Abstract

Background

Early detection of colorectal cancer (CRC) is crucial for improving patient survival. This innovative multi-center study aims to develop a non-invasive blood-based assay using cell-free DNA (cfDNA) fragmentomics to differentiate CRC from advanced colorectal adenomas and non-cancerous colorectal and other digestive diseases.

Methods

A total of 167 CRC patients and 227 with benign colorectal conditions were divided into training and validation cohorts (1:1 ratio). Plasma cfDNA underwent Low-depth whole-genome sequencing to profile three fragmentomics features, which were integrated into a stacked ensemble model. The model was validated on 69 CRC patients and 96 benign controls, with an additional cohort of 31 advanced adenoma patients included to assess its performance in differentiating advanced adenomas from benign cases.

Results

The model achieved an AUC of 0.926, with sensitivity of 91.3% and specificity of 82.3% in validation. Sensitivities were consistently high across CRC stages (I: 94.4%, II: 86.4%, III: 91.3%, IV: 100%). Notably, the model demonstrated exceptional accuracy in distinguishing advanced adenomas from benign cases, achieving an AUC of 0.846 and sensitivity of 67.7%, outperforming traditional blood tests.

Conclusions

This multi-center study underscores a significant advancement in liquid biopsy technology, offering a highly accurate and non-invasive approach for early CRC detection and differentiation of advanced colorectal adenomas.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12935-025-03967-9.

Keywords: Cell-free DNA fragmentomics, Colorectal cancer, Advanced colorectal adenoma, Early- detection, Liquid biopsy

Introduction

The increasing incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in developing countries has gathered significant attention within the medical field. Due to the rapid aging of the population and lifestyle changes across a wide demographic base, China takes a large proportion of new CRC cases and faces the social and economic burdens associated with deaths caused by CRC [1, 2]. The 5-year Survival rate of CRC is strongly dependent on the tumor stage at the time of diagnosis, showing a significant decrease from over 90% for stage I to around 10% for stage IV [3]. Consequently, early-detection of CRC has become a major concern to enhance the prognosis and the survival rate of CRC patients.

Most sporadic cases of CRC originate from non-cancerous colorectal polyps, which are typically discovered incidentally during routine colonoscopy examinations [4, 5]. Advanced colorectal adenomas (advCRA) are considered direct precancerous lesions of CRC, and early identification and removal of advCRA can significantly control its progression to malignancy, thus improving CRC prevention [6]. While colonoscopy is widely regarded as the gold standard for CRC detection, its invasive nature, potential discomfort, and risk of bleeding can deter patients from regular colonoscopy screening [7].

Researchers are continuously working to find a noninvasive way to detect CRC with high accuracy. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 are the newly developed serum biomarker tests widely used for organ cancer detection. Unfortunately, the real-world use of these two markers cannot be guaranteed due to low sensitivity towards single-organ cancers. According to Sekiguchi and Matsuda, sensitivities of CEA and CA19-9 in detecting colorectal cancer were around 10% [8]. Stool-based DNA tests, such as the Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) and the Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT), along with blood-based tests, have shown strength in detecting CRC. However, their sensitivities vary and there remains great potential for optimization. A prospective study from Thomas and colleagues illustrated the predictive power of a next generation multitarget stool DNA test. While their method showed Substantial improvement over FIT results, the sensitivity for advCRA was still less than 50% (43.3%) [9]. The sensitivity for advCRA detection based on blood tests was found to be lower in a prior study. According to Church and colleagues, a blood test based on methylated SEPT9DNA provided sensitivities for CRC and advCRA at 48.2% and 11.2%, respectively [10]. Another study conducted by Daniel et al. also demonstrated a sensitivity of only 13.2% for advCRA through blood-based DNA tests [11].

Recently, liquid biopsy approaches based on cell-free DNA (cfDNA) were suggested to start a new revolution in detecting disease. Fragmentomics of cfDNA were proved to contain a wealth of distinct genetic information, such as size, distribution, and end motifs, which exhibited promising potential in differentiating cancer and noncancer cells [12, 13]. This non-invasive and cost-effective approach has demonstrated effectiveness in the early detection of cancer in several previous studies. For example, a study by Yuan et.al showed the high accuracy of utilizing cfDNA biomarker to detect esophageal cancer, achieving 93.75% sensitivity and 85.71% specificity, with a corresponding Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.972 [14]. Using the fragmentation information of cfDNA, Cristiano and colleagues obtained a highly sensitive detection among seven types of cancer, with an overall AUC value of 0.94. Additionally, they also showed a 91% sensitivity for cancer detection by combining this approach with a mutation-based cfDNA method [15]. Chen et al. validated the effectiveness of integrating copy number variation profiles into robust machine learning models. Their developed model showed an overall high predictive accuracy of 0.89, in distinguishing malignant from nonmalignant ovarian tumors [16].

Multiple liquid biopsy assays for CRC screening have entered clinical use or undergone large-scale validation. The FDA-approved Epi proColon test, based on methylated SEPT9, offers a blood-based alternative to stool tests, though with limited sensitivity for early-stage disease. Cologuard, a multitarget stool DNA test also approved by the FDA, shows improved sensitivity over FIT for CRC but remains suboptimal for advanced adenomas. More recently, newer blood-based cfDNA assays, such as Shield (Guardant Health) and ColoSense (Freenome), have been prospectively evaluated in average-risk, screening-intended populations. These tests apply multi-omic or fragmentomics-based machine learning approaches and report sensitivities exceeding 80% for CRC, though sensitivities for advCRA detection remain modest and vary across platforms. The need for further improvement in detecting both CRC and high-risk adenomas in clinically relevant populations remains a major drive for innovation in this field.

