Abstract

Aspergillus nidulans possesses two high-affinity nitrate transporters, encoded by the nrtA and the nrtB genes. Mutants expressing either gene grew normally on 1–10 mM nitrate as sole nitrogen source, whereas the double mutant failed to grow on nitrate concentrations up to 200 mM. These genes appear to be regulated coordinately in all growth conditions, growth stages and regulatory genetic backgrounds studied. Flux analysis of single gene mutants using 13NO3– revealed that Km values for the NrtA and NrtB transporters were ∼100 and ∼10 µM, respectively, while Vmax values, though variable according to age, were ∼600 and ∼100 nmol/mg dry weight/h, respectively, in young mycelia. This kinetic differentiation may provide the necessary physiological and ecological plasticity to acquire sufficient nitrate despite highly variable external concentrations. Our results suggest that genes involved in nitrate assimilation may be induced by extracellular sensing of ambient nitrate without obligatory entry into the cell.

Keywords: Aspergillus nidulans/ecological plasticity/genetic redundancy/nitrate assimilation/nitrate transport

Introduction

When two or more gene products carry out the same function, and mutation in one of these genes has no detectable effect on the biological phenotype, the genes are said to be redundant (Brookfield, 1997). It is likely that true redundancy does not exist since it is generally regarded that natural selection acts to retain only discretely functional proteins (Nowak et al., 1997). Rather, apparent redundancy may actually serve to implement changes in spatial or developmental regulation (Cadigan et al., 1994; Christophides et al., 2000; Patterson et al., 2000).

Nitrate is the major nitrogen source for most crop plants (Wray and Kinghorn, 1989; Crawford and Glass, 1998; Daniel-Vedele et al., 1998; Forde, 2000). Nitrate also acts as a signal for the control of many metabolic and morphogenic processes (Scheible et al., 1997; Zhang and Forde, 1998). In the natural environment, nitrate is probably the most ephemeral of inorganic nutrients, ranging in concentration across orders of magnitude (Vidmar et al., 2000). In addition, nitrate is readily leached from soils, contributing to eutrophication of natural water systems and simultaneously lowering nitrogen availability to land plants.

In the soil saprophytic fungus, Aspergillus nidulans, we observe two paralogous genes encoding nitrate transporters. The first eukaryotic nitrate transporter gene described, nrtA (formerly designated crnA), has acted as a paradigm for plant high-affinity transport systems (Unkles et al., 1991), and provided a springboard to the cloning and identity of orthologous Nrt2 genes from a large number of species (Quesada et al., 1994; Trueman et al., 1996; Pérez et al., 1997; Quesada et al., 1997; Amarasinghe et al., 1998; Filleur and Daniel-Vedele, 1999; Zhou et al., 1999). Indeed, a major problem confronting plant biologists now is to explain the unique roles of as many as 11 different nitrate transporter genes belonging to the Nrt1 and Nrt2 families in Arabidopsis thaliana. In contrast, nrtA and nrtB appear to be the only genes encoding nitrate transporters in A.nidulans. Both genes are induced rapidly by exposure to nitrate, are under identical regulatory control, appear to be of equivalent abundance and show the same temporal expression patterns. The cloning and sequencing of the nrtB gene and generation of mutant strains provided the opportunity to investigate the kinetic properties and relative contributions of each of the nitrate transporters, using the short-lived tracer 13NO3–.

Results

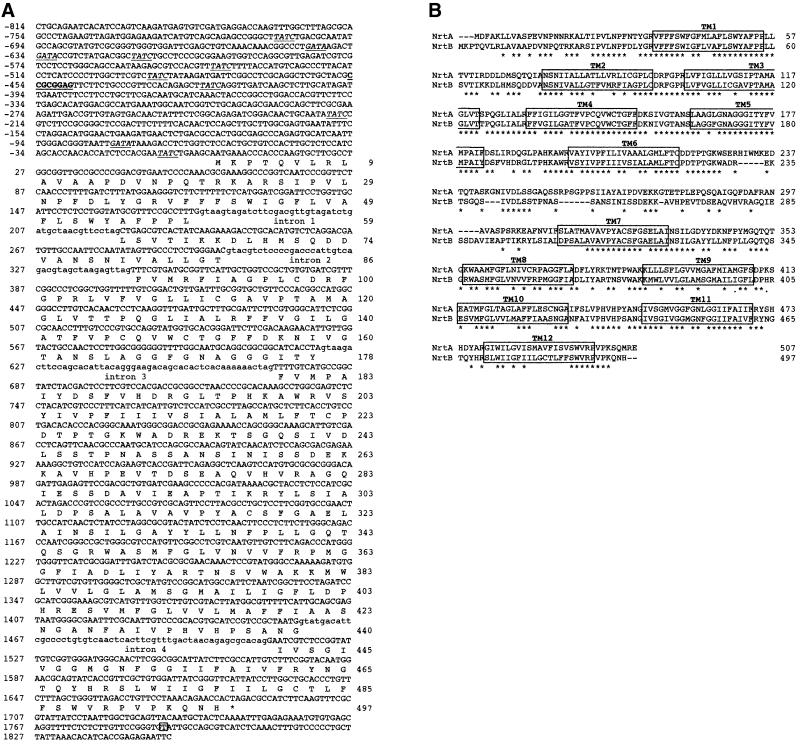

The nrtB gene structure and predicted protein

An open reading frame (ORF) of 1491 nucleotides interrupted by four putative introns is evident from the genomic DNA sequence and the inferred NrtB protein (Figure 1A). Introns 1, 2 and 4 occupy the same position as those of nrtA, with intron 3 being unique. In the nrtB 5′ region, there are potential binding sites for the NirA and AreA regulatory proteins, that mediate nitrate induction and nitrogen metabolite repression, respectively (Strauss et al., 1998; Morozov et al., 2000 and references therein). One potential NirA-binding motif (CCGCGGAG) is observed at nucleotide position –455 as well as 10 possible AreA-binding motifs (GATA). Alignment of the 497 residue NrtB (53.7 kDa) with the 507 NrtA (57 kDa) shows 76% similarity (61% identity) overall and up to 90% similarity (76% identity) over the proximal 230 residues (Figure 1B). As with NrtA, there are 12 putative transmembrane α-helical segments (Figure 1B, boxed).

Fig. 1. (A) Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the nrtB gene. Numbers to the left refer to nucleotide positions relative to the A of the proposed start codon (number +1) and numbers to the right refer to amino acid residues. Intron sequences are shown in lower case. Potential recognition motifs for regulatory proteins are shown in italics and underlined (AreA) or bold and underlined (NirA). The site of polyadenylation is boxed. (B) Comparison of deduced amino acid sequences of NrtA and NrtB. Numbers to the right indicate amino acid residues for each protein. Conservation of position by identical residues is shown by an asterisk. The 12 putative transmembrane domains are boxed.

