Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has been traditionally viewed as a toxic gas. It is also, however, endogenously generated from cysteine metabolism. We attempted to assess the physiological role of H2S in the regulation of vascular contractility, the modulation of H2S production in vascular tissues, and the underlying mechanisms. Intravenous bolus injection of H2S transiently decreased blood pressure of rats by 12– 30 mmHg, which was antagonized by prior blockade of KATP channels. H2S relaxed rat aortic tissues in vitro in a KATP channel-dependent manner. In isolated vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), H2S directly increased KATP channel currents and hyperpolarized membrane. The expression of H2S-generating enzyme was identified in vascular SMCs, but not in endothelium. The endogenous production of H2S from different vascular tissues was also directly measured with the abundant level in the order of tail artery, aorta and mesenteric artery. Most importantly, H2S production from vascular tissues was enhanced by nitric oxide. Our results demonstrate that H2S is an important endogenous vasoactive factor and the first identified gaseous opener of KATP channels in vascular SMCs.

Keywords: blood pressure/hydrogen sulfide/nitric oxide/smooth muscle cells/vasorelaxation

Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has been best known for decades as the toxic gas dubbed ‘gas of rotten eggs’ (Winder and Winder, 1933; Smith and Gosselin, 1979). Less recognized, however, is the fact that H2S is also a biological gas endogenously generated from cysteine in a reaction catalysed by cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and/or cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) (Stipanuk and Beck, 1982; Hosoki et al., 1997). By analogy to other endogenous gaseous molecules, such as nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO) (Wang et al., 1997a, b), H2S was hypothesized to fulfil a physiological role in regulating cardiovascular functions, distinctive from its toxicological effect. In line with this idea was the study showing that H2S, at physiological concentrations, facilitated the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation (Abe and Kimura, 1996). To date, the cardiovascular effects of both endogenous and exogenous H2S have not been fully understood. Hosoki et al. (1997) demonstrated that H2S relaxed rat aortic tissues in vitro. However, the cellular mechanisms for this vascular effect of H2S, as well as its physiological significance, remained to be examined. Does H2S affect the cardiovascular function in vivo of whole animal or in vitro at the cellular level? Do the cardiovascular effects of H2S have physiological significance? NO and CO mediate vasorelaxation by increasing the cellular cGMP activity and/or stimulating KCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Does H2S also act on these cellular targets? NO and CO can be released from both SMCs and endothelial cells. Is H2S synthesized in SMCs or endothelial cells or both? Once released, NO and CO act directly on SMCs independent of endothelium. Is the vascular effect of H2S mediated by endothelium? The endogenous stimuli for the synthesis and release of NO and CO have been identified. What are the endogenous regulators of H2S synthesis and release? Answers to these questions will not only help to establish the role of H2S as another endogenous gaseous vasoactive factor, but also provide novel mechanisms for the fine regulation of vascular tone.

The purpose of the present study was to assess the physiological role of H2S in the regulation of cardiovascular functions, the modulation of H2S production in vascular tissues, and the underlying mechanisms. The vasoactive effects of H2S were investigated by measuring the blood pressure change of rats in vivo, vascular tension development in vitro and K+ channel currents in isolated vascular SMCs. Molecular biology and biochemistry techniques were used to detect the expression of H2S-generating enzymes and the endogenous levels of H2S. Our study indicates that H2S is an endogenous vasorelaxant factor that activates KATP channels and hyperpolarizes membrane potential of vascular SMCs.

Results

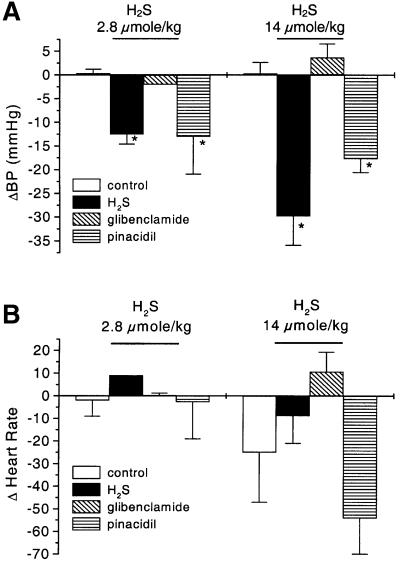

The cardiovascular effects of H2S in vivo

An intravenous bolus injection of H2S at 2.8 and 14 µmol/kg body weight provoked a transient (29.5 ± 3.6 s) decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of anaesthetized rats by 12.5 ± 2.1 and 29.8 ± 7.6 mm Hg, respectively (n = 3 for each group, P < 0.05) (Figure 1A). Heart rate was not altered by H2S injection (Figure 1B). An 18 ± 3 mm Hg decrease of blood pressure was also observed after a bolus intravenous injection of a KATP channel opener pinacidil (2.8 µmol/kg) (n = 3, P < 0.01), mimicking the hypotensive effect of H2S. Although a bolus intravenous or intraperitoneal injection of glibenclamide (a KATP channel blocker) at 2.8 µmol/kg did not alter mean blood pressure (106 ± 2.3 mm Hg compared with 109 ± 8.2 mm Hg, P > 0.05, n = 3), pretreatment of animals for 20 min with glibenclamide significantly reduced by 83% the hypotensive effect of H2S (n = 3, P < 0.05). Prior injection of vehicle used for preparing glibenclamide did not alter the hypotensive effect of H2S (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1. The effect of H2S in vivo on mean arterial blood pressure (BP) and heart rate of rats. (A) Intravenous injection of H2S induced significant decrease in BP. This effect was mimicked by intravenous injection of pinacidil (2.8 µmol/kg) and antagonized by a prior intravenous injection of glibenclamide (2.8 µmol/kg). (B) Effect of H2S on rat heart rate. Heart rate was recorded 30 s after intravenous injection of PBS (control), H2S or pinacidil. *P < 0.05 compared with control.

