Abstract

Objective

To present visual acuity findings and related outcomes from eyes of patients enrolled in a randomized trial conducted by the Submacular Surgery Trials (SST) Research Group (SST Group H Trial) to compare surgical removal vs observation of subfoveal choroidal neovascular lesions that were either idiopathic or associated with ocular histoplasmosis.

Methods

Eligible patients 18 years or older had subfoveal choroidal neovascularization (new or recurrent) that included a classic component on fluorescein angiography and best-corrected visual acuity of 20/50 to 20/800 in 1 eye (“study eye”). Patients were examined 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after enrollment to assess study outcomes and adverse events. Best-corrected visual acuity was measured by a masked examiner at the 24-month examination. A successful outcome was defined a priori as 24-month visual acuity better or no more than 1 line (7 letters) worse than at baseline.

Results

Among 225 patients enrolled (median visual acuity 20/100), 113 study eyes were assigned to observation and 112 to surgery. Forty-six percent of the eyes in the observation arm and 55% in the surgery arm had a successful outcome (success ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 0.89–1.56). Median visual acuity at the 24-month examination was 20/250 among eyes in the observation arm and 20/160 for eyes in the surgery arm. The prespecified subgroup of eyes with visual acuity worse than 20/100 at baseline (n=92) had more successes with surgery; 31 (76%) of 41 eyes in the surgery arm vs 20 (50%) of 40 eyes in the observation arm examined at 24 months (success ratio, 1.53; 95% confidence interval, 1.08–2.16). Five (4%) of 111 eyes in the surgery arm subsequently had a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Twenty-seven (24%) of 112 initially phakic eyes in the surgery arm (none in the observation arm) had cataract surgery during follow-up, all among patients older than 50 years. Recurrent choroidal neovascularization developed by the 24-month examination in 58% of surgically treated eyes.

Conclusions

Overall, findings supported no benefit or a smaller benefit to surgery than the trial was designed to detect. Findings support consideration of surgery for eyes with subfoveal choroidal neovascularization and best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/100 that meet other eligibility criteria for the SST Group H Trial. Other factors that may influence the treatment decision include the risks of retinal detachment, cataract among older patients, and recurrent choroidal neovascularization and the possibility that additional treatment will be required after submacular surgery.

Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) particularly when it develops in a subfoveal location, often has a devastating effect on visual acuity and other aspects of vision in the affected eye. In the United States, CNV is diagnosed most often in eyes with age-related macular degeneration, the ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, or in the absence of any apparent underlying condition (idiopathic CNV). Neovascular ocular histoplasmosis and idiopathic CNV typically develop in individuals who are in their 30s, 40s, or 50s,1 often critical periods in their working lives. Unlike age-related macular degeneration in which CNV frequently develops in the second eye within a few years of onset in the first eye,2,3 neovascular ocular histoplasmosis4,5 and idiopathic CNV often remain unilateral. Nevertheless, the effect of this condition on health- and vision-targeted quality of life has been documented to be substantial.6

Neovascular age-related macular degeneration and idiopathic CNV are diagnosed by ophthalmologists throughout the developed regions of the world, but neovascular ocular histoplasmosis rarely is diagnosed outside North America. In the United States, exposure to Histoplasma capsulatum, which is believed to be the initiating event,7–9 occurs primarily in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys and surrounding areas.10 Although predisposing ocular lesions (“histo spots”) develop in only a small percentage of individuals following infection,11 there is no known method of preventing either the predisposing lesions or CNV that may develop decades after the initial infection. Despite the proven benefit of laser photocoagulation of extrafoveal and juxtafoveal CNV,12–18 many patients are seen initially with subfoveal CNV19 or have subfoveal recurrence following laser photocoagulation.20,21

Since 1997, the Submacular Surgery Trials (SST) Research Group has been conducting randomized trials of surgical removal of subfoveal choroidal neovascular lesions to evaluate the role of this procedure in the treatment of patients with age-related macular degeneration, ocular histoplasmosis, and idiopathic CNV. Patients were enrolled in a pilot study from November 23, 1993, through March 31, 1997. The goal of the pilot study was to refine the design and methods to be employed in a formal evaluation of submacular surgery.22 The first randomized clinical trial initiated by the SST Research Group was for patients who had either new or recurrent subfoveal CNV that was idiopathic or associated with the ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (SST Group H Trial). This group of patients was judged to be the one in which submacular surgery held the most promise of providing a benefit with respect to future vision, based on reports from uncontrolled case series.23–25 Moreover, no other treatment had been documented to benefit these patients. Although the benefits of laser photocoagulation for treating extrafoveal and juxtafoveal CNV arising from the same conditions were demonstrated by the Macular Photocoagulation Study Group,12–18 investigators who participated in a small pilot study reported that there was no benefit to laser photocoagulation of subfoveal CNV secondary to ocular histoplasmosis.19 More recently, photodynamic therapy with verteporfin has been suggested to be beneficial for treating subfoveal CNV due to ocular histoplasmosis26 and subfoveal idiopathic CNV,27 but that conclusion is based on small uncontrolled case series.

To our knowledge, the SST Group H Trial is the first randomized comparison of any treatment for subfoveal CNV in eyes with ocular histoplasmosis or similar idiopathic lesions to the natural history of such lesions in a sufficient number of patients followed up for a sufficiently long period to provide statistically meaningful data. The purpose of this report is to present visual acuity and related ophthalmic findings from the clinical trial; a separate report in this issue of the ARCHIVES28 presents findings regarding vision-targeted and general health-related quality of life. The findings from other trials conducted by the SST Research Group for patients with subfoveal CNV secondary to age-related macular degeneration also are reported elsewhere.29–32

METHODS

The members of an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee, appointed in 1996 by the Director of the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, Md, reviewed findings from the pilot study for similar patients and approved the design and methods of the SST Group H Trial in January 1997 before enrollment of patients was initiated. In addition, institutional review boards at all participating institutions reviewed and approved the study design and the consent forms to be used locally. All patients gave signed consent before enrollment and random treatment assignment.

The SST Manual of Procedures33 and the SST Forms Book34 provide detailed information regarding study design, methods, and policies. Only those aspects pertinent to this report are summarized here.

PATIENT ELIGIBILITY AND ENROLLMENT

Eligible patients were identified from referrals to 21 clinical centers that participated in the SST Group H Trial, including 14 clinical centers that also participated in the SST pilot study. Participating ophthalmologists and other personnel at each center were required to meet standard criteria to be SST certified to enroll, treat, examine, and follow up study patients.

After a diagnosis of subfoveal CNV had been made by the study ophthalmologist, best-corrected visual acuity was measured following a standard protocol with modified Bailey-Lovie charts (ET-DRS [Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study] charts),35 contrast threshold was measured using Pelli-Robson charts at 0.5 m,36,37 and reading speed with enlarged text was measured using charts and methods developed for the Macular Photocoagulation Study.38 For each measurement, the 2 eyes were tested separately; a different chart was used to test each eye. Stereoscopic color photographs of the disc and macula of each eye and a stereoscopic film-based fluorescein angiogram were taken by an SST-certified photographer, who followed a standard protocol, to document eligibility and baseline status for comparison with photographs taken during follow-up examinations. Usage of aspirin and anticoagulants and a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and, beginning in February 1999, other major medical conditions were elicited from the patient as part of baseline data collection.

To be eligible for enrollment and random treatment assignment in the trial, the patient had to have a subfoveal neovascular lesion that included classic CNV. The lesion could be either new CNV (no prior treatment of CNV) or recurrent subfoveal CNV following earlier laser photocoagulation for extrafoveal or juxtafoveal CNV as long as CNV was the subfoveal component of the lesion. Earlier treatment of the macula of the study eye with photodynamic therapy rendered the patient ineligible. The total area occupied by the lesion, including any earlier contiguous laser photocoagulation, could not exceed 9.0 disc areas (DA) (approximately 22.9 mm2 on the retina). Eligible eyes had best-corrected visual acuity scores of 82 to 18 inclusive, corresponding to Snellen fractions of 20/50 to 20/800 (5/200); visual acuity of the nonstudy eye had to be light perception or better. Patients who had evidence of age-related macular degeneration or other progressive ocular disease in either eye that could affect visual acuity or assessment of other ophthalmic outcomes were ineligible. Only 1 eye of each patient (study eye) was eligible for enrollment. Whenever both eyes of a patient were eligible, the study eye was selected by the patient and ophthalmologist prior to enrollment; the fellow eye was managed as they decided.

Patients judged to be eligible by an SST-certified ophthalmologist were given information about the clinical trial and invited to participate. For those who agreed, a study identification number and an alphabetic code were assigned before they completed an interview by telephone with personnel at the SST Coordinating Center, Baltimore, Md.6 After the patient signed the consent form for the trial, the identification number and alphabetic code were recorded on the baseline data forms that were telecopied to the coordinating center for preliminary review of eligibility and completeness of baseline data recording. The next treatment arm assignment was selected automatically from the electronic file of random assignments that had been prepared for that clinical center specifically for the SST Group H Trial. The clinical center staff were notified immediately of the assigned treatment, surgery or observation, by means of an automated message returned to them by telecopier. The assignment was communicated to the patient by the enrolling ophthalmologist; surgery was scheduled as soon as possible within the next 8 days for each patient assigned to that treatment arm.