Phenotypic analysis of mutants

Growth tests with nitrate as the sole nitrogen source showed that mutant strain nrtB110, generation of which is described in Materials and methods, grew similarly to the wild-type (and nrtA747) with nitrate from 1 to 10 mM as the sole source of nitrogen (Table I and our unpublished data). The double mutant nrtA747 nrtB110 failed to grow at nitrate concentrations up to 200 mM in minimal medium, even after prolonged incubation (our unpublished data). When caesium was included in 10 mM nitrate medium, the single mutant nrtB110 could not be distinguished from wild type, whereas growth of nrtA747 (and the double mutant nrtA747 nrtB110) was reduced markedly and similarly, as noted previously for the allele nrtA1 (formerly crnA1; Brownlee and Arst, 1983). In contrast, caesium was without effect on growth of all strains grown on 1–10 mM nitrite (Table I and our unpublished data). Chlorate toxicity tests revealed that whereas nrtA747 is highly resistant to the toxicity of 150 mM chlorate with 10 mM proline, the nrtB110 mutant (like wild type) is completely unable to grow under the same conditions (Table I). At low concentrations of chlorate such as 1 mM (with proline), where the wild type is still sensitive, nrtB110 also remains sensitive (our unpublished data).

Table I. Growth responses of wild-type and mutant strains.

| Strain | Nitrate | Nitrate + caesium | Nitrite | Nitrite + caesium | Proline +chlorate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| nrtA747 | 4 | 0/1 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| nrtB110 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| nrtA747 nrtB110 | 0 | 0/1 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| niaD171 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

All tests were carried out on minimal medium, supplemented with the substances stated above as well as vitamins (to satisfy vitamin auxotrophic requirements). For growth tests, the concentration of the nitrogen source was 10 mM. The concentration of caesium chloride was 20 mM, the concentration used in a previous study (Unkles et al., 1991), and the concentration of sodium chlorate was 150 mM. For discussion of chlorate concentrations and toxicity, see Cove (1976). A score of 0 represents ungerminated conidiospores or faint scraggly growth (i.e. none or very scant growth), and 4 a mature and conidiating colony, while 1, 2 and 3 indicate intermediate levels. Strains are discussed in the Materials and methods.

Regulation of expression

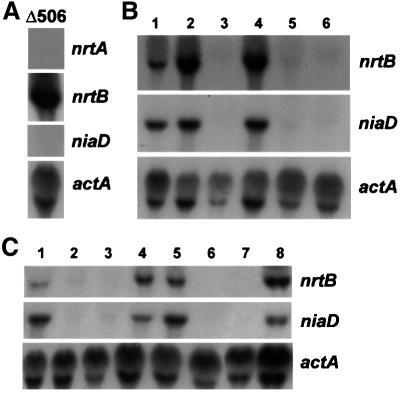

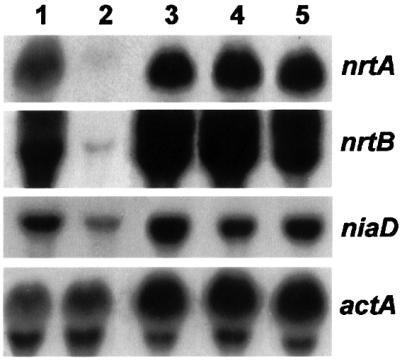

Before assaying northern filters for differential expression of nrtB and nrtA transcripts, it was important to identify DNA probes specific for each gene. Nucleotide stretches of 199 bp for nrtA and 190 bp for nrtB, which show only 41% identity and cover the region in both genes encoding the large central loop between transmembrane domains 6 and 7, were amplified and the PCR products used as gene-specific probes. The nrtB probe revealed the nrtB transcript in a mutant Δ506 (Figure 2A), which is deleted for the entire nitrate assimilation gene cluster including the nrtA gene. Conversely, the nrtA probe did not reveal the nrtB mRNA in mutant Δ506 (Figure 2A).

Fig. 2. Analysis of transcriptional regulation in cells grown under different nitrogen conditions. (A) Gene-specific probes for nrtA and nrtB. The mutant Δ506, known to have a deletion of the entire nitrate assimilation cluster including niaD, niiA and nrtA, was grown at 37°C in minimal medium for 5.5 h and transferred to medium containing 10 mM nitrate for 30 min. Total RNA was isolated, a northern blot was prepared and hybridized sequentially with the 32P-labelled, PCR-generated probes for nrtA and nrtB described in the text, followed by the 32P-labelled probes for niaD (a 2.4 kb XbaI fragment of pSTA8; Johnstone et al., 1990) and actA (a 0.85 kb KpnI–NcoI fragment of pSFR5; Fidel et al., 1988). (B) Regulation of nrtA. The wild-type strain, biA1, was grown at 25°C for a total of 13–14 h in minimal medium containing 10 mM sodium nitrite (lane 1), 10 mM sodium nitrate (lane 2), 10 mM proline plus 5 mM ammonium tartrate (lane 3), 10 mM proline plus 10 mM sodium nitrate (lane 4), 10 mM proline (lane 5) or 10 mM sodium nitrate plus 5 mM ammonium tartrate (lane 6). A northern blot of total RNA was hybridized sequentially using the probes described in (A). (C) Influence of regulatory genes. The wild type and regulatory mutants were grown at 25°C for a total of 13–14 h in minimal medium containing the following nitrogen sources: wild type (lane 1) and nirA1 loss-of-function (lane 2) with 10 mM proline and transferred to 10 mM sodium nitrate 100 min before harvesting; wild type (lane 3) and nirAc1 constitutive mutant (lane 4) with 10 mM proline; wild type (lane 5) and ΔareA a deletion (lane 6) with 5 mM ammonium tartrate and transferred to 10 mM sodium nitrate 100 min before harvesting; wild type (lane 7) and xprD1 a derepressed areA allele (lane 8) with 5 mM ammonium tartrate. A northern blot of total RNA was hybridized sequentially using the probes described in (A).

The 1.6 kb nrtB transcript was observed in total RNA from young wild-type germlings grown with nitrate, nitrite, or nitrate plus proline, but not from those grown with ammonium plus nitrate, ammonium plus proline (Figure 2B) or ammonium alone (our unpublished data). A barely detectable nrtB transcript was observed with proline (Figure 2B). In regulatory gene mutants, under inducing conditions, the nrtB transcript is absent in the nirA1 loss-of-function mutant strain (Figure 2C). Furthermore, under non-inducing conditions, the nirAc1 constitutive mutant strain produces the nrtB transcript, in contrast to the wild type. The loss-of-function ΔareA (Figure 2C) and areA217 (our unpublished data) mutants lack nrtB transcripts under inducing conditions and, conversely, the nrtB message is observed in cells of the ammonium-derepressed mutant, xprD1, grown on ammonium (Figure 2C). The niaD transcript was present in the conditions and mutants expected from previous studies, which confirmed the employment of correct growth regimes.

