driven by favorable PSA and hydrogen bonding properties. The excellent SAscore across all compounds indicates synthetic feasibility, comparable to Ged and Bim, facilitating potential scale-up for clinical development. Overall, 2c, 3c, and 4c exhibited superior druglikeness compared to Ged, with profiles comparable to Bim, though their Pfizer rule violations warrant further optimization to mitigate potential toxicity while maintaining their promising pharmacokinetic properties.

2.4.2. Adsorption

Compounds 2c, 3c, and 4c exhibited excellent Caco-2 permeability (log Papp: −4.883, −5.105, −4.942, respectively), comparable to Bim (−4.546) and superior to Ged (−5.322) and 2f (−5.283), which are rated poor, suggesting enhanced intestinal epithelial transport, likely due to favorable lipophilicity and molecular size. All compounds, including Ged and Bim, demonstrated excellent MDCK permeability, indicating efficient transcellular diffusion across renal epithelial cells. PAMPA results showed excellent permeability for 2c, 2f, 3c, 4c, Ged, and Bim, but 3f is rated medium, possibly due to piperazine-induced polarity reducing membrane penetration. Regarding Pgp interactions, all compounds except 2f and 3f are poor Pgp inhibitors, similar to Ged and Bim, reducing the risk of drug–drug interactions, but 2f and 3f are excellent, suggesting potential inhibition that could enhance bioavailability of co-administered drugs. However, 2f and 3f are poor Pgp substrates, indicating efflux susceptibility, which may reduce their absorption compared to 2c, 3c, 4c, and Bim (excellent substrates), while Ged is a poor substrate, potentially limiting its intestinal absorption. All compounds exhibited excellent HIA, F20%, and F30%, reflecting high intestinal absorption and bioavailability at lower doses, consistent with their favorable physicochemical profiles. However, 2c, 2f, 3c, 3f, and Ged show poor F50% bioavailability, indicating reduced absorption at higher doses, possibly due to saturation of transport mechanisms, whereas 4c and Bim achieved excellent F50%, suggesting robust dose-dependent absorption. Overall, 2c, 3c, and 4c demonstrated superior absorption profiles, closely matching Bim and surpassing Ged, particularly in Caco-2 and F50% metrics, though 2f and 3f are limited by poor substrate profiles and Caco-2 permeability, warranting structural optimization to enhance absorption.

2.4.3. Distribution

The distribution potential of five s-triazine derivatives (2c, 2f, 3c, 3f, and 4c) was evaluated against reference drugs Gedatolisib (Ged) and Bimiralisib (Bim) using key pharmacokinetic parameters, including plasma protein binding (PPB), volume of distribution at steady state (VDss), blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration, fraction unbound (Fu), and inhibition of transporters (OATP1B1, OATP1B3, BCRP, MRP1, BSEP). Compounds 2c, 3c, and 4c exhibit high PPB (99.60%, 99.60%, and 99.50%, respectively), rated poor, similar to Bim (94.20%), indicating extensive binding to plasma proteins, which may limit their free fraction available for tissue distribution. In contrast, 2f and 3f show lower PPB (78.00%, 79.50%), rated excellent, suggesting greater availability for tissue penetration, akin to Ged (76.5%). In addition, all compounds demonstrated excellent VDss with the optimal value ranging from 0.04 to 20 L kg−1 (2c: 3.546 L kg−1, 2f: 6.224 L kg−1, 3c: 4.144 L kg−1, 3f: 5.6750 L kg−1, 4c: 3.3880 L kg−1, Ged: 2.6600 L kg−1, Bim: 2.5760 L kg−1), showed wide tissue distribution, likely driven by favorable lipophilicity. For BBB penetration, 2c and Ged exhibited excellent profiles with BBB impermeability, while 2f, 3c, 3f, 4c, and Bim are poor or medium, possibly due to higher polarity or efflux transporter interactions. Fu values reflect PPB trends, with 2f (20.50%) and 3f (16.40%) showing excellent unbound fractions similar to Ged (18.0%), enhancing tissue distribution, compared to poor Fu for 2c (0.30%), 3c (0.30%), 4c (0.40%), and Bim (6.30%). Moreover, all compounds are poor and medium inhibitors of OATP1B1, OATP1B3, BCRP, MRP1, and BSEP, similar to Ged and Bim. Overall, 2f and 3f exhibit superior distribution potential due to lower PPB and higher Fu, closely matching Ged, while 2c, 3c, and 4c are limited by high PPB, akin to Bim, necessitating optimization to enhance free drug availability.