EVALUATION OF BASELINE PHOTOGRAPHS

After enrollment, baseline photographs were sent to the SST Photograph Reading Center, Baltimore, for review by trained readers who were masked to the treatment arm to which the study eye had been assigned. The focus of the review was on eligibility for enrollment and documentation of characteristics of the eye and lesion. Lesion characteristics were described by applying standard definitions39 adapted from other clinical trials.40,41 The underlying cause of the neovascular lesion in the study eye was assigned based on the appearance of both eyes and the presence of other lesions in the 2 eyes. The size of the subfoveal lesion was categorized using a transparent overlay, adapted from one used in the Macular Photocoagulation Study,40 that had printed circles with areas equivalent to 2.0, 3.5, 6.0, 9.0, 12.0, and 16.0 DA. The areas of the circles on the retina were 5.1 to 40.6 mm2, assuming a retinal image magnification factor of 2.5.39,41 A final judgment regarding eligibility was made after review of baseline photographs and evaluation of pertinent baseline data had been completed.

MEASUREMENT AND SCORING OF VISUAL ACUITY

At baseline and each follow-up examination, visual acuity was measured by an SST-certified vision examiner. Each eye was tested separately after an SST protocol refraction to obtain the best correction. Testing began at 2 m; whenever the patient could read 15 letters or more correctly using the eye, the visual acuity score was recorded as the number of letters read correctly plus 30. When the patient could not read at least 15 letters at 2 m with the eye being tested, visual acuity was measured at 0.5 m after the refractive correction was adjusted for the closer distance. In the latter situation, the visual acuity score was calculated to be the sum of the number of letters read correctly at 2 m and the smaller of 30 or the number of letters read correctly at 0.5 m. Visual acuities from 20/20 to 20/1600 (5/400), inclusive, could be measured using these 2 test distances. Eyes with which patients could not read any letters correctly at either test distance (visual acuity <5/400) were tested for light perception with confirmation by the ophthalmologist.

A traveling vision examiner based at the SST Chairman’s Office, Baltimore, refracted both eyes and measured best-corrected visual acuity, contrast threshold, and reading speed of patients in both treatment arms at the 24-month examination, designated the primary outcome assessment examination, and at the 48-month examination for patients enrolled by September 1999. Beginning in June 2002, a traveling vision examiner also conducted masked measurements of vision at 36-month examinations whenever possible for patients enrolled by June 1999 who had not completed that examination earlier. Traveling vision examiners were masked to the clinical trial in which the patient was enrolled, the study eye, and the treatment assigned or received.

TREATMENT, FOLLOW-UP EXAMINATIONS, AND ADVERSE EVENTS

Only surgeons who met defined conditions based on training and experience were approved to perform submacular surgery on study eyes of SST patients.33 Whenever surgery could not be scheduled within 8 days after enrollment, a fluorescein angiogram taken no more than 8 days before surgery was required to document the preoperative status of the eye and lesion.

The surgery protocol specified a standard 3-port pars plana vitrectomy and surgical separation of the posterior hyaloid from the macular region when not already detached preoperatively. The retinotomy site was chosen by the surgeon to provide optimal access to the neovascular lesion and to minimize surgical trauma to the fovea. Surgeons had the option of infusing balanced saline solution to separate the neurosensory retina from the neovascular lesion. Fibrovascular tissue was removed manually with a micro forceps; intraocular pressure was elevated immediately prior to removal of the tissue to minimize hemorrhage from the choroid and was returned slowly to normal pressure after removal of tissue from beneath the retina but before its removal from the eye. The peripheral retina was examined for tears prior to fluid-air exchange. A complete fluid-air exchange was performed; fluid was reinstilled to create an air bubble of up to 50% in phakic eyes or up to 100% in pseudophakic eyes. Patients were instructed to remain in a face-down position overnight after surgery and until the air bubble was 20% or less. Details of the surgery, deviations from the surgical protocol, and intraoperative complications were recorded by the surgeon on a standard form.34

Eyes treated surgically were examined as often as judged necessary by the surgeon during the postoperative period. Patients were scheduled for a postsurgical examination and data collection at 1 month after enrollment. Patients assigned to observation were scheduled for a telephone review of ocular status and history 1 month after enrollment.

All patients were scheduled for follow-up examinations for data collection purposes at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after enrollment. Patients who enrolled by September 30, 2000, were scheduled for a 36-month examination; those who enrolled by September 30, 1999, also were scheduled for a 48-month examination. In addition to the examinations prescribed by the study protocol, patients were seen by SST ophthalmologists as often as necessary to evaluate symptoms and the need for treatment of the study eye or fellow eye. For patients not examined at the midpoint between scheduled SST examinations, interim ophthalmic and medical histories were collected by telephone by local SST clinical personnel. The last study examinations for all patients who had not completed a 48-month examination already were performed during the final year of patient follow-up that began on October 1, 2002.

At the 3-month and later examinations, best-corrected visual acuity, contrast threshold, and reading speed were measured. A detailed history of systemic and ocular complications and intervening treatments to the study eye was elicited. Color photography and fluorescein angiography were repeated; photographs were sent to the SST Photograph Reading Center for interpretation and coding. The emphasis of central review of photographs taken during follow-up was on identification of CNV and its location in eyes following surgery, measurement of the current size of the subfoveal lesion, and documentation of retinal complications. Eyes in the surgery arm were considered for additional treatment whenever dye leakage from CNV was observed by the ophthalmologist on the fluorescein angiogram. The re-treatment protocol specified laser photocoagulation or surgery depending on the location of the CNV; however, no more than 1 repeat surgery was recommended. Regardless of the assigned treatment arm, the status of the study eye, or the vision of the fellow eye, the study protocol recommended that cataract surgery be considered whenever the ophthalmologist judged that the severity and location of any lenticular opacity was sufficient to cause a loss of at least 2 lines of visual acuity in an otherwise healthy phakic eye.

Prespecified adverse events were reported by ophthalmologists on the basis of findings at scheduled study examinations; additional adverse events were reported as clinical center personnel became aware of them. An Adverse Event Review Committee, appointed by the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee, classified events and requested additional information when needed to judge whether the event was in any way related to surgery in the study eye or participation in the clinical trial.

STATISTICAL DESIGN AND STUDY MONITORING

The SST Planning Committee defined the primary successful outcome of interest a priori to be improvement or stabilization of visual acuity at the 24-month examination, with stabilization defined as a visual acuity no more than 7 letters better or worse than at baseline. Examinations at 36 months and 48 months after enrollment were intended to monitor whether any treatment effect observed at the 24-month examination persisted. Sample size was calculated during the planning phase under the assumption that 50% of eyes assigned to observation would have a successful outcome, based on unpublished data from cases assigned to the observation arm in the SST Group H pilot trial and untreated eyes of patients who participated in a pilot trial of laser photocoagulation in similar eyes.19 The minimum clinically meaningful relative improvement in success rate after surgery, considering the cost and inconvenience of surgery, was judged by the members of the Planning Committee to be 50%, that is, a successful outcome in 75% or more of surgically treated eyes. Available data from 12-month examinations of eyes randomly assigned to surgery or observation in the SST Group H pilot trial and followed through October 31, 1996, suggested that a treatment effect of this magnitude was realistic. Type I (α) and type II (β) errors were set at .01 (2-sided) and .10, respectively, to minimize the chance of reaching an incorrect conclusion regarding the effectiveness of surgery during interim monitoring of outcome data. Allowances for deaths and missed 24-month examinations yielded a target sample size of 240 patients (240 eyes).

Responsibility for monitoring accumulating data regarding safety and effectiveness of surgery was entrusted to the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee appointed in 1996. Informal statistical monitoring guidelines of the Lan and DeMets type42 were developed for review at the meeting of the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee on August 25, 1997; these were based on the assumption that there would be 5 interim analyses of the data on which a recommendation would be made to continue or to halt accrual. Reviews of accumulating data by the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee emphasized comparison of distributions of visual acuity and changes from baseline to each examination by treatment arm as well as proportions of eyes in each arm with successful outcomes at the 24-month examination, the primary outcome defined in the design.

The Data and Safety Monitoring Committee met in person approximately every 12 months. At the beginning of these meetings, the chair of the Adverse Event Review Committee reported findings from the most recent interim review of potential adverse events to the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee. At their meeting on August 22, 2001, with 217 patients enrolled in the SST Group H Trial, the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee recommended that accrual halt on September 30, 2001, and that the last patients enrolled be followed up for only 3 years. The rationale for the recommendation was the longer than expected period of patient accrual, the slow rate of accrual during the previous 12 months, and stochastic curtailment analyses that indicated that there should be little loss of power with the achieved sample size. Subsequently, owing to funding constraints, the follow-up phase of the trial was curtailed further so that a minimum of 2 years of follow-up was provided for each patient. On February 20, 2004, the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee reviewed findings summarized from the final SST Group H Trial database and recommendations regarding submacular surgery.

DATA ANALYSIS AND STATISTICAL METHODS

Data from masked vision examinations by traveling vision examiners were used in analyses whenever available; otherwise, measurements by local examiners were analyzed. For analysis of change in visual acuity, eyes with visual acuity worse than 20/1600 (<5/400) but with at least light perception were coded as having visual acuity 3 lines (15 letters) worse than 20/1600, that is, equivalent to 3 lines worse than the smallest line measurable at 0.5 m. Visual acuity scores were used in all analyses. Scores were converted to equivalent Snellen fractions for presentation in tables and text.