Characterization of the H2S-induced vasorelaxation

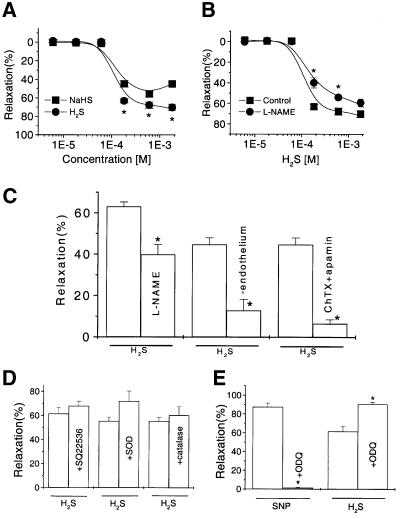

Unless otherwise stated, each experiment shown in this section was composed of eight aortic rings. H2S induced a concentration-dependent relaxation of the phenylephrine (PHE)-precontracted rat aortic tissues (IC50, 125 ± 14 µM) (Figure 2A). For instance, at a concentration of 180 µM, H2S relaxed the tissue by 63 ± 2.2% (P < 0.05). A positive cooperativity for H2S in operating its acting sites on vascular smooth muscles was evidenced by the calculated Hill coefficient of 4.9 (Ruiz et al., 1999). Pretreatment of the endothelium-intact tissues with l-NAME (NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, 100 µM) to block endogenous NO production from endothelium shifted the H2S concentration-dependent relaxation curve to the right with IC50 changed to 220 ± 12 µM (P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained by just removing endothelium from the aortic tissues (Figure 2C). Moreover, co-application of charybdotoxin (50 nM) and apamin (50 nM) to the endothelium-intact tissues reduced the H2S-induced vasorelaxation (Figure 2C).

Fig. 2. The H2S-induced relaxation of rat aortic rings and the underlying mechanisms. (A) Relaxation of the PHE-precontracted tissues by H2S in the form of either standard NaHS solution (square) or H2S gas-saturated solution (circle). (B) Inhibitory effect of l-NAME (100 µM, 20 min, circle) on the H2S-induced relaxation (control, square). (C) The effects of H2S (180 µM) on the endothelium-free or endothelium-intact aortic tissues pretreated with l-NAME or charybdotoxin (ChTX)/apamin. (D) The relaxant effect of H2S was not affected by pretreating the tissues with SQ22536, SOD or catalase, respectively. (E) The effect of ODQ treatment (10 µM for 10 min) on the relaxant effects of SNP (0.1 µM) or H2S (600 µM). n = 8 for each data point. *P < 0.05 compared with control.

Further studies were carried out to identify the involvement of various signal transduction pathways in the vascular effect of H2S. Treatment of tissues with indomethacin (10 µM, not shown) (Rodriguez-Martinez et al., 1998) or staurosporine (30 nM, not shown) (Hattori et al., 1995; Huang, 1996) or SQ22536 (100 µM) (Talpain et al., 1995) did not change the effect of H2S (Figure 2D), disapproving the involvement of prostaglandin, protein kinase C or cAMP pathways, respectively. The generation of superoxide anion or hydrogen peroxide by H2S (Nicholls, 1961) was unlikely responsible for the H2S-induced vasorelaxation since the inclusion of superoxide dismutase (SOD, 160 U/ml) and catalase (1000 U/ml) (Rodriguez-Martinez et al., 1998) failed to alter the effect of H2S (Figure 2D). The vasorelaxation induced by sodium nitroprusside (SNP), a NO donor, was virtually abolished by the specific inhibitor of the soluble guanylyl cyclase, 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3,-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ). However, the vasorelaxant effect of H2S was not blocked by ODQ (Figure 2E). Clearly, the vasorelaxant effect of H2S was not mediated by the cGMP pathway.

Involvement of K+ channel activities in the H2S-induced vasorelaxation

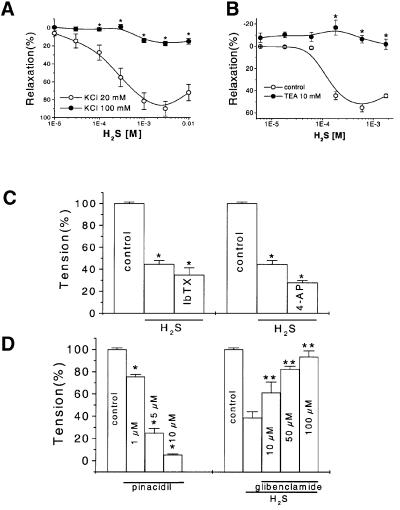

Different relaxation potencies of H2S on vascular tissues precontracted by high or low concentration of KCl. To examine whether the H2S-induced vasorelaxation was mediated by the increased potassium conductance, aortic rings were precontracted with either 20 or 100 mM KCl and the vasorelaxant effect of H2S was then examined. The contraction forces induced by 20 and 100 mM KCl were 0.86 ± 0.08 and 1.58 ± 0.08 g, respectively. In general, H2S induced a greater relaxation of the vascular tissues precontracted by low concentration of KCl (20 mM) than by PHE. For instance, the threshold concentrations of H2S to initiate relaxation were 18 and 60 µM for 20 mM KCl- and PHE-precontracted tissues, respectively. The maximum vascular relaxation induced by H2S was 90 ± 8.2% or 19 ± 3.9% when the tissues were precontracted with 20 or 100 mM KCl, respectively (Figure 3A). This difference in the relaxation potency of H2S represents the portion of relaxation possibly mediated by potassium conductance.

Fig. 3. The K+ channel-mediated vascular effects of H2S. (A) The relaxant effect of H2S on the aortic tissues precontracted with 20 or 100 mM KCl. (B) Inhibitory effect of TEA on the H2S-induced vasorelaxation. The concentration-dependent vasorelaxant effects of H2S with or without TEA (10 mM) pretreatment of aortic rings were determined. (C) The H2S (600 µM)-induced vasorelaxation was not affected by pretreatment of aortic tissues with either 10 µM iberiotoxin (IbTX) or 2.5 mM 4-aminopyridine (4-AP). *P < 0.05 compared with control, n = 8. (D) The vasoactive effects of pinacidil (left) and H2S (right) on the precontracted aortic tissues. The vasorelaxant effect of H2S (600 µM) was examined in the presence of glibenclamide at different concentrations. *P < 0.05 compared with control, **P < 0.05 compared with the H2S group in the absence of glibenclamide, n = 8.

Involvement of KCa channels in the vascular effects of H2S. In order to identify the role of specific types of K+ channels in the H2S-induced relaxation, aortic rings were incubated with either 10 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA), 100 nM charybdotoxin or 100 nM iberiotoxin (IbTX) (two specific KCa channel inhibitors) for 20 min prior to the application of H2S. In the presence of TEA, the H2S-induced vasorelaxation was completely inhibited (Figure 3B). At this high concentration, TEA is known to block many different types of K+ channels (Nelson and Quayle, 1995). The H2S-induced vasorelaxation was not affected by iberiotoxin (Figure 3C) or charybdotoxin (not shown), suggesting that big-conductance KCa channels might not be responsible for the H2S-induced vasorelaxation.

Involvement of voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) channels in the vascular effects of H2S. A previous study has shown that 4-AP specifically inhibited the Kv channel with an IC50 of 1.4 mM (Remillard and Leblanc, 1996). In the present study, 2.5 mM 4-AP was used to treat vascular tissues 20 min before the application of H2S. The relaxant effect of H2S was not affected by 4-AP, eliminating the involvement of Kv channels (Figure 3C).