To enhance the CRC detection in clinical diagnosis and ensure the generalizability of current methods, we conducted a multi-center study DECIPHER- D- Colon. In this study, our target is to integrate cfDNA fragmentomics features into machine learning algorithms, producing a non-invasive method for accurately distinguishing CRC patients among patients with colorectal disease. In contrast to other previous studies that typically compared healthy controls with cancer patients, our research marks a significant advancement by achieving an impressive sensitivity in distinguishing between CRC patients and individuals with non-cancerous colorectal and other digestive diseases. Based on cfDNA fragmentomics extracted from blood test results, we developed a multidimensional machine learning model that produces high sensitivity for detecting CRC and advCRA. This model aims to improve CRC prevention strategies and patients’ survival rate under clinical settings.

Methods

Patients enrollment and sample preparation

The participants were enrolled between October 2021 and September 2023, from four different hospitals: Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, and General Hospital of Eastern Military Command (Jinling Hospital). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (Protocol No. KY-Q-2022-255-0). The approved protocol included provisions for the retrospective inclusion of samples collected prior to the approval date to Support recruitment for rare disease Subgroups. The training cohort consisted of 229 patients, including 98 with CRC and 131 with non-cancerous diseases including benign adenoma, non-cancerous colorectal diseases, and other non-cancerous digestive diseases. Specifically, to achieve a more accurate and unbiased result, patients with any of the conditions described in Fig.1B were excluded. Furthermore, we also established an independent cohort for validation purposes, and the exclusion criteria remained the same. 165 patients in total were randomly assigned to the validation cohort in a 1:1 ratio (CRC, n = 69 and non-cancerous colorectal disease, n = 96). Participants included CRC patients from all stages (stage I-IV). An additional cohort was created for a more convincing validation, including 31 participants with advanced colorectal adenoma (advCRA) (n = 31, 14 large adenoma, 10 villous lesion, 7 in situ cases). All patients provided written consents for participating in this study.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of Overall Study Design and Colorectal Cancer Early Detection Process (A) All plasma samples from CRC patients and from patients with benign colorectal diseases were collected and underwent whole genome sequencing process and bioinformatics analysis. Three cfDNA features were used in this study: Copy Number Variation (CNV), Arm-level Fragment Size Distribution (ARM-FSD), and Mutation Context and Mutational Signature (MCMS).(B) 235 participants were included in the training cohort and 166 participants were included in the validation cohort. According to exclusion criteria and quality control, the qualified patients’ data for further analysis was: Training cohort (98 CRC and 131 disease); Validation cohort (69 CRC and 96 disease)

Participants were eligible for inclusion in the study if they met the following criteria:

Aged ≥ 18 years.

Diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) or benign colorectal disease.

Provided written informed consent.

Able to provide a peripheral blood sample for cfDNA extraction.

Enrolled at one of the designated study centers during the recruitment period (October 2021 to September 2023).

Participants were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria:

History of any cancer therapy prior to sample collection.

Diagnosed with a non-colorectal malignancy.

Blood sample failed sequencing quality control (for the validation cohort only).

Additionally, to evaluate the assay’s ability to identify healthy individuals without colorectal or other digestive diseases, we retrospectively collected plasma samples from 50 healthy individuals and 50 CRC patients through the biobank of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital. These samples were collected in accordance with ethical regulations, and their retrospective use was permitted under the same IRB-approved protocol (KY-Q-2022-255-0). All healthy individuals met the following inclusion criteria:

Aged ≥ 18 years.

No prior cancer history.

No known history of colorectal polyps, inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), or other gastrointestinal diseases.

No evidence of colorectal or other digestive diseases through standardized health screenings at the time of blood sample collection.

Provided written informed consent.

Diagnostic criteria

All participants underwent diagnostic colonoscopy. For colorectal cancer (CRC) and adenomatous lesions, diagnosis was confirmed by histopathological examination of biopsy, endoscopic resection, or surgical specimens. CRC was defined by the presence of malignant epithelial cells invading through the basement membrane into the submucosa or beyond. All CRC diagnoses were reviewed by experienced gastrointestinal pathologists.

Benign adenomas, such as tubular adenomas and hyperplastic polyps, were also pathologically confirmed. These lesions were characterized by dysplastic epithelium without stromal invasion. In cases where the distinction between high-grade dysplasia and early invasive carcinoma was uncertain, diagnoses were finalized by consensus among expert pathologists, and only clearly defined cases were included.

For non-neoplastic conditions - such as Crohn’s disease, enteritis, or other gastrointestinal disorders - diagnoses were based on clinical evaluation, endoscopic appearance, imaging, and laboratory findings. Biopsies were performed when indicated, particularly in cases of suspected inflammatory bowel disease or mucosal abnormalities. Extra-colonic conditions like gastritis or cholecystitis were diagnosed according to standard clinical protocols, with pathological confirmation available in cases where tissue samples were obtained.