The χ2 test was used to compare the proportions of eyes with successful outcomes at the 24-month examination, as defined earlier, and to compare categorical distributions of size and changes in size of subfoveal lesions (test for trend). Distributions of visual acuity, changes in visual acuity from baseline to follow-up examinations, and other continuous measurements were compared between treatment arms using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.43 Proportions of eyes in which visual acuity had improved or stabilized and the proportion of eyes with fluorescein leakage from CNV at each examination were calculated using a 2-state stochastic model that considers both events and recoveries and compares treatment arms using χ2 tests.44 Time to first observation of recurrent CNV in the surgery arm and time to cataract surgery and first report of visually significant cataract were analyzed using the product-limit method.45 Eyes were withdrawn from analysis after the last completed examination when either of these 2 methods was used. Confidence intervals (CIs) on “success ratios” (inverse of risk ratios) for surgery vs observation were calculated using the method of Katz et al.46

Subgroups of study eyes defined by prespecified baseline characteristics of patients, eyes, and lesions were examined for consistency of visual acuity findings by treatment arm. Characteristics to be evaluated were selected primarily from those identified in earlier clinical trials of laser photocoagulation for subfoveal CNV.38,47 Of particular interest were subgroups defined by baseline visual acuity because of findings from retrospective analysis of postsurgery visual acuity outcomes in case series and from prospective data for similar patients who participated in the pilot study that eyes with better visual acuity at baseline sustained large losses after surgery (B.S.H. and N.M.B., unpublished data, February 24, 1996). Interactions between surgery and baseline covariates suggested by subgroup analyses were evaluated using interaction terms in logistic regression models with a successful outcome, as defined earlier, at the 24-month examination as the dependent variable.

All pertinent data received at the SST Coordinating Center by October 31, 2003, were analyzed. Data from each patient were analyzed with the treatment arm to which he or she was assigned randomly at time of enrollment (“intent-to-treat” analysis approach). SAS (SAS Inc, Cary, NC) and custom-written software were used for data analyses. P values were not adjusted for multiplicity of outcomes or comparisons. Although P values suggestive of a difference between treatment arms (P≤.05 for overall findings and P≤.10 for prespecified subgroups) have been noted in this report, only P≤.01 was deemed statistically significant for overall findings, as specified in the design.

RESULTS

From April 1, 1997, until accrual ended on September 30, 2001, two hundred twenty-five patients (225 eyes) enrolled in the SST Group H Trial; 112 patients were assigned to the surgery arm and 113 patients to the observation arm. Based on central review of baseline photographs, 27 eyes, 17 (15%) in the surgery arm and 10 (9%) in the observation arm, were judged not to meet the strict criteria for eligibility. In 14 eyes (10 in the surgery arm and 4 in the observation arm), CNV was judged to be in a juxtafoveal rather than subfoveal location; 2 of these eyes, both in the surgery arm, also were judged to be ineligible for other reasons. Other reasons for judging eyes to be ineligible were evidence of some other cause of CNV (6 eyes, 3 in each arm; 2 eyes with another reason also), no classic CNV (5 eyes, 1 with another reason also), total size of the subfoveal lesion greater than 9.0 DA (1 eye in each arm), and photographic quality inadequate to judge eligibility (1 eye). In addition, 1 eye in the observation arm that also was ineligible for other reasons had baseline visual acuity worse than the Snellen equivalent of 20/800 (5/200). Data for ineligible patients were analyzed with all other patients in the treatment arm to which they were assigned.

CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS AND EYES AT STUDY ENROLLMENT

Characteristics of patients, eyes, and subfoveal lesions at the time of enrollment are summarized by treatment arm in Table 1 and Table 2. Treatment arms were well balanced on all characteristics recorded. The median age of patients was 48 years; 57 patients (25%) were 60 years or older. Almost all patients (96%) classified their race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic white, consistent with epidemiological data and patient populations enrolled in other clinical trials of treatment for idiopathic CNV and neovascular ocular histoplasmosis.12–15 As a group, the remaining patients were distributed equally between the treatment arms; however, 4 of 5 non-Hispanic black enrollees were assigned to the surgery arm. Seven of 13 patients who reported that they were unable to work attributed this inability to poor vision. Information about other medical conditions at baseline has been published.6

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Patients at the Time of Enrollment in the SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Patients by Treatment Arm |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Observation (n = 113) | Surgery (n = 112) |

| Age, y | ||

| <30 | 10 (9) | 11 (10) |

| 30–39 | 20 (18) | 22 (20) |

| 40–49 | 32 (28) | 25 (22) |

| 50–59 | 22 (19) | 26 (23) |

| 60–69 | 17 (15) | 18 (16) |

| ≤70 | 12 (11) | 10 (9) |

| Gender | ||

| Women | 57 (50) | 67 (60) |

| Men | 56 (50) | 45 (40) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, not Hispanic | 109 (96) | 108 (96) |

| Black, not Hispanic | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Hispanic | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Employed | 74 (65) | 73 (65) |

| Retired | 24 (21) | 21 (19) |

| House spouse | 6 (5) | 6 (5) |

| Unemployed | 3 (3) | 4 (4) |

| Disabled | 5 (5) | 8 (7) |

| Student | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Smoking history | ||

| Never smoked | 36 (32) | 42 (38) |

| Former smoker | 29 (26) | 33 (29) |

| Current smoker | 48 (42) | 37 (33) |

| Medical history, self-reported | ||

| Hypertension | 30 (27) | 28 (25) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (4) | 7 (6) |

| Other known condition* | 39 (62) | 39 (64) |

Abbreviation: SST, Submacular Surgery Trials.

Based on self-reports of 63 patients in the observation arm and 61 patients in the surgery arm.

Table 2.

Status of Study Eyes at the Time of Patient Enrollment, SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Patients by Treatment Arm |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Observation (n = 113) | Surgery (n = 112) |

| Probable cause of neovascular lesion | ||

| Ocular histoplasmosis | 97 (86) | 95 (85) |

| Idiopathic | 13 (12) | 14 (12) |

| Other | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Visual acuity, Snellen equivalent | ||

| 20/50–20/80 | 53 (47) | 49 (44) |

| 20/100–20/160 | 32 (28) | 34 (30) |

| 20/200–20/320 | 20 (18) | 22 (20) |

| 20/400–20/640 | 6 (5) | 6 (5) |

| ≤20/800 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Contrast threshold, % contrast required | ||

| ≤1.6 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| >1.6–3.2 | 39 (35) | 42 (38) |

| >3.2–6.3 | 47 (42) | 41 (37) |

| >6.3–12.6 | 17 (15) | 17 (15) |

| >12.6 | 10 (9) | 11 (10) |

| Reading speed with enlarged text, wpm* | ||

| ≥120 | 10 (9) | 14 (13) |

| 100–119 | 9 (8) | 12 (11) |

| 80–99 | 15 (14) | 13 (12) |

| 60–79 | 25 (23) | 19 (17) |

| 40–59 | 22 (20) | 17 (16) |

| 20–39 | 12 (11) | 21 (19) |

| 0–19 | 16 (15) | 13 (12) |

| Total size of subfoveal lesion, DA† | ||

| ≤2.0 | 49 (43) | 57 (51) |

| >2-≤3.5 | 26 (23) | 22 (20) |

| >3.5-≤6.0 | 29 (26) | 22 (20) |

| >6.0-≤9.0 | 6 (5) | 10 (9) |

| >9.0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Indeterminate | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Occult CNV present | ||

| Yes | 38 (34) | 38 (34) |

| Questionable | 4 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Previous laser photocoagulation | 39 (35) | 25 (22) |

| Study eye aphakic or pseudophakic | 5 (4) | 0 |

Abbreviations: CNV, choroidal neovascularization; DA, disc areas; SST, Submacular Surgery Trials; wpm, words per minute.

Reading speed measured for 109 study eyes in each treatment arm.

Median visual acuity score of study eyes at baseline was 66 letters (20/100 Snellen equivalent). Median reading speed with the study eye alone was 66 words per minute; median contrast threshold was 4.5%. The lesions in study eyes were judged centrally to be due to ocular histoplasmosis for 192 patients (85%); 64 study eyes (28%) had subfoveal CNV that had recurred after laser photocoagulation. Almost half the subfoveal neovascular lesions in the study eyes were 2.0 DA (5.1 mm2) or smaller in size; only 20 eyes (9%) had subfoveal lesions larger than 6.0 DA (15.3 mm2). Median visual acuity score of fellow eyes at baseline was 100 (20/20 Snellen equivalent). Fifty-six (29%) of the 192 patients with neovascular ocular histoplasmosis lesions also had a neovascular lesion in the fellow eye; 102 fellow eyes (53%) had other lesions of ocular histoplasmosis but not a neovascular lesion. Two (6%) of the 27 patients with idiopathic CNV in the study eye had a neovascular lesion in the fellow eye.

SURGERY PROTOCOL DEVIATIONS AND INTRAOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

No patient assigned to the observation arm had submacular surgery in the study eye during the follow-up period. Of 112 patients assigned to surgery, 1 patient refused surgery after enrollment. Two other patients had surgery 9 days after enrollment and one 17 days later. In 9 phakic eyes, the air fill at the end of surgery was greater than 50%; gas (not air) fill was used in 10 eyes.

In 14 eyes, a small peripheral retinal tear was noted during surgery; 12 eyes with peripheral tears were treated with cryotherapy or laser photocoagulation. Two retinal tears in the posterior pole were reported, 1 each in foveal and extrafoveal locations. In 75 eyes (68%) some blood remained after surgery; however, in only 13 eyes was the area occupied by the residual blood as large as 1 DA as judged by the surgeon.