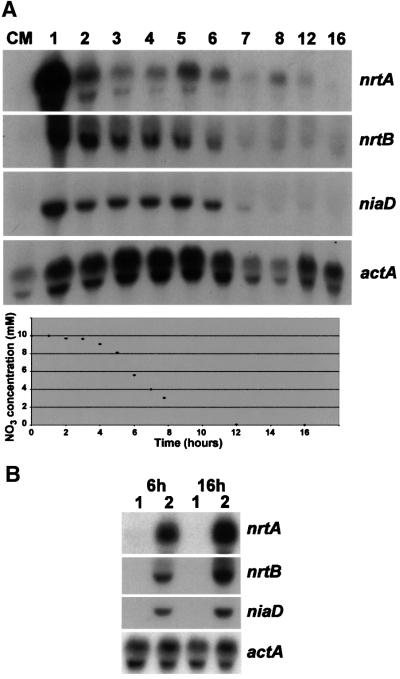

The availability of both genes provided an opportunity to investigate temporal forms of regulation, at least at the level of transcript accumulation. Cells were grown for periods of up to 16 h at 37°C with 10 mM nitrate as the nitrogen source and aliquots harvested at hourly intervals. Total RNA was prepared and hybridized with nrtA- or nrtB-specific probes. Whereas no nrtA or nrtB signals were observed in conidiospores harvested from complete solid medium (Figure 3A, lane CM), even after long autoradiographic exposure, strong signals were observed after only 1 h incubation of conidiospores in liquid minimal medium containing nitrate as the sole source of nitrogen. Much less intense but clearly visible signals were seen thereafter with decreasing intensity, until ∼6–8 h when the conidiospores germinated. Beyond this period, only weak signals could be observed. The signal intensity after 1 h seemed to be higher for nrtA than nrtB relative to the respective 2–8 h samples. The niaD signal also showed the highest intensity after 1 h, was clearly visible until 6 h, but was barely detectable thereafter. The level of nitrate remaining in the medium was measured over the growth period of 16 h at 37°C. The results presented in Figure 3A (bottom panel) show that nitrate utilization followed a sigmoidal curve, a sharp decrease in nitrate concentration being observed after 5 h when the conidiospores began to germinate. After 10 h, nitrate levels were below the limit of detection.

Fig. 3. Time course of nrtA and nrtB expression. (A) Conidiospores, filtered twice through miracloth to remove mycelial fragments, were examined for nrtA and nrtB transcripts from the inoculum grown on solid complete medium (CM) and transferred to liquid minimal media with 10 mM nitrate as the nitrogen source. Samples (100 ml) were taken at the time intervals shown above (hours) up to 16 h at 37°C. A northern blot prepared from total RNA of inoculum and each time sample was probed sequentially with the 32P-labelled probes indicated on the right and described in the legend to Figure 2A. The level of nitrate remaining in the medium at each time point is shown in the bottom panel. (B) Induction of transcripts in young germlings and older mycelial cells. Cultures were grown for a total of 6 or 16 h at 37°C with 10 mM proline (lanes 1, uninduced cells) or transferred to 10 mM nitrate 30 min prior to harvesting (lanes 2, nitrate-induced cells). A northern blot of total RNA was hybridized sequentially with the 32P-labelled probes indicated on the right and described in the legend to Figure 2A.

To circumvent the possibility that the decreasing levels of both nrtA and nrtB transcripts simply reflect the decreasing availability of nitrate, mycelium was grown for different periods on proline and transferred to nitrate for 30 min prior to harvesting. High levels of both nrtA and nrtB mRNA accumulated upon induction with nitrate after 6 and 16 h incubation (Figure 3B).

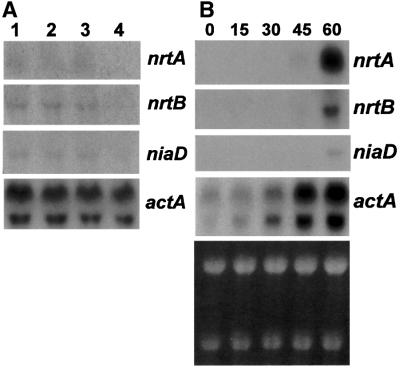

The above results suggest that the transcripts are not present in dormant conidiospores harvested from complete medium. However, it was unclear if conidiospores formed on agar minimal medium with inducing nitrogen sources, such as nitrate, contained pre-formed nrtA and nrtB transcripts. Figure 4A shows that there is a similar level of transcript, albeit barely detectable, of both genes present in conidiospores produced from mycelium grown on minimal medium with proline or nitrate as nitrogen source, and even with ammonium. As before (Figure 3A), no transcripts were detectable in RNA isolated from conidiospores harvested from complete medium. A time course experiment (Figure 4B) demonstrated that the transcripts were abundant only after 60 min growth of conidia in minimal medium containing nitrate as sole nitrogen source. Since the actin control seemed not to be constitutive in these conidiospores just exposed to medium, i.e. increased in abundance up to 60 min, the rRNA bands were included to show approximate equality of RNA loading. A similar phenomenon for A.nidulans actin expression was observed during the transition from dormancy to growth by Tazebay et al. (1997) There is an apparent discrepancy between the results in Figures 3B and 4B in terms of the time required for induction. This probably reflected a period of latency in freshly harvested conidiospores compared with germlings or mycelium grown for 6 and 16 h, respectively.

Fig. 4. Transcript levels in conidiospores. (A) The wild-type strain, biA1, was grown on agar minimal medium containing 10 mM proline (lane 1), 10 mM sodium nitrate (lane 2) or 5 mM ammonium tartrate (lane 3) as sole nitrogen source, or on agar complete medium (lane 4). Conidiospores, filtered twice through miracloth to remove mycelial fragments, were pelleted by centrifugation. A northern blot of total RNA was hybridized sequentially with the 32P-labelled probes indicated on the right and described in the legend to Figure 2A. (B) Conidiospores from agar complete medium, harvested, filtered and pelleted, were grown at 37°C in liquid minimal medium containing 10 mM sodium nitrate as sole nitrogen source for up to 60 min. Numbers at the top refer to minutes incubation following inoculation of the medium. Conidiospore samples (100 ml) following incubation were harvested by rapid filtration through a 0.45 µm cellulose acetate filter. A northern blot of total RNA was hybridized with the probes shown on the right described in the legend to Figure 2A. A photograph showing the rRNA bands (B, bottom panel) was included to demonstrate parity of RNA loading since the actA transcript itself was not constitutive.

The levels of nrtA and nrtB transcripts were assayed in loss-of-function mutations of nitrate assimilation genes: niiA17, lacking nitrite reductase, niaD24, lacking nitrate reductase and cnxH4 (Cove, 1979; and references therein), which lacks nitrate reductase due to abolition of synthesis of the molybdenum cofactor (Unkles et al., 1999). Figure 5 shows that the nrtA and nrtB mRNAs, and the niaD transcript, were much higher in the induced cells of all three mutants than in wild type.

Fig. 5. Nitrate-induced transcript levels in wild type and structural gene mutants. Strains were grown in minimal medium at 25°C for a total of 14 h, first with 10 mM proline and then transferred to minimal medium containing 10 mM sodium nitrate for 100 min prior to harvesting. Strains were cnxH4 (lane 1), wild type (lane 2), niaD24 (lane 3), niaD42 (lane 4) and niiA17 (lane 5). Total RNA in northern blots was hybridized with the probes shown to the right and described in the legend to Figure 2A.