Low-pass WGS procedure

For both CRC patients and disease controls, each participant provided ∼ 10mL peripheral blood before undergoing other colorectal cancer screening tests, and the samples were then stored in EDTA tubes and processed to isolate plasma within 4 hours. Subsequently, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) extraction was performed within a 72-hour window, after which the material was preserved at a temperature of −80 ◦C to ensure optimal conditions for the following sequencing processes. The plasma samples collected were shipped to the laboratory for further processing and sequencing (Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc., China). Extraction of cfDNA was performed using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, Germany), and the cfDNA concentration was measured by the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Then cfDNA libraries for whole-genome sequencing (WGS) were prepared using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (KAPA Biosystems, USA). Briefly, each sample containing 5-10 ng of plasma cfDNA underwent a series of sequential steps, including end-repairing, A-tailing, and adaptor ligation, which ensured a thorough sequencing library construction. The cfDNA whole genome sequencing was conducted on the Illumina NovaSeq platform with paired end 150bp reads (PE150), yielding an average coverage depth of 7.96X. The resulting WGS data were further downsampled to a uniform 5X for consistent downstream analyses. The additional 31 plasma samples from advCRA patients in the external validation cohort processed and sequenced following the same protocols in the same laboratory.

Bioinformatic analysis and model construction

We constructed a two-layer machine learning classification model to enhance the accuracy and robustness of identifying CRC from advanced colorectal adenomas and non-cancerous colorectal and other digestive diseases. The following fragmentomics features were utilized as the input matrix in the first layer: Copy Number Variation (CNV), ARM-level Fragment Size Distribution (ARM-FSD), and Mutation Context and Mutational Signature (MCMS). A detailed description of these fragmentomics features can be accessed through the online supplementary document. Concisely, the profiling of CNV was based on the study by Wan and colleagues [17], we calculated the log2 ratio for each 1Mb genome segment. ARM-FSD feature was referred to Su et.al [18], exploring the cfDNA fragment size distribution at the chromosomal arm level with more length information kept. For analysis of MCMS, we employed the method proposed by Wan et al. [19] and improved it with modifications on SNP and background noise removal. The total number of selected raw features was 3,586, distributed as follows: 2,475 for CNV, 936 for ARM-FSD, and 175 for MCMS.

Copy number variations (CNVs) are a form of genetic variation characterized by changes in the number of copies of specific genomic regions. In this study, CNV profiles were generated using ichorCNA. Each genome was segmented into 1 Mb bins, followed by GC correction to minimize sequencing bias in read depth. A Hidden Markov Model (HMM) was then applied to analyze the depth of coverage for each bin, comparing it to a baseline derived from a whole-genome sequencing (WGS) dataset of healthy individuals, as described by Adalsteinsson et al. This comparison yielded log2 ratios for each bin, representing relative copy number changes. These log2 ratios were used as CNV features, resulting in a total of 2,475 variables per sample, providing a comprehensive representation of the CNV landscape.

Fragment size distribution analysis focused on the length profiles of circulating cfDNA fragments. Fragment sizes were binned in 5 bp intervals from 100 bp to 220 bp (e.g., 100–104 bp, 105–109 bp). The ratio of fragment counts in each bin was calculated at the chromosome arm level for human autosomes. Raw coverage scores were normalized using z-score transformation, computed by comparing the value of each bin to the mean value across the corresponding chromosome arm. This approach yielded 936 variables representing fragment size distribution features.

Mutational signatures reflect the influence of various mutagenic processes on somatic mutations in cancer genomes. We followed the analytical framework developed by Wan et al., incorporating additional steps for enhanced single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and background noise filtering to improve accuracy. Following variant calling, we filtered mutations using data from dbSNP, the East Asian population Subset of the 1000 Genomes Project, and an internal reference panel comprising 1,000 healthy individuals. Variants present in these databases or recurrent more than three times within a sequencing run were excluded to minimize the impact of germline mutations and technical artifacts.

Subsequently, single-base substitutions (SBS) were classified into six types—C>A, C>G, C>T, T>A, T>C, and T>G—based on the pyrimidine context of the mutated base. The bases immediately flanking the SBS at the 5′ and 3′ positions were also considered, resulting in 96 possible trinucleotide contexts (6 Substitution types × 4 upstream bases × 4 downstream bases). Mutation counts for each of these 96 contexts were extracted from WGS data and corrected for GC content. These context profiles were then normalized by Subtracting a mutational baseline established from 3,000 independent healthy controls, processed with identical filtering methods.

Mutational signature fitting was performed using the fit_to_signature() function from the MutationalPatterns R package (v1.10.0), which uses non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to estimate the contribution of known signatures to each sample’s mutation profile. Signatures known to reflect oxidative damage or sequencing artifacts, as annotated in the COSMIC (Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer) database, were excluded. Importantly, both the SNP reference databases and the baseline control group used to define the mutational context were entirely independent of the cohorts analyzed in this study.

We employed a variety of machine learning models, including Distributed Random Forest (DRF), Extremely Randomized Trees (XRT), Generalized Linear Model (GLM), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and Deep Learning (DL). A grid search was performed, iterating various candidate values for each algorithm while training them multiple times. Thus, 1,200 meta-models were trained in the initial layer, each producing an Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) score to demonstrate their classification performance across cancer and disease groups. The second layer was built on the optimal models generated from the cross-validation process in the training cohort, with the highest two AUC performance scores for each feature. The models were then further integrated using a generalized linear algorithm and mean ensemble to obtain the final stacked model. The model training process was executed solely within the designated training cohort, and the performance was evaluated through a 5-fold cross-validation, ensuring that the validation cohort was kept separate and untouched until the final model was completed. This approach allowed for a robust and unbiased evaluation of the model’s performance before its finalization.

