Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12) is a zinc-dependent enzyme involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and inflammatory processes. In this study, a ligand-and structure-based design approaches including pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking were employed to identify potent MMP-12 inhibitors. Indole-3-acetic acid derivatives were prioritized based on their fit to a pharmacophore model and strong predicted interactions within the MMP-12 catalytic site. Selected compounds were synthesized and evaluated using a colorimetric enzyme inhibition assay. Docking studies revealed favorable binding energies and key interactions with active-site residues such as HIS-218, PHE-237, GLU-219, and LEU-181. Enzyme inhibition assays validated the activity of the indole-3-acetic acid scaffold, with four leading candidates (C23–C26) demonstrating over 94% inhibition of MMP-12. The integration of in silico predictions with experimental testing guided the identification of indole-3-acetic acid as a promising scaffold, underscoring the utility of this design approach for scaffold prioritization. These findings establish indole-3-acetic acid as a promising scaffold for further development of MMP-12 inhibitors and provide a foundation for future biological evaluation.

1. Introduction

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) constitute a significant family of zinc (Zn2+)-dependent proteolytic enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) components. , MMPs are implicated in pathological conditions where excessive ECM degradation disrupts normal tissue architecture. − Among these enzymes, matrix metalloproteinases-12 (MMP-12) is notable for its broad substrate specificity, including elastin, fibronectin, and type IV collagen, and its critical role in tissue remodeling, inflammation, and cancer progression. − Also, by breaking down physical barriers within the cancer microenvironment, MMP-12 facilitates cancer cell invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis. ,

Protein mutations significantly contribute to the development and progression of cancer by altering the structure, function, or regulation of essential cellular proteins. These mutations can activate oncogenes, inactivate tumor suppressor genes, or disrupt the signaling pathways that control cell growth, apoptosis, and differentiation. , In the context of drug resistance, mutations can change the binding sites of therapeutic targets, decrease drug affinity, or activate compensatory pathways that circumvent the effects of the medication. , For instance, structural changes in a mutated protein may hinder the binding of inhibitors or enhance enzymatic activity, ultimately reducing the effectiveness of treatments. Understanding these mutations and their impacts is crucial for developing targeted therapies and designing inhibitors that are effective against both wild-type and mutant forms of the protein.

The catalytic domain of MMP-12 embeds the conserved HEXXHXXGXXH Zn2+-binding motif, which is a characteristic of MMP family. , Therefore, developing potential MMP-12 inhibitors presents a challenge due to the high sequence and structural similarity among MMP family members, particularly within the catalytic domain. , Understanding the detailed structure of MMP-12 active site is crucial for the rational design of potential inhibitors that can modulate its function in pathological conditions. Computational drug design approaches, such as pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking, have become essential tools to identify potential inhibitors.

Pharmacophore modeling identifies the binding features that are necessary for selective binding, thus guiding virtual screening process to identify potential selective inhibitors of MMP-12. However, molecular docking helps in predicting the binding conformation and affinity of candidate inhibitors within MMP-12 active site. ,

Both the wild-type and mutant crystal structures of MMP-12 were utilized in this study to investigate how structural variations might influence inhibitor binding. The mutant structure (PDB ID: 6RLY) features a single amino acid substitution at position 67, where aspartic acid is replaced by phenylalanine (D67F). This substitution was made to enhance crystallization and is not associated with mutations related to cancer or drug resistance. While MMP-12 is not commonly mutated in cancer, its overexpression and proteolytic activity are strongly correlated with tumor progression and metastasis. By comparing the mutant structure to the wild-type enzyme (PDB ID: 2WO8), we aimed to evaluate how even nonpathological structural changes could impact the binding of potential anticancer agents.

Both processes enable the prioritization of molecules for synthesis and streamlining the drug discovery pipeline. In this study, we employed both ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and structure-based molecular docking approaches to identify promising scaffolds. Selected hits were then synthesized and characterized using 1H-and 13C NMR and HRMS. The in vitro biological activity was evaluated against pure MMP-12 enzyme. This integrated approach, from computational prediction to experimental validation, provides a robust framework for discovering novel MMP-12 inhibitors with potential applications in lung cancer therapy.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. Acylation Reaction

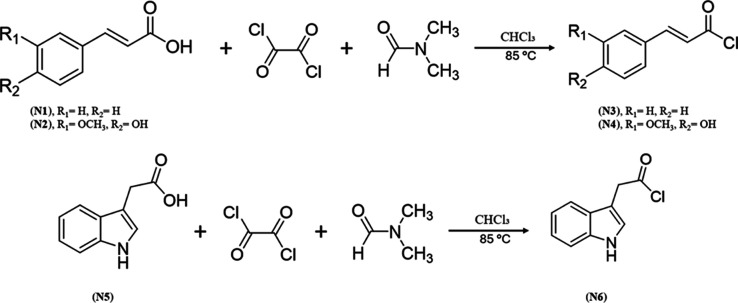

The synthesis procedures involve acylation followed by amidation reactions, depending on the targeted scaffold. The first step of acylation reaction was reaction of the corresponding carboxylic acids with oxalyl chloride in the presence of catalytic amount of dimethylformamide (DMF). The acylation of cinnamic acid (N1), Ferulic acid (N2) and indole-3-acetic acid (N5) was conducted as detailed in Scheme .

1. Synthesis of Compounds N3 to N4 and N6 .

Reagents and conditions: Oxalyl chloride, DMF, ice bath, then heated in an oil bath at 85 °C for 24 h.

The acylation of carboxylic acids using oxalyl chloride and dimethylformamide (DMF) involves a two-step activation mechanism. In the first step, DMF acts as a catalytic nucleophile, reacting with oxalyl chloride to produce a Vilsmeier-type intermediate known as chloromethylideneiminium chloride. This intermediate then reacts with the carboxylic acid, resulting in the formation of an acyl chloride through a nucleophilic substitution reaction. In this process, the hydroxyl group of the carboxylic acid is replaced by a chloride ion. Additionally, carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2) are released as byproducts. The resulting acyl chloride is relatively reactive and can be employed to undergo into further acylation reactions, such as the formation of amides or esters.

2.1.2. Amidation Reaction

The second step of the synthesis was amidation reaction. The amidation of the acyl compounds N4 and N5 was conducted utilizing an amine derivative listed in Table (Scheme ).

1. Chemical Structures of Amines Derivatives (R–NH2) (a–r).

2. Synthesis of C7–C10 .

a Reagents and conditions: CHCl3, 90°C, pyridine, 24 h.

The amidation of compound N7 utilizing an amine derivative listed in Table was performed as outlined in Scheme .

3. Synthesis of C11–C17 .

a Reagents and conditions: CHCl3, 90 °C, pyridine, 24 h.

The amidation of compound N6 utilizing an amine derivative listed in Table was performed as outlined in Scheme .

4. Synthesis of C18–C27 .

a Reagents and conditions: CHCl3, 90 °C, pyridine, 24 h.

The second step involves amide bond formation via nucleophilic acyl substitution between an amine and an acyl chloride. The amine attacks the carbonyl carbon, forming a tetrahedral intermediate that collapses to release chloride and yield the amide product. A base such as pyridine is used to neutralize the HCl byproduct, preventing side reactions and preserving the nucleophilicity of the amine. This method offers a straightforward and efficient approach to amide synthesis under mild conditions.

2.1.3. Discussion of the Characterization Data for the Synthesized Compounds

The synthesized compounds were characterized using 1H NMR and 13C NMR along with high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to identify comprehensive insights into the molecular structure. The NMR shifts confirmed the expected chemical identity and connectivity, while, the HRMS verified the molecular weight and consequently provided further confirmation for the identity of the verified compounds. The collected data aligned well with the proposed structures, confirming both the successful formation and purity of the synthesized compounds.

The 1H NMR spectrum indicates the presence of an amide NH proton at δ (10.15–10.91) (singlet, 1H), which confirms the existence of the amide group. Aromatic protons are observed in the δ 7.0–7.9 ppm range, displaying distinct splitting patterns that indicate a well-defined aromatic system. Additionally, the downfield carbonyl peak in the 13C NMR at δ ∼163.7 ppm confirms the presence of the amide carbonyl, while the ketone carbonyl at δ ∼194.2 ppm further supports the anticipated structure. These consistent chemical shifts and patterns verify the correct formation of the product. The mass spectrometry (MS) analysis confirmed the product’s synthesis by displaying molecular ion peaks that correspond to the expected molecular weights, thereby verifying their identity. Due to the solubility problem, representative HRMS spectra were recorded for some prepared compounds.

2.2. Computational Studies

2.2.1. Pharmacophore Modeling

The pharmacophore model was developed from selective MMP-12 inhibitors using MOE software. Compounds with 5-fold selectivity against MMP-12 compared to other MMPs were included (Table ). The selective inhibitors were built in MOE, using the cocrystallized ligand (ID: 077) of the Wild-type (WT) MMP12 PDB ID: 2WO8 as a template.

2. Selective MMP-12 Inhibitors That Were Used for Pharmacophore Model Development .

IC50 values of selective MMP-12 inhibitors were determined using purified enzyme.

These ligands were superimposed using MOE’s flexible alignment tool, and the common chemical features were extracted using the Pharmacophore Elucidation module.

