Structural posterior instability23 caused by glenoidal bone loss or excessive glenoidal retroversion requires the use of bone grafts.2,8 There are two main kinds of bone graft techniques in posterior shoulder instability. Free bone grafts can be fixed to the glenoid rim using screws, cerclages, or buttons.2,4,13 This technique enables augmentation or reconstruction of the posterior glenoid surface. Alternatively, shaped bone grafts can be incorporated into an osteotomy gap on the posterior scapular neck,26 which results in a correction of the glenoid's retroversion. One technique that allows reconstruction of the glenoid surface and at the same time change glenoid version is the so called J-bone graft that has been introduced by Herbert Resch,3,27 and extensively studied for anterior shoulder instability, but also recommended for use in posterior shoulder instability.27 Over the last decades, there has been a growing trend towards performing formerly open surgical techniques arthroscopically. This shift aims to minimize soft tissue damage, enhance visualization of the capsulolabral complex, and address co-pathologies.11,14,30 While the arthroscopic J-bone graft technique has been introduced for anterior shoulder instability by Werner Anderl,1 to our knowledge, no description of an arthroscopic posterior J bone graft has been published.

This technical note introduces the arthroscopic posterior J-bone graft technique that allows for implant-free reconstruction of the posterior glenoid surface and correction of excessive glenoid retroversion by means of osteotomy of the posterior scapula neck and press fit insertion of an autologous bicortical iliac crest bone graft shaped like the letter J.

Surgical technique

Indication and preoperative planning

Generally, the indication for an arthroscopic posterior J-bone graft can be made in cases of dynamic structural posterior shoulder instability (type B2)23 with posterior glenoid bone loss and/or excessive retroversion. It may also be indicated in patients with constitutional or acquired static posterior shoulder instability (type C1 and C2)23 to augment the posterior glenoid rim and correct excessive retroversion in an attempt to recenter the humeral head.

Patient positioning and operative set-up

Under general anesthesia, the patient is transferred into the lateral decubitus position. Standard prepping and draping of the shoulder and the ipsilateral iliac crest are carried out. After meticulous surgical field preparation, the arm is placed into a traction device to achieve lateral and longitudinal traction for improved intra-articular visualization.

Portals, arthroscopy, and glenoid preparation

The posterior portal is located slightly more caudally, and the incision is done horizontally. First, a diagnostic arthroscopy is carried out and showed no damage to the biceps tendon or the rotator cuff. After creating an anteroinferior working portal, the camera is then put into an anterosuperior viewing position to explore the posterior Bankart lesion, the glenoidal defect, and the reverse Hill–Sachs lesion. First, the posterior labrum is mobilized and outside-traction sutures are placed to create a posterior soft tissue pouch. The posterior glenoid rim is straightened with a burr. Subsequently, the posterior portal is extended horizontally and an arthroscopic J-bone-graft chisel with a width of 20 mm is brought into the joint with the help of a guiding slide and a flat trocar. A monocortical osteotomy is performed 5 mm medial to the glenoid rim, angled at 30° to the glenoid surface. Next, the second, slightly thicker chisel is used to widen the osteotomy carefully. Then, the distance between the glenoid articular surface and the osteotomy is measured with an arthroscopic ruler. The arthroscopic J-bone graft instruments are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Arthroscopic J-bone graft instruments: (1) guiding slide, (2) flat trocar, (3) 20 mm chisel thin wedge, (4) 20 mm chisel thick wedge, (5) trial implant, and (6) inserter.

Bone graft harvest and preparation

The graft is harvested from the ipsilateral iliac crest. An incision is made 5 cm dorsal of the anterosuperior iliac spine, then the muscle aponeurosis is carefully detached from the harvesting site. For the next step, a bicortical bone graft, including iliac crest and outer cortex, with the dimensions of 20 × 20 × 10 mm is harvested. The graft is then shaped into its J-form, by creating a 10--15-mm-long keel, using an oscillation saw, as shown in Figure 2. Later, the graft is fixated with two k-wires on the inserter.

Figure 2.

Measurements of the J-shaped iliac crest autograft.