Feature importance analysis using SHAP values

To interpret the contribution of each cfDNA feature to the model’s predictions, we performed feature importance analysis using SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values. SHAP is a unified framework based on cooperative game theory that quantifies the marginal contribution of each feature to the model’s output while accounting for feature interactions and dependencies.

SHAP values were computed using the TreeExplainer method from the SHAP Python library (v0.48.0), which is optimized for tree-based models. For our ensemble classifier, we applied SHAP to the final trained model using the validation dataset as input. Each SHAP value represents the estimated impact of a given feature on the predicted probability of colorectal cancer (CRC) or advanced colorectal adenoma (advCRA) for a specific sample.

To assess global feature importance, we calculated the mean absolute SHAP value for each feature across all samples. Features with the highest average SHAP values were considered the most influential in driving model predictions.

Statistical analysis

The machine learning modelling and validating process was performed through “h2o” package in Python. All statistical analyses were conducted within the R environment (v.4.1.2). The plotting of ROC curves and the calculations of AUCs were completed through the pROC package (v.1.18.0). Based on true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), false negative (FN), the sensitivity [TP/(TP+FN)], specificity [TN/(TN+FP)], accuracy [(TP+TN)/(TP+FP+TN+FN)], and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the “DeLong” method with the epiR package (v.2.0.74). The matched cohort used for the supplementary validation was generated from the MatchIt package (v.4.5.3). All comparisons between continuous data were done by Wilcoxon Test.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

In this study, a total of 394 participants were recruited from four different hospitals between October 2021 and September 2023. These samples were randomly assigned to the training and validation cohorts at an approximately 1:1 ratio (Fig. 1B). The training cohort included 98 CRC patients as the cancer group and 131 patients with benign colorectal disease as the control group. Diseases in the control group included benign adenoma (Tubular adenoma and colon polyps), non-cancerous colorectal diseases (Enteritis, Crohn’s disease, etc.) and other digestive diseases (Gastrointestinal bleed, cholecystitis, gastritis, etc.). In the training cohort, the disease controls included 44 cases of benign adenoma, 34 cases of colorectal disease, and 53 cases of other digestive diseases. 69 CRC participants and 96 disease controls (40 benign adenoma, 23 non-cancerous colorectal diseases and 33 other digestive diseases) were enrolled to form an independent validation cohort, and it remained untouched until the model was finalized. It should be noted that the samples were independently collected from 5 departments across 4 distinct hospitals. The multi-center trials enhanced the model’s ability to produce more generalized results. Additionally, 31 advanced Colorectal Adenoma (advCRA) samples were collected, with 7 in situ cases included to form an external validation cohort and test the model’s predictive stability in diagnosing malignant colorectal diseases.

Patients’ demographic and clinical information are depicted in Supplementary Table S1-S2. We collected patient information from individuals of both sexes spanning a wide age range to ensure the comprehensiveness of the model. The mean age of patients with CRC was 61 years old [16-92] among 43 males (43.8%) and 55 females (56.1%) in the training group, and 60 years old [22-93] among 41 males (59.4%) and 28 females (40.5%) in the validation group. For the disease control, the mean age of patients was 55 years old [16-92] (67.1% males and 32.8% females) and 57 years old [17-95] (63.5% males and 36.4% females) for training and validation cohorts, respectively. The distribution of cancer stages I, II, and III was relatively balanced between the training and validation samples, with each stage representing approximately 30% of the cohort.

Model performance

Final model performance

To build the final stacked model, we first trained six machine learning algorithms (DRF, XRT, GLM, XGBoost, GBM, DL; Methods) on each of the three cfDNA feature types (CNV, ARM-FSD, and MCMS) (Table S3). For each feature type, the two models with the highest AUCs were selected as base learners. These top-performing base models were combined to construct the final stacked model (Fig. 1A). In the training cohort, the optimal base model on each feature produced AUCs within a range from 0.7800 to 0.9063, reinforcing the predictive power of the finalized model (Fig. 2A). The final developed model exhibited a strong predictive ability of CRC, achieving an AUC of 0.9295 in the training group, and 0.9258 in the independent validation group (Fig. 2B). To improve the accuracy of CRC diagnosis in the clinical setting, a cut-off value of 0.3385 was determined. This value ensures a high predicted sensitivity of 90% for detecting CRC. As shown in Table 1. with this cut-off, the constructed model facilitated a higher sensitivity of 91.84% (90/98) and specificity of 78.63% (103/131). The model application on the validation cohort demonstrated a similar result with the sensitivity and specificity of 91.30% (63/69) and 82.29% (79/96), respectively. The model showed superior performance in distinguishing CRC and advanced colorectal adenomas and non-cancerous colorectal and other digestive diseases. CRC samples showed significantly higher prediction scores than those of control disease samples in both training and validation cohorts (Fig 2C).

Fig. 2.