Characterization of nitrate uptake using tracer 13NO3–

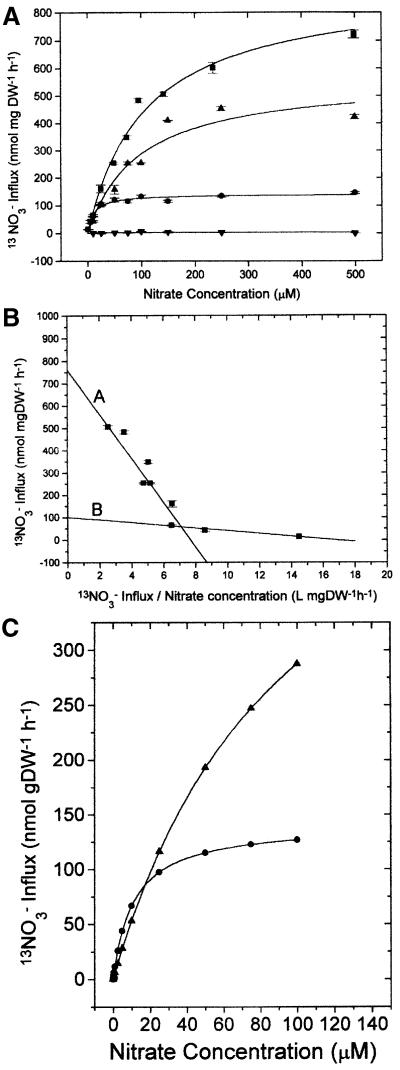

Nitrate influx was measured using the short-lived isotope 13N (t0.5 = 10 min). Figure 6A shows influx values for germlings of the wild type expressing NrtA and NrtB, the nrtA747 mutant which expresses only NrtB, the nrtB110 mutant expressing only NrtA and the nrtA747 nrtB110 double mutant expressing neither gene. 13NO3– influx usually was measured at concentrations of NO3– up to 500 µM, although measurements of 13NO3– influx at higher NO3– concentrations up to 5 mM gave no evidence for low-affinity transporters of the sort defined in higher plants (Crawford, 1995). In young cells grown for 6 h, wild-type and nrtB110 strains exhibited Km values of ∼100 µM, while the nrtA747 mutant had values of ∼10 µM. Vmax values were ∼900, 600 and 150 nmol/mg dry weight (DW)/h for wild-type, nrtB110 and nrtA747 strains, respectively (Table II), while the double mutant failed to accumulate detectable amounts of 13NO3– (Figure 6A). Therefore, the NrtA and NrtB transporters have Km values of ∼100 and 10 µM, respectively. The Vmax value for the nrtA747 mutant was ∼17% that of the wild type, a result roughly in accord with the net nitrate uptake rates recorded by Brownlee and Arst (1983). As expected from the work of Brownlee and Arst (1983), no measurable uptake of 13NO3– was observed in a nitrate reductase loss-of-function mutant, niaD171, although this experiment was performed only once and so is not included in Table II. Net nitrate uptake studies using niaD171 (our unpublished data) also confirm the finding that active nitrate reductase is required for nitrate uptake.

Fig. 6. (A) 13NO3– influx values for A.nidulans wild type (squares), mutant nrtA747, expressing only NrtB protein (circles), mutant nrtB110, expressing only NrtA protein (upright triangles), and the double mutant nrtB110 nrtA747, expressing neither protein (inverted triangles), measured at various concentrations up to 500 µM. (B) 13NO3– influx values for A.nidulans wild type, presented as a Hoffstee plot (13NO3– influx against 13NO3– influx/external NO3– concentration). The y-intercepts of regression lines generate estimates of Vmax (762 ± 138 and 100 ± 8 nmol/mg DW/h, respectively) and slopes provide Km estimates (99 ± 28 and 6 ± 0.6 µM, respectively) of the two transporters. (C) 13NO3– influx values for nrtA and nrtB mutants computed from the Km and Vmax values at low external nitrate concentration for 6 h germlings. Mutant nrtA747, expressing only NrtB protein (circles), and mutant nrtB110, expressing only NrtA protein (triangles).

Table II. Kinetic constants for 13NO3– influx by wild-type, NrtB (nrtA747 mutant) and NrtA (nrtB110 mutant) transport systems.

| Strain | Transporter |

Km |

Vmax |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 h | 16 h | 6 h | 16 h | ||

| Wild type | NrtB, NrtA | 107.5 ± 20.3 | 82.6 ± 19.6 | 896.9 ± 81.3 | 382.0 ± 32.9 |

| nrtA747 | NrtB | 11.1 ± 2.7 | 14.4 ± 10.0 | 140.9 ± 5.8 | 161.7 ± 25.7 |

| nrtB110 | NrtA | 96.3 ± 29.7 | 75.4 ± 38.0 | 564.4 ± 66.5 | 300.1 ± 71.3 |

Strains were grown for 6 or 16 h in media containing 2.5 mM urea as sole nitrogen source and exposed to 10 mM NO3– for 100 min prior to influx measurements. Km (µM) and Vmax (nmol/mg DW/h) values were determined by computer, using direct fits of data to rectangular hyperbolae.

The results of 13NO3– uptake in mature cells are also given in Table II. When mycelium was grown for a total of 16 h, there was a clear decrease in 13NO3– influx in wild-type mycelia at 16 h compared with values obtained in 6 h mycelia (Vmax values of 896 ± 81 and 382 ± 33 nmol/mg DW/h at 6 and 16 h, respectively). In contrast to earlier findings using nrtA1 (Brownlee and Arst, 1983), also a loss-of-function mutant (our unpublished data), 13NO3– influx in loss-of-function nrtA747 mycelia appeared to be relatively unchanged (Vmax values of 140.9 ± 5.8 and 161.7 ± 25.7 nmol/mg DW/h at 6 and 16 h, respectively). More importantly, the data in Table II demonstrate that the Km values for 13NO3– influx at 16 h remain the same as those evident at 6 h, namely ∼10 µM for the nrtA mutant and ∼100 µM for the wild-type strain. Thus, rather than an increase in 13NO3– influx in the nrtA mutant in older mycelia (Brownlee and Arst, 1983), the present data instead indicate a decrease in 13NO3– influx in wild-type mycelia at 16 h, bringing Vmax values closer to those of the mutant. The nrtB mutant strain also retained a Km value close to that at 6 h and also revealed a reduction of Vmax from 564 ± 67 to 300 ± 71 nmol/mg DW/h.

Clearly, in young (6 h) wild-type cells, activity of the NrtA transporter is a major component of nitrate uptake since influx in the nrtA747 mutant was substantially reduced, and there appeared to be a lack of compensation by the NrtB transporter. In order to investigate the participation (if any) of the NrtB transporter in wild-type kinetics, Hoffstee plots were generated and examined for bimodality. Figure 6B presents a Hoffstee plot of the 13NO3– influx data for 6 h wild-type mycelium after 100 min exposure to nitrate. Bimodality was always observed in experiments that included influx measurements at lower concentrations of nitrate. The slopes of the regression lines in this Hoffstee plot (equivalent to Km values) revealed contributions of a transporter with a Km value of ∼100 µM and another with a Km value of ∼10 µM, as was observed in the mutants. Vmax values (y-intercepts) also corresponded closely (762 and 100 nmol/mg DW/h, respectively) to values obtained in the mutants where only one transporter operated.