The resulting pharmacophore model contained the following features: F1: one aromatic motif, F2: one aromatic motif, F3: one aromatic or hydrophobic motif, F4: one H-bond donor or acceptor moiety, and F5: one H-bond donor or acceptor moiety (Figure ). The pharmacophore model clarifies that MMP-12 inhibitors should bear three aromatic groups and two H-bond donor or acceptor groups. The pharmacophore model was screened against the ligand (ID: 077) (Figure ) and selective inhibitors, and it covers 96.1% of the list when using a partial match with four functional groups.

1.

Generated pharmacophore model of MMP-12 inhibitors using MOE.

2.

MMP-12 pharmacophore model with ligand (PDB ID: 077). Picture made by MOE.

Aro stands for: aromatic, Hyd: hydrophobic, Acc/Don: H-bond donor or acceptor.

2.2.2. Pharmacophore Searching

The generated pharmacophore was screened against the National Cancer Institute (NCI) database after filtering based on the molecular weight and Lipinski’s rule of 5 as described in the workflow (Figure ). Pharmacophore-based virtual screening was performed in MOE using the “best per conformer” option, with a minimum fit value threshold of 0.7. This screening process against the pharmacophore resulted in 85 hits for full matches (5 functionalities) and 15,525 hits for partial matches (4 functionalities). Figure illustrates the alignments of a full match hit against the pharmacophore model.

3.

Pharmacophore screening flow against NCI database and docking study for retrieved hits.

4.

MMP-12 pharmacophore model with full match hit (NCI ID:14161). Picture made by MOE.

The full match hits were docked against 2WO8 coordinates using the Glide docking protocol. This process yielded 45 hits with docking scores ranging from −11 to −2 kcal/mol. However, upon analyzing the results, it was observed that each compound generated multiple docking poses with varying scores. To ensure consistency, only the top-ranked pose was selected (i.e., the one with the most favorable docking score) for each compound for further analysis. Additionally, we found that some NSC numbers did not match any records in the NCI database, therefore further removal of those compounds is a must due to the lack of information, such as the compound structure. Ultimately, the Glide docking results in a total of 35 hits listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Conversely, the partial match hits were docked against 2WO8 using the virtual screening protocol. This virtual screening produced 700 hits with docking scores ranging from −15 to −4 kcal/mol. Similar to the full match hits, compounds with multiple docking scores were treated in the same manner. This filtering resulted in 120 hits, which are listed in Table S2.

2.2.3. Glide and Induced-Fit Docking

Docking studies evaluated the binding affinity and interaction patterns of both the synthesized and purchased compounds against wild-type (WT) and mutant (MUT) MMP-12 (Table ).

3. Glide Docking and Induced Fit Docking (IFD) Scores of the Purchased Hits (H1–H4) and Synthesized Compounds (C7–C27) against WT and MUT MMP-12.

Figures – showing the overlay of the synthesized compounds against the ligands DEO in (PDB ID: 1ROS) and K8T in (PDB ID: 6RLY) in green and blue, respectively, highlight meaningful interactions and structural alignments for each compound class. , The most active compounds from various chemical classes are incorporated, including cinnamic acid, ferulic acid, 2-chlorobenzoyl chloride, and indole-3-acetic acid. These compounds collectively exhibit high compatibility with the binding site. A. Wild protein (PDB ID: 1ROS).

5.

Superposition of the synthesized compounds of the ferulic acid analogues against the cocrystallized ligand DEO (green) in PDB ID: 1ROS. (A) Superimposition of (C9) against the cocrystallized ligand. (B) Superimposition of (C9 and C10) against the cocrystallized ligand. The dark gray sphere denotes the Zn2+ ion located within the active site.

8.

Superimposition of the synthesized compounds of the indole-3-acetic acid analogues against the cocrystallized ligand K8T (blue) in PDB ID: 6RLY. (A) Superimposition of (C26) against the cocrystallized ligand. (B) Superimposition of (C18–C27) against the cocrystallized ligand. The light gray sphere denotes the Zn2+ ion located within the active site.

6.

Superposition of the synthesized compounds of the indole-3-acetic acid analogues against the cocrystallized ligand DEO (green) in PDB ID: 1ROS. (A) Superimposition of (C26) against the cocrystallized ligand. (B) Superimposition of (C18– C27) against the cocrystallized ligand. The dark gray sphere denotes the Zn2+ ion located within the active site. A. Mutant protein (PDB ID: 6RLY).

7.

Superposing of the synthesized compounds of the ferulic acid analogues against the cocrystallized ligand K8T (blue) in PDB ID: 6RLY. (A) Superimposition of (C9) against the cocrystallized ligand. (B) Superimposition of (C9 and C10) against the cocrystallized ligand. The light gray sphere denotes the Zn2+ ion located within the active site.

To evaluate the accuracy of the induced fit docking (IFD) protocol, we compared the docked pose of the cocrystallized ligand with its native conformation in the 1ROS crystal structure. Superposition of the IFD-generated pose of ligand 077 with its crystallographic orientation yielded a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.7225 Å (Figure ), indicating excellent agreement. This low RMSD value demonstrates the reliability of the IFD approach in reproducing experimentally observed binding modes and highlights its effectiveness in accurately predicting ligand–protein interactions.

9.

Superposition of the IFD-docked pose of ligand 077 (pink) with its native conformation (green) in the 1ROS crystal structure. Image generated using PyMOL.

2.2.4. Prime MM-GBSA

Prime MM-GBSA analysis generated both positive and negative ΔG_binding values, reflecting the relative stability of receptor–ligand complexes. In this context, more negative ΔG_binding values are indicative of stronger and more favorable binding interactions, whereas positive values suggest weaker or unfavorable binding. , The mutant MMP-12 complex (PDB ID: 6RLY) consistently yielded negative binding free energy values, ranging from −11.36 to −43.86 kcal/mol, supporting the formation of stable docked complexes (Table ). Similarly, the wild-type MMP-12 complex (PDB ID: 1ROS) displayed a broader ΔG_binding range (−2.87 to −66.32 kcal/mol) (Table ). The overall negative values obtained for both WT and MUT systems emphasize the consistency of the docking results and suggest that the selected ligands can form energetically favorable interactions with the MMP-12 active site. These findings provide computational support for the inhibitory potential of the designed compounds and help rationalize the observed docking poses.

4. Binding Free Energy (ΔG_binding, Kcal/mol) of MMP-12-Ligand Complexes Calculated by Prime MM-GBSA.

| compound | MMGBSA ΔG binding PDB ID: 1ROS | MMGBSA ΔG binding PDB ID: 6RLY |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | 5.87 | 3.73 |

| H2 | 17.33 | 1.07 |

| H3 | 47.16 | –27.21 |

| H4 | 5.70 | –24.62 |

| C7 | 1.88 | –30.33 |

| C8 | 5.14 | –40.22 |

| C9 | –5.23 | –29.67 |

| C10 | –16.44 | –30.32 |

| C11 | –11.77 | –19.06 |

| C12 | –2.87 | –24.50 |

| C13 | –14.77 | –15.42 |

| C14 | –26.01 | –11.36 |

| C15 | –4.49 | –20.57 |

| C16 | 1.54 | –28.06 |

| C17 | –3.93 | –21.74 |

| C18 | –8.10 | –16.21 |

| C19 | 8.78 | 21.14 |

| C20 | 1.64 | –13.05 |

| C21 | –9.51 | –19.31 |

| C22 | –12.31 | –13.35 |

| C23 | –11.76 | –18.94 |

| C24 | –9.54 | –21.99 |

| C25 | –15.56 | –20.36 |

| C26 | –4.08 | –13.49 |

| C27 | –12.70 | –28.57 |

| Co-ligand (DEO) (PDB ID: 1ROS) | –66.32 | –15.15 |

| Co-ligand (K8T) (PDB ID: 6RLY) | –27.68 | –43.68 |

The developed pharmacophore model provides a rational framework for identifying diverse active inhibitors of MMP-12. It was built using MOE software and is based on superposition of known selective MMP-12 inhibitors against the cocrystallized ligand (ID:077) in PDB ID: 2WO8. The model features five key elements: three aromatic or hydrophobic motifs (F1–F3) and two hydrogen bond donor or acceptor groups (F4–F5). This configuration captures the essential interactions necessary for effective binding within the S1′ specificity pocket and the conserved catalytic groove of MMP-12. Notably, the model was able to map 96.1% of known selective MMP-12 inhibitors when allowing for partial matches of four features, indicating its strong coverage and validation against known active compounds. It was observed that the key binding site residues correspond well with the pharmacophoric features of active MMP-12 inhibitors. These include hydrophobic residues such as A181, A182, A234, and V243; aromatic residues including F237, Y240, and F248; the polar residue T239; the acidic residue D244; and basic residues K241, H218, and H228. This alignment highlights the complementary topological features between the ligand and the binding site.

The current pharmacophore model for MMP-12 inhibitors shows both similarities and improvements when compared to previously published models. For example, Devel, et al. highlighted the significance of aromatic moieties and hydrogen bond donors near the catalytic Zn2+. This observation aligns with our findings, which also identify several aromatic features and requirements for hydrogen bonding. Other models, such as those by Nuti et al. and Puerta et al., emphasize the importance of Zn2+-binding groups (ZBGs), which are typically coordinated through thiol, pyrone, and hydroxypyridinone functionalities. , Although our model does not explicitly feature a ZBG, it indirectly accounts for this interaction by including hydrogen bond donor and acceptor motifs near the Zn2+-binding region. These motifs can represent functional groups that interact with the catalytic Zn2+.

