Abstract

Background

Artificial intelligence (AI) models have been increasingly integrated into dental education for assessment and learning support. However, their accuracy and reliability in assessment of dental knowledge requires further evaluation.

Objective

This study aimed to assess and compare the accuracy and response consistency of five AI language models– ChatGPT-4, Grok XI, Gemini, Qwen 2.5 and DeepSeek-V3– using standardised dental multiple-choice questions (MCQs).

Methods

A set of 150 MCQs from two textbooks was used. Each AI model was tested twice, 10 days apart, using identical questions. Accuracy was determined by comparing responses to reference answers, and consistency was measured using Cohen’s kappa and McNemar’s test. The inter-model agreement was also analysed.

Results

ChatGPT-4 showed the highest accuracy (91.3%) in both assessments, followed by Grok XI (90.7–92.7%) and Qwen 2.5 (89.3%). Gemini and DeepSeek performed slightly lower (86.7–88.7%). ChatGPT, Grok XI and Gemini demonstrated strong consistency, whereas Qwen 2.5 and DeepSeek exhibited more variation between test administrations. No significant differences were found in inter-model agreement (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

All five AI models showed high levels of accuracy in answering dental MCQs, and three of the models, ChatGPT-4, Grok XI and Gemini had strong test-retest reliability. These AI models show promise as educational tools, though continued evaluation and refinement are needed for broader clinical or academic applications.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-07624-7.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Medical education, Dentistry, Chatbots, ChatGPT-4, Gemini, DeepSeek-V3, Grok XI and Qwen 2.5

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly evolved into a transformative force across various sectors, including health care and medical education [1]. By simulating complex human cognitive functions such as learning, reasoning and problem-solving, AI technologies are enhancing diagnostic accuracy, streamlining clinical workflows and improving the delivery of health education. As an integral component of health care, dentistry stands to benefit significantly from AI integration, especially in areas such as clinical decision support, patient assessment and the development of advanced educational tools [2].

In alignment with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, which emphasises digital transformation, innovation and the enhancement of healthcare systems, the incorporation of AI into dental education offers strategic value. Vision 2030 seeks to improve the quality, efficiency and accessibility of healthcare services through the adoption of emerging technologies. As such, evaluating the effectiveness and reliability of AI-powered tools in dental education directly supports national priorities for healthcare modernisation and capacity-building [3].

Among the most significant developments in AI are large language models (LLMs), which are trained on vast corpora of text data to perform a range of natural language processing tasks, including text generation, comprehension and question answering [4]. Five AI models (ChatGPT, Gemini, DeepSeek, Grok XI and Qwen 2.5) are known for their technological diversity, global development origins, and increasing relevance in educational and clinical domains. ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI, is a highly versatile model known for its strong performance in academic, clinical and conversational tasks [5]. Gemini, formerly known as Google Bard, is Google’s flagship model, optimised for real-time web integration and advanced information retrieval [6]. DeepSeek is an emerging bilingual LLM designed to perform complex reasoning in both English and Chinese, gaining recognition for its open-source accessibility and high performance [7]. Grok XI, introduced by xAI and integrated into the X (formerly Twitter) platform, is tailored for dynamic, real-time interaction and contextual relevance [8]. Qwen 2.5, developed by Alibaba Cloud, is a multilingual, instruction-tuned model exhibiting strong capabilities in logic-driven tasks and scientific content generation [5].

Despite their promising capabilities, the use of LLMs in medical and dental education raises several concerns, including the potential for misinformation, algorithmic bias and over-reliance on automated content [9]. These risks are especially pertinent in virtual assessment environments, where academic integrity and learning outcomes may be compromised. Although previous studies have demonstrated that some AI models can achieve high scores on medical licensing examinations, such as the USMLE and the Dermatology Specialty Certificate Examination, performance inconsistencies– particularly in higher-order reasoning– highlight the need for further empirical investigation [10].