Involvement of KATP channels in the vascular effects of H2S. To elucidate whether an ATP-sensitive K+ channel (KATP) was the target of H2S, the interaction of H2S with known KATP channel modulators was examined. The H2S-induced vasorelaxation was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by glibenclamide (IC50, 140 µM) (Figure 3D). The H2S effect was also mimicked by pinacidil that relaxed the PHE-precontracted vascular tissues in a concentration-dependent manner (IC50, 2.4 µM) (Figure 3D).

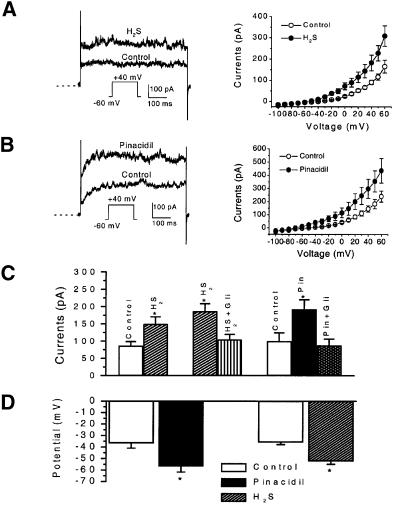

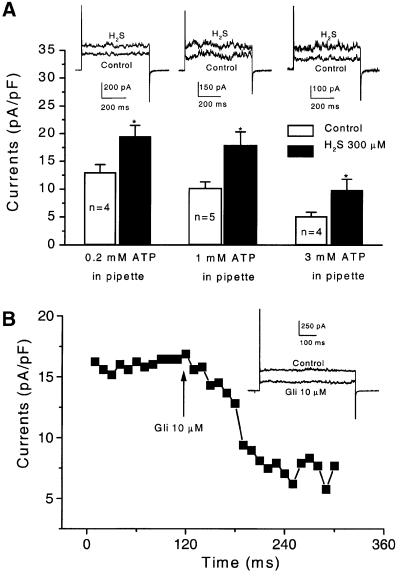

The direct effect of H2S on KATP channel currents and membrane potential in single vascular SMCs

After exposure to 300 µM H2S, KATP channel currents in rat aortic SMCs were significantly increased in amplitude (Figure 4A). This excitatory effect of H2S was fully manifested 3 min after the application and nullified immediately after washing out H2S from the bath solution. Pinacidil (5 µM) also increased KATP channel currents, similar to the effect of H2S (Figure 4B). The effects of H2S and pinacidil on KATP channel currents were observed in a wide test potential range (–40 to +60 mV). The reversal potential of KATP channels in these cells was not altered by either H2S or pinacidil (Figure 4A and B, right panels).

Fig. 4. The effect of H2S and pinacidil on KATP channel currents in rat aortic SMCs. (A) The effect of H2S on KATP channel currents. The original records from one cell (left) and the mean current–voltage relationship of six cells (right) in the absence and then presence of H2S (300 µM) are shown. (B) The effect of pinacidil (5 µM) on KATP channel currents. The original records from one cell (left) and the mean current–voltage relationship of five cells (right) in the absence and then presence of pinacidil are shown. Dashed line indicates zero current level. (C) The antagonistic effect of glibenclamide (Gli, 5 µM) on the effect of H2S or pinacidil (Pin) on KATP channel currents (holding potential, –60 mV; test potential, +40 mV). (D) The membrane hyperpolarization induced by H2S (300 µM) or pinacidil (5 µM), respectively. *P < 0.05 compared with control; n = 3–7 for each group.

On average, H2S (300 µM) and pinacidil (5 µM) increased KATP channel currents from 85.8 ± 12.4 to 149.0 ± 21.4 pA and from 99.1 ± 5.1 to 191.8 ± 28.1 pA (test potential, +40 mV), respectively (Figure 4C). Increased KATP channel currents by H2S would lead to membrane hyperpolarization, resulting in smooth muscle relaxation. This hypothesis was tested by directly measuring membrane potential change using the conventional whole-cell patch–clamp technique and the results are shown in Figure 4D. After exposing SMCs to H2S (300 µM) or pinacidil (5 µM), the cell membrane was hyperpolarized from –35.7 ± 2.0 to –53.3 ± 2.5 mV or from –36.6 ± 4.5 to –56.7 ± 5.0 mV, respectively. The hyperpolarization developed within 3 min of the application of H2S or pinacidil. Glibenclamide (5 µM) alone had no effect on resting membrane potential (n = 6). The hyperpolarization induced by H2S or pinacidil was reversed to the control level 3–5 min after the subsequently applied glibenclamide to the same cells (n = 5). Using the perforated whole-cell recording technique, we also found that H2S (300 µM) significantly hyperpolarized the resting membrane potential from –51.2 ± 6.5 to –69.2 ± 7.6 mV (n = 6, P < 0.05). It may be argued that the increase in KATP channel currents in the presence of H2S resulted from the interfered ATP metabolism by H2S. However, the reversibility of H2S effect was not in favour of this argument. Moreover, in the aforementioned experiments, the cells were dialysed with the pipette solution that contained a pre-determined ATP concentration, i.e. 0.5 mM. In another set of experiments, the concentrations of ATP in the pipette solution were intentionally altered (Figure 5A). Similar KATP current densities were observed in the cells with 0.2 or 1 mM ATP in the pipette solution. The excitatory effect of H2S on KATP currents was not altered by changing intracellular ATP concentrations within this range (P > 0.05). In the presence of 3 mM ATP in the pipette solution, however, the KATP current density was significantly smaller (5.1 ± 0.7 pA/pF) than that with 0.2–1 mM ATP (P < 0.05). The increase in KATP channel currents induced by H2S was also significantly decreased in the presence of 3 mM ATP (49.7 ± 2.7% increase) as compared with the effect of H2S in the presence of 0.2 mM ATP (87.3 ± 12.2% increase) (P < 0.05) (Figure 5A). Furthermore, pinacidil (5 µM) increased the KATP currents in aortic SMCs by 72.4 ± 10.5% (n = 5, P < 0.05 compared with control) or 107.6 ± 32.2% (n = 5, P < 0.05 compared with control) in the presence of 0.2 or 1 mM ATP in the pipette solution, respectively (P > 0.05 between the effects of pinacidil at the two ATP concentrations). In the presence of 3 mM ATP in the pipette solution, pinacidil (5 µM) increased KATP currents by 44.7 ± 4.9% (n = 4, P < 0.05), which was significantly smaller than the effect of pinacidil at 0.2 or 1 mM ATP (P < 0.05). These results demonstrated a low ATP sensitivity of the KATP channels in the examined vascular SMCs and revealed that the effect of KATP channel openers was reduced in the presence of high intracellular ATP concentrations (Quayle et al., 1995).