The Performance of Final Stacked Ensemble Model. (A) Training ROC curve of the stacked ensemble model based on three features (CNV, ARM-FSD, MCMS), with comparison to ROC curves of three base models. (B) Validation ROC curve of the stacked ensemble model based on three features (CNV, ARM-FSD, MCMS), with comparison to ROC curves of three base models. (C) Boxplots depicting the scores of CRC patients and disease control patients predicted by the stacked ensemble model in training and validation cohorts, with a specified cut-off at 0.3385. (D) Dotted boxplots of the sensitivities calculated from the final model’s prediction results, with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (line expansions from the dots) across four colorectal cancer stages (stage I, II, III, and IV)

Table 1.

Diagnostic Performance of the Stacked Ensemble Model in Training and Validation Cohorts

| Disease control vs.CRC (Training) | Actual | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC | Disease | ||||

| Predict | CRC | 90 | 28 | ||

| Disease | 8 | 103 | |||

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 91.84%(84.55%−96.41%) | ||||

| Specificity (95%CI) | 78.63% (70.61% - 85.30%) | ||||

| PPV (95%CI) | 76.27% (67.56% - 83.62%) | ||||

| NPV (95%CI) | 92.79% (86.29% - 96.84%) | ||||

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 84.28% (78.91% - 88.74%) | ||||

| Disease control vs. CRC (Validation) | Actual | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC | Disease | ||||

| Predict | CRC | 63 | 17 | ||

| Disease | 6 | 79 | |||

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 91.30% (82.03% - 96.74%) | ||||

| Specificity (95%CI) | 82.29% (73.17% - 89.33%) | ||||

| PPV (95%CI) | 78.75% (68.17% - 87.11%) | ||||

| NPV (95%CI) | 92.94% (85.27% - 97.37%) | ||||

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 86.06% (79.82% - 90.95%) | ||||

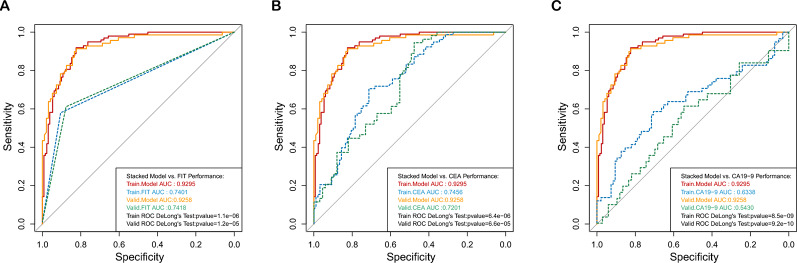

We compared our cfDNA-based assay with traditional biomarkers including FIT, CEA, and CA19-9. In the training cohort, our cfDNA-based model achieved an AUC of 0.9295, which was significantly higher than those of FIT, CEA, and CA19-9 tests (0.7401, 0.7456, and 0.6338, respectively) with respective P values from DeLong’s tests of 5.3X10−6, 2.8X10−6, and 3.0X10−9. Similar trends were observed in the validation cohort, where our model continued to demonstrate Superior performance. The AUC differences remained statistically significant with P values of 1.9X10−6, 8.3X10−6, and 4.5X10−9, respectively (Figure 3A–B). Furthermore, in the separate testing set, our assay correctly identified 48 out of 50 healthy individuals and 46 out of 50 CRC patients (Table S4). We further combined the cfDNA-based assay with CEA and CA19-9 tests using Logistic regression. The combined model showed improved performance with an AUC metric of 0.9646 (95%CI: 0.9390-0.9902) in the training cohort and 0.9562 (95%CI: 0.9178-0.9947) in the validation cohort (Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

Performance Comparison of the Stacked Ensemble Model with Traditional Screening Tests ROC curves of the stacked ensemble model in training and validation cohorts based on patients’ test results from three traditional screening methods, compared with (A)Training and validation ROC curves based on patients’ FIT results. (B)Training and validation ROC curves based on patients’ CEA results.(C) Training and validation ROC curves based on patients’ CA19-9 results

Model robustness evaluation in subgroup analysis

The stability of this model was confirmed through various subgroup analyses. According to Fig. 2D, our model’s sensitivity for CRC stage I, II, III was 88.0% (95% CI, 0.688-0.975), 87.9% (95% CI, 0.718-0.966) and 97.0% (95% CI, 0.842-0.999) respectively, and reached 100% for stage IV CRC. This result was corroborated by the validation cohort, with sensitivity for stage I CRC achieving an impressive 94.4% (95% CI, 0.727-0.999), confirming that the model effectively identified patients in all stages of cancer (stage II: 86.4%; III: 91.3%, IV: 100.0%). Although the 95% sensitivity CI for stage IV CRC was wide due to a small sample size, the overall performance of our model remained outstanding for both study cohorts. The stacked model demonstrated superior sensitivities across all cancer stages (I to IV), and a clear increase in sensitivity was observed from early to late CRC stages. Other subgroup analysis results based on tumor locations, and traditional blood tests are specified in the supplementary document.

A matching process was employed for the dataset to ensure a more robust and unbiased assessment of the treatment effect. Given the imbalance in sex distribution across cohorts, we applied propensity score matching based on demographic variables (age and sex). Following matching, AUCs were recalculated using the matched Sub-cohorts. This process yielded 62 CRC and 58 non-cancerous disease samples in the training cohort, and 43 CRC and 42 non-cancerous disease samples in the validation cohort. The matched Sub-cohorts maintained excellent discriminatory performance between CRC and non-cancerous colorectal diseases, with AUCs of 0.929 for the training cohort and 0.936 for the validation cohort (Fig. S2). The results suggest that age and sex had minimal influence on the model’s performance in this study.