Our model stands out because it includes three distinct aromatic and hydrophobic features, compared to the one or two aromatic constraints typically found in most reported MMP pharmacophores. This increase in features may enhance specificity by utilizing the extended S1′ pocket in MMP-12, which can accommodate larger or more spatially dispersed hydrophobic groups. Therefore, our model may provide improved discriminatory power, especially when filtering libraries for selective MMP-12 binders instead of pan-MMP inhibitors.

The model demonstrated strong effectiveness during virtual screening, identifying 85 hits with five functionalities (full matches) and over 15,000 hits with four functionalities (partial matches) from the NCI database. Through docking, we were able to prioritize these results, refining them to 35 full-match hits and 120 partial-match hits, all of which exhibited favorable Glide scores and significant key interactions. These findings emphasize the utility of our pharmacophore, not just as a predictive tool, but also as a structural framework for designing potential MMP-12 inhibitors with improved affinity profiles.

The docking analysis of various compounds against the mutant MMP-12 structure (PDB ID: 6RLY) revealed several synthesized compounds with promising binding affinities, demonstrating docking score values of −11.03 to −5.93 kcal/mol. Among the compounds tested, (C24) exhibited the highest binding score of −11.03 kcal/mol. This strong score can be attributed to its interaction profile, which includes H-bonds with PRO-238, Glu-219, and LEU-181, as well as a π-stacking interaction with HIS-218, a crucial residue located near the catalytic Zn2+. The indole backbone of (C24) likely facilitates effective conjugation and planar alignment within the binding cleft, enabling optimal π-stacking and hydrogen bond geometries.

This analysis is supported by the work of Tsoukalidou et al., who investigated the interactions between hydroxypyridinone compounds and the binding site on 6RLY. They reported that the amide group in these compounds was stabilized by two hydrogen bonds with the backbone residues of Leu-181 and Pro-238. Furthermore, A QSAR study conducted by Hitaoka et al. highlighted the significance of specific residues within the MMP-12 active site in stabilizing ligand binding. The study identified HIS-218, HIS-222, and HIS-228 as key contributors through hydrophobic and π–π interactions. − These residues are crucial in orienting arylsulfone-based inhibitors within the binding pocket.

Compound C15 exhibited a high docking score of −9.47 kcal/mol. This high score is likely due to forming two halogen bonds with PHE-237, along with hydrogen bonds to THR-239 and Glu219. The combination of a halogen donor and an indole group enhances its binding efficiency through various interaction types, contributing to its fit within the S1′ pocket of MMP-12.

This finding is supported by previous docking studies involving (N-hydroxy-2-(N-hydroxyethyl)biphenyl-4-ylsulfonamido)acetamide, which demonstrated interactions with key MMP-12 residues, including His218, Glu219, THR-239, and ALA-182.

Compounds C27 and C10 ranked highly, each forming multiple H-bonds with key residues, specifically LEU-181 and TYR-240, which are located within or near the active site. Notably, C27 exhibited a complex interaction pattern, including π-stacking with HIS-218 and H-bonds with three residues (LEU-181, THR-215, and TYR-240). This multifaceted interaction likely stabilizes its binding pose, contributing to its competitive docking score of −8.35 kcal/mol.

Similar interaction patterns were observed in structural docking studies conducted by Nuti et al. (2005), which emphasized the collaborative role of THR-215, TYR-240, and HIS-218 in anchoring MMP-12 inhibitors within the extended S1′ region.

The common feature among the top-scoring ligands is their ability to engage in multipoint anchoring through H-bonding, often with residues that line the active site (LEU-181, TYR-240, and PRO-238). Additionally, they participate in π-interactions with HIS-218, a residue that consistently plays a significant role in strong aromatic stacking interactions.

When comparing the docking results with the WT MMP-12 (PDB ID: 1ROS), similar trends in residue preferences were observed. However, unique contributions from residues such as GLU-219, ALA-184, HIS-222, as well as Zn2+-coordinating interactions, were also evident. Compounds like C10 and C9 exhibited extensive π-stacking networks, involving multiple histidine and tyrosine residues, which helped to compensate the weaker H- bonding profile in the wild-type structure.

In contrast, metal coordination with the catalytic Zn2+ ion was primarily observed with ligands that contain benzothiazole or heteroaromatic scaffolds (e.g., C14). This suggests that there are additional binding modes that may account for the differences in selectivity between MUT and WT MMP-12. This observation aligns with earlier findings by Li et al. and Rouanet-Mehouas et al., who emphasized that heterocycles capable of Zn2+ chelation, such as imidazole, benzothiazole, and pyridine, demonstrate significant potential for binding metal ions due to their electron-rich structures. , This characteristic enhances their interaction with metalloproteinases, potentially increasing both binding affinity and selectivity. These results confirm that the interaction fingerprints of the top ligands in this study reflect the reported binding trends for effective MMP-12 inhibitors, thereby validating the docking protocol and compound prioritization strategy employed here.

2.3. Enzyme Inhibition Assay

The enzyme inhibition potential of the purchased hits and synthesized compounds against MMP-12 was evaluated using the Abcam colorimetric inhibitor screening assay (ab139441) (Table ). The principle of the assay depends on the cleavage of a chromogenic peptide substrate by active MMP-12. Then, the release of a thiol group produces a colorimetric signal measurable at 412 nm, where a reduction in absorbance implies successful enzyme inhibition.

5. Inhibitory Profiles and 50% Inhibitory Concentrations (IC50 (μM)) of the Tested Compounds against MMP-12.

| compound | % inhibition | IC50 (μM) | compound | % inhibition | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7 | 36.9% | NA | C20 | 26.2% | NA |

| C8 | 10.0% | NA | C21 | 42.0% | NA |

| C9 | 53.5% | 65.32 | C22 | 13.3% | NA |

| C10 | 28.7% | NA | C23 | 98.0% | 18.19 |

| C11 | 36.7% | NA | C24 | 96.0% | 19.13 |

| C12 | 9.0% | NA | C25 | 94.2% | 24.81 |

| C13 | 9.5% | NA | C26 | 93.3% | 25.52 |

| C14 | 8.0% | NA | C27 | 22.5% | NA |

| C15 | 30.0% | NA | H1 | 70.7% | 32.55 |

| C16 | 15.0% | NA | H2 | 33.3% | NA |

| C17 | 7.3% | NA | H3 | 76.7% | 30.97 |

| C18 | 10.0% | NA | H4 | 11.3% | NA |

| C19 | 4.0% | NA | NNGH | 98% | NA |

Among the tested series, several compounds confirmed considerable inhibitory activity. Notably, inhibitors (C23, C24, C25, and C26) bearing the indole-3-acetic acid scaffold presented more than 93% inhibition, identifying them as highly potent MMP-12 inhibitors. Furthermore, a compound built on the ferulic acid scaffold (C9) achieved around 54% inhibition, which is considered a profound inhibitory effect in an early stage screening. Also, two purchased hits (H1 and H3) exposed approximately 70% inhibition. These results offer valuable insights for further optimization of potential scaffolds paving the way for releasing effective MMP-12-targeted therapies. Dose–response inhibition curves for compounds C9, C23, C24, C25, C26, H1, and H3 are provided in Supplementary Figures S1–S7, based on quadruplicate measurements (n = 4) and analyzed using nonlinear regression to assess their inhibitory effects against MMP-12.

Previous data reported in the Cortellis database have identified indole-3-acetic acid derivatives as potential MMP-12 inhibitors with accompanying anticancer activity, indicating early recognition of this scaffold’s therapeutic significance. Yet, these findings have not been widely investigated or validated in peer-reviewed literature. In our study, compounds bearing the indole-3-acetic acid scaffold (C23, C24, C25, and C26) demonstrated exceptionally high inhibitory activity (>93%) against MMP-12, supporting and experimentally strengthening the reported pharmacological potential in Cortellis. Notably, compounds featuring the ferulic acid scaffold (C9) also presented good inhibition (∼54%), indicating that both scaffolds contribute to MMP-12 inhibition. Interestingly, a recent study stated that natural compounds present in propolis, which include derivatives structurally related to ferulic acid, showed potential MMP-12 inhibitory activity. These findings further support the relevance of the cinnamic acid–based scaffolds in targeting MMP-12. These findings position both indole-3-acetic acid and ferulic acid as promising chemotypes for future development of potent MMP-12 inhibitors.

The selection and synthesis of the verified inhibitors were guided by an integrated pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking approach, targeting the catalytic site of MMP-12. Compounds containing indole-3-acetic acid and ferulic acid scaffolds have emerged as key findings due to their alignment with pharmacophore features and favorable docking behavior.

Among the indole derivatives, C23 displayed the strongest predicted binding, with a glide docking score of −7.77, forming π–π stacking with HIS-218 and H- bonds with LEU-181 and PHE-237. Compound C24 (−7.73) bound to HIS-218 and formed multiple H- bonds with PHE-237, GLU-219, and ALA-182, while C26 (−7.69) showed similar binding features. All three compounds targeted essential residues around the Zn2+-binding catalytic domain, indicating a mechanism of inhibition through competitive occupancy of the active site.

The ferulic acid derivative (C9) showed a strong docking score of −7.62, surpassing the previously reported score of −5.59 for natural ferulic acid in the MMP-12 docking study. This derivative formed π–π stacking interactions with HIS-218 and H- bonds with LEU-181 and PRO-238, which support its stability and orientation within the binding pocket. The enzyme inhibitory activity observed with indole and ferulic scaffolds closely aligns with these computational predictions. This validates the effectiveness of the combined pharmacophore-docking design strategy for prioritizing MMP-12 inhibitors.

