Abstract

Regulating the Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) family of transcription factors is of critical importance to animals, with consequences of misregulation that include cancer, chronic inflammatory diseases, and developmental defects1. Studies in Drosophila melanogaster have proved fruitful in determining the signals used to control NF-κB proteins, beginning with the discovery that the Toll-NF-κB pathway, in addition to patterning the dorsal-ventral (D/V) axis of the fly embryo, defines a major component of the innate immune response in both Drosophila and mammals2,3. Here, we characterize the Drosophila wntD (Wnt inhibitor of Dorsal) gene. We show that WntD acts as a feedback inhibitor of the NF-κB homolog Dorsal during both embryonic patterning and the innate immune response to infection. wntD expression is under the control of Toll-Dorsal signaling, and increased levels of WntD block Dorsal nuclear accumulation, even in the absence of the IκB homolog Cactus. The WntD signal is independent of the common Wnt signaling component Armadillo (β-catenin). By engineering a gene knockout, we show that wntD loss-of-function mutants have immune defects and exhibit increased levels of Toll-Dorsal signaling. Furthermore, the wntD mutant phenotype is suppressed by loss of zygotic dorsal. These results describe the first secreted feedback antagonist of Toll signaling, and demonstrate a novel Wnt activity in the fly.

The D/V axis of the Drosophila embryo is initially patterned by a ventral-to-dorsal nuclear gradient of Dorsal protein activity under the control of Spatzle-Toll signaling4,5. Toll activates Dorsal primarily through the degradation of Cactus, thereby freeing Dorsal to enter the nucleus and activate or repress target genes6. The transcriptional profile that is regulated by Dorsal defines the spatial organization of tissues in the embryo, with ventral-most cells becoming mesoderm, flanked by the mesectoderm and neuroectoderm in more lateral regions, and gut primordia at the poles7.

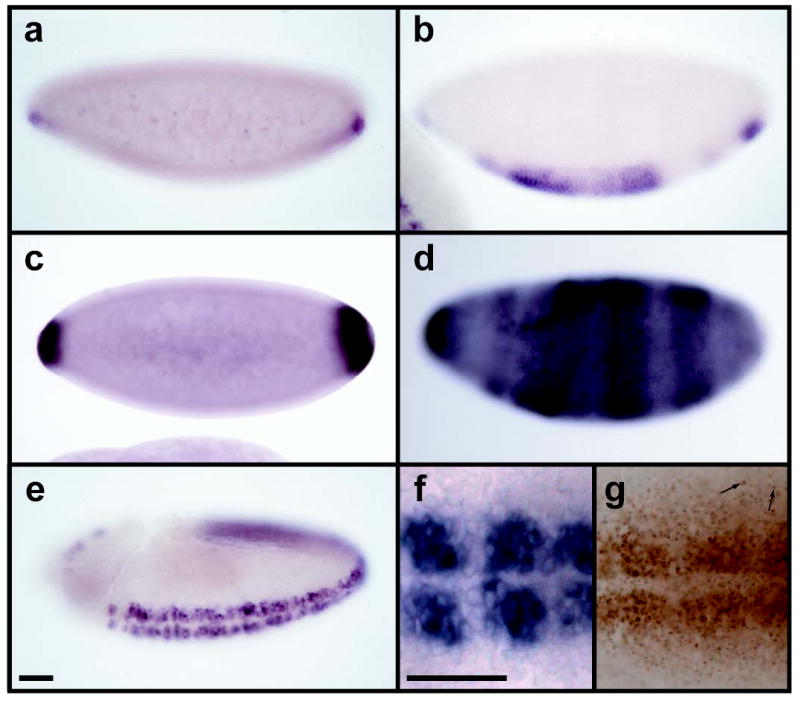

The gene wntD was identified as a member of the Drosophila Wnt family based on a genomic search for Wnt-related genes (synonym CG8458) 8. Examination of wntD RNA in situ revealed that the first detectable expression is seen at the ventral poles of the blastoderm embryo, followed by sequential ventral-to-dorsal expression in the presumptive mesoderm, mesectoderm, and neuroectoderm (fig. 1). Embryos derived from mothers carrying a dominant activated allele of Toll express wntD RNA more broadly and at higher levels than wild type (fig. 1c,d). This demonstrates that wntD expression is induced by Toll signaling. Examination of WntD protein distribution shows that WntD is secreted and travels multiple cell diameters away from producing cells, suggesting that WntD is capable of signaling at a distance (fig. 1f,g).

