Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to explore the potential role of Nrf2 as a biomarker in asthma and its associations with hypoxia, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis-related indicators in a cross-sectional study.

Patients and Methods

This study involved the collection of peripheral blood samples from participants to isolate serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and other assay kits was performed to quantify the levels of Nrf2, HIF-1α, SOD, and MDA in PBMCs, alongside the activities of SOD and GSH-Px, and serum concentrations of IL-4 and IL-13. Quantitative Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to assess the expression levels of GPX4, NCOA4, SCL7A11, and HMGB1 in PBMCs. Clinical data were collected and analyzed statistically. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to assess the diagnostic performance of these indicators.

Results

Compared with the control group, asthma patients showed significantly lower levels of Nrf2 and SOD in PBMCs, as well as reduced expression of GPX4, SCL7A11, and NCOA4 (P < 0.05). In contrast, levels of HIF-1α and MDA, as well as the expression of HMGB1, were significantly elevated in the asthma group (P < 0.05). Correlation analysis indicated that Nrf2, HIF-1α, and MDA levels in PBMCs were associated with certain clinical indicators in asthma patients. ROC curve analysis further demonstrated that these indicators exhibited a certain diagnostic performance for asthma and severe asthma. Additionally, in asthma patients, Nrf2 expression in PBMCs was negatively correlated with HIF-1α levels and eosinophil counts, but positively correlated with SOD and GPX4 levels.

Conclusion

The interplay between hypoxia, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis may be involved in asthma pathogenesis. Based on the findings, Nrf2 may have potential as a biomarker for asthma. However, given the study’s limitations, further research is needed to confirm these associations and fully understand the role of Nrf2 in asthma diagnosis and progression.

Keywords: asthma, Nrf2, hypoxia, oxidative stress, ferroptosis

Introduction

Asthma affects approximately 300 million individuals globally, with its prevalence and mortality rates rising annually.1 Elucidating the underlying mechanisms of asthma and implementing early intervention strategies are essential for improving its prevention and management.

The pathogenesis of asthma is highly complex and not yet fully understood, with hypoxia being one of its key characteristics.2 Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) acts as a critical regulator of the hypoxic response and is extensively involved in inflammation and immune regulation.3 Hypoxia modulates the stability and activation of HIF-1α through the regulation of prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) and factor inhibiting HIF-1 (FIH).4 Studies have shown that HIF-1α expression is elevated in the smooth muscle cells and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of asthma patients,5 and it is closely associated with airway inflammatory cell infiltration, airway hyperresponsiveness, and airway remodeling.6–8

The imbalance between the endogenous antioxidant defense system and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is also closely associated with the pathogenesis of asthma.9 Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a key regulator of the cellular oxidative stress response, translocate from the nucleus to the cytoplasm under oxidative stress. It reduces ROS production by regulating antioxidant genes such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), thereby protecting cells from oxidative damage and apoptosis.10 Studies on Nrf2-knockout mice have demonstrated that the downregulation of Nrf2 function in asthma leads to increased inflammatory cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, excessive airway mucus secretion, and heightened airway resistance, which aggravate asthma symptoms.11 Activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway can effectively protect lung tissue from oxidative stress damage by upregulating the expression of antioxidant genes, limiting eosinophilia, excessive mucus production, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), and the elevation of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 (Interleukin 4) and IL-13 (Interleukin 13), thereby mitigating the severity of asthma.12

Ferroptosis is a form of oxidative stress-dependent cell death associated with iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation. The widespread increase in oxidative stress promotes iron-dependent accumulation of specific ROS and lipid peroxidation, leading to cellular and tissue damage and ultimately triggering ferroptosis.13 During ferroptosis, the release of immunogenic molecules such as high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) further promotes the release of inflammatory cytokines by activating Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and its downstream signaling pathways.14 Additionally, oxidative stress products on the surface of ferroptotic cells, as well as released interferons and tumor necrosis factors, can induce macrophage polarization, exacerbating inflammatory responses. These processes collectively contribute to the characteristic pathological changes observed in asthma.15,16

The SOD and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) are critical endogenous antioxidants that effectively mitigate oxidative stress-induced damage.9 Malondialdehyde (MDA), a metabolic product of ROS, serves as a marker of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, reflecting the extent of these processes within the body.17 Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), known for its unique ability to eliminate membrane lipid peroxides, is considered a specific marker of ferroptosis. Genetic or pharmacological suppression of GPX4 expression or activity reduces the capacity to clear lipid peroxides, thereby promoting ferroptosis.18,19 Nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) is a key indicator of iron metabolism, while SLC7A11 plays a critical role in maintaining intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels, these markers collectively reflect ferroptosis levels from the perspectives of iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation.13 HMGB1, a mediator released during ferroptosis, can promote inflammation by enhancing cytokine release and increasing immune cell activity.14 Thus, monitoring these indicators provides an effective means to assess the levels of hypoxia, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis in asthma patients.