2.4.4. Metabolism

All compounds, including Ged and Bim, are potent CYP1A2 inhibitors, indicating potential drug–drug interactions with CYP1A2-metabolized drugs, such as theophylline. Compounds 2c, 2f, 3c, 3f, and 4c are also CYP1A2 substrates, unlike Ged and Bim, suggesting susceptibility to metabolism via this enzyme, which may lead to variable clearance rates. For CYP2C19, only 3c is an inhibitor of this enzyme, while 2f, 3f, 4c, Ged, and Bim are substrates, implying potential metabolism by CYP2C19, which is potentially affected by genetic polymorphisms. Additionally, CYP2C9 inhibition is prominent in 2c, 3c, 3f, and 4c, with 2f and Bim showing weaker inhibition, and Ged exhibiting none, indicating increased interaction risk for 2c, 3c, 3f, and 4c with CYP2C9-metabolized drugs like warfarin. CYP2D6 inhibition is observed in 2c and 3c, but none are substrates, similar to Ged and Bim, minimizing interactions with CYP2D6-metabolized drugs. Furthermore, CYP3A4, a major drug-metabolizing enzyme, is inhibited by 2f and 3f, and all triazines except 2c are substrates, unlike Ged (weak substrate) and Bim (non-substrate), indicating potential for significant CYP3A4-mediated clearance in 2f, 3f, 3c, and 4c. CYP2B6 inhibition is seen in 2c, 3c, 4c, and Ged, but none are substrates, reducing concerns for this pathway. CYP2C8 inhibition varies, with 2c and 3c showing strong inhibition and 2f showing moderate inhibition, while 3f, 4c, Ged, and Bim are none. HLM stability is excellent for 4c, medium for 2c and 3c, and poor for 2f, 3f, Ged, and Bim, showed that 4c is highly resistant to hepatic metabolism, potentially leading to prolonged systemic exposure, while 2f and 3f's poor stability suggests rapid clearance, akin to Ged and Bim. Overall, 4c exhibits the most favorable metabolic profile with excellent HLM stability and broad CYP substrate activity, surpassing Ged and Bim, while 2f and 3f's poor stability and extensive CYP interactions may limit their metabolic efficiency, necessitating optimization to balance clearance and interaction risks.

2.4.5. Excretion

Compounds 2c (4.52 mL min−1 kg−1), 2f (4.222 mL min−1 kg−1), 3c (4.72 mL min−1 kg−1), 3f (4.293 mL min−1 kg−1) exhibited low CLplasma compared to 4c (5.437 mL min−1 kg−1), Ged (5.329 mL min−1 kg−1) and Bim (5.41 mL min−1 kg−1), which are rated medium due to slightly higher clearance rates that may reflect less favorable metabolic stability. The lower CLplasma values of 2c, 2f, 3c, and 3f suggest a slightly slower clearance compared to 4c, potentially allowing for prolonged systemic exposure, which could be advantageous for sustained therapeutic effects. Regarding T1/2, all compounds are ultra-short half-life drugs (0.5 to < 1 h). Compounds 3c (0.82 h) and Bim (0.926 h) display the longest half-lives, indicating slower elimination and potentially longer duration of action, followed by 4c (0.682 h), 3f (0.65 h), 2c (0.609 h), 2f (0.47 h), and Ged (0.297 h). The shorter T1/2 of Ged suggests rapid elimination, which may necessitate frequent dosing, whereas the s-triazine derivatives, particularly 3c, balance efficient clearance with adequate residence time, aligning closely with Bim's favorable profile.

2.4.6. Toxicity

The toxicity profiles of five s-triazine derivatives were compared with reference drugs Ged and Bim across multiple parameters, including cardiotoxicity (hERG), hepatotoxicity (DILI, human hepatotoxicity), genotoxicity (AMES, carcinogenicity), and organ-specific toxicities. Compounds 2c, 2f, 3c, 3f, and 4c showed medium to poor toxicity parameters including hERG blockers, hERG blockers (10 μm), DILI, FDAMDD, eye irritation, respiratory toxicity, human hepatotoxicity, drug-induced nephrotoxicity, drug-induced neurotoxicity, ototoxicity, genotoxicity, A549 cytotoxicity, and Hek293 cytotoxicity. Rat oral acute toxicity is excellent for 2c, 3c, 4c, and Ged (0.202–0.289), but poor for 2f and 3f (0.720–0.756) and medium for Bim (0.428), suggesting safer acute profiles for pyrrolidine-substituted s-triazines. In addition, skin sensitization is excellent for 4c and Bim (0.275–0.286), medium for 2c and 3c, and poor for 2f and 3f (0.922–0.932), suggesting piperazine groups increase sensitization risk. Carcinogenicity varies, with 2f and 3f (0.149–0.162, excellent) showing low risk, while 2c and 3c are medium, and 4c, Ged, and Bim are poor (0.709–0.955), showing potential long-term safety concerns for 4c. Compound 2c exhibited low or no hepatotoxicity, while the remaining compounds including the reference drug exhibited moderate hematotoxicity. Moreover, bioaccumulation (BCF) and environmental toxicity (IGC50, LC50DM, LC50FM) show comparable values across compounds, with 4c and 3c slightly higher, indicating potential environmental persistence. In particular, all s-triazine compounds showed excellent toxicity parameters including AMES toxicity, eye corrosion, and RPMI-8226 immunotoxicity. Overall, 2c, 3c, and 4c offer safer profiles in AMES, acute toxicity, and immunotoxicity compared to Ged and Bim, but their poor hERG, DILI, and organ-specific toxicities, particularly for 2f and 3f, necessitate structural optimization to mitigate risks.