We also compared model performance under different types of subgroups. Based on patients’ data of different CRC stages, the predicted risk scores differed. The result proved that the median score was relatively lower in early-stage patients (I/II), compared to those in later stages (III/IV) for both training and validation groups (Fig. S3). Test results from all three tumor locations and biomarker methods have little effect on CRC risk scores. Risk scores obtained from both the left and right hemi colon, as well as the rectum, showed no significant difference (Fig. S4). However, higher sensitivities were yielded for right colon tumors for both groups, with a remarkable 100% sensitivity in the training cohort. Although patients who tested positive for CEA and CA19-9 revealed slightly higher scores, the differences between positive and negative patients were not statistically significant for both cohorts (Fig. S5).

We assessed mismatch repair (MMR) status for all CRC cases and examined its correlation with prediction scores from our cfDNA-based assay. Notably, patients with proficient MMR (pMMR) status exhibited significantly higher cfDNA scores compared to those with deficient MMR (dMMR) status in both the training and validation cohorts (Fig. S6).Among 12 samples of stage IV CRC, those with liver metastases (n = 5) showed higher prediction scores than those with lymph node involvement (n = 3) (mean: 0.8251 vs. 0.6543). The single sample with lung metastasis had a score of 0.8464, similar to those of liver metastases. These differences may reflect variations in circulating tumor burden or biological aggressiveness associated with different metastatic sites (Fig. S7).

Feature variables for model prediction

We performed comparative analyses of the three cfDNA feature types across three participant groups: healthy individuals, colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, and individuals with non-cancerous colorectal or digestive diseases (Fig. S8). These analyses aimed to assess the biological relevance and discriminatory power of each feature type, thereby supporting their inclusion in the predictive model.

Healthy individuals exhibited a relatively uniform and expected cfDNA fragment length distribution, with a predominant peak around 167 bp, consistent with nucleosomal protection during apoptosis. In contrast, CRC samples showed an increase in the proportion of short fragments (<150 bp), particularly in genomic regions associated with cancer-related chromatin accessibility. This trend was observed to a lesser extent in patients with non-cancerous diseases, suggesting that increased fragmentation is more specific to malignant processes (Fig. S8A). The enrichment of short fragments in CRC likely reflects increased apoptosis, necrosis, and chromatin remodeling activity associated with tumor biology.

Compared to healthy individuals, CRC patients displayed markedly higher genome-wide CNV signal variability, indicative of chromosomal instability. Frequent amplifications and deletions were observed in chromosomal regions known to be altered in CRC, Such as gains on 8q, 20q, and Losses on 18q. Non-cancerous disease samples showed minimal CNV signal fluctuation, reinforcing the specificity of this feature class to malignant conditions (Fig. S8B). These differences underscore the value of CNV profiling in capturing tumor-associated genomic instability from circulating cfDNA.

CRC samples showed significantly elevated counts of single base substitution (SBS) signatures, SBS6, SBS13, SBS18, SBS44, and SBS45, which have known associations with colorectal tumorigenesis, compared to both healthy individuals and patients with non-cancerous diseases (Fig. S8C). The distinct enrichment of these mutational signatures in CRC patients underscores the presence of tumor-specific mutational processes detectable in cfDNA. In contrast, healthy controls and non-cancerous disease participants exhibited minimal counts of these signatures, reinforcing their specificity for malignancy.

Together, these results demonstrate that the integrated use of cfDNA fragmentation patterns, CNV signals, and well-characterized mutational signatures provides a biologically grounded and complementary feature set for colorectal cancer detection. Supplementary Figure S6 illustrates the group-wise differences in each feature type and confirms their collective utility in distinguishing CRC from non-cancerous states.

Model prediction in advCRA detection

Furthermore, this study denoted a huge enhancement in distinguishing not only between benign colorectal diseases and colorectal cancer but also succeeded in identifying serious precancerous conditions such as advanced colorectal adenoma (advCRA) in the clinical diagnosis. Considering that advCRA can be a leading cause of colorectal cancer, it is important to determine between benign colorectal adenomas (BA) and advCRA. With an additional validation cohort, containing 31 advCRA patients (Table S2), our model signified a remarkably higher sensitivity of 67.7% on detecting advCRA, as well as showing the ability to distinguish BA with a specificity of 90.0% (Fig. 4A). Specifically, the box plots (Fig. 4B) clearly illustrated the relatively Low risk scores for the BA compared to those of advCRA, and the difference was proved to be statistically significant through the Wilcoxon Test. This highlights the promising clinical predictive capabilities of our model in detecting advCRA. Traditional biomarker methods struggled to distinguish between benign colorectal adenoma and advCRA, as evidenced by AUCs of 0.6444, 0.5067, and 0.6787 for FIT, CEA, and CA19-9, respectively. Conversely, our model produced a higher level of accuracy in identifying advCRA with an AUC of 0.8462 (Fig. 4C). The results above indicate that our model not only guarantees the ability to make accurate detection of early-stage CRC but also excels in detecting the precancerous lesion of advCRA, showcasing the reliability of the ensemble stacked model in broader clinical settings.

Fig. 4.