However, it is important to recognize the inherent limitations of computational hit prediction. Docking scores offer only an approximate estimate of binding affinity. Additionally, the simplified treatment of protein flexibility, solvation, and entropy can result in both false positives and false negatives. While in silico screening is useful for prioritizing scaffolds and reducing the number of compounds that need to be synthesized, experimental validation is essential to confirm actual biological activity. The discrepancies observed for some predicted hits in this study are consistent with these known limitations, highlighting the complementary nature of combining computational and experimental approaches.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Computational Methods

3.1.1. Pharmacophore Modeling

3.1.1.1. Preparation of Ligand Libraries

The MMP-12 inhibitors’ (ligands) database was constructed through an extensive search of Cortellis Drug Discovery Intelligence (CDDI), Protein Data Bank (PDB), PubChem, Google Scholar and PubMed research engines. CDDI database was searched for MMP-12 inhibitors having anticancer activity and this search resulted in two compounds only. Then, the search was generalized to include all MMP-12 inhibitors that were studied on human proteins with experimental data resulting in 200 compounds. PDB was explored for MMP-12 inhibitors using the following filters: Homo sapiens and resolution of (1.5–2.5 Å). PubMed was searched using the following filters: MMP-12 and inhibitors. The study gathered and included all the results from (1987- Jan. 2024). PubChem and Google Scholar search did not provide any new results other than PubMed. The chemical structures of the tabulated compounds were generated using ChemDraw version 16.0.

3.1.1.2. Pharmacophore Generation and Validation

The pharmacophore model was built using selective MMP-12 inhibitors by the Pharmacophore Query model in Molecular Operating Environment software (MOE). Compounds were considered selective if they had a 5-fold selectivity against MMP-12 over other MMPs. A curated list of selective inhibitors was compiled by collecting known active compounds from published literature and publicly available databases (Table ). The selective inhibitors were drawn in MOE using the cocrystallized ligand (ID: 077) of PDB ID: 2WO8 as a template that was identified as a selective MMP-12 inhibitor. , The inhibitors were aligned by flexible alignment at an energy cutoff of 15 and an iteration limit of 200. The radius of the pharmacophore spheres was corrected to be 1.2 Å for aromatic/and 1.0 Å for hydrogen bond acceptor/donor. The best model was attained by using a tolerance of 1.8 and a threshold of 50%.

3.1.2. Virtual Screening

3.1.2.1. Screening for Hits

A library of 265,542 compounds from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) database was implemented for screening. The NCI database was filtered based on Lipinski’s rule of five, while the molecular weight was between 200 and 600 g/mol. Then, the generated pharmacophore was screened against the treated NCI database.

3.1.3. Docking Studies

3.1.3.1. Protein Preparation

The X-ray crystal structures of wild protein (PDB ID: 1ROS) and mutant protein (F67 → D) (PDB ID: 6RLY) were retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. , The protein preparation wizard in the Schrödinger software suite was used to optimize the protein structures. Proteins were taken as a raw stage in which hydrogen atoms are missing with incorrect bond orders. In protein preparation, wizard hydrogens were added, bond order was assigned, and unwanted water molecules were removed. Then, the proteins’ side chains were subjected to 500 iterations of energy minimization using the OPLS force field in the MacroModel module in Schrödinger enterprise while the backbone atoms being restrained.

3.1.3.2. Preparations of Ligand Structures

The synthesized and reported MMP-12 inhibitors were prepared as follows: (1) 3D coordinates of all potential ligands were generated using the “Build” wizard in MAESTRO, based on the template of the cocrystallized quercetin structure in PDB ID: 2WO8; (2) the resulting 3D ligand structures were processed using the “LigPrep” module in MAESTRO for further optimization. Similarly, the retrieved NCI hits were also prepared using the LigPrep algorithm. In general, LigPrep evaluates and generates multiple chemical and structural variations from a single input structure, accounting for stereoisomerism, tautomerism, ring conformations, and ionization states.

3.1.3.3. Glide Docking

Two grid files for 1ROS and 6RLY were generated using the Glide Grid Generation protocol using the bound ligands as centroids. All reported inhibitors, NCI hits, and synthesized compounds were docked to each of the two grid files. During the docking process, the scaling factor for receptor van der Waals for the nonpolar atoms was set to 0.8 to allow for some flexibility of the receptor. All other parameters were used as defaults. The binding affinity of the MMP-12/ligand complexes was expressed as docking scores. The more negative the docking score, the more favorable the interaction of the complex. Unless stated otherwise, the figures of protein/ligand interactions were generated using Ligand Interaction algorithm in Maestro program. In these figures, the key binding residues, within 5Å, were identified and the enclosed ligand was probed to determine the bonding force.

3.1.3.4. Induced Fit Docking

Induced Fit Docking (IFD) was conducted using Schrödinger software to account for flexibility within the MMP-12 binding site. , The bound ligand of each crystal structure (PDB IDs: 1ROS and 6RLY) was used as the centroid to define the docking grid. , During the IFD protocol, the van der Waals scaling factors for receptor and ligand nonpolar atoms were adjusted to 0.5 to allow for greater conformational flexibility. All other parameters were calibrated as default. Ligands were initially docked using softened potentials, and the top-ranked pose based on XP Glide score was selected for each compound. The binding affinity of each MMP-12/ligand complex was expressed in terms of docking score (kcal/mol), where the more the negative values indicated stronger predicted binding interactions.

3.1.4. Prime MM-GBSA

The binding free energy of the WT and MUT MMP-12 receptor–ligand complexes was calculated using the Prime MM-GBSA (Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area) algorithm implemented in Schrödinger software, employing the OPLS_2005 force field. The binding free energy (ΔG_binding) of a ligand (L) interacting with a receptor (R) to form a complex (RL) were estimated from minimized complex structures according to the following equation

ΔG_binding represents the binding free energy, while ΔG_complex, ΔG_receptor, and ΔG_ligand represent the free energies of the complex, receptor, and ligand, respectively.

MM-GBSA calculations were conducted solely on available docked poses; therefore, compounds described as having “no binding” refer to poses with very poor docking quality rather than indicating an absolute failure to generate a pose.

3.2. Compound Acquisition and Synthesis

Based on the virtual screening approach against the pharmacophore modeling and docking studies, selected hits were either purchased or synthesized in-house. The commercially available hits (Table ) were provided from AmBeed (USA), and their identities and purities were confirmed through the provided analytical data.

6. Chemical Structures of Hit Compounds Identified via Ligand- and Structure- Drug Design Approaches.

3.2.1. Chemicals

Chemicals and solvents were purchased and used directly, as they were of analytical grade and highly purified, eliminating the need for further purification. The following chemical reagents were obtained from different suppliers: oxalyl chloride was purchased from Aldrich, India. Diethyl ether was supplied by ChemLab, while n-hexane (95%) was sourced from M-Tedia. Chloroform (CHCl3) 99.8% HPLC grade was obtained from Emsure-Company, and ethyl acetate (EtOAc) was supplied by Fisher-Scientific. Acetone 99.8% and ethanol (CH3CH2OH) were purchased from LABCHEM, and pyridine was obtained from BIOCHEM. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were also used in this study and were purchased from Aldrich, Germany.

Several benzophenone derivatives were sourced from Acros Organics, including 4-amino benzophenone, 3-amino benzophenone, 2-amino-5-chloro-benzophenone, 2-amino benzophenone, and 2-amino-4′-methyl-benzophenone. Additionally, cinnamic acid and 2-chlorobenzoyl chloride were procured from Aldrich, Germany.

Other compounds including 6-chloro-benzothiazol-2-ylamine, 2-amino-6-methoxybenzothiazole, 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethan-1-amine, and (E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acrylamide, and indole-3-acetic acid 98% were supplied by Gainland Chemical Company (GCC), UK.

A variety of anilines and related compounds were purchased from Aldrich, Germany, including p-toluidine, 2-(trifluoromethyl) aniline, 3-(trifluoromethyl) aniline, 3-chloro-4-fluoroaniline, 4-aminopyridine, 3-aminopyridine, 5-amino-1H-imidazole-4-carboxamide, 3-amino-5-methyl isoxazole, 4-hydroxybenzyl amine, and 4-chloro-2,5-dimethoxyaniline.

3.2.2. Instrumentation

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was conducted on precoated aluminum sheet measuring 20 × 20 cm with a thickness of 0.20 mm, featuring fluorescent silica gel (Macherey-Nagel, Germany), and was visualized using UV light (254/366 nm).

The evaporation of ordinary solvents was performed using a Rota vapor model R-215 (Buchi, Switzerland) connected to a vacuum pump V-700 and a heating water bath (Hei-VAP value digital, Heidolph). The melting point (MP) was assessed using the Gallenkamp melting point apparatus. Hot plates and magnetic stirrers were obtained from Thermo Scientific Cimarec. The 1H and 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra were analyzed by Bruker-Avance III 500 MHz spectrophotometer. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded using a Bruker APEX-IV (7 T) instrument (The University of Jordan). External calibration was performed using an arginine cluster within the m/z range of 175–871. Samples were dissolved in chloroform with the addition of a few drops of acetonitrile.