COMPLETION OF SCHEDULED EXAMINATIONS

Four patients in the observation arm died after enrollment; 2 deaths occurred before the 24-month examination. One patient in the surgery arm died nearly 4 years after enrollment. The number of patients expected to be examined at each scheduled time after enrollment, based on date of enrollment and vital status, is given in Table 3. Of 225 patients who enrolled, 194 (86%) were eligible for a 36-month examination; 122 patients (54%) were eligible for a 48-month examination. Of 608 examinations scheduled for patients in the surgery arm at 3 months or longer after enrollment, 570 (94%) were completed; more than 90% of the patients in the surgery arm were examined at each scheduled time. Patients in the observation arm returned for 527 (87%) of 606 scheduled examinations. Follow-up examination rates were consistently lower in the observation arm than in the surgery arm at all scheduled times. Five of 13 patients in the observation arm and 4 of 9 patients in the surgery arm who were not examined 24 months after enrollment had either a 36- or a 48-month examination.

Table 3.

Number and Percentage of Patients Examined at Each Scheduled Time in the SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Patients by Treatment Arm |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Observation (n = 113) |

Surgery (n = 112) |

|||

| Time Since Study Enrollment, mo | Expected* | Examined | Expected* | Examined |

| 0 | 113 | 113 (100) | 112 | 112 (100) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 109 (97) |

| 3 | 113 | 99 (88) | 112 | 107 (96) |

| 6 | 113 | 99 (88) | 112 | 105 (94) |

| 12 | 113 | 103 (91) | 112 | 106 (95) |

| 24 | 111 | 98 (88) | 112 | 103 (92) |

| 36 | 97 | 78 (80) | 97 | 90 (93) |

| 48 | 59 | 50 (85) | 63 | 59 (94) |

Abbreviation: SST, Submacular Surgery Trials.

Expected number is based on the date of enrollment and vital status.

In presentation of clinical outcomes below, findings through the 24-month examination have been emphasized as all patients were eligible for these examinations (except for the 2 patients who died earlier in follow-up) and because the primary outcome was defined based on the 24-month examination. Findings are presented from other examinations to permit assessment of consistency of 24-month outcomes with those at other time points. Cross-sectional findings have been presented for each examination through 36 months because most patients (86%) were eligible for a 36-month examination. Longitudinal data displays include 48-month data for patients examined at that time.

VISUAL ACUITY AND CHANGES IN VISUAL ACUITY

The distributions of study eyes by visual acuity at the 3-month through the 36-month examinations are summarized in Table 4 for comparison with the baseline distributions in Table 2. Of 200 study eyes with visual acuity measured and reported at the 24-month examination, 181 (90%) had the measurement made by a masked traveling vision examiner. Median visual acuity of eyes at the 24-month examination was 20/250 in the observation arm (interquartile range, 20/80–20/320) and 20/160 in the surgery arm (interquartile range, 20/64–20/320). The 24-month distributions of visual acuity did not differ between treatment arms to a statistically significant degree (P=.07, Wilcoxon rank sum test). The largest difference between distributions of visual acuity by treatment arm at any follow-up examination was observed at the 12-month examination (P=.04, Wilcoxon rank sum test) in favor of surgery.

Table 4.

Distribution of Patients by Visual Acuity (VA) of the Study Eye When Examined at Specified Times After Enrollment, SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Study Eyes by Time After Enrollment by Treatment Arm |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 mo |

6 mo |

12 mo |

24 mo |

36 mo |

||||||

| VA (Snellen Equivalent) | Observation (n = 99) | Surgery (n = 107) | Observation (n = 99) | Surgery (n = 105) | Observation (n = 103) | Surgery (n = 106) | Observation (n = 97*) | Surgery (n = 103†) | Observation (n = 78) | Surgery (n = 90) |

| ≥20/40 | 12 (12) | 18 (17) | 11 (11) | 13 (12) | 8 (8) | 16 (15) | 10 (10) | 16 (16) | 10 (13) | 16 (18) |

| 20/50–20/80 | 28 (28) | 34 (32) | 26 (26) | 30 (29) | 23 (22) | 24 (23) | 15 (15) | 15 (15) | 10 (13) | 12 (13) |

| 20/100–20/160 | 29 (29) | 24 (22) | 23 (23) | 29 (28) | 21 (20) | 22 (21) | 15 (15) | 21 (20) | 13 (17) | 21 (23) |

| 20/200–20/320 | 18 (18) | 20 (19) | 25 (25) | 24 (23) | 27 (26) | 30 (28) | 31 (32) | 35 (34) | 24 (31) | 24 (27) |

| 20/400–20/640 | 9 (9) | 6 (6) | 9 (9) | 5 (5) | 11 (11) | 4 (4) | 13 (13) | 11 (11) | 11 (14) | 8 (9) |

| 20/800–20/1280 | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 10 (10) | 6 (6) | 9 (9) | 4 (4) | 6 (8) | 3 (3) |

| ≤20/1600 | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | 6 (7) |

| Median VA, Snellen equivalent | 20/125 | 20/100 | 20/125 | 20/100 | 20/160 | 20/125 | 20/250 | 20/160 | 20/200 | 20/160 |

Abbreviation: SST, Submacular Surgery Trials.

Measurements of VA were made by masked examiners for 87 eyes (90%).

Measurements of VA were made by masked examiners for 94 eyes (91%).

By the 12-month examination, the visual acuity of the study eye of 1 patient in each treatment arm had dropped to worse than 20/1600 (<5/400) but was at least light perception. One additional patient in the surgery arm lost visual acuity to this low level by the 36-month examination; a third patient in the surgery arm lost visual acuity to the level of hand motions based on a report from a non-SST ophthalmologist.

Distributions of changes in visual acuity from baseline to scheduled follow-up examinations are summarized in Table 5. Large improvements and large declines in visual acuity from baseline were observed in both treatment arms at each examination. Forty-eight eyes (42%) in the observation arm and 74 (66%) in the surgery arm experienced improvements in visual acuity of 2 lines or more at 1 examination or more after enrollment, primarily before the 12-month examination. Of these eyes, 25 (52%) of 48 in the observation arm and 39 (53%) of 74 in the surgery arm later lost visual acuity to the baseline level or worse. Median 24-month changes in visual acuity were a loss of 2 lines in the observation arm and a loss of 1 line in the surgery arm (P=.14, Wilcoxon rank sum test). The distributions of change in visual acuity differed most at the 12-month examination (P=.02, Wilcoxon rank sum test, in favor of surgery). Based on 97 study eyes in the observation arm and 103 eyes in the surgery arm that had visual acuity measured at the 24-month examination, the numbers and percentages with successful outcomes (SST definition) were 44 (45%) and 55 (53%), respectively (P=.26, χ2 test). These observed rates yield a success rate of 1.18 (95% CI, 0.89–1.56), that is, an estimated relative benefit of 18% for surgery but with a confidence interval that includes 1.0, indicating the possibility of no benefit.

Table 5.

Distribution of Patients by Change in Visual Acuity (VA) of the Study Eye from Baseline to Examinations at Specified Times After Enrollment, SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Patients by Time After Enrollment by Treatment Arm |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 mo |

6 mo |

12 mo |

24 mo |

36 mo |

||||||

| Change in | Observation (n = 99) | Surgery (n = 107) | Observation (n =99) | Surgery (n = 105) | Observation (n = 103) | Surgery (n = 106) | Observation (n = 97) | Surgery (n = 103) | Observation (n = 78) | Surgery (n = 90) |

| ≥4 Lines better | 6 (6) | 16 (15) | 8 (8) | 15 (14) | 4 (4) | 16 (15) | 10 (10) | 17 (17) | 8 (10) | 17 (19) |

| 2–3 Lines better | 12 (12) | 27 (25) | 14 (14) | 25 (24) | 13 (13) | 19 (18) | 11 (11) | 11 (11) | 8 (10) | 15 (17) |

| <2-Line change | 49 (49) | 35 (33) | 36 (36) | 34 (32) | 33 (32) | 34 (32) | 23 (24) | 27 (26) | 21 (27) | 16 (18) |

| 2–3 Lines worse | 22 (22) | 16 (15) | 23 (23) | 13 (12) | 17 (17) | 11 (10) | 14 (14) | 15 (15) | 11 (14) | 7 (8) |

| 4–5 Lines worse | 8 (8) | 4 (4) | 13 (13) | 6 (6) | 19 (18) | 9 (8) | 12 (12) | 13 (13) | 14 (18) | 16 (18) |

| ≥6 Lines worse | 2 (2) | 9 (8) | 5 (5) | 12 (11) | 17 (17) | 17 (16) | 27 (28) | 20 (19) | 16 (21) | 19 (21) |

| Median change, lines | −0.4 | + 0.8 | −0.6 | + 0.4 | −1.6 | −0.2 | −2.0 | −1.0 | −2.1 | −0.9 |

Abbreviation: SST, Submacular Surgery Trials.

One visual acuity line equals 5 letters. A fewer than 2-line change was defined as a visual acuity score no more than 7 letters (1.4 lines) worse or 7 letters better than baseline. Two to 3 lines better (or worse) was defined as a visual acuity score 8 letters (1.6 lines) to 17 letters (3.4 lines) better (or worse) than baseline.