Meanwhile, bone wax is placed into the donor site along with a hemostyptic sponge soaked with local anesthetic. The aponeurosis is closed side to side, as is the subcutaneous tissue. Skin closure is performed intracutaneously with resorbable sutures, and no wound drain is placed.

Graft insertion and fixation

After preparing the graft, the guiding slide is again inserted into the joint with the help of the flat trocar, and the osteotomy gap is widened again with the thinner chisel, followed by the thicker one. Then the graft, which was attached onto the inserter with two k-wires, is inserted into the joint using the guiding slide. The graft's keel is impacted into the osteotomy gap with gentle hammer strokes until the graft is fully seated into the posterior glenoid neck and the spongious part of the graft touches the posterior glenoid rim. Then the K-wires and the inserter are removed. To recreate the concavity of the glenoid, the surface of the graft is coplaned via a burr.

Finally the capsulolabral complex is fixed posteroinferiorly and posterosuperiorly to the native glenoid with knotless 1.8 mm Fibertaks (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA). A step-by-step documentation can be seen in Figure 3.

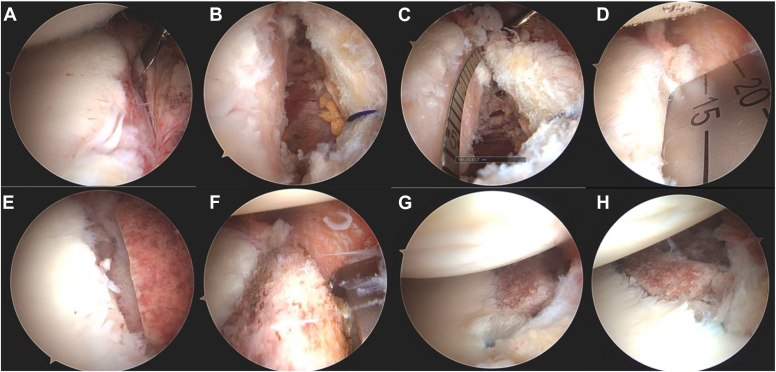

Figure 3.

(A) Posterior glenonidal defect before any manipulation, (B) posterior glenoidal defect after straightening with a burr, (C) distance measurement for the length of the graft's length, (D) creating a monocortical osteotomy with a 20 mm chisel, (E) and (F) insertion of the J-bone-graft, and (G) and (H) inserted graft and fixated labrum.

Rehabilitation

The postoperative care and rehabilitation treatment are shown in Table I. An external rotation brace is set to be worn for 6 weeks postoperatively. Passive movement, including flexion, abduction, and external rotation are allowed after the first week. Internal rotation should be avoided for a total of 4 weeks. Three months postoperatively, the patient can start with strength exercises.

Table I.

Rehabilitation and postoperative care.

| Time | Recommended ROM |

|---|---|

| Week 1-4 | Passive flexion 45° Passive abduction 45° Passive external rotation 30° No passive or active internal rotation |

| Week 5-6 | Passive flexion 90° Passive abduction 90° Passive external rotation until painful Passive internal rotation 30° |

| Week 7-8 | Active ROM without limitation |

ROM, range of motion.

The pearls and pitfalls are presented in Table II.

Table II.

Pearls and pitfalls.

| Pearls | Pitfalls |

|---|---|

| Shape the harvested bicortical graft slightly higher than shown by the template so that contouring of the slightly proud graft can be performed after insertion with a burr, thus anatomically reconstructing the glenoid concavity. | The posterior scapula neck is often curved and not as flat as the anterior neck. Thus, attention must be paid not to slip medially while performing the osteotomy. |

| Be aware that the final graft position should not be flush but congruent with the remainder of the concavity. | The plane of the osteotomy should be 30° angled to the articular surface in order to avoid fractures of the articular surface. |

| Refixation of the capsulolabral complex posteroinferiorly and posterosuperiorly to the graft can be performed with conventional soft tissue reconstruction anchors. | Neglecting the step-wise open wedge osteotomy with chisels of increasing aggressiveness elevates the risk of glenoid articular fracture. |

Case report

A dynamic posterior shoulder instability type B223 on the nondominant shoulder was diagnosed in a 28-year-old male patient. The first dislocation happened during a fall while breakdancing and resulted in up to 10 dislocations and countless subluxations, preventing the patient to carry out his work and sports.