3.2.3. Synthesis of the Targeted Compounds

The synthesis procedures include acylation and amidation reactions, depending on the targeted scaffold. , All prepared compounds have been identified using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra by Bruker-Avance III 500 MHz spectrophotometer, chemical shifts are expressed in δ (ppm) and coupling constant (J) values are expressed in Hz (Hertz) using TMS internal reference; CDCl3 or DMSO-d 6 was used to dissolve the samples. A supplementary file was provided containing all relevant charts for the synthesized compounds.

3.2.3.1. Synthesis of Cinnamic Acid Scaffold

The cinnamic acid (N2) weighing 0.50 g (3.37 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of anhydrous CHCl3. Under the conditions of an ice bath, oxalyl chloride (1.15 mL, 13.48 mmol, 4 equiv) and three drops of DMF were added dropwise to the solution. The resulting mixture was refluxed for 24 h in an oil bath. Subsequently, the CHCl3 solvent, along with any unreacted oxalyl chloride, were removed by rotary evaporation, performing the process four times and washing with CHCl3 during each cycle. The reaction vessel was kept at RT to induce solid precipitation.

In a one-necked round-bottom flask, equipped with a reflux condenser and connected to a guard tube filled with MgSO4, a solution of cinnamic acyl chloride (N5) (3.00 mmol) in 20 mL of anhydrous CHCl3 was prepared. The mixture was stirred under an ice bath with anhydrous pyridine (1.4 mL, 18 mmol, 6 equiv). Subsequently, corresponding amine derivatives (Table ) (1:1 equiv), which had been dissolved in 15 mL of anhydrous CHCl3, was added to the reaction mixture in a portion-wise manner. The suspended formula was subjected to reflux in an oil bath temperature for 24 h. The reaction process was observed using TLC.

Upon completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed by washing the mixture with CHCl3 four times, utilizing a rotary evaporator. The resultant residue was then redissolved in EtOAc and subjected to an extensive wash with distilled water to eliminate any residual pyridine. The organic layer was subsequently separated using a separatory funnel. The solution was treated with drying agents, filtered, and allowed to evaporate in air to yield the desired product. During TLC testing, two spots were observed. Consequently, column chromatography was performed to isolate the desired product. The mobile phase consisted of a 70/30 mixture of n-hexane and EtOAc.

N-(4-benzoylphenyl)cinnamamide (C7): beige solid, yield = 40%, mp = 159–162 °C, R f = 0.666 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.60 (s, 1H, NH-amide), 7.89 (d, 2H, H9 – H13), 7.79 (t, 2H, H3 + H5), 7.73 (d, 2H, H2 + H6), 7.67 (d, 2H, H2′ + H6′), 7.65 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, H2″), 7.56 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H, H10 + H12), 7.46 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, H3′ + H5′), 7.44 (t, 2H, H4′, H11), 6.88 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H, H1″). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 194.2 (C7), 163.6 (Amide Carbon), 143.0 (c2″), 140.7 (C4), 137.2 (C8), 134.2 (C1′), 131.9 (C11), 131.1 (C1), 130.9 (C2 + C6), 129.6 (C9 + C13), 129.0 (C3′ + C5′), 128.7 (C10, C12), 128.1 (C2′ + C6′), 127.5 (C4′), 121.4 (C1″), 118.2 (C3 + C5). HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd for C22H18N1O2 [M + H]+: 328.13321; found, 328.13321.

N-(2-(4-methylbenzoyl)phenyl)cinnamamide (C8): white solid, yield = 22%, mp = 228–229 °C, R f = 0.1875 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.28 (s, 1H, NH-Amide), 7.73 (d, J = 8.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.65–7.61 (d, 2H), 7.61–7.53 (m, 3H), 7.45–7.34 (m, 5H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 2.35 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 195.0 (C7), 163.74 (Amide Carbon), 143.1 (C11), 140.7 (C2″), 136.4 (C2), 134.7 (C1, C8), 134.7 (C4), 131.7 (C6), 130.0 (C2′ + C6′), 130.0 (C4′), 129.1 (C9 + C13, C10 + C12), 128.9 (C3′ + C5′), 127.9 (C1″), 124.2 (C1), 123.6 (C5), 121.7 (C3).

3.2.3.2. Synthesis of Ferulic Acid Scaffold

The (E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acrylamide (ferulic acid) (N3) weighing 0.5 g (5.15 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of anhydrous CHCl3. Under the conditions of an ice bath, oxalyl chloride (1.77 mL, 20.6 mmol, 4 equiv) and three drops of DMF were added dropwise to the solution. The resulting mixture was refluxed for 24 h in an oil bath. Subsequently, the CHCl3 solvent, along with any unreacted oxalyl chloride, were removed by rotary evaporation, performing the process four times and washing with CHCl3 during each cycle. The reaction vessel was kept at RT to induce solid precipitation.

In a one-necked round-bottom flask, equipped with a reflux condenser and connected to a guard tube filled with MgSO4, a solution of 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)propanoyl chloride (N6) (2.35 mmol) in 20 mL of anhydrous CHCl3 was prepared. The mixture was stirred under an ice bath with anhydrous pyridine (0.76 mL, 9.4 mmol, 4 equiv). Subsequently, corresponding amine derivatives (Table ) (1:1 equiv), which had been dissolved in 15 mL of anhydrous CHCl3, was added to the reaction mixture in a portion-wise manner. The suspended formula was subjected to reflux at an oil bath temperature for a duration of 24 h. The reaction process was observed using TLC.

Upon completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed by washing the mixture with CHCl3 four times, utilizing a rotary evaporator. The resultant residue was then redissolved in EtOAc and subjected to an extensive wash with distilled water to eliminate any residual pyridine. The organic layer was subsequently separated using a separatory funnel. The solution was treated with drying agents, filtered, and allowed to evaporate in air to yield the desired product. During TLC testing, two spots were observed. Consequently, column chromatography was performed to isolate the desired product. The mobile phase consisted of a 70/30 mixture of n-hexane and EtOAc.

(E)-N-(4-benzoylphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acrylamide (C9): cream white solid, yield = 30%, mp = 225–228 °C, R f = 0.333 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.49 (s, 1H, NH-amide), 9.59 (s, 1H, OH(B), 7.87 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H9′ + H13′), 7.76 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H, H3′ + H5′), 7.65 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H2″), 7.56 (td, J = 8.1, 3.5 Hz, 3H, H10′ + H12′, H11′), 7.21 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, H2), 7.09 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H, H6), 6.84 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.68 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, H1″), 3.83 (s, 3H, CH3(A)), 1.22 (s, 1H). 13 C NMR 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 195.0 (C7′), 164.9 (Amide Carbon), 149.3 (C3), 148.3 (C4), 144.1 (C2″ – C1′), 142.1 (C8′), 138.0 (C4′), 132.8 (C11′), 132.6 (C1), 131.7 (C3′ + C5′, C9′ + C13′), 129.8 (C10′ + C12′), 128.9 (C2′ + C6′), 122.7 (C2), 118.7 (C6), 116.2 (C5), 111.3 (C1″), 56.0 (CH3 (A)).

(E)-N-(3-benzoylphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acrylamide (C10): white solid, yield = 30%, mp = 240–141 °C, R f = 0.45 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.33 (s, 1H, NH-Amide), 9.56 (s, 1H, OH (B), 8.12 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, H2″), 8.05–7.96 (m, 1H, H11), 7.79–7.65 (m, 3H, H2, H9 + H13), 7.61–7.47 (m, 4H, H4, H6, H10 + H12), 7.45–7.39 (t, 1H, H5), 7.19 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H,, H2′), 7.07 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H, H6′), 6.83 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H5′), 6.62 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, H1″), 3.82 (s, 3H, A). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 195.2 (C7), 163.8 (Amide Carbon), 148.3 (C3′), 147.4 (C4′), 140.6 (C1), 139.1 (C2″), 136.5 (C8), 132.2 (C3), 129.1 (C5 + C9, C13), 128.6 (C11), 128.1 (C1′ + C4+ C10, C12), 122.5 (C6), 121.6 (C6′), 119.6 (C1″), 117.9 (C2), 115.2 (C5′), 110.3 (C2′), 55.0 (C (A) methoxy).

3.2.3.3. Synthesis of 2-Chlorobenzoyl Chloride Scaffold

In a one-necked round-bottom flask, equipped with a reflux condenser and connected to a guard tube filled with MgSO4, a solution of 2-chlorobenzoyl chloride (N9) (0.5 g, 2.8 mmol) in 20 mL of anhydrous CHCl3 was prepared. The mixture was stirred under an ice bath with anhydrous pyridine (1.4 mL, 18 mmol, 6 equiv). Subsequently, corresponding amine derivatives (Table ) (1:1 equiv), which had been dissolved in 15 mL of anhydrous CHCl3, was added to the reaction mixture in a portion-wise manner. The suspended formula was subjected to reflux at an oil bath temperature at 90 °C for 24 h. The reaction process was observed using TLC.

Upon completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed by washing the mixture with CHCl3 four times, utilizing a rotary evaporator. The resultant residue was then redissolved in EtOAc and subjected to an extensive wash with distilled water to eliminate any residual pyridine. The organic layer was subsequently separated using a separatory funnel. The solution was treated with drying agents, filtered, and allowed to evaporate in air to yield the desired product. The product produced a single spot during TLC testing.