Induction of nitrate assimilation genes

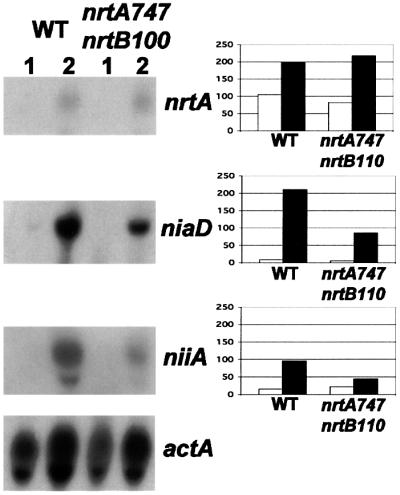

The question of whether nitrate assimilation systems are still induced in a strain that lacks capacity to transport nitrate was addressed by comparing young (6 h) double mutant nrtA747 nrtB110 with wild-type cells. The northern blot presented in Figure 7 clearly shows that all three genes (niaD, niiA and nrtA) were induced by the addition of nitrate to the growth medium of both the wild type and the double mutant (nrtB was not tested, since the double mutant has a disrupted nrtB gene). Quantitative measurements indicated that the double mutant had reduced levels of both niaD and niiA transcripts relative to the wild type (41 and 45%, respectively). However, the abundance of nrtA transcript was roughly the same in the double mutant as in the wild type. The enzyme activity was assayed in the case of nitrate reductase and this was in approximate accord with transcript levels. This induction of the nitrate assimilation pathway is not due to contaminating nitrite in the nitrate solution, since no induction of nitrate reductase activity was obtained following treatment with a final concentration of 20 nM nitrite (our unpublished data). Our stock sodium nitrate solution used for induction would have provided 10–15 nM nitrite in each flask.

Fig. 7. Induction of nrtA, niaD and niiA transcripts in wild type (WT) and the double mutant nrtA747 nrtB110. Total RNA was isolated from mycelium grown at 37°C in minimal medium for 6 h with 10 mM proline as sole nitrogen source (lanes 1) or for 5.5 h with 10 mM proline and 10 mM sodium nitrate added for 30 min prior to harvesting (lanes 2). A northern blot was hybridized sequentially with the probes shown to the right and detailed in the legend to Figure 2A. The niiA probe was a 1.1.kb EcoRI fragment of pSTA3 (Johnstone et al., 1990). To the right of the respective probes are histograms showing the quantitative data obtained from the northern blot. The open bar represents values obtained for lanes 1 and the closed bar values for lanes 2. The scale shows arbitrary units determined by the actual signal values for each probe as a percentage of those signal values for the internal control actA probe in the same lane.

Discussion

The data establish that A.nidulans possesses only two functional NO3– transporters, nrtA and nrtB, in contrast to the 11 NO3– transporter genes in A.thaliana (Arabidopsis genomic sequence http://www.arabidopsis.org/home.html). nrtA and nrtB may appear to be redundant genes since their cognate proteins (i) are clearly homologues with only short regions of amino acid differences and (ii) are involved in the same function, i.e. high-affinity nitrate transport. Moreover, deletion mutants in either gene have no detectable phenotype, vis-à-vis growth on 1–10 mM nitrate, and both genes are regulated identically under an extensive range of conditions and in different genetic backgrounds. Nevertheless, the proteins have different Km and Vmax values for nitrate. We hypothesize that at high ambient nitrate, the NrtA transporter makes the major contribution to influx, but when ambient nitrate declines to <10 µM, as shown in Figure 6C, the contribution to influx of the NrtB transporter is actually double that of the NrtA counterpart. In environments with rapidly fluctuating nitrate concentrations, therefore, a mutant in either gene would be disadvantaged.

The kinetic characterization of individual nitrate transporters has been hampered by the lack of a convenient tracer to measure nitrate influx rather than net 14NO3 uptake, the balance between influx and efflux. Using measurements of net nitrate uptake by wild-type A.nidulans, Brownlee and Arst (1983) recognized that the kinetics of uptake were more complex than could be explained by a single nitrate transporter, but were unable to resolve the individual transporter contributions contained in their data. In Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Galvan et al. (1996) used net nitrate uptake measurements to document Km values of 1.6 and 11 µM, respectively, for strains expressing Nrt2;1 and Nrt2;2. In higher plant systems, e.g. in barley roots, even when 13NO3– was employed to characterize influx (Siddiqi et al., 1989), the reported kinetics might result from the combined activities of several high-affinity transporters. In A.thaliana, Filleur et al. (2001) have measured the kinetics of 15NO3– influx in a T-DNA insertional mutant; however, this strain was compromised in both Nrt2.1 and Nrt2.2 genes. Thus, up to now, only with the C.reinhardtii data (and with the caveat that net uptake was determined) has it been possible to characterize individual nitrate transporters in planta. Alternatively, several studies have employed Xenopus oocytes to attempt electrical characterization of the A.nidulans crnA gene and the C.reinhardtii Nar2 and Nrt2;1 genes (Zhou et al., 2000a,b). These and other studies employing heterologous expression systems may provide valuable qualitative information, but, given that these proteins are expressed in foreign membrane systems, quantitative data obtained by such methods should be interpreted with some caution.

It is instructive to note that in both C.reinhardtii and A.nidulans the two transporters show a 10-fold difference in Km values, allowing a greatly expanded range of nitrate acquisition. It is also noteworthy that in wild-type mycelium, expressing two transporter systems with markedly different Km values, the kinetics conform to a simple (Michaelis–Menten) hyperbola. Thus, conformity to Michaelis–Menten kinetics cannot be taken as evidence for the exclusive operation of but a single transport/enzyme activity.

Whereas nrtA and nrtB single mutants grow on nitrate, the nrtA nrtB double mutant is unable to grow even if the nitrate concentration is increased to 200 mM. The inability to grow on nitrate is similar to niaD loss-of-function mutants (lacking nitrate reductase). The failure to detect further homologues from the A.nidulans genome sequencing project (V.Gavrias, personal communication) supports our conclusion that NrtA and NrtB are the only nitrate transporters in this species. In young cells, as judged by Vmax values, a loss-of-function nrtA mutant has ∼17% of the nitrate uptake rate of the wild type, which is presumably due to NrtB activity. NrtA involvement is, therefore, required in order to achieve wild-type levels of uptake. In contrast, the nrtB mutant displays a close to wild-type uptake rate in young cells, suggesting that a functional NrtA can almost completely compensate for the loss of NrtB activity. In mature mycelial cells, the maximum rate of nitrate uptake in the wild type falls relative to young cells to a level only around twice that of a nrtA mutant. The fact that uptake rates in the wild-type and nrtB110 strains are similar, and in nrtA747 are only around half the wild-type value, indicates that in older cells NrtB can compensate more effectively for the lack of functional NrtA. Whether the reduction in Vmax in the wild-type and nrtB110 strains is due to an intrinsic change in the NrtA protein or to a reduction in NrtA protein per unit biomass is unclear. However, the reduction may indicate a degree of developmental control at the protein level. Furthermore, in both net nitrate (our unpublished data) and [13N]nitrate experiments, the wild-type uptake rate is less than the sum of the rates observed for nrtA747 and nrtB110. This suggests that there may be some form of cross-regulation in older wild-type cells, such as has been described for mammalian Rh proteins (Ridgewell et al., 1994) and yeast ammonium transporters (Marini et al., 2000). The reduction in nitrate uptake rate between young and older cells is in contrast to the results of Brownlee and Arst (1983) who found that the wild-type rate was maintained between young and old cells, and that the value for the nrtA mutant increased to a level similar to wild type in mature mycelium. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear but, in this study, a reduction in uptake rate of wild type in the longer incubation period was observed reproducibly in both net nitrate (our unpublished data) and [13N]nitrate experiments. A similar pattern has also been observed repeatedly in higher plant root studies (Siddiqi et al., 1989; Zhuo et al., 1999).