2.5. Molecular docking

The present study screened s-triazine compounds with potent in vitro anticancer activity against three targets (EGFR – epidermal growth factor receptor, VEGFR2 – vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, and PI3K – phosphoinositide 3-kinase) to determine potential mechanisms of action similar to many other studies.34–38 The binding affinity and bond information (bond type, bond length and amino acid residues) of the chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives with three targets including EGFR, VEGFR2 and PI3K are shown in Table 4. The interactions of the symmetrical chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives with amino acid residues at the active site of anticancer targets are shown in Fig. 4–6.

Table 4. In silico molecular docking results of potent chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives and reference drugsa.

| Entry | Compound | EGFR | VEGFR2 | PI3K | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | Bond type (Å) | AA | BA | Bond type (Å) | AA | BA | Bond type (Å) | AA | ||

| 1 | 2c | −7.4 | 1 π-sulfur (3.52), 11 hydrophobic (3.66–5.48) | LEU844, MET790, LEU718, CYS797, LYS745, LEU788, ALA743, VAL726 | −8.8 | 13 hydrophobic (3.72–5.50) | VAL846, VAL914, LEU838, ALA864, LEU1033, LEU887, VAL897, PHE1045, LYS866 | −8.8 | 1 HB (3.58), 10 hydrophobic (3.60–5.50) | ASP964, ILE963, TYR867, ILE879, ALA885, ILE881, VAL882, MET953, PHE961 |

| 2 | 2f | −7.8 | 2 HB (2.27, 3.48), 4 hydrophobic (3.56–4.84) | GLU762, THR854, LEU718, LEU844, ALA743 | −8.9 | 1 HB (2.10), 8 hydrophobic (4.13–5.45) | CYS917, LYS866, VAL912, VAL914, VAL846, CYS1043, VAL897 | −9.0 | 1 HB (2.78), 8 hydrophobic (3.68–5.16) | ASP836, ILE963, TYR867, ALA885, ILE881, VAL882, MET953 |

| 3 | 3c | −7.6 | 8 Hydrophobic (3.64–5.35) | LEU718, LYS745, LEU788, MET790, LEU844, ALA743 | −9.1 | 2 HB (3.53, 3.38), 16 hydrophobic (3.49–5.48) | LEU838, VAL846, VAL914, ARG840, LYS866, VAL912, LEU887, VAL897, LEU1033, ALA864 | −8.7 | 8 Hydrophobic (3.79–5.38) | ILE963, ILE879, VAL882, MET953, TYR867, ILE831 |

| 4 | 3f | −7.8 | 1 HB (2.85), 6 hydrophobic (3.66–5.17) | GLU762, LEU718, LEU792, LEU844, ALA743 | −8.9 | 1 HB (3.54), 11 hydrophobic (3.89–5.47) | ASP1044, VAL846, VAL914, LEU887, VAL897, VAL912, PHE1045, CYS1043 | −8.8 | 2 HB (2.96, 2.91), 1 electrostatic (4.19), 1 DHB (3.06), 5 hydrophobic (3.59–4.34) | SER806, ASP841, ASP964, LYS807, ILE968 |

| 5 | 4c | −7.7 | 12 Hydrophobic (3.63–5.48) | LEU718, ALA743, LYS745, LEU788, MET790, CYS797, LEU844, MET793, VAL726 | −8.6 | 2 HB (3.60, 3.33), 15 hydrophobic (3.76–5.43) | LEU838, VAL846, VAL914, ARG840, LEU1033, LYS866, LEU887, PHE1045, VAL897, CYS1043 | −8.6 | 7 Hydrophobic (3.65–5.44) | ILE963, ILE879, VAL882, MET953, TYR867, ILE831 |

| 6 | Gefitinib | −7.3 | 1 HB (3.54), 1 π-sulfur (3.56), 8 hydrophobic (3.83–5.48) | ASP855, MET790, LEU718, VAL726, ALA743, LEU844, LYS745 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7 | Pazopanib | — | — | — | −10.0 | 1 HB (3.69), 9 hydrophobic (3.64–5.43) | GLU883, LEU838, LEU1033, LYS866, VAL914, ALA864, VAL846, VAL897, CYS1043 | — | — | — |

| 8 | Bimiralisib | — | — | — | — | — | — | −9.1 | 2 HB (2.05, 3.28), 1 electrostatic (4.15), 11 hydrophobic (3.59–5.47) | VAL882, ASP836, ASP964, ILE879, ILE963, ILE881, ALA885, MET953, PRO810, ILE831, LYS833 |

BA – binding affinity (kcal mol−1), bond type (distance/bond length – Å), AA – amino acid, HB–hydrogen bond (conventional/strong hydrogen bond), CHB – carbon–hydrogen bond, DHB – π-donor hydrogen bond, EGFR – epidermal growth factor receptor, VEGFR2 – vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, PI3K – phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Fig. 4. 2D and 3D representation of the interaction of potent chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives and reference drug Gefitinib with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) target.

Fig. 5. 2D and 3D representation of the interaction of potent chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives and reference drug Pazopanib with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) target.

Fig. 6. 2D and 3D representation of the interaction of potent chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives and reference drug Bimiralisib with phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) target.