Clinical examination showed a free range of motion (flexion 170°, abduction 170°, internal rotation to the thoracic vertebral level 12, and external rotation 60°). The patient had no signs of general hyperlaxity but was very apprehensive when testing for posterior instability with the Jerk, Kim, and O'Brien test. Preoperatively, a Western Ontario Shoulder Index15,18 of 43%, a subjective shoulder value12 of 40%, and a Rowe Score28 of 20 points were recorded.

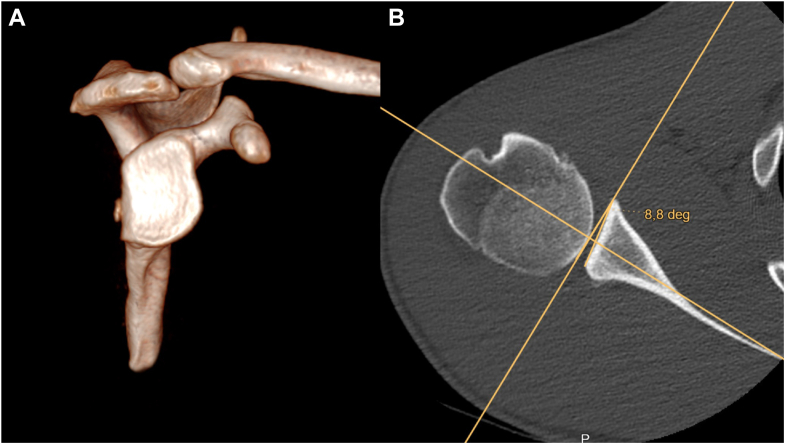

Computed tomography (CT) scans, shown in Figure 4, revealed a subcritical reverse Hill–Sachs lesion with a γ-angle22 of 83° and a critical posterior glenoid defect of 19% of the glenoid surface according to the Pico-method.5 The glenoid retroversion was 8.8°.7

Figure 4.

Preoperative imaging: (A) glenoidal retroversion, (B) osseos defect on 3D-CT scan. CT, computed tomography.

Due to the recurrent posterior instability episodes and critical bone loss situation with additionally increased retroversion of the glenoid, a shoulder stabilization procedure by means of an arthroscopic posterior J-bone graft was indicated.

Postoperative outcome

The patient received a CT scan 6 weeks after surgery. The images showed a gap-free fusion between the graft and the glenoid and a continuous restoration of the glenoid concavity (Fig. 5.)

Figure 5.

Postoperative imaging: (A) inserted J-bone graft on the dorsal glenoid, (B) slightly overcorrected glenoid version after J-bone-graft procedure.