Model Performance Tested on an External Validation Cohort of advCRA Samples (A) Boxplots depicting the scores of patients with benign adenoma in original validation and patients with advanced adenoma in external validation predicted by the stacked ensemble model, with a specified cut-off at 0.3385 and the p-value from Wilcoxon Test. (B) Validation ROC curve of model performance in distinguishing benign colorectal adenomas from advanced colorectal adenomas, along with ROC curves based on FIT, CEA, CA19-9 results. (C) Dotted boxplot illustrating the model’s sensitivity in detecting advanced colorectal adenoma and its specificity in detecting benign colorectal adenoma, with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (line expansions from the dots)

Discussion

In this study, we focused on enhancing the early detection of colorectal cancer by establishing a stacked ensemble machine learning model that integrates various cfDNA fragmentomics features. Our goal was to achieve a high level of sensitivity in distinguishing colorectal cancer (CRC) patients from those high-risk individuals with benign colorectal diseases. The stacked ensemble model enabled the increased accuracy, efficiency and robustness of predictions in bioinformatics field, compared to a single model approach [20], and it outperformed all other traditional methods for CRC detection.

As the results shown, our final stacked model demonstrated exceptional performance in CRC detection by achieving high AUC scores at 0.92 in both training and validation cohorts, as well as providing high sensitivity. The stacked ensemble model can predict early-stage CRC at around 90% sensitivity, and with improvement to over 97% sensitivity in the training cohort for later-stage CRC patients. According to results proposed by Chen et al., colonoscopy only yielded a 15.3% participant rate among high-risk populations. Another study from them also depicted that among CRC screening methods, the acceptance rate of colonoscopy (42.5%) was less than half of FIT (94.0%) [21]. Therefore, our study signified a major advancement in the accuracy of CRC early detection, helping produce a more reliable result for clinical diagnosis without a colonoscopy procedure. Another substantial progress of our research is making a noticeable increase in the detection of advanced colorectal adenoma (advCRA), providing a relatively higher sensitivity in detecting advCRA compared to previous studies.

To contextualize our findings, it is important to compare our model with recent prospective trials in screening populations. The ECLIPSE trial, a large multicenter prospective study evaluating Guardant Health’s cfDNA methylation-based assay in an average-risk population, reported CRC sensitivity of 83.1% and advCRA sensitivity of 13.2%, with specificity around 89–90% [11]. Similarly, the K-DETECT trial, which assessed the Shield test (also from Guardant Health), demonstrated sensitivity for CRC at 91% for stages I–III and AUCs >0.9, but performance for adenomas was still limited [22]. The PATHFINDER study, which evaluated the multi-cancer Galleri test in a screening-intended population, showed high specificity (99.5%) but is not optimized for CRC or adenoma detection specifically, and detailed sensitivity data for precancerous lesions remain sparse [23].

This study has several limitations. First, it was based on a retrospective case-control design, which may introduce spectrum bias and lead to an overestimation of model performance compared to a real-world screening setting. Although we used an independent validation cohort from multiple centers to improve generalizability, this does not fully replicate the conditions of a true screening population. Additionally, cases and controls may not reflect the full biological and clinical spectrum encountered in asymptomatic individuals. Despite these limitations, the consistent performance observed across cohorts suggests the model’s potential robustness. Future work will focus on prospective validation in a screening population to confirm clinical utility under real-world conditions. In summary, our cfDNA-based liquid biopsy approach demonstrated strong potential for noninvasive CRC and advCRA detection, offering reliable results for clinical diagnosis. Despite some limitations, our findings affirm the strength of cfDNA fragmentomics in cancer detection.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Model Performance in Matched Training and Validation Sub-cohorts

Additional file 2: Boxplots of Predicted Scores Across Different CRC Stages

Additional file 3: Boxplots of Predicted Scores Based on Location Subgroups

Additional file 4: Boxplots of Predicted Scores Based on Traditional Test Results

Additional file 10: Patient Demography in the Additional Validation Dataset

Additional file 12: Prediction Scores of the Additional Validation Dataset

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients and their families for their dedication to this study, as well as the physicians and researchers involved in this study.

Abbreviations

- advCRA

Advanced colorectal adenoma

- ARM-FSD

Arm-level fragment size distribution

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BA

Benign colorectal adenoma

- CA19-9

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- cfDNA

Cell-free DNA

- CI

Confidence interval

- CNV

Copy number variation

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- DL

Deep Learning

- DRF

Distributed random forest

- FIT

Fecal immunochemical test

- FOBT

Fecal occult blood test

- FP

False positive

- FN

False negative

- GBM

Gradient boosting machine

- GLM

Generalized linear model

- MCMS

Mutation context and mutational signature

- NPV

Negative predictive values

- PPV

Positive predictive values

- QC

Quality control

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- TN

True negative

- TP

True positive

- WGS

Whole-genome sequencing

- XGBoost

Extreme gradient boosting

- XRT

Extremely randomized trees

Author contributions

B.G., Y.L., D.W., and C.D. provided the conceptualization and guidance for the study. J.C., Z.Z., L.Z., and W.L. performed the experiments, analyzed patients’ data, and suggested editions on the manuscript. Q.X. wrote the manuscript. L.X., J.Z., G.Z. F.Z., K.W., Z.L., Q.Y. and L.Y. investigated the study design, collected patients’ samples, and documented clinical information. X.X., R.Y., and D.Z. performed the bioinformatics analysis. R.Y., Q.X. made and revised for figure illustrations. H.B. administrated the project and made significant revision to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82102497, 82272423, 82072380), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC2606200), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022B1515230005), Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2022B1111040002), Guangzhou Key Research and Development Program (2023B03J1248), Research Foundation for Advanced Talents of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (KJ012021097).

Data availability

The scripts and raw feature data for modeling are available on GitHub repository (https://github.com/cancer-oncogenomics/DECIPHER--D--Colon).

Declarations

Ethics approval and patient consent

The study was approved by the ethics committees of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, and the ethical approval number is KY-Q-2022-255-01. All patients provided written consents for participating in this study.

Consent for publication

The content of this manuscript has not been previously published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Competing interests

Q.X., R.Y., X.X., D.Z., L.Y., and H.B. are employees of Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc., Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. The remaining authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Deqing Wu, Email: wudeqing@gdph.org.cn.

Yong Li, Email: liyong@gdph.org.cn.

Chao Ding, Email: dingchao19910521@126.com.

Bing Gu, Email: gubing@gdph.org.cn.

References

- 1.Pardamean CI, Sudigyo D, Budiarto A, et al. Changing colorectal cancer trends in Asians: epidemiology and risk factors. Oncol Rev. 2023. 10.3389/or.2023.10576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y, Han Z, Li X, Huang A, Shi J, Gu J. Epidemiology and risk factors of colorectal cancer in China. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32(6):729–41. 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.06.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1490–502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conteduca V, Sansonno D, Russi S, Dammacco F. Precancerous colorectal lesions (review). Int J Oncol. 2013;43(4):973–84. 10.3892/ijo.2013.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vatandoost N, Ghanbari J, Mojaver M, et al. Early detection of colorectal cancer: from conventional methods to novel biomarkers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(2):341–51. 10.1007/s00432-015-1928-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1467–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lauby-Secretan B, Vilahur N, Bianchini F, Guha N, Straif K. The IARC perspective on colorectal cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1734–40. 10.1056/NEJMsr1714643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekiguchi M, Matsuda T. Limited usefulness of serum carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 levels for gastrointestinal and whole-body cancer screening. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imperiale TF, Porter K, Zella J, et al. Next-generation multitarget stool DNA test for colorectal cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(11):984–93. 10.1056/NEJMoa2310336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut. 2014;63(2):317–25. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung DC, Gray DM, Singh H, et al. A cell-free DNA blood-based test for colorectal cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(11):973–83. 10.1056/NEJMoa2304714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Q, Kang G, Jiang P, et al. Epigenetic analysis of cell-free DNA by fragmentomic profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(44):e2209852119. 10.1073/pnas.2209852119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo YMD, Han DSC, Jiang P, Chiu RWK. Epigenetics, fragmentomics, and topology of cell-free DNA in liquid biopsies. Science. 2021;372(6538):eaaw3616. 10.1126/science.aaw3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan Z, Wang X, Geng X, et al. Liquid biopsy for esophageal cancer: is detection of circulating cell-free DNA as a biomarker feasible? Cancer Commun. 2021;41(1):3–15. 10.1002/cac2.12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cristiano S, Leal A, Phallen J, et al. Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer. Nature. 2019;570(7761):385–9. 10.1038/s41586-019-1272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen L, Ma R, Luo C, et al. Noninvasive early differential diagnosis and progression monitoring of ovarian cancer using the copy number alterations of plasma cell-free DNA. Transl Res. 2023;262:12–24. 10.1016/j.trsl.2023.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan N, Weinberg D, Liu TY, et al. Machine learning enables detection of early-stage colorectal cancer by whole-genome sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):832. 10.1186/s12885-019-6003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su S, Xuan Y, Fan X, et al. Testing the generalizability of cfDNA fragmentomic features across different studies for cancer early detection. Genomics. 2023;115(4):110662. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2023.110662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan JCM, Stephens D, Luo L, et al. Genome-wide mutational signatures in low-coverage whole genome sequencing of cell-free DNA. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4953. 10.1038/s41467-022-32598-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Y, Geddes TA, Yang JYH, Yang P. Ensemble deep learning in bioinformatics. Nat Mach Intell. 2020;2(9):500–8. 10.1038/s42256-020-0217-y. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen HD, Li N, Ren JS, et al. Compliance rate of screening colonoscopy and its associated factors among high-risk populations of colorectal cancer in urban China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;52(3):231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen THH, Lu YT, Le VH, et al. Clinical validation of a ctDNA-based assay for multi-cancer detection: an interim report from a Vietnamese longitudinal prospective cohort study of 2795 participants. Cancer Invest. 2023;41(3):232–48. 10.1080/07357907.2023.2173773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrag D, Beer TM, McDonnell CH, et al. Blood-based tests for multicancer early detection (PATHFINDER): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2023;402(10409):1251–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01700-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Model Performance in Matched Training and Validation Sub-cohorts

Additional file 2: Boxplots of Predicted Scores Across Different CRC Stages

Additional file 3: Boxplots of Predicted Scores Based on Location Subgroups

Additional file 4: Boxplots of Predicted Scores Based on Traditional Test Results

Additional file 10: Patient Demography in the Additional Validation Dataset

Additional file 12: Prediction Scores of the Additional Validation Dataset

Data Availability Statement

The scripts and raw feature data for modeling are available on GitHub repository (https://github.com/cancer-oncogenomics/DECIPHER--D--Colon).