Although both nrtA and nrtB mutants grow as wild type on nitrate as sole nitrogen source, unlike nrtA, nrtB mutants are able to grow normally on nitrate in the presence of caesium. Previously, it was postulated that caesium inhibited the growth of the nrtA1 mutant on nitrate because it inhibited the other, at that time uncharacterized, nitrate uptake system (Unkles et al., 1991). This suggestion, however, appears to be incorrect since net nitrate uptake by the wild type, nrtA747 mutant or nrtB110 mutant is unaffected in the presence of caesium (our unpublished data). Secondly, the nrtB mutant differs from that of nrtA in that nrtB is not resistant to chlorate toxicity at the standard concentrations used to monitor chlorate resistance. This suggests that while NrtA actively takes up chlorate, resulting in sensitivity to chlorate toxicity in the wild-type strain, NrtB does not. Resistance to toxicity is therefore the result of mutations within nrtA. The nrtB mutant strain remains sensitive since it still possesses a wild-type NrtA. In this regard, recent characterization of nrtA expressed in Xenopus oocytes has cast doubt on toxicity being due to chlorate. Instead, it has been suggested that contaminating chlorite is the agent responsible for toxicity since it appears in this heterologous expression system that nrtA transports chlorite but not chlorate (Zhou et al., 2000b). However, two factors require consideration in interpretation of these results. First, commercially available chlorite itself contains a high proportion (∼20%) of uncharacterized contaminants, which could elicit a response in electrical conductivity experiments. Secondly, preliminary growth tests of nrtA and nrtB mutants on medium containing chlorite (our unpublished data) show that the mutants do not conform to the recognized growth phenotype obtained with chlorate, and so the results of Zhou et al. (2000b) remain enigmatic. Finally, with regard to the phenotypes of nrtA and nrtB mutants, the growth of the double mutant is similar to wild type on nitrite (in the presence or absence of caesium) as the sole source of nitrogen, suggesting that neither NrtB nor NrtA is required for nitrite transport. It was reported previously that caesium reduced growth of nrtA1 when nitrite was the sole nitrogen source (Unkles et al., 1991). However, strain nrtA747 and other newly isolated nrtA mutants (our unpublished data) grow normally on nitrite plus caesium, suggesting that the original phenotype may have been caused by a secondary mutation.

The regulation of nrtB appears to be identical to that of nrtA as judged by the abundance of transcript levels in northern blot experiments. Clearly, nrtB is under the control of the nitrate assimilation pathway-specific control gene for induction, nirA, and areA, the global control gene for nitrogen metabolite repression. In nitrate assimilation structural gene mutants, both nrtA and nrtB transcripts are elevated upon nitrate induction, probably reflecting the fact that these mutants are unable to utilize nitrate. Hence there is no reduction of the inducer, nitrate, or production of repressor(s), ammonium or glutamine. The question was addressed as to whether the two nitrate transporter genes might be expressed differentially in young germinating conidiospores and older mycelial cells. Cells grown on nitrate as the sole nitrogen source for up to 16 h show maximum levels of both nrtA and nrtB transcripts (and also the niaD transcript) after only 1 h incubation (in liquid medium), falling significantly thereafter to barely detectable levels at 7 h. Unlike the transcript of the A.nidulans proline transporter, prnB, which has been shown to accumulate in conidiospores even in the absence of proline induction (Tazebay et al., 1997), the rapid increase in nrtA and nrtB transcript abundance in conidiospores requires induction by nitrate (our unpublished data). The fall in transcript abundance occurs after 1 h despite a high concentration of nitrate remaining in the external medium. This suggests that there may be some repression of transcription arising from increasing intracellular pools of ammonium or glutamine, which are known to be the co-repressors mediating AreA function (Morozov et al., 2000; and references therein). Reduction of transcripts to extremely low levels after 8 h additionally may be the result of consumption of nitrate with the resultant loss of induction. However, our northern blot analysis suggested that there was no differential expression of the nrtA and nrtB mRNAs, at least at the level of RNA accumulation. This was confirmed by the demonstration that both of these transcripts can be highly expressed in young cells as well as in mature mycelium after a short induction period by nitrate. Therefore, it would seem that transcription of the two genes is not under the influence of developmental control, rather being subject to control by metabolic signals of nitrate induction and ammonium (nitrogen metabolite) repression only.

A surprising result obtained in the course of this study was the demonstration of inducibility of nitrate assimilation genes in the nrtA747 nrtB110 double mutant, a mutant devoid of measureable nitrate transport. That transcription of the nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase genes is induced to 40–45% of the wild-type level in the absence of measurable nitrate transport, with the level of the nrtA gene transcript being similar to that in the wild type, leads us to the conclusion that nitrate may not need to enter the cell to induce the pathway. It is possible that very low levels of nitrate (sufficient for gene induction but not for mycelial growth) enter via another transport system. However, given that the double mutant (i) fails to grow on 200 mM nitrate whereas the wild type exhibits tangible growth at 1 mM nitrate, and (ii) we failed to detect 13NO3– influx in the double mutant despite the great sensitivity of this methodology, a hypothesis involving external nitrate sensing remains a distinct possibility.

Materials and methods

Aspergillus nidulans strains and media

The standard wild-type (with regard to nitrogen regulation) strain used in this study was biA1. Nitrate assimilation-defective mutants (niaD171, niaD24, niiA17 and cnxH4) are discussed by Cove (1979; and references therein). Strain Δ506 is a deletion in the nitrate assimilation pathway and lacks niaD, niiA and nrtA genes (Tomsett and Cove, 1979). Strain ΔareA is deleted in a substantial portion of the coding region (M.A.Davis, unpublished data) and nrtA747 is a single base deletion in transmembrane domain 2 which places a stop codon immediately distal to the deletion (our unpublished data). Routine Aspergillus growth media and handling techniques were as described before (Clutterbuck, 1974). Shake flask cultures for nitrate reductase and nitrate uptake assays as well as for northern blots were grown in liquid minimal medium (Cove, 1966) containing the sole nitrogen sources as stated in the text or figure legends. Harvesting of mycelium was by filtration through 0.45 µm cellulose actetate filters (conidiospores) or miracloth (mycelia) (CN Biosciences, Nottingham, UK); samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C.

Genetic transformation

This was carried out as described before (Riach and Kinghorn, 1995; and references therein) using initially the riboflavin auxotrophic mutant yA2 pabaA1 prnΔORF riboB2 (strain number CS2290) and, later, mutant strain yA2 riboB2 nrtA747 (strain JK2001).