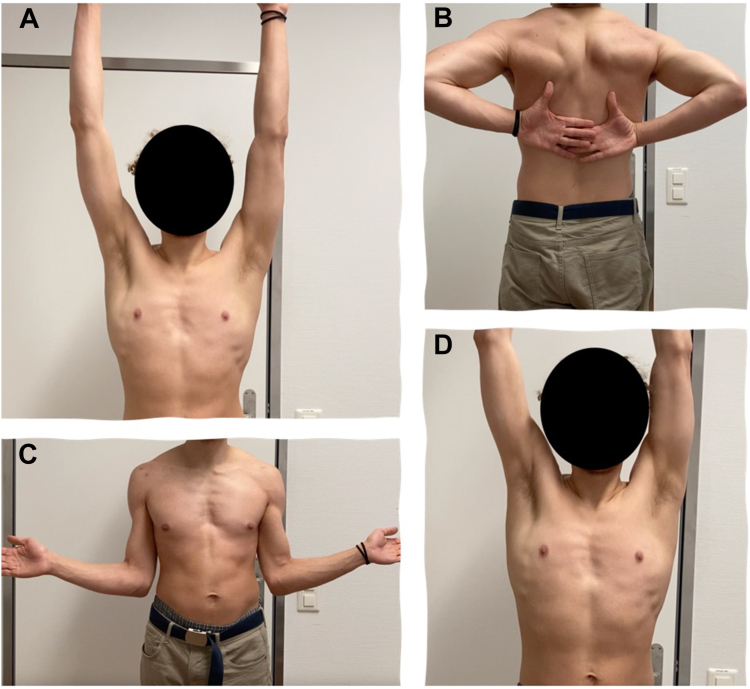

On the 1-year postoperative follow-up, the shoulder remained stable even during high-demand activities such as breakdancing, and the range of motion further improved to flexion 170°, abduction 170°, external rotation 80°, and internal rotation to the eighth thoracic vertebrae (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

ROM 1 year after surgery: (A) flexion, (B) internal rotation in neutral position, (C) external rotation, and (D) abduction. ROM, range of motion.

The Western Ontario Shoulder Index score improved to 90%, while the Rowe score increased to 95 points, and the subjective shoulder value reached 80%.

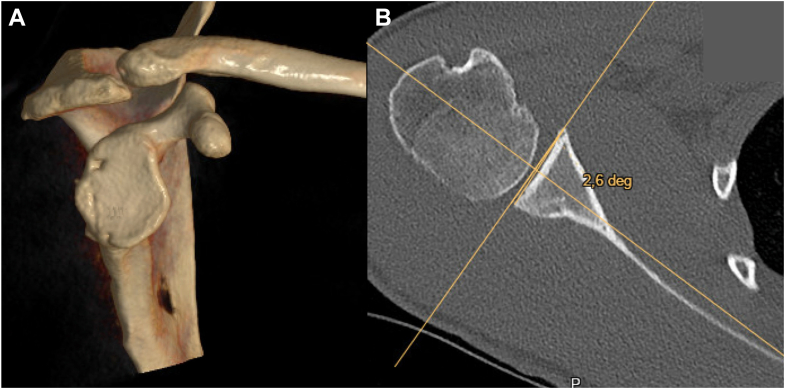

The follow-up CT scan showed optimal integration of the J-bone graft 1 year after the procedure, with remodeling leading to anatomical reconstruction of the glenoid articular surface and a physiological retroversion of 2.6° (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Computed tomography scan of the right shoulder joint 1 year postoperatively, (A) highlighting optimal integration and remodeling of the J-graft with (B) anatomical reconstruction of the glenoid articular surface.

Discussion

Over the last decades various techniques have been proposed for the surgical stabilization of posterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopic posterior capsulolabral reconstruction showed favorable outcomes.6,17 Bradley et al reported 297 cases of arthroscopic posterior capsulolabral repairs with a 6.4% rate of revision surgery.6 According to literature, the presence of bony glenoidal defects and excessive retroversion leads to an increased risk of failure of soft tissue-based stabilization procedures.2,9,13,16,25 Imhoff et al demonstrated in a cadaveric study that posterior labrum repair prevents posterior translation in a glenoid retroversion only up to 10°.16 Moreover Arner showed a 10-time higher risk of revision surgery when posterior glenoid bone loss of 11% is present.2 In those cases bone grafting is indicated. The usage of bone grafts always raises the question of the fixation technique. Screw fixation may result in projection due to graft remodeling.24,29 Notably, 80% of complications in posterior bone grafting stem from hardware complications.19 Alternative techniques utilizing Endobutton (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA, USA) or cerclage systems have been proposed.13 In 1988, Herbert Resch introduced the posterior J-bone graft procedure,27 an implant-free technique with glenoid osteotomy and press-fit insertion of a J-shaped graft to restore glenoid bone loss and pathological version. While utilized mainly for anterior stabilization, excellent clinical results proven in long-term and randomized controlled trials were reported.21,24 Radiologically, the J-bone graft was shown to be able to restore the glenoid concavity and version and even the cartilaginous surface of the joint20,21 with favorable biomechanical evaluation in the context of posterior shoulder instability.10

Werner Anderl was the first to describe the arthroscopic anterior J-bone graft technique and introduced the necessary instrumentation.1 We utilized this instrumentation to perform an arthroscopic posterior J-bone graft in a patient with structural posterior shoulder instability (type B2)23 with moderate bipolar bone loss and increased glenoid retroversion.