The binding affinities of the compounds (2c, 2f, 3c, 3f, and 4c) to EGFR, VEGFR2, and PI3K were evaluated against the reference drugs Gefitinib, Pazopanib, and Bimiralisib, respectively, to assess their inhibitory potential. For EGFR, five compounds exhibited binding affinities ranging from −7.4 to −7.8 kcal mol−1, surpassing Gefitinib's −7.3 kcal mol−1. Compounds 2f and 3f showed the highest affinity at −7.8 kcal mol−1, followed by 4c (−7.7 kcal mol−1), 3c (−7.6 kcal mol−1), and 2c (−7.4 kcal mol−1), indicating a slight but consistent improvement over Gefitinib. For VEGFR2, five compounds showed the binding affinities range from −8.6 to −9.1 kcal mol−1, approaching but not exceeding Pazopanib's −10.0 kcal mol−1. Compound 3c showed the highest affinity (−9.1 kcal mol−1), followed by 2f and 3f (−8.9 kcal mol−1), 2c (−8.8 kcal mol−1), and 4c (−8.6 kcal mol−1), suggesting robust but slightly weaker binding compared to Pazopanib. For PI3K, potent compounds exhibited binding affinities range from −8.6 to −9.0 kcal mol−1, closely matching Bimiralisib's −9.1 kcal mol−1. Compound 2f (−9.0 kcal mol−1) nearly equals Bimiralisib, followed by 2c and 3f (−8.8 kcal mol−1), and 3c and 4c (−8.6 kcal mol−1), indicating high potency across all compounds. These results highlighted 2f and 3c as consistently strong binders across all three targets, closely rivaling the reference drugs.

At the EGFR active site, Gefitinib binds to EGFR with an affinity of −7.3 kcal mol−1, forming one hydrogen bond (HB) with ASP855 (3.54 Å), one π-sulfur interaction with MET790 (3.56 Å), and eight hydrophobic interactions with LEU718, VAL726, ALA743, LEU844, and LYS745 (3.83–5.48 Å). Compound 2c (−7.4 kcal mol−1) mirrored Gefitinib's π-sulfur interaction with MET790 (3.52 Å) and shared hydrophobic interactions with LEU718, ALA743, LEU844, LYS745, and VAL726, supplemented by additional hydrophobic contacts with CYS797 and LEU788, enhancing its binding network. Compound 2f (−7.8 kcal mol−1) formed two HBs with GLU762 (2.27 Å) and THR854 (3.48 Å), which are absent in Gefitinib, and shared hydrophobic interactions with LEU718, LEU844, and ALA743, suggesting a more diverse interaction profile. Compound 3c (−7.6 kcal mol−1) relies on eight hydrophobic interactions, overlapping with Gefitinib at LEU718, LYS745, MET790, LEU844, and ALA743, but lacks polar interactions, potentially limiting its specificity. Compound 3f (−7.8 kcal mol−1) formed one HB with GLU762 (2.85 Å), a unique feature, and shared hydrophobic interactions with LEU718, LEU844, and ALA743. Compound 4c (−7.7 kcal mol−1) formed 12 hydrophobic interactions, including LEU718, ALA743, LYS745, MET790, VAL726, and LEU844, closely resembling Gefitinib's hydrophobic profile but lacking polar interactions. The shared interactions with MET790, LEU718, LEU844, and ALA743 across all compounds indicate a conserved EGFR binding pocket, with 2f and 3f introducing unique polar contacts.

At the VEGFR2 active site, Pazopanib binded to VEGFR2 with an affinity of −10.0 kcal mol−1, forming one HB with GLU883 (3.69 Å) and nine hydrophobic interactions with LEU838, LEU1033, LYS866, VAL914, ALA864, VAL846, VAL897, and CYS1043 (3.64–5.43 Å). Compound 2c (−8.8 kcal mol−1) formed 13 hydrophobic interactions, sharing VAL846, VAL914, LEU838, LEU1033, LYS866, VAL897, and CYS1043 with Pazopanib, but lacks polar interactions, which may explain its lower affinity. Compound 2f (−8.9 kcal mol−1) formed one HB with CYS917 (2.10 Å), absent in Pazopanib, and shared hydrophobic interactions with VAL846, VAL914, LYS866, VAL897, and CYS1043, suggesting a partially conserved binding mode. Compound 3c (−9.1 kcal mol−1) formed two HBs with LEU838 (3.53 Å) and VAL846 (3.38 Å) and 16 hydrophobic interactions, including VAL846, VAL914, LEU838, LYS866, VAL897, LEU1033, and CYS1043, closely resembling Pazopanib's profile while adding polar interactions for enhanced stability. Compound 3f (−8.9 kcal mol−1) formed one HB with ASP1044 (3.54 Å) and 11 hydrophobic interactions, sharing VAL846, VAL914, LEU887, VAL897, and CYS1043 with Pazopanib. Compound 4c (−8.6 kcal mol−1) formed two HBs with LEU838 (3.60 Å) and VAL846 (3.33 Å) and 15 hydrophobic interactions, overlapping with Pazopanib at VAL846, VAL914, LEU838, LEU1033, LYS866, VAL897, and CYS1043. The shared hydrophobic interactions with VAL846, VAL914, LYS866, and VAL897 across all compounds indicate a conserved binding site, with 3c and 4c introducing additional HBs to enhance binding.