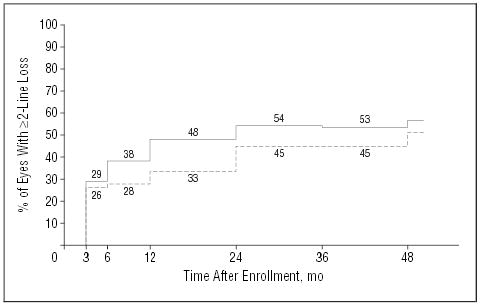

Figure 1 displays the percentages of study eyes with a visual acuity at each follow-up examination of 2 lines or more (≥ 8 letters) worse than at baseline (defined as “failures” for SST purposes), after considering both losses and recoveries of visual acuity and patients who missed the 24-month examination but had a 36- or 48-month examination (2-state model). The percentages of eyes with successful outcomes at the 24-month examination (and 95% CIs) calculated from the 2-state model are 46% (36%–55%) in the observation arm and 55% (46%–64%) in the surgery arm. These percentages yield a success ratio of 1.20 (95% CI, 0.92–1.58), nearly identical to that calculated from patients examined at 24 months. Although the percentage of eyes in the surgery arm that had lost 2 lines or more of visual acuity (failures) was smaller than the percentage of eyes in the observation arm at each examination, the ratio of successful outcomes in surgery eyes relative to observation eyes did not reach 1.5, the smallest success ratio defined to be clinically significant when the trial was designed, at any examination. Furthermore, only at the 12-month examination was the 95% CI on the success ratio (1.35) consistent with a benefit to surgery in the full group of patients (95% CI, 1.05–1.71).

Figure 1.

Percentages of patients in each treatment arm who had a visual acuity of the study eye of 2 lines or more (≥8 letters) worse than at baseline by each examination after study enrollment. Based on a model that considers both losses and recoveries of visual acuity (P=.13, χ2 test). Solid line indicates observation arm (n=113 patients); broken line, surgery arm (n=112 patients).

Subgroups of patients defined by baseline characteristics that were potential predictors of visual acuity outcomes were examined by treatment arm for consistency with overall findings. These included age (≤45 years, >45years), gender, smoking history (ever, never), use of any hypertensive medication, visual acuity of the study eye (≥20/100, <20/100), visual acuity of the fellow eye (≥20/20, <20/20), size of the subfoveal lesion (≤2 DA, >2 DA), earlier laser treatment (yes, no), type of CNV (classic only, both classic and occult), and eligibility for enrollment based on strict application of criteria (eligible, ineligible). In 4 subgroups of patients of the 20 subgroups considered, there was a suggestion that surgery had been beneficial for 2 years or longer: those older than 45 years (n=130), women (n=125), those using antihypertensive agents (n=42), and patients who had visual acuity in the study eye worse than 20/100 at baseline (n=92).

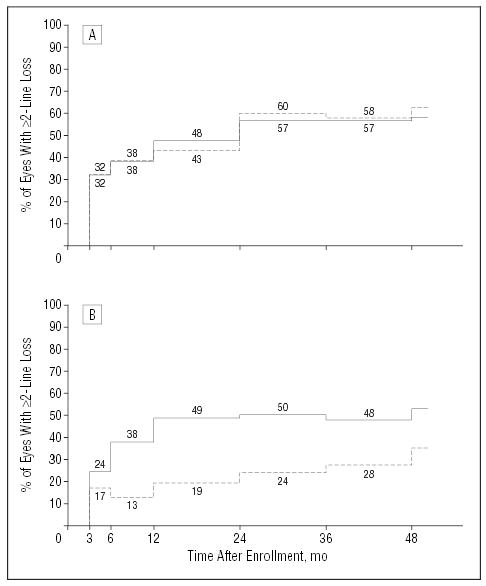

The estimated percentages of patients with a 2-line or greater loss in visual acuity for the subgroups of patients whose baseline visual acuity was 20/50 to 20/100 and 20/125 and poorer are seen in Figure 2A and B, respectively. In the subgroup of eyes with a baseline visual acuity of 20/100 or better (Figure 2A), median visual acuity in the observation arm dropped from 20/64 at baseline to 20/125 at the 24-month examination and in the surgery arm from 20/80 at baseline to 20/160 after 24 months. Of 22 eyes in the surgery arm that had better visual acuity at the 3-month examination (by ≥8 letters) than at baseline, 9 had lost visual acuity to 8 letters or more worse than baseline by the 24-month examination. Median 24-month changes in visual acuity in this subgroup were losses of 2.8 lines in the observation arm and 2.9 lines in the surgery arm (Table 6). The success ratio for this subgroup of eyes was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.61–1.40).

Figure 2.

Percentages of patients in each treatment arm who had a visual acuity of the study eye of 2 lines or more (≥8 letters) worse than at baseline by each examination after study enrollment and by initial visual acuity of the study eye. Based on a model that considers both losses and recoveries of visual acuity. Solid lines indicate observation arm; broken lines, surgery arm. A, Patients whose study eye visual acuity was 20/100 or better (20/50–20/100) at the time of enrollment (68 observation eyes, 65 surgery eyes; P=.56, χ2 test). B, Patients whose study eye visual acuity was worse than 20/100 (≥20/125) at the time of enrollment (45 observation eyes, 47 surgery eyes; P=.003, χ2 test).

Table 6.

Distribution of Patients by Change in Visual Acuity (VA) of the Study Eye From Baseline to Examinations at Specified Times After Enrollment by Baseline VA, SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Patients, by Time After Enrollment by Treatment Arm |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 mo |

6 mo |

12 mo |

24 mo |

36 mo |

||||||

| Change in VA | Observation | Surgery | Observation | Surgery | Observation | Surgery | Observation | Surgery | Observation | Surgery |

| Subgroup With Study Eye VA 20/50–20/100 at Baseline | ||||||||||

| No. of patients | 58 | 62 | 56 | 63 | 59 | 62 | 57 | 62 | 45 | 50 |

| ≥2 Lines better | 6 (10) | 22 (35) | 6 (11) | 16 (25) | 7 (12) | 17 (27) | 11 (19) | 13 (21) | 10 (22) | 13 (26) |

| <2-Line change | 31 (53) | 19 (31) | 26 (46) | 22 (35) | 21 (36) | 17 (27) | 13 (23) | 11 (18) | 9 (20) | 7 (14) |

| 2–3 Lines worse | 15 (26) | 12 (19) | 13 (23) | 11 (17) | 10 (17) | 8 (13) | 7 (12) | 12 (19) | 5 (11) | 5 (10) |

| 4–5 Lines worse | 5 (9) | 2 (3) | 7 (12) | 5 (8) | 11 (19) | 7 (11) | 5 (9) | 10 (16) | 9 (20) | 13 (26) |

| ≥6 Lines worse | 1 (2) | 7 (11) | 4 (7) | 9 (14) | 10 (17) | 13 (21) | 21 (37) | 16 (26) | 12 (27) | 12 (24) |

| Median change, | −0.6 | +0.2 | −0.6 | −0.8 | −2.0 | −0.8 | −2.8 | −2.9 | −2.8 | −3.5 |

| Median VA, Snellen equivalent | 20/80 | 20/80 | 20/80 | 20/80 | 20/100 | 20/80 | 20/125 | 20/160 | 20/125 | 20/125 |

| Subgroup With Study Eye VA 20/125–20/800 at Baseline | ||||||||||

| No. of patients | 41 | 45 | 43 | 42 | 44 | 44 | 40 | 41 | 33 | 40 |

| ≥2 Lines better | 12 (29) | 21 (47) | 16 (37) | 24 (57) | 10 (23) | 18 (41) | 10 (25) | 15 (37) | 6 (18) | 19 (48) |

| <2-Line change | 18 (44) | 16 (36) | 10 (23) | 12 (29) | 12 (27) | 17 (39) | 10 (25) | 16 (39) | 12 (36) | 9 (22) |

| 2–3 Lines worse | 7 (17) | 4 (9) | 10 (23) | 2 (5) | 7 (16) | 3 (7) | 7 (18) | 3 (7) | 6 (18) | 2 (5) |

| ≥4 Lines worse | 4 (10) | 4 (9) | 7 (16) | 4 (10) | 15 (32) | 6 (14) | 13 (34) | 7 (17) | 9 (27) | 10 (25) |

| Median change | +0.2 | +1.4 | 0.0 | +2.0 | −1.4 | +0.9 | −1.4 | +0.2 | −1.4 | +1.3 |

| Median VA, Snellen equivalent | 20/200 | 20/160 | 20/250 | 20/160 | 20/250 | 20/200 | 20/250 | 20/250 | 20/320 | 20/200 |

Abbreviation: SST, Submacular Surgery Trials.