Through this technique, we simultaneously reconstructed the glenoid concavity and restored glenoid version in an implant-free fashion. The reverse Hill–Sachs defect was not treated in this case as the measured gamma angle was well below 90°, which according to biomechanical and clinical data, poses a low risk for engagement.22 Due to the ability to recreate the concavity and correct a retroverted glenoid in a similar manner to open-wedge osteotomies,26 we see a potential indication of the arthroscopic posterior J-bone graft technique in patients with static posterior shoulder instability type C as well.

It is important to acknowledge that there are inherent technical limitations in achieving a perfectly anatomical restoration of the posterior glenoid rim. However, similar to the principles observed in fracture treatment, bone tissue possesses a remarkable ability for remodeling and tends to revert to its original, most ergonomically efficient shape in response to varying levels of strain.20 Nonetheless, careful performance of the osteotomy and shaping of the graft must be accomplished in order to achieve a congruent graft contour and avoid proud or retrocessed graft placement. We recommend training the technique in an open fashion and to start with anterior J-bone graft procedures, as the posterior glenoid rim balcony-like shape makes the osteotomy more difficult than on the flatter anterior scapula neck.

Conclusion

The arthroscopic posterior J-bone graft technique presents a viable and effective option for patients suffering from posterior shoulder instability, particularly in the presence of posterior glenoid bone and increased retroversion. This anatomical and implant-free technique is able to restore joint stability and shoulder function.

Disclaimers:

Funding: This work was conducted independently and did not receive any financial or non-financial support.

Conflicts of interest: Philipp Moroder and Markus Scheibel are consultants for Arthrex that produces the instruments described in this technical note. The other authors, their immediate families, and any research foundation with which they are affiliated did not receive any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Footnotes