At the PI3K active site, Bimiralisib binded to PI3K with an affinity of −9.1 kcal mol−1, forming two HBs with VAL882 (2.05 Å) and ASP836 (3.28 Å), one electrostatic interaction with ASP964 (4.15 Å), and 11 hydrophobic interactions with VAL882, ILE879, ILE963, ILE881, ALA885, MET953, and ILE831 (3.59–5.47 Å). Compound 2c (−8.8 kcal mol−1) formed one HB with ASP964 (3.58 Å) and 10 hydrophobic interactions, sharing VAL882, ILE879, ILE963, ALA885, and MET953 with Bimiralisib, indicating a similar binding mode. Compound 2f (−9.0 kcal mol−1) formed one HB with ASP836 (2.78 Å), mirroring Bimiralisib's interaction, and shared hydrophobic interactions with VAL882, ILE963, ALA885, and MET953, suggesting high similarity. Compound 3c (−8.7 kcal mol−1) showed eight hydrophobic interactions, overlapping with Bimiralisib at VAL882, ILE879, ILE963, MET953, and ILE831, but lacks polar interactions. Compound 3f (−8.8 kcal mol−1) formed two HBs with SER806 (2.96 Å) and ASP841 (2.91 Å), one electrostatic interaction with ASP964 (4.19 Å), one π-donor HB with LYS807 (3.06 Å), and five hydrophobic interactions, sharing ASP964 with Bimiralisib while introducing unique polar contacts. Compound 4c (−8.6 kcal mol−1) formed seven hydrophobic interactions, overlapping with Bimiralisib at VAL882, ILE879, ILE963, MET953, and ILE831, but lacks polar interactions. The shared hydrophobic interactions with VAL882, ILE963, and MET953 across all compounds highlight a conserved PI3K binding pocket, with 2f and 3f closely mimicking Bimiralisib's polar interactions.

In summary, compounds 2f and 3c stand out as the most promising candidates for multi-targeted inhibition of EGFR, VEGFR2, and PI3K, based on their robust binding affinities and interaction profiles, which closely rival or approach those of the reference drugs Gefitinib, Pazopanib, and Bimiralisib. For EGFR, 2f showed the highest affinity (−7.8 kcal mol−1), surpassing Gefitinib (−7.3 kcal mol−1), with unique hydrogen bonds to GLU762 and THR854, alongside hydrophobic interactions with LEU718, LEU844, and ALA743, suggesting enhanced binding specificity. Compound 3c (−7.6 kcal mol−1) also outperformed Gefitinib, sharing key hydrophobic interactions with MET790, LEU718, and LEU844. For VEGFR2, 3c exhibited the highest affinity (−9.1 kcal mol−1), closely approaching Pazopanib (−10.0 kcal mol−1), with two hydrogen bonds (LEU838, VAL846) and an extensive hydrophobic network (VAL846, VAL914, LYS866, VAL897), indicating strong binding stability. Compound 2f (−8.9 kcal mol−1) complemented this with a hydrogen bond to CYS917 and shared hydrophobic interactions, reinforcing its potency. For PI3K, 2f (−9.0 kcal mol−1) nearly matches Bimiralisib (−9.1 kcal mol−1), with a hydrogen bond to ASP836 and hydrophobic interactions with VAL882, ILE963, and MET953, closely mimicking Bimiralisib's profile. Compound 3f (−8.8 kcal mol−1) also showed promise with diverse polar interactions (SER806, ASP841, ASP964, LYS807), though 2f's closer affinity to Bimiralisib gives it an edge. While 2c, 3f, and 4c demonstrated competitive affinities and interactions, 2f and 3c consistently excel across all targets due to their high affinities and balanced polar and hydrophobic interactions, making them prime candidates for further optimization as multi-targeted kinase inhibitors.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study advanced the development of symmetrical chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives as potent anticancer agents, building upon our prior investigation of symmetrical di-substituted phenylamino-s-triazine analogs. By synthesizing 20 compounds via microwave-assisted (MW) and reflux (RF) methods, MW achieved superior yields (88–95%) and markedly reduced reaction times compared to RF (78–86%), echoing the efficiency gains observed in the earlier work where MW similarly outperformed reflux with yields exceeding 90%. Compounds 2c (3-Cl, pyrrrolidine), 2f (3-Cl, piperazine), 3c (3,4-diCl, pyrrrolidine), 3f (3,4-diCl, piperazine), and 4c (2,4-diCl, pyrrrolidine) exhibited significant cytotoxic potential (IC50 < 12 μM) against both MCF7 and C26 cell lines, with 4c (featuring 2,4-dichlorophenyl and pyrrolidine moieties; IC50 = 1.71 μM) surpassing paclitaxel. These results represented a substantial improvement over the previously most active derivatives, which achieved IC50 values below 15 μM against C26 lines but relied on morpholino and mono-substituted halogen or nitro groups. This enhanced potency in the current series underscored the synergistic role of pyrrolidine's lipophilicity and dichlorophenyl's electron-withdrawing effects, as confirmed by QSAR analysis, extending SAR from the previous emphasis on 4-halogeno or 4-nitro substituents and morpholino scaffolds. Pharmacokinetically, 2c, 3c, and 4c demonstrated absorption profiles comparable to Bimiralisib and superior to Gefitinib, with 4c showing exceptional metabolic stability. However, challenges such as high plasma protein binding and potential toxicities (e.g., hERG inhibition and drug-induced liver injury in 2f and 3f) mirror some limitations in the prior compounds, though the current derivatives exhibit lower toxicity on normal cells, akin to the selective profiles of previously phenylamino-s-triazine analogs relative to doxorubicin. Molecular docking further positions 2f and 3c as promising multi-targeted kinase inhibitors, with binding affinities (−7.8 to −9.1 kcal mol−1) rivaling Gefitinib, Pazopanib, and Bimiralisib across EGFR, VEGFR2, and PI3K – expanding the multi-target interactions (including DHFR, CDK2, and mTOR) identified in the earlier docking studies. Overall, these findings highlight the synthetic and therapeutic optimizations in this new series, offering greater potency and drug-like properties than their di-substituted predecessors. Future efforts should prioritize structural refinements to mitigate toxicity, bolster efficacy against various cancer cell lines, and validate mechanisms through kinase inhibition assays and in vivo models, thereby accelerating the translational potential of these s-triazine derivatives toward clinical anticancer applications.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Materials

All reagents and solvents were sourced from reputable commercial suppliers, including Merck and Acros Organics, ensuring high purity and homogeneity. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using pre-coated silica gel aluminum plates (60 GF254, Merck), with visualization achieved under shortwave ultraviolet light at 254 nm. For purification, column chromatography was performed using high-grade silica gel (0.040–0.063 mm, Merck).

Microwave-assisted reactions were performed in a CEM Discover Microwave Synthesizer (USA), equipped with a magnetic stirrer for thorough mixing and an infrared sensor for precise temperature monitoring and control. Melting points were determined using a Sanyo–Gallenkamp apparatus, providing accurate thermal characterization. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance 600/500 spectrometer, with chemical shifts reported in parts per million (δ, ppm) relative to standard references. High-resolution mass spectrometry was performed on an Agilent Series 1100 LC-MS trap system, ensuring accurate molecular weight determination. Finally, the optical density (A) was measured at 570 nm on a MultiskanTM microplate reader in the anti-cancer activity assay.

4.2. Experimental procedures

4.2.1. General procedure for synthesizing mono-substituted s-triazine derivatives (1a–1c)

Cyanuric chloride (7.5 mmol) was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF, 15 mL) and cooled to 0–5 °C. Subsequently, monochloro and dichloro aniline derivatives (5 mmol) and potassium carbonate (K2CO3, 5 mmol) were gradually added to the solution. The reaction mixture was stirred continuously and monitored by TLC until complete consumption of the aromatic amine was observed (typically 30–60 min). Upon completion, THF was evaporated under reduced pressure using a Heidolph rotary evaporator.23 The resulting crude product was purified via recrystallization from a 1 : 1 (v/v) ethanol–water mixture, yielding the desired mono-substituted s-triazine derivatives in excellent yields of 95–97%.

4,6-Dichloro-N-(3-chlorophenyl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (1a)

White solid, yield 97%, mp 144–146 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 11.28 (1H, s, –NH–), 7.73 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.21–7.19 (1H, m, HAr), 7.40 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 7.56–7.55 (1H, m, HAr). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 163.2, 162.7, 142.5, 132.6, 129.8, 120.3, 118.4, 117.2.

4,6-Dichloro-N-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (1b)

White solid, yield 96%, mp 152–154 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 10.87 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.02 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, HAr), 7.47 (1H, dd, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, HAr). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 153.9, 137.7, 131.0, 130.7, 125.7, 122.1, 120.9.

4,6-Dichloro-N-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (1c)

White solid, yield 95%, mp 149–151 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 11.02 (1H, s, –NH–), 7.76 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 7.52 (1H, dd, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, HAr). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 165.2, 152.5, 134.4, 129.8, 128.9, 128.0, 127.7, 127.5.

4.2.2. General procedure for the preparation of chlorophenylamino-s-triazine derivatives (2a–2g, 3a–3g and 4a–4f)

The reflux method

A series of mono-substituted s-triazine derivatives 1a–1c (5 mmol) was synthesized by reacting with a saturated amine (15 mmol) in the presence of potassium carbonate (10 mmol) as a base in 1,4-dioxane (30 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 12–24 h until completion, as monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Upon completion, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure using a Heidolph rotary evaporator to yield a crude solid.23 Purification was achieved either by recrystallization from an ethanol : water mixture (2 : 8, v/v) or by column chromatography on silica gel with a hexane : ethyl acetate eluent system. Reaction yields range from 78 to 86%.