Escherichia coli strains, plasmids and media

Standard procedures were used for propagation of cosmids and bacteriophage, as well as for subcloning and propagation of plasmids in Escherichia coli strain DH5α.

Molecular methods

DNA was isolated using a Nucleon BACC2 Kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK) and RNA using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). The conditions used during Southern and northern blot analysis were as described previously (Unkles et al., 1999). The nucleotide sequence of the A.nidulans wild-type nrtB gene was determined in both strands using the Sequenase version 2 DNA sequencing kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and by automated sequence analysis as described before (Unkles et al., 1999). Hybridization signals in northern blots were quantified using an Instant Imager (Packard, Meriden, USA).

Isolation of the nrtB gene and creation of a gene disruption

An A.nidulans cosmid library was generated using a pWEB Cosmid Cloning Kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI) and hybridized under conditions of low stringency with a probe derived by PCR amplification and encompassing the nrtA coding region. Twelve positively hybridizing clones were obtained and these subsequently were hybridized with a probe derived from the niiA gene for nitrite reductase, which is contiguous with nrtA in the nitrate assimilation gene cluster on chromosome 8 (Johnstone et al., 1990). One clone failed to hybridize to niiA, i.e. was not contiguous with niiA, and was characterized further by Southern blotting with the nrtA gene probe, identifying a 6 kb HindIII fragment convenient for subcloning into pUC19 to give pMON13. A 2.5 kb blunt-ended fragment containing the wild-type riboB gene (Oakley et al., 1987) was used to replace a 780 bp NcoI fragment of the nrtB coding region (also blunt ended) (nucleotides 441–1220 in Figure 1A) to give pMON15. This was transformed into a double mutant strain riboB2 nrtA747 (strain JK2001). Several riboflavin prototrophic transformants failed to grow on 10 mM nitrate. Southern analysis showed that the nrtB gene had been disrupted in all nitrate non-utilizing transformants examined. One of these transformants, T110, containing the disrupted nrtB mutation, was designated allele 110. To obtain the single nrtB110 mutant, transformant strain T110 was outcrossed to the yA2 pabaA2 argB2 strain. Four progeny showing the wild-type phenotype were examined by Southern blot. One of these four, progeny 41, possessed the disrupted nrtB bands. Finally, progeny 41 (nrtB110) was crossed to the single mutant strain nrtA747 and progeny unable to grow on nitrate were recovered, thus confirming that progeny strain 41 did indeed harbour the nrtB110 mutation (our unpublished data).

Nitrate reductase assays

The growth of conidiospores, young germlings and mycelium was at 37°C with orbital shaking at 250 r.p.m.. Nitrate reductase assays were perfomed at 25°C according to the method of Cove (1966).

Uptake assays using the tracer 13NO3–

The generation and purification of 13NO3– was undertaken at the University of British Columbia TRIUMF cyclotron as detailed in Kronzucker et al. (1995). Approximately 5 × 109 viable conidiospores were inoculated into two 400 ml amounts of minimal medium containing appropriate vitamin supplements and 2.5 mM urea as nitrogen source, and incubated at 37°C with orbital shaking at 250 r.p.m. After induction with 5 mM sodium nitrate for 100 min, strains were filter-harvested through miracloth, thoroughly washed with warm nitrate-free medium and held in minimal medium containing vitamin supplements and 10 µM sodium nitrate at 37°C. Three 30 ml samples were filtered and dried to estimate dry weights and 50 ml samples aliquoted for uptake of 13NO3– at 37°C with reciprocal shaking at 100 r.p.m. After 2 or 10 min incubation, 5 × 5 ml aliquots were filtered rapidly through 25 mm glass fibre filters, type GF/C (Whatman, Maidstone, UK). These were washed with 200 ml of non-labelled medium at 37°C containing 200 µM sodium nitrate to eliminate 13NO3– adhering to cell wall material. Samples taken after 5 s incubations were used to confirm that this washing protocol was effective. Filters were counted as described in Kronzucker et al. (1995). Michaelis–Menten curves were generated by non-linear regression using Microcal Origin software.

Growth conditions for transcript analysis

Incubations were carried out at 25°C for 13–14 h with orbital shaking at 250 r.p.m., conditions that give young germlings at a growth state similar to that achieved by incubation at 37°C for 6–7 h. The standard inoculum was conidiospores scraped from half of a fully covered 9 cm Petri dish containing Aspergillus complete agar medium and suspended by vigorous vortexing in sterile 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride, 0.1% (w/v) Tween-80. This was inoculated into 200 ml of minimal medium containing appropriate vitamin supplements and the nitrogen sources indicated. Exceptions to this growth regime were experiments in which samples were taken at timed intervals during incubation of conidiospores or mycelium. Conidiospores from 11 and four Petri dishes for a 16 h and a 60 min time course, respectively, suspended in sterile 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride, 0.1% (w/v) Tween-80, were filtered twice through miracloth to remove mycelial fragments and pelleted by centrifugation. The conidiospores were inoculated into 1600 or 500 ml for the 16 h and 60 min time course, respectively. In these experiments, and those for comparison of induction of nitrate assimilation genes in the wild type and nrtA nrtB double mutant, strains were grown at 37°C with orbital shaking at 250 r.p.m.. Nitrate concentrations in the growth medium were estimated using the procedure of Cataldo et al. (1975). The nitrite concentration of the 1 M stock solution of sodium nitrate was determined colorimetrically as described by Cove (1966).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We appreciate strains sent to us by a number of colleagues. S.E.U. and A.D.M.G. gratefully acknowledge the Australian Research Council and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, respectively, for financial support. A.D.M.G. thanks the University of British Columbia Tri University Meson Facility for provision of 13N. J.R.K. thanks The Royal Society (London) for travel funds to Canada and Australia.

References

- Amarasinghe B.H.R.R., Debruxelles,G.L., Braddon,M., Onyeocha,I., Forde,B.G. and Udvardi,M.K. (1998) Regulation of GMNRT2 expression and nitrate transport activity in soybean (Glycine max). Planta, 206, 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield J.F. (1997) Genetic redundancy. Adv. Genet., 36, 137–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee A.G. and Arst,H.N.,Jr (1983) Nitrate uptake in Aspergillus nidulans and involvement of the third gene of the nitrate assimilation gene cluster. J. Bacteriol., 155, 1138–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan K.M., Grossniklaus,U. and Gehring,W.J. (1994) Functional redundancy: the respective roles of the two sloppy paired genes in Drosophila segmentation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 6324–6328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo D.A., Harron,M., Schrader,L.E. and Youngs,V.L. (1975) Rapid colorimetric determination of nitrate in plant tissue by nitration of salicylic acid. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal., 6, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Christophides G.K., Livadaras,I., Savakis,C. and Komitopoulou,K. (2000) Two medfly promoters that have originated by recent gene duplication drive distinct sex, tissue and temporal expression patterns. Genetics, 156, 173–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutterbuck A.J. (1974) Aspergillus nidulans genetics. In King,R.C. (ed.), Handbook of Genetics. Vol. 1. Plenum Press, New York, NY, pp. 447–510.