N-(2-benzoyl-4-chlorophenyl)-2-chlorobenzamide (C11): beige solid, yield = 50%, mp = 137–139 °C, R f = 0.258 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.66 (s, 1H, NH), 7.71 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H, C9, C13 + C3 + C6′), 7.66 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H4′), 7.54 (m, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H, H10, H12 + H6), 7.50–7.45 (m, 1H, H4), 7.43 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, H11), 7.30 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H5′), 6.78 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H3′). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 192.8 (C7), 164.5 (Amide Carbon), 136.3 (C2), 135.4 (C1′), 134.0 (C2′), 133.4 (C4′ + C8), 132.8 (C4), 131.1 (C6), 129.5 (C6′), 129.4 (C9, C13 + C3′), 129.1 (C11), 128.9 (C5), 128.2 (C10, C12 + C5′), 126.7 (C1), 126.0 (C3). HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd for C20H13Cl2N1Na1O2 [M + Na]+: 392.02156; found, 392.02156.

N-(2-benzoylphenyl)-2-chlorobenzamide (C12): yellow solid, yield = 66%, mp = 125–127 °C, R f = 0.533 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.63 (s, 1H, NH), 7.71 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 4H, H3 + H6 + H9, H13), 7.63 (dt, J = 14.8, 7.8 Hz, 1H, H4′), 7.50 (dd, J = 22.5, 7.7 Hz, 4H, H5′ + H6′ + H10, H12), 7.43 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, H11), 7.37 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H4), 7.31 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.87 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H3′). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 194.8 (C7), 164.6 (Amide Carbon), 137.2 (C2), 135.9 (C2′), 135.6 (C8), 132.6 (C1′), 131.8 (C6), 131.5(C11), 131.2 (C4′), 130.0 (C3′), 129.7 (C4), 129.6 (C6′), 128.4 (C1), 128.3 (C9, C13 + C10, C12), 126.9 (C5′), 125.0 (C5), 124.1 (C3). HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd for C20H15Cl1N1O2 [M + H]+: 335.788; found, 336.07858.

2-Chloro-N-(6-chlorobenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)benzamide (C13): white solid, yield = 74%, mp = 204–205 °C, R f = 0.256 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 13.04 (s, 1H, NH), 8.19 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, H3), 7.79 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, H6′), 7.70 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H3′), 7.60–7.55 (m, 2H, H5′ + H6),7.49 (m, 2H, H4’+H5). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 165.84 (Amide Carbon), 158.6 (C1), 147.3 (C8), 133.9 (C4′), 133.2 (C2′), 132.2 (C1′), 130.3 (C7), 129.8 (C3′), 129.5 (C6′), 127.9 (C4), 127.2 (C5′), 126.6 (C5), 121.9 (C6), 121.5 (C3).

2-Chloro-N-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)benzamide (C14): beige solid, yield = 89%, mp = 161–164 °C, R f = 0.184 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 12.87 (s, 1H, NH), 7.78 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H6′), 7.68 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H, H3′ + H6), 7.62 (s, 1H, H3), 7.58 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H4′), 7.48 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H5′), 7.06 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, H5), 3.83 (s, 1H, H(A)). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 165.4 (Amide Carbon), 156.3 (C4), 142.5 (C1), 134.2 (C1′), 132.8 (C2′), 132.0 (C4′), 130.3 (C8), 129.8 (C3′), 129.5 (C6′), 127.2 (C5′), 121.3 (C6), 115.1 (C5), 104.7 (C4), 55.6 ((A) methoxy).

N-(2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl)-2-chlorobenzamide (C15): beige solid, yield = 49%, mp = 125–129 °C, R f = 0.166 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.83 (s, 1H, H3), 8.54 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 7.57 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H6′), 7.49 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H7), 7.46–7.39 (m, 1H, H5′), 7.38 (d, 1H, H3′), 7.35 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H4), 7.21 (s, 1H, H2), 7.07 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H4′ + H5), 6.99 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H6), 3.52 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, H2″), 2.95 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, H1″). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 166.2 (Amide Carbon), 137.2 (C9), 136.2 (C2′), 130.5 (C1′), 129.8 (C4′), 129.5 (C6′), 128.8 (C3′), 127.2 (C8), 127.0 (C5′), 122.7 (C2), 120.9 (C5), 118.2 (C6 + C7), 111.6 (C1), 111.3 (C4), 40.0 (C1″), 24.9 (C2″). HRMS (ESI) m/z: calcd for C17H15Cl1N2Na1O1 [M + Na]+: 321.7600; found, 321.07651.

N-(4-benzoylphenyl)-2-chlorobenzamide (C16): white solid, yield = 68%, mp = 164–165 °C, R f = 0.636 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.91 (s, 1H, NH-amide), 7.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H3′ + H5′), 7.79 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H, H2′ + H6′), 7.73 (d, 2H, H9′ + H13′), 7.70–7.45 (m, 7H, H10′ + H12′, H11′, H3, H4, H5, H6). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 194.5 (C7′), 165.2 (Amide Carbon), 142.7 (C2), 137.3 (C1′), 136.4 (C8′), 132.2 (C4′), 131.8 (C3), 131.2 (C4), 130.9 (C11′), 129.5 (C1), 129.3 (C9′ – C13′ – C3′ – C5′), 128.8 (C6), 128.3 (C10′ – C12′), 127.2 (C5), 118.7 (C2′ – C6′).

2-Chloro-N-(2-(4-methylbenzoyl)phenyl)benzamide (C17): cream white, yield = 17%, mp = 227–228 °C, R f = 0.833 (EtOAc: n-hexane 1:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.58 (s, 1H, NH-Amide), 7.62 (m, J = 8.9, 6.0 Hz, 4H, H3, H6′, H9+H13), 7.55–7.40 (m, 3H, H4, H3′, H4′), 7.40–7.29 (m, 4H, H5, H5′, H10′ + H12′), 6.91 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H, H6), 2.39 (s, 3H, A). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 194.2 (C7), 164.2 (Amide carbon), 142.7 (C11), 135.6 (C2), 135.3 (C8), 134.3 (C2′), 131.4 (C4′), 131.3 (C1′), 130.9 (C4), 129.6 (C6), 129.4 (C9 + C13, C3′), 129.4 (C6′), 128.5 (C10 + C12), 128.2 (C5), 126.6 (C5′), 124.6 (C1), 123.8 (C3), 20.8 (CH3 (A)).

3.2.3.4. Synthesis of 3-Indole Acetic Acid Scaffold

The indole-3-acetic acid 98% (N7) weighing 0.50 g (2.853 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of anhydrous CHCl3. Under the conditions of an ice bath, oxalyl chloride (0.979 mL, 11.41 mmol, 4 equiv) and three drops of DMF were added dropwise to the solution. The resulting mixture was refluxed for 24 h in an oil bath. Subsequently, the CHCl3 solvent, along with any unreacted oxalyl chloride, were removed by rotary evaporation, performing the process four times and washing with CHCl3 during each cycle. The reaction vessel was kept at RT to induce solid precipitation.

In a one-necked round-bottom flask, equipped with a reflux condenser and connected to a guard tube filled with MgSO4, a solution of 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)acetyl chloride (N8) (2.58 mmol) in 20 mL of anhydrous CHCl3 was prepared. The mixture was stirred under an ice bath with anhydrous pyridine (0.831 mL, 2.58 mmol, 4 equiv). Subsequently, corresponding amine derivatives (Table ) (1:1 equiv), which had been dissolved in 15 mL of anhydrous CHCl3, was added to the reaction mixture in a portion-wise manner. The suspended formula was subjected to reflux at an oil bath temperature for 24 h. The reaction process was observed using TLC.

Upon completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed, by washing with CHCl3 four times using a rotary evaporator. The residue was then redissolved in CHCl3 and washed with an excess amount of distilled water to eliminate any residual pyridine. The desired product was collected after the evaporation of the solvent and subsequently recrystallized by CH3CH2OH to extract pyridinium chloride from the final product. The purified product was precipitated and separated from CH3CH2OH by filtration. The product produced a single spot during TLC testing.

2-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(p-tolyl)acetamide (C18): bronze solid, yield = 90%, mp = 124–125 °C, R f = 0.57 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1 H NMR 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.15 (S, 1H, H3), 7.43 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.09 (s, 1H, H2), 7.03 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H7), 6.93 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H, H6), 6.89 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, H3′ + H5′), 6.67 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, H2′ + H6′), 4.66 (s, 2H, H1″), 2.07 (s, 3H, CH3(A)). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 178.5 (Amide Carbon), 141.7 (C4′), 137.6 (C4), 131.9 (C1′), 131.4 (C3′+C5′), 128.7 (C9), 125.4 (C2), 123.2 (C7), 120.6 (C6), 120.2 (C8), 119.1 (C2′ + C6′), 113.2 (C1), 109.9 (C5), 33.6 (C1″), 21.5 (CH3(A)).

2-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)acetamide (C19): orange solid, yield = 82%, mp = 124–125 °C, R f = 0.48 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.51 (s, 1H, H3), 9.56 (s, 1H, NH-Amide) 7.45 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H6′), 7.35 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H3′), 7.26 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.23 (t, 1H, H7), 7.14 (s, 1H, H2), 7.05 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H4′), 6.95 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H5′), 6.77 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.60 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6), 4.50 (s, 2H, H1″). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 175.4 (Amide Carbon), 146.2 (C1′), 136.8 (C4), 134.0 (C3′, C5′), 126.7 (C(A)), 122.2 (C2), 119.7 (C9), 117.8 (C2′), 112.3 (C5), 108.2 (C1) 98.2 (C4′), 67.8 (C6′), 67.3 (C6), 33.6 (C7), 31.6 (C1″), 23.8 (C8).