Institutional review board approval was not required for this technical note.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xrrt.2025.04.013.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Anderl W., Heuberer P.R., Pauzenberger L. Arthroscopic, implant-free bone-grafting for shoulder instability with glenoid bone loss. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2020;10:e0109.1–e0109.3. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.18.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arner J.W., Elrick B.P., Nolte P.-C., Goldenberg B., Dekker T.J., Millett P.J. Posterior glenoid augmentation with extra-articular iliac crest autograft for recurrent posterior shoulder instability. Arthrosc Tech. 2020;9:e1227–e1233. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auffarth A., Schauer J., Matis N., Kofler B., Hitzl W., Resch H. The J-bone graft for anatomical glenoid reconstruction in recurrent posttraumatic anterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:638–647. doi: 10.1177/0363546507309672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbier O., Ollat D., Marchaland J.-P., Versier G. Iliac bone-block autograft for posterior shoulder instability. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baudi P., Righi P., Bolognesi D., Rivetta S., Rossi Urtoler E., Guicciardi N., et al. How to identify and calculate glenoid bone deficit. Chir Organi Mov. 2005;90:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley J.P., Arner J.W., Jayakumar S., Vyas D. Risk factors and outcomes of revision arthroscopic posterior shoulder capsulolabral repair. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:2457–2465. doi: 10.1177/0363546518785893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Bunt F., Pearl M.L., Lee E.K., Peng L., Didomenico P. Glenoid version by CT scan: an analysis of clinical measurement error and introduction of a protocol to reduce variability. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:1627–1635. doi: 10.1007/s00256-015-2207-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cognetti D.J., Hughes J.D., Kay J., Chasteen J., Fox M.A., Hartzler R.U., et al. Bone block augmentation of the posterior glenoid for recurrent posterior shoulder instability is associated with high rates of clinical failure: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2022;38:551–563.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichinger J.K., Galvin J.W., Grassbaugh J.A., Parada S.A., Li X. Glenoid dysplasia: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:958–968. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernstbrunner L., Borbas P., Ker A.M., Imhoff F.B., Bachmann E., Snedeker J.G., et al. Biomechanical analysis of posterior open-wedge osteotomy and glenoid concavity reconstruction using an implant-free, J-shaped iliac crest bone graft. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50:3889–3896. doi: 10.1177/03635465221128918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank R.M., Romeo A.A., Provencher M.T. Posterior glenohumeral instability: evidence-based treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:610–623. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbart M.K., Gerber C. Comparison of the subjective shoulder value and the constant score. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:717–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hachem A., Molina-Creixell A., Rius X., Rodriguez-Bascones K., Cabo Cabo F.J., Agulló J.L., et al. Comprehensive management of posterior shoulder instability: diagnosis, indications, and technique for arthroscopic bone block augmentation. EFORT Open Rev. 2022;7:576–586. doi: 10.1530/EOR-22-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hachem A.-I., Rondanelli S.R., Costa D.’O.G., Verdalet I., Rius X. Arthroscopic “bone block cerclage” technique for posterior shoulder instability. Arthrosc Tech. 2020;9:e1171–e1180. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofstaetter J.G., Hanslik-Schnabel B., Hofstaetter S.G., Wurnig C., Huber W. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the German version of the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability index. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:787–796. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-1033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imhoff F.B., Camenzind R.S., Obopilwe E., Cote M.P., Mehl J., Beitzel K., et al. Glenoid retroversion is an important factor for humeral head centration and the biomechanics of posterior shoulder stability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:3952–3961. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karpinski K., Akgün D., Gebauer H., Festbaum C., Lacheta L., Thiele K., et al. Arthroscopic posterior capsulolabral repair with suture-first versus anchor-first technique in patients with posterior shoulder instability (type B2): clinical midterm follow-up. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11 doi: 10.1177/23259671221146167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkley A., Griffin S., McLintock H., Ng L. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability. The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI) Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:764–772. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260060501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mojica E.S., Schwartz L.B., Hurley E.T., Gonzalez-Lomas G., Campbell K.A., Jazrawi L.M. Posterior glenoid bone block transfer for posterior shoulder instability: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:2904–2909. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moroder P., Hirzinger C., Lederer S., Matis N., Hitzl W., Tauber M., et al. Restoration of anterior glenoid bone defects in posttraumatic recurrent anterior shoulder instability using the J-bone graft shows anatomic graft remodeling. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1544–1550. doi: 10.1177/0363546512446681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moroder P., Hitzl W., Tauber M., Hoffelner T., Resch H., Auffarth A. Effect of anatomic bone grafting in post-traumatic recurrent anterior shoulder instability on glenoid morphology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1522–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moroder P., Runer A., Kraemer M., Fierlbeck J., Niederberger A., Cotofana S., et al. Influence of defect size and localization on the engagement of reverse Hill-Sachs lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:542–548. doi: 10.1177/0363546514561747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moroder P., Scheibel M. ABC classification of posterior shoulder instability. Obere Extrem. 2017;12:66–74. doi: 10.1007/s11678-017-0404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moroder P., Schulz E., Wierer G., Auffarth A., Habermeyer P., Resch H., et al. Neer Award 2019: Latarjet procedure vs. iliac crest bone graft transfer for treatment of anterior shoulder instability with glenoid bone loss: a prospective randomized trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nacca C., Gil J.A., Badida R., Crisco J.J., Owens B.D. Critical glenoid bone loss in posterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:1058–1063. doi: 10.1177/0363546518758015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pogorzelski J., Braun S., Imhoff A.B., Beitzel K. [Open-wedge osteotomy of the glenoid for treatment of posterior shoulder instability with increased glenoid retroversion] Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2016;28:438–448. doi: 10.1007/s00064-016-0457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resch H., Kadletz R. 1988. Praktische Chirurgie des Schultergelenkes. Innsbruck: Frohnweiler. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowe C.R., Patel D., Southmayd W.W. The Bankart procedure: a long-term end-result study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Spanning S.H., Picard K., Buijze G.A., Themessl A., Lafosse L., Lafosse T. Arthroscopic bone block procedure for posterior shoulder instability: updated surgical technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11:e1793–e1799. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2022.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf E.M., Eakin C.L. Arthroscopic capsular plication for posterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.