- Cove D.J. (1966) The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 113, 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cove D.J. (1976) Chlorate toxicity in Aspergillus nidulans: the selection and characterisation of chlorate resistant mutants. Heredity, 36, 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cove D.J. (1979) Genetic studies of nitrate assimilation in Aspergillus nidulans. Biol. Rev., 54, 291–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford N.M. (1995) Nitrate: nutrient and signal for plant growth. Plant Cell, 7, 859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford N.M and Glass,A.D.M. (1998) Molecular and physiological aspects of nitrate uptake in plants. Plant Sci., 3, 389–385. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel-Vedele F., Filleur,S. and Caboche,M. (1998) Nitrate transport: a key step in nitrate assimilation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 1, 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidel S., Doonan,J.H. and Morris,N.R. (1988) Aspergillus nidulans contains a single actin gene which has unique intron locations and encodes γ-actin. Gene, 70, 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filleur S. and Daniel-Vedele F. (1999) Expression analysis of a high-affinity nitrate transporter isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana by differential display. Planta, 207, 461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filleur S., Dorbe,M.F., Cerezo,M., Orsel,M., Granier,F., Gojon,A. and Daniel-Vedele,F. (2001) An Arabidopsis T-DNA mutant affected in Nrt2 genes is impaired in nitrate uptake. FEBS Lett., 489, 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde B.G. (2000) Nitrate transporters in plants: structure, function and regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1465, 219–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A., Quesada,A. and Fernandez,E. (1996) Nitrate and nitrite are transported by different specific transport systems and by a bispecific transporter in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 2088–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone I.L. et al. (1990) Isolation and characterisation of the crnA–niiA–niaD gene cluster for nitrate assimilation in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene, 90, 181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronzucker H.J., Siddiqi,M.Y. and Glass,A.D.M. (1995) Compart mentation and flux characteristics of ammonium in spruce. Planta, 196, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- Marini A.M., Springael,J.Y., Frommer,W.B. and Andre,B. (2000) Cross-talk between ammonium transporters in yeast and interference by the soybean SAT1 protein. Mol. Microbiol., 35, 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov I.Y., Martinez,M.G., Jones,M.G. and Caddick,M.X. (2000) A defined sequence within the 3′ UTR of the areA transcript is sufficient to mediate nitrogen metabolite signalling via accelerated deadenyl ation. Mol. Microbiol., 37, 1248–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak M.A., Boerlijst,M.C., Cooke,J. and Maynard Smith,J. (1997) Evolution of genetic redundancy. Nature, 388, 167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley C.E., Weil,C.F., Kretz,P.L. and Oakley,B.R. (1987) Cloning of the riboB locus of Aspergillus nidulans. Gene, 53, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson K.D., Cleaver,O., Gerber,W.V., White,F.G. and Krieg,P.A. (2000) Distinct expression patterns for two Xenopus Bar homeobox genes. Dev. Genes Evol., 210, 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez M.D., González,C., Ávila,J., Brito,N. and Siverio,J.M. (1997) The YNT1 gene encoding the nitrate transporter in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha is clustered with genes YNI1 and YNR1 encoding nitrite reductase and nitrate reductase and its disruption causes inability to grow in nitrate. Biochem. J., 321, 397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada A, Galvan,A. and Fernandez,E. (1994) Identification of nitrate transporter genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J., 5, 407–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada A., Krapp,A., Trueman,L.J., Daniel-Vedele,F., Fernandez,E., Forde,B.G. and Caboche,M. (1997) PCR-identification of a Nicotiana plumbaginifolia cDNA homologous to the high-affinity nitrate transporters of the crnA family. Plant Mol. Biol., 34, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riach M. and Kinghorn,J.R. (1995) Genetic transformation in filamentous fungi. In Bos,C. (ed.), Fungal Genetics. Wiley Press, London, UK, pp. 209–234.

- Ridgwell K., Eyers,S.A., Mawby,W.J., Anstee,D.J. and Tanner,M.J. (1994) Studies on the glycoprotein associated with Rh (rhesus) blood group antigen expression in the human red blood cell membrane. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 6410–6416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheible W.R., Gonzales-Fontes,A., Laurer,M., Muller-Rober,B., Caboche,M. and Stitt,M. (1997) Nitrate acts as a signal to induce organic acid metabolism and repress starch metabolism in tobacco. Plant Cell, 9, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi M.Y., Glass,A.D.M., Ruth,T.J. and Fernando,M. (1989) Studies of the regulation of nitrate influx by barley seedlings using 13NO3–. Plant Physiol., 90, 806–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J., Muro-Pastor,M.I. and Scazzocchio,C. (1998) The regulator of nitrate assimilation in ascomycetes is a dimer which binds a nonrepeated, asymmetrical sequence. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 1339–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazebay U.H., Sophianopoulou,V., Scazzocchio,C. and Diallinas,G. (1997) The gene encoding the major proline transporter of Aspergillus nidulans is upregulated during conidiophore germination and in response to proline induction and amino acid starvation. Mol. Microbiol., 24, 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomsett A.B. and Cove,D.J. (1979) Deletion mapping of the niiA niaD gene region of Aspergillus nidulans.Genet. Res., 34, 19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueman L.J., Richardson,A. and Forde,B.G. (1996) Molecular cloning of higher plant homologues of the high-affinity nitrate transporters of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Aspergillus nidulans. Gene, 175, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unkles S.E., Hawker,K., Grieve,C., Campbell,E.I. and. Kinghorn,J.R. (1991) crnA encodes a nitrate transporter in Aspergillus nidulans. [correction appears in Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA (1995) 92, 3076] Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 204–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unkles S.E., Heck,I.S., Appleyard,M.V.C.L. and Kinghorn,J.R. (1999) Eukaryotic molybdopterin synthase. Biochemical and molecular studies of Aspergillus nidulans cnxG and cnxH mutants. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 19286–19293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidmar J.J., Zhuo,D., Siddiqi,M.Y., Schjoerring,J.K., Touraine,B. and Glass,A.D.M. (2000) Regulation of high-affinity nitrate transporter genes and high-affinity nitrate influx by nitrogen pools in roots of barley. Plant Physiol., 123, 307–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J.L. and Kinghorn,J.R. (1989) Molecular and Genetic Aspects of Nitrate Assimilation. Oxford Scientific Publications, Oxford, UK.

- Zhang H. and Forde,B.G. (1998) An Arabidopsis MADS box gene that controls nutrient-induced changes in root architecture. Science, 279, 407–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo D., Okamoto,M., Vidmar,J.J. and Glass,A.D.M. (1999) Regulation of a putative high-affinity nitrate transporter (Nrt2;1At) in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J., 17, 563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.J., Fernandez,E., Galvan,A. and Miller,A.J. (2000a) A high affinity nitrate transport system from Chlamydomonas requires two gene products. FEBS Lett., 466, 225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.J., Trueman,L.J., Boorer,K.J., Theodoulou,F.L., Forde,B.G. and Miller,A.J. (2000b) A high affinity fungal nitrate carrier with two transport mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 39894–39899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]