2-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)acetamide (C20): white solid, yield = 87%, mp = 121 – 125 °C, R f = 0.50 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1 H NMR 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 7.39 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H4′), 7.28 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.10–6.95 (m, 3H, H2, H2′, H5′), 6.91 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H, H6 + H7), 6.34 (dd, J = 13.7, 9.1, 2.2 Hz, 1H, H6′), 6.25 (pd, J = 15.7, 7.2 Hz, 1H, H5), 4.62 (s, 1H, H1″). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 176.8 (AmideCarbon), 137.6 (C1′, C4), 132.2 (C3′), 132.1 (C5′), 128.7 (C9), 125.5 (C2′), 123.2 ((C2, C6′, CF3(A)), 120.6 (C6, C4′), 120.1 (C7), 117.1 (C8), 113.2 (C5), 112.7 (C1).

N-(3-chloro-4-fluorophenyl)-2-(1H-indol-3-yl)acetamide (C21): dark red solid, yield = 81%, mp = 146–150 °C, R f = 0.53 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.63 (S, H3), 7.48 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H5′), 7.37 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H6′), 7.19 (s, 1H, H2′), 7.07 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.02–6.91 (m, 2H, H2, H7), 6.70 (dd, J = 6.3, 2.8 Hz, 1H, H8), 6.53 (dt, J = 8.8, 3.4 Hz, 1H, H5), 4.44 (s, 2H, H1″), 3.65 (s, 2H, H2O). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 175.0 (AmideCarbon), 149.6 (C4′), 136.7 (C4), 127.8 (C9), 124.8 (C1′), 124.6(C2), 122.2 (C6), 120.1 (C3′), 119.6 (C7), 119.3 (C8), 117.5 (C5′), 115.8 (C2′), 114.9 (C6′), 112.3 (C5), 108.2 (C1), 31.7 (C1″).

2-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(pyridin-4-yl)acetamide (C22): beige solid, yield = 89%, mp = 105–106 °C, R f = 0.49 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.89 (s, 1H, NH-Indole), 7.98 (d, 2H, H3′+H5′), 7.52 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.35 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.21 (s, 1H, H2), 7.07 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H6), 6.97 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H7), 6.50 (d, 2H, H2′ + 6′), 6.21 (s, 1H, NH Amide), 4.23 (s, 2H, H1″). 13 C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO): δ 174.3 (Amide Carbon), 155.1 (C1′), 148.5 (C 3′ + C5′), 136.3 (C4), 127.6 (C9), 123.9 (C2), 121.1 (C6), 118.9 (C8), 118.5 (C7), 111.5 (C5), 109.1 (C1), 109.0 (C2′ + C6′), 32.3 (C1″).

2-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(pyridin-3-yl)acetamide (C23): brown solid, yield = 75%, mp = 120–121 °C, R f = 0.52(EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.90 (s, 1H, H3), 7.98 (d, 2H, H8), 7.52 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H6′)), 7.35 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H4′, H5), 7.21 (s, 1H, H2), 7.07 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H7), 6.97 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H6), 6.49 (d, 1H, H5′), 6.17 (s, 1H, H2′), 3.61 (s, 1H, H1″). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 174.0 (AmideCarbon), 148.5 (C4′), 136.1 (C4,C2′,C1′), 127.4 (C2,C9,C6′), 123.8 (C5′), 120.9 (C6), 118.7 (C7), 118.3 (C8), 111.3 (C5), 108.9 (C1), 32.0 (C1″).

5-(2-(1H-indol-3-yl)acetamido)-1H-imidazole-4-carboxamide (C24): beige solid, yield = 93%, mp = 160–165C°, R f = 0.42 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.91 (s, 1H, H3), 7.56 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H3′), 7.40 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.28 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.22 (s, 1H, H2), 7.11 (t, 1H, H6), 7.02 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H7), 6.94 (s, 2H, H7′), 3.72 (s, 2H, H1″). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 173.8 (Amide carbon), 165.9 (C6′), 146.2 (C1′), 136.2 (C4, C3′), 129.8 (C9), 127.3 (C2), 124.0 (C7), 121.1 (C6), 118.7, 118.6 (C8), 111.5 (C5′), 109.0 (C5), 107.8 (C1), 31.2 (C1″).

2-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(5-methylisoxazol-3-yl)acetamide (C25): yellow solid, yield = 90%, mp = 100–101 °C, R f = 0.47 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.89 (s, 1H, H3), 7.50 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.35 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.23 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, H2), 7.08 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H6), 6.98 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H7), 5.57 (s, 1H, H5′), 3.64 (s, 1H, H1″), 2.20 (s, 3H, CH3(A)). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 173.0 (Amide Carbon), 167.2 (C4′), 163.9 (C1′), 135.9 (C4), 127.1 (C9), 123.8 (C2), 120.8 (C6), 118.4 (C8), 118.3 (C7), 111.2 (C5), 107.5 (C1), 94.2 (C5′), 30.8 (C1″), 11.8 (C(A)).

N-(4-hydroxybenzyl)-2-(1H-indol-3-yl)acetamide (C26): cream white solid, yield = 89%, mp = 146–150 °C, R f = 0.55 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.80 (s, 1H, H3), 7.52 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.32 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.18–7.13 (m, 3H, H2, H2′ + H6′), 7.04 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H6), 6.94 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H7), 6.72 (d, 2H, H3′ + H5′), 4.51 (s, 2H, H2″), 3.70 (s, 2H, H1″). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 174.4 (AmideCarbon), 156.8 (C4′), 135.9 (C4), 129.2 (C2′ + C6′), 128.3 (C9), 127.5 (C1′), 123.2 (C2), 120.5 (C6), 118.7 (C7), 117.8 (C8), 114.9 (C3′ + C5′), 111.0 (C5), 109.9 (C1), 42.9 (C2″), 33.1 (C1″).

N-(4-chloro-2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-(1H-indol-3-yl)acetamide (C27): cream white solid, yield = 91%, mp = 124–125 °C, R f = 0.59 (EtOAc: n-hexane 2:3, v/v). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.80 (s, 1H, H3), 7.48 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.36 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.20 (s, 1H, H2), 7.07 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H7), 6.98 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H6), 6.78 (s, 1H, H6′), 6.47 (s, 1H, H3′), 3.97 (s, 2H, H1″), 3.67 (s, 6H, HA + HB). 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ 174.1 (AmideCarbon), 149.6 (C5′), 141.1 (C2′), 138.0 (C4), 127.7 (C9), 124.5 (C1′), 124.4 (C2), 121.8 (C6), 119.2 (C8), 113.2 (C4′), 112.0 (C3′), 112.0 (C5), 108.1 (C1), 106.9 (C6′), 100.2 (C7), 56.7 (OCH3-CA), 56.7 (OCH3–CB), 31.52 (C1″).

3.3. MMP-12 Enzyme Inhibition Assay

The inhibitory activity of both synthesized and purchased compounds against MMP-12 was evaluated using the Abcam MMP12 Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit (Abcam Cat. No ab139441). This assay employs a thiopeptide substrate (Ac-PLG-[2-mercapto-4-methyl-pentanoyl]-LG-OC2H5), which, when cleaved by active MMP-12, releases a sulfhydryl group that reacts with DTNB (Ellman’s reagent) to produce a yellow-colored product. This product is measured at 412 nm.

Recombinant human MMP-12 enzyme (10 U/μL) was diluted 1:285 in the provided assay buffer. Test compounds were dissolved in assay buffer and prepared at a concentration of 50 μM. These were then preincubated with the enzyme at 37 °C for 60 min. The enzymatic reaction was initiated by adding the diluted thiopeptide substrate (1:25 dilution in assay buffer), and absorbance was monitored at 412 nm at 1 min intervals for up to 20 min using a microplate reader. Negative controls, consisting of the enzyme without inhibitor, and positive controls, including the enzyme with NNGH, were included in the experiment. The compounds with the highest inhibition percent were evaluated at different concentrations (100, 50, 25, and 12.5 μM) to determine their IC50 values. The IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.1.

4. Conclusion

This study successfully applied a structure-based drug design approach that combined pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking to identify indole-3-acetic acid derivatives as promising inhibitors of MMP-12. The indole compounds showed strong docking scores and formed stable interactions with key binding residues in the MMP-12 catalytic site, including HIS-218, PHE-237, GLU-219, and LEU-181. These predictions were supported by enzyme inhibition assays, in which the selected indole derivatives achieved more than 94% inhibition of MMP-12 activity. The high level of agreement between the computational and biological results underscores the potential of indole-3-acetic acid scaffolds as effective leads for developing selective therapeutics targeting MMP-12.

Supplementary Material

All data is available throughout the text and Supplementary File. Clinical Trials Not applicable.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c06528.

Supplementary Figures S1–S7. Dose–response inhibition curves of compounds (C9, C23, C24, C25, C26, H1, and H3) against MMP-12 Supplementary Figures S8–S28. 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS (ESI) spectra of synthesized compounds. Table S1. The Glide docking score (kcal/mol) and interaction forces of the full match hits-based on virtual screening. Table S2. The Glide docking score (kcal/mol) and interaction forces of the partial match hits-based on virtual screening. Table S3. The Glide docking score (kcal/mol) and interaction forces of reported inhibitors against WT MMP-12 (PDB ID: 6RLY) and MUT MMP-12 (PDB ID: 1ROS) (PDF)

Conceptualization: SB, DS, and RH; Data curation: SA, DS, KS and SB ; Formal analysis: SA, DS, KS, RH and SB; Funding acquisition SB; Investigation SA, DS, KS and SB; Methodology: SA, DS, KS and SB; Project administration: SB; Resources: RH, DS, KS and SB ; Software: DS and RH; Supervision: SB; Validation: SB and DS ; Writingreview and editing:: SA, DS, KS, RH and SB.