Microwave-assisted synthesis method

A mixture of the mono-substituted s-triazine derivatives 1a–1c (5 mmol), saturated amine (15 mmol), and potassium carbonate (10 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (10 mL) was subjected to microwave irradiation in a synthesizer at a fixed power of 300 W and a temperature of 105 °C. The reaction was monitored by TLC and typically completed within 15–30 min. The 1,4-dioxane was then removed under reduced pressure using a Heidolph rotary evaporator.23 Purification of the crude product was achieved through recrystallization from an ethanol–water mixture (2 : 8, v/v) or column chromatography on silica gel using a hexane–ethyl acetate eluent. Reaction yields range from 88 to 95%.

Purity

All compounds have shown high purity, which was assessed by high-resolution 1H-NMR (500 MHz).

Solubility profile

The synthesized tri-substituted s-triazine derivatives exhibited high solubility in polar solvents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 1,4-dioxane, and methanol. In addition, these compounds exhibited moderate solubility in ethanol and water but limited solubility in nonpolar solvents (e.g., hexane and ethyl acetate).

Stability characteristics

The synthesized compounds showed excellent stability at room temperature. For long-term storage, it is recommended to maintain these compounds at 4–8 °C to preserve their integrity.

N-(3-Chlorophenyl)-4,6-di(piperidin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (2a)

White solid, mp 131–133 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.14 (1H, s, –NH–), 7.99 (1H, t, J = 1.5 Hz, HAr), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 6.5 Hz, HAr), 7.24 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 6.93 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 1.0 Hz, HAr), 3.70 (8H, t, J = 4.5 Hz, –CH2–), 1.61 (4H, d, J = 4.0 Hz, –CH2–), 1.49 (8H, d, J = 3.0 Hz, –CH2–). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.3, 164.0, 142.2, 132.7, 129.8, 120.5, 118.6, 117.4, 43.6, 25.3, 24.3. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C19H26ClN6 373.1902, found 373.1910.

N-(3-Chlorophenyl)-4,6-bis(4-methylpiperidin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (2b)

White solid, mp 164–166 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.16 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.01 (1H, s, HAr), 6.92 (1H, dd, J = 6.5, 1.0 Hz, HAr), 7.23 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 7.53 (1H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 4.60 (4H, d, J = 11 Hz, –CH2–), 2.79 (4H, t, J = 10 Hz, –CH2–), 1.02 (4H, q, J = 10.5 Hz, –CH2–), 1.64–1.58 (6H, m, –CH2– and –CH ), 0.89 (6H, d, J = 5.0 Hz, –CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.3, 164.0, 142.2, 132.7, 129.8, 120.4, 118.6, 117.3, 43.0, 33.6, 30.6, 21.7. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C21H30ClN6 401.2215, found 401.2197.

N-(3-Chlorophenyl)-4,6-di(pyrrolidin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (2c)

White solid, mp 120–122 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.13 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.16 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.66 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 1.5 Hz, HAr), 7.22 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 6.90 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 2.0 Hz, HAr), 3.47 (8H, t, J = 5.5 Hz, –CH2–), 1.87 (8H, s, –CH2–). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 163.4, 163.0, 142.6, 132.7, 129.8, 120.2, 118.5, 117.5, 45.6, 24.8. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C17H22ClN6 345.1549, found 345.1587.

N-(3-Chlorophenyl)-4,6-dimorpholino-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (2d)

White solid, mp 200–201 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.31 (1H, s, –NH–), 7.88 (1H, t, J = 1.5 Hz, HAr), 7.61 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 1.0 Hz, HAr), 7.26 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, HAr), 6.93 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 1.5 Hz, HAr), 3.70 (8H, t, J = 4.5 Hz, –CH2–), 3.62 (8H, d, J = 4.0 Hz, –CH2–). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.6, 163.9, 141.9, 132.7, 129.9, 120.8, 118.8, 117.7, 66.3, 43.3. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C17H22ClN6O2 377.1487, found 377.1489 [M − H]– calcd for C17H20ClN6O2 375.1342; found 375.1324.

N-(3-Chlorophenyl)-4,6-bis(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (2e)

White solid, mp 166–168 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.25 (1H, s, –NH–), 7.91 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, HAr), 6.94 (1H, dd, J = 6.5, 1.0 Hz, HAr), 7.25 (1H, q, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 7.55 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 1.0 Hz,HAr), 3.81–3.70 (8H, m, –CH2–), 2.31 (8H, t, J = 4.0 Hz, –CH2–), 2.18 (6H, s, –CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.3, 164.1, 142.3, 132.7, 129.8, 120.4, 118.6, 117.3, 43.0, 33.6, 30.6. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C19H28ClN8 403.2120, found 403.2131.

N-(3-Chlorophenyl)-4,6-di(piperazin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (2f)

White solid, mp 241–243 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.29 (1H, s, –NH–), 7.94 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, HAr), 7.57 (1H, dd, J = 6.5, 1.0 Hz, HAr), 7.27 (1H, q, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 6.96 (1H, dd, J = 6.5, 1.0 Hz, HAr), 3.85–3.80 (4H, m, –CH2–), 3.68 (4H, t, J = 4.0 Hz, –CH2–), 2.72 (4H, s, –CH2–), 2.51–2.50 (4H, m, –CH2–). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.4, 163.9, 142.0, 132.7, 129.9, 120.7, 118.8, 117.6, 44.2, 42.6. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C17H24ClN8 375.1807, found 375.1811.