Fig. 5. The modulation of KATP channel currents by H2S with different intracellular ATP concentrations and by glibenclamide (Gli) in rat aortic SMCs. (A) The ATP-dependence of the H2S (300 µM)-induced increases in KATP channel currents. Holding potential, –60 mV; test potential, +40 mV. *P < 0.05 compared with control. (B) The time course of the inhibition of KATP currents by glibenclamide. Aortic SMCs were dialysed with 0.2 mM ATP and 1 mM GDP. The voltage pulses of +30 mV were applied from a holding potential of –60 mV. Inset shows the representative of original current traces before and after the application of 10 µM glibenclamide.

To further characterize the KATP channels in these cells, the effect of glibenclamide was studied. The H2S-stimulated or pinacidil-stimulated KATP channel currents were significantly reduced by glibenclamide (5 µM, n = 6 for each group) to the control level (Figure 4C). Glibenclamide per se did not change the basal KATP channel current under our recording conditions (5.4 mM KCl in the bath solution and 0.5 mM ATP in the pipette solution) (n = 5, P > 0.05). In the presence of 1 mM GDP in the pipette solution containing 0.2 mM ATP, the basal KATP current density was significantly increased to 22.3 ± 4.9 pA/pF (n = 8) in comparison with the KATP current density of 13.0 ± 1.4 pA/pF recorded in the absence of GDP and presence of 0.2 mM ATP in the pipette solution (n = 4) (test potential, +40 mV; P < 0.05). Under this modified condition, glibenclamide reduced the basal KATP current density by 47.3 ± 9.2% (n = 8, test potential at +40 mV, P < 0.01) (Figure 5B).

The identification, differential expression and cloning of the H2S-generating enzymes in vascular tissues

To corroborate the physiological importance of the vasorelaxant effect of H2S, the endogenous sources of H2S were determined in vascular tissues. Using RT–PCR, a PCR-amplified 234 bp fragment of CSE, but not CBS (not shown), was detected in endothelium-free rat pulmonary artery, mesenteric artery, tail artery and aorta as well as rat liver (Figure 6A). To ascertain that the amplified PCR product was free of genomic DNA contamination, every RNA sample was simultaneously amplified by PCR without reverse transcriptase treatment. Under these conditions, no PCR product was detected. The gel-purified PCR products of CSE from rat liver and vascular tissues were ligated with a synthesized deoxyooligonucleotide (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) that contains the phage T7 promoter sequence and then sequenced manually using T7 primer. The sequences of our PCR-amplified CSE fragments from rat arteries matched the corresponding CSE sequence cloned from rat liver (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. X53460), demonstrating that the same isoform of CSE gene was expressed in rat vascular tissues and liver. RNase protection assay revealed the abundant levels of CSE mRNA in different vascular tissues with an intensity rank of pulmonary artery, aorta, tail artery and mesenteric artery (Figure 6B). Due to the lack of commercially available antibodies against CSE, the protein levels of CSE in vascular tissues were not examined.

Fig. 6. Differential expression of CSE in rat vascular tissues. (A) RT–PCR analysis of the expression of CSE (234 bp) in rat liver, mesenteric artery, tail artery, pulmonary artery and aorta. (B) Quantitative comparison of CSE mRNA levels in rat tail artery, mesenteric artery, pulmonary artery and aorta with RPA. This is representative of three experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with mesenteric artery; **P < 0.01 compared with tail artery, mesenteric artery and aorta. A, artery. (C) The transcriptional expressions of CSE and β-actin in cultured SMCs and EC (endothelial cell) detected by RT–PCR. (D) In situ hybridization showing the location of CSE mRNA in rat aorta wall by antisense probe on the left and sense probe as control on the right.

The differential expression of CSE between vascular SMCs and endothelial cells was studied further. Using RT–PCR, a 1123 bp fragment of CSE was detected in cultured rat aortic SMCs, but not in cultured vascular endothelial cells (Figure 6C). In situ hybridization was applied to further locate CSE mRNA in the aortic wall. The expression of CSE mRNA was clearly identified in the smooth muscle layer of the artery wall, but not in the endothelial layer (Figure 6D, left panel). To exclude the non-specific staining, the sense probe for CSE was used to hybridize rat aortic tissues under the same condition as for the antisense probe. Figure 6D (right panel) shows that no positive staining could be spotted using the sense probe for CSE.

Finally, a PCR-based cloning technique was used with a pair of primers covering the translation initiation and termination codons of CSE to obtain a cDNA clone encoding the whole open reading frame (ORF) region of CSE. The PCR-amplified product of ∼1300 bp was detected in rat aorta, tail artery and mesenteric artery. We have cloned and sequenced two isoforms of CSE from rat mesenteric arteries, which contained an ORF of 1197 bp, encoding a 398 amino acid peptide. We further cloned and sequenced CSE from rat liver and found no differences among all the clones from artery and liver. The sequence data of our cloned rat vascular CSE and liver CSE have been submitted to GenBank (AB052882 and AY032875).

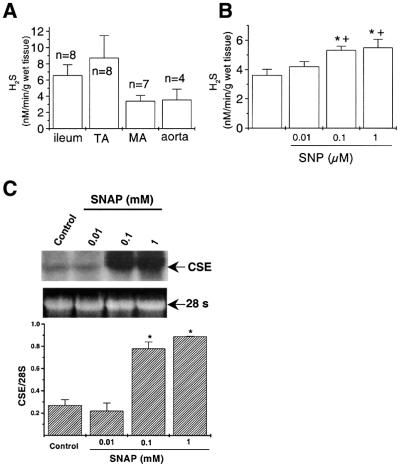

The endogenous level of H2S and its regulation

The physiological role of H2S could not be established before the endogenous level of this gas in vascular tissues or in circulation had been determined. Thus, the endogenous production of H2S in vascular tissues and in circulation was assayed. Figure 7A showed that various vascular tissues produced different levels of H2S. When the specific inhibitor of CSE, dl-propargylglycine, was added to the reaction medium at the final concentration of 20 mM (Hosoki et al., 1997), H2S production was completely abolished in all tested arteries (n = 3), indicating that the generation of H2S from vascular tissues was due to the specific catalytic activity of CSE. Using a modified sulfide electrode method, the H2S concentration of rat serum was determined to be 45.6 ± 14.2 µM (n = 4).

Fig. 7. Regulation of the endogenous H2S production in different rat tissues. (A) Accumulated endogenous H2S levels in rat tail artery (TA), mesenteric artery (MA), aorta and ileum. (B) H2S production rate of aorta tissues was stimulated by SNP in a concentration-dependent manner. *P < 0.05 compared with control, n = 3. (C) The SNAP-induced concentration-dependent upregulation of CSE transcriptional expression in cultured aortic SMCs, determined using northern blotting. The 28S ribosome RNA was assayed as the housekeeping control. n = 3, *P < 0.05 compared with control.