Among eyes in the subgroup with a baseline visual acuity worse than 20/100 (Figure 2B), median visual acuity in both treatment arms dropped by 1 line, that is, from 20/200 at baseline to 20/250 at the 24-month examination. However, the interquartile range for observation eyes was 20/200 to 20/500 while the interquartile range for surgery eyes was 20/125 to 20/320, and the mean visual acuity was 20/320 and 20/200, respectively. Of 21 eyes in the surgery arm that had better visual acuity at the 3-month examination (by ≥8 letters) than at baseline, only 2 had lost visual acuity to 8 letters or more worse than baseline by the 24-month examination. Median 24-month change in visual acuity was a loss of 1.4 lines (7 letters) in the observation arm and a gain of 0.2 line (1 letter) in the surgery arm (Table 6; P=.08, Wilcoxon rank sum test). In this subgroup, 31 (81%) of 41 eyes in the surgery arm vs 20 (50%) of 40 eyes in the observation arm had 24-month visual acuity similar to (no more than 7 letters different from) or better than baseline visual acuity (P=.02, χ2 test), yielding a success ratio of 1.53 (95% CI, 1.08–2.16). To ensure that these findings were not an artifact of the prespecified subgrouping, patients were divided into 3 subgroups based on the baseline visual acuity of the study eye. Two-year visual acuity changes suggested no benefit and possible harm from surgery for eyes with a visual acuity of 20/50 to 20/64 (success ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.48–1.52), a small benefit to surgery for eyes with a visual acuity of 20/80 to 20/125 (success ratio, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.69–2.14), and a large benefit to surgery for eyes with an initial visual acuity of 20/160 to 20/800 (success ratio, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.06–2.11). In a logistic regression model with success as the dependent variable and terms for initial visual acuity, treatment arm, and interaction between surgery and visual acuity as independent variables, the interaction was statistically significant by the conventional criterion (P=.04). Interaction also was supported when potentially predictive baseline characteristics selected from univariate subgroup analyses (age, gender, and use of antihypertensive agents) were included as independent variables together with treatment arm, initial visual acuity of the study eye, and a term for interaction between surgery and initial visual acuity of the study eye in most logistic regression models (P≤.04).

CONTRAST THRESHOLD AND READING SPEED

The mean change in contrast threshold of study eyes from baseline to the 24-month follow-up examination was no change in both treatment arms (Table 7). Neither the distributions of contrast threshold (data not shown) nor the distributions of change in contrast threshold differed by treatment arm at any examination (P≥.15, Wilcoxon rank sum tests).

Table 7.

Distribution of Patients by Changes in Contrast Threshold of Study Eyes From Baseline to Examinations at Specified Times After Enrollment in the SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Patients by Time Since Enrollment by Treatment Arm |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 Months |

6 Months |

12 Months |

24 Months |

36 Months |

||||||

| Change* | Observation (n = 99) | Surgery (n = 106) | Observation (n = 97) | Surgery (n = 104) | Observation (n = 100) | Surgery (n = 106) | Observation (n = 95) | Surgery (n = 103) | Observation (n = 75) | Surgery (n = 87) |

| Improved: | ||||||||||

| ≥3 Segments | 8 (8) | 4 (4) | 8 (8) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 11 (12) | 10 (10) | 5 (7) | 9 (10) |

| 1–2 Segments | 20 (20) | 31 (29) | 25 (26) | 33 (32) | 30 (30) | 35 (33) | 17 (18) | 36 (35) | 23 (31) | 33 (38) |

| <1-Segment change | 40 (40) | 43 (41) | 29 (30) | 39 (38) | 31 (31) | 30 (28) | 34 (36) | 25 (24) | 24 (32) | 16 (18) |

| Worsened: | ||||||||||

| 1–2 Segments | 27 (27) | 25 (24) | 32 (33) | 23 (22) | 27 (27) | 26 (25) | 23 (24) | 24 (23) | 14 (19) | 18 (21) |

| ≥3 Segment | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 9 (9) | 9 (8) | 10 (11) | 8 (8) | 9 (12) | 11 (13) |

| Median change, No. of segments | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviation: SST, Submacular Surgery Trials.

One segment contains 3 letters. One-segment change equals 0.15–log unit change.

Changes in reading speed using only the study eye from baseline to follow-up examinations (Table 8) paralleled changes in visual acuity but were more striking: changes to the 3- and 6-month examinations favored surgery (P<.01, Wilcoxon rank sum tests), but the benefit had diminished in comparison to observation by the 24-month examination (P=.07, Wilcoxon rank sum test). In the subgroup of eyes with a visual acuity worse than 20/100 at baseline, changes in reading speed favored surgery somewhat at each examination. By the 24-month examination, the median change in this subgroup of eyes was a loss of 7 words per minute in the observation arm and a gain of 7 words per minute in the surgery arm (P=.10, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Table 8.

Distribution of Patients by Change in Reading Speed From Baseline, Using Only the Study Eye, to Examinations at Specified Times After Enrollment in the SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Patients by Time Since Enrollment by Treatment Arm |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 mo |

6 mo |

12 mo |

24 mo |

36 mo |

||||||

| Change, wpm | Observation (n = 95) | Surgery (n = 104) | Observation (n = 94) | Surgery (n = 103) | Observation (n = 97) | Surgery (n = 104) | Observation (n = 91) | Surgery (n = 101) | Observation (n = 72) | Surgery (n = 83) |

| >30 Faster | 11 (12) | 33 (32) | 12 (13) | 33 (32) | 10 (10) | 21 (20) | 9 (10) | 22 (22) | 6 (8) | 16 (19) |

| 11–30 Faster | 20 (21) | 24 (23) | 20 (21) | 21 (20) | 20 (21) | 22 (21) | 9 (10) | 13 (13) | 11 (15) | 13 (16) |

| ≤10 Change | 30 (32) | 28 (27) | 23 (24) | 21 (20) | 21 (22) | 22 (21) | 28 (31) | 22 (22) | 13 (18) | 12 (14) |

| 11–30 Slower | 17 (18) | 11 (11) | 20 (21) | 16 (16) | 18 (19) | 19 (18) | 12 (13) | 16 (16) | 15 (21) | 15 (18) |

| >30 Slower | 17 (18) | 8 (8) | 19 (20) | 12 (12) | 28 (29) | 20 (19) | 33 (36) | 28 (28) | 27 (38) | 27 (33) |

| Median change, wpm | 0 | +15 | −6 | +10 | −8 | +3 | −10 | −4 | −22 | −12 |

Abbreviations: SST, Submacular Surgery Trials; wpm, words per minute.

COMPLICATIONS AND ADDITIONAL TREATMENTS TO STUDY EYES

Visually significant cataract, defined as either cataract surgery or lens opacity reported by the SST ophthalmologist to be sufficient to reduce visual acuity by at least 2 lines in a normal eye, developed in the initially phakic study eyes of 1 of 107 patients in the observation arm and 44 of 112 patients in the surgery arm. All but 5 of the 44 study eyes reported to have visually significant cataract were in the subgroup of patients 50 years or older. No study eye in the observation arm but 27 eyes in the surgery arm had cataract surgery. Of the 27 patients who had cataract surgery in the study eye, 26 were 50 years or older. By 24 months after enrollment, the cumulative percentage of initially phakic eyes in the surgery arm that had had cataract surgery was 14%. Eyes in the surgery arm that had cataract surgery had a mean change in visual acuity from baseline to the 24-month examination similar to the change in eyes that did not have cataract surgery: mean losses of 1.2 lines and 1.3 lines, respectively. However, following cataract surgery, eyes in the surgery arm had smaller mean changes in visual acuity from baseline to the 36-month (3-letter improvement) and 48-month (3-letter loss) examinations than phakic eyes that did not have cataract surgery (remained close to a 1.3-line loss). The only case of endophthalmitis developed after cataract surgery in an eye in the surgery arm.

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachments were reported in 5 eyes in the surgery arm but in no eye in the observation arm; all of the retinal detachments were repaired successfully with attachment of the macula after a single surgery. Other ocular complications were rare. As noted earlier, 3 eyes in the surgery arm lost visual acuity to a level that could not be measured quantitatively using study methods at 1 examination or more. Of these 3 eyes, 1 eye had visually significant cataract reported throughout the remaining follow-up period, beginning with the 12-month examination. A second patient had been followed up outside the SST since the 6-month examination; when examined by the traveling vision examiner at the 48-month examination, the patient was able to read 12 letters with the study eye at a test distance of 0.5 m, corresponding to a visual acuity of 5/320 (20/1280). No reason was reported for the loss of visual acuity in the third surgery eye with unmeasurable visual acuity. The single eye in the observation arm that had visual acuity reported to be worse than 5/400 (<20/1600) was followed outside the SST Group H Trial starting with the 12-month examination; no measurement made by an SST examiner was available after the 6-month examination.

Sixty-three eyes treated surgically had leakage of fluorescein dye from CNV at the periphery of the postoperative area of disturbed retinal pigment epithelium, as judged at the Photograph Reading Center, on 1 or more fluorescein angiograms by the 24-month examination, yielding a 24-month cumulative incidence of 58%. Of these 63 eyes, 44 eyes also had fluorescein leakage within the area of disturbed retinal pigment epithelium. Another 14 eyes had leakage observed only within the disturbed area. Submacular surgery was repeated in 24 eyes; 18 eyes had laser photocoagulation to CNV; and 3 eyes had photodynamic therapy with verteporfin. Altogether, 42 (38%) surgery eyes had 1 or more additional treatments for CNV by the 24-month examination. Eyes that had fluorescein leakage from CNV, whether located peripherally or centrally and regardless of whether the CNV was treated, lost a mean of 1.5 lines of visual acuity by the 12-month examination and a mean of 2.5 lines by the 24-month examination. In contrast, eyes that did not have fluorescein leakage from CNV during the first 24 months after surgery had stable or improved visual acuity over the 2-year period with a mean gain of 6 letters (1.2 lines) from baseline to the 24-month examination. Six eyes in the observation arm had 1 or more treatments for CNV by the 24-month examination; 2 of these 6 eyes had laser photocoagulation and 4 had photodynamic therapy. Of eyes in the surgery arm that remained free of recurrent CNV, only 26% had lost 2 lines or more of visual acuity by the 24-month examination compared with 63% of surgery eyes treated for recurrence, 43% of surgery eyes that had recurrence but no subsequent treatment, and 54% of eyes in the observation arm.