Figure 1.

wntD is expressed with D/V polarity, and is under the control of Toll signaling. a-e, In situ hybridization to wntD mRNA in wild type embryos (a,b,e) and those derived from Toll10b mothers (c,d). Wild type expression is seen in the ventral poles at stage 5 (a), presumptive mesoderm at stage 6 (b), and neurogenic ectoderm at stage 9 (e). Stronger, expanded wntD expression is seen in Toll10b-derived embryos at stages 5 and 6 (c,d). f,g Close-up ventral views (anterior left) of stage 9 wild type embryos stained for wntD mRNA (f) or with anti-WntD antibody (g). Arrows indicate examples of WntD antigen detected multiple cell diameters away from wntD-expressing cells. Scale bars indicate 50 μm. All embryos here and henceforth oriented anterior left, ventral down, unless otherwise indicated

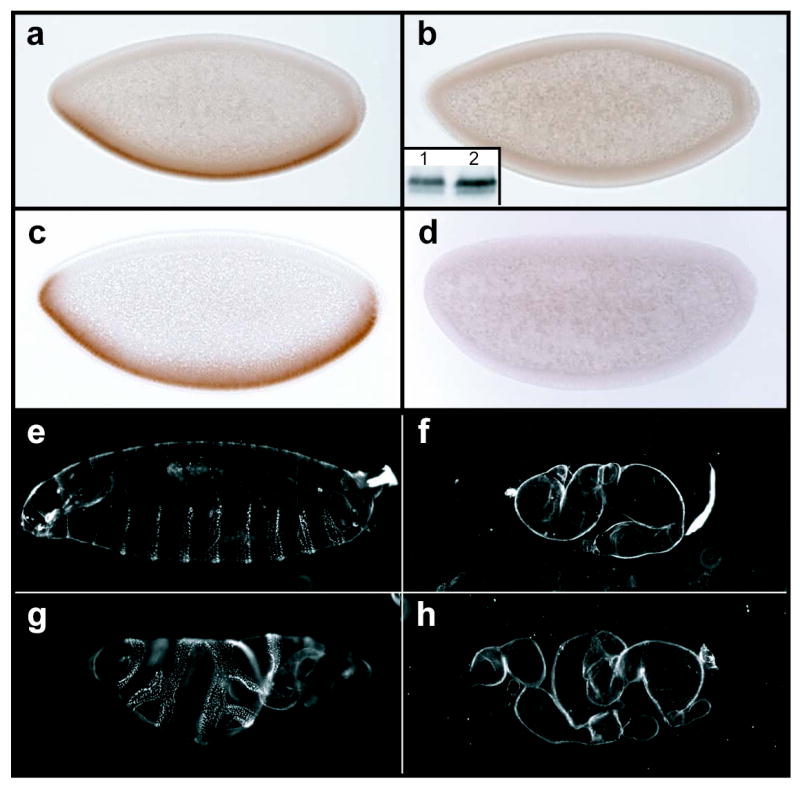

To uncover the signaling activity of WntD in the embryo, we expressed WntD ectopically in the female germline, producing blastoderm stage embryos that contain high levels of WntD protein (data not shown). These embryos lacked detectable nuclear Dorsal (fig. 2b), although total cellular levels of Dorsal protein remained unchanged (fig. 2 inset b). Consequently, the mesodermal Dorsal target gene Twist was not expressed (fig. 2d), and the embryos produced only dorsal cuticle (fig. 2f). Furthermore, the observed defects were specific to dorsal-ventral patterning, as the anterior-posterior patterning gene hunchback was unaffected by WntD (data not shown). Following submission of this manuscript, similar results for the over-expression of WntD were reported by Ganguly et al.9

Figure 2.

Over-expression of WntD blocks Dorsal protein activation independently of Cactus. a,c, Wild type embryos stained with antibodies to Dorsal (a), or Twist (c). b,d, Embryos from females carrying P[nos-Gal4:VP16] and P[UASp-wntD] transgenes, stained with antibodies against Dorsal (b), or Twist (d). inset b, Total Dorsal protein levels (assayed by western blot) are equivalent in wild type embryos (lane 1) and those from P[nos- Gal4:VP16]/P[UASp-wntD] females (lane 2). e-h Cuticles of embryos with the maternal genotypes: wild type (e); P[nos-Gal4:VP16]/P[UASp-wntD] (f); cact1/cact4 (g); and cact1/cact4 ; P[nos-Gal4:VP16]/P[UASp-wntD] (h).

In order to determine the point of intersection between WntD activity and the Toll-Dorsal pathway, we constructed flies that over-express WntD and carry strong hypomorphic alleles of cactus. While maternal cactus mutants exhibited a ventralized phenotype (fig. 2g), those also over-expressing WntD were dorsalized, and indistinguishable from embryos over-expressing WntD alone (fig. 2h). These data demonstrate that WntD, a secreted growth factor, is capable of producing a signal that blocks Dorsal nuclear translocation downstream of, or in parallel to, Cactus. It has been shown previously that Dorsal undergoes Toll-dependent and –independent phosphorylation10, and that Dorsal nuclear localization can be regulated independently of Cactus11.

That WntD is a member of the Wnt family of growth factors raises the question of whether it signals through the well-characterized Frizzled-Armadillo/β-catenin pathway12. We suggest that it does not, based on two lines of evidence: First, germline clones of axin, a negative regulator of Armadillo, do not produce dorsalized embryos13; and second, over-expression of WntD in tissues sensitive to Armadillo signaling does not have any detectable effect (data not shown). These observations however, do not rule out the possibility that WntD signals through a Frizzled receptor in an Armadillo-independent manner.