The effect of NO on the endogenous production of H2S was examined by incubating homogenized rat vascular tissues with different concentrations of SNP, a NO donor, for 90 min. An accumulated H2S production was upregulated by SNP in a concentration-dependent manner (1–100 µM) (Figure 7B). Nitric oxide has been shown to regulate protein expression and synthesis, including growth factors, leukocyte adhesive proteins and extracellular matrix proteins (Kourembanas et al., 1993; Kolpakov et al., 1995; Zeiher et al., 1995). In our study, incubating the cultured vascular SMCs with SNAP (0.1 or 1 mM), another NO donor, for 6 h significantly increased the transcriptional level of CSE (Figure 7C).

Discussion

In the present study, the cardiovascular effects of H2S were demonstrated in vivo and in vitro. Intravenous injection of H2S provoked a transient but significant decrease in mean arterial blood pressure. Similar to our in vitro vascular contractility assay and patch–clamp studies, the H2S-induced decrease in blood pressure was antagonized by glibenclamide and mimicked by pinacidil. Glibenclamide and pinacidil are specific KATP channel blocker and opener, respectively (Beech et al., 1993; Quayle et al., 1994). Thus, these in vivo results indicated that the hypotensive effect of H2S was likely provoked by the relaxation of resistance blood vessels through the opening of KATP channels. The short duration of the hypo tensive effect of H2S could be attributed to the scavenging of H2S by metalloproteins, disulfide-containing proteins, thio-S-methyl-transferase and haem compounds. The administration of H2S as a bolus injection also partially explains the transient effect. Similarly, the hypotensive effect of pinacidil was also transient. Furthermore, our data showed that the in vivo hypotensive effect of H2S was due to a specific action on vascular smooth muscles, since heart rate was not significantly affected. Our in vitro study showed that H2S relaxed the isolated aortic tissues at concentrations as low as 18 and 60 µM for the aortic tissues precontracted with either 20 mM KCl or PHE, respectively. It has been reported that the normal blood level of H2S in Wistar rats was ∼10 µM (Mason et al., 1978). Our study demonstrated that the plasma level of H2S in SD rats was ∼50 µM. The tissue level of H2S is known to be higher than the circulating level. For instance, the physiological concentration of H2S in brain tissue has been reported to be ∼50–160 µM (Hosoki et al., 1997). Taken together, H2S is believed to induce vasorelaxation within a physiologically relevant concentration range. These findings strongly suggest that, similar to NO and CO, H2S is another intrinsic vasoactive gas factor.

The physiological role of H2S in the cardiovascular system was further substantiated by its endogenous sources and regulated production process. Using RT– PCR, RPA and northern blotting, we detected the transcriptional expression of the H2S-generating enzyme CSE in all rat arteries tested. The whole sequence of the ORF of CSE had been cloned in this study from rat vascular tissues, which had not been done in any vascular tissues from any species until the present study. CSE has the capability to cleave l-cysteine to produce H2S, ammonium and pyruvate. This enzyme has a unique tissue distribution and was not detectable in brain and lungs (Smith and Gosselin, 1979; Abe and Kimura, 1996).

Akin to the release of NO from endothelium by acetylcholine, the regulation of H2S production by other endogenous substances is an essential piece of evidence for establishing the physiological role of H2S. We showed for the first time that NO regulates the endogenous levels of H2S in vascular tissues via two mechanisms. First, NO increases CSE activity in vascular tissues. Incubating aortic tissue homogenate with a NO donor for 90 min significantly increased H2S generation in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 7B). NO may increase the activity of cGMP-dependent protein kinases, which in turn stimulates CSE. It is also possible that NO directly acts on CSE protein. Rat mesenteric artery CSE protein contains 12 cysteines that are the potential substrate of S-nitrosylation. Currently, the three-dimensional structure of CSE is unknown and which cysteine contains free -SH group cannot yet be assured. However, the nitrosylation of certain free -SH group of CSE in the presence of NO does represent a possibility (Stamler et al., 1997; Broillet, 1999). Secondly, NO upregulates the expression of CSE. Incubating cultured vascular SMCs with a NO donor for 6 h significantly increased the expression level of CSE (Figure 7C). The mechanism by which NO increased CSE transcription is not yet clear.

Unlike NO, which can be produced from both endothelial cells and SMCs, H2S is only generated from SMCs since no H2S-generating enzyme was expressed in vascular endothelium according to our in situ hybridization and RT–PCR studies. Although a previous study claimed that the relaxation of aortic tissues by H2S was not endothelium dependent, the data to support this claim and the procedure to remove endothelium were not presented in that report (Hosoki et al., 1997). Our study demonstrated that a small portion of the vasorelaxant effect of H2S was indeed potentiated by endothelium (Figure 2B and C). This indicated that H2S might act as a hyperpolarizing factor, of which the effect was amplified by endothelium. Alternatively, endothelium-derived vasorelaxant factors might have been released by H2S as both l-NAME and the co-application of charybdotoxin and apamin to the endothelium-intact tissues, a treatment reported to inhibit the effect of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (Doughty et al., 1999), reduced the H2S-induced vasorelaxation. Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that H2S acts on both vascular SMCs and endothelial cells with distinctive mechanisms.

Our data did not support the mediation of the H2S-induced vasorelaxation by prostaglandin, protein kinase C, cAMP or cGMP pathways. Meanwhile, the modulation of K+ channels in general, and the KATP channel in particular, in vascular SMCs by H2S gained ground from several lines of evidence. (i) H2S effectively relaxed aortic tissues precontracted by 20 mM KCl, but not so when tissues were precontracted by 100 mM KCl. (ii) The H2S-induced vasorelaxation was inhibited by high concentrations of TEA that blocked many K+ channels in vascular SMCs, including KCa, Kv and KATP channels. Interestingly, different blockers for KCa or Kv channels failed to affect the vascular effects of H2S (Nelson and Quayle, 1995), leaving the KATP channel as the most likely candidate target of H2S. (iii) Pinacidil relaxed aortic tissues, showing the active role of KATP channels in regulating vascular tone. (iv) Glibenclamide inhibited the H2S-induced vasorelaxation, showing indirectly the interaction of H2S and KATP channels. (v) Both pinacidil and H2S effectively increased the whole-cell KATP channel currents in single SMCs isolated from rat aortae. These effects of H2S and pinacidil were antagonized by glibenclamide. (vi) H2S induced a significant membrane hyperpolarization of SMCs. (vii) Finally, we demonstrated that the hypotensive effect of H2S in vivo was suppressed by the KATP channel blocker. The modulatory effect of H2S on KATP channels can be explained by a direct interaction of H2S and KATP channel proteins. Potentially, H2S may induce the reduction of disulfide bonds of the KATP channel protein (Warenycia et al., 1989).