Access to and distribution of medical information have been completely transformed by the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) into the field of health care. Because of the intricacy and specificity of the operations involved, information correctness and dependability are crucial in dentistry [11–13]. AI chatbots have become a viable source of information on dental health. However, current internet health-related material is sometimes difficult to comprehend and uneven in quality. For a number of reasons, it is crucial to assess how well AI language models respond to dental multiple-choice questions. Initially, it offers an unbiased assessment of these models’ proficiency in comprehending and utilizing intricate, specialized knowledge. Secondly, recognizing differences in responses from various models or repeated queries assists in assessing their reliability as educational or clinical tools. Third, recognizing strengths and weaknesses guides the effective integration of AI into dental education and clinical decision-making processes, ensuring that these technologies enhance rather than compromise educational integrity or the quality of patient care. This study addresses a significant knowledge gap by comparing the performance of leading AI language models on standardized dental MCQs. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate and compare the performance of the five AI models in answering standardised multiple-choice questions (MCQs) relevant to dental education. It aimed at answering the following PICO question “How do five widely used AI language models– ChatGPT-4, Gemini, DeepSeek-V3, Grok XI and Qwen 2.5– compare in terms of accuracy and consistency when answering standardised dental MCQs?”

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

This study did not involve human participants or any personal data. Therefore, informed consent was not required. However, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the College of Dentistry, University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia (Approval No.: H-2025-619). All procedures adhered to ethical guidelines for AI evaluation, including transparency, fairness, and academic integrity.

Study design

This comparative, cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate and compare the performance and consistency of five widely known AI models– ChatGPT-4, Gemini, DeepSeek-V3, Grok XI and Qwen 2.5– in answering standardised MCQs relevant to dental education.

Question source and selection

A total of 150 MCQs were randomly selected from two well-recognised dentistry textbooks: Dental Decks Part II: Comprehensive Flashcards for Your NBDE by Lozier, J. R. (2013, Oakstone Publishing) and First Aid for the NBDE Part II: A Student-to-Student Guide edited by Portnof, J. E., & Leung, T. (2012, McGraw-Hill Education) Supplement A. These resources are widely used in preparation for NBDE and align with the examination’s content specifications. The selected questions covered a comprehensive range of dental specialties, including operative dentistry, prosthodontics, periodontics, endodontics, oral and maxillofacial surgery and pain control, oral medicine, orthodontics, and paediatric dentistry. All selected questions followed a single-best-answer format with four options and only one correct answer. Questions requiring visual interpretation (e.g., radiographs or clinical images) were excluded to maintain consistency in text-only input across all AI models. To ensure content accuracy and relevance, all questions and their corresponding answers were independently reviewed and validated by two licensed dental faculty members prior to inclusion.

AI model selection and justification

The five AI models were chosen based on three criteria: (i) popularity and public accessibility, (ii) demonstrated capacity to handle medical and dental content, and (iii) technological relevance and innovation in natural language processing.

Testing procedure

Each of the five AI models was presented with the same set of 150 MCQs under standardised conditions. Questions were manually input into each model’s interface without any additional prompts, contextual cues or follow-up clarifications. To ensure fairness and neutrality, the question phrasing, formatting and order remained unchanged. The testing was conducted in a controlled environment to minimise potential confounders such as internet connectivity variability, model interface differences and user bias. Examples of user bias, such as inconsistent phrasing or prompting, were minimised by manually entering all questions in identical format and order without additional input.

Consistency assessment

To assess response stability over time, a second round of testing was conducted two weeks after the initial session, using the same set of questions for each AI model. This step was designed to detect potential variations in performance due to model updates, internal algorithmic changes or fluctuating access to real-time information.

Evaluation criteria

The responses were assessed using a binary grading system. A response was marked as correct if it fully aligned with the reference answers provided in the two textbooks and incorrect if it deviated or contained factual errors. Minor variations in language or phrasing were accepted if the underlying information remained accurate. Borderline cases—responses that differed in wording but conveyed equivalent clinical meaning—were independently reviewed by two dental faculty members. Only those with full agreement were marked as correct. Accuracy was calculated using the formula:

Accuracy (%) = (number of correct answers / total questions) × 100.