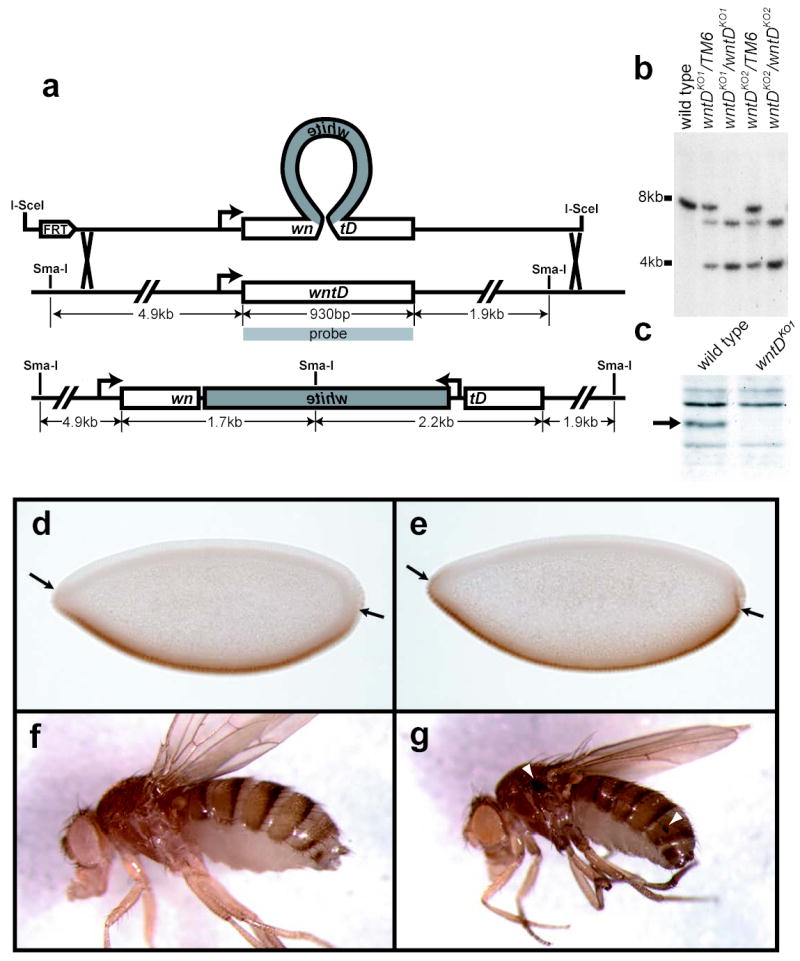

In order to investigate the role of endogenous WntD, we constructed a loss-of-function mutation using “ends-out” gene targeting (fig 3a). The modified wntD locus produced no detectable protein, as assayed by western blot (fig. 3c). Analysis of flies homozygous for either of two wntDKO alleles revealed that wntD is not essential for viability or fertility.

Figure 3.

wntD knockout flies exhibit ectopic Dorsal activation. a, “Ends-out” knockout targeting scheme, illustrating how a white mini-gene was used to interrupt the wntD open reading frame. b, Southern blot of Sma-I digested genomic DNA, confirming proper integration of targeting construct. c, Anti-WntD Western blot of lysate from wild type and wntDKO1 embryos (arrow indicates size of WntD protein). d,e, yw (d) and yw; wntDKO1 (e) embryos stained with antibodies against Dorsal. Arrows show point of ventral-most nuclear Dorsal seen in control embryos. f,g adult female yw (f) and yw; wntDKO1 (g) flies. Arrowheads mark sites of ectopic melanization.

Despite their viability, wntD mutant embryos show an expansion of nuclear Dorsal into the pole regions where endogenous WntD is first detected (fig. 3e). This indicates that the earliest role of WntD in the embryo is to restrict the field of Dorsal activation, thereby ensuring the establishment of the proper boundary between the developing ventral and terminal domains; Dorsal, along with A/P positional information, induces transcription of wntD at the ventral poles of the embryo, and WntD in turn feeds back to repress Dorsal nuclear translocation, and prevent improper spread of the ventral domain. This mechanism stands in contrast to another characterized mode of Dorsal pathway repression at the embryonic termini- that of signaling from the Torso (Tor) receptor tyrosine kinase14. In the case of Torso, signaling at the poles of the embryo selectively interferes with the ability of Dorsal to repress the expression of specific target genes, while exerting only a minor effect on those genes activated by Dorsal14. These data suggest that Torso signaling affects the activity of nuclear Dorsal, whereas WntD signaling affects Dorsal’s nuclear translocation.

In addition to its role in D/V patterning, it has been well-established that Toll-NF-κB signaling has a more evolutionarily conserved role in regulating the innate immune system3,15. During the immune response, Toll induces the nuclear translocation of two NF-κB family members: Dorsal and Dorsal-related immunity factor (Dif). Genetic analysis has suggested that Dif, while dispensable for development, is the major transcription factor involved in the Toll-mediated immune response16. In addition to Dorsal and Dif, the fly immune response also uses a third NF-κB related protein, Relish, which is activated upon signaling by PGRP-LC and Imd17,18. Together, these pathways regulate the expression of hundreds of genes following microbial infection19.

In light of the interaction between WntD and Dorsal in the embryo, we asked if WntD could be playing a role later in the fly’s life as a repressor of Toll/Dorsal-mediated immunity. RT-PCR was used to confirm expression of endogenous wntD RNA in adults (data not shown). wntD mutant adults appear normal, with the exception that at low frequency (1-2%), we have observed sites of ectopic melanization, most notably on the wing hinge (fig. 3g). This is consistent with a role for WntD in maintaining low basal levels of Toll-Dorsal signaling, as other mutations that hyper-activate Toll show increased levels of phenoloxidase-driven melanization20,21. Furthermore, Dorsal has been shown to be an essential component of the melanization response in larvae22.

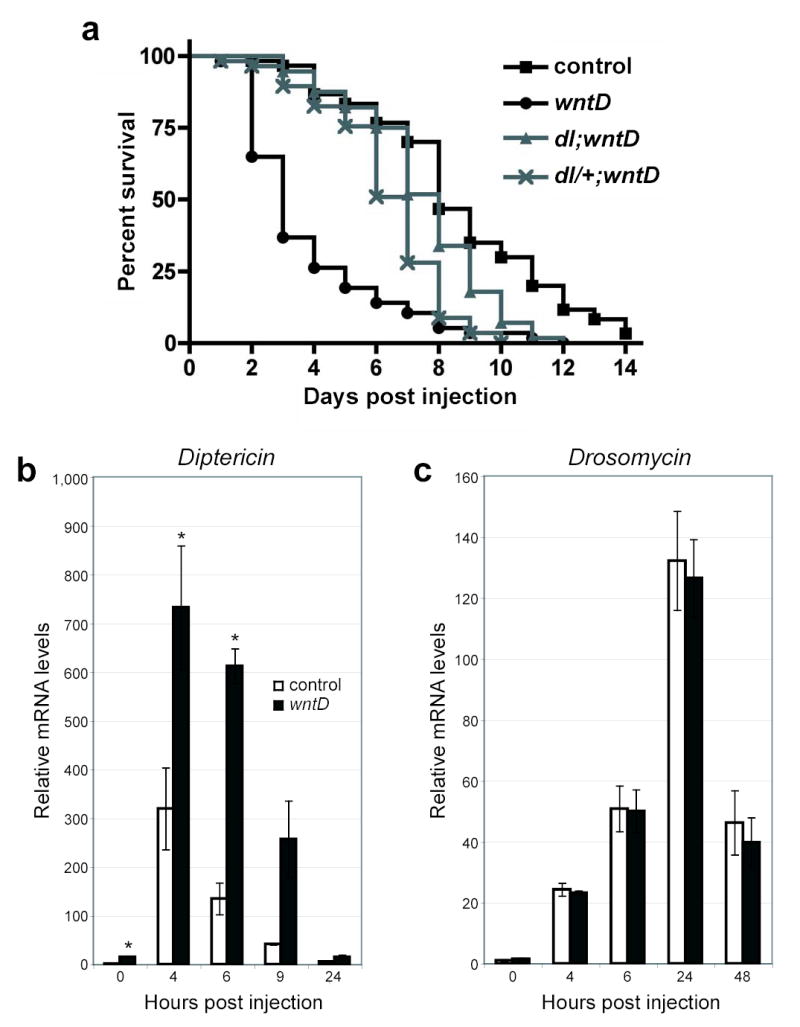

To investigate the role of WntD following septic injury, wntD and control flies were injected with a dilute culture of the gram-positive bacterium Micrococcus luteus, and the induction of antimicrobial peptide (AMP) transcripts were monitored over time using quantitative RT-PCR (fig 4b,c). We observed that some, but not all, AMPs showed aberrant expression in wntD mutants. diptericin was most severely affected, with wntD flies displaying dramatically elevated basal levels of expression (approximately 15-fold), and significantly higher mRNA levels following infection (fig 4b). In contrast, drosomycin mRNA levels were not significantly different from controls in either uninfected or infected wntD mutants. A third AMP, defensin, showed an intermediate pattern of expression, with elevated mRNA levels in wntD mutants at some time points (data not shown).

Figure 4.

wntD mutants show an aberrant response to microbial infection. a, One week old adult yw (squares, n=60), yw; wntDKO1 (circles, n=57), yw; dl1/dl4; wntDKO1 (gray triangles, n=56), and yw; dl4/+; wntDKO1 (gray crosses, n=57) were injected with a dilute culture of Listeria monocytogenes, and survival was monitored. Log rank tests indicate that wntD mutant curve is significantly different from the other three, with p<0.0001. b,c, Real-time PCR was used to monitor diptericin (b) and drosomycin (c) mRNA levels in yw (white bars) and yw; wntDKO1 (gray bars) adults following injection with Micrococcus luteus. Results are means and s.e.m. Asterisks (*) denote significance level of p<0.05.

These results pose an apparent paradox, as previous experiments have characterized diptericin as a target of IMD-Relish, and drosomycin as a target of Toll signaling15,23. Drosomycin expression is reported to be primarily regulated by Dif in adult flies, and appears to be unaffected by increased Dorsal activity16. Thus, our results for Drosomycin are consistent with past work. The diptericin result initially appears puzzling, but existing data demonstrate that the signal transduction pathways regulating immunity are not as specific as initially described. For example, Relish is required for diptericin induction in response to infections in vivo, but constitutive activation of Toll signaling results in elevated levels of diptericin in adult flies19. Furthermore, Dorsal is sufficient to activate the diptericin promoter in vitro24. The simplest explanation for these observations is that diptericin transcription can be induced by Toll-Dorsal signaling. Taken together, these data support a model in which WntD signaling specifically represses Toll-Dorsal, and not –Dif signaling.

Given a role for WntD in the regulation of antimicrobial gene transcription, we sought to determine whether wntD mutants are immunocompromised. To test this, wntD and control adults were infected with the gram positive and lethal pathogen Listeria monocytogenes25. In response to infection, wntD mutants exhibited significantly higher levels of mortality when compared to parental lines (fig 4a). Importantly, this phenotype was suppressed by the introduction of dorsal mutations (fig 4a), with close to full suppression in the absence of both copies of dorsal and partial suppression in flies heterozygous for a dorsal mutation. These genetic interactions are consistent with our assertion that WntD specifically regulates Dorsal, and not other mediators of immunity. Recent reports have demonstrated that a fly’s response to bacterial challenge includes factors that are damaging to the host26, and that increased Toll signaling can render flies more susceptible to viral infection27. We therefore propose that it is the deleterious hyper-activation of specific Dorsal target genes that is responsible for the increased mortality seen in wntD mutants. Furthermore, the susceptibility of wntD mutants to a lethal infection suggests a reason for the positive selection of wntD during evolution; immune responses have a cost, and their appropriate downregulation would be expected to provide flies with a selective advantage. While wntD flies appear healthy in a lab environment, it is easy to imagine that under the more stressful, and septic, conditions in the wild, flies lacking wntD would suffer the perils of a hyperactive immune system.

We have presented evidence that WntD, a Wnt family member, produces a signal that blocks the nuclear translocation of Dorsal. Furthermore, WntD is a target of Toll-Dorsal signaling, and creates a negative feedback loop to repress Dorsal activation. We have shown that wntD is not required for viability under lab conditions, but that wntD mutants show defects in embryonic Dorsal regulation, and the adult innate immune system. As the WntD signal in the embryo is not mediated by Armadillo, we suppose that the immune function of WntD is also Armadillo-independent, although Zettervall et al. have observed immune defects in flies expressing a dominant-negative form of the Aramdillo partner DTCF28. Further characterization of signaling events bridging WntD and Dorsal could yield valuable insight into the regulation of the therapeutically important NF-κB family of proteins.

Methods

Drosophila stocks.

Flies carrying a P[UASp-wntD] were generated using standard techniques. Other transgenic flies used were: P[nos-Gal4:VP16]29.

Immunostaining and in situ hybridization.

All in situ hybridizations were performed using standard procedures, with the exception that Proteinase K treatment was omitted. All immunostainings and cuticle preparations were performed using standard procedures. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: mouse anti-Dorsal (Developmental studies hybridoma bank; 1:10), rabbit anti-Twist (a gift from Siegfried Roth; 1:5000), rabbit anti-WntD (1:500). Photos were taken using a Zeiss Axiocam camera, images were processed with Adobe Photoshop, and figures were prepared using Adobe Illustrator.

Western and Southern blots.

Western blot for Dorsal protein was performed as previously described10. Lysates were prepared in TNT buffer (150mM NaCl, 50mM Tris-Hcl, 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.5). In order to detect WntD in embryonic lysates, a collection of 0-3 hour embryos was lysed in TNT buffer, and incubated overnight with 20mL Blue Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences). The beads were washed, and exposed to sample buffer (15mM Tris-HCl, 2.5% Glycerol, 5% SDS, 1% 2-β-mercaptoethanol, 0.006% bromophenol blue) prior to gel loading. Western Blot was performed using standard techniques with rabbit anti-WntD antibody (1:1000). Southern Blots were performed using standard techniques. wntD radio-labeled probe was generated to full length wntD cDNA using Rediprime II kit (Amersham).

Generation of anti-WntD antibodies.

See supplementary information.

Generation of wntD knockout.

See supplementary information.

Bacterial injections and Quantitative RT-PCR.

All injections were done using male flies aged one week post eclosion. A culture of Listeria monocytogenes was diluted to an OD(600) of 0.1, and a 25nL volume was injected abdominally using a pulled glass needle as previously described30. Groups of 20 flies of each genotype were injected in an alternating manner to control for variability over time. Flies were maintained on nonyeasted, standard dextrose medium at 25oC, 65% relative humidity, and survival was monitored daily. Micrococcus luteus was injected as described for L. monocytogenes. RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described30,with the exception that 6 flies were used per sample.

Supplementary Methods.

Generation of wntD knockout.

The “ends-out” targeting scheme was a modified version of that described previously1. The donor vector was constructed using pP[EndsOut] (a gift from Jeff Sekelsky) in three steps: (1) A 3kb genomic fragment including the 5’ portion of wntD was amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using the oligos: 5’- CCGCTCGAGGGGTGCCTCTAAGAGTTTGG-3’ and 5’-ACATGCATGCAGATCACTGGAACAGGAATGC-3’. The product was digested with Xho-I and Sph-I, and cloned into the Xho-I, Sph-I sites of pP[EndsOut]. (2) pBS-70W (Jeff Sekelsky) was digested with Sph-I and Kpn-I to yield an hsp70-white fragment which was cloned into the Sph-I, Kpn-I sites of the plasmid made in step 1. (3) A 3kb genomic fragment including the 3’ portion of wntD was amplified using the oligos: 5’- CGGGGTACCCGTCGATTGTGACCGATG-3’ and 5’-CGGGGTACCTTTTGCAAACGTGACCTCCT-3’. The product was digested with Kpn-I, and cloned into the Kpn-I site of the vector made in step 2. Seven fly lines carrying independent insertions of the donor construct were generated using standard procedures. Virgin females heterozygous for each donor insertion were crossed to yw; p[ry, 70FLP]11 p[70I-SceI, v+]2B Sco/S2 Cyo males2, and the resulting larvae were heatshocked for 1 hr at 37C 0-3 days AEL. The resulting unbalanced females were mated in groups of 4 to yw; p[ry, 70FLP]11 p[70I-SceI, v+]2B Sco/S2 Cyo males. The progeny from this cross were heat-shocked at 0-3 days AEL, and 700 vials were screened for red eyes upon eclosion. Non-mosaic, unbalanced flies were saved as FLP-insensitive integrations, and non-mosaic Cyo flies were subjected to a second cross to yw; p[ry, 70FLP]11 p[70I-SceI, v+]2B Sco/S2 Cyo. Lines producing non-mosaic progeny were also saved as FLP-insensitive integrations. In total, 13 FLP-insensitive integrations were found that mapped to the 3rd chromosome. Southern Blot analysis revealed that 2 were homologous targeting events, each derived from a different donor line. wntDKO1 and wntDKO2 were backcrossed to the yw parental line for 5 generations through the female germline to allow for meiotic recombination with parental genome.

Generation of anti-wntD antibodies.

wntD protein was purified as described previously3. Highly concentrated wntD included wntD precipitate, which was collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 4.5M Urea to a concentration of 1.4 mg/mL. Concentrated wntD was injected into a Rabbit using standard procedures (Josman Labs).

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeff Brown for preparing WntD protein for antibody production; Chi-Hwa Wu and Kathy Xu for preliminary experiments with wntD; Matt Fish for p-element transformations; Jeff Sekelsky and Kent Golic for fly strains and vectors used in gene targeting; Siegfried Roth, Gregor Zimmermann, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies; Alana O’Reilly and the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks; and Catriona Logan and Amanda Mikels for critical reading of the manuscript. MDG was supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute predoctoral fellowship and a Stanford Graduate Fellowship. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Correspondence to: Roel Nusse. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to R.N. ( rnusse@stanford.edu)

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beutler B. Inferences, questions and possibilities in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature. 2004;430:257–63. doi: 10.1038/nature02761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemaitre B. The road to Toll. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:521–7. doi: 10.1038/nri1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rushlow CA, Han K, Manley JL, Levine M. The graded distribution of the dorsal morphogen is initiated by selective nuclear transport in Drosophila. Cell. 1989;59:1165–77. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90772-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morisato D, Anderson KV. The spatzle gene encodes a component of the extracellular signaling pathway establishing the dorsal-ventral pattern of the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1994;76:677–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belvin MP, Jin Y, Anderson KV. Cactus protein degradation mediates Drosophila dorsal-ventral signaling. Genes Dev. 1995;9:783–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stathopoulos A, Van Drenth M, Erives A, Markstein M, Levine M. Whole-genome analysis of dorsal-ventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 2002;111:687–701. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llimargas M, Lawrence PA. Seven Wnt homologues in Drosophila: a case study of the developing tracheae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14487–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251304398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganguly, A., Jiang, J. & Ip, Y. T. Drosophila WntD is a target and an inhibitor of the Dorsal/Twist/Snail network in the gastrulating embryo. Development (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gillespie SK, Wasserman SA. Dorsal, a Drosophila Rel-like protein, is phosphorylated upon activation of the transmembrane protein Toll. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3559–68. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drier EA, Govind S, Steward R. Cactus-independent regulation of Dorsal nuclear import by the ventral signal. Curr Biol. 2000;10:23–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)00267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamada F, et al. Negative regulation of Wingless signaling by D-axin, a Drosophila homolog of axin. Science. 1999;283:1739–42. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rusch J, Levine M. Regulation of the dorsal morphogen by the Toll and torso signaling pathways: a receptor tyrosine kinase selectively masks transcriptional repression. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1247–57. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–83. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng X, Khanuja BS, Ip YT. Toll receptor-mediated Drosophila immune response requires Dif, an NF-kappaB factor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:792–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choe KM, Werner T, Stoven S, Hultmark D, Anderson KV. Requirement for a peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP) in Relish activation and antibacterial immune responses in Drosophila. Science. 2002;296:359–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1070216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedengren M, et al. Relish, a central factor in the control of humoral but not cellular immunity in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 1999;4:827–37. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Gregorio E, Spellman PT, Tzou P, Rubin GM, Lemaitre B. The Toll and Imd pathways are the major regulators of the immune response in Drosophila. Embo J. 2002;21:2568–79. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green C, et al. The necrotic gene in Drosophila corresponds to one of a cluster of three serpin transcripts mapping at 43A1.2. Genetics. 2000;156:1117–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.3.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemaitre B, et al. Functional analysis and regulation of nuclear import of dorsal during the immune response in Drosophila. Embo J. 1995;14:536–45. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bettencourt R, Asha H, Dearolf C, Ip YT. Hemolymph-dependent and - independent responses in Drosophila immune tissue. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:849–63. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemaitre B, et al. A recessive mutation, immune deficiency (imd), defines two distinct control pathways in the Drosophila host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9465–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross I, Georgel P, Kappler C, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. Drosophila immunity: a comparative analysis of the Rel proteins dorsal and Dif in the induction of the genes encoding diptericin and cecropin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1238–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.7.1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansfield BE, Dionne MS, Schneider DS, Freitag NE. Exploration of host-pathogen interactions using Listeria monocytogenes and Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:901–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt SM, et al. Secreted Bacterial Effectors and Host-Produced Eiger/TNF Drive Death in aSalmonella-Infected Fruit Fly. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zambon RA, Nandakumar M, Vakharia VN, Wu LP. The Toll pathway is important for an antiviral response in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7257–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409181102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zettervall CJ, et al. A directed screen for genes involved in Drosophila blood cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14192–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403789101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rorth P. Gal4 in the Drosophila female germline. Mech Dev. 1998;78:113–8. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dionne MS, Ghori N, Schneider DS. Drosophila melanogaster is a genetically tractable model host for Mycobacterium marinum. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3540–50. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3540-3550.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Gong WJ, Golic KG. Ends-out, or replacement, gene targeting in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2556–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535280100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rong YS, Golic KG. A targeted gene knockout in Drosophila. Genetics. 2001;157:1307–12. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willert K, et al. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423:448–52. doi: 10.1038/nature01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]