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at the University of Jordan, grant number 2566. The computational studies are funded by were supported by a grant from the Deanship of Scientific Research at Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan, grant number 2023-2022/17/50 and 2025-2024/06/29

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Bassiouni W., Ali M. A., Schulz R.. Multifunctional intracellular matrix metalloproteinases: implications in disease. FEBS J. 2021;288(24):7162–7182. doi: 10.1111/febs.15701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi S.. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases inhibitors in cancer treatment: an updated review (2013–2023) Molecules. 2023;28(14):5567. doi: 10.3390/molecules28145567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan L.. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases induce extracellular matrix degradation through various pathways to alleviate hepatic fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023;161:114472. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Chen J., Sun H., Zhang Y., Zou D.. New insights into fibrosis from the ECM degradation perspective: the macrophage-MMP-ECM interaction. Cell Biosci. 2022;12(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s13578-022-00856-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niland S., Riscanevo A. X., Eble J. A.. Matrix metalloproteinases shape the tumor microenvironment in cancer progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(1):146. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aristorena M.. et al. MMP-12, secreted by pro-inflammatory macrophages, targets endoglin in human macrophages and endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(12):3107. doi: 10.3390/ijms20123107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.-S., Tang Y. X., Zhang W., Li J. D., Huang H. Q., Liu J., Fu Z. W., He R. Q., Kong J. L., Zhou H. F.. et al. MMP12 is a Potential Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker of Various Cancers Including Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241235468. doi: 10.1177/10732748241235468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson Ström J.. et al. Airway MMP-12 and DNA methylation in COPD: an integrative approach. Respir. Res. 2025;26(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s12931-024-03088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarawneh N., Hamadneh L., Alshaer W., Al Bawab A. Q., Bustanji Y., Abdalla S.. Downregulation of aquaporins and PI3K/AKT and upregulation of PTEN expression induced by the flavone scutellarein in human colon cancer cell lines. Heliyon. 2024;10(20):e39402. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwahsh M.. et al. Glutathione and xanthine metabolic changes in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cell lines are mediated by down-regulation of GSS and XDH and correlated to poor prognosis. J. Cancer. 2024;15(13):4047. doi: 10.7150/jca.96659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Hamid N. M., Abass S. A.. Matrix metalloproteinase contribution in management of cancer proliferation, metastasis and drug targeting. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021;48(9):6525–6538. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06635-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitluri K. K., Emerson I. A.. The importance of protein domain mutations in cancer therapy. Heliyon. 2024;10(6):e27655. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada H., Takahashi T.. Genetic alterations of multiple tumor suppressors and oncogenes in the carcinogenesis and progression of lung cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21(48):7421–7434. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waarts M. R., Stonestrom A. J., Park Y. C., Levine R. L.. Targeting mutations in cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2022;132(8):e154943. doi: 10.1172/jci154943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman R.. Computational studies of protein–drug binding affinity changes upon mutations in the drug target. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022;12(1):e1563. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tallant C., Marrero A., Gomis-Rüth F. X.. Matrix metalloproteinases: fold and function of their catalytic domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 2010;1803(1):20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno A.. et al. Understanding the variability of the S1′ pocket to improve matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor selectivity profiles. Drug Discovery Today. 2020;25(1):38–57. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiotakis, A. ; Dive, V. . Third-generation MMP inhibitors: recent advances in the development of highly selective inhibitors. The cancer degradome: proteases and cancer biology; Springer, 2008; pp 811–825. 10.1007/978-0-387-69057-5_38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raeeszadeh-Sarmazdeh M., Do L. D., Hritz B. G.. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors: potential for the development of new therapeutics. Cells. 2020;9(5):1313. doi: 10.3390/cells9051313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano D.. et al. Drug design by pharmacophore and virtual screening approach. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(5):646. doi: 10.3390/ph15050646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanzione F., Giangreco I., Cole J. C.. Use of molecular docking computational tools in drug discovery. Prog. Med. Chem. 2021;60:273–343. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmch.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Wang Y., Xu F.. Impact of the subtle differences in MMP-12 structure on Glide-based molecular docking for pose prediction of inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2014;1076:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bank, RPD 6RLY. 2019. (accessed May 20, 2025); Available from: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6RLY.

- ChemicalBook . Reactions and Applications of Oxalyl Chloride. 2024. (accessed May 20, 2025); Available from: https://www.chemicalbook.com/article/reactions-and-applications-of-oxalyl-chloride.htm.

- Morsch, L. Chemistry of Amides. 2023. (accessed May 20, 2025); Available from: https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Organic_Chemistry/Organic_Chemistry_(Morsch_et_al.)/21%3A_Carboxylic_Acid_Derivatives-_Nucleophilic_Acyl_Substitution_Reactions/21.07%3A_Chemistry_of_Amides.

- MOE, The Molecular operating; Environment Chemical Computing Group, Inc: Montreal, Quebec Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes I. P.. et al. The identification of β-hydroxy carboxylic acids as selective MMP-12 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19(19):5760–5763. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aerts J.. et al. Synthesis and Validation of a Hydroxypyrone-Based, Potent, and Specific Matrix Metalloproteinase-12 Inhibitor with Anti-Inflammatory Activity In Vitro and In Vivo. Mediators Inflammation. 2015;2015(1):510679. doi: 10.1155/2015/510679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitaoka S., Chuman H., Yoshizawa K.. A QSAR study on the inhibition mechanism of matrix metalloproteinase-12 by arylsulfone analogs based on molecular orbital calculations. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13(3):793–806. doi: 10.1039/C4OB01843E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio C.. et al. HTS by NMR for the Identification of Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Metalloenzymes. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;9(2):137–142. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio C.. et al. Therapeutic targeting of MMP-12 for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63(21):12911–12920. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M.. et al. Discovery of a new class of potent MMP inhibitors by structure-based optimization of the arylsulfonamide scaffold. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4(6):565–569. doi: 10.1021/ml300446a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnussen H.. et al. Safety and tolerability of an oral MMP-9 and-12 inhibitor, AZD1236, in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD: a randomised controlled 6-week trial. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;24(5):563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devel L.. et al. Development of selective inhibitors and substrate of matrix metalloproteinase-12. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(16):11152–11160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuffaro D.. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-12 inhibitors: synthesis, structure-activity relationships and intestinal absorption of novel sugar-based biphenylsulfonamide carboxylates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26(22):5804–5815. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani M., Shamsara J.. An integrated structure-and pharmacophore-based MMP-12 virtual screening. Mol. Diversity. 2018;22:383–395. doi: 10.1007/s11030-017-9804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.. et al. Prediction of matrix metal proteinases-12 inhibitors by machine learning approaches. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019;37(10):2627–2640. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1492460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devel L.. et al. Insights from selective non-phosphinic inhibitors of MMP-12 tailored to fit with an S1′ loop canonical conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(46):35900–35909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannino C.. et al. Synthesis of bicyclic molecular scaffolds (BTAa): an investigation towards new selective MMP-12 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14(22):7392–7403. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dublanchet A.-C.. et al. Structure-based design and synthesis of novel non-zinc chelating MMP-12 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15(16):3787–3790. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales R.. et al. Crystal structures of novel non-peptidic, non-zinc chelating inhibitors bound to MMP-12. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341(4):1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nar H.. et al. Crystal structure of human macrophage elastase (MMP-12) in complex with a hydroxamic acid inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312(4):743–751. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. L.. et al. A selective matrix metalloproteinase-12 inhibitor retards atherosclerotic plaque development in apolipoprotein E–knockout mice. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2011;31(3):528–535. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.219147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuti E.. et al. Sugar-Based Arylsulfonamide Carboxylates as Selective and Water-Soluble Matrix Metalloproteinase-12 Inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2016;11(15):1626–1637. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devel L.. et al. Simple pseudo-dipeptides with a P2′ glutamate: a novel inhibitor family of matrix metalloproteases and other metzincins. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(32):26647–26656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarivate . Cortellis Drug Discovery Intelligence. 2025. (accessed Feb 10, 2024); Available from: https://clarivate.com/life-sciences-healthcare/research-development/discovery-development/cortellis-pre-clinical-intelligence/.

- Tsoukalidou S.. et al. Exploration of zinc-binding groups for the design of inhibitors for the oxytocinase subfamily of M1 aminopeptidases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019;27(24):115177. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.115177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S., Ryde U.. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2015;10(5):449–461. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuccinardi T.. What is the current value of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods in drug discovery? Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2021;16(11):1233–1237. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2021.1942836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuti E.. et al. Development of thioaryl-based matrix metalloproteinase-12 inhibitors with alternative zinc-binding groups: synthesis, potentiometric, NMR, and crystallographic studies. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61(10):4421–4435. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puerta D. T., Lewis J. A., Cohen S. M.. New beginnings for matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors: identification of high-affinity zinc-binding groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126(27):8388–8389. doi: 10.1021/ja0485513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]