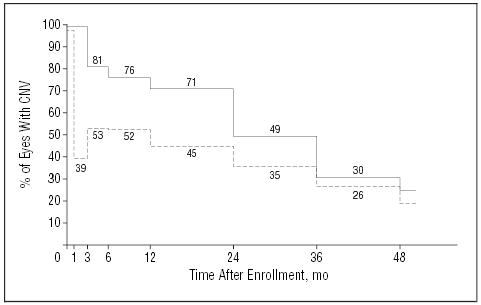

Although fluorescein leakage from CNV was common after surgery, leakage from CNV was observed less often in eyes in the surgery arm than in the observation arm at each examination from 3 months through 24 months (Figure 3), based on reviews of photographs at the Photograph Reading Center. At the 24-month examination, 35% of surgery eyes (95% CI, 25%–45%) and 49% of observation eyes (95% CI, 40%–59%) had fluorescein leakage from CNV (P=.06, χ2 test). Thereafter, leakage from CNV was observed with similar frequency in eyes in both treatment arms.

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients in each treatment arm whose study eye had leakage of dye from choroidal neovascularization (CNV) observed during central review of fluorescein angiograms taken at each examination. The model considers both events (leakage) and recoveries (no leakage); P<.001, χ2 test. Solid line indicates observation arm (n=113 patients); broken line, surgery arm (n=112 patients).

CHANGES IN THE SIZE OF SUBFOVEAL LESIONS

Three months after enrollment, the subfoveal lesions of more than half the eyes in both treatment arms were classified by personnel at the Photograph Reading Center to be in a smaller size category or in the same size category as at baseline (Table 9). However, the subfoveal lesions of nearly three quarters of the eyes in both treatment arms had increased in size by at least 1 category by the 24-month examination. The size of the lesion was smaller than at baseline in only 2 eyes in each arm (P=.43, χ2 test for trend).

Table 9.

Changes in Size of Subfoveal Lesions From Baseline to Follow-up Examinations at Specified Times After Enrollment, SST Group H Trial

|

No. (%) of Patients by Time After Enrollment by Treatment Arm |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 mo |

6 mo |

12 mo |

24 mo |

36 mo |

||||||

| Change From Baseline, Categories* | Observation (n = 98) | Surgery (n = 101) | Observation (n = 94) | Surgery (n = 101) | Observation (n = 99) | Surgery (n = 104) | Observation (n = 89) | Surgery (n = 96) | Observation (n = 74) | Surgery (n = 80) |

| Smaller or no change | 57 (58) | 54 (53) | 40 (43) | 48 (48) | 35 (35) | 30 (29) | 23 (26) | 26 (27) | 16 (22) | 19 (24) |

| 1 Larger | 29 (30) | 34 (34) | 33 (35) | 38 (38) | 30 (30) | 51 (49) | 25 (28) | 38 (40) | 24 (32) | 30 (38) |

| 2 Larger | 8 (8) | 10 (10) | 17 (18) | 13 (13) | 21 (21) | 18 (17) | 20 (22) | 22 (23) | 18 (24) | 18 (22) |

| ≥3 Larger | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 13 (13) | 5 (5) | 21 (24) | 10 (10) | 16 (22) | 13 (16) |

| Median change, No. of categories | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 |

See the “Evaluation of Baseline Photographs” subsection of the “Methods” section in the text for definition of the categories.

COMMENT

The SST Research Group did not observe the large benefit of surgical removal of subfoveal CNV compared with observation that the SST Group H Trial was designed to detect or rule out. Promising findings reported from earlier investigations of submacular surgery to remove subfoveal CNV from eyes with the ocular histoplasmosis syndrome23–25 led to the hope that a large enough benefit would be achieved to warrant the cost and perceived risks of submacular surgery. The sample size was selected to provide sufficient power to detect or to rule out a large 2-year benefit of surgery, that is, 50% more eyes with stable or improved visual acuity 2 years after enrollment compared with baseline visual acuity. Thus, a smaller benefit of surgery, such as 25% or 30% which many trials have been designed to detect, could be neither confirmed nor dismissed. Data provided by the SST Group H Trial suggest a better visual acuity outcome in 18% to 20% more eyes treated with surgery than eyes in the observation arm when all eyes enrolled are considered. This effect size is similar to that ultimately observed 2 years after randomization of similar eyes in the SST pilot study. However, the 95% CIs on both estimates included 1.0, indicating the possibility of no benefit to surgery overall. Encouraging differences between treatment arms for visual acuity and reading speed were observed during the first year of patient follow-up (Tables 4, 5, and 8 and Figure 1). The high incidence of recurrent CNV and development or progression of cataract suggest that these factors likely accounted for much of the loss of visual acuity in the second and later years in the surgery arm.

Retrospective review of data from surgical case series prior to initiation of the SST pilot study in 1993 and unpublished findings from the SST randomized pilot trial in similar patients suggested that the subgroup of eyes with a visual acuity worse than 20/100 was the one more likely to benefit from submacular surgery; this finding was confirmed in the SST Group H Trial. Among characteristics of patients, eyes, and lesions at the time of enrollment, baseline visual acuity of the study eye again was found to be an important predictor of a successful outcome (stabilization or improvement of visual acuity) 2 years after surgery in both univariate and multivariate analyses. The 2-year success ratio of surgery vs observation was 1.53 (95% CI, 1.08–2.16) for study eyes with an initial visual acuity worse than 20/100 (n=92) and 0.92 (95% CI, 0.61–1.40) for study eyes with an initial visual acuity of 20/100 or better (n=133). These CIs indicate that there was at least a small benefit to surgery, and likely a large benefit, among eyes with an initial best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/100, but there was no benefit from surgery in eyes with an initial visual acuity of 20/100 or better. Regression analyses supported a qualitative interaction between surgery and initial visual acuity with respect to visual acuity outcome.

A rationale for submacular surgery was that surgery would limit the size of the subfoveal lesion and that limiting the size of the subfoveal lesion would lead to less loss of visual acuity. Lesions in both arms tended to enlarge, owing to continued growth of the lesions in the observation arm and recurrent CNV in the surgery arm. Although changes in lesion size, as assessed categorically in the SST, differed somewhat between eyes in the surgery arm and eyes in the observation arm, with the differences favoring surgery, the differences were small and not statistically significant. Furthermore, initial stabilization or improvement in the visual acuity of eyes in the surgery arm was not maintained. Findings regarding stable measurements of contrast threshold over time in both treatment arms were consistent with the observation that the size of the subfoveal lesions remained at 9 DA or smaller in more than 80% of the eyes through the 48-month examination. The influence of an extrafoveal ingrowth site, reported to portend a better visual acuity outcome,48 was not evaluated by the SST Research Group.

Despite the multicenter design of the SST Group H Trial and surgical procedures performed by 32 different retinal surgeons with varying experience with submacular surgery, few serious operative complications arose. Postoperative ocular complications other than cataract also were reported infrequently. The incidence of fluorescein leakage from CNV at the periphery of the area of disturbed retinal pigment epithelium observed following surgery on postsurgery fluorescein angiograms by personnel at the SST Photograph Reading Center was higher than rates of persistent or recurrent CNV following laser photocoagulation reported for initially extrafoveal or juxtafoveal neovascular lesions.20,21 The posttreatment lesions following surgery and following laser photocoagulation were of different types and different protocols for management of recurrent CNV were adopted. Recurrence rates in the SST Group H Trial were similar to those reported from a retrospective single-center follow-up study of similar cases treated with submacular surgery.49 Options for treatment of recurrent CNV were limited to laser photocoagulation or a second surgical procedure when the SST Group H Trial was initiated. The potential for a better outcome if photodynamic therapy with verteporfin or other treatments had been available throughout the study period cannot be evaluated using the SST database. If the rate of recurrent CNV following surgery in this patient population can be reduced by use of pharmaceutical adjuvants or other means, better visual acuity outcomes with submacular surgery may be possible. However, a randomized trial would be necessary to provide sufficient supporting evidence.

Findings from interviews regarding vision-targeted quality of life are reported in a companion article in this issue.28 They largely mirror the visual acuity findings except that there was a trend toward improved scores in both treatment arms overall. Self-reported visual function favored surgery through the 24-month interview among patients who already had bilateral CNV at baseline. However, differences between surgery and observation arms decreased thereafter for most aspects of vision-targeted quality of life. Smaller differences between treatment arms in favor of surgery were found for initially unilateral cases.

Treatments such as photodynamic therapy26,27 and corticosteroids have been proposed to treat patients similar to those who participated in this trial, but their effectiveness has not been documented in randomized trials. Furthermore, the total cost of newer approaches to treatment of CNV may not differ substantially from the cost of submacular surgery. Thus, in future clinical trials for patients eligible for the SST Group H Trial that are designed with full knowledge of the outcomes observed by the SST Research Group, the treatment arm(s) to which surgery would be compared likely would be different and a smaller difference in outcomes between treatment arms might be specified to be clinically relevant.