Existing studies suggest that under oxidative stress conditions, downregulation of Nrf2 can promote ROS production and increase PHD instability, leading to the transcription and accumulation of HIF-1α. In turn, the overexpression of HIF-1α can further elevate ROS levels, exacerbating oxidative stress.20,21 Moreover, activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway has been shown to reduce ROS and lipid peroxide levels, alleviate oxidative stress, and mitigate ferroptosis-induced cell damage, potentially through the upregulation of SOD and GPX4 expression.22 Therefore, Nrf2 is likely a critical regulatory factor in the interplay between hypoxia, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis. Its precise regulation holds promise for improving asthma severity. However, studies exploring the interactions among these processes in patients with acute asthma exacerbations have yet to be reported.

Due to their central role in immune regulation and vulnerability to oxidative stress, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) provide a practical and informative source for assessing systemic inflammation in asthma.23 This study aims to explore the potential role of Nrf2 in asthma by examining its expression in PBMCs and its associations with hypoxia, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis-related processes, with the goal of providing preliminary insights into its clinical relevance in a cross-sectional context.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2021 to September 2023. Patients diagnosed with acute exacerbation of asthma who met the inclusion criteria were selected from the outpatient and inpatient departments of the Respiratory Medicine Department at the Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (approval number: 2022YX079) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion in the study.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients aged 18–60 years who meet the diagnostic criteria for asthma, with a confirmed diagnosis of allergic asthma.24

Patients who have not received any treatments, including corticosteroids, prior to undergoing laboratory tests and biological sample collection.

Healthy individuals aged 18–60 years who underwent routine physical examinations at our hospital during the same period and had no history of respiratory diseases or other systemic diseases, selected as the control group.

Exclusion Criteria

Individuals with other concomitant respiratory diseases, including but not limited to: Significant bronchiectasis, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Lung cancer, Interstitial lung disease, Active pulmonary tuberculosis.

Individuals with severe cardiac disease, major organ failure, or any other conditions that may interfere with the study outcomes.

Patients who received treatment, including oxygen therapy and glucocorticoids, before laboratory tests and biological sample collection.

Patients with any other conditions that may affect the results, such as those undergoing recent systemic treatments or those with uncontrolled comorbidities.

Severity Grading of Acute Asthma Exacerbation

Patients with acute asthma exacerbation were classified into mild and severe groups according to the Severity Grading of Acute Asthma Exacerbation.25 Specifically, cases graded as mild or moderate were grouped under “mild”, while those graded as severe or critical were classified as “severe”.

Research Methodology

All clinical data were obtained from electronic medical records and extracted by two independent researchers using a standardized data collection form. Complete blood count data were collected for all study participants, along with blood gas values (measured using the ABL800 FLEX blood gas analyzer, Radiometer, Denmark), pulmonary function parameters (assessed with the Master Screen spirometer), and allergen test results (obtained using the Redu automatic protein blot analyzer). The recorded parameters included eosinophils (EOS) count, partial pressure of oxygen (pO2), percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁%pred), and forced expiratory volume in one second /forced vital capacity (FEV₁/FVC) ratio.

Chemicals and Solvents Purchasing

Lymphocyte separation medium, PBS buffer, red blood cell lysis buffer, and other reagents were purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. and MP Biomedicals. All primers were obtained from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. All assay kits were purchased from Jiangsu Meimian Industrial Co., Ltd. and Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute. qRT-PCR related reagents were provided by Mei5 Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and Takara.

Blood Sample Collection and Analysis of Biomarker Activity and Concentrations

Fasting blood samples were collected from all study participants. PBMCs and serum were isolated using density gradient centrifugation.

The concentrations of HIF-1α, Nrf2, SOD, and MDA in PBMCs, as well as IL-4 and interleukin-13 (IL-13) in serum, were measured using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SOD and GSH-Px activity were measured using the SOD Activity Assay Kit and GSH-Px Activity Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Tissue RNA was obtained from the PBMCs of the two groups using the kit method according to the specification operating process of the manufacturer and the Trizol method was used. The concentration and purity of the presented RNA samples were checked by UV spectrophotometer. Subsequently, cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription, and 2μL of the transcript product was extracted for PCR reaction. The reaction conditions were strictly controlled according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, the fluorescent expression of ACTB was measured as the reference to quantity the expression of different markers.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0 and GraphPad Prism 9. A normality test was performed on numerical variables. For comparisons between two groups, a T-test was applied if the data followed a normal distribution, and a non-parametric test was used for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were presented as frequency (percentage), and the chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were applied for unordered categorical variables. Correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between continuous variables using Pearson’s or Spearman correlation coefficients, depending on the normality of the data. ROC curve analysis was performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the biomarkers. A p-value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics, IL-4, IL-13 Levels, and EOS Counts Among Study Participants

A total of 30 asthma patients and 20 healthy controls were included in the study. Among the 30 asthma patients, 17 had mild exacerbations and 13 had severe exacerbations. There were no significant differences in demographics and clinical characteristics among the groups included in this study (Table 1). The asthma-related clinical data are as follows: FEV1%pred (%) was 69.68 (11.59), FEV1/FVC (%) was 75 (±25.08), pO2 was 68.8 (±12.8) mmHg, and IgE was 150.05 (±140.05) IU/mL (Table 1). The EOS counts in the two groups were 0.39 ± 0.22 × 109/L and 0.04 ± 0.02 × 109/L, respectively, The IL-4 levels in the two groups were 307.2 ± 72.75 ng/L and 225.0 ± 34.35 ng/L, respectively, while the IL-13 levels were 26.84 ± 7.5 ng/L and 11.6 ± 4.32 ng/L, respectively. Serum IL-4 and IL-13 levels, as well as EOS counts, were significantly elevated in the asthma group (Figure 1A–C).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Variable | Asthma Patients (n=30) | Healthy Subjects (n=20) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, (years) | 35.83±9.75 | 30.40±8.31 | 0.655 |

| Sex (male) | 12(40%) | 9(45%) | 0.475 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.31(6.65) | 22.22(6.41) | 0.457 |

| Smoke | 17(56.7%) | 8(40%) | 0.387 |

| History of COVID-19 infection | 25(83.3%) | 18(90%) | 0.687 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 5.56(1.60) | 5.30(1.62) | 0.486 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 127.00(22.00) | 126.00(30.00) | 0.286 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 196.50(91.50) | 228.5(158.00) | 0.229 |

| ALT (U/L) | 20.05(18.8) | 25.45(24.4) | 0.055 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 62.83(30.33) | 64.5(13.4) | 0.095 |

| FEV1%pred (%) | 69.68(11.59) | - | - |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 75(25.08) | - | - |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 68.8(12.8) | - | - |

| IgE (IU/mL) | 150.05(140.05) | - | - |

Notes: Quantitative variables are shown as Median (Interquartile Range) and categorical variables are shown as n (%).

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; Kg/m2, kilogram per square meter; WBC, leukocyte; ALT, Alanine transaminase; Cr, Creatinine; FEV1%pred, Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second percentage predicted; FEV1/FVC, Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second to Forced Vital Capacity ratio; pO2, Partial pressure of oxygen; IgE, Immunoglobulin E.

Figure 1.

Serum Levels of IL-4, IL-13, and Peripheral Blood EOS Counts Between Two Groups. Peripheral blood EOS counts between two groups (A). Expression of IL-4 and IL-13 in two group patients (B and C). Symbols indicate statistical significance: ****p < 0.0001, ns indicates no statistically significant difference.

Comparison of Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, and Ferroptosis Indicators Among Study Participants

The SOD activity levels were 18.31 ± 4.72 U/mgprot and 19.27 ± 1.26 U/mgprot for the asthma and control groups, while GSH-Px activity levels were 196.38 ± 34.97 U/mgprot and 199.87 ± 29.98 U/mgprot, respectively (Figure 2A and B). The levels of HIF-1α in PBMCs were 384.24 ± 58.35 pg/mL in the asthma group and 331.64 ± 59.73 pg/mL in the control group. MDA concentrations were 4.59 ± 1.02 nmol/mL for asthma patients and 2.90 ± 0.39 nmol/mL for controls. SOD levels were 109.0 ± 8.8 pg/mL in the asthma group, compared to 125.70 ± 7.71 pg/mL in the control group. Lastly, Nrf2 levels were measured at 104.33 ± 10.31 ng/L in asthma patients and 121.77 ± 12.55 ng/L in controls (Figure 2C–F).

Figure 2.

Comparison of Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, and Ferroptosis-Related Indicators Between Two Groups. SOD and GSH-Px activity in PBMCs of asthma patients compared to healthy controls (A and B). Levels of HIF-1α, MDA, SOD and Nrf2 in PBMCs of asthma patients compared to healthy controls (C–F). Symbols indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. ns indicates no statistically significant difference.

In asthma patients, there were no significant differences in PBMC SOD and GSH-Px activity compared to the control group (Figure 2A and B). However, the levels of HIF-1α and MDA, as well as the relative expression of HMGB1, were significantly elevated (Figures 2C and D, 3A). In contrast, Nrf2 and SOD levels, as well as the relative expression of GPX4, SLC7A11 and NCOA4, were significantly lower in the asthma group compared to the control group (Figures 2E and F, 3B–D).

Figure 3.

Expression levels of HMGB1, GPX4, SCL7A11, NCOA4 in PBMCs of asthma patients compared to healthy controls (A–D). Symbols indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. ns indicates no statistically significant difference.

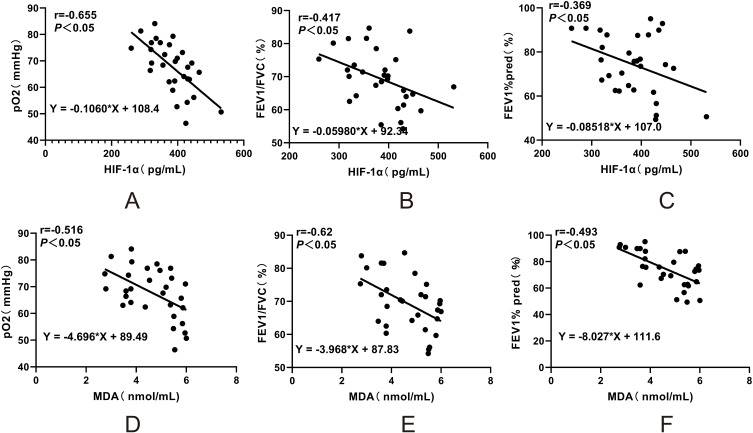

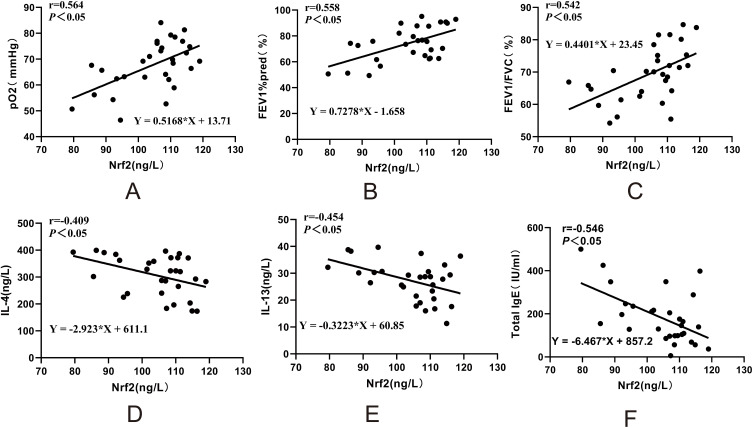

Correlation Analysis of HIF-1α, MDA, and Nrf2 with Clinical Indicators in Asthma Patients, and Correlation Between EOS Counts and Related Indicators

In asthma patients, HIF-1α and MDA levels in PBMCs were negatively correlated with lung function parameters, including arterial blood gas pO2, FEV1/FVC ratio, and FEV1%pred. Specifically, HIF-1α levels showed a significant negative correlation with pO2 (r = −0.655, P < 0.05), FEV1/FVC ratio (r = −0.417, P < 0.05), and FEV1%pred (r = −0.369, P < 0.05). Similarly, MDA levels were negatively correlated with pO2 (r = −0.516, P < 0.05), FEV1/FVC ratio (r = −0.62, P < 0.05), and FEV1%pred (r = −0.493, P < 0.05) (Figure 4A–F). In contrast, Nrf2 levels in asthma patients were positively correlated with pO2 (r = 0.564, P < 0.05), FEV1%pred (r = 0.558, P < 0.05), and FEV1/FVC ratio (r = 0.542, P < 0.05) (Figure 5A–C). Additionally, Nrf2 levels were negatively correlated with serum IL-4 (r = −0.409, P < 0.05), IL-13 (r = −0.454, P < 0.05), and total IgE (r = −0.546, P < 0.05) levels (Figure 5D–F).

Figure 4.

Correlation Analysis of Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, Ferroptosis-Related Indicators with Clinical Parameters in Asthmatic Patients. Correlation analysis of HIF-1α levels in PBMCs of asthma patients with clinical parameters (A–C). Correlation analysis of MDA levels in PBMCs of asthma patients with clinical parameters (D–F).

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis of Nrf2 levels in PBMCs of asthma patients with clinical parameters (A–F).

Additionally, EOS counts were not only correlated with clinical indicators but also showed significant correlations with HIF-1α, Nrf2, SOD, and MDA levels, with the strongest correlation observed between EOS counts and Nrf2 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation Analysis Between Peripheral Blood EOS Count and Other Indicators in Asthma Patients

| Variable | EOS Counts (*109/L) | |

|---|---|---|

| r | P | |

| FEV1%pred (%) | −0.458 | 0.011 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | −0.457 | 0.011 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | −0.573 | 0.001 |

| IgE (IU/mL) | 0.477 | 0.008 |

| Nrf2 (ng/L) | −0.701 | 0.001 |

| HIF-1α (pg/mL) | 0.653 | 0.001 |

| SOD (pg/mL) | −0.423 | 0.020 |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 0.634 | 0.001 |

| IL-4 (ng/L) | 0.469 | 0.009 |

| IL-13 (ng/L) | 0.409 | 0.025 |

Abbreviations: FEV1%pred, Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second percentage predicted; FEV1/FVC, Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second to Forced Vital Capacity ratio; pO2, Partial pressure of oxygen; IgE, Immunoglobulin E; Nrf2, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HIF-1α, Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; MDA, Malondialdehyde; IL-4, Interleukin 4; IL-13, Interleukin 13.

Diagnostic Value of Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, and Ferroptosis-Related Indicators for Asthma and Its Severity

EOS, IL-4, IL-13, HIF-1α, Nrf2, MDA, SOD, and GPX4 showed different levels of diagnostic value for asthma prediction (Figure 6A–H), as well as for predicting severe asthma (Figure 6I–P).

Figure 6.

Diagnostic accuracy of Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, and Ferroptosis-Related Indicators in Diagnosing Asthma in the Healthy Population and Severe Asthma in Asthmatic Patients. ROC curves show the diagnostic value of EOS, IL-4, IL-13, HIF-1α, Nrf2, MDA, SOD and GPX4 in asthma patients and healthy population (A–H). ROC curves show the diagnostic value of EOS, IL-4, IL-13, HIF-1α, Nrf2, MDA, SOD and GPX4 in mild asthma and severe asthma (I–P).

Among these, EOS, IL-13, MDA, and SOD had an area under the ROC curve (AUC) exceeding 0.9 for asthma diagnosis (Figure 6A, C, F, G), with IL-13 showing the highest AUC (Figure 6C), SOD demonstrating the highest sensitivity (Table 3), and MDA exhibiting the highest specificity (Table 3). Nrf2 had an AUC of 0.876, with the optimal cutoff value yielding the highest positive likelihood ratio (PLR) of 22.5 (Figure 6E and Table 3).

Table 3.

Diagnostic Performance of Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, and Ferroptosis-Related Indicators in Diagnosing Asthma Patients in a Healthy Population

| Variable | Cut-off Value | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PLR | NLR | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOS (*10^9/L) | >0.075 | 0.935 | 0.867 | 0.950 | 17.333 | 0.056 | 0.963 | 0.826 |

| (0.865–1.000) | (0.745–0.988) | (0.854–1.000) | (2.533–117.702) | (0.351–0.963) | (0.892–1.034) | (0.671–0.981) | ||

| IL-4 (ng/mL) | >280.221 | 0.808 | 0.700 | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.333 | 0.913 | 0.667 |

| (0.685–0.930) | (0.536–0.864) | (0.769–1.000) | (1.841–26.614) | (0.189–0.587) | (0.798–1.028) | (0.489–0.844) | ||

| IL-13 (ng/mL) | >16.675 | 0.966 | 0.933 | 0.900 | 9.333 | 0.074 | 0.933 | 0.900 |

| (0.923–1.000) | (0.844–1.000) | (0.769–1.000) | (2.498–34.879) | (0.019–0.285) | (0.844–1.023) | (0.769–1.031) | ||

| MDA (nmol/mL) | >3.576 | 0.933 | 0.867 | 1.000 | —— | 0.133 | 1.000 | 0.833 |

| (0.861–1.000) | (0.745–0.988) | (1.000–1.000) | —— | (0.054–0.332) | (1.000–1.000) | (0.863–0.982) | ||

| HIF-1α (pg/mL) | >347.055 | 0.736 | 0.733 | 0.650 | 2.095 | 0.410 | 0.759 | 0.619 |

| (0.598–0.874) | (0.575–0.892) | (0.441–0.859) | (1.110–3.954) | (00.209–0.806) | (0.603–0.914) | (0.411–0.827) | ||

| Nrf2 (ng/mL) | <117.374 | 0.876 | 0.750 | 0.967 | 22.500 | 0.259 | 0.938 | 0.853 |

| (0.761–0.990) | (0.560–0.940 | (0.902–1.000) | (3.222–157.136) | (0.121–0.554) | (0.819–1.056) | (0.734–0.972) | ||

| SOD (pg/mL) | <114.325 | 0.933 | 1.000 | 0.800 | 5.000 | 0.000 | 0.769 | 1.000 |

| (0.863–1.000) | (1.000–1.000) | (0.657–0.943) | (2.444–10.228) | —— | (0.607–0.931) | (1.000–1.000) | ||

| GPX4 | <0.045 | 0.786 | 0.700 | 0.833 | 4.200 | 0.360 | 0.737 | 0.806 |

| (0.651–0.921) | (0.499–0.901) | (0.700–0.967) | (1.795–9.827) | (0.181–0.717) | (0.539–0.935) | (0.667–0.946) |

Abbreviations: EOS, Eosinophils; IL-4, Interleukin 4; IL-13, Interleukin 13; MDA, Malondialdehyde; HIF-1α, Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha; Nrf2, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; GPX4, Glutathione peroxidase 4; AUC, Area Under the Curve; PLR, Positive Likelihood Ratio; NLR, Negative Likelihood Ratio; PPV, Positive Predictive Value; NPV, Negative Predictive Value.

For diagnosing severe asthma, EOS had the highest diagnostic value, with an AUC of 0.935 (Figure 6I) and the highest PLR value of 17.333 (Table 4), followed by Nrf2, HIF-1α, SOD, MDA, and IL-4 (Figure 6M, L, N, O, G and Table 4). Among these, Nrf2 and HIF-1α demonstrated the highest sensitivity (Figure 6M and L, Table 4), while Nrf2 and SOD also had relatively high PLR values of 5 and 7, respectively (Table 4). IL-13 and GPX4, however, did not exhibit significant diagnostic value for severe asthma (Figure 6K and P).

Table 4.

Diagnostic Performance of Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, and Ferroptosis-Related Indicators in Diagnosing Severe Asthma Patients

| Variable | Cut-off Value | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PLR | NLR | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOS (*10^9/L) | >0.075 | 0.935 | 0.867 | 0.950 | 17.333 | 0.056 | 0.963 | 0.826 |

| (0.865–1.000) | (0.745–0.988) | (0.854–1.000) | (2.533–117.702) | (0.351–0.963) | (0.892–1.034) | (0.671–0.981) | ||

| IL-4 (ng/mL) | >360.341 | 0.765 | 0.700 | 0.850 | 4.667 | 0.353 | 0.700 | 0.850 |

| (0.565–0.965) | (0.416–0.984) | (0.694–1.000) | (1.524–14.294) | (0.135–0.926) | (0.416–0.984) | (0.694–1.006) | ||

| MDA (nmol/mL) | >5.010 | 0.850 | 0.900 | 0.750 | 3.600 | 0.133 | 0.643 | 0.938 |

| (0.717–0.993) | (0.714–1.000) | (0.560–0.940) | (1.639–7.906) | (0.020–0.871) | (0.392–0.894) | (0.819–1.056) | ||

| HIF-1α (pg/mL) | >380.157 | 0.870 | 1.000 | 0.650 | 2.857 | 0.000 | 0.588 | 1.000 |

| (0.744–0.996) | (1.000–1.000) | (0.441–0.859) | (1.572–5.192) | —— | (0.354–0.822) | (1.000–1.000) | ||

| Nrf2 (ng/mL) | <98.541 | 0.890 | 1.000 | 0.800 | 5.000 | 0.000 | 0.909 | 1.000 |

| (0.738–1.000) | (1.000–1.000) | (0.552–1.000) | (1.447–17.271) | —— | (0.789–1.029) | (1.000–1.000) | ||

| SOD (pg/mL) | <108.867 | 0.877 | 0.700 | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.333 | 0.933 | 0.600 |

| (0.755–1.000) | (0.499–0.901) | (0.714–1.000) | (1.067–45.940) | (0.165–0.672) | (0.807–1.060) | (0.352–0.848) |

Abbreviations: EOS, Eosinophils; IL-4, Interleukin 4; MDA, Malondialdehyde; HIF-1α, Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha; Nrf2, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; AUC, Area Under the Curve; PLR, Positive Likelihood Ratio; NLR, Negative Likelihood Ratio; PPV, Positive Predictive Value; NPV, Negative Predictive Value.

Correlation Analysis of HIF-1α with SOD and MDA, and the Correlation of Nrf2 with HIF-1α, GPX4, and MDA in PBMCs of Asthma Patients

In asthma patients’ PBMCs, the levels of HIF-1α were positively correlated with MDA levels (r = 0.559, P < 0.05) and negatively correlated with SOD levels (r = −0.565, P < 0.05) (Figure 7A and B). Nrf2 expression was negatively correlated with MDA (r = −0.5394, P < 0.05) and HIF-1α levels (r = −0.684, P < 0.05) (Figure 7C and D), and positively correlated with SOD (r = 0.6308, P < 0.05) and GPX4 expression (r = 0.731, P < 0.05) (Figure 7E and F).

Figure 7.

Correlation Analysis of Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, and Ferroptosis-Related Indicators. Correlation analysis of HIF-1α with MDA and SOD in PBMCs of asthma patients (A and B), and Correlation Analysis of Nrf2 with MDA, HIF-1α, SOD and GPX4 (C–F).

Discussion

This study initially assessed the inflammation levels in asthma patients and found that during the acute exacerbation phase, EOS counts and serum IL-4 and IL-13 levels were significantly elevated. Furthermore, it was observed that in the asthma group, the levels of HIF-1α and MDA, as well as the relative expression of NCOA4 and HMGB1 in PBMCs, were significantly higher, whereas the levels of Nrf2 and SOD, along with the relative expression of GPX4 and SCL7A11, were markedly lower compared to the control group. These findings suggest that asthma may be associated with hypoxia, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis.

Previous studies have demonstrated that changes in Nrf2 levels in PBMCs can reflect the state and severity of different disease stages and may serve as a potential biomarker for various diseases.26 We found that HIF-1α and MDA levels were negatively correlated with lung function and pO2, whereas Nrf2 showed a positive correlation with lung function and pO2. Additionally, Nrf2 was negatively correlated with IL-4 and IL-13 levels. Further analysis using ROC curves was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic performance of these biomarkers for asthma and severe asthma. The results demonstrated that EOS and IL-13 exhibited good diagnostic performance for asthma, but IL-13 did not show significant value for diagnosing severe asthma. Other biomarkers also displayed varying degrees of diagnostic utility. Notably, Nrf2 showed a high diagnostic value for asthma, with an area AUC of 0.876. At the optimal cutoff value, the PLR for Nrf2 was the highest at 22.5. For diagnosing severe asthma, Nrf2 and HIF-1α demonstrated the highest sensitivity, with Nrf2 and SOD also showing relatively high PLR values of 5 and 7, respectively. These findings suggest that Nrf2 may play a role in diagnosing asthma and assessing disease severity.

Exposure to NO2 in mouse models has been shown to exacerbate lung inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness, increasing oxidative stress markers such as ROS and MDA.27 Co-exposure to NO2 and high humidity further worsened asthma symptoms by elevating oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines.28 These findings underscore the significant role of oxidative stress in asthma pathogenesis and its interaction with environmental factors. Additionally, oxidative stress levels are significantly elevated under hypoxic conditions,29 and studies have demonstrated that oxidative stress can drive hypoxic responses, leading to proinflammatory effects in asthma.2 Notably, HIF-1α has been identified as a potential therapeutic target for managing oxidative stress in asthma.30 This finding highlights the intricate interplay between hypoxia and oxidative stress. We found that HIF-1α levels in PBMCs were negatively correlated with SOD levels and positively correlated with MDA levels (P < 0.05), suggesting a relationship between hypoxia and oxidative stress in asthma patients. Additionally, this study revealed a negative correlation between Nrf2 and HIF-1α expression. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the downregulation of Nrf2 in asthma patients may be associated with increased HIF-1α expression, which could potentially suppress the antioxidant function of Nrf2. This dysregulation might contribute to enhanced oxidative stress and the worsening of asthma severity. Another study have shown that Nrf2 activators can reduce HIF-1α expression by increasing PhD levels, while HIF-1α expression is restored upon Nrf2 knockout.31 However, in breast cancer, Nrf2 was shown to promote cancer cell migration by upregulating the G6PD/HIF-1α/Notch1 axis.32 Collectively, these studies highlight the complexity of the interaction between Nrf2 and HIF-1α in different diseases. It is likely that the Nrf2 signaling pathway and HIF-1α are part of a complex and interactive signaling network, with their interplay varying across pathological conditions.

Given the unique mechanism of ferroptosis, recent studies have increasingly focused on targeting specific signaling pathways to regulate oxidative stress and ferroptosis as a therapeutic strategy for asthma, Nrf2 has emerged as one of the most prominent targets.33 Athari highlighted the potential and feasibility of targeting the Nrf2 signaling pathway in asthma treatment.34 However, the relationship between Nrf2 and ferroptosis in asthma remains unclear. In this study, we found that Nrf2 levels in PBMCs of asthma patients were positively correlated with SOD and GPX4 levels, and negatively correlated with MDA levels. Based on these findings, and in addition to its interaction with HIF-1α, we propose that Nrf2 may play a role in the pathogenesis of asthma. During acute exacerbations, an imbalance in oxidative stress could be associated with the downregulation of Nrf2 expression, which might lead to decreased SOD levels and reduced GPX4 expression. This could impair antioxidant defenses, potentially contributing to the worsening of oxidative stress and ferroptosis, and influencing the progression of asthma. However, this hypothesis requires further in-depth studies for confirmation.

This study also found that a higher EOS count was associated with elevated IL-4 and IL-13 levels, as well as reduced FEV1%pred, FEV1/FVC, and pO2, indicating that increased EOS counts are correlated with airflow obstruction, decreased lung function, and poor asthma symptom control. These findings are consistent with the results of Hancox RJ and Jackson DJ.35,36 In asthma, HIF-1α, in coordination with its downstream target protein vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), promotes the infiltration of EOS and other inflammatory cells, EOS contribute to oxidative stress by producing ROS and EOS peroxidase, which reduce the production of antioxidant enzymes, leading to lung tissue damage and inflammatory injury.37 A deficiency in Nrf2 not only results in increased EOS counts but also leads to reduced expression of antioxidant genes that counteract oxidative damage.38 In this study, we found that EOS counts were positively correlated with HIF-1α levels and negatively correlated with Nrf2 levels. These results suggest that the downregulation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway is associated with increased EOS levels, which may be linked to the exacerbation of asthma severity.

In conclusion, this study preliminarily reveals the potential associations between Nrf2 and hypoxia, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis. However, further in vitro and in vivo experiments are needed to validate the exact mechanisms underlying these associations. Additionally, future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further evaluate the potential of Nrf2 as a biomarker for diagnosing asthma and assessing its severity.

Limitations

This study has some limitations, including its single-center design and relatively small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study primarily focused on correlation analyses without exploring the underlying mechanisms. Future research with larger and more diverse cohorts, as well as deeper mechanistic investigations, is needed to confirm these findings and further understand the involved pathways.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that oxidative stress, hypoxia, and ferroptosis may contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma. Nrf2 shows promise as a potential biomarker for asthma; however, due to the study’s limitations, additional research is required to validate these associations and clarify the role of Nrf2 in the diagnosis and progression of asthma.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the efforts of all the staff, professionals, and participants in this study.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Shanxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (202203021211029).

Disclosure

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Momtazmanesh S, Moghaddam SS, Ghamari S-H.; GBD 2019 Chronic Respiratory Diseases Collaborators. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: an update from the global burden of disease study 2019. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;59:101936. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad T, Kumar M, Mabalirajan U, et al. Hypoxia response in asthma: differential modulation on inflammation and epithelial injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47(1):1–10. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0203OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Gaber T. Hypoxia/HIF modulates immune responses. Biomedicines. 2021;9(3):260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palazon A, Goldrath AW, Nizet V, Johnson RS. HIF transcription factors, inflammation, and immunity. Immunity. 2014;41(4):518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewitz C, McEachern E, Shin S, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α inhibition modulates airway hyperresponsiveness and nitric oxide levels in a BALB/c mouse model of asthma. Clin Immunol. 2017;176:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang C, Gao J, Zhu S. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α promotes proliferation of airway smooth muscle cells through miRNA-103-mediated signaling pathway under hypoxia. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2021;57(10):944–952. doi: 10.1007/s11626-021-00607-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huerta-Yepez S, Baay-Guzman GJ, Bebenek IG, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor promotes murine allergic airway inflammation and is increased in asthma and rhinitis. Allergy. 2011;66(7):909–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02594.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangasamy T, Semenza GL, Georas SN. What is hypoxia-inducible factor-1 doing in the allergic lung? Allergy. 2011;66(7):815–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michaeloudes C, Abubakar-Waziri H, Lakhdar R, et al. Molecular mechanisms of oxidative stress in asthma. Mol Aspects Med. 2022;85:101026. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2021.101026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:401–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li YJ, Kawada T, Azuma A. Nrf2 is a protective factor against oxidative stresses induced by diesel exhaust particle in allergic asthma. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:323607. doi: 10.1155/2013/323607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q, Gao Y, Ci X. Role of Nrf2 and its activators in respiratory diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:7090534. doi: 10.1155/2019/7090534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen R, Kang R, Tang D. The mechanism of HMGB1 secretion and release. Exp Mol Med. 2022;54(2):91–102. doi: 10.1038/s12276-022-00736-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Que KT, Zhang Z, et al. Iron overloaded polarizes macrophage to proinflammation phenotype through ROS/acetyl-p53 pathway. Cancer Med. 2018;7(8):4012–4022. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handa P, Thomas S, Morgan-Stevenson V, et al. Iron alters macrophage polarization status and leads to steatohepatitis and fibrogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;105(5):1015–1026. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3A0318-108R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsikas D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: analytical and biological challenges. Anal Biochem. 2017;524:13–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2016.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):88. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: death by Lipid Peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(3):165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potteti HR, Noone PM, Tamatam CR, et al. Nrf2 mediates hypoxia-inducible HIF1α activation in kidney tubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2021;320(3):F464–f74. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00501.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masson N, Singleton RS, Sekirnik R, et al. The FIH hydroxylase is a cellular peroxide sensor that modulates HIF transcriptional activity. EMBO Rep. 2012;13(3):251–257. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge MH, Tian H, Mao L, et al. Zinc attenuates ferroptosis and promotes functional recovery in contusion spinal cord injury by activating Nrf2/GPX4 defense pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27(9):1023–1040. doi: 10.1111/cns.13657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon HS, Bae YJ, Moon KA, et al. Hyperoxidized peroxiredoxins in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of asthma patients is associated with asthma severity. Life Sci. 2012;90(13–14):502–508. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkatesan P. 2023 GINA report for asthma. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(7):589. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00230-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asthma group of Chinese Throacic Society. [Guidelines for bronchial asthma prevent and management(2020 edition) Asthma group of Chinese Throacic Society]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43(12):1023–1048. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200618-00721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neilson LE, Quinn JF, Gray NE. Peripheral blood NRF2 expression as a biomarker in human health and disease. Antioxidants. 2020;10(1):28. doi: 10.3390/antiox10010028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu C, Wang F, Liu Q, et al. Effect of NO2 exposure on airway inflammation and oxidative stress in asthmatic mice. J Hazard Mater. 2023;457:131787. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu C, Liu Q, Qiao Z, et al. High humidity and NO2 co-exposure exacerbates allergic asthma by increasing oxidative stress, inflammatory and TRP protein expressions in lung tissue. Environ Pollut. 2024;353:124127. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siques P, Brito J, Pena E. Reactive oxygen species and pulmonary vasculature during hypobaric hypoxia. Front Physiol. 2018;9:865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourgonje AR, Kloska D, Grochot-Przęczek A, et al. Personalized redox medicine in inflammatory bowel diseases: an emerging role for HIF-1α and NRF2 as therapeutic targets. Redox Biol. 2023;60:102603. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Chen F, Wang S, et al. Low-dose triptolide in combination with idarubicin induces apoptosis in AML leukemic stem-like KG1a cell line by modulation of the intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4(12):e948. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang HS, Zhang ZG, Du GY, et al. Nrf2 promotes breast cancer cell migration via up-regulation of G6PD/HIF-1α/Notch1 axis. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(5):3451–3463. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan R, Lin B, Jin W, Tang L, Hu S, Cai R. NRF2, a superstar of ferroptosis. Antioxidants. 2023;12(9):1739. doi: 10.3390/antiox12091739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Athari SS. Targeting cell signaling in allergic asthma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2019;4:45. doi: 10.1038/s41392-019-0079-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hancox RJ, Pavord ID, Sears MR. Associations between blood eosinophils and decline in lung function among adults with and without asthma. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(4):1702536. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02536-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson DJ, Humbert M, Hirsch I, et al. Ability of serum IgE concentration to predict exacerbation risk and benralizumab efficacy for patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. Adv Ther. 2020;37(2):718–729. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01191-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Groot LES, Sabogal Piñeros YS, Bal SM, et al. Do eosinophils contribute to oxidative stress in mild asthma? Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49(6):929–931. doi: 10.1111/cea.13389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rangasamy T, Guo J, Mitzner WA, et al. Disruption of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to severe airway inflammation and asthma in mice. J Exp Med. 2005;202(1):47–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]