Abstract

GATA-1 is a transcription factor essential for erythroid/megakaryocytic cell differentiation. To investigate the contribution of individual domains of GATA-1 to its activity, transgenic mice expressing either an N-terminus, or an N- or C-terminal zinc finger deletion of GATA-1 (ΔNT, ΔNF or ΔCF, respectively) were generated and crossed to GATA-1 germline mutant (GATA-1.05) mice. Since the GATA-1 gene is located on the X-chromosome, male GATA-1 mutants die by embryonic day 12.5. Both ΔNF and ΔCF transgenes failed to rescue the GATA-1.05/Y pups. However, transgenic mice expressing ΔNT, but not the ΔNF protein, were able to rescue definitive hematopoiesis. In embryos, while neither the ΔCF protein nor a mutant missing both N-terminal domains (ΔNTNF) was able to support primitive erythropoiesis, the two independent ΔNT and ΔNF mutants could support primitive erythropoiesis. Thus, lineage-specific transgenic rescue of the GATA-1 mutant mouse revealed novel properties that are conferred by specific domains of GATA-1 during primitive and definitive erythropoiesis, and demonstrate that the NT and NF moieties lend complementary, but distinguishable properties to the function of GATA-1.

Keywords: domain/erythropoiesis/GATA-1/rescue/transgenic mouse

Introduction

Cell differentiation is controlled in part by cell lineage-restricted transcription factors (reviewed in Ness and Engel, 1994; Yamamoto et al., 1997). These transcription factors interact with one another and with ubiquitous transcription factors to form a regulatory network that modulates the expression of downstream target genes. For example, several erythroid lineage-restricted transcription factors have been identified, including GATA-1, GATA-2, EKLF (erythroid Krüppel-like factor), Myb and Runx1 (reviewed in Bungert and Engel, 1996; Enver and Greaves, 1998). While gene targeting loss-of-function studies have demonstrated that these transcription factors specifically affect erythroid differentiation (reviewed in Shivdasani and Orkin, 1996), the precise contribution of each factor to erythropoiesis has not yet been elucidated.

More recent studies have characterized important coactivators and corepressors that serve to transduce signals from the DNA binding by transcription factors to the basic transcriptional machinery assembled at promoters (Hebbes et al., 1988). Although coactivators and corepressors interact directly with specific motifs within transcription factors, the conventional transcriptional activation (or repression) domains of these factors do not match the coactivator interaction domains uniformly. In this regard, it is important to note that many of the early structure–function analyses of transcription factors were executed using reporter plasmid cotransfection and transactivation assays in tissue culture cells, and therefore may not represent the entire array of the more complex interactions probably occurring in vivo.

The transcription factor GATA-1 contains two zinc fingers and is expressed in erythroid cells, megakaryocytes, eosinophils and mast cells of the hematopoietic lineage, as well as in Sertoli cells of the testis (reviewed in Yamamoto et al., 1997). Hematopoietic and testis-specific transcription of the GATA-1 gene is directed by two distinct first exons/promoters, while the coding exons are common to both GATA-1 transcripts (Ito et al., 1993; Onodera et al., 1997a). In primitive erythroid cells, GATA-1 expression is under the regulatory influence of a 5′ enhancer (termed the GATA-1 hematopoietic enhancer; G1HE), whereas the expression of GATA-1 in definitive hematopoietic cells requires an element in the first intron in addition to G1HE (Onodera et al., 1997b; Nishimura et al., 2000). Reporter genes expressed under the combined regulatory influence of these two elements faithfully recapitulate endogenous GATA-1 gene expression (Takahashi et al., 2000); hence we refer to the combined transcriptional activity of these two elements as the GATA-1 locus hematopoietic regulatory domain (HRD; Motohashi et al., 2000).

To test the transcriptional authenticity of the GATA-1 HRD at the functional level, we initially generated a murine line bearing an erythroid promoter-specific ‘knock-down’ allele of the GATA-1 gene (Takahashi et al., 1997). The expression level of GATA-1 from this germline mutant allele is ∼5% that of wild type and is thus referred to as GATA-1.05 (Yamamoto et al., 1997). Since the GATA-1 gene is located on the X-chromosome, male embryos hemizygous for the mutation (GATA-1.05/Y) are defective in primitive erythropoiesis and do not survive beyond 12.5 embryonic days (E12.5). Importantly, transgenic expression of a wild-type GATA-1 cDNA under the transcriptional control of the GATA-1 HRD completely rescued male GATA-1.05 mutants (Takahashi et al., 2000). These rescued mice were fertile and showed normal hematopoietic indices, indicating that the GATA-1 HRD, when cis-linked to a wild-type GATA-1 cDNA, can override the lethality bestowed by the GATA-1.05 mutation.

At least three functional domains have been identified within the GATA-1 molecule by structure–function analyses conducted in cell culture. GATA-1 possesses a C-terminal finger (CF) and an N-terminal finger (NF) domain. The CF is required for recognition of the GATA consensus sequence and DNA binding (Yang and Evans, 1992). The CF is also important for the physical interaction with other transcription factors, such as Sp1 and PU.1 (Merika and Orkin, 1995; Rekhtman et al., 1999). The NF is required for association with the coactivator FOG1 (Tsang et al., 1998), and contributes to the specificity and stability of DNA binding to a palindromic GATA recognition sequence (Trainor et al., 1996).

The most N-terminal 80 residues confer strong transcriptional activation activity to GATA-1, as reflected in reporter gene cotransfection assays in fibroblasts (Martin and Orkin, 1990; Yang and Evans, 1992). This N-terminal (NT) domain, however, appeared to be dispensable during erythroid or megakaryocytic cell differentiation, as reported in several cell culture-based rescue experiments (Blobel et al., 1995; Visvader et al., 1995). More recently, an erythroid cell line called G1E was developed from GATA-1-null embryonic stem (ES) cells (Weiss et al., 1997). Using this novel cell line to recapture erythroid differentiation in vitro, the NT domain of GATA-1 was shown to be dispensable during erythroid cell differentiation (Weiss et al., 1997), contradicting earlier conclusions regarding the function of the NT domain. Since all NT domain analyses had been based on cell culture assays, we anticipated that in vivo analysis would resolve any discrepancies.

We set out to exploit the transgenic rescue assay of GATA-1.05 germline mutants to determine which domains of GATA-1 might be required during erythroid development. To this end, we prepared deletion mutations within GATA-1 and placed these mutant cDNAs under the transcriptional control of the GATA-1 HRD. Multiple lines of transgenic mice were generated to investigate the rescue potential of the various GATA-1 cDNA mutant transgenes in the GATA-1.05 mutant background. The results of these transgenic analyses demonstrate unequivocally that the CF moiety is indispensable for GATA-1 function. The NF is indispensable for definitive erythropoiesis, whereas primitive erythropoiesis progresses normally in its absence. When expressed several-fold more abundantly than endogenous GATA-1, the NT deletion mutant can sustain both primitive and definitive erythropoiesis, while at expression levels comparable with endogenous GATA-1, definitive erythropoiesis was severely compromised. These results suggest that the NT and NF domains are utilized differentially during primitive and definitive erythropoiesis. Thus, using the stringent criterion of transgenic rescue, this in vivo analysis of GATA-1 has indeed resolved the conflicting implications arising from studies based on cell culture and demonstrated that the three domains of GATA-1 have distinguishable functions.

Results

Expression and transactivation activity of truncated GATA-1 mutants

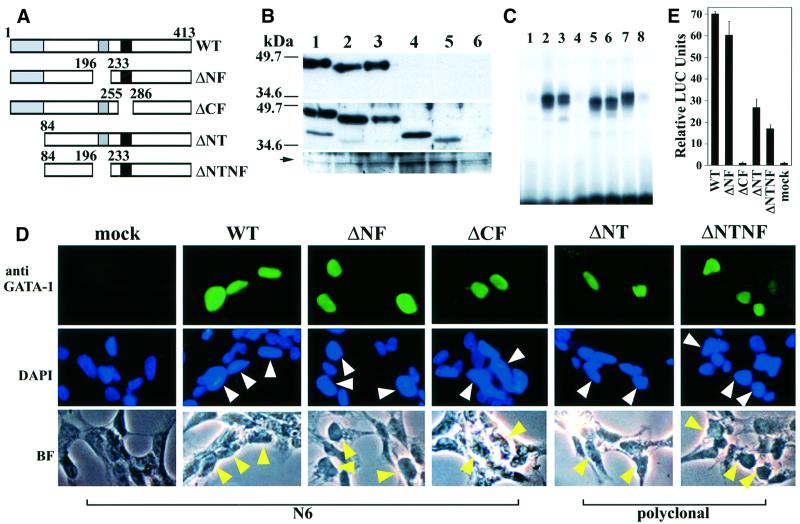

To investigate the contribution of the individual domains of GATA-1 to its overall activity, we generated transgenic mice expressing an N-terminal deletion (first 83 amino acids), an N-terminal zinc finger deletion or a C-terminal zinc finger deletion of GATA-1 (ΔNT, ΔNF or ΔCF, respectively; Figure 1A). Furthermore, an additional mutant was generated, which lacked both the N-terminus and the N-terminal zinc finger (ΔNTNF).

Fig. 1. Expression and transactivation activity of GATA-1 mutants. (A) Deletion constructs are illustrated schematically. Numbers indicate the amino acid residues. (B) Immunoblotting analyses of GATA-1 mutant proteins. 293T cells were mock transfected (lane 6) or transfected with expression plasmids driving the wild-type GATA-1 (lane 1), ΔNF (lane 2), ΔCF (lane 3), ΔNT (lane 4) or ΔNTNF (lane 5) mutant GATA-1. Lysates were then immunoreacted with the N6 monoclonal antibody (top panel), rat anti-mouse GATA-1 antiserum (middle panel) or anti-lamin B antibody (bottom panel). The positions of the size markers are shown on the left of the panels. An arrow indicates the position of the lamin B protein. (C) EMSA using nuclear extracts prepared from QT6 cells transfected with either wild-type or mutant GATA-1 expression plasmids. Lane 1, pEF-BOS vector; lanes 2, 7 and 8, wild-type GATA-1; lane 3, ΔNF; lane 4, ΔCF; lane 5, ΔNT; lane 6, ΔNTNF. Unlabeled oligonucleotide (100-fold molar excess) was added to the sample depicted in lane 8. (D) Immunocytochemical analysis of QT6 cells transfected with either wild-type or mutant GATA-1 expression plasmids. The top panels demonstrate immunofluorescence staining with the N6 antibody (WT, ΔNF and ΔCF) or the anti-GATA-1 polyclonal antibody (ΔNT and ΔNTNF). Simultaneous staining with the nuclear dye DAPI and corresponding bright-field photomicrographs are shown in the middle and bottom panels, respectively. Arrowheads indicate the cells immunoreactive with anti-GATA-1 antibodies. (E) Transactivation activity of the GATA-1 mutant proteins. GATA-1 mutant expression vectors were cotransfected into QT6 cells with a LUC reporter plasmid. LUC activity of mock transfection was set to one and relative LUC activities of other constructs are shown.

It was necessary first to verify stable accumulation of the mutant proteins in a cell line expressing minimal endogenous GATA proteins. Therefore, each GATA-1 deletion mutant was cloned into the pEF-BOS eukaryotic expression vector (Mizushima et al., 1990) and transfected into 293T or QT6 cells. To detect the expression levels of GATA-1 mutant proteins, immunoblotting analysis was performed using two types of anti-GATA-1 antibodies: a rat anti-mouse GATA-1 monoclonal antibody (N6; Ito et al., 1993) and a rat antiserum raised against mouse GATA-1. The N6 antibody detected a single protein species in cell lysates prepared from 293T cells that were transfected either with wild type, ΔNF or ΔCF mutants. However, no GATA-1-immunoreactive protein was detected in lysates prepared from 293T cells transfected with either ΔNT or ΔNTNF, indicating that the epitope for the N6 antibody resides in the NT region (Figure 1B, top panel). The polyclonal antibody reacted with all of the GATA-1 mutant proteins, including ΔNT and ΔNTNF (Figure 1B, middle panel).

To determine DNA-binding properties of these deletion mutants, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using nuclear extracts prepared from QT6 cells transfected with either wild-type or mutant GATA-1 expression vectors (Figure 1C). An oligonucleotide probe containing mouse α-globin promoter sequence (MαP) was used as a probe. MαP contains a single GATA-binding site. Except for ΔCF mutant protein (lane 4), a comparable intensity was observed for each migrated complex containing wild-type or GATA-1 deletion mutant proteins (lanes 2–7). Excess unlabeled MαP probe (lane 8 and data not shown) efficiently competed with DNA–protein complexes formed with either wild-type or mutant GATA-1 proteins. Furthermore, an oligonucleotide probe containing a mutated GATA-binding site failed to compete with the complex (data not shown), indicating that the interaction between GATA-1 and the GATA-binding site is specific.

To ensure that the GATA-1 mutant proteins can localize efficiently to the nucleus, all deletion constructs used in this study included two GATA-1 nuclear localization signals, namely the RPKKR (243–247 amino acids) and KGKKK (312–316 amino acids) motifs. QT6 cells were transfected with mutant GATA-1 expression plasmids and the subcellular localization of GATA-1 protein was examined by immunocytochemistry (Figure 1D). Cells expressing wild-type, ΔNF and ΔCF GATA-1 proteins were immunoreactive with the N6 antibody (Figure 1D, top panels for wild type, ΔNF and ΔCF). However, since the epitope for the N6 antibody resides in the N-terminus, the polyclonal GATA-1 antibody was used for detecting ΔNT and ΔNTNF proteins (Figure 1D, top panels for ΔNT and ΔNTNF). Simultaneous staining with the nuclear dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Figure 1D, middle panels) and the corresponding bright-field photomicrographs (bottom panels) clearly indicate that the wild-type and deleted GATA-1 mutants are all localized in the nucleus. Taken together, the results from immunoblotting (Figure 1B), EMSA (Figure 1C) and immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1D) show that each mutant protein accumulates normally in the nuclei of transfected cells.

To determine the importance of each domain of GATA-1 to its overall transactivation activity, a transfection assay was performed in QT6 cells in which each deletion mutant was cotransfected with pRBGP3-MαP, a reporter plasmid containing a triplicate MαP GATA site fused to the luciferase (LUC) gene (Igarashi et al., 1994). The CF domain was shown to be essential for the transcriptional activation of GATA-1, as demonstrated by the lack of LUC activity with ΔCF (Figure 1E). In contrast, the observation that the LUC activity of ΔNF was indistinguishable from that of wild-type GATA-1 showed that the NF domain does not contribute significantly, either alone or cooperatively, to the transactivation activity of GATA-1 in non-erythroid cells. Removal of the NT domain suppressed more than half of the GATA-1 transactivation activity, in accordance with prior observations (Martin and Orkin, 1990; Yang and Evans, 1992). The hypothesis that the N-terminus of GATA-1 is indeed important for transactivation was supported further by the low activity seen with the ΔNTNF double mutant.

Transgenic expression of GATA-1 mutants under the regulation of GATA-1 HRD

We previously showed that the GATA-1 HRD fragment contains information sufficient to restore the endogenous expression profile of GATA-1 in both the primitive and definitive erythroid lineages (Nishimura et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2000). Deletion mutants of GATA-1 were cloned individually downstream of the GATA-1 HRD and used for in vivo studies. The resulting mutant constructs were microinjected into the fertilized eggs. Founder mice that had incorporated the transgene into their genomic DNA were screened by PCR. The copy numbers of F1 (or subsequent generations, called Fn) progeny were between 3 and 38, as determined by Southern blotting (data not shown).

Expression of GATA-1 mutant transgenes in vivo

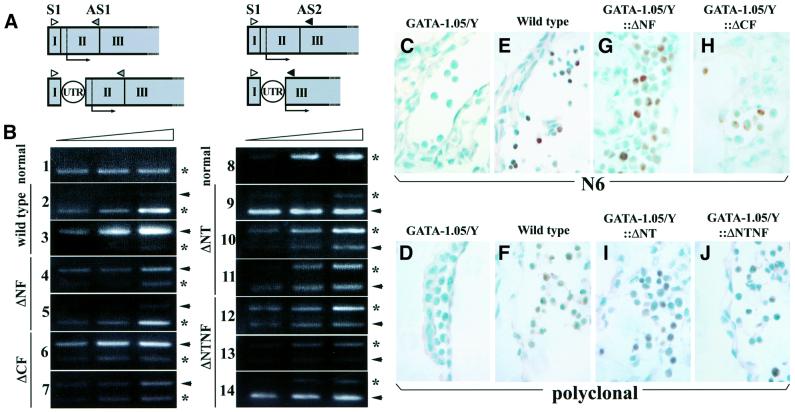

Accumulation of the GATA-1 transgene products was monitored by semiquantitative RT–PCR. We prepared cDNA templates from the spleens of Fn transgenic females and analyzed them using primers based on the sequences in exons IE and II or IE and III (Figure 2A). To dis criminate between transgene-derived and endogenous GATA-1 mRNAs in a single PCR, the transgenes were all marked by the addition of a 110 bp sequence to the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR). In the case of wild type, ΔNF and ΔCF, the size of transgene-derived PCR amplicons was 110 bp longer than that derived from the endogenous gene. In contrast, the sizes of the PCR products from the ΔNT and ΔNTNF transgenes were 139 bp smaller than that derived from the endogenous gene, since 249 bp of exons II and III (encoding the NT domain) were deleted in these mutants.

Fig. 2. GATA-1 mutant mRNA and protein in transgenic mice. (A) The positions of the primers used for RT–PCR detection of GATA-1 mRNA expression are indicated. The S1 (open triangle) and AS1 primer (gray triangle) pair was used to detect the expression of wild-type, ΔNF and ΔCF mRNAs, while the S1 and AS2 (black triangle) primer pair was used to detect the expression of the ΔNT and ΔNTNF transcripts. The circled UTR depicts the 110 bp sequence added to permit discrimination of transgene-derived mRNAs from endogenous GATA-1 mRNA. (B) The transgene-derived mRNA level was determined for each established transgenic line by semiquantitative RT–PCR. The lines without transgene (panels 1 and 8), with wild-type GATA-1 (panels 2 and 3), ΔNF (panels 4 and 5), ΔCF (panels 6 and 7), ΔNT (panels 9–11) or ΔNTNF (panels 12–14) mutant transgene were used for the analysis. Reverse transcribed cDNAs were rendered for 28, 30 and 32 cycles of amplification. Arrows indicate the migration position expected for transgene-derived GATA-1 amplicons, while asterisks indicate the position of the endogenous GATA-1 amplicon. The relative position of the transgene-derived GATA-1 bands changes in the left and right panels due to the insertion of the UTR fragment and NT deletion. (C–J) Transgenic expression of mutant GATA-1 proteins in E9.5 yolk sac erythroid cells. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using the N6 monoclonal antibody (C, E, G and H) or anti-GATA-1 antiserum (D, F, I and J). E9.5 embryos of GATA-1.05/Y (C and D), wild type (E and F), GATA-1.05/Y::ΔNF (G), GATA-1.05/Y::ΔCF (H), GATA-1.05/Y::ΔNT (I) or GATA-1.05/Y::ΔNTNF (J) genotype are shown. The nucleus was counterstained by methyl green, and the positive GATA-1 staining (brown color) is localized in the nucleus.

The transgenic animals were divided into three broad categories: high expressors accumulated several-fold more transgenic than endogenous GATA-1 mRNA, medium expressors accumulated comparable amounts of the two, while low expressors accumulated more abundant endogenous than transgene-derived GATA-1 mRNA. For example, the intensities of the amplicons shown in panels 3, 6, 9 and 14 denote high expressors, while those in panels 4, 7, 11 and 12 denote medium expressors (Figure 2B).

Examination of the hematopoietic indices of these high and/or medium transgene-expressing mice revealed no hematological or other abnormalities, except for a modest decrease in platelet count in the ΔCF lines (Table I). This suggests that hematopoietic expression of these deletion mutants does not seriously affect endogenous GATA-1 function. Only progeny from F1 or later generations were used in the breeding experiments to ensure stable transgene transmission and to exclude mosaic effects.

Table I. Hematopoietic indices of GATA-1 deletion mutant transgenic mice.

| Mouse lines | Mouse analyzed (n) | Red blood cell count (× 104/µl) | Hematocrit (%) | Hemoglobin (g/dl) | Platelet count (× 104/µl) | White blood cell count (×102/µl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 6 | 928.3 ± 42.8 | 43.1 ± 0.9 | 12.7 ± 0.2 | 83.0 ± 4.6* | 52.6 ± 27.4 |

| Wild type | 6 | 973.0 ± 39.8 | 45.4 ± 1.8 | 13.2 ± 0.3 | 80.3 ± 1.6 | 59.0 ± 16.1 |

| ΔNF | 4 | 873.7 ± 97.5 | 40.8 ± 5.7 | 11.8 ± 1.5 | 97.2 ± 17 | 106.7 ± 28.9 |

| ΔCF | 4 | 838.0 ± 30.2 | 42.6 ± 1.3 | 12.8 ± 0.4 | 45.7 ± 8.9* | 93.3 ± 32.5 |

| ΔNT | 4 | 1031.3 ± 35.7 | 45.0 ± 1.2 | 12.8 ± 0.3 | 86.5 ± 1.9 | 76.7 ± 14.8 |

| ΔNTNF | 4 | 901.3 ± 32.4 | 46.3 ± 2.1 | 13.7 ± 0.3 | 89.8 ± 10 | 73.7 ± 31.9 |

*P <0.05. High transgene expressor lines were used for this analysis, except for ΔNF, in which medium expressor line was used. Age-matched BDF1 mice were used as controls.

To examine the function of each of the GATA-1 domains during erythropoiesis, we crossed heterozygous GATA-1.05 female mice with transgenic male mice. The expression of GATA-1 HRD-directed GATA-1 proteins in the yolk sacs of E9.5 embryos was analyzed by immunohistochemistry using either N6 or polyclonal GATA-1 antibody. Neither GATA-1 antibody could detect GATA-1 in GATA-1.05/Y embryonic yolk sacs (Figure 2C and D), but cells expressing GATA-1 were detected in the yolk sacs of wild-type embryos (Figure 2E and F). GATA-1 was also detected in GATA-1.05/Y compound mutant embryos bearing all four types of GATA-1 deletion transgenes, ΔNF, ΔCF, ΔNT and ΔNTNF, at medium expression levels (Figure 2G, H, I and J, respectively).

Since we counterstained these sections with methyl green, the cell nuclei were stained green. We noticed heterocellular staining of the yolk sac hematopoietic cells with both GATA-1 antibodies. This heterogeneity seems to reflect differential GATA-1 gene expression during primitive erythroid cell differentiation, as GATA-1 expression in yolk sacs is much stronger in primitive erythroid progenitors at E8.5 than in mature primitive erythrocytes at E10.5 (Onodera et al., 1997b). These results demonstrate that the modified GATA-1 proteins accumulated in the erythroid compartment of the compound mutant mice.

Both zinc fingers of GATA-1 are vital for embryonic and adult erythropoiesis

While no GATA-1.05/Y newborns were recovered from among 90 pups, transgenic expression of wild-type GATA-1 mRNA under GATA-1 HRD regulatory influence efficiently rescued the GATA-1.05/Y pups from embryonic lethality (Table II). The rescued compound mutant mice were normal and fertile, indicating that transgenic expression of GATA-1 can sustain erythropoiesis in mice with a GATA-1.05 germline mutant background. We will refer to these rescued compound mutants as G1R (GATA-1 transgene rescued) mice. We obtained 10 newborn mice with a GATA-1.05/Y compound genotype expressing high or low levels of transgenic GATA-1. Interestingly, a transgenic mouse line expressing a low level of transgenic GATA-1 showed a similar efficiency of rescue compared with lines expressing the transgene more abundantly (Table II). This observation supports the basic hypothesis underlying our experimental strategy, namely that appropriate temporo-spatial accumulation of transgene-derived GATA-1 can function efficiently to complement the loss of endogenous GATA-1.

Table II. Transgenic rescue of GATA-1.05 mutant mice from embryonic lethality.

| Construct | Expression level | No. of pups | X/Y::transgene (−) |

X/Y::transgene (+) |

GATA-1.05/Y::transgene (−) | GATA-1.05/Y::transgene (+) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | |||||

| Wild type | high | 43 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| low | 47 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 7 | |

| ΔNF | medium | 125 | 19 | 15 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| low | 17 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| ΔCF | high | 59 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| medium | 31 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| ΔNT | high | 111 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 0 | 15 | 16 |

| medium | 152 | 22 | 24 | 22 | 0 | 6 | 22 | |

| low | 48 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 7 | |

| ΔNTNF | high | 35 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| medium | 74 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| low | 45 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

In contrast to the interbreeding results obtained above, GATA-1.05/Y compound mutant mice could not be rescued from embryonic lethality by the independent expression of the GATA-1 mutant cDNAs ΔNF and ΔCF. In fact, no GATA-1.05/Y::transgene compound mutant pups were recovered from two lines expressing either ΔNF or ΔCF transgenes at high, medium or low levels (Table II). These results demonstrate that both the NF and the CF are vital for erythropoiesis.

Requirement for the NT domain for embryonic erythropoiesis

Curiously, we observed significant variation in the ability of different transgenic ΔNT lines to rescue the GATA-1.05 mutant allele. For instance, when the ΔNT mutant was expressed at medium or low levels, compound mutant pups were born alive, albeit at a much lower frequency (∼25%) than Mendelian expectations (Table II). In contrast, when ΔNT was expressed at high levels, compound mutant mice were completely rescued (G1ΔNTR mice, Table II). This suggests that, unless overexpressed, ΔNT was only poorly capable of rescuing the embryonic lethality normally observed in the GATA-1.05/Y mouse. Both high and medium level expression of the ΔNT mutant transgene resulted in comparable hematopoietic indices in adult rescued mice (data not shown), and the adult G1ΔNTR mice were fertile. Transgenic mouse lines expressing high, medium or low levels of the ΔNTNF allele were unable to rescue the GATA-1.05/Y defect (Table II). These findings thus demonstrate that when transgene-derived mRNA levels are comparable with endogenous GATA-1, the NT domain of GATA-1 is important for hematopoiesis. The results also indicate that if a mutant GATA-1 protein lacking the NT domain is expressed at greater than endogenous abundance, other domain(s) of GATA-1 can complement missing NT domain function.

Primitive hematopoiesis is blocked in the absence of CF

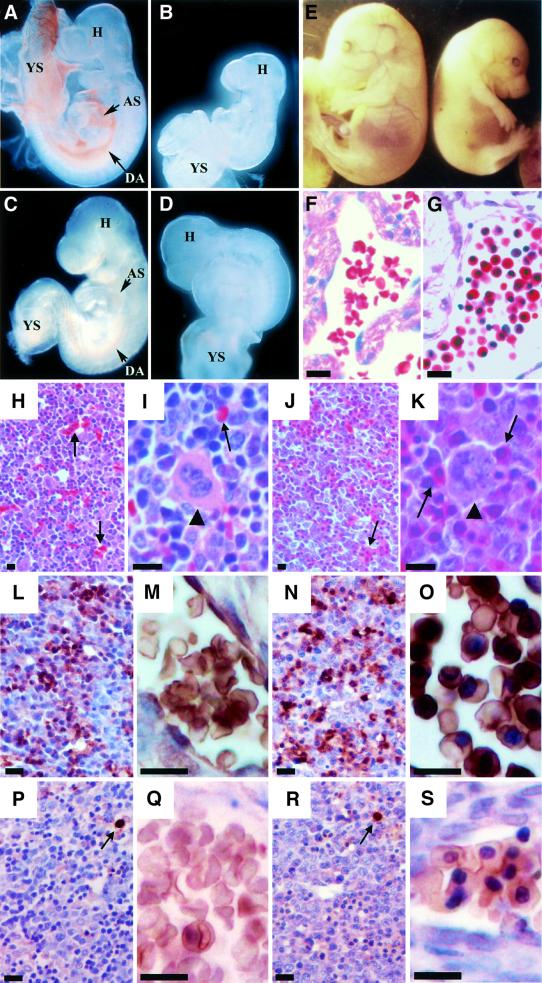

During embryonic development, the hematopoietic center in mice changes from the yolk sac to the fetal liver. Concomitant with this switch, red cell morphology also changes from primitive (nucleated) cells to definitive (enucleated) cells. To investigate the requirement for the three functional domains of GATA-1 for embryonic erythropoiesis, we next examined transgene-rescued GATA-1.05/Y embryos. Male embryos were identified by detection of the Y chromosome-specific gene Zfy-1 by PCR (Koopman et al., 1991). Although GATA-1.05/Y mutant embryos were alive, as defined by beating hearts at E10.5, these male mutant embryos were already paler and smaller (Figure 3B) than their wild-type littermates (Figure 3A) even at this early stage, indicating that GATA-1 function is required for primitive hematopoiesis. We could not detect mature primitive erythroid cells macroscopically in the yolk sac of hemizygous GATA-1.05 mutant embryos (Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. Phenotypes of GATA-1.05/Y germline mutant embryos expressing wild-type or mutant GATA-1 transgenes. (A–D) Analysis of E9.5 embryos and yolk sacs. While wild-type yolk sacs and embryos contain abundant red blood cells (A), the GATA-1.05/Y embryos at E9.5 are pale and small, and red blood cells are not detected (B). GATA-1.05/Y embryo bearing the ΔNF transgene is normal in size at the E9.5 stage and red blood cells are clearly seen in the embryos (C). GATA-1.05/Y embryos bearing the ΔNTNF transgene do not grow well and are severely anemic (D). YS, yolk sac; H, embryo head; AS, aortic sac; DA, dorsal aorta. (E) An E15.5 embryo with GATA-1.05/Y::ΔNF (G1ΔNFR; right) is small and pale in comparison with its wild-type sibling (left). (F–K) Histological examination of the E15.5 G1ΔNFR and wild-type embryos with hematoxylin–eosin staining. Whereas enucleated red blood cells exist abundantly in the wild-type blood vessels (F), many nucleated erythroid cells are circulating in G1ΔNFR embryos (G). The liver of E15.5 wild-type embryo is filled with enucleated mature definitive erythroid cells (arrows in H and I) and megakaryocytes (arrowhead in I). In the liver of the E15.5 G1ΔNFR embryo, megakaryocytes (arrowhead in K) similarly are found, but such enucleated erythrocytes are not found (J and K). The arrows in (J) and (K) indicate nucleated erythroid cells. (L–S) Expression of β-major and εy-globins in the liver of E15.5 wild-type and G1ΔNFR mutant embryos. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed with either anti-β-major (L–O) or anti-εy-globin (P–S) antibody. (M) and (O) are higher magnifications of (L) and (N), respectively. A large number of erythroid cells positive for β-major globin (brown color) are seen both in the liver of wild-type (L and M) and G1ΔNFR (N and O) embryos. In contrast, only a small number of εy-globin-positive erythroid cells are found in both the wild-type (P and Q) and G1ΔNFR (R and S) embryos (arrows). (Q) and (S) are higher magnifications of (P) and (R), respectively, both of which show εy-globin-negative cell clusters. As sections were counterstained by hematoxylin, nuclei were stained dark in the G1ΔNFR embryo sections. Scale bars correspond to 10 µm.

The C-terminal zinc finger domain was shown to be indispensable for embryonic erythropoiesis, as all GATA-1.05/Y embryos bearing the ΔCF transgene died by E12.5 (Table III). At E9.5, GATA-1.05::ΔCF compound mutant embryos were pale and failed to develop blood islands in the yolk sac (data not shown). Furthermore, the appearance of the GATA-1.05::ΔCF mutant embryos at E9.5 was quite similar to that of the GATA-1.05/Y embryos.

Table III. Transgenic rescue of GATA-1.05 mutant embryos from lethality.

| Time of analysis | Constructs | Expression level | No. of pups | X/Y::transgene (–) |

X/Y::transgene (+) |

GATA-1.05/Y::transgene (–) |

GATA-1.05/Y::transgene (+) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | ||||||

| E8.5–10.5 | ΔNF | medium | 84 | 14 | 5 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| low | 55 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 15 | 7 | 7 | ||

| ΔCF | high | 18 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| medium | 56 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 7 | ||

| ΔNT | high | 7 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| medium | 41 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | ||

| low | 30 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 4 | ||

| ΔNTNF | high | 43 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| medium | 40 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 | ||

| low | 30 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||

| E13.5–15.5 | ΔNF | medium | 107 | 19 | 7 | 15 | 0 | 16 | 15 |

| low | 161 | 32 | 24 | 23 | 0 | 5 | 23 | ||

| ΔCF | high | 56 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| medium | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| ΔNT | high | 22 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| medium | 43 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 6 | ||

| low | 34 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 5 | ||

| ΔNTNF | high | 43 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| medium | 73 | 27 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | ||

| low | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

A differential requirement for NF during primitive and definitive erythropoiesis

In contrast to the ΔCF mutant, E9.5 GATA-1.05/Y embryos expressing the ΔNF mutant (G1ΔNFR) were similar in size to their wild-type littermates and accumulated a comparable number of mature primitive erythroid cells (Figure 3C and data not shown). Furthermore, almost all G1ΔNFR embryos were able to survive until E15.5, but not far beyond (Table III). These results indicate that primitive hematopoiesis is fully sustained by expression of the ΔNF mutant protein at endogenous GATA-1 levels.

Phenotypically, these G1ΔNFR embryos were easily distinguishable from their wild-type littermates following the switch from yolk sac to fetal liver hematopoiesis. By E15.5, the G1ΔNFR embryos became small and appeared to be anemic in comparison with their wild-type littermates (Figure 3E). Histological examination revealed that, as well as being observed in normal liver (Figure 3H and I, arrows), enucleated mature definitive erythrocytes were present in the wild-type circulation (Figure 3F). In contrast, erythroid cells circulating in the blood vessels of G1ΔNFR embryos were mostly nucleated (Figure 3G). Only nucleated erythroid progenitors (Figure 3J and K, arrows) as well as megakaryocytes (arrowhead) were present in the G1ΔNFR embryonic liver.

We wished to ascertain the origin of the nucleated erythroid cells present in G1ΔNFR embryos. Definitive and primitive erythroid lineages can be distinguished using anti-β-major and anti-εy-globin antibodies. Therefore, these antibodies were used to detect globin proteins present in the wild-type and G1ΔNFR embryonic livers (Figure 3L–S). Cytoplasmic globins were stained brown by globin antibodies and nuclei were counterstained dark violet by hematoxylin. In wild-type embryonic liver, definitive enucleated erythrocytes were stained positively by the β-major globin antibody (Figure 3L and M). Similarly, in G1ΔNFR embryonic liver, the majority of nucleated erythroid cells expressed β-major globin (Figure 3N and O). In contrast, in both wild-type and G1ΔNFR embryonic livers, only a small number of erythroid cells express εy-globin (Figure 3P–S, arrows). In combination, these results demonstrate that in the G1ΔNFR embryos, definitive hematopoiesis could initiate, but the ΔNF mutant protein is incapable of supporting full maturation of definitive erythroid progenitors.

To discriminate between the contributions made by the NF and the NT domains during primitive erythropoiesis, the ability of the ΔNTNF transgene to rescue the GATA-1.05/Y embryos was compared with that of the ΔNF transgene. Despite expression of the ΔNTNF transgene in a line allowing higher expression levels than endogenous GATA-1, no GATA-1.05/Y::ΔNTNF embryos were recovered beyond E12.5 (Table III). At E9.5, all GATA-1.05/Y::ΔNTNF embryos were smaller than wild type and displayed severe anemia (Figure 3D). These results led to the surprising conclusion that a GATA-1 mutant protein missing the NF domain can fully sustain primitive erythropoiesis only because the NT domain is able to compensate for a primitive erythroid function of GATA-1.

We mentioned earlier that ΔNT rescues the GATA- 1.05/Y phenotype from embryonic lethality. When these G1ΔNTR embryos were examined in detail, we found that expression of the ΔNT mutant at a level similar to endogenous GATA-1 rescued seven embryos from lethal anemia until E15.5 (Table III). As the statistically expected number of embryos was six, this indicates that expression of the ΔNT mutant at endogenous levels can completely rescue GATA-1.05/Y mutants from the early embryonic lethality. However, the appearance of the G1ΔNTR embryos showed significant variation; one was normal and the remaining six were anemic. This suggests that some of these embryos would die later during gestation, consistent with the lower frequency of rescue of pups by this mutant protein (Table II). Given the complete failure of rescue by the ΔNTNF mutant protein, we conclude that the NF domain can fully sustain primitive hematopoiesis, but can only partially compensate for loss of NT during definitive hematopoiesis.

NF regulates the expression of definitive heme biosynthesis genes

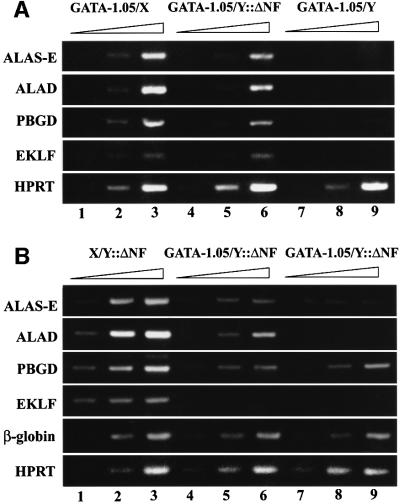

Finally, we investigated the expression of several erythroid genes that have been implicated to be under the direct regulatory influence of GATA-1 in G1ΔNFR embryos. We examined the expression of genes encoding heme biosynthetic enzymes, such as erythroid 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS-E), 5-aminolevulinate dehydratase (ALAD) and porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD), as well as the gene encoding the erythroid transcription factor EKLF. As shown in Figure 4A, the expression of all four genes was markedly diminished in E9.5 GATA-1.05/Y embryonic yolk sacs (lanes 7–9) compared with GATA-1.05/X embryos (lanes 1–3). These results indicate that GATA-1 is indeed required for the expression of these genes during primitive erythropoiesis. Importantly, at E9.5, this array of target genes was expressed in the G1ΔNFR embryos (lanes 4–6) at levels comparable with those in wild type. Thus, the function of the NT domain appears sufficient for the induction and maintenance of normal gene expression mediated by GATA-binding sites in primitive erythroid cells, even in the absence of the GATA-1 NF domain.

Fig. 4. Impaired expression of heme biosynthetic enzymes and EKLF in G1ΔNFR embryos. Expression of three heme biosynthetic enzymes and EKLF was analyzed by semiquantitative RT–PCR by changing amplification cycles, as indicated by a triangle on the top of each panel. (A) mRNA abundance of ALAS-E, ALAD, PBGD and EKLF was determined in E9.5 yolk sacs from GATA-1.05/X (lanes 1–3), GATA-1.05/Y::ΔNF (lanes 4–6) and GATA-1.05/Y embryos (lanes 7–9). The products were analyzed after 27, 30 and 33 cycles of amplification for ALAS-E, ALAD and PBGD; after 32, 35 and 38 cycles for EKLF; and after 24, 27 and 30 cycles for HPRT. (B) Expression of the same set of mRNAs was also examined in the E15.5 embryonic livers from X/Y::ΔNF (lanes 1–3) and two independent GATA-1.05/Y::ΔNF mice (lanes 4–6 and 7–9). The products were analyzed after 27, 30 and 33 cycles of amplification for PBGD and HPRT; after 30, 33 and 36 cycles for ALAS-E, ALAD and β-globin; and after 36, 39 and 42 cycles for EKLF.

In contrast, the expression of these GATA-1 target genes, especially ALAS-E, ALAD and EKLF, was severely impaired by E15.5 in G1ΔNFR mutant embryonic livers (Figure 4B). At E15.5, the expression of these genes in two G1ΔNFR embryos (lanes 4–9) was much lower than in their littermate that did not possess the GATA-1.05 allele (lanes 1–3). However, a comparable level of β-globin mRNA accumulation was observed in the G1ΔNFR and wild-type embryos. Thus, the ΔNF transgene was able to rescue the expression of the former genes solely in primitive erythroid cells (Figure 4A), but not in the definitive erythroid cells (Figure 4B). Although the molecular basis for this difference is not clear, it is intriguing to note that the NT domain function of GATA-1 for the activation of target genes is distinct in the primitive and definitive erythroid lineages.

Discussion

Targeted disruption of the GATA-1 gene causes the maturation arrest of erythroid and megakaryocytic lineage cells, and leads to male GATA-1 mutant embryonic lethality. By exploiting the gene regulatory activity of a GATA-1 HRD minigene to recapture the endogenous expression profile of GATA-1 in hematopoietic lineages, we developed a transgenic method to rescue male GATA-1 knock-down embryos (Takahashi et al., 2000). The transgenic expression of GATA-1 cDNA efficiently rescued male GATA-1 mutant embryos in a reproducible manner, with rescued mutants displaying a phenotypically normal appearance in every way. In this study, we assessed the individual contribution of each of three GATA-1 domains, previously implicated in cell culture studies as critical to GATA-1 function, using the transgenic rescue strategy. Novel insights into the function of these three GATA-1 domains can be drawn from these analyses. Most importantly, the results revealed, for the first time, independent functions of, as well as collaborative relationships among, these three GATA-1 functional domains.

Several earlier lines of evidence suggested that the NF and CF are essential, whereas the NT domain is dispensable for GATA-1 function during erythroid or megakaryocytic cell differentiation (Blobel et al., 1995; Visvader et al., 1995). An erythroid cell line G1E, generated from GATA-1-null ES cells, is able to proliferate as immature erythroblasts, yet can differentiate upon restoration of GATA-1 function (Weiss et al., 1997). The rescue of terminal erythroid differentiation in G1E cells by retroviral expression of mutant GATA-1 was used as a cellular assay in which to evaluate the functional significance of various domains of GATA-1 in an erythroid environment. This led to two conclusions: first, the NT domain is dispensable for terminal erythroid maturation of G1E cells; and secondly, both the NF and CF were required for GATA-1-mediated erythroid differentiation in vitro. With respect to CF function, we demonstrated that the ΔCF mutant transgene is unable to rescue GATA-1.05/Y embryos from embryonic lethality, in substantial agreement with the cell culture studies. Compound mutant embryos bearing the GATA-1.05/Y::ΔCF transgene were indistinguishable from the GATA-1.05/Y embryos at E9.5. Since CF encompasses the DNA-binding domain of GATA-1, the most plausible explanation for this phenotype is that site-specific binding to DNA is necessary for GATA-1 function.

The in vivo rescue approach described here revealed two new aspects of GATA-1 domain function that were simply cryptic in the cell culture studies. First, the present data show that a determinant within the N-terminal 83 amino acids is essential for GATA-1 function and that ΔNT was only able to rescue definitive erythropoiesis fully when expressed at significantly higher levels than endogenous. Indeed, the number of pups rescued by the ΔNT mutant (G1ΔNTR mice) was tightly linked to the expression level of transgenic ΔNT GATA-1. Importantly, the activity of the NT domain does not seem to be specific to the erythroid lineage, since the transactivation activity of this domain is reproducible in transfection experiments in fibroblasts (e.g. Figure 1). Detailed structure–function analysis of the NT domain is therefore the next important goal for establishing a comprehensive understanding of how GATA-1 contributes to erythroid gene regulation.

The second novel feature of GATA-1 revealed in this study is that the transgenic expression of either the ΔNT or ΔNF mutants at the endogenous level almost fully rescues primitive erythropoiesis. Thus, another clear conclusion from this work is that either one, but not both, of those (NF or NT) domains is dispensable for primitive erythropoiesis. Since the ΔNTNF mutant transgene was unable to rescue, while the ΔNF mutant was able to rescue primitive erythropoiesis, we conclude that the NT domain retains a compensatory activity for the lack of NF in the primitive erythroid lineage. In contrast, definitive erythropoiesis in the germline mutant mouse was either not rescued (ΔNF) or rescued less efficiently (ΔNT) by endogenous levels of the two mutant GATA-1 proteins. We therefore conclude that definitive erythropoiesis, unlike primitive erythroid differentiation, requires all three of these domain functions. Thus, these results demonstrate for the first time a distinction between the utilization of these discrete domains of GATA-1 during primitive versus definitive erythropoiesis.

We previously found that GATA-1.05/Y ES cells did not express mRNAs encoding the first three heme biosynthesis enzymes efficiently (Suwabe et al., 1998). In good agreement with the in vitro differentiation analysis, the heme biosynthesis enzyme mRNAs were also not expressed abundantly in the primitive erythroid cells of GATA-1.05/Y embryos, indicating that the erythroid heme biosynthetic enzymes are important target genes of GATA-1. Consistent with this notion, targeted disruption of the ALAS-E gene resulted in anemia and lethality by E11.5, a quite similar phenotype to the GATA-1.05/Y mutant mouse (Nakajima et al., 1999). Thus, heme deficiency seems tightly linked to the cause of death of the GATA-1.05/Y mutant embryos.

One important observation here is that the transgenic expression of the ΔNF mutant rescued the expression of heme biosynthetic enzymes in primitive erythroid cells, but not in definitive erythroid cells. Although the molecular basis for this difference remains to be elucidated, it is intriguing to note that the functional domains of GATA-1 required for the activation of target genes are different in primitive and definitive erythroid cell lineages. The livers of G1ΔNFR embryos contain megakaryocytes and nucleated erythroid cells that can be stained positively with an anti-β-globin antibody. The livers also contain more mitotic cells than do the littermate wild-type embryos. Since the primitive erythroid lineage has virtually disappeared in the E15.5 liver, the nucleated cells detected there are most likely to be definitive erythroid cells that cannot mature terminally in the absence of GATA-1. This result demonstrates that GATA-1 is essential for the terminal differentiation of definitive erythroid cell lineage.

The GATA-1 NF has been shown to interact with multiple coactivators/transcription factors, such as FOG-1. FOG-1-deficient mice die of anemia between E10.5 and E12.5, displaying a slightly milder phenotype than GATA-1-deficient embryos (Tsang et al., 1998). The present data indicate that the interaction of coactivators/transcription factors with NF is not vital for either primitive erythropoiesis or fetal liver megakaryopoiesis, since an expression level of ΔNF transgene equivalent to endogenous levels could sustain both. Taken together, these results suggest that, perhaps surprisingly, the contribution of FOG-1 to both primitive hematopoiesis (which consists almost entirely of erythropoiesis) and fetal liver megakaryopoiesis may be independent of GATA-1. In addition, it was reported recently that the cause of familial X-linked dyserythropoietic anemia and thrombocytopenia could be traced to a mutation within the FOG-1 interaction site in the GATA-1 NF. This provides strong evidence that FOG-1–GATA-1 association is indeed important for definitive erythropoiesis and platelet formation (Nichols et al., 2000). Since signs of the disease are present at 16 weeks of gestation, however, primitive hematopoiesis may be unimpaired in these individuals, consistent with the present analysis.

We previously found that GATA-1 gene transcription is modulated by at least two regulatory elements that are distinct in primitive and definitive erythroid cell lineages (Onodera et al., 1997b). It is therefore interesting to note that the domain function of GATA-1 is also distinct in the two different erythroid lineages. We speculate that the differential utilization of multiple, sometimes interdependent, regulatory domains of GATA-1 in definitive erythroid lineage cells would provide a mechanism for ensuring proper lineage specification, a process significantly more complex for definitive myeloery throid hematopoietic cell development than for primitive erythropoiesis.

Materials and methods

Mouse GATA-1 mutants

GATA-1 mutant cDNAs were synthesized using a two-step construction method. Both N- and C-terminal fragments flanking each mutation were generated by PCR and then subcloned into pBluescript vector (Stratagene). To construct ΔNT, an N-terminal fragment was generated using G1-S1 (5′-AAGCGGCCGCATCGTCATTTGT) and G1-A1 (5′-ATCCATGGGAACACTGGGGTTG) primers, and the C-terminal fragment was generated using G1-S2 (5′-ACACCATGGAGGGAATTCCTGG) and G1-A4 (5′-TGCGGCCGCCCTTATCTACATA) primers. For the ΔNF mutant, an N-terminal fragment was generated using G1-S1 and G1-A2 (5′-AAGGATCCAATGGCAGGCTTCC) primers, while the C-terminal fragment was generated with G1-S3 (5′-CTTGGATCCCAAGATGAATGGTC) and G1-A4 primers. For the ΔCF cDNA, the N-terminal fragment was generated with G1-S1 and G1-A3 (5′-ATTGGGATCCTGCCCGTTTGCT) primers, and the C-terminal fragment was generated using G1-S4 (5′-GCGGATCCTATTTCAAGCTCCAT) and G1-A4 primers.

The PCR products were digested with BamHI and NotI, and cloned into the NotI site of pBluescript. The ΔNTNF mutant was synthesized by an EcoRI and PstI digestion of the ΔNF mutant, and cloned into the same restriction sites of the ΔNT mutant. To prepare the GATA-1 mutants for transfection or microinjection, each GATA-1 mutant cDNA was subcloned into the NotI sites of pEF-BOS (Mizushima et al., 1990) or IE3.9int plasmid vectors (Onodera et al., 1997b), respectively.

Immunoblot analysis

Wild-type or mutant pEF-GATA-1 (10 µg) was transfected into 293T cells using calcium phosphate. After washing with cold phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were lysed and proteins were analyzed by standard immunoblotting procedures. The blots were incubated with either the N6 monoclonal antibody (Ito et al., 1993) or rat polyclonal antibody against mouse GATA-1. The membrane was then developed with a 1:1000 dilution of sheep anti-rat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. After washing, the blots were incubated with ECL™ (Amersham) to visualize the immunoreactive bands. The blots were stripped and reprobed again with an anti-lamin B antibody (Santa Cruz).

EMSA

Nuclear extracts were prepared from QT6 cells transfected with wild-type or mutant GATA-1 expression plasmids as previously described (Onodera et al., 1997a). A 1 µg aliquot of nuclear protein was tested for EMSA. MαP oligonucleotide was end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham). The assay was performed as previously described (Yamamoto et al., 1990).

Immunocytochemistry

QT6 cells were seeded on Lactec chamber slides (Falcon) and transfected with wild-type or mutant GATA-1 expression plasmids using FuGene transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics). After 48 h, cells were fixed with periodate–lysine–paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with 100% acetone for 5 min at –20°C. Immunostaining was performed using the N6 antibody or polyclonal anti-GATA-1 antibody (Ito et al., 1993). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Zymed) was used as secondary antibody. Counterstaining was performed using DAPI (Molecular Probes).

Transfection assays

QT6 cells were transfected with 0.2 µg of the wild-type pEF-GATA-1 or the deletion mutants, together with 0.2 µg of the pRBGP3-MαP reporter gene (Igarashi et al., 1994) and chicken β-actin promoter-LacZ plasmid (Niwa et al., 1991) as an internal control. Cells were harvested and lysates were prepared for LUC and LacZ assays 30 h after the transfection. LUC activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity. The means of three or more independent experiments were averaged.

Generation of transgenic mice and breeding with GATA-1.05 mutant mice

GATA-1 mutant cDNAs were cloned 3′ to the IE3.9int genomic fragment (Nishimura et al., 2000). DNA fragments were purified from the plasmid vector sequence and transgenic mice were generated by microinjection of DNA into fertilized BDF1 eggs using standard procedures (Wassarman and Depamphilis, 1993). Founders were screened by PCR and positives were verified by a Southern blot analysis. The GATA-1.05 allele was monitored by PCR using primers corresponding to the neomycin resistance gene in the original GATA-1.05 targeting vector (Takahashi et al., 1997).

Peripheral blood cell analysis

Mice were bled from the retro-orbital plexus, and hematopoietic indices were determined using a hemocytometer (Nihon Koden Co.). Data obtained from 4–6 adult mice were averaged.

RT–PCR

Total RNA from the spleens of F1 or F2 transgenic mice was prepared by the RNA-sol extraction system (Tel-Test). The cDNAs were synthesized with Superscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). For analyzing the expression of GATA-1 mutants, the amount of reverse transcribed cDNA was adjusted by dilution to give an amount equivalent to that of the endogenous GATA-1 cDNA amplicon. The primers used were S1 (5′-GCTGAATCCTCTGCATCAAC) and AS1 (5′-TAGGCCTCAGCTTCTCTGTA) or S1 and AS2 (5′-TAGAGTGCCGTCTTGCCATA). For quantitative RT–PCR analysis of mRNAs, the amount of cDNA was diluted to give an amount equivalent to that of the HPRT amplicon. The other primers used in this study were as described previously (Suwabe et al., 1998). Each primer pair was designed to span at least one intron to distinguish amplicons originating from cDNA and genomic DNA.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Kimi Araki for providing the internal control vector, Nobunao Wakabayashi for technical advice, and Tania O’Connor, Kim-Chew Lim and Melin Khandekar for discussion and advice. This work was supported by an NIH grant (J.D.E.) and grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture (R.S., S.T. and M.Y.), JSPS-RFTF and CREST (M.Y.) and PROBRAIN (S.T.).

References

- Blobel G.A., Simon,M.C. and Orkin,S.H. (1995) Rescue of GATA-1-deficient embryonic stem cells by heterologous GATA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 626–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungert J. and Engel,J.D. (1996) The role of transcription factors in erythroid development. Ann. Med., 28, 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enver T. and Greaves,M. (1998) Loops, lineage and leukemia. Cell, 94, 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbes T.R., Thorne,A.W. and Crane-Robinson,C. (1988) A direct link between core histone acetylation and transcriptionally active chromatin. EMBO J., 7, 1395–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K., Kataoka,K., Itoh,K., Hayashi,N., Nishizawa,M. and Yamamoto,M. (1994) Regulation of transcription by dimerization of erythroid factor NF-E2 p45 with small Maf proteins. Nature, 367, 568–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito E., Toki,T., Ishihara,H., Ohtani,H., Gu,L., Yokoyama,M., Engel,J.D. and Yamamoto,M. (1993) Erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 is abundantly transcribed in mouse testis. Nature, 362, 466–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman P., Gubbay,J., Vivian,N., Goodfellow,P. and Lovell-Badge,R. (1991) Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature, 351, 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D.I.K. and Orkin,S.H. (1990) Transcriptional activation and DNA binding by the erythroid factor GF-1/NF-E1/Eryf 1. Genes Dev., 4, 1886–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merika M. and Orkin,S.H. (1995) Functional synergy and physical interactions of the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 with the Kruppel family proteins Sp1 and EKLF. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 2437–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima S., Nagata,S., Takahashi,T., Suwabe,N., Dai,P., Yamamoto, M., Ishii,S. and Nakano,T. (1990) pEF-BOS, a powerful mammalian expression vector. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motohashi H., Katsuoka,F., Shavit,J.A., Engel,J.D. and Yamamoto,M. (2000) Positive or negative MARE-dependent transcriptional regulation is determined by the abundance of small maf proteins. Cell, 103, 865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima O., Takahashi,S., Harigae,H., Furuyama,K., Hayashi,N., Sassa,S. and Yamamoto,M. (1999) Heme deficiency in erythroid lineage causes differentiation arrest and cytoplasmic iron overload. EMBO J., 18, 6282–6289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness S.A. and Engel,J.D. (1994) Vintage reds and whites: combinatorial transcription factor utilization in hematopoietic differentiation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 4, 718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols K.E., Crispin,J.D., Poncz,M., White,J.G., Orkin,S.H., Maris,J.M. and Weiss,M.J. (2000) Familial dyserythropoietic anaemia and thrombocytopenia due to an inherited mutation in GATA1. Nature Genet., 24, 266–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura S., Takahashi,S., Kuroha,T., Suwabe,N., Nagasawa,T., Trainor,C. and Yamamoto,M. (2000) A GATA box in the GATA-1 gene hematopoietic enhancer is a critical element in the network of GATA factors and sites that regulate this gene. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 713–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H., Yamamura,K. and Miyazaki,J. (1991) Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene, 108, 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera K. et al. (1997a) Conserved structure, regulatory elements and transcriptional regulation from the GATA-1 gene testis promoter. J. Biochem., 121, 251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera K., Takahashi,S., Nishimura,S., Ohta,J., Motohashi,H., Yomogida,K., Hayashi,N., Engel,J.D. and Yamamoto,M. (1997b) GATA-1 transcription is controlled by distinct regulatory mechanisms during primitive and definitive erythropoiesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 4487–4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekhtman N., Radparvar,F., Evans,T. and Skoultchi,A.I. (1999) Direct interaction of hematopoietic transcription factors PU.1 and GATA-1: functional antagonism in erythroid cells. Genes Dev., 13, 1398–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivdasani R.A. and Orkin,S.H. (1996) The transcriptional control of hematopoiesis. Blood, 87, 4025–4039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwabe N., Takahashi,S., Nakano,T. and Yamamoto,M. (1998) GATA-1 regulates growth and differentiation of definitive erythroid lineage cells during in vitro ES cell differentiation. Blood, 92, 4108–4118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S., Onodera,K., Motohashi,H., Suwabe,N., Hayashi,N., Yanai, N., Nabeshima,Y. and Yamamoto,M. (1997) Arrest in primitive erythroid cell development caused by promoter-specific disruption of the GATA-1 gene. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 12611–12615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S. et al. (2000) GATA factor transgenes under GATA-1 locus control rescue germ line GATA-1 mutant deficiencies. Blood, 96, 910–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor C.D., Omichinski,J.G., Vandergon,T.L., Gronenborn,A.M., Clore, G.M. and Felsenfeld,G. (1996) A palindrome regulatory site within vertebrate GATA-1 promoters requires both zinc fingers of the GATA-1 DNA-binding domain for high-affinity interaction. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 2238–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang A.P., Fujiwara,Y., Hom,D.B. and Orkin,S.H. (1998) Failure of megakaryopoiesis and arrested erythropoiesis in mice lacking the GATA-1 transcriptional cofactor FOG. Genes Dev., 12, 1176–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader J.E., Crossley,M., Hill,J., Orkin,S.H. and Adams,J.M. (1995) The C-terminal zinc finger of GATA-1 or GATA-2 is sufficient to induce megakaryocytic differentiation of an early myeloid cell line. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 634–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman P. and Depamphilis,M. (1993) Guide to Techniques in Mouse Development. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- Weiss M.J., Yu,C. and Orkin,S.H. (1997) Erythroid-cell-specific properties of transcription factor GATA-1 revealed by phenotypic rescue of a gene-targeted cell line. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 1642–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Ko,L.J., Leonard,M.W., Beug,H., Orkin,S.H. and Engel,J.D. (1990) Activity and tissue-specific expression of the transcription factor NF-E1 multigene family. Genes Dev., 4, 1650–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Takahashi,S., Onodera,K., Muraosa,Y. and Engel,J.D. (1997) Upstream and downstream of erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. Genes Cells, 2, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.Y. and Evans,T. (1992) Distinct roles for the two cGATA-1 finger domains. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 4562–4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]