Although rates of new CNV development in initially unaffected fellow eyes of patients in the SST Group H Trial are yet unavailable, 89 (92%) of 97 fellow eyes in the observation arm and 96 (93%) of 103 fellow eyes in the surgery arm had a best-corrected visual acuity at the 24-month examination that was similar to (168 eyes) or better than (17 eyes) baseline visual acuity. Thus, 15 fellow eyes had lost 2 lines or more of visual acuity during the first 2 years after enrollment. Ophthalmologists should continue to monitor the fellow eyes of patients who have a neovascular lesion in only 1 eye so that the second eye can be treated promptly with laser photocoagulation if CNV develops in an extrafoveal or juxtafoveal location.

Findings from the SST Group H Trial do not support submacular surgery in similar eyes that have a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/100 or better. However, patients who have subfoveal CNV and best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/100, as measured in the SST, and who meet other criteria for enrollment in the SST Group H trial may wish to consider submacular surgery to improve their chances of retaining or improving visual acuity for at least 2 years. Before such patients decide to undergo surgery, their ophthalmologists should discuss with them the findings from the SST Group H Trial and the pilot trial for similar patients that support surgery in these eyes, the small risk of retinal detachment (<5%), the larger risks of recurrent CNV (≥ 50%), the risk of cataract in older patients, the possibility that they will require additional treatment for these complications after submacular surgery, the status of the fellow eye and the long-term risk of vision loss in that eye, and the scarcity of information provided to date regarding the benefits and risks of other treatments available.

Members of the SST Research Group

Members of the Submacular Surgery Trials Research Group April 1997 through September 2003 Clinical Centers and Personnel Who Contributed Data for the Group H Trial

Centers are listed in alphabetical order by city. The number of patients enrolled is given in parentheses after the center location. Personnel listed are principal investigators and other personnel who had performed 5 or more examinations or procedures by the end of data collection on September 30, 2003.

Clinical Centers

Emory University Eye Center, Atlanta, Ga (25): Principal Investigator: G. Baker Hubbard III, MD; Paul Sternberg, Jr, MD (1997–2002); Antonio Capone, MD (1997–1999); SST Coordinator: Jayne M. Brown; Vision Examiners: Lindy G. Dubois, COMT; Judy Johnson, COMT; Natalie Schmitz; Photographers: James P. Gilman, CRA; Robert A. Myles, CRA;Ray Swords.

The Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute, Baltimore, Md (22): Principal Investigator: Julia A. Haller, MD; Ophthalmologists: Peter A. Campochiaro, MD; Mark Humayun, MD; Eugene de Juan, MD; Dante J. Pieramici, MD; SST Coordinators and Vision Examiners: Michaele Hartnett, COT; Patricia L. Hawse, COMT; Tracey L. Porter, COT; Ann Eager Youngblood, COA; Photographers: Judith E. Belt; Dennis Cain, CRA; David Emmert; Rachel E. Falk; Mark Herring; Jacquelyn McDonald.

Illinois Retina Associates, Chicago and Harvey, Ill (3): Principal Investigator: Mathew W. MacCumber, MD, PhD; Ophthalmologists: Joseph Civantos, MD; Kirk H. Packo, MD; SST Coordinators and Vision Examiners: Bruce L. Gaynes, OD, Pharm D; Laurie Rago, COA; Carrie Violetto; Photographers: Douglas A. Bryant, CRA; Frank Morini.

Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland, Ohio (7): Principal Investigator: Hilel Lewis, MD; Ophthalmologist: Peter K. Kaiser, MD; SST Coordinators: Laura Holody, COA; Susan C. Rath, PA-C; Larisa S. Schaaf, RN; Vision Examiner: Anthony Fattori; Photographers: Tami Fecko; Deborah J. Ross, CRA.

Retina Associates of Cleveland (2): Principal Investigator: Lawrence J. Singerman, MD; Ophthalmologist: Michael A. Novak, MD; SST Coordinator and Vision Examiner: Kim Tilocco DuBois, COA, CCRP; Photographers: John DuBois, CRA; David Lehnhardt, COA.

Ohio State University, Columbus (17): Principal Investigator: Frederick H. Davidorf, MD; Ophthalmologist: Robert Chambers, DO; SST Coordinator: Cynthia Taylor; Vision Examiners: Jill Milliron, COA; Jerilyn Perry, COT; Photographer: Scott Savage, EMT-A.

Texas Retina Associates, Dallas (2): Principal Investigator: David G. Callanan, MD; Ophthalmologist: Gary Edd Fish, MD; SST Coordinators: Jodi R. Creighton, COA; Jeff L. Harris, COA; Nancy Resmini; Rubye Rollins; Vision Examiner: Marilyn Andrews, COT; Photographers: Hank A. Aguado, CRA; Bob H. Boleman.

Duke University Eye Center, Durham, NC (20): Principal Investigator: Cynthia A. Toth, MD; Ophthalmologists: Brooks McCuen, MD; Glenn Jaffe, MD; SST Coordinators and Vision Examiners: Malcolm W. Anderson, PA-C, COT; Jennifer V. Caldwell; Photographers: Teresa Jackson Hawks; Gregory C. Hoffmeyer; Jeffrey M. Napoli.

Midwest Eye Institute, Indianapolis, Ind (3): Principal Investigator: John T. Minturn, MD; SST Coordinator: Donna J. Agugliaro, RN; Vision Examiner: Shelly Cohen; Photographer: Carolyn Lamb.

University of Iowa, Iowa City (9): Principal Investigator: James C. Folk, MD; Ophthalmologist: H. Culver Boldt, MD; SST Coordinators: Betty Follmer; Steven A. Wallace; Vision Examiner: Connie Fountain, COT; Photographers: Ed Heffron, MA, CRA; Carolyn Vogel.

Mid-America Retina Consultants, Kansas City, Mo (6): Principal Investigator: William N. Rosenthal, MD; Ophthalmologist: David S. Dyer, MD; SST Coordinators and Vision Examiners: Denise Moore, RN; Barbara Petro, COT; Dalton J. Thibodeaux; Photographer: R. Scott Varner.

Southeastern Retina Associates, Knoxville, Tenn (19): Principal Investigator: John C. Hoskins, MD; Ophthalmologist: Joseph M. Googe, Jr, MD; SST Coordinators: Katie E. Carter, COA; Stephanie M. Evans; Tina Thibodeaux Higdon; Jennifer L. Holton; Vision Examiner: Bruce D. Gilliland, OD; Photographers: Paul Andrew Blais; Philip Michael Jacobus.

Retina and Vitreous Associates of Kentucky, Lexington (24): Principal Investigator: William J. Wood, MD; Ophthalmologist: Rick D. Isernhagen, MD; SST Coordinators: Michelle L. Buck, COA; J. Lynn Cruz, COT; Joni D. James, RN; Jenny L. Wolfe, RN; Vision Examiners: Christine Brown, COT; Wanda Heath, COT; Catherine Millett, COA; Photographers: Marty Reid, COA; Edward Slade, CRA, COA.

Jules Stein Eye Institute, Los Angeles, Calif (1): Principal Investigator: Steven D. Schwartz, MD; Ophthalmologist: Robert Engstrom, MD.

McGee Eye Institute, Oklahoma City (1): Principal Investigator: Reagan H. Bradford, MD; Sumit K. Nanda, MD (1998–2002); SST Coordinator and Vision Examiner: Angela Monlux, COT.

Retinal Consultants of Arizona, Phoenix, Ariz (2): Principal Investigator: Jack O. Sipperley, MD; SST Coordinator and Vision Examiner: Jaclin J. Jacobsen, CRA, COA; Photographer: John J. Bucci.

Retina Vitreous Consultants, Pittsburgh, Pa (8): Principal Investigator: Robert L. Bergren, MD; SST Coordinators: Donna J. Metz, RN; Kathryn Sedory, RN; Christina Trombetta, CST; Vision Examiner: Linda Wilcox, COA; Photographers: David Steinberg, CRA; Alan Campbell, CRA; Gary Vagstad, CRA.

Associated Retinal Consultants, Royal Oak, Mich (1): Principal Investigator: George A. Williams, MD; SST Coordinators and Vision Examiners: Kristi L. Cumming, RN, MSN; Bobbie Lewis, RN; Photographers: Patricia Streasick; Lynette Szydlowski.

Barnes Retina Institute, St Louis, Mo (32): Principal Investigator: Nancy M. Holekamp, MD; Ophthalmologists: Daniel P. Joseph, MD, PhD; Matthew A. Thomas, MD; SST Coordinators and Vision Examiners: Julie Binning, COT; Lynda Boyd, COT; Janel Gualdoni, COT; Virginia S. Nobel, COT; Photographers: Rhonda Allen; Bryan D. Barts; Jon E. Dahl; Timothy S. Holle; Deborah Kaiser, RN, COA; Ella Ort; Matt Raeber; John Mark Rogers.

West Coast Retina Medical Group, Inc, San Francisco, Calif (4): Principal Investigator: H. Richard McDonald, MD; SST Coordinator: Margaret M. Stolarczuk, OD; Vision Examiner: Kevan E. Curren, COA; Photographers: Kelly Ann DeBoer; Sarah M. Huggans.

St Vincent Mercy Medical Center, Retina Vitreous Associates, Toledo, Ohio (17): Principal Investigator: Samuel R. Pesin, MD; Ophthalmologists: Charles K. Dabbs, MD; Nicholas J. Leonardy, MD; SST Coordinator and Vision Examiner: James M. Haener, COT; Photographers: Lauren M. Cedoz, CRA; Richard D. Hill.

Resource Centers

The Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute, Baltimore: