Abstract

Cellular adhesion is regulated by members of the cadherin family of adhesion receptors and their cytoplasmic adaptor proteins, the catenins. Adhesion complexes are regulated by recycling from the plasma membrane and proteolysis during apoptosis. We report that in MCF-7, MDA-MB-468 and MDCK cells, induction of apoptosis by agents that cause endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress results in O-glycosylation of both β-catenin and the E-cadherin cytoplasmic domain. O-glycosylation of newly synthesized E-cadherin blocks cell surface transport, resulting in reduced intercellular adhesion. O-glycosylated E-cadherin still binds to β- and γ-catenin, but not to p120-catenin. Although O-glycosylation can be inhibited with caspase inhibitors, cleavage of caspases associated with the ER or Golgi complex does not correlate with E-cadherin O-glycosylation. However, agents that induce apoptosis via mitochondria do not lead to E-cadherin O-glycosylation, and decrease adhesion more slowly. In MCF-7 cells, this is due to degradation of E-cadherin concomitant with cleavage of caspase-7 and its substrate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. We conclude that cytoplasmic O-glycosylation is a novel, rapid mechanism for regulating cell surface transport exploited to down-regulate adhesion in some but not all apoptosis pathways.

Keywords: apoptosis/caspase/catenin/E-cadherin/O-glycosylation

Introduction

In epithelia and endothelia, cadherin complexes are the main mediators of intercellular adhesion (reviewed in Gumbiner, 2000). The extracellular domains of epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin) interact in a calcium-dependent fashion, whereas the cytoplasmic domain binds directly to either β-catenin or γ-catenin, which in turn bind to α-catenin. In addition, E-cadherin binds to p120-catenin (Ohkubo and Ozawa, 1999). Binding to the actin cytoskeleton occurs either directly via α-catenin or via an interaction between α-catenin and α-actinin (Daniel and Reynolds, 1997). Recently, recycling was proposed as a potential mechanism for regulating cadherins as E-cadherin is trafficked through an endocytic pathway (Le et al., 1999).

Anchorage to substrate is essential for the survival of many cell types, where loss of integrin-mediated adhesion initiates apoptosis (Frisch and Ruoslahti, 1997). In epithelia, inhibition of apoptosis also depends on contact with adjacent cells, and binding of cadherin molecules may transduce apoptotic suppressive signals via activated Rb (Day et al., 1999). The first visible stage of prostate and mammary involution is the disruption of intercellular adhesion and anchorage (Vallorosi et al., 2000). Adhesion is decreased by caspase-mediated cleavage of both β-catenin and γ-catenin (Herren et al., 1998) as well as E-cadherin (Day et al., 1999).

We examined E-cadherin dynamics in three epithelial cell lines (MCF-7, MDCK and MB-MDA-468) during apoptosis induced by agents that act through either an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)- or mitochondria-dependent pathway (Annis et al., 2000; Soucie et al., 2001). By activating the ER cell death pathway with the ER calcium pump inhibitor thapsigargin or ceramide, both E-cadherin and β-catenin are O-glycosylated early during apoptosis. O-glycosylation of β-catenin does not alter its adhesive functions, but modification of newly synthesized E-cadherin prevents binding to p120-catenin, cell surface transport and incorporation into adhesion sites, all concomitant with loss of intercellular adhesion. The block in cell surface transport is specific to the glycosylated molecules, as E-cadherins that escape modification continue to transit to the cell surface. Loss of adhesion and of E-cadherin from the cell surface and O-glycosylation of E-cadherin are all prevented by caspase inhibitors. Surprisingly, examination of caspases localizing at the ER and/or Golgi complex revealed cleavage of caspase-2 and a ‘caspase-12 like’ protein after estrogen deprivation but prior to commitment to apoptosis. When drugs were used that target the mitochondrial cell death pathway, loss of adhesion occurred more slowly and correlated with degradation of E-cadherin and cleavage of caspase-7 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP). This late, caspase-dependent cleavage of E-cadherin was also observed after treatment with thapsigargin or ceramide. We propose that trafficking of E-cadherin is regulated by reversible O-glycosylation. During apoptosis via the ER pathway, adhesion is down-regulated rapidly by caspase-mediated inhibition of deglycosylation, resulting in the accumulation of glycosylated E-cadherin that is blocked for cell surface transport.

Results

Modification of E-cadherin blocks transport to the cell surface

In MCF-7 cells, endogenous Bcl2 levels can be down-regulated by estrogen depletion, modeling the hormonal fluctuation experienced by adult breast epithelium. Estrogen depletion for 6 days does not induce apoptosis, but sensitizes cells to cytotoxic stimuli (Teixeira et al., 1995). To study the role of intercellular adhesion during cell death, we used well-characterized inducers of apoptosis via either an ER- (thapsigargin and ceramide) or a mitochondria [adriamycin and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)]-dependent pathway (Teixeira et al., 1995; Qi et al., 1997; Annis et al., 2000; Soucie et al., 2001). For the detailed study of early events, thapsigargin has the advantage of inducing apoptosis slowly, with cleavage of PARP first evident 18 h after treatment, compared with 6 h for ceramide (data not shown).

Exposure of estrogen-deprived MCF-7 cells to thapsigargin induces a profound shape change and decreased adhesion to neighboring cells, evident at 18 h and more marked by 30 h. These morphological changes are correlated with a loss of cell surface E-cadherin, most notably along the intercellular borders, within clusters of cells as detected by immunofluorescence microscopy of non-permeabilized cells (Figure 1A, 18 h, arrowheads). Loss of E-cadherin is not due to decreased synthesis or increased, caspase-mediated degradation, as permeabilization of the cell with non-ionic detergent (Figure 1A) and immunoblotting (Figure 2) revealed that the total amount of E-cadherin is unchanged. Significantly, this distribution of E-cadherin is consistent with transport through almost the entire secretory pathway as most E-cadherin is located just below the plasma membrane (Figure 1A, Total). Thus, E-cadherin is either blocked in cell surface transport late in the secretory pathway or has been removed from the cell surface by internalization via endocytosis.