In conclusion, we demonstrate that H2S is an important endogenous vasorelaxant factor. This finding enlarges the family of gaseous vasorelaxant factors by having H2S to join another two established members, i.e. NO and CO (Wang, 1998). The vasorelaxation induced by H2S comprises a minor endothelium-dependent effect and a major direct effect on smooth muscles, which differs from the effects of NO and CO that act only on smooth muscles. While activation of the cGMP pathway is an important mechanism for NO- and CO-induced vasorelaxation, the H2S-induced vasorelaxation is mediated mainly by the opening of KATP channels in vascular SMCs and partially through a K+ conductance in endothelial cells. Thus, this study reveals novel mechanisms underlying the vascular effects of different endogenous molecules of gas. To our knowledge, H2S is the only endogenous gaseous KATP channel opener in vascular SMCs ever reported. Some endogenous substances, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide, have been shown to act on KATP channels (Reslerova and Loutzenhiser, 1998; Szilvassy et al., 1999). However, the effect of these endogenous substances is mediated by membrane receptor- or second messenger-coupled mechanisms. Being a gas, H2S directly acts on KATP channels independent of membrane receptors. Importantly, for the first time we showed that NO appears to be a physiological modulator of the endogenous production of H2S by increasing the CSE expression and stimulating CSE activity. Conceivably, the interaction between two gases, NO and H2S, may function as a molecular switch for regulating vascular tone.

Materials and methods

Tissue contractility study

A total of 50 male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (10–12 weeks old) were used, following an approved protocol by the Committee on Animal Care and Supply of the University of Saskatchewan. The rings of isolated thoracic aortae were prepared as described in our previous publication (Wang et al., 1989). When the concentration of KCl in Krebs’ solution was increased to 20 or 100 mM in some experiments, the osmolality of solution was adjusted by equimolarly decreasing NaCl concentration. Tissues were contracted with submaximal dose of PHE (0.3 µM). At the plateau phase of contraction, the cumulative concentration-response curves of H2S were built and fitted with a Hill equation (Weiss, 1997). Endothelium was kept functionally undamaged in most experiments unless otherwise specified, which was confirmed by the acetylcholine (1 µM)-induced vascular tissue relaxation.

Blood pressure and heart rate measurement

Animals were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (52 mg/kg). Left carotid artery was cannulated and connected to a pressure transducer (AH 51-4844 Harvard, Holliston, USA). One femoral vein was cannulated for delivering chemicals. A heating pad was used to keep the rat’s body temperature stable at 37°C. Data acquisition and analysis were accomplished with a Biopac System (Biopac Systems, Inc., Golata).

After 60 min of equilibration, H2S or other agent was injected in bolus intravenously. Same dose was repeated once with the intervals between injections of at least 10 min.

KATP channel activity in freshly isolated aortic SMCs

Single aortic SMCs were isolated according to our previously published method with modification (Wang et al., 1989). Briefly, thoracic section of aorta was dissected from male SD rats and kept in ice-cold physiological salt solution (PSS). The dissected aorta was incubated at 37°C in low-Ca2+ (0.1 µM) PSS containing 1 mg/ml albumin, 0.75 mg/ml papain and 1 mg/ml dithioerythritol for 30 min. After removing the adventitia, aorta was cut into small pieces and transferred to calcium-free PSS in which 1 mg/ml collagenase and 1 mg/ml hyaluronidase were added. Single cells were released by gentle triturating through a Pasteur pipette, stored in the calcium-free PSS at 4°C and used on the same day of preparation.

The whole-cell patch–clamp technique was used to record KATP channel currents (Tang et al., 1999). Briefly, cells were placed in a Petri dish mounted on the stage of an inverted phase contrast microscope (Olympus IX70). Currents were recorded with an Axopath 1-D amplifier (Axon Instruments Inc.), controlled by a Digidata 1200 interface and pClamp software (version 6.02, Axon Instruments Inc.). Membrane currents were filtered at 1 kHz with a four-pole Bessel filter and sampled at 3.3 kHz, digitized and stored. At the beginning of each experiment, junctional potential between pipette solution and bath solution was electronically adjusted to zero (Wang et al., 1997b). No leakage subtraction was performed to the original recordings and all cells with visible changes in leakage currents during the course of study were excluded from further analysis. Test pulses were made with a 10 mV increment from –100 to +60 mV. The holding potential was set at –60 mV. I–V relationships were constructed using the stable current amplitude at the end of 600 ms test pulses. Membrane potential was recorded with the conventional whole-cell or the perforated whole-cell recording techniques at the current-clamp mode while holding the current at 0 pA. A stable recording of membrane potential was achieved at least 2 min after penetration of cell membrane. The bath solution contained (mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 1.2, HEPES 10, EGTA 1, glucose 10 (pH adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH). The pipette solution used in the conventional whole-cell recording was composed of (in mM): KCl 140, MgCl2 1, EGTA 10, HEPES 10, glucose 5, Na2–ATP 0.5 (pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH). The pipette solution used in the perforated whole-cell recording comprised (mM): KCl 140, MgCl2 1, EGTA 10, HEPES 10, nystatin 250 µg/ml. Cells were continuously superfused with the bath solution containing tested chemicals.

Measurement of endogenous H2S production

Tissue H2S production rate was measured as described previously (Stipanuk and Beck, 1982) with modifications. Briefly, vascular tissues were isolated from rats and homogenized in 50 mM ice-cold potassium phosphate buffer pH 6.8. The reaction mixture contained (mM): 100 potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 10 l-cysteine, 2 pyridoxal 5′-phosphate and 10% (w/v) tissue homogenate. Cryovial test tubes (2 ml) were used as the centre wells each contained 0.5 ml 1% zinc acetate as trapping solution and a filter paper of 2 × 2.5 cm2 to increase the air/liquid contacting surface. The reaction was performed in a 25 ml Erlenmeyer flask (Pyrex, USA). The flasks containing reaction mixture and centre wells were flushed with N2 before being sealed with a double layer of Parafilm. Reaction was initiated by transferring the flasks from ice to a 37°C shaking water bath. After incubating at 37°C for 90 min, 0.5 ml of 50% trichloroacetic acid was added into the reaction mixture to stop the reaction. The flasks were sealed again and incubated at 37°C for another 60 min to ensure a complete trapping of the H2S released from the mixture. The contents of the centre wells were then transferred to test tubes each containing 3.5 ml of water. Subsequently, 0.5 ml of 20 mM N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulphate in 7.2 M HCl was added immediately followed by addition of 0.4 ml 30 mM FeCl3 in 1.2 M HCl. The absorbance of the resulting solution at 670 nm was measured 20 min later with a spectrophotometer (Siegel, 1965). The H2S concentration was calculated against the calibration curve of the standard H2S solutions.