N 2-(3-Chlorophenyl)-N4,N4,N6,N6-tetraethyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triamine (2g)

White solid, mp 125–127 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 10.76 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.02 (1H, s, HAr), 7.41–7.36 (2H, m, HAr), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, HAr), 3.93–3.57 (8H, m, –CH2–), 1.27–1.16 (12H, m, –CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 139.5, 133.2, 130.4, 122.9, 119.3, 118.0, 42.0, 13.1. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C17H26N6Cl 349.1902, found 349.1880.

N-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-4,6-di(piperidin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (3a)

White solid, mp 142–144 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.07 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.18 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.58 (1H, dd, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.43 (1H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, HAr), 3.70 (8H, t, J = 4.5 Hz, –CH2–), 1.63 (4H, t, J = 4.5 Hz, –CH2–), 1.51 (8H, d, J = 4.5 Hz, –CH2–). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 165.0, 164.6, 141.5, 131.0, 130.4, 122.8, 121.0, 119.7, 44.3, 25.8, 24.8. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C19H25Cl2N6 407.1512, found 407.1503 [M − H]– calcd for C19H23Cl2N6 405.1367, found 405.1356.

N-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-4,6-bis(4-methylpiperidin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (3b)

White solid, mp 167–169 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.28 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.20 (1H, d, J = 2.5 Hz, HAr), 7.55 (1H, dd, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.45 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, HAr), 4.59 (4H, d, J = 10.5 Hz, –CH2–), 2.81 (4H, t, J = 10 Hz, –CH2–), 1.64–1.58 (6H, m, –CH2– and –CH ), 1.01 (4H, q, J = 10.5 Hz, –CH2–), 0.90 (6H, d, J = 5.5 Hz, –CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.3, 163.9, 140.9, 130.5, 130.0, 122.1, 120.2, 119.0, 43.0, 33.5, 30.6, 21.7. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C21H29Cl2N6 435.1825, found 435.1827.

N-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-4,6-di(pyrrolidin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (3c)

White solid, mp 126–128 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.03 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.35 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.69 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.41 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, HAr), 3.49 (8H, t, J = 5.5 Hz, –CH2–), 1.90 (8H, t, J = 5.5 Hz, –CH2–). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 163.1, 162.8, 141.0, 130.2, 129.5, 121.7, 120.1, 118.7, 45.3, 24.4. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C17H21Cl2N6 379.1199, found 379.1179 [M − H]– calcd for C17H19Cl2N6 377.1054, found 377.1061.

N-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-4,6-dimorpholino-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (3d)

White solid, mp 208–210 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.41 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.06 (1H, d, J = 2.5 Hz, HAr), 7.62 (1H, dd, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.47 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, HAr), 3.70 (8H, t, J = 4.0 Hz, –CH2–), 3.62 (8H, d, J = 4.0 Hz, –CH2–). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.5, 163.8, 140.6, 130.5, 130.2, 122.5, 120.5, 119.3, 66.3, 43.3. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C17H21Cl2N6O2 411.1098, found 411.1095 [M − H]– calcd for C17H18Cl2N6O2 409.0952, found 409.0955.

N-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-4,6-bis(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (3e)

White solid, mp 174–76 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.35 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.10 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.59 (1H, dd, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.48 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, HAr), 3.71 (8H, t, J = 4.0 Hz, –CH2), 2.33 (8H, t, J = 4.0 Hz, –CH2–), 2.20 (6H, s, –CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.6, 164.0, 140.8, 130.7, 130.4, 122.7, 120.6, 119.4, 54.5, 45.4, 42.5. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C19H27Cl2N8 437.1730, found 437.1721.

N-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-4,6-di(piperazin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (3f)

White solid, mp 249–251 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.17 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.14 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.62 (1H, dd, J = 9.0, 2.0 Hz, HAr), 7.46 (1H, d, J = 9.0 Hz, HAr), 3.85–3.81 (4H, m, –CH2–), 3.69–3.64 (4H, m, –CH2–), 2.78–2.69 (4H, m, –CH2–), 2.51–2.49 (4H, m, –CH2–). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 164.5, 164.3, 163.7, 140.4, 130.2, 129.7, 122.3, 120.4, 119.1, 44.1, 42.4. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C17H23Cl2N8 409.1417, found 409.1422.

N 2-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-N4,N4,N6,N6-tetraethyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triamine (3g)

White solid, mp 112–114 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.23 (1H, s, –NH–), 8.44 (1H, d, J = 3.0 Hz, HAr), 7.53 (1H, dd, J = 9.0, 3.0 Hz, HAr), 7.45 (1H, d, J = 9.0 Hz, HAr), 3.54–3.50 (8H, m, –CH2–), 1.14–1.05 (12H, m, –CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 163.9, 163.8, 141.2, 130.5, 130.0, 122.0, 120.1, 118.8, 40.8, 13.4. LC-MS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for C17H25N6Cl2 383.1512, found 383.1490.

N-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-4,6-di(piperidin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine (4a)