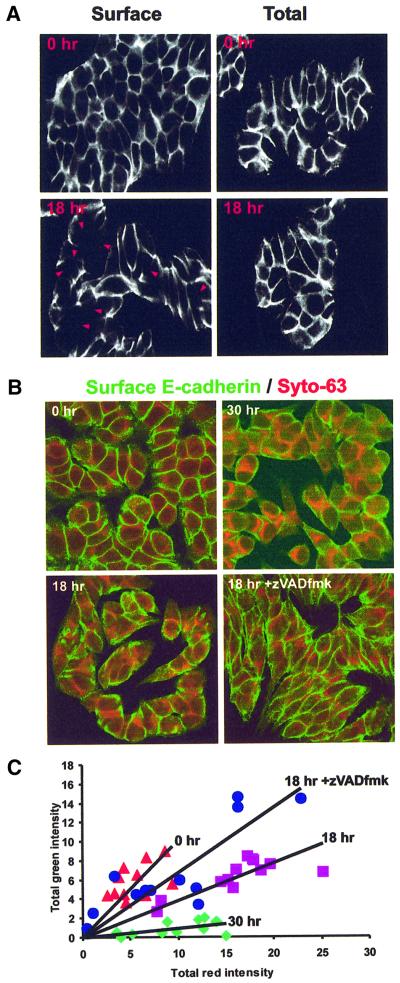

Fig. 1. Loss of E-cadherin from the cell surface during apoptosis is blocked by the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk. (A) E-cadherin localized by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy after estrogen depletion (0 h) and incubation with thapsigargin (TG) for 18 h. E-cadherin was localized using a monoclonal antibody to an extracellular epitope and FITC-labeled secondary antibodies. Staining of non-permeabilized cells identifies E-cadherin on the plasma membrane (Surface). Permeabilization of the cells with Triton X-100 prior to labeling allows visualization of all of the E-cadherin in the cell (Total). Extracellular E-cadherin staining is reduced at areas of cell contact after 18 h exposure to thapsigargin (arrowheads). (B) Non-permeabilized cells were stained with a monoclonal antibody to E-cadherin and secondary antibodies labeled with FITC (green). Cell contents were labeled using Syto-63, a dye that in fixed cells stains principally extranuclear nucleic acids. The intensity of green relative to red indicates the amount of E-cadherin on the cell surface after treatment with thapsigargin for 0, 18 and 30 h. Addition of zVAD-fmk prevents loss of E-cadherin from the cell surface. (C) Quantification of cell surface E-cadherin by image analysis. Each point represents one image similar to those seen in (B). Images were thresholded auto matically to remove background noise and the total amount of red and green staining summed. The total red intensity is directly proportional to cell number in each image; therefore, the slope of each line reflects the amount of E-cadherin externalized/cell. Lines of best fit were calculated by linear regression. After estrogen depletion, prior to thapsigargin, 0 h, red triangles; incubation in thapsigargin 18 h, purple squares; with zVAD-fmk, blue circles. Incubation in thapsigargin 30 h, green diamonds.

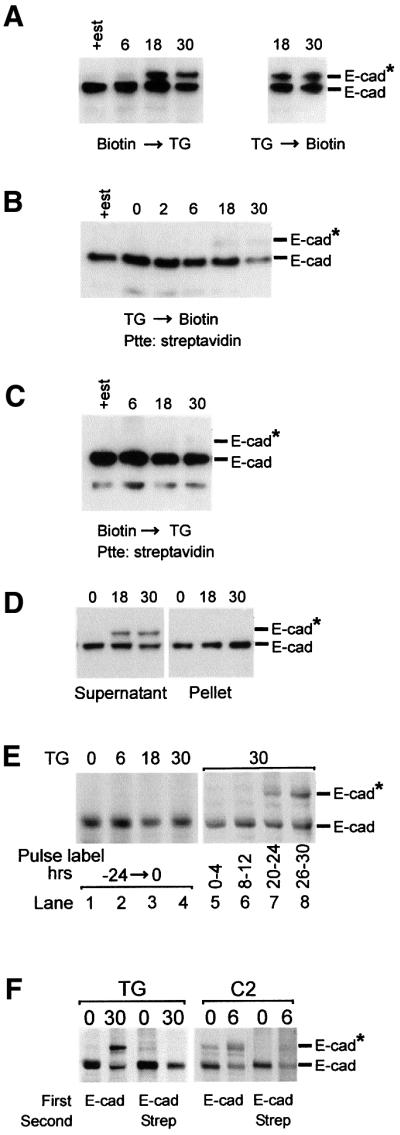

Fig. 2. Newly synthesized E-cadherin is modified and blocked for cell surface transport. (A) Biotinylation of cell surface proteins before or after adding thapsigargin does not affect the total amount or modification of E-cadherin. Cells were grown for 6 days in estrogen-depleted medium (+est indicates cells in estrogen-replete medium) and then cell surface proteins biotinylated using EZ-Link™ Biotin for 30 min prior to (left panel) or after (right panel) addition of thapsigargin. Cells were incubated in thapsigargin for the time indicated above the lanes. After solubilization using a buffer containing Triton X-100, proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and E-cadherin was identified by immunoblotting. (B) Modified E-cadherin is not transported to the cell surface. Cells were grown in estrogen-depleted medium, and treated with thapsigargin for the time indicated above the lanes. Cell surface proteins were biotinylated and solubilized; biotinlyated proteins were isolated using streptavidin magnetic microspheres (Ptte: streptavidin), separated by SDS–PAGE and E-cadherin identified by immunoblotting. (C) Pre-existing cell surface E-cadherin is not modified during apoptosis. E-cadherin on the cell surface was biotinylated and cells treated with thapsigargin. At the times indicated, biotinylated molecules were isolated, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. (D) Modified E-cadherins are not found in the Triton X-100-insoluble cytoskeleton. Cells were grown in estrogen-depleted medium, treated with thapsigargin for the times indicated and solubilized with buffer containing 1% Triton X-100. The Triton X-100-insoluble cytoskeleton was pelleted by centrifugation and solubilized with SDS–PAGE loading buffer. Aliquots containing proteins from 40 000 cells were separated by SDS–PAGE and E-cadherin identified by immunoblotting. (E) Newly synthesized but not pre-existing E-cadherin is modified during thapsigargin-induced apoptosis. Lanes 1–4: cells were labeled continuously with [35S]methionine for 24 h and apoptosis induced with thapsigargin for the time indicated above the lanes; E-cadherin was immunoprecipitated from Triton X-100 cell lysates and analyzed by SDS–PAGE. Lanes 5–8: thapsigargin was added to the cells and then incubated for 30 h. The cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine during the time period indicated below the lanes. E-cadherin was immunoprecipitated from Triton X-100 cell lysates and analyzed by SDS–PAGE (separation time 7.5 h). (F) Cell surface transport of modified E-cadherin is blocked selectively. Untreated cells (0) or cells exposed to thapsigargin (TG) or C2-ceramide (C2) for the time indicated above the lanes (h) were labeled with [35S]methionine for 4 h and cell surface proteins biotinylated. The cells were lysed in Triton X-100, and E-cadherin immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS–PAGE (separation time 7.5 h) and autoradiography either directly (first two lanes in each panel) or after release with SDS and re-precipitation with streptavidin (last two lanes in each panel). The migration positions of E-cadherin (E-cad) and modified E-cadherin (E-cad*) are indicated to the right of the panels. Addition of streptavidin magnetic microspheres is indicated as Streptavidin or Strep.

To quantify loss of cell surface labeling, we used the cell-permeant dye Syto-63 as an internal standard for cell number/volume and then stained cell surface E-cadherin of non-permeabilized cells using an antibody directed against the external domain (Figure 1B). If the amount of E-cadherin on the outside of the cell correlates with cell number, then a plot of total green (cell surface E-cadherin) versus red (Syto-63) intensities results in a straight line. Indeed, for multiple coverslips processed at the same time, the slope of the line obtained was directly proportional to the amount of E-cadherin on the cell surface (Figure 1C). In the experiment shown in Figure 1, the slope of the line indicating the amount of E-cadherin/cell decreased from 1.01 to 0.38 and then to 0.09 after 18 and 30 h incubation with thapsigargin, respectively. Results of three independent analyses gave similar results, confirming loss of cell surface E-cadherin, although the values can be compared only for slides processed together. Furthermore, this loss was inhibited substantially by the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk, as reflected by a slope of 0.67 (Figure 1B and C). Although intercellular adhesion was compromised within 18 h, loss of adherence to the culture dish was not prevalent until 72 h of exposure to thapsigargin.

To our surprise, immunoblotting revealed that loss of cell surface E-cadherin correlated with a modification that reduces electrophoretic mobility consistent with a molecular weight change of 20 kDa (Figure 2A, E-cad*). We demonstrate below that this modification occurs only on newly synthesized E-cadherin in the Triton X-100-soluble pool and is due to O-linked glycosylation of the cytoplasmic domain.

Since E-cadherin is trafficked constantly through an endocytic pathway, it is possible that loss of cell surface E-cadherin is due to increased endocytosis. To determine if E-cadherin is accumulating in the Rab5-positive endocytic compartment, we transfected cells with a plasmid expressing a Rab5–green fluorescence protein (GFP) fusion. Confocal microscopy of permeabilized cells revealed no significant co-localization of E-cadherin with Rab5 (data not shown). To confirm that internalization was not due to endocytosis, we examined whether glycosylated E-cadherin molecules can be detected at the cell surface. To identify cell surface proteins, they were labeled with biotin, isolated with streptavidin and analyzed by immunoblotting. Control experiments demonstrated that biotinylation did not affect thapsigargin-induced O-glycosylation, as the shift in gel mobility of E-cadherin was equivalent whether biotin was added before or after thapsigargin (Figure 2A).

When cell surface proteins were labeled with biotin, the unmodified form of E-cadherin was biotinylated efficiently, but glycosylated E-cadherin was protected (Figure 2B). Consistent with the data in Figure 1, the unmodified E-cadherin biotinylated on the cell surface decreased with exposure to thapsigargin (Figure 2B). These results suggest that glycosylation of E-cadherin either occurs intracellularly and prevents transport to the cell surface or causes rapid internalization of cell surface E-cadherin. Biotin labeling before thapsigargin treatment permits the latter hypothesis to be addressed by examining the recycling E-cadherin. After exposure to thapsigargin for 30 h, ∼30% of the total Triton X-100-soluble E-cadherin molecules were glycosylated (Figure 2A). Between 18 and 30 h, the amount of E-cadherin biotinylated on the cell surface is about half that at earlier time points (Figure 2B). Thus, if glycosylation occurs after E-cadherin molecules are transported to the cell surface and leads to internalization, then ∼30% of the biotin-labeled E-cadherin should be glycosylated. To ensure that we could detect modification of <15% of the total Triton X-100-soluble E-cadherin in the cell (30% of 50%), the blot was overexposed deliberately: no larger forms were seen (Figure 2C), indicating that glycosylated E-cadherin is not present on the cell surface.

As expected, about half of the E-cadherin in the cell is insoluble in Triton X-100 because it has assembled into adhesion sites and is bound to the cytoskeleton. However, consistent with a block in cell surface transport during thapsigargin-induced apoptosis, glycosylated E-cadherin molecules were not found in the insoluble fraction (Figure 2D).

To confirm that the modification occurred on newly synthesized rather than recycled E-cadherin, pulse–chase experiments were performed. E-cadherin molecules synthesized ([35S]methionine labeled) before addition of the drug (Figure 2E, lanes 1–4) were not modified by subsequent addition of thapsigargin. In contrast, some E-cadherin labeled during the period 20–24 or 26–30 h after adding thapsigargin was glycosylated (Figure 2E, compare lanes 3 and 4 with 7 and 8). Consistent with the immunoblots in Figure 2A, 30–40% of the E-cadherin synthesized 26–30 h after adding thapsigargin was glycosylated (Figure 2E, lane 8). This time course is similar to the alterations we noted for cell morphology and loss of cell surface staining for E-cadherin (Figure 1).

Treatment with thapsigargin did not significantly reduce the rate of synthesis of E-cadherin, as Triton X-100-soluble E-cadherin was not decreased (Figure 2A and E, lanes 5–8), and total cellular E-cadherin was also unchanged (Figure 2D). Therefore, for at least 30 h, the rate of E-cadherin turnover is not grossly altered by thapsigargin.

To determine whether glycosylation of E-cadherin resulted in a total or selective block in cell surface transport, cells were treated with ceramide for 6 h or thapsigargin for 30 h, pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine during the last 4 h, and then cell surface proteins were biotinylated. Only non-glycosylated protein was biotinylated (Figure 2F). The fact that non-glycosylated and glycosylated E-cadherin synthesized at the same time were transported differentially to the cell surface confirms that the block is selective and that bulk cell surface transport is not inhibited by ceramide or thapsigargin.

Although most obvious for the ceramide panel of the figure, a small amount of glycosylated E-cadherin is detectable after estrogen depletion, but before drug treatment. While the significance of this is unknown, these molecules are not transported to the cell surface as they were not biotinylated. Both glycosylation and degradation of E-cadherin are accelerated in ceramide-treated cells compared with thapsigargin treatment.

These data suggest that newly synthesized E-cadherin is glycosylated and enters an intracellular pool that is not transported to the cell surface or assembled into the cytoskeleton, thereby decreasing the amount of E-cadherin on the cell surface (Figures 1 and 2B), and reducing intercellular adhesion.

E-cadherin and β-catenin are O-glycosylated

What is the modification that causes the change in electrophoretic mobility of E-cadherin? Stimulation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor mediates tyrosine phosphorylation of catenins in breast cancer, decreasing cell adherence (Daniel and Reynolds, 1997). However, we could not detect thapsigargin-induced changes in the phosphorylation of E-cadherin, α-, β-, γ- or p120-catenin by cell labeling with 32P or immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies (data not shown). In contrast, precipitation of cell lysates with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)–agarose indicated that the E-cadherin molecules with slower electrophoretic mobility were O-glycosylated (Figure 3A, top left panel). WGA binds to several carbohydrate structures. However, of the known cytoplasmic glycans, it is specific for O-GlcNAc (Hart, 1997).

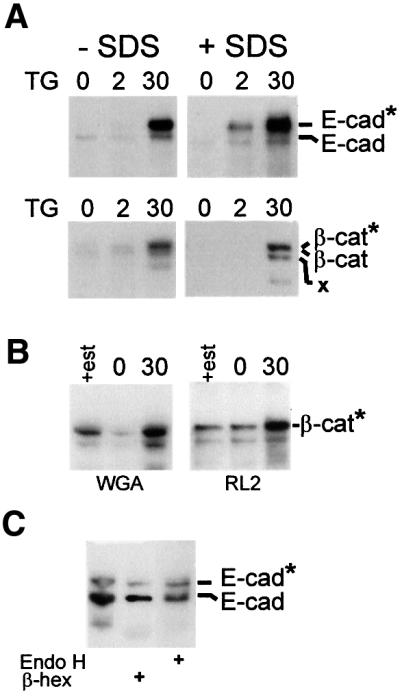

Fig. 3. Cytoplasmic O-glycosylation of E-cadherin and β-catenin during apoptosis. (A) Binding of E-cadherin and β-catenin to WGA increases during apoptosis. MCF-7 cells were incubated for the indicated time after thapsigargin, and then lysed in Triton X-100 (–SDS) or incubated in 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.4% sodium deoxycholate, 0.3% SDS, 1% NP-40 to dissociate protein complexes. After incubation with WGA–agarose, beads were washed with the same buffer, and the precipitated proteins separated by SDS–PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to E-cadherin (top panels) or β-catenin (bottom panels). The migration positions of E-cadherin and β-catenin are indicated; * designates the migration position of the glycosylated forms of the molecules. X indicates a breakdown product of β-catenin seen in some but not all experiments. (B) Thapsigargin increased binding of β-catenin to a monoclonal antibody directed towards O-GlcNAc on some proteins. Cells were treated with thapsigargin for 30 h and Triton X-100-soluble proteins were precipitated with WGA–agarose or after incubation with mAb RL2 with protein G–Sepharose. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting for β-catenin. (C) The modified form of E-cadherin is digested preferentially by β-hexosaminidase. E-cadherin was precipitated from Triton X-100 cell lysates of cells treated for 30 h with thapsigargin using a monoclonal antibody; the precipitated products were incubated with either β-hexosaminidase (β-hex) or endoglycosidase H (Endo H). After incubation with these enzymes overnight, the products were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. Although all three lanes come from the same experiment, contaminating protease activity in reactions containing β-hexosaminidase resulted in digestion of some of the E-cadherin and, therefore, a longer exposure of lane 2 of the blot to film was necessary to visualize the bands at approximately the same density as the proteins incubated with endoglycosidase H.

We also tested the possibility that precipitation with WGA is due to O-GlcNAc modification of a binding protein rather than E-cadherin. Among the catenins that complex with E-cadherin, only β-catenin was O-glycosylated in response to thapsigargin treatment (Figure 3A, bottom panel; and data not shown). Since this protein is present only inside the cell, binding to WGA is compelling evidence for modification by O-GlcNAc. Furthermore, both the modified E-cadherin and β-catenin proteins remained bound to WGA after incubation in a buffer containing 0.3% SDS to disrupt interactions between catenins and E-cadherin (Figure 3A, +SDS), indicating that both proteins are modified directly and that precipitation with WGA–agarose is not due to another glycosylated protein that binds to the complex. Based on the size of the mobility shift of E-cadherin, it is likely that it is multiply modified, as has been reported for other proteins (Comer and Hart, 2000), although a change in the structure of the protein that affects migration cannot be excluded.

To confirm that the modification is cytoplasmic O-GlcNAc, we used two monoclonal antibodies (RL2 and HGAC85) each known to bind to some but not all O-GlcNAc-modified proteins. One of these antibodies (RL2) bound efficiently to modified β-catenin, confirming the presence of O-GlcNAc (Figure 3B). However, since these antibodies recognize only specific patterns of O-GlcNAc, lack of an interaction with modified E-cadherin does not indicate that it is not O-glycosylated. Consistent with the modification on E-cadherin being O-GlcNAc, it was partially digested using β-hexosaminidase (Figure 3C). However, we interpret these results cautiously as there was some contamination of the enzyme with protease and we cannot determine easily if the glycosylated and non-glycosylated E-cadherin differ in their sensitivity to this protease. As expected, the modification was resistant to digestion with endoglycosidase H (Figure 3C), an enzyme that digests high-mannose carbohydrates added to the extracellular domain of transmembrane proteins while in the ER. The modification was also resistant to N-glycosidase F and O-glycanase (data not shown). Resistance to N-glycosidase F confirms that the alteration was not due to N-linked glycosylation of the extracellular domain of E-cadherin. O-glycanase does not cleave O-GlcNAc added cytoplasmically, but removes O-Gal β(1–3) GalNAc from O-glycans bound to serine or threonine. These O-glycans constitute the other major class of carbohydrates on extracellular domains of transmembrane proteins. These results clearly indicate that cytoplasmic O-glycosylation of β-catenin occurs after 30 h exposure to thapsigargin and that the same modification is the most likely for E-cadherin.

Glycosylation of E-cadherin is caspase dependent

E-cadherin is a known substrate for caspases, and caspase inhibition with zVAD-fmk mitigated the loss of cell surface E-cadherin (Figure 1). However, the increase in apparent molecular weight of E-cadherin is not consistent with cleavage by a caspase. Nevertheless, both aldehyde- and fluromethyl ketone-based caspase inhibitors prevent the modification of E-cadherin (Figure 4A). Use of selective inhibitors suggests that the caspase-1 family may be more important, as YVAD-CHO was more potent than DEVD-CHO or DEVD-fmk (Figure 4A). However, we cannot rule out differences in cellular uptake contributing to the dose dependence. Control experiments (not shown) demonstrated that there was no significant difference with aldehyde- or fluromethyl ketone-based inhibitors. Thus, the effect is due to inhibition of caspases rather than non-specific inhibition of the O-GlcNAc transferase by either fluromethyl ketone or aldehyde. Because caspases are proteases, a caspase-dependent increase in molecular weight suggests that the caspase is acting indirectly.

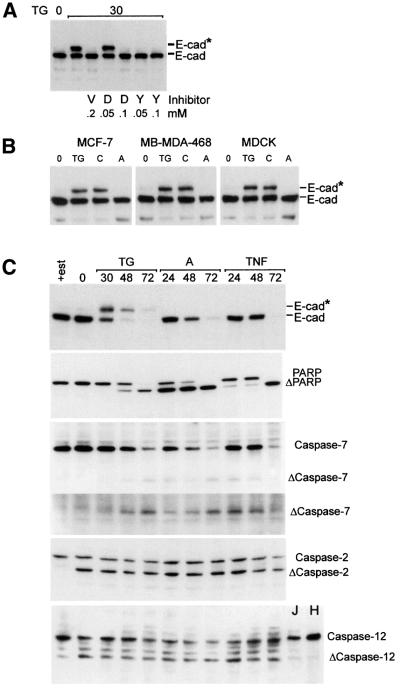

Fig. 4. (A) Modification of E-cadherin in response to thapsigargin is blocked by the caspase inhibitors zVAD-fmk (V), DEVD-CHO (D) and YVAD-CHO (Y). After the addition of thapsigargin, MCF-7 cells were incubated in the indicated concentration of inhibitor for 30 h, lysed in Triton X-100, analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted for E-cadherin. Identical results were obtained using DEVD-fmk and YVAD-fmk (not shown). The migration positions of E-cadherin (E-cad) and modified E-cadherin (E-cad*) are indicated to the right of the panels. (B) E-cadherin is O-glycosylated in MCF-7, MB-MDA-468 and MDCK cells when apoptosis is induced by thapsigargin (TG) or C2-ceramide (C) but not adriamycin (A). After the addition of thapsigargin, C2-ceramide or adriamycin, cells were incubated for 30, 6 or 18 h, respectively, and then lysed in Triton X-100 and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. None of the cell lines were estrogen depleted prior to drug treatment. The migration positions of E-cadherin (E-cad) and modified E-cadherin (E-cad*) are indicated to the right. (C) Degradation of E-cadherin correlates with activation of caspase-7. Cells were incubated in thapsigargin (TG), adriamycin (A) or TNF-α/cycloheximide (TNF) for the times indicated, lysed in Triton X-100 and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies to E-cadherin (E-cad), PARP, caspase-7, caspase-2 or caspase-12. Migration positions for the relevant proteins and their cleavage products are illustrated to the right. A longer exposure of the Δcaspase-7 region of the blot is also provided to facilitate visualization of the primary cleavage product. The monoclonal antibody for rodent caspase-12 recognizes a single protein species in untreated MCF-7, Jurkat (J) and HL60 (H) cells. Caspase-2 and the ‘caspase-12-like’ protein are cleaved when cells are grown in estrogen-depleted medium (Δcaspase-2, Δcaspase-12, respectively).

To sensitize MCF-7 cells to apoptosis, we grew them in estrogen-depleted medium prior to analysis. To determine if O-glycosylation of E-cadherin requires estrogen deprivation, and is unique to either MCF-7 cells or treatment with thapsigargin, we tested two other cell lines (MDCK and MB-MDA-468) and two other drugs (adriamycin and ceramide). E-cadherin was O-glycosylated in MCF-7 cells grown in regular medium, as well as in MDCK and MB-MDA-468 cells exposed to thapsigargin or ceramide, but not adriamycin (Figure 4B). Identical results were obtained with β-catenin (data not shown). Moreover, thapsigargin induced glycosylation of β-catenin in MRC-5 cells, a human fibroblast cell line that does not express E-cadherin (data not shown). Thus, O-glycosylation is regulated in multiple cell types in response to at least two stimuli.

We have shown that thapsigargin and ceramide activate apoptosis via a pathway that involves the ER, while adriamycin induces cell death via activation of Bax and release of cytochrome c at mitochondria (Annis et al., 2000; Soucie et al., 2001). If O-glycosylation of E-cadherin is restricted to the ER stress pathway of apoptosis, then how is intercellular adhesion lost in other forms of apoptosis? We examined changes to E-cadherin over extended times in MCF-7 cells treated with either thapsigargin or the mitochondria-specific agonists adriamycin and TNF-α. Only thapsigargin caused the early modification of E-cadherin; all three agents cause degradation of E-cadherin at later times (Figure 4C). Consistent with proteolysis being mediated by caspases, cleavage of PARP and caspase-7 was noted at the same time (Figure 4C). MCF-7 cells lack caspase-3; therefore, caspase-7 is a good candidate for mediating the degradation of E-cadherin. These results are consistent with previous observations in which cell death via the ER-localized pathway is upstream of the mitochondrial pathway (Zhu et al., 1996; Annis et al., 2000; Soucie et al., 2001). Thus, intercellular adhesion can be down-regulated during apoptosis by two separate mechanisms with different kinetics.

To identify a candidate caspase responsible for increasing O-glycosylation of E-cadherin, we examined cleavage of other caspases associated with the ER and/or Golgi complex (Zhivotovsky et al., 1999; Mancini et al., 2000). Passage of cells in estrogen-depleted medium was sufficient to induce cleavage of caspase-2 (Figure 4C), even though cells retain full growth potential after re-addition of estrogen, demonstrating that cleavage of caspase-2 does not commit cells to apoptosis. Similar results were observed using an antibody against rodent caspase-12 (Figure 4). The human genome does not contain a precise homolog for caspase-12. Therefore, the identity of the ‘caspase-12-like’ protein detected with antibody to rodent caspase-12 is unknown. Nevertheless, a single band is seen in lysates of MCF-7, Jurkat and HL6, and the smaller fragment detected after estrogen depletion is consistent with protein cleavage. Therefore, we presume that the epitope recognized by the antibody is preserved in a human caspase. Addition of agents that commit cells to die did not lead to a dramatic increase in the cleavage of caspase-2 or ‘caspase-12’ (Figure 4). Therefore, although these caspases are potentially active in these cells, cleavage does not correlate with the modification.

Glycosylated E-cadherin binds to β- and γ-catenin but not p120-catenin

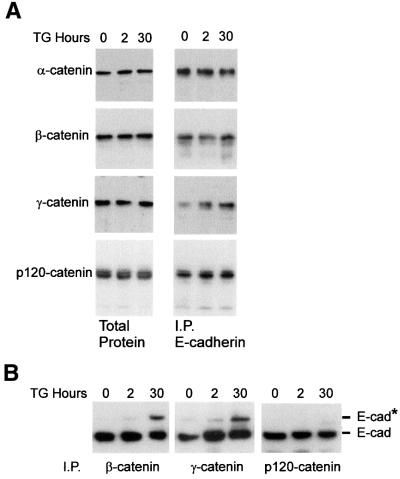

Complex formation between E-cadherin and β-catenin has been linked to exit from the ER, transport to the plasma membrane (Chen et al., 1999) and E-cadherin turnover (Huber et al., 2001). Therefore, one explanation for the block in cell surface transport of O-glycosylated E-cadherin might be lack of binding to catenins. The amount of α-, β- and p120-catenin bound to E-cadherin, assayed by immunoprecipitation with antibodies to E-cadherin and blotting for α-, β- and p120-catenin, does not change dramatically during thapsigargin-induced apoptosis (Figure 5A). With this method, quantification of small changes would not be accurate. However, the data shown are representative of at least six independent experiments. There is surprisingly little γ-catenin bound to E-cadherin in MCF-7 cells after estrogen depletion, with a small but reproducible increase after adding thapsigargin (Figure 5A). However, this increased binding does not increase appreciably the amount of α-catenin bound to E-cadherin, and therefore is unlikely to have a significant effect on adhesion.

Fig. 5. E-cadherin–catenin binding during apoptosis. (A) E-cadherin continues to bind to catenins during thapsigargin (TG)-induced apoptosis. After the addition of thapsigargin, MCF-7 cells were incubated for the indicated time and then lysed in Triton X-100 and analyzed either directly (Total Protein) or after immunoprecipitation with antibodies to E-cadherin (I.P. E-cadherin). Samples were separated by SDS–PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane and immunoblotted with the indicated antibody. (B) Glycosylated E-cadherin binds β- and γ-catenin but not p120-catenin. After the addition of thapsigargin, MCF-7 cells were incubated for the indicated time and then lysed in Triton X-100 and, after immunoprecipitation with antibodies to β-, γ- or p120-catenin, analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting for E-cadherin. The migration positions of E-cadherin (E-cad) and modified E-cadherin (E-cad*) are indicated to the right of the panels.

It is possible that the reason that we do not detect significant changes in catenin binding to E-cadherin is that only ∼30% of the E-cadherin is glycosylated after 30 h exposure to thapsigargin. To determine if glycosylated E-cadherin forms complexes with β-, γ- or p120-catenin, we immunoprecipitated the Triton X-100-soluble fraction with antibodies to catenins and then blotted for E-cadherin, as modified E-cadherin is detected only in this fraction (Figure 2D). Glycosylated E-cadherin still binds to both β- and γ-catenin, albeit with slightly reduced efficiency. Thus, glycosylation of E-cadherin does not block intracellular complex formation (Figure 5B). However, antibodies to p120-catenin precipitated only the unmodified form of E-cadherin. Therefore, O-glycosylation prevents p120-catenin binding to E-cadherin. Consistent with this result, a mutant E-cadherin lacking the entire binding region for α- and β-catenin but retaining 80 amino acids of the cytoplasmic domain in the juxta membrane region that binds p120-catenin was O-glycosylated in response to thapsigargin (data not shown).

Discussion

As cell adhesion is re-organized dramatically during apoptosis, novel regulatory mechanisms may be involved. Proteolytic cleavage of E-cadherin, β- and γ-catenin have been identified as irreversible modifications that occur during programmed cell death. To analyze alterations in cell surface E-cadherin, we devised a method for quantitative analysis of cell surface proteins by confocal microscopy, and confirmed results with biotinylation and immunoblotting. Down-regulation of adhesion during apoptosis induced by thapsigargin or ceramide is achieved rapidly via a caspase-dependent block in transport of E-cadherin, which is substantially faster than the caspase-mediated degradation of E-cadherin or catenins. Furthermore, the reversible nature of O-GlcNAc addition permits dynamic regulation by distinct glycosyltransferases and glycosidases (Hart, 1997; Comer and Hart, 2000). Although up-regulation of O-glycosylation is a novel function for caspases, there are precedents for caspases mediating their effects by activating other enzymes (Sakahira et al., 1998). Our data do not allow us to distinguish between the activation of the recently cloned O-GlcNAc transferase or proteolysis of the glycosidase (Hart, 1997; Kreppel et al., 1997; Lubas et al., 1997; Gao et al., 2001). However, immunoblots for the O-GlcNAc transferase showed no change in mobility or abundance after thapsigargin treatment (data not shown). The lack of available antibodies precluded examination of the glycosidase.

The glycosylation of E-cadherin and β-catenin fits well with previous suggestions for an intriguing parallel between O-glycosylation and phosphorylation–dephosComer and Hart, 2000). Caspase-mediated inactivation of the glycosidase could lead to O-glycosylation of both E-cadherin and β-catenin in the same way that inactivation of relatively non-specific phosphatases leads to phosphorylation of some specific proteins. Talin is also O-glycosylated, and controls the progress of α5β1 integrin through the secretory pathway, another interesting parallel to our findings (Hagmann et al., 1992; Martel et al., 2000). Regardless of the specific mechanism, our data indicate that O-glycosylation is up-regulated in an intracellular compartment, and prevents the interaction of E-cadherin with p120-catenin. It is unlikely that lack of p120-catenin binding directly blocks cell surface transport of E-cadherin, as mutants of E-cadherin that do not bind p120-catenin still traffic to the cell surface where they can contribute to adhesion, albeit weakly (Thoreson et al., 2000). Thus, it appears that the block in the association of E-cadherin with the cytoskeleton is an indirect consequence of the block in cell surface transport rather than lack of binding to p120-catenin.

Preliminary experiments suggest that an 80 amino acid juxtamembrane region encompassing the p120-catenin-binding site is the site of O-GlcNAc addition (data not shown). It is possible that addition of O-GlcNAc directly interferes with binding of p120-catenin, but the region contains only one serine and one threonine, and neither is conserved nor implicated in binding to p120-catenin (Thoreson et al., 2000). Therefore, the O-GlcNAc added to E-cadherin may alter its conformation such that it no longer binds p120-catenin, or induce the binding of some other blocking factor.

Inhibition of E-cadherin binding to p120-catenin would increase the amount of p120-catenin in the cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic p120-catenin inhibits RhoA, leading to disruption of stress fibers and focal adhesions (Anastasiadis et al., 2000). If inhibition of Rho was the primary mechanism, then intracellular transport of E-cadherin should be inhibited independently of O-glycosylation status. However, transport is blocked for only the O-glycosylated molecules (Figure 2F), suggesting a direct role for the modification in regulating cell surface transport.

Regulation of O-glycosylation is widespread but not ubiquitous in apoptosis. Cytoplasmic O-glycosylation was induced by exposure to either thapsigargin or ceramide, two drugs that activate a pathway localized at the ER (Annis et al., 2000; Soucie et al., 2001). In contrast, O-glycosylation of E-cadherin was not observed in response to cell death induced by adriamycin or TNF-α. Rather than the ER pathway, these agents target mitochondria via translocation of Bax and early cytochrome c release (Soucie et al., 2001). Loss of intercellular adhesion occurs later in this pathway by caspase degradation of E-cadherin (Figure 4).

Glycosylation of E-cadherin and β-catenin was observed in MCF-7, MDCK, MB-MDA-468 and MRC-5 cells (Figure 4B and data not shown). It remains a matter of speculation whether cadherins and/or catenins are glycosylated in other circumstances and whether caspases regulate O-glycosylation more widely. We detected a small amount of the glycosylated E-cadherin, and cleavage of caspase-2 and ‘caspase-12’ in MCF-7 deprived of estrogen (Figure 2F), a stress that does not commit cells to apoptosis. There are other precedents for caspase-mediated processes that are not restricted to apoptosis (Los et al., 2001). Thus, it will be important to determine if the cell surface transport of molecules other than E-cadherin can be regulated by O-glycosylation and to determine if other cytoplasmic O-glycosylation events (e.g. nuclear pore proteins) are regulated by caspases.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human breast cancer cells MDA-MB-468 (ATCC) were grown in Leibvitz’s L-15 medium with 2 mM l-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). MCF-7, canine kidney epithelial (MDCK) and MRC5 cells were grown in α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS. A plasmid encoding GFP–Rab5 (generous gift of Dr S.Ferguson, Robarts Institute) was transiently transfected into MCF-7 cells using ExGen 500 (MBI Fermentas) and expression monitored 48 h later. Thapsigargin (Sigma) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 40 µM, and diluted to a final concentration of 400 nM in culture medium. Ceramide (Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO and used at a final concentration of 100 µM. TNF-α was added to cells at a final concentration of 9 ng/ml together with 10 µg/ml cycloheximide, and adriamycin at 5.8 mg/ml. To reduce expression of endogenous Bcl-2, MCF-7 cells were grown in α-MEM without phenol red and supplemented with charcoal-filtered FBS for 6 days before each experiment, unless specified otherwise. The caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (Enzyme Systems Products) was dissolved in DMSO at 20 mM and added to cell culture medium to the indicated final concentration. Caspase inhibitors that preferentially inhibit caspase-3 type (zDEVD-fmk and Ac-DEVD-CHO, Calbiochem) and caspase-1 type (zYVAD-fmk and Ac-YVAD-CHO, Calbiochem) were dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM and added 1 h before adding thapsigargin, with subsequent additions every 12 h. To biotin-label cell surface proteins, EZ-Link™ Biotin [sulfosuccinimidyl 6-(biotinamido)hexanoate; Pierce] dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 0.5 mg/ml was added to cells for 30 min before or after tharpsigargin, as specified. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to O-linked GlcNAc glycoproteins (clones RL2 and HGAC85) were obtained from Affinity Bioreagents Inc. WGA–agarose was from Sigma. Endoglycosidase H and PNGase F were from New England BioLabs. β-N-Acetylhexosaminidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase were from V-Labs.

Antibodies

The antibodies for immunoblots (mouse mAbs to E-cadherin, α-catenin, β-catenin, γ-catenin and p120-catenin) were purchased from Transduction Laboratories. For immunoprecipitation, the same β-catenin antibody was used but for γ-catenin a polyclonal antibody (generous gift of Dr M.Pasdar) was used. mAb to caspase-12 was the generous gift of Dr J.Yuan. For immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence analysis of E-cadherin, an mAb to the extracellular domain was purchased from Zymed. The PARP mAb, clone C2-10, was from Biomol Research Laboratories, mAb Py-20 from ICN and peroxidase-conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine cocktail antibody PY-Plus from Zymed. Antibodies to caspase-2 and caspase-7 were from Ex-Alpha Biologicals.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

For immunoprecipitation, 1 × 107 cells were incubated in 1.5 ml of lysis buffer (LB) [10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 80 ng/ml aprotinin, 40 ng/ml chymostatin, 40 ng/ml antipain, 40 ng/ml leupeptin, 40 ng/ml pepstatin] for 15 min on ice, and passed through a 26 gauge needle four times. Cellular debris and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 13 000 r.p.m. for 10 min in a microcentrifuge. Protein concentration was determined for the supernatant using a BCA assay (Pierce), and 100 µg of total protein from each sample was immunoprecipitated with 1 µg of either anti-E-cadherin or anti-β-catenin antibody. Protein G–Sepharose (100 µl of 10% slurry in LB) (Pharmacia) was added, and samples were mixed by rotation for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were pelleted and washed three times. For binding with WGA–agarose beads (Sigma), 100 µg of total protein was incubated with beads, samples mixed by rotation, and beads pelleted then washed with LB or a buffer containing SDS that dissociates E-cadherin from β-catenin and γ-catenin (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.4% sodium deoxycholate, 0.3% SDS, 1% NP-40). In control experiments, E-cadherin lysates were prepared from [35S]methionine-labeled cells, incubated and immunoprecipitated in the above buffer or LB. Comparison of the bands obtained after SDS–PAGE demonstrated co-precipitation of catenins and E-cadherin only in LB.

For biotin-labeled cells, 30 µl of streptavidin-conjugated paramagnetic particles (Promega) was added to 70 µg of protein, mixed for 1 h at 4°C and washed three times with dissociation buffer. The beads were collected using a paramagnetic isolator and proteins released by incubation in SDS–PAGE loading buffer. After SDS–PAGE and transfer to PVDF (Gelman), the membranes were incubated with antibodies and developed using donkey secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Laboratories) and an enhanced chemiluminescent detection system (NEN-life Science). For immunoblotting, cells were lysed in WB lysis buffer (1.5 ml: 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, 2 mM PMSF, 80 ng/ml aprotinin, 40 ng/ml chymostatin, 40 ng/ml antipain, 40 ng/ml leupeptin, 40 ng/ml pepstatin), 10 µg of protein were loaded in each lane and subjected to electrophoresis using a Tris-tricine buffer.

To separate cytoskeleton-binding proteins from other cell constituents, cells were washed twice in PBS, lysed on ice for 15 min in CSK buffer (1.0 ml: 300 mM sucrose, 10 mM PIPES pH 6.8, 50 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml DNase, 0.1 mg/ml RNase, 1.2 mM PMSF and the same protease inhibitor mix as WB lysis buffer), passed through a 26 gauge needle four times, then subjected to centrifugation at 48 000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was solubilized in loading buffer containing 10% SDS, and supernatant and pellet fractions with equivalent cell numbers (40 000) were loaded on separate gels and processed as above.

To assay digestion with glycosidases, E-cadherin was immunoprecipitated from 200 µg of total protein in LB and washed three times, beads washed twice in 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, and proteins released by incubation in 0.1 M glycine pH 2.5 and neutralized with Tris buffer or incubated with the enzymes while still bound to beads. After digestion in solution, E-cadherin was immunoprecipitated, separated by SDS–PAGE and visualized by immunoblotting. After digestion on beads, the beads were washed twice in buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.4% sodium deoxycholate, 0.3% SDS, 1% NP-40) and twice in LB before SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. Similar results were obtained with either procedure. Digestion with β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase in 50 mM sodium citrate pH 5.0 (3 U of enzyme) for 18 h at 37° C resulted in complete digestion of E-cadherin due to contaminating protease. Digestion with β-N-acetylhexosaminidase in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.0 (3 U of enzyme) for 18 h at 37°C resulted in preferential digestion of O-GlcNAc from E-cadherin although there was also some loss of protein due to contaminating protease. Incubation with the other glycosidases (according to the manufacturer’s directions) had no effect on unmodified or O-glycosylated E-cadherin.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were seeded on coverslips and grown as described (Zhu et al., 1996) except that non-permeabilized cells were washed twice in PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then incubated with antibodies. To permeabilize cells, they were incubated with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, incubated at 37°C for 1 h with E-cadherin antibody (dilution, 1:10 000), washed and incubated for 1 h with fluorescent secondary antibodies (Jackson Laboratories; dilution, 1:30) and observed by confocal microscopy (Zhu et al., 1996). For quantitative microscopy, cells were stained with Syto-63, washed and fixed as above, then stained for E-cadherin using a mouse mAb and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled secondary antibodies. To include a relevant area of a cell in a single section, the pinhole was opened until a depth of focus of 3.5 µm was obtained. Images were recorded through the center of the cells for a complete set of images using a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope without changing amplifier or laser settings between slides or cell treatments. Image analysis was performed automatically using Kontron image analysis software. Control experiments demonstrated that automatic and manual thresholding yielded indistinguishable results; therefore, automatic thresholding was used throughout.

Metabolic labeling

Cells were grown for 6 days in estrogen-replete culture medium. Thapsigargin (400 nM) was added to the dishes for 0–30 h; 300 µCi of [35S]methionine was added either for 24 h before addition of thapsigargin, or for four discrete 4 h blocks within the 30 h period of thapsigargin exposure (0–4, 8–12, 20–24 and 26–30 h). At the relevant time points, the radioactively labeled medium was aspirated and replaced with fresh medium containing cold methionone and thapsigargin. After further incubation until the total incubation time was 30 h, cells were washed in PBS, lysed on ice for 15 min in 1 ml of WB lysis buffer, passed through a 26 gauge needle four times and subjected to centrifugation at 15 000 r.p.m. in a microfuge for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were processed for immunoprecipitation as described above, resolved by SDS–PAGE, and gels exposed to X-ray film.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Antisera were generously provided by Drs R.Youle, M.Pasdar, J.Yuan and G.Hart. The plasmid encoding Rab5GFP was provided by Dr S.Ferguson. Funding for this research was provided by a CIHR grant to D.W.A. and B.L. D.W.A. holds the Canada Research Chair in Membrane Biogenesis.

References

- Anastasiadis P.Z., Moon,S.Y., Thoresen,M.A., Mariner,D.J., Crawford,H.C., Zheng,Y. and Reynolds,A.B. (2000) Inhibition of RhoA by p120 catenin. Nature Cell Biol., 2, 637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annis M., Zamzami,N., Zhu,W., Penn,L.Z., Kroemer,G., Leber,B. and Andrews,D.W. (2000) Endoplasmic reticulum localized Bcl-2 prevents apoptosis when redistribution of cytochrome c is a late event. Oncogene, 20, 1939–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.T., Stewart,D.B. and Nelson,W.J. (1999) Coupling assembly of the E-cadherin/β-catenin complex to efficient endoplasmic reticulum exit and basal–lateral membrane targeting of E-cadherin in polarized MDCK cells. J. Cell Biol., 144, 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer F.I. and Hart,G.W. (2000) O-Glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Dynamic interplay between O-GlcNAc and O-phosphate. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 29179–29182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J.M. and Reynolds,A.B. (1997) Tyrosine phosphorylation and cadherin/catenin function. Bioessays, 19, 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M.L., Zhao,X., Vallorosi,C.J., Putzi,M., Powell,C.T., Lin,C. and Day,K.C. (1999) E-cadherin mediates aggregation-dependent survival of prostate and mammary epithelial cells through the retinoblastoma cell cycle control pathway. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 9656–9664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch S.M. and Ruoslahti,E. (1997) Integrins and anoikis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 9, 701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Wells,L., Comer,F.I., Parker,G.J. and Hart,G.W. (2001) Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: cloning and characterization of a neutral, cytosolic β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from human brain. J.Biol. Chem., 276, 9838–9845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner B.M. (2000) Regulation of cadherin adhesive activity. J. Cell Biol., 148, 399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann J., Grob,M. and Burger,M.M. (1992) The cytoskeletal protein talin is O-glycosylated. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 14424–14428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart G.W. (1997) Dynamic O-linked glycosylation of nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 66, 315–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herren B., Levkau,B., Raines,E.W. and Ross,R. (1998) Cleavage of β-catenin and plakoglobin and shedding of VE-cadherin during endothelial apoptosis: evidence for a role for caspases and metalloproteinases. Mol. Biol. Cell, 9, 1589–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber A.H., Stewart,D.B., Laurents,D.V., Nelson,W.J. and Weis,W.I. (2001) The cadherin cytoplasmic domain is unstructured in the absence of β-catenin: a possible mechanism for regulating cadherin turnover. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 12301–12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreppel L.K., Blomberg,M.A. and Hart,G.W. (1997) Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 9308–9315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T.L., Yap,A.S. and Stow,J.L. (1999) Recycling of E-cadherin: a potential mechanism for regulating cadherin dynamics. J. Cell Biol., 146, 219–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los M., Reiner,C.S., Ingo,U.J., Engel,H. and Schulze-Osthoff,K. (2001) Caspases: more than just killers? Trends Immunol., 22, 31–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubas W.A., Frank,D.W., Krause,M. and Hanover,J.A. (1997) O-Linked GlcNAc transferase is a conserved nucleocytoplasmic protein containing tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 9316–9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M., Machamer,C.E., Roy,S., Nicholson,D.W., Thornberry,N.A., Casciola-Rosen,L.A. and Rosen,A. (2000) Caspase-2 is localized at the Golgi complex and cleaves golgin-160 during apoptosis. J. Cell Biol., 149, 603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel V., Vignoud,L., Dupe,S., Frachet,P., Block,M.R. and Albiges-Rizo,C. (2000) Talin controls the exit of the integrin α5β1 from an early compartment of the secretory pathway. J. Cell Sci., 113, 1951–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo T. and Ozawa,M. (1999) p120(ctn) binds to the membrane-proximal region of the E-cadherin cytoplasmic domain and is involved in modulation of adhesion activity. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 21409–21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X.M., He,H., Zhong,H. and Distelhorst,C.W. (1997) Baculovirus p35 and Z-VAD-fmk inhibit thapsigargin-induced apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Oncogene, 15, 1207–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakahira H., Enari,M. and Nagata,S. (1998) Cleavage of CAD inhibitor in CAD activation and DNA degradation during apoptosis. Nature, 391, 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucie E.L., Annis,M.G., Sedivy,J., Filmus,J., Leber,B., Andrews,D.W. and Penn,L.Z. (2001) Myc potentiates apoptosis by stimulating Bax activity at the mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 4725–4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira C., Reed,J.C. and Pratt,M.A. (1995) Estrogen promotes chemotherapeutic drug resistance by a mechanism involving Bcl-2 proto-oncogene expression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res., 55, 3902–3907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson M.A., Anastasiadis,P.Z., Daniel,J.M., Ireton,R.C., Wheelock,M.J., Johnson,K.R., Hummingbird,D.K. and Reynolds,A.B. (2000) Selective uncoupling of p120ctn from E-cadherin disrupts strong adhesion. J. Cell Biol., 158, 189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallorosi C.J., Day,K.C., Zhao,X., Rashid,M.G., Rubin,M.A., Johnson,K.R., Wheelock,M.J. and Day,M.L. (2000) Truncation of the β-catenin binding domain of E-cadherin precedes epithelial apoptosis during prostate and mammary involution. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 3328–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhivotovsky B., Samali,A., Gahm,A. and Orrenius,S. (1999) Caspases: their intracellular location and translocation during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ., 6, 644–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Cowie,A., Wasfy,G.W., Penn,L.Z., Leber,B. and Andrews,D.W. (1996) Bcl-2 mutants with restricted subcellular location reveal spatially distinct pathways for apoptosis in different cell types. EMBO J., 15, 4130–4141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]