Serum H2S concentration was measured with a sulfide sensitive electrode (Model 9616, Orion Research, Beverly) (Khan et al., 1980).

Screening the expression of CSE and CBS in various arteries by RT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted from vascular tissues of animals using a RNeasy Total RNA Kit (Qiagen) and treated with RNase-free DNase I (Ambion). cDNA was synthesized using random hexamers and MULV reverse transcriptase (Perkin-Elmer). The reverse transcription reaction was carried out at room temperature for 15 min followed by incubation at 42°C for 1 h. PCR was performed using Advanced PCR II mixer (Clontech) with gene-specific primers designed based on the reported sequences of the CSE (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. D17370) (Nishi et al., 1994) and CBS (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. M88344) (Sun et al., 1992), including CSE-forward (5′-aagcagtggctgcactgg-3′), CSE-reverse (5′-tctgtggtgtgatcgctg-3′), CBS-forward (5′-gccaacttctggcaacac-3′) and CBS-reverse (5′-caccagcatgtccaccttc-3′). cDNA obtained from rat liver was used as the positive expression control for both CSE and CBS. The amplified fragments by PCR were gel-purified and sequenced by T7 sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). RT–PCR was also used to detect the CSE transcription in cultured SMCs and endothelial cells.

Cloning and sequencing of CSE from rat vascular tissues

A set of primers was synthesized to cover the ORF of CSE: 5′-cgtcccagcatgcagaagaa-3′ and 5′-cagttattcagaaggtctggcccc-3′. PCR was used to amplify the ORF from rat vascular tissues with 32 thermal cycles (denaturing at 95°C for 20 s and annealing/extending at 68°C for 90 s). The amplified ORF of CSE was subcloned into a TOPO TA cloning vector (PCR4-TOPO). Positive clones containing CSE ORF insert were sequenced by automatic sequencing (ABI 373A) and named PCR4/CSE.

Quantitative determination of CSE mRNA level by RNase protection assay (RPA)

DNA templates for the transcription of CSE were obtained by linearizing PCR4/CSE with HindIII (New England Biolabs) digestion. In vitro transcription using T7 polymerase (Ambion) was performed to generate anti-sense [α-32P]UTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) labelled CSE probes, according to the company’s protocol (RPA IITM, Ambion). β-actin was used as the housekeeping gene and tRNA (Sigma) was applied as negative control. The signals of the protected fragments were scanned and quantified using an imaging analyser (UN-SCAN-IT). The level of CSE transcript was normalized to that of β-actin in each sample.

In situ hybridization study

To generate sense and antisense probes, the CSE-ORF plasmids were linearized by NotI or PmeI and in vitro transcribed by T3 or T7 RNA polymerase, respectively, in the presence of digoxigenin-labelled UTP (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Probes were fragmented to ∼150 bp in length by alkaline treatment before use. Rat aorta was isolated and immediately snap-frozen by liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until use. Cryostat sections of 8 µm were cut on a Micron cryostat at –20°C and thaw-mounted onto ethanol-cleaned slides coated with 1% geltin and 0.1% poly-l-lysine. The sections were vacuum dried and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min. After permeablized by incubating with 10 µg/ml proteinase K (Promega) for 30 min at 37°C and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, the sections were dehydrated and prehybridized for 1 h at 50°C in a hybridization buffer consisting of 50% deionized formamide, 2× SSC (1× SSC: 0.15 M NaCl, 0.017 M sodium citrate), 10% dextran sulfate, 1× Denhardt’s solution, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.05 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5 and 250 µg/ml denatured sonicated salmon sperm DNA (Invitrogen). The prepared slides were then incubated with an anti-sense riboprobe (or a sense probe as a negative control) at 50°C overnight in a humidified box followed by successive incubations in 50% formamide, 2× SSC at 50°C for 30 min and digestion of the single-stranded RNA probe with 20 mg/ml RNase A (Ambion) at 37°C for 30 min. The slides were consecutively washed in 2× SSC at 37°C for 20 min, 1× SSC at 50°C for 20 min, and 0.1× SSC at 50°C for 20 min twice in the shaking water bath. Positive signals were detected by immunoassay with anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate and the color substrates NBT/X-phosphate (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

SMC culture and northern blotting

Single SMCs were isolated and identified from rat aortic tissue as reported previously (Wang et al., 1989; Wu and de Champlain, 1996). Cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum in a CO2 incubator at 37°C. The cells at passages 9–13 were seeded into 100 mm dishes for 3–4 days until they became confluent. The confluent monolayers were first incubated in the serum-free DMEM for 24 h and then different concentrations of S-nitroso-N-acetyl-d,l-penicillamine (SNAP) were added to the calcium-free DMEM for another 6 h. At the end of the incubation period, total RNA was extracted by RNeasy Total RNA Kit (Qiagen). Total RNA (15 µg/lane) denatured by glyoxal/dimethylsulfoxide (Ambion) was subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels, transferred to positive-charged nylon membranes (Hybond, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and UV cross-linked. Hybridization was carried out with the [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) labelled DNA probes by Random Primed DNA Labelling Kit (Boehringer Mannheim) in an ULTRAhyb hybridization buffer (Ambion) at 42°C overnight. cDNA fragments cut from PCR4/CSE were used as template for probe labelling. After one low stringency (2× SSC for 20 min at room temperature) and two high stringency (0.1× SSC for 20 min at 42°C) washings, the membranes were exposed to Kodak film for 24–48 h. Levels of CSE mRNA were normalized by the intensity of the corresponding 28S ribosomal RNA band that was visualized with ethidium bromide staining under UV light.

