Abstract

Absorption of excess light energy by the photosynthetic machinery results in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as H2O2. We investigated the effects in vivo of ROS to clarify the nature of the damage caused by such excess light energy to the photosynthetic machinery in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Treatments of cyanobacterial cells that supposedly increased intracellular concentrations of ROS apparently stimulated the photodamage to photosystem II by inhibiting the repair of the damage to photosystem II and not by accelerating the photodamage directly. This conclusion was confirmed by the effects of the mutation of genes for H2O2-scavenging enzymes on the recovery of photosystem II. Pulse labeling experiments revealed that ROS inhibited the synthesis of proteins de novo. In particular, ROS inhibited synthesis of the D1 protein, a component of the reaction center of photosystem II. Northern and western blot analyses suggested that ROS might influence the outcome of photodamage primarily via inhibition of translation of the psbA gene, which encodes the precursor to D1 protein.

Keywords: cyanobacterium/D1 protein/H2O2-scavenging enzyme/photosystem II/reactive oxygen species

Introduction

Oxygen is essential for most living organisms but is also a precursor to reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage cellular components such as proteins, lipids and nucleic acids (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1990). In oxygenic photosynthesis, various ROS, such as the superoxide radical (O2–), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the hydroxyl radical (·OH), are generated as a result of the photosynthetic transport of electrons (Asada, 1996, 1999). When the absorption of light energy by chlorophylls exceeds the capacity for utilization of the energy in photo synthesis, the generation of ROS is greatly accelerated.

High-intensity light is an environmental factor that can damage the photosynthetic machinery of plants and it is often the cause of reductions in the growth and productivity of crop plants (Long et al., 1994). The main target of photodamage is photosystem II (PSII), which is a complex of proteins and pigments that is the site of the photochemical reaction and the subsequent transport of electrons from water to plastoquinone. Photodamage to PSII is mainly due to damage to the D1 protein, which forms a heterodimer with the D2 protein in the reaction center of PSII, and the subsequent rapid degradation of the D1 protein (Barber and Andersson, 1992; Prásil et al., 1992; Aro et al., 1993; Andersson and Barber, 1996).

A number of reports have suggested that ROS are involved in the photodamage to PSII (Prásil et al., 1992; Aro et al., 1993; Andersson and Barber, 1996). ROS such as O2– (Chen et al., 1992), H2O2 (Ananyev et al., 1992; Miyao et al., 1995) and ·OH (Miyao et al., 1995) were shown to induce the cleavage of the D1 protein directly in vitro. Besides such ROS, 1O2, which is generated by transfer of excitation energy in the reaction center of PSII, is often considered to trigger degradation of the D1 protein (Vass et al., 1992; Hideg et al., 1994; Telfer et al., 1994; Okada et al., 1996). Since the cited studies were conducted in vitro using thylakoid membranes or PSII complexes, the action of ROS in living cells in which the ROS-scavenging system is fully active is still in question.

In the present study, we examined whether ROS, such as H2O2, act primarily by accelerating the damage to PSII directly or by inhibiting the repair of the photodamage to PSII in vivo, using the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis). We found that increased intracellular concentrations of ROS inhibited repair of the photodamage to PSII. Labeling of proteins in vivo and northern and western blot analyses demonstrated that ROS primarily inhibited the synthesis of the D1 protein de novo at the translational level at both the initiation and elongation steps.

Results

Light and ROS act synergistically in the photodamage to PSII

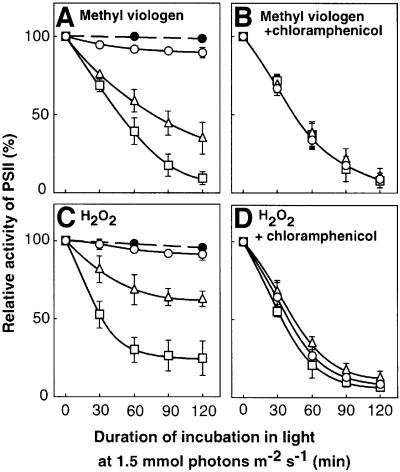

Incubation of Synechocystis cells in strong light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s had no significant effect on the activity of PSII over a 2-h period (Figure 1A; open circles). However, in the presence of chloramphenicol, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, similar incubation resulted in the inactivation of PSII (Figure 1B; open circles). These observations suggested that, in light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s, the rate of repair of photodamage that required the synthesis of proteins de novo was higher than the rate of photodamage to PSII.

Fig. 1. Light-induced inactivation of PSII in the presence of reagents that accelerate the production of ROS in wild-type Synechocystis. Cells were exposed to light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s with standard aeration. (A) In the presence of methyl viologen at 2 µM (open triangles) and at 5 µM (open squares) and in its absence (open circles); filled circles: in the presence of 5 µM methyl viologen in darkness. (B) The same as (A) but in the presence of 200 µg/ml chloramphenicol. (C) In the presence of H2O2 at 0.5 mM (open triangles) and at 2 mM (open squares) and in its absence (open circles); filled circles: in the presence of 2 mM H2O2 in darkness. (D) The same as (C) but in the presence of 200 µg/ml chloramphenicol. PSII activity was monitored in terms of the photosynthetic evolution of oxygen in the presence of 1 mM 1,4-benzoquinone as the electron acceptor. The activity taken as 100% was 527 ± 46 µmol O2/mg chlorophyll/h. Values are means ± SD (bars) of results from four independent experiments.

We next examined the actions of ROS by modulating their intracellular concentrations in cells using reagents that induce the production of ROS. Methyl viologen is an acceptor of electrons that accelerates the production of O2– and H2O2 in light (Asada, 1996). The presence of methyl viologen during the incubation of cells in light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s enhanced the apparent photodamage to PSII (Figure 1A; open triangles and squares). However, when repair of PSII was blocked by the presence of chloramphenicol, the effect of methyl viologen was abolished (Figure 1B; open triangles and squares). In darkness, methyl viologen had no effect on the activity of PSII (Figure 1A; closed circles).

Exogenously supplied H2O2 also accelerated the photodamage to PSII (Figure 1C), suggesting that the agent that accelerated photodamage during incubation in the presence of methyl viologen might have been H2O2. The presence of chloramphenicol during the incubation further accelerated the photodamage and abolished the effect of H2O2 (Figure 1D). Incubation in darkness in the presence of H2O2 had no effect on the activity of PSII (Figure 1C; closed circles). These observations suggested that the enhanced photodamage to PSII in living cells might have been due to inhibition of the repair of PSII and not to direct damage to PSII.

A mutant defective in H2O2-scavenging enzymes with enhanced sensitivity to photodamage to PSII

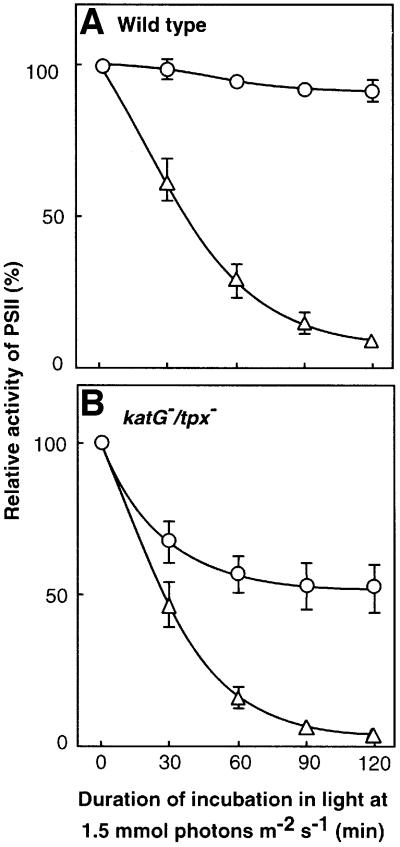

Enzymes that scavenge H2O2, such as catalase peroxidase (Tichy and Vermaas, 1999) and thioredoxin peroxidase (Yamamoto et al., 1999), which are encoded by the katG and tpx genes, respectively, appear to maintain intracellular concentrations of H2O2 at low and non-toxic levels. Targeted mutagenesis of both the katG and tpx genes in Synechocystis cells enhanced photodamage to PSII but had no significant effect on such photodamage in the presence of chloramphenicol (Figure 2). These observations supported the hypothesis that ROS might inhibit the repair of photodamage to PSII.

Fig. 2. Light-induced inactivation of PSII in wild-type Synechocystis and in katG–/tpx– mutant cells. Cells were exposed to light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s in the presence of 200 µg/ml chloramphenicol and in its absence. The other experimental conditions were the same as described in the legend to Figure 1. (A) Wild-type cells. (B) katG–/tpx– cells. Open triangles and circles: in the presence and absence of chloram phenicol, respectively. PSII activity was monitored in terms of the photosynthetic evolution of oxygen. The oxygen-evolving activity of katG–/tpx– cells that was taken as 100% was 560 ± 44 µmol O2/mg chlorophyll/h. Values are means ± SD (bars) of results from four independent experiments.

Inhibition by exogenous H2O2 of the repair of photodamage to PSII

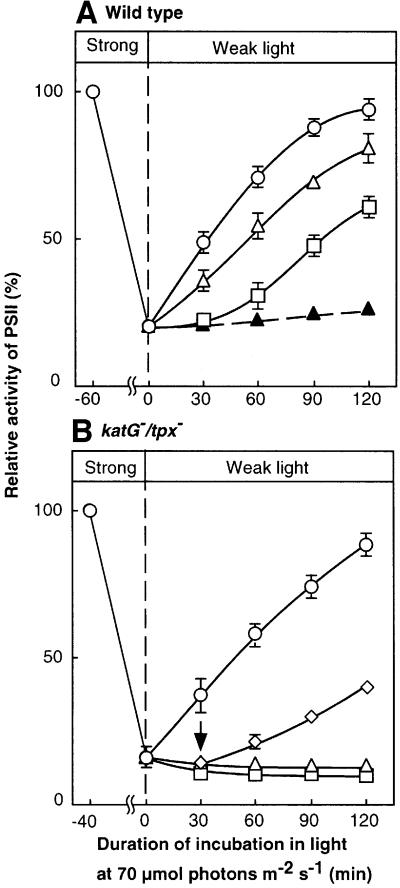

We examined inhibition of repair by H2O2 directly by monitoring the recovery of PSII activity after photodamage (Figure 3). When wild-type cells were incubated in strong light at 3.0 mmol photons/m2/s, PSII activity fell to 20% of the original level. During subsequent exposure of cells to weak light, the activity of PSII returned to the original level (Figure 3A). The presence of H2O2 during the incubation in weak light suppressed the repair of the photodamage to PSII. Targeted mutagenesis of the katG and tpx genes delayed the repair of photodamage (Figure 3B). Furthermore, repair in katG–/tpx– mutant cells was completely eliminated in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2. Removal of H2O2 from the mutant cells by exogenously supplied catalase allowed repair to proceed (Figure 3B; open diamonds).

Fig. 3. Repair of photodamage to PSII and the effects of H2O2 after light-induced inactivation in wild-type Synechocystis and katG–/tpx– cells. Cells were exposed to light at 3 mmol photons/m2/s for 60 min (wild type) or 40 min (katG–/tpx–) without aeration to induce ∼80% inactivation of PSII. Cells were then incubated in light at 70 µmol photons/m2/s with standard aeration in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 (open triangles), 2 mM H2O2 (open squares) or 200 µg/ml chloramphenicol (filled triangles), and in the absence of these reagents (open circles). (A) Wild-type cells. (B) katG–/tpx– cells. Diamond symbols indicate repair after 0.1 µM catalase had been added, at the time indicated by the vertical arrow, to a suspension of cells that had been incubated in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2. Values are means ± SD (bars) of results from three independent experiments.

Inhibition by ROS of the synthesis of the D1 protein

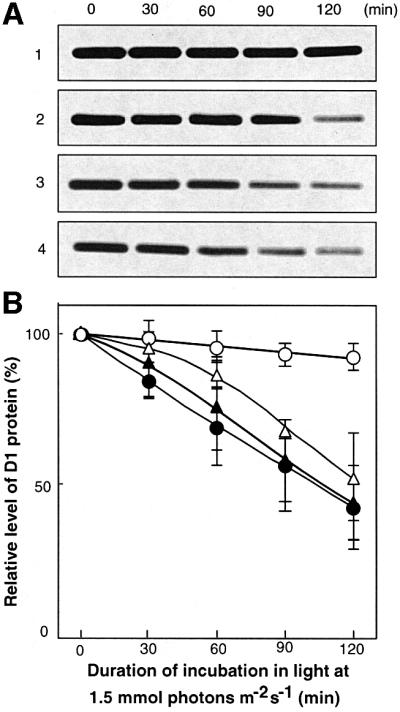

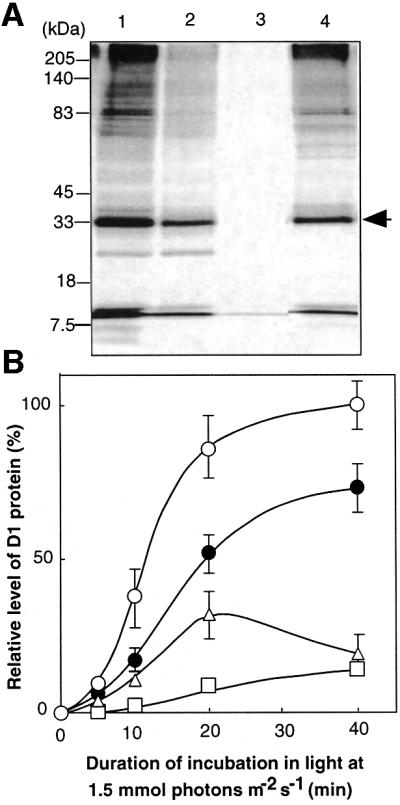

We used western blot analysis to examine changes in the level of the D1 protein when intracellular concentrations of ROS were increased by the presence of methyl viologen during incubation in light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s (Figure 4). The presence of methyl viologen decreased the apparent level of D1 protein. However, the decrease in the level of pre-existing D1 protein, assessed in the presence of chloramphenicol, was unaffected by methyl viologen. Therefore, we postulated that ROS, produced by the photosynthetic transport of electrons that was mediated by methyl viologen, inhibited the synthesis of the D1 protein de novo but did not affect the degradation of this protein.

Fig. 4. Changes in the level of the D1 protein during the light-induced inactivation of PSII in wild-type cells. (A) Results of western blot analysis. (B) Quantitation of the results shown in (A). Cells were exposed to light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s with standard aeration in the absence (lane 1; open circles) and in the presence (lane 2; open triangles) of 5 µM methyl viologen. Cells were also exposed to light in the presence of 200 µg/ml chloramphenicol (lane 3; filled circles) and in the presence of 200 µg/ml chloramphenicol plus 5 µM methyl viologen (lane 4; filled triangles). Thylakoid membranes were isolated from cells at the indicated times. Values are means ± SD (bars) of results from three independent experiments.

We examined the above-mentioned hypothesis by monitoring the incorporation of [35S]methionine into proteins and, in particular, into the D1 protein (Figure 5). The synthesis of the D1 protein de novo was markedly suppressed in the presence of methyl viologen and H2O2. The rate of synthesis of the D1 protein in katG–/tpx– cells was lower than that in wild-type cells, suggesting that inhibition by ROS of the synthesis of the D1 protein in katG–/tpx– cells might have been more severe than that in wild-type cells. Furthermore, not only the synthesis of the D1 protein de novo but also the synthesis of almost all other proteins was suppressed in the presence of ROS (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5. The synthesis of the D1 protein de novo in the presence of ROS in wild-type Synechocystis and in katG–/tpx– cells, as monitored in terms of the incorporation of radioactive [35S]methionine into proteins of thylakoid membranes. (A) Lanes 1–3, wild-type cells were labeled for 20 min in the absence of added reagents (lane 1), in the presence of 5 µM methyl viologen (lane 2) and in the presence of 2 mM H2O2 (lane 3). Lane 4, katG–/tpx– cells were labeled in the absence of any reagent. The arrow indicates the D1 protein. (B) Changes in the level of labeled D1 protein that had been incorporated into thylakoid membranes in wild-type cells in the absence of any added reagents (open circles), in the presence of 5 µM methyl viologen (open triangles), and in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 (open squares); filled circles indicate labeled D1 protein in katG–/tpx– cells in the absence of any added reagents. Values are means ± SD (bars) of results from three independent experiments.

Effects of ROS on the expression of psbA genes

To determine whether ROS might inhibit the synthesis of the D1 protein at the transcriptional level, we examined the expression of psbA genes for the D1 protein in the presence of increased intracellular concentrations of ROS. In Synechocystis, the D1 protein is encoded by a small multigene family that consists of the psbA1, psbA2 and psbA3 genes (Jansson et al., 1987). The psbA1 gene is non-functional, while the psbA2 and psbA3 genes are expressed in response to light (Tyystjärvi et al., 1998) and both encode the identical D1 protein.

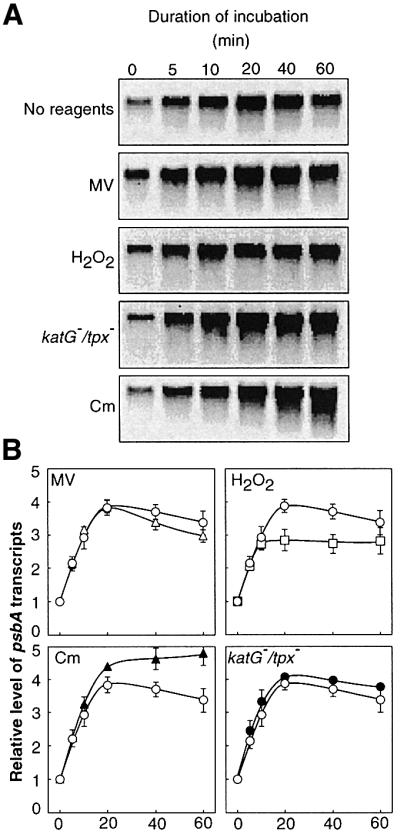

We monitored changes in the level of a mixture of psbA2 and psbA3 transcripts by northern blot analysis (Figure 6). The presence of methyl viologen did not affect the light-induced expression of the psbA genes. At 0.5 mM, H2O2 did not significantly affect the induction of the expression of these genes at the early stage (zero to 10 min) of incubation. However, at 20 min it repressed the level of psbA transcripts to 70% of the control level. Targeted mutagenesis of the katG and tpx genes had no effect on induction of the expression of the psbA genes. Inhibition by chloramphenicol of the translation of the psbA transcripts also had no effect on the induction of expression during a 20-min incubation, and the level of psbA transcripts was maintained subsequently. These observations suggest that the inhibition by ROS during the synthesis of the D1 protein de novo might not occur primarily at transcription.

Fig. 6. Effects of ROS on the light-induced expression of psbA genes in wild-type Synechocystis and katG–/tpx– cells. (A) Results of northern blot analysis. (B) Quantitation of the results in (A). Prior to exposure to light, cells were incubated at 30°C in darkness for 60 min. Wild-type cells were exposed to light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s in the absence of any added reagents (control; open circles) and in the presence of 5 µM methyl viologen (MV; open triangles), 0.5 mM H2O2 (open squares) and 200 µg/ml chloramphenicol (Cm; filled triangles); filled circles indicate induction of the expression of psbA genes in katG–/tpx– cells in the absence of any added reagents. Total RNA (5 µg) was loaded in each lane of the gel. Values are means ± SD (bars) of results from three independent experiments.

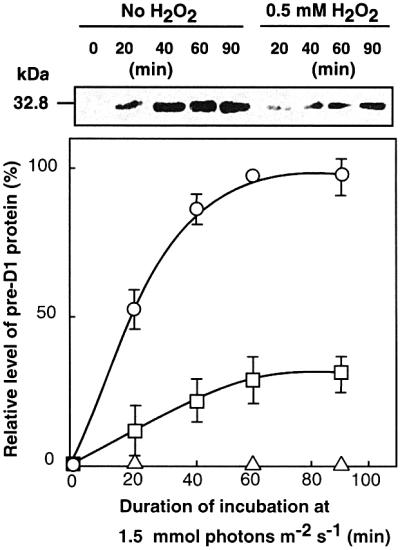

We also examined the action of ROS on the synthesis of the precursor to D1 protein (pre-D1) at the translational level. Figure 7 shows that the level of pre-D1 increased during exposure of wild-type cells to strong light and reached a maximum at 40 min. The presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 significantly depressed induction of the synthesis of pre-D1. These observations suggest that the main target of inhibition by ROS during the synthesis of the D1 protein might be translation.

Fig. 7. Changes in the level of the pre-D1 protein during the light-induced inactivation of PSII in wild-type cells. Cells were exposed to light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s in the absence of H2O2 (open circles), in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 (open squares), and in the presence of 200 µg/ml chloramphenicol (open triangles). Thylakoid membranes were isolated from cells at the indicated times. Values are means ± SD (bars) of results from three independent experiments.

Effects of ROS on the translation of psbA mRNAs

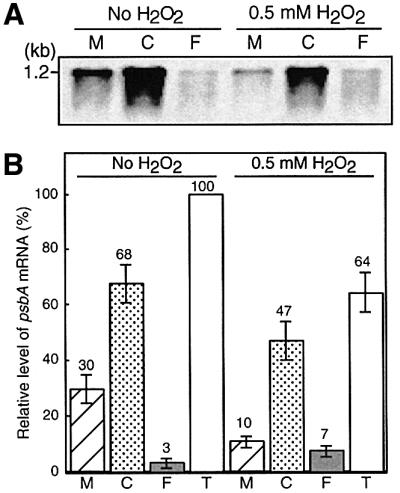

To identify the step in the translation of psbA mRNAs that was inhibited by ROS, we examined the effects of H2O2 on the distribution of psbA mRNAs in membrane-bound and cytosolic polysomes as well as in a polysome-free form in wild-type cells (Figure 8). In Synechocystis, psbA mRNAs are first associated with polysomes in the cytosol (translation initiation) and, after translational elongation has proceeded to a certain extent, psbA mRNA–ribosome complexes are targeted to thylakoid membranes leading to the subsequent elongation (Tyystjärvi et al., 2001; see Discussion).

Fig. 8. Effects of H2O2 on the distribution of psbA mRNAs that are free or are associated with polysomes in wild-type cells. Cells were incubated at 30°C in darkness for 60 min and then exposed to light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s for 20 min in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 and in its absence. Cells were disrupted and membrane-bound polysomes (M), cytosolic polysomes (C) and polysome-free RNA (F) were prepared as described in the text. RNA was isolated from each fraction and subjected to northern blotting with a labeled fragment of the psbA2 gene as the probe. The amount of RNA in each lane corresponded to that from each individual fraction, and each fraction was derived from cells equivalent to 5 µg chlorophyll. (A) Gel-electrophoretic pattern. The results shown are representative of the results of four independent experiments, each of which gave similar results. (B) Quantified results. Values are means ± SD (bars) of results from four independent experiments. T represents the total of the three fractions of psbA mRNA.

Figure 8 shows that, during incubation in light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s, almost all the psbA mRNA was in the form of polysomes, which were either associated with or dissociated from thylakoid membranes. The level of psbA mRNA that was not associated with polysomes was very low. The presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 significantly decreased the relative level of psbA mRNAs in membrane-associated polysomes. These findings suggest that the elongation step in the translation of psbA mRNAs might be strongly inhibited by H2O2. In addition, the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 increased the level of psbA mRNA that was not associated with polysomes, suggesting that the binding of psbA mRNAs to ribosomes, namely the initiation of translation, might be also inhibited by H2O2.

Discussion

In the present study we investigated the actions of ROS in the photodamage to PSII and its repair in Synechocystis cells. Conditions that produced ROS stimulated the apparent photodamage to PSII (Figure 1). Thus, it appeared that ROS might act primarily by inhibiting repair of the photodamage to PSII in vivo (Figure 3A). Inactivation of H2O2-scavenging enzymes also inhibited the repair of the photodamage to PSII (Figure 3B).

Which ROS affect the repair of photodamage?

When the light energy absorbed by the photosynthetic machinery exceeds the energy that is required for photosynthesis, O2– is generated on the acceptor side of photosystem I (Asada, 1996). In Synechocystis, O2– is disproportionated by an Fe-containing superoxide dismutase to H2O2, which is then scavenged by catalase peroxidase and thioredoxin peroxidase (Tichy and Vermaas, 1999; Yamamoto et al., 1999). However, strongly oxidative conditions, for example, the combination of light and the presence of methyl viologen, allow the photosynthetic machinery to produce excessive amounts of O2– and H2O2. In such cases, a small fraction of the H2O2 is converted to the hydroxyl radical ·OH by the action of transition metal cations, such as Fe2+ and Cu2+ (Asada, 1996).

Among the various ROS, O2– is highly reactive and ·OH is extremely reactive, whereas H2O2, which is the most abundant ROS, is the least reactive. We can ask which of the three ROS is active in the inhibition of repair. It is unlikely that O2– is the major contributor to the inhibition because exogenously supplied H2O2, which cannot be converted to O2–, was as effective as the presence of methyl viologen.

Inhibition by ROS of the repair of photodamage to PSII was reversible (Figure 3B), an observation that suggests that the repair system might be inhibited directly by H2O2 and/or ·OH and not by the secondary products of ROS, such as lipid peroxides (Wise, 1995).

Effects of ROS on the de novo synthesis of proteins

Western blot analysis indicated that ROS did not enhance the degradation of the pre-existing D1 protein when protein synthesis was blocked by the presence of chloramphenicol. However, degradation of the pre-existing D1 protein occurred more slowly than inactivation of PSII. This difference might have been caused by the presence of inactivated D1 protein, which was detected by western blot analysis. Since degradation of inactivated D1 protein is coordinated with the synthesis de novo of active D1 protein (Komenda and Barber, 1995), it is likely that inhibition of its synthesis de novo by either ROS or chloramphenicol led to the accumulation of inactivated D1 protein.

Labeling of proteins in vivo provided direct evidence for the inhibition by ROS of the synthesis of the D1 protein de novo (Figure 5). Thus, the enhanced sensitivity of the katG–/tpx– cells to strong light might be explained by the inhibition by ROS of the synthesis of the D1 protein de novo. It is noteworthy, in this context, that not only the synthesis of the D1 protein de novo but also the synthesis of almost all other proteins was suppressed in the presence of ROS (Figure 5). Thus, it seems likely that ROS might inhibit the synthesis of most proteins in Synechocystis.

Translational initiation and elongation as the primary target of ROS

Northern blot analysis indicated that ROS had only a slight effect on the accumulation of psbA transcripts (Figure 6). Thus, since ROS inhibited the synthesis of pre-D1 de novo (Figures 5 and 7), it seemed likely that ROS might act primarily by inhibiting translation.

The distribution of psbA mRNAs (Figure 8) revealed that ROS markedly decreased the level of psbA mRNA–polysome complexes that were associated with thylakoid membranes. Recently, Tyystjärvi et al. (2001) demonstrated that, in Synechocystis, synthesis of the D1 protein de novo is regulated at the level of transcription of psbA genes and at the elongation step in the translation of psbA mRNA. The transcriptional machinery in Synecho cystis is different from that in chloroplasts. In the latter, the synthesis of D1 protein is redox-regulated at the initiation of the translation of psbA mRNA via binding of the nuclear-encoded protein complex to the 5′-untranslated region of psbA mRNA (Hirose and Sugiura, 1996; Yohn et al., 1996; Trebitsh et al., 2000)

In Synechocystis, psbA mRNAs associate first with ribosomes in the cytosol (translation initiation) and then elongation starts. After a 17-kDa nascent chain of the D1 protein has been synthesized, the psbA mRNA–ribosome complexes are targeted to thylakoid membranes where further elongation of the D1 protein occurs (Tyystjärvi et al., 2001). Our observations together with these observations suggest that the major sites of inhibition by ROS in our system are both initiation and elongation steps of translation. However, it remains possible that ROS might also inhibit the targeting of psbA mRNA–polysome complexes to thylakoid membranes.

Ayala et al. (1996) demonstrated that oxidative stress due to cumene hydroperoxide inhibits protein synthesis in rat liver by inactivating elongation factor 2, an important participant in the elongation step of translation. In Escherichia coli, H2O2 inactivates elongation via carbonylation of elongation factor G (Tamarit et al., 1998). Our results are consistent with these earlier findings.

Materials and methods

Cells and culture conditions

Wild-type Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and katG–/tpx– mutant cells were grown photoautotrophically (Gombos et al., 1994) at 34°C in BG-11 medium under light at 70 µmol photons/m2/s, with aeration by sterile air that contained 1% CO2. Cells at a density of 5 ± 0.5 µg/ml chlorophyll were used directly for studies of photodamage and repair.

Conditions for photodamage and repair, and measurements of photosynthetic activity

Cells were incubated in light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s (unless otherwise noted) to induce photodamage to PSII or in light at 70 µmol photons/m2/s to induce the repair of photodamaged PSII. These experiments were performed at 30°C at a concentration of cells that corresponded to 5 ± 0.5 µg/ml chlorophyll.

The activity of PSII was measured at 30°C by monitoring the photosynthetic evolution of oxygen, which was determined from the concentration of oxygen in a suspension of cells, measured with a Clark-type oxygen electrode in the presence of 1.0 mM 1,4-benzoquinone, as described previously (Gombos et al., 1994). Concentrations of chlorophyll were determined as described by Arnon et al. (1974).

Targeted mutagenesis

The nucleotide sequences of the katG and tpx genes of Synechocystis were obtained from the CyanoBase website [CyanoBase Website (Online) http://www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano/] Chromosomal DNA was extracted from Synechocystis cells, purified with ISOPLANT (Nippon Gene, Osaka, Japan), and used as template for amplification by PCR. A 2.26-kb fragment of DNA that contained the katG gene was amplified by PCR with primers 5′-TCATATGGGCACCCAACCCGCCAGG-3′ and 5′-AGATATCTAGCCCCTAGGGAGATCAAA-3′. The amplified fragment of DNA was ligated into the TA cloning vector pT7Blue-T (Novagen, Madison, WI). A plasmid with a disrupted katG gene was constructed by inserting a kanamycin-resistance gene cassette (Kmr; 1.2 kb) into the EcoO109I site of the katG gene in pT7Blue-T. The resultant plasmid was designated pKatG-Kmr. Wild-type Synechocystis cells were transformed with this plasmid to generate katG– cells as described elsewhere (Williams, 1988). Transformed cells were selected on agar-solidified BG-11 medium supplemented with 25 µg/ml kanamycin. To produce katG–/tpx– cells, katG– cells were transformed with pTPX-Spr/Smr, a plasmid with a disrupted tpx gene (Yamamoto et al., 1999), and transformed cells were selected on agar-solidified BG-11 medium supplemented with 30 µg/ml spectinomycin and 25 µg/ml kanamycin. Complete segregation of the katG and tpx genes in katG–/tpx– cells was confirmed by PCR with appropriate primers, as described elsewhere (Yamamoto et al., 1999).

Western blot analysis

Thylakoid membranes were isolated from wild-type cells that had been incubated in light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s for designated times, as described previously (Gombos et al., 1994). Proteins in isolated thylakoid membranes, equivalent to 0.63 µg of chlorophyll, were separated by SDS–PAGE on a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel that contained 6 M urea. Separated proteins were blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and allowed to react with a D1-specific antiserum that had been raised against a synthetic oligopeptide that corresponded to the AB loop of the D1 protein (amino acids 55–78, counted from the N-terminus) of Synechocystis or with a pre-D1-specific antiserum that had been raised against a synthetic oligopeptide that corresponded to the C-terminal extension of pre-D1, the precursor to the D1 protein of Synechocystis. Each band of immunologically reactive protein was detected with peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence western blot detection reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, UK). Levels of the D1 and pre-D1 proteins were determined densitometrically.

Labeling of proteins in vivo

Cell cultures were supplemented with 10 nM [35S]methionine (>1000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and then incubated at 30°C for designated times in light at 1.5 mmol photons/m2/s in the presence of the indicated reagents or in their absence (Sippola et al., 1998). Labeling was terminated by the addition of non-radioactive methionine to a final concentration of 1 mM and immediate cooling of samples on ice, and thylakoid membranes were isolated. After separation of proteins equivalent to 0.67 µg of chlorophyll by SDS–PAGE, as described above, labeled proteins on the gel were visualized by exposure of the dried and fixed gel to X-ray film. Levels of labeled D1 protein were determined densitometrically.

Northern blot analysis

Northern blot analysis was performed as described previously (Los et al., 1997). A 1.0-kb fragment of DNA that contained the coding region of the psbA2 gene was amplified by PCR with primers 5′-AACGACTCTCCAACAGCGCGAAA-3′ and 5′-CGTTCGTGCATTACTTCAAAACCG-3′. The amplified fragment of DNA was ligated into the TA cloning vector pT7Blue-T. The plasmid was digested at the HincII and NcoI sites within the insert. The resultant 700-bp fragment of DNA was conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Alkphos Direct kit; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and the conjugate was used as the probe for northern blot analysis. After hybridization, the blot was soaked in CDP-star solution (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and signals from hybridized mRNA were detected with a luminescence image analyzer (LAS-1000; Fuji-Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Isolation of polysomes

Polysomes were isolated from wild-type Synechocystis cells as described by Tyystjärvi et al. (2001) with minor modifications. Subsequent procedures were performed at 0–4°C. Cells equivalent to 125 µg of chlorophyll were first washed with a buffer that contained 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 400 mM sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2, 30 mM EDTA and 500 µg/ml chloramphenicol, and then they were washed with medium A, which contained 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 400 mM sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2 and 500 µg/ml chloramphenicol. Cells were suspended in 200 µl of medium A that had been supplemented with 200 units of ribonuclease inhibitor (SUPERase·In; Ambion, Austin, TX) and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Complete, Mini, EDTA-free; Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The suspension was homogenized with an equal volume of zirconia silica beads (diameter, 0.1 mm; BioSpec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, USA) on a vortex mixer which was operated at maximum speed for 3 min with five interruptions of 30 s each on ice. After addition of 700 µl of medium B, which was the same as medium A except that it was prepared without sucrose, the homogenate was centrifuged at 650 g for 5 min to remove unbroken cells and cell debris. The resultant supernatant was centrifuged at 18 000 g for 20 min to yield a membrane fraction (the pellet) and a cytosolic fraction (the supernatant).

The pelleted membranes were resuspended in 700 µl of medium B and then Tween-20 was added to a final concentration of 2% (v/v). The cytosolic fraction (900 µl) was also supplemented with 2% Tween-20. After incubation for 10 min on ice, insoluble materials were removed from these fractions by centrifugation at 18 000 g for 5 min. The resultant supernatants were further centrifuged at 270 000 g for 1 h, on a cushion of 300 µl of a solution that contained 1 M sucrose, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 10 mM MgCl2 and 500 µg/ml chloramphenicol, for collection of polysomes as the pellet. The supernatant from the cytosolic fraction was used for northern blot analysis of free RNAs. RNAs were isolated from the polysome and free-RNA fractions as described previously (Los et al., 1997) and dissolved in 50 µl of H2O. Two-microliter aliquots of the solutions were subjected to northern blot analysis as described above.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Kimiyuki Satoh (Okayama University) for the antiserum against the AB loop of the D1 protein. This work was supported, in part, by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (No. 13854002) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan, to N.M.

References

- Ananyev G., Wydrzynski,T., Renger,G. and Klimov,V. (1992) Transient peroxide formation by the manganese-containing, redox-active donor side of photosystem II upon inhibition of O2 evolution with lauroylcholine chloride. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1100, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson B. and Barber,J. (1996) Mechanisms of photodamage and protein degradation during photoinhibition of photosystem II. In Baker,N.R. (ed.), Photosynthesis and the Environment. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 101–121.

- Arnon D.I., McSwain,B.D, Tsujimoto,H.Y. and Wada,K. (1974) Photochemical activity and components of membrane preparations from blue-green algae. I. Coexistence of two photosystems in relation to chlorophyll a and removal of phycocyanin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 357, 231–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro E.-M., Virgin,I. and Andersson,B. (1993) Photoinhibition of photosystem II. Inactivation, protein damage and turnover. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1143, 113–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. (1996) Radical production and scavenging in the chloroplasts. In Baker,N.R. (ed.), Photosynthesis and the Environment. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 123–150.