Accuracy scores were computed for both the initial test and the two weeks re-evaluation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 23.0. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were calculated for each AI model’s performance. Descriptive statistics were employed to explore the findings and summarise frequencies. McNemar’s test was used to compare the first and second sets of responses from each AI model to assess significant differences in performance. Cohen’s kappa was applied to evaluate the level of agreement between the two test rounds for each AI model, reflecting their test–retest reliability. Perfect agreement is represented by a value of 1, whereas the reverse is represented by a value of -1. A kappa value under 0.2 shows little agreement, between 0.2 and 0.4 reflects fair agreement, a value from 0.41 to 0.6 signifies moderate agreement, a value between 0.61 and 0.8 indicates significant agreement, and a value exceeding 0.8 represents excellent agreement. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall performance of AI models

This study evaluated the performance of five AI models– ChatGPT-4, Grok XI, Gemini, Qwen 2.5 and DeepSeek-V3– using a standardised set of 150 MCQs from two textbooks. Each model was assessed in two separate sessions: an initial test and a follow-up reassessment conducted ten days later. The questions are presented in Supplement A.

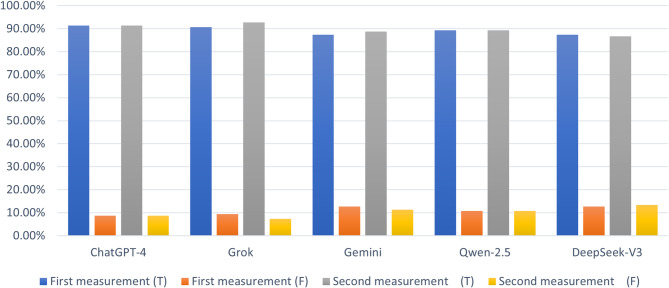

In the first round of testing (Table 1), ChatGPT-4 achieved the highest accuracy, correctly answering 137 questions (91.3%). Grok XI followed closely with 136 correct answers (90.7%), and Qwen 2.5 provided 134 correct responses (89.3%). Both Gemini and DeepSeek-V3 answered 131 questions correctly, representing an accuracy rate of 87.3%. The proportion of incorrect responses ranged from 8.7% for ChatGPT-4 to 12.7% for Gemini and DeepSeek-V3. In the second assessment conducted two weeks later, ChatGPT-4 maintained its previous performance with 137 correct answers (91.3%). Grok XI improved its performance slightly, answering 139 questions correctly (92.7%), and Gemini showed a modest improvement with 133 correct responses (88.7%). Qwen 2.5 remained consistent with 134 correct answers (89.3%), whereas DeepSeek showed a slight decline, answering 130 questions correctly (86.7%), as shown in Table 1; Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Comparison between ideal answers of MCQs with various AI programmes

| Variables | First measurement n (%) | Second measurement n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True answers | False answers | True answers | False answers | |

| Chat GPT | 137 (91.3%) | 13 (8.7%) | 137 (91.3%) | 13 (8.7%) |

| Grok | 136 (90.7%) | 14 (9.3%) | 139 (92.7%) | 11 (7.3%) |

| Gemini | 131 (87.3%) | 19 (12.7%) | 133 (88.7%) | 17 (11.3%) |

| Qwen2.5 | 134 (89.3%) | 16 (10.7%) | 134 (89.3%) | 16 (10.7%) |

| DeepSeek-V3 | 131 (87.3%) | 19 (12.7%) | 130 (86.7%) | 20 (13.3%) |

Fig. 1.

First and second measurements of various AI programmes

Test–retest consistency

To evaluate the consistency of each AI model’s responses over time, Cohen’s kappa values and McNemar’s tests were employed. ChatGPT-4 demonstrated the highest level of response stability, with a kappa value of 0.916. Between the two testing sessions, 136 answers remained consistently correct, one response changed from correct to incorrect and one changed from incorrect to correct. McNemar’s test yielded a p-value of 1.000, indicating no significant change in performance. Grok XI also showed high consistency, with a kappa value of 0.869. It maintained 136 consistent correct answers, and three previously incorrect responses improved to correct, with no answers declining in accuracy. The McNemar p-value was 0.250, confirming no significant variation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationship between first and second measurements of various AI programmes

| ChatGPT-4 | |||

| Measurement | Second Measurement | ||

| Correct | Incorrect | ||

| First measurement | Correct | 136 (90.7%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Incorrect | 1 (0.7%) | 12 (8.0%) | |

| McNemar Test | 1.000 | ||

| Measure of Agreement Kappa | 0.916 | ||

| Grok-XI | |||

| Measurement | Second Measurement | ||

| Correct | Incorrect | ||

| First measurement | Correct | 136 (90.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Incorrect | 3 (2.0%) | 11 (7.3%) | |

| McNemar Test | 0.250 | ||

| Measure of Agreement Kappa | 0.869 | ||

| Gemini | |||

| Measurement | Second Measurement | ||

| Correct | Incorrect | ||

| First measurement | Correct | 130 (86.7%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Incorrect | 3 (2.0%) | 16 (10.7%) | |

| McNemar Test | 0.625 | ||

| Measure of Agreement Kappa | 0.874 | ||

| Qwen-2.5 | |||

| Measurement | Second Measurement | ||

| Correct | Incorrect | ||

| First measurement | Correct | 129 (86.0%) | 5 (3.3%) |

| Incorrect | 5 (3.3%) | 11 (7.3%) | |

| McNemar Test | 1.000 | ||

| Measure of Agreement Kappa | 0.650 | ||

| DeepSeek-V3 | |||

| Measurement | Second Measurement | ||

| Correct | Incorrect | ||

| First measurement | Correct | 126 (84.0%) | 5 (3.3%) |

| Incorrect | 4 (2.7%) | 15 (10.0%) | |

| McNemar Test | 1.000 | ||

| Measure of Agreement Kappa | 0.735 | ||

Gemini demonstrated a kappa value of 0.874, reflecting excellent agreement between sessions. A total of 130 responses remained correct across both assessments, with three shifting from incorrect to correct and one from correct to incorrect. The corresponding McNemar p-value was 0.625. Qwen 2.5 showed increased variability, with a kappa value of 0.650. The McNemar p-value remained at 1.000. DeepSeek-V3 demonstrated the lowest agreement, with a kappa value of 0.735. A total of 126 answers were consistently correct, five responses shifted from correct to incorrect, and four improved from incorrect to correct. McNemar’s test again yielded a p-value of 1.000, as presented in Table 2. These results suggest that ChatGPT-4, Grok XI and Gemini exhibited greater response stability over time, whereas Qwen 2.5 and DeepSeek-V1 showed more frequent fluctuations in answer accuracy.

Agreement between AI models

A pairwise comparison was conducted to explore the degree of answer agreement between the five AI models, analysing how often each pair of models provided the same answer, either correctly or incorrectly (Table 3). ChatGPT-4 and Grok XI showed the highest agreement, with 135 matching correct responses and nine questions answered incorrectly by both models. Grok XI disagreed with ChatGPT-4 on two questions where ChatGPT-4 was correct and answered four additional questions correctly that ChatGPT answered incorrectly.

Table 3.

Comparison between various AI programmes

| AI Models | ChatGPT-4 | Grok | Gemini | Qwen-2.5 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | P Value | Correct | Incorrect | P Value | Correct | Incorrect | P Value | Correct | Incorrect | P Value | |||

| Grok | Correct | 135 | 4 | 0.687 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Incorrect | 2 | 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| Gemini | Correct | 130 | 3 | 0.344 | 129 | 4 | 0.549 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Incorrect | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| Qwen2.5 | Correct | 129 | 5 | 0.504 | 128 | 6 | 0.482 | 125 | 9 | 0.515 | - | - | - | |

| Incorrect | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 10 | - | - | ||||||

| DeepSeek-V3 | Correct | 126 | 4 | 0.118 | 126 | 4 | 0.180 | 124 | 6 | 0.617 | 123 | 6 | 0.433 | |

| Incorrect | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 11 | 9 | ||||||

The comparison between ChatGPT and Gemini showed that both models agreed on 130 correct answers and 10 shared incorrect responses. ChatGPT answered three questions incorrectly that Gemini got right, and Gemini answered seven questions incorrectly that ChatGPT answered correctly. ChatGPT and Qwen 2.5 shared 129 correct responses and eight incorrect ones, with Qwen 2.5 answering five questions correctly that ChatGPT missed and providing eight incorrect answers where ChatGPT was correct. ChatGPT and DeepSeek shared 126 correct and nine incorrect answers, with 11 discrepancies in which ChatGPT was correct and DeepSeek was not, as well as four where DeepSeek was correct and ChatGPT was not.

Grok XI and Gemini displayed strong alignment, agreeing on 129 correct responses and 10 shared incorrect answers. Grok XI answered four questions incorrectly that Gemini answered correctly, whereas Gemini missed seven questions that Grok XI answered correctly. Grok XI and Qwen 2.5 shared 128 correct answers and eight identical incorrect answers. However, Qwen 2.5 misclassified eight questions that Grok XI answered correctly and answered six questions correctly that Grok misclassified. Similarly, Grok XI and DeepSeek agreed on 126 correct answers and 10 incorrect ones, with Grok XI outperforming DeepSeek on 10 questions, whereas DeepSeek correctly answered four that Grok XI did not.

The comparison between Gemini and Qwen 2.5 showed agreement on 125 correct responses and 10 incorrect ones. Qwen 2.5 misclassified six questions that Gemini answered correctly, while correctly answering nine questions that Gemini got wrong. Gemini and DeepSeek shared 124 correct responses and 13 incorrect ones. DeepSeek answered seven questions incorrectly that Gemini answered correctly and correctly answered six that Gemini missed. Finally, Qwen 2.5 and DeepSeek agreed on 123 correct and nine incorrect answers, with Qwen 2.5 answering 11 questions correctly that DeepSeek missed, and DeepSeek answering six correctly that Qwen 2.5 misclassified.

Despite these discrepancies, the statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in agreement between the AI model pairs because all p-values exceeded the 0.05 threshold. These results suggest that, overall, the AI models demonstrated comparable decision-making behaviour and consistent answer patterns across the dataset, even in cases where individual performance varied.

Discussion

In an era characterised by rapid information accessibility, AI-powered chatbots have become increasingly popular tools for retrieving knowledge, including health-related information. These systems are capable of producing human-like responses with minimal input, making them highly attractive in medical and dental education. However, despite their advantages, the growing reliance on AI raises critical concerns regarding the accuracy, trustworthiness, and consistency of the information they generate [3, 5]. Learners and patients alike may assume AI-generated content to be inherently accurate, potentially leading to misinformation if the limitations of these systems are not recognised.

This study evaluated and compared the performance of five widely used AI models– ChatGPT-4, Grok XI, Gemini, Qwen 2.5 and DeepSeek-V3– in answering a standardised set of 150 dental MCQs. All models demonstrated high accuracy, with ChatGPT-4, Grok XI and Qwen 2.5 achieving the highest scores, ranging from 89.3 to 92.7%. DeepSeek-V3 and Gemini followed with slightly lower, yet still strong, performances between 86.7% and 88.7%. These findings support the growing body of evidence highlighting the role of AI in medical education and evaluation [14–21].

The utility and dependability of dental implantology-related data from the ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, and Google Gemini large language models (LLMs) were compared by Taymour et al. [12]. When answering questions on dental implants, the three AI chatbots demonstrated acceptable degrees of dependability and utility. Google Gemini set itself apart by offering answers that aligned with expert consultations. The accuracy of GenAI in responding to questions from dental licensing exams was examined by Chau et al. [13]. The most recent iteration of GenAI has demonstrated strong performance in responding to multiple-choice questions on dental licensing exams. According to Revilla-León et al. [22], ChatGPT passed the EAO’s 2022 Certification in Implant Dentistry exam. Furthermore, the score was affected by the ChatGPT software version. According to Rokhshad et al. [23], chatbots were less accurate than dentists when responding to pediatric dentistry questions. This may explain why their integration into clinical pediatric dentistry remains limited. Comparable results were reported by Ahmed et al. (2024), who evaluated ChatGPT-4, Gemini and Claude 3 Opus on a variety of medical MCQs, finding accuracies between 85.7% and 100%, consistent with our findings [24]. Similarly, Quah et al. (2024) assessed ChatGPT-4, ChatGPT-3.5, Gemini and other models in oral and maxillofacial surgery questions. ChatGPT-4 achieved the highest accuracy (76.8%), whereas Gemini scored lower (58.7%), indicating variability in performance across models and specialities [25]. A previous study by Kung et al. (2023) found that ChatGPT passed all three parts of the US Medical Licensing Examination, further validating its potential in clinical education [26]. In dental-specific contexts, AI accuracy has varied. For example, in a study examining AI-generated responses to paediatric dentistry questions, chatbots achieved lower accuracy (78%) compared to human clinicians (96.7%), though consistency among chatbot responses remained acceptable, especially with newer models [27].