Chemicals and data analysis

H2S solution was prepared daily either by directly bubbling the saline with pure H2S gas (Praxair, Mississauga, Ontario) to make the saturated H2S solution (0.09 M at 30°C) or by using the stock solution of NaHS (1 M) that has been widely used as the in vitro precursor of H2S. Glibenclamide was purchased from RBI (Natick, MA). All other chemicals were from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

The results were expressed as mean ± SE. All concentration–response curves were fitted with a Hill equation, from which IC50 was calculated. Student’s t-test for unpaired samples was used to compare the mean values between control and tested groups. The changes in blood pressure or heart rate of the same rats were analysed using paired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. For comparison of the differences between control and experimental groups and among experimental groups, ANOVA followed by a post-hoc analysis (Newman–Keuls test) was used.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Dr X.Zhang has given invaluable advice and help on the in situ hybridization experiment. The assistance from Drs G.Tang, S.T.Hanna and Q.Wu is also greatly appreciated. W.Z. holds a post-doctoral fellowship from University of Saskatchewan. R.W. is supported by a Scientist award from Canadian Institutes of Health Research and regional partnership program of Saskatchewan. The project was supported by a research grant from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

References

- Abe K. and Kimura,H. (1996) The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J. Neurosci., 16, 1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech D.J., Zhang,H., Nakao,K. and Bolton,T.B. (1993) K channel activation by nucleotide diphosphates and its inhibition by glibenclamide in vascular smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol., 110, 573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broillet M.C. (1999) S-nitrosylation of proteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci., 55, 1036–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty J.M., Plane,F. and Langton,P.D. (1999) Charybdotoxin and apamin block EDHF in rat mesenteric artery if selectively applied to the endothelium. Am. J. Physiol., 276, H1107–H1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y., Kawasaki,H., Fukao,M. and Kanno,M. (1995) Phorbol esters elicit Ca2+-dependent delayed contractions in diabetic rat aorta. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 279, 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoki R., Matsuki,N. and Kimura,H. (1997) The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 237, 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. (1996) Inhibitory effect of noradrenaline uptake inhibitors on contractions of rat aortic smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol., 117, 533–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S.U., Morris,G.F. and Hidiroglou,M. (1980) Rapid estimation of sulfide in rumen and blood with a sulfide-specific ion electrode. Microchem. J., 25, 388–395. [Google Scholar]

- Kolpakov V., Gordon,D. and Kulik,T.J. (1995) Nitric oxide-generating compounds inhibit total protein and collagen synthesis in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res., 76, 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourembanas K., McQuillan,L.P., Leung,G.K. and Faller,D.V. (1993) Nitric oxide regulates the expression of vasoconstrictors and growth factors by vascular endothelium under both normoxia and hypoxia. J. Clin. Invest., 92, 99–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason J., Cardin,C.J. and Dennehy,A. (1978) The role of sulphide and sulphide oxidation in the copper molybdenum antagonism in rats and guinea pigs. Res. Veter. Sci., 24, 104–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M.T. and Quayle,J.M. (1995) Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol., 268, C799–C822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls P. (1961) The formation and properties of sulphmyoglobin and sulphcatalase. Biochem. J., 81, 374–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi N., Tanabe,H., Oya,H., Urushihara,M., Miyanaka,H. and Wada,F. (1994) Identification of probasin-related antigen as cystathionine γ-lyase by molecular cloning. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 1015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quayle J.M., Bonev,A.D., Brayden,J.E. and Nelson,M.T. (1994) Calcitonin gene-related peptide activated ATP-sensitive K+ currents in rabbit arterial smooth muscle via protein kinase A. J. Physiol., 475, 9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quayle J.M., Bonev,A.D., Brayden,J.E. and Nelson,M.T. (1995) Pharmacology of ATP-sensitive K+ currents in smooth muscle cells from rabbit mesenteric artery. Am. J. Physiol., 269, C1112–C1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remillard C.V. and Leblanc,N. (1996) Mechanism of inhibition of delayed rectifier K+ current by 4-aminopyridine in rabbit coronary myocytes. J. Physiol., 491, 383–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reslerova M. and Loutzenhiser,R. (1998) Renal microvascular actions of calcitonin gene-related peptide. Am. J. Physiol., 274, F1078–F1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Martinez M.A., Garcia-Cohen,E.C., Baena,A.B., Gonzalez,R., Salaices,M. and Marin,J. (1998) Contractile responses elicited by hydrogen peroxide in aorta from normotensive and hypertensive rats. Endothelial modulation and mechanism involved. Br. J. Pharmacol., 125, 1329–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz M., Brown,R.L., He,Y., Haley,T.L. and Karpen,J.W. (1999) The single-channel dose-response relation is consistently steep for rod cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: implications for the interpretation of macroscopic dose-response relations. Biochemistry, 38, 10642–10648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel L.M. (1965) A direct microdetermination for sulfide. Anal. Biochem., 11, 126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.P. and Gosselin,R.E. (1979) Hydrogen sulfide poisoning. J. Occup. Med., 21, 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler J.S., Toone,E.J., Lipton,S.A. and Sucher,N.J. (1997) (S)NO signals: translocation, regulation and a consensus motif. Neuron, 18, 691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipanuk M.H. and Beck,P.W. (1982) Characterization of the enzymic capacity for cysteine desulphhydration in liver and kidney of the rat. Biochem. J., 206, 267–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.W., Alonso-Galicia,M., Swaroop,M., Bradley,K., Ohura,T., Tahara,T., Roper,M.D., Rosenberg,L.E. and Kraus,J.P. (1992) Rat cystathionine β-synthase: gene organization and alternative splicing. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 11455–11461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilvassy J., Jancso,G. and Ferdinandy,P. (1999) Mechanisms of vasodilation by cochlear nerve stimulation. Role of calcitonin gene-related peptide. Pharmacol. Res., 39, 217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talpain E., Armstrong,R.A., Coleman,R.A. and Vardey,C.J. (1995) Characterization of the PGE receptor subtype mediating inhibition of superoxide production in human neutrophils. Br. J. Pharmacol., 114, 1459–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G., Hanna,S.T. and Wang,R. (1999) Effects of nicotine on K+ channel currents in vascular smooth muscle cells from rat tail arteries. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 364, 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. (1998) Resurgence of carbon monoxide: an endogenous gaseous vasorelaxing factor. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol., 76, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Karpinski,E. and Pang,P.K.T. (1989) Two types of calcium channels in isolated smooth muscle cells from rat tail artery. Am. J. Physiol., 256, H1361–H1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Wang,Z.Z. and Wu,L. (1997a) Carbon monoxide-induced vasorelaxation and the underlying mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol., 121, 927–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Wu,L. and Wang,Z.Z. (1997b) The direct effect of carbon monoxide on KCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pflügers Arch., 434, 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warenycia M.W., Steele,J.A., Karpinski,E. and Reiffenstein,R.J. (1989) Hydrogen sulfide in combination with taurine or cysteic acid reversibly abolishes sodium currents in neuroblastoma cells. Neurotoxicology, 10, 191–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J.N. (1997) The Hill equation revisited: uses and misuses. FASEB J., 11, 835–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder C.V. and Winder,H.O. (1933) The seat of action of sulfide on pulmonary ventilation. Am. J. Physiol., 105, 337–352. [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. and de Champlain,J. (1996) Inhibition by cyclic AMP of basal and induced inositol phosphate production in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells from Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens., 14, 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiher A.M., Fisslthaler,B., Schray-Utz,B. and Busse,R. (1995) Nitric oxide modulates the expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in cultured human endothelial cells. Circ. Res., 76, 980–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]