- Asada K. (1999) The water–water cycle in chloroplasts: scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol., 50, 601–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala A., Parrado,J., Bougria,M. and Machado,A. (1996) Effect of oxidative stress, produced by cumene hydroperoxide, on the various steps of protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 23105–23110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber J. and Andersson,B. (1992) Too much of a good thing: light can be bad for photosynthesis. Trends Biochem. Sci., 17, 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.-X., Kazimir,J. and Cheniae,G.M. (1992) Photoinhibition of hydroxylamine-extracted photosystem II membranes: studies of the mechanism. Biochemistry, 31, 11072–11083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gombos Z., Wada,H. and Murata,N. (1994) The recovery of photosynthesis from low-temperature photoinhibition is accelerated by the unsaturation of membrane lipids: a mechanism of chilling tolerance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 8787–8791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. and Gutteridge,J.M.C. (1990) Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: an overview. Methods Enzymol., 186, 1–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hideg E., Spetea,C. and Vass,I. (1994) Singlet oxygen and free radical production during acceptor- and donor-side-induced photoinhibition. Studies with spin trapping EPR spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1186, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T. and Sugiura,M. (1996) Cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors for accurate translation of chloroplast psbA mRNAs: development of an in vitro translation system from tobacco chloroplasts. EMBO J., 15, 1687–1695. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson C., Debus,R.J., Osiewacz,H.D., Gurevitz,M. and McIntosh,L. (1987) Construction of an obligate photoheterotrophic mutant of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Inactivation of the psbA gene family. Plant Physiol., 85, 1021–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komenda J. and Barber,J. (1995) Comparison of psbO and psbH deletion mutants of Synechocystis PCC 6803 indicates that degradation of D1 protein is regulated by the QB site and dependent on protein synthesis. Biochemistry, 34, 9625–9631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S.P., Humphries,S. and Falkowski,P.G. (1994) Photoinhibition of photosynthesis in nature. Annu. Rev.Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol., 45, 633–662. [Google Scholar]

- Los D.A., Ray,M. and Murata,N. (1997) Differences in the control of the temperature-dependent expression of four genes for desaturases in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Mol. Microbiol., 25, 1167–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyao M., Ikeuchi,M., Yamamoto,N. and Ono,T. (1995) Specific degradation of the D1 protein of photosystem II by treatment with hydrogen peroxide in darkness: implication for the mechanism of degradation of the D1 protein under illumination. Biochemistry, 34, 10019–10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K., Ikeuchi,M., Yamamoto,N., Ono,T. and Miyao,M. (1996) Selective and specific cleavage of the D1 and D2 proteins of photosystem II by exposure to singlet oxygen: factors responsible for the susceptibility to cleavage of the proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1274, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Prásil O., Adir,N. and Ohad,I. (1992) Dynamics of photosystem II: mechanism of photoinhibition and recovery processes. In Barber,J. (ed.), Topics in Photosynthesis, Vol. 11, The Photosystems: Structure, Function and Molecular Biology. Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam, pp. 295–348.

- Sippola K., Kanervo,E., Murata,N. and Aro,E.-M. (1998) A genetically engineered increase in fatty acid unsaturation in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 allows exchange of D1 protein forms and sustenance of photosystem II activity at low temperature. Eur. J. Biochem., 251, 641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamarit J., Cabiscol,E. and Ros,J. (1998) Identification of the major oxidatively damaged proteins in Escherichia coli cells exposed to oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 3027–3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer A., Bishop,S.M., Phillips,D. and Barber,J. (1994) The isolated photosynthetic reaction center of PS II as a sensitiser for the formation of singlet oxygen; detection and quantum yield determination using a chemical trapping technique. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 13244–13253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tichy M. and Vermaas,W. (1999) In vivo role of catalase-peroxidase in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol., 181, 1875–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebitsh T., Levitan,A., Sofer,A. and Danon,A. (2000) Translation of chloroplast psbA mRNA is modulated in the light by counteracting oxidizing and reducing activities. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 1116–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyystjärvi T., Tyystjärvi,E, Ohad,I. and Aro,E.-M. (1998) Exposure of Synechocystis 6803 cells to series of single turnover flashes increases the psbA transcript level by activating transcription and down-regulating psbA mRNA degradation. FEBS Lett., 436, 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyystjärvi T., Herranen,M. and Aro,E.-M. (2001) Regulation of translation elongation in cyanobacteria: membrane targeting of the ribosome nascent-chain complexes controls the synthesis of D1 protein. Mol. Microbiol., 40, 476–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vass I., Styring,S., Hundal,T., Koivuniemi,A., Aro,E.-M. and Andersson,B. (1992) The reversible and irreversible intermediates during photoinhibition of photosystem II—stable reduced QA species promote chlorophyll triplet formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 1408–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J.G.K. (1988) Construction of specific mutations in photosystem II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic engineering methods in Synechocystis PCC6803. Methods Enzymol., 167, 766–778. [Google Scholar]

- Wise R.R. (1995) Chilling-enhanced photooxidation: the production, action and study of reactive oxygen species produced during chilling in the light. Photosynth. Res., 45, 79–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto H., Miyake,C., Dietz,K.-J., Tomizawa,K., Murata,N. and Yokota,A. (1999) Thioredoxin peroxidase in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett., 447, 269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohn C.B., Cohen,A., Danon,A. and Mayfield,S.P. (1996) Altered mRNA binding activity and decreased translation initiation in a nuclear mutant lacking translation of the chloroplast psbA mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 3560–3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]