The high performance of ChatGPT and Grok XI in this study may be attributed to their use of advanced transformer-based architectures and deep learning techniques. These mirror the mechanisms underlying other successful dental AI applications, such as radiographic diagnosis and caries detection [28, 29]. The findings underscore the evolving capacity of AI to support educational outcomes. In addition to accurately answering MCQs, AI models can contribute meaningfully to adaptive learning. They can tailor educational content to individual learning needs, adjust question difficulty based on performance and provide targeted feedback, all of which may enhance student engagement and retention [14–21].

AI tools also hold promise in supporting educators. They can generate high-quality examination items, offer detailed rationales for answer choices, and assist in evaluating question difficulty and content validity. Instructors can use AI-generated outputs to identify gaps in student knowledge and refine instructional strategies accordingly. Integrating AI into learning environments has been associated with improvements in explicit reasoning, learning motivation and knowledge retention [30].

The consistency of AI responses over time, observed in this study, also suggests their reliability as educational tools. ChatGPT-4, Grok XI and Gemini demonstrated minimal variability in test–retest performance, whereas Qwen 2.5 and DeepSeek-V3 showed slightly higher inconsistency. This variance may reflect differences in internal model updates, inference strategies or reliance on real-time web data. Machine learning techniques, including reinforcement learning from user interactions, could also contribute to models’ ability to refine outputs over time. The capacity for continuous improvement, coupled with real-time access to updated data, positions these models as potentially valuable tools for up-to-date, responsive learning [30, 31].

In line with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, which promotes digital innovation and the modernisation of health care and education, the integration of AI in dental training aligns with national objectives to improve efficiency, equity and quality in medical sciences. These findings suggest that AI chatbots, when used responsibly, can significantly contribute to these goals by supplementing traditional education with flexible, intelligent and scalable learning tools.

Despite these promising results, this study has several limitations. Although the dataset of 150 MCQs was derived from widely respected sources, it may not fully capture the breadth of all dental subdisciplines. The evaluation was restricted to text-based, single-best-answer questions, which may not reflect the complexity of clinical decision-making or performance-based assessments. Furthermore, although standardised scoring was applied, subjective judgment was involved in grading borderline responses. Importantly, newer AI models are continually emerging and may outperform the ones tested here in future evaluations.

Clinical implications

In terms of teaching, these resources might be useful supplements for dental students getting ready for tests since they provide instant feedback and reinforce fundamental concepts. Their capacity to model clinical reasoning on a wide range of subjects could promote formative evaluation and improve self-directed learning.

Although AI has shown potential in clinical settings for decision support and preliminary case analysis, relying solely on AI-generated responses without careful review may result in misunderstandings or improper treatment planning. As a result, AI should only be used in supportive, non-autonomous capacities in dentistry practice, ideally as a component of a larger clinical decision support system that is supervised by qualified experts. As long as their limits are recognized and they are utilized in addition to human experience rather than in instead of it, the thoughtful incorporation of AI models into dentistry education and practice has the potential to improve learning and facilitate clinical processes.

Initial limitations include the static nature of AI responses at the time of the study and the possibility of updates in AI models that could alter performance. Although MCQs are commonly used in dental education, they are only one type of assessment. Future research should take into account longitudinal studies to assess the evolution of AI chatbot capabilities over time. The study’s methodology, which included blinded evaluations and a comprehensive question set, strengthens the validity of the results. Other formats that are essential to dental competency, like short-answer questions, image-based diagnosis, and clinical case analyses, were not evaluated in this study. The study did not assess the therapeutic suitability or safety of the AI-generated responses; instead, it concentrated on accuracy and consistency. In a clinical setting tailored to a patient, an AI model may choose a technically correct response that is inappropriate.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, the AI chatbots evaluated, particularly ChatGPT-4 and Grok XI, demonstrated high accuracy and consistency in answering standardised dental examination questions. These findings support their potential utility as supplementary tools for dental education and formative assessment. The observed performance reinforces the growing role of LLMs in academic contexts, where they can enhance learning outcomes, support content generation and offer adaptive feedback for learners.

Despite their promising capabilities, current AI models still require refinement to meet the rigorous standards necessary for clinical decision-making and patient care. As these technologies continue to evolve, ongoing evaluation and expert oversight will be essential to ensure their safe and effective integration into dental education and practice.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

AFA, AAM, and KAA contributed to the concept of the research, study design, data collection, supervision, statistical analysis, writing the original draft, and reading and editing the final paper. YEA, and BAA contributed to data collection, and writing the original draft. Every author evaluated and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets created and/or analyzed for the current study are not publicly accessible because ethics approval was given on the grounds that only the researchers involved in the study would have access to the identified data, but they are available from the corresponding author upon justifiable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Medical Ethical Committee of the College of Dentistry, University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia, approved the protocol of this study (Approval No.: H-2025-619). As no human participants were involved, informed consent was not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Abdullah F. Alshammari, Email: Abd.alshamari@uoh.edu.sa

Ahmed A. Madfa, Email: ahmed_um_2011@yahoo.com

Refrences

- 1.Ramesh A, Kambhampati C, Monson J, Drew P. Artificial intelligence in medicine. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86(5):334–8. 10.1308/147870804290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun L, Yin C, Xu Q, Zhao W. Artificial intelligence for healthcare and medical education: a systematic review. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15(7):4820–8. PMID: 37560249; PMCID: PMC10408516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muafa AM, Al-Obadi SH, Al-Saleem N, Taweili A, Al-Amri A. The impact of artificial intelligence applications on the digital transformation of healthcare delivery in riyadh, Saudi Arabia (opportunities and challenges in alignment with vision 2030). Acad J Res Sci Publ. 2024;5(59).

- 4.Ayan E, Bayraktar Y, Çelik Ç, Ayhan B. Dental student application of artificial intelligence technology in detecting proximal caries lesions. J Dent Educ. 2024;88(4):490–500. 10.1002/jdd.13437. PMID: 38200405. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Aydin O, Karaarslan E, Erenay FS, Bacanin N, Generative. AI in academic writing: A comparison of deepseek, qwen, chatgpt, gemini, llama, mistral, and Gemma. ArXiv Published Febr 11, 2025. arXiv:2503.04765.

- 6.Akhtar ZB. From bard to gemini: an investigative exploration journey through google’s evolution in conversational AI and generative AI. Comput Artif Intell. 2024;2(1):1378. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu P, Wu Y, Jin K, Chen X, He M, Shi D. DeepSeek-R1 outperforms gemini 2.0 pro, openai o1, and o3-mini in bilingual complex ophthalmology reasoning. ArXiv Published Febr 25, 2025. arXiv:2502.17947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Jegham N, Abdelatti M, Hendawi A. Visual reasoning evaluation of grok, deepseek janus, gemini, qwen, mistral, and ChatGPT. ArXiv Published Febr 23, 2025. arXiv:2502.16428.

- 9.Abd-alrazaq A, Rababeh A, Alajlani M, Bewick BM, Househ M. Large Language models in medical education: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:e48291. 10.2196/48291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu K. Can ChatGPT help college instructors generate high-quality quiz questions? In: Ahram T, Taiar R, Gremeaux-Bader V, editors. Human interaction and emerging technologies (IHIET-AI 2023): artificial intelligence and future applications. AHFE Open Access; 2023. 10.54941/ahfe1002957.

- 11.Büttner M, Leser U, Schneider L, Schwendicke F. Natural Language processing: chances and challenges in dentistry. J Dent. 2024;141:104796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taymour N, Fouda SM, Abdelrahaman HH, Hassan MG. Performance of the ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, and Google gemini large Language models in responding to dental implantology inquiries. J Prosthet Dent. 2025 Jan 4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Chau RC, Thu KM, Yu OY, Hsung RT, Lo EC, Lam WY. Performance of generative artificial intelligence in dental licensing examinations. Int Dent J. 2024;74(3):616–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdulrab S, Abada H, Mashyakhy M, Mostafa N, Alhadainy H, Halboub E. Performance of 4 artificial intelligence chatbots in answering endodontic questions. J Endod. 2025;51(1):13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freire Y, Laorden AS, Pérez JO, Sánchez MG, García VD, Suárez A. ChatGPT performance in prosthodontics: assessment of accuracy and repeatability in answer generation. J Prosthet Dent. 2024;131(4):659e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi S, Morishita M, Fukuda H, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of leading large Language models in the Japanese National dental hygienist examination: a comparative analysis of chatgpt, bard, and Bing chat. J Dent Sci. 2024;19(4):2262–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brozović J, Mikulić B, Tomas M, Juzbašić M, Blašković M. Assessing the performance of Bing chat artificial intelligence: dental exams, clinical guidelines, and patients’ frequent questions. J Dent. 2024;144:104927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danesh A, Pazouki H, Danesh K, Danesh F, Danesh A. The performance of artificial intelligence Language models in board-style dental knowledge assessment: a preliminary study on ChatGPT. J Am Dent Assoc. 2023;154(11):970–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danesh A, Pazouki H, Danesh F, Danesh A, Vardar-Sengul S. Artificial intelligence in dental education: chatgpt’s performance on the periodontic in‐service examination. J Periodontol. 2024;95(7):682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabri H, Saleh MH, Hazrati P, et al. Performance of three artificial intelligence (AI)-based large Language models in standardized testing; implications for AI‐assisted dental education. J Periodontal Res Published Online July. 2024;18. 10.1111/jre.13203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Sismanoglu S, Capan BS. Performance of artificial intelligence on Turkish dental specialization exam: can ChatGPT-4.0 and gemini advanced achieve comparable results to humans? BMC Med Educ. 2025;25(1):214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Revilla-León M, Barmak BA, Sailer I, Kois JC, Att W. Performance of an artificial Intelligence–Based chatbot (ChatGPT) answering the European certification in implant dentistry exam. Int J Prosthodont. 2024;37(2). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Rokhshad R, Zhang P, Mohammad-Rahimi H, Pitchika V, Entezari N, Schwendicke F. Accuracy and consistency of chatbots versus clinicians for answering pediatric dentistry questions: A pilot study. J Dent. 2024;144:104938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad B, Saleh K, Alharbi S, Alqaderi H, Jeong YN. Artificial intelligence in periodontology: performance evaluation of chatgpt, claude, and gemini on the in-service examination. MedRxiv Preprint Posted Online May. 2024;31. 10.1101/2024.05.29.24308155.

- 25.Quah B, Yong CW, Lai CW, Islam I. Performance of large Language models in oral and maxillofacial surgery examinations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024;53(10):881–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kung TH, Cheatham M, Medenilla A, et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: potential for AI-assisted medical education using large Language models. PLoS Digit Health. 2023;2(2):e0000198. 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rokhshad R, Zhang P, Mohammad-Rahimi H, Pitchika V, Entezari N, Schwendicke F. Accuracy and consistency of chatbots versus clinicians for answering pediatric dentistry questions: A pilot study. J Dent. 2024;144:104938. 10.1016/j.jdent.2024.104938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Başaran M, Çelik Ö, Bayrakdar IS, et al. Diagnostic charting of panoramic radiography using deep-learning artificial intelligence system. Oral Radiol. 2022;38:363–9. 10.1007/s11282-021-00560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alharbi SS, AlRugaibah AA, Alhasson HF, Khan RU. Detection of cavities from dental panoramic X-ray images using nested U-Net models. Appl Sci. 2023;13(10):5776. 10.3390/app13105776. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman RS, Patrinely JR, Stone CA Jr, et al. Accuracy and reliability of chatbot responses to physician questions. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2336483. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng X, Yu Z. A meta-analysis and systematic review of the effect of chatbot technology use in sustainable education. Sustainability. 2023;15(4):2940. 10.3390/su15042940. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets created and/or analyzed for the current study are not publicly accessible because ethics approval was given on the grounds that only the researchers involved in the study would have access to the identified data, but they are available from the corresponding author upon justifiable request.